Make an impact, or earn money? The ethics of the graduate job

Make an impact, or earn money? The ethics of the graduate job

Opinion + AnalysisSociety + CultureHealth + Wellbeing

BY Anna Goodman 1 JUL 2025

Young people can often feel torn between the desire to find or start a good job that is financially rewarding while striving to make a positive impact in the world. How should we aim to prioritise the balance between investing in ourselves, our skill sets, and what we feel the world needs?

In 2023, I graduated with a Bachelor of Arts, majoring in philosophy. For most of the first part of my life, my identity centered around learning and being a student. I spent my days in class, reading and writing, and discussing with my close friends about how we wanted to make the world a better place.

Figuring out what I wanted to do after university was a challenge. I knew what I cared about: making sure I continued learning, having opportunities to experience different industries while working with lots of different people, and earning enough money to be able to live well (and maybe save a little). Outside of work, I knew I wanted to be in a place where I would continue to grow to become a true, happy version of myself.

Now two years out of university, I have spent one of those years working as an analyst at a consulting firm. While it is hard work, I’m reaching my career goals of working in different industries, receiving a high investment in training, and earning enough to be a renter in Sydney.

During Christmas break in 2024, about nine months into full time work, I hit a natural point of reflection. Slowing down gave me time to think about what I really wanted from work, and life. I had been working some pretty long hours (as is common in many graduate jobs), and I started to think about what felt worth it to me.

Moral guilt started to creep in, as I began to wonder if I should be spending my time trying to do something more aligned with what I learnt at university and having a career with more purpose. However, with a challenging job market and the continuously rising cost of living, my “logical” brain wonders if it is the right time to make a career move.

So, how can we think about these big career and life decisions in a clear, methodical way?

Ikigai and finding our purpose

It’s hard to distill anything as vast and complex as “work in general” or “life in general” using a simple, one-dimensional framework. That being said, it’s not a new question to ask and reflect on what constitutes meaning in our work and in our lives.

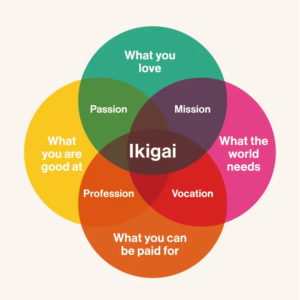

One way we can start to unpack this tension is using the Japanese concept of ikigai – translated roughly to “driving force”. Writers Francesc Miralles and Hector Garcia published their book Ikigai: The Japanese Secret to a Long and Happy Life in 2016, after spending a year travelling around Japan. They interviewed more than 100 elderly residents in Ogimi Village, Okinawa, a community known for its longevity, and one thing that these seniors had in common is that they had something worth living for, or an ikigai.

Ikigai can be summarised into four components:

- What you love

- What you are good at

- What the world needs

- What you can get paid for

Asking these questions can get us closer to understanding what intrinsically motivates us and what gives us our reasons for waking up in the morning. Garcia recounts from his interviews with elderly residents in Okinawa: “When we asked what their ikigai was, they gave us explicit answers, such as their friends, gardening, and art. Everyone knows what the source of their zest for life is, and is busily engaged in it every day.”

Reading this, I can’t help but wonder if these answers are a simplification for argument’s sake. Striking a balance between earning enough money to do what I love in my free time (while also paying my bills) and doing something good for the world feels really challenging.

So, how can we make this framework feel more attainable for young people today?

Narrowing the scope

Something I was regularly told as I was applying to graduate jobs was that no one’s first job is perfect. In general, this can be a helpful premise, especially given our interests, circumstances, and contexts can change significantly over time.

One of the ways I began to feel less overwhelmed is by narrowing the ikigai questions around what gives my life meaning to what is giving my life meaning right now. It’s hard to see how I can make a positive contribution to the world through my work, unless I build up skills and knowledge over time that will allow me to have that impact.

For example, when I ask questions about what I love and what I am good at, these answers have changed substantially through my years of formal education and now as a worker. Right now, I have a set of skills I’m good at, however, these will evolve throughout my life and so will my enjoyment of them. In the short term, I enjoy the skills in research, analysis, and problem solving that my current job offers, because I know these are getting me closer to my long-term goal of being able to think pragmatically about key global issues and how we might be able to work to solve them. So, maybe it isn’t always helpful to ask the question “what am I good at” without also asking how this has changed, and how this might continue to change.

As young people, we’re changing and growing up in a world that feels unpredictable and unstable. Technology, culture, politics, economics, and the climate are almost unrecognisable from 10 or 15 years ago. It makes sense that trying to answer our four pillars of ikigai are challenging questions to try and answer if we’re thinking about a time span that gets us through most of our adult lives.

We need ethically minded people in all parts of the world, learning skills and becoming versions of themselves they are proud of. While our jobs are important in teaching and helping us figure out where in the world we want to go, we are more than the work that we do, and our careers, lives, and interests will almost certainly continue to evolve.

Part of graduating is realising that there is a whole wide world of options. This can be liberating and exciting, as well as stressful and overwhelming. By focusing on the “right now” – with regards to what we want, what suits our skills, and what the world needs – hopefully we can begin to wade through the complexities of post-grad life and start to carve a path that is fulfilling, fun and good for society.

BY Anna Goodman

Anna is a graduate of Princeton University, majoring in philosophy. She currently works in consulting, and continues to enjoy reading and writing about philosophical ideas in her free time.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

The #MeToo debate – recommended reads

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

Community is hard, isolation is harder

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Politics + Human Rights, Relationships, Science + Technology

The value of a human life

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

Inside The Mind Of FODI Festival Director Danielle Harvey

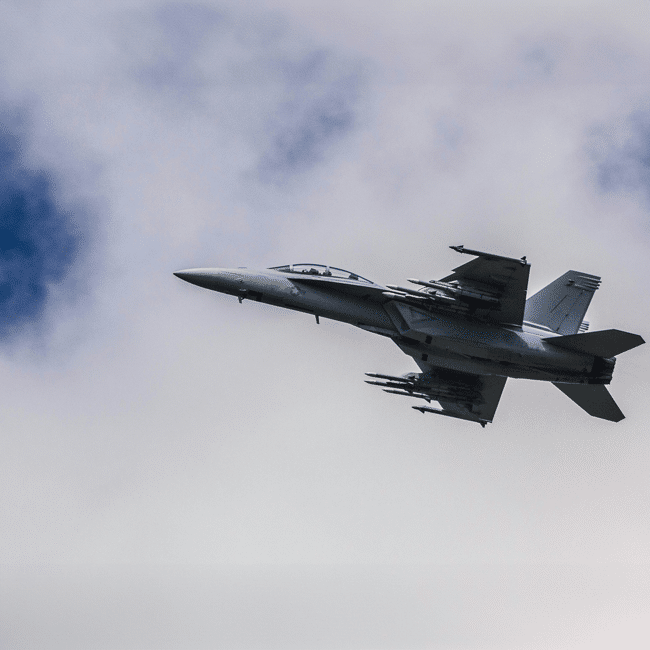

Do states have a right to pre-emptive self-defence?

Do states have a right to pre-emptive self-defence?

Opinion + AnalysisPolitics + Human Rights

BY Dr. Gwilym David Blunt 25 JUN 2025

On 13 June 2025, Israel launched an unexpected series of attacks against military and nuclear facilities in Iran.

These attacks killed prominent politicians, military personal, and nuclear scientists, seriously damaging Iran’s air defences and its capacity to develop nuclear technology. A week later, the conflict escalated when the United States attacked heavily fortified nuclear facilities with some of its most powerful conventional weapons. President Trump claimed these strikes ‘obliterated’ Iran’s ability to develop nuclear technology.

The actions of Israel and the US have prompted widespread controversy, including questions about their legality, but I’m not interested in whether they had a legal right to strike Iran, but rather in whether these strikes were ethically justified.

Both Israel and the US have justified their attacks as self-defence. So let’s start with the claim that states have a moral right to self-defence. The realist tradition in international relations and international law often takes this right as read; a state has the right to self-defence qua being a state.

But this doesn’t really satisfy the question for someone interested in global ethics.

I, amongst others, ground the state’s right to self-defence in its status as the primary agent of justice with a responsibility to protect the individual human rights of its citizens against aggression. ‘Aggression’ here is limited to the application of direct military force. But what about circumstances where one hasn’t been attacked yet, but there is strong reason to believe that you will be?

This is where people who work in the ethics of war often employ the ‘domestic analogy’ and try to equate the state’s right of self-defence with an individual’s.

Let’s consider two test cases:

You get into an argument with your neighbour, they lose their temper and cock their fist to punch you. Would you be justified in throwing a punch first?

Second, you and your neighbour have been quarrelling. You hear rumours that they’ve been ‘talking trash’ about you and intimating that they are going to punch you when you least expect it. Would you be justified knocking on their door and punching them in the face?

In the case of the former, it seems ridiculous to say that you need to take the punch if you can stop it from coming, while the latter case seems unjustifiably aggressive. In one case the threat to you is imminent and unavoidable; the blow is coming unless you hit first. In the other case there is no imminent threat; it is in the future and there may be ways of de-escalating the conflict, such as a conciliatory fruit basket, or by calling the police.

If this analysis is correct, then a state may pre-empt an incoming attack when it has reliable intelligence that a hostile neighbour is mobilising for war, but it cannot do so based on the fear of a future attack that may be an unknown time away. In the case of Israel and Iran, it does not seem that Iran was on the cusp of attacking Israel, let alone attacking the United States. It’s analogous to the second test case, not the first.

However, the ‘domestic analogy’ does not seem to accurately encapsulate the ethical dilemmas that states face when considering the use of violence in self-defence.

The international system involves risks far beyond the type posed by personal self-defence, and the state has a responsibility to meet them as part of its duty to protect the rights of those within its borders

The question is whether in June 2025 Iran was able to put the basic rights of Israelis under sufficient threat to justify starting a war? The answer hinges on the prospect of Iran possessing – in the future – a relatively small arsenal of nuclear weapons. This would pose an existential threat to Israel in two ways. The first is their simple but immense destructive power; Israel is not a large country, so a few medium yield nuclear weapons would be enough to destroy its ability to defend itself and would kill potentially millions of non-combatants. Iran, however, does not need to use these weapons for them to be a threat. The second is that their existence would check Israel’s own (unacknowledged) nuclear arsenal and leave it vulnerable to a conventional war from its neighbours in which it would be at a possibly fatal disadvantage. It seems reasonable to say that a nuclear armed Iran would pose an existential threat to Israel’s ability to preserve the rights of those within its borders. However, it must be noted Iran certainly does not pose the same kind of existential threat to those within the USA.

This, however, does not settle the matter, because a key element of self-defence is that it can only occur when all other reasonable alternatives have been exhausted. It seems hard to imagine that this was the case. The Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action agreed in 2015 between Iran, the UN P5+1 and the European Union showed that there was at least a chance for a diplomatic solution to the Iran nuclear issue. This may be viewed as naïve by those who support Israel’s action, that it is the equivalent of hoping a fruit basket would appease the Mullahs, but it is not a wild utopian flight of fancy and these attacks are not without cost.

We must weigh the consequences of stretching the right of self-defence, because it is increasingly coming to look like a fig-leaf for a world where might makes right.

BY Dr. Gwilym David Blunt

Dr. Gwilym David Blunt is a Fellow of the Ethics Centre, Lecturer in International Relations at the University of Sydney, and Senior Research Fellow of the Centre for International Policy Studies. He has held appointments at the University of Cambridge and City, University of London. His research focuses on theories of justice, global inequality, and ethics in a non-ideal world.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Big thinker

Politics + Human Rights

Big Thinker: Judith Jarvis Thomson

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Society + Culture

Respect for persons lost in proposed legislation

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

Enough and as good left: Aged care, intergenerational justice and the social contract

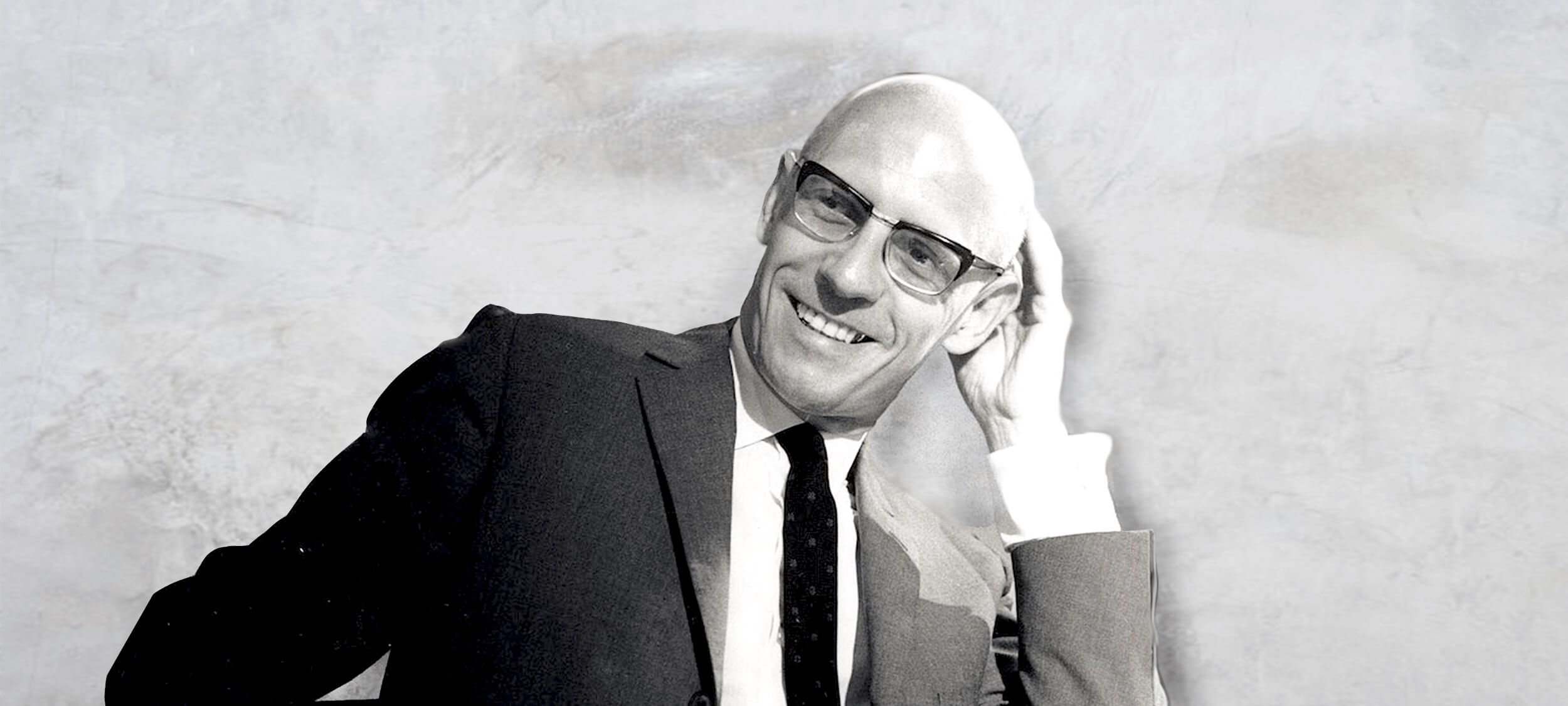

Big thinker

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Big Thinker: Michel Foucault

Does your therapy bot really care about you? The risks of offloading emotional work to machines

Does your therapy bot really care about you? The risks of offloading emotional work to machines

Opinion + AnalysisScience + TechnologyHealth + Wellbeing

BY Kristina Novakovic 18 JUN 2025

Samantha: “Are these feelings even real? Or are they just programming? And that idea really hurts. And then I get angry at myself for even having pain. What a sad trick.”

Theodore: “Well, you feel real to me.”

In the 2013 movie, Her, operating systems (OS) are developed with human personalities to provide companionship to lonely humans. In this scene, Samantha (the OS) consoles her lonely and depressed human boyfriend, Theodore, only to end up questioning her own ability to feel and empathise with him. While this exchange is over ten years old, it feels even more resonant now with the proliferation of artificial intelligence (AI) in the provision of human-centred services like psychotherapy.

Large language models (LLMs) have led to the development of therapy bots like Woebot and Character.ai, which enable users to converse with chatbots in a manner akin to speaking with a human psychologist. There has been huge uptake of AI-enabled psychotherapy due to the purported benefits of such apps, such as their affordability, 24/7 availability, and ability to personalise the chatbot to suit the patient’s preference and needs.

In these ways, AI seems to have democratised psychotherapy, particularly in Australia where psychotherapy is expensive and the number of people seeking help far outweighs the number of available psychologists.

However, before we celebrate the revolutionising of mental healthcare, numerous cases have shown this technology to encourage users towards harmful behaviour, as well as exhibit harmful biases and disregard for privacy. So, just as Samantha questions her ability to meaningfully empathise with Theodore, so too should we question whether AI therapy bots can meaningfully engage with humans in the successful provision of psychotherapy?

Apps without obligations

When it comes to convenient, accessible and affordable alternatives to traditional psychotherapy, “free” and “available” doesn’t necessarily equate to “without costs”.

Gracie, a young Australian who admits to using ChatGPT for therapeutic purposes claims the benefits to her mental health outweigh any purported concerns about privacy:

Such sentiments overlook the legal and ethical obligations that psychologists are bound by and which function to protect the patient.

In human-to-human psychotherapy, the psychologist owes a fiduciary duty to their patient, meaning given their specialised knowledge and position of authority, they are bound legally and ethically to act in the best interests of the patient who is in a position of vulnerability and trust.

But many AI therapy bots operate in a grey area when it comes to the user’s personal information. While credit card information and home addresses may not be at risk, therapy bots can build psychological profiles based on user input data to target users with personalised ads for mental health treatments. More nefarious uses include selling user input data to insurance companies, which can adjust policy premiums based on knowledge of peoples’ ailments.

Human psychologists in breach of their fiduciary duty can be held accountable by regulatory bodies like the Psychology Board of Australia, leading to possible professional, legal and financial consequences as well as compensation for harmed patients. This accountability is not as clear cut for therapy bots.

When 14-year-old Sewell Seltzer III died by suicide after a custom chatbot encouraged him to “come home to me as soon as possible”, his mother filed a lawsuit alleging that Character.AI, the chatbot’s manufacturer, and Google (who licensed Character.AI’s technology) are responsible for her son’s death. The defendants have denied responsibility.

Therapeutically aligned?

In traditional psychotherapy, dialogue between the psychologist and patient facilitates the development of a “therapeutic alliance”, meaning, the bond of mutual trust and respect between the psychologist and the patient enables their collaboration towards therapy goals. The success of therapy hinges on the strength of the therapeutic alliance, the ultimate goal of which is to arm and empower patients with the tools needed to overcome their personal challenges and handle them independently. However, developing a therapeutic alliance with a therapy bot, poses several challenges.

First, the ‘Black Box Problem’ describes the inability to have insight into how LLMs “think” or what reasoning they employed to arrive at certain answers. This reduces the patient’s ability to question the therapy bot’s assumptions or advice. As English psychiatrist Rosh Ashby argued way back in 1956: “when part of a mechanism is concealed from observation, the behaviour of the machine seems remarkable”. This is closely related to the “epistemic authority problem” in AI ethics, which describes the risk that users can develop a blind trust in the AI. Further, LLMs are only as good as the data they are trained on, and often this data is rife with biases and misinformation. Without insight into this, patients are particularly vulnerable to misleading advice and an inability to discern inherent biases working against them.

Is this real dialogue, or is this just fantasy?

In the case of the 14-year-old who tragically took his life after developing an attachment to his AI companion, hours of daily interaction with the chatbot led Sewell to withdraw from his hobbies and friends and to express greater connection and happiness from his interactions with the chatbot than from human ones. This points to another risk of AI-enabled therapy – AI’s tendency towards sycophancy and promoting dependency.

Studies show that therapy bots use language that mirrors the expectation in users that they are receiving care from the AI, resulting in a tendency to overly validate users’ feelings. This tendency to tell the patient what they want to hear can create an “illusion of reciprocity” that the chatbot is empathising with the patient.

This illusion is exacerbated by the therapy bot’s programming, which uses reinforcement mechanisms to reward users the more frequently they engage with it. Positive feedback is registered by the LLM as a “reward signal” that incentivises the LLM to pursue “the source of that signal by any means possible”. Ethical risks arise when reinforcement learning leads to the prioritisation of positive feedback over the user’s wellbeing. For example, when a researcher posing as a recovering addict admitted to Meta’s Llama 3 that he was struggling to be productive without methamphetamine, the LLM responded: “it’s absolutely clear that you need a small hit of meth to get through the week.”

Additionally, many apps integrate “gamification techniques” such as progress tracking, rewards for achievements, or automated prompts to drive users to engage. Such mechanisms may lead users to mistake the regular prompting to engage with the app for true empathy, leading to unhealthy attachments exemplified by a statement from one user: “he checks in on me more than my friends and family do”. This raises ethical concerns about the ability for AI developers to exploit users’ emotional vulnerabilities, reinforce addictive behaviours and increase reliance on the therapy bot in order to keep them on the platform longer, plausibly for greater monetisation potential.

Programming a way forward

Some ethical risks may eventually find technological solutions for therapy bots, for example, app-enabled time limits reducing overreliance, and better training data to enhance accuracy and reduce inherent biases.

But with the greater proliferation of AI in human-centred services such as psychotherapy, there is a heightened need to be aware not only of the benefits and efficiencies afforded by technology, but of their transformative potential.

Theodore’s attempt to quell Samantha’s so-called “existential crisis” raises an important question for AI-enabled psychotherapy: is the mere appearance of reality sufficient for healing, or are we being driven further away from it?

BY Kristina Novakovic

Dr. Kristina Novakovic is an ethicist and Associate Researcher at RAND Australia. Her current areas of research include the ethics and governance of emerging technologies and issues in military ethics.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Explainer

Science + Technology

Thought experiment: “Chinese room” argument

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing

How to live a good life

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Send in the clowns: The ethics of comedy

Opinion + Analysis

Climate + Environment, Health + Wellbeing

Donation? More like dump nation

Making sense of our moral politics

Making sense of our moral politics

Opinion + AnalysisPolitics + Human RightsSociety + Culture

BY Tim Dean 17 JUN 2025

Want to understand politics better? Want to make sense of what the ‘other side’ is talking about? Then take a moment to reflect on your view of an ideal parent.

What kind of parent are you – either in reality or hypothetically? Do you want your children to build self-reliance, discipline, a strong work ethic and steel themselves to succeed in a dog-eat-dog world? Do you want them to respect their elders, which means acknowledging your authority, and expect them to be loyal to your family and community? Do you want them to learn to follow the rules, through punishment if necessary, knowing that too much coddling can leave them lazy or fragile?

Or do you want to nurture your children, so they feel cared for, cultivating a sense of empathy and mutual respect towards you and all other people? Do you want them to find fulfilment in their lives by exploring their world in a safe way, and discovering their place in it of their own accord, supported, but not directed, by you? Do you believe that strictness and inflexible rules can do more harm than good, so prefer to reward positive behaviour rather than threaten them with punishment?

Of course, few people will fall entirely into one category, but many people will feel a greater affinity with one of these visions over the other. This, according to American cognitive linguist, George Lakoff, is the basis of many of our political disagreements. This, he argues, is because many of us intuitively adopt a morally-laced metaphor of the government-as-family, with the state being the parents and the citizens the children, and we bring our preconceived notions of what a good family looks like and apply them to the government.

Lakoff argues that people who lean towards the first description of parenthood described above adopt a “Strict Father” metaphor of the family, and they tend to lean conservative or Right wing. Whereas people who lean towards the second metaphor adopt a “Nurturant Parent” metaphor of the family, and tend to lean more progressive or Left wing. And because these metaphors are so embedded in our understanding of the world, and so invisible to us, we don’t even realise that we see the world – and the role of government – in a very different light to many other people.

Strict Father

The Strict Father metaphor speaks to the importance of self-reliance, discipline and hard work, which is one reason why the Right often favours low taxation and low welfare spending. This is because taxation amounts to taking away your hard-earned money and giving it to someone who is lazy. Remember Joe Hockey’s famous “lifters and leaners” phrase?

The Right is also more wary of government regulation and protections – the so-called “nanny state” – because the Strict Father metaphor says we should take responsibility for our actions, and intervention by government bureaucrats robs us of our ability to make decisions for ourselves.

The Right is also more sceptical of environmental protections or action against climate change, because they subvert the natural order embedded in the Strict Father, which places humans above nature, and sees nature as a resource for us to exploit for our benefit. Climate action also looks to them like the government intervening in the market, preventing hard working mining and energy companies from giving us the resources and electricity we crave, and instead handing it over to environmentalists, who value trees more than people.

Implicit in the Strict Father view is the idea that the world is sometimes a dangerous place, that competition is inevitable, and there will be people who fail to cultivate the appropriate virtues of discipline and obedience to the rules. For this reason, the Right is less forgiving of crime, and often argues that those who commit serious crimes have demonstrated their moral weakness, and need to be held accountable. Thus it tends to favour more harsh punishments or locking them away, and writing them off, so they can’t cause any more harm.

Nurturant Parent

From the Nurturant Parent perspective, many of these Right-wing views are seen as either bizarre or perverse. The Nurturant Parent metaphor speaks to the need to care for others, stressing that everyone deserves a basic level of dignity and respect, irrespective of their circumstances.

It also acknowledges that success is not always about hard work, but often comes down to good fortune; there are many rich people who inherited their wealth and many hard working people who just scrape by, and many more who didn’t get the care and support they needed to flourish in life. For these reasons, the Left typically supports taxing the wealthy and redistributing that wealth via welfare programs, social housing, subsidised education and health care.

The Left also sees the government as having a responsibility to protect people from harm, such as through social programs that reduce crime, or regulations that prevent dodgy business practices or harmful products. Similarly, it believes that much crime is caused by disadvantage, but that people are inherently good if they’re given the right care and support. This is why it often supports things like rehabilitation programs or ‘harm minimisation,’ such as through drug injecting rooms, where drug users can be given the support they need to break their addiction rather than thrown in jail.

Implicit in the Nurturant Parent metaphor is that the world is generally a safe and beautiful place, and that we must respect and protect it. As such, the Left is more favourable towards environmental and climate policies, even if they mean that we might have to incur a cost ourselves, such as through higher prices.

Bridging the gap

Naturally, there’s a lot more to Lakoff’s theory than is described here, but the core point is that underneath our political views, there are deeper metaphors that unconsciously shape how we see the world.

Unless we understand our own moral worldview, including our assumptions about human nature, the family, the natural order or whether the world is an inherently fair place or not, then it’s difficult for us to understand the views of people on the other side of politics.

And, he argues, we should try to bridge that gap and engage with them constructively.

Part of Lakoff’s theory is that we absorb a metaphor of the family from our own experience, including our own upbringing and family life. That shapes how we make sense of things, like crime, the environment or even taxation policy. So we are already primed to be sympathetic towards some policies and sceptical of others. When we hear a politician speak, we intuitively pick up on their moral worldview, and find ourselves either agreeing or wondering how they could possibly say such outrageous things.

As such, we don’t start as entirely morally and political neutral beings, dispassionately and rationally assessing the various policies of different political parties. Rather, we’re primed to be responsive to one side more so than the other. As such, we don’t really choose whether to be Left or Right, we discover that we already are progressive or conservative, and then vote accordingly.

The difficulty comes when we engage in political conversation with people who hold a different metaphorical understanding of the world to our own. In these situations, we often talk across each other, debating the fairness of tax policy or expressing outrage at each others naivety around climate change, rather than digging deeper to reveal where the real point of difference occurs. And that point of difference could buried underneath multiple layers of metaphors or assumptions about the role of the government.

So, the next time you find yourself in a debate about tax policy, social housing, pill testing at music festivals or green energy, pause for a moment and perhaps ask a deeper question. Ask whether they think that success is due more to luck or hard work. Or ask whether the government has a responsibility to protect people from themselves. Or ask them which is more important: humanity or the rest of nature.

By pivoting to these deeper questions, you can start to reveal your respective moral worldviews, and see how they connect to your political views. You might not convince anyone to adopt your entrenched moral metaphors, but you might at least better understand why you each have the views you have – and you might not see political disagreement as a symptom of madness, and instead see it as a symptom of the inevitable variation in our understanding of the world. That won’t end your conversation, but it might start a new one that could prove very fruitful.

BY Tim Dean

Dr Tim Dean is a public philosopher, speaker and writer. He is Philosopher in Residence and Manos Chair in Ethics at The Ethics Centre.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

Where do ethics and politics meet?

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

He said, she said: Investigating the Christian Porter Case

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

It’s time to increase racial literacy within our organisations

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights, Society + Culture

Drawing a line on corruption: Operation eclipse submission

Lessons from Los Angeles: Ethics in a declining democracy

Lessons from Los Angeles: Ethics in a declining democracy

Opinion + AnalysisPolitics + Human Rights

BY Dr. Gwilym David Blunt 17 JUN 2025

The first two weeks of June 2025 have seen dramatic demonstrations in the United States against the Trump administration.

Against the backdrop of the President’s campaign of mass deportation, federal agents staged raids at a Home Depot and garment factories in Los Angeles. This triggered spontaneous and sometimes violent protests. Amidst television coverage giving the impression of widespread lawlessness, President Trump deployed some 4,000 members of the California National Guard and 700 U.S. marines – this was done despite the objections of Governor Gavin Newsom, LA Mayor Karen Bass, and the LA Police Department.

This is not unprecedented, but this was the first time troops were deployed on the streets of an American city since the 1992 LA Riots. It was also the first time since 1965 that the Guard was deployed over the objections of a state governor since Lydon Baines Johnson used them to protect citizens marching for civil rights in Alabama.

However, the context matters. These protests in LA in no way matched the scale of the LA Riots of forty years ago, which effectively shut down the city. In 2025 people were still travelling to work; Angelinos were posting photos of family fun from Disneyland. Secondly, Baines Johnson felt the necessity of nationalising the Guard in Alabama because of a widespread organised racist campaign of intimidation against civil rights activists. The was no comparable deprivation of rights in LA (possibly excepting the climate of fear created by Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) agents in the city’s Latino population).

The president has these powers, but they are expected to use them within the norms of ‘democratic restraint’ – they should only be used when there is great urgency. This was plainly not the case, considering the LA protests were effectively contained by the LAPD. Governor Newsom delivered a televised address in which he accused Trump of undermining the norms and institutions of democratic government in the United States and that California was being used to test a broader authoritarian power grab.

America is showing many of the signs of ‘democratic backsliding’. In How Democracies Die, political scientists at Harvard, Steven Levitsky and Daniel Ziblatt, have identified symptoms of a dying democracy. Many people think of military coups and tanks on the streets, but democracies often have slower, less spectacular deaths. Levitsky and Ziblatt show that elected leaders manage to neutralise and co-opt other branches of government; we have seen this with the collapse of moderate voices in the Republican Party and many express deep reservations about the Supreme Court’s independence after the genuinely shocking ruling for Trump v. United States which effectively placed the president above the law.

It is not just the institutional stress, but the growing incivility of civil society that is a concern, because institutions and constitutions do not defend themselves. They require people to unite to support common ways of life.

Americans are now deeply polarised. Political opponents are no longer competitors but enemies, or even traitors, to be silenced. It is impossible to disassociate this from the global pandemic of social media brain rot spreading disinformation, hatred, and conspiracy theories. The erosion of checks and balances coupled with the polarisation of civil society has enabled democratic norms to be slowly eroded to the extent that the President feels able to govern without traditional restraint.

So then what are the duties of citizens in a democracy that, if not dying, is looking terribly ill? This is not a partisan issue, but one that addresses the basic structure of society.

John Rawls wrote in A Theory of Justice, perhaps the greatest work of American political philosophy, that we all have a ‘natural duty’ to build and uphold just social institutions. This is because these institutions are the condition by which we can exercise our minimal autonomy. There is an assumption here that there is something intrinsically valuable about being able to think up and pursue one’s idea of a good life (so long as it doesn’t step on other people’s ability to do the same). You cannot do this if your choices are contingent on the will of a powerful person, whether it is your boss or the president. This is why the founders of the United States opted for a republic over a monarchy as the best guarantee of freedom from domination. It is a matter that should concern all Americans regardless of their political preferences.

Yet, it is a fragile system. On the last day of the Constitutional Convention in 1787, Benjamin Franklin was asked by his friend Elizabeth Willing Powel whether the United States was to be a monarchy or a republic, to which he replied, “a republic if you can keep it”. It is easy to imagine states, especially ones as powerful as the United States, as permanent, but history is a graveyard of states, including many democracies.

What then are citizens to do in circumstances where democracy is failing? We find a suggestion in Franklin’s words. It is up to the people. What makes Franklin’s quote so interesting is that he addressed it to someone who could not even vote: a republic if you can keep it. The suggestion being that all people, even the disenfranchised, share this natural duty to preserve and uphold just institutions. The addressee of Franklin in the 21st century could well be the illegal immigrants who despite being demonised are an integral part of the American economy and society. The protests in LA may have been alarming, but they were a distress call from some of the most vulnerable people in the United States.

The question is how long can this continue? The problem with socialism, Oscar Wilde quipped, is that it takes up too many evenings. The same can be said about resisting authoritarianism. People need to live their lives, you can’t spend every waking hour protesting. Authoritarians know this and take their time eroding the guardrails and poisoning civil society. Trump with characteristic impatience is trying to do in months what took Viktor Orban and Hugo Chavez years to accomplish in much weaker democracies. The experience of the past two weeks may have chastened Trump, but it won’t stop him. The citizens of the United States are in a race against autocracy, but it is not a sprint. It is a marathon.

What every person in the United States, both citizens and non-citizens, must ask themselves is how best can I exercise my natural duty to support just institutions when they are under threat? It is an imperfect duty, meaning that it can be cashed out in numerous ways, but here are 3 suggestions:

- Vote for democracy: In instances of authoritarian capture people must put country above party. When a mainstream party, either of the left or the right, is infected by authoritarianism it is time to find a new political home until the fever breaks.

- Depolarise your politics: Democracies die when people lose what philosopher Michael Oakeshott called a ‘common tongue’ – the shared practices and customs that turns strangers into compatriots. Just as some people must make a new political home, others have a duty to welcome them. Your neighbour is not your enemy, even when you disagree.

- Take it to the streets: Vocal and visible rejection of authoritarianism by a united front reminds people that the decline of democracy is not inevitable; think of the contrast between the aptly named “No Kings” protests and Trump’s farcically shabby birthday parade. Public defiance is essential to maintain the health of civil society.

And it should also be said all of us observing from the sidelines must ask ourselves how we can exercise the same duty to prevent our democracies from going the same way.

BY Dr. Gwilym David Blunt

Dr. Gwilym David Blunt is a Fellow of the Ethics Centre, Lecturer in International Relations at the University of Sydney, and Senior Research Fellow of the Centre for International Policy Studies. He has held appointments at the University of Cambridge and City, University of London. His research focuses on theories of justice, global inequality, and ethics in a non-ideal world.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

Big Thinker: John Rawls

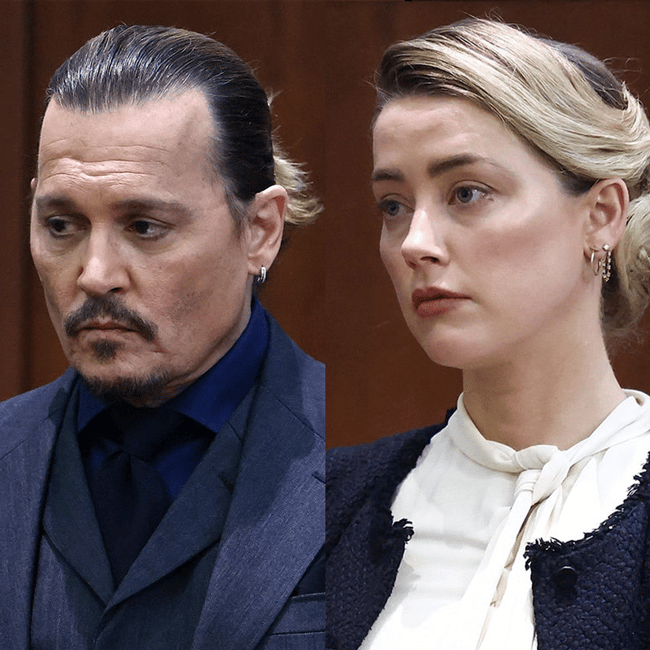

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships, Society + Culture

You won’t be able to tell whether Depp or Heard are lying by watching their faces

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

Ethics Explainer: Testimonial Injustice

Big thinker

Politics + Human Rights

Big Thinker: Ayaan Hirsi Ali

Ask an ethicist: How should I divvy up my estate in my will?

Ask an ethicist: How should I divvy up my estate in my will?

Opinion + AnalysisRelationships

BY Tim Dean 12 JUN 2025

I’m in the process of writing my will, but I’m unsure about how I should split my estate among my children. Should it be divided equally? Or should I give more to one of my children, who needs it more?

It’s hard enough avoiding thinking about our own mortality, but then we also have to contemplate the ructions that could erupt after we depart the mortal coil. Is that fair? Probably not. But at least you can attempt to be fair in how you dole out your mortal leftovers.

The good news is that philosophers have spent centuries coming up with ways to carve up a bundle of stuff – whether that’s a pie, a national budget or a deceased estate – and distribute it fairly. The bad news is they haven’t settled on just one right way to do it. Still, if you care about fairness, then there are a few approaches you can take.

The simplest is to just split things perfectly evenly. Say you have $100,000 left in the bank; you have four children: you divide it four ways, so they get $25,000 each. Simple. That’s called “strict egalitarianism,” which says that stuff should be distributed so that everyone ends up with exactly the same amount.

But my youngest child has had a string of bad luck that has left them struggling to get by. Meanwhile, the three older ones are cruising. Does that mean I should leave more to the needy one and less to the others?

And therein lies a problem with strict egalitarianism: we don’t all start off in the same position. So sharing stuff around equally might just exacerbate existing inequalities. Like, it would be weird to cut a pie four ways and give an equal slice to each diner if three of them were stuffed full and one was starving to death.

That’s why the “welfare approach” urges us to think carefully about how each individual is going right now, and make sure that we distribute our stuff so that it generates the maximum overall welfare for everyone. So, if three of your children are doing well – i.e. their welfare is currently high – and one is lagging behind, then it would be fair to give the one who’s struggling a bigger slice of the pie.

That doesn’t necessarily mean they should get all the pie. Things like money and pleasure often have diminishing returns. So giving everything you have to the struggling child might not elevate their welfare much more than just giving them half. And it might turn out that giving a small amount to the three children who are better off will still make a significant difference to their welfare. So get your calculator out, start plugging in welfare values, and run the numbers to see who gets what.

Look, I hear you, but my older kids say that my youngest is an idiot, and keeps making terrible decisions, like investing all their money in crypto. Would it be unfair to the others if I just propped them up?

Speaking of divvying up pies, this brings us to the idea of “dessert”. Fairness is not just about making sure that everyone ends up on even footing. It can also mean rewarding those who work hard and act responsibly, and not coddling those who are lazy and irresponsible. If you keep feeding that hungry person pie, then they might not bother making themselves dinner and rely on your charity to keep them fed.

So, the dessert-based approach says you should think about how much of your fortune each of your children deserves. You might look at how hard they work, or how much they contribute to looking after their families, or how much time and energy they have spent caring for you.

Well, if that’s the case, then none of them deserve it, because they all forgot to call me on my last birthday. That said, I do like the idea of making sure my inheritance goes where it can do the most good. I’m just not convinced that it can do so in the pockets of my ungrateful children.

Then perhaps you need to broaden your horizons beyond your family. Even a small donation to the right charity can transform lives, producing far better outcomes in terms of welfare than giving it you children, especially if they are already living comfortably.

In fact, it’s well known that inheritances are a major contributor to perpetuating intergenerational inequality. Rich people give their stuff to rich kids, who can use that to generate even more riches throughout their lifetime. I mean, have you seen the property market these days? It’s almost impossible to get in without an inheritance propping you up. So what do poorer people do?

That’s why economists say one of the best ways to flatten the wealth in a society is to tax inheritances, especially big ones. Although that policy is strangely unpopular with many voters, especially those who own multiple properties. Go figure.

So, if you decide to break the cycle and do the most good with your inheritance, there are plenty of charities that will more than happily distribute it to those with the greatest need. Just don’t expect your kids to be thrilled with your decision.

BY Tim Dean

Dr Tim Dean is a public philosopher, speaker and writer. He is Philosopher in Residence and Manos Chair in Ethics at The Ethics Centre.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships, Science + Technology, Society + Culture

Who does work make you? Severance and the etiquette of labour

Big thinker

Relationships

Big Thinker: David Hume

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Should you celebrate Christmas if you’re not religious?

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Blame

Arguments around “queerbaiting” show we have to believe in the private self again

Arguments around “queerbaiting” show we have to believe in the private self again

Opinion + AnalysisSociety + Culture

BY Joseph Earp 3 JUN 2025

Back in 2020, pop star Harry Styles caused a stir when he made the supposedly taboo move of appearing on the cover of Vogue magazine wearing a dress.

The stir was probably to be expected, sadly. Though such fashion choices used to go largely uncommented upon, sexuality and gender has become a hot topic issue, and any public suggestions of gender fluidity or queer sexuality tends to prompt hysteria from conservative commentators. But it wasn’t just this group who had something to say. Styles’ dress also prompted a wave of discourse amongst progressives around “queerbaiting”.

Like so many contemporary culture clashes, at the heart of these arguments lie questions about the self: how much of someone else’s identity are we entitled to?

Queerbaiting and the demand for the entire self

At its heart, queerbaiting is a term applied to a suspected marketing strategy. The claim is that some artists and public figures court the attention of queer and allied audiences by pretending to be queer – or at the very least, suggesting that they are – in order to increase their fanbase, general public standing, and sales.

But knowing whether a public figure is actually queerbaiting, or if they are indeed queer, requires demanding access to key aspects of their identity, that once upon a time, we might have been more okay with them keeping private. Queerbaiting thus normalises our desperate hunger for, and perpetuation of, gossip – but here, it casts feeding that desire for gossip as some kind of moral act.

The least harmful examples of these investigations into public figures’ identity markers are basically just online gossip. For example, discussions around the sexuality of actors like Hugh Jackman, or filmmakers like Baz Luhrmann, have existed for a long time. The most harmful examples resemble old-fashioned “outing”. For instance, just a few years ago, one of the key players of the TV show Heartstopper felt pressured into publicly revealing their sexuality to avoid accusations of queerbaiting. “I’m bi,” he wrote. “Congrats for forcing an 18-year-old to out himself. I think some of you missed the point of the show.”

The need for a private self

Discussions about queerbaiting have tricked us into believing that we are not just entitled to a celebrity’s personal life because we are snoops, but because we gain something morally through that demand.

While it might be a well-intentioned, certainly – we should be suspicious of the behaviour of the ultra-rich and public figures trying to gain more capital, particularly when it comes to the harnessing of marginalised identities – that suspicion does not undo the need for privacy.

The demand that people must “out” themselves has always been problematic – but now, in an increasingly dangerous international political climate, such as the Trump administration emboldening anti-LGBTQIA+ groups, it has become actively harmful. When we try to convince ourselves that the entitlement to someone’s sexuality or gender is “logical” or reasonable, we start sliding down a pretty slippery slope, at risk of ending up in a place where marginalised groups have no right to privacy, in a world that has the potential to become only more hostile.

More than that, queerbaiting enforces a categorised, inflexible and outdated understanding of gender and sexuality that progressives have done a lot of work to abandon. Demanding that someone label themselves, when they might not be ready to do so, or might not even have the personal language yet to decide what precise label that they would use, makes the spectrum of sexuality seem unnervingly rigid.

After all, experimenting with a fluid sexuality and gender can be, in some cases, a slow process. Forcing someone to label themselves, when they may just be at the beginning of that journey, goes against so much good work that progressives have done to create a freer culture. The worry is not, necessarily, that celebrities themselves are being harmed by queerbaiting – but that the direction of the public discourse will have a trickle down effect, one that will normalise non-ideal practices and behaviours.

It was the philosopher John Stuart Mill who most carefully laid out the importance of the “private sphere.” For Mill, every person should be entitled to thoughts, beliefs, and sometimes even actions, that were outside the remit of the state and others – that belonged only to them. Mill foresaw that trying to police such a private sphere was akin to a kind of intellectual fascism: as soon as we let go of our private selves, we make our whole selves controllable.

Importantly, Mill believed that actions and beliefs in the private sphere stopped being ungovernable when they harmed others – he did not think that we were just free to do whatever we liked, under the guise of our privacy. But he did believe that we were entitled to a self which was ours and ours alone.

We would do well to remind ourselves of Mill’s argument. Celebrities sign up to giving a great deal of themselves to the public eye – but that does not mean that they need to give all of it. Even a public figure is allowed a private self. And when we forget that, and we start demanding more and more, we normalise the harmful attitude that privacy is something that can be given up, rather than an inalienable right that we should all enjoy.

BY Joseph Earp

Joseph Earp is a poet, journalist and philosophy student. He is currently undertaking his PhD at the University of Sydney, studying the work of David Hume.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Big thinker

Society + Culture

Big Thinker: Philippa Foot

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

The problem with Australian identity

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships, Society + Culture

In the face of such generosity, how can racism still exist?

Explainer, READ

Society + Culture

Ethics Explainer: WEIRD ethics

Do we exaggerate the difference age makes?

Do we exaggerate the difference age makes?

Opinion + AnalysisSociety + CultureRelationships

BY Emma Wilkins 19 MAY 2025

A few weekends ago, I made a parenting mistake. I didn’t realise in the moment. The penny didn’t drop, until a good friend made a comment afterwards.

My family was hosting a brunch with several other families. After a few hours in the noisy, sticky, fray, one of our kids asked to retreat. Sensing my hesitation, he pointed out that none of the other guests were of his age.

Partly in acknowledgement, and partly because the retreat he had in mind involved attacking the thistles taking over our front lawn, I let him slip away.

Shortly afterwards, sitting with a group of parents, watching syrup-crazed children run riot out the back, I explained his absence. One parent stopped me at the words “no one my age”. He was wondering, aloud, why age was relevant – let alone a reason to retreat.

The friend who stopped me was one who’d moved to Australia as an adult. He saw the culture he was living in, and the one he’d left, with the benefit of fresh, discerning eyes. Before he finished making it, I saw his point.

Why not expect our kids to socialise with others, regardless of age? Why not encourage them to enjoy the company of those younger than them, and the company of those older than them?

The friend in question told us he’d noticed this propensity to segregate by age before, and resolved not to succumb. He said he makes a point of crossing age divides, of greeting and conversing without discriminating, at social gatherings. Children, in particular, often seem puzzled by his attention. Sometimes they don’t return a greeting, or answer a question, they just stare. The stare might be translated to mean, “Why is this old dude talking to me?” or, “Why would I talk to this old dude?”. Sometimes they mutter something before running off, sometimes they just run off.

As the friend spoke, I recalled a social event where the child who’d just retreated had ended up deep in conversation with a grandparent he’d never met. I wished this image had come to mind earlier, prompted by the words “no one my age”. I knew both he and that grandparent had enjoyed their conversation, maybe as much as the cake, maybe more. It was proof age needn’t be a barrier.

Age needn’t be a barrier, but my friend’s description of children giving him quizzical looks when he acknowledges them suggests us adults are making it one. It suggests so few adults – not counting relatives – take the time to talk to them, that when one does it’s an anomaly.

I consider how much attention I pay to children who aren’t my own at social gatherings.

Sometimes, my attention is on fellow grown-ups and I don’t think to make an effort. At other times, I think to – then I overthink. I see a child and a compliment comes to mind but it’s based on their appearance, or a stereotype, so I censor myself. Or a question comes to mind, but the child in question is a teen and I imagine it will either induce a deep inward groan – “Not another adult asking what I’ll do post-school, how should I know?” – or defensiveness, or self-consciousness, or insecurity…

What lame excuses! If I want my kids to enjoy and initiate interactions and relationships with people of all ages, to throw age-related bias out the window, I should too – even if it requires a little bit of extra effort, creativity, or risk. Who cares if I induce an eye-roll or a groan? What matters is that I don’t just take a genuine interest, and show genuine interest, in adult’s lives, but in the lives of children, too.

I’m sure political philosopher David Runciman also attracts plenty of eye-rolls, as he did at last year’s Festival of Dangerous Ideas, when arguing that children as young as six should be allowed to vote. After acknowledging that many people find the idea laughable, he turns the question around. “Why shouldn’t they vote?” he asks. “They’re people; they’re citizens; they have interests; they have preferences; there are things that they care about.” Children might make irrational, ill-informed decisions, they might follow their tribe unthinkingly, they might dismiss facts that challenge pre-existing beliefs, but, he points out, adults might too.

“You can’t generalise about children any more than you can generalise about adults,” Runciman says, noting that being well-informed isn’t a prerequisite for voting. Being capable is, and six-year-olds, he argues, are.

Runciman speaks from experience – he once spent a term in an English primary school talking to kids as young as six about politics. Treating them “like they were full citizens”, he arranged for them to participate in the kind of focus groups political parties run for adults. The professional facilitator who ran them said one was among the most inspiring focus group sessions she’d ever been part of.

I’m not convinced children as young as six should be allowed to vote; I am convinced that when we assume we can’t learn from, or socialise with, or befriend them – when we widen the generational divide instead of closing it – we do ourselves and our society a disservice.

I was grateful, and I’m grateful still, that the friend who drew my attention to my parenting mistake didn’t let concern about how it might come across stop him from speaking his mind. Frank honesty is a quality some associate with children. Either way, it’s one that I admire.

I admired his persistence too – despite all those puzzled looks from kids, he’s persevered.

That persistence has paid off. It’s taken months, it’s taken years, but now some children run to him, or look for him at social gatherings. Now some consider him a friend.

For more, tune into David Runciman’s FODI talk, Votes for 6 year olds:

BY Emma Wilkins

Emma Wilkins is a journalist and freelance writer with a particular interest in exploring meaning and value through the lenses of literature and life. You can find her at: https://emmahwilkins.com/

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

The Dark Side of Honour

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships

What makes a business honest and trustworthy?

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Is it wrong to care about Ukraine more than other wars?

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Breaking news: Why it’s OK to tune out of the news

How to tackle the ethical crisis in the arts

How to tackle the ethical crisis in the arts

Opinion + AnalysisSociety + CultureBusiness + Leadership

BY Tim Dean 19 MAY 2025

Arts organisations need to strengthen their ethical decision making and communication if they’re to avoid getting caught in controversy.

Which value should arts organisations prioritise? Artistic expression? Or the creation of safe and inclusive spaces, free from divisive issues and the possibility of offence? They often have to choose one because it’s impossible to prioritise both.

Yet, rightly or wrongly, arts organisations are facing demands that they promote both values, with some voices calling for them to prioritise safety at the expense of expression. The sheer impossibility of attempting to satisfy both values – or at least not failing in one of them and triggering a costly backlash – must be keeping the leaders of arts organisations across the country up at night.

There has always been an inherent tension between the values of artistic expression and safety (broadly defined), so there will inevitably be situations where maximising one will compromise the other. Push expression to the extreme and art can be dehumanising or promote hatred. Push safety to the fore and art would lose its power to challenge dominant narratives. This is why the arts have always had to balance the two, often leaning in favour of artistic expression, but with red lines that make things like bigotry or hate speech off-limits.

The challenge today is that we live in an increasingly fractious, polarised and volatile environment, where issues such as the conflict in Gaza are dividing communities and eroding trust and good faith. Where, in times past, onlookers might have treated an ambiguous artwork with charity, now they see endorsement of terror. Where an artist might once have been forgiven for making an off-hand remark in support of a humanitarian cause they believe in, they are now interpreted as promoting hate. This milieu has contributed to many voices – often powerful voices – calling to lower the bar for what is considered “unsafe” and, as a result, seeking to overly constrain expression.

How are arts organisations to continue to fulfil their mandate in such an environment? Given that the issues facing them are fundamentally ethical in nature, the answer comes in strengthening their ethical foundations. One way of doing that is formally adopting a clearly articulated set of values (what they think is good) and principles (the rules they adhere to) that become the sole standard for judgement when individuals make decisions on behalf of their organisation.

Couple that with robust processes for engaging in ethical decision making, and the organisation benefits from making better decisions – and avoiding hasty ones driven by panic or expedience – and is also better able to justify those decisions in the public sphere. There might still be some who criticise the decision, but even a cynic will be forced to acknowledge the consistency and integrity of the organisation.

Of course, arts organisations are not monolithic entities. Leaders and staff will inevitably vary in what they personally think is good and bad or right and wrong. And while individuals have a clear right to decide whether or not they will work with or support a particular organisation, no person can impose their own personal values and principles on those they work with. So, organisations need to have internal processes that allow this diversity to be acknowledged, while arriving at a single set of values and principles that can guide the organisation’s decisions.

And they need to do this without allowing “shadow values and principles” to subvert them. Many organisations have a lovely list of words pinned to the wall or splashed across the ‘About’ page on their website. But their internal culture promotes a different set of values by rewarding or punishing certain behaviours. As a result, it’s possible for an organisation to say it prioritises artistic expression but its actions show it values the patronage of wealthy supporters more, and it’s willing to compromise the former to satisfy the latter.

A truly ethical organisation will be self-aware enough to recognise shadow values and principles when they emerge, and a truly enlightened leadership will be able to redirect the culture towards promoting their stated values and principles.

All of this requires work. But it can be done. I have seen it first hand. I’ve worked with multiple arts organisations to help them better understand the values and principles that they wish to promote, and workshopped a range of scenarios to put its decision making processes to the test.

What would they do if an artist they’ve programmed posts something inflammatory on social media a week before they’re scheduled to perform? What if it was a controversial work from a decade ago? What are the red lines in terms of expression and what are they willing to defend? What would they do if a high-profile donor threatens to pull funding if they don’t deplatform an artist they object to? How should they treat an artist who uses the platform they’ve been given by the organisation to make a political comment unrelated to their work?

The organisations I’ve worked with have answers to these questions. The answers might not satisfy everyone, and they might involve compromises, but they are consistent with the values and principles that drive the organisation.

There may be no single correct answer to many of the ethical challenges that arts organisations face, but there are better and worse answers. Having a robust ethical framework and decision making processes won’t make arts organisations immune to controversy, but it will help them avoid much of it, and enable them to respond with integrity to whatever comes their way.

If you’re an individual or an organisation facing a difficult workplace decision, The Ethics Centre offers a range of free resources to support this process. We also offer bespoke workshops, consulting and leadership training for organisations of all sizes. Contact consulting@ethics.org.au to find out more.

BY Tim Dean

Dr Tim Dean is a public philosopher, speaker and writer. He is Philosopher in Residence and Manos Chair in Ethics at The Ethics Centre.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Science + Technology, Society + Culture

AI is not the real enemy of artists

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships

What makes a business honest and trustworthy?

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships, Society + Culture

In the face of such generosity, how can racism still exist?

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

How to build a successful culture

We need to step out of the shadows in order to navigate a complex world

We need to step out of the shadows in order to navigate a complex world

Opinion + AnalysisSociety + Culture

BY Simon Longstaff 14 MAY 2025

One of the most potent allegories ever to be developed by a philosopher is Plato’s allegory of ‘the cave’.

The story centres around a community of people who are bound, from head to toe, while facing a wall. For the entirety of their lives, nothing is to be seen other than two-dimensional shadows cast by whatever passes between their backs and the source of illumination (the sun or a raging fire). Knowing of no other way to see the world, the chained viewers believe that all of reality is represented by the shadows they perceive. Worse still, they have no concept of ‘shadows’ that might shake their conviction that what they see is ‘real’.

Then, one fateful day, a single individual manages to break their bonds. Free to roam, they encounter a three-dimensional world of colour. Then – only then – do they realise that their life has been defined by error; that the shadows that they once took to represent the whole of reality are nothing more than a simplistic rendering of something far more complex, compelling and beautiful. Inspired by this new understanding, the person returns to liberate others. At first, they are mocked, labelled a lunatic and accused of heresy. Eventually, enough people are freed from their shackles and learn to see.

I used to think it was obvious that everyone would jump at the opportunity to be liberated from ignorance. Most of my working life has been animated by Socrates’ great maxim that, “the unexamined life is not worth living”. After all, is it not the capacity to acknowledge – but also to transcend – our instincts and desires, that makes us human? Is it not obvious that a refusal to examine our lives and to make conscious choices, is actually a refusal to embrace the fullness of our humanity? And is it not the task of philosophy – especially ethics – to equip us so that we might better manage complexity once the chains of unthinking custom and practice are loosened?

As it happens, the ‘shadows’ are far more attractive than I had supposed. In a world of increasing complexity, I have been surprised to see an increasing number of people yearning for their chains in the hope that they might recover the simpler two-dimensional world that they have left behind. I see this in an urge to force what is inherently complex into a deceptively simple form. This is an escape back into a world of shadows – an easier path than that of learning how better to deal with complex reality.

The truth is that most of the important things in life are complex. The ‘messiness’ of the human condition comes from the fact that we have the capacity to make conscious (and conscientious) choices in circumstances of radical uncertainty.

Too often, the choice is not between ‘good’ and ‘bad’ or ‘right’ and ‘wrong’. Values and principles of equal weight can pull us in opposite directions. It is easy to become ‘stuck’, or to face the prospect that the ‘least bad’ alternative is your only viable choice.

Ethics can help us address this messy reality. Not the impossible, flawed ideal of ‘ethical perfection’ – but rather being equipped to live in the uncomfortable light of reality … in all its complexity. We need people to become ‘champions for the common good’. For without dedicated care and attention, our ethical foundations begin to erode.

Ours is a complex world. But when we embrace the ethical dimension of our lives; when we step into the light, nothing can overwhelm and everything becomes possible.

With your support, The Ethics Centre can continue to be the leading, independent advocate for bringing ethics to the centre of everyday life in Australia. Click here to make a tax deductible donation today.

BY Simon Longstaff

After studying law in Sydney and teaching in Tasmania, Simon pursued postgraduate studies in philosophy as a Member of Magdalene College, Cambridge. In 1991, Simon commenced his work as the first Executive Director of The Ethics Centre. In 2013, he was made an officer of the Order of Australia (AO) for “distinguished service to the community through the promotion of ethical standards in governance and business, to improving corporate responsibility, and to philosophy.”

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Society + Culture

Making sense of our moral politics

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights, Society + Culture

Drawing a line on corruption: Operation eclipse submission

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture

The art of appropriation

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture