Sex ed: 12 books, shows and podcasts to strengthen your sexual ethics

Sex ed: 12 books, shows and podcasts to strengthen your sexual ethics

Opinion + AnalysisSociety + Culture

BY Eleanor Gordon Smith 18 JUL 2022

Anyone who has sat through sex ed class in school or the workplace knows how difficult it is to discuss sexual ethics.

From puberty and relationships to consent and self-expression, our sexual experiences are so varied that it’s no small feat for our education to accommodate them all.

Here are 12 of my favourite books, tv shows and podcasts that thoughtfully consider the ethics around sex:

Tomorrow Sex Will Be Good Again by Katherine Angel

A critically-acclaimed analysis of female desire, consent and sexuality, spanning science, popular culture, pornography and literature.

The Right to Sex by Amia Srinivasan

A whip-smart contemporary philosophical exploration of how morality intersects with sex, particularly whether any of us can have a moral obligation to assist anothers’ sexual fulfilment.

I May Destroy You

British dark comedy-drama television series tracing the impact of sexual assault on memory, self-understanding, and relationships, and especially other sexual desires and expectations.

Disgrace by J.M. Coetzee

Multi award winning novel tracing misogyny, consent, power and indifference as they play out in one professor’s own actions and family in divided South Africa.

Love and Virtue by Diana Reid

Reid’s debut novel explores Australian college life and accompanying issues of consent, class, feminism and institutional privilege.

Sex Education

British comedy-drama series entering on the experience of adolescent sex education, thoughtful and nuanced around issues of consent, puberty, betrayal, love.

The Argonauts by Maggie Nelson

A memoir and series of ethical reflections weaving personal and detailed sexual experience together with gender and the family unit.

Masters of Sex

American drama exploring the research and relationship of William Masters and Virginia Johnson Masters and their pioneering scientific work on human sexuality.

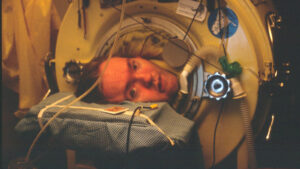

On Seeing a Sex Surrogate by Mark O’ Brien

Photo courtesy of Jessica Yu

A short personal memoir about disability and sexual expression, through the particular experience of seeing a sexual surrogate.

Fleabag

British television series exploring sex, infidelity, ageism and how casual sexual identity joins up with the rest of a person’s identity.

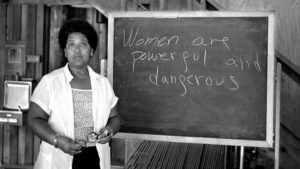

The Uses of the Erotic essay by Audre Lorde

A beautiful series of literary reflections on the power of the erotic, along with an exploration of why it is kept hidden, private, and denied, especially to particular groups.

Do the right thing from Little Bad Thing

From the podcast, Little Bad Thing about the things we wish we hadn’t done. This episode features a thoughtful conversation about the aftermath of assault, choices and healing.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

LISTEN

Health + Wellbeing, Business + Leadership, Society + Culture

Life and Shares

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture, Politics + Human Rights

‘The Zone of Interest’ and the lengths we’ll go to ignore evil

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships, Society + Culture

Of what does the machine dream? The Wire and collectivism

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Society + Culture

Does your body tell the truth? Apple Cider Vinegar and the warning cry of wellness

BY Eleanor Gordon Smith

Eleanor Gordon-Smith is a resident ethicist at The Ethics Centre and radio producer working at the intersection of ethical theory and the chaos of everyday life. Currently at Princeton University, her work has appeared in The Australian, This American Life, and in a weekly advice column for Guardian Australia. Her debut book “Stop Being Reasonable”, a collection of non-fiction stories about the ways we change our minds, was released in 2019.

Beyond consent: The ambiguity surrounding sex

Beyond consent: The ambiguity surrounding sex

Opinion + AnalysisRelationships

BY Eleanor Gordon Smith 24 JUN 2022

In April 2021, partly in response to a series of high-profile sexual assault allegations, the Commonwealth government funded a set of educational videos about sexual consent. Safe to say, they did not do the job.

