Big Thinker: Buddha

Gautama Buddha lived during the 5th century BCE and was the founder of the Buddhist religion. He also developed a rich philosophical system of thought that challenged notions of permanence and personal identity.

Buddhism is typically considered a religion but it also has a strong philosophical foundation and has inspired a rich tradition of philosophical inquiry, especially in India and China, and, increasingly, Western countries.

Buddhism emerged from the teachings of Siddhartha Gautama, an Indian prince who turned his back on a life of leisure and opulence. Instead, he sought to understand the causes of suffering and how we might be able to be liberated from it.

Coincidentally, Gautama Buddha lived around the 5th Century BCE, which is at a similar time to two other great philosophers in different corners of the world – Socrates in Ancient Greece and Confucius in China – both of whom sparked their own major philosophical traditions.

Desire, happiness and suffering

Like many philosophers – from Aristotle to Peter Singer – one might say the Buddha was interested in how to live a good life. The starting point of his teachings is that life is suffering, which sounds like a pessimistic start, but he was just reminding us none of us can escape things like illness, death, loss, or these days, doing our tax returns.

Buddha went on to explain suffering is not random or uncaused. In fact, he argued if we can come to understand the causes of suffering, then we can do something about it. We can even become liberated from suffering and achieve nirvana, which is a state of pure enlightenment.

Many philosophers believe this teaching is just as relevant today as it was over 2,000 years ago. We’re told today that we ought to be happy, and that happiness comes from being able to satisfy our desires. Our entire economy is predicated on this idea. So we work hard, earn money, get stressed, buy more stuff, yet many of us can’t seem to find deeper satisfaction.

It turns out that no matter what desires we satisfy, there are more desires that crop up to take their place. And there are some desires that never go away, like the desire for status or wealth, and some desires that can never be satisfied, like when we experience unrequited love. And when we can’t satisfy our desires, we experience suffering.

The Buddha said this is because we have our theory of happiness backwards. Happiness doesn’t come from satisfying ever more desires – it comes from reducing our desires so there are fewer that need to be satisfied. It’s only when we desire nothing and we can just be that we are truly free from suffering.

Thus the Buddha argues our suffering is not caused by the whims of an indifferent world outside of our control. Rather, the cause of suffering is within our own minds. If we can change our minds, we can find liberation from suffering. This led him to develop a theory of our minds and how we perceive reality.

Permanence

He said that one of the fundamental mistakes in the way we think about the world is to believe in the permanence of things. We assume (or desire) that things will last forever, whether that be our youth, our possessions or our relationships with loved ones, and we become attached to them.

So when they inevitably erode, decay or disappear – we grow old, our possessions wear out, our loved ones move on – we suffer. But this suffering is only because we failed to realise that nothing is permanent, that all things are in flux, and if we can come to enjoy things without being attached to them, then we would suffer less.

Tibetan Buddhist monks have a ritual where they spend weeks painstakingly creating incredibly detailed and beautiful mandalas made out of coloured sand. Then, once they’re finished, they ritualistically sweep the sand away, destroying the mandala, and drop the collected sand into a river to flow back into the world, representing their embrace of impermanence.

The self

Another core philosophical insight from Buddhism was to question our sense of self. It’s natural to believe there is something at the core of our being that is unchanging, whether that be our soul, mind or personality.

But the Buddha noted when you try to pin down what that permanent aspect of ourselves is, you find there’s nothing there, just a stream of impressions, thoughts and feelings. So our sense that there is a persistent self is ultimately an illusion. We are just as dynamic and impermanent as the rest of the world around us. And if we can realise this, we can release ourselves from the pretense of what we think we are and we can just be.

Interestingly, this is very similar to an observation made by the 18th century Scottish philosopher David Hume, who said when he introspected, he could never settle on the solid core to his self. Rather, his self was like a swarm of bees with no boundary and no hard centre, with each being an individual thought or experience. The Buddha would likely have enjoyed this analogy.

Meditation

One of the aspects of Buddhism that has had the most lasting impact is the practice of meditation, particularly mindful meditation. The recent mindfulness movement is based on a form of Buddhist meditation that encourages us to sit quietly and let our thoughts come and go without judgement. Essentially, we must ignore our thoughts in order to control and be free from them. Modern science has shown that this kind of meditation can reduce stress and improve our focus and mood.

Buddhism is not only the fourth largest religion in the world with over 500 million adherents today, and third largest in Australia, but it continues to be a rich vein of philosophical inquiry.

Western philosophy was rather slow to take Buddhism seriously, but there are now many Western philosophers who are engaging with Buddhist ideas about reality, knowledge, the mind, the self and ethics.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Big thinker

Health + Wellbeing, Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Big Thinker: Judith Butler

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

A critical thinker’s guide to voting

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

How to respectfully disagree

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships

What makes a business honest and trustworthy?

BY Dr Tim Dean

Dr Tim Dean is Philosopher in Residence at The Ethics Centre and author of How We Became Human: And Why We Need to Change.

People with dementia need to be heard – not bound and drugged

People with dementia need to be heard – not bound and drugged

Opinion + AnalysisHealth + WellbeingPolitics + Human RightsRelationships

BY Kate Prendergast 24 APR 2019

It began in Oakden. Or, it began with the implosion of one of the most monstrously run aged care facilities in Australia, as tales of abuse and neglect finally came to light.

That was May 2017. Two years on, we are in the midst of the first Royal Commission into Aged Care Quality and Safety, announced following a recommendation by the Scott Morrison government.

The first hearings began this year in Oakland’s city of Adelaide. They have seen countless brave witnesses come forward to share their experiences of what it’s like to live within the aged care system or see a loved one deteriorate or die – sometimes peacefully, sometimes painfully – within it.

In May, the third hearing round will take place in Sydney. This round will hear from people in residential aged care, with a focus on people living with dementia – who make up over 50 percent of residents in these facilities.

With our burgeoning ageing population, the number of people being diagnosed with dementia is expected to increase to 318 people per day by 2025 and more than 650 people by 2056.

Encompassing a range of different illnesses, including Alzheimer’s disease, vascular dementia and Lewy body disease, its symptoms are particularly cruel, dissolving intellect, memory and identity. In essence, dementia describes the gradual estrangement of a person from themselves – and from everyone who knew them.

It is one of the most prevalent health problems affecting developed nations today – and one of the most feared. Contrary to widespread belief, one in 15 sufferers are in their thirties, forties and fifties.

Physical restraints

How do you manage these incurable conditions? How can you humanely care for the remnants of a person who becomes more and more unrecognisable?

One thing the Royal Commission has made clear: you don’t do it by defaulting to dehumanising mechanisms of restraint.

Unlike in the UK or the US, there are currently no regulations around use of restraints in aged care facilities. It is commonly resorted to by aged care workers if a patient displays physical aggression, or is a danger to themselves or others.

Yet it is also used in order to manage patients perceived as unruly in chronically understaffed facilities, when the risk of leaving them unsupervised is seen to be greater than the cost of depriving them their free movement and self-esteem. The problem of how to minimise harm in these conditions is an ongoing and high-pressure dilemma for staff.

Readers may remember the distressing footage from January’s 7.30 Report, in which dementia patients were seen sedated and strapped to chairs. One of them was the 72-year-old Terry Reeves. Following acts of aggression towards a male nurse, he was restrained for a total of 14 hours in a single day. His wife, however, had authorised that her husband be restrained with a lap belt if he was “a danger to himself or others”.

Maree McCabe, director of Dementia Australia, is vocal about why physical restraints should only be used as a last resort.

“We know from the research that physical restraint overall shows that it does not prevent falls,” she says. “In fact it may cause injury, and it may cause death.”

While there are circumstances where restraint may be appropriate McCabe says, “it is not there as a prolonged intervention”. Doing so, she says, “is an infringement of their human rights”.

After the 7.30program aired and one day before the Royal Commission hearings began, the federal government committed to stronger regulations around restraint, including that homes must document the alternatives they tried first.

Restraint by drugging

Another kind of restraint which has come into focus through the Royal Commission is chemical restraint. Psychotropic medication is currently prescribed to 80 percent of people with dementia in residential care – but it is only effective 10 percent of the time.

“We need to look at other interventions,” says McCabe. “The first to look at is: why is the person behaving in the way that they are? Why are they responding that way? It could be that they’re in pain. It could be something in the environment that is distressing them.”

She notes people with dementia often have “perceptual disturbances” – “things in the environment that look completely fine to us might not to someone living with dementia”. Wouldn’t you act out of character if your blue floor suddenly became a miniature sea, or a coat hanging on the door turned into the Babadook?

“It’s about people understanding of what it’s like to stand in the world of people living with dementia and simulate that experience for them,” says McCabe.

Whether through physical force or prescription, a dependence on restraint shows the extent to which dementia is misunderstood at the detriment of the autonomy and dignity of the sufferers. This misunderstanding is compounded by the fact that dementia is often present among other complex health problems.

Yet, and as the media may sensationally suggest, the aged care sector isn’t staffed by the callous or malicious. It is filled with good people, who are often overstretched, emotionally taxed and exhausted.

Dementia Australia is advocating for mandatory training on dementia for all people who work in aged care. This covers residential aged care, but could also extend to hospitals. Crucially, it encompasses community workers, too.

“Of the 447,000 Australians living with dementia, 70 percent live in the community and 30 percent live alone,” notes McCabe. “It’s harder to monitor community care, it’s less visible and less transparent. We have to make sure that the standards are across the board.”

It is only through listening to people living with dementia – recognising that while yes, they have a degenerative cognitive disease, they deserve to participate in the decision-making around their life and wellbeing – that our approach to it has evolved. Previously, people believed that it was dangerous to allow sufferers to cook, even to go out unaccompanied.

Likewise, it is crucial that we continue to afford people with dementia the full rights of personhood, however unfamiliar they may become. Only then can meaningful reform be made possible.

Besides, if for no other reason (and there are many other reasons), action is in our own selfish interest. The chances, after all, that you or someone you love will develop dementia are high.

MOST POPULAR

ArticleBeing Human

Philosophy must (and can) thrive outside universities

ArticleBeing Human

Ozi Batla: Fatherhood is the hardest work I’ve ever done

ArticleHEALTH + WELLBEING

Parent planning – we should be allowed to choose our children’s sex

BY Kate Prendergast

Kate Prendergast is a writer, reviewer and artist based in Sydney. She's worked at the Festival of Dangerous Ideas, Broad Encounters and Giramondo Publishing. She's not terrible at marketing, but it makes her think of a famous bit by standup legend Bill Hicks.

What is the definition of Free Will ethics?

What is the definition of Free Will ethics?

Opinion + AnalysisRelationships

BY The Ethics Centre 16 APR 2019

Free Will describes our capacity to make choices that are genuinely our own. With free will comes moral responsibility – our ownership of our good and bad deeds.

That ownership indicates that if we make a choice that is good, we deserve the resulting rewards. If in turn we make a choice that is bad, we probably deserve those consequences as well. In the case of a really bad choice, such as committing murder, we may have to accept severe punishment.

The link between free will and responsibility has both theological and philosophical roots.

Within theology, for example, the claim that humans are ‘made in the image of God’ (a central tenet of major religions like Judaism, Christianity and Islam) is not that they are the physical image of their creator.

Rather, the claim is made that humans are made in the ‘moral image’ of God – which is to say that they are endowed with the ‘divine’ capacity to exercise free will.

Of course, the experience of free will is not limited to those who hold a religious belief. Philosophers also argue that it would be unjust to blame someone for a choice over which they have no control.

Determinism is the belief that all choices are determined by an unbroken chain of cause and effect. Those who believe in ‘determinism’ oppose free will, arguing that that the belief that we are the authors of our own actions is a delusion.

Whereas scientific evidence has found there is brain activity prior to the sensation of having made a choice, we’re unable to resolve the question of which account is correct.

Should that gap close – and free will be proven to be an illusion, then the basis for ascribing guilt to those who act unethically (including criminals) will also be destroyed.

How could we justify punishing a person who claims that they had no choice but to do evil?

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Particularism

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Hope

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Science + Technology

The ethics of exploration: We cannot discover what we cannot see

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

5 ethical life hacks

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

After Christchurch

After Christchurch

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + LeadershipPolitics + Human RightsRelationships

BY Simon Longstaff 19 MAR 2019

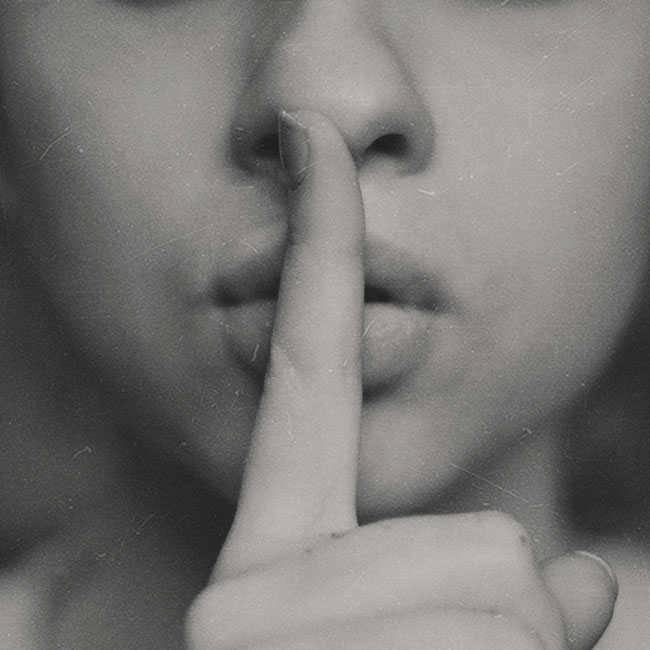

What is to be said about the murder of innocents?

That the ends never justify the means? That no religion or ideology transmutes evil into good? That the victims are never to blame? That despicable, cowardly violence is as much the product of reason as it is of madness?

What is to be said?

Sometimes… mute, sorrowful silence must suffice. Sometimes… words fail and philosophy has nothing to add to our intuitive, gut-wrenching response to unspeakable horror.

Thus, we bow our heads in silence… to honour the dead, to console the living, to be as one for the sake of others.

In that silence… what is to be said?

Nothing.

Yet, I feel compelled to speak. To offer some glimmer of insight that might hold off the dark — the dark shades of vengeance, the dark tides of despair, the dark pools of resignation.

So, I offer this. Even in the midst of the greatest evil there are people who deny its power. They are rare individuals who perform ‘redemptive’ acts that affirm what we could be. Some call them saints or heroes. They are both and neither. They are ordinary people who act with pure altruism – solely for the sake of others, with nothing to gain.

One such person is with me every day. The Polish doctor and children’s author, Janusz Korczak, cared for orphaned Jewish children confined to the Warsaw Ghetto. At last, the time came when the children were to be transported to their place of extermination. Korczak led his children to the railway station — but was stopped along the way by German officers. Despite being a Jew, Korczak was so revered as to be offered safe passage.

To choose life, all he need do was abandon the children. At the height of the Nazi ascendancy, Korczak had no reason to think that he would be remembered for a heroic but futile death. He had nothing to gain. Yet, he remained with the children and with them went to his death. He did so for their sake — and none other. In that decision, he redeemed all humanity — because what he showed is the other face of our being, the face that repudiates the murderer, the terrorist, the racist…the likes of Brenton Tarrant.

I know that many people do not believe in altruism. They will offer all manner of reasons to explain it away, finding knotholes of self-interest that deny the nobility of Janusz Korczak’s final act. They are wrong. I have seen enough of the world to know that pure acts of altruism are rare — but real. And it only takes one such act to speak to us of our better selves.

We will never know precisely what happened in those mosques targeted in Christchurch. However, I believe that, in the midst of the terror, there were people who performed acts of bravery, born out of altruism, of a kind that should inspire and ultimately comfort us all.

Most of these stories will be untold — lost to the silence. Of a few, we may hear faint whispers. But believe me, the acts behind those stories are every bit as real as the savagery they confronted and confounded. And even when whispered, they are more powerful.

Evil born of hate can never prevail. It offers nothing and consumes all — eventually eating its own. That is why good born of love must win the ultimate victory. Where hate takes, love gives — ensuring that, in the end, even a morsel of good will tip the balance.

You might say to me that this is not philosophy. Where is the crisp edge of logic? Where is the disinterested and dispassionate voice of reason? Today, that voice is silent. Yet, I hope you can hear the truth all the same.

Dr Simon Longstaff AO is Executive Director of The Ethics Centre.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Dame Julia Cleverdon on social responsibility

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Why have an age discrimination commissioner?

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Want #MeToo to serve justice? Use it responsibly.

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Pay up: income inequity breeds resentment

BY Simon Longstaff

Simon Longstaff began his working life on Groote Eylandt in the Northern Territory of Australia. He is proud of his kinship ties to the Anindilyakwa people. After a period studying law in Sydney and teaching in Tasmania, he pursued postgraduate studies as a Member of Magdalene College, Cambridge. In 1991, Simon commenced his work as the first Executive Director of The Ethics Centre. In 2013, he was made an officer of the Order of Australia (AO) for “distinguished service to the community through the promotion of ethical standards in governance and business, to improving corporate responsibility, and to philosophy.” Simon is an Adjunct Professor of the Australian Graduate School of Management at UNSW, a Fellow of CPA Australia, the Royal Society of NSW and the Australian Risk Policy Institute.

What ethics should athletes live by?

What ethics should athletes live by?

Opinion + AnalysisHealth + WellbeingRelationships

BY The Ethics Centre 10 MAR 2019

Athletes are bound by multiple codes – including the formal rules of the games they play and the informal conventions that define what is deemed to be acceptable conduct.

Professional athletes are often bound by a more stringent code that governs many aspects of their public and private lives. In an era of social media and phone cameras, lucrative sponsorships and media rights, online sports betting and performance enhancing drugs, there is very little that isn’t regulated, measured or scrutinised.

The culture of sport

The formal rules of any game establish the minimum standards that bind players and officials equally in order to ensure a fair contest. Not surprisingly, the formal rules are relative to the sports that they define: you can tackle someone to the ground in a rugby match (provided they’re holding the ball), but it would be deemed unacceptable in tennis.

But there are also conventions and informal obligations that define the culture of sport. For example, most sports establish informal boundaries that seek to capture a spirit of good sportsmanship. The cricketer who refuses to “walk” after losing their wicket – or who delivers a ball under-arm – may not be breaking any formal rule, but they’ll be offending the so-called spirit of cricket.

The sanctions for such an offence may be informal, but may blight that player’s career.

A question of trust

In sport, the bottom line is trust. Sportspeople are stewards for the games they play – with an obligation not to destroy the integrity of the sports in which they participate. Athletes tend to be intensely competitive, seeking victory for themselves, for their team or sometimes their nation.

Professional sports sell themselves to the public on the basis that the contests are real and, hopefully, fair. Every time two teams or competitors walk out onto the field of play, they place so much at stake – far more than just the result of one game.

