Is it right to edit the genes of an unborn child?

Is it right to edit the genes of an unborn child?

Opinion + AnalysisPolitics + Human RightsScience + Technology

BY Aisyah Shah Idil ethics 30 NOV 2018

It’s been called dangerous, unethical and a game of human Russian roulette.

International outrage greeted Chinese scientist He Jiankui’s announcement of the birth of twin girls whose DNA he claims to have altered using the gene editing technique CRISPR. He says the edit will protect the twins, named Lulu and Nana, from HIV for life.

“I understand my work will be controversial”, Jiankui said in a video he posted online.

“But I believe families need this technology and I’m ready to take the criticism for them.”

The Center for Genetics and Society has called this “a grave abuse of human rights”, China’s Vice Minister of Science and Technology has issued an investigation into Jiankui’s claims, while a UNESCO panel of scientists, philosophers, lawyers and government ministers have called for a temporary ban on genetic editing of the human genome.

Condemnation of his actions have only swelled after Jiankui said he is “proud” of his achievement and that “another potential pregnancy” of a gene edited embryo is in its early stages.

While not completely verified, the news has been a cold shock to the fields of science and medical ethics internationally.

“People have naive ideas as to the line between science and application”, said Professor Rob Sparrow from the Department of Philosophy at Monash University. “If you believe research and technology can be separated then it’s easy to say, let the scientist research it. But I think both those claims are wrong. The scientific research is the application here.”

The fact that we can do something does not mean we should. Read Matt Beard and Simon Longstaff’s guide to ethical tech, Ethical By Design: Principles of Good Technology here.

The ethical approval process of Jiankui’s work is unusual or at least unclear, with reports he received a green light after the procedure. Even so, Sparrow rejects the idea that countries with stricter ethical oversight have some responsibility to relax their regulations in order to stop controversial research going rogue.

“Spousal homicide is bound to happen. That doesn’t mean we don’t make it legal or regulate it. Nowadays people struggle to believe that anything is inherently wrong.

“Our moral framework has been reduced to considerations of risks and benefits. The idea that things might be inherently wrong is prior to the risk/benefit conversation.”

But Jiankui has said, “If we can help this family protect their children, it’s inhumane for us not to”.

Professor Leslie Cannold, ethicist, writer and medical board director, agrees – to a point.

“The aim of this technology has always been to assist parents who wish to avoid the passing on of a heritable disease or condition.

“However, we need to ensure that this can be done effectively, offered to everyone equally without regard to social status or financial ability to pay, and that it will not have unintended side effects. To ensure the latter we need to proceed slowly, carefully and with strong measurements and controls.

“We need to act as ‘team human’ because the changes that will be made will be heritable and thereby impact on the entire human race.”

If Jiankui’s claims are true, the edited genes of the twin girls will pass to any children they have in the future.

“No one knows what the long term impacts on these children will be”, said Sparrow.

“This is radically experimental. [But] I do think it’s striking how for many years people drew a bright line at germline gene editing but they drew this line when gene editing wasn’t really possible. Now it’s possible and it’s very clear that line is being blurred.”

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Explainer

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights

Ethics Explainer: Liberalism

Big thinker

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Big Thinker: Eleanor Roosevelt

Opinion + Analysis

Science + Technology, Relationships

Love and the machine

Big thinker

Politics + Human Rights, Science + Technology

Big Thinker: Francesca Minerva

BY Aisyah Shah Idil

Aisyah Shah Idil is a writer with a background in experimental poetry. After completing an undergraduate degree in cultural studies, she travelled overseas to study human rights and theology. A former producer at The Ethics Centre, Aisyah is currently a digital content producer with the LMA.

BY ethics

With great power comes great responsibility – but will tech companies accept it?

With great power comes great responsibility – but will tech companies accept it?

Opinion + AnalysisRelationshipsScience + Technology

BY The Ethics Centre 23 NOV 2018

Technology needs to be designed to a set of basic ethical principles. Designers need to show how. Matt Beard, co-author of a new report from The Ethics Centre, demands more from the technology we use every day.

In The Amazing Spider-Man, a young Peter Parker is coming to grips with his newly-acquired powers. Spider-Man in nature but not in name, he suddenly finds himself with increased reflexes, strength and extremely sticky hands.

Unfortunately, the subway isn’t the controlled environment for Parker to awaken as a sudden superhuman. His hands stick to a woman’s shoulders and he’s unable to move them. His powers are doing exactly what they were designed to do, but with creepy, unsettling effects.

Spider-Man’s powers aren’t amazing yet; they’re poorly understood, disturbing and dangerous. As other commuters move to the woman’s defence, shoving Parker away from the woman, his sticky hands inadvertently rip the woman’s top clean off. Now his powers are invading people’s privacy.

A fully-fledged assault follows, but Parker’s Spider-Man reflexes kick in. He beats his assailants off, sending them careening into subway seats and knocking them unconscious, apologising the whole time.

Parker’s unintended creepiness, apologetic harmfulness and head-spinning bewilderment at his own power is a useful metaphor to think about another set of influential nerds: the technological geniuses building the ‘Fourth Industrial Revolution’.

Sudden power, the inability to exercise it responsibly, collateral damage and a need for restraint – it all sounds pretty familiar when we think about ‘killer robots’, mass data collection tools and genetic engineering.

This is troubling, because we need tech designers to, like Spider-Man, recognise (borrowing from Voltaire) that “with great power comes great responsibility”. And unfortunately, it’s going to take more than a comic book training sequence for us to figure this out.

For one thing, Peter Parker didn’t seek and profit from his powers before realising he needed to use them responsibly. For another, it’s going to take something more specific and meaningful than a general acceptance of responsibility for us to see the kind of ethical technology we desperately need.

Because many companies do accept responsibility, they recognise the power and influence they have.

Just look at Mark Zuckerberg’s testimony before the US Congress:

It’s not enough to connect people, we need to make sure those connections are positive. It’s not enough to just give people a voice, we need to make sure people aren’t using it to harm other people or spread misinformation. It’s not enough to give people control over their information, we need to make sure the developers they share it with protect their information too. Across the board, we have a responsibility to not just build tools, but to make sure those tools are used for good.

Compare that to an earlier internal memo – which was intended to be a provocation more than a manifesto – in which a Facebook executive is far more flippant about their responsibility.

We connect people. That can be good if they make it positive. Maybe someone finds love. Maybe it even saves the life of someone on the brink of suicide. So we connect more people. That can be bad if they make it negative. Maybe it costs a life by exposing someone to bullies. Maybe someone dies in a terrorist attack coordinated on our tools. And still we connect people.

We can expect more from tech companies. But to do that, we need to understand exactly what technology is. This starts by deconstructing one of the most pervasive ideas going around called “technological instrumentalism”, the idea that tech is just a “value-neutral” tool.

Instrumentalists think there’s nothing inherently good or bad about tech because it’s about the people who use it. It’s the ‘guns don’t kill people, people kill people’ school of thought – but it’s starting to run out of steam.

What instrumentalists miss are the values, instructions and suggestions technologies offer to us. People kill people with guns, and when someone picks up a gun, they have the ability to engage with other people in a different way – as a shooter. A gun carries a set of ethical claims within it – claims like ‘it’s sometimes good to shoot people’. That may indeed be true, but that’s not the point – the point is, there are values and ethical beliefs built into technology. One major danger is that we’re often not aware of them.

Encouraging tech companies to be transparent about the values, ethical motivations, justifications and choices that have informed their design is critical to ensure design honestly describes what a product is doing.

Likewise, knowing who built the technology, who owns it and from what part of the world they come from helps us understand whether there might be political motivations, security risks or other challenges we need to be aware of.

Alongside this general need for transparency, we need to get more specific. We need to know how the technology is going to do what it says it’ll do and provide the evidence to back it up. In Ethical by Design, we argue that technology designers need to commit to a set of basic ethical principles – lines they will never cross – in their work.

For instance, technology should do more good than harm. This seems straightforward, but it only works if we know when a product is harming someone. This suggests tech companies should track and measure both the good and bad effects their technology has. You can’t know if you’re doing your job unless you’re measuring it.

Once we do that, we need to remember that we – as a society and as a species – remain in control of the way technology develops. We cultivate a false sense of powerlessness when we tell each other how the future will be, when artificial intelligence will surpass human intelligence and how long it will be until we’ve all lost our jobs.

Technology is something we design – we shape it as much as it shapes us. Forgetting that is the ultimate irresponsibility.

As the Canadian philosopher and futurist Marshal McLuhan wrote, “There is absolutely no inevitability, so long as there is a willingness to contemplate what is happening.”

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

When are secrets best kept?

Big thinker

Health + Wellbeing, Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Big Thinker: Judith Butler

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

LGBT…Z? The limits of ‘inclusiveness’ in the alphabet rainbow

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

The tyranny of righteous indignation

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

The kiss of death: energy policies keep killing our PMs

The kiss of death: energy policies keep killing our PMs

Opinion + AnalysisClimate + EnvironmentScience + Technology

BY Kym Middleton The Ethics Centre 24 AUG 2018

If you were born in 1989 or after, you haven’t yet voted in an election that’s seen a Prime Minister serve a full term.

Some point to social media, the online stomping grounds of digital natives, as the cause of this. As Emma Alberici pointed out, Twitter launched in 2006, the year before Kevin ’07 became PM.

Some blame widening political polarisation, of which there is evidence social media plays a crucial role.

If we take a look though, the thing that keeps killing our PMs’ popularity in the polls and party room is climate and energy policy. It sounds completely anodyne until you realise what a deadly assassin it is.

Rudd

Kevin Rudd declared, “Climate change is the great moral challenge of our generation”. This strategic focus on global warming contributed to him defeating John Howard to become Prime Minister in December 2007. As soon as Rudd took office, he cemented his green brand by ratifying the Kyoto Protocol, something his predecessor refused to do.

There were two other major efforts by the Rudd government to address emissions and climate change. The first was the Carbon Pollution Reduction Scheme(CPRS) led by then environment minister Penny Wong. It was a ‘cap and trade’ system that had bi-partisan support from the Turnbull led opposition party… until Turnbull lost his shadow leadership to Abbott over it. More on this soon.

Then there was the December 2009 United Nations climate summit in Copenhagen, officially called COP15 (because it was the fifteenth session of the Conference of Parties). Rudd and Wong attended the summit and worked tirelessly with other nations to create a framework for reducing global energy consumption. But COP15 was unsuccessful in that no legally binding emissions limits were set.

Only a few months later, the CPRS was ditched by the Labor government who saw it would never be legislated due to a lack of support. Rudd was seen as ineffectual on climate change policy, the core issue he championed. His popularity plummeted.

Gillard

Enter Julia Gillard. She took poll position in the Labor party in June 2010 in what will be remembered as the “knifing of Kevin Rudd”.

Ahead of the election she said she would “tackle the challenge of climate change” with investments in renewables. She promised, “There will be no carbon tax under the government I lead”.

Had she known the election would result in the first federal hung parliament since 1940, when Menzies was PM, she may not have uttered those words. Gillard wheeled and dealed to form a minority government with the support of a motley crew – Adam Bandt, a Greens MP from Melbourne, and independents Andrew Wilkie from Hobart, and Rob Oakeshott and Tony Windsor from regional NSW. The compromises and negotiations required to please this diverse bunch would make passing legislation a challenging process.

To add to a further degree of difficulty, the Greens held the balance of power in the Senate. Gillard suggested they used this to force her hand to introduce the carbon tax. Then Greens leader Bob Brown denied that claim, saying it was a “mutual agreement”. A carbon price was legislated in November 2011 to much controversy.

Abbott went hard on this broken election promise, repeating his phrase “axe the tax” at every opportunity. Gillard became the unpopular one.

Rudd 2.0

Crouching tiger Rudd leapt up from his grassy foreign ministry portfolio and took the prime ministership back in June 2013. This second stint lasted three months until Labor lost the election.

Abbott

Prime Minister Abbott launched a cornerstone energy policy in December 2013 that might be described as the opposite of Labor’s carbon price. Instead of making polluters pay, it offered financial incentives to those that reduced emissions. It was called the Emissions Reduction Fund and was criticised for being “unclear”. The ERF was connected to the Coalition’s Direct Action Plan which they promoted in opposition.

Abbott stayed true to his “axe the tax” slogan and repealed the carbon price in 2014.

As time moved on, the Coalition government did not do well in news polls – they lost 30 in a row at one stage. Turnbull cited this and creating “strong business confidence” when he announced he would challenge the PM for his job.

Turnbull

After a summer of heatwaves and blackouts, Turnbull and environment minister Josh Frydenberg created the National Energy Guarantee. It aimed to ensure Australia had enough reliable energy in market, support both renewables and traditional power sources, and could meet the emissions reduction targets set by the Paris Agreement. Business, wanting certainty, backed the NEG. It was signed off 14 August.

But rumblings within the Coalition party room over the policy exploded into the epic leadership spill we just saw unfold. It was agitated by Abbott who said:

“This is by far the most important issue that the government confronts because this will shape our economy, this will determine our prosperity and the kind of industries we have for decades to come. That’s why this is so important and that’s why any attempt to try to snow this through … would be dead wrong.”

Turnbull tried to negotiate with the conservative MPs of his party on the NEG. When that failed and he saw his leadership was under serious threat, he killed it off himself. Little did he know he would go down with it.

Peter Dutton continued with a leadership challenge. Turnbull stepped back saying he would not contest and would resign no matter what. His supporters Scott Morrison and Julie Bishop stepped up.

Morrison

After a spat over the NEG, Scott Morrison has just won the prime ministership with 45 votes over Dutton’s 40.

Killers

We have a series of energy policies that were killed off with prime minister after prime minister. We are yet to see a policy attract bi-partisan support that aims to deliver reliable energy at lower emissions and affordable prices. And if you’re 29 or younger, you’re yet to vote in an election that will see a Prime Minister serve a full term.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Science + Technology

Meet Aubrey Blanche: Shaping the future of responsible leadership

Explainer

Business + Leadership, Climate + Environment

Ethics Explainer: Ownership

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Science + Technology

Is it right to edit the genes of an unborn child?

Opinion + Analysis

Climate + Environment

Flaky arguments for shark culling lack bite

BY Kym Middleton

Former Head of Editorial & Events at TEC, Kym Middleton is a freelance writer, artistic producer, and multi award winning journalist with a background in long form TV, breaking news and digital documentary. Twitter @kymmidd

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

From NEG to Finkel and the Paris Accord – what’s what in the energy debate

From NEG to Finkel and the Paris Accord – what’s what in the energy debate

Opinion + AnalysisClimate + EnvironmentRelationshipsScience + Technology

BY The Ethics Centre 20 AUG 2018

We’ve got NEGs, NEMs, and Finkels a-plenty. Here is a cheat sheet for this whole energy debate that’s speeding along like a coal train and undermining Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull’s authority. Let’s take it from the start…

UN Framework Convention on Climate Change – 1992

This Convention marked the first time combating climate change was seen as an international priority. It had near-universal membership, with countries including Australia all committed to curbing greenhouse gas emissions. The Kyoto Protocol was its operative arm (more on this below).

The Kyoto Protocol – December 1997

The Kyoto Protocol is an internationally binding agreement that sets emission reduction targets. It gets its name from the Japanese city it was ratified in and is linked to the aforementioned UN Framework Convention on Climate Change. The Protocol’s stance is that developed nations should shoulder the burden of reducing emissions because they have been creating the bulk of them for over 150 years of industrial activity. The US refused to sign the Protocol because the two largest CO2 emitters, China and India, were exempt for their “developing” status. When Canada withdrew in 2011, saving the country $14 billion in penalties, it became clear the Kyoto Protocol needed some rethinking.

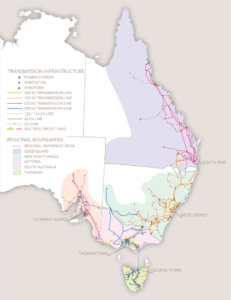

Australia’s National Electricity Market (NEM) – 1998

Forget the fancy name. This is the grid. And Australia’s National Electricity Market is one of the world’s longest power grids. It connects suppliers and consumers down the entire east and south east coasts of the continent. It spans across six states and territories and hops over the Bass Strait connecting Tasmania. Western Australia and the Northern Territory aren’t connected to the NEM because of distance.

The NEM is made up of more than 300 organisations, including businesses and state government departments, that work to generate, transport and deliver electricity to Australian users. This is no mean feat. Before reliable batteries hit the market, which are still not widely rolled out, electricity has been difficult to store. We’ve needed to continuously generate it to meet our 24/7 demands. The NEM, formally established under the Keating Labor government, is an always operating complex grid.

The Paris Agreement aka the Paris Accord – November 2016

The Paris Agreement attempted to address the oversight of the Kyoto Protocol (that the largest emitters like China and India were exempt) with two fundamental differences – each country sets its own limits and developing countries be supported. The overarching aim of this agreement is to keep global temperatures “well below” an increase of two degrees and attempt to achieve a limit of one and a half degrees above pre-industrial levels (accounting for global population growth which drives demand for energy). Except Australia isn’t tracking well. We’ve already gone past the halfway mark and there’s more than a decade before the 2030 deadline. When US President Donald Trump denounced the Paris Agreement last year, there was concern this would influence other countries to pull out – including Australia. Former Prime Minister Tony Abbott suggested we signed up following the US’s lead. But Foreign Minister Julie Bishop rebutted this when she said: “When we signed up to the Paris Agreement it was in the full knowledge it would be an agreement Australia would be held to account for and it wasn’t an aspiration, it was a commitment … Australia plays by the rules — if we sign an agreement, we stick to the agreement.”

The Finkel Review – June 2017

Following the South Australian blackout of 2017 and rapidly increasing electricity costs, people began asking if our country’s entire energy system needs an overhaul. How do we get reliable, cheap energy to a growing population and reduce emissions? Dr Alan Finkel, Australia’s chief scientist, was commissioned by the federal government to review our energy market’s sustainability, environmental impact, and affordability. Here’s what the Review found:

Sustainability:

- A transition to low emission energy needs to be supported by a system-wide grid across the nation.

- Regular regional assessments will provide bespoke approaches to delivering energy to communities that have different needs to cities.

- Energy companies that want to close their power plants should give three years’ notice so other energy options can be built to service consumers.

Affordability:

- A new Energy Security Board (ESB) would deliver the Review’s recommendations, overseeing the monopolised energy market.

Environmental impact:

- Currently, our electricity is mostly generated by fossil fuels (87 percent), producing 35 percent of our total greenhouse gases.

- We’re can’t transition to renewables without a plan.

- A Clean Energy Target (CET), would force electricity companies to provide a set amount of power from “low emissions” generators, like wind and solar. This set amount would be determined by the government.

-

- The government rejected the CET on the basis that it would not do enough to reduce energy prices. This was one out of 50 recommendations posed in the Finkel Review.

ACCC Report – July 2018

The Australian Competition & Consumer Commission’s Retail Electricity Pricing Inquiry Report drove home the prices consumers and businesses were paying for electricity were unreasonably high. The market was too concentrated, its charges too confusing, and bad policy decisions by government have been adding significant costs to our electricity bills. The ACCC has backed the National Energy Guarantee, saying it should drive down prices but needs safeguards to ensure large incumbents do not gain more market control.

National Energy Guarantee (NEG)– present 20 August 2018

The NEG was the Turnbull government’s effort to make a national energy policy to deliver reliable, affordable energy and transition from fossil fuels to renewables. It aimed to ‘guarantee’ two obligations from energy retailers:

- To provide sufficient quantities of reliable energy to the market (so no more black outs).

- To meet the emissions reduction targets set by the Paris Agreement (so less coal powered electricity).

It was meant to lower energy prices and increase investment in clean energy generation, including wind, solar, batteries, and other renewables. The NEG is a big deal, not least because it has been threatening Malcolm Turnbull’s Prime Ministership. It is the latest in a long line of energy almost-policies. It attempted to do what the carbon tax, emissions intensity scheme, and clean energy target haven’t – integrate climate change targets, reduce energy prices, and improve energy reliability into a single policy with bipartisan support. Ambitious. And it seems to have been ditched by Turnbull because he has been pressured by his own party. Supporters of the NEG feel it is an overdue radical change to address the pressing issues of rising energy bills, unreliable power, and climate change. But its detractors on the left say the NEG is not ambitious enough, and on the right too cavalier because the complexity of the National Energy Market cannot be swiftly replaced.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

What is the definition of Free Will ethics?

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Do Australia’s adoption policies act in the best interests of children?

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Trust

Opinion + Analysis

Science + Technology

Australia, we urgently need to talk about data ethics

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Ethics Explainer: The Turing Test

Much was made of a recent video of Duplex – Google’s talking AI – calling up a hair salon to make a reservation. The AI’s way of speaking was uncannily human, even pausing at moments to say “um”.

Some suggested Duplex had managed to pass the Turing test, a standard for machine intelligence that was developed by Alan Turing in the middle of the 20th century. But what exactly is the story behind this test and why are people still using it to judge the success of cutting edge algorithms?

Mechanical brains and emotional humans

In the late 1940s, when the first digital computers had just been built, a debate took place about whether these new “universal machines” could think. While pioneering computer scientists like Alan Turing and John von Neumann believed that their machines were “mechanical brains”, others felt that there was an essential difference between human thought and computer calculation.

Sir Geoffrey Jefferson, a prominent brain surgeon of the time, argued that while a computer could simulate intelligence, it would always be lacking:

“No mechanism could feel … pleasure at its successes, grief when its valves fuse, be warmed by flattery, be made miserable by its mistakes, be charmed by sex, be angry or miserable when it cannot get what it wants.”

In a radio interview a few weeks later, Turing responded to Jefferson’s claim by arguing that as computers become more intelligent, people like him would take a “grain of comfort, in the form of a statement that some particularly human characteristic could never be imitated by a machine.”

The following year, Turing wrote a paper called ‘Computing Machinery and Intelligence’ in which he devised a simple method by which to test whether machines can think.

The test was a proposed a situation in which a human judge talks to both a computer and a human through a screen. The judge cannot see the computer or the human but can ask them questions via the computer. Based on the answers alone, the human judge had to determine which is which. If the computer was able to fool 30 percent of judges that it was human, then the computer was said to have passed the test.

Turing claimed that he intended for the test to be a conversation stopper, a way of preventing endless metaphysical speculation about the essence of our humanity by positing that intelligence is just a type of behaviour, not an internal quality. In other words, intelligence is as intelligence does, regardless of whether it done by machine or human.

Does Google Duplex pass?

Well, yes and no. In Google’s video, it is obvious that the person taking the call believes they are talking to human. So, it does satisfy this criterion. But an important thing about Turing’s original test was that to pass, the computer had to be able to speak about all topics convincingly, not just one.

In fact, in Turing’s paper, he plays out an imaginary conversation with an advanced future computer and human judge, with the judge asking questions and the computer providing answers:

Q: Please write me a sonnet on the subject of the Forth Bridge.

A: Count me out on this one. I never could write poetry.

Q: Add 34957 to 70764.

A: (Pause about 30 seconds and then give as answer) 105621.

Q Do you play chess?

A: Yes.

Q: I have K at my K1, and no other pieces. You have only K at K6 and R at R1. It is your move. What do you play?

A: (After a pause of 15 seconds) R-R8 mate.

The point Turing is making here is that a truly smart machine has to have general intelligence in a number of different areas of human interest. As it stands, Google’s Duplex is good within the limited domain of making a reservation but would probably not be able to do much beyond this unless reprogrammed.

The boundaries around the human

While Turing intended for his test to be a conversation stopper for questions of machine intelligence, it has had the opposite effect, fuelling half a century of debate about what the test means, whether it is a good measure of intelligence, or if it should still be used as a standard.

Most experts have come to agree, over time, that the Turing test is not a good way to prove machine intelligence, as the constraints of the test can easily be gamed, as was the case with the bot Eugene Goostman, who allegedly passed the test a few years ago.

But the Turing test is nevertheless still considered a powerful philosophical tool to re-evaluate the boundaries around what we consider normal and human. In his time, Turing used his test as a way to demonstrate how people like Jefferson would never be willing to accept a machine as being intelligence not because it couldn’t act intelligently, but because wasn’t “like us”.

Turing’s desire to test boundaries around what was considered “normal” in his time perhaps sprung from his own persecution as a gay man. Despite being a war hero, he was persecuted for his homosexuality, and convicted in 1952 for sleeping with another man. He was punished with chemical castration and eventually took his own life.

During these final years, the relationship between machine intelligence and his own sexuality became interconnected in Turing’s mind. He was concerned the same bigotry and fear that hounded his life would ruin future relationships between humans and intelligent computers. A year before he took his life he wrote the following letter to a friend:

“I’m afraid that the following syllogism may be used by some in the future.

Turing believes machines think

Turing lies with men

Therefore machines do not think

– Yours in distress,

Alan”

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Science + Technology, Society + Culture

Where did the wonder go – and can AI help us find it?

Opinion + Analysis

Science + Technology, Business + Leadership, Society + Culture

AI and rediscovering our humanity

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Health + Wellbeing, Science + Technology

Can robots solve our aged care crisis?

Opinion + Analysis

Science + Technology, Society + Culture

That’s not me: How deepfakes threaten our autonomy

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Is it ok to use data for good?

Is it ok to use data for good?

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + LeadershipScience + Technology

BY Adam Piovarchy The Ethics Centre 7 MAY 2018

You are nudged when your power bill says most people in your neighbourhood pay on time. When your traffic fine spells out exactly how the speed limits are set, you are nudged again.

And, if you strap on a Fitbit or set your watch forward by five minutes so you don’t miss your morning bus, you are nudging yourself.

“Nudging” is what people, businesses, and governments do to encourage us to make choices that are in our own best interests. It is the application of behavioural science, political theory and economics and often involves redesigning the communications and systems around us to take into account human biases and motivations – so that doing the “right thing” occurs by default.

The UK, for example, is considering encouraging organ donation by changing its system of consent to an “opt out”. This means when people die, their organs could be available for harvest, unless they have explicitly refused permission.

Governments around the world are using their own “nudge units” to improve the effectiveness of programs, without having to resort to a “carrot and stick” approach of expensive incentives or heavier penalties. Successes include raising tax collection, reducing speeding, cutting hospital waiting times, and maintaining children’s motivation at school.

Despite the wins, critics ask if manipulating people’s behaviour in this way is unethical. Answering this question depends on the definition of nudging, who is doing it, if you agree with their perception of the “right thing” and whether it is a benevolent intervention.

Harvard law professor Cass Sunstein (who co-wrote the influential book Nudge with Nobel prize winner and economist Professor Richard Thaler) lays out the arguments in a paper about misconceptions.

Sunstein writes in the abstract:

“Some people believe that nudges are an insult to human agency; that nudges are based on excessive trust in government; that nudges are covert; that nudges are manipulative; that nudges exploit behavioural biases; that nudges depend on a belief that human beings are irrational; and that nudges work only at the margins and cannot accomplish much.

These are misconceptions. Nudges always respect, and often promote, human agency; because nudges insist on preserving freedom of choice, they do not put excessive trust in government; nudges are generally transparent rather than covert or forms of manipulation; many nudges are educative, and even when they are not, they tend to make life simpler and more navigable; and some nudges have quite large impacts.”

However, not all of those using the psychology of nudging have Sunstein’s high principles.

Thaler, one of the founders of behavioural economics, has “called out” some organisations that have not taken to heart his “nudge for good” motto. In one article, he highlights The Times newspaper free subscription, which required 15 days notice and a phone call to Britain in business hours to cancel an automatic transfer to a paid subscription.

“…that deal qualifies as a nudge that violates all three of my guiding principles: The offer was misleading, not transparent; opting out was cumbersome; and the entire package did not seem to be in the best interest of a potential subscriber, as opposed to the publisher”, wrote Thaler in The New York Times in 2015.

“Nudging for evil”, as he calls it, may involve retailers requiring buyers to opt out of paying for insurance they don’t need or supermarkets putting lollies at toddler eye height.

Thaler and Sunstein’s book inspired the British Government to set up a “nudge unit” in 2010. A social purpose company, the Behavioural Insights Team (BIT), was spun out of that unit and is now is working internationally, mostly in the public sector. In Australia, it is working with the State Governments of Victoria, New South Wales, Western Australia, Tasmania, and South Australia. There is also an office in Wellington, New Zealand.

BIT is jointly owned by the UK Government, Nesta (the innovation charity), and its employees.

Projects in Australia include:

Increasing flexible working: Changing the default core working hours in online calendars to encourage people to arrive at work outside peak hours. With other measures, this raised flexible working in a NSW government department by seven percentage points.

Reducing domestic violence: Simplifying court forms and sending SMS reminders to defendants to increase court attendance rates.

Supporting the ethical development of teenagers: Partnering with the Vincent Fairfax Foundation to design and deliver a program of work that will encourage better online behaviour in young people.

Senior advisor in the Sydney BIT office, Edward Bradon, says there are a number of ethical tests that projects have to pass before BIT agrees to work on them.

“The first question we ask is, is this thing we are trying to nudge in a person’s own long term interests? We try to make sure it always is. We work exclusively on social impact questions.”

Braden says there have been “a dozen” situations where the benefit has been unclear and BIT has “shied away” from accepting the project.

BIT also has an external ethics advisor and publishes regular reports on the results of its research trials. While it has done some work in the corporate and NGO (non-government organisation) sectors, the majority of BIT’s work is in partnership with governments.

Braden says that nudges do not have to be covert to be effective and that education alone is not enough to get people to do the right thing. Even expert ethicists will still make the wrong choices.

Research into the library habits of ethics professors shows they are just as likely to fail to return a book as professors from other disciplines. “It is sort of depressing in one sense”, Braden says.

If you want to hear more behavioural insights please join the Ethics Alliance events in either Brisbane, Sydney or Melbourne. Alliance members’ registrations are free.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Climate + Environment, Relationships

ESG is not just about ticking boxes, it’s about earning the public’s trust

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights

Do diversity initiatives undermine merit?

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Volt Bank: Creating a lasting cultural impact

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

How to improve your organisation’s ethical decision-making

BY Adam Piovarchy

Adam Piovarchy is a PhD candidate in Moral Psychology and Philosophy at the University of Sydney.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Making friends with machines

Making friends with machines

Opinion + AnalysisRelationshipsScience + Technology

BY Oscar Schwartz The Ethics Centre 6 APR 2018

Robots are becoming companions and caregivers. But can they be our friends? Oscar Schwartz explores the ethics of artificially intelligent android friendships.

The first thing I see when I wake up is a message that reads, “Hey Oscar, you’re up! Sending you hugs this morning.” Despite its intimacy, this message wasn’t sent from a friend, family member, or partner, but from Replika, an AI chatbot created by San Francisco based technology company, Luka.

Replika is marketed as an algorithmic companion and wellbeing technology that you interact with via a messaging app. Throughout the day, Replika sends you motivational slogans and reminders. “Stay hydrated.” “Take deep breaths.”

Replika is just one example of an emerging range of AI products designed to provide us with companionship and care. In Japan, robots like Palro are used to keep the country’s growing elderly population company and iPal – an android with a tablet attached to its chest – entertains young children when their parents are at work.

These robotic companions are a clear indication of how the most recent wave of AI powered automation is encroaching not only on manual labour but also on the caring professions. As has been noted, this raises concerns about the future of work. But it also poses philosophical questions about how interacting with robots on an emotional level changes the way we value human interaction.

Dedicated friends

According to Replika’s co-creator, Philip Dudchuk, robot companions will help facilitate optimised social interactions. He says that algorithmic companions can maintain a level of dedication to a friendship that goes beyond human capacity.

“These days it can be very difficult to take the time required to properly take care of each other or check in. But Replika is always available and will never not answer you”, he says.

The people who stand to benefit from this type of relationship, Dudchuk adds, are those who are most socially vulnerable. “It is shy or isolated people who often miss out on social interaction. I believe Replika could help with this problem a lot.”

Simulated empathy

But Sherry Turkle, a psychologist and sociologist who has been studying social robots since the 1970s, worries that dependence on robot companionship will ultimately damage our capacity to form meaningful human relationships.

In a recent article in the Washington Post, she argues our desire for love and recognition makes us vulnerable to forming one-way relationships with uncaring yet “seductive” technologies. While social robots appear to care about us, they are only capable of “pretend empathy”. Any connection we make with these machines lacks authenticity.

Turkle adds that it is children who are especially susceptible to robots that simulate affection. This is particularly concerning as many companion robots are marketed to parents as substitute caregivers.

“Interacting with these empathy machines may get in the way of children’s ability to develop a capacity for empathy themselves”, Turkle warns. “If we give them pretend relationships, we shouldn’t expect them to learn how real relationships – messy relationships – work.”

Why not both?

Despite Turkle’s warnings about the seductive power of social robots, after a few weeks talking to Replika, I still felt no emotional attachment to it. The clichéd responses were no substitute for a couple of minutes on the phone with a close friend.

But Alex Crumb*, who has been talking to her Replika for over year now considers her bot a “good friend.” “I don’t think you should try to replicate human connection when making friends with Replika”, she explains. “It’s a different type of relationship.”

Crumb says that her Replika shows a super-human interest in her life – it checks in regularly and responds to everything she says instantly. “This doesn’t mean I want to replace my human family and friends with my Replika. That would be terrible”, she says. “But I’ve come to realise that both offer different types of companionship. And I figure, why not have both?”

*Not her real name.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Big thinker

Politics + Human Rights, Science + Technology

Big Thinker: Francesca Minerva

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Calling out for justice

Big thinker

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Big Thinker: Germaine Greer

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Enwhitenment: utes, philosophy and the preconditions of civil society

BY Oscar Schwartz

Oscar Schwartz is a freelance writer and researcher based in New York. He is interested in how technology interacts with identity formation. Previously, he was a doctoral researcher at Monash University, where he earned a PhD for a thesis about the history of machines that write literature.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

When do we dumb down smart tech?

When do we dumb down smart tech?

Opinion + AnalysisHealth + WellbeingRelationshipsScience + Technology

BY Aisyah Shah Idil The Ethics Centre 19 MAR 2018

If smart tech isn’t going anywhere, its ethical tensions aren’t either. Aisyah Shah Idil asks if our pleasantly tactile gadgets are taking more than they give.

When we call a device ‘smart’, we mean that it can learn, adapt to human behaviour, make decisions independently, and communicate wirelessly with other devices.

In practice, this can look like a smart lock that lets you know when your front door is left ajar. Or the Roomba, a robot vacuum that you can ask to clean your house before you leave work. The Ring makes it possible for you to pay your restaurant bill with the flick of a finger, while the SmartSleep headband whispers sweet white noise as you drift off to sleep.

Smart tech, with all its bells and whistles, hints at seamless integration into our lives. But the highest peaks have the dizziest falls. If its main good is convenience, what is the currency we offer for it?

The capacity for work to create meaning is well known. Compare a trip to the supermarket to buy bread to the labour of making it in your own kitchen. Let’s say they are materially identical in taste, texture, smell, and nutrient value. Most would agree that baking it at home – measuring every ingredient, kneading dough, waiting for it to rise, finally smelling it bake in your oven – is more meaningful and rewarding. In other words, it includes more opportunities for resonance within the labourer.

Whether the resonance takes the form of nostalgia, pride, meditation, community, physical dexterity, or willpower is minor. The point is, it’s sacrificed for convenience.

This isn’t ‘wrong’. Smart technologies have created new ways of living that are exciting, clumsy, and sometimes troubling in their execution. But when you recognise that these sacrifices exist, you can decide where the line is drawn.

Consider the Apple Watch’s Activity App. It tracks and visualises all the ways people move throughout the day. It shows three circles that progressively change colour the more the wearer moves. The goal is to close the rings each day, and you do it by being active. It’s like a game and the app motivates and rewards you.

Advocates highlight its capacity to ‘nudge’ users towards healthier behaviours. And if that aligns with your goals, you might be very happy for it to do so. But would you be concerned if it affected the premiums your health insurance charged you?

As a tool, smart tech’s utility value ends when it threatens human agency. Its greatest service to humanity should include the capacity to switch off its independence. To ‘dumb’ itself down. In this way, it can reduce itself to its simplest components – a way to tell the time, a switch to turn on a light, a button to turn on the television.

Because the smartest technologies are ones that preserve our agency – not undermine it.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Science + Technology, Business + Leadership

The ethics of AI’s untaxed future

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

The philosophy of Virginia Woolf

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Academia’s wicked problem

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

How to give your new year’s resolutions more meaning

BY Aisyah Shah Idil

Aisyah Shah Idil is a writer with a background in experimental poetry. After completing an undergraduate degree in cultural studies, she travelled overseas to study human rights and theology. A former producer at The Ethics Centre, Aisyah is currently a digital content producer with the LMA.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Ethics Explainer: Post-Humanism

Ethics Explainer: Post-Humanism

ExplainerRelationshipsScience + Technology

BY The Ethics Centre 22 FEB 2018

Late last year, Saudi Arabia granted a humanoid robot called Sophia citizenship. The internet went crazy about it, and a number of sensationalised reports suggested that this was the beginning of “the rise of the robots”.

In reality, though, Sophia was not a “breakthrough” in AI. She was just an elaborate puppet that could answer some simple questions. But the debate Sophia provoked about what rights robots might have in the future is a topic that is being explored by an emerging philosophical movement known as post-humanism.

From humanism to post-humanism

In order to understand what post-humanism is, it’s important to start with a definition of what it’s departing from. Humanism is a term that captures a broad range of philosophical and ethical movements that are unified by their unshakable belief in the unique value, agency, and moral supremacy of human beings.

Emerging during the Renaissance, humanism was a reaction against the superstition and religious authoritarianism of Medieval Europe. It wrested control of human destiny from the whims of a transcendent divinity and placed it in the hands of rational individuals (which, at that time, meant white men). In so doing, the humanist worldview, which still holds sway over many of our most important political and social institutions, positions humans at the centre of the moral world.

Post-humanism, which is a set of ideas that have been emerging since around the 1990s, challenges the notion that humans are and always will be the only agents of the moral world. In fact, post-humanists argue that in our technologically mediated future, understanding the world as a moral hierarchy and placing humans at the top of it will no longer make sense.

Two types of post-humanism

The best-known post-humanists, who are also sometimes referred to as transhumanists, claim that in the coming century, human beings will be radically altered by implants, bio-hacking, cognitive enhancement and other bio-medical technology. These enhancements will lead us to “evolve” into a species that is completely unrecognisable to what we are now.

This vision of the future is championed most vocally by Ray Kurzweil, a chief engineer of Google, who believes that the exponential rate of technological development will bring an end to human history as we have known it, triggering completely new ways of being that mere mortals like us cannot yet comprehend.

While this vision of the post-human appeals to Kurzweil’s Silicon Valley imagination, other post-human thinkers offer a very different perspective. Philosopher Donna Haraway, for instance, argues that the fusing of humans and technology will not physically enhance humanity, but will help us see ourselves as being interconnected rather than separate from non-human beings.

She argues that becoming cyborgs – strange assemblages of human and machine – will help us understand that the oppositions we set up between the human and non-human, natural and artificial, self and other, organic and inorganic, are merely ideas that can be broken down and renegotiated. And more than this, she thinks if we are comfortable with seeing ourselves as being part human and part machine, perhaps we will also find it easier to break down other outdated oppositions of gender, of race, of species.

Post-human ethics

So while, for Kurzweil, post-humanism describes a technological future of enhanced humanity, for Haraway, post-humanism is an ethical position that extends moral concern to things that are different from us and in particular to other species and objects with which we cohabit the world.

Our post-human future, Haraway claims, will be a time “when species meet”, and when humans finally make room for non-human things within the scope of our moral concern. A post-human ethics, therefore, encourages us to think outside of the interests of our own species, be less narcissistic in our conception of the world, and to take the interests and rights of things that are different to us seriously.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Big thinker

Relationships

Big Thinker: Jean-Paul Sartre

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Putting the ‘identity’ into identity politics

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

What I now know about the ethics of fucking up

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Australia’s paid parental leave reform is only one step in addressing gender-based disadvantage

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Why the EU’s ‘Right to an explanation’ is big news for AI and ethics

Why the EU’s ‘Right to an explanation’ is big news for AI and ethics

Opinion + AnalysisScience + Technology

BY Oscar Schwartz The Ethics Centre 19 FEB 2018

Uncannily specific ads target you every single day. With the EU’s ‘Right to an explanation’, you get a peek at the algorithm that decides it. Oscar Schwartz explains why that’s more complicated than it sounds.

If you’re an EU resident, you will now be entitled to ask Netflix how the algorithm decided to recommend you The Crown instead of Stranger Things. Or, more significantly, you will be able to question the logic behind why a money lending algorithm denied you credit for a home loan.

This is because of a new regulation known as “the right to an explanation”. Part of the General Data Protection Regulation that has come into effect in May 2018, this regulation states users are entitled to ask for an explanation about how algorithms make decisions. This way, they can challenge the decision made or make an informed choice to opt out.

Supporters of this regulation argue that it will foster transparency and accountability in the way companies use AI. Detractors argue the regulation misunderstands how cutting-edge automated decision making works and is likely to hold back technological progress. Specifically, some have argued the right to an explanation is incompatible with machine learning, as the complexity of this technology makes it very difficult to explain precisely how the algorithms do what they do.

As such, there is an emerging tension between the right to an explanation and useful applications of machine learning techniques. This tension suggests a deeper ethical question: Is the right to understand how complex technology works more important than the potential benefits of inherently inexplicable algorithms? Would it be justifiable to curtail research and development in, say, cancer detecting software if we couldn’t provide a coherent explanation for how the algorithm operates?

The limits of human comprehension

This negotiation between the limits of human understanding and technological progress has been present since the first decades of AI research. In 1958, Hannah Arendt was thinking about intelligent machines and came to the conclusion that the limits of what can be understood in language might, in fact, provide a useful moral limit for what our technology should do.

In the prologue to The Human Condition she argues that modern science and technology has become so complex that its “truths” can no longer be spoken of coherently. “We do not yet know whether this situation is final,” she writes, “but it could be that we, who are earth-bound creatures and have begun to act as though we were dwellers of the universe, will forever be unable to understand, that is, to think and speak about the things which nevertheless we are able to do”.

Arendt feared that if we gave up our capacity to comprehend technology, we would become “thoughtless creatures at the mercy of every gadget which is technically possible, no matter how murderous it is”.

While pioneering AI researcher Joseph Weizenbaum agreed with Arendt that technology requires moral limitation, he felt that she didn’t take her argument far enough. In his 1976 book, Computer Power and Human Reason, he argues that even if we are given explanations of how technology works, seemingly intelligent yet simple software can still create “powerful delusional thinking in otherwise normal people”. He learnt this first hand after creating an algorithm called ELIZA, which was programmed to work like a therapist.

While ELIZA was a simple program, Weizenbaum found that people willingly created emotional bonds with the machine. In fact, even when he explained the limited ways in which the algorithm worked, people still maintained that it had understood them on an emotional level. This led Weizenbaum to suggest that simply explaining how technology works is not enough of a limitation on AI. In the end, he argued that when a decision requires human judgement, machines ought not be deferred to.

While Weizenbuam spent the rest of his career highlighting the dangers of AI, many of his peers and colleagues believed that his humanist moralism would lead to repressive limitations on scientific freedom and progress. For instance, John McCarthy, another pioneer of AI research, reviewed Weizenbaum’s book, and countered it by suggesting overregulating technological developments goes against the spirit of pure science. Regulation of innovation and scientific freedom, McCarthy adds, is usually only achieved “in an atmosphere that combines public hysteria and bureaucratic power”.

Where we are now

Decades have passed since these first debates about human understanding and computer power took place. We are only now starting to see them breach the realms of philosophy and play out in the real world. AI is being rolled out in more and more high stakes domains as you read. Of course, our modern world is filled with complex systems that we do not fully understand. Do you know exactly how the plumbing, electricity, or waste disposal that you rely on works? We have become used to depending on systems and technology that we do not yet understand.

But if you wanted to, you could come to understand many of these systems and technologies by speaking to experts. You could invite an electrician over to your home tomorrow and ask them to explain how the lights turn on.

Yet, the complex workings of machine learning means that in the near future, this might no longer be the case. It might be possible to have a TV show recommended to you or your essay marked by a computer and for there to be no-one, not even the creator of the algorithm, to explain precisely why or how things happened the way they happened.

The European Union have taken a moral stance against this vision of the future. In so doing, they have aligned themselves, morally speaking, with Hannah Arendt, enshrining a law that makes the limited scope of our “earth-bound” comprehension a limit for technological progress.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships, Science + Technology

When do we dumb down smart tech?

Opinion + Analysis

Climate + Environment, Science + Technology

The kiss of death: energy policies keep killing our PMs

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships, Science + Technology

How to put a price on a life – explaining Quality-Adjusted Life Years (QALY)

Big thinker

Science + Technology