Bring back the anti-hero: The strange case of depiction and endorsement

Bring back the anti-hero: The strange case of depiction and endorsement

Opinion + AnalysisRelationshipsSociety + Culture

BY Joseph Earp 3 MAR 2023

The undead are everywhere. It’s not just that our culture is obsessed with zombies, from The Walking Dead to The Last Of Us. It’s that our cultural discussions are zombies themselves – they just won’t die.

We go over the same old arguments time and time again, to no seeming progression or end. Just take the cultural discussions around depiction and endorsement where the lines have been drawn in the sand.

For those on one side of the line – the instigators of this particular debate – artists who depict monstrous acts are seen to be agreeing with these acts. The mere depiction of violence, for instance, is seen as a kind of thumbs up to that violence, tacitly encouraging it.

On this view, artists are moral arbiters, and the images and stories that they put out into the world have a significant, behaviour-altering effect. Depicting criminals means “normalising” criminals, which means that more viewers will believe that criminal acts are acceptable, and, theoretically, start doing them.

This view has a historical precedent. Art has long been political, used by states and religious groups in order to provide a form of moral instruction – consider devotional Christian paintings, which are designed to exhort viewers to better behaviour.

Certainly, there are still artists and artworks with a pointedly ethical and political mode of instruction. From government PSAs that borrow storytelling techniques that artists have used for years, to the glut of Christian-funded films like God Is Real, art objects have been designed as transmission devices for a particular point of ethical view. Even Captain Marvel, another in a seemingly unending glut of superhero movies, was created in partnership with the airforce, and depicts the military in a childishly positive light.

But acting as though all art has this moral framework – that everything is a form of fable, with a clear ethical message – is a mistake. Moreover, it elevates a discussion about art beyond what we usually think of as aesthetic principles, and into political ones. It’s not just that the instigators who view all art as essentially and simply instructional worry we’re getting worse art. It’s that they worry we’re getting more dangerous art.

In just the last 12 months, Martin Scorsese has been condemned at least three times in some circles of the internet for glorifying depravity with his films about criminal underbellies.

But the argument really saw its time in a sun that won’t set with the release of the bottleneck episode of The Last of Us, a much heralded – and deeply contentious – piece of television.

Fungal Zombies And Queer Representation

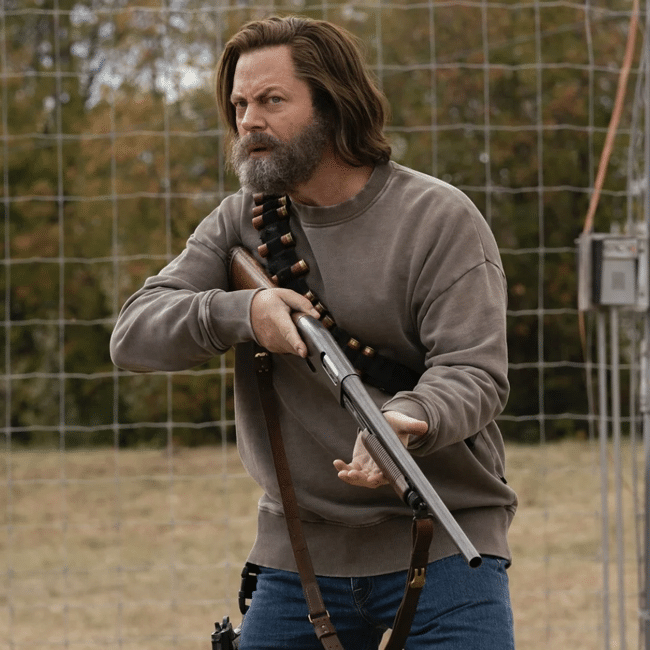

In the episode, Parks and Recreation’s Nick Offerman and The White Lotus’ Murray Bartlett embark upon a queer romance while the world ends around them. Though highlighted for its sensitivity in some corners of the discourse, the episode received significant pushback.

For writer Merryana Salem of Junkee, the episode was an example of “pinkwashing”, due to the fact that the characters value “individual liberty over community good.” As in – they try to survive during an apocalypse. Salem criticises the show for depicting queer characters looting and pillaging, rather than sharing resources. By aligning queer representation with selfish behaviour, Salem appears to be arguing that the show will platform and perhaps normalise libertarian values of the self as important above all others.

“Far from framing this attitude as negative, a song plays cheerily over Bill hoarding, looting resources, and setting up security systems that would prevent anyone in the immediate area from even using the electricity in the local plant”, Salem writes.

The argument here is simple. One act is shown onscreen instead of another. That is a choice. The choice, combined with the aesthetics around it – cheery music – means that this choice is designed to impress upon the audience the admirable nature of the character, even as he does less than admirable things.

What such an argument precludes, however, is the complexity inherent in the episode. The Last of Us’ showrunner, Craig Mazin, may not be pointing at good and bad as directly as his critics assume. Bill is a man trying to carve out love and life under impossible circumstances. In an ideal world, he wouldn’t be hoarding resources. In an ideal world, he would be living quietly, in a community. He doesn’t want to make do in the middle of a zombie outbreak.

The beauty of the episode, then, is the way it makes a case for the power of an easy love formed under uneasy circumstances. Bill’s flawed because he’s been made that way by an outbreak of, ya know, fungus zombies. And yet still he finds some crooked form of redemption in the arms of another.

That’s what is missing from so many of these debates about depiction versus endorsement – nuance.

Good storytellers don’t depict flatly. They depict with complexity. With differing shades of light and dark. And so their art should be analysed on those merits, with criticism that is itself complex.

But more than that, we need to ask ourselves, finally, whether depicting reprehensible acts onscreen really has the effect that these critics assume it does.

The Return Of The Big Bad

Take some of the most reprehensible people on television. Walter White of Breaking Bad. Tony Soprano of The Sopranos. Even Don Draper of Mad Men. These men, who washed over our screens during the start of the Golden Age of Television, do bad things.

More than that, they get rewarded for them. Tony is lavished with success of all forms – money, power, opportunity. Walter finds, through drug-dealing, a new level of self-confidence and authority. Don never gets a traditional comeuppance, unless you take the constant unease in his soul as a form of comeuppance.

These characters are explicitly rewarded – in some ways – for their immorality. They get away with it. Even Tony, whose fate is hinted at but never explicitly shown, gets a moment of peace before he goes. Don’s sitting there with a big old grin on his face the last time we see him. And sure, Walter gets snuffed out, but on his own vicious terms.

And so what? Are any of the creators behind these anti-heroes really suggesting that we should turn to crime or adultery? If they are, then they are not artists – they are salesmen.

Art is better when we treat it as nuanced, complex depictions that leave it to us to do the work of untangling.

Indeed, through immorality, these characters suggest that the only thing worse than these flawed and difficult characters is the world around them – the world that rewards them. It’s not Don that’s the isolated problem, cutting a swathe of heartbreak and cashing a big old cheque. It’s that the structure around him is misogynistic and capitalistic. He is the perfect product of his era. And the depiction of his moral crimes isn’t meant to encourage us to applaud those crimes. It’s meant – at least on one interpretation – to make us question the whole system that props us up.

It’s a mistake to hanker for art that only operates in one moral mode; that punishes the wicked, and celebrates the innocent. Not even fairy tales are that simplistic. We live in an era in which even our zombie TV shows are filled with nuance and complexity. Let’s engage in discourse worthy of that.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

What’s the use in trying?

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Ask me tell me: Why women think it’s ok to lie about contraception

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Why learning to be a good friend matters

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

In two minds: Why we need to embrace the good and bad in everything

BY Joseph Earp

Joseph Earp is a poet, journalist and philosophy student. He is currently undertaking his PhD at the University of Sydney, studying the work of David Hume.

Where are the victims? The ethics of true crime

Where are the victims? The ethics of true crime

Opinion + AnalysisRelationshipsSociety + Culture

BY Joseph Earp 9 FEB 2023

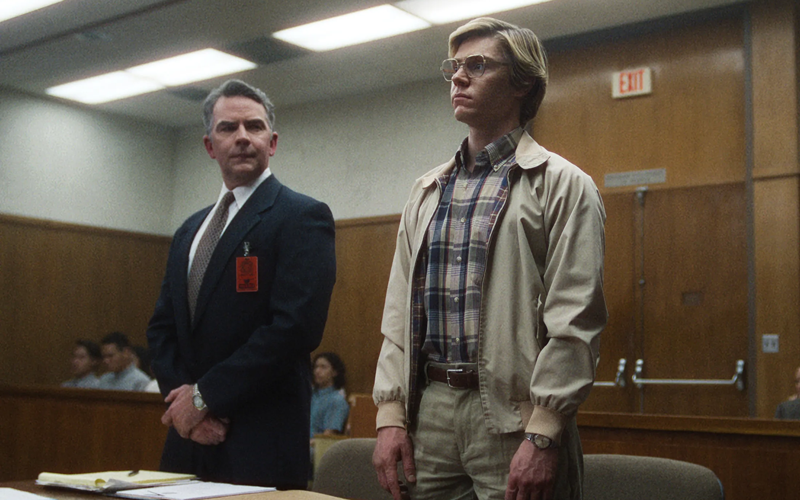

In January 2023, actor Evan Peters took to the stage to accept a Golden Globe for his performance as Jeffrey Dahmer in the surprise streaming success Monster – The Jeffrey Dahmer Story.

It was a moment of odd contrast. There was Peters, dressed in a Dior suit, surrounded by opulence of the highest order and luxuriating in the most comfort and security imaginable — rich, safe, protected — accepting an award for his portrayal of a serial killer. More than that, the families of Dahmer’s victims were nowhere to be seen. As the actor collected the gong, those whose lives had been forever shaped by the crimes of a serial killer — second-order victims, whose narratives had been used for art — were off-screen.

It was a moment that crystalised the strangeness of our modern obsession with true crime, an obsession that is taking over the entertainment industry, and swamping podcast feeds and our small screens. In swathes of the Western World, we are safer than ever before from the threat of another Dahmer — and yet, in our post-Making A Murderer world, ripped from the headlines stories of violence and immorality are everywhere, even as such experiences are becoming, for most of us, as alien as stories set on Mars.

And such stories have real-life victims who are still with us; still alive, and in many cases, still grieving. These people who deserve emotional security are being ignored and overwritten by Hollywood.

Why then can’t we get enough of Ed Gein, and Ted Bundy, and the mountain of murderers that fill up our screens? What are the ethics of engaging with these traumas casually, over dinner, or on our way to work? And what can we do to make this immensely popular sub-genre genuinely ethical?

Why Are We Getting Off On Murder?

It would be wrong to suggest that our current moment of true crime consumption is a total deviation from past trends. Stories of horror and amoral behaviour have been with us since at even earlier than the time of the Brothers Grimm — most oral storytelling revolved around bloodshed, deviants, and murder.

It would also be wrong to suggest that true crime is an empty or useless art form. Art is therapeutic because it allows us to explore and imagine heinous violence and immorality from the safety of our homes. It’s a tool for processing collective fear; collective horror. It’s a way for us to explore how we feel about our own moral systems, by examining the lives and actions of those who deviate from those systems.

However, it’s the “based on a true story” tag that makes true crime distinct. It is hard to imagine that Monster would have the same impact on the mass culture if it was a total fiction. The “true” in “true crime” is part of the sell.

Engaging in the world of true crime means engaging in a world where serial killers lurk around every corner. For those of us living in cities in the Western World, that is far from true. Serial killers were always the aberration to the rule. Now, they’re positively alien — in the U.S., serial crime makes up less than one percent of all crimes recorded. For those of us with class privilege, our deaths will come, most likely, from heart disease, not a sociopath in oversized glasses who will later mummify our heads.

Why true crime has blossomed in the context of these cultural shifts is hard to say. Could it be a result of the passivity baked into entertainment these days? So much of us binge shows to tune off, switch out, and relax on the couch. True crime is excitingly different. Podcasts like My Favourite Murder, or smash hits like Making A Murderer gives audiences an opportunity for further engagement that extends after the credits roll. You can read Wikipedia pages. You can listen to more podcasts; watch spin offs; read testimonies. And that means you can become a sort of detective of your own, sniffing out leads, becoming not just a watcher, but a researcher.

Blood On Whose Hands?

The cultural context for our obsession with true crime adds a string of ethical dilemmas to consuming it. For a start, our obsession is coming a time where we are more able than ever to educate ourselves on the crooked and fundamentally broken nature of the police force. Most true crime is ‘copaganda’, saturating the populace with the myth that most police officers are inventive, savvy artists stringing together clues, rather than overfunded, inadequate mental health professionals at best, and the violent arm of the state at worst.

True crime also plays uncomfortably into pre-existing racial divides. In most true crime shows produced in the United States, Australia and the UK, the victims come from ethnic backgrounds that are not white. The cops, by contrast, are white. The looming threat of the white savior narrative is thus unavoidable. Just as problematically, race is an unspoken presence in most true crime, rarely acknowledged, and glossed over by artists in favour of the flashier, gorier elements of these stories.

Finally, real-life crime means real-life victims. Dahmer’s victims have children; friends. These crimes leave intergenerational traces – there is a legacy of pain that drips down bloodlines after a life is cruelly and inhumanely snuffed out. Not only have these second-order victims lost a loved one, they’ve seen that loved one turned into newspaper headlines and bit players in a swathe of miniseries and podcasts.

Creators of true crime art have a responsibility to these families. The reason for this responsibility is two-fold. Firstly, these stories would, devastatingly, not have happened were it not for the victims. In the worst, most painful way, Dahmer was who he was because of the people he killed. His story is their story, and any Hollywood creative who tells that story and makes a dime is profiting off the pain of victims. Ryan Murphy, Monster’s creator, has a net worth of $150 million. Evan Peters has a net worth of $4 million. Both have enjoyed significant financial success from Monster that the second-order victims of Dahmer have not.

Creators of true crime art have a responsibility to these families… The worst moment of these people’s lives are being turned into entertainment.

The pain of those whose lives were affected by Dahmer provides the second reason for the responsibility of true crime artists — these victims and their families are just that. Victims. The worst moment of these people’s lives are being turned into entertainment. All the award shows that Peters and Murphy get to swan about at seem actively exploitative, given the human suffering that they took from real-life, and fashioned for the screen.

The way to resolve this responsibility is proper financial remuneration. These families deserve to be compensated for their stories, and for their pain. Moreover, such an obligation extends beyond just those involved with Monster, and implicate all true art creators, no matter the medium. How often have you listened to a true crime podcast, in which a grisly murder is being detailed, only to have your experience interrupted by a jocular advert for mattresses and at-home meal kits? These moments sit the grisly murder next to the adverts that make the creators of such content wealthy – throwing into focus that the true crime industry is just that — an industry.

Sure, in a capitalist system, all art has to be commercially minded to some extent – art is expensive to make, and artists deserve to be compensated. But the integration of advertising into true crime feels particularly craven. The money must be shared. Those who deserve to be paid should be paid.

None of this is an argument for shutting down true crime art, or censoring it or banning it in any way. True crime, for its flaws, serves a purpose. It can make us think about class; about context; about law. But to be truly ethical, true crime must shift its relation to the victims who are involved in these stories. Otherwise, there’s blood on the hands of more than just the murderers.

For more insights into our consumption of true crime, tune into the FODI22 discussion, The Crime Paradox

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships

How the Canva crew learned to love feedback

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Our desire for reality: What OnlyFans says about sexual fantasy

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Germaine Greer is wrong about trans women and she’s fuelling the patriarchy

Big thinker

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Big Thinker: Temple Grandin

BY Joseph Earp

Joseph Earp is a poet, journalist and philosophy student. He is currently undertaking his PhD at the University of Sydney, studying the work of David Hume.

What money and power makes you do: The craven morality of The White Lotus

What money and power makes you do: The craven morality of The White Lotus

Opinion + AnalysisRelationshipsSociety + Culture

BY Joseph Earp 22 DEC 2022

One surprising fact about Mike White, the creator, writer and director of HBO’s The White Lotus, is that he’s obsessed with and starred in a season of Survivor, the brutal reality TV show that pits strangers against each other in a complex game of wits and skill.

Of course White’s a Survivor junkie. The two seasons of The White Lotus – a soap opera-cum-murder mystery about a bunch of depraved rich people who exploit the surplus of expendable workers who man the titular hotel they stay at – are united by their fixation on the ways human beings outwit and outgame each other.

The White Lotus takes it as a given that human beings want things from each other, and use their (varying levels of) intelligence and power to get those things. There’s not an innocent in either season of the show, and their moral failings range from the petty and pathetic to the grand and soul-blemishing. Shane (Jack Lacy) kicks off the first season by whining and berating the hotel staff in order to get what he feels owed. Armond (Murray Bartlett), the long-suffering hotel manager, ignores one of his staff members when she goes into labour. They’re a den of thieves and miscreants, whose naked wants trump any sense of obligation to one another.

Even Tanya (Jennifer Coolidge), the only character who spans both instalments, is a hero only by virtue of being less openly murderous. Her slow realisation in the show’s second season that she is sat at the direct centre of a conspiracy motivated by greed is tragic, sure. But by the time we see her mutter her instantly iconic line about the gays who are trying to murder her, we’ve already watched her dangle her considerable wealth in front of Belinda (Natasha Rothwell) and then withdraw it, dishonestly, the moment she becomes the object of someone’s lustful affections.

These characters operate in what philosopher John Locke refers to as “the state of nature.” Locke, one of the founders of modern liberalism, believed that left to their own devices, without society, human beings live lives that are “nasty, brutish and short.” There is no sense of community, or solidarity, in the state of nature. All people want is what they want, and they live in a continuous state of never denying their desires.

So it goes in The White Lotus. The characters are nominally part of a culture – the kind of society that Locke hoped would block bad behaviour. After all, for Locke, mutual beneficence is the glue that holds us together – you scratch my back, I’ll scratch yours. You refrain from killing me, so I won’t kill you either.

But Locke’s hope that the stratas and rules inherent in a society would keep its citizens ethical is blown apart by The White Lotus. Alliances form in the world of the show, sure. But these are temporary, fleeting, purely opportunistic. Belinda and Tanya don’t like each other. They need each other. Ethan (Will Sharpe) and Harper (Aubrey Plaza) might have a connection, but it’s not strong enough to hold together in the face of changing fortunes and friendships.

Importantly, so it goes across class divides. Though the show has been touted as part of a wave of modern works of art that take aim at the rich – from Parasite to The Menu – the show does not reserve its ire merely for the upper class. What sets The White Lotus apart from much “we are the 99%” cinema and television, is the way it examines the pressure that capital places on all citizens, the haves and the have nots alike.

Bitch Better Have My Money

Thorstein Veblen, the Austrian sociologist, is best known for his book The Theory Of The Leisure Class. Veblen examines the hallmarks of the elite, and finds one in common across a multitude of cultures. Simply put, Veblen says, rich people like excess. They like to spend money on things that they don’t have to spend money on.

The characters of The White Lotus are driven by this need for excess.

They want more than they could ever need. And because of this want, their lives are transformed into a series of opportunities. Wealth and power become means to garner more wealth and power.

The Di Grasso family of the second season are the perfect example of this. Some wealthy families have a “crest”, a pictorial representation of their values. The Di Grasso family’s crest would be a den of rats, ignoring their stockpile of food, and instead choosing to chew each other’s tails.

This is a family that, over generations, has learned that the world is nothing more than a series of goals, which lead to nothing but more goals. Bert (F. Murray Abraham), the family’s patriarch, has created a miniature culture that revolves around himself, in which sex is an opportunity for manipulation, wealth is an opportunity for manipulation, and love is an opportunity for manipulation.

And his brood, desperate to emulate him, and attract his affection – if only to get ahead themselves – have followed in his lead, even if they don’t realise it. For this family, nothing and no-one ever sits as they lay – nothing is discrete, or for itself. Bert might be viewed by the other characters as a mostly impotent, harmless old man, a wannabe peacemaker who has lost touch. But he is as single-minded as ever, even in his old age, and he spends the second season analysing the weakness of others, and then using those weaknesses for his own gain.

This opportunistic streak extends to the entire solar system of vapid and cruel characters in the second season. Tanya is exploited for her deep loneliness, and her own desire to exploit others stops her from realising the danger she’s in until too late. Lucia and Mia, the strongest-hearted characters of the second season, all things told, come into themselves as creatures who know how to get what they want, and what they have to do to get those things. No honour among thieves, and no values but the shifting goalpost of immorality, which reduces the world to a series of people to fuck over, and be fucked over by.

And for what? The striking thing about The White Lotus is how little this all means. All that suffering, all that exploitation, and the only prize at the end is a consolation prize. It’s not for nothing that each season’s murder turns out to be a whimper, rather than a bang. In the first season, Armond dies after a feces-based prank goes pathetically wrong, running himself into a blade. And in the second season, Tanya manages to (somewhat) extricate herself from a conspiracy to murder her, gun blazing, only to die thanks to an ungainly fall.

Checks out. If what marks the upper class is their fixation on the pointless, the too-much, then of course their fates are pointless too. Even those who win don’t win much. And those who lose – well, they lose hard, falling backwards into the den of conniving players that they have tried and failed to connive.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Big thinker

Relationships

Big Thinker: Jeremy Bentham

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture

FODI returns: Why we need a sanctuary to explore dangerous ideas

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

What’s the use in trying?

Big thinker

Relationships

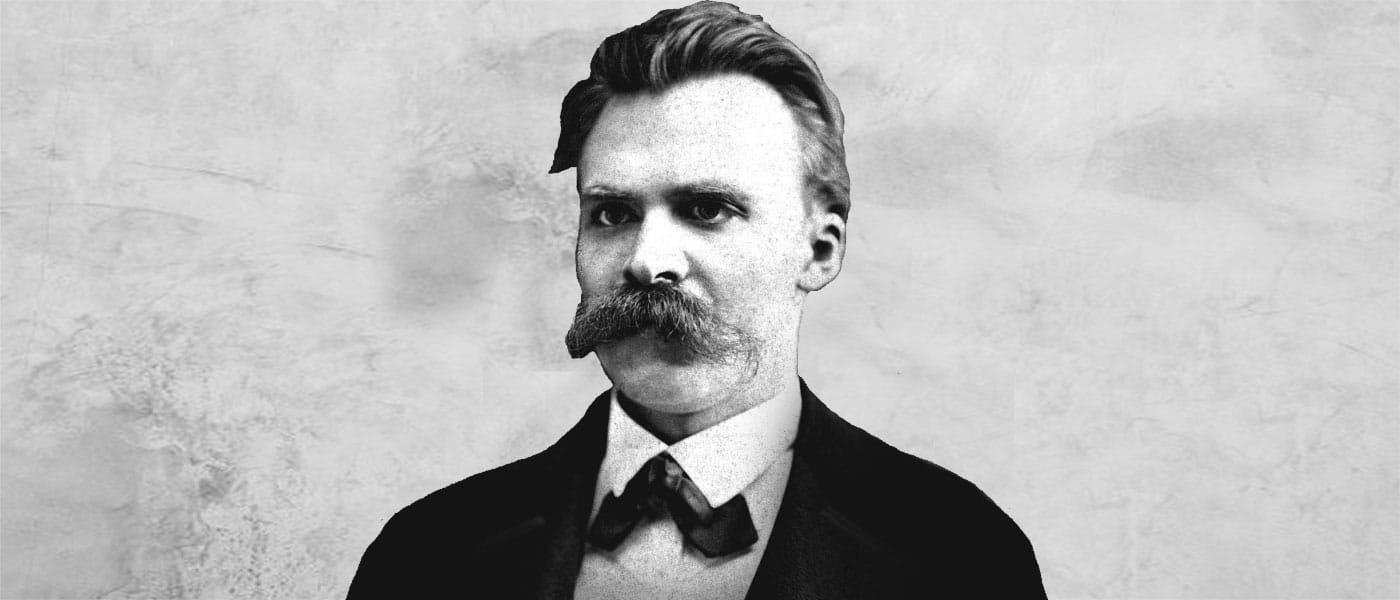

Big Thinker: Friedrich Nietzsche

BY Joseph Earp

Joseph Earp is a poet, journalist and philosophy student. He is currently undertaking his PhD at the University of Sydney, studying the work of David Hume.

Those regular folk are the real sickos: The Bachelor, sex and love

Those regular folk are the real sickos: The Bachelor, sex and love

Opinion + AnalysisRelationshipsSociety + Culture

BY Joseph Earp 4 NOV 2022

In 2021, the star of the US iteration of The Bachelorette, Katie Thurston, made international news off the back of one thirty second clip. In it, Thurston, all smiles and fey giggles, announced that she was forbidding the male contestants searching for her endless love from masturbating.

“I kind of had this idea I thought would be fun, where the guys in the house all have to agree to withhold their self-care as long as possible, if you know what I mean,” Thurston told the show’s two hosts, to a great deal of laughter and blushing. What was she was doing was what Bachelorette stars – and indeed many of those who feature in that brand of modern reality television focused on love and sex – have done for years.

Namely, she was upholding the show’s characteristic, and very strange, mix of euphemism and the explicit stating of norms that are so well-trodden in the culture that they’re not even acknowledged as norms at all.

Indeed, the most surprising thing about the clip was that it generated chatter, from both mainstream outlets and social media, in the first place. The Bachelorette’s habit of not so much ignoring the elephant in the corner, but ignoring the corner, and the walls connected to the corner, and perhaps even the entire room, has been part of its fabric from its very conception.

This is a show ostensibly about desire and love – which is a way of saying that it is about different states that circle around, and often lead to or follow from, sex – that shirks desperately away from most of the ways that we understand these things.

All we get on the desire front is a lot of people who pay a certain kind of attention to their bodies, occasionally – extremely occasionally – kissing one another. And all we get on the love front is a lot of talk about forever and eternity, along with roses, champagne flutes, and tears. Sex, meanwhile, lies far beyond the show’s window of acceptable or even conceivable behaviours. It’s there but it’s not there, a part of the very foundation of the show that’s still so taboo that if someone dares speak it aloud, as Thurston did, they’ll be the odd one.

This backlash to a bizarre norm constructed and maintained by the cameras was taken to an extreme in the case of Abbie Chatfield, a contestant on the Australian version of the show. For daring to tell Bachelor Matt Agnew that she “really wanted” to have sex with him, and admitting that she was “really horny”, Chatfield drew ire from not only the usual anti-sex bores, but from the so-called “sensible mainstream centre.” She was called a slut; her behaviour designated outrageous.

Such a backlash wasn’t just a policing of women’s bodies, though it was that. It was also a policing of the very standards of desire, part of a long attempt to prettify and clean up matters of sex and love, into “good” (read: socially acceptable) talk about these matters, and “bad” (read: unhinged, dangerous, impolite) talk about them.

In a society with a healthier understanding of sexuality, Chatfield wouldn’t be the deviation. The whole strange apparatus around her would be.

Whose Normal?

What makes The Bachelor and The Bachelorette such fascinating, internally frustrated objects is that their restating of the normal reaches such a volume, and resists so many specifics, that it reveals how utterly not-normal, arbitrary, and ill-defined most normal stuff is.

For instance, there is much talk in The Bachelor and The Bachelorette about romantic “compatibility”, a bizarre standard frequently talked about in the culture without ever being actually, you know, talked about. On this compatibility view of love, the pursuit of a significant other is a process of finding someone to fit into your life, as though you have one goal for how you want to be, and only one person who can help you achieve that. It’s that popular meme of the human being as an incomplete jigsaw puzzle, picking up pieces, one by one, and trying to slot them in.

What The Bachelor and The Bachelorette usually reveal, however, is that actually working out who is “the one” for you is much more difficult than the show’s own repeated emphasis on compatibility implies.

The stars of these shows frequently love and desire multiple people at the same time – the entire dramatic tension of the show comes from their final selection of a partner being surprising and tense.

If this compatibility stuff was as simple as it often described – or even clearly explicated – then we’d know after thirty seconds spent between potential two life partners that they’d end up together. There’d be no hook; no narrative arc. Eyes would lock, hearts would flutter, and the puzzle piece would just slot in.

In actuality, on both of these shows, the decision to pick one person over another frequently feels deeply random, and the always vague star usually has to blur their explanations even further into the abstract to justify why they want to be with him, and not with him, or with him.

The Bachelor and The Bachelorette are supposedly triumphant testaments to monogamy – almost all seasons of the show, except the one starring Nick Cummins, the Honey Badger, end with two and only two people walking off together.

But actually, in their typically confused way, they also end up explicating the benefits of polyamory. Often, the stars of these shows have a lot of fun, and derive a lot of pleasure and purpose from being intimate and romantic with a number of people at the same time. When it comes time to choose their “one”, it is frequently with tears – on a number of occasions, the stars have said, in so many words, “why not both?”

Get Those Freaks Away From Me

And why not both? Or more than both? The season of The Bachelor where no contestant is eliminated, everyone goes on dates together, and they all end up having sex and falling in love with one another, is no stranger than the season where only two walk into the sunset.

Monogamy is a norm, which is to say that it is an utterly arbitrary thing spoken loudly enough to seem iron-wrought. Norms are forceful; they tell us that things are the way they are, and could be no other way. In fact, they are so forceful that they have to state not only their own definitional boundaries, but also the boundaries of the thing that they are not – not just pushing the alien away, but the very act of designating things alien in the first place.

It was the philosopher Michel Foucault who noted this habit of branding certain objects, habits, or people as “other” in order to better understand and designate the normal. The Bachelor and The Bachelorette do this both frequently and implicitly, never drawing attention to the hand that is forever sketching abrupt and hurried lines in the sand.

Just consider the things that would be astonishing in the shows’ worlds, without even having to be taboo. For instance, imagine a star being perfectly happy committing to none of the contestants, and merely having sex with a few of them, one after the other. Or a star choosing a contestant but, rather than speaking of their flawless connection together, emphasising “mere” fun, or “mere” pleasure.

None of the preceding critique of these shows is a call to eradicate romantic and sexual norms altogether, if such an definitional cleansing were even possible. We have to make decisions about how we navigate the world together, and norms become a shorthand way of describing these decisions. What we should remember throughout, however, is that we are free to change this shorthand up whenever we like. And more than that, we should resist, wherever possible, the urge to create the other.

After all, if The Bachelor and The Bachelorette tell us anything, it’s that those regular folks are the real sickos.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

But how do you know? Hijack and the ethics of risk

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Want to live more ethically? Try these life hacks

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

5 Movies that creepily foretold today’s greatest ethical dilemmas

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics explainer: The principle of charity

BY Joseph Earp

Joseph Earp is a poet, journalist and philosophy student. He is currently undertaking his PhD at the University of Sydney, studying the work of David Hume.

I'd like to talk to you: 'The Rehearsal' and the impossibility of planning for the right thing

I’d like to talk to you: ‘The Rehearsal’ and the impossibility of planning for the right thing

Opinion + AnalysisRelationshipsSociety + Culture

BY Joseph Earp 6 OCT 2022

Nathan Fielder’s The Rehearsal, perhaps one of the slipperiest works of modern television, aims to solve a very complex, deeply recurrent problem: how do we navigate our interpersonal relations, which are ever-changing, and filled with opportunities to let people down and harm those we love?

In the show, which constantly blends the real with the fake, the documentary with the theatrical, the off-kilter comedian Nathan Fielder’s solution is supposedly simple: he finds people who are preparing to have difficult conversations with friends and loved ones, and gives them the opportunity to rehearse these encounters ahead of time.

The idea behind this ridiculous, though oddly logical practice is thus: if these people have already rehearsed an uncomfortable exchange with a loved one, then they can predict for every variable. They can polish their approach. When conversations branch off into different directions, they will have accounted for that branching already, leaving them to always choose the best, most impactful response.

To aid his mentees in this practice, Fielder uses an ever-escalating series of interventions. He creates dialogue flow trees, in which conversations can be unveiled in their full myriad of possibilities. He stages strange obstructions, ranging from fake babies to simulated drug overdoses. He takes the joyous chaos of being what Jean-Paul Sartre called “a thing in a world” – an agent who is perceived by other agents, and whose actions affect them – and he tries to simplify it.

Saying The Rehearsal is definitively “about” anything is a mistake – it’s too ever-changing, too messy, for that. But certainly, in its focus on trying to do the right thing by simplifying a complex world so that it might be predicted, the show can serve as a model of the pitfalls of trying to rationalise and generalise. It is a warning to those philosophers from the analytic tradition who reduce a world that is precisely so joyous and beautiful because it is so chaotic. So complex. And so filled with the potential for harm.

Fielder’s methods for helping people confront their own mistruths, find love, or fit better into their communities, are guided by the principle of a kind of lopsided rationality. The methods are laughable, of course – Fielder is a comedian. But they follow a strict, internally coherent form of thought.

In essence, what Fielder tries to do is generalise. He takes the nuances of life’s difficult conversations, and he strips them down to their component parts – maps them out on a board, uses actors to play them out ahead of time.

For instance, in the show’s first episode, Fielder recruits Kor, a competitive and trivia-obsessed young man who is preparing to tell his close friends that he has lied for years about getting a master’s degree. Fielder hires an actress to play Kor’s most abrasive friend, gets that actress to uncover as much information as possible about the real person she is stepping into the shoes of, and then puts Kor and this performer in a set that precisely replicates the dimensions of the bar where the actual conversation will go down.

The method – reduce. Simplify. Abstract. And use that generalised version of a real-life situation to guide how the actual situation will play out. This kind of ethical reasoning is highly tempting to us. We often find ourselves drawn to it, as we move through our lives.

Sure, we might not go to the lengths that Fielder does in The Rehearsal. But we do practice tough conversations in the shower with ourselves, ahead of time. We draft and re-draft text messages, and base them on how we might imagine the person we send them to will respond. In essence, we use our “rationality” and “reason” to help us move through the world, drawing on past experiences to help us navigate future ones.

Trivia-obsessed Kor, in fact, is a specific example of this. He is most worried about revealing his deception to his abrasive friend because of how she’s behaved in the past. He rationalises that because he has seen her blow up at others, getting angry at the drop of a hat, that she’ll do the same in the future, and more specifically, do it to him. He starts with a real-world experience – incidents of her temper – and then generalises them to a rule – she will always get angry – using his rationality to try and deduce the future, and thus the best action.

But what this kind of rationality does not take into account is the way that human beings shift and change; the way that they surprise us. How often have we prepared for an outcome that hasn’t come to light? Stressed about confrontations that turn out not to be confrontations at all?

Rather than generalising away from the inherent changeability of those we love, or indeed any of those who we surround ourselves with, we should instead embrace what the philosopher Jurgen Habermas described as “communicative rationality.”

For Habermas, our rational faculties shouldn’t generalise us away from the world – they shouldn’t isolate us. Instead, they should be part of a process of “achieving consensus”, as Habermas put it. We make decisions with other people. While staying in contact with them.

This means, rather than being a witness to the world – viewing it and then reviewing it, and using what we see and learn to guide our ethics – we are an active participant in it. On this model, our thoughts, desires, and ethical behaviours are essentially collaborative. They are grounded in the real world, and the people around us.

Thus, on Habermas’ view, we never stop discussing, talking, engaging. We don’t do as Kor does – using his rationality to effectively step himself away from his abrasive friend, halting in the process of communicating with her. And we don’t do as Fielder does – creating an artificial replica of the world, rather than just living in the actual world.

When we take the Fielder method, instead of adopting Habermas’ position of making everything communicative, we lose that which makes the world what it is: its messiness, its changeability, its dynamic and fluid nature.

There is nothing logically wrong, broadly speaking, about the kind of rationality that involves a step away from the world – that leads us to run through possible outcomes in our head with ourselves. Difficult conversations do move through different points; do branch off. So it makes some kind of sense to imagine that we should be able to predict them. The error here is not one in internal consistency. The error is taking a step backwards from those around us when trying to work out what to do, rather than taking a step forward.

The joke of The Rehearsal is precisely that this internally consistent form of rationality is remarkably, laughably devoid of life. It’s cold. Alien. It aims to solve real world problems, but it does that by turning to a printed board of branching lines of dialogue, instead of other human beings.

And it’s not even useful. As it turns out, Kor, who is highly nervous about the encounter with his abrasive friend, has little to worry about. When he confronts her, rather than the actress he has been rehearsing with, she is largely unfussed. She doesn’t mind that Kor has misrepresented himself. She expresses understanding for his duplicity. It is all pretty chill. Laughably so, in fact.

What Kor shows us is the importance of remaining in the world. That means we might fail them – that we might do the wrong thing. But that’s better than hiding away in a world of Fielder’s whiteboards. Indeed, our failures tell us that we’re human, bungling from one awful mistake to another, trying, and then failing, and then, beautifully, trying again. Guided always by people. Living always in communities. Staying blissfully, painfully connected.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Paralympian pay vs. Olympian pay

READ

Society + Culture

6 dangerous ideas from FODI 2024

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Science + Technology

The complex ethics of online memes

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture

What are we afraid of? Horror movies and our collective fears

BY Joseph Earp

Joseph Earp is a poet, journalist and philosophy student. He is currently undertaking his PhD at the University of Sydney, studying the work of David Hume.

Who does work make you? Severance and the etiquette of labour

Who does work make you? Severance and the etiquette of labour

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + LeadershipRelationshipsScience + TechnologySociety + Culture

BY Joseph Earp 1 AUG 2022

There are certain things that some of us choose and do not choose, to tell those who we work with.

You come in on a Monday, and you stand around the coffee machine (the modern-day equivalent of the water cooler), and somebody asks you: “so, what did you get up to this weekend?”

Then you have a choice. If you fought with your partner, do you tell your colleague that? If you had sex, do you tell them that? If your mother is sick, or you’re dealing with a stress that society has broadly considered “intimate” to reveal, do you say something? And if you do, do you change the nature of the work relationship? Do you, in a phrase, “freak people out?”

These social conditions – norms, established and maintained by systems – are not specific to work, of course. Most spaces that we enter into and share with other people have an implicit code of conduct. We learn these codes as children – usually by breaking the rules of the codes, and then being corrected. And then, for the rest of our lives, we maintain these codes, often without explicitly realising what we are doing.

There are things you don’t say at church. There are things you do say in a therapist’s office. This is a version of what is called, in the world of politics, the “Overton Window”, a term used to describe the range of ideas that are considered “normal” or “acceptable” to be discussed publicly.

These social conditions are formed by us, and are entirely contingent – we could collectively decide to change them if we wanted to. But usually – at most workplaces, importantly not all – we don’t. Moreover, these conditions go past certain other considerations, about, say honesty. It doesn’t matter that some of us spend more time around our colleagues than those we call our partners. This decision about what to withhold in the office is frequently described as a choice about “professionalism”, which is usually a code word for “politeness.”

Severance, the new Apple television show which has been met with broad critical acclaim, takes the way that these concepts of professionalism and politeness shape us to its natural endpoint. The sci-fi show depicts an office, Lumon Industries, where employees are implanted with a chip that creates “innie” and “outie” selves.

Their innie self is their work self – the one who moves through the office building, and engages in the shadowy and disreputable jobs required by their employer. Their outie self is who they are when they leave the office doors. These two selves do not have any contact with, or knowledge of each other. They could be, for all intents and purposes, strangers, even though they are – on at least one reading – the “same person.”

The chip is thus a signifier for a contingent code of social practices. It takes something that is implicit in most workplaces, and makes it explicit. We might not consider it a “big deal” when we don’t tell Roy from accounts that, moments before we walked in the front door of the office, we had a massive blow-up over the phone with our partner. Which may help Roy understand why we are so ‘tetchy’ this morning. But it is, in some ways, a practice that shapes who we are.

According to the social practices of most businesses, it is “professional” – as in “polite” – not to, say, sob openly at one’s desk. But what if we want to sob? When we choose not to, we are being shaped into a very particular kind of thing, by a very particular form of etiquette which is tied explicitly to labor.

And because these forms of etiquette shape who we are, they also shapes what we know. This is the line pushed by Miranda Fricker, the leading feminist philosopher and pioneer in the field of social epistemology – the study of how we are constructed socially, and how that feeds into how we understand and process the world.

For Fricker, social forces alter the knowledge that we have access to. Fricker is thinking, in particular, about how being a woman, or a man, or a non-binary person, changes the words we have access to in order to explain ourselves, and thus how we understand things. That access is shaped by how we are socially built, and when we are blocked from access, we develop epistemic blindspots that we are often not even aware that we have.

In Severance, these social forces that bar access are the forces of capitalism. And these forces make the lives of the characters swamped with blindspots. Mark, the show’s hero, has two sides – his innie, and his outie. Things that the innie Mark does hurt and frustrate the desires of the outie Mark.

Both versions of him have such significant blindspots, that these “separate” characters are actively at odds. Much of the show’s first few episodes see these two separate versions of the same person having to fight, and challenge one another, with Mark striving for victory over outie Mark.

The forces of etiquette are always for the benefit of those in power. We, the workers at certain organisations, might maintain them, but their end result is that they meaningfully commodify us – make us into streamlined, more effective and efficient workers.

So many of us have worked a job that has asked us to sacrifice, or shape and change certain parts of ourselves, so as to be more “professional”. Which is a way of saying that these jobs have turned us into vessels for labour – emphasised the parts of us that increase productivity, and snipped off the parts that do not.

The employees of Lumon live sad, confused lives full of pain, riddled with hallucinations. The benefit of the code of etiquette is never to them. They get paid, sure. But they spend their time hurting each other, or attempting suicide, or losing their minds. Their titular severance helps the company, never them.

This is what the theorist Mark Fisher refers to when he writes about the work of Franz Kafka, one of our greatest writers when it comes to the way that politeness is weaponised against the vulnerable and the marginalized. As Fisher points out, Kafka’s work examines a world in which the powerful can manipulate those that they rule and control through the establishment of social conduct; polite and impolite; nice and not nice.

Thus, when the worker does something that fights back against their having become a vessel for labour, the worker can be “shamed”, the structure of etiquette used against them. This happens all the time in the world of Severance. As the season progresses, and the characters get involved in complex plots that involve both their innie and outie selves, the threat is always that the code of conduct will be weaponised against them, in a way that further strips down their personality; turns them into more of a vessel.

And, as Fisher again points out, because these systems of etiquette are for the benefit of the powerful, the powerful are “unembarrassable.” Because they are powerful – because they are the employer – whatever they do is “right” and “correct” and “polite.” Again, the rules of the game are contingent, which means that they are flexible. This is what makes them so dangerous. They can be rewritten underneath our feet, to the benefit of those in charge.

Moreover, in the world of the show, the characters “choose” to strip themselves of agency and autonomy, because of the dangling carrot of profit. This sharpens the satirical edge of Severance. It’s not just that the snaking rules of the game that we talk about when we talk about “good manners” make them different people. It’s that the characters of the show submit to these rules. They themselves maintain them.

Nobody’s being “forced”, in the traditional sense of that word, into becoming vessels for labour. This is not the picture of worker in chains. They are “choosing” to take the chip, and to work for Lumon. But are they truly free? What is the other alternative? Poverty? And what, actually, makes Lumon so different? A swathe of companies have these rules of etiquette. Which means a swathe of companies do precisely the same thing.

This is a depressing thought. But the freedom from this punishment lies, as it usually does, in the concept of contingency. Etiquette enforces itself; it punishes, through social isolation and exclusion, those who break its rules.

But these rules are not written on a stone tablet. And the people who are maintaining them are, in fact, all of us. Which means that we can change them. We can be “unprofessional.” We can be “impolite”. We can ignore the person who wants to alter our behaviour by telling us that we are “being rude.” And in doing so, we can fight back against the forces that want to make us one kind of vessel. And we can become whatever we’d like to be.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights

Democracy is still the least-worst option we have

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Trust

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture

Ask an ethicist: Is it OK to steal during a cost of living crisis?

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships, Society + Culture

The sticky ethics of protests in a pandemic

BY Joseph Earp

Joseph Earp is a poet, journalist and philosophy student. He is currently undertaking his PhD at the University of Sydney, studying the work of David Hume.

Based on a true story: The ethics of making art about real-life others

Based on a true story: The ethics of making art about real-life others

Opinion + AnalysisRelationshipsSociety + Culture

BY Joseph Earp 29 JUN 2022

In October of 2021, The New York Times published a long article called ‘Who Is The Bad Art Friend?’, a story of kidney donations, poetic license, and vicious authors falling over one another to write damning words about those they publicly called their friends. Within hours of it hitting the internet, it had become the story of the day. And then the day after that. And then the day after that.

The thrust of ‘Who Is The Bad Art Friend?’ is simple. Seven years ago, an aspiring author named Dawn Dorland donated a kidney, a selfless act motivated – at least on first glance – by pure charity. Rather than let this act remain anonymous, Dorland instead posted about it frequently across the internet, particularly in a digital writer’s group she was part of. One of the members of that group, Sonya Larson, began murmuring to other authors about what she saw as Dorland’s shameless desire for attention, turning Dorland and her donation into a particularly damning punchline.

But rather than keep her takedowns to private messages, Larson wrote a not-so-veiled short fiction story about Dorland and her perceived bent towards self-celebration. Titled ‘The Kindest’, the story draws heavily on Dorland’s life, and turns her into a warped and twisted version of herself; too arrogant and self-involved to behave in a genuinely charitable way, motivated only by pride and sickening grandiosity. Flash forward a few years, and Dorland had launched legal action against Larson over the story, a protracted battle that serves as the climax for ‘Who Is The Bad Art Friend?’

There is a good reason that the fallout between the two writers so firmly captured the attention of the internet. It’s not just the tone of ‘Who Is The Bad Art Friend?’, the writing is unabashedly gossipy, filled with back-and-forths between Larson and Dorland that are laced with enough invective to make your toes curl. It’s that the story provided an opportunity for the internet to agonize over a very old argument, given new life in the era of streaming and a fixation on true crime: who has the right to tell another’s story?

This Is Your Life

We tend to believe that we are the authors of our own life story – that we have an essential and inalienable hold over our own narratives. There is nothing, so one cultural myth goes, as sacrosanct and personal as our identity.

As such, those who adopt this view on identity consider the act of turning another human being’s life into art to be one steeped in ethical conundrums: an issue of consent and privacy, where the wishes of the subject must be valued over the artistic decisions of the author.

These are the people who took Dorland’s side in the ‘Who Is The Bad Art Friend?’ argument. They are also the people who have a bone to pick with the recent glut of “ripped from the headlines” media content, from Hulu’s Pam & Tommy, a fictionalised version of the media fallout after the release of Pamela Anderson’s sex tape, to Inventing Anna, a series following the rise and fall of Anna Delvey (real name Sorokin), a socialite who scammed her way through America’s upper class.

In each of these cases, a real-life story – with, in many cases, real-life victims – has been shaped into fiction, often without the subject’s consent.

Anderson herself pushed against Pam & Tommy being made, while Sorokin wrote an angry letter about the series from her jail cell.

But to believe that you – and only you – can tell your own story is to believe in a shaky foundational premise. Such an argument rests on the idea that each of us is hermetically sealed away from the world, and hold important and relevant insight into ourselves that no others hold.

It is the case that we know certain things about our lives that others do not. But we are embedded in a web of social relations, and in the imaginations and minds of all those we encounter. We are not, in fact, the faultless experts on ourselves. Our personality, such as it is, is shaped and tested in the minds of those who receive us. The delineations between “my story” and “your story” or “our story” are shakier than it might first appear. We are constructed by the world, not sat in opposition to it.

Why This Argument? Why Now?

People’s sacrosanct belief in the importance of their own personal identity – treated as though our narratives about ourselves are delicate pieces of crystal we hold close to our chests, too fragile to let anyone else hold, is tied to a growing retreat from structural and systemic issues, and an embracing of personal ones. The ultimate social currency is often not based in the story of many, but the story of one. “I am me, and nobody else could be me, and for that reason, nobody else could tell my story but me.”

On the whole, the creative scope of the streaming giants, particularly Netflix, and major Western movie studios, has changed tremendously, from the cultural to the individual. Adam Curtis, the documentarian, has pointed this out, bemoaning the fact that there are few artists looking to describe how life right now feels. In America, Australia and the UK in particular, mainstream creatives have limited desire to capture any experience that expands beyond very particular lived ones, that are presented as isolated, and unique.

The theorist and philosopher Christopher Lasch covered this decades ago, in his groundbreaking work The Culture of Narcissism. He addressed what he saw as a tendency to go inwards: faced by a souring political climate, Lasch argued Americans had traded a hope for big change, with a fixation on smaller, more intimate and cosmetic shifts.

It is no surprise then that, though arguments around the ethics of storytelling have been waging for decades, they have been given new poignancy by the frequency of creative projects that fixate on only one life, and the increasingly popular belief that we are alone, and lonely, and utterly unlike even those from our same cultural and class background.

The beauty of art is that it need never be blinkered in this way. I am not advocating for only one type of art, the cultural instead of the personal – and I don’t believe that Curtis or Lasch are either. That’s one way of falling into precisely the artistic stalemate we find ourselves in. It’s not hopping from one mode of storytelling to another, it’s mixing the two, providing a rich, mainstream creative palette.

In fact, the problem is a creative fixation, one that has begun to dominate swathes of cultural discourse and entertainment. A generation of storytellers have settled themselves into a rut, hashing the same old beats over and over, telling stories with the same foundational premise – we are not like each other. In turn, that means our questions about so much mainstream art are becoming repetitive, the discourses surrounding ‘Who Is The Bad Art Friend?’ and Pam & Tommy and Inventing Anna just familiar talking points shot weakly through with a desperate, failing dose of adrenaline.

The question, asked over and over again, is: “Who can tell my story?” But perhaps we should ask why we even consider it “my” story in the first place.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

The wonders, woes, and wipeouts of weddings

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Ageing well is the elephant in the room when it comes to aged care

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

This isn’t home schooling, it’s crisis schooling

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

In defence of platonic romance

BY Joseph Earp

Joseph Earp is a poet, journalist and philosophy student. He is currently undertaking his PhD at the University of Sydney, studying the work of David Hume.

You won't be able to tell whether Depp or Heard are lying by watching their faces

You won’t be able to tell whether Depp or Heard are lying by watching their faces

Opinion + AnalysisPolitics + Human RightsRelationshipsSociety + Culture

BY Joseph Earp 2 JUN 2022

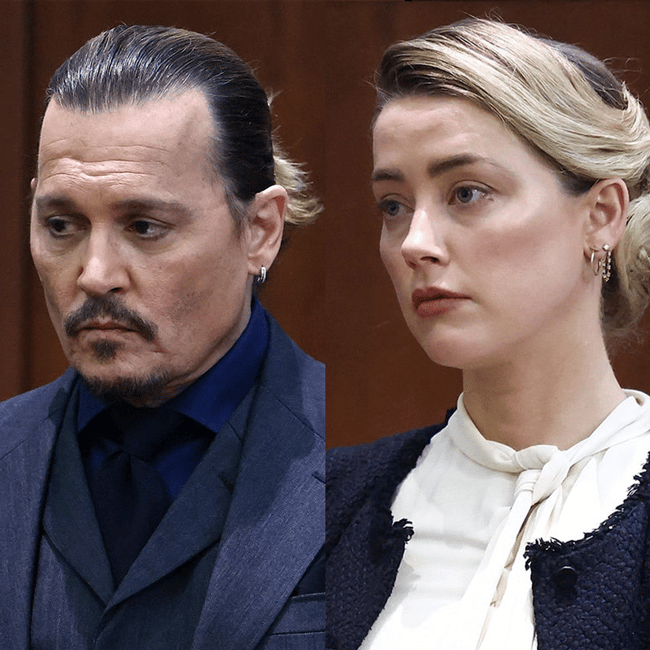

The Johnny Depp and Amber Heard defamation trial is now over.

Heard has been found guilty of defaming the actor with an op-ed she wrote – that did not name him explicitly – about being a survivor of domestic violence. Depp’s legal team too has been found guilty of defamation, but the amount that Heard has to now pay Depp is a much higher figure than he has to pay her.

The proceedings are done. But the media reaction to the trial – both from traditional outlets, and the deluge of posts about it crowding every single social platform like ants across an old plate of food – will linger.

This is because, in many circles, the all-too public spectacle has been treated like an unprecedented event. Pored over ad nauseum, it has been subject to endless thinkpieces, YouTube breakdowns, and Twitch streams. Twitter is awash with “fan edits”, compilations of carefully selected moments cut to the jaunty music usually associated with dance trends, or videos of dogs playing with each other in suburban backyards. There’s no use blocking keywords associated with it on social media. Videos still find a way to slip through, because the trial is everywhere.

This isn’t so surprising. The trial is on one level, a glimpse into the personal lives of the usually alien upper class. On another, it is shocking and disturbing enough – whichever side one takes – that it provides the vicious thrills that a culture which has become obsessed with true crime obsessively seeks out. This is all information, content. But how much of it do we need to make an informed decision about the outcome of the trial? And more than that, is this a useful kind of information? Where does it lead us? What does it give us?

The trial is foreign, it’s taboo, it’s ugly, and it’s glossy. What it isn’t, however, is quite as novel as it first seems.

Old Stories; New Faces

Much like the O.J. Simpson trial, or the proceedings against Lindy Chamberlain-Creighton, the Australian woman who claimed a dingo ate her baby, the Depp/Heard case is an example of a media-captivated society channeling abstract arguments through the lens of a high stakes legal proceeding, populated by faces that viewers have already developed complex parasocial relationships with. And, importantly, in each case, there has been an intense public scrutiny on how the figures in these cases should act – a fixation on their body language, their expressions, and the way they sound out words.

During the Simpson trial, the abstract arguments at play concerned race relations. Now, the tensions underlying the Depp/Heard trial are to do with what is sometimes referred to as our “post-metoo world”, a culture that has seen abusers reckoned with, and vast systems of deception that protect those abusers brought to light.

All of these court cases represented, and now represent, an opportunity for the public at large to discuss topics they might not normally have considered polite to bring up at the dinner table, or around the water cooler. “Is O.J. guilty?” was a way of saying, “tell me what you think about race and class in this country.” “Is Amber Heard a liar?” is now a way of saying, “what do you think abuse looks like? And what do we do about it?”

But there is at least one way that the Depp/Heard trial is involved with a trend that is breaking new ground. Unlike the Simpson trial, or the case against Chamberlain-Creighton, most viewers are watching the case through the internet. In turn, that means viewers have a unique ability to craft their own content about the proceedings, filtering key moments pulled from hours of footage through whatever pre-existing narrative they have constructed about the hero and the villain of this painful, and very sad story.

These content creators, who are often cutting together their videos in their spare time for no gain except rallying their audience around them, can watch over the trial’s footage as frequently as they like. They can scrutinize the same few seconds over and over; slow stretches of it down; freeze them in place.

In turn, that has turned a growing number of these amateur video essayists into amateur psychologists. A large subset of Depp/Heard content creators have come to believe that they can work out which of the players are lying by closely watching their expressions, unpacking their body language, and picking over the slightest tic, or absent gaze. For these sleuths, the case’s conclusion is as clear as Heard’s grimace, or the smile unfurling in the corner of Depp’s lips.

The Face Of A Liar

Those who seek to excavate the “truth” hiding beneath the trial by studying the body language and facial expressions of Depp and Heard start from a justifiable philosophical position. It was the philosopher Baruch Spinoza, a famous monist, who believed that every bodily state is underwritten by a mental state. For Spinoza, all things are of the one matter – variously called “nature”, or “God” by his intellectual interpreters. On this view, there is no distinction between any two substances, let alone a distinction between the way we hold ourselves, and what we think. The mind is the body, and the body is the mind.

From this starting point, it makes some sense to believe that the flesh might hold some insight into the secret thoughts and desires of two people who are very famous and very rich – and thus largely inaccessible, because nothing buys privacy like money and influence. Or, if not insight, then evidence gathered as post-hoc justification. Decisions as to guilt change based on a variety of factors – but they’re sometimes made early, and data can be gathered after those decisions have already been made, propping up pre-existing positions.

The mistake, however, is to generalise what these embodied states look like, and thus to generalise the emotional and mental states they are tied to.

There is, quite simply, no one way that all of us look when we lie, or are distressed, or happy. We are distinct in the way that we consider the world around us, and thus distinct in the way that we physically appear when we do.

Many of the “tell-tale signs” that get neurotically returned to, over and over again, on social media – Heard’s tone of voice, Depp’s drawl – could have any number of associated affective states, from anxiety, to pain, to yes, perhaps, the desire to lie. “It can be tough to accurately interpret someone through their body language since someone may feel tense or look uneasy for so many reasons,” said the therapist and author Dr. Jenny Taitz.

If we follow Spinoza, we will believe that our bodies and our thoughts are intertwined – but that’s not the same as saying the former will reveal the latter. These are slabs of affect, expressed both physically and mentally, but they are not as easily comprehensible as that makes them sound.

Indeed, psychological studies have proved for decades that none of us are skilled when it comes to weeding out those spinning “falsehoods”, and those not. A 2004 study of lying found that “agents of the FBI, the CIA and the National Security Agency – as well as judges, local police, federal polygraph operators, psychiatrists and laymen – performed no better at detecting lies than if they had guessed randomly.”

There is, after all, an immense social advantage to picking liars. If we could do it, and do it reliably, then that would be an invaluable skill, one we would expect to spread and be adopted across communities quickly. The fact that there is no dominant method of analysing the way our bodies twist and pose when speaking in itself speaks to the impossibility of using faces to get at what we mean when we talk about “the truth.”

Moreover, even most “body language experts” – an increasingly popular and media-saturated sub-set of pop psychologists, who have almost no science to back up their claims – admit that we need to get a baseline of our subject’s physical reactions before we can even attempt the fraught and mostly doomed work of trying to understand if they’re lying.

Which is to say, we need to at least know what people look like when they’re telling the truth before we can tell if they’re not. And we don’t know Johnny Depp, or Amber Heard, despite the illusion of closeness granted by social media. We don’t have enough data about how they move through the world, or what they look like when they do. How could we possibly guess at the motives and thoughts of utter strangers?

The Actors

Heard’s critics in particular have developed the line that she is a “performer”, going through the mere motions of grief and trauma – and not particularly well. They highlight a moment in which Heard appeared to pause while waiting for a cameraperson to snap a picture of her pained face, and another in which she seemed to flicker, composing herself for her next line as an actress on set would.

Of course, Heard is performing, on some level. But she is not performing in a way different to Depp. Though his defenders do not often note it, he too is signaling to the cameras, and to the jury – his smiles, and asides to his legal team, make that clear.

Nor, even, are these two distinct from the rest of us. We are all performing. We are social creatures, who have the ability to tell when we are being watched by others. Theory of mind, the term used to describe our understanding that other human beings see and think like we do, means that we can throw ourselves into the perspective of our observers. We do this constantly. It is part of what it means to have a body, and to be a person.

As philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre pointed out, we don’t even have to be actively watched to know that we could be watched. We carry with us the sense that we are what Sartre called a “thing in the world” – an entity that, at any time, could be stumbled across, and studied. As a result, we are always aware of ourselves, and how we might appear. Even when we are totally alone, we are never really alone. We are always with others – whether they’re flesh and blood observers, or ones we’ve made up in our head.

Where The Truth Lies

None of this has been an attempt to argue that Depp is telling the truth over Heard, or vice versa. It is not even a question of “truth”, as that word has been contemporaneously used.

The binary between the “real” and the “fake”, aggressively emphasised in media reactions to the trial, is itself overly simplistic, an outdated harbinger dangerously trickled down into the culture by analytic philosophy.

That is not to diminish the hurt, or the trauma, that clearly sits at the centre of the trial. That pain is real. That pain can be understood, but only when we look at the evidence in totality – the actual evidence, not the faces on the stand – and then causally tie it to certain parties.

We should, however, remember there is no objective state of affairs – no perfect place from which, like God, we can dispel the lies and embrace the world as it really is. The judge overseeing the Depp/Heard trial is not neutral. None of us are. At best, in this case as in so many others, we should, like the great pragmatist Richard Rorty, argue for ethnocentric justification for our claims, rather than tying them to a standpoint that sits outside of history, and belief, and bias. In doing so, we can embrace the changeability of our own positions – not on guilt and innocence, exactly, but the societal pressures that are so at play here – and examine them, seeing them as the flexible systems of thought that they are.

Throughout, however, we should remember that whatever we’re looking for when we hope to untangle a messy and painful relationship between two strangers who we will almost certainly never meet, it will not be found in their faces.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Enough with the ancients: it’s time to listen to young people

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

The problem with Australian identity

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

We already know how to cancel. We also need to know how to forgive

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

A parade of vices: Which Succession horror story are you?

BY Joseph Earp

Joseph Earp is a poet, journalist and philosophy student. He is currently undertaking his PhD at the University of Sydney, studying the work of David Hume.

Yellowjackets and the way we hunger

Yellowjackets and the way we hunger

Opinion + AnalysisRelationshipsSociety + Culture

BY Joseph Earp 10 MAY 2022

Yellowjackets, with its widely acclaimed first season, has a more disturbing element than its surface of considerable violence and horror.

Sure, the Showtime series, which follows a group of young athletes as they crash-land following a disastrous plane trip in the middle of the wilderness and turn, with visceral, enjoyable brevity, to cannibalism and taboo-shattering behaviour, contains a lot in the way of gore. There are broken limbs; bodies eating up bodies; physically construed nightmares which the protagonists cannot escape.

But underneath that immediate level of violence is a claim, considerably more unsettling than fractured calcium, that our ethical systems are far from stable and robust. We’re not bent towards virtue. We seem to be shaped in the opposite way. Yellowjackets knows that. And more than that, the show loves it.

Corruption Seeps In, Naturally

Yellowjacket’s “heroes” – a word which only means to indicate those characters who are applied with a particular, and frequently intense, narrative scrutiny – are the stereotypes of “ordinary” people. The show, which flips back and forth between the present and the deep, traumatic past, makes a great deal of effort to depict that. There are extended shots of the central characters, moving their way through the world, not even thinking about the trauma they inflicted on others, deep in their pasts.

Indeed, the flashback structure of proceedings, one that allows the central mystery to unfurl slowly – who ate who, following that terrible plane crash? – mines much from the main characters’ attempts to live their lives freely in the aftermath of their great collectively-constructed horror.

In the show’s temporal present, these plane crash survivors are all people who wake up every day, and apply themselves to their jobs, and are loved and love in turn. You’d meet them, and catch their eyes in a shopping centre, and smile, astonishingly oblivious of their histories. It’s only when we get painful stabs of their past, unfolded in flashback, that we come to understand that there is something hiding here; a history streaked by vicious behaviour.

That “something” can’t be pinned down to the specifics of our heroes’ lives, either. We can’t shirk the implication that we’d fail to avoid the same behaviour – it is nothing less than the human capacity for violence. We are all confronted, more frequently than we would like to admit, with the idea that we have a potential for evil.

Remember that time you stood on the train platform, and considered, all of a sudden, pushing a stranger onto the tracks? Not for any reason – just because you could. Because, despite what we hope ethics might teach us, there’s something actively joyful about vicious behaviour.

Yellowjackets doesn’t make anything extraordinary out of its central characters. These are just human beings, ones who happen to have been freed – predictably, almost boringly – from the social code of morality, and plunged into horror. We all could be there. All that Yellowjackets tells us is that, most worrying of all, we would enjoy it.

So Why?

The philosopher David Hume constructed his ethical system out of twin poles: pleasure and pain. Hume believed that we all have a natural repulsion to pain, and an attraction to pleasure. That, for him, was the foundation of all ethical behaviour, the starting point that explains empathy, charity, and goodness.

Yellowjackets tells us that’s not true. The show’s spark of originality is not to prove that we all have a propensity for inflicting suffering. That’s already been explored through multiple works of art – consider, for example, the Netflix smash hit Squid Game, which should be considered the contemporary final word on what happens when you guide desperate people towards viciousness.

No. What makes Yellowjackets special is that its central characters have spent the rest of their lives following the plane crash pursuing the highs of gnawing on another human being. They’re not tortured – they’re hungry.

We Do What We Want – Thank God

If that sounds horrifically bleak, it’s because, despite its considerable vein of humour, Yellowjackets is horrifically bleak. We are inundated with art that aims to provide us with a moral compass, designating bad and good behaviour, and telling us how to navigate both. The thematic work, quite often, in these pieces of popular culture, is to condition us emotionally – to train us to be repulsed by horror, and drawn to goodness.

Yellowjackets does not do this. It makes the horrendous appear attractive: “look at these regular people, who ate one another, and defied the social norm, and found themselves in the process.” And it makes the virtuous seem weak: “look at those fools who let their sense of goodness stop them from doing what they want to do.”

If there’s any hope here, then, it’s our capacity to understand pleasure and pain in a more complicated way than Hume did, and that much contemporary art concerned with morality encourages us to do so. Rather than monoliths of feeling – this is pleasurable, and thus morally good; this is not pleasurable, and thus morally bad – Yellowjackets encourages us to mine the depth of our affect, and see it as being filled with nuance.