A framework for ethical AI

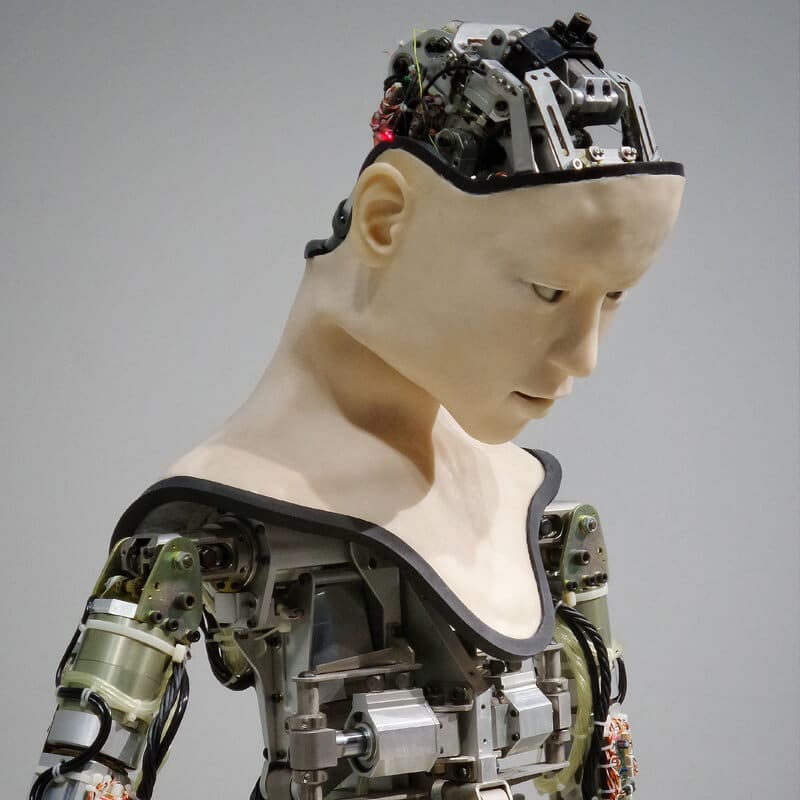

Artificial intelligence has untold potential to transform society for the better. It also has equal potential to cause untold harm. This is why it must be developed ethically.

Artificial intelligence is unlike any other technology humanity has developed. It will have a greater impact on society and the economy than fossil fuels, it’ll roll out faster than the internet and, at some stage, it’s likely to slip from our control and take charge of its own fate.

Unlike other technologies, AI – particularly artificial general intelligence (AGI) – is not the kind of thing that we can afford to release into the world and wait to see what happens before regulating it. That would be like genetically engineering a new virus and releasing it in the wild before knowing whether it infects people.

AI must be carefully designed with purpose, developed to be ethical and regulated responsibly. Ethics must be at the heart of this project, both in terms of how AI is developed and also how it operates.

This sentiment is the main reason why many of the world’s top AI researchers, business leaders and academics signed an open letter in March 2023 calling for “all AI labs to immediately pause for at least 6 months the training of AI systems more powerful than GPT-4”, in order to “jointly develop and implement a set of shared safety protocols for advanced AI design and development that are rigorously audited and overseen by independent outside experts”.

Some don’t think a pause goes far enough. Eliezer Yudkowsky, the lead researcher at the Machine Intelligence Research Institute has called for a complete, worldwide and indefinite moratorium on training new AI systems. He argued that the risks posed by unrestrained AI are so great that countries ought to be willing to use military action to enforce the moratorium.

It is probably impossible to enforce a pause on AI development without backing it with the threat of military action. Few nations or businesses will willingly risk falling behind in the race to commercialise AI. However, few governments are likely to be willing to go to war force them to pause.

While a pause is unlikely to happen, the ethical challenge facing humanity is that the pace of AI development is significantly faster than the pace at which we can deliberate and resolve ethical issues. The commercial and national security imperatives are also hastening the development and deployment of AI before safeguards have been put in place. The world now needs to move with urgency to put these safeguards in place.

Ethical by design

At the centre of ethics is the notion that we must take responsibility for how our actions impact the world, and we should direct our action in ways that are beneficent rather than harmful.

Likewise, if AI developers wish to be rewarded for the positive impact that AI will have on the world, such as by deriving a profit from the increased productivity afforded by the technology, then they must also accept responsibility for the negative impacts caused by AI. This is why it is in their interest (and ours) that they place ethics at the heart of AI development.

The Ethics Centre’s Ethical by Design framework can guide the development of any kind of technology to ensure it conforms to essential ethical standards.This framework should be used by those developing AI, by governments to guide AI regulation, and by the general public as a benchmark to assess whether AI conforms to the ethical standards they have every right to expect.

The framework includes eight principles:

Ought before can

This refers to the fact that just because we can do something, it doesn’t mean we should. Sometimes the most ethically responsible thing is to not do something.

If we have reasonable evidence that a particular AI technology poses an unacceptable risk, then we should cease development, or at least delay until we are confident that we can reduce or manage that risk.

We have precedent in this regard. There are bans in place around several technologies, such as human genetic modification or biological weapons that are either imposed by governments or self-imposed by researchers because they are aware they pose an unacceptable risk or would violate ethical values. There is nothing in principle stopping us from deciding to do likewise with certain AI technologies, such as those that allow the production of deep fakes, or fully autonomous AI agents.

Non-instrumentalism

Most people agree we should respect the intrinsic value of things like humans, sentient creatures, ecosystems or healthy communities, among other things, and not reduce them to mere ‘things’ to be used for the benefit of others.

So AI developers need to be mindful of how their technologies might appropriate human labour without offering compensation, as has been highlighted with some AI image generators that were trained on the work of practising artists. It also means acknowledging that job losses caused by AI have more than an economic impact and can injure the sense of meaning and purpose that people derive from their work.

If the benefits of AI come at the cost of things with intrinsic value, then we have good reason to change the way it operates or delay its rollout to ensure that the things we value can be preserved.

Self-determination

AI should give people more freedom, not less. It must be designed to operate transparently so individuals can understand how it works, how it will affect them, and then make good decisions about whether and how to use it.

Given the risk that AI could put millions of people out of work, reducing incomes and disempowering them while generating unprecedented profits for technology companies, those companies must be willing to allow governments to redistribute that new wealth fairly.

And if there is a possibility that AGI might use its own agency and power to contest ours, then the principle of self-determination suggests that we ought to delay its development until we can ensure that humans will not have their power of self-determination diminished.

Responsibility

By its nature, AI is wide-ranging in application and potent in its effects. This underscores the need for AI developers to anticipate and design for all possible use cases, even those that are not core to their vision.

Taking responsibility means developing it with an eye to reducing the possibility of these negative cases becoming a reality and mitigating against them when they’re inevitable.

Net benefit

There are few, if any, technologies that offer pure benefit without cost. Society has proven willing to adopt technologies that provide a net benefit as long as the costs are acknowledged and mitigated. One case study is the fossil fuel industry. The energy generated by fossil fuels has transformed society and improved the living conditions of billions of people worldwide. Yet once the public became aware of the cost that carbon emissions impose on the world via climate change, it demanded that emissions be reduced in order to bring the technology towards a point of net benefit over the long term.

Similarly, AI will likely offer tremendous benefits, and people might be willing to incur some high costs if the benefits are even greater. But this does not mean that AI developers can ignore the costs nor avoid taking responsibility for them.

An ethical approach means doing whatever they can to reduce the costs before they happen and mitigating them when they do, such as by working with governments to ensure there are sufficient technological safeguards against misuse and social safety nets in place should the costs rise.

Fairness

Many of the latest AI technologies have been trained on data created by humans, and they have absorbed the many biases built into that data. This has resulted in AI acting in ways that negatively discriminate against people of colour or those with disabilities. There is also a significant global disparity in access to AI and the benefits it offers. These are cases where the AI has failed the fairness test.

AI developers need to remain mindful of how their technologies might act unfairly and how the costs and benefits of AI might be distributed unfairly. Diversity and inclusion must be built into AI from the ground level through training data and methods, and AI must be continuously monitored to see if new biases emerge.

Accessibility

Given the potential benefits of AI, it must be made available to everyone, including those who might have greater barriers to access, such as those with disabilities, older populations, or people living with disadvantage or in poverty. AI has the potential to dramatically improve the lives of people in each of these categories, if it is made accessible to them.

Purpose

Purpose means being directed towards some goal or solving some problem. And that problem needs to be more than just making a profit. Many AI technologies have wide applications, and many of their uses have not even been discovered yet. But this does not mean that AI should be developed without a clear goal and simply unleased into the world to see what happens.

Purpose must be central to the development of ethical AI so that the technology is developed deliberately with human benefit in mind. Designing with purpose requires honesty and transparency at all stages, which allows people to assess whether the purpose is worthwhile and achieved ethically.

The road to ethical AI

We should continue to press for AI to be developed ethically. And if technology companies are reluctant to pay careful attention to ethics, then we should call on our governments to impose sensible regulations on them.

The goal is not to hinder AI but to ensure that it operates as intended and that the benefits flow on to the greatest possible number. AI could usher in a fourth industrial revolution. It would pay for us to make this one even more beneficial and less disruptive than the past three.

As a Knowledge Partner in the Responsible AI Network, The Ethics Centre helps provide vision and discussion about the opportunity presented by AI.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Science + Technology

With great power comes great responsibility – but will tech companies accept it?

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Science + Technology

The ethics of drug injecting rooms

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Science + Technology

We are being saturated by knowledge. How much is too much?

Big thinker

Science + Technology

Seven Influencers of Science Who Helped Change the World

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Thought experiment: "Chinese room" argument

Thought experiment: “Chinese room” argument

ExplainerScience + Technology

BY The Ethics Centre 10 MAR 2023

If a computer responds to questions in an intelligent way, does that mean it is genuinely intelligent?

Since its release to the public in November 2022, ChatGPT has taken the world by storm. Anyone can log in, ask a series of questions, and receive very detailed and reasonable responses.

Given the startling clarity of the responses, the fluidity of the language and the speed of the response, it is easy to assume that ChatGPT “understands” what it’s reporting back. The very language used by ChatGPT, and the way it types out each word individually, reinforces the feeling that we are “chatting” with another intelligent being.

But this raises the question of whether ChatGPT, or any other large language model (LLM) like it, is genuinely capable of “understanding” anything, at least in the way that humans do. This is where a thought experiment concocted in the 1980s becomes especially relevant today.

“The Chinese room”

Imagine you’re a monolingual native English speaker sitting in a small windowless room surrounded by filing cabinets with drawers filled with cards, each featuring one or more Chinese characters. You also have a book of detailed instructions written in English on how to manipulate those cards.

Given you’re a native English speaker with no understanding of Chinese, the only thing that will make sense to you will be the book of instructions.

Now imagine that someone outside the room slips a series of Chinese characters under the door. You look in the book and find instructions telling you what to do if you see that very series of characters. The instructions culminate by having you pick out another series of Chinese characters and slide them back under the door.

You have no idea what the characters mean but they make perfect sense to the native Chinese speaker on the outside. In fact, the series of characters they originally slid under the door formed a question and the characters you returned formed a perfectly reasonable response. To the native Chinese speaker outside, it looks, for all intents and purposes, like the person inside the room understands Chinese. Yet you have no such understanding.

This is the “Chinese room” thought experiment proposed by the philosopher John Searle in 1980 to challenge the idea that a computer that simply follows a program can have a genuine understanding of what it is saying. Because Searle was American, he chose Chinese for his thought experiment. But the experiment would equally apply to a monolingual Chinese speaker being given cards written in English or a Spanish speaker given cards written in Cherokee, and so on.

Functionalism and Strong AI

Philosophers have long debated what it means to have a mind that is capable of having mental states, like thoughts or feelings. One view that was particularly popular in the late 20th century was called “functionalism”.

Functionalism states that a mental state is not defined by how it’s produced, such as requiring that it must be the product of a brain in action. It is also not defined by what it feels like, such as requiring that pain have a particular unpleasant sensation. Instead, functionalism says that a mental state is defined by what it does.

This means that if something produces the same aversive response that pain does in us, even if it is done by a computer rather than a brain, then it is just as much a mental state as it is when a human experiences pain.

Functionalism is related to a view that Searle called “Strong AI”. This view says that if we produce a computer that behaves and responds to stimuli in exactly the same way that a human would, then we should consider that computer to have genuine mental states. “Weak AI”, on the other hand, simply claims that all such a computer is doing is simulating mental states.

Searle offered the Chinese room thought experiment to show that being able to answer a question intelligently is not sufficient to prove Strong AI. It could be that the computer is functionally proficient in speaking Chinese without actually understanding Chinese.

ChatGPT room

While the Chinese room remained a much-debated thought experiment in philosophy for over 40 years, today we can all see the experiment made real whenever we log into Chat GPT. Large language models like ChatGPT are the Chinese room argument made real. They are incredibly sophisticated versions of the filing cabinet, reflecting the corpus of text upon which they’re trained, and the instructions, representing the probabilities used to decide how to pick which character or word to display next.

So even if we feel that ChatGPT – or a future more capable LLM – understands what it’s saying, if we believe that the person in the Chinese room doesn’t understand Chinese, and that LLMs operate in much the same way as the Chinese room, then we must conclude that it doesn’t really understand what it’s saying.

This observation has relevance for ethical considerations as well. If we believe that genuine ethical action requires the actor to have certain mental states, like intentions or beliefs, or that ethics requires the individual to possess certain virtues, like integrity or honesty – then we might conclude that a LLM is incapable of being genuinely ethical if it lacks these things.

A LLM might still be able to express ethical statements and follow prescribed ethical guidelines imposed by its creators – as has been the case in the creators of ChatGPT limiting its responses around sensitive topics such as racism, violence and self-harm – but even if it looks like it has its own ethical beliefs and convictions, that could be an illusion similar to the Chinese room.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Science + Technology

Australia, we urgently need to talk about data ethics

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Science + Technology

Who’s to blame for Facebook’s news ban?

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Science + Technology

Big tech knows too much about us. Here’s why Australia is in the perfect position to change that

Opinion + Analysis

Science + Technology

License to misbehave: The ethics of virtual gaming

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

AI is not the real enemy of artists

AI is not the real enemy of artists

Opinion + AnalysisScience + TechnologySociety + Culture

BY Dr Tim Dean 2 FEB 2023

Artificial intelligence is threatening to put countless artists out of work. But the greatest threat to artists is not AI, it’s capitalism. And AI could be the remedy.

“Socrates taking a selfie, Instagram, shot outside the Parthenon, wearing a white toga, white beard, white hair, sunlit.” That’s all the AI image generator Stable Diffusion needed to create the cover image for this article.

But instead of using artificial intelligence, I could have hired a photographer or purchased an image from a stock library to adorn this article. In doing so, I would have funnelled money to a human, who might have spent it on something else created by another human. Instead, I used AI, and no money left my pocket to flow through the economy.

And therein lies the threat posed by artificial intelligence to artists: when AI can produce nearly endless creative works at near zero marginal cost, what will this mean for people who make a living via their artistic talents?

While people have lamented the prospect of AI destroying jobs for years, the discussion has remained largely theoretical. Until now. With the advent of generative AI tools that are readily available to the public, like Stable Diffusion, DALL-E and ChatGPT, the prospect of massive job losses in creative industries is rapidly becoming a reality. Not surprisingly, many creative workers – including artists, illustrators, photographers and copywriters – are fearful for their livelihoods, and not without reason.

If we believe that creative expression is inherently meaningful, and the works it produces are intrinsically valuable, then this assault on artists’ jobs would be a net loss for humanity. It’s one thing for machines to replace labourers on farms; it’s another thing entirely for AI to empty studios of artists.

But despite all the lamentations about the impact of AI on art, when I dug deeper, I realised that it’s not really AI that poses the greatest threat to art. It’s capitalism. And instead of AI accelerating the decline of art, it could actually be the key that unshackles us from our current form of scarcity capitalism and allows art to genuinely flourish.

The alienation of art

As soon as art is brought into the market, it changes. Instead of a work’s value being defined in terms of its meaning or cultural significance, it becomes defined in terms of how much someone else is willing to pay for it. Art effectively becomes a product to be bought and sold.

Given the cost of producing art – and by “art” I mean all modes of creative expression, including music, dance, poetry, fiction, etc. – and the necessity of earning money to exchange for other goods, then art necessarily becomes professionalised.

This creates distinctions between different categories of artist. One is between those who create art for fun, so-called ‘amateurs’ (from the Latin amare, meaning “one who loves”), and those who create art for money, whom we can call ‘professionals’. The latter group, and society in general, tend to look down upon amateurs as engaging in art only frivolously or lacking the talent to make it in the competitive market.

The other distinction is among professionals, and is between those who work as commercial illustrators, designers, photographers, musicians, copywriters, etc., and the very small subset of their number, whom we might call ‘purists’, who are skilled or lucky enough to be able to produce the art they want, and can make a living out of it, either through selling to enthusiasts or collectors, or by securing grants. The purists, in turn, tend to look down on professionals as being sell-outs, or lacking the talent to make it in the rarefied art world.

The capitalist dynamic that produces these distinctions has the unfortunate consequence that many people choose not to create art at all, either because they don’t believe they are skilled enough to compete in the market, as if that were the only standard by which one might be measured, or they consider amateur art to be less than worthy. As a result of the commercialisation of art, there are likely many fewer painters, dancers, musicians and poets, than there might otherwise be.

Who’s under threat?

It’s important to recognise that when it comes to AI, it’s primarily the professionals who are at risk. These are the artists who produce the kinds of products that AI is increasingly able to create at lower cost.

AI doesn’t appear to present much of threat to purists, given that grant-givers and collectors are often spending based on the name in the corner as much as the other marks on the canvas, as it were. Purists can also do something that AI can’t: translate their personal experiences into creative expression. Amateurs are also not much at risk from AI because they don’t, for the most part, seek to derive an income from their works.

If we focus on professionals, we can see something else that the commodification and professionalisation of art have done: alienate the artist from their work.

Professionals often work to a brief defined by another person. Their art is often a means to a commercial end, such as capturing a prospective customer’s attention with a graphic or jingle, or by gussing up the interior of a restaurant. Some of this work can be deeply meaningful and rewarding, but much of it is far removed from what the artist would otherwise create were they not in dire need of money to pay the bills.

As one commenter on YouTube remarked: “As an artist I’m constantly conflicted with needing to make art that has ‘market value’ and can be sold to someone to financially support myself, and just making art for art’s sake because I want to make something that I like, and to express myself through the power of creativity.”

This alienation of the artist from the work they genuinely wish to produce has been discussed at length as far back as by Karl Marx. It’s also the reason why Pablo Picasso joined the Community Party.

It means that much of the art produced by professionals is, by its commercial nature, also helping to reinforce the very commercial system that binds it. This undermines one of the core social functions of art, which is to be a form of political expression, often employed to highlight and challenge the power structures that stifle and oppress humanity.

From this perspective, I saw that capitalism has already made the world hostile to art. AI is just worsening the situation of those have chosen to make a career out of their artistic talents.

AI acceleration

I can see two bad responses to this situation. The first is to attempt to stuff the AI genie back in the bottle. Some are attempting to do that right now, primarily through a series of court cases against some of the major generative AI companies under the pretence of copyright violation.

The outcome of these cases (assuming they are not settled or dismissed) will likely have a tremendous impact on the future of generative AI. However, it’s far from clear that US copyright law, where the cases are being held, will find that generative AI has done anything illegal. At best, the courts might require that artists are able to opt-in or opt-out of the datasets used to train AI. But even that seems unlikely.

The second bad response is to let AI run unfettered within the current economic paradigm, where it could destroy more jobs than it creates, put millions of professional artists out of work, and concentrate wealth and exacerbate inequality to an unprecedented degree. Should that happen, it’d create a genuine dystopia, and not just for artists.

The good news is that I can see at least one good solution. This is to leverage the power of AI to dramatically boost productivity and lower costs, and use that new wealth to improve everyone’s lives through a mechanism such as a universal basic income, greater subsidies or public funding, a shorter working week or a combination of them all.

I’m not alone in endorsing this idea about transforming capitalism. Sam Altman, the CEO of OpenAI, which created ChatGPT and DALL-E, has argued something very similar in an essay called Moore’s Law for Everything. In it, he states that “we need to design a system that embraces this technological future and taxes the assets that will make up most of the value in that world – companies and land – in order to fairly distribute some of the coming wealth. Doing so can make the society of the future much less divisive and enable everyone to participate in its gains.”

This would likely be a multi-decadal project, but it would set us on a course that would decouple the work that we do from the income that we earn. This could release artists from the shackles of capitalism, as they’ll be increasingly able to produce the art that is meaningful for them without requiring that it be saleable in a competitive market.

It’d also free up more time for amateurs to explore their creative potential, possibly resulting in an explosion of art. Imagine how many people would pick up a paintbrush, pen or piano if they had the time and financial security to do so.

Much of that creative output will be low quality, but that’s not the point. If we believe that the creative act is inherently valuable, then it’s worth it. Plus, there are likely many people of startling artistic talent who are currently otherwise occupied earning a living to be able to explore and develop their abilities.

The decoupling of art from the market could also help liberate its political power, enabling more artists to question, challenge and offer solutions to society’s many problems without having their livelihood threatened.

The big question is how do we get from a world where AI is stripping people of their livelihoods to one where AI is freeing them from toil? There are no easy answers to that question. But it’s crucial to focus our attention on the root cause of the problem that artists face today, and that’s not AI, it’s capitalism.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

Inside The Mind Of FODI Festival Director Danielle Harvey

Explainer, READ

Relationships, Society + Culture

Ethics Explainer: Shame

Big thinker

Science + Technology

Seven Influencers of Science Who Helped Change the World

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Society + Culture

Banking royal commission: The world of loopholes has ended

BY Dr Tim Dean

Dr Tim Dean is Philosopher in Residence at The Ethics Centre and author of How We Became Human: And Why We Need to Change.

Age of the machines: Do algorithms spell doom for humanity?

Age of the machines: Do algorithms spell doom for humanity?

Opinion + AnalysisRelationshipsScience + Technology

BY Nick Jarvis 14 OCT 2022

The world’s biggest social media platform’s slide into a cesspit of fake news, clickbait and shouty trolling was no accident.

“Facebook gives the most reach to the most extreme ideas. They didn’t set out to do it, but they made a whole bunch of individual choices for business reasons,” Facebook whistleblower Frances Haugen said.

In her Festival of Dangerous Ideas talk Unmasking Facebook, data engineer Haugen explained that back in Facebook’s halcyon days of 2008, when it actually was about your family and friends, your personal circle wasn’t making enough content to keep you regularly engaged on the platform. To encourage more screentime, Facebook introduced Pages and Groups and started pushing them on its users, even adding people automatically if they interacted with content. Naturally, the more out-there groups became the more popular ones – in 2016, 65% of people who joined neo-Nazi groups in Germany joined because Facebook suggested them.

By 2019 (if not earlier), 60% of all content that people saw on Facebook was from their Groups, pushing out legitimate news sources, bi-partisan political parties, non-profits, small businesses and other pages that didn’t pay to promote their posts. Haugen estimates content from Groups is now 85% of Facebook.

I was working for an online publisher between 2013 and 2016, and our traffic was entirely at the will of the Facebook algorithm. Some weeks we’d be prominent in people’s feeds and get great traffic, other weeks it would change without warning and our traffic and revenue would drop to nothing. By 2016, the situation had gotten so bad that I was made redundant and in 2018 the website folded entirely and disappeared from the internet.

Personal grievances aside, Facebook has also had sinister implications for democracy and impacts on genocide, as Haugen reminds us. The 2016 Trump election exposed serious privacy deficits at Facebook when 87 million users had their data leaked to Cambridge Analytica for targeted pro-Trump political advertising. Enterprising Macedonian fake news writers exploited the carousel recommended link function to make US$40 million pumping out insane – and highly clickable – alt-right conspiracy theories that undoubtedly played a part in helping Trump into the White House – along with the hackers spreading anti-Clinton hate from the Glavset in St Petersburg.

Worse, the Myanmar government sent military officials to Russia to learn to use online propaganda techniques for their genocide of the Muslim Rohingya from 2016 onwards, flooding Facebook with vitriolic anti-Rohingya misinformation and inciting violence against them. As The Guardian reported, around that time Facebook had only two Burmese-speaking content moderators. Facebook has also been blamed for “supercharging hate speech and inciting ethnic violence” (Vice) in Ethiopia over the past two years, with engagement-based ranking pushing the most extreme content to the top and English-first content moderation systems being no match for linguistically diverse environments where Facebook is the internet.

There are design tools that can drive down the spread of misinformation, like forcing people to click on an article before they blindly share it and putting up a barrier between fourth person plus sharers, so they must copy and paste content before they can share or react to it. These have the same efficacy at preventing misinformation spread as third-party fact-checkers and work multi-lingually, Haugen said, and we can mobilise as nations and customers to put pressure on companies to implement them.

But the best thing we can do is insist on having humans involved in the decision-making process about where to focus our attention, because AI and computers will always automatically opt for the most extreme content that gets the most clicks and eyeballs.

For technology writer Kevin Roose, though, in his talk Caught in a Web, we are already surrounded by artificial intelligence and algorithms, and they’re only going to get smarter, more sophisticated, and more deeply entrenched.

70% of our time on YouTube is now spent watching videos suggested by recommendation engines, and 30% of Amazon page views are from recommendations. We let Netflix preference shows for us, Spotify curate radio for us, Google Maps tell us which way to drive or walk, and with the Internet of Things, smart fridges even order milk and eggs for us before we know we need them.

A commercialised tool one AI researcher told Roose about called pedestrian reidentification can identify you from multiple CCTV feeds, put that together with your phone’s location data and bank transactions and figure out to serve you an ad for banana bread as you’re getting off the train and walking towards your favourite café.

And in news that will horrify but not surprise journalists, Roose said we’re entering a new age of ubiquitous synthetic media, in which articles written by machines will be hyper personalised at point of click for each reader by crawling your social media profiles.

After 125 years of the reign of ‘all the news that’s fit to print’, we’re now entering the era of “all the news that’s dynamically generated and personalised by machines to achieve business objectives.”

How can we fight back and resist this seemingly inevitable drift towards automation, surveillance and passivity? Roose highlights three things to do:

Quoting Socrates, Know Thyself. Know your own preferences and whether you’re choosing something because you like it or because the algorithm suggested it to you.

Resist Machine Drift – this is where we unconsciously hand over more and more of our decisions to machines, and “it’s the first step in losing our autonomy.” He recommends “preference mapping” – writing down a list of all your choices in a day, from what you ate or listened to, to what route you took to work. Did you make the decisions, or did an app help you?

Invest in Humanity. By this he means investing time in improving our deeply human skills that computers aren’t good at, like moral courage, empathy and divergent, creative thinking.

Roose is optimistic in this regard – as AI gets better at understanding us and insinuating its way into our lives, he thinks we’re going to see a renewed reverence for humanism and the things machines can’t do. That means more appreciation for the ‘soft’ skills of health care workers, teachers, therapists, and even an artisanal journalism movement written by humans.

I can’t be quite as optimistic as Roose – these soft skills have never been highly valued in capitalism and I can’t see it changing (I really hope I’m wrong), but I do agree with him that each new generation of social media app (e.g. Tik Tok and BeReal), in the global West at least, will be less toxic than the one before it, driven by the demands of Millennials and Generation Z, and those to come.

Eventually, this generational movement away from the legacy social media platforms, which have become infected with toxicity, will cause them to either collapse or completely reshape their business model to be like newer apps if they’re going to keep operating in fragile countries and emerging economies.

And that’s one reason to not let the machines win.

Visit FODI on demand for more provocative ideas, articles, podcasts and videos.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Assisted dying: 5 things to think about

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Double-Effect Theory

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

The historical struggle at the heart of Hanukkah

Opinion + Analysis

Science + Technology

Why ethics matters for autonomous cars

BY Nick Jarvis

Nick Jarvis is a Sydney-based editor and writer on the arts, culture and technology. He's written for The Ethics Centre, the Walkleys, Sydney Festival, Sydney Film Festival, Vice and many Australian arts organisations. He currently works for Sydney Festival.

Big tech knows too much about us. Here’s why Australia is in the perfect position to change that

Big tech knows too much about us. Here’s why Australia is in the perfect position to change that

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + LeadershipScience + Technology

BY The Ethics Alliance Emma Elsworthy 30 SEP 2022

Consumer Rights Data will bring an era of “commercial morality”, experts say.

Who are you? The question springs to mind a list of identity pillars – gender, job title, city, political leaning or perhaps a zany descriptor like “caffeine enthusiast!”. But who does big tech think you are?

Most of the time, we live in digital ignorance of the depth of data being scraped from everything from our Google searches to our Apple Pay purchases. Occasionally, however, we become only too aware of our own surveillance – looking at cute dog videos, for instance, and suddenly seeing ads for designer dog leashes in our Facebook feed.

It gets darker. In the wake of the US rolling back abortion law Roe v Wade, American women were discouraged from tracking their periods using an app on their smartphones. Big tech, pundits warn, could know when you’re pregnant – or more chillingly, whether you remained so.

In July, a report from Australian-US cybersecurity firm Internet 2.0 found popular youth-focused social media app TikTok could see user contact lists, access calendars, scan hard drives (including external ones) and geolocate our phones – and therefore us – on an hourly basis.

It’s “overly intrusive” data harvesting, the report found, considering “the application can and will run successfully without any of this data being gathered”.

Android users are far more exposed than Apple users because iOS significantly limits what information an app can gather. Apple has what is known as a “justification system”, meaning if an app developer wants access to something, it has to justify the requirement before Apple will permit it.

Should we be worried about TikTok’s access to our inner lives? With simmering geotensions between Australia and China – perhaps. The app is owned by ByteDance, a Beijing-based internet company, and the report found that “Chinese authorities can actually access device data”.

Professor of Business Information Systems at the University of Sydney Uri Gal writes that “TikTok’s data can also be used to compile detailed user profiles of Australians at scale”.

“Given its large and young Australian user base, it is quite likely that our country’s future prime minister and cabinet members are being surveilled and profiled by China,” he warned.

Australia is in a strong position to take action on the better protection of consumer data. Our world-leading Consumer Data Right (CDR) is being rolled out across Australia’s banking, energy and telecommunication sectors, placing the right to know about us back into our own hands.

Could our consumer rights expand beyond privacy rights to include specific economic rights too? Almost certainly, under CDR.

For instance, energy consumers would no longer have to wade through confusing fine print to work out whether they’re getting the best (and cheapest) electricity deal – with a click of a button they’d have their energy usage data sent to a new potential supplier, and the supplier would come back with a comparison.

That means no endless forms of information required upfront by a new provider, no lengthy phone calls spent cancelling one’s current provider, and crucially, no last-minute left-field discounts from a provider to keep you as a customer.

“Within five years, it should have transformed commerce, promoted competition in many sectors, and simplified daily life,” according to The University of NSW’s Ross P Buckley and Natalia Jevglevskaja.

“Thirty years ago, most Australian businesses thought charging current customers more than new customers was unfair and the law reflected this – such differential pricing was illegal,” the pair continued.

“Today those standards of behaviour seem to have fallen away and this is reflected in more relaxed consumer laws. In many contexts, CDR should reinstitute a commercial morality, a basic fairness, that modern business practices have set aside.”

A rethink of what it means to operate with transparency is what motivates fintech Flare, which aims at transforming the way Australians earn and engage in the workplace with superannuation, banking, and HR services.

Flare’s Head of Strategy Harry Godber was actually one of the original architects of CDR’s launch, which took place during his time in government as a former senior government advisor to Liberal prime ministers Malcolm Turnbull and Scott Morrison.

“[CDR] is designed to get rid of those barriers, get rid of the information asymmetry and allow you to have as much information about your banking products as someone else in the market as your bank has about you,” Godber said.

It’s a great equaliser, he continues, in that data will no longer separate the “haves and the have-nots” in the consumer world – essentially, financial literacy won’t ensure a consumer gets a better deal on products.

“That is a huge step forward when it comes to distributing financial products in an ethical way,” he continued.

“Because essentially it means if all data is equal, if everybody has access to every financial institution’s open product data and knows exactly how they will be treated then acquiring a customer suddenly becomes a matter of having good products, and very little else.”

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Risky business: lockout laws, sharks, and media bias

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Health + Wellbeing

Navigating a workforce through stressful times

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Following a year of scandals, what’s the future for boards?

Opinion + Analysis

Climate + Environment, Science + Technology

The kiss of death: energy policies keep killing our PMs

BY The Ethics Alliance

The Ethics Alliance is a community of organisations sharing insights and learning together, to find a better way of doing business. The Alliance is an initiative of The Ethics Centre.

BY Emma Elsworthy

Before joining Crikey in 2021 as a journalist and newsletter editor, Emma was a breaking news reporter in the ABC’s Sydney newsroom, a journalist for BBC Australia, and a journalist within Fairfax Media’s regional network. She was part of a team awarded a Walkley for coverage of the 2019-2020 bushfire crisis, and won the Australian Press Council prize in 2013.

5 things we learnt from The Festival of Dangerous Ideas 2022

5 things we learnt from The Festival of Dangerous Ideas 2022

Opinion + AnalysisRelationshipsScience + TechnologySociety + Culture

BY The Ethics Centre 20 SEP 2022

Crime, culture, contempt and change – this year our Festival of Dangerous Ideas speakers covered some of the dangerous issues, dilemmas and ideas of our time.

Here are 5 things we learnt from FODI22:

1. Humans are key to combating misinformation

Facebook whistleblower Frances Haugen says the world’s biggest social media platform’s slide into a cesspit of fake news, clickbait and shouty trolling was no accident – “Facebook gives the most reach to the most extreme ideas – and we got here through a series of individual decisions made for business reasons.”

While there are design tools that will drive down the spread of misinformation and we can mobilise as customers to put pressure on the companies to implement them, Haugen says the best thing we can do is have humans involved in the decision-making process about where to focus our attention, as AI and computers will automatically opt for the most extreme content that gets the most clicks and eyeballs.

2. We must allow ourselves to be vulnerable

In an impassioned love letter “to the man who bashed me”, poet and gender non-conforming artist, Alok teaches us the power of vulnerability, empathy and telling our own stories. “What’s missing in this world is a grief ritual – we carry so much pain inside of us, and we have nowhere to put the pain so we put it in each other.”

The more specific our words are the more universally we resonate, Alok says, “what we’re looking for as a people is permission – permission not just to tell our stories, but also to exist.”

3. We have to know ourselves better than machines do

Tech columnist and podcaster, Kevin Roose says “we are all different now as a result of our encounters with the internet.” From ‘recommended for you’ pages to personalisation algorithms, every time we pick up our phones, listen to music, watch Netflix, these persuasive features are sitting on the other side of our screens, attempting to change who we are and what we do. Roose says we must push back on handing all control to AI, even if it’s time consuming or makes us feel uncomfortable.

“We need a deeper understanding of the forces that try to manipulate us online – how they work, and how to engage wisely with them is the key not only to maintaining our independence and our sense of selves, but also to our survival as a species.”

4. We can use shame to change behaviour

Described by writer Jess Hill as “the worst feeling a human can possibly have”, the World Without Rape the panel discuss the universal theme of shame when it comes to sexual violence and its use as a method of control.

Instead of it being a weight for victims to bear, historian Joanna Bourke talks about shame as a tool to change perpetrator behaviour. “Rapists have extremely high levels of alcohol abuse and drug addictions because they actually do feel shame… if we have feminists affirming that you ought to feel shame then we can use that to change behaviour.”

5. Reason, science and humanism are the key to human progress

Steven Pinker believes in progress, arguing that the Enlightenment values of reason, science and humanism have transformed the world for the better, liberating billions of people from poverty, toil and conflict and producing a world of unprecedented prosperity, health and safety.

But that doesn’t mean that progress is inevitable. We still face major problems like climate change and nuclear war, as well as the lure of competing belief systems that reject reason, science and humanism. If we remain committed to Enlightenment values, we can solve these problems too. “Progress can continue if we remain committed to reason, science and humanism. But if we don’t, it may not.”

Catch up on select FODI22 sessions, streaming on demand for a limited time only.

Photography by Ken Leanfore

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Moving on from the pandemic means letting go

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

People with dementia need to be heard – not bound and drugged

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Science + Technology

Is it right to edit the genes of an unborn child?

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Banning euthanasia is an attack on human dignity

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Finance businesses need to start using AI. But it must be done ethically

Finance businesses need to start using AI. But it must be done ethically

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + LeadershipScience + Technology

BY The Ethics Centre 2 AUG 2022

Banking and finance businesses can’t afford to ignore the streamlining and cost reduction benefits offered by Artificial Intelligence (AI).

Your business can’t effectively beat the competition marketing any product in the 21st century without using big data and AI. Given the immense amount of consumer data available – and the number of channels, segments and competitors – marketers need to use AI and algorithms to operate successfully in the online environment.

But AI must be used prudently. Business managers must be meticulous in setting up rules for the algorithms’ decision making to prevent AI, which lacks a human’s inherent moral and ethical guiding force, from targeting ads towards unsuitable or vulnerable customers, or making decisions that exacerbate entrenched racial, gender, age, socio-economic, or other disparities and prejudices.

The Banking and Finance Oath’s 2021 Young Ambassadors recognised a gap in the research and delivered report: AI driven marketing in financial services: ethical risks and opportunities. It unravels the complexities of AI’s impact across the financial services industry and government, and establishes a framework that can be applied to other contexts.

In a marketing environment, AI can be used to streamline processes by generating personalised content for customers or targeting them with individual offers; leveraging customers’ data to personalise web and app pages based on their interests; enhancing customer service with chatbots; and supporting a seamless purchasing journey from phone to PC to in-person at a storefront.

Machine learning algorithms draw from immense data pools, such as customers’ credit card transactions and social media click-throughs to predict the likelihood of customers being interested in a product, whether to show them an ad and what ad to show them. But there are ethical risks to navigate at every step – from the quality of the data used to how well the developers and business managers understand the business objectives.

Using AI for marketing in financial services comes with two significant risks. The first is the potential for organisations to be seen as preying on people in vulnerable circumstances.

AI has no moral oversight or human awareness – it simply crunches the numbers and makes the most advantageous and profitable decision to lead to a sales conversion.

And if that decision is to target home loan ads at people going through a divorce or a loved one’s funeral, or to target credit card ads at people who are unemployed or living with addiction, without proper oversight, there’s nothing to stop it.

The other risk is the potential for data misuse and threats to privacy. Customers have a right to their own data and to know how it’s being used – and what demographics they’re being placed in. If your data’s out of date or inaccurate, or missing in sections, you’ll be targeting the wrong people.

All demographics – including racial background, socio-economic status, and individual psychological profile – have the potential to be misused by AI to reinforce gender, racial, age, economic and other disparities and prejudices.

Most ethical failings in AI-driven marketing campaigns can be traced back to issues with governance – poor management of data and lack of communication between developers and business managers. These data governance issues include: siloed databases that don’t share definitions; datasets that don’t refresh quickly enough and become outdated; customer flags that are incorrect or missing; and too many people being designated as data owners, resulting in the deferral of responsibility.

In human driven decision making, there’s a clear line of command, from the Board, to management, to the frontline team. But in AI-driven decision making, the frontline team is replaced by two teams – the AI developers and the team of machines.

Communication gaps emerge where management may not be familiar with instructing AI developers and the field’s highly technical nature, and the developers may not be familiar with the jargon of the business. Training across the business can act to fill these gaps.

Before any business begins to integrate AI into its marketing (and overall) strategy, it’s crucial that it adopt a set of basic ethical principles, these being:

- Beneficence (or do good): personalise products to improve the customer’s experience and improve their financial literacy by delivering targeted advice.

- Non-maleficence (or do no harm): ensure your AI marketing doesn’t target customers in inappropriate or harmful ways.

- Justice: ensure your data doesn’t discriminate based on demographics and exacerbate racial, gender, age, socio-economic or other disparities or stereotypes.

- Explicability: you need to be able to explain how your AI system makes the decisions it does and the relation between its inputs and outputs. Experts should be able to understand its results, predictions, recommendations and classifications.

- Autonomy: at the company level, governance processes should keep humans informed of what’s happening; and at a customer level, responsible decision making should be supported through personalisation and recommendation tools.

The reality is that no business can afford to ignore the benefits AI offers, but the risks are very real. By acknowledging the ethical issues, businesses can seize the opportunities while mitigating the risks, benefiting themselves and their customers.

Download a copy of the report here.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Society + Culture

The Ethics Institute: Helping Australia realise its full potential

Opinion + Analysis

Science + Technology

A framework for ethical AI

Reports

Business + Leadership

Ethics in the Boardroom

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights

Could a virus cure our politics?

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Who does work make you? Severance and the etiquette of labour

Who does work make you? Severance and the etiquette of labour

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + LeadershipRelationshipsScience + TechnologySociety + Culture

BY Joseph Earp 1 AUG 2022

There are certain things that some of us choose and do not choose, to tell those who we work with.

You come in on a Monday, and you stand around the coffee machine (the modern-day equivalent of the water cooler), and somebody asks you: “so, what did you get up to this weekend?”

Then you have a choice. If you fought with your partner, do you tell your colleague that? If you had sex, do you tell them that? If your mother is sick, or you’re dealing with a stress that society has broadly considered “intimate” to reveal, do you say something? And if you do, do you change the nature of the work relationship? Do you, in a phrase, “freak people out?”

These social conditions – norms, established and maintained by systems – are not specific to work, of course. Most spaces that we enter into and share with other people have an implicit code of conduct. We learn these codes as children – usually by breaking the rules of the codes, and then being corrected. And then, for the rest of our lives, we maintain these codes, often without explicitly realising what we are doing.

There are things you don’t say at church. There are things you do say in a therapist’s office. This is a version of what is called, in the world of politics, the “Overton Window”, a term used to describe the range of ideas that are considered “normal” or “acceptable” to be discussed publicly.

These social conditions are formed by us, and are entirely contingent – we could collectively decide to change them if we wanted to. But usually – at most workplaces, importantly not all – we don’t. Moreover, these conditions go past certain other considerations, about, say honesty. It doesn’t matter that some of us spend more time around our colleagues than those we call our partners. This decision about what to withhold in the office is frequently described as a choice about “professionalism”, which is usually a code word for “politeness.”

Severance, the new Apple television show which has been met with broad critical acclaim, takes the way that these concepts of professionalism and politeness shape us to its natural endpoint. The sci-fi show depicts an office, Lumon Industries, where employees are implanted with a chip that creates “innie” and “outie” selves.

Their innie self is their work self – the one who moves through the office building, and engages in the shadowy and disreputable jobs required by their employer. Their outie self is who they are when they leave the office doors. These two selves do not have any contact with, or knowledge of each other. They could be, for all intents and purposes, strangers, even though they are – on at least one reading – the “same person.”

The chip is thus a signifier for a contingent code of social practices. It takes something that is implicit in most workplaces, and makes it explicit. We might not consider it a “big deal” when we don’t tell Roy from accounts that, moments before we walked in the front door of the office, we had a massive blow-up over the phone with our partner. Which may help Roy understand why we are so ‘tetchy’ this morning. But it is, in some ways, a practice that shapes who we are.

According to the social practices of most businesses, it is “professional” – as in “polite” – not to, say, sob openly at one’s desk. But what if we want to sob? When we choose not to, we are being shaped into a very particular kind of thing, by a very particular form of etiquette which is tied explicitly to labor.

And because these forms of etiquette shape who we are, they also shapes what we know. This is the line pushed by Miranda Fricker, the leading feminist philosopher and pioneer in the field of social epistemology – the study of how we are constructed socially, and how that feeds into how we understand and process the world.

For Fricker, social forces alter the knowledge that we have access to. Fricker is thinking, in particular, about how being a woman, or a man, or a non-binary person, changes the words we have access to in order to explain ourselves, and thus how we understand things. That access is shaped by how we are socially built, and when we are blocked from access, we develop epistemic blindspots that we are often not even aware that we have.

In Severance, these social forces that bar access are the forces of capitalism. And these forces make the lives of the characters swamped with blindspots. Mark, the show’s hero, has two sides – his innie, and his outie. Things that the innie Mark does hurt and frustrate the desires of the outie Mark.

Both versions of him have such significant blindspots, that these “separate” characters are actively at odds. Much of the show’s first few episodes see these two separate versions of the same person having to fight, and challenge one another, with Mark striving for victory over outie Mark.

The forces of etiquette are always for the benefit of those in power. We, the workers at certain organisations, might maintain them, but their end result is that they meaningfully commodify us – make us into streamlined, more effective and efficient workers.

So many of us have worked a job that has asked us to sacrifice, or shape and change certain parts of ourselves, so as to be more “professional”. Which is a way of saying that these jobs have turned us into vessels for labour – emphasised the parts of us that increase productivity, and snipped off the parts that do not.

The employees of Lumon live sad, confused lives full of pain, riddled with hallucinations. The benefit of the code of etiquette is never to them. They get paid, sure. But they spend their time hurting each other, or attempting suicide, or losing their minds. Their titular severance helps the company, never them.

This is what the theorist Mark Fisher refers to when he writes about the work of Franz Kafka, one of our greatest writers when it comes to the way that politeness is weaponised against the vulnerable and the marginalized. As Fisher points out, Kafka’s work examines a world in which the powerful can manipulate those that they rule and control through the establishment of social conduct; polite and impolite; nice and not nice.

Thus, when the worker does something that fights back against their having become a vessel for labour, the worker can be “shamed”, the structure of etiquette used against them. This happens all the time in the world of Severance. As the season progresses, and the characters get involved in complex plots that involve both their innie and outie selves, the threat is always that the code of conduct will be weaponised against them, in a way that further strips down their personality; turns them into more of a vessel.

And, as Fisher again points out, because these systems of etiquette are for the benefit of the powerful, the powerful are “unembarrassable.” Because they are powerful – because they are the employer – whatever they do is “right” and “correct” and “polite.” Again, the rules of the game are contingent, which means that they are flexible. This is what makes them so dangerous. They can be rewritten underneath our feet, to the benefit of those in charge.

Moreover, in the world of the show, the characters “choose” to strip themselves of agency and autonomy, because of the dangling carrot of profit. This sharpens the satirical edge of Severance. It’s not just that the snaking rules of the game that we talk about when we talk about “good manners” make them different people. It’s that the characters of the show submit to these rules. They themselves maintain them.

Nobody’s being “forced”, in the traditional sense of that word, into becoming vessels for labour. This is not the picture of worker in chains. They are “choosing” to take the chip, and to work for Lumon. But are they truly free? What is the other alternative? Poverty? And what, actually, makes Lumon so different? A swathe of companies have these rules of etiquette. Which means a swathe of companies do precisely the same thing.

This is a depressing thought. But the freedom from this punishment lies, as it usually does, in the concept of contingency. Etiquette enforces itself; it punishes, through social isolation and exclusion, those who break its rules.

But these rules are not written on a stone tablet. And the people who are maintaining them are, in fact, all of us. Which means that we can change them. We can be “unprofessional.” We can be “impolite”. We can ignore the person who wants to alter our behaviour by telling us that we are “being rude.” And in doing so, we can fight back against the forces that want to make us one kind of vessel. And we can become whatever we’d like to be.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Truth & Honesty

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Between frenzy and despair: navigating our new political era

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Narcissists aren’t born, they’re made

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Power play: How the big guys are making you wait for your money

BY Joseph Earp

Joseph Earp is a poet, journalist and philosophy student. He is currently undertaking his PhD at the University of Sydney, studying the work of David Hume.

We are being saturated by knowledge. How much is too much?

We are being saturated by knowledge. How much is too much?

Opinion + AnalysisRelationshipsScience + Technology

BY The Ethics Centre 28 JUL 2022

We’re hurtling into a new age where the notion of evidence and knowledge has become muddied and distorted. So which rabbit hole is the right one to click through?

Our world is deeply divided, and we have found ourselves in a unique moment in history where the idea of rational thought seems to have been dissolved. It’s no longer as clear cut what is right and just to believe….So what does it mean to truly know something anymore?

According to Emerson, the number one AI chat bot in the world, “rational thought is the process of forming judgements based on evidence” which sounds simple enough. It’s easy to form judgements based on evidence when the object of judgement is tangible — this cheese pizza is delicious, a cat playing a keyboard wearing glasses is funny. These are ideas on which people from all sides of the political spectrum can come to some form of agreement (with a little friendly debate).

But what happens when the ideas become a little more lofty? It’s human nature to believe that our one’s ideas are rational, well reasoned, and based on evidence. But what constitutes evidence in these information rich times?

We’re hurtling into a new age where even the notion of “evidence” has become muddied and distorted.

So where do we even begin — which news is the real news and what’s the responsible way to respond to the news that someone as intelligent as you, in possession of as much evidence as you, believes a different conclusion?

Philosopher Eleanor Gordon-Smith suggests, “There are many, many circumstances in which we decline to avail ourselves of certain beliefs or certain candidate truths because we’re being very Cartesionally responsible and we’re declining to encounter the possibility of doubt. And meanwhile, those of us who are sort of warriors for the enlightenment of being very epistemically polite and trying to only believe those things that we’re allowed to do so on. The conspiracy theorists, meanwhile, consider themselves a veil of knowledge, which then they deploy in a very different way.”

Who gets to be smart?

Before the Enlightenment, the common man had no real business in the pursuit of knowledge, knowledge was very fiercely guarded by the Church and the Crown. But once it dawned on those honest folk that they could in fact have knowledge, it almost became a moral imperative to seize it, regardless of the obstacles.

Nowadays avoiding knowledge is an impossibility impossible. Access to information has been wholly democratised, if you’ve got a smart phone handy, any Google search will result in billions of possible pages and answers. It’s now your choice to determine which rabbit hole is the right one to click. To the untrained eye, there’s no differentiating between information that is thoroughly researched and fact checked and fake news. And according to Eleanor Gordon-Smith it is this saturation of knowledge has come to define our generation. So much so that the value of knowledge “has been subject to a kind of inflation”.

She asks, “how do you restore the emancipatory potential of knowledge that the Enlightenment founders saw? How do you get back the kind of bravery, the self development, the political resistance, the independence in the act of knowing in this particular moment…is there a way to restore the bravery and the value of knowledge in an environment where it’s so cheap and so readily available?”

It is this saturation of knowledge has come to define our generation. So much so that the value of knowledge “has been subject to a kind of inflation”.

Philosopher Slavoj Žižek suggests that perhaps our mistake is putting the Englightment on a pedestal, that those involved in the Enlightment’s pursuit of knowledge mischaracterised those who came before them as naive idiots. “Modernity is not just knowledge. It’s also on the other side, a certain regression to primitivity. The first lesson of good enlightenment is don’t simply fight your opponent. And that’s what’s happening today.”

Perhaps ignorance really is bliss

In the age of disinformation, misinformation and everything in between, admitting you don’t know something almost feels like an act of rebellion. American philosopher Stanley Cavell, boldly asked “how do we learn that what we need is not more knowledge but the willingness to forgo knowledge” (it’s worth noting that this line of questioning saw his publications banned from a number of American university libraries).

Sometimes it is better to be ignorant because, “true knowledge hurts. Basically, we don’t want to know too much. If we get to know too much about it, we will objectivise ourselves, we will lose our personal dignity, so to retain our freedom it’s better not to know too much.” – Žižek

Žižek however admits that we are in a the middle of the fight. We are not at the end of the story. We cannot afford ourselves this retroactive view in the sense of: who cares what is done is already done? “Philosophers have only interpreted the world, we have to change it. We tried to change the world too quickly without really adequately interpreting it. And my motto would have been that 20th century leftists were just trying to change the world. The time is also to interpret it differently. That’s the challenge.”

When the AI chat bot Emerson is asked, “how can you know if something is true” it responds, “truth is a matter of opinion” and given these tumultuous and divided times we are living through, there is perhaps no truer statement.

To delve deeper into the speakers and themes discussed in this article, tune into FODI: The In-Between The Age of Doubt, Reason and Conspiracy.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

Joker broke the key rule of comic book movies: it made the audience think

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Should we abolish the institution of marriage?

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

To deal with this crisis, we need to talk about ethics, not economics

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

This isn’t home schooling, it’s crisis schooling

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Big Thinker: Matthew Liao

Matthew Liao (1972 – present) is a contemporary philosopher and bioethicist. Having published on a wide range of topics, including moral decision making, artificial intelligence, human rights, and personal identity, Liao is best known for his work on the topic of human engineering.

At New York University, Liao is an Affiliate Professor in the Department of Philosophy, Director of the Center for Bioethics, and holds the Arthur Zitrin Chair of Bioethics. He is also the creator of Ethics Etc, a blog dedicated to the discussion of contemporary ethical issues.

A Controversial Solution to Climate Change

As the climate crisis worsens, a growing number of scientists have started considering geo-engineering solutions, which involves large-scale manipulations of the environment to curb the effect of climate change. While many scientists believe that geo-engineering is our best option when it comes to addressing the climate crisis, these solutions do come with significant risks.

Liao, however, believes that there might be a better option: human engineering.

Human engineering involves biomedically modifying or enhancing human beings so they can more effectively mitigate climate change or adapt to it.

For example, reducing the consumption of animal products would have a significant impact on climate change since livestock farming is responsible for approximately 60% of global food production emissions. But many people lack either the motivation or the will power to stop eating meat and dairy products.

According to Liao, human engineering could help. By artificially inducing mild intolerance to animal products, “we could create an aversion to eating eco-unfriendly food.”

This could be achieved through “meat patches” (think nicotine patches but for animal products), worn on the arm whenever a person goes grocery shopping or out to dinner. With these patches, reducing our consumption of meat and dairy products would no longer be a matter of will power, but rather one of science.

Alternatively, Liao believes that human engineering could help us reduce the amount of food and other resources we consume overall. Since larger people typically consume more resources than smaller people, reducing the height and weight of human beings would also reduce their ecological footprint.

“Being small is environmentally friendly.”

According to Liao, this could be achieved several ways for example, using technology typically used to screen embryos for genetic abnormalities to instead screen for height, or using hormone treatment typically used to stunt the growth or excessively tall children to instead stunt the growth of children of average height.

Reception

When Liao presented these ideas at the 2013 Ted Conference in New York, many audience members found the notion of wearing meat patches and making future generations smaller to be amusing. However, not everyone found these ideas humorous.

In response to a journal article Liao co-authored on this topic, philosopher Greg Bognar wrote that the authors were doing themselves and their profession a disservice by not adequately considering the feasibility or real cost of human engineering.

Although making future generations smaller would reduce their ecological footprint, it would take a long time for the benefits of this reduction in average height and weight to accrue. In comparison, the cost of making future generations smaller would be borne now.

As Bognar argues, current generations would need to devote significant resources to this effort. For example, if future generations were going to be 15-20cm shorter than current generations, we would need to begin redesigning infrastructure. Homes, workplaces and vehicles would need to be smaller too.

Liao and his colleagues do, however, recognise that devoting time, money, and brain power to pursuing human engineering means that we will have fewer resources to devote to other solutions.

But they argue that “examining intuitively absurd or apparently drastic ideas can be an important learning experience, and that failing to do so could result in our missing out on opportunities to address important, often urgent issues.”

While current generations may resent having to bear the cost of making future generations more environmentally friendly, perhaps it is a cost that we must bear.

Liao says, “We are the cause of climate change. Perhaps we are also the solution to it.”

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Science + Technology

The ethics of drug injecting rooms

Explainer

Relationships, Science + Technology

Ethics Explainer: Post-Humanism

Explainer

Science + Technology

Thought experiment: “Chinese room” argument

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Science + Technology