Ask an ethicist: How should I divvy up my estate in my will?

Ask an ethicist: How should I divvy up my estate in my will?

Opinion + AnalysisRelationships

BY Tim Dean 12 JUN 2025

I’m in the process of writing my will, but I’m unsure about how I should split my estate among my children. Should it be divided equally? Or should I give more to one of my children, who needs it more?

It’s hard enough avoiding thinking about our own mortality, but then we also have to contemplate the ructions that could erupt after we depart the mortal coil. Is that fair? Probably not. But at least you can attempt to be fair in how you dole out your mortal leftovers.

The good news is that philosophers have spent centuries coming up with ways to carve up a bundle of stuff – whether that’s a pie, a national budget or a deceased estate – and distribute it fairly. The bad news is they haven’t settled on just one right way to do it. Still, if you care about fairness, then there are a few approaches you can take.

The simplest is to just split things perfectly evenly. Say you have $100,000 left in the bank; you have four children: you divide it four ways, so they get $25,000 each. Simple. That’s called “strict egalitarianism,” which says that stuff should be distributed so that everyone ends up with exactly the same amount.

But my youngest child has had a string of bad luck that has left them struggling to get by. Meanwhile, the three older ones are cruising. Does that mean I should leave more to the needy one and less to the others?

And therein lies a problem with strict egalitarianism: we don’t all start off in the same position. So sharing stuff around equally might just exacerbate existing inequalities. Like, it would be weird to cut a pie four ways and give an equal slice to each diner if three of them were stuffed full and one was starving to death.

That’s why the “welfare approach” urges us to think carefully about how each individual is going right now, and make sure that we distribute our stuff so that it generates the maximum overall welfare for everyone. So, if three of your children are doing well – i.e. their welfare is currently high – and one is lagging behind, then it would be fair to give the one who’s struggling a bigger slice of the pie.

That doesn’t necessarily mean they should get all the pie. Things like money and pleasure often have diminishing returns. So giving everything you have to the struggling child might not elevate their welfare much more than just giving them half. And it might turn out that giving a small amount to the three children who are better off will still make a significant difference to their welfare. So get your calculator out, start plugging in welfare values, and run the numbers to see who gets what.

Look, I hear you, but my older kids say that my youngest is an idiot, and keeps making terrible decisions, like investing all their money in crypto. Would it be unfair to the others if I just propped them up?

Speaking of divvying up pies, this brings us to the idea of “dessert”. Fairness is not just about making sure that everyone ends up on even footing. It can also mean rewarding those who work hard and act responsibly, and not coddling those who are lazy and irresponsible. If you keep feeding that hungry person pie, then they might not bother making themselves dinner and rely on your charity to keep them fed.

So, the dessert-based approach says you should think about how much of your fortune each of your children deserves. You might look at how hard they work, or how much they contribute to looking after their families, or how much time and energy they have spent caring for you.

Well, if that’s the case, then none of them deserve it, because they all forgot to call me on my last birthday. That said, I do like the idea of making sure my inheritance goes where it can do the most good. I’m just not convinced that it can do so in the pockets of my ungrateful children.

Then perhaps you need to broaden your horizons beyond your family. Even a small donation to the right charity can transform lives, producing far better outcomes in terms of welfare than giving it you children, especially if they are already living comfortably.

In fact, it’s well known that inheritances are a major contributor to perpetuating intergenerational inequality. Rich people give their stuff to rich kids, who can use that to generate even more riches throughout their lifetime. I mean, have you seen the property market these days? It’s almost impossible to get in without an inheritance propping you up. So what do poorer people do?

That’s why economists say one of the best ways to flatten the wealth in a society is to tax inheritances, especially big ones. Although that policy is strangely unpopular with many voters, especially those who own multiple properties. Go figure.

So, if you decide to break the cycle and do the most good with your inheritance, there are plenty of charities that will more than happily distribute it to those with the greatest need. Just don’t expect your kids to be thrilled with your decision.

BY Tim Dean

Dr Tim Dean is a public philosopher, speaker and writer. He is Philosopher in Residence and Manos Chair in Ethics at The Ethics Centre.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships

How the Canva crew learned to love feedback

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

How to pick a good friend

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Science + Technology, Society + Culture

5 things we learnt from The Festival of Dangerous Ideas 2022

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Ethics of Care

Do we exaggerate the difference age makes?

Do we exaggerate the difference age makes?

Opinion + AnalysisSociety + CultureRelationships

BY Emma Wilkins 19 MAY 2025

A few weekends ago, I made a parenting mistake. I didn’t realise in the moment. The penny didn’t drop, until a good friend made a comment afterwards.

My family was hosting a brunch with several other families. After a few hours in the noisy, sticky, fray, one of our kids asked to retreat. Sensing my hesitation, he pointed out that none of the other guests were of his age.

Partly in acknowledgement, and partly because the retreat he had in mind involved attacking the thistles taking over our front lawn, I let him slip away.

Shortly afterwards, sitting with a group of parents, watching syrup-crazed children run riot out the back, I explained his absence. One parent stopped me at the words “no one my age”. He was wondering, aloud, why age was relevant – let alone a reason to retreat.

The friend who stopped me was one who’d moved to Australia as an adult. He saw the culture he was living in, and the one he’d left, with the benefit of fresh, discerning eyes. Before he finished making it, I saw his point.

Why not expect our kids to socialise with others, regardless of age? Why not encourage them to enjoy the company of those younger than them, and the company of those older than them?

The friend in question told us he’d noticed this propensity to segregate by age before, and resolved not to succumb. He said he makes a point of crossing age divides, of greeting and conversing without discriminating, at social gatherings. Children, in particular, often seem puzzled by his attention. Sometimes they don’t return a greeting, or answer a question, they just stare. The stare might be translated to mean, “Why is this old dude talking to me?” or, “Why would I talk to this old dude?”. Sometimes they mutter something before running off, sometimes they just run off.

As the friend spoke, I recalled a social event where the child who’d just retreated had ended up deep in conversation with a grandparent he’d never met. I wished this image had come to mind earlier, prompted by the words “no one my age”. I knew both he and that grandparent had enjoyed their conversation, maybe as much as the cake, maybe more. It was proof age needn’t be a barrier.

Age needn’t be a barrier, but my friend’s description of children giving him quizzical looks when he acknowledges them suggests us adults are making it one. It suggests so few adults – not counting relatives – take the time to talk to them, that when one does it’s an anomaly.

I consider how much attention I pay to children who aren’t my own at social gatherings.

Sometimes, my attention is on fellow grown-ups and I don’t think to make an effort. At other times, I think to – then I overthink. I see a child and a compliment comes to mind but it’s based on their appearance, or a stereotype, so I censor myself. Or a question comes to mind, but the child in question is a teen and I imagine it will either induce a deep inward groan – “Not another adult asking what I’ll do post-school, how should I know?” – or defensiveness, or self-consciousness, or insecurity…

What lame excuses! If I want my kids to enjoy and initiate interactions and relationships with people of all ages, to throw age-related bias out the window, I should too – even if it requires a little bit of extra effort, creativity, or risk. Who cares if I induce an eye-roll or a groan? What matters is that I don’t just take a genuine interest, and show genuine interest, in adult’s lives, but in the lives of children, too.

I’m sure political philosopher David Runciman also attracts plenty of eye-rolls, as he did at last year’s Festival of Dangerous Ideas, when arguing that children as young as six should be allowed to vote. After acknowledging that many people find the idea laughable, he turns the question around. “Why shouldn’t they vote?” he asks. “They’re people; they’re citizens; they have interests; they have preferences; there are things that they care about.” Children might make irrational, ill-informed decisions, they might follow their tribe unthinkingly, they might dismiss facts that challenge pre-existing beliefs, but, he points out, adults might too.

“You can’t generalise about children any more than you can generalise about adults,” Runciman says, noting that being well-informed isn’t a prerequisite for voting. Being capable is, and six-year-olds, he argues, are.

Runciman speaks from experience – he once spent a term in an English primary school talking to kids as young as six about politics. Treating them “like they were full citizens”, he arranged for them to participate in the kind of focus groups political parties run for adults. The professional facilitator who ran them said one was among the most inspiring focus group sessions she’d ever been part of.

I’m not convinced children as young as six should be allowed to vote; I am convinced that when we assume we can’t learn from, or socialise with, or befriend them – when we widen the generational divide instead of closing it – we do ourselves and our society a disservice.

I was grateful, and I’m grateful still, that the friend who drew my attention to my parenting mistake didn’t let concern about how it might come across stop him from speaking his mind. Frank honesty is a quality some associate with children. Either way, it’s one that I admire.

I admired his persistence too – despite all those puzzled looks from kids, he’s persevered.

That persistence has paid off. It’s taken months, it’s taken years, but now some children run to him, or look for him at social gatherings. Now some consider him a friend.

For more, tune into David Runciman’s FODI talk, Votes for 6 year olds:

BY Emma Wilkins

Emma Wilkins is a journalist and freelance writer with a particular interest in exploring meaning and value through the lenses of literature and life. You can find her at: https://emmahwilkins.com/

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Science + Technology

Big tech’s Trojan Horse to win your trust

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Anthem outrage reveals Australia’s spiritual shortcomings

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Freedom and disagreement: How we move forward

Opinion + Analysis

Climate + Environment, Health + Wellbeing, Society + Culture

Melbourne Cup: The Ethical Form Guide

A critical thinker’s guide to voting

A critical thinker’s guide to voting

Opinion + AnalysisPolitics + Human RightsRelationships

BY Dr Luke Zaphir 14 APR 2025

In Australia, we have no formalised method of teaching people about politics, voting and elections. Most people vote the same way as their parents in their first elections, and won’t receive any more education beyond how-to-vote cards and electoral ads.

People under the age of 25 make up about 10% of all voters – that’s about ten thousand per electorate. They’re the most underrepresented group in political discourse and in elections. Not only that but young people will have to live with the consequences of these policies far longer than any other demographic.

Given that some elections come down to only a few hundred votes, the way we vote really does matter.

Our votes matter beyond the current election – they affect future elections too. The Australian Electoral Commission provides funding for every candidate or group that receives more than 4% of first preference votes. This means that even small groups can become big factors, influencing future elections and swaying the balance of power in parliament.

Finally, democracy works because it’s about communicating our needs and visions of the future. The major parties pay attention to how and why people vote. The Labor and Liberal parties have issues that they care about but others they overlook. A vote can shift the way the policy platforms of the major parties to discuss the issues we care about.

Here is a practical guide to critically think about your vote.

Step 1: Ignore the hype

Political parties are really good at demonising each other. They’ll accuse each other of being craven, lying, baby eating monsters. None of this is useful information. Almost every piece of political messaging from every party is propaganda designed to get your vote. They’ll frame the issues in terms of economics, jobs, the environment or tradition. This anchors our thinking in a way that is unhelpful for choosing a candidate, making it difficult to consider nuance and complexity.

Step 2: Value democratic integrity

Our democracy cannot function if our representatives are known liars, are demonstrably corrupt, or engage in unscrupulous mudslinging against other candidates. Everyone believes they are morally correct but if the candidate spends their time hurling insults, they’re actively toxic to our democracy. If the candidate is willing to say or do anything to get elected, they can’t be trusted to further the public good and should come last on the ballot.

Our democracy only functions if its processes are open, fair and honest. Recent changes to the ways political candidates are allowed to fundraise means that it may be easier for incumbents to stay in power, and harder for newcomers to challenge them. It’s worth looking into whether your member of parliament supported these changes, or aims for a level playing field.

Step 3: Think about your values

The most fundamental part of knowing who to vote for is knowing what your values are. There are an endless number of beliefs that we might hold. We might believe in universalism and benevolence (welfare for all, tolerance and understanding), which lead to policies like a universal basic income, investment in public broadcasters like the ABC, and increasing foreign aid. Values such as self-direction and achievement are more important to us (pursuing and gaining personal success) lead to policies that minimise taxation and deregulation. Voting against same-sex marriage or changes to the constitution to include First Peoples are examples of valuing tradition, whereas policies that block foreign investment or advocate turning back asylum seeker boats prioritise security.

There’s no such thing as ‘having bad values’, but it’s important to know what we believe, why we believe it, and prioritise these when it comes to elections. Ask yourself how important each of your principles and goals are in turn, and if your vote will move you further towards them.

Step 4: Think about what you’d like for the country

Now that you understand your values, think about how they inform the kind of country you want Australia to become. Political parties offer massive packages of policies containing aspects we agree with or may not like. Vote compasses can be useful at this point in this task – they have specific policy directions that allow us to precisely target what we would want to achieve in the country. This is an important step because we might agree with a party’s stated views but if their policies don’t match up, we’re not going to be represented well.

It’s common to agree with only part of a party’s political package. This is why we need to learn about all the candidates’ parties, their aims, and which best aligns with our own views. Preferential voting is a way of creating an order of best fit – with your number 1 preference going to the party that most aligns with your views, and each subsequent preference being the next best fit. The party that least represents your views should get your last preference.

Step 5: Learn about the parties

Labor and the Liberals are the most powerful and oldest parties in Australia. They aren’t exactly the same platforms as they once were, which is why second hand information from others may be out of date. The Greens are also a significant party and often hold the balance of power in the Legislative Assembly. There are many other parties that will be in your division and it’s worth looking into what they value and what their aim is specifically. There are many parties that focus on single issues that are important to them.

Step 6: Discover the candidates’ credentials and goals

The Australian Electoral Commission provides information about all currently enrolled candidates. Additionally, blogs like The Tally Room track candidates for each division and provide links to all of their personal websites.

A person’s qualifications and work history will tell us a bit about who someone is. Do they own a business? Ran a not-for-profit? Have they been a teacher or academic or front line retail worker? Have they been bankrupt? This is useful for telling us what kind of person we’re voting for and how they think.

Another important aspect is how clearly they’ve articulated their goals. Every party is in favour of good economic management, green technology and low unemployment figures. What matters is which they prioritise given the current context. It’s also worth considering what they plan in the long term – do they have a vision for Australia in 20 years? In 50? A party that only sees the future one electoral cycle ahead is one that will make short sighted decisions.

Lastly, if they can’t concisely say that they aim to enact a specific law or to increase a certain tax, we have reason to question their competence. A candidate can talk about the value of freedom all they want – without a stated goal, they either haven’t thought about it or they’re dog whistling.

Step 7: Judge the incumbent’s track record

The member of parliament for your division has a higher burden for gaining re-election because they have to defend their record. What have they done so far? What have they accomplished? How have they voted in the House of Representatives or Senate? Hansard is the official record of parliamentary speeches and votes. They Vote for You is a not-for-profit independent non-partisan organisation which tracks how the current member of parliament has voted (from Hansard). This includes their attendance (how often they do their job), and what they vote consistently for and against. This is particularly useful for us if we care about a specific issue – we can discover if the sitting member supports or votes against it in parliament.

A final thought

There are no wrong choices except those which are made with inaccurate information. This guide will take less than an hour and that’s not much to be conscientious about your vote once every three years. Democracy isn’t just about voting. It is in our civil discourse itself and how we share our perspectives.

Think about whether the status quo should stay the same or change based on your values and goals, then vote for the candidate that you believe represents your view. When you talk to people about who you’re voting for, be curious about their values and their perspective. From these together, you’ll have a thoughtful and well considered perspective.

This article has been updated since its original publication in 2022. Image by AEC photo.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Can we celebrate Anzac Day without glorifying war?

Explainer

Relationships, Society + Culture

Ethics Explainer: Beauty

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

We need to talk about ageism

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights, Society + Culture

Corruption, decency and probity advice

BY Dr Luke Zaphir

Luke is a researcher for the University of Queensland's Critical Thinking Project. He completed a PhD in philosophy in 2017, writing about non-electoral alternatives to democracy. Democracy without elections is a difficult goal to achieve though, requiring a much greater level of education from citizens and more deliberate forms of engagement. Thus he's also a practicing high school teacher in Queensland, where he teaches critical thinking and philosophy.

We shouldn’t assume bad intent from those we disagree with

We shouldn’t assume bad intent from those we disagree with

Opinion + AnalysisRelationships

BY Karina Morgan 7 APR 2025

Polling by John Hopkins University in the lead up to the 2024 US election found that nearly half of eligible voters in the US believe that those in the opposing political party are “downright evil”.

This is likely an illustration of an attribution bias called “Motive Attribution Asymmetry”– one group’s belief that their rivals are motivated by emotions opposite to their own. To put it in simple terms: if I believe x and I believe I am a good person with good intentions, people who believe y must be evil.

Motive Attribution Asymmetry was coined in 2014, after five cross cultural studies identified a fundamental bias driving ‘seemingly intractable human conflict’. What these researchers found was that in political or ethno-religious intergroup conflict, adversaries tended to attribute aggression from their own side to ingroup love, and aggression from the opposing group to out-group hate.

A key word in the findings here is ‘intractable’. Can you actively listen, or seek to empathise, when you believe that your opponent’s beliefs and actions are grounded in hate? You’ve already, possibly unconsciously, assumed their intrinsic motivation is evil – and it’s an easy hop, skip and jump to dehumanisation from there.

In a New York Times column, Harvard Professor and Social Scientist, Arthur Brooks writes that motivation attribution asymmetry leads to contempt, which he says “is a noxious brew of anger and disgust, and not just contempt for other people’s ideas but also for other people”.

When we move from disagreeing, or even feeling contempt toward an idea, to contempt toward the whole person, we lose our humanity.

In the words of the 19th-century pessimistic philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer, contempt “is the unsullied conviction of the worthlessness of another.”

Let’s consider this in the larger scheme of human discourse.

It’s why it can be so hard for two people to hold a conversation who have deeply opposing views, because they don’t trust, or already have a subconscious bias toward, each other’s motives.

Has your dinner table ever erupted in conflict over opposing ideas? Or have you left a conversation feeling disgusted, wondering how, or if, you can continue the relationship with someone who supports something you’re vehemently against?

In these conversations, look for how you or the people around you respond to opposing ideas. Sarcasm, eye-rolling, sneering or hostile humor are all indicators of contempt according to renowned social psychologist John Gottman.

Schopenhauer also submits that if real contempt is shown, “it will be met with the most truculent hatred; for the despised person is not in a position to fight contempt with its own weapons.” Or, as we heard from the 2014 study, intractable conflict will ensue.

So what’s the panacea to motive attribution asymmetry and its toxic bedfellow of contempt? One person who has overcome her own biases is two-time Festival of Dangerous Ideas (FODI) alum Meagan Phelps-Roper.

A former born-and-raised, active member of the Westboro Baptist Church, Phelps-Roper left religious extremism behind after she encountered curiosity and a willingness to ask questions from some Twitter users. Their open-minded questions led her to ask her own, and ultimately choose a different path. Later, it was her appearance on stage at FODI 2018 that caused her to reflect on the importance of having difficult conversations in the public sphere.

Phelps-Roper’s tips for engaging with disagreement begin with a very important piece of advice: don’t assume bad intent. Assuming ill motive, she says, immediately cuts us off from accessing empathy, and prevents us from trying to understand why someone does or believes differently. It also blocks any potential for real dialogue. Her other tips include asking questions, staying calm, and articulating your own argument.

In her FODI 2024 session, The Witch Trials, alongside podcast producer Andy Mills, Phelps-Roper shared six prompts she asks herself in order to keep her own bias in check:

- Are you capable of entertaining real doubt about your beliefs? Or are you operating from a position of certainty?

- Can you articulate the evidence you would need to see in order to change your position? Or is your perspective unfalsifiable?

- Can you articulate your opponent’s perspective in a way that they recognise? Or are you straw-manning?

- Are you attacking ideas or attacking the people who hold them?

- Are you willing to cut off close relationships with people who disagree with you, particularly over small points of contention?

- Are you willing to use extraordinary means against people who disagree with you?

If, she says, the answer to any of these is yes, she knows she’s embarking on a ‘bad path’.

Perhaps next time you sit down alongside that opinionated uncle or sibling and the conversation takes a slippery turn, pause for a moment, then engage back with curiosity and the assumption of good – or even just neutral – intent.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships, Society + Culture

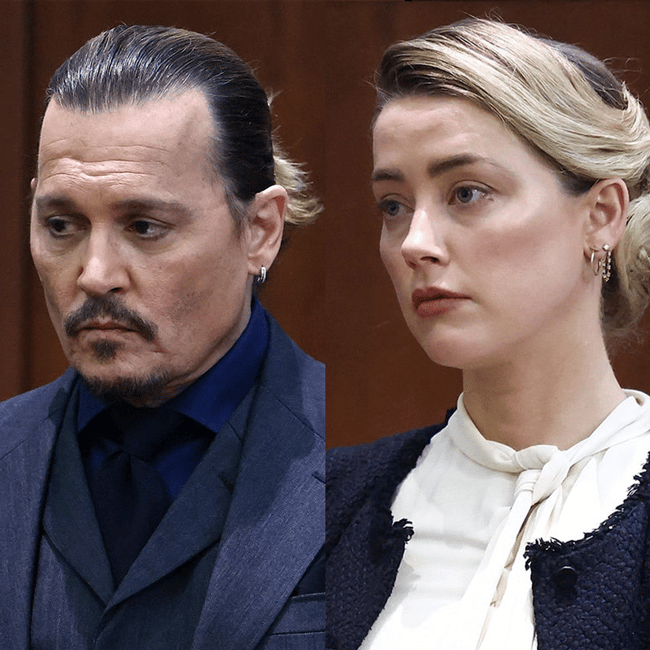

You won’t be able to tell whether Depp or Heard are lying by watching their faces

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Akrasia

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships

The twin foundations of leadership

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships

Workplace romances, dead or just hidden from view?

BY Karina Morgan

Karina is a communications specialist, avid hiker and volunteer primary ethics teacher, with a penchant for the written word.

5 lessons I’ve learnt from teaching Primary Ethics

5 lessons I’ve learnt from teaching Primary Ethics

Opinion + AnalysisRelationships

BY Karina Morgan 18 FEB 2025

Each week, for 45 minutes, I sit down with a group of year two students and discuss ethics.

We’ll tackle an ethical concept or dilemma, typically in the form of a story, with questions designed to draw out deep discussion amongst the class.

The Ethics Centre established Primary Ethics as an independent not-for-profit in 2011, tasked with developing a curriculum and recruiting volunteers to run weekly ethics classes as an alternative in the scripture timeslot in public schools. They now deliver lessons to 45,000 children in 500 schools from kindergarten to year eight.

Classes are led by trained volunteers, who act as impartial facilitators. Our role is to model active listening and ask questions that build critical thinking skills and encourage collaborative learning.

For me, it feels like the most important gift I can give to the next generation. And, if I’m honest, I find I am learning in each and every class right alongside them.

Here are five lessons I’ve learned from teaching Primary Ethics this year:

1. Curiosity is the gateway to critical thinking.

Embracing curiosity is how we learn; it’s the driving force for growth, discovery, and innovation. The innate curiosity in children is a vital foundation for developing skills like critical thinking, empathy and thoughtful decision-making.

You see a curious mind doesn’t accept information at face value; it probes deeper, asking why, how, and what if? It fuels the critical examination of ideas, helps us to identify biases, to sort fact from fiction, and to consider situations from multiple perspectives.

I admire the unbridled curiosity of the students I teach. It’s contagious. As adults, we can get stuck in our routines and belief systems. We accept the status quo and stop exploring what’s possible.

2. There is power in saying “I don’t know”.

One of the most powerful moments this year came when a student asked a question I couldn’t answer. I took a breath and said, “I don’t know – what do other students think?”

And just like that, the room lit up. I had given the students permission to be knowledge holders and modelled the open-minded growth mindset we want to cultivate through ethics lessons. Since then I have witnessed so much more willingness to have a go from everyone in the room.

It turns out there’s a kind of magic in admitting you don’t have all the answers. Teaching ethics is not about being an authority; it’s about being a partner in figuring things out. Admitting you don’t know doesn’t make you weaker – it opens the door for connection and learning.

3. To disagree respectfully, we need to be open to learning from each other.

Nine-year-olds are full of opinions. But what also stands out to me is how open they are to new points of view, to listen to each other, even when they disagree. Recently, a student in my class said she disagreed with the person sitting next to her. That student smiled, said, ‘that’s ok’, and leaned into hearing her peer explain why. Imagine if we could cultivate that across the political divide?

Kids don’t assume the worst in someone who thinks differently – they assume they are trying their best, just as they themselves are. Watching them address and debate differing points of view without engaging in personal attack or any attempt to discredit each other is a beautiful reminder that respectful disagreement starts with empathy, assuming good intentions and willingness to learn from each other.

4. Psychological safety empowers new ideas, and even changes minds.

There’s a sense of psychological safety built through collaborative inquiry, because everyone’s ideas and questions are valid here. The kids thrive in the freedom it offers to explore, build on each other’s ideas, and even to change their minds.

When I started teaching this class two years ago, everyone was itching to have their turn, and to get the answer ‘right’. Now they have begun to really listen to each other – not just to respond, but to understand each other’s opinions.

This year there’s been instances where students have discussed feeling conflicted over a question, proposed merit across differing sides of a debate, and even changed their mind after listening to other points of view.

It’s a powerful reminder of how active listening can transform conversations. Making someone feel heard deepens trust, fosters empathy, and makes room for challenging conversations. It isn’t just a tool for learning; it’s a tool for connection.

5. Ethics in education can establish a resiliency for life.

Resilience, I fear, is a word that’s lost some of its charm for a lot of adults. Through ethics lessons I’ve been reminded that resilience isn’t the nefarious push through mentality or the ability to bounce back from a setback. It can also be staying engaged with challenging situations, even when the answers are messy or unclear. It’s regulating emotions, processing stress and being adaptable to change.

Ethics lessons are about grappling with tough questions, sometimes without any resolution. Nine-year-olds handle this better than you’d think, and certainly better than a lot of adults do. When there’s no clear answer, they meet the discomfort of uncertainty with curiosity and creative thinking.

Volunteer to become a Primary Ethics teacher and you’ll be helping children develop important skills for life. Find out more here.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

But how do you know? Hijack and the ethics of risk

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships, Science + Technology

Philosophically thinking through COVID-19

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

If women won the battle of the sexes, who wins the war?

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Violent porn and feminism

BY Karina Morgan

Karina is a communications specialist, avid hiker and volunteer primary ethics teacher, with a penchant for the written word.

Discomfort isn’t dangerous, but avoiding it could be

Discomfort isn’t dangerous, but avoiding it could be

Opinion + AnalysisSociety + CultureRelationships

BY Emma Wilkins 7 JAN 2025

If I were a reviewer at a writers’ festival and I spotted an author whose work I’d praised – but also criticised – I’d be tempted to look the other way.

But, far from avoiding Christos Tsiolkas at last year’s Canberra Writers’ Festival, literary critic and Festival Artistic Director, Beejay Silcox chose to share the stage with him.

When asked if she felt uncomfortable, Silcox said that because she felt she’d done her job well – reflecting on the work, dealing with it on its own terms, choosing her words carefully – she didn’t. If she couldn’t be honest about “the loveliest man in Australian literature”, she didn’t deserve her job.

She did, however, describe that job as “inherently uncomfortable”. It’s the reason people often call her “brave”. But Silcox doesn’t share their view. “If what I do counts for bravery in our culture, we are f*cked,” she told the audience. “I know what bravery looks like; I’ve seen brave people. I’m just being honest.”

Point taken. There’s a difference between being honest and being brave. Honesty might require bravery, but the words aren’t interchangeable. If we use words like “bravery” too readily, we broaden its definition and reduce its potency.

It was the expanded application of certain words, that led psychology professor Nick Haslam to coin the term “concept creep”. More than a decade ago, he started noticing the widespread adoption of certain psychological terms in non-clinical settings was broadening people’s conceptions of harm. In a recent ABC interview, he said more expansive definitions of terms like “abuse” and “bullying” have had clear advantages, such as making it easier to call out bad behaviour. But mistakenly framing an unpleasant experience as “trauma”, or speaking as if ordinary worries constitute anxiety disorders, can make people feel, and become, more fragile.

This year, Australia introduced legislation that gives employers a positive duty to protect workers from psychosocial hazards and risks. It’s right to recognise that psychosocial harm can be as damaging as physical harm, but it’s important to understand what psychological safety isn’t. As Harvard business school professor Amy Edmondson stresses, it isn’t “feeling comfortable all the time”. It isn’t simply safety from discomfort, it’s safety to engage in conversations that might be uncomfortable. A manager should be able to gently raise an issue with an employee that might make them feel uncomfortable, without being accused of deliberately “violating” their safety – and vice versa. But I’ve heard managers, and educators, express concern that even well-intentioned, carefully delivered, feedback, could be perceived as an attack.

We can be uncomfortable and still be safe. If we lose this distinction, if managers in workplaces and teachers in schools, parents in the home and politicians in parliament, feel obliged to keep everyone comfortable all the time, we’ll end up in dangerous territory. We’ll be less able to express our views, and less able to hear each other out, less able to learn from each other.

Honest, measured, criticism plays an important role in society. We need to value it; even (perhaps especially) if it’s hard to hear. We also need to recognise that avoiding exposure to any and all discomfort will only heighten the sensation; and consider the merit, case by case, of facing it.

So, what might this look like?

C.S Lewis said that if you look for truth, “you may find comfort in the end”, but if you look for comfort, “you will not get either comfort or truth”. He wasn’t talking about performance reviews or reports or assignments, but the principle is still relevant.

If I seek the truth about my performance at work, I might find ways to improve it, gaining competence and confidence. A by-product will be a broader comfort zone. If I only want to hear praise, I can look for people who will only give it or find ways to only get it. I can avoid trying if I think I’ll fail, or I can start cheating to ensure success. In the short-term I might feel better, but over time, I’ll be progressively worse off.

We need more expansive conversations – more discomfort which, through exposure, will expand our comfort zones and increase our resilience. Silcox talks about how we need fewer “gatekeepers” – those who close doors and shut down important conversations – and more “locksmiths” – those who open them.

We can start by considering the way we speak, and think, and act. Are we using words that make others more cautious, risk averse, fearful, fragile, than they need to be? What about when talking to ourselves? Are we so focussed on staying safe from risk, that we forget about how many risks are safe to take? With this in mind, we can resolve to sit with discomfort, to recognise the doors that it can open, that comfort can’t. We can welcome feedback, even ask for it; embrace challenges, even set them for ourselves; replace complete avoidance, with strategic exposure. And if we’re in positions of authority, we can give those we oversee genuine permission to try and fail and try again.

It’s natural to avoid discomfort. But if we continually avoid what’s hard, it will feel harder still. If we want to talk about what matters and do it well; exercise moral courage; make a difference in the world – we’ll have to expand our comfort zones, not narrow them. We’ll have to take some risks. But do you know what else is risky? Sitting still.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Lying

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture

What is all this content doing to us?

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture, Climate + Environment

Who’s to blame for overtourism?

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

CoronaVirus reveals our sinophobic underbelly

BY Emma Wilkins

Emma Wilkins is a journalist and freelance writer with a particular interest in exploring meaning and value through the lenses of literature and life. You can find her at: https://emmahwilkins.com/

Ask an ethicist: How do I get through Christmas without arguing with my family about politics?

Ask an ethicist: How do I get through Christmas without arguing with my family about politics?

Opinion + AnalysisRelationships

BY Tim Dean 19 DEC 2024

I love going home to see my family for Christmas. But over the past year I’ve noticed my uncle posting on Facebook about politics and conspiracy theories that are completely different to what I believe. I’m worried he might make an offensive quip about the news over dinner. How do I defend my point of view without it erupting into an argument?

Unlike most of the year, where we can comfortably reside within our own social bubbles, Christmas is when we’re thrust into the midst of that diverse range of personalities, generations and political persuasions that make up our extended family. This means we’re often faced with views we don’t normally encounter, and sometimes forced to defend our own views in the face of staunch opposition.

So, if you’re dreading the prospect of a stormy argument at the holiday dinner table, here are some tips for navigating the perilous territory of contentious topics and steering the conversation towards calmer waters.

Why conversations go bad

If humans were truth-seeking robots, then we’d welcome criticism of our views and thank others for showing that our beliefs are in error. But we’re not robots. We’re vulnerable social creatures, absorbing ideas and norms from our peers and those we admire, all while defending our identity and status from perceived attacks.

Compounding the complexity of how we form our beliefs and attitudes is that emotion often leads the way, with reason lagging behind, and we scramble to find arguments to support the way we feel. This means that many of the arguments we offer to support our views are actually not the cause of our belief, but the effect. They’re post-hoc rationalisations that we use to defend our underlying attitudes.

You can tell when someone is arguing using a post-hoc rationalisation, because if you surgically dismantle it, showing that it’s false, they still don’t change their mind. You might have knocked down one post-hoc rationalisation, but you haven’t challenged the actual reason they hold their attitude.

All this messy business of not being a robot means that disagreement about an issue where we hold strong feelings – and ethical questions are often the things we feel the most strongly about – can easily slip into conflict, where we rapidly find ourselves defending our turf and fighting back against threats to our identity and desperately trying to change the other person’s mind.

How to not spoil the dinner table conversation

The good news is that there are some techniques you can use to lower the temperature in contentious conversations, and possibly even walk away with a stronger relationship and some new perspectives to consider.

The first step is to stop trying to win! If you think about it, it’s strange that we even think that we can change someone’s mind in a single heated conversation. When was the last time such a conversation changed your mind? Instead, it takes a different kind of conversation – often multiple conversations – to encourage someone to adopt a different perspective, especially around topics where they already hold strong views.

So, when you hear someone state a view that you believe is wrong, try to resist doing the natural human thing of stating an opposite view. Doing so immediately locks the conversation in the Thunderdome, where two viewpoints enter, and only can survive. It’s even worse if the views battling it out are post-hoc rationalisations, because then you’re both just whiffing at ghosts.

Instead, pause. Take a deep breath. Then ask a question. And really listen to the answer. This does two important things. The first is that it actually gives you a fighting chance of understanding the detail of the other person’s view. We usually only get a chance to express a fragment of our full beliefs on a topic. And often others will fill in bit we leave unsaid with an uncharitable interpretation, sometimes even outright misrepresenting what we believe. Asking and listening allows them to fill in those gaps themselves.

The second thing that asking and listening does is arguably more important: it signals respect. Listening to someone is like giving them a gift (possibly an even more valuable one than they got out of the Secret Santa). It shows you actually care about what they think and that you want to know more. Sometimes, all people want is to get something off their chest, and giving them a chance to do so will cause them to temper their beliefs in the process, landing somewhere more reasonable.

The respect that listening generates becomes the bedrock of a good conversation about a contentious issue. It means they are more likely to want to listen to you in return, and it reduces the perception that their identity is under attack, so they might even be more willing to take your perspectives on board.

Story time

Once you’ve had a chance to listen to what they have to say (and hopefully had the chance to be listened to in return), then a next step can be to tell some stories that can shed light on your point of view.

You can talk about how you formed your belief, or share a perspective that you found surprising but persuasive. You can even invite them to share a story about how they came to their view, or ask if they know someone who has been affected by the issue you’re discussing. Techniques like this have been shown to humanise what can be otherwise abstract or dehumanised perspectives, grounding them in the real world and shifting the conversation away from stereotypes and glib generalisations.

If the conversation is getting heated at any point, there’s no shame in backing out or changing the subject. This is supposed to be a harmonious family gathering, after all. And relationships are fundamentally important to a good life, so it can sometimes be more important to preserve a relationship than it is to be right. Plus, reinforcing that relationship is precisely what is needed if you ever want to continue the conversation down the track and have them be receptive to your point of view.

Christmas dinner is not about changing minds. It’s about coming together as a family or a community to engage in ritual activities that are supposed to bring us together. At least, that’s the ideal. For many people, Christmas can be laced with tension, simmering resentments, power plays and drunken debates. While the techniques here won’t solve all those problems, they might help to lower the temperature, build some stronger relationships, and hopefully allow you to enjoy your post-meal nap in some peace.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Stoicism

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Philosophy must (and can) thrive outside universities

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships, Society + Culture

Extending the education pathway

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

5 lessons I’ve learnt from teaching Primary Ethics

BY Tim Dean

Dr Tim Dean is a public philosopher, speaker and writer. He is Philosopher in Residence and Manos Chair in Ethics at The Ethics Centre.

Community is hard, isolation is harder

Community is hard, isolation is harder

Opinion + AnalysisRelationshipsSociety + Culture

BY Daniel Finlay 28 NOV 2024

Yesterday I crossed the street to avoid talking to an acquaintance.

Not because I don’t like them. Not because I was in a rush. But because I often feel a deep aversion to participating in small pleasantries or having to socialise when I’m mentally unprepared.

This is only one in a list of anti-social tendencies I’ve noticed myself developing during my adult life.

A lot of them seem more mundane than crossing the street, too. When’s the last time you took off your headphones and casually spoke to a stranger on the train or at the shops? Have you gotten to you know your neighbours or your barista? If a small accident happens in public, do you shy away or pretend you didn’t notice?

Community and Individualism

Recently on TikTok, something that’s caught my attention is a renewed focus on the benefits of and desire for community and how that conflicts with our increasingly individualistic mindsets.

Friction between these two ideas seems unavoidable: community involves a focus on the people around you, and individualism involves a focus on yourself. Go too far in either direction and you’ll inevitably begin to neglect the other.

In his video “This is one of my hills”, creator NotWildlin responds to the view held by some that we don’t owe strangers pleasantries. His gripe isn’t necessarily that we do owe strangers anything, but rather that this attitude appeared to be coming from people who were simultaneously frustrated with the lack of opportunity for community around them. Specifically, they had been advocating for more third places.

Coined by the sociologist Ray Oldenburg in his book The Great Good Place, third places are communal public spaces where casual conversation is the primary (but not necessarily only) activity, and the space is neutral, welcoming, cozy, accessible, playful and homely. Importantly, these spaces are separate from the home, our first place, and from work or study, our second place.

These are places where it’s encouraged to interact with strangers, with a sense of openness for conversation and general interaction with local community.

So, NotWildlin’s argument is this:

If you are the kind of person who laments a decline of local community, who wants to build social capital through things like third places, then how can you also justify being habitually anti-social?

Instead of thinking about pro-social habits as something we owe, we should think about them as something we want to develop in the name of community.

This argument honestly rocked me a little, as someone who is becoming increasingly community-minded, while also holding desperately onto my inalienable right to be left alone.

However, it does seem to me, as an extension of NotWildlin’s point, that a focus on third places is a misprioritisation. On a systemic level, yes, there could be more local government support in creating welcoming public spaces to encourage community. On the other hand, many areas in populous Australian cities do have third places that go underutilised. How many younger people do you know that use libraries, public gardens or other community centres? The deeper problem in my estimation is social and cultural.

Keeping the (inner) peace

Once we leave the education system, many people become creatures of habit, and that unfortunately can extend to the way we view relationships and interact with others. We’re less open to even fleeting interactions with strangers, we might be content with our small circle of friends and unenthusiastic about adding to the noise. We have our routines and any effort outside of them can feel like a small burden.

Unfortunately, that spells disaster for building community. Around the same time as NotWildlin, an Australian creator Jordan Stacey posted a video about the relationship between routine and community. She unpacks the idea that community requires compromise in ways that threaten our often highly sought after bubbles of routine, and too often community is neglected in favour of maintaining these routines.

Stacey talks through this with two main points. Firstly, routine is only a symptom of a broader desire for comfort and convenience. The reason that someone might struggle to accept a spontaneous invitation in lieu of their quiet night in watching tv (for example) is the same reason many people avoid interactions with strangers. And to some extent, this seems obvious, natural and maybe even justified. Why would we want to be uncomfortable or inconvenienced?

But arguably, this is a case of wanting to have your cake and eat it too – at least for those of us who envision a time in the future where we’re surrounded by supportive relationships within thriving communities – because as a reciprocal support network, community necessitates intermittent inconvenience.

If we want to develop and be surrounded by relationships in which we can find support, we also have to be willing to forgo some of our solitude and peace and embrace the inconvenience of being pro-social.

Stacey’s second point is that we live in a world that almost necessitates this level of comfort-protection; that causes us to frame these aspects of community as inconveniences rather than incidental aspects of functioning and fulfilling relationships.

“If you’re working 40 hours a week – a nine to five – the only way, for a lot of people, that this is actually maintainable is through a hefty routine.

The systems we live under directly limit our time and put pressure on our leisure. Our routines often block out weeknights to relax and recover and relegate the majority of our social time to the weekend, creating a sense of isolation throughout the week.

It is also, I would argue, the same inner-peacekeeping measure that motivates our aversion to public interactions. Talking to strangers on our commute or in the lift is a similar disruption to our routines – to the books or podcasts or music that get us from point A to point B without having to cast our attention to the people around us.

Creating Community

All this is not to say that we need to start making forced conversation with strangers. As I write, I’m sitting on a quiet train and would frankly be annoyed if I was interrupted by an overly outgoing commuter. And that’s okay, sometimes.

What I think we should take from this discourse, though, is a readiness to confront our own anti-social dispositions when we reflect that we’re consistently prioritising routine or comfort over building relationships.

While we might dream of a world in which we’re surrounded by supportive relationships and vibrant communities, we’re much less conscious of the personal cost of that dream. The reality is, community doesn’t materialise from thin air – it’s built, moment by moment, through countless small interactions and shared experiences. And yes, those moments often come at the expense of our personal comfort and carefully curated routines.

These compromises aren’t things to shy away from, but reminders that meaningful relationships and thriving neighbourhoods are more than just social policy or urban planning – they’re about us. About stepping out of our bubbles. About choosing to inconvenience ourselves in small, deliberate ways that foster connection.

Maybe the next time we feel the urge to shrink into ourselves, we can choose differently, because community isn’t just something we want—it’s something we create. And creating it means showing up, no matter how uncomfortable it feels in the moment.

The question isn’t whether we owe strangers pleasantries – it’s whether we’re willing to invest in the world we want to live in.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Society + Culture

A win for The Ethics Centre

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

What does love look like? The genocidal “romance” of Killers of the Flower Moon

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

It’s time to increase racial literacy within our organisations

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Science + Technology

Big tech’s Trojan Horse to win your trust

BY Daniel Finlay

Daniel is a philosopher, writer and editor. He works at The Ethics Centre as Youth Engagement Coordinator, supporting and developing the futures of young Australians through exposure to ethics.

What exotic pets teach us about the troubling side of human nature

What exotic pets teach us about the troubling side of human nature

Opinion + AnalysisRelationships

BY Joseph Earp 21 NOV 2024

On February 16, 2009, local police in Stamford, Connecticut received a highly unusual, and deeply horrifying 911 call – Sandra Herold, her voice hysterical, told them that her pet chimp, Travis, had attacked and was eating her friend. In the background of the call, along with the screams of the friend, police could hear the hollering of an enraged primate.

Sandra had purchased Travis over a decade prior. Their relationship was extremely, perhaps unnaturally close – she raised him as a human child, and after her own daughter died, Travis became her everything. Travis, who showed high levels of intelligence, ate with her at the dinner table. Each night, they slept side by side in the same bed.

There has been much speculation as to what flipped Travis into a rage. Sandra’s friend, the victim of his attack, was holding his favourite toy when he mauled her – an Elmo doll. Perhaps it was an instance of territorial aggression. Perhaps it was his unhealthy lifestyle, or the drugs that Sandra sometimes gave him; she had mixed Xanax into his tea, just before the attack. Regardless, the attack raises questions about the ethics of owning exotic pets – and what exactly makes them different to domesticated animals.

Animal ownership: Rights and wrongs

We live in a culture increasingly fascinated by the ethics of owning exotic pets. The pandemic-era Netflix smash hit Tiger King and the recent series Chimp Crazy take an outrageous look at the often eccentric people who choose to own lions, tigers, and primates. More often than not, these investigations into exotic pet ownership show the dark side of the industry – Joe Exotic of Tiger King fame was repeatedly accused of abusing his animals.

Private owners of exotic animals frequently commit clear ethical wrongs. “Many private owners try to change the nature of the animals by … mutilating them, or beating/electrocuting them into submission,” writes animal welfare expert Bobbi Brink. There is a fundamental attitude towards the animal that underpins these harms. Namely, the animal is being treated and defined wholly by its relationship to human beings, and what they can do for us. It becomes an object that owners can do what they wish with. Ownership of this type transforms a living being into what philosopher Immanuel Kant described as a “means” rather than an “end” – it is indistinguishable from property.

This is, in fact, the argument made by philosopher Gary L. Francione against all forms of pet ownership. Francione argues that there is no way to not see your pet dog as anything other than property – you control it, own it, reduce to it to a mere object. “As a practical matter, there is simply no way to have an institution of ‘pet’ ownership that is consistent with a sound theory of animal rights,” Francione writes. “‘Pets’ are property and, as such, their valuation will ultimately be a matter of what their ‘owners’ decide.” Elsewhere, writer Karen Dawn notes that solitary confinement is used to punish humans – according to her, for pack animals like dogs, life without others of their kind can arguably be considered solitary confinement.

However, there is a mutually beneficial nature to some forms of pet ownership. There is much to suggest that human evolution was shaped and moulded by our relationship with dogs – there is a mutual appreciation that goes both ways. We give them things, and they give us things back. This in turn builds an emotional connection that can give both humans and pets lives worth living. At least, some forms of pets.

The allure of power

The ownership of exotic animals is troubling because of the lopsided power dynamics at play. The mutual beneficence in the case of dogs simply does not apply when it comes to lions or chimps. They do not gain anything from being taken from their homes, locked away, and having their needs systematically and brutally unmet. Travis the chimp might have eventually committed an act of brutality – but his life before that point was filled with what philosopher Michel Foucault would describe as diffused, rather than acute, forms of brutality. It was the brutality of being separated from his species and his needs.

The question remains, then – why do people want to own exotic animals? What is the appeal? And what does that say about human nature?

Exotic animals represent the unknown; the other; the distinct. The drive of taking the other, “dominating” it and making it our own, is what philosopher Nietzsche called “the will to power.” According to Nietzsche, the dynamics of those who take, and those who are taken from, exist in all things – it makes sense they would also exist in our relationships with exotic pets.

There is some sense of perceived glory in taking a wild creature and bending it to your will, and often, unable to cater to their complicated needs, owners tend to restrict or harm exotic animals in some way.

This kind of domination is about the success of one way of living; proving the excellence of the recognisable, by making the unrecognisable more like it.

One of our most admirable traits as a species is our curiosity. Being interested in exotic animals, and in pets, speaks to that curiosity. We are drawn to what makes them tick. That in itself is not a problem. But we must ensure that our relationship is one defined by that curiosity; to that openness to a creature, and all that it wants and needs. In short – we don’t need to change the nature of the other, or what is different to us. We need to respect it.

Image: Tiger King, Netflix

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

The tyranny of righteous indignation

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Come join the Circle of Chairs

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

Meet Josh, our new Fellow asking the practical philosophical questions

Big thinker

Relationships

Big Thinkers: Laozi and Zhuangzi

BY Joseph Earp

Joseph Earp is a poet, journalist and philosophy student. He is currently undertaking his PhD at the University of Sydney, studying the work of David Hume.

The ethics of friendships: Are our values reflected in the people we spend time with?

The ethics of friendships: Are our values reflected in the people we spend time with?

Opinion + AnalysisRelationships

BY Anna Goodman 14 NOV 2024

Some psychologists believe that we become the average of the people we spend the most time with. However, this can make things complicated for our own morals, ethics, and values.

In the middle of 2020, Nobel Peace Prize recipient Malala Yousafzai was harassed on Twitter for endorsing her conservative friend at Oxford University. It made headlines around the world, with thousands of people commenting on who they felt they could and couldn’t be friends with out of principle.

While friendships often transcend differences of opinion, most people have limits on what values and beliefs they will tolerate in the people they spend time with. It’s important to ask ourselves: does being friends with someone mean agreeing with all their values and beliefs? Or can we be friends with someone we disagree with?

There is more to friendship than simply sharing values and beliefs

When we enter into a friendship, we are agreeing to a set of duties and expectations of what it means to be a good friend. These duties can involve providing support during difficult times, celebrating accomplishments, being caring and empathetic, and so on.

However, it’s unlikely we’ll have friends who we agree with 100% of the time. This could mean disagreeing with a choice they made, or realising that you have differing values about something. It is perfectly reasonable to disagree with a friend or hold an opposing view, and not be hypocritical in your own beliefs.

It’s important to interrogate, though, what this means for us. When Malala was harassed online for having a friend with different political views, it wasn’t because she herself expressed those views. Rather, it was because she supported a friend with different views, and that support supposedly had to have indicated something about her own values and beliefs.

Friendships, however, are so much more than shared values. Having people in our lives with different values and opinions can broaden our perspective on the world, while also providing us with the opportunity to question the reasoning behind our own beliefs.

Even though there is more to a person than both their views and the views of their friends, it is naïve to claim that our friends’ values don’t have an impact on us.

So, there has to be a threshold of tolerance in what we are willing to understand in our friends’ values. The ethical dilemma we find ourselves in is where we draw the line.

There is no doubt that some categories of opinions and values shouldn’t be given the same airtime as others. One way we can discern this is by asking: what are the implications on others in expressing or acting on this belief?

Some beliefs predominantly impact the individual who holds them. Food preferences, opinions about what clothes look good, or what music sounds best are unlikely to have a significant effect on the people in this person’s life.

However, expressing or acting on other kinds of beliefs can have obvious, negative impacts on certain groups of people such as racist, sexist or homophobic rhetoric, disinformation, and hate speech. Understanding that expressing some kinds of beliefs has an impact on the broader community characterises the harm of unchecked intolerance.

When we overlook a friend’s more severe hateful or discriminatory belief, we can become complicit in allowing a belief that harms others to go unchecked.

Overlooking a hateful or discriminatory belief the same way that we might overlook a difference in taste or preference makes it seem like we are condoning, if not supporting, that belief. For example, if your friend was continuously espousing hate speech and you didn’t call them out on it, it doesn’t matter if you didn’t partake in hate speech yourself. By letting it slide because it’s a friend, the harm of expressing these values is still being done. Challenging and speaking out about that belief doesn’t mean that we are being a bad friend – in fact, it usually means the opposite.

One possible solution: deal breakers

Even though we can’t expect to have all the same values as our friends, we might expect that we have the same deal breakers as them. A deal breaker is something like a value or personality trait that will cause a person to back out of a relationship or agreement. For example, one of the things that might connect us to our friends is that we all have a deal breaker that we won’t tolerate someone who is rude or unkind to strangers. Having the same deal breakers means that we draw the same line in the sand of what we will and won’t tolerate, rather than ensuring that we agree on every single value.

The concept of a deal breaker can be helpful with ethical value differences in our friends, too. For example, it could be that we’re happy with different approaches to ethical decision making, as long as we both won’t tolerate anything that harms others unnecessarily. Instead of making sure we agree with our friends entirely, we’re making sure we’re on the same page about the “non-negotiable” values we have.

As with most ethical issues, the answer is rarely black and white. In this case, the line we draw with what values we tolerate in our friends can often fluctuate due to external factors, including mental health and personal context.

At the end of the day, being someone’s friend shouldn’t mean that you have to defend every single belief that they have. I would hope that my friends feel that they can challenge my beliefs, and that I can do the same for them. However, it is important that we think about the deal breakers we have and hold our friends accountable for how their beliefs impact the broader population, and be willing to look inward when they do the same for us.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Why learning to be a good friend matters

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

What’s the use in trying?

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships, Society + Culture

Extending the education pathway

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships