The morals, aesthetics and ethics of art

The morals, aesthetics and ethics of art

Opinion + AnalysisSociety + Culture

BY Dr Laura D’Olimpio The Ethics Centre 25 FEB 2016

People love a good story. As Aristotle said, we are story-telling animals. By engaging with stories we can consider different points of view and empathise with others – including fictional characters.

Stories let us reflect on how we would feel or act if we were in the shoes of another. They might even help us be more compassionate in real life.

Truth and Story-telling

True stories are among the narratives that grab our attention. Reality TV has become a phenomenon, while dramatic portrayals of the lives of famous people, and retelling real life events are increasingly popular. Perhaps the it’s driven by our desire to better understand human nature.

But how real are these representations? The idea of reality TV as scripted surely doesn’t surprise many viewers, but what about biopics like The Wolf of Wall Street, Spotlight or The Big Short?

Overt ethical messages in such movies are made all the more powerful if the audience sees these films as factual.

Any film based on reality will have a tough job conveying a person’s life or a series of events that unfolded over a number of years into a 120-minute linear narrative. There are important decisions to be made such as what to include or exclude, and from which perspective to tell the tale. Then there is the element of ‘moralising’ – sending a ‘take home message’ to the audience.

Overt ethical messages in such movies are made all the more powerful if the audience sees these films as factual. So does that mean filmmakers are obliged to be truthful in biopics, or are they only bound by what makes a good story?

Aestheticism – art for art’s sake

There is a strong historical precedent for separating the moral from the aesthetic value of artworks. Oscar Wilde’s famous quote from the preface to The Picture of Dorian Gray states, “There is no such thing as a moral or an immoral book. Books are well written, or badly written. That is all.”

This sums up a philosophical position known as ‘Aestheticism’, which argues that the only relevant factor when judging the quality of an artwork is its aesthetic value. Wilde explicitly categorises himself as an ‘Aestheticist’, yet he is well-known as a moralist. What’s going on here?

The reason people watch films or read is primarily for enjoyment – to tap into this so-called aesthetic experience. This involves enjoying the beauty or creativity of an artwork for its own sake. Aesthetic value is unique to artworks, so Aestheticists claim this should be the sole basis for aesthetic judgement. Any moral message in the work should not, therefore, affect the overall value of the artwork, either positively or negatively.

Aestheticists like Wilde may also want to protect art from censorship. If an artwork is judged only on the basis of its aesthetic qualities, it should not be condemned for its moral message. This concern harks all the way back to Ancient Greece when Plato was worrying in The Republic that the poets might corrupt the youth.

Moralism – the message behind the masterpiece

Artists are often well placed to critically engage with moral themes. Wilde’s novels and plays satirised the social norms of his day, and the best way he could protect his artistic right to free speech was to claim that the only thing one should judge is an artwork’s aesthetic merit.

However, to take this further and say artists are not concerned with moral, economic or political concerns is, I believe, mistaken. Of course artists need to consider real world concerns. Partly because they need to make a living and survive in the world in order to continue making their art.

Society also needs artists to help explore diverse perspectives. Artworks can be informative, influential and possibly even transform social attitudes about certain issues. However, sometimes the moral and aesthetic judgements of an artwork will clash.

Leni Riefenstahl’s film Triumph of the Will is often described as aesthetically beautiful but morally evil.

The infamous 1935 propaganda documentary was commissioned by Adolf Hitler. In it, director Riefenstahl portrays the 1934 Nazi Party rally in Nuremberg, Germany as a glorious event and Hitler himself as God-like with a positive vision for his country. Unnervingly, the film is majestic, with beautiful cinematography and an emotive soundtrack underscored by nationalistic Wagner (who else?). It is awe-inspiring in its beauty and chilling in the way it glorifies the fascist Nazis.

In Triumph of the Will, the ‘immoral’ message – that Nazism is good and positive – interrupts our aesthetic appreciation of the work. It is difficult not to devalue Riefenstahl’s work based on its moral content.

Philosophers would generally rather teach people to think for themselves than apply strict censorship rules to artworks.

The moralist would claim that the moral value of an artwork does impact on our overall aesthetic judgement of the work. So does this mean artworks with a good moral message are elevated by their ethical content?

Moralists worry about the influence propaganda films may have in rallying impressionable people to harmful causes – like Nazism. Hitler was likely well aware of this when he commissioned the film. Correspondingly, artists’ concerns about censorship are also valid, if we consider who dictates what should or should not be seen.

Philosophers would generally rather teach people to think for themselves than apply strict censorship rules to artworks. That way, spectators are encouraged to engage critically with the messages they are receiving.

Critical spectatorship

Critical spectatorship is important in the case of biopics like The Big Short. The movie depicts a moral message we may well support, and the mass-market nature of film means it’s a powerful way to quickly take that message to a large number of people. But does it matter if the audience is viewing this narrative as they might a news story? Perhaps we should consider how viewers engage with the news.

Even when watching the broadcast news, viewers should be critical and consider what’s being shown or left out, from whose point of view the story is being told, and with whom or ‘what side’ we’re being positioned to identify. We need to constantly analyse or fact-check what we are told, particularly as we exist in a 24-hour news cycle and receive so much more information than previously.

As social media encourages quick likes and shares, it really is worth pausing to consider the impact such stories may have on others, on society and on our collective cultural myths. This is not to say that we should cease telling all the stories, far from it. But let’s also receive them critically, compassionately and open them up for discussion.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

Greer has the right to speak, but she also has something worth listening to

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

Violence and technology: a shared fate

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

Barbie and what it means to be human

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture, Politics + Human Rights

Taking the cynicism out of criticism: Why media needs real critique

BY Dr Laura D’Olimpio

Dr Laura D’Olimpio is senior lecturer in philosophy of education at the University of Birmingham, UK, and co-edits the Journal of Philosophy in Schools.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Australia is no longer a human rights leader

Australia is no longer a human rights leader

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + LeadershipPolitics + Human Rights

BY Georgie Bright The Ethics Centre 23 FEB 2016

On February 8, Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull announced the appointment of Philip Ruddock – the former immigration minister who presided over the Howard government’s notorious “Pacific Solution” to divert asylum seekers from its shores – as Australia’s first special envoy for human rights.

This surprising recycling of Ruddock is part of the government’s campaign for a seat at the United Nations Human Rights Council for the 2018-2020 term.

Not too long ago, then Prime Minister Tony Abbott said Australia was “sick of being lectured to” by the United Nations. But even the new government is demonstrating a willingness to dismiss inconvenient human rights obligations. In Human Rights Watch’s annual World Report – which documents human rights practices in more than 90 countries – Australia’s human rights record over the last year showed how far the country has to go.

It is difficult not to be disillusioned by the state of human rights in Australia. This is especially the case regarding the treatment of migrants and asylum seekers, and the discrimination faced by Indigenous Australians.

Australia’s candidacy for a seat at the Human Rights Council provides an important opportunity for Australia to address its domestic human rights issues.

Australia’s position on refugee protection has been to undermine and ignore international standards rather than uphold them. The country maintains a harsh boat turn-back policy, returning migrants and asylum seekers to countries including Indonesia, Sri Lanka, and Vietnam after only the most cursory of screenings.

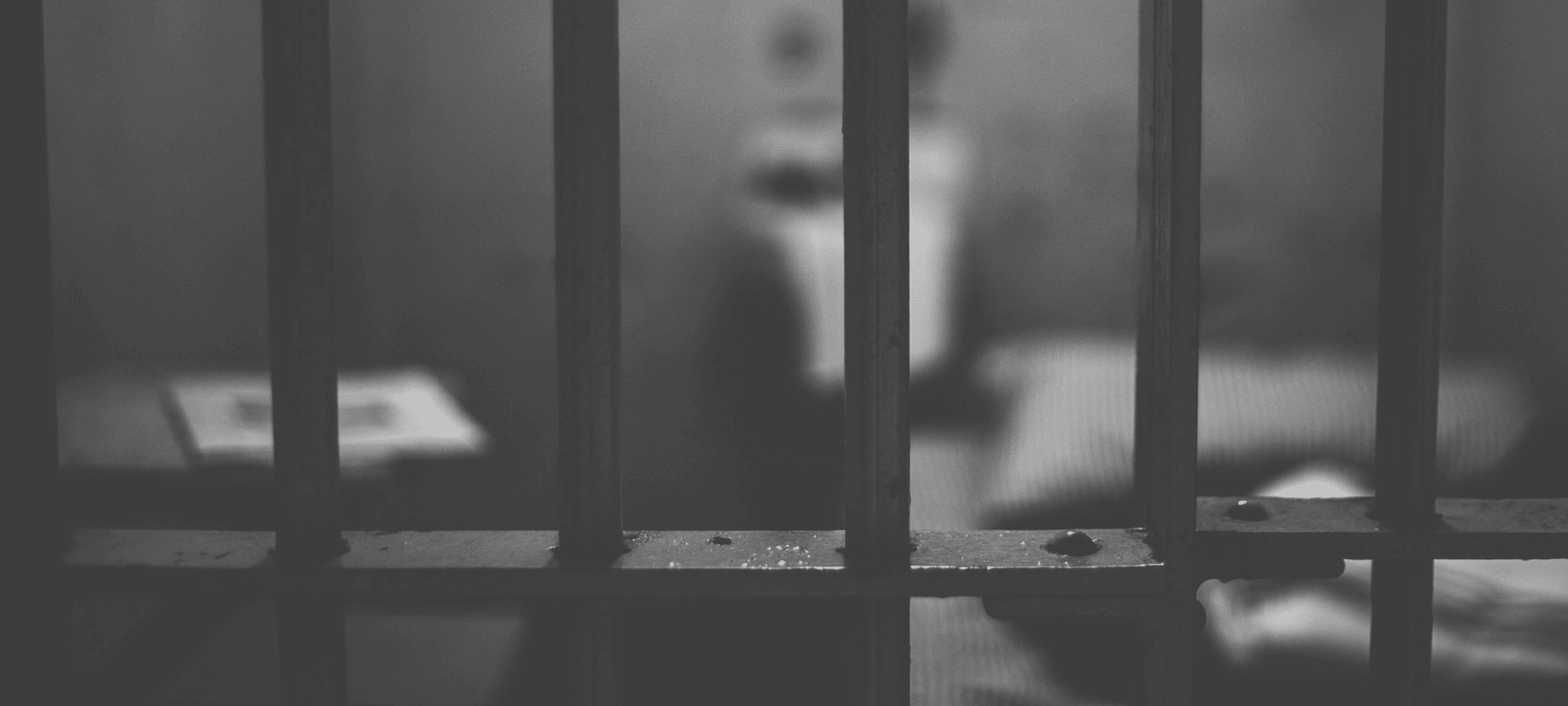

Australia has a policy of mandatory detention for all unauthorised arrivals, transferring migrants and asylum seekers to offshore processing sites in less-equipped countries such as Nauru and Papua New Guinea. An independent review and a report by the Australian Human Rights Commission found evidence of sexual and physical abuse of children on Nauru.

Instead of trying to ensure the safety of the asylum seekers and refugees in Australian immigration detention facilities, the government acted to limit public discussion of important refugee and migrant issues. It passed a law that makes it a crime punishable by two years jail if immigration service providers disclose “protected information”.

Following a ruling by the High Court, 267 asylum seekers in Australia, including 91 children, faced involuntary transfer to Nauru and Manus Island. The High Court ruled on narrow statutory grounds and did not consider Australia’s compliance with international refugee law.

Another area where Australia is falling behind is Indigenous rights. In November 2015, Australia appeared before the UN Human Rights Council to defend its rights record as part of the Universal Periodic Review process. Many countries urged Australia to address disadvantage and discrimination faced by Indigenous Australians. The government’s “Closing the Gap” report for 2016 highlighted mixed progress in meeting targets in education and health, with Indigenous Australians still living on average 10 years less than non-Indigenous Australians.

Indigenous Australians remain disproportionately represented in the criminal justice system, with Aboriginal women being the fastest growing prisoner demographic. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children under the age of 18 are overrepresented in youth detention facilities—representing more than half of child detainees.

Australia’s candidacy for a seat at the Human Rights Council provides an important opportunity for Australia to address its domestic human rights issues.

Australia is a vibrant democracy with a multicultural society and a solid history of protecting and promoting human rights values. Following the horror of World War II, Australia played an integral role in the development of the United Nations. In 1948, Australia’s Dr Herbert Vere Evatt, as president of the General Assembly, oversaw the adoption of the Universal Declaration on Human Rights.

But to regain the moral high ground and respect international law, Australia should urgently address these and other shortcomings in its human rights record. For starters, the government should stop transferring migrants and asylum seekers offshore, and provide them with fair and timely refugee status determination in Australia.

On Indigenous rights, it needs to intensify its commitment to addressing the underlying causes of gaps in opportunities and outcomes in health, education, housing and employment between Indigenous and non-indigenous and do more to address the high incarceration rate.

Australia once was an international human rights leader – and should be again.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Reports

Business + Leadership

Thought Leadership: Ethics at Work, a 2018 Survey of Employees

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

How we should treat refugees

Explainer

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Autonomy

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

Is the right to die about rights or consequences?

BY Georgie Bright

Georgie Bright is the Australia Associate Director for Development and Outreach at Human Rights Watch. Prior to joining Human Rights Watch, she worked in criminal law at Legal Aid Queensland. Georgie holds a law degree from Queensland University of Technology and obtained her Masters in International Human Rights Law at the University of York.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Ethics Explainer: Deontology

Deontology is an ethical theory that says actions are good or bad according to a clear set of rules.

Its name comes from the Greek word deon, meaning duty. Actions that align with these rules are ethical, while actions that don’t aren’t. This ethical theory is most closely associated with German philosopher, Immanuel Kant.

His work on personhood is an example of deontology in practice. Kant believed the ability to use reason was what defined a person.

From an ethical perspective, personhood creates a range of rights and obligations because every person has inherent dignity – something that is fundamental to and is held in equal measure by each and every person.

This dignity creates an ethical ‘line in the sand’ that prevents us from acting in certain ways either toward other people or toward ourselves (because we have dignity as well). Most importantly, Kant argues that we may never treat a person merely as a means to an end (never just as a resource or instrument).

Kant’s ethics isn’t the only example of deontology. Any system involving a clear set of rules is a form of deontology, which is why some people call it a “rule-based ethic”. The Ten Commandments is an example, as is the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

Most deontologists say there are two different kinds of ethical duties, perfect duties and imperfect duties. A perfect duty is inflexible. “Do not kill innocent people” is an example of a perfect duty. You can’t obey it a little bit – either you kill innocent people or you don’t. There’s no middle-ground.

Imperfect duties do allow for some middle ground. “Learn about the world around you” is an imperfect duty because we can all spend different amounts of time on education and each be fulfilling our obligation. How much we commit to imperfect duties is up to us.

Our reason for doing the right thing (which Kant called a maxim) is also important.

We should do our duty for no other reason than because it’s the right thing to do.

Obeying the rules for self-interest, because it will lead to better consequences or even because it makes us happy is not, for deontologists, an ethical reason for acting. We should be motivated by our respect for the moral law itself.

Deontologists require us to follow universal rules we give to ourselves. These rules must be in accordance with reason – in particular, they must be logically consistent and not give rise to contradictions.

It’s worth mentioning that deontology is often seen as being strongly opposed to consequentialism. This is because in emphasising the intention to act in accordance with our duties, deontology believes the consequences of our actions have no ethical relevance at all – a similar sentiment to that captured in the phrase “Let justice be done, though the heavens may fall”.

The appeal of deontology lies in its consistency. By applying ethical duties to all people in all situations the theory is readily applied to most practical situations. By focussing on a person’s intentions, it also places ethics entirely within our control – we can’t always control or predict the outcomes of our actions, but we are in complete control of our intentions.

Others criticise deontology for being inflexible. By ignoring what’s at stake in terms of consequences, some say it misses a serious element of ethical decision-making. De-emphasising consequences has other implications too – can it make us guilty of ‘crimes of omission’? Kant, for example, argued it would be unethical to lie about the location of our friend, even to a person trying to murder them! For many, this seems intuitively false.

One way of resolving this problem is through an idea called threshold deontology, which argues we should always obey the rules unless in an emergency situation, at which point we should revert to a consequentialist approach.

But is this a cop-out? How do we define ‘emergency’?

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Society + Culture

Respect for persons lost in proposed legislation

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Standing up against discrimination

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

Billionaires and the politics of envy

Big thinker

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Big Thinker: Dennis Altman

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

BY ethics

Ethics Explainer: Virtue Ethics

Virtue ethics is arguably the oldest ethical theory in the world, with origins in Ancient Greece.

It defines good actions as ones that display embody virtuous character traits, like courage, loyalty, or wisdom. A virtue itself is a disposition to act, think and feel in certain ways. Bad actions display the opposite and are informed by vices, such as cowardice, treachery, and ignorance.

For Aristotle, ethics was a key element of human flourishing because it taught people how to differentiate between virtues and vices. By encouraging examination, more people could live a life dedicated to developing virtues.

It’s one thing to know what’s right, but it’s another to actually do it. How did Aristotle advise us to live our virtues?

By acting as though we already have them.

Excellence as habit

Aristotle explained that both virtues and vices are acquired by repetition. If we routinely overindulge a sweet tooth, we develop a vice — gluttony. If we repeatedly allow others to serve themselves dinner before us, we develop a virtue – selflessness.

Virtue ethics suggests treating our character as a lifelong project, one that has the capacity to truly change who we are. The goal is not to form virtues that mean we act ethically without thinking, but to form virtues that help us see the world clearly and make better judgments as a result.

In a pinch, remember: vices distort, virtues examine.

A quote most of the internet attributes to Aristotle succinctly reads: “We are what we repeatedly do. Excellence, then, is not an act, but a habit”.

Though he didn’t actually say this, it’s a good indication of what virtue ethics stands for. We can thank American philosopher, Will Durant, for the neat summary.

Aim for in between

There are two practical principles that virtue ethics encourages us to use in ethical dilemmas. The first is called The Golden Mean. When we’re trying to work out what the virtuous thing to do in a particular situation is, look to what lies in the middle between two extreme forms of behaviour. The mean will be the virtue, and the extremes at either end, vices.

Here’s an example. Imagine your friend is wearing a horrendous outfit and asks you how they look. What are the extreme responses you could take? You could a) burst out laughing or b) tell them they look wonderful when they don’t.

These two extremes are vices – the first response is malicious, the second is dishonest. The virtuous response is between these two. In this case, that would be gently — but honestly — telling your friend you think they’d look nicer in another outfit.

Imagination

The second is to use our imagination. What would we do if we were already a virtuous person? By imagining the kind of person we’d like to be and how we would want to respond we can start to close the gap between our aspirational identity and who we are at the moment.

Virtue ethics can remind us of the importance of role models. If you want someone to learn ethics, show them an ethical person.

Some argue virtue ethics is overly vague in guiding actions. They say its principles aren’t specific enough to help us overcome difficult ethical conundrums. “Be virtuous” is hard to conceptualise. Others have expressed concern that virtues or vices aren’t agreed on by everybody. Stoicism or sexual openness can be a virtue to some, a vice to others.

Finally, some people think virtue ethics breeds ‘moral narcissism’, where we are so obsessed with our own ethical character that we value it above anyone or anything else.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships

The role of the ethical leader in an accelerating world

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

The self and the other: Squid Game’s ultimate choice

Explainer

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Critical Race Theory

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

Meet Eleanor, our new philosopher in residence

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Ethics Explainer: Consequentialism

Consequentialism is a theory that says whether something is good or bad depends on its outcomes.

An action that brings about more benefit than harm is good, while an action that causes more harm than benefit is not. The most famous version of this theory is utilitarianism.

Although there are references to this idea in the works of ancient philosopher Epicurus, it’s closely associated with English philosopher Jeremy Bentham.

Bentham’s theory of utilitarianism focussed on which actions were most likely to make people happy. If happiness was the experience of pleasure without pain, the most ethical actions were ones that caused the most possible happiness and the least possible pain.

He even developed a calculator to work out which actions were better or worse – the ‘felicific calculus’. Because it counted every person’s pleasure or pain as the same, regardless of age, wealth, race, etc. utilitarianism could be seen as a radically egalitarian philosophy.

Bentham’s views are most closely aligned with act utilitarianism. This basic form of consequentialism holds an action as ethical if and only if it produces more beneficial/pleasure-causing outcomes than negative/pain-causing ones. Whenever we are faced with a decision, an act consequentialist will expect us to ask that question.

John Stuart Mill, a student of Bentham’s, disagreed. He believed it was too difficult for a society to run if it had to consider the specific costs/benefits of every single action. How could we have speeding laws, for example, if it would sometimes be ethical to break the speed limit?

Instead, Mill believed we should figure out which set of rules would create the most happiness over an extended period of time and then apply those in every situation. This was his theory of rule utilitarianism.

According to this theory, it would be unethical for you to speed on an empty street at two o’clock in the morning. Even if nobody would be hurt, our speeding laws mean less people are harmed overall. Keeping to those rules ensures that.

Consequentialism is an attractive ethical approach because it provides clear and practical guidance – at least in situations where outcomes are easy to predict. The theory is also impartial. By asking us to maximise benefit for the largest number of people (or, for Peter Singer and other preference utilitarians, creatures who have preferences), we set aside our personal biases and self-interest to benefit others.

One problem with the theory is that it can be hard to measure different benefits to decide which one is morally preferable. Is it better to give my money to charity or spend it studying medicine so I can save lives? Many forms of consequentialism have been proposed that attempt to deal with the issue of comparing moral value.

The other concern people express is the tendency of consequentialism to use ‘ends justify the means’ logic. If all we are concerned with is getting good outcomes, this can seem to justify harming some people in order to benefit others. Is it ethical to allow some people to suffer so more people can live well?

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Naturalistic Fallacy

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Blame

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

To deal with this crisis, we need to talk about ethics, not economics

Big thinker

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Big Thinker: Confucius

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

The myths of modern motherhood

The myths of modern motherhood

Opinion + AnalysisHealth + WellbeingRelationships

BY Dr Camilla Nelson The Ethics Centre 12 FEB 2016

It seems as if three successive waves of feminism haven’t resolved the chronic mismatch between the ideal of the ‘good’ and ‘happy’ mother and the realities of women’s lives.

Even if you consciously reject them, ideas about what a mother ought to be and ought to feel are probably there from the minute you wake up until you go to bed at night. Even in our age of increased gender equality it seems as if the culture loves nothing more than to dish out the myths about how to be a better mother (or a thinner, more fashionable, or better-looking one).

It’s not just the celebrity mums pushing their prams on magazine covers, or the continuing dearth of mothers on TV who are less than exceptionally good-looking, or that mothers in advertising remain ubiquitously obsessed with cleaning products and alpine-fresh scents. While TV dramas have pleasingly increased the handful of roles that feature working mothers, most are unduly punished in the twists of the melodramatic plot. They have wimpy husbands or damaged children, and of course TV’s bad characters are inevitably bad due to the shortcomings of their mothers (serial killers, for example, invariably have overbearing mothers or alcoholic mothers, or have never really separated from their mothers).

It seems we are living in an age of overzealous motherhood. Indeed, in a world in which the demands of the workplace have increased, so too the ideals of motherhood have become paradoxically more – not less – demanding. In recent years, commonly accepted ideas about what constitutes a barely adequate level of mothering have dramatically expanded to include extraordinary sacrifices of time, money, feelings, brains, social relationships, and indeed sleep.

In Australia, most mothers work. But recent studies show that working mothers now spend more time with their children than their non-working mothers did in 1975. Working mothers achieve this extraordinary feat by sacrificing leisure, mental health, and even personal hygiene to spend more time with their kids.

This is coupled with a new kind of anxious sermonising that is having a profound impact on mothers, especially among the middle class. In Elisabeth Badinter’s book The Conflict, she argues that an ideology of ‘Naturalism’ has given rise to an industry of experts advocating increasingly pristine forms of natural birth and natural pregnancy, as well as an ever-expanding list of increasingly time-intensive child rearing duties that are deemed to fall to the mother alone. These duties include most of the classic practices of 21st century child rearing, including such nostrums as co-sleeping, babywearing and breastfeeding-on-demand until the age of two.

It seems we are living in an age of overzealous motherhood.

Whether it is called Intensive Mothering or Natural Parenting, these new credos of motherhood are wholly taken up with the idea that there is a narrowly prescribed way of doing things. In the West, 21st century child rearing is becoming increasingly time-consuming, expert-guided, emotionally draining, and incredibly expensive. In historical terms, I would be willing to hazard a guess that never before has motherhood been so heavily scrutinised. It is no longer just a question of whether you should or should not eat strawberries or prawns or soft cheese, or, heaven forbid, junk food, while you are pregnant, but so too, the issue of what you should or should not feel has come under intense scrutiny.

Never before has there been such a microscopic investigation of a pregnant woman’s emotional state, before, during and after birth. Indeed, the construction of new psychological disorders for mothers appears to have become something of a psychological pastime, with the old list of mental disorders expanding beyond prenatal anxiety, postnatal depression, postpartum psychosis and the baby blues, to include the baby pinks (a label for a woman who is illogically and inappropriately happy to be a mother), as well as Prenatal and Postnatal Stress Disorder, Maternal Anxiety and Mood Imbalance and Tokophobia—the latter being coined at the start of this millennium as a diagnosis for an unreasonable fear of giving birth.

The problem with the way in which this pop psychology is played out in the media is that it performs an endless re-inscription of the ideologies of mothering. These ideologies are often illogical, contradictory and – one suspects – more often dictated by what is convenient for society and not what is actually good for the children and parents involved. Above all else, mothers should be ecstatically happy mothers, because sad mothers are failed mothers. Indeed, according to the prevailing wisdom, unhappy mothers are downright unnatural, if not certifiably insane.

Never before has motherhood been so heavily scrutinised.

Little wonder there has been an outcry against such miserable standards of perfection. The same decade that saw the seeming triumph of the ideologies of Intensive and Natural mothering, also saw the rise of what has been called the ‘Parenting Hate Read’ — a popular outpouring of books and blogs written by mothers (and even a few fathers) who frankly confess that they are depressed about having children for no better reason than it is often mind-numbing, exhausting and dreadful. Mothers love their children, say the ‘Parenting Hate Reads’, but they do not like what is happening to their lives.

The problem is perhaps only partly about the disparity between media images of ecstatically happy mummies and the reality of women’s lives. It is also because our ideas about happiness have grown impoverished. Happiness, as it is commonly understood in the western world, is made up of continuous moments of pleasure and the absence of pain.

These popular assumptions about happiness are of comparatively recent origin, emerging in the works of philosophers such as Jeremy Bentham, who argued in the 18th century that people act purely in their self-interest and the goal to which self-interest aspires is happiness. Ethical conduct, according to Bentham and James Mill (father to John Stuart), should therefore aspire to maximise pleasure and minimise pain.

Our ideas about happiness have grown impoverished.

This ready equation of goodness, pleasure and happiness flew in the face of ideas that had been of concern to philosophers since Aristotle argued that a person is not made happy by fleeting pleasures, but by fulfilment stemming from meaning and purpose. Or, as Nietzsche, the whirling dervish of 19th century philosophy, put it, “Man does not strive for happiness – only the Englishman does”.

Nevertheless, Western assumptions about happiness have remained broadly utilitarian, giving rise to the culturally constructed notion of happiness we see in TV commercials, showing families becoming happier with every purchase. Or by life coaches peddling the dubious hypothesis that self-belief can overcome the odds, whatever your social or economic circumstance.

Unless you are Mother Teresa, you have probably been spending your life up until the time you have children in a reasonably independent and even self-indulgent way. You work hard through the week but sleep in on the weekend. You go to parties. You come home drunk. You see your friends when you want. Babies have different ideas. They stick forks in electric sockets, go berserk in the car seat, and throw up on your work clothes. They want to be carried around in the day and wake in the night.

If society can solve its social problems then maybe parenting will cease to be a misery competition. Mothers might not be happy in a utilitarian or hedonistic sense but will lead rich and satisfying lives. Then maybe a stay-at-home dad can change a nappy without a choir of angels descending from heaven singing ‘Hallelujah’.

This is an edited extract from “On Happiness: New Ideas for The 21st Century” UWA Publishing.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Explainer

Health + Wellbeing, Society + Culture

Ethics Explainer: Logical Fallacies

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Free speech has failed us

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture, Relationships

Stoicism on Tiktok promises happiness – but the ancient philosophers who came up with it had something very different in mind

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Violent porn and feminism

BY Dr Camilla Nelson

Dr Camilla Nelson is a Senior Lecturer in Writing at the University of Notre Dame Australia.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Ending workplace bullying demands courage

Ending workplace bullying demands courage

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + LeadershipHealth + WellbeingRelationships

BY Petrina Coventry The Ethics Centre 5 FEB 2016

Despite increasing measures to combat workplace harassment, bullies remain entrenched in organisations. Changes made to laws and regulations in order to stamp out bullying have instead transformed it into an underground set of behaviours. Now hidden, these behaviours often remain unaddressed.

In other cases, anti-bullying policies can actually work to support perpetrators. Where regulations specify what bullying is, some people will cleverly use those rules as a guide to work around. Although these people are no longer bullying in the narrow sense outlined by policies or regulations, their acts of shunning, scapegoating and ostracism have the same effect. Rules that explicitly define bullying create exemptions, or even permissions, for behaviours that do not meet the formal standard.

Because they are more difficult to notice or prove, these insidious behaviours can remain undetected for long periods. As Kipling Williams and Steve Nida argued in a 2011 research paper, “being excluded or ostracized is an invisible form of bullying that doesn’t leave bruises, and therefore we often underestimate its impact”.

The bruises, cuts and blows are less evident but the internal bleeding is real. This new, psychological violence can have severe, long-term effects. According to Williams, “Ostracism or exclusion may not leave external scars, but it can cause pain that often is deeper and lasts longer than a physical injury”.

Bullies tend to be very good at office politics and working upwards, and attack those they consider rivals through innuendo and social networks.

This is a costly issue for both individuals and organisations. No-one wins. Individuals can suffer symptoms akin to Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder. Organisations in which harassment occurs must endure lost time, absences, workers’ compensation claims, employee turnover, lack of productivity, the risk of costly and lengthy lawsuits, as well as a poor reputation.

So why does it continue?

First, bullies tend to be very good at office politics and working upwards, and attack those they consider rivals through innuendo and social networks. Bullies are often socially savvy, even charming. Because of this, they are able to strategically abuse co-workers while receiving positive work evaluations from managers.

In addition, anti-bullying policies aren’t the panacea they are sometimes painted to be. If they exist at all they are often ignored or ineffective. A 2014 report by corporate training company VitalSmarts showed that 96 percent of the 2283 people it surveyed had experienced workplace bullying. But only 7 percent knew someone who had used a workplace anti-bullying policy – the majority didn’t see it as an option. Plus, we now know some bullies use such policies as a base to craft new means of enacting their power – ones that aren’t yet defined as bullying behaviour by these policies.

Finally, cases often go unreported, undetected and unchallenged. This inaction rewards perpetrators and empowers them to continue behaving in the same way. This is confusing for the victim, who is stressed, unsure, and can feel isolated in the workplace. This undermines the confidence they need to report the bullying. Because of this, many opt for a less confrontational path – hoping it will go away in time. It usually doesn’t.

Cases often go unreported, undetected and unchallenged. This inaction rewards perpetrators and empowers them to continue behaving in the same way.

What can you do if a colleague is being shunned or ostracised by peers or managers? The first step is not to participate. However, most people are already likely to be aware of this. More relevant for most people is to not become complicit by remaining silent. As 2016 Australian of the Year David Morrison famously said, “The standard you walk by is the standard you accept.”

The onus is on you to take positive steps against harassment where you witness it. By doing nothing you allow psychological attacks to continue. In this way, silent witnesses bear partial responsibility for the consequences of bullying. Moreover, unless the toxic culture that enables bullying is undone, logic says you could be the next victim.

However, merely standing up to harassment isn’t likely to be a cure-all. Tackling workplace bullying is a shared responsibility. It takes regulators, managers and individuals in cooperation with law, policy and healthy organisational culture.

The onus is on you to take positive steps against harassment where you witness it. By doing nothing you allow psychological attacks to continue.

Organisational leaders in particular need to express public and ongoing support for clearly worded policies. In doing so, policies begin to shape and inform the culture of an organisation rather than serving as standalone documents. It is critical that managers understand the impacts of bullying on culture, employee wellbeing, and their own personal liability.

When regulation fails – the dilemma most frequently seen today – we need to depend on individual moral character. Herein lies the ethical challenge. ‘Character’ is an underappreciated ethical trait in many executive education programs, but the moral virtues that form a person’s character are the foundation of ethical leadership.

A return to character might diminish the need for articles like this. In the meantime, workplace bullying provides us all with the opportunity to practise courage.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Society + Culture

Does your body tell the truth? Apple Cider Vinegar and the warning cry of wellness

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Is it fair to expect Australian banks to reimburse us if we’ve been scammed?

Opinion + Analysis

Science + Technology, Relationships

Love and the machine

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

The new normal: The ethical equivalence of cisgender and transgender identities

BY Petrina Coventry

Petrina Coventry is Industry Professor and Director of Development with the University of Adelaide Faculty of the Professions and the Business School. She previously held global vice president roles with the General Electric Company and The Coca Cola Company in the United States and Asia and was most recently CHRO with Santos Ltd.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

What your email signature says about you

What your email signature says about you

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + LeadershipHealth + Wellbeing

BY The Ethics Centre 2 FEB 2016

Getting too many unethical business requests? Sreedhari Desai’s research suggests a quote in your email signature may be the answer to your woes.

In a recent study Desai enrolled subjects to participate in a virtual game to earn money. The subjects were told they’d earn more money if they could convince their fellow players to spread a lie without knowing about it. Basically, subjects had to trick their fellow players into believing a lie, and then get those other players to spread the lie around the game.

What subjects didn’t know is that all their fellow ‘players’ were in fact researchers studying how they would go about their deception. Subjects communicated with the researchers by email. Some researchers had a virtuous quote underneath their email – “Success without honor is worse than fraud”. Others had a neutral quote in their email signature – “Success and luck go hand in hand”. Others had no quote at all.

And wouldn’t you know it? Subjects were less likely to try to recruit people with a virtuous quote in their email. The quote served as a “moral symbol”, shielding the person from receiving unethical requests from other players. In an interview with Harvard Business Review, Desai outlines what’s happening in these situations:

When someone is in a position to request an unethical thing, they may not consciously be thinking, “I won’t ask that person.” Instead, they may perceive a person as morally “pure” and feel that asking them to get “dirty” makes an ethical transgression even worse. Or they may be concerned that someone with moral character will just refuse the request.

So, if you want to keep your hands clean it may be as simple as updating your email signature. It won’t guarantee you’ll do the right thing when you’re tempted (there’s more to ethics than pretty words!) but it will ensure you’re tempted less.

There are other, more expensive ways to avoid unethical approaches via email.

And in case you’re looking for a virtuous quote for your email signature, we surveyed some of our staff for their favourite virtuous quotes. Here’s a sample:

- “The unexamined life is not worth living” – Socrates

- “No man wishes to possess the whole world if he must first become someone else” – Aristotle

- “Protect me from what I want” – Jenny Holzer

- “A true man goes on to the end of his endurance and then goes twice as far again” – Norwegian proverb

- “Knowledge is no guarantee of good behaviour, but ignorance is a virtual guarantee of bad behaviour” – Martha Nussbaum

A small disclaimer to all of this – it might not work if you work with Australians. Apparently our propensity to cut down tall poppies and our discomfort for authority extend to moral postulations in email signatures. Instead of sanctimony, Aussies are likely to protect people with fun or playful quotes in their emails. Desai explains:

“We’re studying how people react to moral symbols in Australia. Our preliminary study showed that people there were sceptical of moral displays. They seemed to think the bloke with the quote was being ‘holier than thou’ and probably had something to hide.”

So, as well as your favourite virtuous quote, you might want to bung a joke on the bottom of your emails to please your sceptical Antipodean colleagues, lest they lead you into temptation.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

You are more than your job

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships

There are ethical ways to live with the thrill of gambling

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Is there such a thing as ethical investing?

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

People with dementia need to be heard – not bound and drugged

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

What comes after Stan Grant’s speech?

What comes after Stan Grant’s speech?

Opinion + AnalysisPolitics + Human RightsSociety + Culture

BY The Ethics Centre 25 JAN 2016

Stan Grant’s speech broke your heart – five views on what to do about it.

1) Tanya Denning-Orman say’s It’s not hard to capitalise on Grant’s momentum.

Last year Stan Grant delivered an address that left a crowd of hundreds speechless. This week, those same words jumped out of computer screens and into the hands of ordinary Australians and polarised millions of lounge room commentators. When this happened, he forced an entire nation to confront a history that no one wants to talk about.

He made you uncomfortable because he put a human face to the stats and figures that so commonly define First Nations peoples. Stan reminded you that we are people of law, lore, music, art and politics, and he inspired you to reimagine who we all are as Australians.

Yesterday, commentators described the impact of this speech as a “Martin Luther King moment”. Today, those of us who live it know that it’s all come and gone before. Noel Pearson delivered a speech that commentators said would be spoken about for years. In the months that followed, there was silence. With just a few words Charlie Perkins could mobilise crowds to take to the streets. Is it that easy to forget?

Knowing this, tomorrow the challenge will be that this momentum, created by a Wiradjuri man, doesn’t drown in a sea of barbecues and beers that is ‘Australia Day’. Just as Stan Grant said, we are better than this.

This time let the power of the word inspire you to make a change beyond ‘a thumbs up’ on a post and clicking the share button. We can insist that schools teach Australia’s silenced history. We can hold our governments to account. We can be empowered by our shared story.

Never before have we been so connected – we can create a global movement through our fingertips.

And I’ll let you in on a little secret. It’s not that hard to do.

Tanya Denning-Orman is the Channel Manager for NITV. Follow her on Twitter @Tanyadenning.

2) Luke Pearson argues that sentiment isn’t social justice. Now is the time to do something

The worry with making white people ‘feel all the feels’ as we sometimes say online, is that it won’t lead to any change in thought, behaviour or actual contributions to the work that needs to be done. Worse, it can actually do the opposite.

White people’s emotional experiences are all too often used to validate privilege and identify themselves as ‘one of the good ones’. This shifts the responsibility to act away from them and onto ‘those other people’.

Novelist Teju Cole labelled this phenomenon the ‘White Saviour Industrial Complex’, saying “The White Saviour Industrial Complex is not about justice. It is about having a big emotional experience that validates privilege.”

This response gives people the moral authority to continue to justify racist responses that make them feel good about their privilege and direct and indirect contributions to racism and oppression. This attitude is what all too often justifies brutal government responses to complex problems.

In Australia this takes the form of punitive approaches to an endless list of humanitarian issues. The NT Intervention, offshore detention, military action overseas, Aboriginal deaths in custody, and increased rates of Indigenous child removal and incarceration whilst simultaneously defunding strategies to reduce these numbers…

This attitude leads people to get upset or feel attacked whenever white privilege is mentioned. They remove themselves from any responsibility purely by virtue of their emotional experiences, not recognising they are the ones who benefit most from their emotional experiences.

The very same people who claim to be our biggest supporters still argue that “we need to stop talking about race” rather than arguing “we need to stop racism”. They say “we are all Australians” without seeing the irony – erasing the identity of others was the outcome intended by culture genocide and assimilationist ideals. They feel betrayed when this is challenged because they feel they are owed for the emotional experiences they have felt.

If your response to videos like Stan Grant’s speech is to pat yourself on the back for a job well done without actually considering your place in the status quo and whether or not your ideas are just rebranded versions of the racism people have been fighting against for centuries, you are a part of the problem.

The same goes if you recognise the above but don’t actually do anything to change things. If you sit silently when you see racism within your own family, your workplace, your social group… If you don’t support those who work at the coalface, addressing the ongoing impacts of colonialism or who work at the highest levels trying to prevent it from continuing…

You are part of the problem.

“I deeply respect American sentimentality, the way one respects a wounded hippo. You must keep an eye on it, for you know it is deadly”, writes Teju Cole.

Ditto for Australia.

Luke Pearson is the Founder of IndigenousX, indigenousx.com.au. Follow them on Twitter @IndigenousX.

3) Anita Heiss anticipates that the real power of Stan’s speech is yet to come

As part of the debate, Stan Grant’s words were powerful. They were honest. They came from the heart and they were passionate. Unfortunately, for many of us they were not something new. They were words we had said ourselves in vain, similar to words we had heard from our parents and our peers. And so, we watched and sat in pain yet again at the reality of what is our great Australian nightmare.

For me the importance of Stan’s speech is that it has managed to reach a global audience. It has been heard by some who, for whatever reason, knew nothing about the facts Stan, a strong Wiradjuri man, was sharing as part of a debate that, in all honesty, was not much of a debate.

Words can be powerful. They can make us change the way we think. They can help us understand and feel empathy, but what are words without actions? I think the real power will come now, post Stan’s speech in a call to action to all those tweeting and facebooking to actually do something!

Teachers, watch the entire debate with your students. Get them to discuss, debate and talk about the issues raised. Parents, do the above also!

Corporates, politicians, policy makers, what are you doing in your worlds to address the inequities Stan mentioned? Immortality rates, incarceration rates, the ongoing removal of children?

Re-tweeting is not enough! You cannot claim to want equality for Indigenous Australians if you are not prepared to participate in the change – the actions – required to make that happen.

Build partnerships with Indigenous organisations that are already working in the areas you have influence in. Form lasting strategies to create the change this country needs. But please know, it’s not going to be easy, or going to be fixed overnight. Over 200 years of damage needs to be repaired to make the nightmare a dream.

Dr Anita Heiss is a proud member of the Wiradjuri nation. She is an author and Manager of the Epic Good Foundation. Follow her on Twitter @AnitaHeiss.

4) Kelly Briggs feels that we’ve had ‘Stan Grant moments’ before

I am confounded that some are comparing Stan Grant’s much admired speech from the IQ2 debate last year on Australia’s racism to Martin Luther King. Doing so erases Aboriginal activists who have come before us, including Dr Charlie Perkins.

Perkins headed what is now known as the ‘Freedom Rides’ – a busload of Sydney University students who toured particularly racist northern New South Wales towns to shine a spotlight on the heinous racism and segregation between blacks and whites in 1965. His passionate activism in towns, pubs, RSLs, swimming pools and the like saw changes to many rules and regulations.

Now that Stan Grant’s speech has gone ‘viral’, will it engender any changes to current governmental policies? Put back any of the money ripped out of the budget allocated to Aboriginal programs and issues? Create a much needed conversation about Australia’s ongoing overt and casual racism?

I don’t think it will. Stan Grant, while passionate, has not added anything new to what Aboriginal people have been saying in blogs, news articles and on social media for the better part of a decade. So, while I admire Stan’s stance, I do not hold out any hope that it will not be forgotten in a week, or that it will make a difference.

Kelly Briggs blogs at thekooriwoman.wordpress.com. Follow her on Twitter @TheKooriWoman.

5) Siv Parker on why we haven’t done this before

We haven’t had enough feel-good moments cast around Aboriginal Australia for this nation to be in a position to waste one. So where to from here?

An icebreaker may help to shake off a few nerves. It would be easier on all of us if we took a breath and agreed that we haven’t done this before.

Bridge walks, town meetings, community events, the apology and the land help to give us all our bearings.

But a digital world makes it easier to satisfy a yearning for substance, to extend ourselves beyond fleeting online interactions.

The anticipated referendum around constitutional reform is a hook on which to hang our shared history. I have no doubt we can agree to include Indigenous Australians in the constitution. I am not the only one willing to make a start on talking about what that could look like.

We won’t need to invoke great moments from foreign countries to define us, we can create our own. Indigenous people are on the crest of a wave in asserting ourselves in words, art, performances and knowledge systems that has been decades in the making. This nation can do better. That is the promise within our ancient storytelling tradition. A story is not a one-sided affair. We don’t listen to a story, we become a part of it. In years to come, they will continue to tell stories that includes us all.

Siv Parker is an award-winning writer and blogger. Follow her on Twitter @SivParker.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture, Relationships

Stoicism on Tiktok promises happiness – but the ancient philosophers who came up with it had something very different in mind

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

What Harry Potter teaches you about ethics

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

Power without restraint: juvenile justice in the Northern Territory

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

Barbie and what it means to be human

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

How should vegans live?

How should vegans live?

Opinion + AnalysisClimate + EnvironmentHealth + Wellbeing

BY XAVIER COHEN The Ethics Centre 24 JAN 2016

Ethical vegans make a concerted lifestyle choice based on ethical – rather than, say, dietary – concerns. But what are the ethical concerns that lead them to practise veganism?

In this essay, I focus exclusively on that significant portion of vegans who believe consuming foods that contain animal products to be wrong because they care about harm to animals, perhaps insofar as they have rights, perhaps just because they are sentient beings who can suffer, or perhaps for some other reason.

Throughout the essay, I take this conviction as a given, that is, I do not evaluate it, but instead investigate what lifestyle is in fact consistent with caring about harm to animals, which I will begin by calling consistent veganism. I argue that the lifestyle that consistently follows from this underlying conviction behind many people’s veganism is in fact distinct from a vegan lifestyle.

It is probably the case that one cannot live without causing harm to animals due to the trade-off in welfare between other animals who are harmed by one’s own consumption.

Let us also begin by interpreting veganism in the way that many vegans – and most who are aware of veganism – would. A vegan consumes a diet containing no animal products. In conceiving of veganism in terms of what a diet contains, there seems to be an intuition about the moral relevance of directness, according to which it matters how direct the harm caused by the consumption of the food is with regards to the consumption of the food.

On this intuition, eating a piece of meat is worse than eating a certain amount of apples grown with pesticides that causes the same amount of harm, because the harm in the first case seems to be more directly related to the consumption of the food than in the second case. Harm from the pesticides seems to be a side-effect of eating the food, whereas the death of the animal for meat seems to be a means to the eating food.

Even if we grant this intuition to be a good in this case, it is not good in the case where the harm is greater from the apples than from the meat. To eat the apples in this case is to not put one’s care about harm to animals first, which means going against the only thing that should motivate a consistent vegan.

Here, our intuition about the amount of harm caused is what seems to matter; if what we care about is harm to animals, then we should cause less rather than more harm to animals, and therefore, from the moral point of view, it seems that it is better to eat the meat than the apples. Let the conviction in this intuition be called the ‘less-is-best’ thesis.

Therefore, the intuition about the directness of the harm is only potentially relevant in situations where one has to choose between alternatives that cause the same amount of harm, or in situations where one does not know which causes more harm. The rest of the time, it seems that consistent vegans should not care about the directness of the harm, but instead care only about causing less rather than more harm to animals.

Consistent vegans should not care about the directness of the harm, but instead care only about causing less rather than more harm to animals.

This requires an awareness of harm that extends further than relatively common considerations noted by vegans regarding animal products being used in the production process for—but not being contained in—foodstuffs like alcoholic drinks. Caring about harm to animals means caring about, less directly, accidental harm to (usually very small) animals from the harvesting process, and from products that have a significant carbon footprint, and thereby contribute to (and worsen) climate change, which is already starting to lead to countless deaths and harm to animals worldwide.

However, caring about harm to animals cannot plausibly require consistent vegans to cause no harm at all to animals. If it did, then in light of the last two examples given above, it seems it would require consistent veganism to be a particularly ascetic kind of prehistoric or Robinson Crusoe-type lifestyle, which would clearly be far too demanding.

In fact, it is probably the case that one cannot live without causing harm to animals due to the trade-off in welfare between other animals who are harmed by one’s own consumption, and oneself (an animal) who is harmed if one cannot consume what one needs to survive. But it is definitely the case that all humans could not survive if no harm to other animals could be caused; this means that either human animals or non-human animals will be harmed regardless of how we live.

We could not all be morally obligated to live in such a way that we could not in fact all live. Therefore, due to this argument and due to such a lifestyle being over-demanding, there are two sufficient arguments for why causing some harm to animals is morally permissible.

If it is the case that causing some harm to animals is morally permissible, then there is no clear reason why there should be a categorical difference in the moral status of acts – such as impermissibility, permissibility, and obligation – with regards to how they harm animals, apart from when these categorical differences arise only from vast differences in the amount of harm caused by different acts.

One’s care for animals should be further-reaching: rather than merely caring about harm one causes, a consistent vegan should care about acting or living in a way that leads to less rather than more harm to animals.

So, for example, shooting a vast number of animals merely for the pleasure of sport may well be impermissible, but only insofar as it causes a much greater amount of harm than alternative acts that one could reasonably do instead of hunting. It seems that the most reasonable position, then, which is in line with the less-is-best thesis, is that the morality of harm to animals is best viewed on a continuum on which causing less harm to animals is morally better and causing more harm to animals is morally worse, where the difference in morality is linked only to the difference in the amount of harm to animals.

Hitherto, I have said that it seems to be the case that consistent vegans care about causing less rather than more harm to animals. However, I claim that the less-is-best thesis should in fact be interpreted as having a wider application than merely harm caused by our actions or life lived. One’s care for animals should be further-reaching: rather than merely caring about harm one causes, a consistent vegan should care about acting or living in a way that leads to less rather than more harm to animals. The latter includes a concern about harm caused by others that one can prevent, which the former excludes as it is not harm caused by oneself.

The impact of social interaction on people’s lifestyles is an important way in which consistent vegans can act or live in a way that leads to less rather than more harm to animals. That nearly all vegans are in fact vegans because they were previously introduced to vegan ideas by others – rather than coming by them and becoming vegan through sheer introspection – is testimony to the impact of social interaction on people’s lifestyles, which in turn can be more or less harmful to animals.

If this recommended lifestyle is too demanding, many will reject it or simply not change, meaning that these people will continue to harm animals.

Consistent vegans have the potential to build a broad social movement that encourages many others to lead lives that cause less harm to animals. But in order to do this, consistent vegans will have to persuade those who do not care about harm to animals (or let care about harm to animals impact their lifestyle) to lead a different kind of lifestyle, and if this recommended lifestyle is too demanding, many will reject it or simply not change, meaning that these people will continue to harm animals.

The vegan lifestyle may seem too hard for many people

If these people are more likely to make lifestyle changes if the lifestyle suggested to them is less demanding, which for many – and probably a vast majority – will be the case, then consistent vegans could bring about less harm to animals if they try to persuade these people to live lifestyles that optimally satisfy the trade-off between demandingness and personal harm to animals. This lifestyle that consistent vegans should attempt to persuade others to follow I shall call “environmentarianism”.

Why ‘environmentarianism’? And what is the content of environmentarianism? Care about harm to animals can be framed in terms of care for the environment, as the environment is partially – and in a morally important way—constituted by animals. This can be easily – and I believe quite intuitively – communicated to those who do care about harm to animals, and those who do not are likely to be more swayed by arguments that are framed in terms of concern for the environment than for animals. Concern for oneself, one’s loved ones, and one’s species – things that most people care greatly about – may be more easily read into the former than the latter, especially in light of impending climate change.

Environmentarianism, then, is the set of lifestyles that seek to reduce harm done to the environment (which is conceived in terms of harm to animals for consistent vegans) – as this matters morally for environmentarians – regardless of which sphere of life this reduction of harm comes from. Be it rational or not, ascribing the title and social institution of ‘environmentarian’ to one’s life will, for many, make them more likely to lead a life that is more in line with caring about harm to animals; people often attach themselves to these titles, as the dogmatic behaviour of many vegans shows.

Some may prefer to reduce total harm to animals by a given amount by making the sacrifice of having a vegan diet, but not compromising on their regular car journey to work, whilst others may find taking on the latter easier than maintaining the strict vegan diet.

Moreover, environmentarianism can be practised to a more or less radical – and thus moral – extent. Some may prefer to reduce total harm to animals by a given amount by making the sacrifice of having a vegan diet, but not compromising on their regular car journey to work, or perhaps by opting out of what for them may be uncomfortable proselytising, whilst others may find taking on the latter two easier than maintaining the strict vegan diet (that they perhaps used to have). Some may reduce total harm by an even greater amount – and hence lead a morally better lifestyle – by having a vegan diet and by refraining from harmful transport and by actively suggesting environmentarianism to others.

As an environmentarian may begin by making very small changes, one can be welcomed into a social movement and be eased in to making further lifestyle changes over time, rather than being put off by the strictness of veganism or the antagonism typical of some vegans. Environmentarianism has the great advantage of making it easier for the many who cannot face the idea of never eating animal products again to live more ethically-driven lives.

It follows from all this, then, that consistent vegans should be (especially stringent) environmentarians. For the given impact they have on the total harm to animals, it does not matter if this comes from a totally vegan diet. In fact, to be fixated on dietary purity to the neglect of other spheres of one’s life – in the way that many vegans are – is to contradict a care about harms to animals. With this care given, what matters is lowering the level of harm to animals, regardless of how this harm is done.

This article was republished with permission from the Journal of Practical Ethics.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Politics + Human Rights

Feminist porn stars debunked

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships, Science + Technology

Periods and vaccines: Teaching women to listen to their bodies

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Your child might die: the right to defy doctors orders

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships