A guide to ethical gift giving (without giving to charity)

A guide to ethical gift giving (without giving to charity)

Opinion + AnalysisRelationships

BY Giacomo Bianchino The Ethics Centre 27 NOV 2017

It’s easy to be frustrated by “charity giving” during the festive season. Little Billy gets a card from World Vision thanking him for support he never knew he gave. All because his sanctimonious aunt decided a new bike wasn’t particularly important.

We’d expect Billy to be pretty upset. But is objecting to “charity giving” childish or is donating on a friend’s behalf incompatible with Christmas giving altogether?

Reminding others of their ethical duties at a time of celebration is, in many ways, noble. There is also value for charity gifts as responses to the hollow commercial practices of modern Christmas traditions.

Charity giving overhauls the tradition of giving. It seeks to fulfil a social need without consideration of the putative “receiver”. As such, the moral case for charity giving isn’t black and white.

While the act might be well-intended, it is poorly executed. When we give at Christmas, presents convey a specific message – one that charity gifts miss altogether.

When we give, we create a sense of shared meaning between individuals. The gift establishes a relationship on the basis of common commitment. In the case of Christmas, the commitment is to one another. Different gifting rituals have other messages.

For instance, during Kwanzaa, members of the African diaspora give homemade gifts to encourage one another to remember their heritage. Kwanzaa emphasises the creation of a moral community in which each member is dedicated to the other. Do-it-yourself gifts foster an attitude where the focus is not on the gift itself, but the recipient.

It might seem as though the charity gift does something similar. By doing good in the name of the recipient, perhaps we foster a relationship based on social justice rather than consumption. But there is a difficulty here.

When our gift is a donation for a distant community, we’re no longer giving a gift to our friend or family member. We’re giving a gift to that distant community.

However deserving the community is, this form of giving is radically different to the form inherent to Christmas or Kwanzaa. We effectively cut the receiver out of the process and instead use the gift ceremony as a means to achieving our own moral agenda.

If charity gifts are a problem, can we give in a way that goes beyond the department store notions of giving and escapes the cycle of consumption?

Yes, but the solution doesn’t lie in what we give, but in how we give.

We can take cues from other cultures. There are entire systems of morality built around the idea of the gift. The famous sociologist Marcel Mauss wrote of gift economies in tribal cultures. He learned how members of traditional Samoan communities gain or lose standing based on their ability to give and to receive well. The exchange of property there is more about establishing relationships than obtaining any particular object or achieving any social goal.

This idea of the giving being more important than the gift isn’t foreign to Christmas traditions. The first recorded act of Christmas gifting was Queen Victoria to her children in 1850. You’d have to rack your brain to find something that the kids of imperial royalty needed. Indeed, the gifts they got were purely symbolic, gestures of goodwill.

So if you’re toying with the idea of ethical giving this Christmas, don’t line up the usual suspects. Make donations to your chosen charities in your own name, but avoid treating them as a replacement for gifting. Charity gifts don’t show others what they mean to you, they substitute the gift for some other moral end.

Give some thought instead to the received wisdom of gift cultures.

Begin by asking yourself, “what does this person mean to me?” “How best can I show them?”

If the gift is a way of sending a certain message, focus on the message. The object is just a means of communication – the message lies in the giving.

Become an artist of the gift – creative, thoughtful and mindful of the recipient – and you can give without being smarmy or sanctimonious.

Truly a modern Christmas miracle.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

5 ethical life hacks

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

There is something very revealing about #ToiletPaperGate

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

I’m really annoyed right now: ‘Beef’ and the uses of anger

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Naturalistic Fallacy

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Measuring culture and radical transparency

Measuring culture and radical transparency

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + Leadership

BY The Ethics Centre 24 NOV 2017

The Ethics Centre is often asked whether it’s possible to “measure” or evaluate organisational culture. Executives and Directors are now alive to the considerable responsibility they bear for the workplaces they preside over – and this has led to a growing demand for robust and credible measurement tools.

Using a methodology developed over 25 years, The Ethics Centre’s Everest process is a forensic review into a company’s ethical culture. It’s based on a simple proposition: that good culture can be measured. Global research shows a healthy culture is essential to sustainable, long-term performance; it enables innovation and builds trust between staff, clients, and customers. Conversely, poor culture leads to bad decisions and an erosion of trust and credibility. The result, inevitably, is disengagement, cynicism, and loss of value.

In the face of challenging conditions, many leaders are tempted to focus their efforts on compliance to prevent ‘bad’ behaviour. But this over-reliance on regulation and surveillance can be counterproductive. Not only can it restrict growth of a positive ethical environment that enables people to innovate and act with a shared purpose and direction, it also doesn’t work. Failures persist. A strong ethical culture is critical to managing risk and building a foundation that will support long term value and performance.

We’ve employed Everest to evaluate the culture of numerous, very different, organisations. We’ve used it on one of Australia’s “big four” banks and a leading superannuation fund. We’ve measured the culture of universities, insurance companies, and leading sports organisations including the Australian Rugby Union, Cricket Australia, and the Australian Olympic Committee.

In carrying out the process both in Australia and abroad, we look at the misalliances between what a company says it stands for, and what occurs in practice. Using this premise, we check how organisations live up to the standards they set for themselves through an audit of systems, policies, procedures, and practices. We undertake extensive qualitative and quantitative research to determine how employees and key stakeholders view the organisation. Out of this process comes a set of powerful insights into the degree of alignment between purpose and practice. We identify the gaps.

Once we’ve made sense of the current state of an organisation, we’re in a position to ask our clients some tough questions about the kind of company they’d like to be. We present clients with a Future State Framework that maps the pathway from the present to the future – asking them to imagine the pinnacle of what’s possible for their organisation. In doing this, we examine five domains:

Culture: The operating system through which people create meaning, purpose, and belonging.

Ecosystem: Organisations are complex, interconnected, and interdependent. They sustain, and are sustained, through relationships, mutual dependencies, and the value they bring to the whole.

Leadership: Providing the guidance, direction, and consistency that allows an organisation to respond to the challenges of uncertainty and change.

Readiness: The ability of an organisation to anticipate and respond to uncertainty. The ability to pre-empt a possible future before it arrives fully formed.

Legacy: The future’s perspective on the present. The map we leave behind for others.

The nature of Everest, particularly when coupled with the independence of The Ethics Centre, is that we can confront leaders with issues that have not previously been articulated, recognised, or challenged. And we do this in a way that lessens defensiveness and focuses on building on the goodwill contained in the existing culture of the organisation.

We’re proud that our process has provided leaders across business and government with the expertise to shine a spotlight on current practices and make choices about the culture and style of organisation they wish to cultivate in the future.

One final note: our Everest reports are delivered to our clients on the understanding that everything contained therein is strictly confidential. What a company does with the report is entirely up to them. None had ever been made public until we worked for the Australian Olympic Committee in 2017.

Facing a media storm over their culture, the AOC took the brave step of releasing the report, in its entirety, to the public. Thanks to this act of radical transparency, we’re able to share it with you here.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Doing good for the right reasons: AMP Capital’s ethical foundations

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

6 Myths about diversity for employers to watch

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships

There are ethical ways to live with the thrill of gambling

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Risky business: lockout laws, sharks, and media bias

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Big Thinker: Mary Wollstonecraft

Big Thinker: Mary Wollstonecraft

Big thinkerPolitics + Human RightsRelationships

BY Kym Middleton The Ethics Centre 22 NOV 2017

Mary Wollstonecraft (1759—1797) is best known as one of the first female public advocates for women’s rights. Sometimes known as a “proto-feminist”, her significant contributions to feminist thought were written a century before the word “feminism” was coined.

Wollstonecraft was ahead of her time, both intellectually and in the way she lived. Pursuing a writing career was unconventional for women in 18th century England and she was denounced for nearly a century after her death for having a child out of wedlock. But later, during the rise of the women’s movement, her work was rediscovered.

Wollstonecraft wrote many different kinds of texts – including philosophy, a children’s book, a fictional novel, socio-political pamphlets, travel writings, and a history of the French Revolution. Her most famous work is her essay, A Vindication of the Rights of Woman.

Pioneering modern feminism

Wollstonecraft passionately articulated the basic premise of feminism in A Vindication of the Rights of Woman – that women should have equal rights to men. Though the essay was published during the French Revolution in 1792, its core argument that women are unjustifiably rendered subordinate to men remains.

Rather than domestic violence, women in senior roles and the gender pay gap, Wollstonecraft took aim at marriage, beauty, and women’s lack of education.

The good wife: docile and pretty

At the core of Wollstonecraft’s critique was the socioeconomic necessity for marriage – “the only way women can rise in the world”. In short, she argued marriage infantilised women and made them miserable.

Wollstonecraft described women as sacrificing respect and character for far less enduring traits that would make them an attractive spouse – such as beauty, docility, and the 18th century notion of sensibility. She argued, “the minds of women are enfeebled by false refinement” and they were “so much degraded by mistaken notions of female excellence”.

Mother of feminism and victim blamer?

Some readers of A Vindication for the Rights of Woman argued Wollstonecraft was only a small step away from victim blaming. She penned plenty of lines positioning women as wilful and active contributors to their own subjugation.

In Wollstonecraft’s eye, expressions of feminine gender were “frivolous pursuits” chosen over admirable qualities that could lift the social standing of her sex and earn women respect, dignity and quality relationships:

“…the civilised women of the present century, with few exceptions, are only anxious to inspire love, when they ought to cherish a nobler ambition, and by their abilities and virtues exact respect.”

While some might find Wollstonecraft was too harsh on the women she wanted to lift, her spear was very much aimed at men, “who considering females rather as women than human creatures, have been more anxious to make them alluring mistresses than rational wives”.

Grab it by the patriarchy

Like the word feminism, the word patriarchy was not available to Wollstonecraft. She nevertheless argued men were invested in maintaining a society where they held power and excluded women.

Wollstonecraft commented on men’s “physical superiority” although she did not accept social superiority should follow.

“…not content with this natural pre-eminence, men endeavour to sink us still lower, merely to render us alluring objects for a moment.”

Wollstonecraft’s hammering critique against a male dominated society suggested women were forced to be complicit. They had few work options, no property or inheritance rights, and no access to formal education. Without marriage, women were destined to poverty.

What do we want? Education!

Wollstonecraft pointed out all people regardless of sex are born with reason and are capable of learning.

In a time where it was considered racial to insist women were rational beings, Wollstonecraft raised the common societal belief that women lacked the same level of intelligence as men. Women only appeared less intelligent, Wollstonecraft argued, because they were “kept in ignorance”, housebound and denied the formal education afforded to men.

Instead of receiving a useful education, women spent years refining an appealing sexual nature. Wollstonecraft felt “strength of body and mind are sacrificed to libertine notions of beauty”. Women’s time was poorly invested.

How could women, who were responsible for raising children and maintaining the home, be good mothers, good household managers or good companions to their husbands, if they were denied education? Women’s education, Wollstonecraft contended, would benefit all of society.

Wollstonecraft suggested a free national schooling system where girls and boys were taught together. Mixed sex education, she argued, “would render mankind more virtuous, and happier” – because society and the term mankind itself would no longer exclude girls and women.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

How to break up with a friend

Explainer

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Dignity

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights

Survivors are talking, but what’s changing?

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

If women won the battle of the sexes, who wins the war?

BY Kym Middleton

Former Head of Editorial & Events at TEC, Kym Middleton is a freelance writer, artistic producer, and multi award winning journalist with a background in long form TV, breaking news and digital documentary. Twitter @kymmidd

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Ethics Explainer: Tolerance

For some people, the value of tolerance is simply the opposite of intolerance. But to think of tolerance in simple binary terms limits our understanding of important aspects of the concept.

We gain greater insight if we consider tolerance as the midpoint on a spectrum ranging between prohibition at one end to acceptance at the other:

Prohibition ————— Tolerance ————— Acceptance

The Ancient Greek philosopher Aristotle called this middle point of the spectrum, the golden mean. Approaching tolerance this way, makes it what philosophers call a virtue – the characteristic between two vices.

For example, Aristotle places the virtue of courage at the midpoint (or golden mean) between cowardice and recklessness. So, a courageous person has a proper appreciation of the danger to be faced but stands steadfast and resolute all the same.

Cowardice ————— Courage ————— Recklessness

Although Aristotle’s doctrine of the golden mean can help us understand tolerance, quite a bit more needs to be said. Some things deserve to be rejected and prohibited. And some things ought to be accepted.

We should neither accept or tolerate behaviour that denies the intrinsic dignity of people – for example, the defiling of synagogues by anti-Semites. Instead, we should have a general acceptance and respect for everyone’s intrinsic dignity. People should neither be rejected nor merely tolerated.

Unacceptance ≠ Prohibition

However, there are some things you might reasonably not accept, yet not want to prohibit. This is typically the case when you encounter an idea, custom or practice that is either unfamiliar or at odds with your own convictions about what makes for a good life.

For example, a vegetarian might be convinced it is wrong to eat animals. Such a person may never accept the practice as part of their own life. However, they may not want to stop others eating meat. Instead, they will tolerate other people’s consumption of animals.

This reveals an essential aspect of tolerance. Toleration is always a response to something that is disapproved of – but not to such a degree as to justify prohibition. Tolerance is, by definition, a mark of disapproval.

And so some people seek from society something more than ‘mere tolerance’. Instead, they look for acceptance.

Tolerance to acceptance

The word ‘acceptance’ rang out loud when it was revealed a majority of Australian voters answered yes to the same sex marriage postal survey in 2017. For gay and lesbian couples, the result is evidence of wide acceptance of their equality as citizens.

Individuals and communities are not only entitled to think about what should be accepted, tolerated or prohibited. We can also be obliged to consider these things.

Without wanting to confuse ethical with legal obligations, this is the difficult task of parliaments. To continue with the same sex marriage example in Australia, they were obliged to consider what behaviours should be accepted, tolerated, or prohibited in terms of wedding services and religious freedoms.

The ethics of tolerance

Ethics calls upon people to examine their lives – including the quality of their reasons when forming judgements. An ethical life is one that goes beyond unthinking custom and practice. This is why judgements about what is to be accepted, tolerated or prohibited need to be made free from the distorting effects of prejudice. Beliefs, customs and institutions should be evaluated for what they actually are – and not on the basis of assumptions about people or the world. The quality of our judgment matters.

There can be sincere disagreement among people of good will. Respect for persons – and the general acceptance this requires – can sit alongside ‘mere’ tolerance of each other’s foibles.

And that may be the best we should hope for.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships, Society + Culture

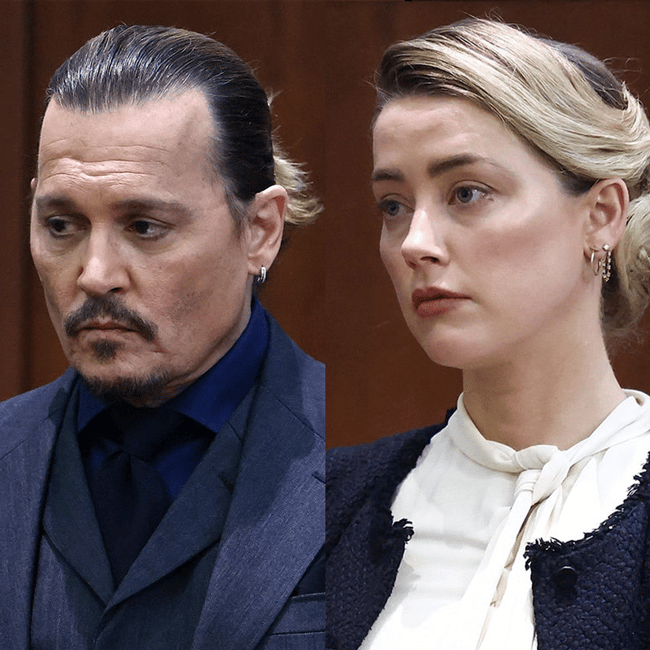

You won’t be able to tell whether Depp or Heard are lying by watching their faces

Explainer

Health + Wellbeing

Ethics Explainer: Hedonism

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

Yellowjackets and the way we hunger

Explainer

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Ethics Explainer: The Harm Principle

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Ethics Explainer: Conscience

Conscience describes two things – what a person believes is right and how a person decides what is right. More than just ‘gut instinct’, our conscience is a ‘moral muscle’.

By informing us of our values and principles, it becomes the standard we use to judge whether or not our actions are ethical.

We can call these two roles ethical awareness and ethical decision making.

Ethical Awareness

This is our ability to recognise ethical values and principles.

The medieval philosopher Thomas Aquinas believed our conscience emerged from synderesis: the ‘spark of conscience’. He literally meant the human mind’s ability to understand the world in moral terms. Conscience was the process by which a person brought the principles of synderesis into a practical situation through our decisions.

Ethical Decision Making

This is our ability to make practical decisions informed by ethical values and principles.

In his writings, Aristotle described phronesis: the goodness of practical reason. This was the ability to evaluate a situation clearly so we would know how to act virtuously under the circumstances.

A conscience which is both well formed (shaped by education and experience) and well informed (aware of facts, evidence and so on) enables us to know ourselves and our world and act accordingly.

Seeing conscience in this way is important because it teaches us ethics is not innate. By continuously working to understand our surroundings, we strengthen our moral muscle.

Conscientious Objection

In politics, much of the debate around conscience concerns the “right to conscientious objection”.

- Should pro-life doctors be required to perform abortions or refer patients to doctors who will?

- Must priests break the confessional seal and report sex offenders who confess to them?

- Can pacifists be excused from conscription because of their opposition to war?

For a long time, Western nations, informed by the Catholic intellectual tradition, believed in the “primacy of conscience” – the idea that a person should never be forced to do something they believe is against their most deeply held values and principles.

In recent times, particularly in medicine, this has come to be questioned. Australian bioethicist Julian Savulescu believes doctors working in the public system should be banned from objecting to procedures because it compromises patient care.

This debate sees a clash between two worldviews – one where people’s foremost responsibility is to their own personal beliefs about what is good and right and another where this duty is balanced against the needs of the common good.

Philosopher Michael Walzer believes there are situations where you have a duty to “get your hands dirty” – even if the price is your own sense of goodness. In response, Aristotle might have said, “no person wishes to possess the world if they must first become someone else”. That is, we can’t change who we are or what we believe in for any price.

Recommended viewing

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

The self and the other: Squid Game’s ultimate choice

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Consequentialism

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships, Science + Technology

Philosophically thinking through COVID-19

Opinion + Analysis

Climate + Environment, Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

A burning question about the bushfires

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Ethics Explainer: Progressivism

Progressivism is a political ideology based on the possibility of moral progress. In practice, this looks like an optimism about the future of humanity.

Progressives believe the course of human history is moving us closer to a state of peace, equality, and prosperity. They also tend to believe in human perfectibility. Politics, technology, and education can overcome human failings to create a utopia.

We can see this in the work of philosophers Steven Pinker and Michael Shermer. Pinker says since the Enlightenment, altruism has been on the rise and violence is declining around the world. Shermer suggests each generation has been smarter than the last, which he believes, has continually reduced impulsive violence.

Hegel’s synthesis

German philosopher Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel believed moral progress was inescapable. He thought the forces of history shape humanity for the better, pushing it toward perfection.

Hegel believed history unrolled according to a “dialectical” pattern. This was where opposing sides clashed and compromised with one another. These opposing forces, which he called the “thesis” and “antithesis”, would clash before reaching a “synthesis”.

This synthesis would then spark a new antithesis and the process would continue. Hegel thought each stage in the thesis-antithesis-synthesis series moved us closer to a state of perfection. His work is said to have inspired other progressive thinkers, most notably communist philosopher Karl Marx.

The darker side of progress

Today, new forms of genetic editing promise a cure to a range of illnesses and maybe even death itself. Transhumanists believe we can overcome the limitations of our humanity and mortality. They suggest a range of options, from changing our biology to uploading our consciousness into a supercomputer.

But practical efforts to create this perfect world have not always been pleasant. At times it has been outright barbaric.

One example is the eugenics movement. It aimed to breed some people, like those with disabilities, out of society altogether, and cited social progress as their defence.

This is one reason why conservatives often urge caution around progress. They encourage us to be mindful of the potential unintended side effects of new policies or technology.

But progressives are often concerned this will inhibit life changing new developments. They suggest we deal with issues as they arise, rather than trying to predict them in advance.

Heaven on earth

Progressives often see education as the silver bullet solution for social problems. Like Ancient Greek philosopher Socrates, they tend to believe all vice is the result of ignorance, not malice. They suggest humans are fundamentally good and education will bring out the better angels of our nature.

But some are sceptical whether education alone will fix all humanity’s woes. They agree humans are mostly good but don’t blame ignorance for evil. Instead, they see war, conflict and violence as the product of oppression and inequality.

Karl Marx believed conflict between the wealthy and the working class was a central theme in human society. He believed the power imbalance between rich and poor was bad for everyone. He famously claimed people would be better throwing away hierarchies based on class and wealth. Only when we’re all equal, he thought, will we be able to perfect ourselves.

English philosopher Mary Wollstonecraft suggested the path to human perfection might require both politics and education. She argued that political change requires us to educate marginalised groups. Otherwise, any change will continue to exclude the groups already on the fringes of society.

This explains why more women and culturally diverse people have contributed to progressive thinking in recent decades. In the past, the leading progressive thinkers tended to be white men. Improved access to education has enabled a greater range of voices to contribute to the larger conversation of what a perfect world might look like and how we could create it.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Pop Culture and the Limits of Social Engineering

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Breaking news: Why it’s OK to tune out of the news

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

What ethics should athletes live by?

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

We can help older Australians by asking them for help

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

A win for The Ethics Centre

A win for The Ethics Centre

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + LeadershipSociety + Culture

BY The Ethics Centre 17 NOV 2017

The Ethics Centre was announced the 2017 winner of the Optus MyBusiness Awards Training Education Provider of the Year, for our innovative business ethics education program.

The prestigious annual event is Australia’s longest running awards program for SMEs. 150 finalists attended the award ceremony at Sydney’s Westin Hotel where the winners were announced across 28 award categories.

The Ethical Professional Program is our core professional education program, centred on applied ethics, quality decision making, professional practice and leadership. Exclusively devised for financial advisors, brokers, bankers and those who work alongside them, it has been rolled out across the financial service sector.

Participants who have completed the program tell us it helped them build stronger relationships with colleagues and clients, link everyday decisions back to their organisation’s strategy and purpose, and deal with complex issues as they arise.

The program consistently achieves high net promoter scores and positive feedback that indicates participants not only leave with new skills but enjoy the process too – not something you hear every day about ethics education!

We take our role as a leading provider of ethics education very seriously. As events in the world continue to shock, scare and surprise us, and our trust in core institutions appears to plummet, it can seem as if people care less and less about ethics. Our experience tells us otherwise. The people and organisations we work with across our ethics, leadership and learning programs are hungry to explore what they value, the principles they hold on to, and how to make their way through some of the most difficult ethical challenges we face today.

Our organisation has been involved in learning and education for over 25 years and are thrilled to be recognised for the transformative programs we deliver in ethics education.

As an independent non-profit specialising in ethics, we’ve been asked by many organisations, industries and governments, both locally and internationally, to provide a different kind of education and training experience.

Each of our education and training programs challenge participants to think differently – to critically examine other opinions, be consistent in their judgements, and make responsible and considered decisions. They provide the skills and tools to understand and resolve the multitude of difficult ethical challenges we all face as part of our personal and professional lives.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Ask the ethicist: Is it ok to tell a lie if the recipient is complicit?

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Shadow values: What really lies beneath?

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture

10 films to make you highbrow this summer

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture, Business + Leadership, Health + Wellbeing

Make an impact, or earn money? The ethics of the graduate job

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

A radical act of transparency

A radical act of transparency

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + Leadership

BY The Ethics Centre 13 NOV 2017

The Australian Olympic Committee had been through a six month media firestorm by the time its new CEO, Matt Carroll, got his hands on a confronting review of the organisation’s culture.

The AOC had been battered by a succession of negative events. Its former CEO, Fiona de Jong, had resigned in a blaze of headlines while their longstanding president John Coates had fought off a bruising challenge to his leadership in a publicised election campaign.

Some of its most senior executives received allegations of bullying and poor behaviour. Part of its 36 staff complained the AOC was the most dysfunctional place they’d ever worked. There was even an ugly rift between the AOC and the Australian Sports Commission, which funds high performance sports.

What’s more, the medal tally from athletes in the most recent summer Olympic Games in Rio had been disappointing – our worst in 15 years.

Even with Carroll in place as the new “cleanskin” CEO, the damaging headlines were showing no sign of abating. With the results of the 64-page cultural review in his hands, Carroll knew the bad news would keep leaking out.

So he and Coates decided to publish the review’s findings and its 17 recommendations on its website and release them to the media – effectively putting the organisation’s “dirty laundry” on the table for all to see.

“Why? We knew we were going to get criticised, and we did. We knew we were going to get held up and ridiculed, and we did”, says Carroll today.

“We copped a bit of a battering in the media for a week, but I know that the national sporting federations had a great deal of respect for us doing it.”

“But there was one question I couldn’t have answered if we hadn’t done it and it was: ‘What are you hiding?’ And that would have dragged us backwards.”

They concluded the only way to move on and put their troubles behind them was to engage in an act of radical transparency.

A ‘brave’ decision

The independent review, conducted over two months by The Ethics Centre, was not initially intended to be a public document. But when the report finally landed in the AOC boardroom – a frank appraisal of all that was wrong with the organisation, and what they needed to do to fix it – the decision was quickly made to go public.

“The transparency involved in publishing the report is very good for my purposes in changing the organisation because it is out there”, Carroll says.

“There can be no pushback … It sets a standard that this is the way we are going to operate.”

The business community was agog; a corporate leader made a wary comment telling Carroll the move was “brave”.

But while staff and the sporting federations were generally appreciative of the review and the courageous decision to go public with the findings, it was not a painless process.

“It did have an effect on some of the senior managers because there was this inherent criticism of the leadership team – some of whom are new – but they have shouldered that”, says Carroll.

“For the leadership team, there was this feeling they had all been tarred with the same brush and some of them took that quite hard. We have all been tarred a bit, but we have recognised the issues, recognised the problems, we have agreed that we need to make change.”

Coates, however, was accused of sidestepping responsibility for the poor organisational culture when he told a news conference, “The only criticism of me, personally, has been my acrimonious relationship with some stakeholders, particularly [Australian Sports Commission chair] John Wylie, and that has been put in context.”

Extending transparency

One of the findings of the AOC culture review was a lack of transparency around key decisions – like how individual sports are funded, how staff members are selected to work on site at each Olympic Games. This lack of transparency had led to an atmosphere of suspicion and allegations of favouritism.

Carroll intends to usher in a new era of transparency to dispel any suggestion of favouritism.

“Equally, performance is expected. Yes, we can structure everything and will make sure everyone knows their roles and responsibilities. There is a process, and it is transparent, but that doesn’t mean everybody is a winner.

“We are in the business of high performance sport and our athletes expect the same [level of performance] from our organisation. If you don’t perform in your role, yes, you probably won’t get to go to the Games – but you will know why.

“I am always of the view that you tell the truth, otherwise it comes around to bite you anyway.”

Carroll says this level of openness does not mean that everyone gets a say. “Transparent decision making doesn’t mean you are standing out there asking everyone’s opinion.

“But there is a process where everyone knows how it works and they know what the expectations are and, therefore, they can measure themselves.”

A culture of stress

“One reason that it was always so frantic was that people made it frantic.”

Having come into his role with a 20 year career in sports management, Carroll says he did not think there were any serious ethical problems at the AOC. He saw it was more of a matter of applying appropriate ethical standards to behaviours – especially at times when the organisation is operating under “emergency mode”, such as Games times.

“I am sympathetic to the stress the organisation is sometimes under. I don’t think there was a massive problem, as big as the media was dressing it up, at all. It was more about settling the organisation down and having those restructured roles and responsibilities”, he says.

“There was a culture of stress. One reason that it was always so frantic was that people made it frantic, rather than taking a deep breath. We are not changing the world, we don’t save lives every day of the week, we leave that to more important organisations. You have got to get people to take a step back and take a deep breath.”

Sometimes, the solution is to be nicer to each other, Carroll says. “You can have a disagreement with people … but, for Heaven’s sake don’t behave like [you are in] a schoolyard. Have respect for people.

“If you have no respect for people then they won’t have respect for you.”

Carroll says sport’s important role in Australian culture is reflected in the community’s high expectations of behaviour.

“That is why sport needs to retain its absolute credibility. If it loses that credibility, those role models – no matter how hard they try – won’t be able to show that influence and leadership.

“We can change lives, we don’t save lives. Sport has got to have its own perspective: it isn’t the be all and end all of the country. There are other far more important aspects of society in Australia than sport.

“We can play that leadership role, we can play that role of setting some standards, but we also must accept, at the end of the day, it is about sport.”

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Science + Technology

Big tech knows too much about us. Here’s why Australia is in the perfect position to change that

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Pulling the plug: an ethical decision for businesses as well as hospitals

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

‘Woke’ companies: Do they really mean what they say?

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Sylvie Barbier and Rufus Pollock on failure and fostering a wiser culture

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

In the court of public opinion, consistency matters most

In the court of public opinion, consistency matters most

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + Leadership

BY The Ethics Alliance The Ethics Centre 13 NOV 2017

If you’re like us, you spend a lot of time reading the business news. And you’re be familiar with a strange paradox: while some highly respected business leaders can be brought to their knees by one poor decision or ethical stumble, there are others that seem to get away with it time after time. In the language of the CBD, they’re Teflon-coated.

It hardly seems fair that those who have spent their career doing the right thing attract more criticism when they fail. But it seems there is nothing the public hates more than a hypocrite.

Psychologist Dr. Melissa Wheeler says hypocrisy is often considered a bigger sin than the transgression itself.

“The thing that really gets people’s attention is someone’s moral hypocrisy – when you say something, but do something very differently. Or you condemn something, but then have been found to be doing it as well”, says Wheeler, who has a PhD in moral and social psychology and is a Research Fellow in the Department of Management and Marketing at the University of Melbourne.

Cyclist Lance Armstrong is therefore judged more harshly because he was a healthy-life champion who was doping himself throughout a career, which included winning seven Tour de France events.

“The thing that really gets people’s attention is someone’s moral hypocrisy – when you say something, but do something very differently.”

Conversely, we shrug off US President Donald Trump’s Twitter diatribes and troublesome behaviour because they’re generally consistent with his career and private life over the decades.

“With Trump, I keep wondering why people aren’t more outraged and shocked at all the things that are coming out, scandal after scandal, and why are people not even batting an eye anymore”, says Wheeler.

“And I think it is because we have come to expect that from him, because it conforms with what you are expecting and it conforms with your stereotype of what he, as a politician, is.”

Surprise makes a scandal ‘stick’

Mud seems to “stick” if someone does the unexpected or flouts their own stereotype, she says.

In the corporate world, Volkswagen’s falsification of its vehicle emissions data became one of the biggest scandals of 2015. It was trading on its “green” credentials, but was lying about its performance.

Organisations cannot even expect that their good record will help insulate them from future mistakes.

“If you do anything to fall from that grace, it is going to be worse”, says Wheeler.

In fact, not only can “good-practise champions” attract more criticism when they fail, they can also draw more scrutiny in the first place, according to the managing director of the Australian Centre for Corporate Social Responsibility, Dr Leeora Black.

“Paradoxically, sometimes companies with stated good intentions are targeted [by activists] more frequently than companies without, simply because they are more likely to respond.”

Black, an advisor with a PhD in Corporate Social Responsibility, says change campaigners will target companies that already have expressed a commitment to be socially responsible. “They know they will get more traction from those companies than companies that don’t care.”

“Paradoxically, sometimes companies with stated good intentions are targeted more frequently than companies without, simply because they are more likely to respond.”

Activists target companies they can change

Public opinion and media coverage often follow the activists, which goes some way towards explaining why socially responsible companies get more flak for their ethical breaches, she says.

“Normally, without that targeting by activists, if a company is doing well and it stumbles, stakeholders are more likely to give it the benefit of the doubt.”

“Many people have spoken to me about this [phenomenon] in their companies, particularly in the early days, when they get started. Normally, companies that are further advanced in their corporate responsibility journey become more resilient and they also develop stronger relationships with stakeholders and so they are much less likely to suffer that kind of backlash when they do slip”, says Black.

“It is the companies that are newer to CSR that are more likely to get targeted and may be more concerned about it.”

However, fears of harsh judgement should not be a disincentive to hold and display high ethical standards. The business case of corporate social responsibility (CSR) is that the “benefits outweigh the troubles”, she says.

“And the troubles are short term and the benefits are long term.”

Black says the benefits of CSR are better employee attraction and retention, higher employee productivity and organisational commitment.

“For companies listed on the stock exchange, over time, their better performance will be rewarded by shareholders. There is also the opportunity for enhanced risk identification and management, enhanced innovation and improved reputation”, she says.

“But it does take consistency and persistency. You don’t just do one good thing and expect everybody to fall all over the place, gobsmacked about how wonderful your company is. That doesn’t cut it. That is the kind of thing that is more likely to be viewed as hypocrisy.

“Where there are systemic, fundamental, deep-seated commitments being made by the company that are being expressed in its culture and its strategy, then, over time, the persistence and the consistency will be rewarded and the company will become much more resilient to shocks that may happen from an occasional stumble.”

Scandal recovery depends on response

Wheeler says once a scandal has broken, an organisation’s ability to recover will depend on how it handles the aftermath and whether it uses it as an opportunity to grow.

Effective responses include taking responsibility, working around the facts of the transgression, not sweeping it under the rug and providing appropriate explanations for the wrongdoing.

“I think there is a real sincerity in that. So, it is not just like trying to weasel out of the blame.

“And then people like to see that the companies are willing to accept and serve what might be considered an equitable punishment. They want to see there is some punishment for the action and some consistent internal changes – what sort of rehabilitation are they doing?”

University of Pittsburgh researchers studied 100,000 social media tweets to see how the tenor of the public discussion changed in the weeks following Volkswagen’s emissions data scandal.

A sentiment analysis over four separate weeks showed how criticism of the company abated once Volkswagen and the regulators took action.

“Ultimately, if the company’s efforts at recovery are successful, the sentiment returns to a neutral state”

Sentiment about the brand was extremely negative immediately after the news broke, but shifted once the company started recovery efforts (such as an apology and recall) and regulatory agencies placed responsibility with the company.

“Ultimately, if the company’s efforts at recovery are successful, the sentiment returns to a neutral state”, says the study’s lead author, Vanitha Swaminathan, Thomas Marshall Professor of Marketing at the Katz Graduate School of Business at the University of Pittsburgh.

Learning from the experience

The damage to Volkswagen included a plunge in their stock price, government investigations in North America, Europe and Asia, the CEO’s resignation, the suspension of other executives, the company’s 2015 record loss, and a tab estimated at more than $US19 billion to rectify the issues, according to American economist, Boris Groysberg, in the Harvard Business Review.

There are also expected to be long term impacts on the careers of Volkswagen employees. “Our research shows that executives with scandal-tainted companies on their résumés pay a penalty on the job market, even if they clearly had nothing to do with the trouble”, says Groysberg.

“Overall, these executives are paid nearly 4 per cent less than their peers. Given that initial compensation in a job strongly affects future compensation, the difference can become truly significant over a career.

Good news for those who have slipped up is that surviving a scandal can result in a stronger operating performance in the long term – if the organisation has learned from the experience, ejected the wrongdoers and put into place measures to avoid a recurrence.

Researchers at the University of Sussex studied 80 corporate scandals and discovered that although share prices plummeted by between 6.5 and 9.5 per cent in the month after the bad headlines started, the experience could lead to improved performance in the long term. The scandals included breach of contract, bribery, conflicts of interest, fraud, price fixing and other white-collar crimes, as well as personal scandals such as a CEO having an affair, lies on CVs and harassment cases.

Dr Surendranath Jory, who led the study, said safeguards put into place to protect against further abuses seemed to allay investor fears and avoid further drops in a company’s stock price, ensuring they rebound to the levels of their rivals. “Three years on from scandals, the share price performance of firms matched those that had not been affected by scandals.

“Clearly, investors value ethics and they place a premium on it.”

Follow The Ethics Centre on Twitter, Facebook, Instagram and LinkedIn.

This article was originally written for The Ethics Alliance. Find out more about this corporate membership program. Already a member? Log in to the membership portal for more content and tools here.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Survivor bias: Is hardship the only way to show dedication?

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships

Workplace romances, dead or just hidden from view?

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

The anti-diversity brigade is ruled by fear

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships

It’s time to take citizenship seriously again

BY The Ethics Alliance

The Ethics Alliance is a community of organisations sharing insights and learning together, to find a better way of doing business. The Alliance is an initiative of The Ethics Centre.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Big Thinker: Socrates

Socrates (470 BCE—399 BCE) is widely considered to be one of the founders of Western philosophy.

Stonemason, soldier, citizen, philosophy’s first ‘martyr’, Socrates helped shape one of the major intellectual foundations on which Western civilisation has been built. Yet, no work of philosophy bears his name as the author. All we know of him is derived from the work of others – especially Plato, Xenophon and Aristophanes.

The rise of ethics

Prior to Socrates, ancient philosophy tended to focus on questions that today might be considered the domain of physics. ‘Pre-Socratic’ philosophers tended to focus on fundamental questions about the nature of the universe – like the building blocks of matter or the nature of time and motion.

When Socrates came along, he proposed a completely different set of questions for philosophical deliberation. He drew attention away from questions about how the world is and towards questions about how we are to be in the world. While he made valuable contributions to the evolution of thought about epistemology and politics, it is this turn toward ethics that introduced a fresh practical dimension to philosophy.

Earlier philosophical debates of Thales, Anaximander and Democritus, for example, were all theoretical. Human knowledge and understanding might have advanced, but nothing in the world was directly changed by their deliberations.

Socrates’ focus on ethics was intended to generate practical outcomes. He expected philosophical work might lead to a change in both attitudes and (importantly) actions of people. In turn, this was intended to produce effects in the world. Although we have only come to see Socrates through the eyes of others, his friends (like Plato and Xenophon) and foes (like Aristophanes) agree he wished to have an impact on the people around him and the kind of society they were creating as a result of their choices.

What friends and foes disagreed on was Socrates’ motivation. His critics lumped him in with the Sophists who were looked down on as philosophical guns for hire.

A new focus on ethics repositioned philosophy as something relevant to everyday life. Socrates’ core question, ‘What ought one to do?’ does not apply in a limited set of circumstances. It is a question of general application to any situation where a choice is to be exercised – and is applicable to every person, whatever their station in life.

In some sense, this is what made Socrates such a troublesome – or dangerous – person. In one fell swoop, he brought philosophy into the agora (the marketplace), making it relevant and accessible to people of all ages and degrees.

This upset hierarchies and orthodoxies. As we know, a gadfly is rarely welcome. Socrates was eventually executed for crimes of ‘impiety’ and ‘corrupting the youth’ – in short, for teaching and encouraging them to question established norms and think for themselves.

The virtue of ‘constructive ignorance’

On being asked who the wisest person in Athens was, the Oracle of Delphi nominated Socrates. Socrates was astounded – he believed himself to know nothing. To prove his relative ignorance, Socrates sought to find wiser folk amongst the citizens of Athens, questioning them at length about the nature of things like justice and love.

His questioning had practical implications. At that time in democratic Athens, citizens were actively involved in enacting laws or judgements in the courts.

In the end, Socrates came to believe the Oracle of Delphi was correct – but only because his superior wisdom lay in his realising the limits of his knowledge.

Along the way to this realisation, Socrates developed the process of elenchus (the ‘Socratic method’). It is a distinctive form of questioning designed to open space for insight and self-knowledge. The idea we have much to learn about ourselves and the world might suggest we are ignorant. Such a view could position the Socratic method of questioning as a mean spirited exercise. Those subjected to it did not necessarily enjoy the experience or see it in a positive light. This no doubt contributed to the belief Socrates was an impious trouble maker.

The importance of the examined life

Although Socrates contributed many insights that are still drawn upon today (but not necessarily accepted), one of his most famous and profound is his claim that ‘the unexamined life is not worth living’.

This claim goes beyond being a recommendation we should think before we act – which may be a prudent thing to do. Socrates is attempting to draw our attention to a deeper truth about the human condition. He encourages us to participate in a form of being that has the capacity to transcend the requirements of instinct and desire in order to make conscious – that is, ethical – choices. Socrates claimed if we fail to do this, we live a lesser life.

One of the effects of examination is, according to Socrates, the development of phronesis (practical wisdom) which is the foundation for virtue. For Socrates (and later for Aristotle – in a slightly different form), the possession of virtue is not just a matter of interior orientation. It is essential to being able to see the world as it is and be able to make good decisions.

Like Aristotle, Socrates sees vice as the source of defective vision. Socrates thought people make bad choices and do bad things out of ignorance. He thought if people could only ‘see’ what is good, they would choose it.

This all finally comes together in the way Socrates challenged the status quo. To live an examined life is to reject things ought to be done just because they have always been done.

Instead, Socrates is an early exponent of an inner voice that (in Socrates’ case) is supposed to have warned him against making an error. Socrates called this voice his ‘daimōnic sign’ – something Aquinas would call ‘conscience’ over a thousand years later.

It may be difficult to distinguish the real Socrates from the versions of the man created by others – which were either celebratory or lampooning. But this we know. When given the chance to escape and avoid the sentence of death imposed on him by the Athenians, Socrates chose to stay. In defence of his ideas and in conformance with his ideals Socrates drank the hemlock and died.

He can hardly have imagined the impact he would have on the world.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

LISTEN

Health + Wellbeing, Society + Culture

Life and Debt

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Want to live more ethically? Try these life hacks

Big thinker

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Big Thinker: Mary Wollstonecraft

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships