To Russia, without love: Are sanctions ethical?

To Russia, without love: Are sanctions ethical?

Opinion + AnalysisPolitics + Human RightsRelationships

BY Isabella Vacaflores 11 MAR 2022

The western world has responded to Russia’s unprovoked invasion of Ukraine by imposing a historically large suite of economic sanctions upon them. Are such measures likely to cripple the kremlin, or are they merely wreaking havoc on the lives of innocent civilians?

Following the invasion, Lina, a 21-year-old living in Russia, found herself suddenly locked out of her OnlyFans account. Her loss of livelihood and income as an adult content creator was a direct consequence of comprehensive sanctions imposed upon her country. Taking to Twitter to voice her discontent, Lina wrote “I don’t support this war, but I became its hostage”.

Although OnlyFans has since reinstated Russian owned accounts, this has not stopped ordinary citizens from being caught in the crossfire of a war they do not necessarily condone. The rapidly plummeting value of the ruble coupled with aggressive boycotts has seen the cost of living skyrocket, causing many to question who is truly paying for this war.

Porn stars and geopolitics are worlds apart, as are innocent civilians and armed combatants. Universally recognised international humanitarian law tells us that jus in bello (justice in war) means protecting people not involved in the conflict from unnecessary hardship. The use of economic sanctions as an alternative to boots on ground intervention has challenged this principle, punishing everyone from the oligarchy to sex workers in one fell swoop.

Russia is a relatively impoverished, repressed, socioeconomically divided and bellicose country. The average citizen does not enjoy the same social and economic freedoms as those in the nations that sanction them. Such diplomatic measures might seem unethical because they have the potential to make innocent lives even more miserable – so why is the international community so trigger-happy when it comes to implementing them?

Sanctions in brief

The latent power of sanctions as a tool of foreign policy was revealed through the Blockade of Germany during WWI, where the restriction of maritime goods by naval boats played a crucial role in securing victory for the Allies. Taking this lesson into their stride, the League of Nations (superseded by the United Nations) began threatening the use of an “economic weapon” to reign in troublesome countries such as Italy and Japan, mostly unsuccessfully.

Using a mix of coercive tools ranging from the withdrawal of diplomatic and economic relations to boycotting sporting games, nations (usually acting collectively) set out to back their targeted regime into a corner. Coupled with the external pressure of being unable to access vital resources and capital, sanctions are designed to deteriorate living standards and stoke discontent to the point where governments are faced with the choice of kowtowing to international pressure or risk facing civil war.

Nowadays, sanctions are more ubiquitous than ever, despite having a demonstrably mixed track record.

The trade embargo in Cuba has cost the country over $130bn and has been in place for over 60 years. Nevertheless, the communist government has endured, with sanctions doing little more than providing the government with a scapegoat for its tanking economy. Research suggests that sanctions meet their stated objectives only 34 per cent of the time.

On the other hand, many credit such measures with delivering a fatal blow to apartheid in South Africa and nuclear proliferation in Iran. Even if such sanctions aren’t always successful, their utility can be viewed as largely symbolic, allowing nations to turn ideological enemies and human rights abusers into international outcasts, all without firing a single shot.

The ethics of using sanctions

From a consequentialist perspective – which looks to outcomes rather than intentions when it comes to making a moral judgement – the case for sanctions looks rather grim. To be ethically justified in pursuing such measures, those enacting this policy would want to be guaranteed that their actions are helping, not causing unnecessary hurt.

Perhaps a recognition of this principle was the reason why OnlyFans was so quick to backflip on their boycott. If only those pulling vodka from supermarket shelves and Dostoevsky from university reading lists could make this same calculus. These grandstanding gestures are not the kinds of actions that will meaningfully impact the course of war. If anything, they distract from a lack of meaningful action, erstwhile promoting xenophobic discourse.

It is worth noting that Joe Biden was referring to Putin, not his motherland, when he instructed the world to make the aggressor a “pariah on the international stage”. We would do well to remember the distinction between a country’s elite and their citizens (particularly in countries with low levels of democracy, like Russia) before implementing sanctions that treat them as one and the same.

As acknowledged by the United Nations, arguably the biggest international advocate for multilateral sanctions, sanctions often cause disproportionate economic and humanitarian harm to the very people they seek to protect. Additionally, such actions often cause collateral damage to otherwise uninvolved countries. Underscoring these issues is a lack of historical evidence to support the effectiveness of such measures.

Some may work their way around this point by arguing that such measures would shorten the war through crippling the economy, thereby negating some of the fallout for innocent civilians. However, the facts show otherwise – Sanctions stand the best chance of success when they are short, targeted, and implemented against a democratic government.

The measures in place against the kremlin meet none of these criteria, all but guaranteeing a prolonged amount of suffering for innocent civilians. To this end, imposing sanctions could be considered unethical.

Nevertheless, countries often justify their use of sanctions by claiming that they have a humanitarian duty to act against perceived injustice and moral violations. Accordingly, the ethicality of this decision must be judged to a different standard; if an actor is fulfilling their obligations as a member of the international community, then they are acting morally (a theory known as deontology).

This line of reasoning does not hold when it comes to the sanctions placed on Russia. Firstly, these actions replace a perceived injustice with perhaps an even greater one – the unnecessary involvement of innocent civilians in a conflict that is largely beyond their control. Some may justify this by arguing a responsibility to punish wrongdoers irrespective of the consequences, but the fact that all countries in the world are signatory to the principles of jus in bello vis-à-vis the Geneva Convention indicates a more binding duty. Undeniably, Russia has broken this code of conduct many times over, but moral decisions are not conducted on a tit-for-tat basis.

Secondly, they are not principally sound. Russia is one of the world’s largest suppliers of energy, yet curiously, this industry is largely exempt from most sanctions. We are unlikely to see this change significantly until the world moves away from fossil fuels altogether. Moreover, the international community will fail to cripple the kremlin unless it is willing to endure some short-term sacrifice for a greater duty.

Altogether, if those imposing sanctions are attempting to do so morally, they are failing. History has shown us what happens when we attempt to choke a country economically and politically, and it is ugly. We should be suspicious of the idea that sanctions are the only way for us to respond to misbehaving countries.

This is not to excuse citizens from the crimes of their government, but to call into question why the international community is so willing to use a tool that inevitably punishes the innocent, vulnerable, and often powerless (noting that this economic weapon is so often wielded against autocratic regimes).

The facts cannot be ignored; the elites responsible for the unprovoked invasion of Ukraine will continue to dodge sanctions through the likes of anonymous international bank accounts, foreign sympathisers and, increasingly, cryptocurrency. Meanwhile, people like Lina will shoulder the brunt of this burden.

All is fair in love and war – but some things are fairer than others, like avoiding the use of debunked tactics that mess with innocent lives needlessly. Without considering the ethicality of their behaviour, the international community risks causing an entirely avoidable humanitarian crisis which undermines the very principles that they to defend. We must think twice before we applaud those that are quick to sanction lest we cause more injustices to be committed.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Peter Singer on charitable giving

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

Those regular folk are the real sickos: The Bachelor, sex and love

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Vulnerability

Explainer

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights

Ethics Explainer: Liberalism

BY Isabella Vacaflores

Isabella is currently working as a research assistant at the Global Institute for Women’s Leadership. She has previously held research positions at Grattan Institute, Department of Prime Minister & Cabinet and the School of Politics and International Relations at the Australian National University. She has won multiple awards and scholarships, including recently being named the 2023 Australia New Zealand Boston Consulting Group Women’s Scholar, for her efforts to improve gender, racial and socio-economic equality in politics and education.

Ethics Explainer: Power

Ethics Explainer: Power

ExplainerBusiness + LeadershipPolitics + Human RightsRelationships

BY The Ethics Centre 11 MAR 2022

“If a white man wants to lynch me, that’s his problem. If he’s got the power to lynch me, that’s my problem. It’s not a question of attitude; it’s a question of power.” – Stokely Carmichael

A central concern of justice is who has power and how they should be allowed to use it. A central concern of the rest of us is how people with power in fact do use it. Both questions have animated ethicists and activists for hundreds of years, and their insights may help us as we try to create a just society.

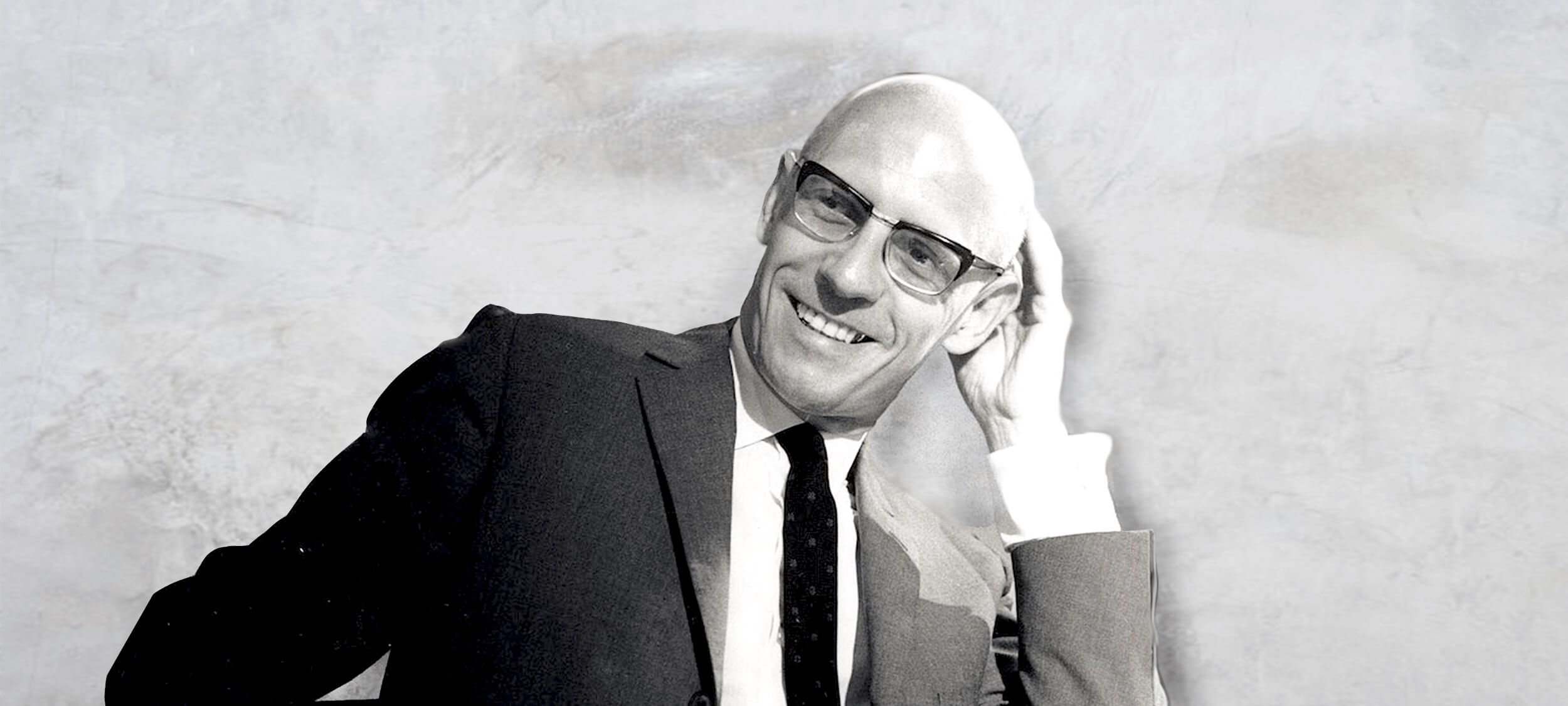

A classic formulation is given by the eminent sociologist Max Weber, for whom power is “the probability that one actor within a social relationship will be in a position to carry out his own will despite resistance”. Michel Foucault, one of the century’s most prominent theorists of power, seems to echo this view: “if we speak of the structures or the mechanisms of power, it is only insofar as we suppose that certain persons exercise power over others”.

A rival view holds that instead of being a relation, power is a resource: like water, food, or money, power is a resource that a particular person or institution can accrue and it can therefore be justly or unjustly distributed. This view has been especially popular among feminist theorists who have used economic models of resource distribution to talk about gendered inequalities in social resources, including and especially power.

Susan Moller Okin is one prominent voice in this tradition:

“When we look seriously at the distribution of such critical social goods as power, self-esteem, opportunities for self-development … we find socially constructed inequalities between them, right down the list”.

What’s the difference between these two views? Why care? One answer is that our efforts to make power more just in society will depend on what kind of thing it is: if it’s a resource, such that problems of unfair power are problems of unequal distribution, we might be able to improve things by removing some power from some people – that way, they would no longer have more than others. This strategy would be less likely to work if power was a relation.

In addition to working out what power is, there are important moral questions about when it can be ethically used. This is a pressing question: As long as we live in societies, under democratic governments, or in states that use police forces and militaries to secure our goals, there will be at least one form of power to which everyone is subject: the power of the state.

The state is one of the only legitimate bearers of the power to use violence. If anyone else uses a weapon or a threat of imprisonment to secure their goals, we think they’re behaving illegitimately, but when the state does these things, we think it is – or can be – legitimate.

Since Plato, democracies have agreed that we need to allow and centralise some coercive power if we are to enforce our laws. Given the state’s unique power to use violence, it’s especially important that that power be just and fair. However, it’s challenging to spell what fair power is inside a democracy or how to design a system that will trend towards exemplifying it.

As Douglas Adams once wrote:

“The major problem with governing people – one of the major problems, for there are many – is that no-one capable of getting themselves elected should on any account be allowed to do the job”.

One recurring question for ‘fairness’ in political power is whether the people governed by the relevant political authority have a to obey that authority. When a state has the power to set laws and enforce them, for instance, does this issue a correlate duty for citizens to obey those laws? The state has duties to its people because it has so much power; but do people have reciprocal duties to their state, also rooted in its power?

Transposing this question into our personal lives, it’s sometimes thought that each of us has a kind of moral power to extract behaviour from others. If you don’t keep your promise, I can blame or sanction you into doing what you said you would. In other words, I can exercise my moral power to make claims of you. Does this sort of power work in the same way as political power? Is it possible for me to abuse my moral power over you; using it in ways that are unjust or unfair – and might you have a duty to obey that moral power?

Finally, we can ask valuable questions about what it is to be powerless. It’s certainly a site of complaint: many of us protest or object when we feel powerless. But how should we best understand it? Is powerlessness about actually being interfered with by others, or simply being susceptible to it, or vulnerable to it? For prominent philosopher Philip Pettit (AC), it’s the latter – to be “unfree” is to be vulnerable or susceptible to the other people’s whims, irrespective of whether they actually use their power against us.

If we want a more ethically ordered society, it’s important to understand how power works – and what goes wrong when it doesn’t.

Join us for the Ethics of Power on Thurs 14 March, 2024 at 6:30pm. Tickets available here.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

He said, she said: Investigating the Christian Porter Case

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Are there limits to forgiveness?

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

Australia’s ethical obligations in Afghanistan

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

The problem with Australian identity

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Survivors are talking, but what’s changing?

Survivors are talking, but what’s changing?

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + LeadershipPolitics + Human Rights

BY Louise Richardson-Self 9 MAR 2022

At the Australia-wide March4Justice rallies in 2021, Brittany Higgins (a former Liberal Party staffer) and Grace Tame (Australian of the Year 2021) delivered speeches in Canberra and Hobart, respectively. Higgins was raped inside Parliament House. Tame is a survivor of child sex abuse. Both called for changes in Australian culture and our institutions to prevent “abuse culture” and to ensure the safety of those most vulnerable to sexual assault.

On Wednesday 9 February 2022, both women gave respective addresses at the National Press Club (NPC) in Canberra. Both criticised that too little had changed since they spoke at these rallies. (Though, the day prior to the addresses, Prime Minister Scott Morrison finally apologised to the survivors of sexual harassment and assault endured by employees in federal parliament.)

In her NPC address, Higgins explained her rationale for making her sexual assault public:

“I made my decision to speak out because the alternative was to be part of the culture of silence inside Parliament House. I spoke out because I wanted the next generation of staffers to work in a better place.”

She then lamented:

“I’m worried what too many people beyond the government and the media took out of the events of last year was that we need to be better at talking about the problem…. I’m not interested in words anymore. I want to see action.”

To clarify, the words Higgins is not interested in anymore are “weasel-words” – she is not advocating against free speech, nor rejecting the need for conversations on the prevalence of sexual abuse.

Tame and Higgins both believe we need institutional changes to address this issue. And if we are to take anything away from the NPC addresses – and we should – it is this: institutional change must be tackled actively – though not all institutions are formal; we must challenge abuse of power – though not all power is formally bestowed; and those who are in formal positions with considerable power must act effectively.

To that end, Tame explicitly identified three necessary steps that must be taken to progress social and institutional change.

- Take sexual violence seriously – this means taking proactive measures to prevent it.

- Provide adequate funding to actually implement the proactive measures we need.

- Create consistent legislative reforms. For example, sexual assault of a child should not be named “maintaining a relationship with a person under the age of 17,” which was the law Tame’s rapist contravened. All such forms of child sexual abuse should be named for what they are. Abuse.

And, according to Higgins’ response during NPC question time, a greater gender balance in Government would help immensely.

–

Tame and Higgins have told Australia exactly what we need to do – so why isn’t Australia making adequate progress? Higgins clearly believes that the LNP Government, and Prime Minister Scott Morrison in particular, could be doing more to prevent such heinous acts. She explains:

“I wanted him to use his power as Prime Minister. I wanted him to wield the weight of his office and drive change in the Party and our Parliament, and out into the country”.

In spite of Morrison’s apology, and even in light of the 28 recommendations for change in parliament workplaces following an independent review headed by the Sex Discrimination Commissioner (AKA the Jenkins’ review), Higgins perceives too little action, reminding us:

“Last year wasn’t a march for acknowledgement and it wasn’t a march for coverage. It wasn’t a march for language. It was a march for justice, and that justice demands real change.”

It is time to hold power to account.

On the matter of power, note its informal use. During her NPC address, Tame revealed that she had received “a threatening phone call from a senior member of a government funded organisation” ‘asking’ her not to say anything negative about the Prime Minister because “you are influential”. But Tame did not have the power in this exchange – the caller did.

Then there is the press, another crucial institution with an immensely powerful role to play in shaping the attitudes of the populace.

But what media seem not to care about, says Tame, is how trauma is often reinforced through powerful institutions like the press.

Since being named Australian of the year in 2021, Tame reports being: “re-victimised, commodified, objectified, sensationalised, delegitimised, gaslit, and thrown under the bus by the mainstream media.”

Strikingly, in spite of Tame’s reprimanding of the press for their re-traumatising actions, the anonymous phone call to Tame became the centre of the mainstream media’s focus of the NPC addresses – with Higgins’ contribution essentially written out of the narrative. Suddenly it was necessary and urgent to find the identity of this mystery caller and for the Prime Minister to assert intent to discover which agency was responsible (and, in so doing, delicately removing himself from the realm of complicity in this abuse of power).

Then, on 14 February, the Daily Mail ran a photo of a teenage Tame seated with what appears to be a ‘bong’ (a device for smoking marijuana). One can only presume that the decision to publicise this photo, which implicates Tame in undertaking illegal behaviour, would have the effect of tarnishing her public image. Media are supposed to report neutrally, not run smear campaigns.

On 19 February, Tame responded publicly via Twitter to all media who published “that” photo, stating:

“At every point — on the national stage, I might add — I’ve been completely transparent about all the demons I’ve battled in the aftermath of child sexual abuse; drug addiction, self-harm, anorexia and PTSD, among others. You just clearly haven’t been listening.”

She then goes on to chastise the media:

“By point-mocking a symptom of a bigger picture, you’ve reinforced the imbalance of an already skewed culture. You’ve chosen to punish the product of an evil, not the evil itself. This is precisely why survivors don’t report. Congratulations.”

Inertia and smear campaigns are just two of the ways institutions can perpetuate abuse culture, also known as ‘rape culture’.

Philosopher Claudia Card has argued that ‘rape’ (here, meaning any and all sexual assault) is a terrorist institution. Sexual violence – a social practice – is gendered. We live in a world of “social norms that create and define a distribution of power among and between members of the sexes”. This is a type of social identity power – a power that is informally maintained through our actions and our assumptions about the way the world necessarily is. Women fear what men can do to them. Terror of this kind is manipulative. And terror is a shortcut to power.

Rape is also an institution (in an informal sense) insofar as it is “a form of social activity structured by rules that define roles and positions, powers and opportunities.” Cisgender men are usually the perpetrators of sexual assault, and women and children (including male children) are usually the targets of that assault. “For the most part,” says Card, “the rules become ‘second nature’, like the rules of grammar, and those guided need not be aware of the rules as learned norms”.

While I want to emphasise that not all – nor even most – cisgender men commit sexual assaults, that cisgender men can be victims of sexual assault, and typical targets (women and children) can be perpetrators, the constancy of this type of activity – in 2018–19, the majority of sexual assault offenders recorded by police were male (97%) – leads to the impression that sexual assault (tacitly: of women and children) is inevitable.

Since there is a social practice – an open secret – of women and children being sexually abused, women become socialised to fear sexual abuse. Women live in a state of apprehension, always on alert for signals of danger. Cisgender men (who have not experienced assault) do not have to live this way.

Thus, if ‘rape’ really is an informal terrorist institution in Australia, it would follow that one of the reasons Australia is yet to meet Tame’s first requirement – to take sexual violence seriously and to take proactive measures to prevent it – is because we have not yet disregarded the assumption that sexual abuse is inevitable. People may be working on changing such tacit assumptions, but on a mass scale we are yet to shift the dial.

This leads us to Tame’s second ask: adequate funding. Help the people who are doing the re-educating, who are running shelters, who need to access specialist legal services, who are training medical professionals in sexual assault cases, increasing access to psychologists, and improving the child welfare system. The list goes on. And, in Higgins’ view, if there were more women in Parliament, this issue would be taken more seriously – even though “quotas” is a “dirty word” to the Liberal Party, she revealed in question time.

Finally, we reach Tame’s third driver of change, to which her foundation has been working: creating consistent legislative reforms wherein, for instance, there is no reference to a sexual “relationship” between an adult and a child. However, one foundation can only achieve so much – we need a more proactive approach.

–

Higgins and Tame both identified the barriers to overcoming trauma, while making suggestions on overcoming the abuse culture that has been absorbed into some of our most powerful institutions. Thus, institutions are not off the hook. They have their role to play in dispelling both rape culture and challenging the presumed inevitability of sexual abuse.

Given this, why did the media sensationalise Tame’s anonymous caller, why was Tame smeared, and why was Higgins cast out of the media spotlight? Why is the Government dragging its feet on reform? Why do people keep spreading “that” photo on social media?

One problem, it seems, is this: while Higgins and Tame were indeed given a platform from which to speak, what they said was not really ‘heard’ (that is, properly understood) by the media, by politicians, and even by the public. When one is not heard properly, one is effectively silent. Silence is exactly what Higgins was trying to escape. And yet, it seems that what is said too often makes little difference.

Being ‘effectively silenced’ does not necessarily mean that someone literally cannot speak, or that they have no platform. It means that when they speak, they are misunderstood (often wilfully). The message that should be taken from their words is not the message that media, politicians, and even the general public actually hear.

The media have acted as though that one singular instance of intimidation was the most important issue raised that day. But the point Tame was making is that there is no need to name the person nor agency because this sort of silencing tactic happens all the time to people trying to change the status quo. One must ask, are the media and LNP, even the public, purposefully missing the forest for the trees?

To fail to heed the wisdom of these women, as spokespeople for survivors, is an absolute ethical failing. They are gifting us with their situated knowledge and experience-based insights that would lead to successful reform, as well as the many insights that have been shared with them by other survivors who have sought them as confidantes. Tame literally lists what needs to happen: one, two, three. But it is clear that the press and the Parliament have not yet learnt how to actually listen to the intended overarching messages of these women – and, until they (and we ourselves) do, nothing will change.

We must pay attention and be proactive in destroying the terrorist institution of abuse culture.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Health + Wellbeing

Tips on how to find meaningful work

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

Big Brother is coming to a school near you

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

We are the Voice

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Do organisations and employees have to value the same things?

BY Louise Richardson-Self

Louise Richardson-Self is a Lecturer in Philosophy and Gender Studies at the University of Tasmania and an Australian Research Council Discovery Early Career Researcher Awardee (2019). Her current research focuses are the problem online hate speech, and the tension between LGBT+ non-discrimination and religious freedom. She is the author of Justifying Same-Sex Marriage: A Philosophical Investigation (2015) and her second book, Hate Speech Against Women Online: Concepts and Countermeasures is due for publication in 2021.

Is it wrong to care about Ukraine more than other wars?

Is it wrong to care about Ukraine more than other wars?

Opinion + AnalysisPolitics + Human RightsRelationships

BY Dr Tim Dean 3 MAR 2022

The invasion of Ukraine by Russian forces in the early hours of 24 February 2022 came as a violent shock to most onlookers.

Even after the visible buildup of Russian forces and weeks of sabre rattling by Russian President Vladimir Putin, the images of rockets striking apartment blocks and tanks rolling through city streets triggered an outpouring of support for Ukraine from people within Australia and around the world.

But those who dwell on social media might have seen some voices express a different perspective: that the focus on Ukraine is suggestive of a darker underlying bias on behalf of the onlookers; that the conflict has only gained so much attention because the victims of the war are white Europeans.

The argument suggests that if the victims were non-white, such as those involved in the ongoing wars in Yemen, Syria or Ethiopia, then the media and Western onlookers would be far less engaged.

So is it wrong to focus our attention acutely on the war in Ukraine while investing less energy on conflicts in other parts of the world, especially if those conflicts affect non-white people? Is it OK to care more about a war in Europe than it is a war in Africa or the Middle East?

We can unpack the argument in a few different ways. The least charitable interpretation is that it’s an accusation of racism, suggesting that people who care about the war in Ukraine only care because the victims are white. That might be true for some onlookers, but it’s highly doubtful that this applies to the majority of people.

Rather, there are many reasons why someone in Australia might place great significance on the events unfolding in Ukraine. First of all is the shock factor, particularly given the relative stability and lack of open wars between nations in Europe since the end of the Second World War. This means the war in Ukraine is not just a concern for that region but is of tremendous global significance, with the potential to reshape the geopolitical landscape in a way that could affect people around the world. In this way, the war in Ukraine very much qualifies as being worthy of our attention due to its historical significance.

There’s also the matter of familiarity, in the sense that Ukraine is a modern, industrialised and democratic nation that shares many political and moral values with countries like Australia. Beyond the human toll, the invasion represents an attack against values that most Australians cherish.

Many Australians also have friends, family or coworkers with connections to Ukraine or other European countries who are impacted by the war. To them, the war is not just news of distant events but is felt in their immediate circles in a way that other conflicts might not be. Of course, there are many Austrlians who are also affected by conflicts in other parts of the world, such as in Syria and Yemen.

Finally, on a more mundane level, the war in Ukraine is likely to have a material impact on our lives through its destabilisation of the international economy, as well as on commodity prices such as wheat and oil, in a way that most other ongoing conflicts don’t.

All this said, while the above can help explain why someone might take a more acute interest in the war in Ukraine, it doesn’t answer the ethical question of whether they should take greater interest in conflicts elsewhere at the same time. It’s possible that these explanations don’t justify an undue focus on one population experiencing conflict rather than another.

A more charitable interpretation of the argument is that all suffering deserves our attention, all violence deserves our rebuke and all people involved in wars deserve our empathy. This stems from a universalist ethic, such as that promoted by philosophers like Peter Singer. It argues that all people deserve equal concern, no matter their background, ethnicity or nationality. Singer famously argued that if you’d dive into a pond to save a drowning child, even at the cost of muddying your clothes and being late to work, then you ought to be willing to incur a similar cost to save the life of a dying child on the other side of the world.

From this perspective, the same reasons that justify our empathy towards the suffering of the Ukrainian people should similarly apply to the people of Yemen, Ethiopia, Syria and elsewhere.

However, a truly universalist ethic is difficult, if not impossible, to fully achieve in practice. Few people would be willing to take the ethic to the extreme, and treat strangers in distant countries with as much care and concern that they reserve for our family. If this is so, then it is difficult to know where to draw the line around who deserves more or less of our concern.

Furthermore, everybody has a finite budget of time, emotional energy and power to act. It is not possible to be engaged with every conflict, every injustice and every instance of ethical wrongdoing taking place in the world, let alone to be able to act on them. It might be reasonable for people to choose where to invest their limited energy, or to preserve their energy for causes they can positively impact. That doesn’t mean they don’t care about other issues, only that they’ve chosen to do good where they can.

Which brings us to the most charitable interpretation of the argument, which is that any conflict should remind us of the horrors of war, and should motivate us to extend our empathy to people who are suffering anywhere in the world. The saturation media footage of violence and destruction in Ukraine can help us better understand the plight of people living through other conflicts. The plight of embattled civilians in Kyiv can help us better understand and empathise with people living in Aleppo in Syria or Sanaa in Yemen.

It is unlikely that those promoting this argument on social media would want people to retreat from engaging with all news of conflict or suffering, whether it is in Europe or elsewhere. Rather, we might forgive people for having some bias in where they choose to direct their attention, while reminding them that all people are deserving of ethical consideration. Moral consideration need not be a zero-sum game; elevating our concern for one population doesn’t have to come at the expense of concern for others.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

Learning risk management from Harambe

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Science + Technology, Society + Culture

5 things we learnt from The Festival of Dangerous Ideas 2022

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Beyond consent: The ambiguity surrounding sex

Big thinker

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Big Thinker: Michel Foucault

BY Dr Tim Dean

Dr Tim Dean is Philosopher in Residence at The Ethics Centre and author of How We Became Human: And Why We Need to Change.

Ukraine hacktivism

Ukraine hacktivism

Opinion + AnalysisPolitics + Human RightsScience + Technology

BY Simon Longstaff 2 MAR 2022

As reported by David Crowe in the Sydney Morning Herald, Ukraine’s Foreign Minister, Dmytro Kuleba, has recently called on individuals, from other countries, to join the fight against Russia’s invasion.

“Foreigners willing to defend Ukraine and world order as part of the International Legion of Territorial Defence of Ukraine, I invite you to contact foreign diplomatic missions of Ukraine”, he said on Sunday night.

It is important to note that it is illegal for Australians to take up this call. As things stand, Australians commit a criminal office if they fight for any formation other than properly constituted national armed forces. This prohibition was introduced to deter and punish Australians hoping to fight in the ranks of ISIS. However, it applies far more generally. As such, it proscribes an age-old practice of individuals engaging in warfare in support of causes they wish to champion. Unlike mercenaries (who will fight for whichever side will pay them the better price), there have been people, throughout history, willing to risk their lives and limbs for idealistic reasons.

More recent examples include those who joined the International Brigade to fight Fascist forces in Spain during the early part of the Twentieth Century, those who joined the Kurds to oppose ISIS, in recent years, and also those who fought with and for ISIS in order to establish a Caliphate in the Middle East.

It should be noted that the choices mentioned above are not morally equivalent – even though the underlying motivation is, essentially, the same. Those who opposed Fascism in the 1930s did not employ terrorism as a principal tactic. ISIS did – unrestrained by any of the ethical limitations arising out of the Just war tradition.

That tradition was developed to deal with forms of war which took place in real time and across real battlespaces where combatants and non-combatants could be killed by a direct encounter with a lethal weapon or its effects.

In recent days, this discussion has taken on a new character as volunteer ‘hacktivists’ have taken up virtual arms, on Ukraine’s behalf, in a cyber-war against Russian forces. Once again, there are non-Ukrainian nationals engaged in a conflict that pits them against an aggressor – not for financial reward, not for reasons of self-preservation but simply because they feel compelled to defend an ideal. Of course, there are bound to be some amongst their ranks who are just in it for the mischief. However, I think most will be sincere in their conviction that they are doing some good.

That said, there is some truth to the old adage that ‘the road to hell is paved with good intentions’. It is not enough to be realising a noble purpose. One also needs to employ legitimate means. It is this thought that lies behind the observation, by Canadian philosopher Michael Ignatieff, that the difference between a ‘warrior’ and a ‘barbarian’ lies in ethical restraint.

In an ideal world, those who belong to the profession of arms are trained to apply ethical restraint in their use of force. The allegations levelled against a few members of the SAS, in Afghanistan, indicate that there can be a gap between the ideal and the actual. However, in the vast majority of cases, Australia’s professional shoulders serve as ‘warriors’ rather than ‘barbarians’.

But what of the ethical restraint required of volunteer cyber-warriors? There are some general observations, as outlined by Dr Matt Beard and I in our publication Ethical By Design: Principles for Good Technology. Our first principle is that ‘CAN does NOT imply OUGHT’. That is, the mere fact that you can do something does not mean that you should!. However, I think that some of the traditional ethical restraints derived from ‘just war theory’ should also apply.

There are three principles of particular importance. First, you need to be satisfied that you are pursuing a just cause. Self-defence and the defence of others who have been attacked without just cause have always been allowed – with one proviso … your own use of force must be directed at securing a peace that is superior to that which would have prevailed if no force had been used.

That accounts for the ends that one might pursue. When it comes to the means, they need to accord with the principles of ‘discrimination’ and proportionality’. The first says that you may only attack a legitimate target (a combatant, military infrastructure, etc.). The second requires you only to use the minimal amount of force needed to achieve one’s legitimate ends.

President Putin’s forces have violated all three principles of just war. He has invaded another nation without just cause. He is targeting non-combatants (innocent women and children) and he is employing weaponry (and threatening an escalation) that is entirely disproportionate.

The fact that he does so does not justify others to do the same.

Volunteer cyber-warriors have to be extremely careful that in their zeal to harm Putin and his armed forces, they do not deliberately (or even inadvertently) harm innocent Russians who have been sucked into one man’s war.

Of course, this means fighting with the equivalent of ‘one arm tied behind the back’. The temptation is to fight ‘fire with fire’ – but that only leads to the loss of one of one’s ‘moral authority’. The hard lessons of history have taught us that this is a potent weapon in itself.

The law might not prevent a cyber-warrior from fighting on the side of Ukraine from a desk somewhere in Australia. However, one should at least pause to consider the ethical dimension of what you propose to do and how you propose to go about it.

There can be honour in being a cyber-warrior. There is none in being a cyber-barbarian.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

What’s the use in trying?

Opinion + Analysis

Climate + Environment, Politics + Human Rights, Relationships, Society + Culture

The youth are rising. Will we listen?

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

Unrealistic: The ethics of Trump’s foreign policy

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Want #MeToo to serve justice? Use it responsibly.

BY Simon Longstaff

Simon Longstaff began his working life on Groote Eylandt in the Northern Territory of Australia. He is proud of his kinship ties to the Anindilyakwa people. After a period studying law in Sydney and teaching in Tasmania, he pursued postgraduate studies as a Member of Magdalene College, Cambridge. In 1991, Simon commenced his work as the first Executive Director of The Ethics Centre. In 2013, he was made an officer of the Order of Australia (AO) for “distinguished service to the community through the promotion of ethical standards in governance and business, to improving corporate responsibility, and to philosophy.” Simon is an Adjunct Professor of the Australian Graduate School of Management at UNSW, a Fellow of CPA Australia, the Royal Society of NSW and the Australian Risk Policy Institute.

Why we should be teaching our kids to protest

Why we should be teaching our kids to protest

Opinion + AnalysisPolitics + Human RightsRelationships

BY Dr Luke Zaphir 3 FEB 2022

When the Prime Minister says classrooms shouldn’t be political and students should stay in school, that’s an implicit argument about what kinds of citizen he thinks we should have.

It’s not unreasonable. The type of citizen who has not gone out to protest will have certain habits and dispositions that are desirable. Hard-working, diligent, focused. However, the question about what it means to be a citizen and how to become one is complicated and not one that any one person has the truth about.

Let’s go back to basics though. What’s the point of education? It’s to prepare children for life. Many would claim it’s to get children ready for work, but if that was the case we would put them in training facilities rather than schools. Our education systems have many tasks – to make children work ready to be sure, but also to develop their personhood, to allow them to engage in society, to help them flourish. Every part of the curriculum, from its General Capabilities of critical and creative thinking to the discipline specific like technologies, is designed to provide young people with the skills, knowledge and dispositions necessary for being 21st century citizens.

What many don’t realise is that learning what it means to be a citizen isn’t localised to the curriculum. Interactions with parents, teachers, with each other, with news and social media – all of these contribute to the definition of a citizen.

Every time a politician says that children should be seen and not heard, that’s an indication of the type of citizen they want.

Most politicians don’t want kids out protesting after all – not only is it disruptive to whatever is in school that day, it looks really bad on the news for them. Protests are bad news for politicians in general and if children are involved, there’s no good way to spin it.

But we do want children to learn how to protest. We want them to be able to see corruption and have discussions and heated debates and embrace complexity. Everyone should have the ability to say their piece and be heard in a democracy. This is something that we’ve already recognised as persuasion is a major part of education and has been for years.

However, when we talk about this, we need to recognise that we aren’t just talking about skills or knowledge. This isn’t putting together a pithy response or clever tweet. It’s about being capable of contributing to public discourse, and for that, we need children to hold certain intellectual virtues and values.

An intellectual virtue refers to the way we approach inquiry. An intellectually virtuous citizen is someone who approaches problems and perspectives with open-mindedness, curiosity, honesty and resilience; they wish to know more about it and are truth seeking, unafraid of what terrors lie in it.

If virtues are about the willingness to engage in inquiry, intellectual values are the cognitive tools needed to do so effectively. It’s essential in conversation to be able to speak with coherence; an argument that doesn’t meaningfully connect ideas is one that is confusing at best, and manipulative at worst. If we’re not able to share our thoughts and display them clearly, we’re just shouting at each other.

Values and virtues are difficult to teach though. You can’t hold up flash cards and point to “fallibility” and say “okay, now remember that you can always be wrong”. We have cognitive biases that stand between us and accepting a virtue like “resilience to our own fallibility” – it feels bad to be wrong. The way we learn these habits of mind is through practice, through acceptance and agreement. Teachers, parents and adults can all develop these habits explicitly through classroom activities, and implicitly by modelling these behaviours themselves.

If a student can share their ideas without fear of being shut down by authority, they’ll develop greater clarity and coherence. They’ll be more open-minded about the ideas of others knowing they don’t have to defensively guard their beliefs.

To the original question of what it means to be a good citizen in a global context: we want our children to develop into conscientious adults. A good citizen is able to communicate their ideas and perspectives, and listen to the same from others. A good citizen can discern policy from platitude, and dilemmas from demagoguery.

But it takes practice and time. It takes new challenges and new contexts and new ideas to train these habits. We don’t have to teach students the logistics of organising a revolution or how to get elected.

And if we’re not teaching them when or why they should protest, we’re not teaching them to be good citizens at all.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

The Bear and what it means to keep going when you lose it all

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Science + Technology

The complex ethics of online memes

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture, Politics + Human Rights

Pleasure without justice: Why we need to reimagine the good life

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships

Beyond the headlines of the Westpac breaches

BY Dr Luke Zaphir

Luke is a researcher for the University of Queensland's Critical Thinking Project. He completed a PhD in philosophy in 2017, writing about non-electoral alternatives to democracy. Democracy without elections is a difficult goal to achieve though, requiring a much greater level of education from citizens and more deliberate forms of engagement. Thus he's also a practicing high school teacher in Queensland, where he teaches critical thinking and philosophy.

Is the right to die about rights or consequences?

Is the right to die about rights or consequences?

Opinion + AnalysisPolitics + Human Rights

BY Joshua Pearl 31 JAN 2022

Of all public policy debates, voluntary assisted dying is an ethical debate as much as any other, made clear by the recent impassioned speeches on the floor of the New South Wales parliament and the accompanying public debate.

The various arguments for and against voluntary assisted dying are motivated by a range of different reasons. For some it’s by personal experiences and time spent with dying loved ones. For others it’s by views on human dignity – reasons that are used both for and against. Many arguments are motivated instead by a deep belief in the existence of God, and what this means for how we treat others.

While there may be no “best way” to consider and assess the case for and against voluntary-assisted-dying, it seems to me that a useful approach is to focus on two central ethical issues:

- The level of rights an individual has over their body

- Whether legalised voluntary assisted dying makes a society worse-off due to the negative consequences that may ensue, such as increased self-harm in the broader population or individuals being pressured to prematurely end their lives.

The rights case for voluntary assisted dying largely centres on an individual’s self-ownership rights – what they are permitted to do with their bodies. These rights do not rest on any consequential benefits that might arise, such as a more cohesive society or a happier public, but are natural rights, without further need of justification.

If people have self-ownership rights in a strong sense – for example, they can do as they please with their bodies, free from any external government interference – then it seems the proposed NSW voluntary assisted dying bill does not go far enough.

Patients must have a condition that is advanced, progressive and will cause death within six months (or 12 months for a neurodegenerative disease). This timeframe appears unfair because it means patients with higher levels of pain who are further from the relief of death will suffer more, for longer. If anything, a person experiencing a higher level of pain has a greater need for voluntary assisted dying. If we regard incurable psychological suffering as an affliction comparable with physical suffering (a possibility it seems we do take seriously as a society), failing to provide relief for this cohort seems if not unfair, then at least inconsistent.

However, our existing social norms suggest self-ownership rights are not inviolable. We are not allowed to sell our organs, even if to save another person’s life (we can donate them). We are not allowed to sell ourselves into slavery, even if this could raise vital funds our families or children need to lead better lives.

When we impose risks that are great enough, either to ourselves or others, we are restricted from doing things as menial as leaving home after dark, as was the case in parts of south-west Sydney during the COVID-19 lockdowns. Sometimes these restrictions are publicly justified on the basis of being good for the individual (paternalistic reasons), and other times on the basis of being good for society (what economists might call “externality” reasons).

With regard to consequences, from an individual’s perspective, it seems reasonable to suggest that a condition can be so severe, so acute, that life is not worth living. Our existing medical practices align with this view. It is permissible in NSW for doctors to withdraw life-saving treatment at the request of patients and doctors are under no obligation to provide medical treatment when treatment is considered futile. While there is a difference between killing and letting die, this practice suggests it is possible for the benefits of death to outweigh the costs of life.

Therefore, from a consequentialist perspective, it seems to me the primary issue of concern is whether voluntary assisted dying makes society worse. One argument made is that voluntary assisted dying can increase suicides in the general population and pressure vulnerable people to prematurely end their lives. It seems reasonable to accept this is possible and reasonable to accept that we cannot know with full certainty how legalising voluntary assisted dying will impact NSW.

The primary issue of concern is whether voluntary assisted dying makes society worse.

However, these consequential considerations can be informed by looking at the experience of other jurisdictions. Voluntary assisted dying has been legal in the US states of Oregon, Washington and Vermont since 1997, 2009, and 2013 respectively; legal in the Netherlands and Belgium since 2002; and legal in Switzerland since 1918.

Given both sides of the debate argue the evidence is in favour of their own argument, a useful exercise is for the government to commission an independent non-partisan group of experts to analyse the existing data and academic literature, and publicly report back. This would help inform members of NSW Legislative Council when they consider amendments and vote on voluntary-assisted-dying legislation in 2022.

The non-partisan group would analyse how laws have been introduced in other jurisdictions and how these laws have changed over time. The group would ideally look for evidence of whether voluntary assisted dying has increased general population suicides or self-harm, or pressured individuals to prematurely end their lives. They might even consider whether voluntary assisted dying legalisation has numbed or lessened the community spirit, or negatively (or positively) changed the way a community treats and thinks about death.

An independent non-partisan report would provide a greater understanding of the trade-off between individual rights and social consequences. Should it be the case there is near zero risk of negative social consequences, then the case for voluntary assisted dying would seem unassailable. But if there is a risk of increased general population self-harm (for example), the decision then centres on a threshold issue of what level of risk and what level of social impact we are willing to accept.

We might be willing to accept one additional event of self-harm or we might be willing to accept one hundred. We might even be willing to accept that an individual’s rights over their bodies are so strong that patients in agonising pain have a right to voluntary assisted dying, regardless of the social consequences that might result. That is, we might conclude that individual rights trump social consequences.

Should the voluntary assisted dying bill become law, the NSW experience may differ from other jurisdictions due to a range of policy or cultural reasons, which is why it seems an oversight the proposed bill does not require more in the way of future data collection and future reviews (something that could be undertaken by the proposed Voluntary Assisted Dying Board). This amendment would aid future debates (should the bill be passed by the NSW Legislative Council) on whether voluntary assisted dying should be expanded, amended, or even repealed.

It seems to me, the proposed voluntary assisted dying bill permits too little where rights are concerned by setting too strict a timeframe on nearness to death, and permits too much where consequences are concerned by not adequately taking into account the potential for negative social consequences.

The proposed bill and the ethical debate would be improved by considering ways to treat individuals consistently and fairly, by the government commissioning an independent non-partisan group to publicly report back before the NSW Legislative Council votes on the voluntary assisted dying bill, and by amending the proposed bill to require greater data collection and mandate future reviews.

These measures would enhance our understanding of individual rights and social consequences and enable our politicians to vote with their conscience alongside the relevant facts.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Big thinker

Politics + Human Rights, Society + Culture

Big Thinker: Audre Lorde

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Why victims remain silent and then find their voice

Opinion + Analysis

Climate + Environment, Politics + Human Rights

Is it time to curb immigration in Australia?

Opinion + Analysis

Climate + Environment, Politics + Human Rights

Are we prepared for climate change and the next migrant crisis?

BY Joshua Pearl

Joshua Pearl is the head of Energy Transition at Iberdrola Australia. Josh has previously worked in government and political and corporate advisory. Josh studied economics and finance at the University of New South Wales and philosophy and economics at the London School of Economics.

Of what does the machine dream? The Wire and collectivism

Of what does the machine dream? The Wire and collectivism

Opinion + AnalysisPolitics + Human RightsRelationshipsSociety + Culture

BY Joseph Earp 10 DEC 2021

This week, a group of more than a dozen Rohingya refugees launched a civil suit against Facebook, alleging that the social media giant was responsible for spreading hate speech.

The victims of an ongoing military crackdown in Myanmar, the refugees claimed not merely that Facebook allowed users to express their anti-Rohingya views, but that Facebook radicalised users – that, in essence, the platform changed beliefs, rather than merely providing a conduit to express them.

The suit is, in many ways, the first of a kind. It targets the manner in which systems – whether they be social media giants, video streaming sites like YouTube, or the myriad of bureaucracies that we all engage with in one way or another almost every day – warp and change beliefs.

But what if the suit underestimates the power of these systems? What if it’s not merely that social and financial enterprises alter beliefs, but that these enterprises have belief sets entirely of their own? More and more, as capitalism continues to ratify itself, we are finding ourselves swept up in communities that operate on the basis of desires that are distinct from the views of any one member of those communities. We are all part of a great, groaning machinery – and it doesn’t want what we want.

Pawns in a Game

There is a key sequence in David Simon’s critically adored television series The Wire that sums up this perspective perfectly. In it, three young men, all of them members of a rickety enterprise of crime, find themselves playing chess. The least experienced man does not understand the game – how, he wants to know, does he get to become the king? He doesn’t, the most experienced man explains. Everyone is who they are.

Still, the younger man wants to know, what about the pawns? Surely when they reach the other side of the board, and get swapped out for queens, they have made it – they have beat the system. No, the experienced man explains. “The pawns get capped quick,” he says, simply.

There is a deep, sad irony to the scene: the three men are all pawns. They have no way of beating the system. They will not even live to become queens. When one of them dies a few episodes later, shot to death by his friend, there is a grim finality to the murder. He did, as expected, get capped quick.

This is the focus of The Wire – the observation that members of any community are expendable when weighed against the desires of that community. The game of chess is bigger than any of the pawns could imagine, a system with its own rules that they are merely contingent parts of. And so it goes with the business of crime.

Not only crime, either. The genius of The Wire is the way that it draws parallels between those who operate outside the law, and those who uphold it. The cops who spend the series cracking down on the drug trade are also pawns, in their way: lowly members of a system that they are utterly unable to change. No matter what side of the law that you fall on, you will find yourself submerged in bureaucracy, The Wire says – in the machinations of a vast system of power relations with a goal to constantly perpetuate itself, at your expense.

These are the systems that Sigmund Freud wrote of in his seminal work, Civilization and Its Discontents. For Freud, there is an essential disconnect between the desires of individuals and the desires of the social communities that they unwillingly become a part of. There are things at foot that are bigger than any of us.

Bureaucracies are not the sum total of the desires and beliefs of the members of those bureaucracies. These systems have a life – a value set – entirely of their own.

The Game Never Changes

If that is the case, then how does change occur? The Wire offers only dispiriting answers. The show’s idealists – renegade cop Jimmy McNulty, rogue crime boss Omar Little – either find themselves subsumed by the system that lords over them or eliminated. There is a hopelessness to their rebellion. They uselessly throw themselves into the path of a giant piece of machinery, hoping that their mangled bodies slow the inevitable march of progress.

It doesn’t work. Those who thrive are those who give themselves over entirely to the system, who align their values perfectly with the values of their community and embrace their own insignificance. Snoop, the show’s most hideous and intimidating villain, is a happy pawn, one who has never once considered changing the rules of the game that will send her too into an early, dismal grave.

But what if we all stop playing? That is the solution that The Wire never considers. If these systems, whether they be criminal or judicial, are to be changed, then it requires a different kind of collectivism. We are all part of many communities, not just one. If we remember this – if we understand that we have the power and solidarity that comes from being a member of a particular class, a particular race, a particular gender – then we can fight collective power with collective power. The solution isn’t to get the pawn to the other side of the board. It’s to tip the board over.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

It’s easy to ignore the people we can’t see

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Ethics in a time of coronavirus

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Society + Culture

Four causes of ethical failure, and how to correct them

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships

Treating citizens as customers is a recipe for distrust

BY Joseph Earp

Joseph Earp is a poet, journalist and philosophy student. He is currently undertaking his PhD at the University of Sydney, studying the work of David Hume.

Did Australia’s lockdown leave certain parts of the population vulnerable?

Did Australia’s lockdown leave certain parts of the population vulnerable?

Opinion + AnalysisPolitics + Human Rights

BY Mehhma Malhi 3 DEC 2021

The pandemic has increased the duty we have to other members of our communities.

Different groups of people have different interests, but balancing these interests can cause conflict and friction.

Given Australia’s hard lockdown stance, many people could not wait to lift the restrictions and return to their daily routines. However, in relieving people from these restrictions, we also leave vulnerable populations exposed.

Who do we have a more significant duty towards?

There were discussions around school kids and their right to access education, conversations about teen and adult mental health, and calls to vaccinate the elderly. However, a group that was affected by all these considerations and needed further contemplation was ignored – those with disabilities.

While we are interested in protecting all people, if we do not ensure the safety of the most vulnerable in a population, we fail – we blatantly show that we do not value their needs in conjunction with evaluating a safe society.

The Ethics Centre’s Dr. Simon Longstaff stated recently on Q&A that ‘it is unforgivable that we have to have this conversation … where the most vulnerable members of our community have been left exposed. We should not … expect those people with … vulnerabilities to bear the burden of what we would prefer to do.’

While mental health costs of lockdowns are in favour of opening, Dr. Longstaff warned that ‘we as a society are going to have to accept that those who become infected and die will be something we have to wear on our own conscience.’

Phase 1A of Australia’s vaccine rollout, was initiated in February with the intention of targeting essential healthcare workers and those most vulnerable, such as the elderly and those with disabilities. However, in June only 1 in 5 people with a disability had been vaccinated, and less than 50% of support workers had received both doses of a vaccine. Yet, there was a dramatic increase in October to 70% of individuals being vaccinated.

The marked uptake was likely due to lockdown measures being lifted, as many people wanted the vaccine but could not receive it due to lack of accessibility.

In order to receive a vaccination, people had to contact their GP or later on could book one online.

On the face of it, these distribution procedures seem reasonable but there were significant problems that severely limited access. Having to make a GP appointment simply to obtain a vaccination referral was an unnecessary step that made it particularly difficult for those with disabilities, many of whom are dependent upon others to assist them.

Further, despite being a part of Phase 1A, many people with a disability could not receive the vaccine until lockdown had been lifted and support networks were reinstated. There was no follow-up, reassurance, or support to ensure that those who wanted to receive the vaccine could promptly do so. Therefore, as vaccine distribution moved from one phase to the next, it left an increasing number of those with disabilities behind.

Secondly, for similar reasons, internet access is more difficult for many of those with disabilities and the Department of Health website was not particularly user-friendly. It did not include larger, more legible text or have text to speech which would have helped those with limited sight or those who have trouble reading. Additionally, the high demand for vaccination meant that timeslots were severely limited and if they were available, they were usually inconvenient.

This was especially problematic for those with disabilities because it was not always clear which facilities were equipped with accessible features. To obtain informed consent, centres would need to have staff who are able to understand sign-language and provide information leaflets in braille. Much of this burden of providing additional support and care fell on already stretched family members and carers who, because of lockdown, may already have been working from home and home-schooling children.

What should Australia have done?

First and foremost, the relevant authorities should have ensured that almost 90%+ of each phase was vaccinated before moving to the next phase. In doing so, they would have needed to provide adequate support for those in Phase 1A and set up additional measures as required.

- Vaccine facilities should have been situated close to care facilities.

- Carers and parents should have been able to book their vaccines with individuals.

- Vaccine facilities ought to have implemented “safe” times or locations whereby those with disabilities could show up with no appointment.

What is perhaps irreconcilable is that while these requests/services were prepared during the pandemic, they were simply unavailable due to lack of federal organisation. There are many hospitals around Australia that have rehabilitation medical departments, all of which have specialised members and facilities. Despite notifying the government that they have experience and the equipment to convert into vaccination sites for those living with disabilities, they were not used.

The distribution of the vaccine in Australia was not organised in a manner that was empathetic to individuals living with a disability. I agree with the Royal Commission and Dr Longstaff that ending lockdown and opening without first ensuring high vaccination rates in this vulnerable community was unconscionable and unforgivable.

The lockdown was organised in a manner that did not respect the needs of particular populations. It once again highlights the inequity that people with disabilities face and places the responsibility of any harm to these individuals squarely on society. It was our duty to protect one another from harm during the pandemic, and we have failed a significant group within Australia’s population.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Politics + Human Rights

Constructing an ethical healthcare system

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

Why Anzac Day’s soft power is so important to social cohesion

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

The ethical price of political solidarity

Big thinker

Health + Wellbeing, Politics + Human Rights

Big Thinkers: Thomas Beauchamp & James Childress

BY Mehhma Malhi

Mehhma recently graduated from NYU having majored in Philosophy and minoring in Politics, Bioethics, and Art. She is now continuing her study at Columbia University and pursuing a Masters of Science in Bioethics. She is interested in refocusing the news to discuss why and how people form their personal opinions.

Ethics Explainer: Autonomy

Ethics Explainer: Autonomy

ExplainerPolitics + Human RightsRelationships

BY The Ethics Centre 22 NOV 2021

Autonomy is the capacity to form beliefs and desires that are authentic and in our best interests, and then act on them.

What is it that makes a person autonomous? Intuitively, it feels like a person with a gun held to their head is likely to have less autonomy than a person enjoying a meandering walk, peacefully making a choice between the coastal track or the inland trail. But what exactly are the conditions which determine someone’s autonomy?

Is autonomy just a measure of how free a person is to make choices? How might a person’s upbringing influence their autonomy, and their subsequent capacity to act freely? Exploring the concept of autonomy can help us better understand the decisions people make, especially those we might disagree with.

The definition debate

Autonomy, broadly speaking, refers to a person’s capacity to adequately self-govern their beliefs and actions. All people are in some way influenced by powers outside of themselves, through laws, their upbringing, and other influences. Philosophers aim to distinguish the degree to which various conditions impact our understanding of someone’s autonomy.

There remain many competing theories of autonomy.

These debates are relevant to a whole host of important social concerns that hinge on someone’s independent decision-making capability. This often results in people using autonomy as a means of justifying or rebuking particular behaviours. For example, “Her boss made her do it, so I don’t blame her” and “She is capable of leaving her boyfriend, so it’s her decision to keep suffering the abuse” are both statements that indirectly assess the autonomy of the subject in question.

In the first case, an employee is deemed to lack the autonomy to do otherwise and is therefore taken to not be blameworthy. In the latter case, the opposite conclusion is reached. In both, an assessment of the subject’s relative autonomy determines how their actions are evaluated by an onlooker.

Autonomy often appears to be synonymous with freedom, but the two concepts come apart in important ways.

Autonomy and freedom

There are numerous accounts of both concepts, so in some cases there is overlap, but for the most part autonomy and freedom can be distinguished.

Freedom tends to broader and more overt. It usually speaks to constraints on our ability to act on our desires. This is sometimes also referred to as negative freedom. Autonomy speaks to the independence and authenticity of the desires themselves, which directly inform the acts that we choose to take. This is has lots in common with positive freedom.

For example, we can imagine a person who has the freedom to vote for any party in an election, but was raised and surrounded solely by passionate social conservatives. As a member of a liberal democracy, they have the freedom to vote differently from the rest of their family and friends, but they have never felt comfortable researching other political viewpoints, and greatly fear social rejection.

If autonomy is the capacity a person has to self-govern their beliefs and decisions, this voter’s capacity to self-govern would be considered limited or undermined (to some degree) by social, cultural and psychological factors.

Relational theories of autonomy focus on the ways we relate to others and how they can affect our self-conceptions and ability to deliberate and reason independently.

Relational theories of autonomy were originally proposed by feminist philosophers, aiming to provide a less individualistic way of thinking about autonomy. In the above case, the voter is taken to lack autonomy due to their limited exposure to differing perspectives and fear of ostracism. In other words, the way they relate to people around them has limited their capacity to reflect on their own beliefs, values and principles.

One relational approach to autonomy focuses on this capacity for internal reflection. This approach is part of what is known as the ‘procedural theory of relational autonomy’. If the woman in the abusive relationship is capable of critical reflection, she is thought to be autonomous regardless of her decision.

However, competing theories of autonomy argue that this capacity isn’t enough. These theories say that there are a range of external factors that can shape, warp and limit our decision-making abilities, and failing to take these into account is failing to fully grasp autonomy. These factors can include things like upbringing, indoctrination, lack of diverse experiences, poor mental health, addiction, etc., which all affect the independence of our desires in various ways.

Critics of this view might argue that a conception of autonomy is that is broad makes it difficult to determine whether a person is blameworthy or culpable for their actions, as no individual remains untouched by social and cultural influences. Given this, some philosophers reject the idea that we need to determine the particular conditions which render a person’s actions truly ‘their own’.

Maybe autonomy is best thought of as merely one important part of a larger picture. Establishing a more comprehensively equitable society could lessen the pressure on debates around what is required for autonomous action. Doing so might allow for a broadening of the debate, focusing instead on whether particular choices are compatible with the maintenance of desirable societies, rather than tirelessly examining whether or not the choices a person makes are wholly their own.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Science + Technology

Is it right to edit the genes of an unborn child?

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

Enough and as good left: Aged care, intergenerational justice and the social contract

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

In defence of platonic romance

Explainer

Politics + Human Rights