Tips on how to find meaningful work

Tips on how to find meaningful work

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + LeadershipHealth + Wellbeing

BY The Ethics Centre 1 MAR 2017

“Find a job you’ll love and you’ll never work a day in your life!” There are different claims about who coined this phrase but it’s stood the test of time. Like most one-liners, it’s easier said than done.

Most people need two things from their work. They need to earn enough to support all the other areas of their life and they need to feel dignified while doing it. Neither is an easy find.

We tend to know how much income we need but a sense of dignity and meaning can be elusive. You might want creative output, a good work/life balance or a sense of achievement earned through a ‘hard day’s work’. It’s easier to know what kind of work will suit you if you’ve taken Socrates’ advice: know thyself.

Still, insights from philosophy and psychology can help us spot some of the things that tend to give people a sense of meaning in their jobs.

You’ve gotta want it

This is the basic idea behind the ‘find a job you love’ proverb. If you’re doing something you enjoy, it won’t feel like a chore. If you’re motivated by income, prestige or something external, it will be hard to find the work itself fulfilling.

The philosopher Bernard Williams distinguishes ‘internal’ and ‘external’ motivations. We have an external motivation to do something if it would be good for us to do it, whether we want to or not. Internal motivations are things we personally want to do.

For example, if we’re sick, it is good for us to take medicine – that’s an external motivation. If we actually want to get better, we’ve also got an internal motivation. If we want a few more days off work, there’s no internal motive to get better, even though being healthy is better than being sick, generally speaking.

Williams thought external motivations alone couldn’t make us do something. We need some internal motivators to get us off the couch. Williams might not be right. Lots of people probably show up to work because they need to make ends meet but there’s still a lesson in his distinction. Salaries, prestige or fringe benefits won’t be enough to give us a lasting sense of meaning – we need to feel personally engaged with what we’re doing.

Look beyond official duties

Sometimes the core activities of our work won’t give us internal motivation. It might be some unofficial role our job enables us to fulfil.

Psychologist Barry Schwartz uses the example of Luke, a hospital janitor (his official title was “hospital custodian”). It’s unlikely Luke wakes up passionate about working light bulbs and shiny urinals. He found meaning in the parts of his work that extended beyond his official duties:

“The researchers asked the custodians to talk about their jobs, and the custodians began to tell them stories about what they did. Luke’s stories told them that his “official” duties were only one part of his real job, and that another central part of his job was to make the patients and their families feel comfortable, to cheer them up when they were down, to encourage them and divert them from their pain and fear, and to give them a willing ear if they felt like talking.”

The meaningful work Luke performed sat outside he things the hospital paid him for. Despite this, it still gave him enough satisfaction to keep showing up.

See your role in the bigger picture

Hospital janitors are a font of wisdom. Schwartz also describes how Ben and Corey, also janitors, found meaning. They recognised their role within the broader purpose of the hospital – to provide care for people who need it:

“Luke, Ben, and Corey were not generic custodians. They were hospital custodians. They saw themselves as playing an important role in an institution whose aim is to see to the care and welfare of patients.”

They would stop mopping floors if patients were walking the corridors for rehab or hold off from vacuuming when family were sleeping in the patient lounge. They weren’t just keeping things tidy and in working order. In a hospital, cleanliness staves off infection and can save lives. The context and purpose of their work gave it new meaning.

Find space for choice

Peter Cochrane, entrepreneur and technologist, thinks many jobs are taking what’s human out of their human employees. In the documentary The Future of Work and Death, he says, “When I go into companies I often ask the question, ‘Why are you employing people? You could get monkeys or robots to do this job.’ The people are not allowed to think – they are processing. They’re just like a machine.”

At an absolute minimum, feeling dignified at work means feeling like our humanity is being recognised. We want to be treated as people, not things. It’s important we find spaces in our work where we can be autonomous: making decisions for ourselves, exercising our creativity and asserting our ability to think freely.

It’s not a perfect fix

We must acknowledge the limitations of this advice. Our basic needs for food, housing, and the rest require many of us to persevere with work we find undignifying or meaningless.

But if you’re lucky enough to enjoy some choice in where you work and are unhappy in your current role, take a second to think – are you missing one of the above? At least you’ll know what to look for next time!

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

An ethical dilemma for accountants

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

United Airlines shows it’s time to reframe the conversation about ethics

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Sylvie Barbier and Rufus Pollock on failure and fostering a wiser culture

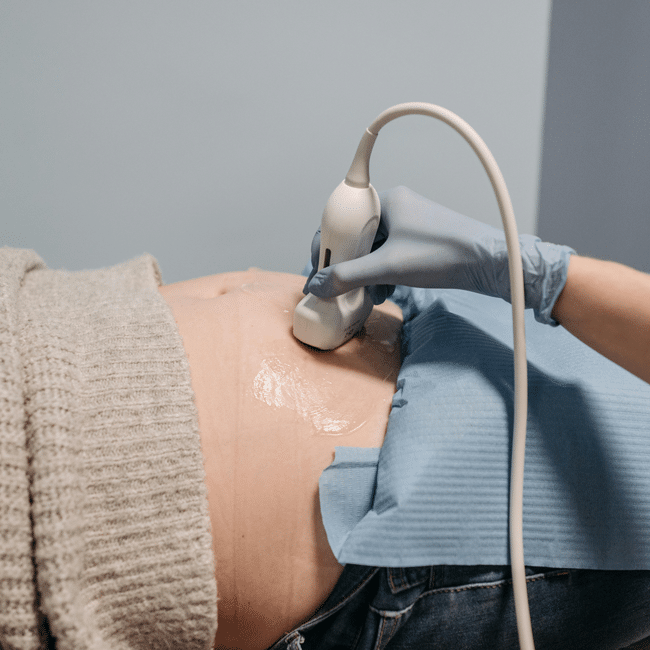

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships, Science + Technology

Periods and vaccines: Teaching women to listen to their bodies

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

5 ethical life hacks

5 ethical life hacks

Opinion + AnalysisHealth + WellbeingRelationships

BY The Ethics Centre 11 JAN 2017

It’s not all tough decisions – walking, sleeping and reading are some ways you can seamlessly strengthen your ethical muscles every day. Here are some activities that can help refine your ethics while you’re busy in your day-to-day life.

Get back to nature

Aristotle believed everything in nature contains “something of the marvellous”. It turns out nature might also help make us a bit more marvellous. Research by Jia Wei Zhang and colleagues revealed how “perceiving natural beauty” (basically, looking at nature and recognising how wonderful it is) can make you more prosocial. Specifically, it can make you more helpful, trusting and generous. Nice one, trees.

The apparent reason for this is because a connection with nature leads to heightened positive emotions. People are happier when they are connected with nature and other research suggests happy people tend to be more prosocial. Inadvertently, as Zhang and his colleagues learned, this means nature helps make us better team players.

Read literature to develop ‘Theory of Mind’

In psychology, ‘Theory of Mind’ refers to the ability to understand the emotions, intentions and mental states of other people and to understand that other people’s mental states are different from our own, which is a crucial component of empathy. Like most things, our Theory of Mind improves with practice.

David Comer Kidd and Emanuele Castano think one way of practising and developing Theory of Mind is by reading literary fiction. They believe literature “uniquely engages the psychological processes needed to gain access to characters’ subjective experiences” because it doesn’t aim to entertain readers but challenge them.

Work up a sweat

As well as the health benefits it brings, exercise can make you a more virtuous person. Philosopher Damon Young believes exercise brings about “subtle changes to our character: we are more proud, humble, generous or constant”.

Pride is usually seen as a vice but exercise can give us a healthy sense of pride, which Young defines as “taking pleasure in yourself”. Taking pleasure in ourselves and recognising ourselves as valuable has obvious benefits for self-esteem, but it also gives us a heightened sense of responsibility. By taking pride in the work we’ve invested in ourselves, we acknowledge the role we have making change in the world, a feeling with applications far broader than the gym.

Take meal breaks when you’re making decisions

In 2011, an Israeli parole board had to consider several cases on the same day. Among them were two Arab-Israelis, each of them serving 30 months for fraud. One of them received parole, the other didn’t. The only difference? One of their hearings was at the start of the day, the other at the end.

Researcher Shai Danzigner and co-authors concluded “decision fatigue” explained the difference in the judges’ decisions. They found the rate of favourable rulings were around 65% just after meal breaks at the start of the day and lunch time, but they diminished to 0% by the end of the session.

There’s some good news though. The research suggests a meal break can put your decision making back on track. Maybe it’s time to stop taking lunch at your desk.

Get a good night’s sleep

We’ve been starting to pay more attention to the social costs of exhaustion. In NSW, public awareness campaigns now list fatigue as one of the ‘big three’ factors in road fatalities alongside speeding and drunk driving. It turns out even if it doesn’t kill you, exhaustion can lead to ethical compromises and slip ups in the workplace.

In 2011, Christopher Barnes and his colleagues released a study suggesting “employees are less likely to resist the temptation to engage in unethical behaviour when they are low on sleep”. When we’re tired we experience ‘ego depletion’ that weakens our self-control. Experiments conducted by Barnes’ team suggest when we’re tired we’re vulnerable to cutting corners and cheating. So, if you’re thinking of doing something dodgy, sleep on it first.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Why have an age discrimination commissioner?

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Our desire for reality: What OnlyFans says about sexual fantasy

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

How to respectfully disagree

Opinion + Analysis

Climate + Environment, Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

The dilemma of ethical consumption: how much are your ethics worth to you?

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Ethics from the couch: 5 shows to binge on

Ethics from the couch: 5 shows to binge on

Opinion + AnalysisHealth + Wellbeing

BY The Ethics Centre 4 JAN 2017

Study! Relax!

¿Por qué no los dos?

In the spirit of the Old El Paso school of philosophy, here are five TV shows you can binge watch that will also get you thinking a little about ethics. Quick warning: there are some minor spoilers below.

1. UnREAL

We’re not going to suggest you go back and watch The Bachelor or Survivor Australia (you probably watched them the first time around). Check out UnREAL instead. It’s a fictional look at the thorny ethics of reality TV based around the producers of Everlasting, which is The Bachelor in pretty much everything but name.

<

It’s easy to watch reality TV and assume the people appearing on the shows are fair game for criticism because they signed up to appear on the program. What’s easily forgotten – until you watch UnREAL – is the manipulation undertaken by producers to create drama and ‘good’ television. In season 1, a contestant kills herself as a result of this kind of manipulation, which only sparks higher ratings.

2. Offspring

If you’ve never watched Offspring, you’ve got a lot to catch up on. The feel-good Aussie sitcom was rebooted for a fifth season in 2016 and brought with it a thorny bioethics conundrum: who has the right to a dead man’s sperm?

Offspring centres around Nina Proudman and her family, and also deals with the fallout from the sudden death of Patrick, Nina’s fiancé and father of her daughter. Unknown to Nina, Patrick had some of his sperm frozen during a previous marriage. His ex-wife decides to offer Nina his sperm, in case she would like to have another child to him.

Does Nina have any right to use Patrick’s sperm? Does his ex-wife have any right to offer it to Nina? Patrick donated before he was in a relationship with Nina and we have no idea what his wishes would be for children in the event of his death. How can we respect his wishes in this case?

3. Black Mirror

This isn’t the first time we’ve discussed Black Mirror: Patrick Stokes explored the themes of one episode in his piece on digital death. Black Mirror doesn’t follow a season-long narrative. It’s a bunch of standalone dramas exploring themes around technology, the future and humanity. It can be pretty dystopian but does encourage us to think twice about where today’s technology might be headed.

One episode that hits close to home is “Hated in the Nation”, which has a detective who investigates the deaths of young people subjected to online shaming and social media pile ons. Just because we don’t see the consequences of a mean tweet or aggressive comment, it doesn’t mean we’re not responsible for them.

4. The Good Place

One for the philosopher nerds among us! When Eleanor Shellstrop is killed by a trailer advertising erectile dysfunction drugs, she finds herself in the afterlife. Everything is perfect except Eleanor herself. It turns out the hard-drinking, foul-mouthed woman was meant to go to “the bad place” but a clerical error worked in her favour.

Eleanor enlists the help of her allocated ‘soul mate’ Chidi, who was an ethics professor on earth. He proceeds to help her to reform, teaching her about Kant, Aristotle and the rest. The show basically functions as an introduction to moral philosophy for both Eleanor and viewers, but manages to sneak in a few decent jokes along the way.

5. Cleverman

Mythology and traditional stories have always been good fodder for film and television, so it’s a little surprising Aboriginal stories have been so absent from Australian screens. Ryan Griffen was aware of this absence and wanted to create an Aboriginal superhero for his son. The end product was Cleverman, a dystopian sci-fi series about the Hairypeople – an Indigenous race who live for hundreds of years, have extraordinary strength and grow thick pelts across their body.

The “Hairies” are seen as subhuman, rounded up and kept in a separate part of society called the Zone. The spiritual leader of the Zone is the Cleverman, whose powers include bringing people back from the dead. Cleverman follows a range of narratives around the internal politics of the Zone and the broader social structures that continue to oppress Hairypeople.

What’s important about Cleverman is both its representation, putting Aboriginal faces at the centre of a world based in Dreamtime stories, and the ability – like all sci-fi – to take pressing social issues and explore them in a fictional world.

Questions around Aboriginal identity in the broader Australian community, social attitudes to ‘otherness’, black deaths at the hands of white police officers and the militarisation of government departments are all explored.

You are more than your job

You are more than your job

Opinion + AnalysisHealth + WellbeingRelationships

BY Simon Longstaff The Ethics Centre 20 DEC 2016

There are many ways we define our personal identity. Often, we define it by the roles we play in life.

We might think of ourselves as a child, parent, sibling, spouse, lover, friend… It is remarkable how we integrate all these different roles and relationships into our own, singular person.

People may often identify themselves according to their work. It’s been happening throughout history, as we can hear in occupational surnames such as Carpenter, Carter, Baker and Wheeler. We even link our identity with what we do for bureaucratic reasons. For example, every traveller is required to state their occupation when departing from or arriving in Australia.

Personal value has shifted focus from our character, personality, and relationships, to our role or place in society. It is no longer a question of who we are but what we do.

Casual conversations, too, eventually veer towards the question, “what do you do?” But a few years ago, I noticed the response to the question “How are you?” was changing from “I’m well” to “I’m busy”. I wondered what lay behind this altered response. What were they trying to say?

I concluded that the words “I am busy” are a proxy for “I am valued/needed”. My worth is affirmed by the fact I am in demand to the point of being busy.

If I’m correct, this marks a subtle but important change. Personal value has problematically shifted focus from our character, personality and relationships to our role or place in society. It is no longer a question of who we are but what we do.

Perhaps we should reflect on some of the deeper questions to do with identity, meaning and value.

For the most part, we might not notice this change in emphasis. However, if what I suspect is true, a holiday such as the enforced Christmas vacation could be a period of stress and dislocation for people who define themselves by their work – especially if they live alone and are without family or friends.

For some people, a job is not only a source of identity, it may also be their principal social environment, providing a regular opportunity for human contact. For such people, being deprived of this context can be a profound loss. To be ‘on leave’ is to be cut off from their principal source of identity.

Those of us with established social networks could help by reaching out to such people and making sure they’re included in holiday celebrations. Among other things, this sends a signal that the person is valued for more than their work.

Work-focused individuals could also volunteer with charities during the holiday season. This would provide a readymade social context and a valuable, alternative source of meaning and identity.

However, especially at Christmas time, perhaps we should reflect on some of the deeper questions dealing with identity, meaning and value. At the heart of ethics is a belief in the intrinsic worth of every person – irrespective of their gender, race, religion, sexuality… or job.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Climate + Environment, Health + Wellbeing, Society + Culture

Melbourne Cup: The Ethical Form Guide

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Enwhitenment: utes, philosophy and the preconditions of civil society

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

What I now know about the ethics of fucking up

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Politics + Human Rights

Disease in a Time of Uncertainty

BY Simon Longstaff

Simon Longstaff began his working life on Groote Eylandt in the Northern Territory of Australia. He is proud of his kinship ties to the Anindilyakwa people. After a period studying law in Sydney and teaching in Tasmania, he pursued postgraduate studies as a Member of Magdalene College, Cambridge. In 1991, Simon commenced his work as the first Executive Director of The Ethics Centre. In 2013, he was made an officer of the Order of Australia (AO) for “distinguished service to the community through the promotion of ethical standards in governance and business, to improving corporate responsibility, and to philosophy.” Simon is an Adjunct Professor of the Australian Graduate School of Management at UNSW, a Fellow of CPA Australia, the Royal Society of NSW and the Australian Risk Policy Institute.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

The etiquette of gift giving

The etiquette of gift giving

Opinion + AnalysisHealth + WellbeingRelationships

BY Ruth Quibell The Ethics Centre 14 DEC 2016

I enjoy giving gifts, especially for my children. It’s an opportunity to think about them, who they are now and how they’re developing.

I want the gift I choose to be liked by the person who receives it but I also expect it to do other things. Does this gift tell them they are understood? Loved? Appreciated? Does it reflect our relationship? It’s a bit of a gamble and is easy to get wrong, which is why I’m often a little freer with spending my money and time on a gift than I am usually.

This deeply personal way of thinking about gifts isn’t unusual but it overlooks the shared, ritualised aspects of gift exchange. In childhood we learn a polite dance of expectation and obligation. Even though gift-giving is meant to be spontaneous and honest, it follows a predictable script of performed generosity and gratitude.

In Brooklyn Nine-Nine, the dramatic Gina offers a great example of this. She secretly opens all her presents in advance so she can rehearse her ‘opening’ expressions for later.

A gift might be given freely and without coercion, but it doesn’t come without basic obligations for the receiver of the gift: to accept the gift, to express gratitude, to reciprocate. While a gift might express or help reinforce a relationship, the giver’s intention alone is no guarantee of success.

‘Charity gifts’ like providing clean water for a community overseas are undoubtedly well motivated, but do they serve the same purpose as traditional gift giving?

The rise of ‘charity gifts’ interrupts our usual expectations of a gift as an exchange between two people or families that is motivated by a relationship. Interestingly, by donating money to a charity in another’s name the ordinary social expectations of giving are preserved. The relationship between giver and the nominal recipient of the gift might even be bolstered without any tangible exchange occurring between them.

The ultimate recipient of the gift might benefit from it but they are receiving anonymous charity rather than a gift. You might even argue that they are part of the gift being given. For those considering ‘charity gifts’, it’s worth asking: what are you giving, to who, and why?

You’re unwrapping a present, surrounded by family when you unveil the most garish, knitted socks from great Aunty Mavis. Do you have to keep them? Are you obliged to wear them?

This situation makes the tacit expectations around how to receive gifts more overt. We don’t know much about great Aunty Mavis’s motivations. She might have simply enjoyed knitting the socks and have little interest in our feelings about them. The situation requires what sociologist David Ekerdt calls an “act of reception”. Without it, Mavis’s gift giving gesture will hang in the air like an unshaken hand.

A common response, I suspect, to avoid an uncomfortable situation would be to graciously accept the gift without giving offence, and then to quietly dispose of it later. Think Colin Firth’s character wearing the Christmas themed jumper in Bridget Jones.

Of course, there’s a choice here. I’d probably put the socks on immediately and see what I could discover about them and myself, but I wouldn’t pretend to like them if I didn’t.

Children are often encouraged to write ‘Christmas lists’ and send them to Santa. Later in life, lots of people are explicit in the gifts they want to receive for Christmas or birthdays. Do these trends encourage us to think about gift giving in a different way?

As I write this, my almost eight year old has stuck a sizeable birthday list on the fridge. She wants these things but she also wants me to understand her. Her list is an attempt to ensure I don’t get her wrong. The list is important, but as her parent I don’t only want to give her the things she wants. This is where gifts differ from simply an exchange of money for goods in the market. Gifts entail risky choices and unpredictable receptions.

It feels as though there’s a tension between the act of giving a gift itself, which is an act of generosity, and the general climate of the season, which seems more self-interested. Is that tension inescapable?

Gift giving usually has a dose of both. We give because we want to, but also because we expect something in return. Even if we don’t expect the straightforward exchange of a gift in return, we might hope for a stronger relationship, to be held high in someone’s opinion, or simply to be appreciated as kind, thoughtful or generous.

To be clear, this is not the same variety of self-interest as the stereotypical selfish consumer always hungry for more. It’s self-interest, yet I don’t think there’s anything particularly wrong in wanting our lives to be good with caring relationships. Perhaps when it comes to choosing a gift, we don’t need to be so quick to disown having a pinch or two of self-interest in the gift-giving game. It might even lead to a better choice of gift than great Aunty Mavis’s socks.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

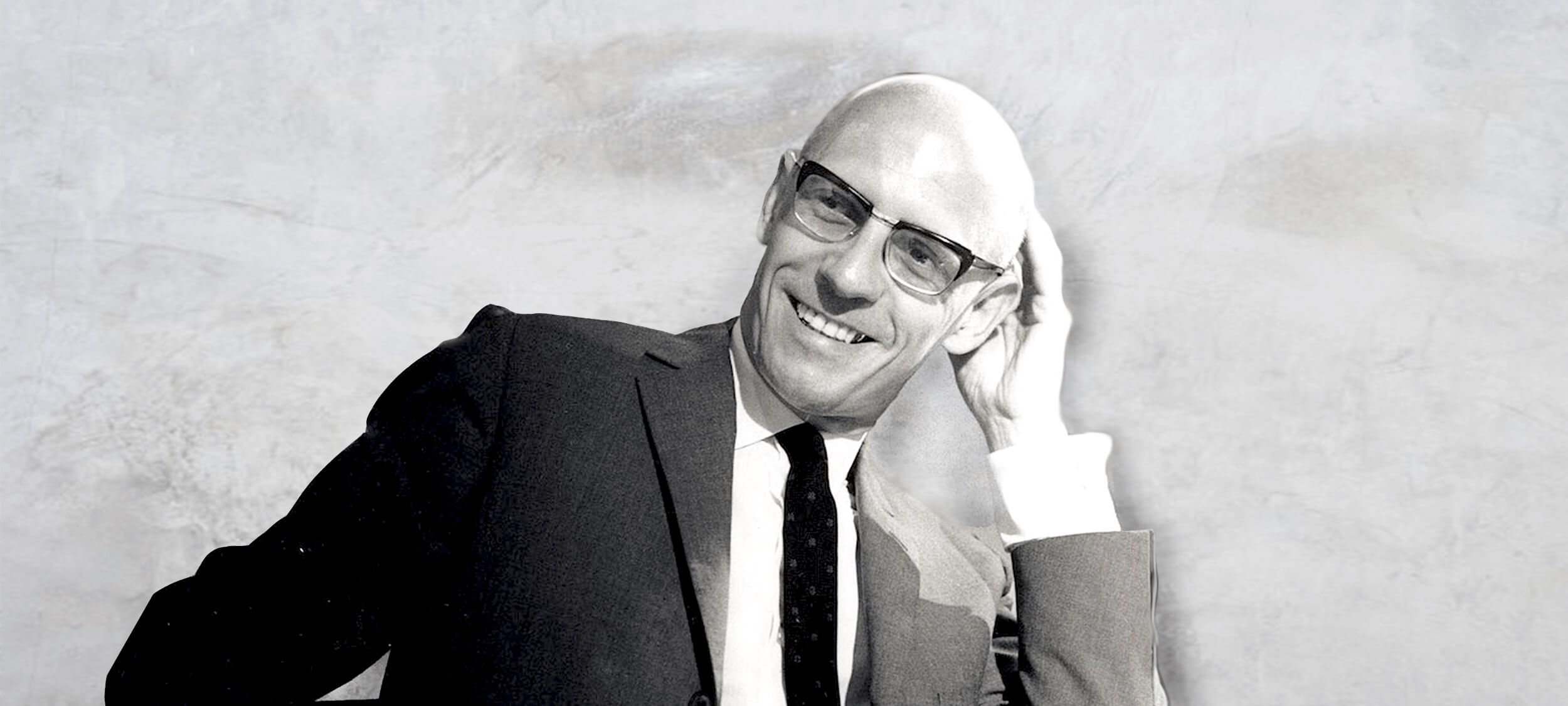

Big thinker

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Big Thinker: Michel Foucault

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Enough with the ancients: it’s time to listen to young people

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Science + Technology

The ethics of exploration: We cannot discover what we cannot see

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Teleology

BY Ruth Quibell

Ruth Quibell is a sociologist based in Melbourne. Her most recent book is The Promise of Things.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Confirmation bias: ignoring the facts we don’t fancy

Confirmation bias: ignoring the facts we don’t fancy

Opinion + AnalysisHealth + WellbeingRelationships

BY John Neil The Ethics Centre 7 DEC 2016

We all like to believe we’re careful thinkers who gather and evaluate facts before making a decision. Unfortunately, we’re not.

We tend to seek information we find favourable and which supports what we already think. In short, we reach a conclusion first, then test it against evidence, rather than gather evidence first and evaluate it to make a conclusion.

This is called confirmation bias, which is a type of cognitive bias (like the bandwagon effect, or the availability heuristic) in which we tend to notice or search out information that confirms what we already believe or would like to believe. To avoid the discomfort of finding information that doesn’t support our views or ideas, we will discount or disregard evidence that’s contrary to our beliefs or preferences.

This plays out in similar ways across a range of contexts. In the sciences, theories are developed through falsifying and supporting evidence. Researchers need to recognise their own potential confirmation biases that come with holding a strong view or belief in the face of other evidence.

Confirmation bias plays out both in a range of research disciplines and our everyday decision making. When we research brands or products we tend to seek out information that reinforces our tastes and preferences. For instance, being drawn to reviews favouring brands we already like.

Confirmation bias is also at play in more significant life decisions like superannuation and other investment choices. Often, the greater the significance of a decision, the greater the likelihood that confirmation bias will be in play. If we don’t want to be left behind when we hear friends or colleagues talking about how well an investment is doing, our research will be strongly influenced by the story of our friend’s success. In doing so, we may filter out information that raises red flags and instead focus on the information validating the investment.

Our technology comes full with confirmation bias. Social media news feeds and online sources are ready made filters of information from people who think like us. Paradoxically, the tools and technologies that make information so accessible heighten the likelihood of us being drawn into information loops which reinforce what we think we know. As Warren Buffett famously remarked, “What the human being is best at doing is interpreting all new information so that their prior conclusions remain intact”.

Like several other biases, confirmation biases are an example of ‘motivated reasoning’. Motivated reasoning describes how our judgments are consciously and unconsciously influenced by what we think we know. This shapes how we think about our health, our relationships, how we decide how to vote and what we consider fair or ethical.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Society + Culture

Does ethical porn exist?

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Why learning to be a good friend matters

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

A critical thinker’s guide to voting

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Climate + Environment, Relationships

ESG is not just about ticking boxes, it’s about earning the public’s trust

BY John Neil

As Director of Education and Innovation at The Ethics Centre, John collaborates closely with a talented team of specialists and subject matter experts to shape the tools, frameworks, and programs that drive our work forward. He brings a rich and varied background as a consultant, lecturer, and researcher, with expertise spanning ethics, cultural studies, sustainability, and innovation. This multidisciplinary perspective allows him to introduce fresh, thought-provoking approaches that energise and inspire our initiatives. John has partnered with some of Australia’s largest organisations across diverse industries, to place ethics at the heart of organisational life. His work focuses on education, cultural alignment, and leadership development to foster meaningful and lasting impact.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Ask me tell me: Why women think it’s ok to lie about contraception

Ask me tell me: Why women think it’s ok to lie about contraception

Opinion + AnalysisHealth + WellbeingRelationships

BY The Ethics Centre 6 DEC 2016

‘Ask Me, Tell Me’ is a series created by you. You told us what you want to talk about by contributing your thoughts to an interactive artwork at the Festival of Dangerous Ideas.

This week: what happens to sex when people can’t trust each other? We look at the ethics and politics of sex.

Sexual ethics is prickly business. For the sake of exploring your contribution dear FODI patron, let’s assume you’re a man who has been lied to by a now pregnant woman who said she couldn’t conceive because she was using contraception.

Speaking of assumptions, it’s easy to assume our personal experiences are common, particularly big, life-changing ones like this. Experience is after all the key learning module in the school of life. But an assessment of the world based on our own experiences or one-off things we see, no matter how prominently they feature in our lives, is not exactly objective (although it’s a common cognitive bias we all can slip into).

Seeing ‘women’ as a group who lie to get pregnant isn’t a fair assessment of all women. Like every other group in society that shares some sort of common ground, women don’t think the same way or collectively decide what’s ethical and what’s not.

Also, there’s not much evidence to support this being a common practice of women other than a poll by That’s Life! magazine.

Nevertheless, none of this is to deny what we’re assuming has happened to you. It’s just pointing out it’s unlikely to be a prevalent phenomenon.

…men could choose to have no legal rights or responsibilities to a child as a way of correcting the alleged power imbalance in which men are held accountable as parents even if they would have preferred a pregnancy be terminated.

Whether or not it’s common for women to fib about using contraception to get pregnant doesn’t change the extent to which you must feel betrayed, trapped, angry and lied to. You’re facing the prospect of a lifelong commitment you believed wasn’t on the cards. Can anything be done about it?

There are a couple of ways to prevent others from finding themselves in the same situation. A Swedish group recently campaigned to give men the right to ‘legally abort’ from children. Under the proposal, men could choose to have no legal rights or responsibilities to a child as a way of correcting an alleged power imbalance that holds men accountable as dads even if they never wanted to be one.

‘Legal abortions’ don’t seem to actually be legal anywhere in the world but the argument in favour of them is that they level the playing field. Many of course would see women as the ones bearing more of the challenges of unwanted pregnancies than men, given they’re the ones who have to carry and give birth to the child.

Nevertheless, ‘legal abortions’ is an idea several thinkers, often women, have been discussing for a while.

Sex is risky – not only because of the possibility of children or infection – but because it leaves us physically and emotionally vulnerable.

An easier option would be for men to take contraception into their own hands. Condoms have been available for a long time. They’re 98% effective, prevent sexually transmitted infections and tend to be cheaper than female methods. And in years to come, a male contraceptive pill may well be available – a promising trial study of a male pill was abandoned due to side effects.

However, trust has become an issue here as well, with some women not having faith in men to take care of contraception. The Guardian columnist Barbara Ellen describes this as “the relentless howl of distrust between the sexes, echoing down the years”. Perhaps the best solution is one in which both men and women use contraception.

In many ways, this is a neat solution but can we really use technology as a substitute for sexual trust? Or, if men and women are doomed to distrust one another as Ellen suggests, what are the consequences of sex without trust? We trust sexual partners to use protection and contraception. We trust them to be concerned for our pleasure as well as theirs, to recognise our boundaries and seek our consent before doing anything to us or demanding anything from us, to respect our privacy and so on. At the heart of all of this is the understanding that sex is risky – not only because of the possibility of babies and infection – but because it leaves us physically and emotionally vulnerable.

Philosopher LA Paul describes becoming a parent as a ‘transformative experience’ – an experience that changes who we are so fundamentally it’s impossible to know whether the person we will become will regret our decision or not.

None of this gives you, FODI punter, much to go on with. You’ve been lied to, you’re facing long term consequences as a result and now you have to choose what kind of parent you want to be. And because you were lied to you’ve been put in this position unjustly and against your will, which is wrong by almost any measure.

Unfortunately, you still have to decide what to do. Philosopher LA Paul describes becoming a parent as a ‘transformative experience’ – an experience that changes who we are so fundamentally it’s impossible to know whether the person we will become will regret our decision or not. By definition, we can’t know what the right thing to do is.

Paul thinks this is true for all parents, not just those facing unwanted pregnancies. Even though there’s not much guidance on what you should do in this situation, it might be reassuring to know every potential parent is facing the same impossible decision. In the end, Paul suggests the best way to make this decision is to base it on what we want to discover, not what we think we’d enjoy.

And if you’re still stuck, you can always contact Ethi-call – The Ethics Centre’s free helpline – where you can speak with one of our counsellors to help make a decision aligned with your own values, principles and conscience.

Follow The Ethics Centre on Twitter, Facebook and Instagram.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Explainer

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Power

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

The ANZAC day lie

Explainer

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Dignity

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Would you kill baby Hitler?

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Ethics Explainer: Hedonism

Hedonism is a philosophy that regards pleasure and happiness as the most beneficial outcome of an action. More pleasure and less pain is ethical. More pain and less pleasure is not.

What is hedonism?

Hedonism is closely associated with utilitarianism. Where utilitarianism says ethical actions are ones that maximise the overall good of a society, hedonism takes it a step further by defining ‘good’ as pleasure.

There are different perspectives on what pleasure and pain really mean. For Epicurus, the ancient Greek philosopher, pleasure was the absence of pain. Though his name has become synonymous with indulgence – “Epicurean holidays”, a food app called “Epicurious” – he advocated finding pleasure in a simple life with a bland diet.

If we live a rich, complex lifestyle we risk suffering more when it ends. Best not to love them to begin with, he suggests.

John Stuart Mill believed in a hierarchy of pleasures. Although sensory pleasures might be the most intense, it was fitting for higher order beings – like humans – to enjoy higher order pleasures – like art. “It is better to be Socrates dissatisfied than a pig satisfied”, he said. (With evidence to suggest pigs can orgasm for up to fifteen minutes, Mill’s account feels a little incomplete).

Most people will agree pleasure and pain are important for determining the value of something. That’s not enough to make you a hedonist. What makes hedonism unique is the claim only pleasure and pain matter. That’s where people tend to be more hesitant.

The experience machine

The philosopher Robert Nozick wanted people to feel the pinch of measuring life only based on pain and pleasure. He developed a thought experiment called the experience machine.

Imagine a machine that can plug into your brain and simulate the most pleasurable life you could imagine. It would respond to your specific desires – you could be a rock star, philosopher or space cowboy depending on what was most pleasurable. But if you plugged in, you could never unplug. Plus, although you’d feel as though you were experiencing amazing things, you’d be floating in a vat, feeding through a tube.

Nozick thought most people would choose not to plug into the machine – proving there was more to life than pleasure and pain. But Nozick’s argument depends on people’s lives being of a certain quality. It’s easier to value hard work and authenticity if you’re confident your life will be pretty pleasurable. For those living in constant fear, pain, or misery, perhaps the authenticity of their experience matters less than some simple moments of bliss.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing

Democracy is hidden in the data

Explainer

Health + Wellbeing, Society + Culture

Ethics Explainer: Logical Fallacies

Opinion + Analysis

Science + Technology, Health + Wellbeing

Does your therapy bot really care about you? The risks of offloading emotional work to machines

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing

HSC exams matter – but not for the reasons you think

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

The road back to the rust belt

The road back to the rust belt

Opinion + AnalysisHealth + Wellbeing

BY Dennis Glover The Ethics Centre 24 NOV 2016

In The Road to Wigan Pier, George Orwell observed that it was far easier for a Bishop to relate to a tramp than to a solid member of the working class.

The poverty of the former was wholly obvious, and one could easily enter into his world by tramping with him and offering him a bowl of soup, but entering into the homes and culture of the latter was almost impossible.

In Australia today we might put it differently: it’s often easier for an educated ‘progressive’ to relate to a refugee or an Indigenous person or an LGBTI person than to someone in a Housing Commission suburb.

This is understandable and even laudable. After all, it’s the mark of a civilised community to treat others – even those least like us – with respect and to prioritise those whose needs are the most obvious and urgent. This way of thinking has become increasingly central to our liberal culture.

For example, I have before me a scholarship guide (really an advertising supplement) for some of the nation’s wealthiest private schools. In it you will find scholarships specifically targeted at diverse categories of people whose moral call on us is obvious, but none targeted at children from the old factory suburbs with high unemployment. The closest we get are vague references to help for ‘the children of families who require financial assistance’, which could mean just about anything.

Without noticing it, and often with the very best of intentions, we have stopped thinking and talking about the working class. When I recently wrote a book about one of our most neglected former Housing Commission suburbs, I was surprised at the consternation – even offense – it generated, particularly on the Left. Has it become so unusual to discuss such things? The shock of recent overseas events for such discussion has made this blindspot obvious and acceptable.

Without noticing it, and often with the very best of intentions, we have stopped thinking and talking about the working class.

This seems to me somewhat extraordinary given there are now numerous suburbs in Australia where the unemployment rate has been at 20, 21, 22 and even 33.6 percent for a decade or more. That we have been able to almost completely ignore this level of economic injustice for so long tells us something about how much our way of thinking has changed, amounting almost to a moral blindness. The coming closure of car factories and coal fired power plants across Victoria and South Australia will only make this worse, creating our own versions of America’s rust belt.

These days, it seems, one can be a self-identifying ‘progressive’ without giving much thought at all to what’s happening to the workers and the unemployed. The implication is they represent our economic past, and are therefore not wholly worthy of serious thought. Scratch a socially-progressive economist and you may well find someone who thinks saving manufacturing jobs to be a doubtful investment – perhaps it’s better for the general good such people and places be allowed to quietly disappear. The problem, as Britain and America shows, is they don’t disappear. They collapse in on themselves and get angry.

The way the culture wars have poisoned our political debates means this sort of thing isn’t easy to say without opening oneself up to some charge of illiberalism, so let me be clear: we should treat refugees more humanely, keep aggressively closing the gap between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians, and keep expanding the circle of rights to include new categories of difference, but we must also talk about what’s happening to the old working class. We can do all these things simultaneously but at the moment we are not.

Every day this ignoring of the old working class becomes a bigger problem for our democracy. As Brexit and Donald Trump’s victory demonstrate, in an economy that is restructuring, populists will eagerly pounce and turn the sense of neglect felt by ‘the forgotten’ into envy and resentment. The resuscitation of Pauline Hanson’s One Nation Party shows it may be happening here too. We need to advance on a broader front.

If you want to know why Australia is currently having a debate about Section 18C of the Race Discrimination Act, it’s partly because those who seek to exploit this envy and resentment need to remove laws which restrain the full expression of these negative emotions. The attacks on 18C and the fate of the old working class are ultimately connected.

Some argue the Left’s response must be to abandon what is commonly dismissed as ‘the rights agenda’ and take a more populist stand. This is wrong. The Left, which has traditionally been both liberal and social-democratic, shouldn’t downplay its liberalism but, rather, give new life to the social-democratic half of its equation, which it has been neglecting for too long. This doesn’t mean looking backwards. It means thinking through how our older industrial communities can be revived to take advantage of economic restructuring – instead of treating their interests as an irritating afterthought.

What form this modernised social-democracy will take is as yet to be determined but one thing is clear: it has to start with a moral effort to know what’s going on in the lives of people in the places where we stopped looking a generation ago, and it needs to be followed by a public policy effort that matches the scale of the problem.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

To live well, make peace with death

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships, Science + Technology

When do we dumb down smart tech?

Explainer

Health + Wellbeing

Ethics Explainer: Hedonism

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships, Science + Technology

Periods and vaccines: Teaching women to listen to their bodies

BY Dennis Glover

Dennis Glover is a fellow of the Per Capita think tank and the author of An Economy is Not a Society: Winners and Losers in the New Australia

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Melbourne Cup: The Ethical Form Guide

Melbourne Cup: The Ethical Form Guide

Opinion + AnalysisClimate + EnvironmentHealth + WellbeingSociety + Culture

BY The Ethics Centre 1 NOV 2016

The nation stops – and turns a blind eye.

The Melbourne Cup is the race that ‘convenes’ rather than ‘stops’ the nation. It’s a classic example of a moment when the abstraction that is the nation – large, sprawling, messy and diverse – is made temporarily and symbolically concrete. This is an illusion. But perhaps a necessary one.

The mega media sport spectacle is highly serviceable to the fantasy of the united nation because it is popular culture played out in real time. Sport is implicated in the idea of a singular Australian identity because it is apparently open and meritocratic, and also has operated historically as a vehicle for the projection of ‘Australianness’.

The Melbourne Cup represents the pros and cons of contemporary sport and society. It is devoted to pleasure as an interruption of the daily work routine that consumes more and more of our time. It is carnivalesque – fleetingly turning the world upside down.

But it is characterised by the range of excess demanded by consumer capitalism – risky financial expenditure, alcohol consumption and repressive co-optation. All of this activity is conducted using the body of the horse that is celebrated one minute and whipped the next, highly prized for sporting and breeding performance in some cases and turned into abattoir fodder in others.

National sporting spectacles are here to stay. The ‘people’, the state and the commercial complex demand them, but they should not be excuses for rampant collective self-delusion.

– David Rowe, Professor of Cultural Research at Western Sydney University.

If you loved horses, you wouldn’t treat them as commodities

We’re often told those involved in the horse racing industry truly love horses and treat them with the utmost respect. I have no doubt they believe that to be true, but their actions don’t support these claims.

If those working with horses truly loved them, they would spend time and money re-homing and appropriately retiring racehorses at the end of their careers. Instead, the evidence suggests racehorses are only loved when they have the potential to make money. When they’re injured or no longer able to race, they’re often sent off to the knackery without a second’s thought.

The racing industry pushes horses beyond their natural limits. This results in short careers and extensive injuries, such as those suffered by Admiral Rakti last year. Since Admiral Rakti’s death, 127 horses have died on Australian race tracks.

The ultimate image for this exploitative approach to racing is the whip, which desperately needs to be banned. In doing so, we would see horses performing at the peak of their natural ability rather than desperately running due to fear and pain.

– Elio Celotto, Campaign Director at the Coalition for the Protection of Racehorses.

The risks of horse racing are imposed on unwilling participants

Horse racing differs ethically from other sports. In other sports, it is the participant who freely decides to accept the risks. In horse racing, the risks are relatively low for the riders and extremely high for the animals.

It is not unethical to accept the risks of a given sport. Nor, in my view, is it always unethical to take the life of animals. The question is whether the costs of horse racing are reasonable, or whether they are unacceptably high.

Most Australians today would have ethical objections to entertainments such as bullfighting or dog fighting, or the use of non-domestic animals in circus acts. The number of horses slaughtered annually as a result of the racing industry far exceeds the number of animal deaths from most of these other entertainments.

The costs of the racing industry are unacceptably high. The situation is unlikely to improve as long as horse racing in Australia remains so closely tied to the enormous economic interests of the gambling industry.

– Ben Myers, Lecturer in Systematic Theology at United Theological College.

The Melbourne Cup sweep is harmless fun, but not in the classroom

The effects of gambling are an oft-discussed topic among my colleagues, but in the past week the discussion has been triggered by an all-staff email about the office’s annual Melbourne Cup Sweep. One staff member felt it was totally inappropriate for an organisation operating in mental health and wellbeing to be promoting in any way a day of socially acceptable statewide gambling.

I actually disagree, although not strongly. A sweep is a one-off, fixed price competition, not much different from a raffle. It’s in no way addictive in the way that poker machines and online betting can be.

The normalisation of gambling is certainly insidious. There is some evidence that the younger a person is when they have their first betting win, the more likely they are to develop problems down the track. So a sweep in a primary school does sound icky to me.

– Heather Grindley, Public Interest Manager at the Australian Psychological Society.

The spectacle is lost in a “feeding frenzy” of gambling

The Melbourne Cup is a genuine Australian icon. However, it’s now also a commodified hub for a gambling feeding frenzy. This is a tough time of year for people who are trying to restrain their gambling.

Effective regulation can undoubtedly reduce the harms associated with gambling. Cup Day should be a reminder that commercialised gambling corrupts sport and induces misery for many, including those who never gamble. Decent regulation might reduce super-profits but it would certainly help make Australia’s unique sporting and social environment safer, more fun and lot more enjoyable.

– Charles Livingstone, Senior Lecturer in Public Health and Preventive Medicine at Monash University.

The Melbourne Cup pits debauchery against dignity

As I write, many will be gathered in offices, pubs and racecourses around the country dressed to the nines. Fascinators, frocks, loud ties and sharp suits are the order of the day for the “world’s richest race”.

And yet by the end of it all, many punters will be staggeringly drunk – their state highlighted by its juxtaposition to their glamorous attire. Every year, tabloids gleefully post pictures of women in various stages of undress – simultaneously glorifying and shaming the debauchery that accompanies a race some revellers will likely miss, having already passed out.

Ultimately the Melbourne Cup is full of ethical polarities. It follows the highs and lows of the race itself. Fine champagne is popped in celebration as punters pass out from one too many drinks, horses are glorified as they are exploited, and once-off punters dress up and participate in the same gambling industry that destroys so many lives.

Racing Victoria were unavailable for comment but directed readers to their position on equine welfare.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships, Society + Culture

The ethics of tearing down monuments

READ

Society + Culture

6 dangerous ideas from FODI 2024

Opinion + Analysis

Climate + Environment, Health + Wellbeing

How can we travel more ethically?

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing