Do states have a right to pre-emptive self-defence?

Do states have a right to pre-emptive self-defence?

Opinion + AnalysisPolitics + Human Rights

BY Dr. Gwilym David Blunt 25 JUN 2025

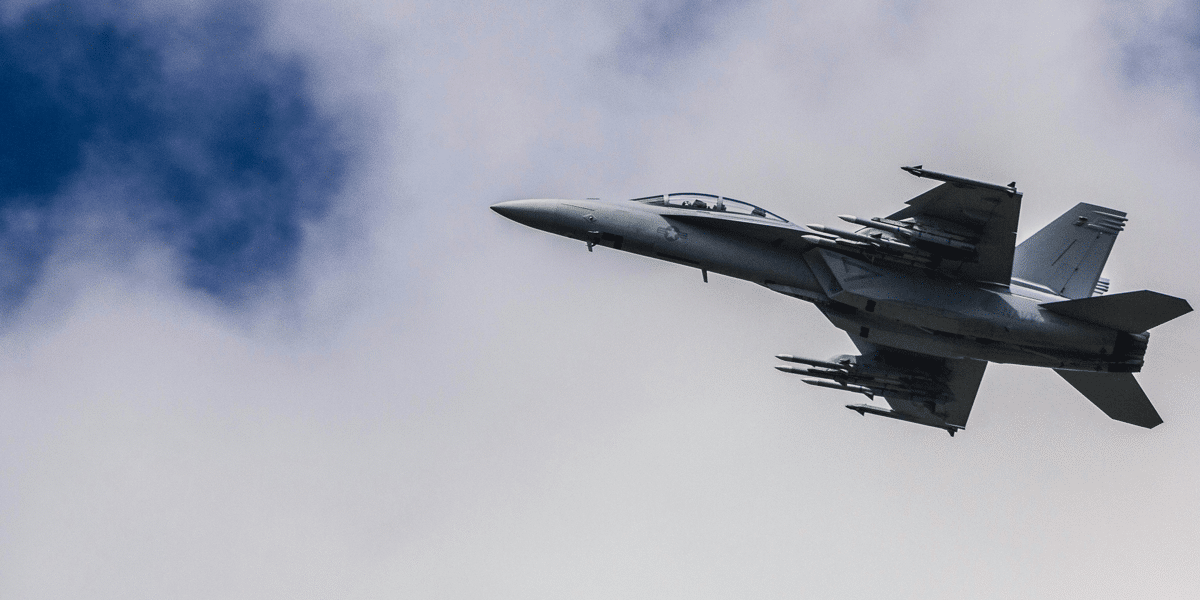

On 13 June 2025, Israel launched an unexpected series of attacks against military and nuclear facilities in Iran.

These attacks killed prominent politicians, military personal, and nuclear scientists, seriously damaging Iran’s air defences and its capacity to develop nuclear technology. A week later, the conflict escalated when the United States attacked heavily fortified nuclear facilities with some of its most powerful conventional weapons. President Trump claimed these strikes ‘obliterated’ Iran’s ability to develop nuclear technology.

The actions of Israel and the US have prompted widespread controversy, including questions about their legality, but I’m not interested in whether they had a legal right to strike Iran, but rather in whether these strikes were ethically justified.

Both Israel and the US have justified their attacks as self-defence. So let’s start with the claim that states have a moral right to self-defence. The realist tradition in international relations and international law often takes this right as read; a state has the right to self-defence qua being a state.

But this doesn’t really satisfy the question for someone interested in global ethics.

I, amongst others, ground the state’s right to self-defence in its status as the primary agent of justice with a responsibility to protect the individual human rights of its citizens against aggression. ‘Aggression’ here is limited to the application of direct military force. But what about circumstances where one hasn’t been attacked yet, but there is strong reason to believe that you will be?

This is where people who work in the ethics of war often employ the ‘domestic analogy’ and try to equate the state’s right of self-defence with an individual’s.

Let’s consider two test cases:

You get into an argument with your neighbour, they lose their temper and cock their fist to punch you. Would you be justified in throwing a punch first?

Second, you and your neighbour have been quarrelling. You hear rumours that they’ve been ‘talking trash’ about you and intimating that they are going to punch you when you least expect it. Would you be justified knocking on their door and punching them in the face?

In the case of the former, it seems ridiculous to say that you need to take the punch if you can stop it from coming, while the latter case seems unjustifiably aggressive. In one case the threat to you is imminent and unavoidable; the blow is coming unless you hit first. In the other case there is no imminent threat; it is in the future and there may be ways of de-escalating the conflict, such as a conciliatory fruit basket, or by calling the police.

If this analysis is correct, then a state may pre-empt an incoming attack when it has reliable intelligence that a hostile neighbour is mobilising for war, but it cannot do so based on the fear of a future attack that may be an unknown time away. In the case of Israel and Iran, it does not seem that Iran was on the cusp of attacking Israel, let alone attacking the United States. It’s analogous to the second test case, not the first.

However, the ‘domestic analogy’ does not seem to accurately encapsulate the ethical dilemmas that states face when considering the use of violence in self-defence.

The international system involves risks far beyond the type posed by personal self-defence, and the state has a responsibility to meet them as part of its duty to protect the rights of those within its borders

The question is whether in June 2025 Iran was able to put the basic rights of Israelis under sufficient threat to justify starting a war? The answer hinges on the prospect of Iran possessing – in the future – a relatively small arsenal of nuclear weapons. This would pose an existential threat to Israel in two ways. The first is their simple but immense destructive power; Israel is not a large country, so a few medium yield nuclear weapons would be enough to destroy its ability to defend itself and would kill potentially millions of non-combatants. Iran, however, does not need to use these weapons for them to be a threat. The second is that their existence would check Israel’s own (unacknowledged) nuclear arsenal and leave it vulnerable to a conventional war from its neighbours in which it would be at a possibly fatal disadvantage. It seems reasonable to say that a nuclear armed Iran would pose an existential threat to Israel’s ability to preserve the rights of those within its borders. However, it must be noted Iran certainly does not pose the same kind of existential threat to those within the USA.

This, however, does not settle the matter, because a key element of self-defence is that it can only occur when all other reasonable alternatives have been exhausted. It seems hard to imagine that this was the case. The Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action agreed in 2015 between Iran, the UN P5+1 and the European Union showed that there was at least a chance for a diplomatic solution to the Iran nuclear issue. This may be viewed as naïve by those who support Israel’s action, that it is the equivalent of hoping a fruit basket would appease the Mullahs, but it is not a wild utopian flight of fancy and these attacks are not without cost.

We must weigh the consequences of stretching the right of self-defence, because it is increasingly coming to look like a fig-leaf for a world where might makes right.

BY Dr. Gwilym David Blunt

Dr. Gwilym David Blunt is a Fellow of the Ethics Centre, Lecturer in International Relations at the University of Sydney, and Senior Research Fellow of the Centre for International Policy Studies. He has held appointments at the University of Cambridge and City, University of London. His research focuses on theories of justice, global inequality, and ethics in a non-ideal world.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights

Housing affordability crisis: The elephant in the room stomping young Australians

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships, Society + Culture

In the face of such generosity, how can racism still exist?

Opinion + Analysis

Climate + Environment, Politics + Human Rights

Australia, it’s time to curb immigration

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

Ethics Explainer: Freedom of Speech

Making sense of our moral politics

Making sense of our moral politics

Opinion + AnalysisPolitics + Human RightsSociety + Culture

BY Tim Dean 17 JUN 2025

Want to understand politics better? Want to make sense of what the ‘other side’ is talking about? Then take a moment to reflect on your view of an ideal parent.

What kind of parent are you – either in reality or hypothetically? Do you want your children to build self-reliance, discipline, a strong work ethic and steel themselves to succeed in a dog-eat-dog world? Do you want them to respect their elders, which means acknowledging your authority, and expect them to be loyal to your family and community? Do you want them to learn to follow the rules, through punishment if necessary, knowing that too much coddling can leave them lazy or fragile?

Or do you want to nurture your children, so they feel cared for, cultivating a sense of empathy and mutual respect towards you and all other people? Do you want them to find fulfilment in their lives by exploring their world in a safe way, and discovering their place in it of their own accord, supported, but not directed, by you? Do you believe that strictness and inflexible rules can do more harm than good, so prefer to reward positive behaviour rather than threaten them with punishment?

Of course, few people will fall entirely into one category, but many people will feel a greater affinity with one of these visions over the other. This, according to American cognitive linguist, George Lakoff, is the basis of many of our political disagreements. This, he argues, is because many of us intuitively adopt a morally-laced metaphor of the government-as-family, with the state being the parents and the citizens the children, and we bring our preconceived notions of what a good family looks like and apply them to the government.

Lakoff argues that people who lean towards the first description of parenthood described above adopt a “Strict Father” metaphor of the family, and they tend to lean conservative or Right wing. Whereas people who lean towards the second metaphor adopt a “Nurturant Parent” metaphor of the family, and tend to lean more progressive or Left wing. And because these metaphors are so embedded in our understanding of the world, and so invisible to us, we don’t even realise that we see the world – and the role of government – in a very different light to many other people.

Strict Father

The Strict Father metaphor speaks to the importance of self-reliance, discipline and hard work, which is one reason why the Right often favours low taxation and low welfare spending. This is because taxation amounts to taking away your hard-earned money and giving it to someone who is lazy. Remember Joe Hockey’s famous “lifters and leaners” phrase?

The Right is also more wary of government regulation and protections – the so-called “nanny state” – because the Strict Father metaphor says we should take responsibility for our actions, and intervention by government bureaucrats robs us of our ability to make decisions for ourselves.

The Right is also more sceptical of environmental protections or action against climate change, because they subvert the natural order embedded in the Strict Father, which places humans above nature, and sees nature as a resource for us to exploit for our benefit. Climate action also looks to them like the government intervening in the market, preventing hard working mining and energy companies from giving us the resources and electricity we crave, and instead handing it over to environmentalists, who value trees more than people.

Implicit in the Strict Father view is the idea that the world is sometimes a dangerous place, that competition is inevitable, and there will be people who fail to cultivate the appropriate virtues of discipline and obedience to the rules. For this reason, the Right is less forgiving of crime, and often argues that those who commit serious crimes have demonstrated their moral weakness, and need to be held accountable. Thus it tends to favour more harsh punishments or locking them away, and writing them off, so they can’t cause any more harm.

Nurturant Parent

From the Nurturant Parent perspective, many of these Right-wing views are seen as either bizarre or perverse. The Nurturant Parent metaphor speaks to the need to care for others, stressing that everyone deserves a basic level of dignity and respect, irrespective of their circumstances.

It also acknowledges that success is not always about hard work, but often comes down to good fortune; there are many rich people who inherited their wealth and many hard working people who just scrape by, and many more who didn’t get the care and support they needed to flourish in life. For these reasons, the Left typically supports taxing the wealthy and redistributing that wealth via welfare programs, social housing, subsidised education and health care.

The Left also sees the government as having a responsibility to protect people from harm, such as through social programs that reduce crime, or regulations that prevent dodgy business practices or harmful products. Similarly, it believes that much crime is caused by disadvantage, but that people are inherently good if they’re given the right care and support. This is why it often supports things like rehabilitation programs or ‘harm minimisation,’ such as through drug injecting rooms, where drug users can be given the support they need to break their addiction rather than thrown in jail.

Implicit in the Nurturant Parent metaphor is that the world is generally a safe and beautiful place, and that we must respect and protect it. As such, the Left is more favourable towards environmental and climate policies, even if they mean that we might have to incur a cost ourselves, such as through higher prices.

Bridging the gap

Naturally, there’s a lot more to Lakoff’s theory than is described here, but the core point is that underneath our political views, there are deeper metaphors that unconsciously shape how we see the world.

Unless we understand our own moral worldview, including our assumptions about human nature, the family, the natural order or whether the world is an inherently fair place or not, then it’s difficult for us to understand the views of people on the other side of politics.

And, he argues, we should try to bridge that gap and engage with them constructively.

Part of Lakoff’s theory is that we absorb a metaphor of the family from our own experience, including our own upbringing and family life. That shapes how we make sense of things, like crime, the environment or even taxation policy. So we are already primed to be sympathetic towards some policies and sceptical of others. When we hear a politician speak, we intuitively pick up on their moral worldview, and find ourselves either agreeing or wondering how they could possibly say such outrageous things.

As such, we don’t start as entirely morally and political neutral beings, dispassionately and rationally assessing the various policies of different political parties. Rather, we’re primed to be responsive to one side more so than the other. As such, we don’t really choose whether to be Left or Right, we discover that we already are progressive or conservative, and then vote accordingly.

The difficulty comes when we engage in political conversation with people who hold a different metaphorical understanding of the world to our own. In these situations, we often talk across each other, debating the fairness of tax policy or expressing outrage at each others naivety around climate change, rather than digging deeper to reveal where the real point of difference occurs. And that point of difference could buried underneath multiple layers of metaphors or assumptions about the role of the government.

So, the next time you find yourself in a debate about tax policy, social housing, pill testing at music festivals or green energy, pause for a moment and perhaps ask a deeper question. Ask whether they think that success is due more to luck or hard work. Or ask whether the government has a responsibility to protect people from themselves. Or ask them which is more important: humanity or the rest of nature.

By pivoting to these deeper questions, you can start to reveal your respective moral worldviews, and see how they connect to your political views. You might not convince anyone to adopt your entrenched moral metaphors, but you might at least better understand why you each have the views you have – and you might not see political disagreement as a symptom of madness, and instead see it as a symptom of the inevitable variation in our understanding of the world. That won’t end your conversation, but it might start a new one that could prove very fruitful.

BY Tim Dean

Dr Tim Dean is a public philosopher, speaker and writer. He is Philosopher in Residence and Manos Chair in Ethics at The Ethics Centre.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture, Business + Leadership

How to tackle the ethical crisis in the arts

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

Israel or Palestine: Do you have to pick a side?

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

The Bear and what it means to keep going when you lose it all

Explainer

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Dignity

Lessons from Los Angeles: Ethics in a declining democracy

Lessons from Los Angeles: Ethics in a declining democracy

Opinion + AnalysisPolitics + Human Rights

BY Dr. Gwilym David Blunt 17 JUN 2025

The first two weeks of June 2025 have seen dramatic demonstrations in the United States against the Trump administration.

Against the backdrop of the President’s campaign of mass deportation, federal agents staged raids at a Home Depot and garment factories in Los Angeles. This triggered spontaneous and sometimes violent protests. Amidst television coverage giving the impression of widespread lawlessness, President Trump deployed some 4,000 members of the California National Guard and 700 U.S. marines – this was done despite the objections of Governor Gavin Newsom, LA Mayor Karen Bass, and the LA Police Department.

This is not unprecedented, but this was the first time troops were deployed on the streets of an American city since the 1992 LA Riots. It was also the first time since 1965 that the Guard was deployed over the objections of a state governor since Lydon Baines Johnson used them to protect citizens marching for civil rights in Alabama.

However, the context matters. These protests in LA in no way matched the scale of the LA Riots of forty years ago, which effectively shut down the city. In 2025 people were still travelling to work; Angelinos were posting photos of family fun from Disneyland. Secondly, Baines Johnson felt the necessity of nationalising the Guard in Alabama because of a widespread organised racist campaign of intimidation against civil rights activists. The was no comparable deprivation of rights in LA (possibly excepting the climate of fear created by Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) agents in the city’s Latino population).

The president has these powers, but they are expected to use them within the norms of ‘democratic restraint’ – they should only be used when there is great urgency. This was plainly not the case, considering the LA protests were effectively contained by the LAPD. Governor Newsom delivered a televised address in which he accused Trump of undermining the norms and institutions of democratic government in the United States and that California was being used to test a broader authoritarian power grab.

America is showing many of the signs of ‘democratic backsliding’. In How Democracies Die, political scientists at Harvard, Steven Levitsky and Daniel Ziblatt, have identified symptoms of a dying democracy. Many people think of military coups and tanks on the streets, but democracies often have slower, less spectacular deaths. Levitsky and Ziblatt show that elected leaders manage to neutralise and co-opt other branches of government; we have seen this with the collapse of moderate voices in the Republican Party and many express deep reservations about the Supreme Court’s independence after the genuinely shocking ruling for Trump v. United States which effectively placed the president above the law.

It is not just the institutional stress, but the growing incivility of civil society that is a concern, because institutions and constitutions do not defend themselves. They require people to unite to support common ways of life.

Americans are now deeply polarised. Political opponents are no longer competitors but enemies, or even traitors, to be silenced. It is impossible to disassociate this from the global pandemic of social media brain rot spreading disinformation, hatred, and conspiracy theories. The erosion of checks and balances coupled with the polarisation of civil society has enabled democratic norms to be slowly eroded to the extent that the President feels able to govern without traditional restraint.

So then what are the duties of citizens in a democracy that, if not dying, is looking terribly ill? This is not a partisan issue, but one that addresses the basic structure of society.

John Rawls wrote in A Theory of Justice, perhaps the greatest work of American political philosophy, that we all have a ‘natural duty’ to build and uphold just social institutions. This is because these institutions are the condition by which we can exercise our minimal autonomy. There is an assumption here that there is something intrinsically valuable about being able to think up and pursue one’s idea of a good life (so long as it doesn’t step on other people’s ability to do the same). You cannot do this if your choices are contingent on the will of a powerful person, whether it is your boss or the president. This is why the founders of the United States opted for a republic over a monarchy as the best guarantee of freedom from domination. It is a matter that should concern all Americans regardless of their political preferences.

Yet, it is a fragile system. On the last day of the Constitutional Convention in 1787, Benjamin Franklin was asked by his friend Elizabeth Willing Powel whether the United States was to be a monarchy or a republic, to which he replied, “a republic if you can keep it”. It is easy to imagine states, especially ones as powerful as the United States, as permanent, but history is a graveyard of states, including many democracies.

What then are citizens to do in circumstances where democracy is failing? We find a suggestion in Franklin’s words. It is up to the people. What makes Franklin’s quote so interesting is that he addressed it to someone who could not even vote: a republic if you can keep it. The suggestion being that all people, even the disenfranchised, share this natural duty to preserve and uphold just institutions. The addressee of Franklin in the 21st century could well be the illegal immigrants who despite being demonised are an integral part of the American economy and society. The protests in LA may have been alarming, but they were a distress call from some of the most vulnerable people in the United States.

The question is how long can this continue? The problem with socialism, Oscar Wilde quipped, is that it takes up too many evenings. The same can be said about resisting authoritarianism. People need to live their lives, you can’t spend every waking hour protesting. Authoritarians know this and take their time eroding the guardrails and poisoning civil society. Trump with characteristic impatience is trying to do in months what took Viktor Orban and Hugo Chavez years to accomplish in much weaker democracies. The experience of the past two weeks may have chastened Trump, but it won’t stop him. The citizens of the United States are in a race against autocracy, but it is not a sprint. It is a marathon.

What every person in the United States, both citizens and non-citizens, must ask themselves is how best can I exercise my natural duty to support just institutions when they are under threat? It is an imperfect duty, meaning that it can be cashed out in numerous ways, but here are 3 suggestions:

- Vote for democracy: In instances of authoritarian capture people must put country above party. When a mainstream party, either of the left or the right, is infected by authoritarianism it is time to find a new political home until the fever breaks.

- Depolarise your politics: Democracies die when people lose what philosopher Michael Oakeshott called a ‘common tongue’ – the shared practices and customs that turns strangers into compatriots. Just as some people must make a new political home, others have a duty to welcome them. Your neighbour is not your enemy, even when you disagree.

- Take it to the streets: Vocal and visible rejection of authoritarianism by a united front reminds people that the decline of democracy is not inevitable; think of the contrast between the aptly named “No Kings” protests and Trump’s farcically shabby birthday parade. Public defiance is essential to maintain the health of civil society.

And it should also be said all of us observing from the sidelines must ask ourselves how we can exercise the same duty to prevent our democracies from going the same way.

BY Dr. Gwilym David Blunt

Dr. Gwilym David Blunt is a Fellow of the Ethics Centre, Lecturer in International Relations at the University of Sydney, and Senior Research Fellow of the Centre for International Policy Studies. He has held appointments at the University of Cambridge and City, University of London. His research focuses on theories of justice, global inequality, and ethics in a non-ideal world.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Big thinker

Politics + Human Rights, Society + Culture

Big Thinker: Slavoj Žižek

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

Israel or Palestine: Do you have to pick a side?

Explainer

Society + Culture, Politics + Human Rights

Ethics Explainer: Just Punishment

Opinion + Analysis

Climate + Environment, Politics + Human Rights

Are we idolising youth? Recommended reads

Do diversity initiatives undermine merit?

Do diversity initiatives undermine merit?

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + LeadershipPolitics + Human Rights

BY Paula McDonald 7 MAY 2025

US President Donald Trump declared earlier this year he would forge a “colour blind and merit-based society”.

His executive order was part of a broader policy directing the US military, federal agencies and other public institutions to abandon diversity, equity and inclusion (DEI) initiatives.

Framing this as restoring fairness, neutrality and strength to American institutions, Trump argued DEI programs “discourage merit and leadership” and amounted to “race-based and sex-based discrimination”.

In Australia too, debates over gender quotas and “the war on woke” have repeatedly invoked meritocracy as a rallying cry against affirmative action.

The narrative of rewards going to the most qualified people is compelling. Yet decades of research show this is flawed. Far from being the great equaliser, an uncritical reliance on “merit” can perpetuate bias and inequality.

The myths of meritocracy

The merit rhetoric invokes the ideal of a neutral, objective system rewarding talent and effort, regardless of identity.

In theory, merit-based evaluations such as exams, performance reviews, employee recruitment processes and competitive bids, should be impartial.

In practice however, there are several myths associated with the notion of merit.

1. Merit is purely objective or unbiased

In the employment context for example, studies show that even so-called objective and standardised cognitive or aptitude tests can systematically favour men due to the type of questions asked.

Decision-makers may unknowingly redefine merit to fit whoever already belongs to a favoured group. A study of elite law firms, for example, found male applicants were rated as more qualified than identical resumes from women.

This is known as “plasticity of merit”, meaning the criteria of excellence can bend to preference, all while appearing objective.

Supposedly merit-based judgments can reflect unconscious bias, or comfort with candidates who fit a traditional mould. Over time, preference may be given to a particular type of candidate irrespective of their actual contribution. Privilege and prejudice can be baked into merit-based evaluations.

2. Merit can be separated from social and historical context

Meritocracy or the so-called meritocratic promise assumes a level playing field, where everyone competes under the same conditions.

In reality however, past inequalities shape present opportunities. What counts as merit is dynamic and socially shaped, not an eternal universal standard.

For example, during the second world war there was a shortage of male workers. Qualities women brought to jobs previously held by men such as capacity for teamwork were suddenly deemed meritorious. But these same qualities were downgraded when the men returned.

Merit is often defined in masculine terms. For example, physicality or hyper-competitive traits have long been seen as prerequisites for military service and policing.

This alignment of masculine norms with standards of merit has been termed “benchmark man”.

Science careers too were built in an era when women were largely excluded. They were predicated on long-hours work and total availability – requirements that clash with caregiving responsibilities. The result is women in STEM careers leave or are pushed out.

3. Outcomes are the result of personal choice or deficiencies, not structural barriers

Meritocracy carries a moral narrative: those at the top earned their place while those left behind didn’t measure up or chose not to compete.

Research shows, for example, that when women don’t advance, it’s explained as lifestyle choices, or they lack ambition, or have opted out to prioritise caregiving.

This narrative wilfully overlooks the structural constraints impacting choices. When a woman “chooses” a lower-paying, flexible job, it may be less about preference than inadequate social supports.

By accepting unequal outcomes as the natural result of individual choices, institutions can conveniently obscure disadvantage and discrimination and erase responsibility to correct inequities.

How the merit mandate undermines equality

Trump’s vision is to remove equity initiatives and programs that monitor or encourage fair hiring and promotion, cease training that alerts employees to hidden biases, and fire or reassign DEI staff.

This is conceptually flawed and will actually entrench the very biases and barriers that have kept institutions unequal.

In the military, for example – an area highlighted by Trump – leaders have recognised they need to foster more inclusive cultures.

For years, defence forces have grappled with sexual harassment, recruitment shortfalls and retention of skilled personnel. In Australia, the Australian Defence Force undertook major reviews to identify violent and sexist subcultures, understanding a more inclusive force is a more effective force.

Yet Trump’s order bars the Pentagon from even acknowledging historical sexism in the ranks.

Favouring the in-group

Removing equity measures under a banner of neutrality means hiring and promotion will increasingly rely on informal networks and subjective judgements. These can tilt in favour of the in-group – usually white, male and affluent.

DEI initiatives can increase representation of women, or people from diverse racial or cultural backgrounds, in an organisation or occupational group.

However, without challenging the norms of merit, or without broadening the definitions of talent and leadership, people in those groups may continue to feel like outsiders.

Australian experts and business leaders increasingly acknowledge objective merit is mythical.

Redefining merit

Fair rewards for effort can improve performance. However, we need to stop pitting merit against diversity. True fairness requires acknowledgement structural inequality exists and bias affects evaluations.

Organisations need to re-imagine merit in ways that work with inclusion, rather than against it. This includes refining hiring and promotion criteria to focus on competencies that are measurable and relevant.

This article was originally published in The Conversation.

BY Paula McDonald

Paula McDonald is Professor of work and organisation and Director of the Work/Industry Futures Research Program in the QUT Business School. Prior to an academic career, Paula held clinical and research roles in health sector settings including child and adolescent psychiatry, medical education, primary care and public health. She is a registered psychologist with the Australian Health Practitioner Regulation Agency.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Big thinker

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Big Thinker: Mary Wollstonecraft

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Managing corporate culture

Reports

Business + Leadership

A Guide to Purpose, Values, Principles

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights

Australia is no longer a human rights leader

Ethics Explainer: Moral Courage

Ethics Explainer: Moral Courage

ExplainerSociety + CulturePolitics + Human Rights

BY The Ethics Centre 29 APR 2025

Martin Luther King Jr, Rosa Parks, Frederick Douglass, Susan B. Anthony, Greta Thunberg, Vincent Lingiari, Malala Yousafzai.

For most, these names, and many more, evoke a sense of inspiration. They represent decades and centuries of steadfast moral conviction in the face of overwhelming national and global pressure.

Rosa Parks, risking the limited freedom she was afforded in 1955 America, refused to acquiesce to the transit segregation of the time and sparked an unprecedented boycott led by Martin Luther King Jr.

Frederick Douglass, risking his uncommon position of freedom and power as a Black man in pre-civil rights America, used his standing and skills to advocate for women’s suffrage.

There have always been people who have acted for what they think is right regardless of the risk to themselves.

This is moral courage. The ability to stand by our values and principles, even when it’s uncomfortable or risky.

Examples of this often seem to come in the form of very public declarations of moral conviction, potentially convincing us that this is the sort of platform we need to be truly morally courageous.

But we would be mistaken.

Speaking up doesn’t always mean speaking out

Having the courage to stand by our moral convictions does sometimes mean speaking out in public ways like protesting the government, but for most people, opportunities to speak up manifest in much smaller and more common ways almost every day.

This could look like speaking up for someone in front of your boss, questioning a bully at school, challenging a teacher you think has been unfair, preventing someone on the street from being harassed or even asking someone to pick up their litter.

In each case, an everyday occurrence forces us to confront discomfort, and potentially danger or loss, to live out our values and ideals. Do we have the courage to choose loyalty over comfort? Honesty over security? Justice over personal gain?

The truth is that sometimes we don’t.

Sometimes we fail to take responsibility for our own inaction. Nothing shows this better than the bystander effect: functionally the direct opposite to moral courage, the bystander effect is a social phenomenon where individuals in group or public settings fail to act because of the presence of others. Being surrounded by people causes many of us to offload responsibility to those around us, thinking: “Someone else will handle it.”

This is where another kind of moral courage comes into play: the ability to reflect on ourselves. While it’s important to learn how and when to speak up, some internal work is often needed to get there.

Self-reflection is often underestimated. But it’s one of the hardest aspects of moral courage: the willingness to confront and interrogate our own thoughts, habits, and actions.

If someone says something that makes you uncomfortable, the first step of moral courage is acknowledging your discomfort. All too often, discomfort causes us to disengage, even when no one else is around to pass responsibility onto. Rather than reckon with a situation or person who is challenging our values or principles, we curl up into our shells and hope the moment passes.

This is because moral courage can be – it takes time and practice to build the habits and confidence to tolerate uncomfortable situations. And it takes even more time and practice to prioritise what we think is right with friends, family and colleagues instead of avoiding confrontation in relationships that are already often complicated.

It can get even more complicated once we consider all of our options because sometimes the right ways to act aren’t obvious. Sometimes, the morally courageous thing to do is actually to be silent, or to walk away, or to wait for a better opportunity to address the issue. These options can feel, in the moment, akin to giving up or letting someone else ‘win’ the interaction. But that is the true test of moral courage – being able to see the moral end goal and push through discomfort or challenge to get there.

The courage to be wrong

The flipside to self-reflection is the ability to recognise, acknowledge and reflect with grace when someone speaks up against us.

It’s hard to be told that we’re wrong. It’s even harder to avoid immediately placing walls in our own defence. Overcoming that is the stuff of moral courage too – not just being able to confront others, but being able to confront ourselves, to question our understanding of something, our actions or our beliefs when we are challenged by others.

Whether these changes are worldview-altering, or simply a swapping of word choice to reflect your respect for others, the important thing is that we learn to sit with discomfort and listen. Listen to criticism but also listen to our own thoughts and figure out why our defences are up.

Because in the end, moral courage isn’t just about bold public stands. It’s about showing up—in big moments and more mundane ones—for what’s right. And that begins with the courage to face ourselves.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Explainer

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Critical Race Theory

Big thinker

Society + Culture

Big Thinker: Philippa Foot

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Why we should be teaching our kids to protest

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

Bring back the anti-hero: The strange case of depiction and endorsement

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Lies corrupt democracy

One of the most potent threats to democracies is that their elections will be corrupted by lies.

No matter how attenuated in practice, the defining feature of democracies is that the exercise of power is conditional upon the consent of the governed. Consent confers authority. Without consent the exercise of power depends not on democratic legitimacy but instead on the brute force of the autocrat.

For consent to be meaningful, it must be informed. And nothing can be ‘informed’ if it is based on falsehood routinely peddled by those who deal in misinformation and disinformation.

There is nothing new in this. Since antiquity, citizens have always been susceptible to manipulation to skew political outcomes. The difference, today, lies in the speed at which a lie can spread and the breadth of the audience it can reach in an instant. There are also so few individuals or institutions who are trusted to guard and uphold the truth.

Ideally, we might hope that politicians would offer the first line of defence of truth. After all, they have a duty to prioritise the public interest ahead of personal or party interests. Few aspects of the public interest are as important and as obvious as the need to assure the integrity of our democratic elections. Politicians who lie fundamentally undermine the integrity – and therefore the legitimacy – of our elections. In doing so, they betray the public interest.

Despite this, Australia imposes very few penalties on politicians or parties who deliberately lie. This reluctance to punish falsehood is, in part, due to an equal commitment to free speech. We are right to be cautious about introducing measures that restrict free speech for fear of being punished for saying the ‘wrong thing’. It may also be the case that our legislators have a shared interest in not creating a ‘rod’ for their own backs – especially when they can see political advantage in being ‘economical with the truth’.

So, we largely depend on politicians to regulate themselves – with the apolitical Australian Electoral Commission left to manage the worst cases of misinformation and disinformation.

The good news is that politicians are mostly truthful. The bad news is that there are other actors, in the political space, who deliberately seek to manipulate the electorate by manufacturing and propagating misinformation and disinformation. Some of those responsible are state actors who seek to harm countries like Australia by creating or exploiting divisions. They are skilled at using our open information systems as vectors to create states of alarm, confusion and uncertainty – all of which introduces structural weakness and a reduced ability to mount a strong, united response to challenges. Other actors use misinformation and disinformation to advance their ideological or economic interests – by tilting an election in favour of their preferred outcome.

Unfortunately, this kind of interference is now common. Paradoxically, the more it is exposed, the greater the loss of trust in the information presented to us. And that suits the enemies of democracy very well. When a picture or video can be manipulated to the point where you cannot distinguish reality from fiction; when the voice on a phone call is a ‘clone’ based on a thirty second clip – yet is entirely credible; when nothing can be guaranteed to be what it seems to be – how, then, does a voter ever know that they are making an informed decision?

That problem has been solved by financial markets (which also depend on informed decision making) through the profession of auditing. Auditors belong to the profession of accounting. As such, they stand adjacent to the world of the ‘market’ which formally approves the pursuit of self-interest in the satisfaction of the wants of others. The profession of accounting is made up of people who freely choose to abandon the pursuit of self-interest in service of the public interest and a higher ‘good’ – namely the truth.

The role that accountants play in markets is mirrored by the role that journalists are supposed to play in politics – and especially in democracies. Unfortunately, just as some merchants can be relied upon to resort to deception in the pursuit of profits, so can some politicians be relied upon to do the same in the pursuit of victory. Professional journalists are supposed to help protect society from that risk – which is why they are so often lauded as the ‘fourth estate’.

In order to ensure the integrity of our democracy, we need politicians who can be trusted not to lie (even when it advantages them). We need regulators with increased power to identify, curb and punish the activities of those who lie and deceive. We need journalists who place their commitment to the disinterested pursuit of truth ahead of personal or commercial self-interest. We need to be able to distinguish between those who abuse the title ‘journalist’ as false cover and those who genuinely deserve to be trusted. Finally, we need to rally behind and reward media outlets that employ truth-tellers and cease engaging with those who treat the truth as a mere ‘optional extra’.

Fortunately, there are some amongst the political class who are taking steps to encourage truth in politics. A recent initiative, The Ethical Political Advertising Code (EPAC) affords an opportunity for people seeking election to make a public commitment to ‘truth in political advertising’.

Sponsored by Zali Steggall MP, this is a cause that should be apolitical in character – hopefully enjoying the support of any person who cares about the character and quality of our democracy. But this is not just a matter for politicians. It is also something that affects us all.

That is our test as citizens – to choose truth over mere entertainment, to prefer fact to falsehoods that pander to our prejudices.

With so much now at stake in the world, this is a test we must pass. But will we?

BY Simon Longstaff

After studying law in Sydney and teaching in Tasmania, Simon pursued postgraduate studies in philosophy as a Member of Magdalene College, Cambridge. In 1991, Simon commenced his work as the first Executive Director of The Ethics Centre. In 2013, he was made an officer of the Order of Australia (AO) for “distinguished service to the community through the promotion of ethical standards in governance and business, to improving corporate responsibility, and to philosophy.”

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights

Why fairness is integral to tax policy

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Whose home, and who’s home?

Explainer

Society + Culture, Politics + Human Rights

Thought experiment: The original position

Opinion + Analysis

Climate + Environment, Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

A burning question about the bushfires

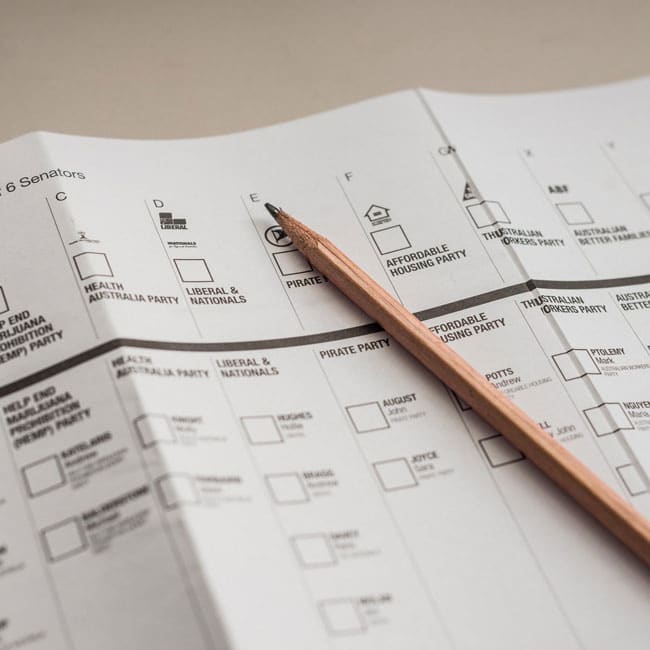

A critical thinker’s guide to voting

A critical thinker’s guide to voting

Opinion + AnalysisPolitics + Human RightsRelationships

BY Dr Luke Zaphir 14 APR 2025

In Australia, we have no formalised method of teaching people about politics, voting and elections. Most people vote the same way as their parents in their first elections, and won’t receive any more education beyond how-to-vote cards and electoral ads.

People under the age of 25 make up about 10% of all voters – that’s about ten thousand per electorate. They’re the most underrepresented group in political discourse and in elections. Not only that but young people will have to live with the consequences of these policies far longer than any other demographic.

Given that some elections come down to only a few hundred votes, the way we vote really does matter.

Our votes matter beyond the current election – they affect future elections too. The Australian Electoral Commission provides funding for every candidate or group that receives more than 4% of first preference votes. This means that even small groups can become big factors, influencing future elections and swaying the balance of power in parliament.

Finally, democracy works because it’s about communicating our needs and visions of the future. The major parties pay attention to how and why people vote. The Labor and Liberal parties have issues that they care about but others they overlook. A vote can shift the way the policy platforms of the major parties to discuss the issues we care about.

Here is a practical guide to critically think about your vote.

Step 1: Ignore the hype

Political parties are really good at demonising each other. They’ll accuse each other of being craven, lying, baby eating monsters. None of this is useful information. Almost every piece of political messaging from every party is propaganda designed to get your vote. They’ll frame the issues in terms of economics, jobs, the environment or tradition. This anchors our thinking in a way that is unhelpful for choosing a candidate, making it difficult to consider nuance and complexity.

Step 2: Value democratic integrity

Our democracy cannot function if our representatives are known liars, are demonstrably corrupt, or engage in unscrupulous mudslinging against other candidates. Everyone believes they are morally correct but if the candidate spends their time hurling insults, they’re actively toxic to our democracy. If the candidate is willing to say or do anything to get elected, they can’t be trusted to further the public good and should come last on the ballot.

Our democracy only functions if its processes are open, fair and honest. Recent changes to the ways political candidates are allowed to fundraise means that it may be easier for incumbents to stay in power, and harder for newcomers to challenge them. It’s worth looking into whether your member of parliament supported these changes, or aims for a level playing field.

Step 3: Think about your values

The most fundamental part of knowing who to vote for is knowing what your values are. There are an endless number of beliefs that we might hold. We might believe in universalism and benevolence (welfare for all, tolerance and understanding), which lead to policies like a universal basic income, investment in public broadcasters like the ABC, and increasing foreign aid. Values such as self-direction and achievement are more important to us (pursuing and gaining personal success) lead to policies that minimise taxation and deregulation. Voting against same-sex marriage or changes to the constitution to include First Peoples are examples of valuing tradition, whereas policies that block foreign investment or advocate turning back asylum seeker boats prioritise security.

There’s no such thing as ‘having bad values’, but it’s important to know what we believe, why we believe it, and prioritise these when it comes to elections. Ask yourself how important each of your principles and goals are in turn, and if your vote will move you further towards them.

Step 4: Think about what you’d like for the country

Now that you understand your values, think about how they inform the kind of country you want Australia to become. Political parties offer massive packages of policies containing aspects we agree with or may not like. Vote compasses can be useful at this point in this task – they have specific policy directions that allow us to precisely target what we would want to achieve in the country. This is an important step because we might agree with a party’s stated views but if their policies don’t match up, we’re not going to be represented well.

It’s common to agree with only part of a party’s political package. This is why we need to learn about all the candidates’ parties, their aims, and which best aligns with our own views. Preferential voting is a way of creating an order of best fit – with your number 1 preference going to the party that most aligns with your views, and each subsequent preference being the next best fit. The party that least represents your views should get your last preference.

Step 5: Learn about the parties

Labor and the Liberals are the most powerful and oldest parties in Australia. They aren’t exactly the same platforms as they once were, which is why second hand information from others may be out of date. The Greens are also a significant party and often hold the balance of power in the Legislative Assembly. There are many other parties that will be in your division and it’s worth looking into what they value and what their aim is specifically. There are many parties that focus on single issues that are important to them.

Step 6: Discover the candidates’ credentials and goals

The Australian Electoral Commission provides information about all currently enrolled candidates. Additionally, blogs like The Tally Room track candidates for each division and provide links to all of their personal websites.

A person’s qualifications and work history will tell us a bit about who someone is. Do they own a business? Ran a not-for-profit? Have they been a teacher or academic or front line retail worker? Have they been bankrupt? This is useful for telling us what kind of person we’re voting for and how they think.

Another important aspect is how clearly they’ve articulated their goals. Every party is in favour of good economic management, green technology and low unemployment figures. What matters is which they prioritise given the current context. It’s also worth considering what they plan in the long term – do they have a vision for Australia in 20 years? In 50? A party that only sees the future one electoral cycle ahead is one that will make short sighted decisions.

Lastly, if they can’t concisely say that they aim to enact a specific law or to increase a certain tax, we have reason to question their competence. A candidate can talk about the value of freedom all they want – without a stated goal, they either haven’t thought about it or they’re dog whistling.

Step 7: Judge the incumbent’s track record

The member of parliament for your division has a higher burden for gaining re-election because they have to defend their record. What have they done so far? What have they accomplished? How have they voted in the House of Representatives or Senate? Hansard is the official record of parliamentary speeches and votes. They Vote for You is a not-for-profit independent non-partisan organisation which tracks how the current member of parliament has voted (from Hansard). This includes their attendance (how often they do their job), and what they vote consistently for and against. This is particularly useful for us if we care about a specific issue – we can discover if the sitting member supports or votes against it in parliament.

A final thought

There are no wrong choices except those which are made with inaccurate information. This guide will take less than an hour and that’s not much to be conscientious about your vote once every three years. Democracy isn’t just about voting. It is in our civil discourse itself and how we share our perspectives.

Think about whether the status quo should stay the same or change based on your values and goals, then vote for the candidate that you believe represents your view. When you talk to people about who you’re voting for, be curious about their values and their perspective. From these together, you’ll have a thoughtful and well considered perspective.

This article has been updated since its original publication in 2022. Image by AEC photo.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Climate + Environment

What we owe each other: Intergenerational and intertemporal justice

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture, Politics + Human Rights

‘The Zone of Interest’ and the lengths we’ll go to ignore evil

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

You’re the Voice: It’s our responsibility to vote wisely

Opinion + Analysis

Climate + Environment, Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

The dilemma of ethical consumption: how much are your ethics worth to you?

BY Dr Luke Zaphir

Luke is a researcher for the University of Queensland's Critical Thinking Project. He completed a PhD in philosophy in 2017, writing about non-electoral alternatives to democracy. Democracy without elections is a difficult goal to achieve though, requiring a much greater level of education from citizens and more deliberate forms of engagement. Thus he's also a practicing high school teacher in Queensland, where he teaches critical thinking and philosophy.

Ask an ethicist: Why should I vote when everyone sucks?

Ask an ethicist: Why should I vote when everyone sucks?

Opinion + AnalysisPolitics + Human Rights

BY Simon Longstaff 10 APR 2025

As time goes on, I’m feeling more disenfranchised by politics. I don’t trust any of the current politicians and it seems they don’t represent issues that are affecting everyday Australians, particularly as the inequality gap is widening. Why should I vote this upcoming election, and does my vote even matter?

The issue of voting in Australian elections is often clouded by the mistaken belief that ‘voting is compulsory’. This really annoys people who feel that it impinges on their liberty as citizens – a liberty that should include the right to decide not to vote. In fact, Australia does not impose ‘compulsory voting’. Instead, there is a policy of ‘compulsory turning up’. What we do when we enter the privacy of the polling booth is entirely up to us. We can cast a valid vote. We can leave the ballot paper unmarked. We can write a screed setting out our views. Basically, we can do whatever we like – just as long as we turn up, collect the voting papers and deposit them in the ballot box.

Some will still object to the need to turn up. It won’t matter to them that the need to do so is one of a very small set of obligations that our country has imposed on all its citizens to maintain a well-functioning democracy.

But let’s just assume that, either willingly or reluctantly, we find ourselves in the polling booth – ballot papers in hand – and have to decide whether or not to cast a valid vote. What should we have in mind as we decide?

First, it’s worth remembering that democratic elections do have the potential to bring about change. If we feel that something is wrong with society, then the vote you cast can, in principle and sometimes in practice, enable reforms for the better. It’s understandable to think that your individual vote might not amount to much. But the arc of history is directed by the aggregated effect of individual votes. Alone, this might not amount to much, but collectively it can change the world. Indeed, the fate of a government can sometimes rest on a foundation as fragile as a single vote in a marginal electorate.

Of course, not all of us live in marginal electorates. In apparently ‘safe’ seats it might seem like your vote will be wasted if you cast it for a candidate who apparently has no chance of beating the likely ‘favourite’. Yet, this thinking runs the risk of becoming self-fulfilling. You never know what might happen if just enough people make the same choice you do – and in doing so bring about an unanticipated victory for a candidate who seemed to have no chance of winning. There are many examples of once ‘safe’ seats being lost by major parties that have held them for generations. Just look at the rise in the number of community independents now sitting in our parliaments. They are only there because a majority of citizens preferred them to others and voted accordingly.

It can also work the other way – where you vote for a candidate who apparently already has enough votes to win. Your vote is not ‘redundant’ because the size of a candidate’s margin of victory can be seen as indicative of community support. A larger margin can lend a representative a greater mandate or more political capital to enact their agenda.

Another problem might be that there is not a single candidate or party that you could support in good conscience. There may not even be a ‘least bad’ (but acceptable) option. In any case, with preferential voting there are no ‘wasted votes’. Every ballot counts towards the eventual result. That is one of the problems with choosing to vote ‘informally’ (returning an unmarked ballot). Doing so will make no positive difference to the outcome. The only ‘upside’ is that you might feel that you avoid complicity in enabling an outcome that you could not support in any case.

Yet, perhaps part of our role as electors is to accept that there will be times when the best we can hope for is the ‘least bad’ result. We may have to reconcile ourselves to the fact that there will be occasions when nothing truly inspiring is on offer. If we’re denied the opportunity to vote for someone who reflects our values and principles – and advances our view of what makes for a good world – we might still see value in using our vote to help block those who would undermine everything we stand and hope for.

This brings us to one of the core reasons for voting. Unlike other political systems where authority is derived from God (theocracies) or wealth (plutocracies) or ‘virtue’ (aristocracies), in democracies the ultimate source of authority comes from those who are ‘the governed’ (the people). We get to decide how decisions are made – through popular control of what is in our Constitution. We also get to choose the representatives who will make laws on our behalf. In the end, we have as much control over the system of government as we choose to exercise.

What limits the exercise of that control is not the system – it is our willingness to become politically active.

If you like living in a democracy – but don’t want to get too involved in shaping the system – then there is a low-cost, potentially high impact way to help shape the way it operates. It is to vote.

Image: Gillian van Niekerk / Alamy Stock Photo

BY Simon Longstaff

After studying law in Sydney and teaching in Tasmania, Simon pursued postgraduate studies in philosophy as a Member of Magdalene College, Cambridge. In 1991, Simon commenced his work as the first Executive Director of The Ethics Centre. In 2013, he was made an officer of the Order of Australia (AO) for “distinguished service to the community through the promotion of ethical standards in governance and business, to improving corporate responsibility, and to philosophy.”

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

If you don’t like politicians appealing to voters’ more base emotions, there is something you can do about it

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships, Society + Culture

The sticky ethics of protests in a pandemic

Big thinker

Politics + Human Rights

Big Thinker: Hannah Arendt

Big thinker

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Big Thinker: Michel Foucault

A good voter’s guide to bad faith tactics

A good voter’s guide to bad faith tactics

Opinion + AnalysisPolitics + Human Rights

BY Dr Luke Zaphir 1 APR 2025

Political campaigns are mechanisms of persuasion – they aim to convince you to give them your vote.

However, they often use underhanded and bad faith tactics – not because they’re sneaky (though they can be) but because humans don’t naturally process and interpret information rationally.

This isn’t usually bad news for us – by thinking more quickly and reactively, we’re able to identify threats and safety immediately. But when it comes to elections, thinking logically is a different beast altogether. We have to slow down our thoughts, order information, make connections between ideas, discern truth from lies.

Political messaging relies on us using our simple thinking habits rather than the more rational process. Mean-spiritedness, name-calling, and catch-phrases are all tactics used to make us unconsciously lean towards or against voting for someone. Some strategies are deliberately designed to put us into specific emotional states – like anger or fear – to coax us into agreeing with the politician.

It’s more important now than ever that we recognise the tactics and strategies used so we can avoid being reactive and non-deliberative when voting. By slowing down our thinking – being more rational, and processing our emotions after we’ve examined a political message, we can come to the best possible decision come election time.

Here are some tactics that are often used, and tools that can help us combat them:

Branding and slogans

Slogans – especially catchy rhyming ones – make political messages easy and fast to understand. “Back on track” is being used by the Liberal Party in Australia this year, with “Building Australia’s Future” as the Labor party’s mantra. You might have heard an assortment of even simpler brands like “woke”, “groomer”, “degeneracy” or “traditional”.

These phrases are meant to be emotionally evocative and more importantly, be easily repeated. When scrolling social media, it’s far more likely that a person will absorb this idea unconsciously and feel a certain way. “Building Australia’s Future” evokes a sense of optimism in the audience. Similarly, “Australia Back on track” has an embedded sense of hope but also includes a slight sense of unease about the current system. Anxiety guides the thought – and it’s more likely that we won’t be thinking too deeply about which policies we agree with or what where we’d like the country to go.

At a minimum, branding and slogans don’t allow for nuanced conversations. Engagement goes up, but deep understanding goes down.

What you can do: Be mindful of your emotions

All political advertising is designed to make us feel a certain way. After reading or watching the content, check in with yourself. What are you feeling right now? Optimistic? Slightly anxious? Outraged? Recognise that the ad meant to evoke that and influence you.

Avoid taking the emotional bait. Try to avoid reacting and instead take a moment to consider why they’ve chosen that feeling for the ad. Positive emotions aim to build loyalty and trust, whereas negative emotions create a sense of urgency and amplify the downsides. Finally stay objective – consider what it is that’s factually true about this issue.

Priming

Priming is the practice of putting people in a certain frame of mind before discussing a political issue. For example, a common and volatile topic of debate is that of transgender people in sports. We often see public outcry at how unfair it is to have transgender women competing against cisgender women – transgender athletes are seen as having unfair biological advantages at best, or are ‘pretending’ to be women at worst – all just for a win.

This topic has been primed in a certain way – primed to lean on preexisting ideas of fairness and gender.

It’s reasonable to have strong feelings about what makes sports fair after all. But how would the conversation change if it started by talking about the bullying transgender people endure just for trying to play sports? What if the discussion started with the disproportionate mental health struggles they face compared to the wider population? This priming shifts the tenor of the entire conversation.

An argument that needs priming is one that is playing on our prejudices and biases – an obvious sign of a weak and unconvincing argument. Compelling ideas don’t need to rely on this kind of tactic to be persuasive.

What you can do: Reframe your thinking

After engaging with the material, take a moment to reflect. Are you being led to support a specific side? Are you valuing one piece of evidence more than another?

Avoid jumping to conclusions based on the presented viewpoint. Instead, ask yourself why the content is framing certain ideas favourably. Balanced content usually considers multiple perspectives while biased content steers you toward one.

Framing

Framing shapes how we see an issue, often making it seem overly simple or emotional. For example, the term ‘pro-life’ frames opponents as ‘anti-life,’ which is misleading. Abortion as a topic is filled with complex ideas around bodily autonomy, medical privacy, and beliefs around when life begins – framing this issue as simple removes all ability to explore it with any nuance.

Another way framing can be harmful is that it encourages feeling, rather than thinking. Fear of immigrants is a classic tactic used for hundreds if not thousands of years, and Australian politics is no different. Immigrants are depicted as a threat to jobs, culture and safety. The fear frame is meant to get people feeling like there’s an imminent danger when facts and common sense say otherwise.

What you can do: Deepen your thinking about the world and understanding of yourself

Consider whether you’re being encouraged to examine the complexities of an issue or merely agree with a simplified viewpoint. Recognise that interactions, such as liking or sharing or responding to a post, will amplify the original idea – even if you disagree with it.

Avoid simply nodding along. Instead, take the time to reflect on the broader implications, possible outcomes, and alternative perspectives. Be open to being wrong and ready to hear differing opinions.

Also consider whether you’re being pressured to conform to a single group, person, or ideology. “Us vs them” narratives rarely reflect our complexities as people or societies. Messages that simplify to that degree focus on our differences, rather than attending to our common problems.

No identity or belief system is infallible or beyond criticism – our own beliefs are our biggest blind spot. Embrace the diversity within yourself and others, acknowledging that multiple perspectives can coexist and contribute to a richer understanding of the world.

Image: Martin Berry / Alamy Stock Photo

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

What do we want from consent education?

Explainer

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights

Ethics Explainer: Universal Basic Income

Opinion + Analysis

Climate + Environment, Politics + Human Rights

Australia Day: Change the date? Change the nation

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

A critical thinker’s guide to voting

BY Dr Luke Zaphir

Luke is a researcher for the University of Queensland's Critical Thinking Project. He completed a PhD in philosophy in 2017, writing about non-electoral alternatives to democracy. Democracy without elections is a difficult goal to achieve though, requiring a much greater level of education from citizens and more deliberate forms of engagement. Thus he's also a practicing high school teacher in Queensland, where he teaches critical thinking and philosophy.

An angry electorate

I recently attended a gathering of people who engage with a remarkably diverse range of Australians.

Members of this group are directly connected with both the wealthiest and poorest in society. Some are city folk; others firmly grounded in the lives of rural, regional and remote communities. They told of the experience and attitudes of people whose circumstances vary considerably – from the most secure to the most precarious in the land.

Remarkably, when asked about the ‘mood’ of the electorate, all told a similar story. Across all demographics, people are disappointed, frustrated and angry. Some of these feelings understandably arise out of the clear failure of our society to meet even the most basic needs of its members. For example, we were told of a regional city, in New South Wales, where 26% of the community are now experiencing food insecurity. That is, a quarter of the population experiencing days where they do not know if they will be able to secure the food they or their family need. We heard of young people – some from relatively affluent families – who doubt that they will ever be able to afford the ‘Australian Dream’ of a home of their own. For some, if not for all, the word ‘crisis’ is an entirely apt description of what far too many people are experiencing.

However, what this cannot explain is the anger felt by even the most affluent.

The seat of the fire is located in a shared (and growing) sense that too many of our politicians and media are ‘fiddling while Rome burns’. Instead of being wholeheartedly focused on the interests of the community, our leading politicians are perceived as being engaged in the trivial game of political-point-scoring, in pursuit of power for its own sake – rather than as a means for realising a larger vision of what could or should be.

This kind of anger is hard to extinguish. There comes a point when even a good policy is discounted by a public that cynically questions the politicians’ motives. This cynicism is exacerbated by a style of politics that is becoming increasingly partisan. One might reasonably doubt that there was ever a ‘golden age’ of politics in Australia. But the decline in widespread public participation in political parties has meant that a relatively small number of factionalised ideologues can take control of a major party. The way the numbers work, they can push increasingly extreme views – unhindered by the ‘sensible middle’ that used to prevail when major political parties really were ‘broad churches’.

I mention all of this because, as we know all too well in Australia, a single ember can easily give rise to a destructive conflagration.

My sense is that the Australian political landscape is bone dry, with the electoral tinder piling up. In this angry environment, one can foresee a moment of nihilistic abandonment; when the idea of ‘burning it all to the ground’ just might catch on.

This we have seen happen in other parts of the world. If only mainstream America had listened attentively to the complaints of people who genuinely felt abandoned by those occupying ‘the swamp’ in Washington DC. Ignored or labelled ‘deplorables’, President Trump became their ‘agent of destruction’. The same forces were at work in the Brexit referendum. A number of those who voted for leaving the EU doubted that their lives would improve. Instead, they took comfort in the fact that those who looked down on them would be worse off.

Our political elite must accept their fair share of responsibility for the increasing level of anger directed at the ‘system-as-a-whole’. However, as citizens of a democracy, we also have a critical role to play. While we might not be able to control our external environment, we are responsible for our response. Knowing what can happen when anger is let loose at its destructive worse, we need to exercise careful restraint and not enflame the situation.

Australian democracy has many faults. And there are plenty of people who have borne the burden of its failures. But it has also helped to sustain one of the world’s better societies. My hope is that politicians – irrespective of party or political persuasion – might take a moment to look beyond party or personal self-interest to ask if their conduct is strengthening or weakening our democracy in the eyes of the electorate. Democratic institutions are not the property of any government, party or faction. They belong to and are exclusively to be used for the benefit of the people. Those who tarnish or degrade those institutions are guilty of public vandalism. So, let’s hold those who do this individually responsible rather than abandon faith in our entire system of democratic governance. And if it happens to be the case that the problem is the system (as may be the case), then let’s work together to decide what would be better – and then build towards that positive outcome.

In turn, we need to dampen down the fires of anger – not be blinded by the smoke of our righteous indignation – no matter how justified it might be. We need a clear vision of what we think makes for a good society. And then we need to elect those who would help us to build rather than tear down.

BY Simon Longstaff

After studying law in Sydney and teaching in Tasmania, Simon pursued postgraduate studies in philosophy as a Member of Magdalene College, Cambridge. In 1991, Simon commenced his work as the first Executive Director of The Ethics Centre. In 2013, he was made an officer of the Order of Australia (AO) for “distinguished service to the community through the promotion of ethical standards in governance and business, to improving corporate responsibility, and to philosophy.”

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

Why Anzac Day’s soft power is so important to social cohesion

Big thinker

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Big Thinker: Confucius

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

Ethics Explainer: Freedom of Speech

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships