The truth isn't in the numbers

The truth isn’t in the numbers

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + Leadership

BY Fiona Smith Cris 27 AUG 2019

If you want to work out what the people are thinking, one thing is for sure, you can’t just go out and ask them.

The failures of political polling over recent elections have taught us that opinion surveys can no longer be trusted. If you were betting on the winner, you would have been better off putting your money on the predicted losers.

This was a $5.2 million lesson for betting company Sportsbet when it pre-emptively paid out Bill Shorten backers – two days early – based on the fact that seven out of every ten wagers supported a Labor win in May. Labor lost, the gamblers got it wrong.

And it is not just the polling and betting companies that have lost credibility as truth-telling tools. Science is having its own crisis over the quality of peer-reviewed research.

Just one sleuth, John Carlisle (an anaesthetist in the UK with time on his hands) has discovered problems in clinical research, leading to the retraction and correction of hundreds of papers because of misconduct and mistakes.

The world of commerce is no better at ensuring that decisions are backed by valid, scientific research. Too often, companies employ consultants who design feedback surveys to tell clients what they want to hear, or employers hire people based on personality questionnaires of dubious provenance.

Things are further complicated by poor survey questions, untruthful answers, failures of memory and survey fatigue (36 per cent of employees report receiving surveys regularly, three or more times per year).

Why bother?

All of this may give rise to the notion that asking people for their opinion is an utter waste of time. However, that is not the conclusion drawn by Adrian Barnett, president of the Statistical Society of Australia and professor at the Queensland University of Technology.

Barnett, who studies the value of health and medical research, says people should view all surveys with a healthy skepticism, but there is no substitute for a survey with a good representative sample.

“I do think there is a problem, yes, but it is potentially overblown, or overstated” he says.

“We know that, in theory, we can find out what the whole population is feeling by taking just a small sample and extrapolating up. We know it works and it’s a brilliant, cheap way of finding out all sorts of things about the country and about your customers,” he says.

However, it is getting harder to get that representative sample. As people have replaced their landlines with mobile phones, researchers can no longer rely on the telephone book to source an adequate spread of interviewees. And, even if they make contact via a mobile phone, people are now reluctant to answer calls from unknown numbers in case they are scammers, charities … or market researchers.

“(Also) on controversial topics, it can be extremely challenging to get people to talk to you,” Barnett says.

You need the right people

Reluctance to participate is one of the problems identified in political polling. In a post-election blog, private pollster Raphaella Crosby described the issue: “You can have a great, balanced, geographically distributed panel such as ours or YouGov’s – but it was very difficult to get conservatives to respond in the last three weeks.

“I presume phone pollsters had the same issue – the Coalition voters just hang up the phone, in the same way they ignored our emails. All surveys and polls are opt-in; you simply can’t make people who think their party is going to lose do a survey to say they’re voting for a loser.”

The Pew Research Centre reports that response rates to telephone surveys in the US are down to 6 per cent.

The polling industry is conducting an inquiry into election polling methods, which include a combination of calling landlines, mobile phones, robo-dialling and internet surveys. Each of these channels can introduce biases and, then, there can be errors of analysis and a tendency to “groupthink”.

However, Barnett says the same problems do not necessarily hamper market research.

Market research does not usually require the large pool of participants (up to 1,600 is common in pre-election polls) which are needed to narrow the margin of error. Business can question a small number of customers and get a clear indication of preferences, he says.

Identifying a representative sample of customers is also much easier than a random selection of voters who must represent an entire population.

Putting employees to the test

When it comes to business, the use of engagement surveys presents an interesting case. Billions of dollars are spent by business every year to try to increase employee engagement – yet little benefit can be seen in the engagement survey statistics.

According to polling company Gallup, a mere 14 per cent of Australians are engaged in their work, “showing up every day with enthusiasm and the motivation to be highly productive”. This is down from 24 per cent, six years earlier.

Jon Williams has 30 years of experience to back up a jaundiced view of the way employee surveys are used. Co-founder of management consultancy Fifth Frame, Williams was previously PWC’s global leader of its people and organisation practice, managing principal at Gallup in Australia, and managing director of Hewett Associates (Aon Hewett).

“Clearly, engaged places are better places to be and, if we are going to work on that stuff, we are going to create better workplaces. But can it actually be linked to success? Does it really drive more successful companies? I think you would struggle to really prove that.”

Williams says people fail to understand that correlation is not causation. A company may put a lot of effort into its high engagement and also be very successful, but that success may, in fact, stem from other factors such as its place in the market, timing, dynamic leadership or the economy.

“It is a false attribution because we love the idea of certainty and predictability,” he says.

This same desire to codify success also drives the use of personality testing in recruitment – which appears to have done little to rid the workplaces of bullies, psychopaths and frauds.

“Business just wants something that looks like a shiny tool with a brand name on it that they can assume, or pretend, is efficient,” he says.

“People like [the tests] because they give the appearance of rigour. Very few of those tools have any predictive reliability at all.”

Williams says the only two personality measures that have any correlation with job success are intelligence and conscientiousness.

Meanwhile, many organisations still ask their employees to undertake an assessment with Myers-Briggs Type Indicator – a personality test that divides people into 16 different personality types and based on the work of a mother-daughter team, who had no training in psychology or testing, but a devotion to the theories of Swiss psychiatrist Carl Jung.

“Myers Briggs has the same predictive validity as horoscopes. Horoscopes are great for starting a conversation about who you are as a person. Pretending it is scientific, or noble, is obviously stupid,” says Williams.

What can we do better?

Williams is not advocating that organisations stop asking employees what they think. He says, instead, that they should reassess how they regard that information.

“Don’t religiously follow one tool and think that is the source of all knowledge. Use different tools at different times. Then, don’t keep measuring the same thing for the next five years, because you’ve done it [already]. Go to a different tool, use multiple inputs. Just use all of them intelligently as interesting pieces of data.”

Barnett has his own suggestions to increase the reliability of surveys. Postal surveys may seem rather “old school” these days, but can allow researchers to engage a bit more, allowing them to establish their bona fides with people who are (justifiably) suspicious of attempts to “pick their brains”.

Acknowledging that the interviewees’ time is valuable can help elicit honest, thoughtful responses. Something as simple as including a voucher for free coffee or a chocolate can show value.

Adding a personal touch, using a real stamp on the return envelope, will also encourage participation. ‘”It shows you spent time reaching out to them,’” Barnett says.

Citizens’ juries can also help make big decisions, using a panel of people to represent customers or a population.

Infrastructure Victoria used this technique in February when it set up a 38-member community panel to consider changing the way Victorians pay for the transport network.

“We know there are problems with [citizens’ juries], but the reason we have them is that you are being judged by your peers. If you can get a representative bunch of your customers, then I think that is an interesting idea,” he says.

“You really might not like what they say, or you may be surprised by what they say – but those surprising results can sometimes be the best in a way, because it may be something you have been missing for a long time.”

Questions you should ask

The American writer Mark Twain was well aware that numbers can be contrived to back any argument.

“Figures often beguile me, particularly when I have the arranging of them myself; in which case the remark attributed to Disraeli would often apply with justice and force: ‘There are three kinds of lies: lies, damned lies, and statistics’,” he wrote.

The observation could be made of many of the survey results found online. Many have been produced as a marketing exercise by companies and reproduced by others who want numbers to add some weight to their arguments.

However, rather than accepting, on face value, survey claims that 30 per cent of the population thinks this or that, some basic checks can help determine whether the research is valid.

A good place to start is the Australian Press Council’s guide for editors, dealing with previously unpublished opinion poll results:

- The name of the organisation that carried out the poll

- The identity of any sponsor or funder

- The exact wording of the questions asked

- A definition of the population from which the sample was drawn

- The sample size and method of sampling

- The dates when the interviews were carried out

- How the interviews were carried out (in person, by telephone, by mail, online, or robocall)

- The margin of error

Other questions may be to ask where the participants were found and are they typical of the whole population of interest?

If only a small proportion of people responded, then you may deduce that the survey is biased towards the people who have strong feelings about the subject.

If the subjects were paid, this might affect their answers.

In the UK, there is a public information campaign Ask For Evidence, to encourage people to request for themselves the evidence behind news stories, marketing claims and policies.

This article was originally written for The Ethics Alliance. Find out more about this corporate membership program. Already a member? Log in to the membership portal for more content and tools here.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Ready or not – the future is coming

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Why trust-building strategies should get the benefit of the doubt

Opinion + Analysis

Science + Technology, Business + Leadership

3 things we learnt from The Ethics of AI

Reports

Business + Leadership

Managing Culture: A Good Practice Guide

Join our newsletter

BY Fiona Smith

Fiona Smith is a freelance journalist who writes about people, workplaces and social equity. Follow her on Twitter @fionaatwork

BY Cris

Courage isn’t about facing our fears, it’s about facing ourselves

Courage isn’t about facing our fears, it’s about facing ourselves

Opinion + AnalysisRelationships

BY Matthew Beard 22 AUG 2019

What was your first lesson in courage? The first time someone told you to be brave – or explained to you that fear was something to be overcome, not something that should control you?

I can’t remember the very first moment I encountered the idea of courage, but the first I can remember – and the one that has stayed with me the longest – is this: “being brave doesn’t mean we looking for trouble.”

It is, of course, from Disney’s The Lion King. Mufasa, moments after saving his son, Simba, from ravenous hyenas, chastises his boy for putting himself and his friend in danger.

Simba’s journey in The Lion King is really a treatise on courage. From a reckless, thrill-seeking child, Simba loses his father and, believing himself responsible, flees from the social judgement that might bring.

Simba takes his father’s lesson too far: he doesn’t look for trouble, but when it finds him, he runs from it. He lives as an exile in a hedonistic paradise. Comfortable, apathetic, safe. For all his physical prowess, Simba is a coward.

Of course, by the end of the film Simba has found courage. He accepts his identity as the true king, admits his shame publicly, defeats Scar (his true enemy) and takes his place in the circle of life, complete with staggering musical accompaniment.

As well as having a soundtrack that’s jam-packed with bangers, it turns out the Lion King has a strong philosophical pedigree.

Courage as a virtue

The Greek philosopher Aristotle believed that courage was as virtue – a marker of moral excellence. More specifically, it was the virtue that moderated our instincts toward recklessness on one hand and cowardice on the other.

He believed the courageous person feared only things that are worthy of fear. Courage means knowing what to fear and responding appropriately to that fear.

For Aristotle, what mattered isn’t just whether you face your fears, but why you face them and what it is that you fear.

There is something important here. Your reasons for overcoming fear matter. They can be the difference between courage, cowardice and recklessness.

For instance, in Homer’s Iliad, the Trojan prince Hector threatens to punish any soldier he sees fleeing from the fight. In World War I, soldiers who deserted were executed.

Were these soldiers courageous? The only reason they risk death from the enemy is because they’re guaranteed to be killed if they don’t. The fear of death is still what drives them.

More courageous, says Aristotle, is the soldier who freely chooses to fight despite having no personal reason to do so besides honour and nobility. In fact, for Aristotle, this is the highest form of courage – it faces the greatest fear (death) for the most selfless reason (the nation).

Of course, Aristotle was an Ancient Greek bloke, so we should take his prioritising of military virtue with a grain of salt. Is death at war really to be so highly prized?

For one thing, in a culture like Ancient Greece or Troy, the failure to be an excellent warrior would be met with enormous dishonour. How many soldiers went to war for fear of dishonour? Is dishonour something to be rightly feared? And if so, whose dishonour should we fear?

Surely not that of a society whose moral compass prioritises victory over justice – risking your life to support a cause like that is reckless.

If courage means fearing dishonour from those who are morally corrupt, then a courageous enemy is worse than a cowardly one. Courage becomes like a superpower – making some people into heroes and others villains.

But there’s a deeper reason to doubt Aristotle’s idea of the highest courage. Whilst most of us do fear death, it’s not clear that it’s the thing we fear most. Even if we do fear death, we have a range of different reasons for doing so.

Our deepest fears

Perhaps my most visceral fear is of drowning. The thought of it is enough to make me feel short of breath. Perhaps that’s because of an experience when I was younger – when I was overseas I learned that my Dad nearly drowned. It was perhaps the first time I really had to come to grips with the fact he was mortal – and so was I – and all that I loved.

Today, I fear death because it would mean never seeing my children grow up. Never holding them one last time. Seeing my son’s first days at school. Hearing my daughter’s first words.

Worse, I wouldn’t be sure that they were safe and flourishing. If someone could guarantee that, perhaps I’d be less fearful of death. It’s not the death I fear; it’s what it represents: an incomplete life, failed commitments, unending love brought to a close.

Aristotle didn’t consider courage in the face of existential anxieties like these. What does it mean to live courageously in a world where all our loves, passions and projects expose us to pain and loss? To live is to have a nerve constantly exposed to the world – always vulnerable to suffering.

The French psychoanalyst and philosopher Anne Dufourmantelle argues that risk is an inherent part of living fully in the world. Risk-free living, she argues, is not living at all. Courage is as much about living despite knowing the exposed nerve of love and passion could trigger chest-tightening pain at any moment.

Yet so often we close ourselves from the world to keep ourselves safe. We self-censor not because we think we might be wrong, but because we fear upsetting the wrong person. We withdraw from relationships because we don’t want to be the one to take the leap. We tell ourselves stories in the shower of all the things we could do – could be – if only the world let us.

Existentialist philosophers have a name for this kind of self-deception: bad faith – a kind of failure to engage with the world as it really is and accepting ourselves as we are and as we could be.

Too often we think of courage purely as facing up to our fears. What that misses is how deeply connected our fears are with deeper beliefs about who we are, who we want to be, who we love and what we wish the world was.

A courageous truth

Maybe the truth of courage is that it’s all about truth. It’s about looking reality in the face and having the force of will not to turn away, despite the pain, the unpleasantness and the risk.

Maybe it’s about looking for long enough to see the joy in the pain; the beauty in the ugliness and the comfort that lies in the little risks we take every day.

Perhaps it’s only then we can know what’s worth dying for – and what’s worth living for. Certainly, Dufourmantelle gives us some hope of this. In 2017, she died in rough seas off the coast of France, having swum out to rescue two children caught in the surf.

The children survived, but how many of us would have dived in? How many would have hoped for a lifeguard? A stronger swimmer? For the children to rescue themselves?

I want to encourage you to think: are there rough waters you’re not jumping into for fear of the waves? Do you tend to dive in without counting the costs?

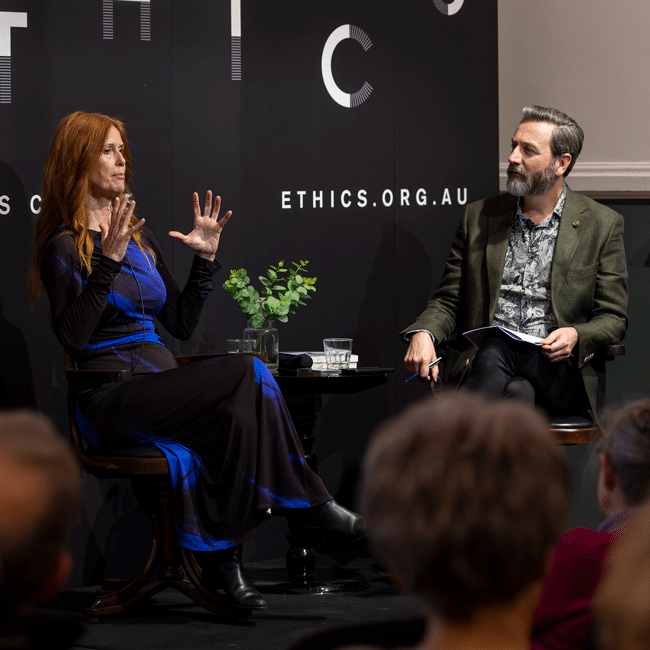

Dr Matt Beard was the host of The Ethics of Courage, alongside Saxon Mullins and Benjamin Law at The Ethics Centre on 21 August. This is a transcript of his opening address.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Should you celebrate Christmas if you’re not religious?

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Eight questions to consider about schooling and COVID-19

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Our desire for reality: What OnlyFans says about sexual fantasy

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

“I’m sorry *if* I offended you”: How to apologise better in an emotionally avoidant world

Join our newsletter

BY Matthew Beard

Matt is a moral philosopher with a background in applied and military ethics. In 2016, Matt won the Australasian Association of Philosophy prize for media engagement. Formerly a fellow at The Ethics Centre, Matt is currently host on ABC’s Short & Curly podcast and the Vincent Fairfax Fellowship Program Director.

Look at this: the power of women taking nude selfies

Look at this: the power of women taking nude selfies

Opinion + AnalysisHealth + WellbeingRelationshipsSociety + Culture

BY Amy Gray 22 AUG 2019

The continuing moral panic over women’s naked selfies is fundamentally misframed. By emphasising the potential for women to be made victims, we ignore the ways a woman’s body can be an expression of power.

According to the prevailing moral panic of the day, young women take naked selfies in order to please others and not themselves. This, we’re told, leaves them vulnerable to exploitation because women must always be vulnerable.

It’s as though the only mystery afforded to women is not their thoughts or talents but what lies underneath their clothes. Go no deeper than the skin. Deny any complexity that might present her as a human with needs separate from what men may want.

This seems to be a narrative we teach teenagers. My daughter was taught that not only was there no legal recourse for photos shared without consent (untrue) but that the effects on women were so catastrophic that they should never send a naked photo (also, untrue). This happened on International Women’s Day, as if to remind us of our to-do list.

Inevitably, they learn what we teach. When I worked with teens on a short film, they told me how boys pestered every girl in their class for naked selfies. The girls didn’t even think it was sexual; more of a competitive collection like Pokemon Go but for undeveloped breasts. The requests were thought of as frustrating but normal, because “that’s just how they are”. Yet despite the mundanity of such a frequent request, the same teens sincerely believed leaked selfies would hound a woman to her grave.

Naked selfies carry many gendered clashes. I’ve always gasped at the difference between gendered aesthetics: I’ll rush to clean my room, groom and put on makeup before getting into an appropriate outfit of sorts before painstakingly composing shots; men just send a close-up photo of their cock jutting from a thicket of pubes.

It’s an effective example of the differences between the male and female gaze. A woman prepares because she is conditioned to know what men find attractive and that she is expected to deliver that. Men, conditioned to expect immediate access regardless of merit, put almost zero thought into their selfies. In the rare case they do, they project an image of themselves they want to see, rather than women who mirror what men want to see.

This positioning reinforces the power dynamic in heterosexual sexting. Men expect entertainment and women entertain at threat of exposure (also expected).

But why does the power lie with men?

On image sharing site Imgur, men enthusiastically share photos of naked women, even creating themed days for certain ‘types’ of women. But the images presented reflect the male gaze – photos taken of women, not by women.

Generally, whenever women posted selfies on Imgur, sexualised or not, she was immediately inundated with caustic remarks to stop being an exhibitionist (a polite euphemism for attention whore). That these are the same men who think nothing of going into a woman’s DMs to ask for naked photos is just another layer to it all. There is a clear mode of production, where women are the object and men remain in control of when and how they are seen. This is where the phrase “tits or get the fuck out” shows its intent: give us the body parts, not the entire body.

Perhaps this is because it is easier to sexually appreciate an object that has not been humanised or seen as an individual. When things are anonymised or presented in such a volume that they lose all semblance of individuality, they become an object that can be appreciated or abused without shame.

The power balance still rests with men – naked women are objects men readily expect, and demand to be presented in anticipated service of them. In this position of power, men expect women to arouse them, yet rarely consider whether women are aroused. Amazingly, we rarely discuss whether women find joy or pleasure in taking naked selfies, whether for themselves or others because we can’t move past women’s seemingly inevitable victimhood.

I’ve taken naked selfies for well over a decade. I first worried if photos might leak but, somewhat ironically, this concern has disappeared as I do more work in public. In Doing It: Women Tell the Truth About Great Sex, an anthology about sex, I wrote of how selfies can become graphic storytelling that not only builds intimacy but also an understanding of my sexuality and my sexual aesthetic pleasure. It is a power I never want to give up, so the book also contains a naked photo of me I had taken for a lover. It is a deliberate attempt to interrupt the means of production and also claim space within my sexuality, one that is defined by myself, not others.

When the photo was republished (with consent) by SBS, I wrote that “this is not some wishy-washy Stockholm syndrome masquerading as empowerment – there is ferocity in my choice”. It remains true today. By claiming my agency as an individual who feels pleasure and expression, I realise that confidence is not only crucial for my personal survival under patriarchy framed solely for men, but it is also a political act I can define as I choose. It makes me aware that my body, choices and actions are decided by me without reference to others’ expectations and that I contain greater complexity the roles of servant or victim that society allows.

Around this time, Mia Freedman wrote an article entitled ‘The conversation we have to have: Stop taking nude selfies’. Promoting the article on Twitter, Freedman wrote “taking nude selfies is your absolute right. So is smoking. Both come with massive risks.” In response, I took another naked selfie, but this time with a cigarette draped from my mouth and ‘fuck off’ written on my chest in black lipstick. I posted it everywhere without care because – again – my body, choices and actions are decided by me. I made the choice that and every day is that I will not have victims presented as complicit in their abuse. Because the fault will always be with the abuser, not the abused.

An act of power

Despite their conflicting emotions, publishing naked selfies taken in either arousal or anger are fearsome in their power. They are as much a rejection of victimhood as they are an opportunity for retribution. People can try to weaponise my body against me, but I will do it first and use it against them because I know its power.

This is why patriarchal structures and men condition women into submissive disempowerment. Women’s bodies are defined narrowly as vessels for pleasures and service for others, not ourselves. Such narrow and compliant definitions intentionally belie the power and complexity we contain.

Stories abound throughout history of the malevolent power of women’s bodies, so profound was male unease surrounding bloods and births. Women were told their vaginas ruined ship rope or their menstruation damned success. This was an admission women’s bodies were terrifying in their otherness but was also an excuse to contain them to the home rather than out in the community where they might gain power or control.

But history tells us many women believed in the power of their bodies. Balkan women would stand out in the fields, flashing their vaginas to the sky to quell thunderstorms. The Finnish believed in the magic of harakointi, using their exposed bodies to bless or curse on whim. Sheela-na-gigs (carvings of women often found in European architecture) embraced their power by spreading their labia, not to please or welcome men, but scare off evil. Women would lift their skirts to make others laugh in feasts for Roman gods and goddesses or lure lovers. More recently, women have exposed their bodies to protest petroleum in Nigeria or civil war in Liberia in acts of political, angry anasyrma.

Reframing the dialogue

The continuing moral panic over women’s naked selfies is fundamentally misframed. Women are presented as passively-defensive vessels in a state of perpetual victimhood. We are tasked with hiding our shameful-yet-coveted nakedness from people who expect to see us but only under their strict conditions.

A truer representation is that power exerts in all manners of life, including how we sexually communicate as equal, consenting partners. The moral panic should focus on when power corrupts that balance and how to correct it, not how to maintain the same corruption.

Join us as on 18 September for an an intimate conversation with Sexologist, Nikki Goldstein and art curator Jackie Dunn to unwrap the ethical dimensions of being nude. Get your ticket to The Ethics of Nudity here.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Who are you? Why identity matters to ethics

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture

Who’s afraid of the Big Bad Wolf? The story of moral panic and how it spreads

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Ethics in a time of coronavirus

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Plato’s Cave

Join our newsletter

BY Amy Gray

Amy Gray is a Melbourne-based writer interested in feminism, popular and digital culture and parenting. follow her on twitter @_AmyGray_

Time for Morrison’s ‘quiet Australians’ to roar

Time for Morrison’s ‘quiet Australians’ to roar

Opinion + AnalysisPolitics + Human Rights

BY Simon Longstaff 21 AUG 2019

The Prime Minister, Scott Morrison, has attributed his electoral success to the influence of ‘Quiet Australians’.

It is an evocative term that pitches somewhere between that of the ‘silent majority’ and Sir Robert Menzies’ concept of the ‘Forgotten People’. Unfortunately, I think that the phrase will have a limited shelf-life because increasing numbers of Australians are sick of being quiet and unobserved.

In the course of the last federal election, I listened to three mayors being interviewed about the political mood of their rural and regional electorates. They said people would vote to ensure that their electorates became ‘marginal’. Despite their political differences, they were unanimous in their belief that this was the only way to be noticed. They are the cool tip of a volcano of discontent.

Quiet or invisible?

Put simply, I think that most Australians are not so much ‘quiet’, as ‘invisible’ – unseen by a political class that only notices those who confer electoral advantage. Thus, the attention given to the marginal seat or the big donor or the person who can guarantee a favourable headline and so on…

The ‘invisible people’ are fearful and angry.

They fear that their jobs will be lost to expert systems and robots. They fear that, without a job, they will be unable to look after their families. They fear that the country is unprepared to meet and manage the profound challenges that they know to be coming – and that few in government are willing to name.

They are angry that they are held accountable to a higher standard than government ministers or those running large corporations. They are angry that they will be discarded as the ‘collateral damage’ of progress.

And in many ways, they are right.

Is democracy failing us?

After all, where is the evidence to show that our democracy is consciously crafting a just and orderly transition to a world in which climate change, technological innovation and new geopolitical realities are reshaping our society? Will democracy hold in such a world?

By definition, democracy accords a dignity to every citizen – not because they are a ‘customer’ of government, but – because citizens are the ultimate source of authority. The citizen is supposed to be at the centre of the democratic state. Their interests should be paramount.

Yet this fundamental ‘promise’ seems to have been broken. The tragedy in all of this is that most politicians are well-intentioned. They really do want to make a positive contribution to their society. Yet, somehow the democratic project is at risk of losing its legitimacy – after which it will almost certainly fail.

In the end, while it’s comforting to whinge about politicians, the media, and so on, the quality of democracy lies in the hands of the people. We cannot escape our responsibility. Nor can we afford to remain ‘quiet’. Instead, wherever and whoever we may be, let’s roar: We are citizens. We demand to be seen. We will be heard.

The Ethics Centre’s next IQ2 debate – Democracy is Failing the People – is on Tuesday 27 August at Sydney Town Hall. Presenter and comedian Craig Reucassel will join political veteran Amanda Vanstone to go up against youth activist Daisy Jeffrey and economist Dr Andrew Charlton to answer if democracy is serving us, or failing us.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

McKenzie… a fractured cog in a broken wheel

Explainer

Politics + Human Rights

Thought Experiment: The famous violinist

Big thinker

Health + Wellbeing, Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Big Thinker: Judith Butler

Explainer

Society + Culture, Politics + Human Rights

Ethics Explainer: Just Punishment

Join our newsletter

BY Simon Longstaff

Simon Longstaff began his working life on Groote Eylandt in the Northern Territory of Australia. He is proud of his kinship ties to the Anindilyakwa people. After a period studying law in Sydney and teaching in Tasmania, he pursued postgraduate studies as a Member of Magdalene College, Cambridge. In 1991, Simon commenced his work as the first Executive Director of The Ethics Centre. In 2013, he was made an officer of the Order of Australia (AO) for “distinguished service to the community through the promotion of ethical standards in governance and business, to improving corporate responsibility, and to philosophy.” Simon is an Adjunct Professor of the Australian Graduate School of Management at UNSW, a Fellow of CPA Australia, the Royal Society of NSW and the Australian Risk Policy Institute.

Big Thinker: John Locke

English Philosopher John Locke (1632—1704) is behind many of the ideas we now take for granted in a liberal democracy. Amongst them, his defence of life and liberty as natural and fundamental human rights.

He was especially known for his liberal, anti-authoritarian theory of the state, his empirical theory of knowledge and his advocacy of religious toleration. Much of Locke’s work is characterised by an opposition to authoritarianism, both at the level of the individual and within institutions such as the government and church.

Born in 1632, in his time he gained fame arguing that the divine right of kings is not supported by scripture. Instead, he defended a limited government whose duty is to protect the rights and liberty of its citizens. This idea is familiar to us now, yet at the time it was revolutionary, arguing against the monarchy as the source of society’s governance. A familiar idea in modern day, at the time it was revolutionary – an argument to depart from the monarchy as the source of society’s governance.

In defending his stance, Locke appealed to the notion of natural rights. He invited us to imagine an initial ‘state of nature’ with no government, police or private property. Locke argued that humans could discover, through careful reasoning, that there are natural laws which suggest that we have natural rights to our own persons and to our own labour.

Eventually we could reason that we should create a social contract with others. Out of this contract would emerge our political obligations and the institution of private property. In Locke’s version of the social contract, a human “divests himself of his natural liberty, and puts on the bonds of civil society…agreeing with other men to join and unite into a community” and by submitting to majority rule form a government designed to protect their rights.

The limits of power

Locke’s argument also places limits on the proper use of power by government authorities. While civil society, as viewed through Locke’s liberalism, sees that the individual must sacrifice – or at least compromise – his/her freedom in the name of the public good, the public good ought not to interfere with the individual’s freedom.

Due to this emphasis on liberty, Locke defended a distinction between a public and a private realm. The public realm is that of politics and the individual’s role in the community as a part of the state, which may include, for example, voting or fighting for one’s country. The private realm is that of domesticity where power is parental (traditionally, ‘paternal’).

For Locke, government should not interfere in the private realm. He held the argument that citizens were entitled to protest or revolt or disband a government when it failed to protect their collective interests. On this view it is crucial we distinguish the legitimate from the illegitimate functions of institutions.

Locke asked us to use reason in order to seek the truth, rather than simply accept the opinion of those in positions of power or be swayed by superstition. In this way, we see Locke as an Enlightenment thinker –our natural reason a light that shines, guiding our understanding in order to reveal knowledge.

Knowledge and personal identity

As an empiricist, Locke believed we gain our knowledge through experiences in the world. In contrast to the views of his rationalist predecessor Descartes, Locke argued that we are born as a blank slate or a tabula rasa. This means that at birth our mind has no innate ideas – it is blank. As our mind develops, sensations give rise to simple ideas, from which we form those more complex.

This theory of learning gives rise to another radical idea for his time. Locke asserted that in order to help children avoid developing bad thinking habits, they should be trained to base their beliefs on sound evidence. The strength of our belief should correlate to how strong or weak the evidence for it happens to be.

Furthermore, for Locke, our consciousness is what makes us ‘us’, constituting our personal identity.

Locke’s legacy

We see Locke’s legacy in the 1776 US Declaration of Independence, which was founded on his natural rights theory of government and proclaimed ‘we hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness’.

Following on from his theory of human rights, we also see Locke’s legacy in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, which was adopted by the United Nations General Assembly on 10 December 1948. Philosophers debate as to whether such rights are indeed ‘natural’, or whether they have been ‘constructed’ and agreed upon by society as useful rules to adopt and enforce.

Locke’s lasting legacy is the argument that society ought to be ruled democratically in such a way as to protect the liberty and rights of its citizens. And that the government should never over-step its boundaries and must always remember it is a glorified secretary of the people.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Who’s your daddy?

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Society + Culture

There’s more to conspiracy theories than meets the eye

Opinion + Analysis

Climate + Environment, Politics + Human Rights

Are we idolising youth? Recommended reads

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Politics + Human Rights

Feminist porn stars debunked

Join our newsletter

BY Dr Laura D’Olimpio

Dr Laura D’Olimpio is senior lecturer in philosophy of education at the University of Birmingham, UK, and co-edits the Journal of Philosophy in Schools.

Why purpose, values, principles matter

Why purpose, values, principles matter

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + Leadership

BY The Ethics Centre 13 AUG 2019

In advising organisations about ethics and culture, our Ethics Centre consultants often start by asking a simple question: “Do you have an ethical framework?” What we’re trying to understand is whether the company has a well-defined purpose, supported by values and principles. It’s the bedrock upon which every successful and well-run company is built.

Over the last twenty years we have witnessed a veritable roll call of organisations who have faced an ethics crisis. And for some, this crisis has threatened their very existence. And while the individual factors will vary, there is often one underlying root cause of this failing – a drift from the organisation’s ethics framework.

An ethics framework is a critical foundation for any organisation. It expresses their purpose, values and principles – quite literally, what they believe in and what standards they’ll uphold. In making these visible, as well as living across everything they do, it allows the organisation to be the best possible version of itself, now and into the future.

If an ethics framework is practically useful, it will provide a way to diagnose ethics failure, apportion responsibility and offer a means to provide justice for victims. However, this is merely the minimum standard. It also provides the ideal that should be strived for.

An ethics framework demands something more than mere compliance. It asks employees to exercise judgement and accept personal responsibility for the decisions they make. In order to be effective, it must be consistently embraced by every member of the organisation.

- Values tell us what’s good – they’re the things we strive for, desire and seek to protect.

- Principles tell us what’s right – outlining how we may or may not achieve our values.

- Purpose is our reason for being – it gives life to our values and principles.

The power of a good ethics framework

A strong ethics framework will unite an organisation’s workforce under a common goal, creating a far better workplace culture in the process. It will help leaders make decisions that are consistent with purpose, and improve decision-making capacity across the organisation. It supports a company to be more adaptable to change and clearly demonstrates to clients, customers and other stakeholders what they stand for and where they’re headed.

A company will struggle to develop consistent workplace policies or a corporate strategy without an ethics framework. But the reverse is also true: with an ethics framework all of these processes become far easier to navigate.

Purpose

In designing an ethics framework, much is made of purpose statements – primarily because they tend to be the most visible, public-facing feature of the framework. Creating a great purpose statement is something of an art form, it needs to achieve a great deal in a few words. It should be inspiring, have an aspirational quality, and capture the essence of your company’s ‘why?’.

Ideally, purpose statements should describe how your company is satisfying a need in society or in the market. Examples include Disney’s “To make people happy” or technology powerhouse Atlassian “To unleash the power in every team”. We’re quite proud of The Ethics Centre’s purpose statement which is “To bring ethics to the centre of everyday life.”

Values and principles

Values and principles enable employees to distinguish between what is regarded as important and the means by which they should be pursued. They help to frame business activity to ensure it stays true to its purpose and contract with society. A good framework will be;

- Stable – will not change significantly (in its essence) over the long term

- Understandable – by all of those required to apply it in practice

- Practical – able to be applied in practice and with consistency

- Authentic – it will ‘ring true’.

Good for business

Having an ethics framework isn’t designed to maximise profits – it’s designed to protect and improve the relationship between business and society. But it does often benefit business as a commercial enterprise as well. By motivating employees and demonstrating the value and purpose of the business to them, they serve as ambassadors for the organisation.

Although purpose statements, corporate values and organisational principles aren’t a guarantee of perfect ethical conduct, they are a crucial ingredient in building a culture in which bad behaviour is discouraged and dis-incentivised. They’re also a flag of goodwill to stakeholders that an organisation is looking to serve humanity and not simply turn a quick buck.

Ethics frameworks are not magic bullets to solve an organisation’s problems – they won’t guarantee that all employees will do the right thing every time. But approached with the proper degree of care and sophistication, the very process of developing these codes can have a profoundly positive effect on the culture of an enterprise. In establishing the things you believe in and identifying the behaviours you wish to encourage, you establish a framework for a great corporate culture – one based on respect, trust, collaboration and accountability. And who wouldn’t want that?

Creating an ethics framework

It may surprise you to learn that many companies have no ethics framework at all. And of those that do, many are working with largely meaningless statements that offer little in the way of guidance. Some were written decades ago. Some were cooked up by marketing strategists as part of a corporate branding exercise. Whatever their provenance, there’s a sense that the framework has ceased to have any meaning for the people who work at the company.

Developing an ethics framework is only the starting point. Ensuring the framework is fully embedded and understood throughout an organisation and lived by its people is the harder challenge. Over three decades of consulting work, we’ve helped countless organisations to develop and embed their ethics frameworks. We’ve worked across multiple sectors and with companies of many shapes and sizes.

If you’d like to talk to The Ethics Centre about creating an ethical framework for your organisation, we’d love to hear from you.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Pavan Sukhdev on markets of the future

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships

Workplace romances, dead or just hidden from view?

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Health + Wellbeing

Why ethical leadership needs to be practiced before a crisis

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Dame Julia Cleverdon on social responsibility

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

How to spot an ototoxic leader

How to spot an ototoxic leader

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + Leadership

BY John Neil The Ethics Centre 13 AUG 2019

We all know about toxic leaders. There are plenty of them around. Some are especially skilled with the ability to use their words to grind down anyone they perceive as a threat.

I call these leaders ototoxic – named after the medical description of drugs that cause adverse reactions to the ears’ cochlea or auditory nerves.

Ototoxicity is a distinctive quality of a poor leader, who can leave a trail of damage.

Ototoxic leaders betray themselves by a number of logical fallacies – hallmarks of their communication style. US President Donald Trump has given us plenty of examples during his presidency.

They play the person not the argument

The ototoxic leader will go after a person’s character or pick on a personal trait. They take aim at anything personal, but will avoid addressing the logical merits of the argument. This is known as an ad hominem fallacy.

Donald Trump critiqued fellow Republicans – “Lyin’ Ted” (Cruz), “Lil’ Marco” (Rubio), “Low Energy Jeb” (Bush). There were also repeated references to “Crooked Hillary”. He repeatedly accused opponents of being “too aggressive”, (usually a woman) or “not forceful enough” (usually a man), or in the case of “Lil’ Bob” Corker, of not being “tall” enough to be taken seriously.

They use straw-man arguments

An ototoxic leader will also exaggerate, or blatantly fabricate, an opposing point of view. This allows them to position their perspective as more reasonable and practical. In the third presidential debate before his election, Trump accused Hillary Clinton of advocating an open border policy, misquoting comments she made in relation to free trade. In a climate of widespread national hostility towards immigration, the border wall seemed to many as the more reasonable option.

In the workplace, an ototoxic leader will use overblown rhetoric to belittle someone else’s initiative, exaggerating potential cost overruns or overstating other risks in order to then position their proposal as the more reasonable one.

They appeal to hypocrisy

This defensive strategy turns an initial criticism back on the accuser. Trump used this rhetorical flourish during his presidency after refusing to face criticisms that he didn’t take a position on the violence following the Charlottesville rally. Rebutting the criticisms of neo-Nazis and the Ku Klux Klan, Trump maintained that ‘many others’ had also done bad things, implying they were equally culpable.

In the workplace, an ototoxic leader can often be heard defending their actions using the appeal to hypocrisy. “You think I’m aggressive? What about that meeting last week when you didn’t agree with me? You were just as bad, if not worse!”

They use the firefighter arsonist tactic

Named after the rare syndrome where firefighters light fires intentionally only to later arrive as a hero to put it out, the ototoxic leader will overly dramatise a potential problem, at the same time pointing the finger of blame at others for causing it. Once the situation reaches a critical mass, the ototoxic leader will then step in with a last-minute solution, ‘saving the day’.

Trump is well versed in this tactic. Stoking anti-Muslim sentiment as early as March 2011 with his calls for then President Obama to show his birth certificate and trading on unfounded ‘birther’ claims, Trump proceeded to inflame fears throughout the election campaign. He threatened the mass deportation of Syrian asylum seekers while promising to create a database of all Muslims in the US, along with making false claims of seeing ‘thousands and thousands’ of people in New Jersey celebrating the collapse of the World Trade Centre Towers in 2001. Trump stepped in to solve the ‘problem’ by signing his two travel bans within the first 100 days of his tenure.

More recently, Trump repeatedly covered himself in glory after meeting Kim Jong-un at their historic first summit in June 2018. Mere months after painting Kim as “Little Rocket Man” who, according to Trump posed the greatest threat to Western civilisation and was enabled by his predecessors who “should have been handled a long time ago”, following the summit Trump celebrated the “success” of the meeting. He waxed lyrical about the leaders “tremendous” relationship, including the beautiful “love letters” he received from the North Korean dictator in the lead up to the summit, while going on to extol the virtues of Kim, including his “great personality”, his sense of humour, intelligence and his negotiation abilities. Following the script of the hero who rides in to save the day, Trump tweeted that “everybody can now feel much safer than the day I took office…there is no longer a nuclear threat from North Korea.”

In the workplace, the ototoxic leader will spark a flame of disquiet around a project or strategy then proceed to escalate concerns – often through back channel politics – before presenting a grand ‘solution’ that saves the day.

Passive and aggressive

Ototoxic leaders can be aggressive or passive. The actively toxic communicator, who uses aggressive and intimidating language to subordinate others, can be bombastic, opinionated and openly dismissive of those who have different views. Their default mode of questioning almost exclusively involves closed questions (yes or no). Their inability to be open and listen to other’s views is usually a symptom of their lack of empathy.

The passive ototoxic leader is no less poisonous. In one-on-one settings, they are an impatient listener and will quickly interrupt their interlocutor in order to express their own view, often cutting the other person off in mid-sentence.

This ototoxic leader will tend to become frustrated in meetings if the consensus view is running contrary to theirs, to the point they will actively disengage from what’s going on in the room. They will resist all attempts to re-engage them by looking to shut down the conversation wherever possible.

Energy suckers

The net effect of the ototoxic leader’s tactics and communication style is to de-energise those they come into contact with.

Research shows that these de-energising ties have a disproportionate impact on an organisation’s culture. They are a ‘toxicity multiplier’, reducing the levels of individual performance, employee engagement and general well-being.

A disproportionate level of conflict between teams is generated and trust decreases. Rather than investing the energy to achieve their goals, those who work under an ototoxic leader spend a disproportionate amount of time analysing the relationship and devising strategies to palliate the person.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

United Airlines shows it’s time to reframe the conversation about ethics

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

The pivot: ‘I think I’ve been offered a bribe’

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

David Gonski on corporate responsibility

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Managing corporate culture

BY John Neil

As Director of Education and Innovation at The Ethics Centre, John collaborates closely with a talented team of specialists and subject matter experts to shape the tools, frameworks, and programs that drive our work forward. He brings a rich and varied background as a consultant, lecturer, and researcher, with expertise spanning ethics, cultural studies, sustainability, and innovation. This multidisciplinary perspective allows him to introduce fresh, thought-provoking approaches that energise and inspire our initiatives. John has partnered with some of Australia’s largest organisations across diverse industries, to place ethics at the heart of organisational life. His work focuses on education, cultural alignment, and leadership development to foster meaningful and lasting impact.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Save the date: FODI returns in 2020!

Save the date: FODI returns in 2020!

Opinion + AnalysisSociety + Culture

BY The Ethics Centre 7 AUG 2019

Festival of Dangerous Ideas (FODI), Australia’s original provocative ideas festival, returns in 2020 for its 10th festival. April 3 to 5 will be a milestone weekend of provocation, contemplation, critical thinking and preparation for the battles of the next decade.

Presented by The Ethics Centre, FODI 2020 will once again feature leading thinkers from Australia and around the world to interrogate the issues of today and prepare for the major shifts of tomorrow.

FODI Festival Director, Danielle Harvey said: “Over the past decade the number of avenues for people to talk and share their opinions has steadily increased, we are more connected than ever with like-minded people, but the cost has been significant. We are losing the ability to listen.

“Without the tools to listen to other opinions and contemplate new ideas, society risks fracturing like never before.”

“Without the tools to listen to other opinions and contemplate new ideas, society risks fracturing like never before. The Festival of Dangerous Ideas has always been an opportunity for deep thinking, carving out precious space for disagreement, difference of opinion and critical thinking.

“As we brace for 2020, FODI will celebrate its 10th anniversary by looking again to the future and presenting a cohort of FODI alumni, representing the world’s best thinkers, journalists, creators and specialists, giving Sydneysiders an opportunity to listen to what will be shaping the world tomorrow.”

The Ethics Centre Executive Director, Dr Simon Longstaff said:

“The Ethics Centre is thrilled to once again be presenting the Festival of Dangerous Ideas. One of The Ethics Centre’s strategic priorities is to build and sustain the ‘ethical infrastructure’ that underpins a free, dynamic and democratic society.

“Fragile societies break apart when challenged. The resilient cohere around a common desire to face the truth – even if it is hard to bear.”

“Fragile societies break apart when challenged. The resilient cohere around a common desire to face the truth – even if it is hard to bear. FODI tests the truth of the claim that we are a ‘civil’ society – and proves that even in moments of profound disagreement – we have the strength to live an ‘examined life’.”

Last year’s sell-out festival featured Stephen Fry, Rukmini Callimachi, Niall Ferguson, Megan Phelps-Roper, Chuck Klosterman and Toby Walsh.

More information, including the full program and festival venue, will be announced in the coming months. Visit festivalofdangerousideas.com to subscribe to be the first to hear our news.

MOST POPULAR

ArticleBeing Human

Putting the ‘identity’ into identity politics

ArticleHEALTH + WELLBEING

Parent planning – we should be allowed to choose our children’s sex

Article

Ethics Explainer: Respect

ArticleBeing Human

Praying for Paris doesn’t make you racist

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Drawing a line on corruption: Operation eclipse submission

Drawing a line on corruption: Operation eclipse submission

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + LeadershipPolitics + Human RightsSociety + Culture

BY The Ethics Centre 6 AUG 2019

The Ethics Centre (TEC) has made a submission to the NSW Independent Commission Against Corruption (ICAC) regarding its discussion paper, The Regulation of Lobbying, Access and Influence in NSW: A Chance To Have Your Say.

Released in April 2019 as part of Operation Eclipse, it’s public review into how lobbying activities in NSW should be regulated.

As a result of the submission TEC Executive Director, Dr Simon Longstaff has been invited to bear witness at the inquiry, which will also consider the need to rebuild public trust in government institutions and parliamentarians.

Our submission acknowledged the decline in trust in government as part of a broader crisis experienced across our institutional landscape – including the private sector, the media and the NGO sector. It is TEC’s view that the time has come to take deliberate and comprehensive action to restore the ethical infrastructure of society.

We support the principles being applied to the regulation of lobbying: transparency, integrity, fairness and freedom.

Key points within The Ethics Centres submission include:

-

- There is a difference between making representations to government on one’s own behalf and the practice of paying another person or party with informal government connections to advocate to government. TEC views the latter to be ‘lobbying’

-

- Lobbying has the potential to allow the government to be influenced more by wealthier parties, and interfere with the duty of officials and parliamentarians to act in the public interest

-

- No amount of compliance requirements can compensate for a poor decision making culture or an inability of officials, at any level, to make ethical decisions. While an awareness and understanding of an official’s obligations is necessary, it is not sufficient. There is a need to build their capacity to make ethical decisions and support an ethical decision making culture.

You can read the full submission here.

Update

Dr Simon Longstaff, Executive Director at The Ethics Centre, presented as a witness to the Commission on Monday 5 August. You can read the public transcript on the ICAC website here.

MOST POPULAR

ArticleBeing Human

Putting the ‘identity’ into identity politics

ArticleHEALTH + WELLBEING

Parent planning – we should be allowed to choose our children’s sex

Article

Ethics Explainer: Respect

ArticleBeing Human

Praying for Paris doesn’t make you racist

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Should you be afraid of apps like FaceApp?

Should you be afraid of apps like FaceApp?

Opinion + AnalysisRelationshipsScience + Technology

BY Matthew Beard 30 JUL 2019

Until last week, you would have been forgiven for thinking a meme couldn’t trigger fears about international security.

But since the widespread concerns over FaceApp last week, many are asking renewed questions about privacy, data ownership and transparency in the tech sector. But most of the reportage hasn’t gotten to the biggest ethical risk the FaceApp case reveals.

What is FaceApp?

In case you weren’t in the know, FaceApp is a ‘neural transformation filter’.

Basically, it uses AI to take a photo of your face and make it look different. The recent controversy centred on its ability to age people, pretty realistically, in just a short photo. Use of the app was widespread, creating a viral trend – there were clicks and engagements to be made out of the app, so everyone started to hop on board.

Where does your data go?

With the increasing popularity comes increasing scrutiny. A number of people soon noticed that FaceApp’s terms of use seemed to give them a huge range of rights to access and use the photos they’d collected. There were fears the app could access all the photos in your photo stream, not just the one you chose to upload.

There were questions about how you could delete your data from the service. And worst of all for many, the makers of the app, Wireless Labs, are based in Russia. US Minority Leader Chuck Schumer even asked the FBI to investigate the app.

The media commentary has been pretty widespread, suggesting that the app sends data back to Russia, lacks transparency about how it will or won’t be used and has no accessible data ethics principles. At least two of those are true. There isn’t much in FaceApp’s disclosure that would give a user any sense of confidence in the app’s security or respect for privacy.

Unsurprisingly, this hasn’t amounted to much. Giving away our data in irresponsible ways has become a bit like comfort eating. You know it’s bad, but you’re still going to do it.

The reasons are likely similar to the reasons we indulge other petty vices: the benefits are obvious and immediate; the harms are distant and abstract. And whilst we’d all like to think we’ve got more self-control than the kids in those delayed gratification psychology experiments, more often than not our desire for fun or curiosity trumps any concern we have over how our data is used.

Should you be worried?

Is this a problem? To the extent that this data – easily accessed – can be used for a range of goals we likely don’t support, yes. It also gives rise to a range of complex ethical questions concerning our responsibility.

Let’s say I willingly give my data to FaceApp. This data is then aggregated and on-sold in a data marketplace. A dataset comprising of millions of facial photos is then used to train facial recognition AI, which is used to track down political dissidents in Russia. To what extent should I consider myself responsible for political oppression on the other side of the world?

In climate change ethics, there is a school of thought that suggests even if our actions can’t change an outcome – for instance, by making a meaningful reduction to emissions – we still have a moral obligation not to make the problem worse.

It might be true that a dataset would still be on sold without our input, but that alone doesn’t seem to justify adding our information or throwing up our arms and giving up. In this hypothetical, giving up – or not caring – means abandoning my (admittedly small) role in human rights violations and political injustice.

A troubling peek into the future

In reality, it’s really unlikely that’s what FaceApp is actually using your data to do. It’s far more likely, according to the MIT Technology Review, that your face might be used to train FaceApp to get even better at what it does.

It might use your face to help improve software that analyses faces to determine age and gender. Or it might be used – perhaps most scarily – to train AI to create deepfakes or faces of people who don’t exist. All of this is a far cry from the nightmare scenario sketched out above.

But even if my horror story was accurate, would it matter? It seems unlikely.

By the time tech journalists were talking about the potential data issues with FaceApp, millions had already uploaded their photos into the app. The ship had sailed, and it set off with barely a question asked of it. It’s also likely that plenty of people read about the data issues and then installed the app just to see what all the fuss is about.

Who is responsible?

I’m pulled in two directions when I wonder who we should hold responsible here. Of course, designers are clever and intentionally design their apps in ways that make them smooth and easy to use. They eliminate the friction points that facilitate serious thinking and reflection.

But that speed and efficiency is partly there because we want it to be there. We don’t want to actually read the terms of use agreement, and the company willingly give us a quick way to avoid doing so (whilst lying, and saying we have).

This is a Faustian pact – we let tech companies sell us stuff that’s potentially bad for us, so long as it’s fun.

The important reflection around FaceApp isn’t that the Russians are coming for us – a view that, as Kaitlyn Tiffany noted for Vox, smacks slightly of racism and xenophobia. The reflection is how easily we give up our principled commitments to ethics, privacy and wokeful use of technology as soon as someone flashes some viral content at us.

In Ethical by Design: Principles for Good Technology, Simon Longstaff and I made the point that technology isn’t just a thing we build and use. It’s a world view. When we see the world technologically, our central values are things like efficiency, effectiveness and control. That is, we’re more interesting in how we do things than what we’re doing.

Two sides of the story

For me, that’s the FaceApp story. The question wasn’t ‘is this app safe to use?’ (probably no less so than most other photo apps), but ‘how much fun will I have?’ It’s a worldview where we’re happy to pay any price for our kicks, so long as that price is hidden from us. FaceApp might not have used this impulse for maniacal ends, but it has demonstrated a pretty clear vulnerability.

Is this how the world ends, not with a bang, but with a chuckle and a hashtag?

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships

The role of the ethical leader in an accelerating world

Big thinker

Relationships

Big Thinker: bell hooks

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Why we should be teaching our kids to protest

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships