Inside The Mind Of FODI Festival Director Danielle Harvey

Inside The Mind Of FODI Festival Director Danielle Harvey

Opinion + AnalysisRelationshipsSociety + Culture

BY The Ethics Centre 5 OCT 2018

We sat down with Festival of Dangerous Ideas 2018 festival director Danielle Harvey to take peak into the inspirations, motivations and challenges behind creating one of the most confronting and thought-provoking events in Australia.

1. It’s been said FODI was Australia’s first disruptive festival. What is it about the festival that resonates so strongly with audiences?

People want more than a headline. They want to hear more in depth analysis and a range of perspectives. To hear straight from the academics, scientists, researchers and not have it filtered, distorted. A live festival doesn’t get more direct.

2. There are so many different ideas, themes and perspectives out there that matter. How do you narrow it down to land this year’s line up?

A lot of vigorous discussion! Myself and the co-curators are always looking at the next thing that’s going to hit, we’ve been very good at looking at the horizon in past festivals, discussing things like Russia, surrogacy and banking all before a scandal breaks.

We also look to the superstars of the non-fiction world, the academics and researchers doing great work and are great communicators. And we look for a multitude of perspectives, beyond politics. A discussion that involves people from across disciplines, experts in their field that bring to light a focus on a particular aspect and when combined help to show the complex nature of many of our biggest ideas and problems.

3. The festival has been going strong for 9 years now. What gets easier, what doesn’t?

This is my 7th FODI. I feel very lucky to have been able to grow my own understanding of the world in a very public way! The easier and harder is the same – finding great people.

Easier because people around the world know about this festival and we have great alumni and reputation, harder because we’ve presented so many amazing people and so many ideas… I look forward to next year… 10 feels like a good ‘best of’ opportunity!

4. What does it take to be a great festival director?

Curiosity about the world. I’ve curated and created a number of festivals – FODI, Antidote, All About Women, BingeFest and Mardi Gras and they always start about thinking about audiences and what they should be able to see/hear/experience. I am insatiably curious and I love finding connections between things.

5. What’s it like to produce a festival like FODI? What does a typical day look like for you?

Talking. Talking. Appreciating the amazing team around me. (I have the best people who do so much). More talking. Noodling on the internet, reading, watching. Talking some more. (I talk to people from all different walks of life to hear what is interesting them).

6. What do you think sets the 2018 festival apart from recent years?

The island! The opportunity to fully immerse yourself in a program sans distractions. It’s all about the ideas and engaging with them deeply this year. The opportunity to include more large scale art and theatre has also made this a very different festival. We have the space and time to do these things on Cockatoo.

7. Why the move to Cockatoo Island and what are the challenges or surprises in setting up a festival in the middle of Sydney Harbour?

Everything has to be barged on! That’s the biggest challenge. It’s an amazing site, full of potential, but it is an island with no real infrastructure. The history of the place is incredibly evocative and any time we go there we are amazed at this little gem sitting on our doorstep. It’s a great place to let your mind and feet wander (and wonder)!

8. Finally, we have to ask. Which bit are you most to looking forward to? What are the must-see events?

That is tough, it will all be great! I am really looking forward to Chuck Klosterman, to Rukmini Callimachi and of course Stephen Fry! I think the ‘Too Dangerous’ panel will also be full of excellent take-aways.

I am also excited about the two art installations – ‘Submission’ and ‘The Hand That Wields It’ these installations are excellent opportunities to see ideas represented in a different way rather than via a talk.

Everything you need to know: The Festival Of Dangerous Ideas 2018

From sex robots to sex clowns, to tying yourself up in lies and rope, this year’s festival on 3 – 4 November takes you beyond the hype and deep into the issues that confront and divide us.

Embrace the festival experience on Cockatoo Island with one-day or full weekend passes. All passes include free return ferry transport.

Featured speakers include ex Westboro Baptist Church follower Megan Phelps-Roper, conservative historian Niall Ferguson; iconoclast Germaine Greer; rock star of AI Toby Walsh; micro-dosing advocate Ayelet Waldman; pop culture critic Chuck Klosterman; academic and activist Mick Dodson and so many more!

To crown FODI 2018, join Stephen Fry at a special event at Sydney Town Hall, where he will deliver an oration on the lost art of fabulous disagreement.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Pop Culture and the Limits of Social Engineering

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Anthem outrage reveals Australia’s spiritual shortcomings

Explainer

Relationships, Society + Culture

Ethics Explainer: Ethical non-monogamy

Opinion + Analysis

Science + Technology, Relationships

Love and the machine

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

TEC announced as 2018 finalist in Optus My Business Awards

TEC announced as 2018 finalist in Optus My Business Awards

Opinion + AnalysisRelationships

BY The Ethics Centre 28 SEP 2018

The Ethics Centre (TEC) is thrilled to be announced as a finalist for Training and Education Business of the year in the Optus My Business Awards for the second year running.

It’s an honour to be a finalist again after we were awarded winner of the category last year for our Ethical Professional Program.

The inaugural Optus My Business Award program reported record submission numbers this year, with leading SME’s across Australia vying for recognition in the 35 prestigious award categories.

This year we are proud to be finalists for our Ethi-call Counsellor Training Program (ECTP), completed by individuals hoping to become a volunteer Ethi-call Counsellor.

Ethi-call is a free national helpline available to anyone needing help to make their way through tough ethical challenges in their life. Made possible only through the support of volunteers who provide this service, this year we increased our capacity to deliver sessions by 300% through the ECTP program.

The eighteen-month program blends a diverse mix of learning techniques, resources and support networks to prepare students both emotionally and technically to handle the diverse range of calls received by the Ethi-call helpline.

Through an integrated learning program that bridges theoretical ethics with empathic counselling skills and practical delivery of the Ethi-call model, students are supported to develop the skills and understanding to develop as counsellors.

When asked what makes the ECTP so special, a recent graduate remarked:

“[TEC] Invest a great deal in this new Ethics Counselling Training Program to ensure callers to the Ethi-call service – who usually have extremely complex and often upsetting moral dilemmas in their personal and professional lives – receive the absolute best quality of service possible”

Program Manager Peta Andreone explained:

“Our duty is to ensure counsellors are capable to handle any type of call, and that our callers not only have access to a freely available service, but one that delivers the highest standard of care”

“Counsellors undergo intensive training to be registered through TEC, and participate in ongoing professional development to maintain their credentials annually”

The key innovation to the Ethi-call Counsellor Training Program is the Ethi-call Counselling Model, a working tool that has been developed and refined over the past 27 years.

An independent panel of judges will now review finalist submissions before deciding on this year’s awarded entries. Winners will be announced at a black-tie gala dinner on Friday, 9 November at The Star in Sydney.

Congratulations and good-luck to our fellow finalists in the Training and Education Business of the Year:

Code Camp

Engage & Grow

First Home Buyer Buddy

KICKBrick

Liberate eLearning

PD Training

STEM Punks

TCP Training

The Financial Fox

If you would like to train as an Ethi-call counsellor, send an expression of interested to counselling@ethics.org.au.

If you are facing a difficult ethical dilemma or decision, make a free appointment for a private conversation with an Ethi-call counsellor here.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

We need to talk about ageism

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture, Relationships

Do we exaggerate the difference age makes?

Big thinker

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Big Thinker: Shulamith Firestone

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

What is the definition of Free Will ethics?

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

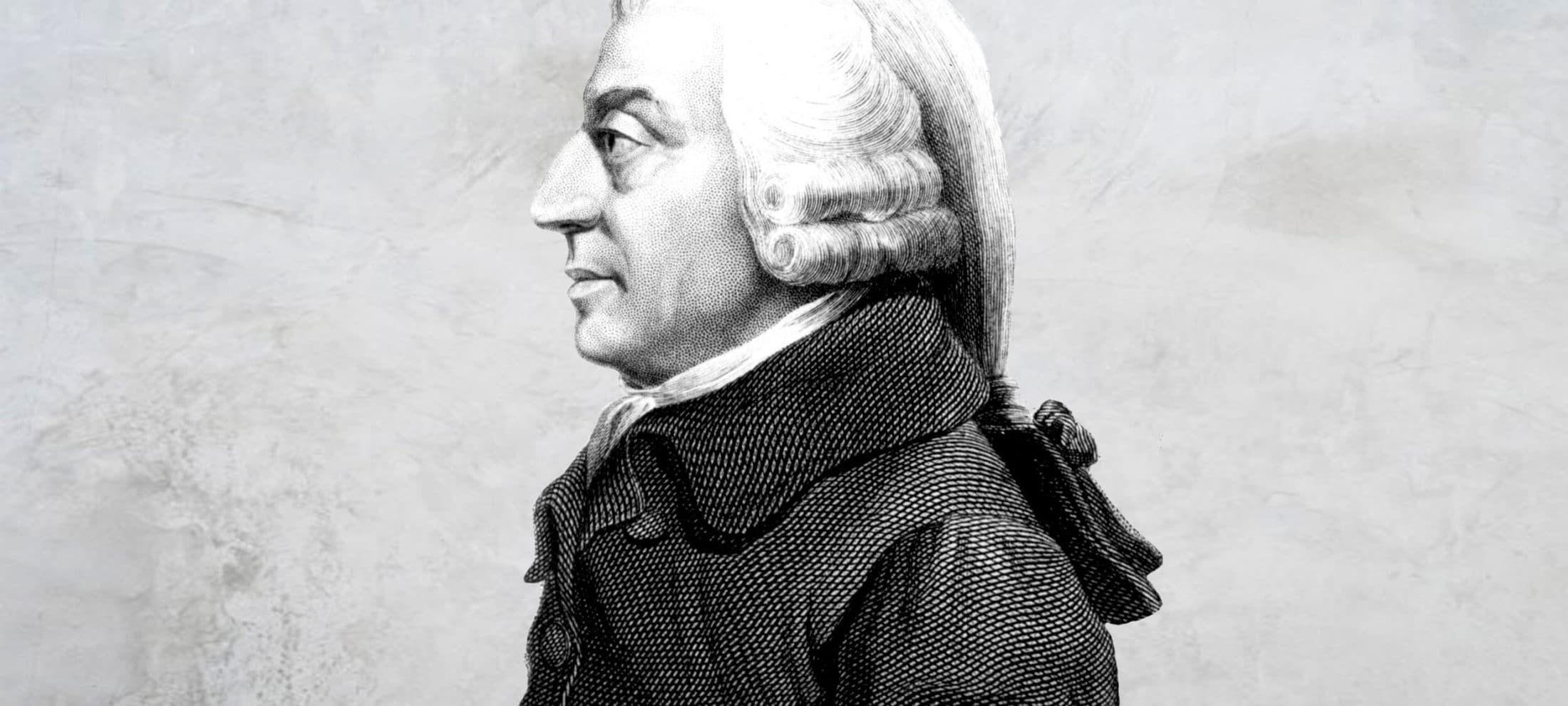

Big Thinker: Adam Smith

Big Thinker: Adam Smith

Big thinkerPolitics + Human RightsRelationships

BY The Ethics Centre 26 SEP 2018

It’s no exaggeration to say the ideas of Scottish moral philosopher Adam Smith (1723—1790) have shaped the world we live in.

By providing the core intellectual framework in defence of free markets, he positioned human liberty and dignity at the centre of trade and money – all for the common good.

Adam Smith, the pioneer

In the 18thcentury, the race to colonise as many resource rich places as possible meant powerful countries were often at war. Companies which added to the wealth of empires were protected by grateful governments, creating trade monopolies that seemed impossible to dismantle. This was the heyday of mercantilism.

Smith noticed how these actions created concentrations of wealth, benefiting the wealthy while the labour class struggled to survive. His first book, The Theory of Moral Sentiments, argued that the virtues of sympathy and reciprocity could tame greed.

His second, The Wealth of Nations, was about promoting a new way of approaching wealth that was as lucrative as it was just. The approach Smith adopted was multifaceted: economic, defensive, legal, and moral.

Smith argued that countries were competing for the wrong thing. Wealth wasn’t to be found in commodities like gold and silver. It resided in human labour and ingenuity. Smith encouraged countries that would normally look externally for wealth, suppressing the labour class and enslaving others, to look internally instead.

If the labour class could have the freedom to pick their job, all the while knowing the government would leave the money they made well alone, why wouldn’t they work hard at it? They would produce goods and services of even higher quality, and the government could buy these and trade them with each other. Everyone wins.

Collaboration would mean countries wouldn’t need to waste money on defence and war. They could save and accumulate capital, and invest that into better machinery, freeing people to work more productively. The labour class would grow richer, and so would the nation.

Smith stressed that in order for a free market to ensure fair pay for fair work, contracts had to be honoured, people had to keep their word, and governments mustn’t get into debt or take people’s property. Theft, negligence, mistakes, or irresponsible government spending must to be managed by the rule of law. And in the case of foreign powers, defence.

Thus, for Smith – a free market must rest on a sound ethical foundation. Given this, he argued for moral education of a kind that would lead people to be honourable and behave justly. This included the rich. Smith thought that an appeal to ‘enlightened’ self-interest might lead them to act honourably. By lavishing praise, accolades, and rewards on those who spend their wealth in charity, the rich gain the status and rank they really desire.

Adam Smith, the legacy

Claims of plagiarism, usury, inconsistency, racism, and all else aside, the major complaint directed towards Smith is his concept of the “invisible hand”. His observation that self-interested individuals end up benefiting the common good – that they are “led by an invisible hand to promote an end that was no part of his intention.” – has prompted some critics to label him naïve, idealistic, or even immoral.

The following quotation (misattributed to John Maynard Keynes) sums it up: “Capitalism is the astounding belief that the wickedest of men will do the wickedest of things for the greatest good of everyone”. But that plays into the Smith = laissez-faire trap, and ignores the safeguards he proposed against human corruption.

Smith did not think greed was good, saying this removed “the distinction between vice and virtue”, nor did he believe business interests and the public interest necessarily coincide. Instead, his perspective was that market competition forced people to act in ways that benefited others, regardless of their intention. And when it failed to do that, an overarching authority should step in. For Smith, markets have no intrinsic value – they are merely tools for the betterment of life for all.

No doubt the world we live in now is vastly different to pre-Industrial Scotland. Mass media, the Internet, the textile industry, factory farms, surveillance, housing prices, offshore tax havens…much would have seemed strange and unfamiliar to Smith. But his work and legacy leave a lesson in economics, ethics, and politics – all the more prescient in a world where the more things change, the more they stay the same.

Follow The Ethics Centre on Twitter, Facebook, Instagram and LinkedIn.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Society + Culture

When our possibilities seem to collapse

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

How to respectfully disagree

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

A parade of vices: Which Succession horror story are you?

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

How to break up with a friend

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Ethics Explainer: Stoicism

What do boxers, political figures, and that guy who’s addicted to Reddit all have in common?

They’ve probably employed the techniques of stoicism. It’s an ancient Greek philosophy that offers to answer that million dollar question, what is the best life we can live?

Hard work, altruism, prayer or relationships don’t take the top dog spot for the stoic. Instead, they zoom out and divide the world (if you’ll forgive the simplicity) into black and white: what you can control and what you can’t.

It’s the lemonade school of philosophy. The central tenet being:

“When life gives you lemons, make lemonade.”

Stoics believe that everything around us operates according to the law of cause and effect, creating a rational structure of the universe called logos. This structure meant that something as awful as all your worldly possessions sinking into the ocean (Zeno of Cyprus), or as annoying as missing the last bus by a quarter of a minute, don’t make your life any worse. Your life remains as it is, nothing more, nothing less.

If you suffer, you suffer because of the judgements you’ve made about them. The ideal life where that didn’t happen is a fantasy, and there’s no point focusing on it. Just expect that pain, grief, disappointment and injustice are going to happen. It’s what you do in response to them that counts.

This philosophy was founded by said Zeno, who preached the virtues of tolerance and self control on a stone colonnade called the stoa poikile. It’s where stoicism found its name. It flourished in the Roman empire, with one of its most famous students being the emperor himself, Marcus Aurelius. Fragments of his personal writing survive in Meditations, revealing counsel remarkably humble and chastising for a man of his power.

Stoicism on emotion

Emotion presents an opportunity. There’s a reactive, immediate response, like blaming others when you feel ashamed, or panicking when you feel anxious. But there is a better reaction the stoics aim for. It matches the degree of impact, is appropriate for the context, is rationally sound, and in line with a good character.

Being angry at your partner for forgetting to put away the dishes isn’t the same as being angry at an oppressive government for torturing its citizens. But if it’s the emotion you focus on, all your good intentions aren’t guaranteed to stop you from messing up. After all, the red haze is formidable.

By practising this “slow thinking” and making it a habit, you can cultivate the same self discipline to develop virtues like courage and justice. It’s these that will ultimately give your life meaning.

For others, emotions are more like the weather. It rains and it shines, and you just deal with it.

Stoicism assumes that focusing on control and analysing emotion is how virtues are forged. But some critics, including philosopher Martha Nussbaum, say that approach misses a fundamental part of being human. After all, control is transient too. Emotions – loving and caring for someone or something to such an extent that losing it devastates you – doesn’t make you less human. It’s part of being human in the first place.

Other critics say that it leads to apathy, something collective political action can’t afford. Sandy Grant, philosopher at University of Cambridge, says stoicism’s “control fantasy” is ridiculous in our interdependent, globalised world. “It is no longer a matter of ‘What can I control?’ but rather of ‘Given that I, as all others, am implicated, what should I do?”

Controlling emotion to navigate through life cautiously may not be desirable to you. But it is easy to see how channelling stoicism in certain situations can help us manage life’s unfortunate moments – whether they be missing the bus or something more harrowing.

Follow The Ethics Centre on Twitter, Facebook, Instagram and LinkedIn.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Climate + Environment, Politics + Human Rights, Relationships, Society + Culture

The youth are rising. Will we listen?

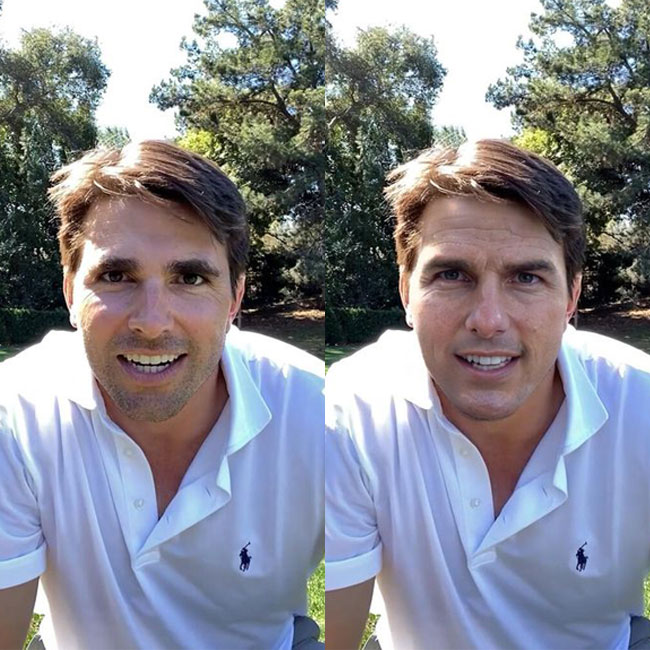

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Science + Technology

To see no longer means to believe: The harms and benefits of deepfake

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: The Other

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Come join the Circle of Chairs

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

The wonders, woes, and wipeouts of weddings

The wonders, woes, and wipeouts of weddings

Opinion + AnalysisRelationships

BY The Ethics Centre 20 SEP 2018

A wedding day – and all the kerfuffle beforehand – should come with a warning label. Ethical dilemmas ahead.

Decisions like: “Should I even have a wedding?” “Who should I invite?” “How much should I spend?” “Is this day really just about my partner and I?” “Do I have to invite my embarrassing uncle who drinks too much and flirts with the bridesmaids?” It can drive you spare.

Sure, taking the time to work things out won’t mean you know the right thing to do. But it’ll mean the decisions you come to will have been thoughtful and considered.

So if you’re stuck, start with purpose. What do you believe is the purpose of a wedding? And what actions are in line with that?

Purpose

Say a wedding is meant to be a celebration of the life that you two will build together. If that’s true, would you go into debt for that wedding, knowing that some of that future life will be spent paying it off? That answer really depends on you.

Would it make sense to skimp instead? Maybe. But if a celebration to you includes good food, drinks, live music, and cake, is that in line with the purpose of a wedding either?

“Hey,” you might be thinking. “A wedding isn’t about the two of us. It’s about everyone who’s been a part of our lives.” And fair enough! No one can argue with that. But if you’re juggling venue booking dates, your budget, and your dreams of having a week long wedding in Tahiti, remembering your guests and what they’d want can help you narrow it down. Sometimes multiple ceremonies and parties slim down people’s wallets and annual leave. Other times, it makes for a dream come true. You know your guests – and your purpose – best.

Wedding dilemmas splitting you in two? Book a free appointment with Ethi-call. A non-partisan, highly trained professional will help you see through chiffon to make decisions you can live by.

Duties

These same questions carry over into duties. Maybe you’re deciding who to invite and who not to. Remembering your duty to yourself, your partner, and your guests can all provide different perspectives. If you think the life you two will have together won’t include distant relatives or friends (especially relationships that were difficult or abusive), would it make sense to have them there on your wedding day?

But if you believe you have a duty to these people to invite them – be they family, old friends, or people you just need to invite – you might feel differently. No matter what you decide it’s worth asking, if you want to keep your guests happy and comfortable, would inviting difficult or disruptive people prevent that?

Consequences

These days, people aren’t the only things we’re concerned about. The impact of our weddings on the environment is something we’re much more conscious of. You might have wanted three thousand silver helium balloons on your wedding ever since you were a child, but you also just watched War on Waste and know that balloons end up in the tummies of lots of birds and turtles. Does the benefit outweigh the harm?

A good way to test if you’re cutting yourself too much slack on something you’d judge others for, is to shine it under the sunlight test. Would you still do it if it’d be on the front page of the newspaper tomorrow?

Character

As with anything, it’s worth considering whether it presents you as the type of person you believe you are – and living the values you and your partner share. Does your wedding display qualities you strive toward, like thoughtfulness, fun, and generosity? Or does it paint you as selfish, unprepared, and demanding? If the wedding you and your partner plan are inspired by shared values, chances are you’re on your way to plan a wedding that reflects these aspirations.

A wedding holds a lot of symbolism because of its importance in culture, religion, and history. Of course, it’s also fraught, often for the exact same reasons. If you’re in a “non-traditional” relationship or you disagree with marriage altogether, you might feel stuck between a rock and a hard place.

Does a wedding fit with the kind of person you want to be? Do you feel a sense of duty – to yourself, to your family, to your wider community, to social media, to God – to have a wedding? Do you believe weddings give you something you can’t get anywhere else? What about the specific traditions that make you ask, “Should I even have that?”

Being respectful of weddings and what they symbolise can make you think about how to make it your own.

Oh, and one final thing for anyone reading this. If you aren’t even sure you want to be with your partner, don’t have a wedding. The risk of a painful, humiliating, and expensive mistake is far too high.

Ethi-call is a free national helpline available to everyone. Operating for over 25 years, and delivered by highly trained counsellors, Ethi-call is the only service of its kind in the world. Book your appointment here.

Follow The Ethics Centre on Twitter, Facebook, Instagram and LinkedIn.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Big thinker

Relationships, Society + Culture

9 LGBTQIA+ big thinkers you should know about

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships

Employee activism is forcing business to adapt quickly

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

Big Thinker: Kwame Anthony Appiah

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Ask an ethicist: How much should politics influence my dating decisions?

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

The kiss of death: energy policies keep killing our PMs

The kiss of death: energy policies keep killing our PMs

Opinion + AnalysisClimate + EnvironmentScience + Technology

BY Kym Middleton The Ethics Centre 24 AUG 2018

If you were born in 1989 or after, you haven’t yet voted in an election that’s seen a Prime Minister serve a full term.

Some point to social media, the online stomping grounds of digital natives, as the cause of this. As Emma Alberici pointed out, Twitter launched in 2006, the year before Kevin ’07 became PM.

Some blame widening political polarisation, of which there is evidence social media plays a crucial role.

If we take a look though, the thing that keeps killing our PMs’ popularity in the polls and party room is climate and energy policy. It sounds completely anodyne until you realise what a deadly assassin it is.

Rudd

Kevin Rudd declared, “Climate change is the great moral challenge of our generation”. This strategic focus on global warming contributed to him defeating John Howard to become Prime Minister in December 2007. As soon as Rudd took office, he cemented his green brand by ratifying the Kyoto Protocol, something his predecessor refused to do.

There were two other major efforts by the Rudd government to address emissions and climate change. The first was the Carbon Pollution Reduction Scheme(CPRS) led by then environment minister Penny Wong. It was a ‘cap and trade’ system that had bi-partisan support from the Turnbull led opposition party… until Turnbull lost his shadow leadership to Abbott over it. More on this soon.

Then there was the December 2009 United Nations climate summit in Copenhagen, officially called COP15 (because it was the fifteenth session of the Conference of Parties). Rudd and Wong attended the summit and worked tirelessly with other nations to create a framework for reducing global energy consumption. But COP15 was unsuccessful in that no legally binding emissions limits were set.

Only a few months later, the CPRS was ditched by the Labor government who saw it would never be legislated due to a lack of support. Rudd was seen as ineffectual on climate change policy, the core issue he championed. His popularity plummeted.

Gillard

Enter Julia Gillard. She took poll position in the Labor party in June 2010 in what will be remembered as the “knifing of Kevin Rudd”.

Ahead of the election she said she would “tackle the challenge of climate change” with investments in renewables. She promised, “There will be no carbon tax under the government I lead”.

Had she known the election would result in the first federal hung parliament since 1940, when Menzies was PM, she may not have uttered those words. Gillard wheeled and dealed to form a minority government with the support of a motley crew – Adam Bandt, a Greens MP from Melbourne, and independents Andrew Wilkie from Hobart, and Rob Oakeshott and Tony Windsor from regional NSW. The compromises and negotiations required to please this diverse bunch would make passing legislation a challenging process.

To add to a further degree of difficulty, the Greens held the balance of power in the Senate. Gillard suggested they used this to force her hand to introduce the carbon tax. Then Greens leader Bob Brown denied that claim, saying it was a “mutual agreement”. A carbon price was legislated in November 2011 to much controversy.

Abbott went hard on this broken election promise, repeating his phrase “axe the tax” at every opportunity. Gillard became the unpopular one.

Rudd 2.0

Crouching tiger Rudd leapt up from his grassy foreign ministry portfolio and took the prime ministership back in June 2013. This second stint lasted three months until Labor lost the election.

Abbott

Prime Minister Abbott launched a cornerstone energy policy in December 2013 that might be described as the opposite of Labor’s carbon price. Instead of making polluters pay, it offered financial incentives to those that reduced emissions. It was called the Emissions Reduction Fund and was criticised for being “unclear”. The ERF was connected to the Coalition’s Direct Action Plan which they promoted in opposition.

Abbott stayed true to his “axe the tax” slogan and repealed the carbon price in 2014.

As time moved on, the Coalition government did not do well in news polls – they lost 30 in a row at one stage. Turnbull cited this and creating “strong business confidence” when he announced he would challenge the PM for his job.

Turnbull

After a summer of heatwaves and blackouts, Turnbull and environment minister Josh Frydenberg created the National Energy Guarantee. It aimed to ensure Australia had enough reliable energy in market, support both renewables and traditional power sources, and could meet the emissions reduction targets set by the Paris Agreement. Business, wanting certainty, backed the NEG. It was signed off 14 August.

But rumblings within the Coalition party room over the policy exploded into the epic leadership spill we just saw unfold. It was agitated by Abbott who said:

“This is by far the most important issue that the government confronts because this will shape our economy, this will determine our prosperity and the kind of industries we have for decades to come. That’s why this is so important and that’s why any attempt to try to snow this through … would be dead wrong.”

Turnbull tried to negotiate with the conservative MPs of his party on the NEG. When that failed and he saw his leadership was under serious threat, he killed it off himself. Little did he know he would go down with it.

Peter Dutton continued with a leadership challenge. Turnbull stepped back saying he would not contest and would resign no matter what. His supporters Scott Morrison and Julie Bishop stepped up.

Morrison

After a spat over the NEG, Scott Morrison has just won the prime ministership with 45 votes over Dutton’s 40.

Killers

We have a series of energy policies that were killed off with prime minister after prime minister. We are yet to see a policy attract bi-partisan support that aims to deliver reliable energy at lower emissions and affordable prices. And if you’re 29 or younger, you’re yet to vote in an election that will see a Prime Minister serve a full term.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture, Climate + Environment

Who’s to blame for overtourism?

Opinion + Analysis

Climate + Environment, Health + Wellbeing

Donation? More like dump nation

Opinion + Analysis

Science + Technology

On plagiarism, fairness and AI

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Science + Technology

The new rules of ethical design in tech

BY Kym Middleton

Former Head of Editorial & Events at TEC, Kym Middleton is a freelance writer, artistic producer, and multi award winning journalist with a background in long form TV, breaking news and digital documentary. Twitter @kymmidd

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

From NEG to Finkel and the Paris Accord – what’s what in the energy debate

From NEG to Finkel and the Paris Accord – what’s what in the energy debate

Opinion + AnalysisClimate + EnvironmentRelationshipsScience + Technology

BY The Ethics Centre 20 AUG 2018

We’ve got NEGs, NEMs, and Finkels a-plenty. Here is a cheat sheet for this whole energy debate that’s speeding along like a coal train and undermining Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull’s authority. Let’s take it from the start…

UN Framework Convention on Climate Change – 1992

This Convention marked the first time combating climate change was seen as an international priority. It had near-universal membership, with countries including Australia all committed to curbing greenhouse gas emissions. The Kyoto Protocol was its operative arm (more on this below).

The Kyoto Protocol – December 1997

The Kyoto Protocol is an internationally binding agreement that sets emission reduction targets. It gets its name from the Japanese city it was ratified in and is linked to the aforementioned UN Framework Convention on Climate Change. The Protocol’s stance is that developed nations should shoulder the burden of reducing emissions because they have been creating the bulk of them for over 150 years of industrial activity. The US refused to sign the Protocol because the two largest CO2 emitters, China and India, were exempt for their “developing” status. When Canada withdrew in 2011, saving the country $14 billion in penalties, it became clear the Kyoto Protocol needed some rethinking.

Australia’s National Electricity Market (NEM) – 1998

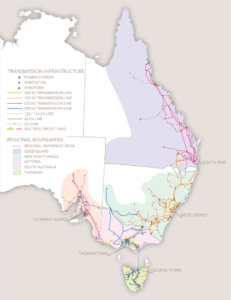

Forget the fancy name. This is the grid. And Australia’s National Electricity Market is one of the world’s longest power grids. It connects suppliers and consumers down the entire east and south east coasts of the continent. It spans across six states and territories and hops over the Bass Strait connecting Tasmania. Western Australia and the Northern Territory aren’t connected to the NEM because of distance.

The NEM is made up of more than 300 organisations, including businesses and state government departments, that work to generate, transport and deliver electricity to Australian users. This is no mean feat. Before reliable batteries hit the market, which are still not widely rolled out, electricity has been difficult to store. We’ve needed to continuously generate it to meet our 24/7 demands. The NEM, formally established under the Keating Labor government, is an always operating complex grid.

The Paris Agreement aka the Paris Accord – November 2016

The Paris Agreement attempted to address the oversight of the Kyoto Protocol (that the largest emitters like China and India were exempt) with two fundamental differences – each country sets its own limits and developing countries be supported. The overarching aim of this agreement is to keep global temperatures “well below” an increase of two degrees and attempt to achieve a limit of one and a half degrees above pre-industrial levels (accounting for global population growth which drives demand for energy). Except Australia isn’t tracking well. We’ve already gone past the halfway mark and there’s more than a decade before the 2030 deadline. When US President Donald Trump denounced the Paris Agreement last year, there was concern this would influence other countries to pull out – including Australia. Former Prime Minister Tony Abbott suggested we signed up following the US’s lead. But Foreign Minister Julie Bishop rebutted this when she said: “When we signed up to the Paris Agreement it was in the full knowledge it would be an agreement Australia would be held to account for and it wasn’t an aspiration, it was a commitment … Australia plays by the rules — if we sign an agreement, we stick to the agreement.”

The Finkel Review – June 2017

Following the South Australian blackout of 2017 and rapidly increasing electricity costs, people began asking if our country’s entire energy system needs an overhaul. How do we get reliable, cheap energy to a growing population and reduce emissions? Dr Alan Finkel, Australia’s chief scientist, was commissioned by the federal government to review our energy market’s sustainability, environmental impact, and affordability. Here’s what the Review found:

Sustainability:

- A transition to low emission energy needs to be supported by a system-wide grid across the nation.

- Regular regional assessments will provide bespoke approaches to delivering energy to communities that have different needs to cities.

- Energy companies that want to close their power plants should give three years’ notice so other energy options can be built to service consumers.

Affordability:

- A new Energy Security Board (ESB) would deliver the Review’s recommendations, overseeing the monopolised energy market.

Environmental impact:

- Currently, our electricity is mostly generated by fossil fuels (87 percent), producing 35 percent of our total greenhouse gases.

- We’re can’t transition to renewables without a plan.

- A Clean Energy Target (CET), would force electricity companies to provide a set amount of power from “low emissions” generators, like wind and solar. This set amount would be determined by the government.

-

- The government rejected the CET on the basis that it would not do enough to reduce energy prices. This was one out of 50 recommendations posed in the Finkel Review.

ACCC Report – July 2018

The Australian Competition & Consumer Commission’s Retail Electricity Pricing Inquiry Report drove home the prices consumers and businesses were paying for electricity were unreasonably high. The market was too concentrated, its charges too confusing, and bad policy decisions by government have been adding significant costs to our electricity bills. The ACCC has backed the National Energy Guarantee, saying it should drive down prices but needs safeguards to ensure large incumbents do not gain more market control.

National Energy Guarantee (NEG)– present 20 August 2018

The NEG was the Turnbull government’s effort to make a national energy policy to deliver reliable, affordable energy and transition from fossil fuels to renewables. It aimed to ‘guarantee’ two obligations from energy retailers:

- To provide sufficient quantities of reliable energy to the market (so no more black outs).

- To meet the emissions reduction targets set by the Paris Agreement (so less coal powered electricity).

It was meant to lower energy prices and increase investment in clean energy generation, including wind, solar, batteries, and other renewables. The NEG is a big deal, not least because it has been threatening Malcolm Turnbull’s Prime Ministership. It is the latest in a long line of energy almost-policies. It attempted to do what the carbon tax, emissions intensity scheme, and clean energy target haven’t – integrate climate change targets, reduce energy prices, and improve energy reliability into a single policy with bipartisan support. Ambitious. And it seems to have been ditched by Turnbull because he has been pressured by his own party. Supporters of the NEG feel it is an overdue radical change to address the pressing issues of rising energy bills, unreliable power, and climate change. But its detractors on the left say the NEG is not ambitious enough, and on the right too cavalier because the complexity of the National Energy Market cannot be swiftly replaced.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

Big Thinker: Kwame Anthony Appiah

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Ending workplace bullying demands courage

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Consequentialism

Opinion + Analysis

Climate + Environment, Politics + Human Rights

Are we prepared for climate change and the next migrant crisis?

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Big Thinker: Germaine Greer

Big Thinker: Germaine Greer

Big thinkerPolitics + Human RightsRelationships

BY The Ethics Centre Kym Middleton Aisyah Shah Idil 20 AUG 2018

Feminist firebrand or second wave scourge? When The Female Eunuch was published to international success, it was obvious Germaine Greer (1939—present) had hit a nerve – something she continues to do.

This article contains language and content that may be offensive to some readers.

Germaine Greer is an Australian writer and public intellectual who rose to international influence with her book published in 1970, The Female Eunuch. It was a watershed text in second wave feminism, a bestseller around the world, and it made Greer a household name.

Greer’s infamously bold voice and sense of humour permeates throughout the book. Her strong character and take no prisoners approach to public debate saw her regularly contribute to panels and broadcast media. Greer was launched into the public eye as a young, bolshie feminist star.

Since then, Greer has written many books spanning literature, feminism and the environment. She has become one of Australia’s most ‘no-platformed’ thinkers. Almost five decades on, we take a look at her contributions to feminist philosophy.

Human freedom is intrinsically tied to sexual freedom

Greer is a liberation, rather than equality feminist. She believed achieving true freedom for women meant asserting their uniquely female difference and “insisting on it as a condition of self-definition and self-determination”.

Greer wanted to be certain about this female difference, and for her, this certainty started with the body.

You can think of Greer’s claims like this:

- Women are sexually repressed.

- Men are not sexually repressed.

- The difference between men and women is their biological sex.

- Biological sex determines if you’re sexually repressed or not.

The second part of her argument is as follows:

- Women are expected to be ‘feminine’.

- Women are sexually repressed.

- The expectation to be ‘feminine’ is sexually repressive.

Greer is scathing in her portrayal of ‘femininity’. She claimed it kept women docile, repressed, and weak. It stifled women’s sexual agency, hence the ‘eunuch’, which was intrinsically tied to their humanity.

Only by liberating women sexually could they remove this imposed submissiveness and embrace the freedom to live the way they wanted.

“The freedom I pleaded for twenty years ago was freedom to be a person, with dignity, integrity, nobility, passion, pride that constitute personhood. Freedom to run, shout, talk loudly and sit with your knees apart.” – Germaine Greer (1993)

A feminist utopia is an anarchist utopia first

In the London Review of Books 1999, Linda Colley wrote, “Properly and historically understood, Greer is not primarily a feminist. More than anything else, she should be viewed as a utopian.”

For Greer, the greatest danger of the widespread female eunuch is not an unfulfilling sex life. It is in her being so concerned with femininity that she is incapable of political action. Greer believed this social conditioning was dire and its enforcers so embedded that revolution rather than reform was required.

Greer called for this revolution to start in the home. She spoke openly about topics that at the time were taboo: menstruation, hormonal changes, pregnancy, menopause, sexual arousal and orgasm. She decried the agents of femininity that she felt kept women trapped: makeup, constricting clothing, feminine hygiene products, stifling marriages, misogynistic literature and female sexual competitiveness. She reserved her greatest fury for widespread consumerism, which she believed kept women dependent on the systems that forged their own oppression.

Like Mary Wollstonecraft before her, Greer argued neither men nor women benefited from this. She called upon women to rebel again these “dogmatists” and create a world of their own. But the solution she presents is exploratory instead of pragmatic. Perhaps women could live and raise their children together, making their own goods and growing their own food. It would be somewhere pleasant like the rolling landscapes of Italy, with local people to tend house and garden. (It’s unclear whether these local people would be liberated too.)

Intellectual criticisms

Greer’s celebration of non-monogamous sex in The Female Eunuch and her derision of Western society’s obsession with sex in Sex and Destiny led critics to label her ideas slipshod and too inconsistent for a public intellectual.

The root of most criticisms and controversies surrounding Greer, tend to stem from her view of the sexes. Like other second wave feminists, she suggested biological sex determined women’s oppression. This stands in stark contrast to the perspectives of third wave feminists and queer theorists, such as Judith Butler, for whom gender’s learned behaviours play the crucial role.

Greer and her contemporaries are often criticised by third and fourth wave feminists for predicating their philosophies on a male/female binary. A binary that does not account for the broad chromosomal spectrums found among intersex people or the many ways in which individuals feel and express their gender.

Infamous commentary

Greer is not the docile feminine woman she warned of in The Female Eunuch. She has long been celebrated for bucking trends and being refreshingly bold and frank. She is also heavily criticised for being rude, offensive and out of touch. She has been described as having “the self-awareness of a sweet potato”, a “misogynist”, and “a clever fool”.

After she extolled the work of Australia’s first female Prime Minister Julia Gillard on an episode of ABC’s Q&A, she was slammed for criticising Gillard’s body and clothing:

“What I want her to do is get rid of those bloody jackets … They don’t fit. Every time she turns around you’ve got that strange horizontal crease which means they cut too narrow in the hips. You’ve got a big arse Julia…”

Social media lit up with calls for Greer to “shut up” after she linked rape and bad sex in the age of #MeToo:

“Instead of thinking of rape as a spectacularly violent crime – and some rapes are – think about it as non-consensual, that is, bad sex. Sex where there is no communication, no tenderness, no mention of love. We used to talk about lovemaking.”

It is probably Greer’s public statements around transgender women that have attracted the most protest. In an interview after an intense no-platforming campaign to cancel a lecture Greer was scheduled to give at Cardiff University on women and power in the 20th century, she said, “Just because you lop off your penis and then wear a dress doesn’t make you a fucking woman”.

This sentiment probably links with Greer’s ideas on sexed bodies. A sympathetic reading of the comment might see it as one about being born into oppression – a rather second wave feminist sentiment that echoes the racial and queer politics of the same era. An idea that’s sometimes cited as analogous to Greer’s controversial comment is that you cannot understand what it is to be black, unless you were born black and experienced discriminations since the day of your birth. Perhaps she was suggesting we cannot understand the oppression experienced by women and girls unless we are born into a female body. Perhaps not. Either way, the comment was received as incredibly offensive and naive to transgender women’s experiences.

“People are hurtful to me all the time. Try being an old woman. I mean for goodness sake! People get hurt all the time. I’m not about to walk on eggshells.” – Germaine Greer, 2015

Greer and second wave feminists generally are at odds with intersectional feminism which is prominent today. Intersectional feminism holds that many factors beyond sex marginalise people – age, race, nationality, disability, class, faith, sexual orientation, gender identity… Different women will be oppressed to varying degrees.

Whether Greer is a trailblazer or tactless provocateur, it is doubtless her ideas have influenced the political and personal and landscapes of gender relations and feminist thinking.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

Meet Daniel, helping us take ethics to the next generation

Big thinker

Relationships

Seven Female Philosophers You Should Know About

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Climate + Environment

What we owe each other: Intergenerational and intertemporal justice

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

You are more than your job

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

BY Kym Middleton

Former Head of Editorial & Events at TEC, Kym Middleton is a freelance writer, artistic producer, and multi award winning journalist with a background in long form TV, breaking news and digital documentary. Twitter @kymmidd

BY Aisyah Shah Idil

Aisyah Shah Idil is a writer with a background in experimental poetry. After completing an undergraduate degree in cultural studies, she travelled overseas to study human rights and theology. A former producer at The Ethics Centre, Aisyah is currently a digital content producer with the LMA.

The energy debate to date – recommended reads

The energy debate to date – recommended reads

Opinion + AnalysisClimate + Environment

BY The Ethics Centre 18 AUG 2018

Australia, we put it to you. ‘Is it too soon to ditch fossil fuels?’ We’ve waded through political waters and presented our shiniest pearls for your perusal.

Cheat Sheet

From NEG to Finkel and the Paris Accord – what’s what in the energy debate

The Ethics Centre

18 October 2018

Before action must come knowledge. And before knowledge must come sorting through a heap of confusing, jargonistic, off-putting acronyms, reviews, and accords. Worry not, we’ve got your back and did it for you. Our cheat sheet will brush you up on all those names that keep getting dropped in the Australian energy debate like they’re hot coals.

Video

Australia’s energy crisis: “Absolute shambles, national embarrassment and a disgrace”

7.30, ABC News

Ian Verrender

13 Feb 2017

This 7.30 report is a perfect backgrounder to the mess that is Australia’s energy crisis. The NEM broke leaving hot and bothered South Australians without electricity (you read the cheat sheet so you know the NEM is a fancy acronym for the grid). A Victorian power plant that supplied 20 percent of the state’s energy simply closed shop. Renewables are unreliable but fossil fuels are killing the planet. Holy calamity!

Interactive

They Vote For You – How does your MP vote on the issues that matter to you?

Open Australia Foundation

If you’re rearing to parade your opinion, hold on. Haste makes waste. While we’re between elections, how about taking a look at how your local MP voted on energy? Did they champion a fast switch to renewables or continued support for fossil fuels like coal and gas? Forget what they said in the run up to an election and check out what they did.

Movie

And one for fun. Maybe a post-apocalyptic energy crisis isn’t so bad if we can also have double-necked flame guitars.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture, Climate + Environment, Politics + Human Rights

Why you should change your habits for animals this year

Opinion + Analysis

Climate + Environment, Politics + Human Rights

Australia Day: Change the date? Change the nation

Opinion + Analysis

Climate + Environment, Science + Technology

The kiss of death: energy policies keep killing our PMs

Big thinker

Climate + Environment

Big Thinker: Bill Mollison

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Ethics Explainer: Authenticity

Is the universe friendly? Is it fundamentally good? Peaceful? Created with a purpose in mind?

Or is it distant and impersonal? Indifferent to what you want? A never ending meaningless space? We all have ideas of how the world truly is. Maybe that’s been influenced by your religion, your school, your government, or even the video games you played as a kid.

Whatever the case is, how we think about ourselves and what we consider a life well spent, has a lot to do with the relationship we have with the world. And that brings us to this month’s Ethics Explainer.

Authenticity

To behave authentically means to behave in a way that responds to the world as it truly is, and not how we’d like it to be. What does this mean?

Well, this question takes us to two different schools of thought in philosophy, with two very different ideas of the nature of the world we live in. The first one is essentialism. Now, essentialism is a belief that find its roots in Ancient Greece, and in the writings of Socrates and Plato.

They took it as a given that everything that exists has its own essence. That is, a certain set of core properties that are necessary, or essential, for it to be what it is. Take a knife. It doesn’t matter if it has a wooden handle or a metal one. But once you take the blade away, it becomes not-a-knife. The blade is its essential property because it gives the knife its defining function.

Plato and Aristotle believed that people had essences as well, and that these existed before they did. This essence, or telos, was only acquired and expressed properly through virtuous action, a process that formed the ideal human. According to the Greeks, to be authentic was to live according to your essence. And you did that by living ethically in the choices you make and the character you express.

By developing intellectual virtues like curiosity or critical thinking, and character virtues like courage, wisdom, and patience, it’d get easier to tell what you should or shouldn’t do. This was the standard view of the world until the early 19th century, and is still the case for many people today.

The rise of existentialism

But some thinkers began to wonder, what if that wasn’t true? What if the universe has no inherent purpose? What if we don’t have one either? What if we exist first, then create our own purpose?

This belief was called existentialism. Existentialists believe that neither us nor the universe has an actual, predetermined purpose. We need to create it for ourselves. Because of this, nothing we do or are is actually inherently meaningful. We were free to do whatever we wanted – a fate Jean Paul-Sartre, French existential philosopher, found quite awful.

Being authentic meant facing the full weight of this shocking freedom, and staying strong. To simply follow what your religious leader, parent, school, or boss told you to do would be to act in “bad faith”. It’s like burying your head in the sand and pretending that something out there has meaning. Meaning that doesn’t exist.

By accepting that any meaning in life has to be given by you, and that ‘right’ and ‘wrong’ are just a matter of perspective, your choices become all you have. And ensuring that they are chosen by the values you accept to live by, instead of any predetermined ones etched in stone, makes them authentic.

This extends beyond the individual. If the world is going to have any of the things most of us value, like justice and order, we’re going to have to put it there ourselves.

Otherwise, they won’t exist.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Big thinker

Relationships

Big Thinker: Jean-Paul Sartre

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships

How the Canva crew learned to love feedback

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

What ethics should athletes live by?

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships, Society + Culture