A critical thinker’s guide to voting

A critical thinker’s guide to voting

Opinion + AnalysisPolitics + Human RightsRelationships

BY Dr Luke Zaphir 14 APR 2025

In Australia, we have no formalised method of teaching people about politics, voting and elections. Most people vote the same way as their parents in their first elections, and won’t receive any more education beyond how-to-vote cards and electoral ads.

People under the age of 25 make up about 10% of all voters – that’s about ten thousand per electorate. They’re the most underrepresented group in political discourse and in elections. Not only that but young people will have to live with the consequences of these policies far longer than any other demographic.

Given that some elections come down to only a few hundred votes, the way we vote really does matter.

Our votes matter beyond the current election – they affect future elections too. The Australian Electoral Commission provides funding for every candidate or group that receives more than 4% of first preference votes. This means that even small groups can become big factors, influencing future elections and swaying the balance of power in parliament.

Finally, democracy works because it’s about communicating our needs and visions of the future. The major parties pay attention to how and why people vote. The Labor and Liberal parties have issues that they care about but others they overlook. A vote can shift the way the policy platforms of the major parties to discuss the issues we care about.

Here is a practical guide to critically think about your vote.

Step 1: Ignore the hype

Political parties are really good at demonising each other. They’ll accuse each other of being craven, lying, baby eating monsters. None of this is useful information. Almost every piece of political messaging from every party is propaganda designed to get your vote. They’ll frame the issues in terms of economics, jobs, the environment or tradition. This anchors our thinking in a way that is unhelpful for choosing a candidate, making it difficult to consider nuance and complexity.

Step 2: Value democratic integrity

Our democracy cannot function if our representatives are known liars, are demonstrably corrupt, or engage in unscrupulous mudslinging against other candidates. Everyone believes they are morally correct but if the candidate spends their time hurling insults, they’re actively toxic to our democracy. If the candidate is willing to say or do anything to get elected, they can’t be trusted to further the public good and should come last on the ballot.

Our democracy only functions if its processes are open, fair and honest. Recent changes to the ways political candidates are allowed to fundraise means that it may be easier for incumbents to stay in power, and harder for newcomers to challenge them. It’s worth looking into whether your member of parliament supported these changes, or aims for a level playing field.

Step 3: Think about your values

The most fundamental part of knowing who to vote for is knowing what your values are. There are an endless number of beliefs that we might hold. We might believe in universalism and benevolence (welfare for all, tolerance and understanding), which lead to policies like a universal basic income, investment in public broadcasters like the ABC, and increasing foreign aid. Values such as self-direction and achievement are more important to us (pursuing and gaining personal success) lead to policies that minimise taxation and deregulation. Voting against same-sex marriage or changes to the constitution to include First Peoples are examples of valuing tradition, whereas policies that block foreign investment or advocate turning back asylum seeker boats prioritise security.

There’s no such thing as ‘having bad values’, but it’s important to know what we believe, why we believe it, and prioritise these when it comes to elections. Ask yourself how important each of your principles and goals are in turn, and if your vote will move you further towards them.

Step 4: Think about what you’d like for the country

Now that you understand your values, think about how they inform the kind of country you want Australia to become. Political parties offer massive packages of policies containing aspects we agree with or may not like. Vote compasses can be useful at this point in this task – they have specific policy directions that allow us to precisely target what we would want to achieve in the country. This is an important step because we might agree with a party’s stated views but if their policies don’t match up, we’re not going to be represented well.

It’s common to agree with only part of a party’s political package. This is why we need to learn about all the candidates’ parties, their aims, and which best aligns with our own views. Preferential voting is a way of creating an order of best fit – with your number 1 preference going to the party that most aligns with your views, and each subsequent preference being the next best fit. The party that least represents your views should get your last preference.

Step 5: Learn about the parties

Labor and the Liberals are the most powerful and oldest parties in Australia. They aren’t exactly the same platforms as they once were, which is why second hand information from others may be out of date. The Greens are also a significant party and often hold the balance of power in the Legislative Assembly. There are many other parties that will be in your division and it’s worth looking into what they value and what their aim is specifically. There are many parties that focus on single issues that are important to them.

Step 6: Discover the candidates’ credentials and goals

The Australian Electoral Commission provides information about all currently enrolled candidates. Additionally, blogs like The Tally Room track candidates for each division and provide links to all of their personal websites.

A person’s qualifications and work history will tell us a bit about who someone is. Do they own a business? Ran a not-for-profit? Have they been a teacher or academic or front line retail worker? Have they been bankrupt? This is useful for telling us what kind of person we’re voting for and how they think.

Another important aspect is how clearly they’ve articulated their goals. Every party is in favour of good economic management, green technology and low unemployment figures. What matters is which they prioritise given the current context. It’s also worth considering what they plan in the long term – do they have a vision for Australia in 20 years? In 50? A party that only sees the future one electoral cycle ahead is one that will make short sighted decisions.

Lastly, if they can’t concisely say that they aim to enact a specific law or to increase a certain tax, we have reason to question their competence. A candidate can talk about the value of freedom all they want – without a stated goal, they either haven’t thought about it or they’re dog whistling.

Step 7: Judge the incumbent’s track record

The member of parliament for your division has a higher burden for gaining re-election because they have to defend their record. What have they done so far? What have they accomplished? How have they voted in the House of Representatives or Senate? Hansard is the official record of parliamentary speeches and votes. They Vote for You is a not-for-profit independent non-partisan organisation which tracks how the current member of parliament has voted (from Hansard). This includes their attendance (how often they do their job), and what they vote consistently for and against. This is particularly useful for us if we care about a specific issue – we can discover if the sitting member supports or votes against it in parliament.

A final thought

There are no wrong choices except those which are made with inaccurate information. This guide will take less than an hour and that’s not much to be conscientious about your vote once every three years. Democracy isn’t just about voting. It is in our civil discourse itself and how we share our perspectives.

Think about whether the status quo should stay the same or change based on your values and goals, then vote for the candidate that you believe represents your view. When you talk to people about who you’re voting for, be curious about their values and their perspective. From these together, you’ll have a thoughtful and well considered perspective.

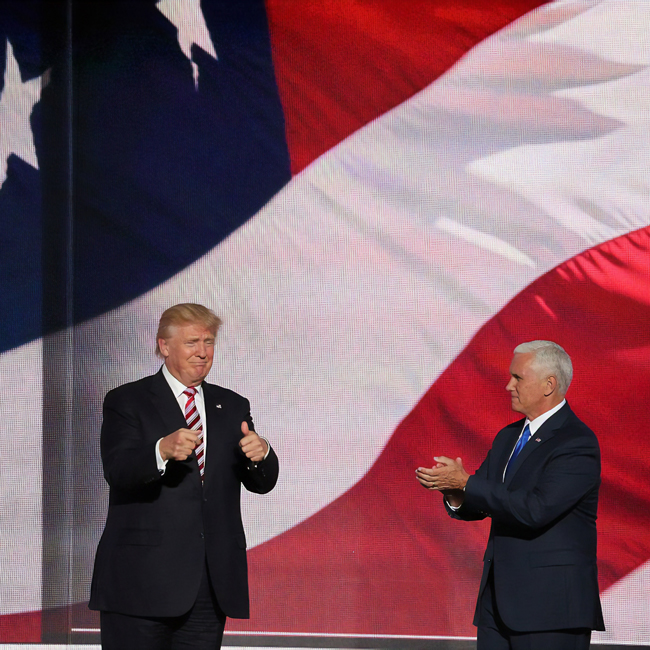

This article has been updated since its original publication in 2022. Image by AEC photo.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Big thinker

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Big Thinker: Germaine Greer

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights, Science + Technology

Not too late: regaining control of your data

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Send in the clowns: The ethics of comedy

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Why hard conversations matter

BY Dr Luke Zaphir

Luke is a researcher for the University of Queensland's Critical Thinking Project. He completed a PhD in philosophy in 2017, writing about non-electoral alternatives to democracy. Democracy without elections is a difficult goal to achieve though, requiring a much greater level of education from citizens and more deliberate forms of engagement. Thus he's also a practicing high school teacher in Queensland, where he teaches critical thinking and philosophy.

The ethics of pets: Ownership, abolitionism and the free-roaming model

The ethics of pets: Ownership, abolitionism and the free-roaming model

Opinion + AnalysisSociety + Culture

BY William Salkeld 16 DEC 2024

“If there are no dogs in heaven, I want to go where they go”, said the American performer, Will Rogers.

It is no secret that we are deeply connected to the animals we keep as pets. In Australia, most pet owners would like to think they treat their animals well. 52% of Australians consider their pets to be family members, and in 2021 Australians spent $30.7 billion on food, healthcare, and enrichment for their cats and dogs.

Studying animal ethics, I used to believe that pet ownership was a good thing. Following the arguments of moral philosopher Christine Korsgaard and many others, I saw it as a mutually beneficial situation. We provide our animals with the necessary conditions for a good life, such as food, shelter, healthcare, love and attention. In return, they provide us with companionship and countless other life-affirming benefits.

As long as we can provide our pets with the kind of life that is good for them, then having pets is a good thing, I reasoned. After all, how could I deny that my family’s Golden Retriever, Ruby, lived a charmed life full of play, food, and affection? As I would soon find out, the ethics of pet-keeping is far more complicated than ensuring our furry friends are ‘well taken care of’.

My view about pets was turned upside down after listening to a podcast with legal scholar and animal ethicist Gary Francione. Francione is an abolitionist, meaning that he believes that we should abolish all use and ownership of nonhuman animals, including pets. To understand this view, it is first important to understand the history of domesticated animals and pets.

Domesticated animals are those animals like dogs, cats, or sheep who have adapted or ‘tamed’ because of or by humans. While the jury is still out on how wolves initially interacted with humans to become dogs, humans have subsequently spent millennia forcibly breeding dogs to make them less aggressive, ‘cuter’, or specialised in some activity like cattle herding. Or, in the case of my family’s Golden Retriever, Ruby, it seems she has been bred to chew up sofas and love carrots (don’t ask).

As Francione puts it, we have domesticated dogs and cats into a state of perpetual childhood where they are dependent on us for basic care. Yet, unlike children, cats and dogs don’t grow up and become independent; they remain in a state of dependency for their entire lives.

The animals we keep as pets are a subset of domesticated animals. The concept of pet ownership in Western countries is surprisingly recent, beginning in the Victorian era. Our entitlement to owning pets has not existed throughout history, meaning we should be critical of current ethical attitudes towards pets.

For abolitionists like Francione, the problem of pet ownership is twofold. One, the state of dependency is problematic because we have bred animals to become dependent on us. Imagine if someone raised their child to be completely dependent on them and to never reach true adulthood; we would likely call it emotional abuse. Yet in the case of pets, it is considered ‘proper training’.

Second is the problem of ownership and possession. Animals (including pets) are treated as property in the law. It’s even in the name: ‘pet ownership’. Most of us know that animals are sentient, and perhaps even that they are individuals with rights. However, if this was truly the case, then it would be nonsensical that an animal could be ‘owned’ as property in the same way it is morally outrageous for a human to be owned.

For these two reasons, abolitionists like Francione think that if we could wave a magic wand, we should remove all domesticated animals like cats and dogs who depend on us from existence. While we should adopt and care for the current animals that are already alive, we should also aim to abolish the institution of owning pets.

The abolitionist position is confronting and uncomfortable. I love my dog Ruby, and I was initially defensive against Francione’s argument. Has my family really been doing something wrong by pouring hours of our lives and thousands of our (my parents’) dollars into caring for a dog who we treat as a member of a family? Even if we have not personally been doing anything wrong, the world without cats and dogs that Francione envisages seems like a slightly less happy world.

I was struggling with this dilemma when my partner and I met a cat at a guesthouse in Malaysia’s Cameron Highlands, curled up in a box in the corner of the reception. When we asked the guesthouse owners what his name was, they said that he didn’t have a name yet because he only arrived three weeks earlier.

He, the cat, had picked them. In return for his company, the guesthouse owners gave him as much kibble as he would like and took him to the vet. On the same trip, I also learned that in Türkiye, many people have a ‘tab’ at the vet they use for vagabond cats who choose to live with them. This framework of domesticated animals without ‘owners’ is what I call the ‘free roaming’ model, an idea tentatively welcomed by animal studies scholar Claudia Hirtenfelder that, as Eva Meijer argues, acknowledges the agency of nonhuman animals.

Perhaps a more familiar example of a free-roaming animal is the life of the eponymous dog from the beloved Australian film, Red Dog. In the film, Red Dog is no one’s pet. Rather, he is cared for by the employees of a mine in Western Australia’s Pilbara and eventually decides to live with an American man named John Grant. Red Dog has agency, and [spoiler alert] uses that agency to travel across Australia in search of John after his premature death.

The key difference between free-roaming domesticated animals and pets is that these animals are not owned. Yes, many free-roaming cats and dogs may still depend on some human care, but they have a choice in how and from whom they receive that care.

The free-roaming model is not perfect, however. According to the Humane Society, 25% of outdoor (commonly referred to as ‘feral’) kittens do not survive past 6 months. This is not the case for kittens bred in captivity. And while some cats are lucky, like the one we met in Malaysia, many endure lives of illness and famine. And, as Korsgaard points out, domesticated cats are a predatorial threat to native wildlife, which is why, for example, they are not allowed outside without a leash in the Australian Capital Territory.

For the free-roaming model of animal companionship to work, we would have to make our urban spaces more hospitable to other animals. There would have to be a significant attitude shift in our tolerance of animals in public spaces where we usually don’t see them.

Until that day, perhaps the best thing we can do is adopt pets from shelters like the RSPCA, rather than breeders who perpetuate the institution of animal dependency and pet ownership. However, the free-roaming model gives hope for a post-pet world. As Korsgaard puts it:

“There is something about the naked, unfiltered joy that animals take in little things—a food treat, an uninhibited romp, a patch of sunlight, a belly rub from a friendly human—that reawakens our sense of the all-important thing that we share with them: the sheer joy and terror of conscious existence.”

This article won the 2024 Young Writers’ Competition 18-29 category.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture, Politics + Human Rights

Taking the cynicism out of criticism: Why media needs real critique

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

Bring back the anti-hero: The strange case of depiction and endorsement

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships, Society + Culture

You won’t be able to tell whether Depp or Heard are lying by watching their faces

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture

The Festival of Dangerous Ideas has been regrettably cancelled

BY William Salkeld

William Salkeld is a PhD candidate with the school of Politics and International Relations at the Australian National University, researching interspecies democratic theory. He is interested in animal and environmental ethics, political philosophy, animal minds and cognition, and moral philosophy.

Rethinking the way we give

Whether it’s helping out a neighbour in need, assisting a stranger living rough on the streets or being asked at the checkout to donate $2 to charity, we are all, at some point, involved in the action of giving.

The giving of service. The giving of time. The giving of money. We often find ourselves giving from a place of good intention, but not fully understanding the consequences of our actions.

Away from home, when travelling in a developing country, it’s especially difficult to ignore the begging children on the streets, families living in overcrowded homes and poverty, the absence of healthcare and the poor state of schools.

In 2006, Australian philanthropist Tara Winkler witnessed the distressing realities of children living in poverty whilst visiting a Cambodian orphanage. She was so moved that she returned a year later with money she had fundraised, ready to work hard to improve the children’s quality of life. During her time as a volunteer, she discovered that the orphanage’s director was abusive and misappropriating donations, an occurrence not unheard of in the industry. Winkler also learnt that most ‘orphans’ still had their families but were living in these institutions to escape the poverty cycle.

Attempting to save these children, Winkler established her own orphanage in 2007, only to realise it was further fueling Cambodia’s widespread misuse and exploitation of orphanages, causing harm to children and separating families. She has since developed the Cambodia Children’s Trust, an organisation that aims to address root causes of poverty and family unit breakdown through social work and locally based initiatives involving education and healthcare, providing sustainable and positive futures for at-risk communities.

By spotlighting this story, I am not aiming to discourage the act of giving but rather to motivate individuals to have a more considered approach on how we give and to whom. As highlighted in philosopher Peter Singer’s book, The Life You Can Save, ‘perhaps those who do not research think that it will be too difficult to find out what charities offer better value, so they may as well give to whatever charity last caught their eye’. This is reflected in Australia’s Giving Report from 2019, when it was recorded that 41% of Australians would donate more money in the next 12 months if they better understood where their money would be spent, whilst 23% hoped for more transparency about the cause and its regulations.

So, how can we shift these figures and guide people toward more impactful giving choices?

Let’s take a look at UNICEF. According to their Donate Where Need is Greatest appeal, of each dollar donated, 80 cents is specifically directed towards helping vulnerable children, 14 cents to essential fundraising costs and six cents to administration.

Given these figures alone, it’s difficult to assess the lasting impression of this particular campaign, so we have to look further. We discover their main goal is to break the vicious cycle of poverty by providing small initiatives that will have beneficial, long-term effects. A donation of 84 dollars equates to 84,000L of clean drinking water made accessible to some of the most at-risk children and their communities around the world. This small change results in the difference between a safe and healthy child to one who might face life-threatening illnesses through contaminated water supplies. At this point, we can gauge that donations will be properly utilised by this cause and will be incredibly significant to the lives of these children, stressing the importance of who we give to rather than a quantitative measure.

However, it’s a big ask for everyday people, simply trying to do their part, to pause and assess how their time and money could best be spent. Sometimes, it is just simpler and seems just as effective to donate to any charity that loosely relates to an ethical issue that matters most to us. To make better decisions when it comes to giving, online organisations such as The Life You Can Save and GiveWell can help evaluate and recommend high-impact, cost-effective and evidence-based charities, proving that everyone has the potential to make a meaningful impact.

By taking a few extra measures to reflect and consider where and how we direct our intentions, we can make more ethical choices that result in sustainable outcomes and give to others in a way that transforms their lives for the better.

This article won the 2024 Young Writers’ Competition Under 18s category.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture

The Festival of Dangerous Ideas has been regrettably cancelled

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

Barbie and what it means to be human

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture

Ethics programs work in practise

Big thinker

Relationships, Society + Culture

Big Thinker: Socrates

BY Serei Bayley

Serei is a 15-year-old high school student currently attending Redlands. Interested in commerce and history subjects, she has aspirations to study law or business at a university overseas. She loves travelling and spending summer days at the beach. Earlier in 2024, Serei visited Cambodia, where she was inspired by her interactions with various NGOs, which motivated her to write this piece.

Ethics Explainer: Altruism

Amelia notices her elderly neighbour struggling with their shopping and lends them a hand. Mo decides to start volunteering for a local animal shelter after seeing a ‘help wanted’ ad. Alexis has been donating blood twice a year since they heard it was in such short supply.

These are all examples, of behaviours that put the well-being of others first – otherwise known as altruism.

Altruism is a principle and practice that concerns the motivation and desire to positively affect another being for their own sake. Amelia’s act is altruistic because she wishes to alleviate some suffering from her neighbour, Mo’s because he wishes to do the same for the animals and shelter workers, and Alexis’ because they wish to do the same to dozens of strangers.

Crucially, motivation is what is key in altruism.

If Alexis only donates blood because they really want the free food, then they’re not acting altruistically. Even though the blood is still being donated, even though lives are still being saved, even though the act itself is still good. If their motivation comes from self-interest alone, then the act lacks the other-directedness or selflessness of altruism. Likewise, if Mo’s motivation actually comes from wanting to look good to his partner, or if Amelia’s motivation comes from wanting to be put in her neighbour’s will, their actions are no longer altruistic.

This is because altruism is characterised as the opposite of selfishness. Rather than prioritising themself, the altruist will be concerned with the well-being of others. However, actions do remain altruistic even if there are mixed motives.

Consider Amelia again. She might truly care for her elderly neighbour. Maybe it’s even a relative or a good family friend. Nevertheless, part of her motivation for helping might also be the potential to gain an inheritance. While this self-interest seems at odds with altruism, so long as her altruistic motive (genuine care and compassion) also remains then the act can still be considered altruistic, though it is sometimes referred to as “weak” altruism.

Altruism can (and should) also be understood separately from self-sacrifice. Altruism needn’t be self-sacrificial, though it is often thought of in that way. Altruistic behaviours can often involve little or no effort and still benefit others, like someone giving away their concert ticket because they can no longer attend.

How much is enough?

There is a general idea that everyone should be altruistic in some ways at some times; though it’s unclear to what extent this is a moral responsibility.

Aristotle, in his discussions of eudaimonia, speaks of loving others for their own sake. So, it could be argued that in pursuit of eudaimonia, we have a responsibility to be altruistic at least to the extent that we embody the virtues of care and compassion.

Another more common idea is the Golden Rule: treat others as you would like to be treated. Although this maxim, or variations of it, is often related to Christianity, it actually dates at least as far back as Ancient Egypt and has arisen in countless different societies and cultures throughout history. While there is a hint of self-interest in the reciprocity, the Golden Rule ultimately encourages us to be altruistic by appealing to empathy.

We can find this kind of reasoning in other everyday examples as well. If someone gives up their seat for a pregnant person on a train, it’s likely that they’re being altruistic. Part of their reasoning might be similar to the Golden Rule: if they were pregnant, they’d want someone to give up a seat for them to rest.

Common altruistic acts often occur because, consciously or unconsciously, we empathise with the position of others.

Effective Altruism

So far, we have been describing altruism and some other concepts that steer us toward it. However, here is an ethical theory that has many strong things to say about our altruistic obligations and that is consequentialism (concern for the outcomes of our actions).

Given that, consequentialism can lead us to arguments that altruism is a moral obligation in many circumstances, especially when the actions are of no or little cost to us, since the outcomes are inherently positive.

For example, Australian philosopher Peter Singer has written extensively on our ethical obligations to donate to charity. He argues that most people should help others because most people are in a position where they can do a lot for significantly less fortunate people with relatively little effort. This might look different for different people – it could be donating clothes, giving to charity, volunteering, signing petitions. Whatever it is, the type of help isn’t necessarily demanding (donating clothes) and can be proportional (donating relative to your income).

One philosophical and social movement that heavily emphasises this consequentialist outlook is effective altruism, co-founded by Singer, and philosophers Toby Ord and Will MacAskill.

The effective altruist’s argument is that it’s not good enough just to be altruistic; we must also make efforts to ensure that our good deeds are as impactful as possible through evidence-based research and reasoning.

Stemming from the empirical foundation, this movement takes a seemingly radical stance on impartiality and the extent of our ethical obligations to help others. Much of this reasoning mirrors a principle outlined by Singer in his 1972 article, “Famine, Affluence and Morality”:

“If it is in our power to prevent something very bad from happening, without thereby sacrificing anything morally significant, we ought, morally, to do it.”

This seems like a reasonable statement to many people, but effective altruists argue that what follows from it is much more than our day-to-day incidental kindness. What is morally required of us is much stronger, given most people’s relative position to the world’s worst-off. For example, Toby Ord uses this kind of reasoning to encourage people to commit to donating at least 10% of their income to charity through his organisation “Giving What We Can”.

Effective altruists generally also encourage prioritising the interests of future generations and other sentient beings, like non-human animals, as well as emphasising the need to prioritise charity in efficient ways, which often means donating to causes that seem distant or removed from the individual’s own life.

While reasons for and extent of altruistic behaviour can vary, ethics tells us that it’s something we should be concerned with. Whether you’re a Platonist who values kindness, or a consequentialist who cares about the greater good, ethics encourages us to think about the role of altruism in our lives and consider when and how we can help others.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Violent porn and feminism

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

The Ethics of Online Dating

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Should parents tell kids the truth about Santa?

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

The tyranny of righteous indignation

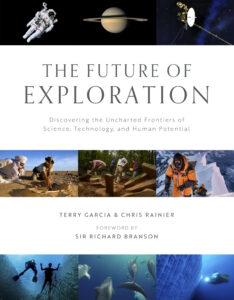

The ethics of exploration: We cannot discover what we cannot see

The ethics of exploration: We cannot discover what we cannot see

Opinion + AnalysisRelationshipsScience + Technology

BY Simon Longstaff 2 NOV 2023

For many years, I took it for granted that I knew how to see. As a youth, I had excellent eyesight and would have been flabbergasted by any suggestion that I was deficient in how I saw the world.

Yet, sometime after my seventeenth birthday, I was forced to accept that this was not true, when, at the end of the ship-loading wharf near the town of Alyangula on Groote Eylandt, I was given a powerful lesson on seeing the world. Set in the northwestern corner of Australia’s Gulf of Carpentaria, Groote Eylandt is the home of the Anindilyakwa people. Made up of fourteen clans from the island and archipelago and connected to the mainland through songlines, these First Nations people had welcomed me into their community. They offered me care and kinship, connecting me not only to a particular totem, but to everything that exists, seen and unseen, in a world that is split between two moieties. The problem was that this was a world that I could not see with my balanda (or white person’s) eyes.

To correct the worst part of my vision, I was taken out to the end of the wharf to be taught how to see dolphins. The lesson began with a simple question: “Can you see the dolphins?” I could not. No matter how hard I looked, I couldn’t see anything other than the surface of the waves and the occasional fish darting in and out of the pylons below the wharf. “Ah,” said my friends, “the problem is that you’re looking for dolphins!” “Of course, I’m looking for dolphins,” I said. “You just told me to look for dolphins!” Then came the knockdown response. “But, bungie, you can’t see dolphins by looking for dolphins. That’s not how to see. What you see is the pattern made by a dolphin in the sea.”

That had been my mistake. I had been looking for something in isolation from its context. It’s common to see the book on the table, or the ship at sea, where each object is separate from the thing to which it is related in space and time. The Anindilyakwa mob were teaching me to see things as a whole. I needed to learn that there is a distinctive pattern made by the sea where there are no dolphins present, and another where they are. For me, at least, this is a completely different way of seeing the world and it has shaped everything that I have done in the years since.

This leads me to wonder about what else we might not see due to being habituated to a particular perspective on the world.

There are nine or so ethical lenses through which an explorer might view the world. Each explorer will have a dominant lens and can be certain that others they encounter will not necessarily see the world in the same way. Just as I was unable to see dolphins, explorers may not be able to see vital aspects of the world around them—especially those embedded in the cultures they encounter through their exploration.

Ethical blindness is a recipe for disaster at any time. It is especially dangerous when human exploration turns to worlds beyond our own. I would love to live long enough to see humans visiting other planets in our solar system. Yet, I question whether we have the ethical maturity to do this with the degree of care required. After all, we have a parlous record on our own planet. Our ethical blindness has led us to explore in a manner that has been indifferent to the legitimate rights and interests of Indigenous peoples, whose vast store of knowledge and experience has often either been ignored or exploited.

Western explorers have assumed that our individualistic outlook is the standard for judgment. Even when we seek to do what is right, we end up tripping over our own prejudice. We have often explored with a heavy footprint or with disregard for what iniquities might be made possible by our discoveries.

There is also the question of whether there are some places that we ought not explore. The fact that we can do something does not mean that it should be done. Inverting Kant’s famous maxim that “ought implies can,” we should understand that can does not imply ought! I remember debating this question with one of Australia’s most famous physicists, Sir Mark Oliphant. He had been one of those who had helped make possible the development of the atomic bomb. He defended the basic science that made this possible while simultaneously believing that nuclear weapons are an abomination. He put it to me that science should explore every nook and cranny of the universe, as we can only control what is known and understood. Yet, when I asked him about human cloning, Oliphant argued that our exploration should stop at the frontier. He could not explain the contradiction in his position. I am not sure anyone has yet clearly defined where the boundary should lie. However, this does not mean that there is no line to be drawn.

So how should the ethical landscape be mapped for (and by) explorers? For example, what of those working on the de-extinction of animals like the thylacine (Tasmanian tiger)? Apart from satisfying human curiosity and the lust to do what has not been done before, should we bring this creature back into a world that has already adapted to its disappearance? Is there still a home for it? Will developments in artificial intelligence, synthetic biology, gene editing, nanotechnology, and robotics bring us to a point where we need to redefine what it means to be human and expand our concept of personhood? What other questions should we anticipate and try to answer before we traverse undiscovered country?

This is not to argue that we should be overly timid and restrictive. Rather, it is to make the case for thinking deeply before striking out, for preparing our ethics with as much care as responsible explorers used to give to their equipment and stores.

The future of exploration can and should be ethical exploration, in which every decision is informed by a core set of values and principles. In this future, explorers can be reflective practitioners who examine life as much as they do the worlds they encounter. This kind of exploration will be fully human in its character and quality. Eyes open. Curious and courageous. Stepping beyond the pale. Humble in learning to see—to really see—what is otherwise obscured within the shadows of unthinking custom and practice.

This is an edited extract from The Future of Exploration: Discovering the Uncharted Frontiers of Science, Technology and Human Potential. Available to order now.

BY Simon Longstaff

After studying law in Sydney and teaching in Tasmania, Simon pursued postgraduate studies in philosophy as a Member of Magdalene College, Cambridge. In 1991, Simon commenced his work as the first Executive Director of The Ethics Centre. In 2013, he was made an officer of the Order of Australia (AO) for “distinguished service to the community through the promotion of ethical standards in governance and business, to improving corporate responsibility, and to philosophy.”

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

The self and the other: Squid Game’s ultimate choice

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Ask me tell me: Why women think it’s ok to lie about contraception

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Science + Technology

With great power comes great responsibility – but will tech companies accept it?

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

The role of emotions in ethics according to six big thinkers

Moral intuition and ethical judgement

By checking in to our intuitions and using them to inform our judgements, we can come up with decisions that make sense, but also feel right.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

It’s easy to ignore the people we can’t see

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

What ethics should athletes live by?

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Ethics

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Would you kill one to save five? How ethical dilemmas strengthen our moral muscle

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

What is the difference between ethics, morality and the law?

What is the difference between ethics, morality and the law?

WATCHRelationships

BY The Ethics Centre 1 NOV 2023

The world around us is a smorgasbord of beliefs, claims, rules and norms about how we should live and behave.

It’s important to tease this jumble of ethical pressures apart so we can put them in their proper place. Otherwise, it can be hard to know what to do when some of these requirements contradict others. Let’s talk about three different categories of demands on how we should live: ethics, morality and law.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Free markets must beware creeping breakdown in legitimacy

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Women must uphold the right to defy their doctor’s orders

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Narcissists aren’t born, they’re made

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

In two minds: Why we need to embrace the good and bad in everything

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Virtue ethics

What makes something right or wrong?

One of the oldest ways of answering this question comes from the Ancient Greeks. They defined good actions as ones that reveal us to be of excellent character.

What matters is whether our choices display virtues like courage, loyalty, or wisdom. Importantly, virtue ethics also holds that our actions shape our character. The more times we choose to be honest, the more likely we are to be honest in future situations – and when the stakes are high.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships

The transformative power of praise

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Why morality must evolve

WATCH

Relationships

Purpose, values, principles: An ethics framework

WATCH

Relationships

Moral intuition and ethical judgement

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Deontology

What makes something right or wrong?

One answer comes from the work of German philosopher Immanuel Kant, who is considered the founder of an ethical theory called deontology. Deontology comes from the Greek word deon, meaning duty. It holds, quite simply, that actions are good or bad based on whether they fulfil universal moral duties.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships, Science + Technology

Parent planning – we shouldn’t be allowed to choose our children’s sex

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships

So your boss installed CCTV cameras

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

Where are the victims? The ethics of true crime

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture, Relationships

Whose fantasy is it? Diversity, The Little Mermaid and beyond

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Consequentialism

For lots of people, what makes a decision right or wrong depends on the outcome of that decision.

Does it increase or decrease the amount of happiness in the world? This kind of thinking is typical of consequentialism: an ethical school of thought that says what makes an action good or bad is, you guessed it, the consequences.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

The niceness trap: Why you mustn’t be too nice

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships, Science + Technology

Hallucinations that help: Psychedelics, psychiatry, and freedom from the self

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

It’s easy to ignore the people we can’t see

Big thinker

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships