Ethics programs work in practise

Ethics programs work in practise

Opinion + AnalysisSociety + Culture

BY The Ethics Centre ethics 19 DEC 2018

New research released today reveals that organisations with clear ethics programs are more likely to be seen as responsible in their business practises by their employees.

The new survey, undertaken by The Institute of Business Ethics (IBE) in partnership with our team at The Ethics Centre (TEC) found that the majority of Australian employees are aware that their organisations have each of the building blocks of an ethics program; a code of ethics, training, and a ‘speak up’ line.

“Ethics at Work” was launched to The Ethics Alliance members this morning through an intimate panel discussion that explored the implications of the findings, featuring Philippa Foster Back of IBE, John Neil and Cris Parker of TEC and Jill Reich of Uniting.

The survey reveals that awareness of ethics programs positively impact how employees feel their company deals with stakeholders. Those with an ethics program are significantly more likely to feel that their organisation acts responsibly in business dealings, at 84 percent. This compares to less than half of those without an ethics program (49 percent). There was one counter-intuitive result where 42 percent agreed their line manager rewards employees who get good results even if it’s through questionable practises.

We’ve spent the last 30 years working with individual organisations to establish ethical frameworks, and worked with many major organisations in recovery from ethical failure. The impact of clear lived values and principles at all levels of an organisation is tremendous, and instrumental to a positive, supportive culture.

The survey also illuminated the role managers play in upholding behaviours within the workplace. Managers were more likely than non-managers to view their organisation positively, both in engagement with stakeholders (77 percent vs 71 percent), and in application of social policy (75 percent vs 67 percent).

It further identifies pressures felt and attitudes toward management positions:

- Managers are more likely to feel pressure to compromise their ethical standards than those not in a management position (by nine percent)

- They were also much more likely to have lenient views toward charging personal entertainment as expenses and using company petrol for mileage

- Employees who have felt pressure to compromise their ethical standards were also more likely to feel their manager failed to promote/reward ethical behaviour (43 percent).

At an employee level, almost one in four reported awareness of misconduct in the workplace, yet worryingly only one in three of those workers decided to speak up.

Of those who have experienced misconduct at work, the most common types were bullying and harassment (41 percent), inappropriate or unethical treatment of people (39 percent) and misreporting of working hours (32 percent).

In addition, more than one in ten (13 percent) have felt pressured to compromise their ethical standards in the workplace.

The Ethics Centre, and our membership program The Ethics Alliance are committed to raising the ethical standards of business in Australia. To find out more about our work visit www.ethics.org.au

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture

Ask an ethicist: Am I falling behind in life “milestones”?

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships, Society + Culture

You won’t be able to tell whether Depp or Heard are lying by watching their faces

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships, Society + Culture

The ethics of tearing down monuments

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Society + Culture

The Ethics Centre: A look back on the highlights of 2018

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

BY ethics

'Vice' movie is a wake up call for democracy

‘Vice’ movie is a wake up call for democracy

Opinion + AnalysisSociety + Culture

BY Aisyah Shah Idil 18 DEC 2018

America has sold a unique brand of exceptionalism.

Some say no modern nation surpasses its military, economic, scientific and cultural prowess. Prominent Americans revere their country as an “empire of liberty”, a “shining city on a hill”, the “last best hope on Earth,” and the “leader of the free world”.

These enduring paeans are an apparent result of America’s political philosophy. By privileging individual freedom for every citizen, the American finds themselves in a unique position all of the time: whenever they choose to do something, they exercise a political right.

This choice has come to be sacred. Vice is about the lengths a self-proclaimed patriot will go to protect it.

When director Adam McKay’s film The Big Short earned him an Oscar for screenwriting, audiences discovered the former SNL comic’s hidden skill – turning concepts that usually made people feel bored or stupid, engaging and funny.

It’s our luck that after the tenth anniversary of 2008 financial crisis, and one month after George H. W. Bush’s funeral, his next target of irreverence would be the shadowy figure of Dick Cheney.

Far from a hagiography, Vice – carried seamlessly by an unrecognisable lead in Christian Bale and a cuttingly ambitious Amy Adams as his wife Lynne – seems an unambiguous condemnation of the Bush-Cheney administration, an ancestor of today’s American right.

This is no typical biopic.

There are no sweeping landscapes and sombre confessionals in red-curtained studios, nor any attempt to feign journalistic objectivity. No off-screen interviewer neatly ties the narrative together and the fourth wall is broken in the first ten minutes.

Absurdity, characters addressing the viewer directly, and thick visual metaphors give Viceits unique personality (wait till you see the scene with the heart). McKay wants you to know he is speaking directly to you. This isn’t a squared off paragraph confined to history books. It is what shaped our present.

Make no mistake: just because it’s opinionated doesn’t mean it isn’t well researched. McKay told the New York Times that the movie encompassed “five decades of Cheney’s life, 200 locations and more than 150 speaking parts”. According to him, a more measured, less confrontational tone wouldn’t have suited the OTT political circus we live in now. “Why be subtle anymore?”

While a conservative backlash is to be expected, this Cheney is no bloodless monster. He’s human. An idealist. His tender love for his daughters and unquestioning devotion to his wife are the same qualities that bond him to the bawdy Donald Rumsfeld (Steve Carell), and the ranks of a post-Watergate GOP.

He’s a creature of a slower, sweeter time: honed by long scenes of fly-fishing and the vast plains of Wyoming. McKay contrasts this with the energetic, M&M crunching Bush, played by a chameleon-like Sam Rockwell.

Cheney watches and waits. And watches and waits. He leaves no trace. And he is in it for the long haul.

At its core, Vice is a story about democracy. It is a warning that the halls of power rarely grant wishes without demanding a sacrifice, and too often this sacrifice begins with stripping the humanity of the powerless. It is about the special accomplishment of the individual who advances into public life when retreating into privacy is the easiest and most natural thing to do.

It is an admission that envy, chronic discontent and loneliness are intrinsic to democracy, but that its expansive collectivism are how to combat it. It’s all of this, and a demand to keep paying attention.

In his letters, Alexis de Tocqueville speaks of his ambition “to point out if possible to men what to do to escape tyranny and debasement in becoming democratic.”

Philosopher Alexandre Lefebvre offers the following:

“He [Tocqueville] seems to say that tyranny and debasement are part and parcel of becoming democratic. But… [it] works the other way around as well: that in becoming democratic – that is, in becoming properly democratic, democratic in the right way – we can hope to escape the new kinds of tyranny and debasement that democracy brings about…

For as Tocqueville exhorts himself in an unpublished note, we must “use Democracy to moderate Democracy. It is the only path open to salvation to us.”

McKay, and Cheney, would agree.

Vice is released in movie theatres 26 December 2018.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships, Society + Culture

Extending the education pathway

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture

David Lynch’s most surprising, important quality? His hope

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture

Lisa Frank and the ethics of copyright

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

I’d like to talk to you: ‘The Rehearsal’ and the impossibility of planning for the right thing

BY Aisyah Shah Idil

Aisyah Shah Idil is a writer with a background in experimental poetry. After completing an undergraduate degree in cultural studies, she travelled overseas to study human rights and theology. A former producer at The Ethics Centre, Aisyah is currently a digital content producer with the LMA.

The Ethics Centre: A look back on the highlights of 2018

The Ethics Centre: A look back on the highlights of 2018

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + LeadershipSociety + Culture

BY The Ethics Centre 18 DEC 2018

Sometimes, good people do bad things. The last year confirmed this. Banks, schools, universities, the military, religious institutions – it seems 2018 left no sector unshaken.

These are the sorts of issues we confront every day at The Ethics Centre. In our reviews and confidential advice we have seen similar patterns repeat over and over again.

Yes, bad apples may exist, but we find ethical issues arise from bad cultures. And even our most trusted institutions, perhaps unwittingly, foster bad behaviour.

That’s why we have an important job. With your support we help society understand why ethical failures happen and provide safeguards lest they repeat.

As The Ethics Centre approaches its 30th birthday, we’d love to say we’re no longer needed. We hoped to bring ethics to the centre of everyday life and think we’ve made a small dent into that task. But there’s no point pretending there’s not a long way to go.

We thank you for supporting us and believing in us and are proud to share the highlights of another busy year with you.

If you’re short on time to read the full report now (and we’d really love you to take a look some time at what a small organisation like ours can achieve), here are seven highlights we’re particularly proud of:

• We launched The Ethics Alliance. A community of organisations unified by the desire to lead, inspire and shape the future of how we do business. In one year, 37 companies have benefited from the innovative tools that help staff at all levels make better decisions.

• We published a paper on public trust and the legitimacy of our institutions. Our conversations with regulators, investors, business leaders and community groups, revealed a sharp decline in the trust of our major institutions. We identify the agenda they need to in order to maintain public trust and contribute meaningfully to the common good.

• We ramped up Ethi-call. Calls to our free, independent, national helpline increased by 74 per cent this year. That’s even more people to benefit from impartial, private guidance from our highly trained ethical counsellors.

• We reviewed the culture of Australian cricket. When the ball-tampering scandal hit the world stage, Cricket Australia asked us to investigate. We uncovered a culture of ambition, arrogance, and control, where “winning at all costs” indicted administrators and players alike.

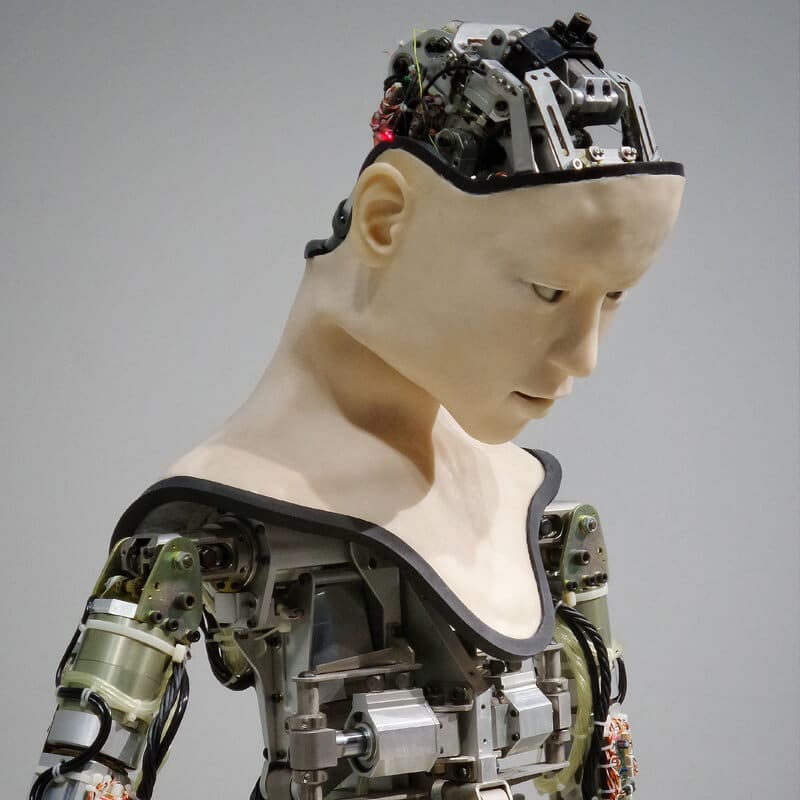

•We released a guide to designing ethical tech. Technology is transforming the way we experience reality. The need to make sure we don’t sacrifice ethics for growth is more pressing than ever. We propose eight principles to guide the development of all new technologies before they hit the market. You can download it here.

•We redesigned the Festival of Dangerous Ideas. FODI was created to facilitate courageous public conversation. The Ethics Centre and UNSW’s Centre for Ideas collaborated to untether the festival and produce a bold and necessary world-class cultural event. Every session sold out.

• We grew our tenth year of IQ2. We doubled the number of live attendees and tripled the student base showing audiences are more intelligent and hungry for diverse ideas than they are often given credit for. We welcomed a new sponsor Australian Ethical whose values align with our own. There’s never been a better time to support smart, civic, public debate.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Big thinker

Relationships, Society + Culture

Big Thinker: Socrates

Big thinker

Society + Culture, Business + Leadership

Big Thinker: Ayn Rand

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Society + Culture

Alpha dogs and the toughness trap: How we can redefine modern masculinity

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

If we’re going to build a better world, we need a better kind of ethics

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

5 Movies that creepily foretold today’s greatest ethical dilemmas

5 Movies that creepily foretold today’s greatest ethical dilemmas

Opinion + AnalysisRelationshipsSociety + Culture

BY Aisyah Shah Idil 18 DEC 2018

Climate change. Nuclear war. Artificial intelligence. A new pandemic.

According to the non-profit organisation 80,000 Hours, these are the greatest threats to humanity today. Yet the big movie studios have been calling it for decades and were pondering the ethics behind these threats long ago.

1. Planet of the Apes (1968)

Seeing Charlie Heston scream in despair at a shattered Statue of Liberty still spooks the most apathetic viewer. And it’s as shocking a warning against nuclear weapons now as it was in the middle of the Cold War 50 years ago.

In Planet of the Apes, humans are being hunted. The primates they once experimented on have grown into intelligent, complex, political creatures. Humanity has regressed into primitive vermin to either be killed outright, enslaved, or used in scientific experiments. The strict ape hierarchy demands utility over compassion, holding a mirror up to the same vices that led humanity to destruction.

—————

2. 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968)

When a survey of living computer science researchers shows half think there’s a greater than 50 percent chance of “high-level machine intelligence” – one that reaches then exceeds human capabilities – it’s right to be concerned.

2001: A Space Odyssey begins with a jaunty trip to Jupiter. An optimistic team is led aboard by HAL 9000, the ship’s computer, but begin to suspect there’s more to the trip than they’ve been told.

After all, there are two sides to the utilitarian coin. What is murder to us is just programming to a robot.

—————

3. The Matrix (1999)

If reality is a simulation by super intelligent sentient machines, what does any self-respecting hacker do? Start a rebellion.

The Matrix goes even further than 2001: A Space Odyssey. Here, the machines are Descartes’ evil demon, unsatisfied with just killing us. Instead, they mine us for energy to survive, and keep us subservient on a diet of virtual reality. A world of love, work, boring parties, and paying bills occupy us while they use us as slaves.

The point of tension in The Matrix centres around the theory of Plato’s Cave. If you know what everyone is experiencing is an illusion, should you tell them?

—————

4. 28 Days Later (2002)

28 Days Later paints a bleak picture of a world unprepared to deal with the effects of an aggressive pandemic. And it’s not as unbelievable as it may seem. According to 80,000 Hours, the money invested into pandemic research isn’t nearly as much as we need.

From HIV-AIDS, Ebola, and Zika, we’ve seen countries drag their feet over who pays to contain one, or struggle to move people and supplies to where they’re needed.

“When you’re in the middle of a crisis and you have to ask for money”, says Dr. Beth Cameron at the Nuclear Threat Initiative, “you’re already too late”.

—————

5. Children of Men (2006)

What is arguably more important than any of these things is hope. And that’s what our last movie recommendation is about.

After two decades of unexplained female infertility, war, and anarchy, human civilisation is on the brink of collapse. Civil servant Theo Faron has lost all hope as the last generation of his species. Then he meets Kee – an illegal immigrant and the first woman to be pregnant in eighteen years.

The hope for a better future, for a future that is more just and more compassionate, adds intangible meaning to our struggles today. It becomes reasonable to struggle, to suffer, and even to die for this kind of hope.

What makes the hope of today different is that we are now closer to “hypotheticals” than we have ever been.

Are we prepared to turn this hope into action? Effective altruism offers one way to find out.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Why your new year’s resolution needs military ethics

Big thinker

Relationships

Seven Female Philosophers You Should Know About

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Begging the question

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Is masculinity fragile? On the whole, no. But things do change.

BY Aisyah Shah Idil

Aisyah Shah Idil is a writer with a background in experimental poetry. After completing an undergraduate degree in cultural studies, she travelled overseas to study human rights and theology. A former producer at The Ethics Centre, Aisyah is currently a digital content producer with the LMA.

Want your kids to make good decisions? Here’s what they need to learn

Want your kids to make good decisions? Here’s what they need to learn

Opinion + AnalysisHealth + Wellbeing

BY Matthew Beard 12 DEC 2018

Ask just about any parent what they want for their children and they’ll give you roughly the same answers: we want our kids to be happy, healthy and – perhaps most importantly – good.

For many parents, the goal is to raise children who are better than they are, contribute positively to the world around them, challenge cruelty, injustice and ignorance in the world and make a positive difference in other people’s lives.

Basically, what they’re wanting is that their kids grow up to be ethical people. So, if that’s what so many of us want, it’s worth understanding exactly what ethics is and how we might light the ethical spark in the next generation.

Ethics is a branch of philosophy – it asks questions about the nature of goodness, what makes something right and wrong, and what makes life worth living. As a branch of philosophy, it also leaves no stone unturned. It interrogates any and every claim about what’s right, what’s wrong and what’s ‘normal’.

Whenever we make a choice, we change the world in some small way. Before us are a whole bunch of different possible worlds – it’s up to us to decide which one we’ll turn into reality. Ethics helps us make sure we’re choosing the best of those possible worlds, but it takes practice to do it well.

That means if we’re going to help our kids be ethical people, we need to model ethical thinking in our homes and classrooms, on sports fields and video games and wherever kids are making decisions.

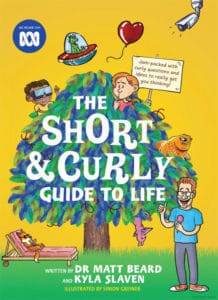

But how do we do it? Here are a few tried and true techniques the ABC’s Short & Curly team have used over the last few years.

1. Don’t be afraid to say ‘I don’t know’

It can be scary to say “I don’t know” – especially when we’re having a conversation with kids. As adults, we’re supposed to have all the answers, right? The problem is, sometimes we don’t. And neither do the young people we’re talking to.

The more we pretend we know it all, the more self-conscious others feel about engaging us in a real conversation, or worse – disagreeing with us! Philosophers use discussions and debate as a team activity – we use disagreement and criticism as a way to work together to find out what’s true.

What’s more, our beliefs about how the world works are often conditioned on what we’ve learned or been told is normal. What we know about fairness, honesty or whatever the topic is might not be the final answer – it could be conditioned by norms and beliefs we’ve been conditioned to believe, even if they don’t hold up to close analysis.

2. Be imaginative

Martha Nussbaum, one of the world’s pre-eminent philosophers, says “you can’t really change the heart without telling a story.” We’re narrative creatures – we’ve always used parables, fables, literature and film as ways of understanding the world around us.

Philosophers have tested their ideas through thought experiments and hypotheticals throughout time. They’re super weird, but they make for great road-trip fodder or dinner table debates.

Ethical reflection demands imagination. It requires us to be able to understand experiences we haven’t lived through and to empathise with people who might be radically different to us.

The next time you’re reading a book or watching a movie with your young one, that’s a moment for reflection. Did those characters do the right thing? How do you think that person felt? Would it have been OK if they’d broken that promise?

3. Don’t shut down a question

Some of our favourite one liners are actually really good ways of undermining ethical conversations. “Everybody does it”, “because I said so” and “you’ll understand when you’re older” are good examples. They rely on authority, tradition or experience as ways to cut off what might be a more productive conversation.

Sometimes, there’s not time for an ethical discussion, but rather than shutting it off with a one-liner, make a commitment to talk about it in more detail later, when you’ve got more time to explain yourself.

4. Question your assumptions

Our minds love telling stories – and we hate plot holes. If we don’t have the full story, we’ll often fill in the gaps with assumptions or inferences that don’t capture the full picture. Ethical conversations work best when they start by questioning what we think we know for sure. Are we starting our discussion on a good foundation?

5. Be curious and research

As well as checking our assumptions, ethics requires us to be curious and informed about the world around us. As much as many philosophers would beg to differ, we can’t understand the world from an armchair.

We need to do some research and uncover relevant facts. Bonus – while you’re doing some research together, you might be able to work together to understand the difference between a fact and an opinion, spot dodgy sources or filter out fake news.

6. Listen to and test your emotional responses

Our emotions are an important part of the way we make judgements, but they can sometimes run wild and lead us astray. Just because we find something disgusting, offensive or hurtful, doesn’t make it wrong. And just because we find something pleasant, fun or funny doesn’t mean it’s OK.

Add “yuck” and “yum” to your list of banned arguments – just because something makes you feel squeamish doesn’t make it bad. Listen to your emotions, but get curious about them – they need to be tested like everything else.

One final note: these tips won’t guarantee a kid won’t do the wrong thing sometimes – like all of us. But it will help you have a shared language for communicating, in a meaningful way, why what they did was wrong.

We all make judgements – it’s part of who we are – ethics helps us build the skills and character to ensure we’re making those judgements in ways that are alive to the world around us and the people within it. And like any skill, it’s easier to master if you start young.

The Short & Curly Guide to Life

What makes something good or bad?

Why are things the way they are? How come it’s so hard to work out the right thing to do? The Short & Curly Guide to Life is an imaginative look at some of life’s biggest and trickiest questions. Figuring out what’s right is way more fun than you think!

Short & Curly Guide to Life is on sale at book stores around Australia and via major online retailers. You can also tune into the ABC Radio podcast, Short & Curly, here.

Matt Beard is the resident philosopher on the ABC Podcast Short & Curly, and the author of The Short & Curly Guide to Life (Penguin Random House). Find him on Twitter @matthewtbeard

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Seven COVID-friendly activities to slow the stress response

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Exercising your moral muscle

Big thinker

Health + Wellbeing, Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Big Thinker: Judith Butler

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

It’s easy to ignore the people we can’t see

BY Matthew Beard

Matt is a moral philosopher with a background in applied and military ethics. In 2016, Matt won the Australasian Association of Philosophy prize for media engagement. Formerly a fellow at The Ethics Centre, Matt is currently host on ABC’s Short & Curly podcast and the Vincent Fairfax Fellowship Program Director.

Ethics Explainer: Existentialism

If you’ve ever pondered the meaning of existence or questioned your purpose in life, you’ve partaken in existentialist philosophy.

It would be hard to find someone who hasn’t asked themselves the big questions. What is the meaning of life? What is my purpose? Why do I exist? For thousands of years, these questions were happily answered by the belief your purpose in life was assigned prior to your creation. The existentialists, however, disagreed.

Existentialism is the philosophical belief we are each responsible for creating purpose or meaning in our own lives. Our individual purpose and meaning is not given to us by Gods, governments, teachers or other authorities.

In order to fully understand the thinking that underpins existentialism, we must first explore the idea it contradicts – essentialism.

Essentialism

Essentialism was founded by the Greek philosopher Aristotle who posited everything had an essence, including us. An essence is “a certain set of core properties that are necessary, or essential for a thing to be what it is”. A book’s essence, for example, is its pages. It could have pictures or words or be blank, be paperback or hardcover, tell a fictional story or provide factual information. Without pages though, it would cease to be a book. Aristotle claimed essence was created prior to existence. For people, this means we’re born with a predetermined purpose.

This idea seems to imply, whether you’re aware of it or not, that your purpose in life has been determined prior to your birth. And as you live your life, the decisions you make on a daily basis are contributing to your ultimate purpose, whatever that happens to be.

This was an immensely popular belief for thousands of years and gave considerable weight to religious thought that placed emphasis on an omnipotent God who created each being with a predetermined plan in mind.

If you agreed with this thinking, then you really didn’t have to challenge the meaning of life or search for your purpose. Your God already provided it for you.

Existence precedes essence

While philosophers including Søren Kierkegaard, Fyodor Dostoyevsky and Friedrich Nietzsche questioned essentialism in the 19th century, existentialism was popularised by Jean-Paul Sartre in the mid-20th century following the horrific events of World War II.

As people questioned how something as catastrophically terrible as the Holocaust could have a predetermined purpose, existentialism provided a possible answer that perhaps it is the individual who determines their essence, not an omnipotent being.

The existentialist movement asked, “What if we exist first?”

At the time it was a revolutionary thought. You were created as a blank slate, tabula rasa, and it is up to you to discover your life’s purpose or meaning.

While not necessarily atheist, existentialists believe there is no divine intervention, fate or outside forces actively pushing you in particular directions. Every decision you make is yours. You create your own purpose through your actions.

The burden of too much freedom

This personal responsibility to shape your own life’s meaning carries significant anxiety-inducing weight. Many of us experience the so-called existential crisis where we find ourselves questioning our choices, career, relationships and the point of it all. We have so many options. How do we pick the right ones to create a meaningful and fulfilling life?

“Man is condemned to be free; because once thrown into the world, he is responsible for everything he does” – John-Paul Sartre

Freedom is usually presented positively but Sartre posed that your level of freedom is so great it’s “painful”. To fully comprehend your freedom, you have to accept that only you are responsible for creating or failing to create your personal purpose. Without rules or order to guide you, you have so much choice that freedom is overwhelming.

The absurd

Life can be silly. But this isn’t quite what existentialists mean when they talk about the absurd. They define absurdity as the search for answers in an answerless world. It’s the idea of being born into a meaningless place that then requires you to make meaning.

The absurd posits there is no one truth, no inherent rules or guidelines. This means you have to develop your own moral code to live by. Sartre cautioned looking to authority for guidance and answers because no one has them and there is no one truth.

Living authentically and bad faith

Coined by Sartre, the phrase “living authentically” means to live with the understanding of your responsibility to control your freedom despite the absurd. Any purpose or meaning in your life is created by you.

If you choose to live by someone else’s rules, be that anywhere between religion and the wishes of your parents, then you are refusing to accept the absurd. Sartre named this refusal “bad faith”, as you are choosing to live by someone else’s definition of meaning and purpose – not your own.

So, what’s the meaning of life?

If you’re now thinking like an existentialist, then the answer to this question is both elementary and infinitely complex. You have the answer, you just have to own it.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

WATCH

Relationships

What is ethics?

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

What ethics should athletes live by?

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

The Dark Side of Honour

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

The problem with Australian identity

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Is it ethical to splash lots of cash on gifts?

Is it ethical to splash lots of cash on gifts?

Opinion + AnalysisRelationships

BY Aisyah Shah Idil 10 DEC 2018

Whether you’re a tearer, a folder, a scruncher, or a chucker, there’s nothing like opening a wrapped gift that’s especially suited to you.

Amid the hugs and backslaps it’s hard to say who it’s more satisfying for – the giver or the receiver.

But when little Millie gets the new PlayStation while Amir’s staring at his plastic water gun, the thin film of politeness peels away. We don’t just wonder why we have the gifts we do. We wonder how much they cost.

This holiday season, we’re exploring the ethical dimensions of splurging on gifts. Are there unspoken rules for those with deeper pockets? Is it killing the spirit of generosity to peer at the price tag? Or is keeping mum about money letting us pretend we don’t owe things to each other all the time?

Christmas conundrums? Book a free appointment with Ethi-call. A non-partisan, highly trained professional will help you navigate any ethical minefields this holiday season.

There are so many different kinds of purposes tied to gift giving on Christmas, or any large celebration. We like to think of these sorts of gifts as intrinsically good, making them different from bribes given for personal gain.

For some, gifts are an informal way to foster love and support in mutual relationships. They encourage closeness and dependencies between social circles to reveal links our individualism tends to hide.

They’re known to shape our moral character and encourage selfless generosity, even to remove feelings of emotional debt that have accumulated throughout the year. Though we speak of gifts as just ways to “show love and appreciation”, our reasons are often more layered than that.

This doesn’t have to be self-indulgent navel-gazing. Examining the purpose of a gift matters because it encourages us to consider if that special, one-of-a-kind purchase is the only way to fulfil it. What duties or consequences should you consider before making that jump?

The duties of gifting

If you are feeling the end of year pinch, you have a duty to yourself to make sure the gift giving season doesn’t put you into financial strife. But if that conflicts with the duty to be fair to your friends and family, ask yourself what matters more. After all, gifts are often an exchange, and appreciating someone’s thoughtfulness can come with offering a similarly tasteful gift of your own.

If the gift is for a friend or peer, we might worry about setting an expectation or precedent we can’t fulfil. If it’s for someone who would struggle to fork out a similar amount of money for a gift, would this leave them feeling uncomfortably tied to you? And if you want to spread the holiday cheer, this leaves your pool of lucky recipients fairly limited.

Nor can the growing consciousness around our impact on the environment be ignored. Are these gifts worth the cost to landfills, unethical supply chains, and our collective duty to preserve the health of the land we live on?

But let’s not dwell on the negative. There are heaps of positive consequences too. Don’t forget the good that comes from making the people around you feel extra special and appreciated. If you struggle with miserliness, or excessive penny pinching, this could be a win-win way to encourage generosity in you, and make someone else very happy. It’s always worth thinking of how your actions reflect your character.

When all is said and done, the holidays are a time to rest. The softening pleasures of food, drink, company and play don’t have to get in the way of a well examined life. In fact, slowing down our frenetic, demanding lives to allow time to recuperate may be just what we need most: the modest admission that we cannot do everything perfectly. Good enough is good enough.

That’s the spirit!

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

Community is hard, isolation is harder

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Ethics

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture, Relationships

Do we exaggerate the difference age makes?

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Paralympian pay vs. Olympian pay

BY Aisyah Shah Idil

Aisyah Shah Idil is a writer with a background in experimental poetry. After completing an undergraduate degree in cultural studies, she travelled overseas to study human rights and theology. A former producer at The Ethics Centre, Aisyah is currently a digital content producer with the LMA.

The historical struggle at the heart of Hanukkah

The historical struggle at the heart of Hanukkah

Opinion + AnalysisRelationships

BY Aisyah Shah Idil 7 DEC 2018

Before there were candles and doughnuts, there was a Greek king and some very pissed off Jews.

Right now, Jews all around the world are observing Hanukkah. It began on the 2nd of December and will last until the 10th.

Even though it’s nicknamed “The Festival of Lights” for its distinctive candles, Hanukkah is also a nod to military rebellion. Here’s how the story goes.

It’s the second century BCE. The Greek Selucid Empire is in power and Antiochus, the king, wants the Jewish community to finally abandon their traditions and fully embrace wider Greek culture.

Some Jews had already assimilated. But for Antiochus to have total control over the empire, the pocket of devout ones need to as well. Since they’re not giving up without a fight, he decides imperial force is necessary.

Antiochus vandalises their most sacred temple and bans Jews from praying or performing ritual sacrifice there. An altar to Zeus is propped up, pigs are sacrificed on it, Sabbath is forbidden and circumcision is banned. Dissenters are killed. Judaism is outlawed by the state.

Predictably, there is large scale revolt. The Maccabees, a Jewish warrior family, violently seize the temple back. Once they and their allies purify it to their standards and replace the pagan icons with their own, they finally light the menorah, the sacred lampstand in the temple.

There’s only just enough oil to light the candles for one day. But according to legend, these candles miraculously stayed lit for eight entire days, marking them as a victorious time of “joy and honour”.

This is why on Hanukkah, Jews traditionally eat festive foods fried in oil and light their own lamps. Each day, they eat potato fritters called latkes and jelly doughnuts called soufjanyiot, sing special songs, play dreidel games and recite prayers. People give presents and money, and kids get chocolate coins. It’s an eight-day feast of leisure.

But it wasn’t always like that. Some rabbis have understandably been uncomfortable with Hanukkah’s military undertones. Others have pointed out that celebrating the conflict between Jewish secularism and fundamentalism is a little odd.

But with the advent of Zionism and the state of Israel, Hanukkah has taken on new life. From a minor holiday that emphasised the miracle of the oil, Hanukkah today is seen as a symbol of resistance against injustice and oppression.

It’s now been nearly eight decades since the Holocaust. There is a menorah in Midtown Manhattan dedicated to the victims of the Pittsburgh synagogue mass shooting. There is another in front of Brandenburg Gate where the Nazi flags once hung.

Amid rising concern over anti-Semitism, illiberalism in Israel, and contradictions of ‘Jewish Christmas’, maybe it’s the historical struggle at the heart of Hanukkah that is the most Jewish thing of all.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

What we owe to our pets

Big thinker

Health + Wellbeing, Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Big Thinker: Judith Butler

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Appreciation or appropriation? The impacts of stealing culture

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

Beyond cynicism: The deeper ethical message of Ted Lasso

BY Aisyah Shah Idil

Aisyah Shah Idil is a writer with a background in experimental poetry. After completing an undergraduate degree in cultural studies, she travelled overseas to study human rights and theology. A former producer at The Ethics Centre, Aisyah is currently a digital content producer with the LMA.

Ethics Explainer: Hope

We hope for fine weather on weekends and the best for our buddies – an obvious statement that hardly screams ethics.

But within our everyday desires for good things, lies a duty to each other and ourselves to only act on reasonably held hopes.

The ethics of hope

One of Immanuel Kant’s simple but resonant maxims is ‘ought implies can’. In other words, if you believe someone has an ethical responsibility to do something, it must be possible. No person is under any obligation to do what is impossible. You might call me a bad person for failing to fly through the sky and save someone falling from a great height. But your condemnation will be rejected as ill-founded for the simple reason only fictional characters can perform that feat.

Many other things – including extremely difficult things – are reasonably expected of others. A person might promise to climb Mount Everest (or at least make a serious attempt) prior to their 50thbirthday. This might present the greatest challenge imaginable. Yet we know scaling the heights of Everest is possible. As such, the person who made this promise is bound to honour their commitment.

Of course, at the time of making such a promise, no person can know with absolute certainty they will be able to meet the obligation they have taken on. There are just too many variables outside of their control that can frustrate their best laid plans. Weather conditions might lead to the closure of the mountain. The need to provide personal care to a loved one could extend well beyond any anticipated period. Given this, our ethical commitments are almost always tinged with a measure of hope.

What is hope?

Hope is an expectation that some desirable circumstance will arise. Hope sometimes blends into something closer to ‘faith’ – where belief about a state of affairs cannot be proven. However, for most people, most of the time, ‘hope’ is a reasonable expectation.

For example, if a person makes commitments that critically depend on other people keeping their promises, that person cannot know for certain they can honour their word. Yet, if these people are known and trusted, perhaps based on past experience, then a hopeful dependence on their performance would be reasonable.

The same can be said of other commitments, such as promising to meet for a picnic on a particular day. You might make the plan in the hopeful expectation of fine weather and do so with good grounds based on a checked forecast predicting clear skies.

There are two things to be noted here. First, some aspects of hope depend (for their reasonableness) on the ethical commitments of other people (for example, to keep promises). It follows there will often be a reciprocal ethical aspect to the practice of ‘reasonable’ hoping.

Second, it’s not enough to be naively hopeful. Instead, one needs to take reasonable efforts to ensure there is some basis for relying on a hoped-for circumstance. This is especially so if the hoped-for circumstance is of critical importance to matters of grave ethical significance – such as making a promise to someone.

Given this, there may be good grounds to calibrate commitments in line with the degree to which you might reasonably hope for a particular circumstance to prevail. For example, rather than making an open commitment to meet for a particular picnic on a particular day it might be better to qualify the point by saying, “I promise to meet you if the weather is fine”.

‘It’s not enough to be naively hopeful.’

We often see the absence of this kind of forethought when it comes to the promises made by politicians during elections. They will make promises – probably based on hopeful projections about the future – only to find themselves accused of lying or having acted in bad faith when the promise is not honoured.

It’s insufficient for the politician to say they merely ‘hoped’ to be able to keep their word and that they now find their situation to be unexpectedly different. It would have been far better and far more responsible to qualify the promise in line with what might explicitly and reasonably be hoped for.

Two final comments. First, it should be understood a person often has some control over whether or not their hopes can be realised. As such, each person is responsible for those of their actions that impinge on the way they meet their obligations – we are not simply ‘bystanders’ who can idly hope for certain outcomes without lifting a finger to make them manifest.

Second, given our inability to know what the future holds, hope always plays a role in the process of making ethical commitments. The key thing is to be reasonable in what we hope for and to calibrate our commitments accordingly.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

In Review: The Festival of Dangerous Ideas 2018

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Science + Technology

We are being saturated by knowledge. How much is too much?

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

The historical struggle at the heart of Hanukkah

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

Community is hard, isolation is harder

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Big Thinker: Temple Grandin

Big Thinker: Temple Grandin

Big thinkerHealth + WellbeingRelationships

BY The Ethics Centre 4 DEC 2018

Turning a perceived disability into a new way of solving problems, Temple Grandin (1947—present) has revolutionised the meat-processing industry and changed the way the world views autism.

Temple Grandin is an autism advocate and animal scientist who works to improve animal treatment in the livestock industry. Grandin has also changed public perceptions of autism, helping educators to maximise the strengths of those with autism, rather than focusing only on deficiencies.

An animal lover and meat eater, Grandin has used her autistic trait of “thinking in pictures” to design livestock facilities and educate meat produces on how to minimise animal suffering. As a result, she says there’s been ‘light years of improvement’ in an industry where half of all cattle in the United States are handled in facilities she designed.

This isn’t enough for some animal rights activists though, who accuse her of trying to soften the image of a ‘violent’ sector.

Thinking like a cow

Temple Grandin did not talk until she was three and a half years old. She struggled to communicate throughout her childhood, and other students bullied her at school.But there was one high school teacher, Mr Carlock, who saw something special in her. He mentored the troubled girl and encouraged her to study science.

Shocked by the cruelty she saw in abattoirs, Grandin combined her love for science and animals by fixating on designs to improve animal welfare in these facilities. Grandin knew she learned better by visualising, rather than reading and hearing long strings of words. In this respect, her thinking pattern was similar to animals, who don’t ‘speak’ a language.

She observed cattle in slaughterhouses, seeing how they responded to fear, senses, smells and visual memories. When cows can see they’re about to be killed, they panic, fall and injure themselves. To combat this, Grandin invented the curved loading chutes, which block their vision of what’s ahead, keeping them calm.

This not only improves animal welfare, it saves producers the cost of cattle death, injury and bruising – which also reduces the quality of meat. Grandin has spent her career designing livestock facilities to improve the way animals are treated.

In 1997, she worked with McDonalds after activists exposed animal torture on their production plants. She helped the fast food chain clean up cruel practices and restore its public image.

In 2010, Time Magazine named her one of the 100 most influential people in the world for her work in animal welfare.

We need autistic minds

Grandin has also changed public perceptions of autism, a condition relatively unknown when she grew up. She argues people on the autism spectrum – who tend to struggle with verbal communication but think in pictures – can provide more insight in certain fields than those who think in a more conventional mathematical way.

“Visual thinking is an asset for an equipment designer. I am able to ‘see’ how all parts of a project will fit together and see potential problems.”

Grandin encourages teachers to develop the strengths of autistic children, and has devised clever ways to combat perceived flaws.Like many on the spectrum, she is oversensitive to touch. “I always hated to be hugged”, she says.

So at age 18, she built a ‘squeeze machine’ – two hinged wooden boards lined with foam rubber, which allows users to control the amount and duration of pressure applied. Therapy programs across the United States continue to utilise squeeze machines, with research showing they help relieve stress in users.

Hero or villain?

While considered a hero in the autism community, Grandin’s work divides animal welfare activists. People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals (PETA), the world’s largest animal rights group, appreciate and publish her work. Others, like biologist Marc Bekoff, hold that no animal in captivity can enjoy a pleasant life. Bekoff would rather see Grandin encourage people not to consume factory farmed animals; to him, “‘slightly better’ isn’t good enough”.

“No animal who winds up in the factory farm production line has a good or even moderately good life.” – Marc Bekoff

Grandin’s retort is that without meat eaters, farm animals would have no life at all. She argues if animals are going to die anyway, it’s important to minimise their suffering.

Does this apply to humans too?

The New York Times once asked her if she’d consider helping to make capital punishment more humane. Her response was blunt.

“I have read things about the malfunctions of the electric chair… I know how to fix it, but I will not use my knowledge to have any involvement in that. I will not cross the species barrier to help kill people. Period.”

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Big thinker

Relationships

Big Thinker: Tyson Yunkaporta

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships

There are ethical ways to live with the thrill of gambling

Explainer

Relationships, Science + Technology

Ethics Explainer: Post-Humanism

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships