We shouldn’t assume bad intent from those we disagree with

We shouldn’t assume bad intent from those we disagree with

Opinion + AnalysisRelationships

BY Karina Morgan 7 APR 2025

Polling by John Hopkins University in the lead up to the 2024 US election found that nearly half of eligible voters in the US believe that those in the opposing political party are “downright evil”.

This is likely an illustration of an attribution bias called “Motive Attribution Asymmetry”– one group’s belief that their rivals are motivated by emotions opposite to their own. To put it in simple terms: if I believe x and I believe I am a good person with good intentions, people who believe y must be evil.

Motive Attribution Asymmetry was coined in 2014, after five cross cultural studies identified a fundamental bias driving ‘seemingly intractable human conflict’. What these researchers found was that in political or ethno-religious intergroup conflict, adversaries tended to attribute aggression from their own side to ingroup love, and aggression from the opposing group to out-group hate.

A key word in the findings here is ‘intractable’. Can you actively listen, or seek to empathise, when you believe that your opponent’s beliefs and actions are grounded in hate? You’ve already, possibly unconsciously, assumed their intrinsic motivation is evil – and it’s an easy hop, skip and jump to dehumanisation from there.

In a New York Times column, Harvard Professor and Social Scientist, Arthur Brooks writes that motivation attribution asymmetry leads to contempt, which he says “is a noxious brew of anger and disgust, and not just contempt for other people’s ideas but also for other people”.

When we move from disagreeing, or even feeling contempt toward an idea, to contempt toward the whole person, we lose our humanity.

In the words of the 19th-century pessimistic philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer, contempt “is the unsullied conviction of the worthlessness of another.”

Let’s consider this in the larger scheme of human discourse.

It’s why it can be so hard for two people to hold a conversation who have deeply opposing views, because they don’t trust, or already have a subconscious bias toward, each other’s motives.

Has your dinner table ever erupted in conflict over opposing ideas? Or have you left a conversation feeling disgusted, wondering how, or if, you can continue the relationship with someone who supports something you’re vehemently against?

In these conversations, look for how you or the people around you respond to opposing ideas. Sarcasm, eye-rolling, sneering or hostile humor are all indicators of contempt according to renowned social psychologist John Gottman.

Schopenhauer also submits that if real contempt is shown, “it will be met with the most truculent hatred; for the despised person is not in a position to fight contempt with its own weapons.” Or, as we heard from the 2014 study, intractable conflict will ensue.

So what’s the panacea to motive attribution asymmetry and its toxic bedfellow of contempt? One person who has overcome her own biases is two-time Festival of Dangerous Ideas (FODI) alum Meagan Phelps-Roper.

A former born-and-raised, active member of the Westboro Baptist Church, Phelps-Roper left religious extremism behind after she encountered curiosity and a willingness to ask questions from some Twitter users. Their open-minded questions led her to ask her own, and ultimately choose a different path. Later, it was her appearance on stage at FODI 2018 that caused her to reflect on the importance of having difficult conversations in the public sphere.

Phelps-Roper’s tips for engaging with disagreement begin with a very important piece of advice: don’t assume bad intent. Assuming ill motive, she says, immediately cuts us off from accessing empathy, and prevents us from trying to understand why someone does or believes differently. It also blocks any potential for real dialogue. Her other tips include asking questions, staying calm, and articulating your own argument.

In her FODI 2024 session, The Witch Trials, alongside podcast producer Andy Mills, Phelps-Roper shared six prompts she asks herself in order to keep her own bias in check:

- Are you capable of entertaining real doubt about your beliefs? Or are you operating from a position of certainty?

- Can you articulate the evidence you would need to see in order to change your position? Or is your perspective unfalsifiable?

- Can you articulate your opponent’s perspective in a way that they recognise? Or are you straw-manning?

- Are you attacking ideas or attacking the people who hold them?

- Are you willing to cut off close relationships with people who disagree with you, particularly over small points of contention?

- Are you willing to use extraordinary means against people who disagree with you?

If, she says, the answer to any of these is yes, she knows she’s embarking on a ‘bad path’.

Perhaps next time you sit down alongside that opinionated uncle or sibling and the conversation takes a slippery turn, pause for a moment, then engage back with curiosity and the assumption of good – or even just neutral – intent.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Consequentialism

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Science + Technology, Society + Culture

5 things we learnt from The Festival of Dangerous Ideas 2022

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Uncivil attention: The antidote to loneliness

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Adoption without parental consent: kidnapping or putting children first?

BY Karina Morgan

Karina is a communications specialist, avid hiker and volunteer primary ethics teacher, with a penchant for the written word.

5 lessons I’ve learnt from teaching Primary Ethics

5 lessons I’ve learnt from teaching Primary Ethics

Opinion + AnalysisRelationships

BY Karina Morgan 18 FEB 2025

Each week, for 45 minutes, I sit down with a group of year two students and discuss ethics.

We’ll tackle an ethical concept or dilemma, typically in the form of a story, with questions designed to draw out deep discussion amongst the class.

The Ethics Centre established Primary Ethics as an independent not-for-profit in 2011, tasked with developing a curriculum and recruiting volunteers to run weekly ethics classes as an alternative in the scripture timeslot in public schools. They now deliver lessons to 45,000 children in 500 schools from kindergarten to year eight.

Classes are led by trained volunteers, who act as impartial facilitators. Our role is to model active listening and ask questions that build critical thinking skills and encourage collaborative learning.

For me, it feels like the most important gift I can give to the next generation. And, if I’m honest, I find I am learning in each and every class right alongside them.

Here are five lessons I’ve learned from teaching Primary Ethics this year:

1. Curiosity is the gateway to critical thinking.

Embracing curiosity is how we learn; it’s the driving force for growth, discovery, and innovation. The innate curiosity in children is a vital foundation for developing skills like critical thinking, empathy and thoughtful decision-making.

You see a curious mind doesn’t accept information at face value; it probes deeper, asking why, how, and what if? It fuels the critical examination of ideas, helps us to identify biases, to sort fact from fiction, and to consider situations from multiple perspectives.

I admire the unbridled curiosity of the students I teach. It’s contagious. As adults, we can get stuck in our routines and belief systems. We accept the status quo and stop exploring what’s possible.

2. There is power in saying “I don’t know”.

One of the most powerful moments this year came when a student asked a question I couldn’t answer. I took a breath and said, “I don’t know – what do other students think?”

And just like that, the room lit up. I had given the students permission to be knowledge holders and modelled the open-minded growth mindset we want to cultivate through ethics lessons. Since then I have witnessed so much more willingness to have a go from everyone in the room.

It turns out there’s a kind of magic in admitting you don’t have all the answers. Teaching ethics is not about being an authority; it’s about being a partner in figuring things out. Admitting you don’t know doesn’t make you weaker – it opens the door for connection and learning.

3. To disagree respectfully, we need to be open to learning from each other.

Nine-year-olds are full of opinions. But what also stands out to me is how open they are to new points of view, to listen to each other, even when they disagree. Recently, a student in my class said she disagreed with the person sitting next to her. That student smiled, said, ‘that’s ok’, and leaned into hearing her peer explain why. Imagine if we could cultivate that across the political divide?

Kids don’t assume the worst in someone who thinks differently – they assume they are trying their best, just as they themselves are. Watching them address and debate differing points of view without engaging in personal attack or any attempt to discredit each other is a beautiful reminder that respectful disagreement starts with empathy, assuming good intentions and willingness to learn from each other.

4. Psychological safety empowers new ideas, and even changes minds.

There’s a sense of psychological safety built through collaborative inquiry, because everyone’s ideas and questions are valid here. The kids thrive in the freedom it offers to explore, build on each other’s ideas, and even to change their minds.

When I started teaching this class two years ago, everyone was itching to have their turn, and to get the answer ‘right’. Now they have begun to really listen to each other – not just to respond, but to understand each other’s opinions.

This year there’s been instances where students have discussed feeling conflicted over a question, proposed merit across differing sides of a debate, and even changed their mind after listening to other points of view.

It’s a powerful reminder of how active listening can transform conversations. Making someone feel heard deepens trust, fosters empathy, and makes room for challenging conversations. It isn’t just a tool for learning; it’s a tool for connection.

5. Ethics in education can establish a resiliency for life.

Resilience, I fear, is a word that’s lost some of its charm for a lot of adults. Through ethics lessons I’ve been reminded that resilience isn’t the nefarious push through mentality or the ability to bounce back from a setback. It can also be staying engaged with challenging situations, even when the answers are messy or unclear. It’s regulating emotions, processing stress and being adaptable to change.

Ethics lessons are about grappling with tough questions, sometimes without any resolution. Nine-year-olds handle this better than you’d think, and certainly better than a lot of adults do. When there’s no clear answer, they meet the discomfort of uncertainty with curiosity and creative thinking.

Volunteer to become a Primary Ethics teacher and you’ll be helping children develop important skills for life. Find out more here.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

“I’m sorry *if* I offended you”: How to apologise better in an emotionally avoidant world

Big thinker

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Big Thinker: Germaine Greer

Big thinker

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

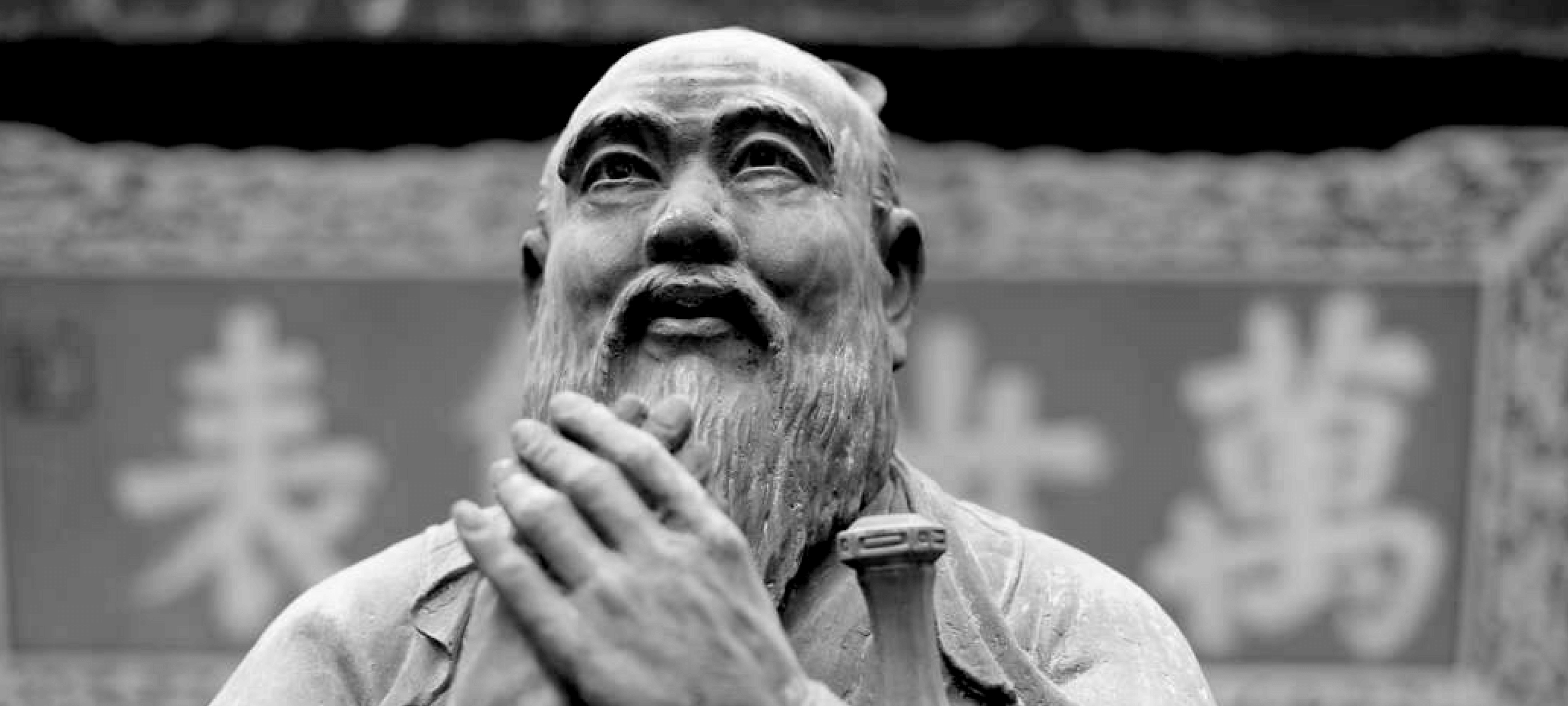

Big Thinker: Confucius

Big thinker

Climate + Environment, Relationships

Big Thinker: Ralph Waldo Emerson

BY Karina Morgan

Karina is a communications specialist, avid hiker and volunteer primary ethics teacher, with a penchant for the written word.

Seven COVID-friendly activities to slow the stress response

Seven COVID-friendly activities to slow the stress response

Opinion + AnalysisHealth + WellbeingRelationships

BY Karina Morgan 16 APR 2020

The coronavirus pandemic has affected nearly everything we do in our everyday lives. The things that give us joy and meaning – going to the gym, the beach, meeting friends for coffee – are no longer possible.

This is having a real impact on our mental health and capacity for good decision making. Beyond Blue have reported a four-fold increase in the number of calls and enquiries related to COVID-19 since March, a level far exceeding the period during the summer fires.

Our brains are wired to seek certainty and our neural circuits register unexpected events as threats. This triggers a fear response, known commonly as ‘fight or flight’, which causes a cascading chemical reaction in our bodies. That response prevents or impairs access to the higher levels of the brain where we deal with complex decisions.

So, it’s fair to say that uncertainty and fear reduce our capacity for quality decision making. This is, in part, because the area of impeded access involves the pre-frontal cortex, the part of our brain that actively processes information, accesses creative thinking and enables good decision making.

At its very core, ethics is about making good decisions. It asks us to consider all the ways we might act and to choose for the best. To take responsibility for our beliefs and our actions, and live a life that is entirely our own.

We know that many of you are facing challenging choices in circumstances that involve an unprecedented level of change and uncertainty in our individual and collective lives.

People are moving to work from home with kids in the house, facing job losses, closing businesses and deciding how to care for vulnerable loved ones. Many people are also experiencing the impacts of hyper-connection and feeling overwhelmed by the constant stream of new information.

With the sense of control and certainty taken from us, it’s easy for our decisions to be overcome by what we fear. With that in mind, it’s important to make time to find new activities that will help to activate the feel-good chemicals in our brains.

These seven activities can be practised while experiencing physical distancing. They are proven to slow down the stress response and boost your mood.

-

Take a nature break

2,500 years ago, Hippocrates, the Ancient Greek Physician and so-called ‘father of medicine’, said “walking is man’s best medicine”. Having invented the Hippocratic oath, he certainly wouldn’t lie! The moment you step outside the concrete jungle and into nature, your body shows its gratitude by releasing serotonin, a mood-regulating neurotransmitter. We are encouraged to stay at home. But if you have a backyard or nature reserve nearby, take regular breaks from the computer for fresh air or to use these spaces for exercise. Just be mindful to ensure you’re following recommendations and maintaining safe physical distancing in the process.

-

Move your body

Physical exercise acts like a power booster, it increases endorphins, the ‘peptide good guys’ that reduce pain perception and trigger positivity. Literally, happy days. Running and walking are great ways to shift pent-up energy. If you’re in self-isolation, try skip rope, something you could make, at a stretch, with a plastic cord or clothes line. A 32 year old French man ran the entire length of a marathon on his balcony during lockdown! Give yourself a tech-tox and move your body, ideally in nature, even if it’s just for ten minutes.

-

Take a bath

Many people experience a sense of calm around water and it’s no surprise if you consider the fact that our bodies are 60% water, and our brains more than 70%. Both Ayurveda and traditional Chinese medicine believe that the water element is crucial to rebalancing the body. With many beaches closed, look to what you can do within your own home. Fill up the bathtub and immerse your body in water. To super charge the experience you might even soften the lighting or drop in some essential oils to stimulate your senses.

-

Have a laugh

Laughter triggers the release of dopamine into the brain’s reward centre, giving you a high that lowers stress levels and increases your receptivity to pleasure. What may come as a surprise is that research also suggests that simply anticipating a laugh can have a similarly powerful effect. The expectation of something funny turns on our parasympathetic response system. So, it seems there’s never been a better time to practise your best ‘dad jokes’ on friends or the kids. There’s plenty of funny fodder available on streaming services. Check out Vulture’s list of the 50 best comedies on Netflix.

-

Practice yoga

The benefits of this ancient practise go far beyond the physical. In a yoga class, the combination of breath awareness and asana (postures) act to still the fluctuations of the mind and deepen your mind-body connection. Studies have shown that just a single one-hour yoga class can have a positive biochemical impact on your brain. Regular practise can reduce stress, anxiety, post traumatic stress disorder and depression. With traditional classes currently cancelled, many yoga teachers and studios are live streaming offerings, by donation or free of charge, for you to practise from home.

6. Listen to some tunes

Music makes your brain sing. You know that happy rush you get when your favourite song comes on the radio? It’s a chemical romance, one that lets off steam, injects the good vibes and let’s be real, is just a whole lot of fun. When music triggers your pleasure receptors dopamine is released into the striatum, the same part of the brain that responds to sex, chocolate, and is stimulated by artificial narcotics like cocaine. Research has also found that that some music has meditative qualities and can positively impact stress reduction and overall happiness. Fun fact: neuroscientists have found that listening to this song can reduce anxiety by up to 65%.

-

Dance it out

Dancing, like any other physical activity, releases neurotransmitters and endorphins to alleviate stress. Combining the dopamine response stimulated by music with these endorphins has the potential to supercharge your positivity. Plus, it’s almost certain that you’ll laugh along the way. Right now, you really can dance around the house like no one is watching. Prefer company? Have a virtual dance party. Many companies are rolling out video call dance breaks to manage the impacts of social isolation on extroverts in the workforce. Whether you want to do it with work, or friends, it’s easy to set up a time, pick a song, and all jump on a video call to dance it out together.

You can contact The Ethics Centre about any of the issues discussed in this article. We offer free counselling for individuals via Ethi-call; professional fee-for-service consulting, leadership and development services; and as a non-profit charity we rely heavily on donations to continue our work, which can be made via our website. Thank you.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Science + Technology

Making friends with machines

Opinion + Analysis

Climate + Environment, Health + Wellbeing

How should vegans live?

WATCH

Relationships

Consequentialism

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships, Science + Technology