That is why evidence of match fixing, doping or cheating is so destructive – it destroys public trust in the veracity of the competition that people pay to watch. It damages the reputation of the sport. And it is ultimately self-defeating – always leaving doubt in the dishonest victor’s mind, denying forever the satisfaction of a honest win.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Big thinker

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Big Thinker: Shulamith Firestone

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Vulnerability

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

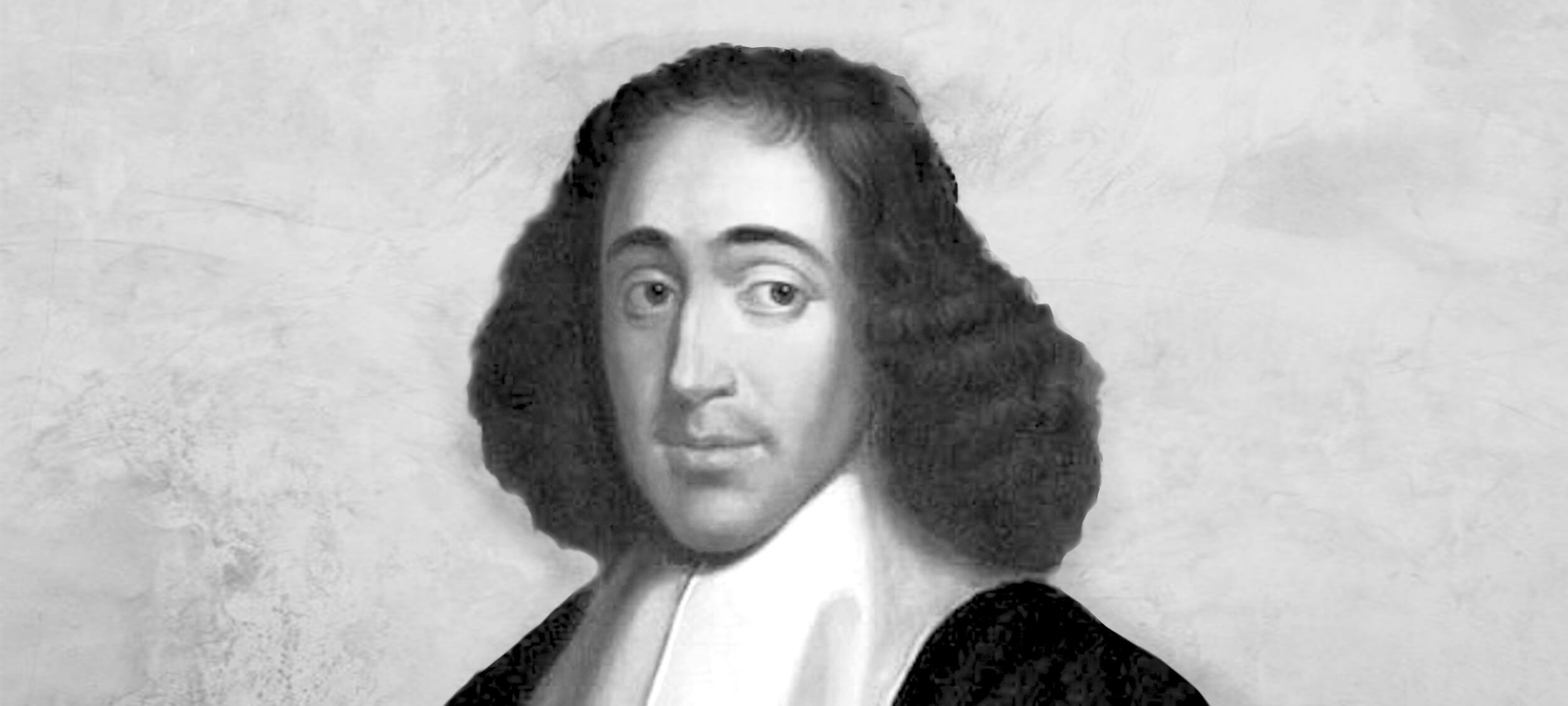

Big Thinker: Baruch Spinoza

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

The niceness trap: Why you mustn’t be too nice

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

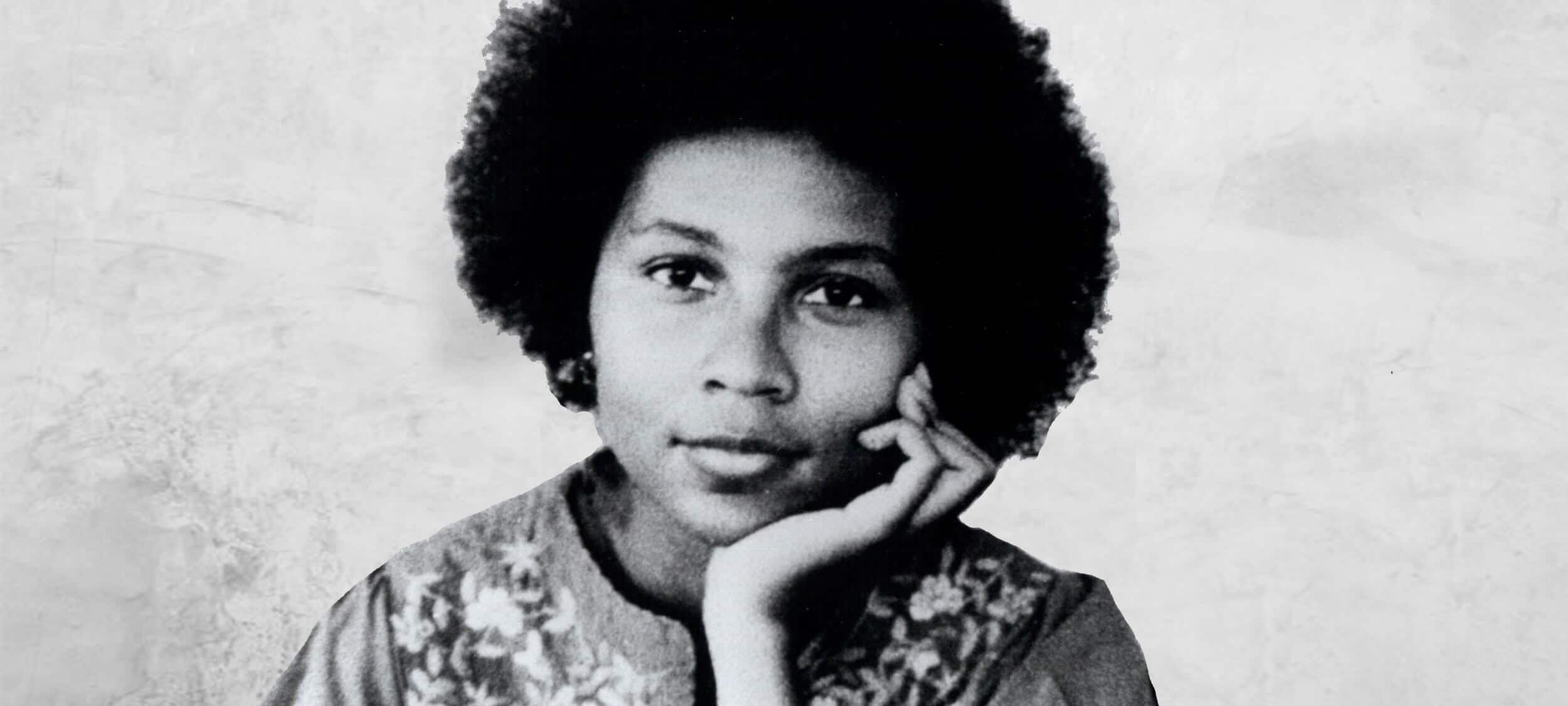

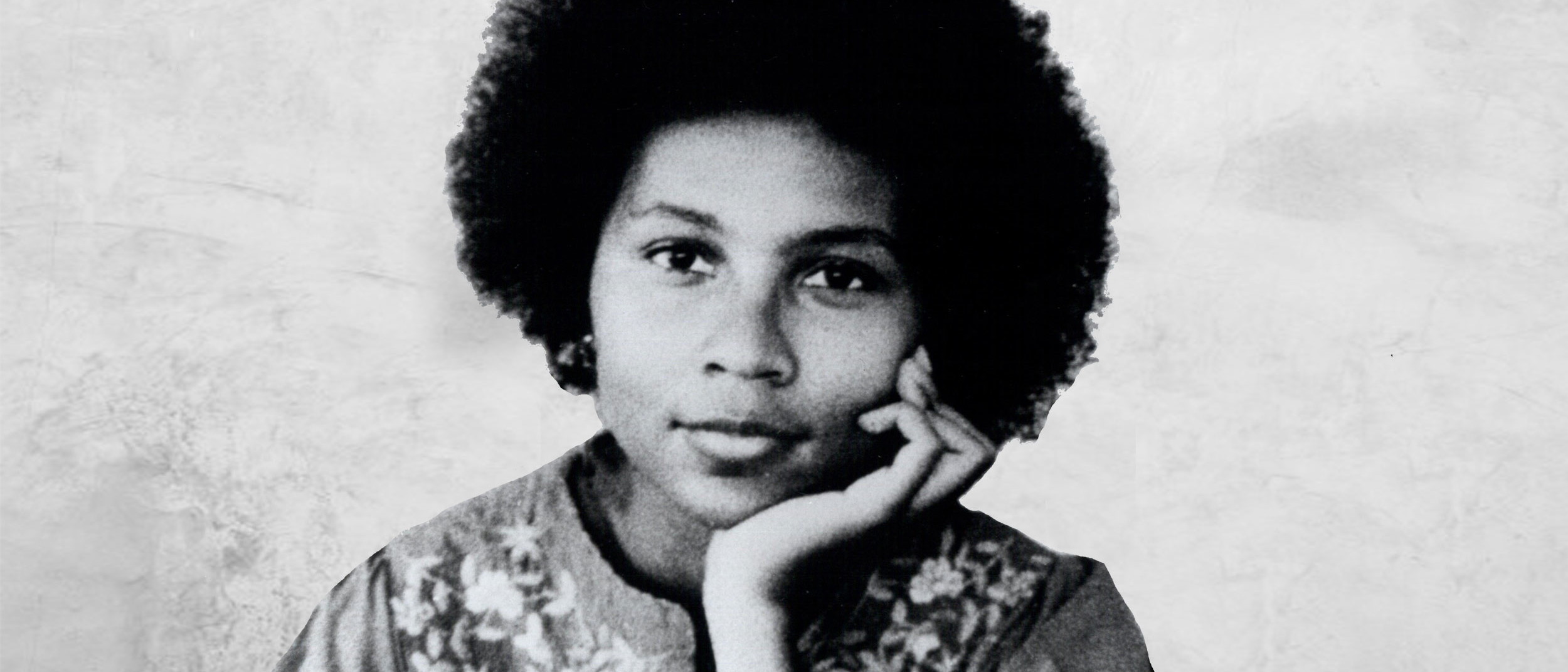

Big Thinker: bell hooks

An outspoken professor, author, activist and cultural critic, bell hooks (1952-2021) drew attention to how feminism privileges white women’s struggles, while advocating for a more holistic way of understanding oppression.

Born Gloria Jean Watkins, bell hooks was a child who spoke back. Growing up in a segregated community of the south-central US state Kentucky, she fought against the ways in which her family and society sought to relegate her into a docile, black female identity. This refusal to be complicit in perpetuating her own oppression would define her life and career as a leader in black feminist thought.

It was when she first spoke back in public that she initially identified with her self-claimed moniker. An adult had dismissed her with a comparison to Bell Hooks, her maternal grandmother, in whose bold tongue and defiant attitude she found inspiration. She decapitalised the initials in order for others to focus on the substance of her ideas, rather than herself as a person.

hooks would become a prolific author and commentator. With notable titles including Talking Back, Ain’t I a Woman? and From Margin to Centre, her work scrutinises and challenges the ways in which media, culture and society uphold dominant oppressive structures.

Interlocking oppressions

A popular version of second wave feminism posited that all systems of oppression stemmed from patriarchy. This, hooks rejected. Instead, she introduced the idea that different types of oppression are interlocking and power is relational depending upon where you’re located on the matrix of class, sex, race and gender – which is not unlike the ideas underpinning the currently popular intersectional feminism.

hooks invented the term ‘imperialist white supremacist capitalist patriarchy’ to emphasise the multidimensionality of these power relations. She continues to use it today.

At the time, hooks’ paradigm was considered radical in that it undermined the notion there was a fundamentally common female experience. Many assumed this was vital for feminist solidarity to be forged and political unity maintained. Sisterhood was more complicated than that, hooks said – and to deny the uniqueness of each woman’s status and circumstance was another form of oppression.

Bold and to the point

While coming from academia, hooks strives to make her ideas easily accessible to a broad audience. Her writing style is free of jargon and often humorous, and she regularly appears in documentaries, open venues and television talk shows.

hooks is also renowned for focusing a sharp critical lens on popular culture, showing a strong opposition to political correctness. She’s criticised Spike Lee’s films, media coverage of the OJ Simpson trial and the lauded basketball documentary Hoop Dreams.

She also hasn’t held back her thoughts on prominent feminists.

hooks criticised Madonna for repudiating feminist principles by chasing stardom, and fetishising black culture in her film clips and live shows while reinforcing stereotypes of black men as violent primitives in a 1996 interview.

Twenty years later, she called the pop queen of lady power Beyoncé an ‘anti-feminist terrorist’, citing concern over the influence sexualised images of her have on young girls.

hooks also expressed disappointment Michelle Obama positioned herself as the nation’s ‘chief mum’, saying that by effacing her identity as an Ivy League educated lawyer, she was appeasing white hatred.

Oppositional gaze

Laura Mulvey introduced the theory of the ‘male gaze’ in the ’70s. It explains how images – particularly Hollywood mainstream images – are created to reproduce dominant male heteronormative ways of looking. hooks, who was fascinated with film as the most ‘efficient’ ideological propaganda tool, coined an associated term on black spectatorship: the ‘oppositional gaze’.

Looking has always been a political act, hooks argued. For subordinates in relations of power, looks can be “confrontational, gestures of resistance” which challenge authority. Had a black slave looked directly at a white person of status, they risked severe punishment – even death. Yet “attempts to repress our/black people’s right to gaze had produced in us an overwhelming longing to look, a rebellious desire, an oppositional gaze,” writes hooks.

“By courageously looking, we defiantly declared: ‘Not only will I stare. I want my look to change reality.’”

Black spectatorship of early Hollywood cinema was processed through this oppositional gaze. It was abundantly clear to these viewers, hooks writes, that film reproduced white supremacy. They saw nothing of themselves reflected in this white-washed fantasy realm. Black independent cinema emerged as an expression of resistance.

At the same time, hooks saw television and film as a site where black viewers were able to subject white representations to an interrogative gaze. Carried out in the privacy of the home or in a darkened cinema, this action also carried no risk of reprisal. That black men could look at white female bodies without fear was hugely significant – it was only 1955 when 14-year-old African American Emmett Till was lynched after being accused of offending a white woman in a Mississippi grocery store.

But while black male spectators “could enter an imaginative space of phallocentric power,” the experience of the black female spectator was vastly different, hooks writes. In both white and black productions, the male gaze still overdetermined screen images of women, and frequently idolised white female stars as the supreme objects of desire.

This continued the “violent erasure of black womanhood” in screen culture, making identification with any of the depicted subjects disenabling. While this denied black women the typical joys of watching, the fact that they “looked from a location that disrupted” meant that they could become “enlightened witnesses” through critical spectatorship.

Modern feminism in crisis

Despite the advances of women in the workplace, hooks nonetheless sees today’s feminism in a state of crisis. Firstly, she believes that we still haven’t addressed egalitarianism in the home, leaving women belittled and frustrated in heteronormative relationships.

She also believes that feminism today has lost its radical potential, in that it has converged too closely with radical individualism. Feminism does not mean that as a woman “you can do whatever you want, that you can have it all”, she says. Instead, if you’re to live inside a feminist framework, you need to undertake specific everyday actions. For this reason, hooks believes there are very few true living feminists.

Still, she remains a firm advocate of feminist politics, saying “My militant commitment to feminism remains strong…”

…and the main reason is that feminism has been the contemporary social movement that has most embraced self-interrogation. When we, women of color, began to tell white women that females were not a homogenous group, that we had to face the reality of racial difference, many white women stepped up to the plate. I’m a feminist in solidarity with white women today for that reason, because I saw these women grow in their willingness to open their minds and change the whole direction of feminist thought, writing and action.

This continues to be one of the most remarkable, awesome aspects of the contemporary feminist movement. The left has not done this, radical black men have not done this, where someone comes in and says, “Look, what you’re pushing, the ideology, is all messed up. You’ve got to shift your perspective.” Feminism made that paradigm shift, though not without hostility, not without some women feeling we were forcing race on them. This change still amazes me.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Explainer

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Social philosophy

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Moral Relativism

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Uncivil attention: The antidote to loneliness

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Paralympian pay vs. Olympian pay

BY Kate Prendergast

Kate Prendergast is a writer, reviewer and artist based in Sydney. She's worked at the Festival of Dangerous Ideas, Broad Encounters and Giramondo Publishing. She's not terrible at marketing, but it makes her think of a famous bit by standup legend Bill Hicks.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Adoption without parental consent: kidnapping or putting children first?

Adoption without parental consent: kidnapping or putting children first?

Opinion + AnalysisPolitics + Human RightsRelationships

BY Oliver Jacques 15 JAN 2019

Adoption without parental consent: kidnapping or putting children first?

Australia’s two biggest states are moving in opposite directions when it comes to adoption. While New South Wales is accused of tearing families apart, is Victoria right to deny children a voice?

A new stolen generation is coming to you soon.

Or so you would think if you read the reaction to recent NSW reforms aimed at making adoption easier.

NSW Parliament has passed new laws placing a two year time limit on a child staying in foster care. After this time, the state can pursue adoption if a child can’t safely return home, even if birth parents don’t agree.

Critical articles across media raised the spectre of another stolen generation.

An open letter signed by 60 community groups said the NSW Government was “on a dangerous path to ruining lives and tearing families apart”. Indigenous writer Nayuka Gorrie tweeted, “Adoption without parental consent is kidnapping”.

But should a parent really have the right to block the adoption of the child they neglected?

Laws prohibit journalists from identifying people involved in child protection cases so media coverage rarely includes the views of children, even after they turn 18. The laws exist to protect vulnerable minors, but such voices could add some balance to the debate and explain why NSW is ahead in putting children first.

Foster care crisis

Out-of-home care adoption – where legal parenting rights are transferred from birth parents to foster parents – is extremely rare in Australia. Last year, there were 147 children foster care adoptions. That’s a tiny fraction of the 47,000 Australian children living in out-of-home care.

Previously, kids could be placed in state care simply because they were born to a single mother or an Aboriginal woman.

These days, child protection workers only remove children if their lives are in danger due to repeated abuse or neglect.

While foster care is supposed to be a temporary arrangement, children on average spend 12 years in care, often bouncing from one temporary home to another.

It’s no surprise more than a third of foster children end up homeless soon after leaving care.

Permanent care instead of adoption

While NSW is trying to make adoption easier, Victoria is not. None of the more than 10,000 children in Victorian state care were adopted last year.

Victorian children who can’t return home are placed in ‘permanent care’, where they remain a ward of the state but are housed by the same foster carers until age 18.

Paul McDonald, CEO of Anglicare Victoria, describes permanent care as a “win-win-win” for children, birth parents and foster carers. He argues it provides stability for children without changing their legal status “so dramatically”.

Ignoring children’s voices

Former AFL player Brad Murphy, who grew up in Victorian permanent care, begs to differ. “From a child’s perspective, you don’t always feel secure in permanent care,” he said. “I longed for adoption. I wanted to belong to my foster parents, I wanted the same surname.”

Victoria didn’t allow him to be adopted by his loving foster carers because his birth father wouldn’t provide consent.

Murphy believes the Victoria Government should give children a say. “When I was 3 years old, I was calling my foster carer ‘Mum’, as I do now at age 33. I always knew what I wanted”.

The other problem with denying children an adoption choice is they continue to belong to the state. “Government were making all the decisions in my life. And like everything with government, it’s never done quickly,” Murphy said.

He often missed out on school camps and excursions because bureaucrats didn’t sign off permission.

Brad was placed in foster care at 16 months of age. Soon after, his mother ‘did a runner’ to Western Australia. His father was in jail for most of his childhood.

“I was never going back to my birth parents. If birth parents don’t make any effort to change their ways, why should the child suffer any longer?”

Case for reform

There are other parents, though, who want to change their ways but support is scarce. Housing, counselling and rehab facilities across Australia are lacking for low income families.

Some argue we should devote more resources toward keeping vulnerable families together, rather than promoting adoption reform.

There is no reason why we can’t do both. Help families where change is possible, but give children a choice when it’s not.

Though separating children from birth parents can prove traumatic, so is constant abuse. Some kids are terrified of their parents and want stability and the feeling of belonging with their new family.

In NSW, caseworkers must ask children what they want, if they’re old enough to understand. Prospective adoptive parents must educate kids about their history and culture. Birth parents can remain connected to children when it’s safe and in the child’s interests.

Overseas studies show adopted children have better life outcomes than those who remain in long term foster care.

Adoption won’t work for everyone, but it could benefit many kids.

Those criticising NSW reforms should also ask the Victorian government why it continues to deny children the basic human right to be heard.

Are you facing an ethical dilemma? We can help make things easier. Our Ethi-call service is a free national helpline available to everyone. Operating for over 25 years, and delivered by highly trained counsellors, Ethi-call is the only service of its kind in the world. Book your appointment here.

Oliver Jacques is a freelance journalist and writer.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Big thinker

Relationships, Society + Culture

Big Thinker: Simone de Beauvoir

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights

Should corporate Australia have a voice?

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

What we owe our friends

Big thinker

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Big Thinker: Eleanor Roosevelt

BY Oliver Jacques

Oliver Jacques is a freelance writer and tutor based in Griffith, NSW. His writing has appeared in the Sydney Morning Herald, The Guardian, ABC, SBS, Daily Telegraph, Herald Sun, Eureaka Street and The Shovel. He has a Masters Degree in Public Policy at ANU; a graduate certificate in journalism at UTS; and has completed courses in copywriting and search engine optimisation at the Australian Writers Centre.

5 Movies that creepily foretold today’s greatest ethical dilemmas

5 Movies that creepily foretold today’s greatest ethical dilemmas

Opinion + AnalysisRelationshipsSociety + Culture

BY Aisyah Shah Idil 18 DEC 2018

Climate change. Nuclear war. Artificial intelligence. A new pandemic.

According to the non-profit organisation 80,000 Hours, these are the greatest threats to humanity today. Yet the big movie studios have been calling it for decades and were pondering the ethics behind these threats long ago.

1. Planet of the Apes (1968)

Seeing Charlie Heston scream in despair at a shattered Statue of Liberty still spooks the most apathetic viewer. And it’s as shocking a warning against nuclear weapons now as it was in the middle of the Cold War 50 years ago.

In Planet of the Apes, humans are being hunted. The primates they once experimented on have grown into intelligent, complex, political creatures. Humanity has regressed into primitive vermin to either be killed outright, enslaved, or used in scientific experiments. The strict ape hierarchy demands utility over compassion, holding a mirror up to the same vices that led humanity to destruction.

—————

2. 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968)

When a survey of living computer science researchers shows half think there’s a greater than 50 percent chance of “high-level machine intelligence” – one that reaches then exceeds human capabilities – it’s right to be concerned.

2001: A Space Odyssey begins with a jaunty trip to Jupiter. An optimistic team is led aboard by HAL 9000, the ship’s computer, but begin to suspect there’s more to the trip than they’ve been told.

After all, there are two sides to the utilitarian coin. What is murder to us is just programming to a robot.

—————

3. The Matrix (1999)

If reality is a simulation by super intelligent sentient machines, what does any self-respecting hacker do? Start a rebellion.

The Matrix goes even further than 2001: A Space Odyssey. Here, the machines are Descartes’ evil demon, unsatisfied with just killing us. Instead, they mine us for energy to survive, and keep us subservient on a diet of virtual reality. A world of love, work, boring parties, and paying bills occupy us while they use us as slaves.

The point of tension in The Matrix centres around the theory of Plato’s Cave. If you know what everyone is experiencing is an illusion, should you tell them?

—————

4. 28 Days Later (2002)

28 Days Later paints a bleak picture of a world unprepared to deal with the effects of an aggressive pandemic. And it’s not as unbelievable as it may seem. According to 80,000 Hours, the money invested into pandemic research isn’t nearly as much as we need.

From HIV-AIDS, Ebola, and Zika, we’ve seen countries drag their feet over who pays to contain one, or struggle to move people and supplies to where they’re needed.

“When you’re in the middle of a crisis and you have to ask for money”, says Dr. Beth Cameron at the Nuclear Threat Initiative, “you’re already too late”.

—————

5. Children of Men (2006)

What is arguably more important than any of these things is hope. And that’s what our last movie recommendation is about.

After two decades of unexplained female infertility, war, and anarchy, human civilisation is on the brink of collapse. Civil servant Theo Faron has lost all hope as the last generation of his species. Then he meets Kee – an illegal immigrant and the first woman to be pregnant in eighteen years.

The hope for a better future, for a future that is more just and more compassionate, adds intangible meaning to our struggles today. It becomes reasonable to struggle, to suffer, and even to die for this kind of hope.

What makes the hope of today different is that we are now closer to “hypotheticals” than we have ever been.

Are we prepared to turn this hope into action? Effective altruism offers one way to find out.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

The ‘good ones’ aren’t always kind

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

When are secrets best kept?

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Science + Technology, Society + Culture

5 things we learnt from The Festival of Dangerous Ideas 2022

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Society + Culture

Respect for persons lost in proposed legislation

BY Aisyah Shah Idil

Aisyah Shah Idil is a writer with a background in experimental poetry. After completing an undergraduate degree in cultural studies, she travelled overseas to study human rights and theology. A former producer at The Ethics Centre, Aisyah is currently a digital content producer with the LMA.

Ethics Explainer: Existentialism

If you’ve ever pondered the meaning of existence or questioned your purpose in life, you’ve partaken in existentialist philosophy.

It would be hard to find someone who hasn’t asked themselves the big questions. What is the meaning of life? What is my purpose? Why do I exist? For thousands of years, these questions were happily answered by the belief your purpose in life was assigned prior to your creation. The existentialists, however, disagreed.

Existentialism is the philosophical belief we are each responsible for creating purpose or meaning in our own lives. Our individual purpose and meaning is not given to us by Gods, governments, teachers or other authorities.

In order to fully understand the thinking that underpins existentialism, we must first explore the idea it contradicts – essentialism.

Essentialism

Essentialism was founded by the Greek philosopher Aristotle who posited everything had an essence, including us. An essence is “a certain set of core properties that are necessary, or essential for a thing to be what it is”. A book’s essence, for example, is its pages. It could have pictures or words or be blank, be paperback or hardcover, tell a fictional story or provide factual information. Without pages though, it would cease to be a book. Aristotle claimed essence was created prior to existence. For people, this means we’re born with a predetermined purpose.

This idea seems to imply, whether you’re aware of it or not, that your purpose in life has been determined prior to your birth. And as you live your life, the decisions you make on a daily basis are contributing to your ultimate purpose, whatever that happens to be.

This was an immensely popular belief for thousands of years and gave considerable weight to religious thought that placed emphasis on an omnipotent God who created each being with a predetermined plan in mind.

If you agreed with this thinking, then you really didn’t have to challenge the meaning of life or search for your purpose. Your God already provided it for you.

Existence precedes essence

While philosophers including Søren Kierkegaard, Fyodor Dostoyevsky and Friedrich Nietzsche questioned essentialism in the 19th century, existentialism was popularised by Jean-Paul Sartre in the mid-20th century following the horrific events of World War II.

As people questioned how something as catastrophically terrible as the Holocaust could have a predetermined purpose, existentialism provided a possible answer that perhaps it is the individual who determines their essence, not an omnipotent being.

The existentialist movement asked, “What if we exist first?”

At the time it was a revolutionary thought. You were created as a blank slate, tabula rasa, and it is up to you to discover your life’s purpose or meaning.

While not necessarily atheist, existentialists believe there is no divine intervention, fate or outside forces actively pushing you in particular directions. Every decision you make is yours. You create your own purpose through your actions.

The burden of too much freedom

This personal responsibility to shape your own life’s meaning carries significant anxiety-inducing weight. Many of us experience the so-called existential crisis where we find ourselves questioning our choices, career, relationships and the point of it all. We have so many options. How do we pick the right ones to create a meaningful and fulfilling life?

“Man is condemned to be free; because once thrown into the world, he is responsible for everything he does” – John-Paul Sartre

Freedom is usually presented positively but Sartre posed that your level of freedom is so great it’s “painful”. To fully comprehend your freedom, you have to accept that only you are responsible for creating or failing to create your personal purpose. Without rules or order to guide you, you have so much choice that freedom is overwhelming.

The absurd

Life can be silly. But this isn’t quite what existentialists mean when they talk about the absurd. They define absurdity as the search for answers in an answerless world. It’s the idea of being born into a meaningless place that then requires you to make meaning.

The absurd posits there is no one truth, no inherent rules or guidelines. This means you have to develop your own moral code to live by. Sartre cautioned looking to authority for guidance and answers because no one has them and there is no one truth.

Living authentically and bad faith

Coined by Sartre, the phrase “living authentically” means to live with the understanding of your responsibility to control your freedom despite the absurd. Any purpose or meaning in your life is created by you.

If you choose to live by someone else’s rules, be that anywhere between religion and the wishes of your parents, then you are refusing to accept the absurd. Sartre named this refusal “bad faith”, as you are choosing to live by someone else’s definition of meaning and purpose – not your own.

So, what’s the meaning of life?

If you’re now thinking like an existentialist, then the answer to this question is both elementary and infinitely complex. You have the answer, you just have to own it.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture, Relationships

Stoicism on Tiktok promises happiness – but the ancient philosophers who came up with it had something very different in mind

Big thinker

Relationships

Big Thinker: René Descartes

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

The philosophy of Virginia Woolf

Big thinker

Relationships

Big Thinkers: Laozi and Zhuangzi

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Is it ethical to splash lots of cash on gifts?

Is it ethical to splash lots of cash on gifts?

Opinion + AnalysisRelationships

BY Aisyah Shah Idil 10 DEC 2018

Whether you’re a tearer, a folder, a scruncher, or a chucker, there’s nothing like opening a wrapped gift that’s especially suited to you.

Amid the hugs and backslaps it’s hard to say who it’s more satisfying for – the giver or the receiver.

But when little Millie gets the new PlayStation while Amir’s staring at his plastic water gun, the thin film of politeness peels away. We don’t just wonder why we have the gifts we do. We wonder how much they cost.

This holiday season, we’re exploring the ethical dimensions of splurging on gifts. Are there unspoken rules for those with deeper pockets? Is it killing the spirit of generosity to peer at the price tag? Or is keeping mum about money letting us pretend we don’t owe things to each other all the time?

Christmas conundrums? Book a free appointment with Ethi-call. A non-partisan, highly trained professional will help you navigate any ethical minefields this holiday season.

There are so many different kinds of purposes tied to gift giving on Christmas, or any large celebration. We like to think of these sorts of gifts as intrinsically good, making them different from bribes given for personal gain.

For some, gifts are an informal way to foster love and support in mutual relationships. They encourage closeness and dependencies between social circles to reveal links our individualism tends to hide.

They’re known to shape our moral character and encourage selfless generosity, even to remove feelings of emotional debt that have accumulated throughout the year. Though we speak of gifts as just ways to “show love and appreciation”, our reasons are often more layered than that.

This doesn’t have to be self-indulgent navel-gazing. Examining the purpose of a gift matters because it encourages us to consider if that special, one-of-a-kind purchase is the only way to fulfil it. What duties or consequences should you consider before making that jump?

The duties of gifting

If you are feeling the end of year pinch, you have a duty to yourself to make sure the gift giving season doesn’t put you into financial strife. But if that conflicts with the duty to be fair to your friends and family, ask yourself what matters more. After all, gifts are often an exchange, and appreciating someone’s thoughtfulness can come with offering a similarly tasteful gift of your own.

If the gift is for a friend or peer, we might worry about setting an expectation or precedent we can’t fulfil. If it’s for someone who would struggle to fork out a similar amount of money for a gift, would this leave them feeling uncomfortably tied to you? And if you want to spread the holiday cheer, this leaves your pool of lucky recipients fairly limited.

Nor can the growing consciousness around our impact on the environment be ignored. Are these gifts worth the cost to landfills, unethical supply chains, and our collective duty to preserve the health of the land we live on?

But let’s not dwell on the negative. There are heaps of positive consequences too. Don’t forget the good that comes from making the people around you feel extra special and appreciated. If you struggle with miserliness, or excessive penny pinching, this could be a win-win way to encourage generosity in you, and make someone else very happy. It’s always worth thinking of how your actions reflect your character.

When all is said and done, the holidays are a time to rest. The softening pleasures of food, drink, company and play don’t have to get in the way of a well examined life. In fact, slowing down our frenetic, demanding lives to allow time to recuperate may be just what we need most: the modest admission that we cannot do everything perfectly. Good enough is good enough.

That’s the spirit!

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

From capitalism to communism, explained

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Only love deserves loyalty, not countries or ideologies

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

We shouldn’t assume bad intent from those we disagree with

Explainer

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships