Ethics Explainer: Particularism

When we ask ‘what is it ethical for me to do here?’, ethicists usually start by zooming out.

We look for an overarching framework or set of principles that will produce an answer for our particular problem. For instance, if our ethical dilemma is about eating meat, or telling a white lie, we first think about an overarching claim – “eating meat is bad”, or “telling lies is not permissible”.

Then, we think through what could make that overarching claim true: what exactly is badness? The hope is that we will be able to come up with an independently-justified, holistic view that can spit out a verdict about any particular situation. Thus, our ethical reasoning usually descends from the universal to the particular: badness comes from causing harm, eating meat causes harm, therefore eating meat is bad, therefore I should not eat this meat in front of me.

This methodology has led to the development of many grand unifying ethical systems; frameworks that offer answers to the zoomed-out question “what is it right to do everywhere?”. Some emphasise maximising value; others doing your duty, perfecting your virtue, or acting with love and care. Despite their different answers, all these approaches start from the same question: what is the correct system of ethics?

One striking feature of this mode of ethical enquiry is how little it has agreed on over 4,000 years. Great thinkers have been wondering about ethics for at least as long as they have wondered about mathematics or physics, but unlike mathematicians or natural scientists, ethicists do not count many more principles as ‘solid fact’ now than their counterparts did in Ancient Greece.

Particularists say this shows where ethics has been going wrong. The hunt for the correct system of ethics was doomed before it set out: by the time we ask “what’s the right thing to do everywhere?”, we have already made a mistake.

According to a particularist, the reason we cannot settle which moral system is best is that these grand unifying moral principles simply do not exist.

There is no such thing as a rule or a set of principles that will get the right answer in all situations. What would such an ethical system be – what would it look like; what is its function? So that when choosing between this theory or that theory we could ask ‘how well does it match what we expect of an ethical system?’.

According to the particularist, there is no satisfactory answer. There is therefore no reason to believe that these big, general ethical systems and principles exist. There can only be ethical verdicts that apply to particular situations and sets of contexts: they cannot be unified into a grand system of rules. We should therefore stop expecting our ethical verdicts to have a universal-feeling structure, like “don’t lie, because lying creates more harm than good”.

What should we expect our ethical verdicts to feel like instead? What does particularism say about the moment when we ask ourselves “what should I do?”. The particularist’s answer is mainly methodological.

First, we should start by refining the question so that it becomes more particular to our situation. Instead of asking “should I eat meat?” we ask “should I eat this meat?”. The second thing we should do is look for more information – not by zooming out, but by looking around. That is, we should take in more about our exact situation. What is the history of this moment? Who, specifically, is involved? Is this moment part of a trend, or an isolated incident?

All these factors are relevant, and they are relevant on their own: not because they exemplify some grand principle. “Occasion by occasion, one knows what to do, if one does, not by applying universal principles, but by being a certain kind of person: one who sees situations in a certain distinctive way”, wrote John McDowell.

Particularism, therefore, leaves a great deal up to us. It conceives of being ethical as the task of honing an individual capacity to judge particular situations for their particulars. It does not give us a manual – the only thing it tells us for certain is that we will fail if we try to use one.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

The Bear and what it means to keep going when you lose it all

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

A critical thinker’s guide to voting

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: The Sunlight Test

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Epistemology

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

What do we want from consent education?

What do we want from consent education?

Opinion + AnalysisPolitics + Human RightsRelationships

BY Georgia Fagan 11 MAY 2021

In mid-April this year a government-funded video was released which aimed to teach high-school aged Australians about sexual consent.

The video, which attempted to emphasise the importance of sexual consent by discussing the forced consumption of milkshakes, was widely criticised around the globe. It has since been removed from ‘The Good Society’ site, with secretary of the Department of Education Dr Michele Bruniges citing “community and stakeholder feedback” as reason for the action.

Widespread criticism of the video can be found online about the video’s sole use of metaphor to describe consent. Less present in the discussions is consensus on what a good consent education video would look like.

The underlying assumption in the video released by The Good Society is that issues of sexual consent can be managed by teaching adolescents that the rights of an individual are violated when an aggressor forces a ‘no’, or a ‘maybe’, into a ‘yes’. And, the video tells us, “that’s NOT GOOD!“.

Is it sufficient to tell adolescents to respect the rights of their peers in order to overcome issues of sexual violence? While rights may help us discuss what it is we want our societies to look like, they fail to assist us in getting others to care for, or value, the rights of others.

Sally Haslanger, Ford Professor of Philosophy and Women’s and Gender Studies at MIT (Massachusetts Institute of Technology) argues that actions are shaped by culture, and that cultures are effectively networks of social meanings which work in a variety of ways to shape our social practices. To change undesirable social practices, cultural change must also occur.

For example, successfully managing traffic is not just achieved by passing traffic laws or telling drivers that breaking the law is ‘not good’. Instead, Haslanger tells us that it requires inculcating “public norms, meanings and skills in drivers”. That is, we need a particular type of culture for traffic laws to adequately do what it is we want them to do. Applying this idea to sexual consent, we see that we are required to educate populations about why violating the preferences of our peers is indeed ‘not good’, after all.

Skirting around the issue fails to provide resources to move our culture to better recognise the deep injustice and harms of sexual violence.

Vague, euphemistic videos will likely fail to play even a minor role in transforming our current culture into one with fewer instances of sexual violence. This is due largely to the fact that Australia is comprised of social and political systems which fail to take the violence experienced by women and girls seriously.

Haslanger suggests that interventions such as revised legislation and moral condemnation will be inadequate when enforced onto populations whose values are incompatible with the goals of such interventions.

Attempting to address issues of sexual misconduct indirectly – as seen by The Good Society video – are likely to be unsuccessful in creating long term behavioural change. Skirting around the issue fails to provide resources to move our culture to better recognise the deep injustice and harms of sexual violence.

As Haslanger tells us, so long as we are a culture which has misogyny embedded into it, social practices will continue to develop that cause people to act in misogynistic ways. We are required to reshape our culture in a way that changes the value and importance of women.

So long as we are a culture which has misogyny embedded into it, social practices will continue to develop that cause people to act in misogynistic ways.

So, what will shift and transform embedded cultural practices? A better approach advocates educating audiences why consent is valuable, not just how to go about getting it. A population which fails to value the bodily autonomy and preferences of each of its members equally is not a population that will go about acquiring consent in successful and desirable ways.

Quick fix solutions such as ambiguously worded videos on matters of consent are likely to do very little for adolescents in a school system absent of a comprehensive sexual education, and where conversations on sexual conduct and interpersonal relationships remain marginalised.

We need to aim to create a generation of adolescents who are taught why sexual consent is important and why they should value the preferences of their peers. A culture which continues to keep sex ‘taboo’ by failing to explicitly discuss sexual relationships and the reasons why disrespecting bodily autonomy is “NOT GOOD!” will be one which fails to resolve its endemic misogyny and disregard for the lives of women and girls.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Is masculinity fragile? On the whole, no. But things do change.

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

Nurses and naked photos

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Assisted dying: 5 things to think about

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

The tyranny of righteous indignation

BY Georgia Fagan

Georgia has an academic and professional background in applied ethics, feminism and humanitarian aid. They are currently completing a Masters of Philosophy at the University of Sydney on the topic of gender equality and pragmatic feminist ethics. Georgia also holds a degree in Psychology and undertakes research on cross-cultural feminist initiatives in Bangladeshi refugee camps.

Pop Culture and the Limits of Social Engineering

Pop Culture and the Limits of Social Engineering

Opinion + AnalysisHealth + WellbeingRelationships

BY Lauren Rosewarne 19 APR 2021

In recent weeks, Unilever—the company behind a swag of domestic and personal care brands like Ponds and Lynx and Vaseline—announced that it would abandon “excessive digital alterations” in its advertising.

This isn’t a new public preoccupation for the company: in the 2010s one of its brands, Dove, aimed to position itself as a progressive corporation passionate about self-esteem and body image. Cue soap sales pitches packaged up with messages about hair-love and the perils of Photoshop.

I’m less interested in Unilever’s latest marketing gimmick, and much keener to examine the cultural debates that such a move contributes to.

In conversations with students about pop culture it quickly becomes apparent that most are convinced that The Media is a problem. Entertaining, enthralling, escapist, sometimes even educative – but a problem nonetheless. Students are always exceedingly well prepared to talk about the ways that The Media impacts self-esteem and are often armed with data on the extent of digital manipulation, ready to share robust views on “bias”.

Admittedly, I quite love that media literacy is like fluoride in the water for a generation and thoroughly appreciate that they can spot a filter or digital liposuction-induced wall-warp a mile away.

Being able to detect these things is an essential skill in navigating the glossy touts covering our screens. But such skills often lead to overconfidence about the next bit of the equation: what happens after we view all these artfully tweaked photos. About the consequences.

Such ideas aren’t new. Debates about the power and influence of media have kept scholars busy for over a century: radio was going to dangerously distract us, television was going to morally corrupt us, and the addictive properties of the internet would prevent us ever again turning away from our screens.

In discussing media content, in recognising a digitally altered photograph, we seem to dramatically overestimate our ability to predict what’s done with this information. Somehow apparently, instinctually, we just know that these images contribute to how we feel about our bodies, our relationships, our happiness. We just know that if The Media did a “better job” —reflected our lives more accurately, portrayed us in our full diversity and complexity —we’d have a better, more tolerant, less violent and vitriolic world.

In recognising a digitally altered photograph, we seem to dramatically overestimate our ability to predict what’s done with this information.

In talking about The Media as though it’s just one thing, one entity, and that the meetings are held on Thursdays to plot an agenda, overlooks not only the enormous variety of content—produced by different people in different countries with different budgets and different politics—but with the overarching agenda of just making money.

The output that we’re discussing when we refer to The Media —films and television and advertisements and news —are commercial endeavours. Content can absolutely be commercial and creative, or commercial and ideological. But when the primary goal is making money, suddenly all the social engineering often speculated upon is, in fact, just ways of interpreting content made purely to capture and hold our attention long enough to pay the bills.

Add to this, the nature of contemporary media consumption means not only are we getting a broader range of content but we’re dipping in and out of different eras of productions too: new episodes of shows stream on the same platforms as decades old movies and series. Add to this our ready access to content created all over the world. Such a broad catalogue complicates the idea of homogenous messages about anything, let alone beauty standards or cultural values.

The nature of pop culture means its content is consciously created for a broad audience. This doesn’t mean it’s not artistic or political or renegade —it can and sometimes is all of these things. But material produced for a popular audience is primarily made to make money; everything else it might achieve is an externality. Presuming all content producers are somehow in cahoots on an external cultural agenda is misguided.

Kidding ourselves that it’s the job of entertainment media to educate or flatter, overlooks the commercial underpinnings of pop culture.

Placing blame on The Media for our fraught feelings about our bodies, bank balances, love life overlooks there is no single Media entity but rather thousands of individual views, clicks, and likes that we electively undertake and which each play parts in shaping our world views, and which validate the very production decisions we often decry.

This project is supported by the Copyright Agency’s Cultural Fund.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Explainer

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Power

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Come join the Circle of Chairs

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Science + Technology

To fix the problem of deepfakes we must treat the cause, not the symptoms

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Elf on the Shelf is a fun and festive way to teach your child to submit to the surveillance state

BY Lauren Rosewarne

Lauren Rosewarne is an Associate Professor at the University of Melbourne. She is the author of 11 books, her latest—Why We Remake: The Politics, Economics and Emotions of Film and TV Remakes—was released in 2020.

The role of emotions in ethics according to six big thinkers

The role of emotions in ethics according to six big thinkers

Opinion + AnalysisRelationships

BY The Ethics Centre 16 APR 2021

It’s not easy to provide a clear definition of emotions. Philosophers and psychologists still haven’t agreed on what they are or whether they’re ethically important.

Most of us have lots of emotions and can name a dozen off the top of our heads pretty quickly. But there’s a lot more to understand. Why do they matter? Are we in control of our emotions? Should we prioritise our reason over our emotion?

Let’s take a look at what philosophy has to say.

Plato: reason rules emotion

For Ancient Greek philosopher Plato, emotion was a core part of our mind. But although it was core, he didn’t think emotions were very useful. He suggested we imagine our mind like a chariot with two horses. One horse is noble and cooperative, the other is wild and uncontrollable.

Plato thought the chariot rider was our reason and the two horses were different kinds of emotions. The noble horse represents our ‘moral emotions’ like righteous anger or empathy. The cranky horse represents more basic passions like rage, lust and hunger. Plato’s ideas set the precedent for Western philosophy in placing reason above and in control of our emotions.

Aristotle: what you feel says something about you

Aristotle had similar ideas and believed the wise, virtuous person would feel the right emotions at the right times. They would be depressed by sad things and angered by injustice. He also believed this appropriate kind of feeling was an important measure of whether you were a good person. He didn’t think you could separate the kind of person you were from the way you felt.

So if you find it funny when someone slips over in a puddle, Aristotle would argue that says something about you. It doesn’t matter whether you then offer them a towel or ask if they’re okay. The amusement you felt in response to their suffering reflects your character. He thought your job is to work hard so instead of laughing at such situations, you feel empathy and concern.

Hume: emotion rules reason

Scottish philosopher David Hume thought this view was naive. He famously said reason is “the slave of the passions”. By this he meant our emotions lead our reason – we never choose to do anything because reason tells us to. We do it because an emotion pushes us to act. For Hume, reason isn’t the charioteer driving our emotions, it’s more like the wagon being pulled along with no control over where it’s headed. It’s the horses – our emotions – calling the shots.

Hume and his friend Adam Smith developed a theory of moral sentiments that used emotion as the basis for their ethical theory. For them, we act virtuously not because our reason tells us it’s the right thing to do, but because doing the right thing feels good. We get a kind of ‘moral pleasure’ from acting well.

Kant: emotion strips our agency

Immanuel Kant thought this whole approach was entirely wrongheaded. He believed emotion had no place in our ethical thinking. For Kant, emotions were pathological – a disease on our thinking. Because we have no control over our emotions, Kant thought allowing them to govern our thinking and action made us ‘automated’, and that it is the only reason that made us autonomous and capable of making truly free decisions.

Freud: our unconscious drives us

More recent ideas have questioned whether there is such a thing as ‘pure reason’ (a concept Kant named one of his books after). Psychoanalysts like Sigmund Freud encouraged us to see our motivations as driven by unconscious urges and inclinations. More recent work in neuroscience has revealed the role unconscious bias and heuristics play in our beliefs, thinking and decisions.

This might make us wonder whether the idea that reason and emotion are two separate, rival forces is accurate. Another mode of thinking suggests our emotions are part of our reason. They express our judgements about how the world is and how we’d like it to be. Are we passive victims of our emotions? Do we spontaneously ‘explode’ with anger? Or is it something we choose? Our answer will help us determine how we feel about things like ‘crimes of passions’, impulsive decisions and how responsible we are for the feelings of other people.

Carol Gilligan: What is this sexist nonsense?

You may have noticed that all the names on this list so far are men. For psychologist Carol Gilligan, that’s not a coincidence. In her influential work In a Different Voice: Psychological Theory and Women’s Development, Gilligan argued that the widespread suspicion of ethical decisions made on the basis of emotion, concern for other people and a desire to maintain relationships was sexist. Most theorists had argued that reason, not emotion, should drive our decisions. Gilligan pointed out that most of the ‘bad’ ways of making decisions (like showing care for certain people or using emotion as a guide) tended to be the ways women reasoned about moral problems. Instead, she argued that a tendency to pay mind to emotions, value care and connection and prioritise relationships were different modes of moral reasoning; not suboptimal ones.

For a long time, reason and emotion have been pitted against one another. Today, we’re starting to understand that, in many ways, emotions and reason are the same. Our emotions are judgements about the world. Our reasoning is informed by our mood, our environment and a range of other factors. Perhaps the question shouldn’t be “should we listen to our emotions?” but instead “how do we develop the right emotional responses at the right time?” That way, we can rely on our emotions as one of many pieces of information we can use to make better decisions.

Follow The Ethics Centre on Twitter, Facebook, Instagram and LinkedIn.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Explainer

Business + Leadership, Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Moral injury

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

Joker broke the key rule of comic book movies: it made the audience think

WATCH

Relationships

What is ethics?

Big thinker

Relationships

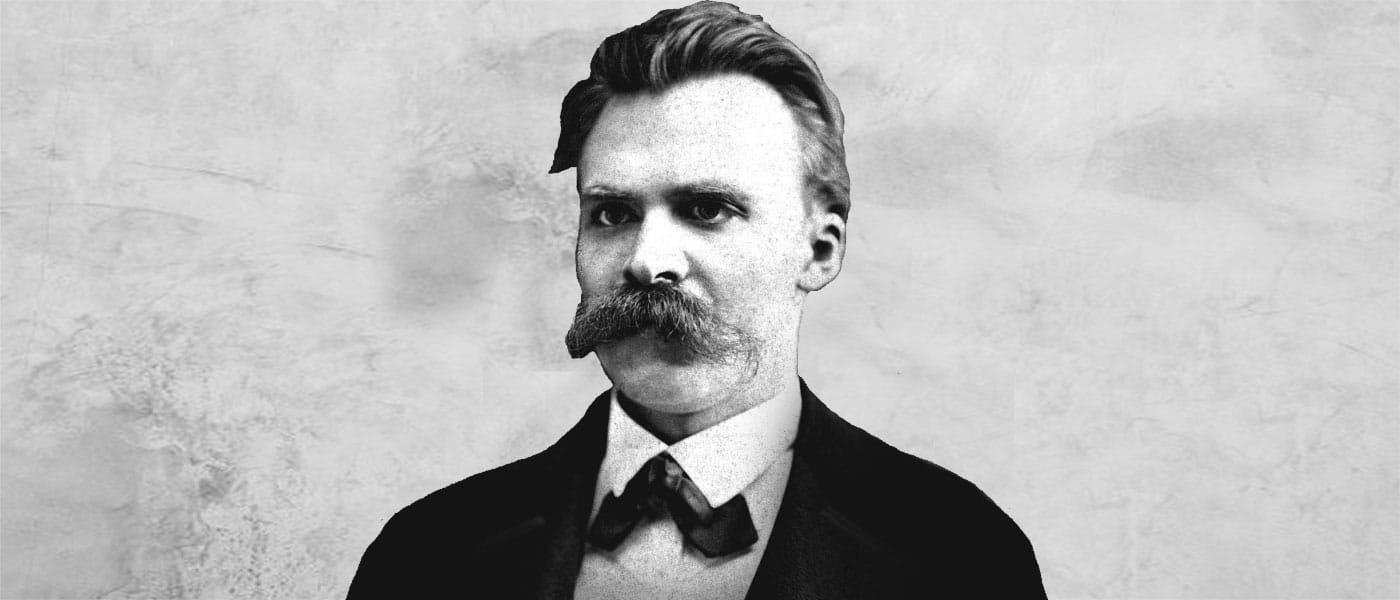

Big Thinker: Friedrich Nietzsche

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Big Thinker: Immanuel Kant

Immanuel Kant (1724—1804) was a transformative figure in modern Western philosophy due to his ground-breaking work in metaphysics and ethics.

He was one of the most influential philosophers of the 18th century, and his work in metaphysics and ethics have had a lasting impact to this day.

One of Kant’s greatest contributions to philosophy was his moral theory, deontology, which judges actions according to whether they adhere to a valid rule rather than the outcome of the action.

According to Kant’s theory, if you follow a valid moral rule, like “do not lie”, and it ends up with people getting harmed, then you’ve still done the right thing.

Deontology has since become one of the “big three” moral frameworks in the Western tradition, along with virtue ethics (based on Aristotle’s work) and consequentialism (exemplified by utilitarianism).

The will

Kant argued that morality cannot be based on our emotions or experience of the world, because this would leave it weak and subjective, and lacking the unconditional obligation that he believed was central to moral law.

“Every one must admit that a law has to carry with it absolute necessity if it is to be valid morally – valid, that is, as a ground of obligation,” he wrote.

His concern was that without this sense of unconditional obligation, a moral rule like ‘do not lie’ could compete with and be overridden by other concerns, like someone deciding they could lie because it suits their interests to do so, and they value their interests more than morality.

Rather, Kant argued that morality must be based on reason, which alone can provide the unconditional necessity that makes morality override our subjective interests.

Kant’s starting point was with our very nature, as inherently rational beings with ‘free will.’ He argued that it was this will that sets us apart as ’persons’ rather than ’things’ in the world, which are at the mercy of causal forces.

Our will gives us the ability to not only decide how to achieve our ends, but also about which ends to pursue; that’s just what freedom means. However, Kant argued that when we understand our nature as rational beings, we will understand that reason commands us to behave in a certain way, and this could form the basis of objective moral law.

The Categorical Imperative

Kant drew a famous distinction between different types of commands, or imperatives, which direct us how to act. One type are hypothetical imperatives.

So, one hypothetical imperative might say if you want to get to the 5:05 PM bus on time, then you must leave home no later than 5 p.m. Many moral systems of his time were effectively based on hypothetical imperatives, with the ends being things like achieving happiness or satisfying our interests.

However, Kant believed that such hypothetical imperatives could not be the basis of morality, as morality must bind us to act unconditionally and irrespective of any other ends we might have. Hence, someone who followed hypothetical imperatives in order to achieve ends like satisfying their desires or to avoid punishment was not acting morally.

He contrasted these with categorical imperatives do bind us unconditionally, no matter what other ends we might have. Kant argued that morality must be made up of categorical imperatives, as these are the only rules that can give morality its unconditional necessity.

“If duty is a concept which is to have meaning and real legislative authority for our actions, this can be expressed only in categorical imperatives and by no means in hypothetical ones,” he wrote.

The question becomes: where do categorical imperatives come from? Kant argued that there is really only one categorical imperative, and it is derived from our very nature as rational agents.

Once we abstract away all the contingent circumstances and subjective desires that people have, all we’re left with is our rational nature, which is something shared by all persons with a will. This objective point of view, stripped of all subjectivity, treats all rational agents equally, thus any imperative that directs them must apply universally.

From this Kant arrived at the categorical imperative, which is usually stated as “act only according to a maxim by which you can at the same time will that it shall become a general law”. This made all moral commands universal, so if something was wrong for me, then it must be wrong for all rational beings at all times.

This categorical imperative became the basis of all of Kant’s moral laws, effectively enshrining a particularly rarefied version of the Golden Rule.

Kingdom of Ends

Because we are inherently rational agents, we are both the authors and the subjects of the moral law. As such, Kant said that every person – indeed, every rational being – is an “end in himself, not merely as a means for arbitrary use by this or that will”.

This means we must treat all rational beings as ends in themselves and not just as means to achieve whatever ends we might have.

So, Kant argued, if every rational agent were to obey the categorical imperative, and treat everyone else as ends and not means, then it would lead to what he called the “kingdom of ends.”

It’s a kingdom in the sense that it’s a union of individuals who are all acting under a common law, and in this case the law is the categorical imperative, which urges everyone to treat everyone else as an end in themselves.

Kant admitted that this would be something of a moral utopia, but he put it forward as a vision for what a truly rational moral society might look like.

Controversy and Influence

Kant’s deontological ethics has been hugely influential but also controversial, being criticised by many philosophers as being based on an unrealistic conception of human rationality as well as being overly inflexible.

For example, Kant argued that it was always wrong to lie, because if one were to lie it would effectively endorse lying for everyone, and this would violate people’s rational autonomy.

However, we can imagine some situations where lying might be considered to be the right thing to do, such as lying to a prospective murderer in order to conceal their potential victims. Not to mention lying to one’s partner about their sartorial choices in order to maintain a harmonious domestic environment.

This is why many ethical consequentialists, who believe that it’s outcomes that really matter, have been known to gnash their teeth at the prospect that Kant demands we never lie.

Some thinkers have also – perhaps uncharitably – said that Kant effectively remade a kind of divine command theory of morality, which was popular in his Lutheran Christian community, except he replaced God with Reason (and even then, snuck a bit of God in on the side).

Kant’s philosophy has proven to be tremendously influential. His synthesis of empiricism and rationalism proved to be a breakthrough at the time, and his moral theory still has ardent defenders to this day.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Rationing life: COVID-19 triage and end of life care

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Free speech has failed us

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Philosophy must (and can) thrive outside universities

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

How to break up with a friend

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Are there limits to forgiveness?

There is a moment of gut-wrenching horror in Simon Wiesenthal’s The Sunflower: On the Possibilities and Limits of Forgiveness.

It begins with Wiesenthal, a Holocaust survivor, at the bedside of a fatally wounded German soldier.

“I am resigned to dying soon,” the soldier said to him. “But before that I want to talk about an experience which is torturing me. Otherwise, I cannot die in peace.” Comforted by Wiesenthal’s attention, the soldier began to confess to his role in a barbaric war crime where around two hundred Jewish men, women, and children were marched into a house and burned alive.

“I must tell you of this horrible deed,” cried the soldier. “Tell you because – you are a Jew.”

The soldier begs for the forgiveness that would grant him a peaceful death. His voice quivered, his hand trembled; his exhaustion and remorse were palpable. But Wiesenthal said nothing. He turned and left the soldier without a word.

A day later, he found out the soldier had died, unforgiven.

Perversely cruel as it might seem, the moment haunts Wiesenthal. Was it wrong to withhold forgiveness to the soldier, given he seemed genuinely repentant?

The Sunflower poses an invitation. “Ask yourself a crucial question, ‘what would I have done?’”, Wiestenthal dares the reader.

Wiesenthal tasks philosophers, theologians, psychologists, and genocide survivors with answering the very same question and features their responses throughout the book.

It’s true that many of us will not find ourselves in such a harrowing situation. But some will. Victims of crime can be invited to participate in restorative justice programs where they face the person who has wronged them. One in five Australian women above fifteen years old have been sexually assaulted or threatened – usually by someone they know.

In these cases, a victim may face an ethical dilemma they haven’t chosen. One that feels cruel to subject them to: they must decide whether to grant or withhold forgiveness.

Earning forgiveness

Should we forgive those who have wronged us? What makes someone worthy of forgiveness? Can forgiveness be wrong?

These questions are important for two reasons. First, forgiveness doesn’t always come naturally. At the moment when we’ve been wronged – often severely and traumatically – it’s doubly difficult to meditate on the ethics of forgiveness.

It’s painful, confusing and morally loaded: after all, who wants to be the person who doesn’t forgive when people who do – even when it seems impossible – is held up as a paragon of virtue and humanity?

But second, we need to understand how forgiveness should work because we’re all going to seek forgiveness at some point. We will all wrong someone else at some stage, in big ways or small. If we’ve done some work thinking about how we want to forgive, we’ve got a roadmap to follow when we’re the ones seeking forgiveness.

In Wiesenthal’s case, the genuine remorse shown by the German soldier is what troubles him. He believes the soldier is truly sorry for what he did. Not everyone agrees – was this man remorseful, or was he just scared to die? But whether or not the soldier was remorseful, we tend to agree that remorse matters for forgiveness. If someone is remorseful, we can at least think about forgiving them. If there’s no remorse, it doesn’t seem like a moral challenge to withhold forgiveness.

Genuine remorse

But expressing remorse is hard. It takes more than the non-pologies theologian L. Gregory Jones calls “spinning sorrow”. It involves acknowledging responsibility and wrongdoing. “I’m sorry you were offended” isn’t remorse. It’s performative, and puts the onus on the victim for their own suffering. In short, it says you were offended; I didn’t do anything offensive. Your suffering is on you. That’s not remorse, that’s pig-headedness.

Remorse demands us to understand the full extent of our wrongdoing.

That it was wrong, why it was wrong, and how that wrongdoing has harmed someone else. Which gives us good reason to think that Wiesthenthal’s soldier is not genuinely remorseful.

The horror of the Holocaust depended on the systematic denial of Jewish personhood. They weren’t seen as individuals – people with lives complex, unique, and infinitely valuable. Instead, they were objects to be treated as others saw fit.

By treating Wiesenthal as ‘a Jew’ – a generic placeholder for the actual people the solider murdered – the German soldier is continuing on with the same abhorrent thinking that led to his crimes in the first place. He doesn’t understand the depth of what he did. How can he then apologise in a way that warrants forgiveness?

The politics of forgiveness

To step away from Wiesenthal’s case for a second, how often do we witness apologies that fail to show any awareness of the source of the wrongdoing? On a political level, we see apologies offered by those who continue to benefit from those injustices. Does this constitute remorse, or a genuine understanding of the wrongdoing?

Take political apologies, for instance: some naysayers to Australia’s National Apology to the Stolen Generations argued that the people apologising weren’t the ones who had done anything wrong. The claim here is if we haven’t done anything wrong, we don’t need to be forgiven; and if we don’t need to be forgiven, why would we apologise?

This perhaps misses an important consideration.

If we continue to benefit from a past wrong and fail to address the source of the continued disadvantage, there is a sense in which we’ve prolonged the wrongdoing.

However, it also calls our attention to the role of status in forgiveness. I cannot offer an apology for a wrong I haven’t been involved in.

Equally, I cannot forgive unless I have been wronged, which also complicates the politics of forgiveness: who has the moral authority to forgive? Could Wiesthenthal, who was treated as a ‘generic Jew’ by the soldier, actually forgive – even if he wanted to? After all, the soldier’s crimes did not directly harm him.

Eva Kor was a Holocaust survivor who offered forgiveness to Josef Mengele, doctor of the notorious ‘twin experiments’ in Auschwitz. Her actions brought criticism from other survivors, who said Kor wasn’t entitled to offer forgiveness on behalf of others. Nor should she pressure them to forgive when they were not ready.

Jona Laks, another ‘Mengele twin’, refused to forgive. In Mengele’s case, this is understandable. But what if there was genuine remorse, a commitment to change, and steps to address the wrongdoing? Would it be wrong to refuse forgiveness?

On some occasions, it seems so. For instance, we consider pettiness – when someone is unable to move past very slight or non-existent wrongs – as a vice, or a mark of bad character. I’m not suggesting a Holocaust survivor (or any Jewish person) who refused to forgive the Nazis under any condition was being petty, but this takes us back to the question posed earlier.

Is there anything that’s unforgiveable?

This brings us to the final question: are there some things which are unforgiveable? How should we think about them?

Maybe. Philosopher, Hannah Arendt believed that unforgiveable crimes were those where no punishment could be given that would be proportionate to the crime itself. Where no atonement is possible, no forgiveness is possible. For Arendt, these crimes are an evil beyond redemption.

In contrast, French philosopher Jacques Derrida argued that conditional forgiveness is in fact, not forgiveness. By withholding forgiveness until considerations (like remorse) are met, Derrida believed that we are forgiving someone who is already innocent – that is, someone who no longer needs forgiveness. Only the unremorseful person remains guilty, and only the unremorseful person actually needs forgiveness.

As a result, Derrida concludes with a paradox: only the unforgiveable can be truly forgiven.

Derrida traces his thinking back to religious traditions where forgiveness is unconditional and uneconomic. It is a gift, not a transaction. This is a view L. Gregory Jones believes is centrally important to avoid “weaponising forgiveness”.

I think it’s important to remember that forgiveness should always be a gift and not an expectation. It’s unfair to expect any person who has been victimized, especially if it’s raw, to be ready to forgive.

And — this is particularly important in domestic violence and other kinds of forgiveness — the expectation of forgiveness is also used as a weapon to punish and perpetuate a cycle. It’s often the case in domestic violence, for example, where the abuser will come and say, “you need to forgive me because you’re a Christian” and the person feels obligated to do that. All that does is perpetuate and intensify the violence rather than remedy it.

So how should we think about Wiesenthal’s case? What would we do? It seems quite evident that he had no duty to forgive this Nazi – and that perhaps he had no right to do so. However, if we set aside the question of legitimacy, how might he make this decision?

Some philosophers have argued that self-respect is central to the way we think about forgiveness. Forgiveness involves a recognition that we have value – that we did not deserve to be wronged, and the other person should not have wronged us.

By forgiving, we assert our status in the moral community – our dignity.

However, others might believe such forgiveness reduces their self-worth – especially if this forgiveness leaves the wrongdoer better off than the victim. Forgiveness can grant peace to wrongdoers – as the German soldier knew – but often leaves the victim alone in their trauma.

Author Susan Cheever once wrote that “Being resentful is like taking poison and waiting for the other person to die”. For some, this may be true. For others, forgiving might be like giving someone a drink while you are dying of thirst.

Should Wiesenthal have forgiven the soldier? It might all depend on what he could swallow and still look at himself in the mirror.

It may all come down to what he wanted to see when he looked in the mirror.

Follow The Ethics Centre on Twitter, Facebook, Instagram and LinkedIn.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

You don’t like your child’s fiancé. What do you do?

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

The niceness trap: Why you mustn’t be too nice

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships

Workplace romances, dead or just hidden from view?

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Power and the social network

BY Matthew Beard

Matt is a moral philosopher with a background in applied and military ethics. In 2016, Matt won the Australasian Association of Philosophy prize for media engagement. Formerly a fellow at The Ethics Centre, Matt is currently host on ABC’s Short & Curly podcast and the Vincent Fairfax Fellowship Program Director.

Seven Female Philosophers You Should Know About

Seven Female Philosophers You Should Know About

Big thinkerRelationships

BY The Ethics Centre 8 MAR 2021

There’s no question that philosophy is littered with the workings of male minds. What’s less known are the many brilliant women whose contributions throughout history have shaped our world today. Here are seven female philosophers to celebrate this International Women’s Day.

Mary Wollstonecraft

Mary Wollstonecraft (1759-1797) was a writer, philosopher and social activist. Wollstonecraft’s manifesto is 225+ years old, but far from obsolete. She passionately articulated for women to have equal rights to men in A Vindication of the Rights of Woman in 1792, a century before the term feminism was coined. In a social system where women were “kept in ignorance” by the socioeconomic necessity of marriage and a lack of formal education, Wollstonecraft advocated for a free national schooling system where girls and boys would be taught together. The word patriarchy was not available to Wollstonecraft, yet she argued men were invested in maintaining a society where they held power and excluded women.

“My own sex, I hope, will excuse me, if I treat them like rational creatures, instead of flattering their fascinating graces, and viewing them as if they were in a state of perpetual childhood, unable to stand alone.”

bell hooks

An outspoken professor, author, activist and cultural critic, bell hooks (1952 – 2021) work explores the connections between race, gender, and class. “Ain’t I A Woman” laid the groundwork for hooks progressive feminist theory, linking historical evidence of the sexism endured by black female slaves to its long-standing legacy on black women today. Born Gloria Watkins, hooks adopted her pen name after her late grandmother, wanting it written in lower case to shift the attention from her identity to her ideas. Now 38 years on from its original publication, her work remains radically relevant to the world today.

“A devaluation of black womanhood occurred as a result of the sexual exploitation of black women during slavery that has not altered in the course of hundreds of years.”

Simone De Beauvoir

Simone de Beauvoir (1908-1986) was a French author, feminist and existential philosopher. She lived an unconventional life as a working experiment of her ideas. As an existentialist, de Beauvoir believed in living authentically and argued that people must choose for themselves who they want to be and how they want to live. The more pressure society – and other people – place on you, the harder it is to make that authentic choice, particularly for women. In her best-known work, ‘The Second Sex’ she famously posed that women are not born, they are made. Meaning that there is no essential definition of womanhood, rather social norms work hard to force them into a notion of femininity

“Man is defined as a human being and woman as a female – whenever she behaves as a human being she is said to imitate the male.”

Shulamith Firestone

Shulamith Firestone (1945-2012) was a writer, artist, and feminist whose book, The Dialectic of Sex, argued the structure of the biological family was primarily to blame for the oppression of women. Firestone proposed that over the course of human history, society itself had come to mirror the structure of the biological family and was the source from which all other inequalities developed. With a radical and uncompromising vision, she advocated for the development of reproductive technologies that would free women from the responsibilities of childrearing, dismantle the hierarchy of family life and set the foundations for a truly egalitarian society.

“the end goal of feminist revolution must be… not just the elimination of male privilege, but of the sex distinction itself.”

Hannah Arendt

Johannah “Hannah” Arendt (1906 – 1975) was a German Jewish political philosopher who left life under the Nazi regime for nearby European countries before settling in the United States. Informed by the two world wars she lived through, her reflections on totalitarianism, evil, and labour have been influential for decades. Arendt’s most well-known idea is “the banality of evil”, explored in 1963 in a piece for The New Yorker that covered the trial of a Nazi bureaucrat, Adolf Eichmann. Following the election of Donald Trump, sales of Arendt’s book The Origins of Totalitarianism, already one of the most important works of the 20th century, increased by 1600%.

“The sad truth is that most evil is done by people who never make up their minds to be good or evil.”

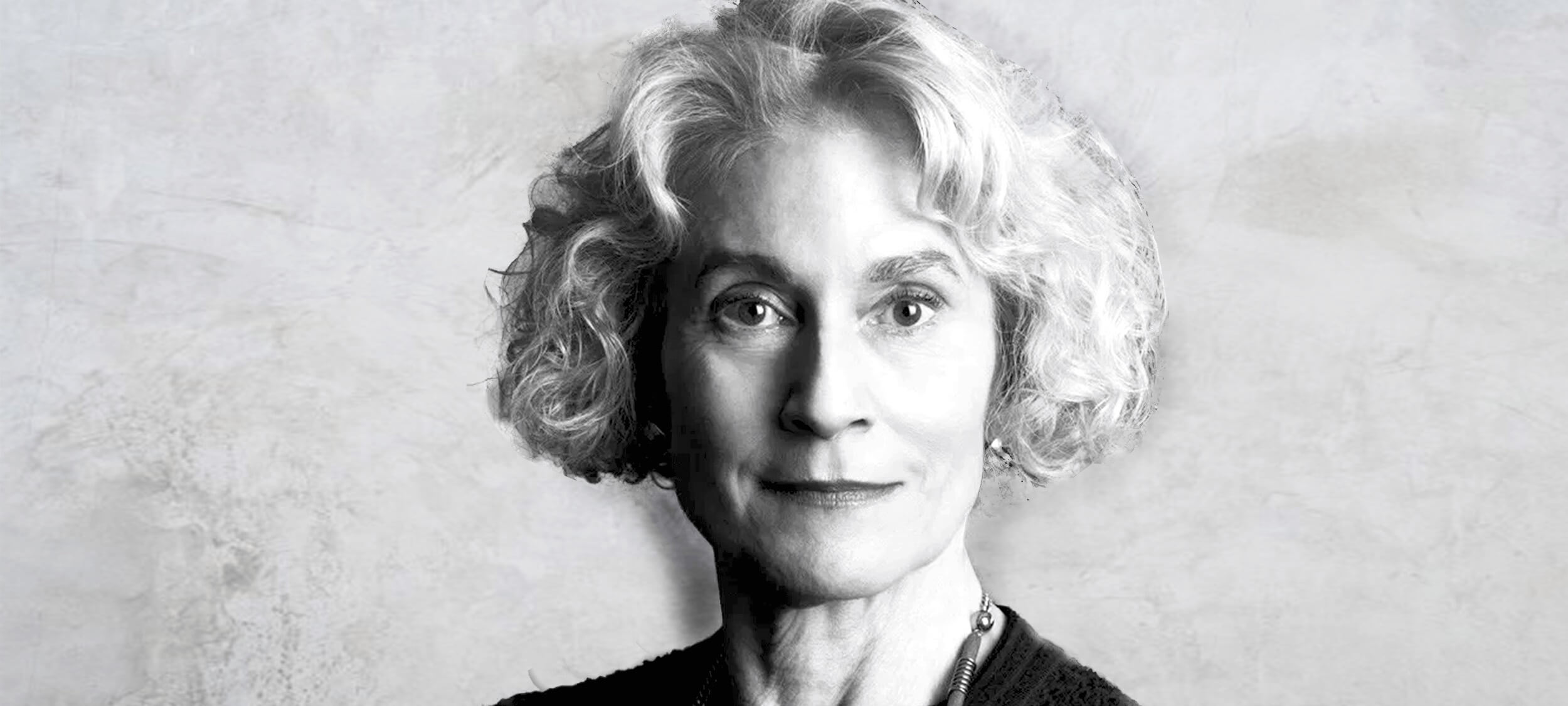

Martha Nussbaum

Martha Nussbaum (1947-present) is one of the world’s most influential living moral philosophers, trailblazing in her philosophical advocacy for religious tolerance, feminism and the merits of emotions. Nussbaum believes the ethical life is about vulnerability and embracing uncertainty. She famously argued for the place of emotions within politics, saying democracy simply doesn’t work without love and compassion. In ‘Not for Profit: Why Democracy Needs the Humanities’ Nussbaum took on the education system, proposing that its role is not to produce an economically productive and useful citizen, but people who are imaginative, emotionally intelligent and compassionate.

“To be a good human being is to have a kind of openness to the world, an ability to trust uncertain things beyond your own control.”

Simone Weil

Simone Weil (1909–1943) was a Philosopher, Christian mystic and political activist in the French Resistance, who TS Eliot called a “genius akin to that of the saints”. Weil gave attention to working conditions and is known to have given up a life of privileged to work in factories. This experience shaped her writings, which consider the relationship between individual and state, the nature of knowledge, the spiritual shortcomings of industrialism and suffering as key to the human condition. In The Need for Roots, Weil argued that society suffered an ‘uprootedness’, a deep malaise in the human condition due to a lack of connectedness to past, land, community and spirituality.

“To be rooted is perhaps the most important and least recognized need of the human soul.”

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Big thinker

Relationships

Big Thinker: Thomas Nagel

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Ethical judgement and moral intuition

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Only love deserves loyalty, not countries or ideologies

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Climate + Environment

Blindness and seeing

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Big Thinker: Aristotle

It is hard to overstate the impact that Aristotle (384 BCE—322 BCE) has had on Western philosophy.

He, along with his teacher Plato, set the tone for over two millennia of philosophical enquiry, with much subsequent work either building on or refuting his ideas.

His influence on philosophy has been unparalleled for over two thousand years, in fields including logic, metaphysics, science, ethics and politics.

Aristotle was born in the 4th century BC in Thrace, in the north of Greece. At around 18 years of age he moved south to Athens, the capital of philosophical thought, to study under Plato at his famous Academy. He spent around two decades there, absorbing – but not always agreeing with – Plato and his disciples.

After Plato’s death, he departed Athens and landed a gig tutoring the teenage Alexander of Macedon – soon to be Alexander the Great. However, it appears Aristotle summarily failed to imbue the budding general with a taste for either philosophy or ethics.

After Alexander was appointed regent of Macedon at the age of 16, Aristotle returned to Athens, where he established the Lyceum, his own philosophical school where he taught and wrote on a startling array of topics.

His followers became known as peripatetics, after the Greek word for “walking”, due to the walkways that surrounded the school and Aristotle’s reputed tendency to give lectures on the move.

Ethics and Eudaimonia

One of the areas of lasting impact was Aristotle’s work on ethics and politics, which he considered to be intimately related subjects (much to the surprise of modern folk).

His ethical theory was based on the idea that each of us ultimately seeks a concept he called eudaimonia, often translated as “happiness” but better rendered as “flourishing” or “wellbeing.”

The basic idea is that every (non-frivolous) thing we do is directed towards achieving some end. For example, you might fetch an apple from the fruit bowl to sate your hunger. But it doesn’t stop there. You might sate your hunger to promote your health, and you might promote your health because it enables you to do other things that you want to do – and so on.

Aristotle argued that if you follow this chain of ends all the way down, you’ll eventually reach something that you do because it’s an ‘end in itself’, not because it leads to some other end. He argued that the enlightened individual would inevitably arrive at the single ultimate end or good: eudaimonia.

Aristotle’s ethical theory is more like a theory of enlightened prudence or ‘practical wisdom’, which he called phronesis, that helps guide people towards achieving eudaimonia.

This sets Aristotle’s ethics apart from many modern ethical theories, such as utilitarianism, in that he’s not calling for us to maximise happiness or eudaimonia for all people but only helping us to live a good life.

Compared to more modern ethical theories, he is also less focused on explicit issues of preventing harm or preventing injustice than on the cultivation of good people.

Whereas the primary question guiding many ethical theories is ‘what should we do?’, Aristotle’s main concern is ‘how should we live?’.

Virtues and Friendship

This doesn’t mean Aristotle disregarded how we ought to behave towards others. Indeed, he argued that the best way to achieve eudaimonia was to embody certain virtues, such as honesty, courage and charity, which encourage us to be good to other people.

Each of these virtues occupies a “golden mean” between two extremes, which were considered vices. So too little courage was cowardice, and too much was recklessness, but just enough would lead to decisions that would promote eudaimonia.

He also lent us a useful term, akrasia, which means a kind of weakness of will, whereby people do the wrong thing not due to embodying vices, but by some inability to resist temptation.

We have all likely experienced akrasia from time to time, such as when we devour that last cookie or lie to escape blame, which we know is not conducive to our health or ethical flourishing.

While Aristotle’s “virtue ethics” fell out of favour for many centuries, it has enjoyed a resurgence since the mid-20th century and has a growing following today.

Aristotle also argued that one of the benefits of being a virtuous person was the kinds of friendships you could form.

The second reason is because you think they’re fun to be around, such as when two people simply enjoy each other’s company or enjoy shared activities like watching sport or playing board games, but don’t have any deeper connection when those activities are absent.

It’s the third type of friendship that Aristotle thought was the highest, which is when you like someone because they are a good person.

This is a mutual recognition of virtuous character, and you have reciprocal good will, where you genuinely care for them – even love them – and want the best for them. Aristotle argued that by cultivating virtues, and seeking out other virtuous people, we could form the strongest and most nourishing friendships.

Interestingly, modern science has vindicated the idea that one of the most important factors in living a happy and fulfilled life is the number of genuine and deep relationships one has, particularly with friends whom they care for and who care for them in return.

Artistotle on Politics

Aristotle’s political theory concerned how to structure a society in such a way that it enabled all its citizens to achieve eudaimonia.

His ancient Greek predilections – as well as the influence of Plato, who believed society should be ruled by ‘Philosopher Kings’ – are visible in his contempt for democracy in favour of rule by an enlightened aristocracy or monarchy.

However, Aristotle disagreed with his mentor in one important respect: Aristotle favoured private property, which he said promoted personal responsibility and fostered a kind of meritocracy that treated great achievers as being more morally worthy than the ‘lazy’.

The breadth, sophistication and influence of Aristotle’s thinking is formidable, especially considering that we only have access to 31 of the 200+ treatises that he wrote during his lifetime.

Tragically, the rest were lost in antiquity. While much of Aristotle’s philosophy is contested today given developments in logic and science over the last few centuries, arguably many of these developments were built on or were inspired by his work.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Science + Technology

With great power comes great responsibility – but will tech companies accept it?

Big thinker

Relationships

Big Thinker: Martha Nussbaum

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Peter Singer on charitable giving

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture, Politics + Human Rights

Pleasure without justice: Why we need to reimagine the good life

BY Dr Tim Dean

Dr Tim Dean is Philosopher in Residence at The Ethics Centre and author of How We Became Human: And Why We Need to Change.

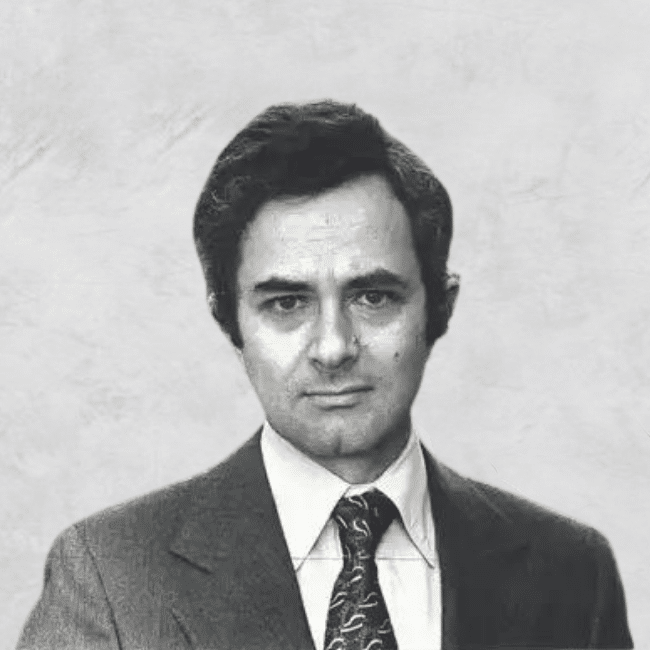

Tim Soutphommasane on free speech, nationalism and civil society

Tim Soutphommasane on free speech, nationalism and civil society

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + LeadershipPolitics + Human RightsRelationships

BY The Ethics Centre 18 FEB 2021

We believe conversations matter. So when we had the opportunity to chat with Tim Soutphommasane we leapt at the chance to explore his ideas of a civil society. Tim is an academic, political theorist and human rights activist. A former public servant, he was Australia’s Race Discrimination Commissioner at the Australian Human Rights Commission from 2013 – 2018 and has been a guest speaker at the Festival of Dangerous Ideas. Now a professor at Sydney University, he shared with The Ethics Centre his thoughts on the role of the media, free speech, racism and national values.

What role should the media play in supporting a civil society?

The media is one place where our common life as a society comes into being. It helps project to us our common identity and traditions. But ideally media should permit multiple voices, rather than amplify only the voices of the powerful. When it is dominated by certain interests, it can destroy rather than empower civil society.

How should a civil society reckon with the historical injustices it benefits from today?

A mature society should be able to make sense of history, without resorting to distortion. Yet all societies are built on myths and traditions, so it’s not easy to achieve a reckoning with historical injustice. But, ultimately, a mature society should be able to take pride in its achievements and be critical of its failings – all while understanding it may be the beneficiary of past misdeeds, and that it may need to make amends in some way.

Should a civil society protect some level of intolerance or bigotry?

It’s important that society has the freedom to debate ideas, and to challenge received wisdom. But no freedom is ever absolute. We should be able to hold bigotry and intolerance to account when it does harm, including when it harms the ability of fellow citizens to exercise their individual freedoms.

What do you think we can do to prevent society from becoming a ‘tyranny of the majority’?

We need to ensure that we have more diverse voices represented in our institutions – whether it’s politics, government, business or media.

What is the right balance between free speech and censorship in a civil society?

Rights will always need to be balanced. We should be careful, though, to distinguish between censorship and holding others to account for harm. Too often, when people call out harmful speech, it can quickly be labelled censorship. In a society that values freedom, we naturally have an instinctive aversion to censorship.

How can a society support more constructive disagreement?

Through practice. We get better at everything through practice. Today, though, we seem to have less space or time to have constructive or civil disagreements.

What is one value you consider to be an ‘Australian value’?

Equality, or egalitarianism. As with any value, it’s contested. But it continues to resonate with many Australians.

Do you believe there’s a ‘grand narrative’ that Australians share?

I think a national identity and culture helps to provide meaning to civic values. What democracy means in Australia, for instance, will be different to what it means in Germany or the United States. There are nuances that bear the imprint of history. At the same time, a national identity and culture will never be frozen in time and will itself be the subject of contest.

And finally, what’s the one thing you’d encourage everyone to commit to in 2021?

Talk to strangers more.

To read more from Tim on civil society, check out his latest article here.

Tim Soutphommasane is a political theorist and Professor in the School of Social and Political Sciences, The University of Sydney, where he is also Director, Culture Strategy. From 2013 to 2018 he was Race Discrimination Commissioner at the Australian Human Rights Commission. He is the author of five books, including The Virtuous Citizen (2012) and most recently, On Hate (2019).

This project is supported by the Copyright Agency’s Cultural Fund.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Parenting philosophy: Stop praising mediocrity

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Science + Technology

The complex ethics of online memes

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Perils of an unforgiving workplace

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Lying

Join our newsletter

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Ethics Explainer: Moral Relativism

Moral relativism is the idea that there are no absolute rules to determine whether something is right or wrong. Unlike moral absolutists, moral relativists argue that good and bad are relative concepts – whether something is considered right or wrong can change depending on opinion, social context, culture or a number of other factors.

Moral relativists argue that there is more than one valid system of morality. A quick glance around the world or through history will reveal that no matter what we happen to believe is morally right and wrong, there is at least one person or culture that believes differently, and holds their belief with as much conviction as we do.

This existence of widespread moral diversity throughout history, between cultures and even within cultures, has led some philosophers to argue that morality is not absolute, but rather that there might be many valid moral systems: that morality is relative.

Understanding Moral Relativism

It’s worth pointing out that the philosophical notion of moral relativism is quite different from how the term is often used in everyday conversation. Many people have been known to say that others are entitled to their views and that we have no right to impose our view of morality on them.

This might look like moral relativism, but in many cases it’s really just an appeal for tolerance in a pragmatic or diplomatic sense, while the speaker quietly remains committed to their particular moral views. Should that person be confronted with what they consider a genuine moral violation, their apparent tolerance is likely to collapse back into absolutism.

Moral relativism is also often used as a term of derision to refer to the idea that morality is relative to whatever someone happens to believe is right and wrong at the time. This implies a kind of radical anything-goes moral nihilism that few, if any, major philosophers have supported. Rather, philosophers who have advocated for moral relativism of some sort or another have offered far more nuanced views. One reason to take moral relativism seriously is the idea that there might be some moral disagreements that cannot be conclusively resolved one way or the other.

If we can imagine that even idealised individuals, with perfect rationality and access to all the relevant facts, might still disagree over at least some contentious moral matters – like whether suicide is permissible, if revenge is ever justified, or whether loyalty to friends and family could ever justify lying – then this would cast doubt on the idea that there is a single morality that applies to all people at all times in favour of some kind of moral relativism.

Exploring Relativity

The key question for a moral relativist is what morality ought to be relative to. Gilbert Harman, for example, argues that morality is relative to an agreement made among a particular group of people to behave in a particular way. So “moral right and wrong (good and bad, justice and injustice, virtue and vice, etc.) are always relative to a choice of moral framework. What is morally right in relation to one moral framework can be morally wrong in relation to a different moral framework.

And no moral framework is objectively privileged as the one true morality.

It’s like different groups playing different codes of football, wherein one code a handball might be allowed but in another, it’s prohibited. So whether handball is wrong is simply relative to which code the group has agreed to play.

Another philosopher, David Wong, argues for “pluralistic relativism,” whereby different societies can abide by very different moral systems. So morality is relative to the particular system they have constructed to solve internal conflicts and respond to the social challenges their society faces.

However, there are objective facts about human nature and wellbeing that constrain what a valid moral system can look like, and these constraints “are not enough to eliminate all but one morality as meeting those needs.” They do eliminate perverse systems, like Nazi morality that would justify genocide, but allow for a wide range of other valid moral views.

Moral relativism is a much misunderstood philosophical view. But there is a range of sophisticated views that attempt to take seriously the great diversity of moral systems and attitudes that exist around the world, and attempts to put them in the context of the social and moral problems that each society faces, rather than suggesting there is a single moral code that ought to apply to everyone at all times.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Metaphysical myth busting: The cowardice of ‘post-truth’

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Can we celebrate Anzac Day without glorifying war?

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships, Science + Technology

When do we dumb down smart tech?

Explainer

Relationships