Money talks: The case for wage transparency

Money talks: The case for wage transparency

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + Leadership

BY Jack Derwin 30 JUN 2022

Sex, death, politics, money. No matter how much some things change, some taboos stubbornly live on. But when it comes to the matter of wages, our silence on the subject is only hurting ourselves.

As we’ve discussed, radical transparency – when implemented with care – can help build trust and accountability. This openness not only assists in identifying where we stand but also in charting the necessary path forward.

Yet while the public conversation around wage inequality has never been louder, we remain remarkably tight-lipped on the topic of pay. Opening up a dialogue about our salaries may just be the first step to putting us all on equal footing.

A raw deal

While workplace discrimination exists in many forms, the gender pay gap has become the most identifiable indicator of its prevalence in the workplace.

Right now in Australia women are paid nearly 14% less than men, according to government data – slightly above the average recorded across other OECD nations. While over time the difference is narrowing, progress is predictably slow across the developed world.

This may partly be attributed to a lack of accountability among some businesses. During this year’s International Women’s Day (IWD) for example, the rhetoric of British businesses was challenged by a Twitter bot programmed specifically for the occasion.

Any tweet celebrating IWD from an official corporate account was met with an automated response, publishing the official pay gap at that specific company. The difference – often a percentage in the double digits– painted a bleak view of the current state of affairs.

But more importantly, the stunt quantified the issue at an organisational level and provided a useful reminder: by measuring the problem, we can manage it. By bringing public attention to specific cases, the bot held workplaces accountable on a case by case basis and drew a line in the sand.

Indeed, employment experts suggest this kind of open wage dialogue could be an important weapon in fighting wage inequality. Government research highlights that within Australian organisations where there is wage transparency, the gender gap is narrowing by 3.3% per year. While this may be due to many factors, transparency is at least helpful in tracking improvement over time.

Hush money

The argument for greater openness is increasingly being recognised. Last year in Australia, the then Federal Opposition proposed outlawing pay secrecy clauses which explicitly prevent colleagues from discussing their pay packets.

In the financial services sector, clauses have historically been commonplace with one study estimating women at Australia’s largest bank are collectively being paid $500 million less than their male peers. The industry union has used such figures to rally for greater transparency and amid several industrial cases in which employees were actually dismissed for disclosing their pay.

The campaign has worked. Australia’s big four banks – ANZ, NAB, Westpac and the Commonwealth Bank – all recently scrapped their privacy clauses. Staff can now choose to discuss their pay packets should they wish without fear of facing retribution from their employer. Given the four organisations employ more than 160,000 Australians between them, it’s no small achievement.

Global view

Many countries around the world, including the United States and United Kingdom, have already nullified these provisions and have been clear in justifying why. The executive order from the Obama administration doing so in 2014 for example linked them to employer discrimination and market inefficiency.

But governments are also taking additional steps to proactively open up the conversation around remuneration. Many, including the UK, now require publicly-listed companies and other employers to publish the average pay ratio between CEO and worker.

Similar laws in Australia, in operation since 2012, explicitly do so on the basis of closing the gender wage gap. In fact, around half of all OECD nations have comparable mandates.

Germany has gone one step further. Female workers can not only find out how much their male colleagues are making but are now also permitted to demand the median wage of a group doing the same job.

Notably, some corporations are even using transparency to attract talent in an extremely tight labour market. PWC became the first big consultancy firm in Australia to publish its own pay bands in a bid to find the best people, although It’s worth pointing out the breadth of each band does little to specific pay per job.

More to be done

While greater transparency is helping to hold feet to the fire, it is clear that the initiatives described above are just a start.

A recent OECD report for example points out that we’re far from anything resembling ‘radical transparency’. While around half of the 38 member nations publish company-wide figures, more can be done to turn information into meaningful action.

For example, at the moment only a limited number of companies are required to report any pay data at all, with most countries drawing the line at large publicly-listed entities. So too is the pay data these organisations provide often limited in nature.

Annual auditing of the information published and a strong independent regulator to oversee it are just two important future steps prescribed by the OECD. Any requirements need to be legally enforceable, it argues, and there needs to be penalties for those found flaunting the rules – as is already the case in Iceland.

Without these additional changes, workers aren’t actually in a better position to negotiate. Particularly when they come from groups that have historically been marginalised in the workplace. Instead it can mean they’re more acutely aware of their disadvantage with little practical means to address it.

The Norway Experiment

This conclusion is backed up by the experience of Norway, which has been trialling a form of radical transparency for years.

Norway’s tax office annually publishes every individual’s income on the public record. It also reveals the value of their assets and how much tax they paid. The idea is that in a country that leans socialist, trust must be maintained in the taxation system that supports it.

The experiment has largely been fruitful. Norway has a strong tradition of collective bargaining and a gender gap that is ranked third smallest in the world.

Naturally it’s difficult to conclude what came first: Norway’s relatively equal pay or the country’s unusual wage transparency. In all likelihood, these factors are mutually dependent.

However the Norwegian experiment also reveals the pitfalls of radical transparency and the natural threat it poses to personal privacy.

In 2001, the country digitised its records, making them instantly searchable from any personal computer. While records had been available for decades, this move eliminated the need to line up and leaf through the single book available in every municipality.

This digitalisation may have been a step too far. A study by the American Economic Association (AEC) found that the happiness of Norwegians actually became more correlated to their income level after 2001 by a factor of almost 30% – but only if that citizen had good internet access.

The hypothesis shared by the AEC is that those who could easily look up the incomes of their colleagues, friends and families, did so. Those who discovered their own incomes paled in comparison seem to have suffered emotionally because of it, even in the relatively equal nation of Norway.

In other words, the old axiom that ‘comparison is the thief of joy’ rings true. Significantly, in 2014, Norway made searches a matter of public record as well, making it known who had searched for your income. The volume of queries residents made on their neighbours fell immediately by 90% – making for presumably a far happier nation.

Lesson learned

The Norwegian experience paints a cautionary tale around the excesses of radical transparency. Specifically, it shows that wage data that is instantly available and that personally identifies individuals without their consent can do more harm than good. Careful protections will be required to ensure that workers are able to protect their own privacy.

More broadly, the examples suggest that information alone is not sufficient to prevent discrimination in the workplace. While it can serve as an important tool in bridging the gender wage gap for example, it needs to be carefully deployed along with other policies to measure progress, empower staff, and punish employers that deliberately mislead or discriminate.

Yet greater transparency clearly does have an important role to play. It helps keep workers informed of where they stand in relation to their colleagues. Making this kind of data public also makes sense that differences in pay need to be quantified before they can be rectified. Certainly, it helps enable countries to measure their progress to date and the effectiveness of their actions going forward.

Ultimately transparency is not a silver bullet, rather it is a means to an end. Properly informed and equally empowered, workers can finally begin to level the playing field.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Big thinker

Society + Culture, Business + Leadership

Big Thinker: Ayn Rand

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships

Game, set and match: 5 principles for leading and living the game of life

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Business + Leadership

Teachers, moral injury and a cry for fierce compassion

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Sylvie Barbier and Rufus Pollock on failure and fostering a wiser culture

BY Jack Derwin

Jack is a Sydney-based writer and journalist, specialising in business and economics. His reporting has appeared in the Sydney Morning Herald, the Australian Financial Review, Business Insider and the Asahi Shimbun among others.

Based on a true story: The ethics of making art about real-life others

Based on a true story: The ethics of making art about real-life others

Opinion + AnalysisRelationshipsSociety + Culture

BY Joseph Earp 29 JUN 2022

In October of 2021, The New York Times published a long article called ‘Who Is The Bad Art Friend?’, a story of kidney donations, poetic license, and vicious authors falling over one another to write damning words about those they publicly called their friends. Within hours of it hitting the internet, it had become the story of the day. And then the day after that. And then the day after that.

The thrust of ‘Who Is The Bad Art Friend?’ is simple. Seven years ago, an aspiring author named Dawn Dorland donated a kidney, a selfless act motivated – at least on first glance – by pure charity. Rather than let this act remain anonymous, Dorland instead posted about it frequently across the internet, particularly in a digital writer’s group she was part of. One of the members of that group, Sonya Larson, began murmuring to other authors about what she saw as Dorland’s shameless desire for attention, turning Dorland and her donation into a particularly damning punchline.

But rather than keep her takedowns to private messages, Larson wrote a not-so-veiled short fiction story about Dorland and her perceived bent towards self-celebration. Titled ‘The Kindest’, the story draws heavily on Dorland’s life, and turns her into a warped and twisted version of herself; too arrogant and self-involved to behave in a genuinely charitable way, motivated only by pride and sickening grandiosity. Flash forward a few years, and Dorland had launched legal action against Larson over the story, a protracted battle that serves as the climax for ‘Who Is The Bad Art Friend?’

There is a good reason that the fallout between the two writers so firmly captured the attention of the internet. It’s not just the tone of ‘Who Is The Bad Art Friend?’, the writing is unabashedly gossipy, filled with back-and-forths between Larson and Dorland that are laced with enough invective to make your toes curl. It’s that the story provided an opportunity for the internet to agonize over a very old argument, given new life in the era of streaming and a fixation on true crime: who has the right to tell another’s story?

This Is Your Life

We tend to believe that we are the authors of our own life story – that we have an essential and inalienable hold over our own narratives. There is nothing, so one cultural myth goes, as sacrosanct and personal as our identity.

As such, those who adopt this view on identity consider the act of turning another human being’s life into art to be one steeped in ethical conundrums: an issue of consent and privacy, where the wishes of the subject must be valued over the artistic decisions of the author.

These are the people who took Dorland’s side in the ‘Who Is The Bad Art Friend?’ argument. They are also the people who have a bone to pick with the recent glut of “ripped from the headlines” media content, from Hulu’s Pam & Tommy, a fictionalised version of the media fallout after the release of Pamela Anderson’s sex tape, to Inventing Anna, a series following the rise and fall of Anna Delvey (real name Sorokin), a socialite who scammed her way through America’s upper class.

In each of these cases, a real-life story – with, in many cases, real-life victims – has been shaped into fiction, often without the subject’s consent.

Anderson herself pushed against Pam & Tommy being made, while Sorokin wrote an angry letter about the series from her jail cell.

But to believe that you – and only you – can tell your own story is to believe in a shaky foundational premise. Such an argument rests on the idea that each of us is hermetically sealed away from the world, and hold important and relevant insight into ourselves that no others hold.

It is the case that we know certain things about our lives that others do not. But we are embedded in a web of social relations, and in the imaginations and minds of all those we encounter. We are not, in fact, the faultless experts on ourselves. Our personality, such as it is, is shaped and tested in the minds of those who receive us. The delineations between “my story” and “your story” or “our story” are shakier than it might first appear. We are constructed by the world, not sat in opposition to it.

Why This Argument? Why Now?

People’s sacrosanct belief in the importance of their own personal identity – treated as though our narratives about ourselves are delicate pieces of crystal we hold close to our chests, too fragile to let anyone else hold, is tied to a growing retreat from structural and systemic issues, and an embracing of personal ones. The ultimate social currency is often not based in the story of many, but the story of one. “I am me, and nobody else could be me, and for that reason, nobody else could tell my story but me.”

On the whole, the creative scope of the streaming giants, particularly Netflix, and major Western movie studios, has changed tremendously, from the cultural to the individual. Adam Curtis, the documentarian, has pointed this out, bemoaning the fact that there are few artists looking to describe how life right now feels. In America, Australia and the UK in particular, mainstream creatives have limited desire to capture any experience that expands beyond very particular lived ones, that are presented as isolated, and unique.

The theorist and philosopher Christopher Lasch covered this decades ago, in his groundbreaking work The Culture of Narcissism. He addressed what he saw as a tendency to go inwards: faced by a souring political climate, Lasch argued Americans had traded a hope for big change, with a fixation on smaller, more intimate and cosmetic shifts.

It is no surprise then that, though arguments around the ethics of storytelling have been waging for decades, they have been given new poignancy by the frequency of creative projects that fixate on only one life, and the increasingly popular belief that we are alone, and lonely, and utterly unlike even those from our same cultural and class background.

The beauty of art is that it need never be blinkered in this way. I am not advocating for only one type of art, the cultural instead of the personal – and I don’t believe that Curtis or Lasch are either. That’s one way of falling into precisely the artistic stalemate we find ourselves in. It’s not hopping from one mode of storytelling to another, it’s mixing the two, providing a rich, mainstream creative palette.

In fact, the problem is a creative fixation, one that has begun to dominate swathes of cultural discourse and entertainment. A generation of storytellers have settled themselves into a rut, hashing the same old beats over and over, telling stories with the same foundational premise – we are not like each other. In turn, that means our questions about so much mainstream art are becoming repetitive, the discourses surrounding ‘Who Is The Bad Art Friend?’ and Pam & Tommy and Inventing Anna just familiar talking points shot weakly through with a desperate, failing dose of adrenaline.

The question, asked over and over again, is: “Who can tell my story?” But perhaps we should ask why we even consider it “my” story in the first place.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships

The twin foundations of leadership

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

What ethics should athletes live by?

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Tim Soutphommasane on free speech, nationalism and civil society

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

It takes a village to raise resilience

BY Joseph Earp

Joseph Earp is a poet, journalist and philosophy student. He is currently undertaking his PhD at the University of Sydney, studying the work of David Hume.

Beyond consent: The ambiguity surrounding sex

Beyond consent: The ambiguity surrounding sex

Opinion + AnalysisRelationships

BY Eleanor Gordon Smith 24 JUN 2022

In April 2021, partly in response to a series of high-profile sexual assault allegations, the Commonwealth government funded a set of educational videos about sexual consent. Safe to say, they did not do the job.

There was the infamous milkshake video, in which a girl smears ice cream on her partner’s face with a devious grin; one in which a taco is distinguished from a person by the fact that a taco cannot have preferences, and one set at a swimming pool, in which the desire to go for a swim is compared to the desire (or not) to have sex. The videos were condemned in ringing terms by educators and activists – they were “problematic”, an insult to students’ intelligence, or too flippant for the gravity of the subject.

Anyone who has sat through workplace or educational training about harassment and sexual boundaries knows what a difficult feat these videos had to pull off. It’s hard to talk about sex, because sex is not one thing – even between partners, much less across the population. This makes it hard, in turn, to talk about sexual ethics — there are many more ethical lenses available than the ethics of consent.

Sex ranges from the grave and the intimate to the flippant and the casual, from the depths of taboo to the frothiest of frivolities, from power and domination to play and healing, from authentic self-expression to pantomimed degradation. It is such a chimerical experience that it’s no wonder we struggle to talk about its morality in clear and unambiguous terms. No wonder our sexual ethics education materials can fall into a kind of “uncanny valley” – videos depicting wooden interactions between characters who at once are blithely unaware of sexual norms and calmly receptive to learning them, or oddly literal exchanges that feel like they’re discussing an experience almost, but not quite, entirely unlike sex.

How can sex be so operatic and so stone quotidian, so universal and so private, so dangerous and so familiar?

Why, when our sexual experiences are so many and so varied, do we hope that an ethics of consent will be able to accommodate them all?

If we wanted a more holistic approach to sexual ethics and education, which moral frameworks would we turn to?

Time was, if you wanted an ethics of sex, the psychoanalysts were the place to turn. Freudian analyses of desire located it squarely in the individual and the underbelly of their consciousness. Desire was seldom understood as something about which one could ask the questions of justice – Is it fair? Who deserves it? – or as a candidate for political analysis. But beginning in the 20th Century, a feminist perspective rejected this picture. Feminist philosophers and legal scholars like Catherine MacKinnon and Andrea Dworkin argued that desire was both an expression of and a means of enforcing the prevailing hierarchies of power. In Mackinnon’s “Pleasure Under Patriarchy”, she quotes poet Adrienne Rich’s Dialogues: “I do not know who I was when I did those things, or whether I willed to feel what I had read about”.

Once the questions of justice had been asked around sex – once it was pointed out that power and hierarchy do not stop at the door to the home or the bedroom – there emerged uneasy questions about how sexual unfairness could create demands of sexual fairness: for instance, does anyone have a right to sex? (This question has been explored by Oxford Professor Amia Srinivisan at length). Or can a person have a moral complaint when over and over again, they are rejected for sex; unable – through the aggregation of other people’s choices – to access an experience that everyone else says is one of life’s central joys?

Sexual desire has long discriminated along racial and disability lines – as Srinivasan notes, Asian men on dating apps or disabled people are frequently told to their faces that they are instantly rejected as prospective sexual partners because I would never sleep with someone like you. How can we make sense of the utter rigidity of the rule that nobody should have sex with anyone they don’t want to – alongside the possibility that those choices en masse enact a prejudice that each of us might individually deny? One more mystery for the ethics of sex; for the challenge of bringing justice to something as fraught as desire. As Srinivasan so memorably writes: “There is nothing else so riven with politics and yet so inviolably personal.”

In this morass of ethical grey, the concept of consent seemed to promise some black-and-white. We might not know the full list of our sexual rights, but an ethics of consent at least clearly names the sexual wrongs. The centrality of consent to sexual ethics is in fact a relatively recent development; the concept gained traction in the 1980s, at roughly the same time as the autonomous individual became the main character of political analysis. It was not long before then that “informed consent” was still a foreign notion in healthcare ethics, and that rape of a sex worker was often understood not as a violation of consent, but as theft of services.

Perhaps consent education reaches for simple metaphors like milkshakes, tacos, or cups of tea because an ethics of consent is simple – so simple we can say it in the familiar truism: “No means no”. But the trouble with centering consent in our sexual ethics is that it risks confusing ‘not-capital-B-Bad’ with ‘good’. Plenty of consensual sex is also cruel, harmful, selfish, painful, alienating, or subordinating.

Consensual sex is not necessarily ethical, nor even necessarily good. By treating non-consensual sex as the primary case about which to do sexual ethics – the jumping off point for our analysis and education – we risk introducing young people to sexual morality primarily through the category of wrong and how to avoid it, instead of through the lens of sexual joy and how to share it. Sex can be a way to connect with one another, to know, to be vulnerable, to give, to reveal, to trust – the intelligibility of aspiring to sex like this can be lost when the highest aspiration of our sexual ethics is “getting consent”.

By treating non-consensual sex as the primary case about which to do sexual ethics – the jumping off point for our analysis and education – we risk introducing young people to sexual morality primarily through the category of wrong and how to avoid it, instead of through the lens of sexual joy and how to share it.

One of the central tasks of an ethical life is to distinguish between the realm of duty – what can be demanded of us, and the realm of benevolence, what we can freely give, and to realise that the person who thinks only about their duties is in some ways a moral miser. An ethics of sex which prioritises duty by emphasising consent and permission can accidentally obscure the possibility of an ethics of benevolence – one which would not stop after asking what we owe to one another, but would carry on, asking how we might help them flourish.

To live an ethical life is more than avoiding wrong – how strange it would be to forget that in our most vivid encounters with others.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

How to respectfully disagree

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

I’m really annoyed right now: ‘Beef’ and the uses of anger

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships

Unconscious bias: we’re blind to our own prejudice

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

The danger of a single view

BY Eleanor Gordon Smith

Eleanor Gordon-Smith is a resident ethicist at The Ethics Centre and radio producer working at the intersection of ethical theory and the chaos of everyday life. Currently at Princeton University, her work has appeared in The Australian, This American Life, and in a weekly advice column for Guardian Australia. Her debut book “Stop Being Reasonable”, a collection of non-fiction stories about the ways we change our minds, was released in 2019.

We are on the cusp of a brilliant future, only if we choose to embrace it

We are on the cusp of a brilliant future, only if we choose to embrace it

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + LeadershipPolitics + Human Rights

BY Simon Longstaff 22 JUN 2022

Speaking a couple of days after the 2022 Federal Election, renowned Australian journalist, Stan Grant, noted that although the election of the Albanese government had been a moment of national ‘catharsis’, it was more difficult to discern in the result a commitment to a clear, positive direction for the nation. In that sense, the future shape of Australia remained an ‘open question’.

This was not to deny that the Australian electorate seemed to express, through their vote, a few clear preferences: an end to the debilitating ‘climate wars’, higher standards of integrity in federal politics and more generally, a preference for a more diverse and inclusive form of representation in our national parliament and government.

There is every reason to believe that these expectations will be met. Indeed, one might be encouraged to hope for something more. For example, it was remarkable that the first utterance of Prime Minister Albanese, on claiming victory, was to promise a referendum to enshrine in the Constitution an Indigenous ‘Voice to Parliament’ as called for in the Uluru Statement From The Heart. The surprise in this was that this issue had barely been mentioned during the election campaign – yet had clearly loomed large in the mind of the new PM.

So, what else might we aim to achieve as a democratic nation endowed with the most fortuitous circumstances of any nation on earth? Yes, despite the current ‘doom and gloom’, we are on the cusp of a truly brilliant future – if only we choose to embrace it.

We have everything any society could need: vast natural resources, abundant clean energy and an unrivalled repository of wisdom held in trust by the world’s oldest continuous culture supplemented by a richly diverse people drawn from every corner of the planet. However, whether this future can be grasped depends not on our natural resources, our financial capital, or our technical nous. The ultimate determinant lies in our character.

Three forces can shatter our path to prosperity. First, enemies from without who seek to exploit our grievances and divide our nation into warring factions. Second, a collective fear of the unknown and a lack of trust in those who would lead us there. Third, a lingering, persistent doubt about the legitimacy of a society that violently dispossessed the first peoples of our continent.

Each of these threats can be neutralised – if only we have the collective will and the courage to do so. With this in mind, I have outlined below a set of core, national objectives that I think would secure the endorsement of a vast majority of Australians. It is the realisation of these objectives that will unlock the brilliant future that is available to all Australians.

In five years, we can fashion a society that is at ease with itself and its place in the world. We can have sown the seeds out of which will grow a universal sense of belonging – a gift bestowed by First Nations people who have only ever asked for respect, truth and justice. That sense of unfettered connection, informed by an Indigenous understanding of country that has grown over time immemorial, will be the glue that binds us into one people of many parts. Once established and reinforced, nothing will dissolve that bond.

In five years, we can grow the confidence to embrace radical change – confident that no individual or group will be asked to bear a disproportionate burden while others take an unfair share of the gains. Our commitment to a broadly egalitarian society will move from myth to reality. While we may not all rise to equal heights, no one will be left to fall into the depths of neglect or obscurity. This will allow us to be brave, to take risks and to harvest the rewards of doing so.

In five years, we can be better led. Confidence can be restored in our governments – that they will truly honour their democratic obligation to act solely in the public interest – whether in their use of public resources or in the policies and practices they adopt.

In five years, the aged, the sick and infirm should be cared for by a workforce who are properly valued and rewarded for their support of the most vulnerable.

In five years, all Australians should have a genuine opportunity to make a home for themselves in affordable, secure accommodation.

In five years, everyone should feel more safe and secure in their homes, their workplaces, their cities and towns.

In five years, a confident Australia can build and reinforce enduring alliances with nations who share our desire to live in a just and orderly world free from the heavy yoke of authoritarian governments.

All of this is possible. For the most part our physical and technical infrastructure is world class. Our ethical infrastructure could be better. We need to invest in this area – confident that in doing so we will unlock both social and economic benefits of staggering proportions. As Deloitte Access Economics has estimated, a mere 10% increase in the level of ethics in Australia would lead to an increase in GDP of $45B (yes, billion) every year – not through some kind of ‘magical effect’ but as a direct consequence of the increased trust that better ethics would create.

Do this and we can embrace the brilliant future that beckons us.

With your support, The Ethics Centre can continue to be the leading, independent advocate for bringing ethics to the centre of life in Australia. Click here to make a tax deductible donation today.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Health + Wellbeing

David Pocock’s rugby prowess and social activism is born of virtue

Opinion + Analysis

Science + Technology, Business + Leadership, Society + Culture

AI might pose a risk to humanity, but it could also transform it

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

After Christchurch

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Are diversity and inclusion the bedrock of a sound culture?

BY Simon Longstaff

Simon Longstaff began his working life on Groote Eylandt in the Northern Territory of Australia. He is proud of his kinship ties to the Anindilyakwa people. After a period studying law in Sydney and teaching in Tasmania, he pursued postgraduate studies as a Member of Magdalene College, Cambridge. In 1991, Simon commenced his work as the first Executive Director of The Ethics Centre. In 2013, he was made an officer of the Order of Australia (AO) for “distinguished service to the community through the promotion of ethical standards in governance and business, to improving corporate responsibility, and to philosophy.” Simon is an Adjunct Professor of the Australian Graduate School of Management at UNSW, a Fellow of CPA Australia, the Royal Society of NSW and the Australian Risk Policy Institute.

It’s time to talk about life and debt

It’s time to talk about life and debt

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + Leadership

BY The Ethics Centre 17 JUN 2022

It’s no secret that things are getting more expensive.

Over the last few months Google searches for “the cost of living” have increased by 10 fold, and it’s no surprise. The price of vegetables has increased by almost 30%, some used cars are up over 45%, petrol is at the highest rate in history, and a string of interest rate rises have hit for the first time in more than a decade. Millions of Australians are feeling the financial stress of keeping a roof over their head, keeping the lights on and putting food on the table. So what’s going on?

The answer is… it’s complicated. We have found ourselves in the perfect storm of frequent extreme weather events, the effects of climate change on crop production, pandemic-affected supply chains, and a war in Ukraine. And as a result of all of these factors which are very much out of our control, we are experiencing rocketing inflation and a cup of coffee will now set you back over $5. So how can young people, whose wages have been stagnating for years weather this storm and better understand their finances?

Let’s talk about debt

For as long as we have ascribed value to little disks of metal, we’ve been conditioned to believe that accumulating debt is a bad thing, and that we should aspire to have money squirrelled away for a rainy day. After all, the majority of us are paying off some form of debt whether it be a mortgage, a business loan, or a student debt – so owing money certainly shouldn’t be taboo.

Which is why our latest podcast, Life and Debt says it’s time we stopped demonising debt and started thinking of it as a part of life.

Created by the Young Ambassadors from our Banking and Finance Oath (The BFO) initiative, this four– part podcast series takes a deep dive into debt, what role it has in our lives and how we can make better decisions about it. According to Young Ambassador, Cameron Howlett we need to rethink our relationships with being in the red. “We wanted to encourage people to think, discuss and engage with the topic because if you’re uncomfortable with debt, you’ll never really have a healthy relationship with it.”

Howlett hopes the podcast will encourage a more nuanced discussion about debt, “we all have some good experiences and bad, but what we have found consistently was that we were all a bit nervous about debt.” The series, which features financial advisors, journalists, finfluencers, psychologists and historians hopes to debunk the shame and stigma around debt especially for younger listeners. Cameron continues, “we want to get people from that step of being too terrified of debt or credit to be able to think whether or not it’s right for them”, so how can we be a little more discerning when it comes to different types of debt?

“If you’re uncomfortable with debt, you’ll never really have a healthy relationship with it.”

The good the bad and the ugly debt

During the pandemic, we all did our share of online shopping. Buy now, pay later services made it easy for us to get that instant gratification hit that comes with receiving parcels in the mail, without the ensuing depression that results from looking at one’s negative bank balance. These services posted huge profits during the pandemic, and because they’re so easy to set up and use, people are now using apps like AfterPay and ZipPay to purchase everything from a new outfit for the weekend, to groceries, and childcare. Unlike credit cards and banks, Buy now, pay later companies don’t ask any questions about whether their customers can actually afford to make the repayments, and as a result a lot of young people are racking up thousands of dollars in debt using these financial services.

So what exactly is good debt and bad debt, and how can we differentiate between the two?

According to Iqra Bhatia, a Young Ambassador from the Banking and Finance Oath initiative, “attitudes towards debt are changing, young people need to educate themselves more on debt and be aware of the resources available”. Instead we need to shift our thinking, “Afterpay is not that different from credit cards – it’s essentially the credit card of our generation.”

“Attitudes towards debt are changing, young people need to educate themselves more on debt and be aware of the resources available.”

It’s not all doom and gloom

It’s clear we need to start understanding money from a younger age. While lessons in financial management traditionally consisted of a few pointers offered by parents at the dinner table, we are now starting to see financial literacy programs introduced in the high school curriculum. But more work needs to be done.

Debt is something that, at different points throughout all our lives we will all encounter and take on, whether it be small, like agreeing to buy the next round at the pub, or a little more daunting like taking on a HECS debt at university or taking out a mortgage to buy an apartment.

Debt can be emotional, it can feel like you’re signing away a little piece of your freedom, but it can also be empowering and necessary. And debt is changing, we’re grappling with the buy now, pay later industry now, and what form debt will take over the next few years. Which is why it’s important to stay educated and in touch with our values so we can make decisions for our bank balances and our futures.

Life and Debt is available to listen to on Spotify and Apple Podcasts.

This podcast is a project from the Young Ambassadors in The Ethics Centre’s Banking and Finance Oath initiative. Our work is made possible by donations including the generous support of Ecstra Foundation – helping to build the financial wellbeing of Australians.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Business + Leadership

Repairing moral injury: The role of EdEthics in supporting moral integrity in teaching

WATCH

Business + Leadership, Climate + Environment, Science + Technology

How to build good technology

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

The dangers of being overworked and stressed out

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Measuring culture and radical transparency

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Uncivil attention: The antidote to loneliness

Uncivil attention: The antidote to loneliness

Opinion + AnalysisRelationships

BY Dr Tim Dean 14 JUN 2022

We have built ourselves a lonely world but there are ways to forge the genuine human connections that we all need to flourish.

We live in a strange world. Consider the skill that many of us have carefully cultivated over years of city living of actively ignoring other people around us while hoping that those people will actively ignore us in return.

Think about how you enter a lift in a busy shopping centre or an office building. Perhaps a quick glance at those already standing inside, a small shuffle to ensure you’re not standing too close to anyone else, a quick tap of the “open door” button to allow a latecomer to enter, a fleeting smile to acknowledge that they almost missed it, and then you diligently stare into space desperately hoping no-one starts a conversation. Some lifts even mercifully include little screens displaying the weather and news headlines that offer everyone inside a sink for their collective attention.

This is a textbook example of what the Canadian sociologist Ervin Goffman called “civil inattention”. This is our tendency to actively not engage with those around us while not ignoring them entirely.

Civil inattention enables us to ensconce ourselves in a protective bubble of anonymity even while we’re shoulder-to-shoulder with other people. It’s both a defence mechanism that prevents us from having to constantly expend social energy interacting with every individual we encounter while also being a social lubricant that allows millions of strangers to coexist in relative peace.

The price of this unwritten social contract of non-engagement is loneliness. Indeed, it’s easier to feel isolated and disconnected from others in the middle of a bustling city than it is in a small town.

And with the growth of high density living over the last several decades so too has loneliness spread, especially in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic. Loneliness was already prevalent prior to the advent social distancing and enforced lockdowns, but recent surveys have revealed a sharp increase, with over half of respondents reporting they have experienced loneliness during the pandemic.

Contrast the civilly inattentive world to the social world that our minds have evolved to expect. That is a world laced with rich social interaction, one where our very identities are interlaced with those around us. It’s a world that our ancestors dwelt in for thousands of generations, a world that shaped our minds, and one that only changed with the advent of high density living.

The anthropologist Lorna Marshall vividly described the intimate connectedness among one small-scale society, the Nyae Nyae !Kung people of the Kalahari desert.

“Their need to avoid loneliness, I think, is actually visible in the way families cluster together in their werfs and in the way people sit, often touching someone else, shoulder against shoulder, ankle across ankle. Comfort and security for them lie in belonging to their group, free from hostility or rejection,” she wrote.

This is the world where belonging is a given and it’s almost impossible to be alone. It’s the world that many modern folk seek out through social media, popular culture, the bustle of city life or even religion. These give the trappings of connectedness but they’re all ultimately based on illusion. What we yearn for is the opposite of loneliness: genuine connection.

The good news is that there are ways to build genuine connection. One way to do so is just by having better conversations.

You can think about Goffman’s civil inattention as being a mask of civility that we wear in public that presents the face that society expects us to have but also covers our deeper self. It’s a defence mechanism but it’s also a barrier to genuine connection.

We can see this in many of the conversations we have with friends and colleagues, where we’re expected to talk about how well we’re doing, about our successes and triumphs. This tendency is only amplified on social media, where we have even greater opportunity – and expectation – to curate a positive image or flex about our privilege (#blessed).

But to really connect with someone, we need to go beyond our respective masks to reach the whole person underneath, including their strengths and their vulnerabilities, their successes and their failures, their hopes as well as their fears. It’s in the mutual recognition that we’re all complex and flawed beings, often stumbling our way through life, that we can build genuine connection.

This doesn’t mean we should be opening up to strangers about our greatest blunders in a lift, but it does mean allowing ourselves to lower the mask a little at a time around friends, acknowledging some of our vulnerabilities and helping them to feel comfortable doing the same. It means asking questions about more than just what they did on the weekend or which footy team won or lost. It means asking how they felt about it, what they hope for, what they regret or what they learnt. And it means shutting up and really listening to them, withholding judgement and validating how they feel.

You might be surprised at how quickly a good conversation, one where you lower your mask even a little, can build a connection that is meaningful and lasting. Sharing a little of our deeper self and getting to know a little of others’ deeper selves can feel confronting, it can challenge societal norms of what polite conversations look like, but they are also one of the greatest – and easiest – antidotes to loneliness. I call it “uncivil attention”.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Truth & Honesty

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

What we owe our friends

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Would you kill one to save five? How ethical dilemmas strengthen our moral muscle

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Why morality must evolve

BY Dr Tim Dean

Dr Tim Dean is Philosopher in Residence at The Ethics Centre and author of How We Became Human: And Why We Need to Change.

Meet Joseph, our new Fellow exploring society through pop culture

Meet Joseph, our new Fellow exploring society through pop culture

Opinion + AnalysisRelationshipsSociety + Culture

BY The Ethics Centre 7 JUN 2022

From The Matrix to Euphoria, writer, philosopher and poet Joseph Earp has profiled some of the greatest philosophers, TV shows, films, music and pop culture moments to date, discussing what they can tell us about ourselves and the world.

Which is why we’re excited to share we’ve recently appointed Joseph as an Ethics Centre Fellow. Currently undertaking his PhD at The University of Sydney, studying the work of David Hume, we sat down with Joseph for a brief get-to-know-you chat to discuss ethics, his favourite philosophers, and the role of pop culture in society.

Tell us, what attracted you to becoming a philosopher?

You learn the language of institutional philosophy by reading it, and – as long as your financial and geographical circumstances allow for it – by studying it in an academic setting. But the central questions that drive philosophical work are innate to almost all people, regardless of academic study.

I am a pragmatist, so I don’t believe that philosophers hold insight that stretches beyond the understanding of those who haven’t studied the discipline. As philosophers, we are merely using a certain vocabulary to ask our questions. I grew to love that vocabulary in my late twenties through university study, under the guidance of my honours and PhD supervisor, Anik Waldow and those academics I studied closely with throughout my undergraduate degree. Most notably, these academics include Caroline West, who I believe to be one of our country’s most unique, inspired, and challenging thinkers – even and especially as I disagree with her – and David Macarthur. My study with these people is what drew me to being a philosopher in the strictest sense. But I think we philosophers are, thankfully, just doing what everyone else is doing.

Do you specialise in any key areas?

Generally, I write about popular culture, emotion, and virtue ethics, but my key area of specialisation is the philosophy of sex. I think that we sadly retain, in many cultures, a suspicion and fear of sex – one that infringes on our ability to self-describe and live our most flourishing lives.

I often think of a story about Pablo Picasso. Towards the end of his life, he was so rich and famous that he could draw any object in the world, whether it be a Ferrari or a mansion, and his drawing would be worth more than the object itself. He could sell a sketch of an object, and use the accrued capital to buy that object – which is a way of saying he could create changes by charting what he felt had already changed. It seems to me that’s the potential, and the potential harm, of philosophical thinking. We construct the world by calling it what we think it is, and for a long time, our views on sexuality have created a world that contains a lot of fear and sexual repression, both internally and externally maintained.

Your honours thesis focuses on emotional contagion. What place does emotion have when it comes to ethics?

Personally, I think it’s emotion all the way down when it comes to ethics, as with most things. David Hume is the philosopher that much of my work has operated in the framework of, and I agree with Hume that when we talk about “rationality” – a word that is sometimes conceived as being opposed to emotion – we are really just talking about a certain kind of emotional work.

What have you been working on this year?

One of the most profound experiences of both my intellectual and personal life has been connecting with a community of thinkers whom I met largely through my university work – all of them world-class philosophers, some of them write for, and work with, the Ethics Centre; and some of them no longer consider themselves strictly philosophers at all. In particular, Georgia Fagan, Danielle Turnbull, Finola Laughren, Eleanor Gordon-Smith, Grace Sharkey, Oscar Sannen, Mitch Flitcroft, Alexi Barnstone, Elle Lewis, Mitchell Stirzaker, Henry Barlow, Zach Wilkinson, Finn Bryson, and Henry Hulme.

All of these people have work that you can, and should, find online through an easy Google search, and work which I believe in every case benefits the world, and drives real change. What else is philosophy for? I am continually astonished by the intellect and bravery of these collaborators and friends. I consider myself useless without them. When I think about the real work that I have done this year, it is not anything I have written, but conversations with these people, and the ways I have learnt from them.

Do you have a favourite philosopher or writer?

Hume is the philosopher whose writing I know best, but I believe the thinker you apply the greatest amount of study to is usually the one who you have the strangest, most frequently frustrated relationship with. So my favourite – as in, the philosopher who serves as the background to almost all of what I think and do, and who I have the most uncomplicated connection to – is the pragmatist Richard Rorty. It’s Rorty who cuts through the chaff by asking, again and again, one of the simplest questions: what is the real-world application of our work? And it’s Rorty who tells us that we should remember we can make ourselves whoever we want to be.

Your writing covers a lot of tv series, films and music. Why is pop culture important?

Again – it’s Rorty. Rorty believed that social change isn’t led by philosophers, particularly those analytic philosophers who consider their work to be sorting through “falsehoods” and “truths”. For Rorty, philosophers inspire prophets and poets, and prophets and poets are the ones who do the work of change. That is, for me, the importance of pop culture. That form of art is guided by philosophical questions, and led by prophets and poets, and represents a way of understanding a culture and a vocabulary. It’s how lives are changed, and possibilities for self-description are opened up

What are you reading, watching or listening to at the moment?

The poetry collection The Cipher, by Molly Brodak, a writer who means a great deal to me; the pornographic film Corruption by perennial sadsack and visionary Roger Watkins, which I try to return to every month or so; and the song ‘Lark’ by Angel Olsen, often enough that I should probably take a break.

Let’s finish up close to home. What does ethics mean to you?

We all play the game of ethics, and we all want to play it better, and we’ll never play it well. That, in fact, is the joy – the trying, and the starting again.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Beyond consent: The ambiguity surrounding sex

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture, Relationships

Do we exaggerate the difference age makes?

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Are there limits to forgiveness?

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Health + Wellbeing, Society + Culture

I changed my mind about prisons

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

You won't be able to tell whether Depp or Heard are lying by watching their faces

You won’t be able to tell whether Depp or Heard are lying by watching their faces

Opinion + AnalysisPolitics + Human RightsRelationshipsSociety + Culture

BY Joseph Earp 2 JUN 2022

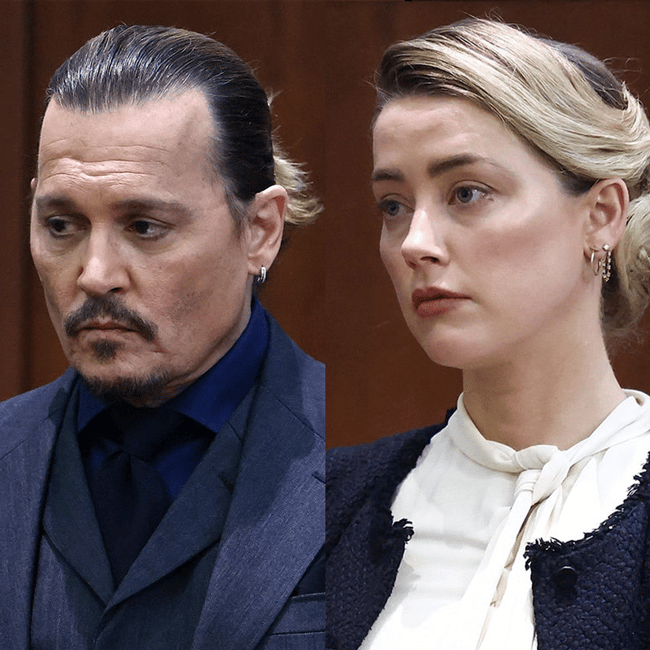

The Johnny Depp and Amber Heard defamation trial is now over.

Heard has been found guilty of defaming the actor with an op-ed she wrote – that did not name him explicitly – about being a survivor of domestic violence. Depp’s legal team too has been found guilty of defamation, but the amount that Heard has to now pay Depp is a much higher figure than he has to pay her.

The proceedings are done. But the media reaction to the trial – both from traditional outlets, and the deluge of posts about it crowding every single social platform like ants across an old plate of food – will linger.

This is because, in many circles, the all-too public spectacle has been treated like an unprecedented event. Pored over ad nauseum, it has been subject to endless thinkpieces, YouTube breakdowns, and Twitch streams. Twitter is awash with “fan edits”, compilations of carefully selected moments cut to the jaunty music usually associated with dance trends, or videos of dogs playing with each other in suburban backyards. There’s no use blocking keywords associated with it on social media. Videos still find a way to slip through, because the trial is everywhere.

This isn’t so surprising. The trial is on one level, a glimpse into the personal lives of the usually alien upper class. On another, it is shocking and disturbing enough – whichever side one takes – that it provides the vicious thrills that a culture which has become obsessed with true crime obsessively seeks out. This is all information, content. But how much of it do we need to make an informed decision about the outcome of the trial? And more than that, is this a useful kind of information? Where does it lead us? What does it give us?

The trial is foreign, it’s taboo, it’s ugly, and it’s glossy. What it isn’t, however, is quite as novel as it first seems.

Old Stories; New Faces

Much like the O.J. Simpson trial, or the proceedings against Lindy Chamberlain-Creighton, the Australian woman who claimed a dingo ate her baby, the Depp/Heard case is an example of a media-captivated society channeling abstract arguments through the lens of a high stakes legal proceeding, populated by faces that viewers have already developed complex parasocial relationships with. And, importantly, in each case, there has been an intense public scrutiny on how the figures in these cases should act – a fixation on their body language, their expressions, and the way they sound out words.

During the Simpson trial, the abstract arguments at play concerned race relations. Now, the tensions underlying the Depp/Heard trial are to do with what is sometimes referred to as our “post-metoo world”, a culture that has seen abusers reckoned with, and vast systems of deception that protect those abusers brought to light.

All of these court cases represented, and now represent, an opportunity for the public at large to discuss topics they might not normally have considered polite to bring up at the dinner table, or around the water cooler. “Is O.J. guilty?” was a way of saying, “tell me what you think about race and class in this country.” “Is Amber Heard a liar?” is now a way of saying, “what do you think abuse looks like? And what do we do about it?”

But there is at least one way that the Depp/Heard trial is involved with a trend that is breaking new ground. Unlike the Simpson trial, or the case against Chamberlain-Creighton, most viewers are watching the case through the internet. In turn, that means viewers have a unique ability to craft their own content about the proceedings, filtering key moments pulled from hours of footage through whatever pre-existing narrative they have constructed about the hero and the villain of this painful, and very sad story.

These content creators, who are often cutting together their videos in their spare time for no gain except rallying their audience around them, can watch over the trial’s footage as frequently as they like. They can scrutinize the same few seconds over and over; slow stretches of it down; freeze them in place.

In turn, that has turned a growing number of these amateur video essayists into amateur psychologists. A large subset of Depp/Heard content creators have come to believe that they can work out which of the players are lying by closely watching their expressions, unpacking their body language, and picking over the slightest tic, or absent gaze. For these sleuths, the case’s conclusion is as clear as Heard’s grimace, or the smile unfurling in the corner of Depp’s lips.

The Face Of A Liar

Those who seek to excavate the “truth” hiding beneath the trial by studying the body language and facial expressions of Depp and Heard start from a justifiable philosophical position. It was the philosopher Baruch Spinoza, a famous monist, who believed that every bodily state is underwritten by a mental state. For Spinoza, all things are of the one matter – variously called “nature”, or “God” by his intellectual interpreters. On this view, there is no distinction between any two substances, let alone a distinction between the way we hold ourselves, and what we think. The mind is the body, and the body is the mind.

From this starting point, it makes some sense to believe that the flesh might hold some insight into the secret thoughts and desires of two people who are very famous and very rich – and thus largely inaccessible, because nothing buys privacy like money and influence. Or, if not insight, then evidence gathered as post-hoc justification. Decisions as to guilt change based on a variety of factors – but they’re sometimes made early, and data can be gathered after those decisions have already been made, propping up pre-existing positions.

The mistake, however, is to generalise what these embodied states look like, and thus to generalise the emotional and mental states they are tied to.

There is, quite simply, no one way that all of us look when we lie, or are distressed, or happy. We are distinct in the way that we consider the world around us, and thus distinct in the way that we physically appear when we do.

Many of the “tell-tale signs” that get neurotically returned to, over and over again, on social media – Heard’s tone of voice, Depp’s drawl – could have any number of associated affective states, from anxiety, to pain, to yes, perhaps, the desire to lie. “It can be tough to accurately interpret someone through their body language since someone may feel tense or look uneasy for so many reasons,” said the therapist and author Dr. Jenny Taitz.

If we follow Spinoza, we will believe that our bodies and our thoughts are intertwined – but that’s not the same as saying the former will reveal the latter. These are slabs of affect, expressed both physically and mentally, but they are not as easily comprehensible as that makes them sound.

Indeed, psychological studies have proved for decades that none of us are skilled when it comes to weeding out those spinning “falsehoods”, and those not. A 2004 study of lying found that “agents of the FBI, the CIA and the National Security Agency – as well as judges, local police, federal polygraph operators, psychiatrists and laymen – performed no better at detecting lies than if they had guessed randomly.”

There is, after all, an immense social advantage to picking liars. If we could do it, and do it reliably, then that would be an invaluable skill, one we would expect to spread and be adopted across communities quickly. The fact that there is no dominant method of analysing the way our bodies twist and pose when speaking in itself speaks to the impossibility of using faces to get at what we mean when we talk about “the truth.”

Moreover, even most “body language experts” – an increasingly popular and media-saturated sub-set of pop psychologists, who have almost no science to back up their claims – admit that we need to get a baseline of our subject’s physical reactions before we can even attempt the fraught and mostly doomed work of trying to understand if they’re lying.

Which is to say, we need to at least know what people look like when they’re telling the truth before we can tell if they’re not. And we don’t know Johnny Depp, or Amber Heard, despite the illusion of closeness granted by social media. We don’t have enough data about how they move through the world, or what they look like when they do. How could we possibly guess at the motives and thoughts of utter strangers?

The Actors

Heard’s critics in particular have developed the line that she is a “performer”, going through the mere motions of grief and trauma – and not particularly well. They highlight a moment in which Heard appeared to pause while waiting for a cameraperson to snap a picture of her pained face, and another in which she seemed to flicker, composing herself for her next line as an actress on set would.

Of course, Heard is performing, on some level. But she is not performing in a way different to Depp. Though his defenders do not often note it, he too is signaling to the cameras, and to the jury – his smiles, and asides to his legal team, make that clear.

Nor, even, are these two distinct from the rest of us. We are all performing. We are social creatures, who have the ability to tell when we are being watched by others. Theory of mind, the term used to describe our understanding that other human beings see and think like we do, means that we can throw ourselves into the perspective of our observers. We do this constantly. It is part of what it means to have a body, and to be a person.

As philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre pointed out, we don’t even have to be actively watched to know that we could be watched. We carry with us the sense that we are what Sartre called a “thing in the world” – an entity that, at any time, could be stumbled across, and studied. As a result, we are always aware of ourselves, and how we might appear. Even when we are totally alone, we are never really alone. We are always with others – whether they’re flesh and blood observers, or ones we’ve made up in our head.

Where The Truth Lies

None of this has been an attempt to argue that Depp is telling the truth over Heard, or vice versa. It is not even a question of “truth”, as that word has been contemporaneously used.

The binary between the “real” and the “fake”, aggressively emphasised in media reactions to the trial, is itself overly simplistic, an outdated harbinger dangerously trickled down into the culture by analytic philosophy.

That is not to diminish the hurt, or the trauma, that clearly sits at the centre of the trial. That pain is real. That pain can be understood, but only when we look at the evidence in totality – the actual evidence, not the faces on the stand – and then causally tie it to certain parties.

We should, however, remember there is no objective state of affairs – no perfect place from which, like God, we can dispel the lies and embrace the world as it really is. The judge overseeing the Depp/Heard trial is not neutral. None of us are. At best, in this case as in so many others, we should, like the great pragmatist Richard Rorty, argue for ethnocentric justification for our claims, rather than tying them to a standpoint that sits outside of history, and belief, and bias. In doing so, we can embrace the changeability of our own positions – not on guilt and innocence, exactly, but the societal pressures that are so at play here – and examine them, seeing them as the flexible systems of thought that they are.

Throughout, however, we should remember that whatever we’re looking for when we hope to untangle a messy and painful relationship between two strangers who we will almost certainly never meet, it will not be found in their faces.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

Big Thinker: Kwame Anthony Appiah

Reports

Politics + Human Rights

The Cloven Giant: Reclaiming Intrinsic Dignity

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Ask an ethicist: How should I divvy up my estate in my will?

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Society + Culture

When our possibilities seem to collapse

BY Joseph Earp

Joseph Earp is a poet, journalist and philosophy student. He is currently undertaking his PhD at the University of Sydney, studying the work of David Hume.

Hype and hypocrisy: The high ethical cost of NFTs

Hype and hypocrisy: The high ethical cost of NFTs

Opinion + AnalysisScience + Technology

BY Dr Tim Dean 24 MAY 2022

When you hear news of a collage fetching US$69.3 million (AUD$92.1 m) at a Christie’s auction or a pixelated punk selling for US$23.7 million (AUD$31.5 m), you’d be forgiven for thinking that there’s a new and exciting art market on the rise.

But the multi-million dollar sales and media buzz around non-fungible tokens (NFTs) mask a more complex and troubling picture of a technology that is plagued by a host of ethical problems. These include rampant scams, exacerbating wealth inequality, a staggering environmental impact and, not least, the exploitation of the artists NFTs were supposed to enrich.

It’s ironic that NFTs were originally conceived of as an ethical correction to an art market that often failed to reward artists for their effort.

One of the first NFTs was created in response to the rampant copying and sharing of digital artworks on the internet, often without attribution or compensation offered to the original artists.

The idea was to create a special kind of digital token that represented ownership of a particular artwork, similar to a digital receipt or the deed to a block of land. Artists could sell the tokens associated with their work in order to derive an income. It would also track who owned a particular artwork at any point in time, showing provenance all the way back to the original artist.

It was hoped NFTs would give artists more control over their work and create a thriving and lucrative market for them to make an income.

The blockchain seemed to be the ideal technology for creating just such a token, with it being a long ledger of transactions that is maintained by a decentralised network of computers. The most popular tokens on blockchains are cryptocurrencies, like Bitcoin or Ether, but other kinds of tokens exist as well.

The big difference between a cryptocurrency token and an NFT is that the former are fungible, in the sense that any individual Bitcoin is functionally identical and worth the same amount as any other Bitcoin. In contrast, NFTs are non-fungible, so every one is unique and they might be worth very different amounts. Some NFTs also embed code that enable the artist to take a cut of all subsequent sales of that token, which could be a lucrative form of revenue if their art appreciates in value over time and is sold to new buyers.

What have I bought?

Since 2014, NFTs have evolved and become more sophisticated, many moving to the Ethereum blockchain. Most NFTs are essentially a record of ownership of a particular digital asset, like an image or video. It is important to note that the asset itself is not stored on the blockchain – it might be stored on one or more servers somewhere on the internet or offline – the NFT only contains a link or pointer to where the asset is stored.

In terms of moral rights, NFTs don’t give the owner control of the intellectual property, such as copyright, which usually remains with the artist. Owning one also doesn’t prevent the asset from being viewed, copied or downloaded by others; someone might have paid US$23.7 million for that digital punk but you can copy it to your heart’s content. Unlike traditional property, an NFT doesn’t give the owner a right to exclude others from using or benefiting from what they own.

All an NFT allows the owner to do is sell that NFT to someone else. It’s like buying the deed to a plot of land, except you’re not able to fence it off, and you can’t even prevent others from creating a second (or third, or fourth…) deed for the same plot of land.

So what does an NFT owner really own? It’s not the artwork, nor is it the right to prevent others from accessing it. What they own is the NFT. This has led some people to suggest that buying an NFT only offers “bragging rights” over a particular piece of art.

Even so, some clearly see value in that right to brag – sometimes to the tune of millions of dollars – but those bragging rights can come at a cost to many of the artists that NFTs were supposed to benefit.

Crypto patrons

One of the main selling points of NFTs is that they are a way to support artists. And there’s no doubt that some artists have done extremely well by selling NFTs. However, the promise of opening up new markets and new buyers to smaller and emerging artists has, so far, failed to materialise.

Like with conventional art, a majority of the revenue from NFT sales has flowed to a small minority of popular artists, with a tiny proportion of NFTs and buyers accounting for a vast majority of purchases and sales.

Thus, to date, NFTs have served to concentrate wealth among a few artists and investors rather than spread it around. And as new artists have entered the NFT sphere, it has only further crowded the space, lending greater advantage to those with the name recognition or resources to advertise their work.

There have been initiatives to encourage artists to create NFTs of their work in an attempt to tap into what appears to be a lucrative market, such as venture capitalist Mark Carnegie working with artists from the Buku-Larrnggay Mulka Centre in Yirrkala in the Northern Territory. However, in order to create an NFT on the Ethereum network, the artist must pay blockchain processing fees, which could cost hundreds of dollars per transaction. If the artwork doesn’t sell and they don’t have financial backing, they might end up out of pocket.

Shark infested

NFTs have also stung many artists in other ways, particularly through plagiarisation, where someone else creates an NFT of their artwork and sells it without their knowing about it or receiving any revenue from it. This has forced some artists, like DC Comics artist Liam Sharp, off platforms like DeviantArt, where they previously displayed their work. The problem got so bad that in January 2022 one of the main platforms for trading in NFTs announced that over 80% of the NFTs created for free on its platform were “plagiarized works, fake collections, and spam.”

NFTs are also vulnerable to fraud. One popular scam is called wash trading, where one or more traders buy and sell NFTs amongst themselves, thereby inflating the price before selling them on to some unsuspecting buyer.

Another common scam is a rug pull. This is where someone generates buzz by announcing a new and exciting NFT project with big promises of future features. But after the creators sell the first tranche of NFTs, they close the project, take the money and run. Sometimes they have even locked the NFTs from being traded, preventing buyers from recouping any of their money by selling the NFTs on the open market.

Another example of NFT fraud includes classic social engineering, where scammers pretend to be official representatives of NFT marketplaces, thus gaining access to victims’ crypto wallets, enabling them to transfer cryptocurrency or NFTs into their own wallets.

All of these scams represent a deeper ethical problem than just a few miscreant operators exploiting rare loopholes. They’re due to fundamental problems with the NFT system itself because it contains few protections against these kinds of exploits.

If a commercial business opened an auction house that had no protections against people selling things they didn’t own, or failed to follow through on delivering promised goods, or that didn’t have robust policies to protect against social engineering scams, it would likely be closed down by regulators.

Decentralised means unregulated

One of the claimed merits of the blockchain is its unregulated nature. The network of technologies, financial tools, cryptocurrencies and NFTs is sometimes proudly referred to as decentralised finance (DeFi) by enthusiasts.

The deregulated nature of DeFi also means that users are not reliant on banks or other conventional institutions to handle transactions, so they are also not covered by the same regulations and protections that people enjoy when using a bank.

This has led some commentators, including prominent technology journalist Cory Doctorow, to refer to DeFi as “shadow banking 2.0”. This is a reference to the first generation of “shadow banking,” which included all the highly obscure and largely unregulated financial instruments that contributed to the global financial crisis in 2008.

Compounding the problem is the inclusion of “smart contracts” in many NFTs. These are small bits of code that trigger under particular circumstances, like allowing an artist to receive a future cut of sales. But smart contracts have also been used for nefarious purposes, such as directly stealing money from people who own NFTs.

Hot air

Every time you make a transaction on the Ethereum network, such as buying or selling an NFT, you burn through roughly 229 kilowatt hours (kWh) of power, generating 128 kilograms of carbon dioxide equivalent (CO2e). That’s about the same amount of energy consumed by a typical NSW home over two whole weeks. Ethereum, the most popular platform for NFTs, burns nearly 100 terawatt hours each year, which is comparable to the energy consumption of Ghana, emitting over 54 million tonnes of CO2e.

This is because blockchains like Bitcoin and Ethereum use vast amounts of computing power, distributed over countless individual computers around the world, in order to continually validate and cross-validate each new transaction. The cost is not only in terms of energy prices but also their impact on the planet.

While many other products label their carbon emissions, and many offer consumers low carbon options or carbon offsets, no such options are available for NFTs. In fact, if you were to offset the emissions of a single transaction at current Australian carbon credit prices of around $30 per tonne of CO2e, it would cost you about $4. And if you tried to offset the total emissions of the entire Ethereum network, it would cost $1.6 billion dollars – not that there’d likely be enough offsets to cover that carbon debt.

Is it ethical to buy NFTs?

Even if you care about artists deriving an income from their work and you want to open up new markets to smaller and emerging artists, then it’s difficult to justify NFTs on these grounds alone.

If you believe that an ethical marketplace ought to have basic consumer protections to prevent scams and fraud, then it’s difficult to endorse NFTs given their deregulated nature, complexity and the many loopholes that are vulnerable to abuse.

And if you consider yourself ethically responsible for the emissions that you produce, particularly those related to discretionary expenses, then it is difficult to justify the emissions required to make even a single NFT transaction.

All of this is entirely separate to considerations of whether NFTs are a good financial investment, whether they’re a virtual asset bubble, or even if NFTs represent something that carries meaningful property rights.

If you want to support artists, buy their art. Thankfully, there are many ways of doing so that don’t involve the blockchain, cryptocurrencies, DeFi or NFTs.

Artwork by Yuga Labs, Bored Ape Yacht Club, 2021

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.