Ethical by Design: Evaluating Outcomes

Ethical by Design Evaluating Outcomes: Principles for Data and Development

Ethical by Design Evaluating Outcomes: Principles for Data & Development

Understand the ethical considerations in using big data across aid and development projects, and get a practical framework for decision making.

The increasing focus on impact, and its measurement is not solely about accountability. Instead, in this paper Dr Simon Longstaff presents why it’s driven by the desire to do as much good as possible in resource-constained conditions.

Traditionally the evaluation and monitoring of development based projects has been undertaken on the ground. However new technologies, big data, and AI have given rise to a host of possibilities, and with them, new ethical considerations.

The paper draws on insights generated by a project by Australia’s Department for Foreign Affairs, of which The Ethics Centre has been in consultation.

It offers an example Ethical Framework for decision making in new technology innovation for womens’ empowerment in Afghanistan, and a host of core tenants or considerations specific to the measurement and evaluation of development projects across areas of organisation, projects and data.

The report also provides a practical understanding of the components of an Ethical Framework, the virtue of ethical restraint, and the role of value driven decision making to benefit vulnerable groups in aid development work. Plus access a decision making model to slow down thinking and consider new perspectives.

It’s a great resource for anyone working with or associated with aid work domestically or internationally, particularly those involved in evaluation, measurement and data collection.

"The ethical impulse that drives innovation in development is to be admired. It is the same impulse that has led a range of actors to explore the possibilities of new technologies – not least in the field of data science – to improve the quality of monitoring and evaluation"

DR SIMON LONGSTAFF

WHAT'S INSIDE?

Ethical restraint

Empowering the vulnerable

Ethical Framework

Ethical decision making model

AUTHORS

Authors

Dr Simon Longstaff

Dr Simon Longstaff has been Executive Director of The Ethics Centre for 30 years, working across business, government and society. He has a PhD in philosophy from Cambridge University, is a Fellow of CPA Australia and of the Royal Society of NSW, and an Honorary Professor at ANU National Centre for Indigenous Studies. Simon was made an Officer of the Order of Australia (AO) in 2013.

DOWNLOAD THE REPORT

You may also be interested in...

Nothing found.

Big Thinker: Peter Singer

Peter Singer (1946—present), one of world’s most influential living philosophers, is best known for applying rigorous logic to a range of practical issues from animal rights, giving to charity to the ethics of abortion and infanticide.

Singer was born in Melbourne in 1946 to Austrian Jewish Holocaust survivors. As a teen he declared his atheism and refused to celebrate his Bar Mitzvah. After studying law, history and philosophy at Melbourne University, he won a scholarship to Oxford University, writing his thesis on civil disobedience. In 1996 he ran unsuccessfully for the Greens in the Victorian State Parliament, and he has held posts at Melbourne, Monash, New York, London and Princeton Universities. His impact on public debate and academic philosophy cannot be overstated.

A key aspect of Singer’s contributions is the idea of ‘equal consideration of interests’. This informs both his views towards animals and charity. It means that we should consider the interests of any sentient beings who have the capacity to suffer and feel pleasure and pain.

Singer is a consequentialist, which means he defines ethical actions as ones that maximise overall pleasure and reduce overall pain. Part of what makes him such a challenging and influential thinker is his application of utilitarianism to real-world problems to offer counter-intuitive yet compelling solutions.’

Are you speciesist?

While at Oxford, Singer recalls a conversation with a friend over lunch that was the “most formative experience of [his] life”. Singer had the meat spaghetti, whereas his friend opted for the salad. His friend was the “first ethical vegetarian” he’d met. Two weeks later, Singer became a vegetarian and several years later published his seminal work Animal Liberation (1975).

Singer’s argument for not eating meat is more-or-less the same as another utilitarian philosopher, Jeremy Bentham. Bentham wrote that “the question is not can they reason or can they talk, but can they suffer?” Similarly, Singer argues that animals have the capacity to suffer. Just as we rightly condemn torture, we should also condemn practices like factory farming that inflict unjustifiable pain on non-human animals. He coined the term ‘speciesism’ to describe the privileging of humans over other animals.

Giving to charity

In Singer’s essay “Famine, Affluence and Morality” (1972), he argues that people in rich countries have a moral obligation to give to charities that help people in poverty overseas. He uses an analogy of a drowning child: if we were walking past a shallow pond and saw a child drowning, we would wade in and save the child, even if this meant wrecking our favourite and most expensive pair of shoes. Likewise, because we know there are children dying overseas from preventable poverty-related diseases, we should be giving at least some of our income to charities that fight this.

Opponents to Singer argue that his view about giving to charity is psychologically untenable, and that there are differences between giving to charity and saving a drowning child. For example, the physical act of pulling a child out from water is more morally compelling than sending a cheque overseas. Other arguments include: we don’t know the child will definitely be saved when we send the cheque, fighting poverty requires a collective global effort not just an individual donation, and charities are ineffective and have high overhead costs.

Singer concedes that there may be psychological reasons why people would save the drowning child yet don’t give much to charity, but he says even if it seems strange, rationally there are no relevant moral differences between the cases.

Responding to the criticism that charities may not be effective has led Singer to be a proponent of ‘effective altruism’. In his book The Most Good You Can Do (2015) he describes how a number of charity evaluators can recommend the most cost-effective way to do good. Singer recommends giving on a progressive scale, depending on one’s income.

Instead of pursuing careers in academia, some of Singer’s brightest past students have decided to work for Wall Street to make as much money as possible to then give this away to effective charities.

Controversy around infanticide

Singer has faced sustained criticism and protest throughout his career for his views on the sanctity of life and disability – especially in Germany, where in the 90’s, his views were compared to Nazism and university courses that set his books were boycotted. While he has always been a staunch supporter of abortion on the grounds that a foetus lacks self-consciousness and the criteria of personhood, he argues there is no moral difference between abortion in the womb and killing a newborn. Furthermore, because a newborn cannot yet be classified as a person, if its parents do not want it to survive, or if it has an extreme disability meaning that keeping it alive would be very costly, there is potential justification in killing it.

Religious sanctity-of-life critics argue that Singer’s ethics ignore the fundamental sanctity of human life. Disability rights advocates argue that Singer’s views are ableist, explaining that the quality of life of a disabled person is less than that of a non-disabled person ignores the socially-constructed nature of disability – its harms and inconveniences are largely because the built environment is made for able-bodied people.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

COP26: The choice of our lives

Explainer

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Critical Race Theory

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships, Society + Culture

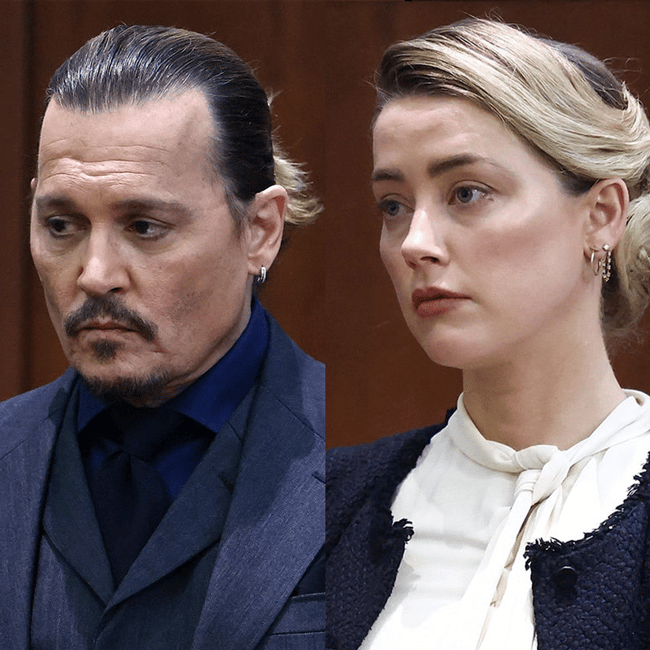

You won’t be able to tell whether Depp or Heard are lying by watching their faces

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture, Politics + Human Rights

What happens when the progressive idea of cultural ‘safety’ turns on itself?

Join our newsletter

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Time for Morrison’s ‘quiet Australians’ to roar

Time for Morrison’s ‘quiet Australians’ to roar

Opinion + AnalysisPolitics + Human Rights

BY Simon Longstaff 21 AUG 2019

The Prime Minister, Scott Morrison, has attributed his electoral success to the influence of ‘Quiet Australians’.

It is an evocative term that pitches somewhere between that of the ‘silent majority’ and Sir Robert Menzies’ concept of the ‘Forgotten People’. Unfortunately, I think that the phrase will have a limited shelf-life because increasing numbers of Australians are sick of being quiet and unobserved.

In the course of the last federal election, I listened to three mayors being interviewed about the political mood of their rural and regional electorates. They said people would vote to ensure that their electorates became ‘marginal’. Despite their political differences, they were unanimous in their belief that this was the only way to be noticed. They are the cool tip of a volcano of discontent.

Quiet or invisible?

Put simply, I think that most Australians are not so much ‘quiet’, as ‘invisible’ – unseen by a political class that only notices those who confer electoral advantage. Thus, the attention given to the marginal seat or the big donor or the person who can guarantee a favourable headline and so on…

The ‘invisible people’ are fearful and angry.

They fear that their jobs will be lost to expert systems and robots. They fear that, without a job, they will be unable to look after their families. They fear that the country is unprepared to meet and manage the profound challenges that they know to be coming – and that few in government are willing to name.

They are angry that they are held accountable to a higher standard than government ministers or those running large corporations. They are angry that they will be discarded as the ‘collateral damage’ of progress.

And in many ways, they are right.

Is democracy failing us?

After all, where is the evidence to show that our democracy is consciously crafting a just and orderly transition to a world in which climate change, technological innovation and new geopolitical realities are reshaping our society? Will democracy hold in such a world?

By definition, democracy accords a dignity to every citizen – not because they are a ‘customer’ of government, but – because citizens are the ultimate source of authority. The citizen is supposed to be at the centre of the democratic state. Their interests should be paramount.

Yet this fundamental ‘promise’ seems to have been broken. The tragedy in all of this is that most politicians are well-intentioned. They really do want to make a positive contribution to their society. Yet, somehow the democratic project is at risk of losing its legitimacy – after which it will almost certainly fail.

In the end, while it’s comforting to whinge about politicians, the media, and so on, the quality of democracy lies in the hands of the people. We cannot escape our responsibility. Nor can we afford to remain ‘quiet’. Instead, wherever and whoever we may be, let’s roar: We are citizens. We demand to be seen. We will be heard.

The Ethics Centre’s next IQ2 debate – Democracy is Failing the People – is on Tuesday 27 August at Sydney Town Hall. Presenter and comedian Craig Reucassel will join political veteran Amanda Vanstone to go up against youth activist Daisy Jeffrey and economist Dr Andrew Charlton to answer if democracy is serving us, or failing us.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Big thinker

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Big Thinker: Adam Smith

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

You’re the Voice: It’s our responsibility to vote wisely

Explainer

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Ethics Explainer: The Harm Principle

Big thinker

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Big Thinker: Eleanor Roosevelt

Join our newsletter

BY Simon Longstaff

Simon Longstaff began his working life on Groote Eylandt in the Northern Territory of Australia. He is proud of his kinship ties to the Anindilyakwa people. After a period studying law in Sydney and teaching in Tasmania, he pursued postgraduate studies as a Member of Magdalene College, Cambridge. In 1991, Simon commenced his work as the first Executive Director of The Ethics Centre. In 2013, he was made an officer of the Order of Australia (AO) for “distinguished service to the community through the promotion of ethical standards in governance and business, to improving corporate responsibility, and to philosophy.” Simon is an Adjunct Professor of the Australian Graduate School of Management at UNSW, a Fellow of CPA Australia, the Royal Society of NSW and the Australian Risk Policy Institute.

Big Thinker: John Locke

English Philosopher John Locke (1632—1704) is behind many of the ideas we now take for granted in a liberal democracy. Amongst them, his defence of life and liberty as natural and fundamental human rights.

He was especially known for his liberal, anti-authoritarian theory of the state, his empirical theory of knowledge and his advocacy of religious toleration. Much of Locke’s work is characterised by an opposition to authoritarianism, both at the level of the individual and within institutions such as the government and church.

Born in 1632, in his time he gained fame arguing that the divine right of kings is not supported by scripture. Instead, he defended a limited government whose duty is to protect the rights and liberty of its citizens. This idea is familiar to us now, yet at the time it was revolutionary, arguing against the monarchy as the source of society’s governance. A familiar idea in modern day, at the time it was revolutionary – an argument to depart from the monarchy as the source of society’s governance.

In defending his stance, Locke appealed to the notion of natural rights. He invited us to imagine an initial ‘state of nature’ with no government, police or private property. Locke argued that humans could discover, through careful reasoning, that there are natural laws which suggest that we have natural rights to our own persons and to our own labour.

Eventually we could reason that we should create a social contract with others. Out of this contract would emerge our political obligations and the institution of private property. In Locke’s version of the social contract, a human “divests himself of his natural liberty, and puts on the bonds of civil society…agreeing with other men to join and unite into a community” and by submitting to majority rule form a government designed to protect their rights.

The limits of power

Locke’s argument also places limits on the proper use of power by government authorities. While civil society, as viewed through Locke’s liberalism, sees that the individual must sacrifice – or at least compromise – his/her freedom in the name of the public good, the public good ought not to interfere with the individual’s freedom.

Due to this emphasis on liberty, Locke defended a distinction between a public and a private realm. The public realm is that of politics and the individual’s role in the community as a part of the state, which may include, for example, voting or fighting for one’s country. The private realm is that of domesticity where power is parental (traditionally, ‘paternal’).

For Locke, government should not interfere in the private realm. He held the argument that citizens were entitled to protest or revolt or disband a government when it failed to protect their collective interests. On this view it is crucial we distinguish the legitimate from the illegitimate functions of institutions.

Locke asked us to use reason in order to seek the truth, rather than simply accept the opinion of those in positions of power or be swayed by superstition. In this way, we see Locke as an Enlightenment thinker –our natural reason a light that shines, guiding our understanding in order to reveal knowledge.

Knowledge and personal identity

As an empiricist, Locke believed we gain our knowledge through experiences in the world. In contrast to the views of his rationalist predecessor Descartes, Locke argued that we are born as a blank slate or a tabula rasa. This means that at birth our mind has no innate ideas – it is blank. As our mind develops, sensations give rise to simple ideas, from which we form those more complex.

This theory of learning gives rise to another radical idea for his time. Locke asserted that in order to help children avoid developing bad thinking habits, they should be trained to base their beliefs on sound evidence. The strength of our belief should correlate to how strong or weak the evidence for it happens to be.

Furthermore, for Locke, our consciousness is what makes us ‘us’, constituting our personal identity.

Locke’s legacy

We see Locke’s legacy in the 1776 US Declaration of Independence, which was founded on his natural rights theory of government and proclaimed ‘we hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness’.

Following on from his theory of human rights, we also see Locke’s legacy in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, which was adopted by the United Nations General Assembly on 10 December 1948. Philosophers debate as to whether such rights are indeed ‘natural’, or whether they have been ‘constructed’ and agreed upon by society as useful rules to adopt and enforce.

Locke’s lasting legacy is the argument that society ought to be ruled democratically in such a way as to protect the liberty and rights of its citizens. And that the government should never over-step its boundaries and must always remember it is a glorified secretary of the people.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

Farhad Jabar was a child – his death was an awful necessity

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Science + Technology

Is it right to edit the genes of an unborn child?

Opinion + Analysis

Climate + Environment, Politics + Human Rights

Limiting immigration into Australia is doomed to fail

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights, Science + Technology

Not too late: regaining control of your data

Join our newsletter

BY Dr Laura D’Olimpio

Dr Laura D’Olimpio is senior lecturer in philosophy of education at the University of Birmingham, UK, and co-edits the Journal of Philosophy in Schools.

Drawing a line on corruption: Operation eclipse submission

Drawing a line on corruption: Operation eclipse submission

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + LeadershipPolitics + Human RightsSociety + Culture

BY The Ethics Centre 6 AUG 2019

The Ethics Centre (TEC) has made a submission to the NSW Independent Commission Against Corruption (ICAC) regarding its discussion paper, The Regulation of Lobbying, Access and Influence in NSW: A Chance To Have Your Say.

Released in April 2019 as part of Operation Eclipse, it’s public review into how lobbying activities in NSW should be regulated.

As a result of the submission TEC Executive Director, Dr Simon Longstaff has been invited to bear witness at the inquiry, which will also consider the need to rebuild public trust in government institutions and parliamentarians.

Our submission acknowledged the decline in trust in government as part of a broader crisis experienced across our institutional landscape – including the private sector, the media and the NGO sector. It is TEC’s view that the time has come to take deliberate and comprehensive action to restore the ethical infrastructure of society.

We support the principles being applied to the regulation of lobbying: transparency, integrity, fairness and freedom.

Key points within The Ethics Centres submission include:

-

- There is a difference between making representations to government on one’s own behalf and the practice of paying another person or party with informal government connections to advocate to government. TEC views the latter to be ‘lobbying’

-

- Lobbying has the potential to allow the government to be influenced more by wealthier parties, and interfere with the duty of officials and parliamentarians to act in the public interest

-

- No amount of compliance requirements can compensate for a poor decision making culture or an inability of officials, at any level, to make ethical decisions. While an awareness and understanding of an official’s obligations is necessary, it is not sufficient. There is a need to build their capacity to make ethical decisions and support an ethical decision making culture.

You can read the full submission here.

Update

Dr Simon Longstaff, Executive Director at The Ethics Centre, presented as a witness to the Commission on Monday 5 August. You can read the public transcript on the ICAC website here.

MOST POPULAR

ArticleHEALTH + WELLBEING

Maggie Beer: Good food can drive better aged care

ArticleHEALTH + WELLBEING

Parent planning – we should be allowed to choose our children’s sex

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Are we idolising youth? Recommended reads

Are we idolising youth? Recommended reads

Opinion + AnalysisClimate + EnvironmentPolitics + Human Rights

BY Kym Middleton 6 JUN 2019

IQ2 Australia debates whether we need to ‘Stop Idolising Youth’ on 12 June.

Advertisers market to youth despite boomers having the strongest buying power. Unlike professions such as law and medicine, the creative industries prefer ‘digital natives’ over experience.

Young actors play mature aged characters. Yet openly teasing the young for being entitled and lazy is a popular social sport. Are the ageism insults flung both ways?

1. Why do marketers hate old people?

Ad Contrarian, Bob Hoffman / 2 December 2013

An oldie but a goodie. Bob Hoffman is the entertainingly acerbic critic of marketing and author of books like Laughing@Advertising. In this blog post he aims a crossbow at the seemingly senseless predilection of advertisers for using youth to market their products when older generations have more money and buy more stuff.

“Almost everyone you see in a car commercial is between the ages of 18 and 24,” he says. “And yet, people 75 to dead buy five times as many new cars as people 18 to 24.” He makes a solid argument.

2. It’s time to stop kvetching about ‘disengaged’ millennials

Ben Law, The Sydney Morning Herald / 27 October 2017

Ben Law asks, “Aren’t adults the ones who deserve the contempt of young people?” He argues it is older generations with influence and power who are not addressing things as big as the non-age-discriminatory climate crisis. He also shares some anecdotes about politically engaged and polite public transport riding kids.

You might regard a couple of the jokes in this piece leaning toward ageist quips but Law is also making them at his own expense. He points out millennials – the generation to which he belongs and the usual target for jokes about entitled youth – are nearing middle age.

3. Let’s end ageism

Ashton Applewhite, TED Talk / April 2017

There’s something very likeable about Ashton Applewhite – beyond her endearing name. This is even though she opens her TEDTalk with the confronting fact the one thing we all have in common is we’re always getting older. Sure, we’re not all lucky enough to get old, but we constantly age.

In pointing to this shared aspect of humanity, Applewhite makes the case against ageism. This typically TED nugget of feel good inspiration is great for every age. And if you’re anywhere between late 20s and early 70s, you’ll love the happiness bell curve. In a nutshell: it gets better!

4. Instagram’s most popular nan

Baddiewinkle, Instagram/ Helen Van Winkle

Her tagline is “stealing ur man since 1928”. Get lost in a delightful scroll through fun, colourful images from a social media personality who does not give a flying fajita for “age appropriate” dressing or demeanours. Baddie Winkle was born Helen Ruth Elam Van Winkle in Kentucky over 90 years ago.

Her internet stardom began age 85 when her great granddaughter Kennedy Lewis posted a photo of her in cut-off jeans and a tie-dye tee. Now Winkle’s granddaughter Dawn Lewis manages her profile and bookings. Her 3.8 million followers show us audiences aren’t only interested young social media influencers. “They want to be me when they get older,” Winkle says. Damn right we do.

Event info

IQ2 Australia makes public debate smart, civil and fun. On 12 June two teams will argue for and against the statement, ‘Stop Idolising Youth’. Ad writer Jane Caro and mature aged model Fred Douglas take on TV writer Ben Jenkins and author Nayuka Gorrie. Tickets here.

MOST POPULAR

ArticleHEALTH + WELLBEING

Maggie Beer: Good food can drive better aged care

ArticleHEALTH + WELLBEING

Parent planning – we should be allowed to choose our children’s sex

BY Kym Middleton

Former Head of Editorial & Events at TEC, Kym Middleton is a freelance writer, artistic producer, and multi award winning journalist with a background in long form TV, breaking news and digital documentary. Twitter @kymmidd

Are we prepared for climate change and the next migrant crisis?

Are we prepared for climate change and the next migrant crisis?

Opinion + AnalysisClimate + EnvironmentPolitics + Human Rights

BY Kate Prendergast 7 MAY 2019

A powerful infographic published in 2014, predicted how many years it would take for a world city to drown.

It used data from NASA, Sea Level Explorer, and the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Venice will be the first to go under apparently, its canals rising to wetly throttle the city of love. Amsterdam is set to follow, Hamburg next.

Other tools play out the encroachment of rising tides on our coasts. This one developed by EarthTime shows Sydney airport as a large puddle if temperatures increase by four degrees. There’s also research suggesting our ancestors may one day look down to see fish nibbling on the Opera House sails.

Climate change refugees will become reality

Sea level rise is just one effect of anthropogenic climate change that would make a place uninhabitable or inhospitable to humankind. It’s also relatively slow. Populations in climate vulnerable hotspots face a slew of other shove factors, too.

Already, we are seeing a rising frequency of extreme weather events. Climate change was linked to increasingly destructive tropical cyclones in a report published in Nature last year, and Australia’s Climate Council attributed the same to earlier and more dangerous fire seasons. Rapidly changing ecosystems will impact water resources, crop productivity, and patterns of familiar and unfamiliar disease. Famine, drought, poverty and illness are the horsemen saddling up.

Some will die as a result of these events. Others, if they are able, will choose to stay. The far sighted and privileged may pre-empt them, relocating in advance of crisis or discomfort.

These migrants can be expected to move through the ‘correct’ channels, under the radar of nativist suspicion. (‘When is an immigrant not an immigrant?’ asks Afua Hirsch. ‘When they’re rich’.)

But many more will become displaced peoples, forcibly de-homed. Research estimates this number could be anywhere between 50 million and 1 billion in the 21st century. This will prompt new waves of interstate and international flows, and a resultant redistribution and intensification of pressures and tensions on the global map.

How will the world respond?

Where will they go? What is the ethical obligation of states to welcome and provide for them? With gross denialism characterising global policies towards climate change, and intensifying hostility locking down national borders, how prepared are we to contend with this challenge to come?

“You can’t wall them out,” Obama recently told the BBC. “Not for long.”

While interstate climate migration (which may already be occurring in Tasmania) will incur infrastructural and cultural problems, international migration is a whole and humongous other ethical conundrum. Not least because currently, climate change migrants have almost no legal protections.

Is a person who moves because of a sudden, town levelling cyclone more entitled to the status of climate migrant or refugee (and the protection it affords) than someone who migrates as a result of the slow onset attrition of their livelihood due to climate change?

Who makes the rules?

Does sudden, violent circumstance carry a greater ethical demand for hospitality than if, after many years of struggle, a Mexican farmer can no longer put food on the table because his land has turned to dust? Does the latter qualify as a climate or economic migrant, or both?

Somewhat ironically (and certainly depressingly), the movement of people to climate ‘havens’ will place stress on those environmental sanctuaries themselves, potentially leading to concentrated degradation, pollution and threat to non-human nature. (On the other hand, climate migration could allow for nature to reclaim the places these migrants have left.)

There is also the argument that, once migrants from developing countries have been integrated into a host country, their carbon footprint will increase to resemble that of their new fellow citizenry – resulting in larger CO2 emissions. From this perspective, put forward by Philip Cafaro and Winthrop Staples, it is in the interests of the planet for prosperous countries to limit their welcome.

Not that privileged populations need much convincing. Jealous fear of future scarcity, a globalisation inflamed resentment towards the Other, a sense that modernity has failed to deliver on its promise of wholesale bounty: all these are conspiring to create increasingly tribalised societies that enable the xenophobic agendas of their governments. A recent poll showed that 46 percent of Australians believe immigration should be reduced, a percentage consistent with attitudes worldwide.

A divided world

In the US, there’s Trump’s grand ‘us vs them’ symbol of a wall. As reported in the Times, German lawmakers are comparing refugees to wolves. In Italy, tilting towards populism and the right, a mayor was arrested after transforming his small town into a migrant sanctuary.

Closer to home, in a country where the 27 years without recession could be linked to immigration, there’s Scott Morrison’s newly proposed immigration cuts. There’s Senator Anning blaming the Christchurch massacre on Muslim immigration. There’s the bipartisan support for the prospects, wellbeing and mental health of asylum seekers to deteriorate to such an extent, the UN human rights council described it as ‘massive abuse’.

Yet the local effects of climate change don’t have a local origin. Causality extends beyond borders, piling miles high at the feet of industrialised countries. Nations like the US and Australia enjoy high standards of living largely because we have been pillaging and burning fossil fuels for more than a century. Yet those least culpable will bear the heaviest cost.

This, argues the author of a paper published in Ethics, Policy and Environment, warrants a different ethical framework than that which applies to other kinds of migration. He concludes that industrialised nations “have a moral responsibility … to compensate for harms that their actions have caused”.

This responsibility may include investing in less developed countries to mitigate climate change effects, writes the author. But it also morally obliges giving access, security and residence to those with nowhere else to go.

MOST POPULAR

ArticleHEALTH + WELLBEING

Maggie Beer: Good food can drive better aged care

ArticleHEALTH + WELLBEING

Parent planning – we should be allowed to choose our children’s sex

BY Kate Prendergast

Kate Prendergast is a writer, reviewer and artist based in Sydney. She's worked at the Festival of Dangerous Ideas, Broad Encounters and Giramondo Publishing. She's not terrible at marketing, but it makes her think of a famous bit by standup legend Bill Hicks.

Corruption, decency and probity advice

Corruption, decency and probity advice

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + LeadershipPolitics + Human RightsSociety + Culture

BY David Burfoot 6 MAY 2019

Corruption and probity are hot topics in Australia’s public sector. Even a cursory glance at recent cases brought before corruption watchdogs shows this.

The long running stories and court cases that follow have become a staple of national news bulletins. Any time a state asset is built, sold or disposed of, there are serious questions to be asked.

Probity – which is a corporate noun for ethics or honesty and decency – has established its place in the architecture of technical services that assess, assure and measure high-risk public sector projects. Probity advising and auditing is crucial when how a project is executed is just as important as any intended outcome.

As the line separating public and private sector accountabilities becomes less clear, non-government actors are increasingly looking to probity professionals to help ensure – and show – integrity in their dealings. However, before doing so it is important the probity professionals themselves improve the integrity of their process and gain a more sophisticated understanding of ethical frameworks.

Probity services are provided both by large accounting firms and a growing band of smaller boutique operators. Probity plans (documents that set out how the project will be run to ensure the integrity of the process) are now a mandatory requirement for many public projects.

Probity professionals use a number of lenses to monitor and promote ethical decision making in execution, typically through the following fundamentals:

Value for money: Was the market tested adequately to ensure an organisation was achieving the most competitive result, which made the best use of resources?

Conflicts of interest and impartiality: Were processes in place to manage any actual, perceived or potential conflicts of interests?

Accountability and transparency: Was an auditable trail maintained to provide evidence of the integrity of the process? Was enough information made available to promote confidence – for example, were selection criteria and time lines for decision making adequately communicated?

Confidentiality: When sensitive information from stakeholders is received, such as private or business-in-confidence information, was there a process in place to identify and protect this information?

The growth of probity services over the last 30 years undoubtedly reflects their ability to add value to projects. However, over that same period there has been concern that practitioners have at times diminished, rather than promoted, probity fundamentals. Some of the critical factors include:

- Relying too heavily on compliance monitoring at the expense of ethical considerations

- Allowing their duties to be too narrowly defined by clients

- Lacking the confidence to challenge impropriety

- Allowing themselves to be “shopped” (much like “legal advice shopping,” clients can go from one probity advisor to another until they get the advice they want).

There is also concern that public sector agencies can overuse these services, having the effect of “contracting out” their probity obligations in their regular operations.

To some extent these are symptoms of the unregulated nature of probity services. There are no formal qualifications required for probity advisors and auditors and no professional standard governing them.

Their difference from traditional audits or investigations has led to some misunderstanding of their role and judgements which can lead to unfair criticism of probity professionals, but also to exploitation by both clients and probity practitioners.

To tackle these problems and prepare for a broader role in guiding business dealings, probity practitioners need to acknowledge their own industry’s need for an ethical framework and an increasingly robust standard for professional practice.

This framework would acknowledge their implied obligation to society to be more than a mere compliance check, and, on behalf of the average Joe on the street, to be the one in the room to ask a simple pub test question: after all the boxes have been ticked, does it look and sound like an ethical process?

To do this, the profession needs to imagine its duty in broader terms than self-interest or the interest of clients, but to society in general, in line with other professions tasked with acting in the public interest.

For some time, probity professionals have used policy documents such as the NSW Code of Practice for Procurement to gauge the ethical performance of government projects. However, as their duty and work expands to different sectors and in line with changing community expectations, they will need to be able to identify the ethical frameworks peculiar to those sectors and to the organisations they are commissioned by.

Used effectively, an ethical framework is the foundation of an organisation’s culture.

When requested to provide probity related advice, The Ethics Centre includes the ethical framework amongst its list of fundamentals. This allows our clients to do more than tick boxes. It allows them to assess whether they have lived up to their ethical obligations, the values they proport to uphold and their promise to the community.

In a world in which trust is in deficit, these are important skills to have.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Reports

Business + Leadership

Managing Culture: A Good Practice Guide

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

It’s time to consider who loses when money comes cheap

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Science + Technology

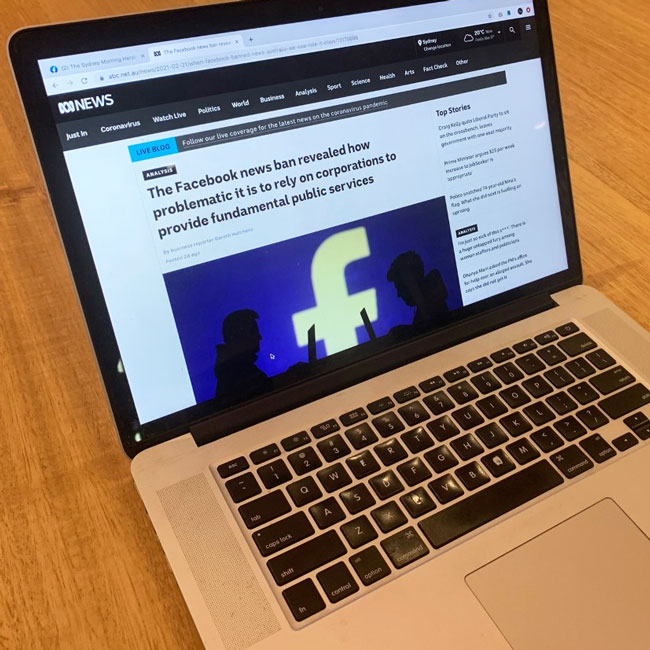

Who’s to blame for Facebook’s news ban?

LISTEN

Society + Culture

Festival of Dangerous Ideas (FODI)

BY David Burfoot

David has worked in the not-for-profit, public and private sectors domestically and internationally for organisations as diverse as the United Nations Development Program, Deloitte, the NSW Independent Commission Against Corruption and Sydney University. He has been an anti-corruption specialist with a number of government agencies and held senior positions responsible for corporate planning, change and internal communications.

Australia, it’s time to curb immigration

Australia, it’s time to curb immigration

Opinion + AnalysisClimate + EnvironmentPolitics + Human Rights

BY Satya Marar 3 MAY 2019

A majority of Australians welcome immigrants. So why then do opinion polls of young and old voters alike across the political divide, now find majority support for reducing our immigration intake?

Perhaps it could be for the same reason that faith in our political system is dwindling at a time of strong economic growth. Australia is the ‘lucky country’ that hasn’t had a recession in the last 28 years.

Yet we’ve actually had two recessions in this time if we consider GDP on a per-capita basis. This, combined with stagnant real wage growth and sharp increases in congestion and the price of housing and electricity in our major cities, could explain why the Australian success story is inconsistent with the lived experience of so many of us.

The decline of the Australian dream?

Our current intake means immigration now acts as a ponzi scheme.

The superficial figure of a growing headline GDP fuelled by an increasing population masks the reality of an Australian dream that is becoming increasingly out of reach for immigrants and native-born Australians alike.

We’ve been falsely told we’ve weathered economic calamities that have stunned the rest of the world. When taken on a per-capita basis, our economy has actually experienced negative growth periods that closely mirror patterns in the United States.

We’re rightly told we need hardworking immigrants to help foot the bill for our ageing population by raising productivity and tax revenue. Yet this cost is also offset when their ageing family members or other dependents are brought over. Since preventing them from doing so may be cruel, surely it’s fairer to lessen our dependence on their intake if we can?

A lack of infrastructure

Over 200,000 people settle in Australia every year, mostly in the major cities of Sydney and Melbourne. That’s the equivalent of one Canberra or greater Newcastle area a year.

Unlike the United States, most economic opportunities are concentrated in a few major cities dotting our shores. This combined with the failures of successive state and federal governments to build the infrastructure and invest in the services needed to cater for record population growth levels driven majorly by immigration.

A failure to rezone for an appropriate supply of land, mean our schools are becoming crowded, our real estate prohibitively expensive, our commutes are longer and more depressing, and our roads are badly congested.

Today, infrastructure is being built, land is finally being rezoned to accommodate higher population density and more housing stock in the outer suburbs, and the Prime Minister has made regional job growth one of his major priorities.

But these issues should have been fixed ten years ago and it’s increasingly unlikely that they will be executed efficiently and effectively enough to catch up to where they need to be should current immigration intake levels continue for the years to come.

Our governments have proven to be terrible central planners, often rejecting or watering down the advice of independent expert bodies like Infrastructure Australia and the Productivity Commission due to political factors.

Why would we trust them to not only get the answer right now, but to execute it correctly? Our newspapers are filled daily with stories about light rail and road link projects that are behind schedule.

All of it paid for by taxpayers like us.

Foreign workers or local graduates?

Consider also the perverse reality of foreign workers brought to our shores to fill supposed skill gaps who then struggle to find work in their field and end up in whatever job they can get.

Meanwhile, you’ll find two separate articles in the same week. One from industry groups cautioning against cutting skilled immigration due to shortages in the STEM fields. The other reporting that Australian STEM graduates are struggling to find work in their field.

Why would employers invest resources in training local graduates when there’s a ready supply of experienced foreign workers? What incentive do universities have to step in and fill this gap when their funding isn’t contingent on employability outcomes?

This isn’t about nativism. The immigrants coming here certainly have a stake in making sure their current or future children can find meaningful work and obtain education and training to make them job ready.

There’s only one way to hold our governments accountable so the correct and sometimes tough decisions needed to sustain our way of life and make the most of the boon that immigration has been for the country, are made. It’s to wean them off their addiction to record immigration levels.

Lest the ponzi scheme collapse.

And frank conversations about the quantity and quality of immigration that the sensible centre of politics once held, increasingly become the purview of populist minor parties who have experienced resurgence on the back of widespread, unanswered frustrations about unsustainable immigration that we are ill-prepared for.

This article was produced in association with IQ2: Should Australia curb immigration? With powerful arguments presented at both ends of the spectrum, it was a debate that raised issues from urban planning to government policy, environmental impacts to economic advantages and more.

MOST POPULAR

ArticleHEALTH + WELLBEING

Maggie Beer: Good food can drive better aged care

ArticleHEALTH + WELLBEING

Parent planning – we should be allowed to choose our children’s sex

BY Satya Marar

Satya Marar is an Indian-born, Sydney based writer, public commentator and Director of Policy at the Australian Taxpayers’ Alliance. He took part in the IQ2 debate, ‘Curb Immigration’

Where do ethics and politics meet?

Where do ethics and politics meet?

Opinion + AnalysisPolitics + Human Rights

BY The Ethics Centre 26 APR 2019

In the Western philosophical tradition, ethics and politics were frequently deemed to be two sides of a single coin.

Aristotle’s Ethics sought to answer the question of what is a good life for an individual person. His Politics considered what is a good life for a community (a polis). So, for the Ancient Greeks, at least, the good life existed on an unbroken continuum ranging from the personal through the familial to the social.

In some senses, this reflected an older belief that individuals exist as part of society. Indeed, in many cultures – in the Ancient world and today – the idea of an isolated individual makes little sense. Yet, there are a few key moments in Western philosophy when we see the individual emerging.

St Thomas Aquinas argued that no individual or institution has ‘sovereignty’ over the well-informed conscience of the individual.

René Descartes placed the self-certain subject at the centre of all knowledge and in doing so undermined the authority of institutions that based their claims to superiority on revelation, tradition or hierarchy. Reason was to take centre stage.

Aquinas and Descartes, along with many others, helped set the foundation for a modern form of politics in which the conscientious judgement of the individual takes precedence over that of the community.

Today, we observe a global political landscape in which ethics can be hard to detect. It’s easy to say that many politicians are ruled by naked greed, fear, opinion polls, blind ideology or a lust for power.

This probably isn’t fair to the many politicians who apply themselves to their responsibilities with care and diligence.

In the end, ethics is about living an examined life – something that should apply whether the choices to be made are those of an individual, a group or a whole society.

MOST POPULAR

ArticleHEALTH + WELLBEING

Maggie Beer: Good food can drive better aged care

ArticleHEALTH + WELLBEING