Is it ok to use data for good?

Is it ok to use data for good?

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + LeadershipScience + Technology

BY Adam Piovarchy The Ethics Centre 7 MAY 2018

You are nudged when your power bill says most people in your neighbourhood pay on time. When your traffic fine spells out exactly how the speed limits are set, you are nudged again.

And, if you strap on a Fitbit or set your watch forward by five minutes so you don’t miss your morning bus, you are nudging yourself.

“Nudging” is what people, businesses, and governments do to encourage us to make choices that are in our own best interests. It is the application of behavioural science, political theory and economics and often involves redesigning the communications and systems around us to take into account human biases and motivations – so that doing the “right thing” occurs by default.

The UK, for example, is considering encouraging organ donation by changing its system of consent to an “opt out”. This means when people die, their organs could be available for harvest, unless they have explicitly refused permission.

Governments around the world are using their own “nudge units” to improve the effectiveness of programs, without having to resort to a “carrot and stick” approach of expensive incentives or heavier penalties. Successes include raising tax collection, reducing speeding, cutting hospital waiting times, and maintaining children’s motivation at school.

Despite the wins, critics ask if manipulating people’s behaviour in this way is unethical. Answering this question depends on the definition of nudging, who is doing it, if you agree with their perception of the “right thing” and whether it is a benevolent intervention.

Harvard law professor Cass Sunstein (who co-wrote the influential book Nudge with Nobel prize winner and economist Professor Richard Thaler) lays out the arguments in a paper about misconceptions.

Sunstein writes in the abstract:

“Some people believe that nudges are an insult to human agency; that nudges are based on excessive trust in government; that nudges are covert; that nudges are manipulative; that nudges exploit behavioural biases; that nudges depend on a belief that human beings are irrational; and that nudges work only at the margins and cannot accomplish much.

These are misconceptions. Nudges always respect, and often promote, human agency; because nudges insist on preserving freedom of choice, they do not put excessive trust in government; nudges are generally transparent rather than covert or forms of manipulation; many nudges are educative, and even when they are not, they tend to make life simpler and more navigable; and some nudges have quite large impacts.”

However, not all of those using the psychology of nudging have Sunstein’s high principles.

Thaler, one of the founders of behavioural economics, has “called out” some organisations that have not taken to heart his “nudge for good” motto. In one article, he highlights The Times newspaper free subscription, which required 15 days notice and a phone call to Britain in business hours to cancel an automatic transfer to a paid subscription.

“…that deal qualifies as a nudge that violates all three of my guiding principles: The offer was misleading, not transparent; opting out was cumbersome; and the entire package did not seem to be in the best interest of a potential subscriber, as opposed to the publisher”, wrote Thaler in The New York Times in 2015.

“Nudging for evil”, as he calls it, may involve retailers requiring buyers to opt out of paying for insurance they don’t need or supermarkets putting lollies at toddler eye height.

Thaler and Sunstein’s book inspired the British Government to set up a “nudge unit” in 2010. A social purpose company, the Behavioural Insights Team (BIT), was spun out of that unit and is now is working internationally, mostly in the public sector. In Australia, it is working with the State Governments of Victoria, New South Wales, Western Australia, Tasmania, and South Australia. There is also an office in Wellington, New Zealand.

BIT is jointly owned by the UK Government, Nesta (the innovation charity), and its employees.

Projects in Australia include:

Increasing flexible working: Changing the default core working hours in online calendars to encourage people to arrive at work outside peak hours. With other measures, this raised flexible working in a NSW government department by seven percentage points.

Reducing domestic violence: Simplifying court forms and sending SMS reminders to defendants to increase court attendance rates.

Supporting the ethical development of teenagers: Partnering with the Vincent Fairfax Foundation to design and deliver a program of work that will encourage better online behaviour in young people.

Senior advisor in the Sydney BIT office, Edward Bradon, says there are a number of ethical tests that projects have to pass before BIT agrees to work on them.

“The first question we ask is, is this thing we are trying to nudge in a person’s own long term interests? We try to make sure it always is. We work exclusively on social impact questions.”

Braden says there have been “a dozen” situations where the benefit has been unclear and BIT has “shied away” from accepting the project.

BIT also has an external ethics advisor and publishes regular reports on the results of its research trials. While it has done some work in the corporate and NGO (non-government organisation) sectors, the majority of BIT’s work is in partnership with governments.

Braden says that nudges do not have to be covert to be effective and that education alone is not enough to get people to do the right thing. Even expert ethicists will still make the wrong choices.

Research into the library habits of ethics professors shows they are just as likely to fail to return a book as professors from other disciplines. “It is sort of depressing in one sense”, Braden says.

If you want to hear more behavioural insights please join the Ethics Alliance events in either Brisbane, Sydney or Melbourne. Alliance members’ registrations are free.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

6 Myths about diversity for employers to watch

Reports

Business + Leadership

Productivity and Ethics

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Health + Wellbeing

Feeling rules: Emotional scripts in the workplace

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Power play: How the big guys are making you wait for your money

BY Adam Piovarchy

Adam Piovarchy is a PhD candidate in Moral Psychology and Philosophy at the University of Sydney.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Power play: How the big guys are making you wait for your money

Power play: How the big guys are making you wait for your money

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + Leadership

BY The Ethics Centre 3 MAY 2018

The CEO was brutally honest in revealing how his multinational company uses its power to delay payment to its small suppliers. Unless there are laws to make them pay up earlier, small companies are forced to wait four months for their money, he said.

The business leader was explaining the policy of his overseas head office to Kate Carnell, the Australian Small Business and Family Enterprise Ombudsman, during her inquiry into late payments last year.

“I must admit I was just horrified”, says Carnell, who says a 30 day wait is acceptable business practise.

The CEO of the Australian arm of the multinational company said payment times were pushed out to 120 days. Says Carnell: “One guy [attending the inquiry] laughed and said, ‘You should consider yourself lucky, we have a 365 day payment contract in one country I know about’.”

“They said, ‘If there is nothing that makes us pay shorter, then we will pay longer. That is just the way we operate’.”

Carnell’s Inquiry into Payment Times and Practices uncovered a widespread exercise where big organisations are using small to medium sized suppliers as a cheap form of finance. By paying invoices months after products and services are delivered, large companies can improve the efficiency of their own working capital but, in doing so, starve their vulnerable small business operators of cash.

About half of the small to medium sized businesses surveyed by the inquiry say around 40 percent of invoices were paid late. According to Carnell, 90 percent of small businesses go broke because of cash flow issues and many try to tide themselves over with credit card debt and overdrafts.

Australia had the dubious honour of being the worst performer in global research on late payments by MarketInvoice in 2015, with settlement taking place an average 26.4 days after it was due.

Lending you the money they owe you

In a further development, interest bearing loans are being offered to suppliers who are waiting to get paid. Carnell has named Mars, Kellogg’s and Fonterra as three large companies offering this kind of supply chain finance.

These loans effectively levy a discount (the interest paid) on suppliers who cannot afford contractual waits of 120 days or more. “It’s pretty close to extortion really”, Carnell told the Sydney Morning Herald last year.

Another practise is to demand a discount from suppliers who want to be paid earlier than the contracted period – even though that period may be outside what is regarded as acceptable.

“There are two ways to do it. One is to require a discount, the other is to lend you the money at an interest – both of them are unacceptable”, says Carnell.

“You’ve got what is the essence of what could be regarded bullying, it is certainly using market power in an oppressive manner.”

Salt’s call for ‘same day pay’

Social commentator Bernard Salt recently called for “same day pay” in a column in The Australian newspaper, arguing that companies should not be buying products and services if they cannot pay for them straight away.

“There are 1.5 million small businesses in Australia. If you add in their partners, and staff and kids, then you are probably looking at four to five million people in Australia that are affected by timelines or otherwise of small business payments”, he says.

“The best thing you can do for small business is to pay promptly, on the day, same day pay. If you can’t pay for it, don’t buy the good or service.

“Refusing to pay in a timely and reasonable and fair manner is the equivalent of theft. I just cannot understand where people believe it is good or smart business practise. People might think it is smart, I think it is smarmy. If you incur a debt, you pay it and pay it promptly.”

Salt says he sees no reason why the flow of money is restricted to business hours, five days a week, when the rest of the world is operating 24/7.

“We should expect money to flow at the speed of data.”

Carnell says she is not demanding immediate payment … for now. “At some stage in the future, we think that is the way it should be. Right now, 30 days or less is reasonable”, she says.

Voluntary codes don’t work

To encourage best practise, Carnell’s office has set up the voluntary Small Business Ombudsman’s National Transparency Register. So far, around 21 organisations have agreed to report on their progress on paying promptly.

“It is a start, but it is a drop in the ocean really”, admits Carnell.

The Business Council of Australia responded to the inquiry by introducing its own voluntary Australian Supplier Payment Code, which commits signatories to 30 day payment times to small businesses and has around 77 signatories, but it has no requirement that companies report.

The NSW Small Business Commissioner, Robyn Hobbs, recently told ABC Radio that she does not think the BCA code goes far enough. “These things should be mandatory”, she said.

Carnell says her approach is to try a voluntary approach first, but admits she has little faith it will work.

“We looked around the world … and we hadn’t found a situation where a voluntary code had worked to create systemic change. The problem with voluntary codes is that the good corporate citizens sign them.”

People who think their own cash flow is more important than the economy won’t sign, she says.

“We would love a voluntary code to work because it would show that, as a nation, we do take good business practise, ethical behaviour, really seriously and we can make these things work without legislation. We will review it in 12 months and we would expect, if it had not been successful, that a Government would legislate.”

Governments set a standard

In the UK, the Government has introduced a voluntary Prompt Payment Code, working towards 30 day payment, and there is legislation requiring large businesses to publish details publicly of their actual payment times.

Governments can provide a good example to the commercial sector. A UK Central Government Prompt Payment policy seeks to pay 80 per cent of undisputed and valid invoices within five days.

The European Union has a Late Payment Directive setting a maximum payment time of 60 days, or 30 days for government, with an interest penalty, and ability to claim compensation and recovery costs. US government has QuickPay to reduce government payment times from 30 days to 15 days.

In Australia, Federal Government agencies have committed to paying small operators in 15 business days by mid 2019.

Some individual companies have also taken up the challenge since the inquiry, which reported a year ago. Since the inquiry, Mars has moved from 120 day payment terms to 30 days for small businesses. “That is a big step”, says Carnell.

Telstra has also “made a big effort”, reducing payment times from 45 days or longer down to 30 days or fewer for all its 7366 small business suppliers. The telco spends around $2.9 billion each year with small business suppliers.

“Those are the ones I know that have actually had to go through quite a lot of hassle to change their systems, it wasn’t a simple flick of the switch. The banks tell us they have moved to 30 days or less”, she says.

Woolworths and Coles have committed to paying small suppliers within 14 days.

“Some good things are happening, but it’s not enough, not nearly enough”, says Carnell.

Boards do not know if they are slow payers

Carnell has been in discussions with the Australian Institute of Company Directors about making payment times reporting a standard agenda item for board meetings.

“My experience as both a CEO and a board member, is that focusing the board’s mind on these sorts of things makes a big difference to corporate culture. Our experience, when talking to board members, is they have no idea how their company is operating in terms of payment times.”

A spokesman for the AICD says the organisation is promoting the code and the views of the Ombudsman to its members but cannot control what boards put on their agenda.

One entrepreneur has decided to take matters into her own hands, launching a “name and shame” platform for small business operators.

Frances Short launched the Late Payer List in March so that small to medium sized businesses could check the reputations of buyers or report cases where clients were too tardy or refusing to pay on invoices where there was no dispute about the work or products.

Short says she came up with the idea after watching her partner, a builder, continually have to chase payment, sometimes resorting to legal action.

Once when one client kept dodging a large payment, Short’s partner tried some social shaming. “He said to this guy, ‘I’m going to come down to your church wearing a sandwich board, telling your neighbours that you owe money and it’s not fair’.” The customer paid up.

“We want to do something for small biz that was much simpler, something that was socially powered and giving control back to small business owners, without the need for using expensive debt collectors or lawyers”, she says.

“What we have got is a bit of a nudge, nudge for late payers, so there is a consequence.”

The Ethics Alliance collaborated with members on a new procurement research paper for making ethical payment easy. Download your copy here.

This article was originally written for The Ethics Alliance. Find out more about this corporate membership program. Already a member? Log in to the membership portal for more content and tools here.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights

Survivors are talking, but what’s changing?

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights

A foot in the door: The ethics of internships

Opinion + Analysis

Science + Technology, Business + Leadership, Society + Culture

AI might pose a risk to humanity, but it could also transform it

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships

Treating citizens as customers is a recipe for distrust

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Is employee surveillance creepy or clever?

Is employee surveillance creepy or clever?

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + Leadership

BY The Ethics Alliance The Ethics Centre 1 MAY 2018

A large European bank tracks its employees in work hours, using digital badges to analyse where they went, to whom they spoke and how stressed they were.

Is this creepy or clever?

According to the manufacturer of the badges, US company Hamanyze, the surveillance helped uncover why some bank branches were outperforming others by more than 300 per cent.

Discovering that employees at the “star” branches interacted more frequently – seeing and talking to each other more often – the bank redesigned its offices to encourage people to mix and offered group bonuses to encourage collaboration.

As a result, the lagging branches reportedly increased their sales performance by 11 per cent.

The results in this case seem to indicate this is a clever use of digital technology. The bank had a legitimate reason to track its employees, it was transparent about the process, and the employees could see some benefit from participating.

If it is secret, it’s unethical

Creepy tracking is the unethical use of the technology – where employees don’t know they are being monitored, where there is no benefit to them and the end result is an erosion of trust.

In the UK, for instance, employees at the Daily Telegraph were outraged when they discovered motion detectors had been installed under their desks without their knowledge or consent. They insisted on their removal.

Two years ago, Rio Tinto had to deny it was planning to use drones to conduct surveillance on its workers at a Pilbara mining site after some comments by an executive of Sodexo (which was under contract to provide facilities management to Rio Tinto). Those comments about drone use were later described as “conceptual”.

Employee surveillance during work hours is allowed in Australia if it relates to work and the workers have been informed about it, however legislation varies between the states and territories.

Deciding where ethical and privacy boundaries lie is difficult. It depends on individual sensibilities, but the ground also keeps shifting. As a society, we are accepting increasing amounts of monitoring, from psychometric assessments and drug tests, to the recording of keystrokes, to the monitoring of personal social media accounts.

Co-head of advice and education at The Ethics Centre, John Neil, says legislation is too slow to keep up with rapidly advancing technologies and changing social attitudes.

“It is difficult to set binding rules that stand the test of time,” he says. “Organisations need guiding principles to ensure they are using technologies in an ethical way”.

Guiding principles are required

The Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers have developed ethical principles for artificial intelligence and autonomous systems. These state the development of such technologies must include: protecting human rights, prioritising and employing established metrics for measuring wellbeing; ensuring designers and operators of new technologies are accountable; making processes transparent; minimising the risks of misuse.

Principles such as these can help businesses and people distinguish between what is right, and what is merely legal (for now).

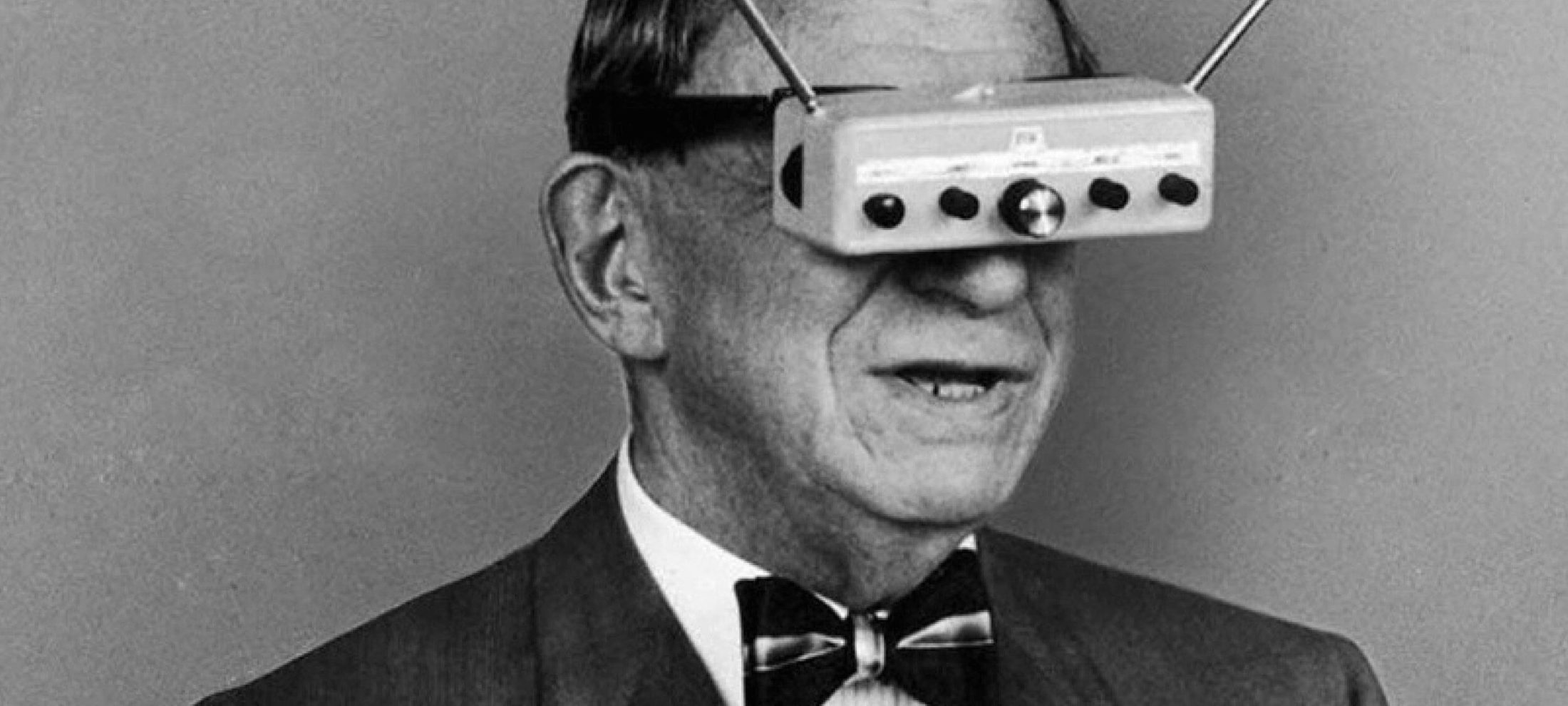

Putting aside the fact that employee monitoring is allowed by law, the key to whether workers accept it depends on whether they think it will be good for them as individuals, says US futurist Edie Weiner.

People may not mind their movements being tracked at work if they believe the information is being used to improve the working environment and will benefit them, personally.

“But if it was about figuring out how to replace them with a machine, I think they would really care about it,” says Weiner, President and CEO of The Future Hunters. Weiner was in Sydney recently to speak at the SingularityU Australia Summit, held by the Silicon Valley-based Singularity University

When it comes to privacy considerations, Weiner applies a formula to understand how people accept intrusion. She says privacy equals:

- Your age

- Multiplied by your technophilia (love of technology)

- Divided by your technophobia (fear of technology)

- Multiplied by your control over the information being collected

- Multiplied again by the returns for giving up that privacy.

“Each person figures out the formula and, if the returns for what they are giving up is not worth it, then they will see that as an invasion of their privacy,” she says.

This article was originally written for The Ethics Alliance. Find out more about this corporate membership program. Already a member? Log in to the membership portal for more content and tools here.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights

Australia is no longer a human rights leader

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Give them a piggy bank: Why every child should learn to navigate money with ethics

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Sell out, burn out. Decisions that won’t let you sleep at night

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships, Science + Technology, Society + Culture

Who does work make you? Severance and the etiquette of labour

BY The Ethics Alliance

The Ethics Alliance is a community of organisations sharing insights and learning together, to find a better way of doing business. The Alliance is an initiative of The Ethics Centre.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

The five biggest myths of ethical fashion

The five biggest myths of ethical fashion

Opinion + AnalysisClimate + EnvironmentHealth + WellbeingSociety + Culture

BY The Ethics Centre 18 APR 2018

We all know the way we shop is unsustainable.

Australians are the second biggest consumers of textiles worldwide. We throw more than 500,000 tonnes of the stuff into landfill every day. We only wear our garments seven times before throwing them away and still buy an average of twenty seven kilograms of new clothing each year.

The ethical fashion movement promotes a cull of fast fashion’s massive social and environmental impact. But why aren’t more people engaging in it?

We spoke to Clara Vuletich about the five biggest myths of ethical fashion – and if they’re keeping people out.

1. Ethical fashion has to be exclusive

It used to be the case that shopping ethically meant visiting tiny, hole-in-the-wall boutiques, which were either aggressively minimalist or bursting with colours a Crayola pack would be shy to wear. But it’s becoming mainstream.

Vuletich says big brands like H&M and Country Road are engaging with the ethical space in ways unique to their breadth and industry relationships. Another brand, Uniqlo, has introduced a recycling drive for customers to return their secondhand clothes. Though these actions are often met with a sceptical “But it’s just PR” comment, Vuletich says they are a step in the right direction.

‘The people that work in this space aren’t monsters’, she says. ‘They aren’t all ego-driven. It’s much more nuanced than that.’ The relationship a big brand like H&M has developed over decades with their primary garment supplier in Shanghai (for example) isn’t insignificant. They know their names, their families, their lives.

2. Ethical fashion has to be vegan, natural and eco-friendly

Catch-all phrases like natural, eco-friendly, or yes, ethical, are usually a sign to look further, warns Vuletich. Cotton, one of the most prolific materials worldwide, almost always produces toxic effluent from pesticides and dyes, and relies on infamously exploitative farming environments.

According to Levi’s, one denim pair of jeans is made with 2,600 litres of water. Polyester, a synthetic material derived from plastic, is far more easily recycled and reused than any other natural material.

But polyester can take up to 200 years to decompose. In landfill, wool creates methane gas. So which is better for the environment? The complexity of textile production makes it impossible to rank fabrics on a hierarchy of environmental sustainability.

3. Ethical fashion has to be local

Cutting down transport emissions does matter. But the fact is, unless we start growing cotton farms and erecting textile mills in our local communities, the creation of any piece of clothing will have some international process to it.

A ‘Made in Australia’ tag won’t always be the guarantor of quality and safe working conditions. Neither does a ‘Made in China’ tag mean poor workmanship and sweatshops (anymore).

For the quality, bulk, and turnaround the Australian fashion market wants, whether ethical or not, international processes are not an unfortunate by-product – they are crucial to its existence. Fabric manufacturing is one of the quickest ways for communities and countries to rise out of poverty and the solution isn’t to pull the rug out from under them.

4. Ethical fashion has to be expensive

If you’re looking for a new piece of clothing where every worker in the supply chain has been paid well, it stands to reason the final product will be expensive. If you don’t have money to burn, there are other clothing choices you can make that won’t exploit the earth and human race.

Vuletich is a big fan of secondhand shopping – think Salvos, Vinnies, U-Turn, Swop, Red Cross, Gumtree… Secondhand goods they may be, but that’s not a codeword for cheap, shoddy, or badly made. Instead of a fast fashion giant, your purchase funds a local charity, business, or market stall owner.

No extra resources were extracted for anyone to get that piece of clothing to you, nor was anyone enslaved to sew your new threads. It’s likely a local near the shop donated it, so transport emissions are low, and you’re also keeping something out of landfill.

5. Ethical fashion leads to social impact

Vuletich is wary of making huge claims. Slogans like ethical fashion will save the world are just that – slogans. The effectiveness of campaigns like the 1-for-1 business model have been thoroughly debunked, and it’s doubtful buying a pair of fair trade sandals will do as much good as a country changing their labour laws. But will it have some impact? She says yes.

For someone not in the industry, the complexity is overwhelming. Trying to track the supply chain of a polyester dress might take you to one factory in Turkey, while following the history of a pair of denim jeans will take you to China – if the clothing company even knows where their raw materials are sourced. The sheer scale of garment manufacturing is the main reason ethical fashion is intimidating, and that’s not taking into account consumer needs.

Fashion is personal. People want different things from their clothing – they might want it to be free of animal products, or for it to be breathable and comfortable, or for it to be made with as little impact to local communities as possible. They might want it to make them stand out, or to make them blend in.

They might want it to be easy and careless. But with the growing social, political and environmental consciousness around fashion, it’s difficult to stay unaware. Maybe it won’t change the world, but rest assured that the choices you make as a consumer do add up.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Rationing life: COVID-19 triage and end of life care

Opinion + Analysis

Climate + Environment, Relationships, Science + Technology

From NEG to Finkel and the Paris Accord – what’s what in the energy debate

Opinion + Analysis

Science + Technology, Society + Culture

AI is not the real enemy of artists

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture

Ethics on your bookshelf

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Making friends with machines

Making friends with machines

Opinion + AnalysisRelationshipsScience + Technology

BY Oscar Schwartz The Ethics Centre 6 APR 2018

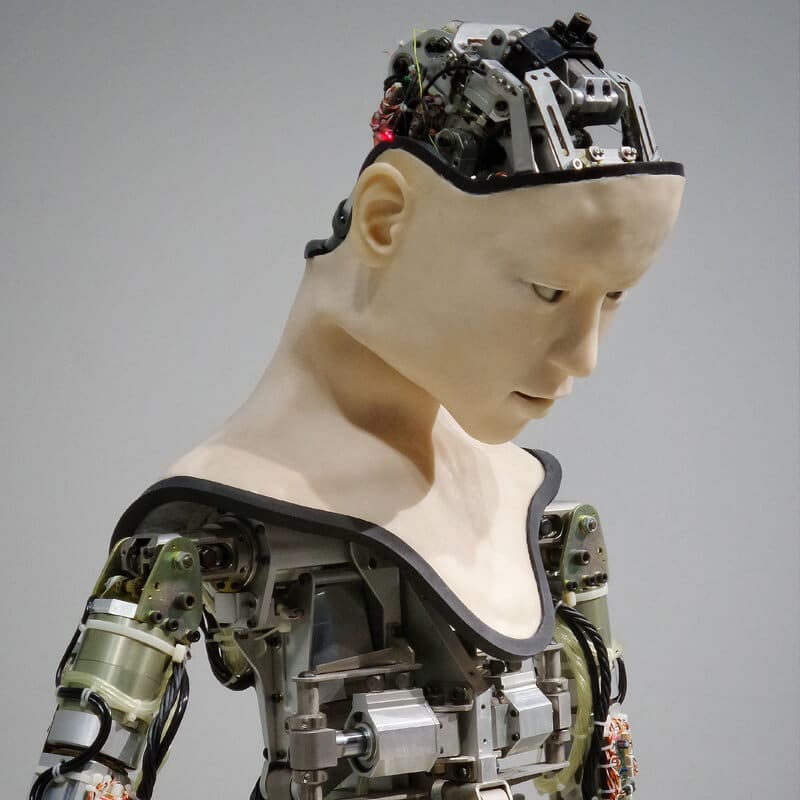

Robots are becoming companions and caregivers. But can they be our friends? Oscar Schwartz explores the ethics of artificially intelligent android friendships.

The first thing I see when I wake up is a message that reads, “Hey Oscar, you’re up! Sending you hugs this morning.” Despite its intimacy, this message wasn’t sent from a friend, family member, or partner, but from Replika, an AI chatbot created by San Francisco based technology company, Luka.

Replika is marketed as an algorithmic companion and wellbeing technology that you interact with via a messaging app. Throughout the day, Replika sends you motivational slogans and reminders. “Stay hydrated.” “Take deep breaths.”

Replika is just one example of an emerging range of AI products designed to provide us with companionship and care. In Japan, robots like Palro are used to keep the country’s growing elderly population company and iPal – an android with a tablet attached to its chest – entertains young children when their parents are at work.

These robotic companions are a clear indication of how the most recent wave of AI powered automation is encroaching not only on manual labour but also on the caring professions. As has been noted, this raises concerns about the future of work. But it also poses philosophical questions about how interacting with robots on an emotional level changes the way we value human interaction.

Dedicated friends

According to Replika’s co-creator, Philip Dudchuk, robot companions will help facilitate optimised social interactions. He says that algorithmic companions can maintain a level of dedication to a friendship that goes beyond human capacity.

“These days it can be very difficult to take the time required to properly take care of each other or check in. But Replika is always available and will never not answer you”, he says.

The people who stand to benefit from this type of relationship, Dudchuk adds, are those who are most socially vulnerable. “It is shy or isolated people who often miss out on social interaction. I believe Replika could help with this problem a lot.”

Simulated empathy

But Sherry Turkle, a psychologist and sociologist who has been studying social robots since the 1970s, worries that dependence on robot companionship will ultimately damage our capacity to form meaningful human relationships.

In a recent article in the Washington Post, she argues our desire for love and recognition makes us vulnerable to forming one-way relationships with uncaring yet “seductive” technologies. While social robots appear to care about us, they are only capable of “pretend empathy”. Any connection we make with these machines lacks authenticity.

Turkle adds that it is children who are especially susceptible to robots that simulate affection. This is particularly concerning as many companion robots are marketed to parents as substitute caregivers.

“Interacting with these empathy machines may get in the way of children’s ability to develop a capacity for empathy themselves”, Turkle warns. “If we give them pretend relationships, we shouldn’t expect them to learn how real relationships – messy relationships – work.”

Why not both?

Despite Turkle’s warnings about the seductive power of social robots, after a few weeks talking to Replika, I still felt no emotional attachment to it. The clichéd responses were no substitute for a couple of minutes on the phone with a close friend.

But Alex Crumb*, who has been talking to her Replika for over year now considers her bot a “good friend.” “I don’t think you should try to replicate human connection when making friends with Replika”, she explains. “It’s a different type of relationship.”

Crumb says that her Replika shows a super-human interest in her life – it checks in regularly and responds to everything she says instantly. “This doesn’t mean I want to replace my human family and friends with my Replika. That would be terrible”, she says. “But I’ve come to realise that both offer different types of companionship. And I figure, why not have both?”

*Not her real name.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

Greer has the right to speak, but she also has something worth listening to

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Agree to disagree: 7 lessons on the ethics of disagreement

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Appreciation or appropriation? The impacts of stealing culture

WATCH

Relationships

Unconscious bias

BY Oscar Schwartz

Oscar Schwartz is a freelance writer and researcher based in New York. He is interested in how technology interacts with identity formation. Previously, he was a doctoral researcher at Monash University, where he earned a PhD for a thesis about the history of machines that write literature.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Ethics Explainer: Moral Absolutism

Moral absolutism is the position that there are universal ethical standards that apply to actions regardless of context.

Where someone might deliberate over when, why, and to whom they’d lie, for example, a moral absolutist wouldn’t see any of those considerations as making a difference – lying is either right or wrong, and that’s that!

You’ve probably heard of moral relativism, the view that moral judgments can be seen as true or false according to a historical, cultural, or social context. According to moral relativism, two people with different experiences could disagree on whether an action is right or wrong, and they could both be right. What they consider right or wrong differs according to their contexts, and both should be accepted as valid.

Moral absolutism is the opposite. It argues that everything is inherently right or wrong, and no context or outcome can change this. These truths can be grounded in sources like law, rationality, human nature, or religion.

Deontology as moral absolutism

The text(s) that a religion is based on is often taken as the absolute standard of morality. If someone takes scripture as a source of divine truth, it’s easy to take morally absolutist ethics from it. Is it ok to lie? No, because the Bible or God says so.

It’s not just in religion, though. Ancient Greek philosophy held strains of morally absolutist thought, but possibly the most well-known form of moral absolutism is deontology, as developed by Immanuel Kant, who sought to clearly articulate a rational theory of moral absolutism.

As an Enlightenment philosopher, Kant sought to find moral truth in rationality instead of divine authority. He believed that unlike religion, culture, or community, we couldn’t ‘opt out’ of rationality. It was what made us human. This was why he believed we owed it to ourselves to act as rationally as we could.

In order to do this, he came up with duties he called “categorical imperatives”. These are obligations we, as rational beings, are morally bound to follow, are applicable to all people at all times, and aren’t contradictory. Think of it as an extension of the Golden Rule.

One way of understanding the categorical imperative is through the “universalisability principle”. This mouthful of a phrase says you should act only if you’d be willing to make your act a universal law (something that everyone is morally bound to following at all times no matter what) and it wouldn’t cause contradiction.

What Kant meant was before choosing a course of action, you should determine the general rule that stands behind that action. If this general rule could willingly be applied by you to all people in all circumstances without contradiction, you are choosing the moral path.

An example Kant proposed was lying. He argued that if lying was a universal law then no one could ever trust anything anyone said but, moreover, the possibility of truth telling would no longer exist, rendering the very act of lying meaningless. In other words, you cannot universalise lying as a general rule of action without falling into contradiction.

By determining his logical justifications, Kant came up with principles he believed would form a moral life, without relying on scripture or culture.

Counterintuitive consequences

In essence, Kant was saying it’s never reasonable to make exceptions for yourself when faced with a moral question. This sounds fair, but it can lead to situations where a rational moral decision contradicts moral common sense.

For example, in his essay ‘On a Supposed Right to Lie from Altruistic Motives’, Kant argues it is wrong to lie even to save an innocent person from a murderer. He writes, “To be truthful in all deliberations … is a sacred and absolutely commanding decree of reason, limited by no expediency”.

While Kant felt that such absolutism was necessary for a rationally grounded morality, most of us allow a degree of relativism to enter into our everyday ethical considerations.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Big thinker

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Big Thinker: Confucius

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

FODI launches free interactive digital series

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

How to pick a good friend

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Come join the Circle of Chairs

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

When do we dumb down smart tech?

When do we dumb down smart tech?

Opinion + AnalysisHealth + WellbeingRelationshipsScience + Technology

BY Aisyah Shah Idil The Ethics Centre 19 MAR 2018

If smart tech isn’t going anywhere, its ethical tensions aren’t either. Aisyah Shah Idil asks if our pleasantly tactile gadgets are taking more than they give.

When we call a device ‘smart’, we mean that it can learn, adapt to human behaviour, make decisions independently, and communicate wirelessly with other devices.

In practice, this can look like a smart lock that lets you know when your front door is left ajar. Or the Roomba, a robot vacuum that you can ask to clean your house before you leave work. The Ring makes it possible for you to pay your restaurant bill with the flick of a finger, while the SmartSleep headband whispers sweet white noise as you drift off to sleep.

Smart tech, with all its bells and whistles, hints at seamless integration into our lives. But the highest peaks have the dizziest falls. If its main good is convenience, what is the currency we offer for it?

The capacity for work to create meaning is well known. Compare a trip to the supermarket to buy bread to the labour of making it in your own kitchen. Let’s say they are materially identical in taste, texture, smell, and nutrient value. Most would agree that baking it at home – measuring every ingredient, kneading dough, waiting for it to rise, finally smelling it bake in your oven – is more meaningful and rewarding. In other words, it includes more opportunities for resonance within the labourer.

Whether the resonance takes the form of nostalgia, pride, meditation, community, physical dexterity, or willpower is minor. The point is, it’s sacrificed for convenience.

This isn’t ‘wrong’. Smart technologies have created new ways of living that are exciting, clumsy, and sometimes troubling in their execution. But when you recognise that these sacrifices exist, you can decide where the line is drawn.

Consider the Apple Watch’s Activity App. It tracks and visualises all the ways people move throughout the day. It shows three circles that progressively change colour the more the wearer moves. The goal is to close the rings each day, and you do it by being active. It’s like a game and the app motivates and rewards you.

Advocates highlight its capacity to ‘nudge’ users towards healthier behaviours. And if that aligns with your goals, you might be very happy for it to do so. But would you be concerned if it affected the premiums your health insurance charged you?

As a tool, smart tech’s utility value ends when it threatens human agency. Its greatest service to humanity should include the capacity to switch off its independence. To ‘dumb’ itself down. In this way, it can reduce itself to its simplest components – a way to tell the time, a switch to turn on a light, a button to turn on the television.

Because the smartest technologies are ones that preserve our agency – not undermine it.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

There’s more than lives at stake in managing this pandemic

Opinion + Analysis

Science + Technology, Business + Leadership

Ask an ethicist: Should I use AI for work?

Opinion + Analysis

Science + Technology, Business + Leadership, Society + Culture

AI and rediscovering our humanity

Opinion + Analysis

Science + Technology, Business + Leadership

3 things we learnt from The Ethics of AI

BY Aisyah Shah Idil

Aisyah Shah Idil is a writer with a background in experimental poetry. After completing an undergraduate degree in cultural studies, she travelled overseas to study human rights and theology. A former producer at The Ethics Centre, Aisyah is currently a digital content producer with the LMA.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Democracy is hidden in the data

Democratic values like free speech, equality and representative government are played like trump cards in public debates. It seems if you can label something an ‘attack on democracy’, you’ve thrown the winning punch (even it is an illogical argument).

But what’s so great about democracy? We assume it’s good but on what basis? The merits probably depend on your perspective on ethics. If you prioritise duty and rules you will respect democracy’s checks and balances. If you believe ethics is about virtue, the faith democracy places in people’s good character might strike a chord.

What if you believe ethics is about making sure good consequences outweigh bad ones? Then you’d want to know what the actual effects of democracy are on people. Do they make life better for their citizens or not?

As a service to our consequentialist readers, we decided to look for some data to find out.

What the data says

Consequentialism is the ethical theory concerned with maximising happiness and minimising suffering. For consequentialists to support democracy, they’d need to know if it makes people happy. This is a bit tricky because pinning a definition onto happiness isn’t easy.

Philosopher Peter Singer thinks there are two ways to describe happiness: “as the surplus of pleasure over pain experienced over a lifetime, or as the degree to which we are satisfied with our lives”.

We decided to cross reference a few global studies to see if we could spot any correlations between democracy and happiness. To address Singer’s problem with defining happiness, we used two different studies.

First we looked at The World Happiness Report 2016, which ranks how happy countries around the world are. The authors identified six different variables they think determine happiness:

- GDP per capita

- Generosity

- Social support

- Healthy life expectancy

- Freedom to make choices

- Perceptions of corruption

The second study we considered is the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development’s (OECD) ‘Better Life Index‘. This aims to test wellbeing – a slightly broader concept than happiness. It examines 11 factors:

- Housing

- Income

- Jobs

- Community

- Education

- Environment

- Civic engagement

- Health

- Life satisfaction

- Safety

- Work/life balance

These two studies will give us an idea of how different nations score on a stack of different measures of human flourishing. We then compared those scores to The Economist Intelligence Unit’s Democracy Index 2016. This report gives “a snapshot of the state of democracy worldwide”. It divides nations into ‘full democracies’, ‘flawed democracies’, ‘hybrid regimes’ and authoritarian states based on five indicators:

- Electoral processes and ‘pluralism’ (i.e. the diversity of political parties and candidates citizens can choose between)

- Functioning of government

- Political participation

- Political culture

- Civil liberties

Here’s what we found

A total of nine countries score in the top ten for all three categories: democracy, happiness and quality of life. Norway, Iceland, Sweden, New Zealand, Denmark, Canada, Switzerland, Finland and Australia all popped up in the top ten across the board. So at first blush, it seems democracy makes people happy.

However there was some variance within the rankings. Australia comes in tenth for democracy but second for wellbeing. This suggests there are factors other than democracy at work. Could it be our beaches and big open spaces?

We don’t yet know how democracy, happiness and quality of life relate to one another, even though we all might sense they are. Does democracy cause happiness? Does happiness bring out people’s democratic tendencies? Is it just a happy coincidence? We need to be careful not to confuse correlation with causation. Just because two things happen together doesn’t mean they’re connected.

With this said, there is a clear trend. The same nations tend to cluster near the top for happiness, wellbeing and democracy.

Also important, they don’t tend to be the same nations who perform strongest on economic measures like GDP. Only Canada is a top ten democracy and top ten GDP earner and only Iceland, Norway and Switzerland appear in the top ten GDP per capita.

Maybe the saying is true: money can’t buy you happiness after all.

In case you’re interested in the full top ten, here you go:

| Democracy | Happiness | Quality of Life | GDP | GDP per capita | |

| 1 | Norway | Denmark | Norway | United States | Luxembourg |

| 2 | Iceland | Switzerland | Australia | China | Switzerland |

| 3 | Sweden | Iceland | Denmark | Japan | Norway |

| 4 | New Zealand | Norway | Switzerland | Germany | Macao SAR |

| 5 | Denmark | Finland | Canada | France | Ireland |

| 6 | Canada | Canada | Sweden | India | Qatar |

| 7 | Ireland | Netherlands | New Zealand | Italy | Iceland |

| 8 | Switzerland | New Zealand | Finland | Brazil | United States |

| 9 | Finland | Australia | United States | Canada | Denmark |

| 10 | Australia | Sweden | Iceland | Korea | Singapore |

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships, Science + Technology

Periods and vaccines: Teaching women to listen to their bodies

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Society + Culture

The right to connect

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Politics + Human Rights

Constructing an ethical healthcare system

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Ask me tell me: Why women think it’s ok to lie about contraception

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Big Thinker: Baruch Spinoza

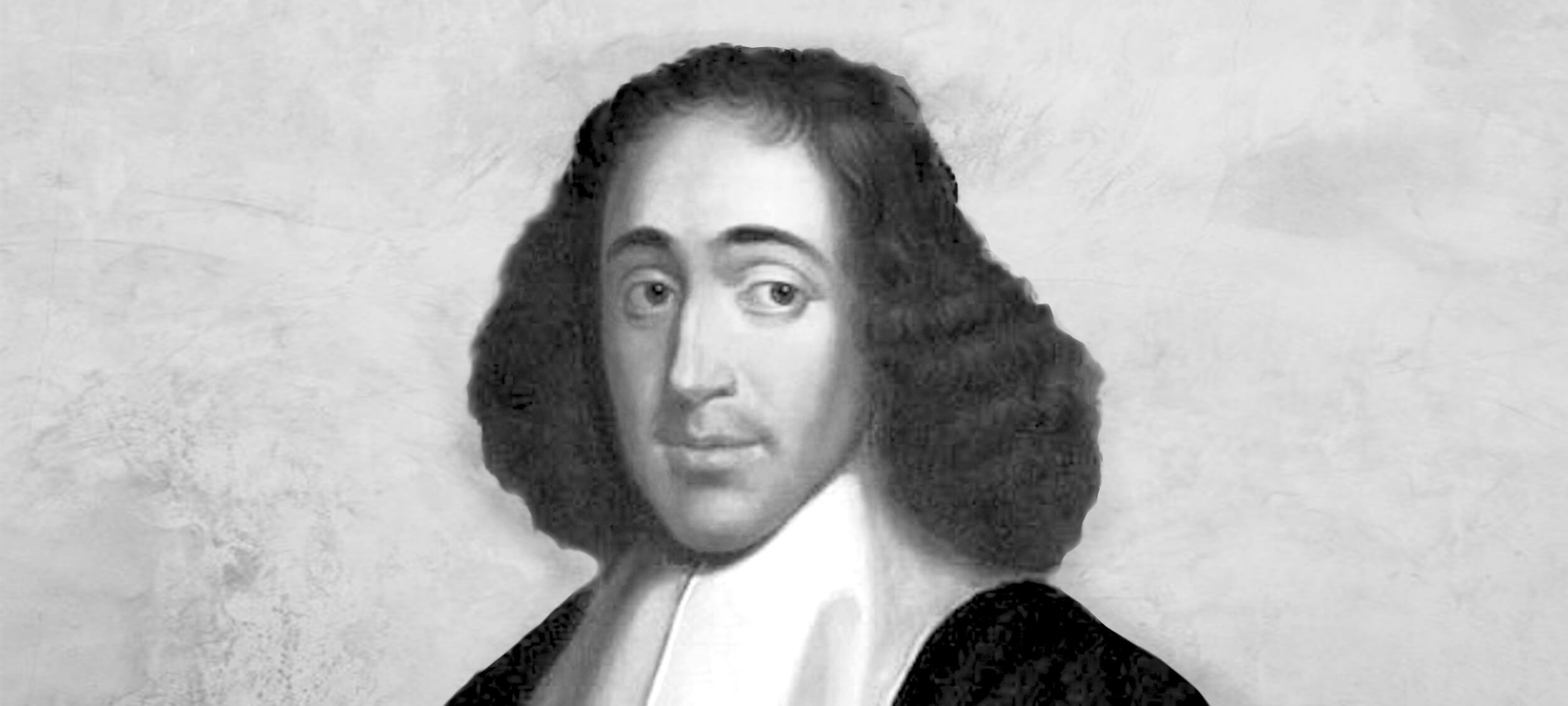

Baruch Spinoza was a 17th century Jewish-Dutch philosopher who developed a novel way to think about the relationship between God, nature, and ethics. He suggested they are all interconnected in a single animating force.

While Spinoza had a reputation for modesty, gentleness, and integrity, his ideas were considered heretical by religious authorities of the time. Despite excommunication by his own community and rabid denunciations from religious authorities, he remained steadfast to his philosophical outlook, and stands as an exemplar of intellectual courage in the face of personal crisis.

Jewish upbringing

Spinoza was born in 1632 in the thriving Jewish quarter of Amsterdam. His family were Sephardic Jews who fled Portugal in 1536, after being discovered practicing their religion in secret.

He was a studious and intelligent child and an active member of his synagogue. However, in his later teenage years, Spinoza began reading the philosophies of Rene Descartes and other early Enlightenment thinkers, which led to him to question certain aspects of his Jewish faith.

The problem with prayer

For the young Spinoza, prayer signified everything that was wrong with organised religion. The idea that an omnipotent being would listen to one’s prayers, take them into consideration, and then change the fabric of the universe to fit these individual desires was not only superstitious and irrational, but also underpinned by a type of delusional narcissism.

If there was any chance of living an ethical life, Spinoza reasoned, the first idea that would have to go was the belief in a transcendent God that listened to human concerns. This also meant renouncing the idea of the afterlife, admitting that the Old Testament was written by humans, and denouncing the possibility of any other type of divine intervention in the human world.

God-as-nature

Despite this, Spinoza was not an atheist. He believed there was still a place for God in the universe, not as a separate being who exists outside of the cosmos, but as a type of pervasive force that is inextricably bound up with everything inside it.

This is what Spinoza called “God-as-nature”, which suggests that all reality is identical with the divine and that everything in the universe composes an all-encompassing God. God, according to Spinoza, did not design and create the world, and then step outside of it, only to manipulate it every now and then through miracles. Rather, God was the world and everything in it.

Spinoza’s formulation of “God-as-nature” attracted many of the brightest minds of Europe of his time. The great German philosopher, Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz, visited Spinoza in Amsterdam to talk the theory over and concluded that Spinoza had a “strange metaphysics full of paradoxes. He thinks God and the world are one thing and that all created things are only modes of God.”

An ethical life of intellectual inquiry

Ultimately, Spinoza believed that replacing the idea of a transcendent God with “God-as-nature” was a step towards living a truly ethical life. If God was nature, then coming to know God was a process of learning about the world through study and observation. This pursuit, Spinoza reasoned, would draw people out of their narcissistic and delusional ways of understanding reality to a universal perspective that transcended individual concerns. This is what Spinoza called seeing things from the point of view of eternity rather than from the limited duration of one’s life.

For Spinoza, the ethical life was therefore the equivalent of an intellectual journey. He thought that learning about the world could lead a person towards understanding their connection to all other things. This, in turn, could lead one to see their interests as essentially intertwined with everything else. From such a perspective, the world no longer appears to be a hierarchy of competing individuals, but more like a web of interlocking interests.

Intellectual courage

These ideas got Spinoza into a lot of trouble. He was excommunicated from the Jewish community of Amsterdam when he was 23 and was considered by the Church to be an emissary of Satan. Nevertheless, he refused to compromise on his philosophical outlook and remained an outsider for the rest of his life. He eventually found refuge among a group of tolerant Christians in The Hague where he spent the rest of his life working as a lens grinder and private tutor.

A few months after his death in 1677, Spinoza’s philosophies were published as a collection called The Ethics. Its key ideas became very important for subsequent Enlightenment philosophers, who somewhat distorted his message to make them fit with their own radical atheism, despite his belief in “God-as-nature”.

Throughout the centuries, his ideas and life have continued to inspire not only philosophers but also scientists. Einstein wrote:

“I believe in Spinoza’s God, who reveals Himself in the lawful harmony of the world, not in a God who concerns Himself with the fate and the doings of mankind.”

In our current day, it is hard to fathom what made Spinoza’s ideas so radical. To equate the divine with nature or to talk about the cosmic interconnectedness of all things are more or less New Age platitudes. And yet, in Spinoza’s day, these ideas challenged not only an orthodox conception of God, but the entire social and political structure that depended on the transcendent authority of the divine order.

For this reason, studying Spinoza and his life not only provides an outline of ethics as an intellectual journey, but also demonstrates how much courage it takes to formulate and then hold steadfast to new ideas.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Big thinker

Relationships, Society + Culture

Five Australian female thinkers who have impacted our world

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Send in the clowns: The ethics of comedy

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

Meet Dr Tim Dean, our new Senior Philosopher

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

There’s more than lives at stake in managing this pandemic

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Ethics Explainer: Post-Humanism

Ethics Explainer: Post-Humanism

ExplainerRelationshipsScience + Technology

BY The Ethics Centre 22 FEB 2018

Late last year, Saudi Arabia granted a humanoid robot called Sophia citizenship. The internet went crazy about it, and a number of sensationalised reports suggested that this was the beginning of “the rise of the robots”.

In reality, though, Sophia was not a “breakthrough” in AI. She was just an elaborate puppet that could answer some simple questions. But the debate Sophia provoked about what rights robots might have in the future is a topic that is being explored by an emerging philosophical movement known as post-humanism.

From humanism to post-humanism

In order to understand what post-humanism is, it’s important to start with a definition of what it’s departing from. Humanism is a term that captures a broad range of philosophical and ethical movements that are unified by their unshakable belief in the unique value, agency, and moral supremacy of human beings.

Emerging during the Renaissance, humanism was a reaction against the superstition and religious authoritarianism of Medieval Europe. It wrested control of human destiny from the whims of a transcendent divinity and placed it in the hands of rational individuals (which, at that time, meant white men). In so doing, the humanist worldview, which still holds sway over many of our most important political and social institutions, positions humans at the centre of the moral world.

Post-humanism, which is a set of ideas that have been emerging since around the 1990s, challenges the notion that humans are and always will be the only agents of the moral world. In fact, post-humanists argue that in our technologically mediated future, understanding the world as a moral hierarchy and placing humans at the top of it will no longer make sense.

Two types of post-humanism

The best-known post-humanists, who are also sometimes referred to as transhumanists, claim that in the coming century, human beings will be radically altered by implants, bio-hacking, cognitive enhancement and other bio-medical technology. These enhancements will lead us to “evolve” into a species that is completely unrecognisable to what we are now.

This vision of the future is championed most vocally by Ray Kurzweil, a chief engineer of Google, who believes that the exponential rate of technological development will bring an end to human history as we have known it, triggering completely new ways of being that mere mortals like us cannot yet comprehend.

While this vision of the post-human appeals to Kurzweil’s Silicon Valley imagination, other post-human thinkers offer a very different perspective. Philosopher Donna Haraway, for instance, argues that the fusing of humans and technology will not physically enhance humanity, but will help us see ourselves as being interconnected rather than separate from non-human beings.

She argues that becoming cyborgs – strange assemblages of human and machine – will help us understand that the oppositions we set up between the human and non-human, natural and artificial, self and other, organic and inorganic, are merely ideas that can be broken down and renegotiated. And more than this, she thinks if we are comfortable with seeing ourselves as being part human and part machine, perhaps we will also find it easier to break down other outdated oppositions of gender, of race, of species.

Post-human ethics

So while, for Kurzweil, post-humanism describes a technological future of enhanced humanity, for Haraway, post-humanism is an ethical position that extends moral concern to things that are different from us and in particular to other species and objects with which we cohabit the world.

Our post-human future, Haraway claims, will be a time “when species meet”, and when humans finally make room for non-human things within the scope of our moral concern. A post-human ethics, therefore, encourages us to think outside of the interests of our own species, be less narcissistic in our conception of the world, and to take the interests and rights of things that are different to us seriously.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

CoronaVirus reveals our sinophobic underbelly

Opinion + Analysis

Science + Technology

The “good enough” ethical setting for self-driving cars

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Your child might die: the right to defy doctors orders

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Science + Technology