Ethics Explainer: Moral Courage

Ethics Explainer: Moral Courage

ExplainerSociety + CulturePolitics + Human Rights

BY The Ethics Centre 29 APR 2025

Martin Luther King Jr, Rosa Parks, Frederick Douglass, Susan B. Anthony, Greta Thunberg, Vincent Lingiari, Malala Yousafzai.

For most, these names, and many more, evoke a sense of inspiration. They represent decades and centuries of steadfast moral conviction in the face of overwhelming national and global pressure.

Rosa Parks, risking the limited freedom she was afforded in 1955 America, refused to acquiesce to the transit segregation of the time and sparked an unprecedented boycott led by Martin Luther King Jr.

Frederick Douglass, risking his uncommon position of freedom and power as a Black man in pre-civil rights America, used his standing and skills to advocate for women’s suffrage.

There have always been people who have acted for what they think is right regardless of the risk to themselves.

This is moral courage. The ability to stand by our values and principles, even when it’s uncomfortable or risky.

Examples of this often seem to come in the form of very public declarations of moral conviction, potentially convincing us that this is the sort of platform we need to be truly morally courageous.

But we would be mistaken.

Speaking up doesn’t always mean speaking out

Having the courage to stand by our moral convictions does sometimes mean speaking out in public ways like protesting the government, but for most people, opportunities to speak up manifest in much smaller and more common ways almost every day.

This could look like speaking up for someone in front of your boss, questioning a bully at school, challenging a teacher you think has been unfair, preventing someone on the street from being harassed or even asking someone to pick up their litter.

In each case, an everyday occurrence forces us to confront discomfort, and potentially danger or loss, to live out our values and ideals. Do we have the courage to choose loyalty over comfort? Honesty over security? Justice over personal gain?

The truth is that sometimes we don’t.

Sometimes we fail to take responsibility for our own inaction. Nothing shows this better than the bystander effect: functionally the direct opposite to moral courage, the bystander effect is a social phenomenon where individuals in group or public settings fail to act because of the presence of others. Being surrounded by people causes many of us to offload responsibility to those around us, thinking: “Someone else will handle it.”

This is where another kind of moral courage comes into play: the ability to reflect on ourselves. While it’s important to learn how and when to speak up, some internal work is often needed to get there.

Self-reflection is often underestimated. But it’s one of the hardest aspects of moral courage: the willingness to confront and interrogate our own thoughts, habits, and actions.

If someone says something that makes you uncomfortable, the first step of moral courage is acknowledging your discomfort. All too often, discomfort causes us to disengage, even when no one else is around to pass responsibility onto. Rather than reckon with a situation or person who is challenging our values or principles, we curl up into our shells and hope the moment passes.

This is because moral courage can be – it takes time and practice to build the habits and confidence to tolerate uncomfortable situations. And it takes even more time and practice to prioritise what we think is right with friends, family and colleagues instead of avoiding confrontation in relationships that are already often complicated.

It can get even more complicated once we consider all of our options because sometimes the right ways to act aren’t obvious. Sometimes, the morally courageous thing to do is actually to be silent, or to walk away, or to wait for a better opportunity to address the issue. These options can feel, in the moment, akin to giving up or letting someone else ‘win’ the interaction. But that is the true test of moral courage – being able to see the moral end goal and push through discomfort or challenge to get there.

The courage to be wrong

The flipside to self-reflection is the ability to recognise, acknowledge and reflect with grace when someone speaks up against us.

It’s hard to be told that we’re wrong. It’s even harder to avoid immediately placing walls in our own defence. Overcoming that is the stuff of moral courage too – not just being able to confront others, but being able to confront ourselves, to question our understanding of something, our actions or our beliefs when we are challenged by others.

Whether these changes are worldview-altering, or simply a swapping of word choice to reflect your respect for others, the important thing is that we learn to sit with discomfort and listen. Listen to criticism but also listen to our own thoughts and figure out why our defences are up.

Because in the end, moral courage isn’t just about bold public stands. It’s about showing up—in big moments and more mundane ones—for what’s right. And that begins with the courage to face ourselves.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Explainer

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Autonomy

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Science + Technology

Ukraine hacktivism

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

Meet Dr Tim Dean, our new Senior Philosopher

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture

We need to step out of the shadows in order to navigate a complex world

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Thought experiment: The original position

Thought experiment: The original position

ExplainerSociety + CulturePolitics + Human Rights

BY The Ethics Centre 20 MAR 2025

If you were tasked with remaking society from scratch, how would you decide on the rules that should govern it?

This is the starting point of an influential thought experiment posed by the American 20th century political philosopher, John Rawls, that was intended to help us think about what a just society would look like.

Imagine you are at the very first gathering of people looking to create a society together. Rawls called this hypothetical gathering the “original position”. However, you also sit behind what Rawls called a “veil of ignorance”, so you have no idea who you will be in your society. This means you don’t know whether you will be rich, poor, male, female, able, disabled, religious, atheist, or even what your own idea of a good life looks like.

Rawls argued that these people in the original position, sitting behind a veil of ignorance, would be able to come up with a fair set of rules to run society because they would be truly impartial. And even though it’s impossible for anyone to actually “forget” who they are, the thought experiment has proven to be a highly influential tool for thinking about what a truly fair society might entail.

Social contract

Rawls’ thought experiment harkens back to a long philosophical tradition of thinking about how society – and the rules that govern it – emerged, and how they might be ethically justified. Centuries ago, thinkers like Thomas Hobbes, Jean-Jacques Rousseau and John Lock speculated that in the deep past, there were no societies as we understand them today. Instead, people lived in an anarchic “state of nature,” where each individual was governed only by their self-interest.

However, as people came together to cooperate for mutual benefit, they also got into destructive conflicts as their interests inevitably clashed. Hobbes painted a bleak picture of the state of nature as a “war of all against all” that persisted until people agreed to enter into a kind of “social contract,” where each person gives up some of their freedoms – such as the freedom to harm others – as long as everyone else in the contract does the same.

Hobbes argued that this would involve everyone outsourcing the rules of society to a monarch with absolute power – an idea that many more modern thinkers found to be unacceptably authoritarian. Locke, on the other hand, saw the social contract as a way to decide if a government had legitimacy. He argued that a government only has legitimacy if the people it governs could hypothetically come together to agree on how it’s run. This helped establish the basis of modern liberal democracy.

Rawls wanted to take the idea of a social contract further. He asked what kinds of rules people might come up with if they sat down in the original position with their peers and decided on them together.

Two principles

Rawls argued that two principles would emerge from the original position. The first principle is that each person in the society would have an equal right to the most expansive system of basic freedoms that are compatible with similar freedoms for everyone else. He believed these included things like political freedom, freedom of speech and assembly, freedom of thought, the right to own property and freedom from arbitrary arrest.

The second principle, which he called the “difference principle”, referred to how power and wealth should be distributed in the society. He argued that everyone should have equal opportunity to hold positions of authority and power, and that wealth should be distributed in a way that benefits the least advantaged members of society.

This means there can be inequality, and some people can be vastly more wealthy than others, but only if that inequality benefits those with the least wealth and power. So a world where everyone has $100 is not as just as a world where some people have $10,000, but the poorest have at least $101.

Since Rawls published his idea of the original position in A Theory of Justice in 1972, it has sparked tremendous discussion and debate among philosophers and political theorists, and helped inform how we think about liberal society. To this day, Rawls’ idea of the original position is a useful tool to think about what kinds of rules ought to govern society.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

If politicians can’t call out corruption, the virus has infected the entire body politic

Big thinker

Politics + Human Rights, Society + Culture

Big Thinker: Slavoj Žižek

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

The erosion of public trust

READ

Society + Culture

6 dangerous ideas from FODI 2024

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Ethics Explainer: Just Punishment

Ethics Explainer: Just Punishment

ExplainerSociety + CulturePolitics + Human Rights

BY The Ethics Centre 6 DEC 2024

In 2001, Marcellus Williams was convicted of killing Felicia Gayle, found stabbed to death in her home in 1998.

Over two decades later, he was given the death penalty, directly against the wishes of the prosecutor, the jury and, notably, Gayle’s family.

Cases like this draw our attention to the nature of punishment and its role in delivering justice. We can think about justice, and hence what is just punishment, as a question about what we deserve. But who decides what we deserve, and on what basis?

There are many ways that people think about punishment, but generally it’s justified in some variation of the following: retribution, deterrence, rehabilitation, and/or restoration. These are not all mutually exclusive ideas either, but rather different arguments about what should be the primary purpose and mode of punishment

Purposeful Punishment

Punishment is often viewed through the lens of retribution, where wrongdoers are punished in proportion to their offenses. The concept of retributive justice is grounded in the idea that punishment restores balance in society by making offenders ‘pay’ in various ways, like prison time or fines, for their transgressions.

This perspective is somewhat intuitive for most people, as it’s reflected in our moral psychology. When we feel wronged, we often become outraged. Outrage is a moral emotion that often inspires thoughts of harming the wrongdoer, so retributive punishment can feel intuitively justified for many. And while it has roots in our evolutionary psychology, it can also be a harmful disposition to have in a modern context.

The 18th-century philosopher Immanuel Kant strongly defended retributive justice as a matter of principle, much like his general deontological moral convictions. Kant believed that people who commit crimes deserve to be punished simply because they have done wrong, irrespective of whether it leads to positive social outcomes. In his view, punishment must fit the crime, upholding the dignity of the law and ensuring that justice is served.

However, there are many modern critics of retributivism. Some argue that focusing solely on punishment in a retributive way overlooks the possibility of rehabilitation and societal reintegration. These criticisms often come from a consequentialist approach, focusing on how to create positive outcomes.

One of these is an ongoing ethical debate about the role of punishment as a deterrent. This is a consequentialist perspective that suggests punishment should aim to maximise social benefits by deterring future crimes. This view is often criticised because of its implications on proportionality. If punishment is used primarily as a deterrent, there is a high risk that people will be punished more harshly than their crimes warrant, merely to serve as an example. This approach can conflict with principles of fairness and proportionality that are central to most conceptions of justice. Some also consider it to be a view that misunderstands the motives and conditions that surround and cause common crime.

Other, more contemporary, consequentialist views on punishment focus on rehabilitation and restoration. Feminist philosophers, such as Martha Nussbaum, have proposed a broader, more compassionate view of justice that emphasises human dignity. Nussbaum suggests that a purely punitive system dehumanises offenders, treating them merely as vessels for punishment rather than as individuals with the capacity for moral growth and change.

They argue that this dehumanisation is a primary factor in high rates of recidivism, as it perpetuates the cycle of disadvantage that often underpins crime. Hence, an ability for change and reintegration is seen by some as crucial to developing pro-social methods of justice that decrease recidivism.

Importantly, these views are not inherently at odds with traditional punishment, like prison. However, they are critical of the way that punishment is enacted. To be in line with rehabilitative methods, prisons in most countries worldwide would need to see a significant shift towards models that respect the dignity of prisoners through higher quality amenities, vocations, education, exercise and social opportunities.

One unintuitive and hence potentially difficult aspect of these consequentialist perspectives is that in some cases punishment will be deemed altogether unnecessary. For example, if a wrongdoer is found to be impaired significantly by mental illness (e.g. dementia) to the extent that they have no memory or awareness of their wrongdoing, some would claim that any type of retributive punishment is wrong, as it serves no purpose aside from satisfying outrage. This can be a difficult outcome to accept for those who see punishment as needing to “even the scales”.

Justice and Punishment

The ethical implications of punishment become even more complex when considering factors like bias and the reality of disproportionate sentencing. For example, marginalised groups face more scrutiny and harsher sentences for similar crimes, both in Australia and globally. This disparity is often unconscious, resulting in a denial of responsibility at many steps in the system and a resistance to progress.

If punishment is disproportionately applied to disadvantaged groups, then it is not just. The ethical demand of justice is for equal treatment, where punishment reflects the crime, not the social status or identity of the offender.

Whether our idea of punishment involves revenge or benevolence, it’s important to understand the motivations behind our convictions. All the sides of the punishment spectrum speak to different intuitions we hold, but whether we are steadfast in our right to get even, or we believe an eye for an eye leaves the whole world blind, we must be prepared to find the nuance for the betterment of us all.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture

Ethics programs work in practise

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

Meet Daniel, helping us take ethics to the next generation

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

A note on Anti-Semitism

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture, Politics + Human Rights

Taking the cynicism out of criticism: Why media needs real critique

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Ethics explainer: The principle of charity

The principle of charity suggests we should assume good intentions about others and their ideas, and give them the benefit of the doubt before criticising them.

British philosopher and mathematician, Bertrand Russell, was one of the sharpest minds of his generation. Anyone deigning to offer a lecture in his presence at Cambridge University was sure to have every iota of their reasoning scrutinised and picked apart in excruciating detail.

Yet, it’s said that before criticising arguments, Russell would thank them warmly for sharing their views, then he might ask a question or two of clarification, then he’d summarise their position succinctly – often in more concise and persuasive terms than they themselves had used – and only then would he expose its flaws.

What Russell was demonstrating was the principle of charity in action. This is not a principle about giving money to the poor, it’s about assuming good intentions and giving others the benefit of the doubt when we interpret what they’re saying.

The reason we need charity when listening to others is that they rarely have the opportunity to say everything they need to say to support their view. We only have so many minutes in the day, so when we want to make an assertion or offer an argument, it’s simply not possible to account for every assumption, outline every implication and cover off all possible counterarguments.

That means there will inevitably be things left unsaid. Given our natural propensity to experience disagreement as a form of conflict, and thus shift into a defensive posture to protect our ideas (and, sometimes, our identity), it’s all too easy for us to fill in the gaps with less than charitable interpretations. We might assume the person speaking is ignorant, foolish, misled, mean spirited or riddled with vice, and fill the gaps with absurd assertions or weak arguments that we can easily dismantle.

We also have to decide whether they are speaking in good faith, or whether they’re just engaging in a bit of virtue signalling and didn’t really mean to offer their views up for scrutiny, or whether they’re trying to troll us. Again, it’s all too easy to allow our suspicions or defensiveness to take over and assume someone is speaking with ill intent.

However, doing so does them – and us – a disservice. It prevents us from understanding what they’re actually trying to say, and it blocks us from either being persuaded by a good point or offering a valid criticism where one is due. Failing to offer charity is also a sign of disrespect. And it’s well known that when people feel disrespected, they’re even more likely to double down on their defensiveness and fight to the bitter end, even if they might otherwise have been open to persuasion.

It’s probably no surprise to hear that the internet is a hotbed of uncharitable listening. Many people have been criticised, dismissed, attacked or cancelled because they have said or done something ambiguous – something that could be interpreted in either a benign or a negative light. Some commentators on social media are all too ready to uncharitably interpret these actions as revealing some hidden malice or vice, and they leap to condemnation before taking the time to unpack what the speaker really meant.

Charity requires more from us, but the rewards can be great. Charity starts by assuming that the person speaking is just as informed, intelligent and virtuous as we are – or perhaps even more so. It encourages us to assume that they are speaking in good faith and with the best of intentions.

It requires us to withhold judgement as we listen to what’s being said. If there are things that don’t make sense, or gaps that need filling, charity encourages us to ask clarificatory questions in good faith, and really listen to the answers. The final step is to repeat back what we’ve heard and frame it in the strongest possible argument, not the weakest “straw man” version. This is sometime referred to as a “steel man”.

Doing this achieves two things. First, the speaker will feel heard and respected. That immediately puts the relationship on a positive stance, where everyone feels less need to defend themselves at all costs, and it can make people open to listening to alternative viewpoints without feeling threatened.

Secondly, it gives you a fighting chance of actually understanding what the other person really believes. So many conversations end up with us talking past each other, getting more frustrated by the minute. Arriving at a point of mutual understanding can be a powerful way to connect with someone and have an actually fruitful discussion.

It is important to point out that exercising charity doesn’t mean agreeing with whatever other people say. Nor does it mean excusing statements that are false or harmful.

Charity is about how we hear what is being said, and ensuring that we give the things we hear every possibility to convince us before we seek to rebut them.

However, if we have good reason to believe that what they’re saying, after we’ve fully understood it in its strongest possible form, is false or harmful, then we need not agree with them. Indeed, we ought to speak out against falsehood and harm whenever possible. And this is where exercising charity, and building up respect, might make others more receptive to our criticisms, as were many of the people who gave a lecture in the presence of Bertrand Russell.

The principle of charity doesn’t come naturally. We often rail against views that we find ridiculous or offensive. But by practising charity, we can have a better chance of understanding what people are saying and of convincing them of the flaws in their views. And, sometimes, by filling in the gaps in what others say with the strongest possible version of their argument, we might even change our own mind from time to time.

This article has been updated since its original publication on 10 March 2017.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

When identity is used as a weapon

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Ask an ethicist: How do I get through Christmas without arguing with my family about politics?

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Teleology

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

In two minds: Why we need to embrace the good and bad in everything

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Ethics Explainer: Cancel Culture

When mass outrage is weaponised and encouraged, it can become more of a threat to the powerless than to those it’s intended to hold to account.

In 2017, comedian Louis C.K. was accused of several instances of sexual misconduct, to which he later admitted in full. This was followed by a few cancelled movies, shows and appearances before he stepped away from public life for a few years.

In 2022, lecturer Ilya Shapiro was put on leave following a tweet he posted a few days before he was employed. Shapiro contended that the university failed in its commitment to free expression by investigating his actions for four months, before reinstating him under the reason that he was not accountable to the university for actions taken before his employment started.

These are both instances of what some people would call “cancel culture”, yet they involve very different issues. To unpack them, we first need to define what we mean by cancel culture.

From around 2015 onwards, the term started gaining mainstream traction, eventually being named Word of the Year by Macquarie Dictionary in 2019:

“The attitudes within a community which call for or bring about the withdrawal of support from a public figure, such as cancellation of an acting role, a ban on playing an artist’s music, removal from social media, etc., usually in response to an accusation of a socially unacceptable action or comment by the figure.”

The quintessential examples of cancel culture are calls from groups of people online for various public figures to be stripped of support, their work boycotted, or their positions removed following perceived moral transgressions. These transgressions can be anything from a rogue tweet to sexual assault allegations, but the common theme is that they are deemed to be harmful and warrant some kind of reaction.

A notoriously contentious concept, cancel culture is defined, or at least perceived, differently based on the social, cultural and political influences of whom you ask. Though its roots are in social justice, some believe that it lacks the nuance needed to meet the ends it claims to serve, and it has been politicised to such an extent that it has become almost meaningless.

Defenders of accountability

The ethical dimensions of this phenomenon become clear when we look at the various ways that cancel culture is understood and perceived by different groups of people. Where some people see accountability, others see punishment.

Defenders of cancel culture, or even those who argue that it doesn’t exist, say that what this culture really promotes is accountability. While there are examples of celebrities being shamed for what might be conceived as a simple faux pas, they say that the intent of most people who engage in this action is for powerful to be held accountable for words and actions that are deemed seriously harmful.

This usually involves calls to boycott, like the ongoing attempts to boycott J.K. Rowling’s books, movies and derivative games and shows because of her vocal criticism of transgender politics since 2019, or like the many attempts to discourage people from supporting various comedians because of issues ranging from discriminatory sets to sexual misconduct and harassment.

Those who view cancel culture practices as modes of justice feel that these are legitimate responses to wrongdoings that help to hold people with power accountable and discourage further abuses of power.

In the case of Louis C.K., it was widely viewed that his sexual misconduct warranted his shunning and removal from upcoming media productions.

Public figures are not owed unconditional support.

While it’s not clear that this kind of boycotting does anything significant to remove any power from these people (they all usually go on to profit even further from the controversy), it’s difficult to argue that this sort of action is unethical. Public figures are in their positions because of the support of the public and it could be considered a violation of the autonomy we expect as human beings to say that people should not be allowed to withdraw that support when they choose.

Where this gets sticky, even for supporters of cancel culture, is when people with relatively little power become the targets of mass social pressure. This can lead to employers distancing themselves from the person, sometimes ending in job loss, to protect the organisation’s reputation. This is disproportionately harmful for disadvantaged people who don’t have the power or resources to ignore, fight, or capitalise on the attention.

This is an even further problem when we consider how it can cause a sense of fear to creep into our everyday relationships. While people in power might be able to shrug off or shield themselves from mass criticism, it’s more difficult for the average person to ignore the effects of closed or uncharitable social climates.

When people perceive a threat of being ostracised by friends, family or strangers because of one wrong step they begin to censor themselves, which leads to insular bubbles of thoughts and ideas and resistance to learning through discussion.

Whether this is a significant active concern is still unclear, though there is some evidence that it is an increasing phenomenon.

Defenders of free speech

Given this, it’s no surprise that the prevailing opposition to cancel culture is framed as a free speech and censorship issue, viewed by detractors as an affront to liberty, constructive debate, social and even scientific progress

Combined with this is a contention that cancelling someone is often a disproportionate punishment and therefore unjust – with people sometimes arguing that punishment wasn’t warranted at all. As we saw earlier, this is particularly a problem when the punishments are directed at disadvantaged, non-public figures, though this position often overstates the effect the punishments have on celebrities and others in significant power.

A problem with the claim that cancel culture is inherently anti-free speech is that, especially when applied to celebrities, it relies on a misconception that a right to free speech entails a right to speak uncontested or entitlement to be platformed.

In fact, similar to boycotting people we disagree with, publicly voicing concerns with the intention of putting pressure on public figures is an exercise in free speech itself.

Accountable free speech

An important way forward for both sides of issue is the recognition that while free speech is important, the limits of it are equally so.

One way we can do this is by emphasising the difference between bad faith and good faith discussion. As philosopher Dr Tim Dean has said, not all speech can or should be treated equally. Sometimes it is logical and ethical to be intolerant of intolerance, especially the types of intolerance that use obfuscating and bad faith rhetoric, to ensure that free speech maintains the power to seek truth.

Focusing on whether a discussion is being had in bad faith or good faith can differentiate public and private discourse in a way that protects the much-needed charitability of conversations between friends and acquaintances.

While this raises questions, like whether public figures should be held to a higher standard, it does seem intuitive and ethical to at least assume the best of our friends and family when having a discussion. We are in the best place to be charitable with our interpretations of their opinions by virtue of our relationships with them, so if we can’t hold space for understanding, respectful disagreement and learning, then who can?

Another method for easing the pressures that public censures can have on private discourse is by providing and practicing clear ways to publicly forgive. This provides a blueprint for people to understand that while there will be consequences for consistent or shameless moral transgressions, there is also room for mistakes and learning.

For a deeper dive on Cancel Culture, David Baddiel, Roxane Gay, Andy Mills, Megan Phelps-Roper and Tim Dean present Uncancelled Culture as part of Festival of Dangerous Ideas 2024. Tickets on sale now.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture, Politics + Human Rights

Freedom of expression, the art of…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights, Society + Culture

Drawing a line on corruption: Operation eclipse submission

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture

Why are people stalking the real life humans behind ‘Baby Reindeer’?

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture

FODI digital returns for three dangerous conversations

Ethics Explainer: WEIRD ethics

If you come from a Western, Educated, Industrialised, Rich and Democratic society, then you’re WEIRD. And if you are, you might think about ethics differently than a majority of people alive today.

We all assume that we’re normal (to at least some degree). And it’s natural to assume everyone else sees the world at least somewhat similarly to the way we do. This is such a pervasive phenomenon that even psychology researchers have fallen into this trap, and it has influenced the way they have conducted their studies and the conclusions they have drawn about human nature.

Many psychology studies purport to investigate universal features of the human mind using a representative sample of people. However, the problem is that these samples are not typical of humans. The usual test subject in a psychology study is drawn from a very narrow pool, with around 80 percent being undergraduate students attending a university in the United States or another Western country.

If human psychology really was universal, this selection bias wouldn’t matter. But it turns out our minds don’t all work alike, and culture plays a huge role in shaping how we think. Even features of our minds that were once believed to be universal, such as depth perception, vary from one culture to another. For example, American undergraduate students are far more likely to see the two lines in the classic Muller-Lyer illusion as being significantly different lengths, whereas San forages of the Kalahari in southern Africa are virtually immune to the illusion.

But it’s not just perception that varies among cultures. It’s also the way we think about right and wrong, which has serious ramifications for how we answer ethical questions.

WEIRD ethics

Imagine you and a stranger are given $100 to split between you. However, there’s a catch. The stranger gets to decide how much of the $100 to offer you and what proportion they get to keep. They could split it 50:50, or 90:10. It’s all up to them. If you accept their offer, then you both get to keep your respective proportions. But if you reject the offer, you both get nothing.

Now imagine they offered you $50. Would you accept? It turns out that most people from Western countries would. But what if they offer you $10, so they get to keep $90? Most WEIRDos would reject this offer, even if it means they miss out on a “free” $10. One way to look at this is that WEIRD subjects were willing to incur a $10 cost to “punish” the other for being unfair.

This is called the Ultimatum Game, and it’s much studied in psychology and economics circles. For quite some time, researchers believed it showed that people are naturally inclined to offering a fair split, and recipients were naturally willing to punish those who offered an unfair amount.

However, repeated experiments have since shown that this is largely a WEIRD phenomenon, and individuals from non-WEIRD cultures, particularly from small-scale societies, behave very differently. People from these cultures were far more likely to offer a smaller proportion to their partner, and the recipients were far more likely to accept low offers than people from WEIRD cultures.

So, instead of revealing some universal sense of fairness, what the Ultimatum Game did was reveal how different cultures, and different social norms, shape the way people think about fairness and punishment. Far from being universal, it turns out that much of our thinking about fairness is a product of the culture in which we were raised.

It’s conventional

Another fascinating discovery that emerged from comparing WEIRD with non-WEIRD populations was that different cultures think about ethics in very different ways.

Research by Lawrence Kohlberg in the United States in the 1970s uncovered patterns in how children develop their moral reasoning abilities as they age. Most children start off viewing right and wrong in purely self-interested terms – they do the right thing simply to avoid punishment. The next stage sees children come to understand that moral norms keep society functioning smoothly, and do the right thing to maintain social order. The third stage of development goes beyond social conventions and starts to appeal to abstract ethical principles about things like justice and rights.

While these stages have been observed in most WEIRD populations, cross-cultural studies have found that non-WEIRD people from small-scale societies don’t tend to exhibit the final stage, with them sticking to conventional morality. And this has nothing to do with lack of education, as even university professors in non-WEIRD societies show the same pattern of moral thinking.

So, rather than showing clear stages of moral development, Kohlberg’s research just revealed something unique about WEIRD people, and their cultural emphasis on autonomy, while many other societies emphasise community or divinity as the basis of ethics.

Who are you?

The research on WEIRD psychology, has led to a significant shift in the way that psychologists and philosophers think about morality. On the one hand, it has shown that many of our assumptions about human universals in moral thinking are strongly influenced by our own cultural background. And on the other, it has shown that morality is a hugely more diverse landscape than was often assumed by WEIRD philosophers.

It has also caused many people to reflect on their own cultural influences, and pause to realise that their perspective on many important ethical issues might not be shared by a majority of people alive today. That doesn’t mean that we should lapse into a kind of anything-goes moral relativism, but it does encourage us to exercise humility when it comes to how certain we are in our attitudes, and also seek strong reasons to support our ethical views beyond just appealing to the contingencies of our upbringing.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships, Society + Culture

Renewing the culture of cricket

Big thinker

Society + Culture

Big Thinker: Philippa Foot

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

What money and power makes you do: The craven morality of The White Lotus

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

How can you love someone you don’t know? ‘Swarm’ and the price of obsession

Ethics Explainer: Shame

Flushed cheeks, lowered gaze and an interminable voice in your head criticising your very being.

Imagine you’re invited to two different events by different friends. You decide to go to one over the other, but instead of telling your friend the truth, you pretend you’re sick. At first, you might be struck with a bit of guilt for lying to your friend. Then, afterwards, they see photos of you from the other event and confront you about it.

In situations like this, something other than guilt might creep in. You might start to think it’s more than just a mistake; that this lie is a symptom of a larger problem: that you’re a bad, disrespectful person who doesn’t deserve to be invited to these things in the first place. This is the moral emotion of shame.

Guilt says, “I did something bad”, while shame whispers, “I am bad”.

Shame is a complicated emotion. It’s most often characterised by feelings of inadequacy, humiliation and self-consciousness in relation to ourselves, others or social and cultural standards, sometimes resulting in a sense of exposure or vulnerability, although many philosophers disagree about which of these are necessary aspects of shame.

One approach to understanding shame is through the lens of self-evaluation, which says that shame arises from a discrepancy between self-perception and societal norms or personal standards. According to this view, shame emerges when we perceive ourselves as falling short of our own expectations or the expectations of others – though it’s unclear to what extent internal expectations can be separated from social expectations or the process of socialisation.

Other approaches lean more heavily on our appraisal of social expectations and our perception of how we are viewed by others, even imaginary others. These approaches focus on the arguably unavoidably interpersonal nature of shame, viewing it as a response to social rejection or disapproval.

This social aspect is such a strong part of shame that it can persist even when we’re alone. One way to exemplify this is to draw similarity between shame and embarrassment. Imagine you’re on an empty street and you trip over, sprawling onto the path. If you’re not immediately overcome with annoyance or rage, you’ll probably be embarrassed.

But there’s no one around to see you, so why?

Similarly, taking the example we began with, imagine instead that no one ever found out that you lied about being sick. It’s possible you might still feel ashamed.

In both of these cases, you’re usually reacting to an imagined audience – you might be momentarily imagining what it would feel like if someone had witnessed what you did, or you might have a moment of viewing yourself from the outside, a second of heightened self-awareness.

Many philosophers who take this social position also see shame as a means of social control – notably among them is Martha Nussbaum, known for her academic career highlighting the importance of emotions in philosophy and life.

Nussbaum argues that shame is very often ‘normatively distorted’, in that because shame is reactive to social norms, we often end up internalising societal prejudices or unjust beliefs, leading to a sense of shame about ourselves that should not be a source of shame. For example, people often feel ashamed of their race, gender, sexual orientation, or disability due to societal stigma and discrimination.

Where shame can go wrong

The idea of shame as a prohibitive and often unjust feeling is a sentiment shared by many who work with domestic violence and sexual assault survivors, who note that this distortive nature of shame is what prevents many women from coming forward with a report.

Even in cases where shame seems to be an appropriate response, it often still causes damage. At the Festival of Dangerous Ideas session in 2022, World Without Rape, panellist and journalist Jess Hill described an advertisement she once saw:

“…a group of male friends call out their mate who was talking to his wife aggressively on the phone. The way in which they called him out came from a place of shame, and then the men went back to having their beers like nothing happened.” Hill encourages us to think: where will the man in the ad take his shame with him at the end of the night? It will likely go home with him, perpetuating a cycle of violence.

Likewise, co-panellist and historian Joanna Bourke noted something similar: “rapists have extremely high levels of abuse and drug addictions because they actually do feel shame”. Neither of these situations seem ‘normatively distorted’ in Nussbaum’s sense, and yet they still seem to go wrong. Bourke and other panellists suggested that what is happening here is not necessarily a failing of shame, but a failing of the social processes surrounding it.

Shame opens us to vulnerability, but to sit with vulnerability and reflect requires us to be open to very difficult conversations.

If the social framework for these conversations isn’t set up, we end up with unjust shame or just shame that, unsupported, still manifests itself ultimately in further destruction.

However, this nuance is far from intuitive. While people are saddened by the idea of victims feeling shame, they often feel righteous in their assertions that perpetrators of crimes or transgressors of socials norms should feel shame, and that their lack of shame is something that causes the shameful behaviour in the first place.

Shame certainly has potential to be a force for good if it reminds us of moral standards, or in trying to avoid it we are motivated to abide by moral standards, but it’s important to retain a level of awareness that shame alone is often not enough to define and maintain the ethical playing field.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Negativity bias

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

To Russia, without love: Are sanctions ethical?

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Power and the social network

Big thinker

Relationships, Society + Culture

9 LGBTQIA+ big thinkers you should know about

Ethics Explainer: Moral hazards

When individuals are able to avoid bearing the costs of their decisions, they can be inclined towards more risky and unethical behaviour.

Sailing across the open sea in a tall ship laden with trade goods is a risky business. All manner of misfortune can strike, from foul weather to uncharted shoals to piracy. Shipping businesses in the 19th century knew this only too well, so when the budding insurance industry started offering their services to underwrite the ships and cargo, and cover the costs should they experience misadventure, they jumped at the opportunity.

But the insurance companies started to notice something peculiar: insured ships were more likely to meet with misfortune than ships that were uninsured. And it didn’t seem to be mere coincidence. Instead, it turned out that shipping companies covered by insurance tended to invest less in safety and were more inclined to make risky decisions, such as sailing into more dangerous waters to save time. After all, they had the safety net of insurance to bail them out should anything go awry.

Naturally, the insurance companies were not impressed, and they soon coined a term for this phenomenon: “moral hazard”.

Risky business

Moral hazard is usually defined as the propensity for the insured to take greater risks than they might otherwise take. So the owners of a building insured against fire damage might be less inclined to spend money on smoke alarms and extinguishers. Or an individual who insures their car against theft might be less inclined to invest in a more reliable car alarm.

But it’s a concept that has applications beyond just insurance.

Consider the banks that were bailed out following the 2008 collapse of the subprime mortgage market in the United States. Many were considered “too big to fail”, and it seems they knew it. Their belief that the government would bail them out rather than let them collapse gave the banks’ executives a greater incentive to take riskier bets. And when those bets didn’t pay off, it was the public that had to foot much of the bill for their reckless behaviour.

There is also evidence that the existence of government emergency disaster relief, which helps cover the costs of things like floods or bushfires, might encourage people to build their homes in more risky locations, such as in overgrown bushland or coastal areas prone to cyclone or flood.

What makes moral hazards “moral” is that they allow people to avoid taking responsibility for their actions. If they had to bear the full cost of their actions, then they would be more likely to act with greater caution. Things like insurance, disaster relief and bank bailouts all serve to shift the costs of a risky decision from the shoulders of the decision-maker onto others – sometimes placing the burden of that individual’s decision on the wider public.

Perverse incentives

While the term “moral hazard” is typically restricted examples involving insurance, there is a general principle that applies across many domains of life. If we put people into a situation where they are able to offload the costs of their decisions onto others, then they are more inclined to entertain risks that they would otherwise avoid or engage in unethical behaviour.

Like the salesperson working for a business they know will be closing in the near future might be more inclined to sell an inferior or faulty product to a customer, knowing that they won’t have to worry about dealing with warranty claims.

This means there’s a double edge to moral hazards. One is born by the individual who has to resist the opportunity to shirk their personal responsibility. The other is born by those who create the circumstances that create the moral hazard in the first place.

Consider a business that has a policy saying the last security guard to check whether the back door is locked is held responsible if there is a theft. That might give security guards an incentive to not check the back door as often, thus decreasing the chance that they are the last one to check it, but increasing the chance of theft.

Insurance companies, governments and other decision-makers need to ensure that the policies and systems they put in place don’t create perverse incentives that steer people towards reckless or unethical behaviour. And if they are unable to eliminate moral hazards, they need to put in place other policies that provide oversight and accountability for decision making, and punish those who act unethically.

Few systems or processes will be perfect, and we always require individuals to exercise their ethical judgement when acting within them. But the more we can avoid creating the conditions for moral hazards, the less incentives we’ll create for people to act unethically.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

The anti-diversity brigade is ruled by fear

Reports

Business + Leadership

EVERYDAY ETHICS FOR FINANCIAL ADVISERS

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Measuring culture and radical transparency

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

The sponsorship dilemma: How to decide if the money is worth it

Ethics Explainer: Altruism

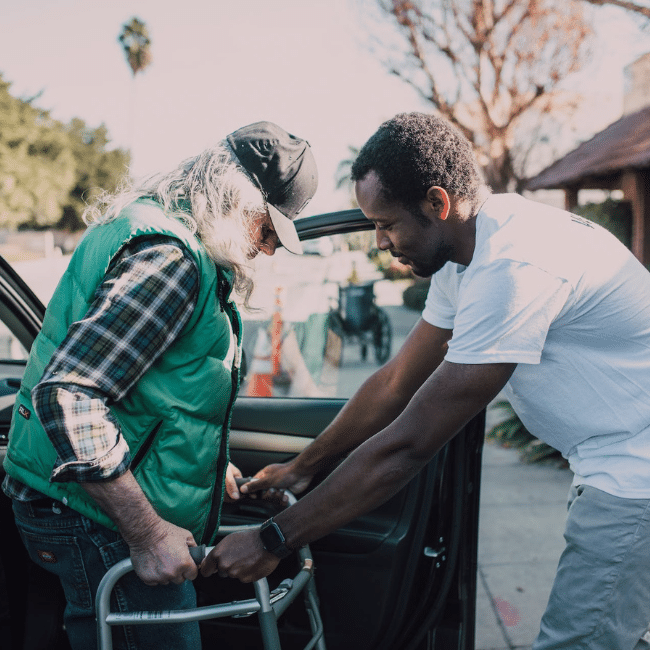

Amelia notices her elderly neighbour struggling with their shopping and lends them a hand. Mo decides to start volunteering for a local animal shelter after seeing a ‘help wanted’ ad. Alexis has been donating blood twice a year since they heard it was in such short supply.

These are all examples, of behaviours that put the well-being of others first – otherwise known as altruism.

Altruism is a principle and practice that concerns the motivation and desire to positively affect another being for their own sake. Amelia’s act is altruistic because she wishes to alleviate some suffering from her neighbour, Mo’s because he wishes to do the same for the animals and shelter workers, and Alexis’ because they wish to do the same to dozens of strangers.

Crucially, motivation is what is key in altruism.

If Alexis only donates blood because they really want the free food, then they’re not acting altruistically. Even though the blood is still being donated, even though lives are still being saved, even though the act itself is still good. If their motivation comes from self-interest alone, then the act lacks the other-directedness or selflessness of altruism. Likewise, if Mo’s motivation actually comes from wanting to look good to his partner, or if Amelia’s motivation comes from wanting to be put in her neighbour’s will, their actions are no longer altruistic.

This is because altruism is characterised as the opposite of selfishness. Rather than prioritising themself, the altruist will be concerned with the well-being of others. However, actions do remain altruistic even if there are mixed motives.

Consider Amelia again. She might truly care for her elderly neighbour. Maybe it’s even a relative or a good family friend. Nevertheless, part of her motivation for helping might also be the potential to gain an inheritance. While this self-interest seems at odds with altruism, so long as her altruistic motive (genuine care and compassion) also remains then the act can still be considered altruistic, though it is sometimes referred to as “weak” altruism.

Altruism can (and should) also be understood separately from self-sacrifice. Altruism needn’t be self-sacrificial, though it is often thought of in that way. Altruistic behaviours can often involve little or no effort and still benefit others, like someone giving away their concert ticket because they can no longer attend.

How much is enough?

There is a general idea that everyone should be altruistic in some ways at some times; though it’s unclear to what extent this is a moral responsibility.

Aristotle, in his discussions of eudaimonia, speaks of loving others for their own sake. So, it could be argued that in pursuit of eudaimonia, we have a responsibility to be altruistic at least to the extent that we embody the virtues of care and compassion.

Another more common idea is the Golden Rule: treat others as you would like to be treated. Although this maxim, or variations of it, is often related to Christianity, it actually dates at least as far back as Ancient Egypt and has arisen in countless different societies and cultures throughout history. While there is a hint of self-interest in the reciprocity, the Golden Rule ultimately encourages us to be altruistic by appealing to empathy.

We can find this kind of reasoning in other everyday examples as well. If someone gives up their seat for a pregnant person on a train, it’s likely that they’re being altruistic. Part of their reasoning might be similar to the Golden Rule: if they were pregnant, they’d want someone to give up a seat for them to rest.

Common altruistic acts often occur because, consciously or unconsciously, we empathise with the position of others.

Effective Altruism

So far, we have been describing altruism and some other concepts that steer us toward it. However, here is an ethical theory that has many strong things to say about our altruistic obligations and that is consequentialism (concern for the outcomes of our actions).

Given that, consequentialism can lead us to arguments that altruism is a moral obligation in many circumstances, especially when the actions are of no or little cost to us, since the outcomes are inherently positive.

For example, Australian philosopher Peter Singer has written extensively on our ethical obligations to donate to charity. He argues that most people should help others because most people are in a position where they can do a lot for significantly less fortunate people with relatively little effort. This might look different for different people – it could be donating clothes, giving to charity, volunteering, signing petitions. Whatever it is, the type of help isn’t necessarily demanding (donating clothes) and can be proportional (donating relative to your income).

One philosophical and social movement that heavily emphasises this consequentialist outlook is effective altruism, co-founded by Singer, and philosophers Toby Ord and Will MacAskill.

The effective altruist’s argument is that it’s not good enough just to be altruistic; we must also make efforts to ensure that our good deeds are as impactful as possible through evidence-based research and reasoning.

Stemming from the empirical foundation, this movement takes a seemingly radical stance on impartiality and the extent of our ethical obligations to help others. Much of this reasoning mirrors a principle outlined by Singer in his 1972 article, “Famine, Affluence and Morality”:

“If it is in our power to prevent something very bad from happening, without thereby sacrificing anything morally significant, we ought, morally, to do it.”

This seems like a reasonable statement to many people, but effective altruists argue that what follows from it is much more than our day-to-day incidental kindness. What is morally required of us is much stronger, given most people’s relative position to the world’s worst-off. For example, Toby Ord uses this kind of reasoning to encourage people to commit to donating at least 10% of their income to charity through his organisation “Giving What We Can”.

Effective altruists generally also encourage prioritising the interests of future generations and other sentient beings, like non-human animals, as well as emphasising the need to prioritise charity in efficient ways, which often means donating to causes that seem distant or removed from the individual’s own life.

While reasons for and extent of altruistic behaviour can vary, ethics tells us that it’s something we should be concerned with. Whether you’re a Platonist who values kindness, or a consequentialist who cares about the greater good, ethics encourages us to think about the role of altruism in our lives and consider when and how we can help others.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

WATCH

Relationships

Deontology

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Your child might die: the right to defy doctors orders

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Three ways philosophy can help you decide what to do

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Ozi Batla: Fatherhood is the hardest work I’ve ever done

Ethics explainer: Cultural Pluralism

Imagine a large, cosmopolitan city, where people from uncountable backgrounds and with numerous beliefs all thrive together. People embrace different cultural traditions, speak varying languages, enjoy countless cuisines, and educate their children on diverse histories and practices.

This is the kind of pluralism that most people are familiar with, but a diverse and culturally integrated area like this is specifically an example of cultural pluralism.

Pluralism in a general sense says there can be multiple perspectives or truths that exist simultaneously, even if some of those perspectives are contradictory. It’s contrasted with monism, which says only one kind of thing exists; dualism, which says there are only two kinds of things (for example, mind and body); and nihilism, which says that no things exist.

So, while pluralism more broadly refers to a diversity of views, perspectives or truths, cultural pluralism refers specifically to a diversity of cultures that co-exist – ideally harmoniously and constructively – while maintaining their unique cultural identities.

Sometimes an entire country can be considered culturally pluralistic, and in other places there may be culturally pluralistic hubs (like states or suburbs where there is a thriving multicultural community within a larger more broadly homogenous area).

On the other end of the spectrum is cultural monism, the idea that a certain area or population should have only one culture. Culturally monistic places (for example, Japan or North Korea) rely on an implicit or explicit pressure for others to assimilate. Whereas assimilation involves the homogenisation of culture, pluralism encourages diversity, often embracing people of different ethnic groups, backgrounds, religions, practices and beliefs to come together and share in their differences.

A pluralistic society is more welcoming and supportive of minority cultures because people don’t feel pressured to hide or change their identities. Instead, diverse experiences are recognised as opportunities for learning and celebration. This invites travel and immigration, and translates into better mental health for migrants, the promotion of harmony and acceptance of others, and enhances creativity by exposing people to perspectives and experiences outside of their usual remit.

We also know what the alternative is in many cases. Australia has a dark history of assimilation practices, a symptom of racist, colonial perspectives that saw the decimation of First Nations people and their cultures. Cultural pluralism is one response to this sort of cultural domination that has been damaging throughout history and remains so in many places today.

However, there are plenty of ethical complications that arise in the pursuit of cultural plurality.

For example, sociologist Robert D. Putnam published research in 2007 that spoke about negative short-medium term effects of ethnically diverse neighbourhoods. He found that, on average, trust, altruism and community cooperation was lower in these neighbourhoods, even between those of the same or similar ethnicities.

While Putnam denied that his findings were anti-multicultural, and argues that there are several positive long-term effects of diverse societies, the research does indicate some of the risks associated with cultural pluralism. It can take a large amount of effort and social infrastructure to build and maintain diverse communities, and if this fails or is done poorly it can cause fragmentation of cultural communities.

This also accords with an argument made by journalist David Goodhart, that says people are generally divided into “Anywheres” (people with a mobile identity) and “Somewheres” (people, usually outside of urban areas, who have marginalised, long-term, location-based identities). This incongruity, he says, accounts for things like Brexit and the election of Donald Trump, because they speak to the Somewheres who are threatened by changes to their status quo. Pluralism, Goodhart notes, risks overlooking the discomfort these communities face if they are not properly supported and informed.

Other issues with pluralism include the prioritisation of competing cultural values and traditions. What if one person’s culture is fundamentally intolerant of another person’s culture? This is something we see especially with cultures organised around or heavily influenced by religion. For example, Christianity and Islam are often at odds with many different cultures around issues of sexual preference and gendered rights and responsibilities.

If we are to imagine a truly culturally pluralistic society, how do we ethically integrate people who are intolerant of others?

Pluralism as a cultural ideal also has direct implications for things like politics and law, raising the age-old question about the relationship between morality and the law. If we want a pluralistic society generally, how do the variations in beliefs, values and principles translate into law? Is it better to have a centralised legal system or do we want a legal plurality that reflects the diversity of the area?

This does already exist in some capacity – many countries have Islamic courts that enforce Sharia law for their communities in addition to the overarching governmental law. This parallel law-enforcement also exists in some colonised countries, where parts of Indigenous law have been recognised. For example, in Australia, with the Mabo decision.

Another feature of genuine cultural pluralism that has huge ethical implications and considerations is diversity of media. This is the idea that there should be (that is, a media system that is not monopolised) and diverse representation in media (that is, media that presents varying perspectives and analyses).

Firstly, this ensures that media, especially news media, stays accountable through comparison and competition, rather than a select powerful few being able to widely disseminate their opinions unchecked. Secondly, it fosters a greater sense of understanding and acceptance by exposing people to perspectives, experiences and opinions that they might otherwise be ignorant or reflexively wary of. Thirdly, as a result, it reduces the risk that media, as a powerful disseminator of culture, could end up creating or reinforcing a monoculture.

While cultural pluralism is often seen as an obviously good thing in western liberal societies, it isn’t without substantial challenges. In the pursuit of tolerance, acceptance and harmony, we must be wary of fragmenting cultures and ensure that diverse communities have adequate social supports to thrive.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Big thinker

Relationships

Big Thinker: Steven Pinker

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Trust

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Should parents tell kids the truth about Santa?

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships, Science + Technology