Risky business: lockout laws, sharks, and media bias

Risky business: lockout laws, sharks, and media bias

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + Leadership

BY Jack Hume The Ethics Centre 8 DEC 2016

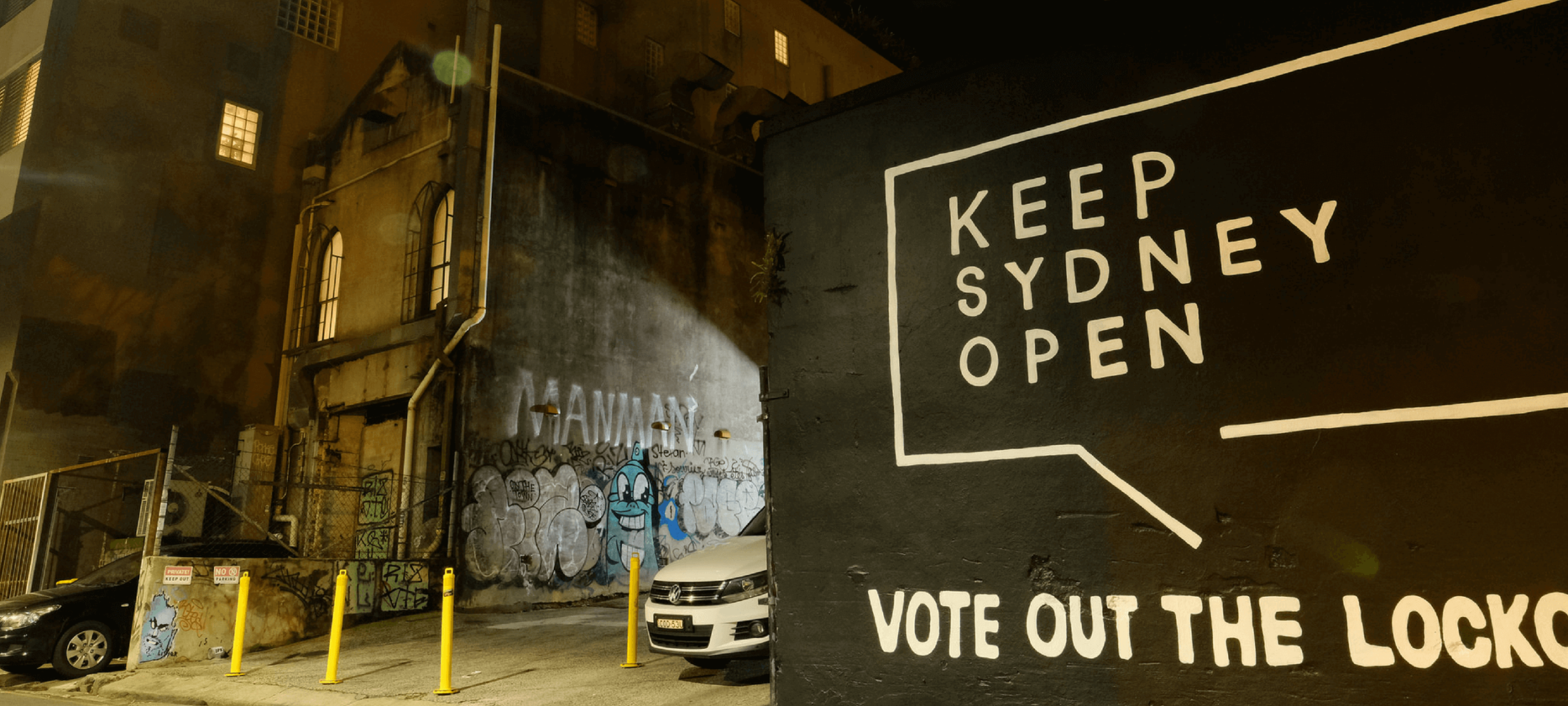

The New South Wales lockout laws were introduced in early 2014 in the wake of a great tragedy – the loss of human life to alcohol-fuelled violence.

Following the recommendations of an independent inquiry by Ian Callinan QC in 2016, the government decided to soften them. It shows that when we legislate in the wake of a tragedy, our judgement can be reactive. In the future, let’s measure our reactions against evidence.

When lockout laws were introduced in Sydney, alcohol related violence was on a downward trend. Even if people were afraid of becoming victims of violence, they were actually less likely to be attacked than in the past.

There is something to be learned from reflecting on the climate in which these laws were passed. We should be thinking about risks in terms of their likelihood, not in terms of how much we fear them. But that’s very hard, as we can see with another example – shark attacks.

People overestimate the likelihood of a shark attack in the same way they do other events they seriously fear, like terrorism and natural disasters. A study on Australian perception of sharks found that Sydneysiders believe shark attacks occur twice as often as they actually do, and fatal ones four times as often.

“Exposure to television media depicting violence and crime leads to a substantial rise in how often people believe they occur. This effect is particularly strong for vivid images.”

This isn’t surprising. Research tells us we believe things are more likely to occur if we can easily call to mind examples of when they’ve occurred. And disturbing examples are easier to recall. The process of judging the probability of an event by how easy we find it to think of examples is known as the availability heuristic.

Emotional information is easier to remember, and so the availability heuristic has an interesting relationship with news coverage. Emotional news content prompts our attention, invariably placing demands on further coverage, which we will remember more easily.

News media is highly responsive to issues its audiences are interested in, and as a result those issues get more coverage. This pulls people into a feedback loop whereby their demands for further coverage lead them to believe events are more probable than they really are.

“Passing legislation in a climate of fear is risky business and can deliver us further problems down the line.”

For example, exposure to television media depicting violence and crime leads to a substantial rise in how often people believe crimes occur. This effect is particularly strong for vivid images.

Knowing all this, we should expect people to overestimate the probability of events that provoke fear – violence, terrorism, plane crashes and natural disasters – particularly while they’re fresh in our memory. This effect is seen not just in how we speak and think about probability, but in how we act to protect ourselves, which brings us back to NSW policy.

Passing legislation in a climate of fear is risky business and can deliver us further problems down the line. Lockout laws are said to have been bad for Sydney’s culture and night-time economy. The public backlash forced the review that recommended loosening the reins of the lockout laws.

“Once news providers and their audience are responding only to one another without consideration for evidence or facts, the public’s ability to accurately judge risk has been seriously distorted.”

The point is not whether lockout laws are effective in decreasing the threat of violence (which they have been in Sydney CBD), but the conditions through which they came about. These included media coverage on disturbing and unusual events – in particular, ‘one-punch’ killings – which caused fear and demanded attention, plus a campaign to increase awareness.

When the media reports on disturbing and unusual events at the same time that campaigns are run to increase awareness for them, the basic ingredients for a feedback between news media and its audiences are met. Once news providers and their audiences are responding only to one another without consideration for evidence or facts, the public’s ability to accurately judge risk has been seriously distorted.

Shark nets are installed with the expectation of reducing the risk of shark attacks but they do this at the expense of marine life. They come as a response to the fact Australia has an above average incidence of shark attacks, which appear to be increasing. But let’s put this in perspective – the risk posed by sharks is still extremely low, accounting for two deaths in 2016 and one death in 2017.

The availability heuristic has unconscious components. Usually, people aren’t aware they’re estimating probability based on their fallible and selective memory. When people are unaware of how emotions, personal experiences and exposure to similar events can affect their judgements, they make unconsciously biased decisions.

Without appropriate consideration, people are at risk of basing important decisions on forces they aren’t consciously aware of. They may be led to support invasive or expensive regulations to protect themselves from risks that are highly unlikely. Where these regulations have undesirable side effects, like marine animal deaths, cultural damages to nightlife or the closure of businesses, this can mean real consequences for unreal problems.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Hindsight: James Hardie, 20 years on

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Has passivity contributed to the rise of corrupt lawyers?

Reports

Business + Leadership

Thought Leadership: Ethics in Procurement

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

How to spot an ototoxic leader

BY Jack Hume

Jack studied Philosophy and Psychology at the University of Sydney, completing his Bachelor of Arts in 2017 with First Class Honours. He has supported The Ethics Centre's Advice & Education team in research capacities over the last two years, contributing to their work on cognitive bias in decision making, and ethics education in financial services. In 2018, he joined the Centre full-time as a Graduate Consultant. He brings insights from contemporary political philosophy, moral psychology and skills in qualitative research to consulting projects across a variety of sectors.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Confirmation bias: ignoring the facts we don’t fancy

Confirmation bias: ignoring the facts we don’t fancy

Opinion + AnalysisHealth + WellbeingRelationships

BY John Neil The Ethics Centre 7 DEC 2016

We all like to believe we’re careful thinkers who gather and evaluate facts before making a decision. Unfortunately, we’re not.

We tend to seek information we find favourable and which supports what we already think. In short, we reach a conclusion first, then test it against evidence, rather than gather evidence first and evaluate it to make a conclusion.

This is called confirmation bias, which is a type of cognitive bias (like the bandwagon effect, or the availability heuristic) in which we tend to notice or search out information that confirms what we already believe or would like to believe. To avoid the discomfort of finding information that doesn’t support our views or ideas, we will discount or disregard evidence that’s contrary to our beliefs or preferences.

This plays out in similar ways across a range of contexts. In the sciences, theories are developed through falsifying and supporting evidence. Researchers need to recognise their own potential confirmation biases that come with holding a strong view or belief in the face of other evidence.

Confirmation bias plays out both in a range of research disciplines and our everyday decision making. When we research brands or products we tend to seek out information that reinforces our tastes and preferences. For instance, being drawn to reviews favouring brands we already like.

Confirmation bias is also at play in more significant life decisions like superannuation and other investment choices. Often, the greater the significance of a decision, the greater the likelihood that confirmation bias will be in play. If we don’t want to be left behind when we hear friends or colleagues talking about how well an investment is doing, our research will be strongly influenced by the story of our friend’s success. In doing so, we may filter out information that raises red flags and instead focus on the information validating the investment.

Our technology comes full with confirmation bias. Social media news feeds and online sources are ready made filters of information from people who think like us. Paradoxically, the tools and technologies that make information so accessible heighten the likelihood of us being drawn into information loops which reinforce what we think we know. As Warren Buffett famously remarked, “What the human being is best at doing is interpreting all new information so that their prior conclusions remain intact”.

Like several other biases, confirmation biases are an example of ‘motivated reasoning’. Motivated reasoning describes how our judgments are consciously and unconsciously influenced by what we think we know. This shapes how we think about our health, our relationships, how we decide how to vote and what we consider fair or ethical.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships

Game, set and match: 5 principles for leading and living the game of life

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Do Australia’s adoption policies act in the best interests of children?

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

How to respectfully disagree

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships, Society + Culture

Of what does the machine dream? The Wire and collectivism

BY John Neil

As Director of Education and Innovation at The Ethics Centre, John collaborates closely with a talented team of specialists and subject matter experts to shape the tools, frameworks, and programs that drive our work forward. He brings a rich and varied background as a consultant, lecturer, and researcher, with expertise spanning ethics, cultural studies, sustainability, and innovation. This multidisciplinary perspective allows him to introduce fresh, thought-provoking approaches that energise and inspire our initiatives. John has partnered with some of Australia’s largest organisations across diverse industries, to place ethics at the heart of organisational life. His work focuses on education, cultural alignment, and leadership development to foster meaningful and lasting impact.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Ask me tell me: Why women think it’s ok to lie about contraception

Ask me tell me: Why women think it’s ok to lie about contraception

Opinion + AnalysisHealth + WellbeingRelationships

BY The Ethics Centre 6 DEC 2016

‘Ask Me, Tell Me’ is a series created by you. You told us what you want to talk about by contributing your thoughts to an interactive artwork at the Festival of Dangerous Ideas.

This week: what happens to sex when people can’t trust each other? We look at the ethics and politics of sex.

Sexual ethics is prickly business. For the sake of exploring your contribution dear FODI patron, let’s assume you’re a man who has been lied to by a now pregnant woman who said she couldn’t conceive because she was using contraception.

Speaking of assumptions, it’s easy to assume our personal experiences are common, particularly big, life-changing ones like this. Experience is after all the key learning module in the school of life. But an assessment of the world based on our own experiences or one-off things we see, no matter how prominently they feature in our lives, is not exactly objective (although it’s a common cognitive bias we all can slip into).

Seeing ‘women’ as a group who lie to get pregnant isn’t a fair assessment of all women. Like every other group in society that shares some sort of common ground, women don’t think the same way or collectively decide what’s ethical and what’s not.

Also, there’s not much evidence to support this being a common practice of women other than a poll by That’s Life! magazine.

Nevertheless, none of this is to deny what we’re assuming has happened to you. It’s just pointing out it’s unlikely to be a prevalent phenomenon.

…men could choose to have no legal rights or responsibilities to a child as a way of correcting the alleged power imbalance in which men are held accountable as parents even if they would have preferred a pregnancy be terminated.

Whether or not it’s common for women to fib about using contraception to get pregnant doesn’t change the extent to which you must feel betrayed, trapped, angry and lied to. You’re facing the prospect of a lifelong commitment you believed wasn’t on the cards. Can anything be done about it?

There are a couple of ways to prevent others from finding themselves in the same situation. A Swedish group recently campaigned to give men the right to ‘legally abort’ from children. Under the proposal, men could choose to have no legal rights or responsibilities to a child as a way of correcting an alleged power imbalance that holds men accountable as dads even if they never wanted to be one.

‘Legal abortions’ don’t seem to actually be legal anywhere in the world but the argument in favour of them is that they level the playing field. Many of course would see women as the ones bearing more of the challenges of unwanted pregnancies than men, given they’re the ones who have to carry and give birth to the child.

Nevertheless, ‘legal abortions’ is an idea several thinkers, often women, have been discussing for a while.

Sex is risky – not only because of the possibility of children or infection – but because it leaves us physically and emotionally vulnerable.

An easier option would be for men to take contraception into their own hands. Condoms have been available for a long time. They’re 98% effective, prevent sexually transmitted infections and tend to be cheaper than female methods. And in years to come, a male contraceptive pill may well be available – a promising trial study of a male pill was abandoned due to side effects.

However, trust has become an issue here as well, with some women not having faith in men to take care of contraception. The Guardian columnist Barbara Ellen describes this as “the relentless howl of distrust between the sexes, echoing down the years”. Perhaps the best solution is one in which both men and women use contraception.

In many ways, this is a neat solution but can we really use technology as a substitute for sexual trust? Or, if men and women are doomed to distrust one another as Ellen suggests, what are the consequences of sex without trust? We trust sexual partners to use protection and contraception. We trust them to be concerned for our pleasure as well as theirs, to recognise our boundaries and seek our consent before doing anything to us or demanding anything from us, to respect our privacy and so on. At the heart of all of this is the understanding that sex is risky – not only because of the possibility of babies and infection – but because it leaves us physically and emotionally vulnerable.

Philosopher LA Paul describes becoming a parent as a ‘transformative experience’ – an experience that changes who we are so fundamentally it’s impossible to know whether the person we will become will regret our decision or not.

None of this gives you, FODI punter, much to go on with. You’ve been lied to, you’re facing long term consequences as a result and now you have to choose what kind of parent you want to be. And because you were lied to you’ve been put in this position unjustly and against your will, which is wrong by almost any measure.

Unfortunately, you still have to decide what to do. Philosopher LA Paul describes becoming a parent as a ‘transformative experience’ – an experience that changes who we are so fundamentally it’s impossible to know whether the person we will become will regret our decision or not. By definition, we can’t know what the right thing to do is.

Paul thinks this is true for all parents, not just those facing unwanted pregnancies. Even though there’s not much guidance on what you should do in this situation, it might be reassuring to know every potential parent is facing the same impossible decision. In the end, Paul suggests the best way to make this decision is to base it on what we want to discover, not what we think we’d enjoy.

And if you’re still stuck, you can always contact Ethi-call – The Ethics Centre’s free helpline – where you can speak with one of our counsellors to help make a decision aligned with your own values, principles and conscience.

Follow The Ethics Centre on Twitter, Facebook and Instagram.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

The etiquette of gift giving

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Easter and the humility revolution

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture, Relationships

Discomfort isn’t dangerous, but avoiding it could be

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships, Science + Technology

Are we ready for the world to come?

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Ethics Explainer: Hedonism

Hedonism is a philosophy that regards pleasure and happiness as the most beneficial outcome of an action. More pleasure and less pain is ethical. More pain and less pleasure is not.

What is hedonism?

Hedonism is closely associated with utilitarianism. Where utilitarianism says ethical actions are ones that maximise the overall good of a society, hedonism takes it a step further by defining ‘good’ as pleasure.

There are different perspectives on what pleasure and pain really mean. For Epicurus, the ancient Greek philosopher, pleasure was the absence of pain. Though his name has become synonymous with indulgence – “Epicurean holidays”, a food app called “Epicurious” – he advocated finding pleasure in a simple life with a bland diet.

If we live a rich, complex lifestyle we risk suffering more when it ends. Best not to love them to begin with, he suggests.

John Stuart Mill believed in a hierarchy of pleasures. Although sensory pleasures might be the most intense, it was fitting for higher order beings – like humans – to enjoy higher order pleasures – like art. “It is better to be Socrates dissatisfied than a pig satisfied”, he said. (With evidence to suggest pigs can orgasm for up to fifteen minutes, Mill’s account feels a little incomplete).

Most people will agree pleasure and pain are important for determining the value of something. That’s not enough to make you a hedonist. What makes hedonism unique is the claim only pleasure and pain matter. That’s where people tend to be more hesitant.

The experience machine

The philosopher Robert Nozick wanted people to feel the pinch of measuring life only based on pain and pleasure. He developed a thought experiment called the experience machine.

Imagine a machine that can plug into your brain and simulate the most pleasurable life you could imagine. It would respond to your specific desires – you could be a rock star, philosopher or space cowboy depending on what was most pleasurable. But if you plugged in, you could never unplug. Plus, although you’d feel as though you were experiencing amazing things, you’d be floating in a vat, feeding through a tube.

Nozick thought most people would choose not to plug into the machine – proving there was more to life than pleasure and pain. But Nozick’s argument depends on people’s lives being of a certain quality. It’s easier to value hard work and authenticity if you’re confident your life will be pretty pleasurable. For those living in constant fear, pain, or misery, perhaps the authenticity of their experience matters less than some simple moments of bliss.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Rationing life: COVID-19 triage and end of life care

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

There’s more than lives at stake in managing this pandemic

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Five stories to read to your kids this Christmas

Opinion + Analysis

Climate + Environment, Health + Wellbeing

How should vegans live?

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

The road back to the rust belt

The road back to the rust belt

Opinion + AnalysisHealth + Wellbeing

BY Dennis Glover The Ethics Centre 24 NOV 2016

In The Road to Wigan Pier, George Orwell observed that it was far easier for a Bishop to relate to a tramp than to a solid member of the working class.

The poverty of the former was wholly obvious, and one could easily enter into his world by tramping with him and offering him a bowl of soup, but entering into the homes and culture of the latter was almost impossible.

In Australia today we might put it differently: it’s often easier for an educated ‘progressive’ to relate to a refugee or an Indigenous person or an LGBTI person than to someone in a Housing Commission suburb.

This is understandable and even laudable. After all, it’s the mark of a civilised community to treat others – even those least like us – with respect and to prioritise those whose needs are the most obvious and urgent. This way of thinking has become increasingly central to our liberal culture.

For example, I have before me a scholarship guide (really an advertising supplement) for some of the nation’s wealthiest private schools. In it you will find scholarships specifically targeted at diverse categories of people whose moral call on us is obvious, but none targeted at children from the old factory suburbs with high unemployment. The closest we get are vague references to help for ‘the children of families who require financial assistance’, which could mean just about anything.

Without noticing it, and often with the very best of intentions, we have stopped thinking and talking about the working class. When I recently wrote a book about one of our most neglected former Housing Commission suburbs, I was surprised at the consternation – even offense – it generated, particularly on the Left. Has it become so unusual to discuss such things? The shock of recent overseas events for such discussion has made this blindspot obvious and acceptable.

Without noticing it, and often with the very best of intentions, we have stopped thinking and talking about the working class.

This seems to me somewhat extraordinary given there are now numerous suburbs in Australia where the unemployment rate has been at 20, 21, 22 and even 33.6 percent for a decade or more. That we have been able to almost completely ignore this level of economic injustice for so long tells us something about how much our way of thinking has changed, amounting almost to a moral blindness. The coming closure of car factories and coal fired power plants across Victoria and South Australia will only make this worse, creating our own versions of America’s rust belt.

These days, it seems, one can be a self-identifying ‘progressive’ without giving much thought at all to what’s happening to the workers and the unemployed. The implication is they represent our economic past, and are therefore not wholly worthy of serious thought. Scratch a socially-progressive economist and you may well find someone who thinks saving manufacturing jobs to be a doubtful investment – perhaps it’s better for the general good such people and places be allowed to quietly disappear. The problem, as Britain and America shows, is they don’t disappear. They collapse in on themselves and get angry.

The way the culture wars have poisoned our political debates means this sort of thing isn’t easy to say without opening oneself up to some charge of illiberalism, so let me be clear: we should treat refugees more humanely, keep aggressively closing the gap between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians, and keep expanding the circle of rights to include new categories of difference, but we must also talk about what’s happening to the old working class. We can do all these things simultaneously but at the moment we are not.

Every day this ignoring of the old working class becomes a bigger problem for our democracy. As Brexit and Donald Trump’s victory demonstrate, in an economy that is restructuring, populists will eagerly pounce and turn the sense of neglect felt by ‘the forgotten’ into envy and resentment. The resuscitation of Pauline Hanson’s One Nation Party shows it may be happening here too. We need to advance on a broader front.

If you want to know why Australia is currently having a debate about Section 18C of the Race Discrimination Act, it’s partly because those who seek to exploit this envy and resentment need to remove laws which restrain the full expression of these negative emotions. The attacks on 18C and the fate of the old working class are ultimately connected.

Some argue the Left’s response must be to abandon what is commonly dismissed as ‘the rights agenda’ and take a more populist stand. This is wrong. The Left, which has traditionally been both liberal and social-democratic, shouldn’t downplay its liberalism but, rather, give new life to the social-democratic half of its equation, which it has been neglecting for too long. This doesn’t mean looking backwards. It means thinking through how our older industrial communities can be revived to take advantage of economic restructuring – instead of treating their interests as an irritating afterthought.

What form this modernised social-democracy will take is as yet to be determined but one thing is clear: it has to start with a moral effort to know what’s going on in the lives of people in the places where we stopped looking a generation ago, and it needs to be followed by a public policy effort that matches the scale of the problem.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Politics + Human Rights

Constructing an ethical healthcare system

Explainer

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Values

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

People with dementia need to be heard – not bound and drugged

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Living well or comfortably waiting to die?

BY Dennis Glover

Dennis Glover is a fellow of the Per Capita think tank and the author of An Economy is Not a Society: Winners and Losers in the New Australia

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Despite codes of conduct, unethical behaviour happens: why bother?

Despite codes of conduct, unethical behaviour happens: why bother?

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + Leadership

BY Ed St John The Ethics Centre 1 NOV 2016

Like stationery cupboards and monthly accounts, codes of conduct are one of those necessities of life in any business.

Whether you’re a small or medium enterprise or a large and complex organisation spread across multiple locations, a code of conduct sets the benchmark of expectation for the behaviour of your workforce.

Codes of conduct take many forms. Some are exceptionally long – a phone book of Policies and Procedures which attempt to anticipate every possible scenario and explicitly forbid the worst category of behaviour from the least reliable employee. Others are short and elegant, placing maximum trust in the maturity and honesty of the workforce.

Some are designed as a trap – if you break any of these rules, we’ll have an excuse to terminate your employment. Others are designed as an invitation – do the right thing by us, and we’ll do the right thing by you.

Some codes are complex by necessity, reflecting the strict compliance regimes of highly regulated industries such as financial services or medicine. Others are loose and relaxed, reflecting the new-age approaches to work pioneered in Silicon Valley over the past decade. Work when and where you like, do no harm, enjoy the free lunch.

In a world of extremes, we’ve all seen attempts at over-regulation (the five-page working from home checklist, for example) and we’ve all drooled over the progressive policies of companies such as Netflix, which offers its employees unlimited leave, amongst other things. Their five word expense policy (“act in Netflix’s best interests”) is the gold standard for a new type of policy that treats employees like adults.

In designing a code – no matter what you call it and what it looks like – it’s worth remembering two important things. First: a code will only work if it is founded in a sound statement of the organisation’s purpose, values and principles (what we call the Ethical Framework). Second: no code can replace active hands-on management of your culture and your people.

An ethical framework expresses fundamental principles that that help guide us through terrain where no rule is in place or where matters are genuinely unclear. This is a critical foundation document for any organisation – it is, quite literally, what we believe in and what standards we uphold. It must be consistently embraced by every member of the organisation in order to be effective.

An ethical framework demands something more than mere compliance. It asks employees to exercise judgement and accept personal responsibility for the decisions they make.

A well drafted code of conduct will be consistent with the framework, but it will provide much more specific guidance. For example, where your ethical framework espouses values such as transparency and accountability, the code of conduct might explicitly spell out the conflict of interest policy or the rules surrounding gifts and benefits.

Ethical frameworks and codes of conduct are not magic bullets to solve an organisation’s problems. The fact a company has created these documents will not guarantee that all employees will do the right thing every time. But approached with the proper degree of care and sophistication, the very process of developing these codes can have a profoundly positive effect on the culture of an enterprise.

In establishing the things you believe in and identifying the behaviours you wish to encourage, you establish a framework for a great corporate culture – one based on respect, trust, collaboration and accountability. And who wouldn’t want that?

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Health + Wellbeing

Is your workplace turning into a cult?

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Risky business: lockout laws, sharks, and media bias

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships

There are ethical ways to live with the thrill of gambling

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Political aggression worsens during hung parliaments

BY Ed St John

Ed joined The Ethics Centre as Executive General Manager in 2014 after a career in the interconnected worlds of marketing, communications, entertainment and live events. His diverse roles include editor of Rolling Stone Magazine, TV producer, talent consultant to The Voice and X Factor, Twitter executive, CEO of Warner Music, Managing Director of BMG Music, Chairman of ARIA and CEO of Renovating For Profit. Throughout his career, Ed has experienced a range of ethical dilemmas and is cherishing his role where enabling good decision making is his core work, helping original thinking and lively public debate flourish.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Melbourne Cup: The Ethical Form Guide

Melbourne Cup: The Ethical Form Guide

Opinion + AnalysisClimate + EnvironmentHealth + WellbeingSociety + Culture

BY The Ethics Centre 1 NOV 2016

The nation stops – and turns a blind eye.

The Melbourne Cup is the race that ‘convenes’ rather than ‘stops’ the nation. It’s a classic example of a moment when the abstraction that is the nation – large, sprawling, messy and diverse – is made temporarily and symbolically concrete. This is an illusion. But perhaps a necessary one.

The mega media sport spectacle is highly serviceable to the fantasy of the united nation because it is popular culture played out in real time. Sport is implicated in the idea of a singular Australian identity because it is apparently open and meritocratic, and also has operated historically as a vehicle for the projection of ‘Australianness’.

The Melbourne Cup represents the pros and cons of contemporary sport and society. It is devoted to pleasure as an interruption of the daily work routine that consumes more and more of our time. It is carnivalesque – fleetingly turning the world upside down.

But it is characterised by the range of excess demanded by consumer capitalism – risky financial expenditure, alcohol consumption and repressive co-optation. All of this activity is conducted using the body of the horse that is celebrated one minute and whipped the next, highly prized for sporting and breeding performance in some cases and turned into abattoir fodder in others.

National sporting spectacles are here to stay. The ‘people’, the state and the commercial complex demand them, but they should not be excuses for rampant collective self-delusion.

– David Rowe, Professor of Cultural Research at Western Sydney University.

If you loved horses, you wouldn’t treat them as commodities

We’re often told those involved in the horse racing industry truly love horses and treat them with the utmost respect. I have no doubt they believe that to be true, but their actions don’t support these claims.

If those working with horses truly loved them, they would spend time and money re-homing and appropriately retiring racehorses at the end of their careers. Instead, the evidence suggests racehorses are only loved when they have the potential to make money. When they’re injured or no longer able to race, they’re often sent off to the knackery without a second’s thought.

The racing industry pushes horses beyond their natural limits. This results in short careers and extensive injuries, such as those suffered by Admiral Rakti last year. Since Admiral Rakti’s death, 127 horses have died on Australian race tracks.

The ultimate image for this exploitative approach to racing is the whip, which desperately needs to be banned. In doing so, we would see horses performing at the peak of their natural ability rather than desperately running due to fear and pain.

– Elio Celotto, Campaign Director at the Coalition for the Protection of Racehorses.

The risks of horse racing are imposed on unwilling participants

Horse racing differs ethically from other sports. In other sports, it is the participant who freely decides to accept the risks. In horse racing, the risks are relatively low for the riders and extremely high for the animals.

It is not unethical to accept the risks of a given sport. Nor, in my view, is it always unethical to take the life of animals. The question is whether the costs of horse racing are reasonable, or whether they are unacceptably high.

Most Australians today would have ethical objections to entertainments such as bullfighting or dog fighting, or the use of non-domestic animals in circus acts. The number of horses slaughtered annually as a result of the racing industry far exceeds the number of animal deaths from most of these other entertainments.

The costs of the racing industry are unacceptably high. The situation is unlikely to improve as long as horse racing in Australia remains so closely tied to the enormous economic interests of the gambling industry.

– Ben Myers, Lecturer in Systematic Theology at United Theological College.

The Melbourne Cup sweep is harmless fun, but not in the classroom

The effects of gambling are an oft-discussed topic among my colleagues, but in the past week the discussion has been triggered by an all-staff email about the office’s annual Melbourne Cup Sweep. One staff member felt it was totally inappropriate for an organisation operating in mental health and wellbeing to be promoting in any way a day of socially acceptable statewide gambling.

I actually disagree, although not strongly. A sweep is a one-off, fixed price competition, not much different from a raffle. It’s in no way addictive in the way that poker machines and online betting can be.

The normalisation of gambling is certainly insidious. There is some evidence that the younger a person is when they have their first betting win, the more likely they are to develop problems down the track. So a sweep in a primary school does sound icky to me.

– Heather Grindley, Public Interest Manager at the Australian Psychological Society.

The spectacle is lost in a “feeding frenzy” of gambling

The Melbourne Cup is a genuine Australian icon. However, it’s now also a commodified hub for a gambling feeding frenzy. This is a tough time of year for people who are trying to restrain their gambling.

Effective regulation can undoubtedly reduce the harms associated with gambling. Cup Day should be a reminder that commercialised gambling corrupts sport and induces misery for many, including those who never gamble. Decent regulation might reduce super-profits but it would certainly help make Australia’s unique sporting and social environment safer, more fun and lot more enjoyable.

– Charles Livingstone, Senior Lecturer in Public Health and Preventive Medicine at Monash University.

The Melbourne Cup pits debauchery against dignity

As I write, many will be gathered in offices, pubs and racecourses around the country dressed to the nines. Fascinators, frocks, loud ties and sharp suits are the order of the day for the “world’s richest race”.

And yet by the end of it all, many punters will be staggeringly drunk – their state highlighted by its juxtaposition to their glamorous attire. Every year, tabloids gleefully post pictures of women in various stages of undress – simultaneously glorifying and shaming the debauchery that accompanies a race some revellers will likely miss, having already passed out.

Ultimately the Melbourne Cup is full of ethical polarities. It follows the highs and lows of the race itself. Fine champagne is popped in celebration as punters pass out from one too many drinks, horses are glorified as they are exploited, and once-off punters dress up and participate in the same gambling industry that destroys so many lives.

Racing Victoria were unavailable for comment but directed readers to their position on equine welfare.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture

Does ‘The Traitors’ prove we’re all secretly selfish, evil people?

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Women must uphold the right to defy their doctor’s orders

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Moral fatigue and decision-making

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing

4 questions for an ethicist

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

The Ethics Centre Nominated for a UNAA Media Peace Award

The Ethics Centre Nominated for a UNAA Media Peace Award

Opinion + AnalysisSociety + Culture

BY The Ethics Centre 30 OCT 2016

The Ethics Centre is proud to announce that we’re a finalist in this year’s United Nations Association of Australia Media Peace Awards.

We’ve been nominated in the “Promotion of Social Cohesion” category for our IQ2 Debate: Racism is Destroying the Australian Dream.

The UNAA Media Peace Awards – which were handed out for the first time in 1979 – seek to promote understanding about humanitarian and social justice issues by recognising those in the media whose contributions stimulate public awareness and understanding.

Past winners include Andrew Denton, Paul McGeough, Michael Gordon, Jenny Brockie, Zoe Daniel and Waleed Aly. The United Nations Association of Australia is one of 100 associations around the world which promote the ideals and work of the UN in local communities.

More than 70 journalists, producers, photographers and film makers are among the finalists in 13 categories. Media reporting on the plight of asylum seekers and the rights and treatment of Indigenous Australians features heavily in the list of finalists for this year. See the full list here.

Thanks to all our audience members and supporters who continue to make IQ2 possible for us. We couldn’t do it without you.

The winners of the awards will be announced in Melbourne on 24 October, UN Day. In the meantime, watch our entry – Racism is Destroying the Australian Dream.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

Meet Eleanor, our new philosopher in residence

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

What money and power makes you do: The craven morality of The White Lotus

LISTEN

Relationships, Society + Culture

Little Bad Thing

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

Violence and technology: a shared fate

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Ethics Explainer: The Harm Principle

Ethics Explainer: The Harm Principle

ExplainerPolitics + Human RightsRelationships

BY The Ethics Centre 27 OCT 2016

The harm principle says people should be free to act however they wish unless their actions cause harm to somebody else.

The principle is a central tenet of the political philosophy known as liberalism and was first proposed by English philosopher John Stuart Mill.

The harm principle is not designed to guide the actions of individuals but to restrict the scope of criminal law and government restrictions of personal liberty.

For Mill – and the many politicians, philosophers and legal theorists who have agreed with him – social disapproval or dislike (“mere offence”) for a person’s actions isn’t enough to justify intervention by government unless they actually harm or pose a significant threat to someone.

The phrase “Your freedom to swing your fist ends where my nose begins” captures the general sentiment of the principle, which is why it’s usually linked to the idea of “negative rights”. These are demands someone not do something to you. For example, we have a negative right to not be assaulted.

On the other hand, “positive rights” demand that others do certain things for us, like provide healthcare or treat us with basic respect. For this reason, the principle is often used in political debates to discuss the limitations of state power.

There’s no issue with actions that are harmful to the individual themselves. If you want to smoke, drink, or use drugs to excess, you should be free to do so. But if you get behind the wheel of a car while under the influence, pass second-hand smoke onto other people, or become violent on certain drugs, then there’s good reason for the government to get involved.

Attempting to define harm

The sticking point comes in trying to define what counts as harmful. Although it might seem obvious, it’s actually not that easy. For example, if you benefit by winning a promotion at work while other applicants lose out, does this count as being harmful to them?

Mill would argue no. He defines harms as wrongful setbacks to interests to which people have rights. He would argue you wouldn’t be harming anyone by winning a promotion because although their interests are set back, no particular person has a right to a promotion. If it’s earned on merit, then it’s fair. “May the best person win”, so to say.

A more difficult category concerns harmful speech. For Mill, you do not have the right to incite violence – this is obviously harmful as it physically hurts and injures. However, he says you do have the right to offend other people – having your feelings hurt doesn’t count as harm.

Recent debates have questioned this and claim that certain kinds of speech can be as damaging psychologically as a physical attack – either because they’re personally insulting or because they entrench established power dynamics and oppress minorities.

Importantly, Mill believed the harm principle only applied to people who are able to exercise their freedom responsibly. For instance, paternalism over children was acceptable since children are not fully capable of responsibly exercising freedom, but paternalism over fully autonomous adults was not.

Unfortunately, he also thought these measures were appropriate to use against “barbarians”, by which he meant non-Europeans in British colonies like India.

This highlights an important point about the harm principle: the basis for determining who is worthy or capable of exercising their freedom can be subject to personal, cultural or political bias. When making decisions about rights and responsibilities, we should be ever careful about the potential biases that inform who or what we apply them to.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

The new normal: The ethical equivalence of cisgender and transgender identities

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships

The twin foundations of leadership

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

Power without restraint: juvenile justice in the Northern Territory

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships

The role of the ethical leader in an accelerating world

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Workplace ethics frameworks

A placard used to hang in the office of Milton Hershey, founder of the revolutionary chocolate company carrying a simple motto: “Business is a matter of human service”.

Hershey shaped his organisation around a progressive, generous employment model. In a time when corporate leaders were seen as villains and Theodore Roosevelt won the White House election on the promise of breaking up monopolies and regulating business more firmly, Hershey’s was seen by many as a model of responsible, prosocial business.

At the same time, Cadbury in the UK were making similar moves. Each company built a fully-serviced town for their employees, offered children an education, taking responsibility for supply chains, and gave the public tours of the facilities.

In Connect: How Companies Succeed by Engaging Radically with Society, John Browne suggests the companies “identified the potency of a corporate vision delivered through employees” – a message which is “as true today as it was in 1900”. Who said chocolate wasn’t good for us?

Today, we’d recognise elements of their activity – firm social purpose and activity driven by value rather than profit – as elements of an ethics framework, a central, defining expression of what a company believes in and seeks to uphold.

Ethics frameworks consist of three things: a purpose statement, values and principles.

They aren’t documents to be filed away or popped in a corner of the company website, never to be read. Writing a document about who we are and what we stand for means nothing unless those statements are lived and breathed in the company operation.

Like the confectioners of the early 20th century, the very best companies bring cohesion to their business decisions by showing staff the meaning of their values, purpose and principles. They work with them to show how these core ideals guide everyday business decision making.

Purpose statements can be long or short. They usually don’t focus on products or services but how, as Hershey recognised, your company is satisfying a community need.

Values and principles enable employees to distinguish between good and bad decisions. They help to frame business activity to ensure it stays true to its purpose and contract with society.

Together these form your ethics framework: the bedrock or ‘DNA’ of your organisation. A good framework will be:

- Practical – able to be applied in practice and with consistency.

- Authentic – it will ‘ring true’.

- Stable – will not change much (in its essence) over the long term.

- Understandable – by all of those required to apply it in practice.

Having an ethics framework isn’t designed to maximise profits. It’s designed to protect and improve the relationship between business and society – but it does often benefit the business as a commercial enterprise as well. By motivating employees and demonstrating the value and purpose of the business to them, they serve as ambassadors for your organisation.

What’s more, trusted organisations are more likely to survive the instances when they fall foul of public opinion. In 1909, Cadbury – until then widely respected – were accused of being involved in slave labour in Portugal. Despite the public outcry, Cadbury were able to survive the incident and restore their reputation because of the goodwill they’d earned through authentically living their ethics framework.

Although purpose statements, corporate values and organisational principles aren’t a guarantee of perfect ethical conduct, they are a crucial ingredient in building a culture in which bad behaviour is discouraged and dis-incentivised – and a flag of goodwill to stakeholders that your organisation is looking to serve humanity and not just turn a quick buck.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

The role of ethics in commercial and professional relationships

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Business + Leadership

Teachers, moral injury and a cry for fierce compassion

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Health + Wellbeing

Navigating a workforce through stressful times

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Science + Technology