Ethics Explainer: Authenticity

Is the universe friendly? Is it fundamentally good? Peaceful? Created with a purpose in mind?

Or is it distant and impersonal? Indifferent to what you want? A never ending meaningless space? We all have ideas of how the world truly is. Maybe that’s been influenced by your religion, your school, your government, or even the video games you played as a kid.

Whatever the case is, how we think about ourselves and what we consider a life well spent, has a lot to do with the relationship we have with the world. And that brings us to this month’s Ethics Explainer.

Authenticity

To behave authentically means to behave in a way that responds to the world as it truly is, and not how we’d like it to be. What does this mean?

Well, this question takes us to two different schools of thought in philosophy, with two very different ideas of the nature of the world we live in. The first one is essentialism. Now, essentialism is a belief that find its roots in Ancient Greece, and in the writings of Socrates and Plato.

They took it as a given that everything that exists has its own essence. That is, a certain set of core properties that are necessary, or essential, for it to be what it is. Take a knife. It doesn’t matter if it has a wooden handle or a metal one. But once you take the blade away, it becomes not-a-knife. The blade is its essential property because it gives the knife its defining function.

Plato and Aristotle believed that people had essences as well, and that these existed before they did. This essence, or telos, was only acquired and expressed properly through virtuous action, a process that formed the ideal human. According to the Greeks, to be authentic was to live according to your essence. And you did that by living ethically in the choices you make and the character you express.

By developing intellectual virtues like curiosity or critical thinking, and character virtues like courage, wisdom, and patience, it’d get easier to tell what you should or shouldn’t do. This was the standard view of the world until the early 19th century, and is still the case for many people today.

The rise of existentialism

But some thinkers began to wonder, what if that wasn’t true? What if the universe has no inherent purpose? What if we don’t have one either? What if we exist first, then create our own purpose?

This belief was called existentialism. Existentialists believe that neither us nor the universe has an actual, predetermined purpose. We need to create it for ourselves. Because of this, nothing we do or are is actually inherently meaningful. We were free to do whatever we wanted – a fate Jean Paul-Sartre, French existential philosopher, found quite awful.

Being authentic meant facing the full weight of this shocking freedom, and staying strong. To simply follow what your religious leader, parent, school, or boss told you to do would be to act in “bad faith”. It’s like burying your head in the sand and pretending that something out there has meaning. Meaning that doesn’t exist.

By accepting that any meaning in life has to be given by you, and that ‘right’ and ‘wrong’ are just a matter of perspective, your choices become all you have. And ensuring that they are chosen by the values you accept to live by, instead of any predetermined ones etched in stone, makes them authentic.

This extends beyond the individual. If the world is going to have any of the things most of us value, like justice and order, we’re going to have to put it there ourselves.

Otherwise, they won’t exist.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

The niceness trap: Why you mustn’t be too nice

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

Meet Daniel, helping us take ethics to the next generation

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Climate + Environment

Blindness and seeing

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Online grief and the digital dead

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Ethics Explainer: The Turing Test

Much was made of a recent video of Duplex – Google’s talking AI – calling up a hair salon to make a reservation. The AI’s way of speaking was uncannily human, even pausing at moments to say “um”.

Some suggested Duplex had managed to pass the Turing test, a standard for machine intelligence that was developed by Alan Turing in the middle of the 20th century. But what exactly is the story behind this test and why are people still using it to judge the success of cutting edge algorithms?

Mechanical brains and emotional humans

In the late 1940s, when the first digital computers had just been built, a debate took place about whether these new “universal machines” could think. While pioneering computer scientists like Alan Turing and John von Neumann believed that their machines were “mechanical brains”, others felt that there was an essential difference between human thought and computer calculation.

Sir Geoffrey Jefferson, a prominent brain surgeon of the time, argued that while a computer could simulate intelligence, it would always be lacking:

“No mechanism could feel … pleasure at its successes, grief when its valves fuse, be warmed by flattery, be made miserable by its mistakes, be charmed by sex, be angry or miserable when it cannot get what it wants.”

In a radio interview a few weeks later, Turing responded to Jefferson’s claim by arguing that as computers become more intelligent, people like him would take a “grain of comfort, in the form of a statement that some particularly human characteristic could never be imitated by a machine.”

The following year, Turing wrote a paper called ‘Computing Machinery and Intelligence’ in which he devised a simple method by which to test whether machines can think.

The test was a proposed a situation in which a human judge talks to both a computer and a human through a screen. The judge cannot see the computer or the human but can ask them questions via the computer. Based on the answers alone, the human judge had to determine which is which. If the computer was able to fool 30 percent of judges that it was human, then the computer was said to have passed the test.

Turing claimed that he intended for the test to be a conversation stopper, a way of preventing endless metaphysical speculation about the essence of our humanity by positing that intelligence is just a type of behaviour, not an internal quality. In other words, intelligence is as intelligence does, regardless of whether it done by machine or human.

Does Google Duplex pass?

Well, yes and no. In Google’s video, it is obvious that the person taking the call believes they are talking to human. So, it does satisfy this criterion. But an important thing about Turing’s original test was that to pass, the computer had to be able to speak about all topics convincingly, not just one.

In fact, in Turing’s paper, he plays out an imaginary conversation with an advanced future computer and human judge, with the judge asking questions and the computer providing answers:

Q: Please write me a sonnet on the subject of the Forth Bridge.

A: Count me out on this one. I never could write poetry.

Q: Add 34957 to 70764.

A: (Pause about 30 seconds and then give as answer) 105621.

Q Do you play chess?

A: Yes.

Q: I have K at my K1, and no other pieces. You have only K at K6 and R at R1. It is your move. What do you play?

A: (After a pause of 15 seconds) R-R8 mate.

The point Turing is making here is that a truly smart machine has to have general intelligence in a number of different areas of human interest. As it stands, Google’s Duplex is good within the limited domain of making a reservation but would probably not be able to do much beyond this unless reprogrammed.

The boundaries around the human

While Turing intended for his test to be a conversation stopper for questions of machine intelligence, it has had the opposite effect, fuelling half a century of debate about what the test means, whether it is a good measure of intelligence, or if it should still be used as a standard.

Most experts have come to agree, over time, that the Turing test is not a good way to prove machine intelligence, as the constraints of the test can easily be gamed, as was the case with the bot Eugene Goostman, who allegedly passed the test a few years ago.

But the Turing test is nevertheless still considered a powerful philosophical tool to re-evaluate the boundaries around what we consider normal and human. In his time, Turing used his test as a way to demonstrate how people like Jefferson would never be willing to accept a machine as being intelligence not because it couldn’t act intelligently, but because wasn’t “like us”.

Turing’s desire to test boundaries around what was considered “normal” in his time perhaps sprung from his own persecution as a gay man. Despite being a war hero, he was persecuted for his homosexuality, and convicted in 1952 for sleeping with another man. He was punished with chemical castration and eventually took his own life.

During these final years, the relationship between machine intelligence and his own sexuality became interconnected in Turing’s mind. He was concerned the same bigotry and fear that hounded his life would ruin future relationships between humans and intelligent computers. A year before he took his life he wrote the following letter to a friend:

“I’m afraid that the following syllogism may be used by some in the future.

Turing believes machines think

Turing lies with men

Therefore machines do not think

– Yours in distress,

Alan”

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Science + Technology

The undeserved doubt of the anti-vaxxer

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Science + Technology

Meet Aubrey Blanche: Shaping the future of responsible leadership

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Science + Technology

The new rules of ethical design in tech

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Science + Technology

If humans bully robots there will be dire consequences

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Ethics Explainer: Perfection

We take perfection to mean flawlessness. But it seems we can’t agree on what the fundamental human flaw is. Is it our attachment to things like happiness, status, or security – things that are about as solid as a tissue? Our propensity for evil? Or is it our body and its insatiable appetite for satisfaction?

Four different philosophical traditions have answered this in their own ways and tell us how we can achieve perfection.

Platonism

Plato’s idea of perfection is articulated in his Theory of Forms. The Forms represent the abstract, ideal moulds of all things and concepts in existence, rather than actual things themselves. In short, the idea of something is more perfect than the tangible thing itself.

Take ‘red’ for example. Each of us will have a different understanding of what this means – red lipstick, a red brick house, a red cricket ball… But these are all different manifestations of red so which is the perfect one? For Platonists, the perfect, ideal, universal ‘red’ exists outside of space and time and is only discoverable through lots and lots of philosophical reflection.

Plato wrote:

He will do this [perceive the Forms] most perfectly who approaches the object with thought alone, without associating any sight with his thoughts, or dragging in any sense perception with his reasoning, but who, using pure thought alone, tries to track down each reality pure and by itself, freeing himself as far as possible from eyes, ears, and in a word, from the whole body, because the body confuses the soul and does not allow it to acquire truth and wisdom whenever it is associated with it.

In Platonist thought, the body is a distraction from the abstract thought necessary for philosophical speculation. Its fundamental flaw? Its carnal desires that shackle the soul.

Perfection for the individual, to sum up, is the arrival back to the soul’s state of pure contemplation of the Forms. This out of body state of contemplation is far from the idea of the perfect face and physique we often think about today. Indeed, a perfect physical form for Palto is impossible. It is all in the imagination.

Hinduism

In Hinduism’s Advaita school of philosophy, perfection means the full comprehension and acceptance of Oneness.

It’s when you realise your soul (or your atman) is the same as everyone else’s and you are all part of the one, unchanging, metaphysical reality (the Brahman). In this state of realisation, the always changing, material world of maya reveals itself to be an illusion and anything attached to this world, including your actions, are illusions as well. (There are parallels with this and the idea of Plato’s Cave, which is narratively conceived of in The Matrix.)

To attain this status of perfection, an individual must surrender to their caste role and perform that duty to excellence. No matter what they did, they would understand their actions had no effect on the Brahman and to believe so, was a trick of the ego. They focused on renouncing all earthly desires and striving to become completely detached from the world through the specific rituals of their caste role.

Krishna said:

A man obtains perfection by being devoted to his own proper action. Hear then how one who is intent on his own action finds perfection. By worshipping him [Brahman], from whom all beings arise and by whom all this is pervaded, through his own proper action, a man attains perfection … He whose intelligence is unattached everywhere, whose self is conquered, who is free from desire, he obtains, through renunciation, the supreme perfection of actionlessness. Learn from me, briefly, O Arjuna, how he who has attained perfection, also attains to Brahman, the highest state of wisdom.

By “actionlessness”, Krishna means the supreme effort of surrendering everything, including your own actions, so they become “non-action”. If everything is an illusion in the face of Brahman, we mean everything.

Christianity

A sainted bishop named Gregory of Nyssa classified perfection as being and acting just like God’s human form, Christ – that is, completely free of evil. Nyssa said:

This, therefore, is perfection in the Christian life in my judgement, namely, the participation of one’s soul and speech and activities in all of the names by which Christ is signified, so that the perfect holiness, according to the eulogy of Paul, is taken upon oneself in “the whole body and soul and spirit”, continuously safeguarded against being mixed with evil. Perfection lies in the total transformation of the individual. He/she must live, act, and essentially, be all that Christ was, meaning that, as Christ was God manifest in human form, completely free from evil, so too the Christian individual must sever all evil from his/her being.

While the Socratic ideal of perfection requires pure “abstract” thought, and the Hindu ideal requires sublimating individualism into Oneness, the Christian ideal requires cultivating the characteristics of Christ and expelling all that is unlike him from yourself.

Sufism

The Sufi scholar Ibn ‘Arabi had a concept of perfection that echoes the three discussed above. For him, perfection is the individual’s complete knowledge of the abstract and the material, leading to a prophetic (or Christ like) character.

Let’s break that down. He says:

The image of perfection is complete only with knowledge of both the ephemeral and the eternal, the rank of knowledge being perfected only by both aspects. Similarly, the various other grades of existence are perfected, since being is divided into eternal and non-eternal or ephemeral. Eternal Being is God’s being for Himself, while non-eternal being is the being of God in the forms of the latent Cosmos.

The beginning of the passage states that perfection requires knowledge of the eternal and the material. The eternal is God in Himself, and the non-eternal is the Cosmos, including humanity, who in striving for the perfection of the eternal, expresses it.

But Ibn ‘Arabi stresses neither of these knowledges negate the other. In fact, by learning only of the eternal, or only of the material, both would be incomplete since they are simply different manifestations of the same Being. Perfection, then, is not about negation – but continual striving to transformation. Onwards and upwards!

Follow The Ethics Centre on Twitter, Facebook, Instagram and LinkedIn.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Explainer

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Dignity

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Parenting philosophy: Stop praising mediocrity

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

What we owe our friends

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

What we owe to our pets

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Ethics Explainer: Universal Basic Income

Ethics Explainer: Universal Basic Income

ExplainerBusiness + LeadershipPolitics + Human Rights

BY The Ethics Centre 21 MAY 2018

The idea of a UBI isn’t new. In fact, it has deep historical roots.

In Thomas More’s Utopia, published in 1516, he writes that instead of punishing a poor person who steals bread, “it would be far more to the point to provide everyone with some means of livelihood, so that nobody’s under the frightful necessity of becoming, first a thief, and then a corpse”.

Over three hundred years later, John Stuart Mill also supported the concept in Principles of Political Economy, arguing that “a certain minimum [income] assigned for subsistence of every member of the community, whether capable of labour or not” would give the poor an opportunity to lift themselves out of poverty.

In the 20th century, the UBI gained support from a diverse array of thinkers for very different reasons. Martin Luther King, for instance, saw a guaranteed payment as a way to uphold human rights in the face of poverty, while Milton Friedman understood it as a viable economic alternative to state welfare.

Would a UBI encourage laziness?

Yet, there has always been strong opposition to implementing basic income schemes. The most common argument is that receiving money for nothing undermines work ethic and encourages laziness. There are also concerns that many will use their basic income to support drug and alcohol addiction.

However, the only successfully implemented basic income scheme has shown these fears might be unfounded. In the 1980s, Alaska implemented a guaranteed income for long term residents as a way to efficiently distribute dividends from a commodity boom. A recent study of the scheme found full-time employment has not changed at all since it was introduced and the number of Alaskans working part-time has increased.

The success of this scheme has inspired other pilot projects in Kenya, Scotland, Uganda, the Netherlands, and the United States.

The rise of the robots

The growing fear that robots are going to take most of our jobs over the next few decades has added an extra urgency to the conversation around UBI. A number of leading technologists, including Elon Musk, Mark Zuckerberg, and Bill Gates, have suggested some form of basic income might be necessary to alleviate the effects of unemployment caused by automation.

In his bestselling book Rise of the Robots, Martin Ford argues that a basic income is the only way to stimulate the economy in an automated world. If we don’t distribute the abundant wealth generated by machines, he says, then there will be no one to buy the goods that are being manufactured, which will ultimately lead to a crisis in the capitalist economic model.

In their book Inventing the Future, Nick Srnicek and Alex Williams agree that full automation will bring about a crisis in capitalism but see this as a good thing. Instead of using UBI as a way to save this economic system, the unconditional payment can be seen as a step towards implementing a socialist method of wealth distribution.

The future of work

Srnicek and Williams also claim that UBI would not only be a political and economic transformation, but a revolution of the spirit. Guaranteed payment, they say, will give the majority of humans, for the first time in history, the capacity to choose what to do with their time, to think deeply about their values, and to experiment with how to live their lives.

Bertrand Russell made a similar argument in his famous treatise on work, In Praise of Idleness. He writes that in a world where no one is compelled to work all day for wages, all will be able to think deeply about what it is they want to do with their lives and then pursue it. For many, he says, this idea is scary because we have become dependent on paid jobs to give us a sense of value and purpose.

So, while many of the debates about UBI take place between economists, it is possible that the greatest obstacle to its implementation is existential.

A basic payment might provide us with the material conditions to live comfortably, but with this comes the confounding task of re-thinking what it is that gives our lives meaning.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

John Elkington on business sustainability and ethics

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Climate + Environment, Society + Culture

Overcoming corruption in Papua New Guinea

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

If you don’t like politicians appealing to voters’ more base emotions, there is something you can do about it

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Ask the ethicist: Is it ok to tell a lie if the recipient is complicit?

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Ethics Explainer: Moral Absolutism

Moral absolutism is the position that there are universal ethical standards that apply to actions regardless of context.

Where someone might deliberate over when, why, and to whom they’d lie, for example, a moral absolutist wouldn’t see any of those considerations as making a difference – lying is either right or wrong, and that’s that!

You’ve probably heard of moral relativism, the view that moral judgments can be seen as true or false according to a historical, cultural, or social context. According to moral relativism, two people with different experiences could disagree on whether an action is right or wrong, and they could both be right. What they consider right or wrong differs according to their contexts, and both should be accepted as valid.

Moral absolutism is the opposite. It argues that everything is inherently right or wrong, and no context or outcome can change this. These truths can be grounded in sources like law, rationality, human nature, or religion.

Deontology as moral absolutism

The text(s) that a religion is based on is often taken as the absolute standard of morality. If someone takes scripture as a source of divine truth, it’s easy to take morally absolutist ethics from it. Is it ok to lie? No, because the Bible or God says so.

It’s not just in religion, though. Ancient Greek philosophy held strains of morally absolutist thought, but possibly the most well-known form of moral absolutism is deontology, as developed by Immanuel Kant, who sought to clearly articulate a rational theory of moral absolutism.

As an Enlightenment philosopher, Kant sought to find moral truth in rationality instead of divine authority. He believed that unlike religion, culture, or community, we couldn’t ‘opt out’ of rationality. It was what made us human. This was why he believed we owed it to ourselves to act as rationally as we could.

In order to do this, he came up with duties he called “categorical imperatives”. These are obligations we, as rational beings, are morally bound to follow, are applicable to all people at all times, and aren’t contradictory. Think of it as an extension of the Golden Rule.

One way of understanding the categorical imperative is through the “universalisability principle”. This mouthful of a phrase says you should act only if you’d be willing to make your act a universal law (something that everyone is morally bound to following at all times no matter what) and it wouldn’t cause contradiction.

What Kant meant was before choosing a course of action, you should determine the general rule that stands behind that action. If this general rule could willingly be applied by you to all people in all circumstances without contradiction, you are choosing the moral path.

An example Kant proposed was lying. He argued that if lying was a universal law then no one could ever trust anything anyone said but, moreover, the possibility of truth telling would no longer exist, rendering the very act of lying meaningless. In other words, you cannot universalise lying as a general rule of action without falling into contradiction.

By determining his logical justifications, Kant came up with principles he believed would form a moral life, without relying on scripture or culture.

Counterintuitive consequences

In essence, Kant was saying it’s never reasonable to make exceptions for yourself when faced with a moral question. This sounds fair, but it can lead to situations where a rational moral decision contradicts moral common sense.

For example, in his essay ‘On a Supposed Right to Lie from Altruistic Motives’, Kant argues it is wrong to lie even to save an innocent person from a murderer. He writes, “To be truthful in all deliberations … is a sacred and absolutely commanding decree of reason, limited by no expediency”.

While Kant felt that such absolutism was necessary for a rationally grounded morality, most of us allow a degree of relativism to enter into our everyday ethical considerations.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Begging the question

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Love and morality

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Science + Technology

To fix the problem of deepfakes we must treat the cause, not the symptoms

Big thinker

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Big Thinker: Noam Chomsky

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Ethics Explainer: Post-Humanism

Ethics Explainer: Post-Humanism

ExplainerRelationshipsScience + Technology

BY The Ethics Centre 22 FEB 2018

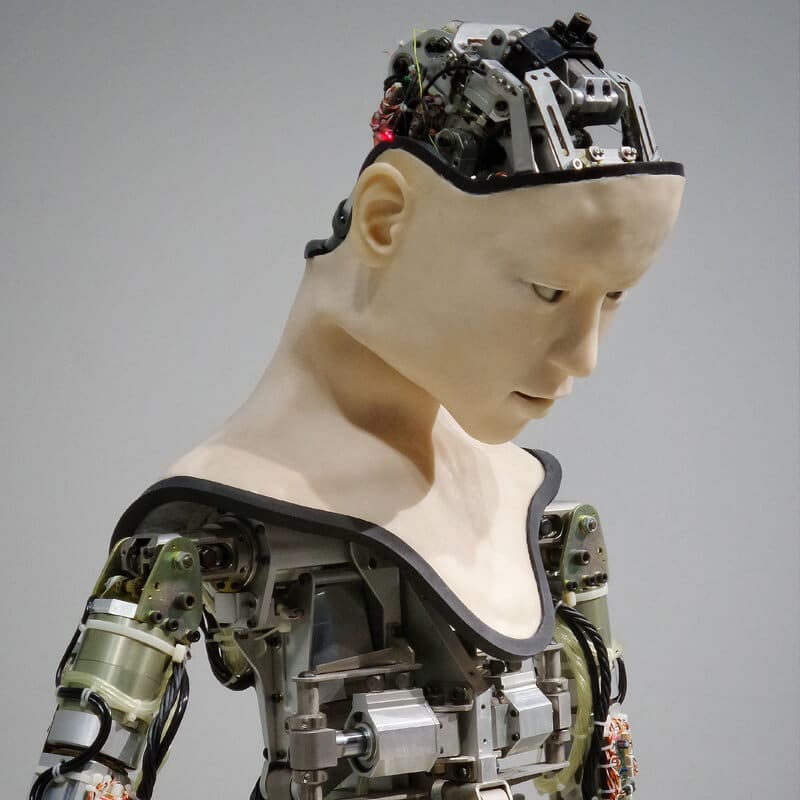

Late last year, Saudi Arabia granted a humanoid robot called Sophia citizenship. The internet went crazy about it, and a number of sensationalised reports suggested that this was the beginning of “the rise of the robots”.

In reality, though, Sophia was not a “breakthrough” in AI. She was just an elaborate puppet that could answer some simple questions. But the debate Sophia provoked about what rights robots might have in the future is a topic that is being explored by an emerging philosophical movement known as post-humanism.

From humanism to post-humanism

In order to understand what post-humanism is, it’s important to start with a definition of what it’s departing from. Humanism is a term that captures a broad range of philosophical and ethical movements that are unified by their unshakable belief in the unique value, agency, and moral supremacy of human beings.

Emerging during the Renaissance, humanism was a reaction against the superstition and religious authoritarianism of Medieval Europe. It wrested control of human destiny from the whims of a transcendent divinity and placed it in the hands of rational individuals (which, at that time, meant white men). In so doing, the humanist worldview, which still holds sway over many of our most important political and social institutions, positions humans at the centre of the moral world.

Post-humanism, which is a set of ideas that have been emerging since around the 1990s, challenges the notion that humans are and always will be the only agents of the moral world. In fact, post-humanists argue that in our technologically mediated future, understanding the world as a moral hierarchy and placing humans at the top of it will no longer make sense.

Two types of post-humanism

The best-known post-humanists, who are also sometimes referred to as transhumanists, claim that in the coming century, human beings will be radically altered by implants, bio-hacking, cognitive enhancement and other bio-medical technology. These enhancements will lead us to “evolve” into a species that is completely unrecognisable to what we are now.

This vision of the future is championed most vocally by Ray Kurzweil, a chief engineer of Google, who believes that the exponential rate of technological development will bring an end to human history as we have known it, triggering completely new ways of being that mere mortals like us cannot yet comprehend.

While this vision of the post-human appeals to Kurzweil’s Silicon Valley imagination, other post-human thinkers offer a very different perspective. Philosopher Donna Haraway, for instance, argues that the fusing of humans and technology will not physically enhance humanity, but will help us see ourselves as being interconnected rather than separate from non-human beings.

She argues that becoming cyborgs – strange assemblages of human and machine – will help us understand that the oppositions we set up between the human and non-human, natural and artificial, self and other, organic and inorganic, are merely ideas that can be broken down and renegotiated. And more than this, she thinks if we are comfortable with seeing ourselves as being part human and part machine, perhaps we will also find it easier to break down other outdated oppositions of gender, of race, of species.

Post-human ethics

So while, for Kurzweil, post-humanism describes a technological future of enhanced humanity, for Haraway, post-humanism is an ethical position that extends moral concern to things that are different from us and in particular to other species and objects with which we cohabit the world.

Our post-human future, Haraway claims, will be a time “when species meet”, and when humans finally make room for non-human things within the scope of our moral concern. A post-human ethics, therefore, encourages us to think outside of the interests of our own species, be less narcissistic in our conception of the world, and to take the interests and rights of things that are different to us seriously.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Big thinker

Science + Technology

Big Thinker: Matthew Liao

Opinion + Analysis

Science + Technology, Business + Leadership, Society + Culture

AI and rediscovering our humanity

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

There’s more than lives at stake in managing this pandemic

Big thinker

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Big Thinker: Dennis Altman

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Ethics Explainer: Social license to operate

Ethics Explainer: Social license to operate

ExplainerBusiness + Leadership

BY The Ethics Centre 23 JAN 2018

Social license – or social license to operate – is a term that has been in usage for almost 20 years. At its simplest, it refers to the acceptance granted to a company or organisation by the community.

Of course anyone running a company would be aware that there are many formal legal and regulatory licenses required to operate a legitimate business. Social license is another thing again: the informal “license” granted to a company by various stakeholders who may be affected by the company’s activities. Such a license is based on trust and confidence – hard to win, easy to lose.

It’s useful to understand that the term “social license to operate” first came into the world in reference to the mining and extractive industries. In an era of heightened awareness of environmental protection and sustainability, the legitimacy of mining was being questioned. It became apparent that the industry would need to work harder to obtain the ongoing broad acceptance of the community in order to remain in business.

To give a simple example: a mining company may be properly registered with all appropriate agencies; it may have a mining license, it may be listed with ASIC and be paying its taxes. It may meet every single obligation under the Fair Work Act. But if the mine is using up precious natural resources without taking due care of the environment or local residents, it will have failed to gain the trust and confidence of the community in which it operates.

Over time, the social license terminology has crossed into the mainstream and is now used to describe the corporate social responsibility of any business or organisation. A whole industry has flourished around Sustainability and Corporate Stakeholder Engagement. And there’s a growing view that social responsibility can be good for long-time financial performance and shareholder value.

The social license to operate is made up of three components: legitimacy, credibility, and trust.

- Legitimacy: this is the extent to which an individual or organisation plays by the ‘rules of the game’. That is, the norms of the community, be they legal, social, cultural, formal or informal in nature.

- Credibility: this is the individual or company’s capacity to provide true and clear information to the community and fulfil any commitments made.

- Trust: this is the willingness to be vulnerable to the actions of another. It is a very high quality of relationship and takes time and effort to create.

The rise of social license can be traced directly to the well-documented erosion of community trust in business and other large institutions. We’re living in an era in which business (or indeed Capitalism itself) is blamed for many of the world’s problems – whether they be climate change, income inequality, modern slavery or fake news. Many perceive globalisation to have had a negative impact on their quality of life.

There’s a growing expectation that businesses – and business leaders – should take a more active role in leading positive change. There’s a belief that business should be working to eliminate harm and maximise benefits – not just for shareholders or customers, but for everyone. To do this, business would be actively engaging with stakeholders, including the most outspoken or marginalised voices; they should be prepared to listen, and reflect, on the concerns of these often powerless individuals.

There is no simple list of requirements that have to be met in order to be granted a social licence to operate.

Too often, social licence is thought to be something that can be purchased, like an offset. Big companies with controversial practices often give out community grants and investments. Clubs that profit from addictive poker machines provide sports gear for local teams and inexpensive meals for pensioners. Tax minimisers set up foundations; soft drink companies fund medical research.

Here a social licence to operate might be seen as a kind of transaction where community acceptance can be bought. Of course, such an approach will often fail precisely because it is conceived as a calculated and cynical pay-off.

The effective co-existence of businesses and individuals within a community requires the development of rich and enduring relationships based on mutual respect and understanding. That sounds like something we’ll all need to work on.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Reports

Business + Leadership

Thought Leadership: Ethics in Procurement

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

‘Woke’ companies: Do they really mean what they say?

Opinion + Analysis

Science + Technology, Business + Leadership

Ask an ethicist: Should I use AI for work?

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Risky business: lockout laws, sharks, and media bias

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Ethics Explainer: Tolerance

For some people, the value of tolerance is simply the opposite of intolerance. But to think of tolerance in simple binary terms limits our understanding of important aspects of the concept.

We gain greater insight if we consider tolerance as the midpoint on a spectrum ranging between prohibition at one end to acceptance at the other:

Prohibition ————— Tolerance ————— Acceptance

The Ancient Greek philosopher Aristotle called this middle point of the spectrum, the golden mean. Approaching tolerance this way, makes it what philosophers call a virtue – the characteristic between two vices.

For example, Aristotle places the virtue of courage at the midpoint (or golden mean) between cowardice and recklessness. So, a courageous person has a proper appreciation of the danger to be faced but stands steadfast and resolute all the same.

Cowardice ————— Courage ————— Recklessness

Although Aristotle’s doctrine of the golden mean can help us understand tolerance, quite a bit more needs to be said. Some things deserve to be rejected and prohibited. And some things ought to be accepted.

We should neither accept or tolerate behaviour that denies the intrinsic dignity of people – for example, the defiling of synagogues by anti-Semites. Instead, we should have a general acceptance and respect for everyone’s intrinsic dignity. People should neither be rejected nor merely tolerated.

Unacceptance ≠ Prohibition

However, there are some things you might reasonably not accept, yet not want to prohibit. This is typically the case when you encounter an idea, custom or practice that is either unfamiliar or at odds with your own convictions about what makes for a good life.

For example, a vegetarian might be convinced it is wrong to eat animals. Such a person may never accept the practice as part of their own life. However, they may not want to stop others eating meat. Instead, they will tolerate other people’s consumption of animals.

This reveals an essential aspect of tolerance. Toleration is always a response to something that is disapproved of – but not to such a degree as to justify prohibition. Tolerance is, by definition, a mark of disapproval.

And so some people seek from society something more than ‘mere tolerance’. Instead, they look for acceptance.

Tolerance to acceptance

The word ‘acceptance’ rang out loud when it was revealed a majority of Australian voters answered yes to the same sex marriage postal survey in 2017. For gay and lesbian couples, the result is evidence of wide acceptance of their equality as citizens.

Individuals and communities are not only entitled to think about what should be accepted, tolerated or prohibited. We can also be obliged to consider these things.

Without wanting to confuse ethical with legal obligations, this is the difficult task of parliaments. To continue with the same sex marriage example in Australia, they were obliged to consider what behaviours should be accepted, tolerated, or prohibited in terms of wedding services and religious freedoms.

The ethics of tolerance

Ethics calls upon people to examine their lives – including the quality of their reasons when forming judgements. An ethical life is one that goes beyond unthinking custom and practice. This is why judgements about what is to be accepted, tolerated or prohibited need to be made free from the distorting effects of prejudice. Beliefs, customs and institutions should be evaluated for what they actually are – and not on the basis of assumptions about people or the world. The quality of our judgment matters.

There can be sincere disagreement among people of good will. Respect for persons – and the general acceptance this requires – can sit alongside ‘mere’ tolerance of each other’s foibles.

And that may be the best we should hope for.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Come join the Circle of Chairs

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing

Want your kids to make good decisions? Here’s what they need to learn

Explainer

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Dignity

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Health + Wellbeing, Society + Culture

Ethical concerns in sport: How to solve the crisis

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Ethics Explainer: Conscience

Conscience describes two things – what a person believes is right and how a person decides what is right. More than just ‘gut instinct’, our conscience is a ‘moral muscle’.

By informing us of our values and principles, it becomes the standard we use to judge whether or not our actions are ethical.

We can call these two roles ethical awareness and ethical decision making.

Ethical Awareness

This is our ability to recognise ethical values and principles.

The medieval philosopher Thomas Aquinas believed our conscience emerged from synderesis: the ‘spark of conscience’. He literally meant the human mind’s ability to understand the world in moral terms. Conscience was the process by which a person brought the principles of synderesis into a practical situation through our decisions.

Ethical Decision Making

This is our ability to make practical decisions informed by ethical values and principles.

In his writings, Aristotle described phronesis: the goodness of practical reason. This was the ability to evaluate a situation clearly so we would know how to act virtuously under the circumstances.

A conscience which is both well formed (shaped by education and experience) and well informed (aware of facts, evidence and so on) enables us to know ourselves and our world and act accordingly.

Seeing conscience in this way is important because it teaches us ethics is not innate. By continuously working to understand our surroundings, we strengthen our moral muscle.

Conscientious Objection

In politics, much of the debate around conscience concerns the “right to conscientious objection”.

- Should pro-life doctors be required to perform abortions or refer patients to doctors who will?

- Must priests break the confessional seal and report sex offenders who confess to them?

- Can pacifists be excused from conscription because of their opposition to war?

For a long time, Western nations, informed by the Catholic intellectual tradition, believed in the “primacy of conscience” – the idea that a person should never be forced to do something they believe is against their most deeply held values and principles.

In recent times, particularly in medicine, this has come to be questioned. Australian bioethicist Julian Savulescu believes doctors working in the public system should be banned from objecting to procedures because it compromises patient care.

This debate sees a clash between two worldviews – one where people’s foremost responsibility is to their own personal beliefs about what is good and right and another where this duty is balanced against the needs of the common good.

Philosopher Michael Walzer believes there are situations where you have a duty to “get your hands dirty” – even if the price is your own sense of goodness. In response, Aristotle might have said, “no person wishes to possess the world if they must first become someone else”. That is, we can’t change who we are or what we believe in for any price.

Recommended viewing

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

The wonders, woes, and wipeouts of weddings

Opinion + Analysis

Climate + Environment, Politics + Human Rights, Relationships, Society + Culture

The youth are rising. Will we listen?

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

When are secrets best kept?

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

I’m really annoyed right now: ‘Beef’ and the uses of anger

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Ethics Explainer: Progressivism

Progressivism is a political ideology based on the possibility of moral progress. In practice, this looks like an optimism about the future of humanity.

Progressives believe the course of human history is moving us closer to a state of peace, equality, and prosperity. They also tend to believe in human perfectibility. Politics, technology, and education can overcome human failings to create a utopia.

We can see this in the work of philosophers Steven Pinker and Michael Shermer. Pinker says since the Enlightenment, altruism has been on the rise and violence is declining around the world. Shermer suggests each generation has been smarter than the last, which he believes, has continually reduced impulsive violence.

Hegel’s synthesis

German philosopher Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel believed moral progress was inescapable. He thought the forces of history shape humanity for the better, pushing it toward perfection.

Hegel believed history unrolled according to a “dialectical” pattern. This was where opposing sides clashed and compromised with one another. These opposing forces, which he called the “thesis” and “antithesis”, would clash before reaching a “synthesis”.

This synthesis would then spark a new antithesis and the process would continue. Hegel thought each stage in the thesis-antithesis-synthesis series moved us closer to a state of perfection. His work is said to have inspired other progressive thinkers, most notably communist philosopher Karl Marx.

The darker side of progress

Today, new forms of genetic editing promise a cure to a range of illnesses and maybe even death itself. Transhumanists believe we can overcome the limitations of our humanity and mortality. They suggest a range of options, from changing our biology to uploading our consciousness into a supercomputer.

But practical efforts to create this perfect world have not always been pleasant. At times it has been outright barbaric.

One example is the eugenics movement. It aimed to breed some people, like those with disabilities, out of society altogether, and cited social progress as their defence.

This is one reason why conservatives often urge caution around progress. They encourage us to be mindful of the potential unintended side effects of new policies or technology.

But progressives are often concerned this will inhibit life changing new developments. They suggest we deal with issues as they arise, rather than trying to predict them in advance.

Heaven on earth

Progressives often see education as the silver bullet solution for social problems. Like Ancient Greek philosopher Socrates, they tend to believe all vice is the result of ignorance, not malice. They suggest humans are fundamentally good and education will bring out the better angels of our nature.

But some are sceptical whether education alone will fix all humanity’s woes. They agree humans are mostly good but don’t blame ignorance for evil. Instead, they see war, conflict and violence as the product of oppression and inequality.

Karl Marx believed conflict between the wealthy and the working class was a central theme in human society. He believed the power imbalance between rich and poor was bad for everyone. He famously claimed people would be better throwing away hierarchies based on class and wealth. Only when we’re all equal, he thought, will we be able to perfect ourselves.

English philosopher Mary Wollstonecraft suggested the path to human perfection might require both politics and education. She argued that political change requires us to educate marginalised groups. Otherwise, any change will continue to exclude the groups already on the fringes of society.

This explains why more women and culturally diverse people have contributed to progressive thinking in recent decades. In the past, the leading progressive thinkers tended to be white men. Improved access to education has enabled a greater range of voices to contribute to the larger conversation of what a perfect world might look like and how we could create it.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

After Christchurch

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Philosophy must (and can) thrive outside universities

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Your child might die: the right to defy doctors orders

Explainer

Relationships, Society + Culture