There was the infamous milkshake video, in which a girl smears ice cream on her partner’s face with a devious grin; one in which a taco is distinguished from a person by the fact that a taco cannot have preferences, and one set at a swimming pool, in which the desire to go for a swim is compared to the desire (or not) to have sex. The videos were condemned in ringing terms by educators and activists – they were “problematic”, an insult to students’ intelligence, or too flippant for the gravity of the subject.

Anyone who has sat through workplace or educational training about harassment and sexual boundaries knows what a difficult feat these videos had to pull off. It’s hard to talk about sex, because sex is not one thing – even between partners, much less across the population. This makes it hard, in turn, to talk about sexual ethics — there are many more ethical lenses available than the ethics of consent.

Sex ranges from the grave and the intimate to the flippant and the casual, from the depths of taboo to the frothiest of frivolities, from power and domination to play and healing, from authentic self-expression to pantomimed degradation. It is such a chimerical experience that it’s no wonder we struggle to talk about its morality in clear and unambiguous terms. No wonder our sexual ethics education materials can fall into a kind of “uncanny valley” – videos depicting wooden interactions between characters who at once are blithely unaware of sexual norms and calmly receptive to learning them, or oddly literal exchanges that feel like they’re discussing an experience almost, but not quite, entirely unlike sex.

How can sex be so operatic and so stone quotidian, so universal and so private, so dangerous and so familiar?

Why, when our sexual experiences are so many and so varied, do we hope that an ethics of consent will be able to accommodate them all?

If we wanted a more holistic approach to sexual ethics and education, which moral frameworks would we turn to?

Time was, if you wanted an ethics of sex, the psychoanalysts were the place to turn. Freudian analyses of desire located it squarely in the individual and the underbelly of their consciousness. Desire was seldom understood as something about which one could ask the questions of justice – Is it fair? Who deserves it? – or as a candidate for political analysis. But beginning in the 20th Century, a feminist perspective rejected this picture. Feminist philosophers and legal scholars like Catherine MacKinnon and Andrea Dworkin argued that desire was both an expression of and a means of enforcing the prevailing hierarchies of power. In Mackinnon’s “Pleasure Under Patriarchy”, she quotes poet Adrienne Rich’s Dialogues: “I do not know who I was when I did those things, or whether I willed to feel what I had read about”.

Once the questions of justice had been asked around sex – once it was pointed out that power and hierarchy do not stop at the door to the home or the bedroom – there emerged uneasy questions about how sexual unfairness could create demands of sexual fairness: for instance, does anyone have a right to sex? (This question has been explored by Oxford Professor Amia Srinivisan at length). Or can a person have a moral complaint when over and over again, they are rejected for sex; unable – through the aggregation of other people’s choices – to access an experience that everyone else says is one of life’s central joys?

Sexual desire has long discriminated along racial and disability lines – as Srinivasan notes, Asian men on dating apps or disabled people are frequently told to their faces that they are instantly rejected as prospective sexual partners because I would never sleep with someone like you. How can we make sense of the utter rigidity of the rule that nobody should have sex with anyone they don’t want to – alongside the possibility that those choices en masse enact a prejudice that each of us might individually deny? One more mystery for the ethics of sex; for the challenge of bringing justice to something as fraught as desire. As Srinivasan so memorably writes: “There is nothing else so riven with politics and yet so inviolably personal.”

In this morass of ethical grey, the concept of consent seemed to promise some black-and-white. We might not know the full list of our sexual rights, but an ethics of consent at least clearly names the sexual wrongs. The centrality of consent to sexual ethics is in fact a relatively recent development; the concept gained traction in the 1980s, at roughly the same time as the autonomous individual became the main character of political analysis. It was not long before then that “informed consent” was still a foreign notion in healthcare ethics, and that rape of a sex worker was often understood not as a violation of consent, but as theft of services.

Perhaps consent education reaches for simple metaphors like milkshakes, tacos, or cups of tea because an ethics of consent is simple – so simple we can say it in the familiar truism: “No means no”. But the trouble with centering consent in our sexual ethics is that it risks confusing ‘not-capital-B-Bad’ with ‘good’. Plenty of consensual sex is also cruel, harmful, selfish, painful, alienating, or subordinating.

Consensual sex is not necessarily ethical, nor even necessarily good. By treating non-consensual sex as the primary case about which to do sexual ethics – the jumping off point for our analysis and education – we risk introducing young people to sexual morality primarily through the category of wrong and how to avoid it, instead of through the lens of sexual joy and how to share it. Sex can be a way to connect with one another, to know, to be vulnerable, to give, to reveal, to trust – the intelligibility of aspiring to sex like this can be lost when the highest aspiration of our sexual ethics is “getting consent”.

By treating non-consensual sex as the primary case about which to do sexual ethics – the jumping off point for our analysis and education – we risk introducing young people to sexual morality primarily through the category of wrong and how to avoid it, instead of through the lens of sexual joy and how to share it.

One of the central tasks of an ethical life is to distinguish between the realm of duty – what can be demanded of us, and the realm of benevolence, what we can freely give, and to realise that the person who thinks only about their duties is in some ways a moral miser. An ethics of sex which prioritises duty by emphasising consent and permission can accidentally obscure the possibility of an ethics of benevolence – one which would not stop after asking what we owe to one another, but would carry on, asking how we might help them flourish.

To live an ethical life is more than avoiding wrong – how strange it would be to forget that in our most vivid encounters with others.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Climate + Environment

Blindness and seeing

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

The ethics of friendships: Are our values reflected in the people we spend time with?

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

In defence of platonic romance

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

How can you love someone you don’t know? ‘Swarm’ and the price of obsession

BY Eleanor Gordon Smith

Eleanor Gordon-Smith is a resident ethicist at The Ethics Centre and radio producer working at the intersection of ethical theory and the chaos of everyday life. Currently at Princeton University, her work has appeared in The Australian, This American Life, and in a weekly advice column for Guardian Australia. Her debut book “Stop Being Reasonable”, a collection of non-fiction stories about the ways we change our minds, was released in 2019.

Ethics Explainer: Testimonial Injustice

Ethics Explainer: Testimonial Injustice

Opinion + AnalysisPolitics + Human Rights

BY The Ethics Centre Eleanor Gordon Smith 22 SEP 2020

Telling people things – or giving ‘testimony’ – is one of our quickest, oldest, and most natural ways of adding to human stores of knowledge.

Philosophers have spent thousands of years wondering when, and why, certain beliefs count as knowledge – and when certain beliefs count as justified. Many agree that when we are told something by someone reliable, trustworthy, and in possession of the facts, their testimony can be enough to justify a belief in what they say.

I can tell you that it will rain later, you can tell me which way the train station is, we can both go to a lecture by an expert and walk away knowing more.

But we can’t accept all the information we hear from other people. Not all testimony can ground knowledge – some of it is lies, errors or opinion. That’s why credibility is important to the process of learning by being told.

The enlightenment philosopher David Hume argued that we shouldn’t set our standing levels of credibility too high: he thought “testimonial beliefs” were only justified when we had back-up justification from other sources like our own eyes, readings, and observations.

Immanuel Kant, by contrast, thought that we had a “presumptive duty” to believe what our fellow humans told us, since believing them was a mark of respect.

Regardless of the debate about how much credibility we should give people, there’s no denying that how much credibility we do give plays a big role in what we can learn from each other, and whether we learn anything at all.

Sometimes we allocate credibility in ways that are unfair, unreasonable or outright harmful. Beginning in the 20th Century, Black and female philosophers started pointing out that women, people of colour, people who spoke with an accent, and people who bore visible markers of poverty were disbelieved at far higher rates than the general population.

Because of existing prejudices against these people, some ethicists posit, they are being systematically disbelieved when they speak about things they, in fact, are reliable experts about. This is what philosophers term “a credibility deficit”. People could experience a credibility deficit when they speak about elements of their own experience, like what it was like to be a woman in domestic servitude.

It could also include elements of the world around them – such as the denial of black people’s reports of violence by white men.

Credibility deficits are not just a matter of knowledge but a matter of justice: if we are not believed when we tell other people true things, we can be shut out of important social processes and ways of being recognized by other people. One of the most important ways that credibility deficits play out is in court, or in other reports to do with crimes and legal proceedings.

After abolition in the United States but before the civil rights movement, black peoples’ testimony was not recognised as a source of legal information in courts. That legacy has long undermined the way that black people’s testimony is viewed in courts, even today.

Philosopher Miranda Fricker uses a scene from To Kill A Mockingbird to highlight the way Tom’s race, when combined with his being in a white courtroom affects his Tom credibility. Though he is in fact telling the truth, and though there are no obvious reasons to disbelieve him, the white jurors in the American South are so trained by prejudice that they regard his race itself as a reason to disbelieve him. It is not the facts of the story itself that mean jurors do not believe it, but facts about who is telling it.

Clip: Tom Robinson’s cross-examination from To Kill A Mockingbird.

This was a common and tragic way that credibility deficits played out in the real world: there is a long history of white women being believed over black men even when they made false and damaging claims.

The tradition of “testimonial injustice” in philosophy argues that credibility misallocation is more than a mistake. It is an injustice because we have a moral duty to see other people as ‘full’ people and to treat them with respect, but discounting people’s word because of prejudice is a way of denying them that respect.

In some ways, to refuse to believe someone without defensible reasons is to refuse to recognise them as a person.

Philosophers like Miranda Fricker, Jose Medina, Dick Moran, and a long tradition of black feminist epistemology including Charles Mills and bell hooks have explored the ways that being a free and equal citizen requires being believed as one. There are wide-ranging debates among these thinkers over many areas inside testimonial injustice, including whether and why being believed is foundational to being seen as a person, what kinds of credibility we could ‘owe’ one another, and whether people besides the disbelieved party are wronged by a faulty allocation of credibility.

One important question is whether it could be wrong and if so to whom, to give out too much credibility instead of too little. If it’s unfair to afford someone too little credibility, what should we say of affording too much? Are they wrong? If so, why? And, who is wronged by giving someone more credibility than they deserve?

A case study that might demonstrate this question is the familiar setting of the classroom. A male teacher-in-training with six months experience might be regarded in the classroom as more authoritative than a female teacher with many years’ more experience. This need not mean that the students disbelieve the female teacher. They could simply believe the male teacher more readily, with fewer questions, and with more of a sense that he is credible and has gravitas in the learning environment.

They could simply give him more credibility than he deserves. Who is wronged by this, if the female teacher is still believed when she speaks? Are the students wronging themselves? Are they accidentally wronging the male teacher, even though he benefits from the arrangement? These are important open questions that ethicists are still debating.

Another question is what kind of credibility we have to give to others in order to do right by them. Hume knew that we could not believe everything we hear. How much must we believe, in order to avoid this distinctive form of injustice?

Despite these unresolved matters, testimonial injustice is an important ethical phenomenon to be aware of as we move through the world trying to be responsible speakers and hearers. It’s important to living ethically that we keep prejudice and it affects out of our beliefs as well as out of our acts.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights

Democracy is still the least-worst option we have

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

CoronaVirus reveals our sinophobic underbelly

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights

Australia is no longer a human rights leader

Opinion + Analysis, READ

Politics + Human Rights

How to find moral clarity in Gaza

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

BY Eleanor Gordon Smith

Eleanor Gordon-Smith is a resident ethicist at The Ethics Centre and radio producer working at the intersection of ethical theory and the chaos of everyday life. Currently at Princeton University, her work has appeared in The Australian, This American Life, and in a weekly advice column for Guardian Australia. Her debut book “Stop Being Reasonable”, a collection of non-fiction stories about the ways we change our minds, was released in 2019.

What's the use in trying?

What’s the use in trying?

Opinion + AnalysisPolitics + Human RightsRelationships

BY Eleanor Gordon Smith The Ethics Centre 24 AUG 2020

In early 2020 I sat in a friend’s house on the coast of New South Wales listening to smoke alarms go off in canon, triggered by the air itself, thick with smoke from the active fronts of the worst bushfire season in living memory.

The roads were lined with scorched animals and the climate crisis seemed as inevitable as it did cataclysmic. It was unthinkable then that this moment of apparently superlative awfulness would, in a matter of months, recede to just one more entry in a year-long list of suffering, death, and massive-scale crisis.

The lucky of us stayed inside afraid for months. The unlucky died, or lost loved ones and could not go to their funerals. There was widespread and systematic police violence against black people and against the people who protested it. USD $3.6 trillion was wiped off the stock market in one week.

The first six months of 2020 presented an unusually literal illustration of an old ethical question: why bother when the conclusion feels foregone?

What many of us felt about the climate in January was a well-known phenomenon: the fatigue of feeling useless when we felt we could not rely on the powerful to make changes or on other people to do their part. This feeling was quickly matched by parallels in resistance to systemic racism, in fighting an economic downturn and even in pandemic compliance.

Early on in the COVID-19 outbreak, data modelling revealed that social distancing would only work if 8 out of 10 of us followed the rules. If only 70% of us stood six feet apart, washed our hands, and stayed inside for weeks on end, it would be as though none of us had. To the misanthropist who felt that 30% of people would surely disregard the rules, a motivational gap loomed: why do what I can to help, when I’m not confident it will.

Even to the most resiliently motivated, parts of 2020 posed this problem. Hundred-thousand strong protests in the United States were not enough to prevent the deaths of more unarmed black people, nor to prevent protestors themselves from being pepper-sprayed at close range.

The indefatigability of the protests seemed met by the indefatigability of the problem. For many people it became impossible to feel calm or ordered anywhere as long as case numbers rose. So it seemed foregone that our homes would not feel calm or ordered either, and the motivation to improve them frayed in proportion to the dishes in the sink.

The philosopher and psychologist William James knew that certain beliefs can be self-validating; that confidence in outcomes, however, we come by it, can make itself well placed. The sailors who think they can pull the heavy rope are more likely to summon the gusto and collective coordination required to make it the case that they can. This first half of 2020 was a vivid illustration of the photonegative; the fact that uncertainty about outcomes can be enough to puncture our drive to pursue them.

So what is there to be done? Few of us believe that this pessimism or uncertainty in fact means that it is not worth protesting, or washing our hands, or doing the dishes. We still rationally endorse that we ought to do these things. But it becomes a wrench, an act of shepherding ourselves, parent-like, and it wears us down. It leads us to misanthropy.

An answer lies in looking more closely at one facet of what 2020 has cost us. We lost the most unthinking parts of our lives; the well-worn routine of the drive home or the setup at the gym, the clockwork Wednesday night choir, the disappearance into a team practicing a physical skill.

These were moments where what we did was not to achieve, or to think, but to be in a process. It was immaterial to us whether we achieved victory or even improvement, since our commitment to doing them was not dependent on whether we did. What we wanted was to be absorbed, to be a creature who acts.

We are, unavoidably, creatures who act. But as philosopher Mark Schroeder has noted, there is an asymmetry between our options in thought and our options in action. We have three options about what to think: we can believe what is on offer, reject it, or withhold judgement. But in action we have only two options; act or do not. There is no way to be in the world that avoids this two-prong choice.

When we realize this, we can shift our focus in a way that avoids futility fatigue. Our moral duty to act – and so too, our motivation – need not be entirely derived from what will happen once we do. It may be that what we owe each other is action itself, and effort itself.

In turn, this can release us from some pressure that comes with knowing that our goals will be difficult to achieve and fragile once we get them. We can simply aim at the action itself. We can find in resistance, in participation, and in care, a goal which is not about the altering of the world but about the observation of the act itself.

In this state, our uncertainty is no longer a threat to our motivation. With this as our focus and our source of energy, we may find that we are, in the end, more effective at altering the world.

You can contact The Ethics Centre about any of the issues discussed in this article. We offer free counselling for individuals via Ethi-call; professional fee-for-service consulting, leadership and development services; and as a non-profit charity we rely heavily on donations to continue our work, which can be made via our website. Thank you.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

Inside The Mind Of FODI Festival Director Danielle Harvey

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

How to respectfully disagree

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Naturalistic Fallacy

Reports

Politics + Human Rights

The Cloven Giant: Reclaiming Intrinsic Dignity

BY Eleanor Gordon Smith

Eleanor Gordon-Smith is a resident ethicist at The Ethics Centre and radio producer working at the intersection of ethical theory and the chaos of everyday life. Currently at Princeton University, her work has appeared in The Australian, This American Life, and in a weekly advice column for Guardian Australia. Her debut book “Stop Being Reasonable”, a collection of non-fiction stories about the ways we change our minds, was released in 2019.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Whose home, and who’s home?

Whose home, and who’s home?

Opinion + AnalysisPolitics + Human RightsRelationships

BY Eleanor Gordon Smith The Ethics Centre 17 AUG 2020

Australian citizens who live overseas and want to return to Australia, with some exceptions, now have to pay for their mandatory two-week hotel quarantine.

This new rule applies for those returning to New South Wales or Queensland. It means that a single adult returning home must have AUD $3000 to pay for their stay. Last week New Zealand announced a similar policy: citizens returning home to stay less than 90 days will be charged for their quarantine.

Announcing the policy, NSW Premier Gladys Berijiklian said “Australian residents have been given plenty of time to return home, and we feel it is only fair that they cover some of the costs of their hotel accommodation”.

The locution of having “been given” time to return home sounded curious to many of us who reside overseas. We were unaware that living elsewhere had been a matter of taking.

In the comments sections of news articles about the announcement, the Premier’s sentiment was echoed by other Australians. A recurring theme appeared: overseas Australians who returned home now are being selfish to expect taxpayer help

What could fairness require, in a pandemic? It is not fair that some people will get COVID and others will not. It is not fair that some will die while others survive. These are circumstances where a question about fairness is simply not askable; there is only tragedy, which does not have a possible equitable distribution.

One way to be unfair in a pandemic might be to expose other people to risk. People arriving from overseas certainly do that, and it is crucial to Australia’s efforts to contain the coronavirus that it curbs the risk from international travellers. Like many other countries, Australia was within its rights to close its borders early to international travellers in recognition of this risk.

The very concept of citizenship, however, prohibits closing borders entirely. No matter where citizens ordinarily live, their government has a duty to allow them to cross the border of their home. This is what it means to be a citizen.

There is a problem of incommensurability here. How does the need to mitigate a biothreat weigh against the standing rights of citizens to cross a border? One is a value of rights and obligations; the other is a value of consequences and threat reduction. Neither of these values presents itself in a standardised unit to be compared against the other.

The question is not quite “how do we make a good decision?” but “which kind of good should we be interested in?”. This is a fairly common problem.

Not all of the things we want governments to provide can be coherently measured against each other, so when they come into conflict, it’s not clear how to even begin making the trade. Privacy against safety, health against freedom, service provision against non-interference.

The Government appears to have chosen fairness as the value to adjudicate between the two. The Premier described the policy as “only fair”, since “Aussies overseas have had three or four months to figure out what they want to do”. Prime Minister Scott Morrison echoed this, saying overseas Australians “obviously delayed [their] decision”, and Winston Peters of the New Zealand First Party said that asking taxpayers to pay for fellow citizens’ quarantine was “grossly unfair”.

There are two features of the decision that challenge the terms of fairness here. One is that it seems only to apply to Australians overseas. We would not, for instance, describe it as “only fair” to deny Medicare coverage to an Australian at home who contracted COVID-19 after breaking quarantine rules, even though there is an argument that this is ‘only fair’. Like the quarantine fee, it would mean that those who had ‘plenty of time’ to follow the rules did not impose a burden on the taxpayer when an emergency befell them.

The second is that it is not clear that fairness is the value we should default to in the midst of a global pandemic. In an article for Guardian New Zealand, Elle Hunt suggested that these policies are a failure of empathy. “Discriminating against all but the most wealthy members of the diaspora is a rare failure of not just compassion but imagination – to reach a more equal solution, and to imagine the painful personal circumstances in which it might be warranted.”

Empathy asks different things of a government than fairness. It asks for mercy and the maximum provision of services to those who are suffering. It asks for an imaginative capaciousness about what life is like for citizens whose jobs, families, friends and visas would have been in peril if they had returned earlier. It asks for magnanimity, forgiveness, and generosity.

Empathy may not be a viable long term guiding principle for a political party. But in a pandemic, we may find that the alternative language of fairness and moralising either loses its footing entirely or forces us to absurd conclusions.

“Only fair” was how the Premier described the policy, but we have more values than only fairness. A global emergency may be the time to use some.

You can contact The Ethics Centre about any of the issues discussed in this article. We offer free counselling for individuals via Ethi-call; professional fee-for-service consulting, leadership and development services; and as a non-profit charity we rely heavily on donations to continue our work, which can be made via our website. Thank you.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

The philosophy of Virginia Woolf

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Ageing well is the elephant in the room when it comes to aged care

Big thinker

Politics + Human Rights

Big Thinker: Ayaan Hirsi Ali

Opinion + Analysis

Climate + Environment, Politics + Human Rights