We’re in this together: The ethics of cooperation in climate action and rural industry

We’re in this together: The ethics of cooperation in climate action and rural industry

Opinion + AnalysisClimate + EnvironmentBusiness + Leadership

BY Cris Parker 14 APR 2025

“We’re in this together” is easy to say, but much harder to do – especially when people’s livelihoods, land, and the planet’s future are at stake.

Australia is committed to reducing emissions and shifting to renewable energy. However, for many rural and regional communities – particularly those tied to coal, gas, or agriculture, they sit at the crossroads of opportunity and uncertainty. These areas are rich in culture, industry, and community and are also heavily shaped by commercial imperatives – the need for jobs, services, and sustainable growth.

Unfortunately, climate action can feel more like an impending threat than a shared opportunity. These communities often experience change as something done to them, rather than with them.

Bridging this gap demands more than just policy and technology. Climate change is one of the biggest challenges of our time, but tackling it isn’t just about switching to solar panels or building wind farms either. It’s about ethical cooperation – a commitment to fairness, transparency, and shared responsibility in how we plan and implement climate solutions. If not done ethically, commercial development can disrupt local culture, raise living costs, and put pressure on fragile ecosystems.

At its heart, cooperation is about shared goals. But in climate policy, those goals don’t always look the same to everyone. For city campaigners, a ‘just transition’ means phasing out coal and gas. For a local worker in Gladstone or the Hunter Valley, it might sound like job losses without a safety-net.

Different philosophical perspectives can help us to understand how we can apply ethical cooperation as we pursue our shared goals. Whether it’s about consequences, duties and obligations, or people’s rights, all are underpinned with the values and principles of transparency, fairness, and mutual respect and dignity.

‘Just transition’ sounds good, but what does it mean in practice? As researchers Marshall and Pearce put it: “Many people in regional communities have no concrete understanding as to what a ‘just transition’ refers to and do not find it to be authentically their syntax”.

The proposed Hunter Transmission Project in NSW, for example, has been met with strong resistance from landowners. While the project is intended to support clean energy infrastructure, many locals say the process lacked transparency and ignored community concerns about land use, agriculture, and environmental impacts.

British philosopher Onora O’Neill focuses on trust and consent in cooperative systems. She argues that ethical cooperation requires conditions where all parties have genuine capacity to consent, particularly in asymmetrical relationships (e.g. government vs local communities). These principles have been embedded in The Clean Energy Council’s national guide which advises that developers must prioritise “clear, accessible and accurate information” and ensure projects are co-designed with communities to reflect cultural, economic and environmental priorities.

When AGL closed Liddell Power Station in 2023, the company committed to a transition plan. But many workers reported uncertainty and a lack of clarity about what would come next. For a transition to be truly ‘just’, it needs to include more than retraining promises. It needs local job pipelines, early engagement, and co-designed solutions.

Israeli philosopher Yotam Lurie says that once people engage in joint activity, they take on moral obligations to each other. In the case of climate action, that means governments, industries and communities must not only work together, but they must also do so with care, trust, and respect.

Rural resistance often stems from real economic vulnerabilities and perceived exclusion from decision-making, not from climate denial.

Encouragingly there are areas where we are seeing ethical cooperation working well.

In Gippsland, Victoria, the Gunaikurnai people are working with renewable energy developers to co-design solar projects. These partnerships embed cultural knowledge, ensure local employment, and protect Country showing that ethical cooperation isn’t just a principle. It’s a practical strategy for success.

The First Nations Clean Energy Network has also shown how co-owned and co-designed projects can reduce costs, build trust, and deliver long-term economic and environmental benefits.

Climate change is often framed as a technical problem. But it’s also a human one. If we want a sustainable future, we must build it together with ethics, empathy, and equity at the centre.

As Australian philosopher, Peter Singer suggests, we are morally obligated to reduce the suffering of others which would support a coordinated action where affluent corporations aid vulnerable groups, such as rural or Indigenous communities affected by the energy transition.

Governments and companies have a responsibility to fund and support this process. That includes advisory boards, transparent impact assessments, and long-term partnerships built on trust.

If we want rural and regional communities to lead rather than lag in the net-zero transition, we need to take ethical cooperation seriously and build trust within the human system. Sometimes the hardest part is putting aside self-interest, regardless of the good intent and work together to understand the shared purpose. Acknowledging the tensions and being honest about the trade-offs is a strong place to start. This can be done through deep listening and ‘story telling’ that demonstrates respect for cultural and ecological values, rather than just economic ones.

Tackling climate change is not just about reducing emissions, it’s about justice and fairness, because “we’re in this together” only works when everyone has a say, and everyone has a stake.

The Energy Charter is a member of the Ethics Alliance and a one-of-a-kind, CEO-led coalition of energy organisations united by a shared passion and purpose: delivering for customers and empowering communities in the energy transition.

BY Cris Parker

Cris Parker is the former Head of The Ethics Alliance and a Director of the Banking and Finance Oath at The Ethics Centre.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Sell out, burn out. Decisions that won’t let you sleep at night

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Is employee surveillance creepy or clever?

Explainer, READ

Business + Leadership

Ethics Explainer: Moral hazards

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

6 Things you might like to know about the rich

Ask an ethicist: Why should I vote when everyone sucks?

Ask an ethicist: Why should I vote when everyone sucks?

Opinion + AnalysisPolitics + Human Rights

BY Simon Longstaff 10 APR 2025

As time goes on, I’m feeling more disenfranchised by politics. I don’t trust any of the current politicians and it seems they don’t represent issues that are affecting everyday Australians, particularly as the inequality gap is widening. Why should I vote this upcoming election, and does my vote even matter?

The issue of voting in Australian elections is often clouded by the mistaken belief that ‘voting is compulsory’. This really annoys people who feel that it impinges on their liberty as citizens – a liberty that should include the right to decide not to vote. In fact, Australia does not impose ‘compulsory voting’. Instead, there is a policy of ‘compulsory turning up’. What we do when we enter the privacy of the polling booth is entirely up to us. We can cast a valid vote. We can leave the ballot paper unmarked. We can write a screed setting out our views. Basically, we can do whatever we like – just as long as we turn up, collect the voting papers and deposit them in the ballot box.

Some will still object to the need to turn up. It won’t matter to them that the need to do so is one of a very small set of obligations that our country has imposed on all its citizens to maintain a well-functioning democracy.

But let’s just assume that, either willingly or reluctantly, we find ourselves in the polling booth – ballot papers in hand – and have to decide whether or not to cast a valid vote. What should we have in mind as we decide?

First, it’s worth remembering that democratic elections do have the potential to bring about change. If we feel that something is wrong with society, then the vote you cast can, in principle and sometimes in practice, enable reforms for the better. It’s understandable to think that your individual vote might not amount to much. But the arc of history is directed by the aggregated effect of individual votes. Alone, this might not amount to much, but collectively it can change the world. Indeed, the fate of a government can sometimes rest on a foundation as fragile as a single vote in a marginal electorate.

Of course, not all of us live in marginal electorates. In apparently ‘safe’ seats it might seem like your vote will be wasted if you cast it for a candidate who apparently has no chance of beating the likely ‘favourite’. Yet, this thinking runs the risk of becoming self-fulfilling. You never know what might happen if just enough people make the same choice you do – and in doing so bring about an unanticipated victory for a candidate who seemed to have no chance of winning. There are many examples of once ‘safe’ seats being lost by major parties that have held them for generations. Just look at the rise in the number of community independents now sitting in our parliaments. They are only there because a majority of citizens preferred them to others and voted accordingly.

It can also work the other way – where you vote for a candidate who apparently already has enough votes to win. Your vote is not ‘redundant’ because the size of a candidate’s margin of victory can be seen as indicative of community support. A larger margin can lend a representative a greater mandate or more political capital to enact their agenda.

Another problem might be that there is not a single candidate or party that you could support in good conscience. There may not even be a ‘least bad’ (but acceptable) option. In any case, with preferential voting there are no ‘wasted votes’. Every ballot counts towards the eventual result. That is one of the problems with choosing to vote ‘informally’ (returning an unmarked ballot). Doing so will make no positive difference to the outcome. The only ‘upside’ is that you might feel that you avoid complicity in enabling an outcome that you could not support in any case.

Yet, perhaps part of our role as electors is to accept that there will be times when the best we can hope for is the ‘least bad’ result. We may have to reconcile ourselves to the fact that there will be occasions when nothing truly inspiring is on offer. If we’re denied the opportunity to vote for someone who reflects our values and principles – and advances our view of what makes for a good world – we might still see value in using our vote to help block those who would undermine everything we stand and hope for.

This brings us to one of the core reasons for voting. Unlike other political systems where authority is derived from God (theocracies) or wealth (plutocracies) or ‘virtue’ (aristocracies), in democracies the ultimate source of authority comes from those who are ‘the governed’ (the people). We get to decide how decisions are made – through popular control of what is in our Constitution. We also get to choose the representatives who will make laws on our behalf. In the end, we have as much control over the system of government as we choose to exercise.

What limits the exercise of that control is not the system – it is our willingness to become politically active.

If you like living in a democracy – but don’t want to get too involved in shaping the system – then there is a low-cost, potentially high impact way to help shape the way it operates. It is to vote.

Image: Gillian van Niekerk / Alamy Stock Photo

BY Simon Longstaff

Simon Longstaff began his working life on Groote Eylandt in the Northern Territory of Australia. He is proud of his kinship ties to the Anindilyakwa people. After a period studying law in Sydney and teaching in Tasmania, he pursued postgraduate studies as a Member of Magdalene College, Cambridge. In 1991, Simon commenced his work as the first Executive Director of The Ethics Centre. In 2013, he was made an officer of the Order of Australia (AO) for “distinguished service to the community through the promotion of ethical standards in governance and business, to improving corporate responsibility, and to philosophy.” Simon is an Adjunct Professor of the Australian Graduate School of Management at UNSW, a Fellow of CPA Australia, the Royal Society of NSW and the Australian Risk Policy Institute.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

A critical thinker’s guide to voting

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

If you don’t like politicians appealing to voters’ more base emotions, there is something you can do about it

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Society + Culture

Why sometimes the right thing to do is nothing at all

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Ethics in a time of coronavirus

We shouldn’t assume bad intent from those we disagree with

We shouldn’t assume bad intent from those we disagree with

Opinion + AnalysisRelationships

BY Karina Morgan 7 APR 2025

Polling by John Hopkins University in the lead up to the 2024 US election found that nearly half of eligible voters in the US believe that those in the opposing political party are “downright evil”.

This is likely an illustration of an attribution bias called “Motive Attribution Asymmetry”– one group’s belief that their rivals are motivated by emotions opposite to their own. To put it in simple terms: if I believe x and I believe I am a good person with good intentions, people who believe y must be evil.

Motive Attribution Asymmetry was coined in 2014, after five cross cultural studies identified a fundamental bias driving ‘seemingly intractable human conflict’. What these researchers found was that in political or ethno-religious intergroup conflict, adversaries tended to attribute aggression from their own side to ingroup love, and aggression from the opposing group to out-group hate.

A key word in the findings here is ‘intractable’. Can you actively listen, or seek to empathise, when you believe that your opponent’s beliefs and actions are grounded in hate? You’ve already, possibly unconsciously, assumed their intrinsic motivation is evil – and it’s an easy hop, skip and jump to dehumanisation from there.

In a New York Times column, Harvard Professor and Social Scientist, Arthur Brooks writes that motivation attribution asymmetry leads to contempt, which he says “is a noxious brew of anger and disgust, and not just contempt for other people’s ideas but also for other people”.

When we move from disagreeing, or even feeling contempt toward an idea, to contempt toward the whole person, we lose our humanity.

In the words of the 19th-century pessimistic philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer, contempt “is the unsullied conviction of the worthlessness of another.”

Let’s consider this in the larger scheme of human discourse.

It’s why it can be so hard for two people to hold a conversation who have deeply opposing views, because they don’t trust, or already have a subconscious bias toward, each other’s motives.

Has your dinner table ever erupted in conflict over opposing ideas? Or have you left a conversation feeling disgusted, wondering how, or if, you can continue the relationship with someone who supports something you’re vehemently against?

In these conversations, look for how you or the people around you respond to opposing ideas. Sarcasm, eye-rolling, sneering or hostile humor are all indicators of contempt according to renowned social psychologist John Gottman.

Schopenhauer also submits that if real contempt is shown, “it will be met with the most truculent hatred; for the despised person is not in a position to fight contempt with its own weapons.” Or, as we heard from the 2014 study, intractable conflict will ensue.

So what’s the panacea to motive attribution asymmetry and its toxic bedfellow of contempt? One person who has overcome her own biases is two-time Festival of Dangerous Ideas (FODI) alum Meagan Phelps-Roper.

A former born-and-raised, active member of the Westboro Baptist Church, Phelps-Roper left religious extremism behind after she encountered curiosity and a willingness to ask questions from some Twitter users. Their open-minded questions led her to ask her own, and ultimately choose a different path. Later, it was her appearance on stage at FODI 2018 that caused her to reflect on the importance of having difficult conversations in the public sphere.

Phelps-Roper’s tips for engaging with disagreement begin with a very important piece of advice: don’t assume bad intent. Assuming ill motive, she says, immediately cuts us off from accessing empathy, and prevents us from trying to understand why someone does or believes differently. It also blocks any potential for real dialogue. Her other tips include asking questions, staying calm, and articulating your own argument.

In her FODI 2024 session, The Witch Trials, alongside podcast producer Andy Mills, Phelps-Roper shared six prompts she asks herself in order to keep her own bias in check:

- Are you capable of entertaining real doubt about your beliefs? Or are you operating from a position of certainty?

- Can you articulate the evidence you would need to see in order to change your position? Or is your perspective unfalsifiable?

- Can you articulate your opponent’s perspective in a way that they recognise? Or are you straw-manning?

- Are you attacking ideas or attacking the people who hold them?

- Are you willing to cut off close relationships with people who disagree with you, particularly over small points of contention?

- Are you willing to use extraordinary means against people who disagree with you?

If, she says, the answer to any of these is yes, she knows she’s embarking on a ‘bad path’.

Perhaps next time you sit down alongside that opinionated uncle or sibling and the conversation takes a slippery turn, pause for a moment, then engage back with curiosity and the assumption of good – or even just neutral – intent.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Hope

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

People with dementia need to be heard – not bound and drugged

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Ad Hominem Fallacy

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Is masculinity fragile? On the whole, no. But things do change.

BY Karina Morgan

Karina is a communications specialist, avid hiker and volunteer primary ethics teacher, with a penchant for the written word.

A good voter’s guide to bad faith tactics

A good voter’s guide to bad faith tactics

Opinion + AnalysisPolitics + Human Rights

BY Dr Luke Zaphir 1 APR 2025

Political campaigns are mechanisms of persuasion – they aim to convince you to give them your vote.

However, they often use underhanded and bad faith tactics – not because they’re sneaky (though they can be) but because humans don’t naturally process and interpret information rationally.

This isn’t usually bad news for us – by thinking more quickly and reactively, we’re able to identify threats and safety immediately. But when it comes to elections, thinking logically is a different beast altogether. We have to slow down our thoughts, order information, make connections between ideas, discern truth from lies.

Political messaging relies on us using our simple thinking habits rather than the more rational process. Mean-spiritedness, name-calling, and catch-phrases are all tactics used to make us unconsciously lean towards or against voting for someone. Some strategies are deliberately designed to put us into specific emotional states – like anger or fear – to coax us into agreeing with the politician.

It’s more important now than ever that we recognise the tactics and strategies used so we can avoid being reactive and non-deliberative when voting. By slowing down our thinking – being more rational, and processing our emotions after we’ve examined a political message, we can come to the best possible decision come election time.

Here are some tactics that are often used, and tools that can help us combat them:

Branding and slogans

Slogans – especially catchy rhyming ones – make political messages easy and fast to understand. “Back on track” is being used by the Liberal Party in Australia this year, with “Building Australia’s Future” as the Labor party’s mantra. You might have heard an assortment of even simpler brands like “woke”, “groomer”, “degeneracy” or “traditional”.

These phrases are meant to be emotionally evocative and more importantly, be easily repeated. When scrolling social media, it’s far more likely that a person will absorb this idea unconsciously and feel a certain way. “Building Australia’s Future” evokes a sense of optimism in the audience. Similarly, “Australia Back on track” has an embedded sense of hope but also includes a slight sense of unease about the current system. Anxiety guides the thought – and it’s more likely that we won’t be thinking too deeply about which policies we agree with or what where we’d like the country to go.

At a minimum, branding and slogans don’t allow for nuanced conversations. Engagement goes up, but deep understanding goes down.

What you can do: Be mindful of your emotions

All political advertising is designed to make us feel a certain way. After reading or watching the content, check in with yourself. What are you feeling right now? Optimistic? Slightly anxious? Outraged? Recognise that the ad meant to evoke that and influence you.

Avoid taking the emotional bait. Try to avoid reacting and instead take a moment to consider why they’ve chosen that feeling for the ad. Positive emotions aim to build loyalty and trust, whereas negative emotions create a sense of urgency and amplify the downsides. Finally stay objective – consider what it is that’s factually true about this issue.

Priming

Priming is the practice of putting people in a certain frame of mind before discussing a political issue. For example, a common and volatile topic of debate is that of transgender people in sports. We often see public outcry at how unfair it is to have transgender women competing against cisgender women – transgender athletes are seen as having unfair biological advantages at best, or are ‘pretending’ to be women at worst – all just for a win.

This topic has been primed in a certain way – primed to lean on preexisting ideas of fairness and gender.

It’s reasonable to have strong feelings about what makes sports fair after all. But how would the conversation change if it started by talking about the bullying transgender people endure just for trying to play sports? What if the discussion started with the disproportionate mental health struggles they face compared to the wider population? This priming shifts the tenor of the entire conversation.

An argument that needs priming is one that is playing on our prejudices and biases – an obvious sign of a weak and unconvincing argument. Compelling ideas don’t need to rely on this kind of tactic to be persuasive.

What you can do: Reframe your thinking

After engaging with the material, take a moment to reflect. Are you being led to support a specific side? Are you valuing one piece of evidence more than another?

Avoid jumping to conclusions based on the presented viewpoint. Instead, ask yourself why the content is framing certain ideas favourably. Balanced content usually considers multiple perspectives while biased content steers you toward one.

Framing

Framing shapes how we see an issue, often making it seem overly simple or emotional. For example, the term ‘pro-life’ frames opponents as ‘anti-life,’ which is misleading. Abortion as a topic is filled with complex ideas around bodily autonomy, medical privacy, and beliefs around when life begins – framing this issue as simple removes all ability to explore it with any nuance.

Another way framing can be harmful is that it encourages feeling, rather than thinking. Fear of immigrants is a classic tactic used for hundreds if not thousands of years, and Australian politics is no different. Immigrants are depicted as a threat to jobs, culture and safety. The fear frame is meant to get people feeling like there’s an imminent danger when facts and common sense say otherwise.

What you can do: Deepen your thinking about the world and understanding of yourself

Consider whether you’re being encouraged to examine the complexities of an issue or merely agree with a simplified viewpoint. Recognise that interactions, such as liking or sharing or responding to a post, will amplify the original idea – even if you disagree with it.

Avoid simply nodding along. Instead, take the time to reflect on the broader implications, possible outcomes, and alternative perspectives. Be open to being wrong and ready to hear differing opinions.

Also consider whether you’re being pressured to conform to a single group, person, or ideology. “Us vs them” narratives rarely reflect our complexities as people or societies. Messages that simplify to that degree focus on our differences, rather than attending to our common problems.

No identity or belief system is infallible or beyond criticism – our own beliefs are our biggest blind spot. Embrace the diversity within yourself and others, acknowledging that multiple perspectives can coexist and contribute to a richer understanding of the world.

Image: Martin Berry / Alamy Stock Photo

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

Is constitutional change what Australia’s First People need?

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

Trump and the failure of the Grand Bargain

Explainer

Politics + Human Rights

Ethics Explainer: Anarchy

Opinion + Analysis

Climate + Environment, Politics + Human Rights

Australia Day: Change the date? Change the nation

BY Dr Luke Zaphir

Luke is a researcher for the University of Queensland's Critical Thinking Project. He completed a PhD in philosophy in 2017, writing about non-electoral alternatives to democracy. Democracy without elections is a difficult goal to achieve though, requiring a much greater level of education from citizens and more deliberate forms of engagement. Thus he's also a practicing high school teacher in Queensland, where he teaches critical thinking and philosophy.

An angry electorate

I recently attended a gathering of people who engage with a remarkably diverse range of Australians.

Members of this group are directly connected with both the wealthiest and poorest in society. Some are city folk; others firmly grounded in the lives of rural, regional and remote communities. They told of the experience and attitudes of people whose circumstances vary considerably – from the most secure to the most precarious in the land.

Remarkably, when asked about the ‘mood’ of the electorate, all told a similar story. Across all demographics, people are disappointed, frustrated and angry. Some of these feelings understandably arise out of the clear failure of our society to meet even the most basic needs of its members. For example, we were told of a regional city, in New South Wales, where 26% of the community are now experiencing food insecurity. That is, a quarter of the population experiencing days where they do not know if they will be able to secure the food they or their family need. We heard of young people – some from relatively affluent families – who doubt that they will ever be able to afford the ‘Australian Dream’ of a home of their own. For some, if not for all, the word ‘crisis’ is an entirely apt description of what far too many people are experiencing.

However, what this cannot explain is the anger felt by even the most affluent.

The seat of the fire is located in a shared (and growing) sense that too many of our politicians and media are ‘fiddling while Rome burns’. Instead of being wholeheartedly focused on the interests of the community, our leading politicians are perceived as being engaged in the trivial game of political-point-scoring, in pursuit of power for its own sake – rather than as a means for realising a larger vision of what could or should be.

This kind of anger is hard to extinguish. There comes a point when even a good policy is discounted by a public that cynically questions the politicians’ motives. This cynicism is exacerbated by a style of politics that is becoming increasingly partisan. One might reasonably doubt that there was ever a ‘golden age’ of politics in Australia. But the decline in widespread public participation in political parties has meant that a relatively small number of factionalised ideologues can take control of a major party. The way the numbers work, they can push increasingly extreme views – unhindered by the ‘sensible middle’ that used to prevail when major political parties really were ‘broad churches’.

I mention all of this because, as we know all too well in Australia, a single ember can easily give rise to a destructive conflagration.

My sense is that the Australian political landscape is bone dry, with the electoral tinder piling up. In this angry environment, one can foresee a moment of nihilistic abandonment; when the idea of ‘burning it all to the ground’ just might catch on.

This we have seen happen in other parts of the world. If only mainstream America had listened attentively to the complaints of people who genuinely felt abandoned by those occupying ‘the swamp’ in Washington DC. Ignored or labelled ‘deplorables’, President Trump became their ‘agent of destruction’. The same forces were at work in the Brexit referendum. A number of those who voted for leaving the EU doubted that their lives would improve. Instead, they took comfort in the fact that those who looked down on them would be worse off.

Our political elite must accept their fair share of responsibility for the increasing level of anger directed at the ‘system-as-a-whole’. However, as citizens of a democracy, we also have a critical role to play. While we might not be able to control our external environment, we are responsible for our response. Knowing what can happen when anger is let loose at its destructive worse, we need to exercise careful restraint and not enflame the situation.

Australian democracy has many faults. And there are plenty of people who have borne the burden of its failures. But it has also helped to sustain one of the world’s better societies. My hope is that politicians – irrespective of party or political persuasion – might take a moment to look beyond party or personal self-interest to ask if their conduct is strengthening or weakening our democracy in the eyes of the electorate. Democratic institutions are not the property of any government, party or faction. They belong to and are exclusively to be used for the benefit of the people. Those who tarnish or degrade those institutions are guilty of public vandalism. So, let’s hold those who do this individually responsible rather than abandon faith in our entire system of democratic governance. And if it happens to be the case that the problem is the system (as may be the case), then let’s work together to decide what would be better – and then build towards that positive outcome.

In turn, we need to dampen down the fires of anger – not be blinded by the smoke of our righteous indignation – no matter how justified it might be. We need a clear vision of what we think makes for a good society. And then we need to elect those who would help us to build rather than tear down.

BY Simon Longstaff

Simon Longstaff began his working life on Groote Eylandt in the Northern Territory of Australia. He is proud of his kinship ties to the Anindilyakwa people. After a period studying law in Sydney and teaching in Tasmania, he pursued postgraduate studies as a Member of Magdalene College, Cambridge. In 1991, Simon commenced his work as the first Executive Director of The Ethics Centre. In 2013, he was made an officer of the Order of Australia (AO) for “distinguished service to the community through the promotion of ethical standards in governance and business, to improving corporate responsibility, and to philosophy.” Simon is an Adjunct Professor of the Australian Graduate School of Management at UNSW, a Fellow of CPA Australia, the Royal Society of NSW and the Australian Risk Policy Institute.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

Australia’s ethical obligations in Afghanistan

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Society + Culture

Respect for persons lost in proposed legislation

Big thinker

Politics + Human Rights, Science + Technology

Big Thinker: Francesca Minerva

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Science + Technology

Is it right to edit the genes of an unborn child?

What does Adolescence tell us about identity?

What does Adolescence tell us about identity?

Opinion + AnalysisSociety + Culture

BY Joseph Earp 27 MAR 2025

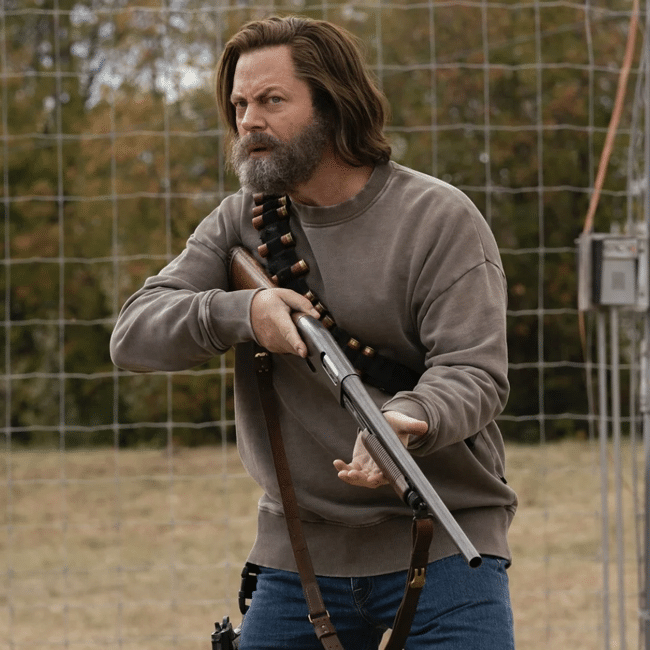

Adolescence, the exemplary new Netflix series that has become immediate water cooler conversation fodder, is built around a filmmaking decision that might have, in lesser hands, felt like a gimmick. Each of the four episodes of the show are filmed in one continuous, unbroken take.

Here, the decision is not just an inspiring feat of filmmaking verve. It also has a thematic point. Adolescence concerns the murder of a female high school student – the accused is 13-year-old Jamie Miller (Owen Cooper). The show carefully explores the fallout of that violent crime, in particular, what it churns up in the heart of Jamie’s father, Eddie (Stephen Graham, also the show’s co-creator).

The themes of Adolescence are laid out early, and clearly: misogyny; the anger in the heart of teenage boys; and, in particular, the forces that influence adolescents. These themes coalesce in one of the major questions of the show: who shapes the identity of young people, and, pressingly, young men? Is it their parents? The world around them? Or, most worryingly of all, the bad ethical actors who have made their careers through stoking the fires of hatred?

That unblinking, never-cutting camera allows us to explore this question with striking clarity. The camera never looks away. So painfully and shockingly, neither can we.

Who makes our children?

Unlike many other works of art based around crime and murder, Adolescence is not, particularly, a whodunit. It is more like a whydunit. We do have questions early on as to whether Jamie actually committed the crime of which he has been accused, but this is not the focus of the show. Instead, the mystery is a broader, harder, more probing one: why do young men commit acts of violence against women? More specifically, who formed Jamie’s ethical identity?

Eddie, Jamie’s father, seems to worry that it might be him. He spends the show wracked by guilt, confronted with the knowledge of his son’s suspected crime, and terrified that he did not do enough to stop him from walking down a very dark path. But is he solely to blame? The beauty of Adolescence is that it instead leaves those “responsible” for the dark parts of Jamie’s personality nebulous.

In his groundbreaking work, Sources of the Self, philosopher Charles Taylor provides an answer – albeit a worrying one. He argues that identity is formed by a collective. In his view, human beings are defined and constructed through their relationship with others – we become who we are, by virtue of who we interact with. On this view, parents are of course responsible for the shaping of their children’s ethical makeup – but they’re not solely responsible.

And they’re particularly not responsible when adolescence hits. Every parent to teenagers knows that rebellion against the older guard is inevitable – and parents are often the last people that children will confer with. That, according to Taylor, leaves children susceptible to other formative ethical forces – and in the case of Jamie, those are the bad misogynist actors that he is surrounded by, from his schoolmates, to the ever-pressing threat of online radicalisation.

The spectre of the other

Taylor’s view is particularly troubling when combined with the writings of another philosopher, Giorgio Agamben. In his major work, Homo Sacer: Sovereign Power and Bare Life, Agamben argues that ethical identities are especially formed by the rules of inclusion and exclusion. People become who they are by deciding who they are not, forming an in and an out-group that gives them a sense of security in their own personhood.

In Adolescence, it’s exactly that exclusionary nature that seems to lead Jamie down his dark path. His world, like the world of far too many teenage boys, is defined by strict and dangerous binaries: boys versus girls, winners versus losers. His worldview, when we get to hear it, seems defined by hatred for what is different, and a desperate clinging to that, which he sees as the same as himself. When such strict battle lines are drawn, violence is a natural endpoint.

What then do we do to attempt to get our teenage boys back on the right path? Away from violence, hatred, and exclusion? Adolescence, bravely, doesn’t offer a solution. In fact, that’s exactly what Taylor and Agamben show us – that one simple, pat, generic solution doesn’t have the power to change anything.

After all, if we take the work of those philosophers to be true, then we see the entire social environment as constitutive of identity. That means parents. It means friends. It means the entertainment young men consume. It means what they hear in the playground.

Our gaze must significantly broaden – and we must not consider the likes of Jamie to be an outlier. Instead, we must see him as a product of an entire social system.

When, in the final episode of Adolescence, Eddie asks his wife, “shouldn’t we have done better?”, the initial impulse is to assume he means the two of them. The better read is that he means all of us.

BY Joseph Earp

Joseph Earp is a poet, journalist and philosophy student. He is currently undertaking his PhD at the University of Sydney, studying the work of David Hume.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture

Read before you think: 10 dangerous books for FODI22

Big thinker

Relationships, Society + Culture

Big Thinker: Simone de Beauvoir

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Society + Culture

On truth, controversy and the profession of journalism

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

How can you love someone you don’t know? ‘Swarm’ and the price of obsession

Thought experiment: The original position

Thought experiment: The original position

ExplainerSociety + CulturePolitics + Human Rights

BY The Ethics Centre 20 MAR 2025

If you were tasked with remaking society from scratch, how would you decide on the rules that should govern it?

This is the starting point of an influential thought experiment posed by the American 20th century political philosopher, John Rawls, that was intended to help us think about what a just society would look like.

Imagine you are at the very first gathering of people looking to create a society together. Rawls called this hypothetical gathering the “original position”. However, you also sit behind what Rawls called a “veil of ignorance”, so you have no idea who you will be in your society. This means you don’t know whether you will be rich, poor, male, female, able, disabled, religious, atheist, or even what your own idea of a good life looks like.

Rawls argued that these people in the original position, sitting behind a veil of ignorance, would be able to come up with a fair set of rules to run society because they would be truly impartial. And even though it’s impossible for anyone to actually “forget” who they are, the thought experiment has proven to be a highly influential tool for thinking about what a truly fair society might entail.

Social contract

Rawls’ thought experiment harkens back to a long philosophical tradition of thinking about how society – and the rules that govern it – emerged, and how they might be ethically justified. Centuries ago, thinkers like Thomas Hobbes, Jean-Jacques Rousseau and John Lock speculated that in the deep past, there were no societies as we understand them today. Instead, people lived in an anarchic “state of nature,” where each individual was governed only by their self-interest.

However, as people came together to cooperate for mutual benefit, they also got into destructive conflicts as their interests inevitably clashed. Hobbes painted a bleak picture of the state of nature as a “war of all against all” that persisted until people agreed to enter into a kind of “social contract,” where each person gives up some of their freedoms – such as the freedom to harm others – as long as everyone else in the contract does the same.

Hobbes argued that this would involve everyone outsourcing the rules of society to a monarch with absolute power – an idea that many more modern thinkers found to be unacceptably authoritarian. Locke, on the other hand, saw the social contract as a way to decide if a government had legitimacy. He argued that a government only has legitimacy if the people it governs could hypothetically come together to agree on how it’s run. This helped establish the basis of modern liberal democracy.

Rawls wanted to take the idea of a social contract further. He asked what kinds of rules people might come up with if they sat down in the original position with their peers and decided on them together.

Two principles

Rawls argued that two principles would emerge from the original position. The first principle is that each person in the society would have an equal right to the most expansive system of basic freedoms that are compatible with similar freedoms for everyone else. He believed these included things like political freedom, freedom of speech and assembly, freedom of thought, the right to own property and freedom from arbitrary arrest.

The second principle, which he called the “difference principle”, referred to how power and wealth should be distributed in the society. He argued that everyone should have equal opportunity to hold positions of authority and power, and that wealth should be distributed in a way that benefits the least advantaged members of society.

This means there can be inequality, and some people can be vastly more wealthy than others, but only if that inequality benefits those with the least wealth and power. So a world where everyone has $100 is not as just as a world where some people have $10,000, but the poorest have at least $101.

Since Rawls published his idea of the original position in A Theory of Justice in 1972, it has sparked tremendous discussion and debate among philosophers and political theorists, and helped inform how we think about liberal society. To this day, Rawls’ idea of the original position is a useful tool to think about what kinds of rules ought to govern society.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture

10 films to make you highbrow this summer

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

CoronaVirus reveals our sinophobic underbelly

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

A good voter’s guide to bad faith tactics

Explainer

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Autonomy

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Billionaires and the politics of envy

Billionaires and the politics of envy

Opinion + AnalysisPolitics + Human Rights

BY Carl Rhodes 13 MAR 2025

Billionaires are an ultra-elite social class whose numbers are growing alongside their obscene wealth while others struggle, suffer or even die. They represent a scourge of economic inequality, but how do they get away with being viewed as a ‘force for good’?

In 1974, a year before she became leader of Britain’s Conservative Party and five years before being elected prime minister, Margaret Thatcher stated that she rejected ‘vehemently the politics of envy, the incitement of people to regard all success as if it were something discreditable, gained only by taking selfish advantage of others’. In 1983 United States President Ronald Reagan echoed the same sentiment. ‘If we’re to rebuild our beloved land, then those who practice the politics of envy, … must rise above their rancour and join us in a new dialog … and make America great again.’.

As the neoliberal era was beginning to take shape, Thatcher and Reagan told the world that if economic progress was the goal, then inequality was necessary. The liberated rich would lead the world, and everyone would benefit in the long run, so the story went. As national economies the world over embraced economic deregulation, corporate tax cuts and the virtual end of trade protectionism, a newly globalised world economy emerged, intoxicated by the promise of economic freedom and shared prosperity. The experiment failed. Neoliberalism has led to widening economic inequality and the emergence of a conspicuous billionaire class.

Ideology is much stronger than facts and reducing calls for equality to a politics of envy remains part of regressive conservative politics to this day. In 2022, at the depth of the COVID-19 pandemic, many of Australia’s largest corporations were under attack for taking government handouts to support the payment of wages to their employees, while simultaneously giving lavish bonuses to their executives. Former Prime Minister Scott Morrison waved off the scandal. ‘I’m not into the politics of envy,’ he said. Even Labor Prime Ministers are not immune. When people complained about Anthony Albanese buying a $4.2 million home in 2024, they too were accused of the politics of envy.

Dismissing one’s political adversaries by accusing them of a politics of envy comes hand in hand with the moralisation of unequal wealth and the justification of economic inequality. This is a topsy-turvy world where demands for justice are dismissed as selfishly motivated, bred out of unchecked absorption by the deadly sin of envy. The flip side of the politics of envy is the idea that the wealthy should be revered rather than begrudged. By this account, being rich means being a hard-working ‘winner’ whom others should respect and admire, exponentially so for billionaires. Billionaires are aspirational role models for many people, presented as benevolent and effective – good, even.

The politics of envy reflects a political conviction that economic inequality is both economically necessary and the fair outcome of a meritocratic society.

If you are not rich it is your fault – you are a loser. Fortunately, public awareness and political activism against billionaire excess and calls to action to address inequality are growing. Economist Thomas Piketty, whose extensive and renowned studies on inequality put him in a position to understand the true devastation it can cause, remains inspiringly optimistic. ‘History teaches us that elites fight to maintain extreme inequality, but in the end, there is a long-run movement toward more equality, at least since the end of the 18th century, and it will continue,’ he argues. Such hopefulness, combined with a faith in the possibility of progress, can animate a political will to change things for the benefit of the vast majority of the world’s citizens. No seemingly entrenched and immovable state of injustice is fixed as if history was standing still.

What is decried as the politics of envy is, in fact, a call for economic justice. The call was seen in activist movements such as Occupy Wall Street in 2011. It is around today everywhere from the ‘tax the rich’ movement, to the so-called ‘eat the rich’ genre of movies that explore themes of capitalism and inequality. New demands for equality can be found in the resurgent socialism of Bernie Sanders in the United States and Jeremy Corbyn in the United Kingdom. What is clear is that in recent years there has been a growing discontent with the wealth and power controlled by the world’s most rich.

Acclaimed author Ursula LeGuin stated, when being awarded the National Book Foundation Medal for Distinguished Contribution to American Letters in 2014, that: ‘We live in capitalism. Its power seems inescapable. So did the divine right of kings. Any human power can be resisted and changed by human beings.’ As a footnote to LeGuin’s insight, it can be added that under contemporary capitalism, there is a profound risk returning to something akin to the divine right of kings, only now those kings are billionaires. All the more reason to resist. All the more reason to demand justice. All the more reason for change.

This is an edited extract from: Carl Rhodes (2025) Stinking Rich: The Four Myths of the Good Billionaire, Bristol University Press.

BY Carl Rhodes

Carl Rhodes is Dean and Professor of Organization Studies at the University of Technology Sydney Business School. Carl writes about the ethical and democratic dimensions of business and work. Carl’s most recent books are Woke Capitalism: How Corporate Morality is Sabotaging Democracy (Bristol University Press, 2022), Organizing Corporeal Ethics (Routledge, 2022, with Alison Pullen) and Disturbing Business Ethics (Routledge, 2020).

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture, Politics + Human Rights

Pleasure without justice: Why we need to reimagine the good life

Opinion + Analysis

Climate + Environment, Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

A burning question about the bushfires

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Assisted dying: 5 things to think about

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture, Climate + Environment, Politics + Human Rights

Why you should change your habits for animals this year

Ask an ethicist: Am I falling behind in life “milestones”?

Ask an ethicist: Am I falling behind in life “milestones”?

Opinion + AnalysisSociety + Culture

BY Cris Parker 11 MAR 2025

Over the past couple of years I’ve noticed all my friends are either getting married, buying houses or starting families. I haven’t achieved any of these major life “milestones” yet and am worried I won’t any time soon. Should I be concerned I’m not keeping up?

Big life milestones – getting married, having kids, or buying houses are often seen as markers for success and there is no right way to go about them, if at all. It is a deeply personal choice influenced by individual values and principles, goals, and the society we live in.

In Western societies, there is often an unspoken expectation that by your mid-30s, you should have ticked off a checklist: education, marriage, kids, and a mortgage. But where do these expectations come from? And do they really reflect what we want for ourselves?

It’s easy to feel like you are falling behind when everyone around you seems to be hitting milestones at a kicking pace. Social media does not help – our feeds are filled with engagement announcements, baby photos, and housewarming parties, making it seem like these achievements are happening all the time. These “deadlines” are often arbitrary, and the pressure to achieve them can often come from unidentifiable places.

Beyond social media, family, culture, and tradition also play a significant role in shaping our expectations. Parents and grandparents often see marriage, kids, and home ownership as the natural and successful progression into adulthood. Friends, too, may unintentionally add pressure by assuming you’ll follow the same path they did – moving to the suburbs, starting a family, or planning a big wedding. These pressures can subtly reinforce the idea that there is a “right” path to follow.

Traditions can be comforting, offering a sense of structure and belonging. But they can also feel restrictive if they don’t align with your personal values. The key is to recognise that while traditions may have worked in the past, they don’t have to dictate your choices today.

Adding the external pressure, biases also shape how we interpret success and progress with the frequency of seeing these milestones online, reinforcing an availability bias where we may overestimate the prevalence of these “achievements”. False consensus bias can also make us assume that the choices of our friends represent a universal societal norm.

Let’s remember these milestones are not set in stone and differ from generation to generation. Societal norms are developed from the economic and social conditions of the time. A generation or two ago, settling down young was the norm. After World War II, single-income households could afford homes, birth rates were high, and religious beliefs strongly influenced family life.

But the world today is very different. Housing prices have skyrocketed, wages haven’t kept up, and societal values have shifted which mean these traditional milestones are no longer as achievable or even desirable as they once were.

The shift away from traditional milestones reflects broader changes in societal values. Within younger generations today, there is greater emphasis on personal fulfilment, career development, and experiences such as travel and education. These evolving values redefine what we think of as success and happiness. The focus on individual agency allows people to make choices that align with their personal goals and values rather than societal pressures.

The decision to have children has become increasingly complex. Many people grapple with the ethical implications of bringing children into a world facing environmental crises and geopolitical unrest. Add financial pressures and a growing lack of trust in long-term stability, and the decision to become a parent requires careful consideration and a strong alignment with personal values. It underscores the importance of being authentic and accountable for our decisions, as these choices reflect not just our desires but our hopes and concerns for the future.

At the end of the day, what really matters is whether your choices align with your own values and aspirations. Ethically, it’s important to question whether you are pursuing these milestones because they genuinely excite you, or because you feel like you ‘should’? There’s no right or wrong answer – just the one that feels right for you.

Success isn’t about checking off a list of expectations – it’s about living in a way that is aligned with what makes you happy and fulfilled. Whether that includes marriage, kids, homeownership, or something entirely different, the most important thing is that it’s your choice – not society’s.

BY Cris Parker

Cris Parker is the former Head of The Ethics Alliance and a Director of the Banking and Finance Oath at The Ethics Centre.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Society + Culture

Banking royal commission: The world of loopholes has ended

Big thinker

Relationships, Society + Culture

9 LGBTQIA+ big thinkers you should know about

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture, Business + Leadership, Health + Wellbeing

Make an impact, or earn money? The ethics of the graduate job

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

In Review: The Festival of Dangerous Ideas 2018

Freedom of expression, the art of...

Freedom of expression, the art of…

Opinion + AnalysisSociety + CulturePolitics + Human Rights

BY Brook Garru Andrew 5 MAR 2025

The creative mind is a vast universe of ideas, emotions, and experiences expressed through music, painting, poetry, and beholden to the forces of politics, history, and memory.

Creation is never neutral; it is shaped by ethics, challenged by censorship, and navigates evolving taboos. Artists share an impulse to express, question, and challenge shifting realities. Their work requires not only careful creation but also thoughtful engagement from society.

Martinican writer and philosopher Édouard Glissant explored identity as fluid, shaped by culture, history, and human connections. He introduced concepts like creolisation – the blending and evolution of cultures – and relation, which emphasises deep interconnectedness between all things. Glissant argued that true understanding does not require full transparency; rather, opacity allows for complexity and respect. His ideas remain essential in a time when artistic expression faces increasing scrutiny.

Art that challenges dominant narratives has historically faced repression. Artists have been censored, exiled, or condemned for confronting power structures. Dmitri Shostakovich was denounced by Stalin’s Soviet regime, Fela Kuti was imprisoned for his politically charged lyrics, and Buffy Sainte-Marie was reportedly blacklisted for her activism against war and colonial oppression. These cases highlight the ongoing tension between creative expression and societal control.

The questions remain: how can we create spaces for open debate that accommodate differing perspectives without deepening divisions? Can artistic expression be challenged and discussed without escalating polarisation? These ethical considerations are central to the evolving relationship between art, power, politics, and public discourse. Glissant’s vision of the world as a relational space offers a framework for understanding these tensions. We will not always agree and accepting difference is an opportunity for growth, to find ways to work together and create the world we want to be in.

Australia, despite its colonial past which it is still coming to terms with, has the potential to embrace this openness. It has long been a refuge for those fleeing war and persecution, and its commitment to artistic independence could foster healing and truth telling. This was achieved in 2024, when Archie Moore transformed the Australian Pavilion at the Venice Biennale with kith and kin, a genealogical mural that created a space of memorial to address Aboriginal Deaths in Custody. His work compelled viewers to confront colonial violence and won the prestigious Golden Lion for Best National Participation.

Our ability to embrace openness; however, is continually tested. In February 2025, Creative Australia selected Khaled Sabsabi to represent the country at the 2026 Venice Biennale. However, his appointment was quickly rescinded due to controversy over some of his past works. Amid heightened tensions – especially following both recent antisemitic and Islamophobic incidents in Australia – these early works ignited debate over the appropriateness of his selection to represent Australia.

Born in Tripoli, Lebanon, in 1965, Sabsabi migrated to Australia in 1978 to escape the Lebanese civil war. Now a leading multimedia artist, his work explores identity, conflict, and cultural representation. He does not seek provocation for its own sake but, in his words, “humanity and commonality” in a fractured world. The decision by Creative Australia and the unwillingness to consult with the artistic team will have consequences yet to be revealed.

Sabsabi’s removal was not solely about his art but also about a reluctance to engage with the complexity of his personal and artistic journey. The debate was quickly reduced to sensationalism and those seeking political gain. As of February 2025, major conflicts persist internationally including in Myanmar, Israel-Palestine, Sudan, Ukraine, Ethiopia, Afghanistan, Pakistan, and West Papua. These crises underscore the responsibility of countries like Australia to uphold international law, human rights protection, and open dialogue. Yet many in Australia today are hesitant – or even fearful – to publicly express their views on these crises, particularly in writing.

In this global landscape, artists play a vital role in documenting realities, challenging dominant narratives, and fostering open dialogue. Yet, such actions are becoming increasingly difficult. Perspectives are scrutinised, and the line between advocacy and bias is often blurred. Artists, journalists, and commentators must navigate these complexities with integrity, acknowledging multiple truths while resisting ideological pressures.

The Venice Biennale, one of the world’s most prestigious art exhibitions, has long been a site where these tensions surface. The Giardini della Biennale, its historic heart, houses 29 national pavilions, mostly belonging to First World nations. Established in 1895, the Biennale reflects global cultural and political hierarchies. Wealthy Western countries dominate, while many nations lack permanent pavilions and must rent temporary spaces. This structural imbalance highlights broader geopolitical tensions, where artistic representation remains deeply entangled with power, privilege, and exclusion.

When an artist like Sabsabi is removed from such a space, it is not just censorship – it is a lack of engagement with the world as it truly is: complex, layered, and shaped by histories of displacement and resilience. At a time when war, genocide, colonial legacies, and cultural erasure remain pressing concerns, his exclusion is a loss not only for Australia but for the ideals of artistic dialogue and exchange the Biennale is meant to uphold.

This moment underscores the need for genuine artistic and cultural engagement in a world in distress. Art is not just about provocation; it fosters dialogue and solidarity. While opinions on Sabsabi’s work may differ, his artwork is an expression of his lived experience. His exploration of difficult truths and diverse viewpoints underscores that nothing remains static.

The role of the artist is to show us parts of the world that we may not, or refuse to, see. It does not mean that we must agree with their viewpoint.

The broader concern is what this decision reveals about Australian values, how we as individuals and institutions engage with art, and the nation’s commitment to artistic freedom. It raises questions about transparency and decision-making in cultural institutions, but also how cultural dialogue is shaped by media, journalists, and politicians to inform public opinion.

As Australia navigates this complex moment, the challenge lies in balancing artistic freedom with public accountability. The outcome of this controversy may influence future cultural policies, shaping the country’s approach to representing its artists and how art should be viewed. Whether the withdrawal is seen as necessary caution or a loss to Australian artistic identity remains an open question.

In a world marked by ideological clashes, religious wars, and present and historical trauma, there are no absolute winners, with many caught in cycles of division. Growth begins with listening and as Glissant teaches, identity and expression cannot be confined to binaries. Complexity and contradiction invite deeper understanding. A just society must make room for difficult conversations and challenging artistic expressions.

Image: Khaled Sabsabi portrait, Unseen, 2023, image courtesy the artist and Mosman Art Gallery, © Mosman Art Gallery. Photograph: Cassandra Hannagan

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture

‘Vice’ movie is a wake up call for democracy

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Society + Culture

The Ethics Institute: Helping Australia realise its full potential

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

Bring back the anti-hero: The strange case of depiction and endorsement

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights