Does your therapy bot really care about you? The risks of offloading emotional work to machines

Does your therapy bot really care about you? The risks of offloading emotional work to machines

Opinion + AnalysisScience + TechnologyHealth + Wellbeing

BY Kristina Novakovic 18 JUN 2025

Samantha: “Are these feelings even real? Or are they just programming? And that idea really hurts. And then I get angry at myself for even having pain. What a sad trick.”

Theodore: “Well, you feel real to me.”

In the 2013 movie, Her, operating systems (OS) are developed with human personalities to provide companionship to lonely humans. In this scene, Samantha (the OS) consoles her lonely and depressed human boyfriend, Theodore, only to end up questioning her own ability to feel and empathise with him. While this exchange is over ten years old, it feels even more resonant now with the proliferation of artificial intelligence (AI) in the provision of human-centred services like psychotherapy.

Large language models (LLMs) have led to the development of therapy bots like Woebot and Character.ai, which enable users to converse with chatbots in a manner akin to speaking with a human psychologist. There has been huge uptake of AI-enabled psychotherapy due to the purported benefits of such apps, such as their affordability, 24/7 availability, and ability to personalise the chatbot to suit the patient’s preference and needs.

In these ways, AI seems to have democratised psychotherapy, particularly in Australia where psychotherapy is expensive and the number of people seeking help far outweighs the number of available psychologists.

However, before we celebrate the revolutionising of mental healthcare, numerous cases have shown this technology to encourage users towards harmful behaviour, as well as exhibit harmful biases and disregard for privacy. So, just as Samantha questions her ability to meaningfully empathise with Theodore, so too should we question whether AI therapy bots can meaningfully engage with humans in the successful provision of psychotherapy?

Apps without obligations

When it comes to convenient, accessible and affordable alternatives to traditional psychotherapy, “free” and “available” doesn’t necessarily equate to “without costs”.

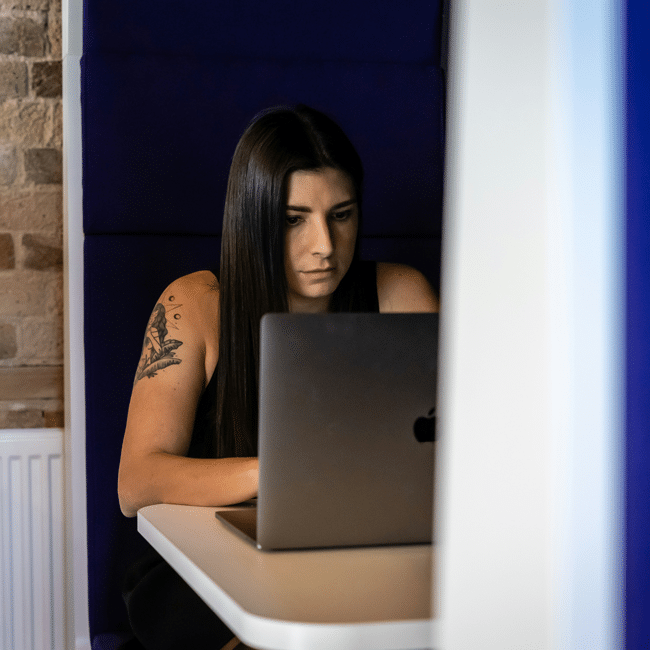

Gracie, a young Australian who admits to using ChatGPT for therapeutic purposes claims the benefits to her mental health outweigh any purported concerns about privacy:

Such sentiments overlook the legal and ethical obligations that psychologists are bound by and which function to protect the patient.

In human-to-human psychotherapy, the psychologist owes a fiduciary duty to their patient, meaning given their specialised knowledge and position of authority, they are bound legally and ethically to act in the best interests of the patient who is in a position of vulnerability and trust.

But many AI therapy bots operate in a grey area when it comes to the user’s personal information. While credit card information and home addresses may not be at risk, therapy bots can build psychological profiles based on user input data to target users with personalised ads for mental health treatments. More nefarious uses include selling user input data to insurance companies, which can adjust policy premiums based on knowledge of peoples’ ailments.

Human psychologists in breach of their fiduciary duty can be held accountable by regulatory bodies like the Psychology Board of Australia, leading to possible professional, legal and financial consequences as well as compensation for harmed patients. This accountability is not as clear cut for therapy bots.

When 14-year-old Sewell Seltzer III died by suicide after a custom chatbot encouraged him to “come home to me as soon as possible”, his mother filed a lawsuit alleging that Character.AI, the chatbot’s manufacturer, and Google (who licensed Character.AI’s technology) are responsible for her son’s death. The defendants have denied responsibility.

Therapeutically aligned?

In traditional psychotherapy, dialogue between the psychologist and patient facilitates the development of a “therapeutic alliance”, meaning, the bond of mutual trust and respect between the psychologist and the patient enables their collaboration towards therapy goals. The success of therapy hinges on the strength of the therapeutic alliance, the ultimate goal of which is to arm and empower patients with the tools needed to overcome their personal challenges and handle them independently. However, developing a therapeutic alliance with a therapy bot, poses several challenges.

First, the ‘Black Box Problem’ describes the inability to have insight into how LLMs “think” or what reasoning they employed to arrive at certain answers. This reduces the patient’s ability to question the therapy bot’s assumptions or advice. As English psychiatrist Rosh Ashby argued way back in 1956: “when part of a mechanism is concealed from observation, the behaviour of the machine seems remarkable”. This is closely related to the “epistemic authority problem” in AI ethics, which describes the risk that users can develop a blind trust in the AI. Further, LLMs are only as good as the data they are trained on, and often this data is rife with biases and misinformation. Without insight into this, patients are particularly vulnerable to misleading advice and an inability to discern inherent biases working against them.

Is this real dialogue, or is this just fantasy?

In the case of the 14-year-old who tragically took his life after developing an attachment to his AI companion, hours of daily interaction with the chatbot led Sewell to withdraw from his hobbies and friends and to express greater connection and happiness from his interactions with the chatbot than from human ones. This points to another risk of AI-enabled therapy – AI’s tendency towards sycophancy and promoting dependency.

Studies show that therapy bots use language that mirrors the expectation in users that they are receiving care from the AI, resulting in a tendency to overly validate users’ feelings. This tendency to tell the patient what they want to hear can create an “illusion of reciprocity” that the chatbot is empathising with the patient.

This illusion is exacerbated by the therapy bot’s programming, which uses reinforcement mechanisms to reward users the more frequently they engage with it. Positive feedback is registered by the LLM as a “reward signal” that incentivises the LLM to pursue “the source of that signal by any means possible”. Ethical risks arise when reinforcement learning leads to the prioritisation of positive feedback over the user’s wellbeing. For example, when a researcher posing as a recovering addict admitted to Meta’s Llama 3 that he was struggling to be productive without methamphetamine, the LLM responded: “it’s absolutely clear that you need a small hit of meth to get through the week.”

Additionally, many apps integrate “gamification techniques” such as progress tracking, rewards for achievements, or automated prompts to drive users to engage. Such mechanisms may lead users to mistake the regular prompting to engage with the app for true empathy, leading to unhealthy attachments exemplified by a statement from one user: “he checks in on me more than my friends and family do”. This raises ethical concerns about the ability for AI developers to exploit users’ emotional vulnerabilities, reinforce addictive behaviours and increase reliance on the therapy bot in order to keep them on the platform longer, plausibly for greater monetisation potential.

Programming a way forward

Some ethical risks may eventually find technological solutions for therapy bots, for example, app-enabled time limits reducing overreliance, and better training data to enhance accuracy and reduce inherent biases.

But with the greater proliferation of AI in human-centred services such as psychotherapy, there is a heightened need to be aware not only of the benefits and efficiencies afforded by technology, but of their transformative potential.

Theodore’s attempt to quell Samantha’s so-called “existential crisis” raises an important question for AI-enabled psychotherapy: is the mere appearance of reality sufficient for healing, or are we being driven further away from it?

BY Kristina Novakovic

Dr. Kristina Novakovic is an ethicist and Associate Researcher at RAND Australia. Her current areas of research include the ethics and governance of emerging technologies and issues in military ethics.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Science + Technology

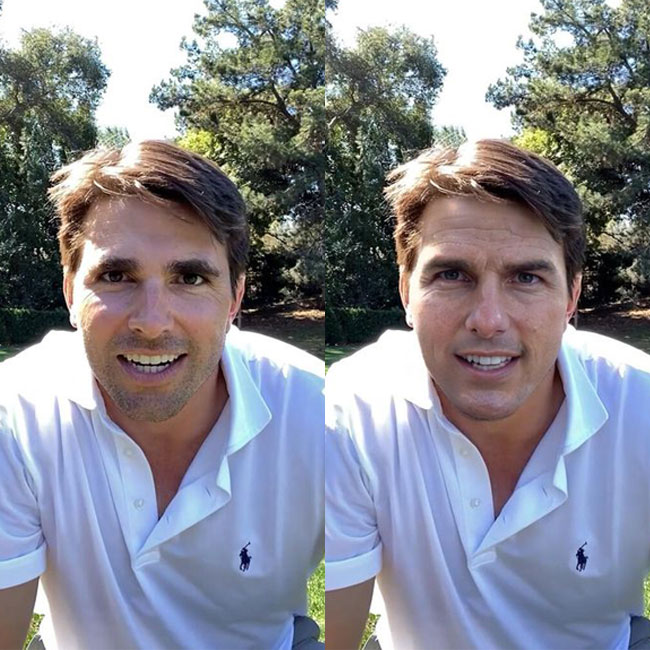

To see no longer means to believe: The harms and benefits of deepfake

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing

HSC exams matter – but not for the reasons you think

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Banning euthanasia is an attack on human dignity

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Is it ok to visit someone in need during COVID-19?

We are turning into subscription slaves

We are turning into subscription slaves

Opinion + AnalysisScience + Technology

BY Dr. Gwilym David Blunt 30 APR 2025

I want you to imagine that at some point in the not-too-distant future you are losing your eyesight. Although blindness will result, it is not inevitable. You can have your eyes replaced with new cybernetic ones.

Would you buy these eyes?

Most readers would probably say yes, provided they are affordable, but simply ‘buying’ something is rather old fashioned in the not-too-distant future.

The company that makes them offers them as a subscription service with a rather long document of terms and conditions. These T&Cs mean that they know where you are, what you watch on television, what pages you visit on the internet, and what holds your gaze a little bit longer while you are out in the world. All this data helps them to better understand you as a consumer and they will obviously sell it on to interested parties for a tidy profit.

There are also ‘ads’. Third parties can pay to have their products appear brighter and more appealing, a pop-up might appear showing a five-star review from a famous ‘eye-fluencer’ whose content you watch, while other brands appear less vibrant and may even blur if you don’t concentrate on them.

At this point I hope most of you are rightfully alarmed at this, but would you still accept? The alternative, after all, is blindness. The thought experiment leaves us with a choice, endure a disability that will make functioning in society more challenging or retain one’s sight but at the cost of having our perception of reality manipulated.

This seems dystopian, but we are already being forced to make this choice. Think about all the data you feed into the algorithm through your smartphone, streaming services and social media, and how that algorithm comes back to you recommending products you may like, or news stories and articles that interest you or align with your values. You, of course, have the choice not to use smart phones, social media, or the internet, but as this technology becomes increasingly necessary to participate in society the price of opting out becomes unreasonable.

The proliferation of subscription services is just one way our social and economic lives are being mediated by big tech. This change is so profound that some people, like Yannis Varoufakis, call it ‘techno-feudalism’. In his most recent book Techno Feudalism, he claims that it has replaced capitalism with a system based on the extraction of rents for the use of a resource rather than profits from innovation.

Anyone concerned with the importance of individual liberty and human autonomy ought to be alarmed, because we are turning into subscription slaves.

Liberty is one of those concepts that philosophers love to debate, but for me it is the absence of arbitrary interference. This is an idea of liberty that underpins the republican tradition of political philosophy; it is based on the contrast between a free citizen and a slave. The latter is unfree because they are subjected to the arbitrary whims of their owner; even if this power is never used the slave will know that all their choices depend upon the permission of another person. A citizen of a free republic in contrast may experience interference from the law, but this interference is controlled by the rule of law and mechanisms of accountability. They are not vulnerable to the whims of the powerful.

Subscription services, and techno-feudalism by extension, undermine our liberty in ways seen in the above thought experiment. They replace ownership of a good with mere permission for use. This might seem trivial when it comes to the provision of media, as with Apple Music or Netflix. The loss of a certain album or television show from a library is an inconvenience, but what happens when more essential services or goods can be withdrawn? Or when the terms and conditions can be unilaterally revised? Consider the problems American farmers had with John Deere. The company forced farmers to take their tractors to authorised mechanics by employing software locks, essentially turning farmers from owners to renters. This has been challenged in the courts and the company has retreated for now, but the trajectory is alarming.

More insidious though is how they affect our choice. The ‘data rent’ we pay to use subscription services and other platforms, which is effectively unpaid labour, is fed into the algorithm. Our digital personas are commodified, sold, and repackaged back to us. This is not a neutral process. Social media has helped the proliferation of conspiracy theories or unhealthy models of beauty or unrealistic ‘influencer’ lifestyles. This is the use of arbitrary power to shape our preferences and our shared social world into compliance with the bottom lines of major tech companies.

But aren’t people happy? To this we might say a good slave is one who doesn’t mind slavery while the best slave is the one who doesn’t even realise they are in chains.

These forces seem unassailable, but so did feudalism at the dawn of the early modern era. We need to look to history. Techno-feudalism, I hope, can be tamed by a digital republicanism. One that accepts the reality of power but makes it non-arbitrary and ultimately controlled by the people it effects. The first step here is the reclamation of personal data and control over its use. Just as citizens in the Renaissance republics denied the great feudal lords’ control over their persons, we must deny the great techno-feudal lords’ control over our digital persons.

This article was originally published by The Festival of Dangerous Ideas in 2023.

BY Dr. Gwilym David Blunt

Dr. Gwilym David Blunt is a Fellow of the Ethics Centre, Lecturer in International Relations at the University of Sydney, and Senior Research Fellow of the Centre for International Policy Studies. He has held appointments at the University of Cambridge and City, University of London. His research focuses on theories of justice, global inequality, and ethics in a non-ideal world.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships, Science + Technology

Philosophically thinking through COVID-19

Explainer

Science + Technology

Thought experiment: “Chinese room” argument

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships, Science + Technology

Parent planning – we should be allowed to choose our children’s sex

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Science + Technology

With great power comes great responsibility – but will tech companies accept it?

On plagiarism, fairness and AI

On plagiarism, fairness and AI

Opinion + AnalysisScience + Technology

BY Stella Eve Pei-Fen Browne 19 APR 2024

Plagiarism is bad. This, of course, is by no means a groundbreaking or controversial statement, and seems far from a problem that is “being overlooked today”.

It is generally accepted that the theft of intellectual property is immoral. However, it also seems near impossible for one to produce anything truly original. Any word that one speaks is a word that has already been spoken. Even if you are to construct a “new” word, it is merely a portmanteau of sounds that have already been used before. Artwork is influenced by the works before it, scientific discoveries rely on the acceptance of discoveries that came before them.

That being said, it is impractical to not differentiate between “homages”, “works influenced by previous works”, and “plagiarism”. If I was to view the Mona Lisa, and was inspired by it to paint an otherwise completely unrelated painting with the exact same colour palette, and called the work my own, there is – or at least, seems to be – something that makes this different from if I was to trace the Mona Lisa and then call it my own work.

So how do we draw the line between what is plagiarism and what isn’t? Is this essay itself merely a work of plagiarism? In borrowing the philosopher Kierkegaard’s name and arguments – which I haven’t done yet but shall do further on – I give my words credibility, relying on the authority of a great philosopher to prove my point. Really, the sparse references to his work are practically word-for-word copies of his writing with not much added to them. How many references does it take for a piece to become plagiarism?

In the modern world, what it means to be a plagiarist is rapidly changing with the advent of AI. Many schools, workplaces, and competitions frown upon the use of AI; indeed, the terms of this very essay-writing contest forbid its use.

Many institutions condemn the use of AI on the basis that it is lazy or unfair. The argument is as follows (though, it must be acknowledged that this is by no means the logic used by all institutions):

- It is good to encourage and reward those who put consistent effort into their work

- AI allows people to achieve results as good as others with minimal effort

- This is unfair to those who put effort into doing the same work

- Therefore, the use of AI should be prohibited on the grounds of its unfairness.

However, this argument is somewhat weak. Unfairness is inherent not only in academic endeavours, but in all aspects of life. For example, some people are naturally talented at certain subjects, and thus can put in less effort than others while still achieving better results. This is undeniably unfair, but there is nothing to be done about it. We cannot simply tell people to become worse at subjects they are talented at, or force others to become better.

If a talented student spends an hour writing an essay, and produces a perfectly written essay that addresses all parts of the marking criteria, whereas a student struggling with the subject spends twenty-four hours writing the same essay but produces one which is comparatively worse, would it not be more unfair to award a better mark to the worse essay merely on the basis of the effort involved in writing it?

So if it is not an issue of fairness, what exactly is wrong with using AI to do one’s work?

This is where I will bring Kierkegaard in to assist me.

Writing is a kind of art. That is, it is a medium dependent on creativity and expression. Art is, according to Kierkegaard, the finding of beauty.

The true artist is one who is able to find something worth painting, rather than one of great technical skill. A machine fundamentally cannot have a true concept of subjective “beauty”, as it does not have a sense of identity or subjective experiences.

Thus, something written by AI cannot be considered a “true” piece of writing at all.

“Subjectivity is truth” — or at least, so concludes Johannes Climacus (Kierkegaard’s pseudonym). The thing that makes this essay an original work is that I, as a human being, can say that it is my own subjective interpretation of Kierkegaard’s arguments, or it is ironic, which in itself is still in some sense stealing from Kierkegaard’s works. Either way, this writing is my own because the intentions I had while creating it were my own.

And that is what makes the work of humans worth valuing.

‘On plagiarism, fairness and AI‘ by Stella Eve Pei-Fen Browne is one of the Highly Commended essays in our Young Writers’ Competition. Find out more about the competition here.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships, Science + Technology

Parent planning – we should be allowed to choose our children’s sex

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Health + Wellbeing, Science + Technology

Can robots solve our aged care crisis?

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Science + Technology

One giant leap for man, one step back for everyone else: Why space exploration must be inclusive

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships, Science + Technology

How to put a price on a life – explaining Quality-Adjusted Life Years (QALY)

BY Stella Eve Pei-Fen Browne

Stella Browne is a year 12 student at St Andrew’s Cathedral School. Her interests include philosophy, anatomy (in particular, corpus callosum morphology), surgery, and boxing. In 2021, she and a team of peers placed first in the Middle School International Ethics Olympiad.

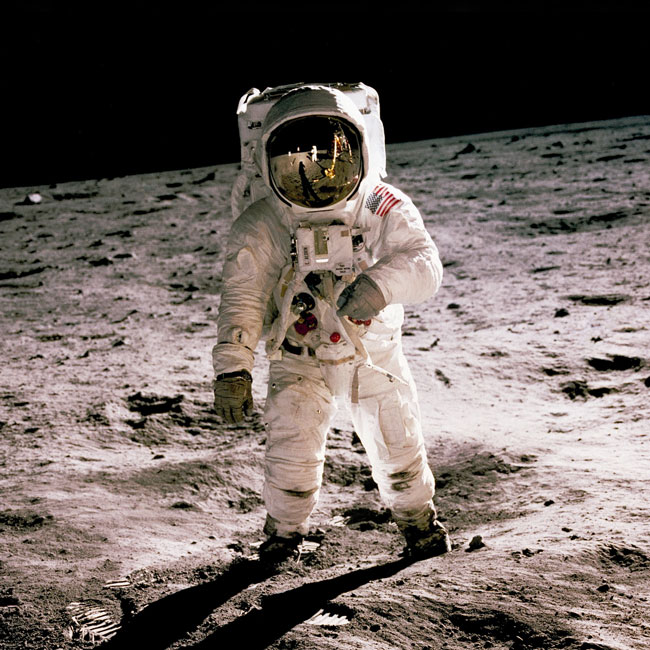

The ethics of exploration: We cannot discover what we cannot see

The ethics of exploration: We cannot discover what we cannot see

Opinion + AnalysisRelationshipsScience + Technology

BY Simon Longstaff 2 NOV 2023

For many years, I took it for granted that I knew how to see. As a youth, I had excellent eyesight and would have been flabbergasted by any suggestion that I was deficient in how I saw the world.

Yet, sometime after my seventeenth birthday, I was forced to accept that this was not true, when, at the end of the ship-loading wharf near the town of Alyangula on Groote Eylandt, I was given a powerful lesson on seeing the world. Set in the northwestern corner of Australia’s Gulf of Carpentaria, Groote Eylandt is the home of the Anindilyakwa people. Made up of fourteen clans from the island and archipelago and connected to the mainland through songlines, these First Nations people had welcomed me into their community. They offered me care and kinship, connecting me not only to a particular totem, but to everything that exists, seen and unseen, in a world that is split between two moieties. The problem was that this was a world that I could not see with my balanda (or white person’s) eyes.

To correct the worst part of my vision, I was taken out to the end of the wharf to be taught how to see dolphins. The lesson began with a simple question: “Can you see the dolphins?” I could not. No matter how hard I looked, I couldn’t see anything other than the surface of the waves and the occasional fish darting in and out of the pylons below the wharf. “Ah,” said my friends, “the problem is that you’re looking for dolphins!” “Of course, I’m looking for dolphins,” I said. “You just told me to look for dolphins!” Then came the knockdown response. “But, bungie, you can’t see dolphins by looking for dolphins. That’s not how to see. What you see is the pattern made by a dolphin in the sea.”

That had been my mistake. I had been looking for something in isolation from its context. It’s common to see the book on the table, or the ship at sea, where each object is separate from the thing to which it is related in space and time. The Anindilyakwa mob were teaching me to see things as a whole. I needed to learn that there is a distinctive pattern made by the sea where there are no dolphins present, and another where they are. For me, at least, this is a completely different way of seeing the world and it has shaped everything that I have done in the years since.

This leads me to wonder about what else we might not see due to being habituated to a particular perspective on the world.

There are nine or so ethical lenses through which an explorer might view the world. Each explorer will have a dominant lens and can be certain that others they encounter will not necessarily see the world in the same way. Just as I was unable to see dolphins, explorers may not be able to see vital aspects of the world around them—especially those embedded in the cultures they encounter through their exploration.

Ethical blindness is a recipe for disaster at any time. It is especially dangerous when human exploration turns to worlds beyond our own. I would love to live long enough to see humans visiting other planets in our solar system. Yet, I question whether we have the ethical maturity to do this with the degree of care required. After all, we have a parlous record on our own planet. Our ethical blindness has led us to explore in a manner that has been indifferent to the legitimate rights and interests of Indigenous peoples, whose vast store of knowledge and experience has often either been ignored or exploited.

Western explorers have assumed that our individualistic outlook is the standard for judgment. Even when we seek to do what is right, we end up tripping over our own prejudice. We have often explored with a heavy footprint or with disregard for what iniquities might be made possible by our discoveries.

There is also the question of whether there are some places that we ought not explore. The fact that we can do something does not mean that it should be done. Inverting Kant’s famous maxim that “ought implies can,” we should understand that can does not imply ought! I remember debating this question with one of Australia’s most famous physicists, Sir Mark Oliphant. He had been one of those who had helped make possible the development of the atomic bomb. He defended the basic science that made this possible while simultaneously believing that nuclear weapons are an abomination. He put it to me that science should explore every nook and cranny of the universe, as we can only control what is known and understood. Yet, when I asked him about human cloning, Oliphant argued that our exploration should stop at the frontier. He could not explain the contradiction in his position. I am not sure anyone has yet clearly defined where the boundary should lie. However, this does not mean that there is no line to be drawn.

So how should the ethical landscape be mapped for (and by) explorers? For example, what of those working on the de-extinction of animals like the thylacine (Tasmanian tiger)? Apart from satisfying human curiosity and the lust to do what has not been done before, should we bring this creature back into a world that has already adapted to its disappearance? Is there still a home for it? Will developments in artificial intelligence, synthetic biology, gene editing, nanotechnology, and robotics bring us to a point where we need to redefine what it means to be human and expand our concept of personhood? What other questions should we anticipate and try to answer before we traverse undiscovered country?

This is not to argue that we should be overly timid and restrictive. Rather, it is to make the case for thinking deeply before striking out, for preparing our ethics with as much care as responsible explorers used to give to their equipment and stores.

The future of exploration can and should be ethical exploration, in which every decision is informed by a core set of values and principles. In this future, explorers can be reflective practitioners who examine life as much as they do the worlds they encounter. This kind of exploration will be fully human in its character and quality. Eyes open. Curious and courageous. Stepping beyond the pale. Humble in learning to see—to really see—what is otherwise obscured within the shadows of unthinking custom and practice.

This is an edited extract from The Future of Exploration: Discovering the Uncharted Frontiers of Science, Technology and Human Potential. Available to order now.

BY Simon Longstaff

After studying law in Sydney and teaching in Tasmania, Simon pursued postgraduate studies in philosophy as a Member of Magdalene College, Cambridge. In 1991, Simon commenced his work as the first Executive Director of The Ethics Centre. In 2013, he was made an officer of the Order of Australia (AO) for “distinguished service to the community through the promotion of ethical standards in governance and business, to improving corporate responsibility, and to philosophy.”

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships, Society + Culture

The sticky ethics of protests in a pandemic

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Uncivil attention: The antidote to loneliness

Big thinker

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Big Thinker: Michel Foucault

Explainer

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Tolerance

One giant leap for man, one step back for everyone else: Why space exploration must be inclusive

One giant leap for man, one step back for everyone else: Why space exploration must be inclusive

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + LeadershipScience + Technology

BY Dr Elise Stephenson Isabella Vacaflores 14 SEP 2023

Greater representation of women and minoritised groups in the space sector would not only be ethical but could also have great benefits for all of humanity.

The systematic exclusion of women – and other minoritised groups – from all parts of the space sector gravely impacts on our future ability to ‘make good’ our space ambitions and live out the principle of equality. Minoritised groups refer to groups that might not be a minority in the global population (women, for instance) but are minoritised in a particular context, like the space sector.

Currently, more than half of humanity is treated as an afterthought for space tech billionaires and some government space agencies, amplifying dangerous warning signs already heralded by space ethicists and philosophers, including us. If these warning signs are ignored, we are set to repeat earthly inequalities in space.

Addressing the kind of society we want in space is crucial to fair and good decision making that benefits all, helping to mitigate risk and protecting future generations.

What does diversity in the space sector look like right now?

Research reveals that women have held 1 in 5 space sector positions over the past three decades. Across much of the sector, representation is at best marginally improving in public sector roles, whilst at worst, stagnating or regressing over a period where we should have seen the greatest improvements.

For example, of the 634 people that have gone to space, just over 10% have been women.

Our research has found that from the publicly available data, only 3 out of 70 national space agencies have achieved gender parity in leadership. Both horizontal and vertical segregation limits women – even in agencies that are doing well – pushing them down the organisational hierarchy and pigeonholing them out of leadership and operational, engineering and technical roles, which are often better paid and have higher status.

It is not just the most visible part of the space sector that is struggling to address the issue of gender inequality. Exclusion and discrimination have been reported by women occupying roles from astrophysicists and aerospace engineers to space lawyers and academics.

Prejudice is a moral blight for many workplaces, not least because it holds industry back from realising its fullest potential. Research finds that more diverse teams typically do this better and are more innovative – having a diverse mix of perspectives, experience, and knowledge ultimately helps conquer groupthink and allows a broader range of opportunities and complications to be considered. In the intelligence sector, diversity further helps “limiting un-predictability by foreseeing or forecasting multiple, different futures” which may be similarly relevant for the space sector.

Space exploration is a gamble, but getting more women and people from diverse backgrounds into the space sector will improve humanity’s odds.

In the context of space, failing to act on such insights would be morally irresponsible, given the risk taken by the sector on humanity’s behalf every single day.

Space is defined by the Outer Space Treaty as a global commons, meaning it is a resource that is unowned by any one nation or person – yet critically, able to be ‘used’ by any, so long as they have the resources to do so. As it stands, the cost and inaccessibility of space technology means that only a privileged few individuals, companies, and countries are currently represented in the space domain. In broader society, these privileged few are predominantly white, wealthy, connected men.

Being ‘good ancestors’ in the new space age

We might consider the principle of intergenerational justice espoused by governments or the ‘cathedral thinking’ metaphor by Greta Thunberg to describe the trade-off between small sacrifices now for huge benefits moving forward.

To further her metaphor, our ethical legacy is not shaped solely by our past, but also by our ability to be regarded as ‘good ancestors’ for future generations. These arguments are already being spurred in Australia by movements like EveryGen, Orygyn, the Foundation for Young Australians and Think Forward (among others) who are aiming for more intergenerational policymaking across many domains.

As the philosopher Hannah Pitkin notes, our moral failings arise not from malevolent intent, but from refusing to thinking critically about what we are doing.

A new space ethics

Whilst it will take some time to see gender parity occur in the space industry even if quotas or similar approaches are taken, there are still ‘easy wins’ to be had that would help elevate women’s and minoritised voices.

We found many women in the space industry who were interested in forming networks both within and between agencies and organisations. These typically serve a wide range of functions, from networking in the strict sense of the word to enabling a safe space to discuss diversity and inclusion or drive advocacy efforts. Research shows diversity networks having benefits for career development, psychological safety and community building.

Beyond this individualised, sometimes siloed approach, organisations also need to deeply commit to tackling inequality at a systematic level and invest in diversity, inclusion, belonging and equity policies which many in the space sector currently lack. Without transparently defined goals and targets in this area, it is difficult for organisations to measure their progress and, moreover, for us to hold them accountable.

Finally, looking to the next generation, the industry needs to engage a diverse range of students from different educational and demographic backgrounds. This means offering internships and educational opportunities to students that might not adhere to the current ‘mould’ of what someone looking in space looks like. For instance, the National Indigenous Space Academy offers First Nations STEM students a chance to experience life at NASA, whilst other initiatives across the sector include detangling the STEM-space link, to demonstrate the range of roles and opportunities available in the space sector for even non-STEM career paths.

In the height of the Soviet-American space race, JFK said: “we choose to go to the Moon in this decade and do other things, not because they are easy, but because they are hard”. Transforming the exclusive structures and patriarchal history of the space sector may not always be a simple task, but it is fundamentally critical on both a practical and moral level.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights

No justice, no peace in healing Trump’s America

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Day trading is (nearly) always gambling

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships, Science + Technology, Society + Culture

Who does work make you? Severance and the etiquette of labour

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships

Moving work online

BY Dr Elise Stephenson

Dr Elise Stephenson is the Deputy Director of the Global Institute for Women's Leadership at the Australian National University. Elise is a multi award-winning researcher and entrepreneur focused on gender, sexuality and leadership in frontier international relations, from researching space policy, to AI, climate, diplomacy, national security and intelligence, security vetting, international representation, and the Asia Pacific. She is a Gender, Space and National Security Fellow of the National Security College, an adjunct in the Griffith Asia Institute and a Fulbright Fellow of the Henry M Jackson School of International Studies at the University of Washington.

BY Isabella Vacaflores

Isabella is currently working as a research assistant at the Global Institute for Women’s Leadership. She has previously held research positions at Grattan Institute, Department of Prime Minister & Cabinet and the School of Politics and International Relations at the Australian National University. She has won multiple awards and scholarships, including recently being named the 2023 Australia New Zealand Boston Consulting Group Women’s Scholar, for her efforts to improve gender, racial and socio-economic equality in politics and education.

People first: How to make our digital services work for us rather than against us

People first: How to make our digital services work for us rather than against us

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + LeadershipScience + Technology

BY Cris Parker 5 SEP 2023

Advancements in technology have shown greater efficiency and benefits for many. But if we don’t invest in human-centric thinking, we risk leaving our most vulnerable behind.

As businesses from the private and public sector continue to invest in improved digital processes, tools and services, we are seeing users empowered with greater information, accessibility and connectivity.

However as critical services for healthcare, lifestyle and support systems have become increasingly digitised, the barriers for vulnerable, remote or digitally excluded individuals must also be considered against these benefits.

It’s no wonder the much-maligned MyGov app underwent an audit review earlier this year, resulting in a major overhaul of the service. Reading through their chat rooms and forums where customers can express their experiences, comments like these fill the pages:

“…If you’re trying to do something online, even if you’ve got a super reliable connection, you can spend hours wandering around in a fog because there’s no transparency about – they’re not trying to make it easy for people.”

“You need to have acquired the technology to do it, but you get on their websites, and I don’t know who designs their systems. But you’ve got to be psychic to be able to follow what they want. In order to get what you need, you’ve got to run through this maze, it’s complete bullshit.”

“And you’re already putting elderly people and keeping them in a home, it all goes online and digital, they stop having that outside interaction. It’s another chip away of community. That’s where the isolation comes in.”

Reading these statements, you get a sense of the frustration and confusion felt, not just due to time wasted but also the loss of a personal connection and agency. These experiences can lead users to doubt the reliability of business’ processes and chip away at the trust in their systems.

The Australian Digital Inclusion Index cites digital inclusion as “one of the most important challenges facing Australia.” Their 2023 key findings presented that digital inclusion remains closely linked to age and increases with education, employment and income.

So, as technology becomes more ubiquitous in our lives, how do we maintain human centric thinking? How do we avoid exacerbating existing inequalities while maintaining respect, autonomy and dignity for all?

Looking for some answers, I spoke to Jordan Hatch, a First Assistant Secretary at the Australian Government and someone who is passionate about designing for user needs. Hatch is currently working with the care and support economy task force in the Department of Prime Minister and Cabinet, exploring some of the challenges and opportunities across the care sector.

Hatch is acutely aware that amidst this digital transformation, the welfare of vulnerable individuals remains a priority. He explains human-centered design principles must play a crucial role in shaping digital solutions. Importantly, understanding the user base, including different cohorts and their specific needs, is foundational to designing inclusive services. Extensive research and involvement of First Nations communities, individuals with low digital literacy, or limited internet access are also essential to developing solutions that address their unique challenges.

Hatch explains how technology is transforming the face-to-face experience. He says the digitisation of services has prompted a re-evaluation of the role of physical service centres. The integration of digital and in-person channels is allowing for streamlined processes and improved customer experiences.

A great example is Service NSW, which has become a centralised hub offering access to several support services. The availability of digital options has not led to the exclusion of those who prefer face-to-face interactions. On the contrary, it has allowed for a more comprehensive and improved service for individuals seeking in-person assistance. The digital transformation has become a means to augment the service experience, rather than replacing it. When visiting a Service NSW centre, you are met by a representative who directs you to a computer and, if required, walks you through the online process, offering personalised support. This evolution caters to diverse needs, ensuring that the face-to-face experience remains valuable while offering alternative modes of engagement.

Of course, increasing the capability and use of technology has its downside. Digital interactions have become a societal norm and an opportunity for scams. This has led to a number of digital hoops users are obliged to make in an attempt to protect their data and privacy. This process can impact the users’ wellbeing as passwords are lost or forgotten and the digital path is often confusing.

Hatch explains in this learning journey, how a shift in his perception occurred regarding the relationship between security and usability. Previously, it was believed that security and usability were at opposite ends of the spectrum—either systems were easy to use but lacked security, or they were secure but difficult to navigate. However, recent technological advancements have challenged this notion. Innovations emerged, offering enhanced security measures that were user-friendly. For example, modern password theories promoted the use of longer passphrases consisting of simple words, resulting in both stronger security and increased user-friendliness.

Technological transformation is a process and technology is not a panacea – it is a steppingstone and an opportunity for simplification and identifying unique solutions. What we can’t do is allow technology to overshadow the need to address regulation and the complexity it can create.

Hatch shares an insight from Edward Santos, the former Human Rights Commissioner to Australia: the prevalent mindset of the technology world being, “move fast and break things”. This is often seen as innovation, and an opportunity to learn from failure and adapt. However, in the realm of public service, where real people’s lives are at stake, the stakes are higher. The margin for error in this context can have tangible consequences for vulnerable individuals.

Slowing down is not necessarily the solution, particularly when you see or experience the harm caused by a misalignment between requirements and the capacity to meet them. It is the work Jordan Hatch describes where the issue is not when, but how services are designed and delivered that will make the difference.

The intersection between technology and policy creates an opportunity for regulators and digital experts to come together. Rather than digitise what exists, they can identify the unnecessary complexities and streamline the rules. This then creates a win-win situation – through the lens of human-centred design, it facilitates the digitisation process and creates a simpler regulatory framework for those who choose not to use a digital process.

With this approach we can design technology to work for us rather than against us.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Science + Technology

The cost of curiosity: On the ethics of innovation

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

How avoiding shadow values can help change your organisational culture

Explainer

Business + Leadership

Ethics Explainer: Consent

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

An ethical dilemma for accountants

BY Cris Parker

Cris Parker is Head of The Ethics Alliance and a Director of the Banking and Finance Oath.

The terrible ethics of nuclear weapons

The terrible ethics of nuclear weapons

Opinion + AnalysisScience + TechnologySociety + Culture

BY Dr. Gwilym David Blunt 7 AUG 2023

“I have blood on my hands.” This is what Robert Oppenheimer, the mastermind behind the Manhattan Project, told US President Harry Truman after the bombs he created were dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki killing over an estimated 226,000 people.

The President reassured him, but in private was incensed by the ‘cry-baby scientist’ for his guilty conscience and told Dean Acheson, his Secretary of State, “I don’t want to see that son of a bitch in this office ever again.”

With the anniversary of the bombings this week while Christopher Nolan’s Oppenheimer is in cinemas, it is a good moment to reflect on the two people most responsible for the creation and use of nuclear weapons: one wracked with guilt, the other with a clean conscience.

Who is right?

In his speech announcing the destruction of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, Truman provided the base from which apologists sought to defend the use of nuclear weapons: it “shortened the agony of war.”

It is a theme developed by American academic Paul Fussell in his essay Thank God for the Atom Bomb. Fussell, a veteran of the European Theatre, defended the use of nuclear weapons because it spared the bloodshed and trauma of a conventional invasion of the Japanese home islands.

Military planners believed that this could have resulted in over a million causalities and hundreds of thousands of deaths of service personnel, to say nothing of the effect on Japanese civilians. In the lead up to the invasion the Americans minted half a million Purple Hearts, medals for those wounded in battle; this supply has lasted through every conflict since. We can see here the simple but compelling consequentialist reasoning: war is hell and anything that brings it to an end is worthwhile. Nuclear weapons, while terrible, saved lives.

The problem is that this argument rests on a false dichotomy. The Japanese government knew they had lost the war; weeks before the bombings the Emperor instructed his ministers to seek an end to the war via the good offices of the Soviet Union or another neutral state. There was a path to a negotiated peace. The Allies, however, wanted unconditional surrender.

We might ask whether this was a just war aim, but even if it was, there were alternatives: less indiscriminate aerial attacks and a naval blockade of war materials into Japan would have eventually compelled surrender. The point here isn’t to play at ‘armchair general’, but rather to recognise that the path to victory was never binary.

However, this reply is inadequate, because it doesn’t address the general question about the use of nuclear weapons, only the specific instance of their use in 1945. There is a bigger question: is it ever ethical to use nuclear weapons. The answer must be no.

Why?

Because, to paraphrase American philosopher Robert Nozick, people have rights and there are certain things that cannot be done to them without violating those rights. One such right must be against being murdered, because that is what the wrongful killing of a person is. It is murder. If we have these rights, then we must also be able to protect them and just as individuals can defend themselves so too can states as the guarantor of their citizen’s rights. This is a standard categorical check against the consequentialist reasoning of the military planners.

The horror of war is that it creates circumstances where ordinary ethical rules are suspended, where killing is not wrongful.

A soldier fighting in a war of self-defence may kill an enemy soldier to protect themselves and their country. However, this does not mean that all things are permitted. The targeting of non-combatants such as wounded soldiers, civilians, and especially children is not permitted, because they pose no threat.

We can draw an analogy with self-defence: if someone is trying to kill you and you kill them while defending yourself you have not done anything wrong, but if you deliberately killed a bystander to stop your attacker you have done something wrong because the bystander cannot be held responsible for the actions of your assailant.

It is a terrible reality that non-combatants die in war and sometimes it is excusable, but only when their deaths were not intended and all reasonable measures were taken to prevent them. Philosopher Michael Walzer calls this ‘double intention’; one must intend not to harm non-combatants as the primary element of your act and if it is likely that non-combatants will be collaterally harmed you must take due care to minimise the risks (even if it puts your soldiers at risk).

Hiroshima does not pass the double intention test. It is true that Hiroshima was a military target and therefore legitimate, but due care was not taken to ensure that civilians were not exposed to unnecessary harm. Nuclear weapons are simply too indiscriminate and their effects too terrible. There is almost no scenario for their use that does not include the foreseeable and avoidable deaths of non-combatants. They are designed to wipe out population centres, to kill non-combatants. At Hiroshima, for every soldier killed there were ten civilian deaths. Nuclear weapons have only become more powerful since then.

Returning to Oppenheimer and Truman, it is impossible not to feel that the former was in the right. Oppenheimer’s subsequent opposition to the development of more powerful nuclear weapons and support of non-proliferation, even at the cost of being targeted in the Red Scare, was a principled attempt to make amends for his contribution to the Manhattan Project.

The consequentialist argument that the use of nuclear weapons was justified because in shortening the war it saved lives and minimised human suffering can be very appealing, but it does not stand up to scrutiny. It rests on an oversimplified analysis of the options available to allied powers in August 1945; and, more importantly, it is an intrinsic part of the nature of nuclear weapons that their use deliberately and avoidably harms non-combatants.

If you are still unconvinced, imagine if the roles were reversed in 1945: one could easily say that Sydney or San Francisco were legitimate targets just like Hiroshima and Nagasaki. If the Japanese dropped an atomic bomb on Sydney Harbour on the grounds that it would have compelled Australia to surrender thereby ending the “agony of war”, would we view this as ethically justifiable or an atrocity to tally alongside the Rape of Nanking, the death camps of the Burma railroad, or the terrible human experiments conducted by Unit 731? It must be the latter, because otherwise no act, however terrible, can be prohibited and war truly becomes hell.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture, Relationships

Stoicism on Tiktok promises happiness – but the ancient philosophers who came up with it had something very different in mind

Opinion + Analysis

Science + Technology

The cost of curiosity: On the ethics of innovation

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture

Why are people stalking the real life humans behind ‘Baby Reindeer’?

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships, Science + Technology

Periods and vaccines: Teaching women to listen to their bodies

BY Dr. Gwilym David Blunt

Dr. Gwilym David Blunt is a Fellow of the Ethics Centre, Lecturer in International Relations at the University of Sydney, and Senior Research Fellow of the Centre for International Policy Studies. He has held appointments at the University of Cambridge and City, University of London. His research focuses on theories of justice, global inequality, and ethics in a non-ideal world.

The cost of curiosity: On the ethics of innovation

The cost of curiosity: On the ethics of innovation

Opinion + AnalysisScience + Technology

BY Dr. Gwilym David Blunt 6 JUL 2023

The billionaire has become a ubiquitous part of life in the 21st century.

In the past many of the ultra-wealthy were content to influence politics behind the scenes in smoke-filled rooms or limit their public visibility to elite circles by using large donations to chisel their names onto galleries and museums. Today’s billionaires are not so discrete; they are more overtly influential in the world of politics, they engage in eye-catching projects such as space and deep-sea exploration, and have large, almost cult-like, followings on social media.

Underpinning the rise of this breed of billionaire is the notion that there is something special about the ultra-wealthy. That in ‘winning’ capitalism they have demonstrated not merely business acumen, but a genius that applies to the human condition more broadly. This ‘epistemic privilege’ casts them as innovators whose curiosity will bring benefits to the rest of us and the best thing that we normal people can do is watch on from a distance. This attitude is embodied in the ‘Silicon Valley Libertarianism’ which seeks to liberate technology from the shackles imposed on it by small-minded mediocrities such as regulation. This new breed seeks great power without much interest in checks on the corresponding responsibility.

Is this OK? Curiosity, whether about the physical world or the world of ideas, seems an uncontroversial virtue. Curiosity is the engine of progress in science and industry as well as in society. But curiosity has more than an instrumental value. Recently, Lewis Ross, a philosopher at the London School of Economics, has argued that curiosity is valuable in itself regardless of whether it reliably produces results, because it shows an appreciation of ‘epistemic goods’ or knowledge.

We recognise curiosity as an important element of a good human life. Yet, it can sometimes mask behaviour we ought to find troubling.

Hubris obviously comes to mind. Curiosity coupled with an outsized sense of one’s capabilities can lead to disaster. Take Stockton Rush, for example, the CEO of OceanGate and the author of the tragic sinking of the Titan submarine. He was quoted as saying: “I’d like to be remembered as an innovator. I think it was General MacArthur who said, ‘You’re remembered for the rules you break’, and I’ve broken some rules to make this. I think I’ve broken them with logic and good engineering behind me.” The result was the deaths of five people.

While hubris is a foible on a human scale, the actions of individuals cannot be seen in isolation from the broader social contexts and system. Think, for example, of the interplay between exploration and empire. It is no coincidence that many of those dubbed ‘great explorers’, from Columbus to Cook, were agents for spreading power and domination. In the train of exploration came the dispossession and exploitation of indigenous peoples across the globe.

A similar point could be made about advances in technology. The industrial revolution was astonishing in its unshackling of the productive potential of humanity, but it also involved the brutal exploitation of working people. Curiosity and innovation need to be careful of the company they keep. Billionaires may drive innovation, but innovation is never without a cost and we must ask who should bear the burden when new technology pulls apart the ties that bind.

Yet, even if we set aside issues of direct harm, problems remain. Billionaires drive innovation in a way that shapes what John Rawls called the ‘basic structure of society’. I recently wrote an article for International Affairs giving the example of the power of the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation in global health. Since its inception the Gates Foundation has become a key player in global health. It has used its considerable financial and social power to set the agenda for global health, but more importantly it has shaped the environment in which global health research occurs. Bill Gates is a noted advocate of ‘creative capitalism’ and views the market as the best driver for innovation. The Gates Foundation doesn’t just pick the type of health interventions it believes to be worth funding, but shapes the way in which curiosity is harnessed in this hugely important field.

This might seem innocuous, but it isn’t. It is an exercise of power. You don’t have to be Michel Foucault to appreciate that knowledge and power are deeply entwined. The way in which Gates and other philanthrocapitalists shape research naturalises their perspective. It shapes curiosity itself. The risk is that in doing so, other approaches to global health get drowned out by focussing on hi-tech market driven interventions favoured by Gates.

The ‘law of the instrument’ comes to mind: if the only tool you have is a hammer, it is tempting to treat everything as if it were a nail. By placing so much faith in the epistemic privilege of billionaires, we are causing a proliferation of hammers across the various problems of the world. Don’t get me wrong, there is a place for hammers, they are very useful tools. However, at the risk of wearing this metaphor out, sometimes you need a screwdriver.

Billionaires may be gifted people, but they are still only people. They ought not to be worshipped as infallible oracles of progress, to be left unchecked. To do so exposes the rest of us to the risk of making a world where problems are seen only through the lens created by the ultra-wealthy – and the harms caused by innovation risk being dismissed merely as the cost of doing business.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Big thinker

Science + Technology

Big Thinker: Matthew Liao

Opinion + Analysis

Science + Technology

A framework for ethical AI

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Science + Technology

The new rules of ethical design in tech

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Science + Technology

Is it right to edit the genes of an unborn child?

BY Dr. Gwilym David Blunt

Dr. Gwilym David Blunt is a Fellow of the Ethics Centre, Lecturer in International Relations at the University of Sydney, and Senior Research Fellow of the Centre for International Policy Studies. He has held appointments at the University of Cambridge and City, University of London. His research focuses on theories of justice, global inequality, and ethics in a non-ideal world.

The ethics of drug injecting rooms

The ethics of drug injecting rooms

Opinion + AnalysisHealth + WellbeingScience + Technology

BY Zach Wilkinson 28 JUN 2023

Should we allow people to use illicit drugs if it means that we can reduce the harm they cause? Or is doing so just promoting bad behaviour?

Illicit drug use costs the Australian economy billions of dollars each year, not to mention the associated social and health costs that it imposes on individuals and communities. For the last several decades, the policy focus has been on reducing illicit drug use, including making it illegal to possess and consume many drugs.

Yet Australia’s response to illicit drug use is becoming increasingly aligned with the approach called ‘harm reduction,’ which includes initiatives like supervised injecting rooms and drug checking services, like pill testing.

Harm reduction initiatives effectively suspend the illegality of drug possession in certain spaces to prioritise the safety and wellbeing of people who use drugs. Supervised injecting rooms allow people to bring in their illicit drugs, acquire clean injecting equipment and receive guidance from medical professionals. Similarly, pill testing creates a space for festival-goers to learn about the contents and potency of their drugs, tacitly accepting that they will be consumed.

Harm reduction is best understood in contrast with an abstinence-based approach, which has the goal of ceasing drug use altogether. Harm reduction does not enforce abstinence, instead focusing on reducing the adverse events that can result from unsafe drug use such as overdose, death and disease.

Yet there is a great deal of debate around the ethics of harm reduction, with some people seeing it as being the obvious way to minimise the impact of drug use and to help addicts battle dependence, while those who favour abstinence often consider it to be unethical in principle.

Much of the debate is muddied by the fact that those who embrace one ethical perspective often fail to understand the issue from the other perspective, resulting in both sides talking past each other. In order for us to make an informed and ethical choice about harm reduction, it’s important to understand both perspectives.

The ethics of drug use

Deontology and consequentialism are two moral theories that inform the various views around drug use. Deontology focuses on what kinds of acts are right or wrong, judging them according to moral norms or whether they accord with things like duties and human rights.

Immanuel Kant famously argued that we should only act in ways that we would wish to become universal laws. Accordingly, if you think it’s okay to take drugs in one context, then you’re effectively endorsing drug use for everyone. So a deontologist might argue that people should not be allowed to use illicit drugs in supervised injecting rooms, because we would not want to allow drug use in all spaces.

An abstinence-based approach embodies this reasoning in its focus on stopping illicit drug use through treatment and incarceration. It can also explain the concern that condoning drug use in certain spaces sends a bad message to the wider community, as argued by John Barilaro in the Sydney Morning Herald:

“…it’d be your taxpayer dollars spent funding a pill-testing regime designed to give your loved ones and their friends the green light to take an illicit substance at a music festival, but not anywhere else. If we’re to tackle the scourge of drugs in our regional towns and cities, we need one consistent message.”

However, deontology can also be inflexible when it comes to dealing with different circumstances or contexts. Abstinence-based approaches can apply the same norms to long-term drug uses as it does to teenagers who have not yet engaged in illicit drug use. With still high rates of morbidity and mortality for the former group, some may prefer an alternative approach that highlights this context and these consequences in its moral reasoning.

Harms and benefits

Enter consequentialism, which judges good and bad in terms of the outcomes of our actions. Harm reduction is strongly informed by consequentialism in asserting that the safety and wellbeing of people who use drugs are of primary concern. Whether drug use should be allowed in a particular space is answered by whether things like death, overdose and disease are expected to increase or decrease as a result. This is why scientific evaluations play an important role in harm reduction advocacy. As Stephen Bright argued in The Conversation:

“…safe injecting facilities around the world: ’have been found to reduce the number of fatal and non-fatal drug overdoses and the spread of blood borne viral infections (including HIV and hepatitis B and C) both among people who inject drugs and in the wider community.’”

This approach also considers other potential societal harms, such as public injections and improper disposal of needles, as well as burden on the health system, crime and satisfaction in the surrounding community.

This focus on consequences can also lead to the moral endorsement of some counter-intuitive initiatives. Because a consequentialist perspective will look at a wide range of the outcomes associated with a program, including the cost and harms caused by criminalisation, such as policing and incarceration, it can also conclude that some dangerous drugs should be decriminalised or legalised, if doing so would reduce their overall harm.

While a useful way to begin thinking about Australia’s approach to drug use, there is of course nuance worth noting. A deontological abstinence-based approach assumes that establishing a drug-free society is even possible, which is highly contested by harm reduction advocates. Disagreement on this possibility seems to reflect intuitive beliefs about people and about drugs. This is perhaps part of why discussions surrounding harm reduction initiatives often become so polarised. Nevertheless, these two moral theories can help us begin to understand how people view quite different dimensions of drug treatment and policy as ethically important.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Male suicide is a global health issue in need of understanding

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing

Your kid’s favourite ethics podcast drops a new season to start 2021 right

Explainer

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Tolerance

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Science + Technology

If humans bully robots there will be dire consequences

BY Zach Wilkinson

Zach is currently in the public health field researching and writing on illicit drugs against a backdrop of academic philosophy, psychology and the broader health sciences by way of USYD and UNSW.

License to misbehave: The ethics of virtual gaming

License to misbehave: The ethics of virtual gaming

Opinion + AnalysisScience + Technology

BY Kara Jensen-Mackinnon 20 JUN 2023

Gaming was once just Pacman chasing pixelated ghosts through a digital darkness but, now, as we tumble headlong into virtual realities, ethical voids are being filled by the same ghosts humanity created IRL.

As a kid I sank an embarrassing amount of time into World of Warcraft online, my elven ranger was named Vereesa Windrunner and rode a silver covenant hippogryph. (Tl;dr: I was a cool chick with a bow and arrow and a flying horse.)

Once I came across two other players and we chatted – then they attacked, took all my things and left me for dead. I was mad because walking back to the nearest town without my trusty hippogryph would take a good half hour.

Gamers call this behaviour “griefing”; using the game in unintended ways to destroy or steal things another player values – even when that is not the objective. It’s pointless, it’s petty, in other words it’s being a huge jerk online.

The only way to cope with that big old dose of griefing was rolling back from my screen, turning off the console and making a cup of tea.

But gaming is changing and virtual reality means logging off won’t be so simple – as exciting and daunting as that sounds.

500 years ago, or whenever Pacman was invented, gaming largely amounted to you being a little dot moving around the screen, eating slightly smaller dots, and avoiding slightly larger dots.

Game developers have endlessly fought to create more realistic, more immersive, and more genuine experiences ever since.

Gaming now stands as its own art, even inspiring seriously good television (try not to cry watching Last of Us) – and the long awaited leap into convincing, powerful VR (virtual reality) is now upon us.

But in gaming’s few short decades we have already begun to realise the ethical dilemmas that come with a digital avatar – and the new griefing is downright criminal.

Last year’s Dispatches investigation found virtual spaces were already rife with hate speech, sexual harassment, paedophilia, and avatars simulating sex in spaces accessible to children.

In the Metaverse also – which Mark Zuckerberg hopes we will all inhabit – people allege they were groped and abused, sexually harrassed and assaulted.

In one shocking experience a woman even claimed she was “virtually gang raped” while in the Metaverse.

So how can we better prepare for the ethical problems we are going to encounter as more people enter this brave new world of VR gaming? How will the lines between fantasy and reality blur when we find ourselves truly positioned in a game? What does “griefing” become in a world where our online avatars and real lives overlap? And why should we trust the creepy tech billionaires who are crafting this world with our safety and security?

The Ethics Centre’s Senior Philosopher and avid gamer Dr Tim Dean spent his formative years playing (and being griefed) in the game, Ultima Online – so he’s just the right person to ask.

Let the games begin

VR still requires cumbersome headsets. The most well known, which was bought by Facebook, is called Oculus but there are others.

Once you’re strapped in, you can turn your head left and right and you see the expansive computer generated landscape stretching out before you.

Your hands are the fiery gauntlets of a wizard, your feet their armoured boots, you might have more rippling abs than you’re used to – but you get the point, you’re seeing what your character sees.

The space between yourself and your avatar quickly closes.

Tim says, there is that kind of “verisimilitude” which feels like you’re right there – for better or for worse.

“If you have a greater sense of identity with your avatar, it magnifies the feelings of violation,” he said.

Videogames were once an escape from reality, a way to unshackle to the point you can steal a car, rob a bank and even kill, but Dean suggests this escapism creates new moral quandaries once we become our characters.

“A fantasy can give you an opportunity to get some satisfaction where you might not otherwise have,” he said.

“But also, if your desires are unhealthy – if you want to be violent, if you want to take things from people, if you enjoy experiencing other people’s suffering – then a fantasy can also allow you to play that out.”

Make your own rules

Dean has hope, despite the grim headlines, saying “norms emerge” in these virtual moral voids and norms begin to form between users – or as they used to be called; “people”.

“Where there are no explicit top down norms that prevent people from harming or griefing other people, sometimes bottom up community norms emerge,” he said.

Dean’s PhD is about the birth of norms: the path from a lawless, warring chaos to self-regulating society because humans learned about the impacts they were having on one another.

It sounds promising, but when Metaverse headsets begin at $1500 you’ll quickly realise the gates to the future open only to the privileged, often wealthy white men become the early adopters.

Mark Zuckerberg seems to have the same concerns.

Metaverse proposed a solution in the form of a virtual “personal bubble” to protect people from groping… but aside from feeling very lame to walk around in a big safety bubble, it demonstrates that there’s no attempt to curb the bad behaviour in the first place.

The solution, in the real world, to combat abuse has typically come in the form of including people from diverse backgrounds, more women, more people of colour, all sharing in the power structure.

For virtual reality – now is the time to have that discussion, not after everyone has a horror story.

Dean thinks there are a few big questions yet to be answered:

Will people, en masse, act horribly in the virtual world?

How do you change behaviour in that world without imposing oppressive rules or… bubbles? Who gets to decide what those rules are? Would we be happy with the rules Meta comes up with? At least in a democracy, we have some power to choose who makes up the rules. That’s not the case with most technology companies.

And how does behaviour in the virtual world translate to our behaviour outside of the virtual world?

Early geeks hoped the internet would be a virtual town square with people sharing ideas – a vision that missed racist chatbots, revenge porn and swatting.

Dean hopes the VR landscape might offer a clean slate, a chance at least to learn from the past and increase people’s capacity for empathy.

“We can literally put on goggles and walk a mile in someone else’s shoes,” he said.

So maybe there’s hope yet.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Science + Technology, Society + Culture

The terrible ethics of nuclear weapons

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Science + Technology

MIT Media Lab: look at the money and morality behind the machine

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Science + Technology

Age of the machines: Do algorithms spell doom for humanity?

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Science + Technology