Accountability the missing piece in Business Roundtable statement

Accountability the missing piece in Business Roundtable statement

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + Leadership

BY Dennis Gentilin The Ethics Centre 3 OCT 2019

Over the past few weeks a lot has been written about the “Statement on the Purpose of a Corporation” issued by the Business Roundtable in the United States.

The Business Roundtable, an association of chief executive officers from America’s leading companies, has shifted its position on who a corporation principally serves.

The original statement, published in 1997, suggested that companies exist to serve its shareholders. The new statement, signed by 163 chief executive officers, states that “While each of our individual companies serves its own corporate purpose, we share a fundamental commitment to all of our stakeholders.”

This “stakeholder approach” to corporate responsibility is not in itself ground-breaking. Nor is it a recent invention. In Johnson and Johnson’s corporate credo developed in 1943, the company lists patients, doctors and nurses as its primary stakeholders, followed by employees, customers, communities and finally shareholders.

Indeed, the shift to a stakeholder approach may not be as profound in practice as some have suggested. Even the Business Roundtable have said that the previous statement “does not accurately describe the ways in which we and our fellow CEOs endeavour every day to create value for all our stakeholders, whose long-term interests are inseparable.”

Given this, it is possible that chief executive officers only support the stakeholder approach to the extent that it benefits both themselves and the shareholder. And we should not necessarily decry this. Adam Smith, sometimes referred to as the “father of economics”, argued that individual self-interest can produce optimal outcomes, the source of his so-called “invisible hand”.

Even Milton Friedman, the much-maligned University of Chicago economist who is often held out as being the most vocal advocate for shareholder primacy, was not ignorant to the possibility that looking after the needs of stakeholders is not necessarily at odds with generating superior returns for shareholders in the long run. Famously, Friedman wrote:

“It may well be in the long-run interest of a corporation that is a major employer in a small community to devote resources to providing amenities to that community or to improving its government. That may make it easier to attract desirable employees, it may reduce the wage bill or lessen losses from pilferage and sabotage or have other worthwhile effects.”

However, as committed as the Business Roundtable might be, circumstances will prevail that are not supportive of the stakeholder approach. Uncompetitive markets result in companies benefiting at the expense of consumers. Seemingly sensible incentive schemes can drive perverse outcomes. And a company’s products, despite being highly valued by its customers, can have broader, deleterious consequences (fossil fuel companies producing carbon dioxide, social media companies empowering covert actors, and technology companies producing “e-waste” are three examples of the latter).

The signatories to the revamped Statement on the Purpose of a Corporation would have you believe that they can be trusted to manage these types of scenarios. We should be cautious taking them at their word. History shows that even well-intentioned chief executives find it extraordinarily difficult to drive the required change in a system where the incentives endorse the status quo. And in some cases, regardless of how hard they might try, they do not have the ability to do so. The most lucid corporate purpose statement won’t save us here.

It is therefore noteworthy that the Business Roundtable has omitted the idea of accountability from its statement. If chief executive officers are serious about serving all stakeholders, how will they be held accountable?

Milton Friedman also had something to say about this. He believed that corporations should conform “to the basic rules of society, both those embodied in law and those embodied in ethical custom.” But more importantly, as laissez faire as he was, he acknowledged that there was a role for government to “enforce compliance” and hold those who don’t “play the game” accountable.

Arguably this is the most important piece of the puzzle. Strong public institutions that develop good policy and hold corporations accountable. It is also the piece that is currently missing.

The recent financial services Royal Commission was a demonstration of what can happen when boundaries are established but not enforced. In a recent speech delivered by Commissioner Kenneth Hayne, he asked us to “grapple closely” with what the seemingly endless calls for Royal Commissions in Australia “are telling us about the state of our democratic institutions.”

But more relevant to this essay, Commissioner Hayne also provided his view on purpose statements and industry codes in the Royal Commission’s final report. He labelled them as mere “public relations puffs”, proposing that the only way they can be effective is by making them enforceable:

“If industry codes are to be more than public relations puffs, the promises made must be made seriously. If they are made seriously (and those bound by the codes say that they are), the promises that are set out in the code … must be kept. This must entail that the promises can be enforced by those to whom the promises are made.”

To be sure, the stance taken by the Business Roundtable should be applauded. Their intentions are without question noble. But more powerful would be a description of how they are going to hold themselves accountable to the statement and create the conditions that deliver value for all their stakeholders over the long-term.

Of course, this exercise would reveal the costs (financial and otherwise) that are associated with being genuinely committed to positive outcomes for all stakeholders. For some chief executive officers, the price would be too high. And because, like all of us, chief executives have their limits, so too does self-regulation.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Tim Soutphommasane on free speech, nationalism and civil society

WATCH

Business + Leadership

The thorny ethics of corporate sponsorships

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Science + Technology

AI can slowly shift an organisation’s core principles. Here’s how to spot ‘value drift’ early

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Who are corporations willing to sacrifice in order to retain their reputation?

BY Dennis Gentilin

Dennis Gentilin is an Adjunct Fellow at Macquarie University and currently works in Deloitte’s Risk Advisory practice.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

The new rules of ethical design in tech

The new rules of ethical design in tech

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + LeadershipScience + Technology

BY Matthew Beard The Ethics Centre 26 SEP 2019

This article was written for, and first published by Atlassian.

Because tech design is a human activity, and there’s no such thing as human behaviour without ethics.

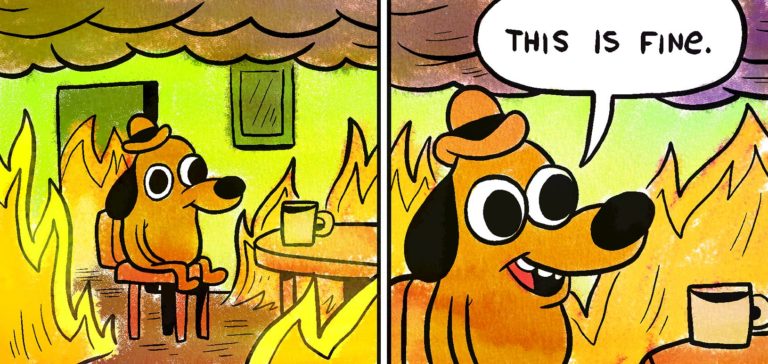

One of my favourite memes for the last few years is This is Fine. It’s a picture of a dog sitting in a burning building with a cup of coffee. “This is fine,” the dog announces. “I’m okay with what’s happening. It’ll all turn out okay.” Then the dog takes a sip of coffee and melts into the fire.

Working in ethics and technology, I hear a lot of “This is fine.” The tech sector has built (and is building) processes and systems that exclude vulnerable users by designing “nudges” that influence users, users who end up making privacy concessions they probably shouldn’t. Or, designing by hardwiring preconceived notions of right and wrong into technologies that will shape millions of people’s lives.

But many won’t acknowledge they could have ethics problems.

This is partly because, like the dog, they don’t concede that the fire might actually burn them in the end. Lots of people working in tech are willing to admit that someone else has a problem with ethics, but they’re less likely to believe is that they themselves have an issue with ethics.

And I get it. Many times, people are building products that seem innocuous, fun, or practical. There’s nothing in there that makes us do a moral double-take.

The problem is, of course, that just because you’re not able to identify a problem doesn’t mean you won’t melt to death in the sixth frame of the comic. And there are issues you need to address in what you’re building, because tech design is a human activity, and there’s no such thing as human behaviour without ethics.

Your product probably already has ethical issues

To put it bluntly: if you think you don’t need to consider ethics in your design process because your product doesn’t generate any ethical issues, you’ve missed something. Maybe your product is still fine, but you can’t be sure unless you’ve taken the time to consider your product and stakeholders through an ethical lens.

Look at it this way: If you haven’t made sure there are no bugs or biases in your design, you haven’t been the best designer you could be. Ethics is no different – making people (and their products) the best they can be.

Take Pokémon Go, for example. It’s an awesome little mobile game that gives users the chance to feel like Pokémon trainers in the real world. And it’s a business success story, recording a profit of $3 billion at the end of 2018. But it’s exactly the kind of innocuous-seeming app most would think doesn’t have any ethical issues.

But it does. It distracted drivers, brought users to dangerous locations in the hopes of catching Pokémon, disrupted public infrastructure, didn’t seek the consent of the sites it included in the game, unintentionally excluded rural neighbourhoods (many populated by racial minorities), and released Pokémon in offensive locations (for instance, a poison gas Pokémon in the Holocaust Museum in Washington DC).

Quite a list, actually.

This is a shame, because all of this meant that Pokemon Go was not the best game it could be. And as designers, that’s the goal – to make something great. But something can’t be great unless it’s good, and that’s why designers need to think about ethics.

Here are a few things you can embed within your design processes to make sure you’re not going to burn to death, ethically speaking, when you finally launch.

1. Start with ethical pre-mortems

When something goes wrong with a product, we know it’s important to do a postmortem to make sure we don’t repeat the same mistakes. Postmortems happen all the time in ethics. A product is launched, a scandal erupts, and ethicists wind up as talking heads on the news discussing what went wrong.

As useful as postmortems are, they can also be ways of washing over negligent practices. When something goes wrong and a spokesperson says, “We’re going to look closely at what happened to make sure it doesn’t happen again.” I want to say, “Why didn’t you do that before you launched?” That’s what an ethical premortem does.

Sit down with your team and talk about what would make this product an ethical failure. Then work backwards to the root causes of that possible failure. How could you mitigate that risk? Can you reduce the risk enough to justify going forward with the project? Are your systems, processes and teams set up in a way that enables ethical issues to be identified and addressed?

Tech ethicist Shannon Vallor provides a list of handy premortem questions:

- How Could This Project Fail for Ethical Reasons?

- What Would be the Most Likely Combined Causes of Our Ethical Failure/Disaster?

- What Blind Spots Would Lead Us Into It?

- Why Would We Fail to Act?

- Why/How Would We Choose the Wrong Action?

What Systems/Processes/Checks/Failsafes Can We Put in Place to Reduce Failure Risk?

2. Ask the Death Star question

The book Rogue One: Catalyst tells the story of how the galactic empire managed to build the Death Star. The strategy was simple: take many subject matter experts and get them working in silos on small projects. With no team aware of what other teams were doing, only a few managers could make sense of what was actually being built.

Small teams, working in a limited role on a much larger project, with limited connection to the needs, goals, objectives or activities of other teams. Sound familiar? Siloing is a major source of ethical negligence. Teams whose workloads, incentives, and interests are limited to their particular contribution seldom can identify the downstream effects of their contribution, or what might happen when it’s combined with other work.

While it’s unlikely you’re secretly working for a Sith Lord, it’s still worth asking:

- What’s the big picture here? What am I actually helping to build?

- What contribution is my work making and are there ethical risks I might need to know about?

- Are there dual-use risks in this product that I should be designing against?

- If there are risks, are they worth it, given the potential benefits?

3. Get red teaming

Anyone who has worked in security will know that one of the best ways to know if a product is secure is to ask someone else to try to break it. We can use a similar concept for ethics. Once we’ve built something we think is great, ask some people to try to prove that it isn’t.

Red teams should ask:

- What are the ethical pressure points here?

- Have you made trade-offs between competing values/ideals? If so, have you made them in the right way?

- What happens if we widen the circle of possible users to include some people you may not have considered?

- Was this project one we should have taken on at all? (If you knew you were building the Death Star, it’s unlikely you could ever make it an ethical product. It’s a WMD.)

- Is your solution the only one? Is it the best one?

4. Decide what your product’s saying

Ever seen a toddler discover a new toy? Their first instinct is to test the limits of what they can do. They’re not asking What was the intention of the designer, they’re testing how the item can satisfy their needs, whatever they may be. In this case they chew it, throw it, paint with it, push it down a slide… a toddler can’t access the designer’s intention. The only prompts they have are those built into the product itself.

It’s easy to think about our products as though they’ll only be used in the way we want them to be used. In reality, though, technology design and usage is more like a two-way conversation than a set of instructions. Given this, it’s worth asking: if the user had no instructions on how to use this product, what would they infer purely from the design?

For example, we might infer from the hidden-away nature of some privacy settings on social media platforms that we shouldn’t tweak our privacy settings. Social platforms might say otherwise, but their design tells a different story. Imagine what your product would be saying to a user if you let it speak for itself.

This is doubly important, because your design is saying something. All technology is full of affordances – subtle prompts that invite the user to engage with it in some ways rather than others. They’re there whether you intend them to be or not, but if you’re not aware of what your design affords, you can’t know what messages the user might be receiving.

Design teams should ask:

- What could a infer from the design about how a product can/should be used?

- How do you want people to use this?

- How don’t you want people to use this?

- Do your design choices and affordances reflect these expectations?

- Are you unnecessarily preventing other legitimate uses of the technology?

5. Don’t forget to show your work

One of the (few) things I remember from my high school math classes is this: you get one mark for getting the right answer, but three marks for showing the working that led you there.

It’s also important for learning: if you don’t get the right answer, being able to interrogate your process is crucial (that’s what a post-mortem is).

For ethical design, the process of showing your work is about being willing to publicly defend the ethical decisions you’ve made. It’s a practical version of The Sunlight Test – where you test your intentions by asking if you’d do what you were doing if the whole world was watching.

Ask yourself (and your team):

- Are there any limitations to this product?

- What trade-offs have you made (e.g. between privacy and user-customisation)?

- Why did you build this product (what problems are you solving?)

- Does this product risk being misused? If so, what have you done to mitigate those risks?

- Are there any users who will have trouble using this product (for instance, people with disabilities)? If so, why can’t you fix this and why is it worth releasing the product, given it’s not universally accessible?

- How probable is it that the good and bad effects are likely to happen?

Ethics is an investment

I’m constantly amazed at how much money, time and personnel organisations are willing to invest in culture initiatives, wellbeing days and the like, but who haven’t spent a penny on ethics. There’s a general sense that if you’re a good person, then you’ll build ethical stuff, but the evidence overwhelmingly proves that’s not the case. Ethics needs to be something you invest in learning about, building resources and systems around, recruiting for, and incentivising.

It’s also something that needs to be engaged in for the right reasons. You can’t go into this process because you think it’s going to make you money or recruit the best people, because you’ll abandon it the second you find a more effective way to achieve those goals. A lot of the talk around ethics in technology at the moment has a particular flavour: anti-regulation. There is a hope that if companies are ethical, they can self-regulate.

I don’t see that as the role of ethics at all. Ethics can guide us toward making the best judgements about what’s right and what’s wrong. It can give us precision in our decisions, a language to explain why something is a problem, and a way of determining when something is truly excellent. But people also need justice: something to rely on if they’re the least powerful person in the room. Ethics has something to say here, but so do law and regulation.

If your organisation says they’re taking ethics seriously, ask them how open they are to accepting restraint and accountability. How much are they willing to invest in getting the systems right? Are they willing to sack their best performer if that person isn’t conducting themselves the way they should?

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Ethical issues and human resource development: some thoughts

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Ethical redundancies continue to be missing from the Australian workforce

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

The value of principle over prescription

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

6 Myths about diversity for employers to watch

BY Matthew Beard

Matt is a moral philosopher with a background in applied and military ethics. In 2016, Matt won the Australasian Association of Philosophy prize for media engagement. Formerly a fellow at The Ethics Centre, Matt is currently host on ABC’s Short & Curly podcast and the Vincent Fairfax Fellowship Program Director.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Ethics Explainer: Agape

How many people do you think we can love? Can we love everyone? Can we love everyone equally? The answers to these questions obviously depend on what the nature of this kind of love is, and what it looks like or demands of us in practice.

“Love is all you need”

Agape is a form of love that is commonly referred to as ‘neighbourly love’, the love ethic, or sometimes ‘universal love’. It rests on the idea that all people are our ‘brothers and sisters’ who deserve our care and respect. Agape invites us to actively consider and act upon the interests of other people, in more-or-less the same proportion as you consider (and usually act upon) your own interests.

We can trace the concept back to Ancient Greece, a time in which they had more than one word to describe various kinds of love. Commonly, useful distinctions can be made between eros, philia, and agape.

Eros is the kind of love we most often associate with romantic partners, particularly in the early stages of a love affair. It’s the source of English words like ‘erotic’ and ‘erotica’.

Philia generally refers to the affection felt between friends or family members. It is non-sexual in nature and usually reciprocal. It is characterised by a mutual good will that manifests in friendship.

Although both eros and philia have others as their focus, they can both entail a kind of self-interest or self-gratification (after all, in an ideal world our friends and lovers both give us pleasure).

Agape is often contrasted to these kinds of love because it lacks self-interest, self-gratification or self-preservation. It is motivated by the interest and welfare of all others. It is global and compassionate, rather than focussed on a single individual or a few people.

Another significant difference between agape and other forms of love is that we choose and cultivate agape. It’s not something that ‘happens’ to us like becoming a friend or falling romantically in love, it’s something we work toward. It is often considered praiseworthy and holds the lover to a high moral standard.

Agape is a form of love that values each person regardless of their individual characteristics or behaviour. In this way it is usually contrasted to eros or philia, where we usually value and like a person because of their characteristics.

Agape in traditional texts

The concept of agape we now have has been strongly influenced by the Christian tradition. It symbolises the love God has for people, and the love we (should) have for God in return. By extension, if we love our ‘neighbours’ (others) as we do God, then we should also love everyone else in a universal and unconditional manner, simply because they are created in the likeness of God.

The Jesus narrative asks followers to act with love (agape) regardless of how they feel. This early Christian ethical tradition encourages us to “love thy neighbour as thyself”. In the Buddhist tradition K’ung Fu-tzu (Confucius) similarly says, “Work for the good of others as you would work for your own good.”

Another great exponent of this ethic of love is Mahatma Gandhi who lived, worked, and died to keep this transcendent idea of universal love alive. Gandhi was known for saying, “Hate the sin, love the sinner”.

Advocates for non-violent resistance and pacifism that include Gandhi, Martin Luther King, Jr., and John Lennon and Yoko Ono also refer to the power of love as a unifying force that can overcome hate and remind us of our common humanity, regardless of our individual differences.

Such ideology rests on principles that are resonant with agape, urging us to love all people and forgive them for whatever wrongs we believe they have committed. In this way, agape sets a very high moral standard for us to follow.

However, this idea of generalised, unconditional love leaves us with an important and challenging question: is it possible for human beings to achieve? And if so, how far may it extend? Can we really love the whole of humanity?

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

When identity is used as a weapon

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Ask me tell me: Why women think it’s ok to lie about contraception

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Negativity bias

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Whose home, and who’s home?

BY Dr Laura D’Olimpio

Dr Laura D’Olimpio is senior lecturer in philosophy of education at the University of Birmingham, UK, and co-edits the Journal of Philosophy in Schools.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

MIT Media Lab: look at the money and morality behind the machine

MIT Media Lab: look at the money and morality behind the machine

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + LeadershipScience + Technology

BY Matthew Beard 18 SEP 2019

When convicted sex offender, alleged sex trafficker and financier to the rich and famous Jeffrey Epstein was arrested and subsequently died in prison, there was a sense that some skeletons were about to come out of the closet.

However, few would have expected that the death of a well-connected, social high-flying predator would call into disrepute one of the world’s most reputable AI research labs. But this is 2019, so anything can happen. And happen it has.

Two weeks ago, New Yorker magazine’s Ronan Farrow reported that Joi Ito, the director of MIT’s prestigious Media Lab, which aims to “focus on the study, invention, and creative use of digital technologies to enhance the ways that people think, express, and communicate ideas, and explore new scientific frontiers,” had accepted $7.5 million in anonymous funding from Epstein, despite knowing MIT had him listed as a “disqualified donor” – presumably because of his previous convictions for sex offences.

Emails obtained by Farrow suggest Ito wrote to Epstein asking for funding to continue to pay staff salaries. Epstein allegedly procured donations from other philanthropists – including Bill Gates – for the Media Lab, but all record of Epstein’s involvement was scrubbed.

Since this has been made public, Ito – who lists one of his areas of expertise as “the ethics and governance of technology” – has resigned. The funding director who worked with Ito at MIT, Peter Cohen, now working at another university, has been placed on administrative leave. Staff at MIT Media Lab have resigned in protest and others are feeling deeply complicit, betrayed and disenchanted at what has transpired.

What happened at MIT’s Media Lab is an important case study in how the public conversation around the ethics of technology needs to expand to consider more than just the ethical character of systems themselves. We need to know who is building these systems, why they’re doing so and who is benefitting. In short, ethical considerations need to include a supply chain analysis of how the technology came to be created.

This is important is because technology ethics – especially AI ethics – is currently going through what political philosopher Annette Zimmerman calls a “gold rush”. A range of groups, including The Ethics Centre, are producing guides, white papers, codes, principles and frameworks to try to respond to the widespread need for rigorous, responsive AI ethics. Some of these parties genuinely want to solve the issues; others just want to be able to charge clients and have retail products ready to go. In either case, the underlying concern is that the kind of ethics that gets paid gets made.

For instance, funding is likely to dictate where the world’s best talent is recruited and what problems they’re asked to solve. Paying people to spend time thinking about these issues, providing the infrastructure for multidisciplinary (or in MIT Media Lab’s case, “anti disciplinary”) groups to collaborate is expensive. Those with money will have a much louder voice in public and social debates around AI ethics and have considerable power to shape the norms that will eventually shape the future.

This is not entirely new. Academic research – particularly in the sciences – has always been fraught. It often requires philanthropic support, and it’s easy to rationalise the choice to take this from morally questionable people and groups (and, indeed, the downright contemptible). Vox’s Kelsey Piper summarised the argument neatly: “Who would you rather have $5 million: Jeffrey Epstein, or a scientist who wants to use it for research? Presumably the scientist, right?”

What this argument misses, as Piper points out, is that when it comes to these kinds of donations, we want to know where they’re coming from. Just as we don’t want to consume coffee made by slave labour, we don’t want to chauffeured around by autonomous vehicles whose AI was paid for by money that helped boost the power and social standing of a predator.

More significantly, it matters that survivors of sexual violence – perhaps even Epstein’s own – might step into vehicles, knowingly or not, whose very existence stemmed from the crimes whose effects they now live with.

Paying attention to these concerns is simply about asking the same questions technology ethicists already ask in a different context. For instance, many already argue that the provenance of a tech product should be made transparent. In Ethical by Design: Principles for Good Technology, we argue that:

The complete history of artefacts and devices, including the identities of all those who have designed, manufactured, serviced and owned the item, should be freely available to any current owner, custodian or user of the device.

It’s a natural extension of this to apply the same requirements to the funding and ownership of tech products. We don’t just need to know who built them, perhaps we also need to know who paid for them to be built, and who is earning capital (financial or social) as a result.

AI and data ethics have recently focused on concerns around the unfair distribution of harms. It’s not enough, many argue, that an algorithm is beneficial 95% of the time, if the 5% who don’t benefit are all (for example) people with disabilities or from another disadvantaged, minority group. We can apply the same principle to the Epstein funding: if the moral costs of having AI funded by a repeated sex offender are borne by survivors of sexual violence, then this is an unacceptable distribution of risks.

MIT Media Lab, like other labs around the world, literally wants to design the future for all of us. It’s not unreasonable to demand that MIT Media Lab and other groups in the business of designing the future, design it on our terms – not those of a silent, anonymous philanthropist.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships

Treating citizens as customers is a recipe for distrust

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Banks now have an incentive to change

Big thinker

Society + Culture, Business + Leadership

Big Thinker: Ayn Rand

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

The Royal Commission has forced us to ask, what is business good for?

BY Matthew Beard

Matt is a moral philosopher with a background in applied and military ethics. In 2016, Matt won the Australasian Association of Philosophy prize for media engagement. Formerly a fellow at The Ethics Centre, Matt is currently host on ABC’s Short & Curly podcast and the Vincent Fairfax Fellowship Program Director.

Ageing well is the elephant in the room when it comes to aged care

Ageing well is the elephant in the room when it comes to aged care

Opinion + AnalysisHealth + WellbeingRelationships

BY Matthew Beard 18 SEP 2019

I recently came across a quote from philosopher Jean Jacques Rousseau, talking about what it means to live well:

“To live is not to breathe but to act. It is to make use of our organs, our senses, our faculties, of all the parts of ourselves which give us the sentiment of our existence. The man who has lived the most is not he who has counted the most years but he who has most felt life. Men have been buried at one hundred who have died at their birth.”

Perhaps unsurprisingly, I found myself nodding sagely along as I read. Because life isn’t something we have, it’s something we do. It is a set of activities that we can fuse with meaning. There doesn’t seem much value to living if all we do with it is exist. More is demanded of us.

Rousseau’s quote isn’t just sage; it’s inspiring. It makes us want to live better – more fully. It captures an idea that moral philosophers have been exploring for thousands of years: what it means to ‘live well’ – to have a life worth living.

Unfortunately, it also illustrates a bigger problem. Because in our current reality, not everyone is able to live the way Rousseau outlines as being the gold standard for Really Good LivingTM.

This is a reality that professionals working in the aged care sector should know all too well. They work directly with people who don’t have full use of their organs, their faculties or their senses. And yet when I presented Rousseau’s thought to a room full of aged care professionals recently, they felt the same inspiration and agreement that I’d felt.

That’s a problem.

If the good life looks like a robust, activity-filled life, what does that tell us about the possibility for the elderly to live well? And if we don’t believe that the elderly can live well, what does that mean for aged care?

If you have been following the testimony around the Aged Care Royal Commission, you’ll be aware of the galling evidence of misconduct, negligence and at times outright abuse. The most vulnerable members of our communities, and our families, have been subject to mistreatment due in part to a commercial drive to increase the profitability of aged care facilities at the expense of person-centred care .

Absent from the discussion thus far has been the question of ‘the good life’. That’s understandable given the range of much more immediate and serious concerns facing the aged care sector, but it is one that cannot be ignored.

In 2015, celebrity chef and aged care advocate Maggie Beer told The Ethics Centre that she wanted “to create a sense of outrage about [elderly people] who are merely existing”. Since then she has gone on to provide evidence to the Royal Commission, because she believes that food is about so much more than nutrition. It’s about memory, community, pleasure and taking care and pride in your work.

Consider the evidence given around food standards in aged care. There have been suggestions that uneaten food is being collected and reused in the kitchens for the next meal; that there is a “race to the bottom” to cut costs of meals at the expense of quality, and that the retailers selling to aged care facilities wildly inflate their prices. The result? Bad food for premium prices.

We should be disturbed by this. This food doesn’t even permit people to exist, let alone flourish. It leaves them wasting away, undernourished. It’s abhorrent. But what should be the appropriate standard for food within aged care? How should we determine what’s acceptable? Do we need food that is merely nutritious and of an acceptable standard, or does it need to do more than that?

Answering that question requires us to confront an underlying question:

Do we believe aged care is simply about providing people’s basic needs until they eventually die?

Or is it much more than that? Is it about ensuring that every remaining moment of life provides the “sentiment of existence” that Rousseau was concerned with?

When you look at the approximately 190,000 words of testimony that’s been given to the Royal Commission thus far, a clear answer begins to emerge. Alongside terms like ‘rights’, ‘harms’ and ‘fairness’ –which capture the bare minimum of ethical treatment for other people – appear words such as ‘empathy’, ‘love’ and ‘connection’. These words capture more than basic respect for persons, they capture a higher standard of how we should relate to other people. They’re compassionate words. People are expressing a demand not just for the elderly to be cared for, but to be cared about.

Counsel assisting the Royal Commission, Peter Gray QC, recently told the commission that “a philosophical shift is required, placing the people receiving care at the centre of quality and safety regulation. This means a new system, empowering them and respecting their rights.”

It’s clear that a philosophical shift is necessary. However, I would argue that what’s not clear is if ‘person-centred care’ is enough. Because unless we are able to confront the underlying social belief that at a certain age, all that remains for you in life is to die, we won’t be able to provide the kind of empowerment you felt reading Rousseau at the start of this article.

There is an ageist belief embedded within our society that all of the things that make life worth living are unavailable to the elderly. As long as we accept that to be true, we’ll be satisfied providing a level of care that simply avoids harm, rather than one that provides for a rich, meaningful and satisfying life.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

LGBT…Z? The limits of ‘inclusiveness’ in the alphabet rainbow

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Paralympian pay vs. Olympian pay

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

The truths COVID revealed about consumerism

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Big Thinker: Baruch Spinoza

BY Matthew Beard

Matt is a moral philosopher with a background in applied and military ethics. In 2016, Matt won the Australasian Association of Philosophy prize for media engagement. Formerly a fellow at The Ethics Centre, Matt is currently host on ABC’s Short & Curly podcast and the Vincent Fairfax Fellowship Program Director.

Big Thinker: Peter Singer

Peter Singer (1946—present), one of world’s most influential living philosophers, is best known for applying rigorous logic to a range of practical issues from animal rights, giving to charity to the ethics of abortion and infanticide.

Singer was born in Melbourne in 1946 to Austrian Jewish Holocaust survivors. As a teen he declared his atheism and refused to celebrate his Bar Mitzvah. After studying law, history and philosophy at Melbourne University, he won a scholarship to Oxford University, writing his thesis on civil disobedience. In 1996 he ran unsuccessfully for the Greens in the Victorian State Parliament, and he has held posts at Melbourne, Monash, New York, London and Princeton Universities. His impact on public debate and academic philosophy cannot be overstated.

A key aspect of Singer’s contributions is the idea of ‘equal consideration of interests’. This informs both his views towards animals and charity. It means that we should consider the interests of any sentient beings who have the capacity to suffer and feel pleasure and pain.

Singer is a consequentialist, which means he defines ethical actions as ones that maximise overall pleasure and reduce overall pain. Part of what makes him such a challenging and influential thinker is his application of utilitarianism to real-world problems to offer counter-intuitive yet compelling solutions.’

Are you speciesist?

While at Oxford, Singer recalls a conversation with a friend over lunch that was the “most formative experience of [his] life”. Singer had the meat spaghetti, whereas his friend opted for the salad. His friend was the “first ethical vegetarian” he’d met. Two weeks later, Singer became a vegetarian and several years later published his seminal work Animal Liberation (1975).

Singer’s argument for not eating meat is more-or-less the same as another utilitarian philosopher, Jeremy Bentham. Bentham wrote that “the question is not can they reason or can they talk, but can they suffer?” Similarly, Singer argues that animals have the capacity to suffer. Just as we rightly condemn torture, we should also condemn practices like factory farming that inflict unjustifiable pain on non-human animals. He coined the term ‘speciesism’ to describe the privileging of humans over other animals.

Giving to charity

In Singer’s essay “Famine, Affluence and Morality” (1972), he argues that people in rich countries have a moral obligation to give to charities that help people in poverty overseas. He uses an analogy of a drowning child: if we were walking past a shallow pond and saw a child drowning, we would wade in and save the child, even if this meant wrecking our favourite and most expensive pair of shoes. Likewise, because we know there are children dying overseas from preventable poverty-related diseases, we should be giving at least some of our income to charities that fight this.

Opponents to Singer argue that his view about giving to charity is psychologically untenable, and that there are differences between giving to charity and saving a drowning child. For example, the physical act of pulling a child out from water is more morally compelling than sending a cheque overseas. Other arguments include: we don’t know the child will definitely be saved when we send the cheque, fighting poverty requires a collective global effort not just an individual donation, and charities are ineffective and have high overhead costs.

Singer concedes that there may be psychological reasons why people would save the drowning child yet don’t give much to charity, but he says even if it seems strange, rationally there are no relevant moral differences between the cases.

Responding to the criticism that charities may not be effective has led Singer to be a proponent of ‘effective altruism’. In his book The Most Good You Can Do (2015) he describes how a number of charity evaluators can recommend the most cost-effective way to do good. Singer recommends giving on a progressive scale, depending on one’s income.

Instead of pursuing careers in academia, some of Singer’s brightest past students have decided to work for Wall Street to make as much money as possible to then give this away to effective charities.

Controversy around infanticide

Singer has faced sustained criticism and protest throughout his career for his views on the sanctity of life and disability – especially in Germany, where in the 90’s, his views were compared to Nazism and university courses that set his books were boycotted. While he has always been a staunch supporter of abortion on the grounds that a foetus lacks self-consciousness and the criteria of personhood, he argues there is no moral difference between abortion in the womb and killing a newborn. Furthermore, because a newborn cannot yet be classified as a person, if its parents do not want it to survive, or if it has an extreme disability meaning that keeping it alive would be very costly, there is potential justification in killing it.

Religious sanctity-of-life critics argue that Singer’s ethics ignore the fundamental sanctity of human life. Disability rights advocates argue that Singer’s views are ableist, explaining that the quality of life of a disabled person is less than that of a non-disabled person ignores the socially-constructed nature of disability – its harms and inconveniences are largely because the built environment is made for able-bodied people.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Is it wrong to care about Ukraine more than other wars?

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights, Society + Culture

Corruption, decency and probity advice

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships, Society + Culture

You won’t be able to tell whether Depp or Heard are lying by watching their faces

Opinion + Analysis

Climate + Environment, Politics + Human Rights

Australia, it’s time to curb immigration

Join our newsletter

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

The invisible middle: why middle managers aren't represented

The invisible middle: why middle managers aren’t represented

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + Leadership

BY Cris Parker Cris 29 AUG 2019

The empty chair on stage was more than symbolic when The Banking and Finance Oath (BFO) was hosting a panel discussion on who holds the responsibility of culture within an organisation. In months of preparation, I had not found one middle manager who was willing or able to contribute to the discussion.

A chairman, director, CEO, HR specialist and a professor settled into their places, ready to give their opinions on the role they played in developing culture. The empty space at this event, three years ago, spoke volumes about the invisibility and voicelessness of those who have been promoted to manage others, but have little actual decision-making power.

Middle managers are often in the crossfire when it comes to apportioning blame for the failure to transform an organisation’s culture or to enact strategy. I have heard them derisively called “permafrost”, as if they are frozen into position and will only move with the application of a blowtorch.

“Culture Blockers” is another well-used epithet.

Middle managers are typically those people who head departments, business units, or who are project managers. It is their responsibility to implement the strategy that is imposed from above them and may have two management levels below them.

Over the past 20 years, the ranks of the middle managers have been slashed as organisations cut out unnecessary costs and aim towards flatter hierarchies. Those occupying the surviving positions may be characterised like this:

- They are often managing people for the first time and offered little training to deal with professional development, project management, time management and conflict resolution

- They may have been promoted because of their technical competence, rather than management ability

- Their management responsibilities may be added on top of what they were already doing before being promoted

- They have responsibility, but little formal authority

- They may have limited budget

- They are charged with enacting policy and embedding values, but may not be given the context or the “why”

- They have little autonomy or flexibility and may lack a sense of purpose.

All these characteristics make middle management a highly stressful position. Two large US studies found that people who work at this level are more likely to suffer depression (18 per cent of supervisors and managers) and had the lowest levels of job satisfaction.

“I don’t know any middle manager that feels like they’re doing a good job”, a middle manager recently told me.

However, the reason we need to pay attention to our middle managers is more than just concern for their welfare. Strategies and cultural change will fail if they are not supported and motivated. They are the custodians of culture and some would argue the creators, as people observe their behaviour as guidance for their own.

“We know what good looks like, but we’re not set up for success”, confided another middle manager.

Stanford University professor, Behnam Tabrizi, studied large-scale change and innovation efforts in 56 randomly selected companies and found that the 32 per cent that succeeded in their efforts could thank the involvement of their middle managers.

“In those cases, mid-level managers weren’t merely managing incremental change; they were leading it by working levers of power up, across and down in their organisations,” he wrote in the Harvard Business Review in 2016.

As more evidence that middle managers are intrinsic to a business’ success, Google founders Larry Page and Sergey Brin decided they could do without managers in the early days of the company in 2002. However, their experiment with a manager-less organisation only lasted a few months.

“They relented when too many people went directly to Page with questions about expense reports, interpersonal conflicts, and other nitty-gritty issues. And as the company grew, the founders soon realized that managers contributed in many other, important ways—for instance, by communicating strategy, helping employees prioritise projects, facilitating collaboration, supporting career development, and ensuring that processes and systems aligned with company goals,” wrote David Garvin, the C. Roland Christensen Professor at Harvard Business School.

With all of this in mind, you may think business leaders would now be seeking the views of their middle managers, to engage them in the cultural change required to regain public trust after the Royal Commission into Misconduct in the Banking, Superannuation and Financial Services Industry and other recent scandals. But sadly, no.

Just this month at The BFO conference, I was again presenting a panel discussion on the plight of middle managers. Prior to the day, two of the middle management participants – despite one being nominated by a senior leader – were pulled and additionally, the discussion was ruled Chatham House with journalists being asked to leave the room. Although I saw a glimpse of positivity, my research leading up to the discussion would suggest very little has changed and this issue is not limited to financial services.

While senior leaders are working tirelessly to overcome challenges in this transitional time, part of the answer is right in front of them (well, below them) – their hard-working middle managers. But first, they have to make the effort to engage them with appreciation, seek their views with empathy, and involve them in the formulation of strategy.

This article was originally written for The Ethics Alliance. Find out more about this corporate membership program. Already a member? Log in to the membership portal for more content and tools here.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships

The future does not just happen. It is made. And we are its authors.

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

The great resignation: Why quitting isn’t a dirty word

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Getting the job done is not nearly enough

LISTEN

Health + Wellbeing, Business + Leadership, Society + Culture

Life and Shares

Join our newsletter

BY Cris Parker

Cris Parker is the former Head of The Ethics Alliance and a Director of the Banking and Finance Oath at The Ethics Centre.

BY Cris

What are millennials looking for at work?

What are millennials looking for at work?

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + Leadership

BY The Ethics Alliance Cris 29 AUG 2019

Kat Dunn had a big life, but it wasn’t fulfilling. She was the youngest executive to serve on the senior leadership team of fund manager Perpetual Limited, but she went home each night feeling empty.

The former mergers and acquisitions lawyer tossed in the job two years ago and found her way into the non-profit sector, as CEO of the charity and social business promoter Grameen Australia.

Grameen Australia aims to take Social Business mainstream in Australia by scaling and starting up social businesses and advising socially-minded institutions on how to do the same.

Dunn says Millennials are more interested in “purpose” than money and security. She was speaking at the Crossroads: The 2019 Banking and Finance Oath Conference in Sydney in August.

Dunn said Perpetual tried to talk her out of leaving the fund manager. “I think they thought that I was going through some sort of early-onset midlife crisis.

“Because, after all, what sane person would give up a prestigious job, good money at the age of 33 when my priority should have been financial security, even more status, and chasing those last two rungs to get to be CEO of a listed company?”

‘I was living the dream’

Dunn said she was conditioned to believe she should want to climb the corporate ladder and make a lot of money.

“At 32 years old, I was appointed to be the youngest senior executive on the senior leadership team. The year before, I had just done $3 billion worth of deals in 18 months. I was, as some would say, living the dream,” said Dunn.

“So, you can imagine how disillusioned I felt when I went home every night feeling like I was a fraud. I was wondering how I could possibly reconcile my career with my identity of myself as an ethical person”.

Dunn had been put in charge of building the company’s continuous improvement program, but the move proved a disappointment. “I was so green because I thought [the role] meant I had the privilege of actually making things better for my colleagues.

“Later, I realised that it was just code for riskless cost-cutting … and impossible-to-achieve growth targets.”

Dunn said she had childhood aspirations to help create a sustainable future. “But, instead, I found myself perpetuating the very system of greed that I had vowed to change.”

“My whole career, I was told I had to make a choice between making a living or making a difference. I couldn’t do both and I found that deeply unsettling. I had cognitive dissonance.”

A desire to do work that matters

Dunn made the point that her motivations are shared by many – and not just be Millennials (she just scrapes over the line into Generation X).

By 2025, 75 per cent of the workforce will be Millennials (born between 1980 and 2000) and only 13 per cent of millennials say that their career goal involves climbing the corporate ladder, 60 per cent have aspirations to leave their companies in the next three years.

Moreover, 66 per cent of Millennials say their career goals involve starting their own business, according to a study by Bentley University.

“A steady paycheque and self-interest are not the primary drivers for many Millennials any more. The desire to do work that matters is,” said Dunn.

“Growing up poor, I thought that money would make me happy. I thought it would give me

security and social standing. I thought that if I ticked all of the boxes, that I would be free.

“At the height of my corporate career, though, I was anything but. I felt that making profits for profit’s sake was just deeply unfulfilling. For me, it was just the opposite of fulfilling – it caused me fear, distress and this stinging sense of isolation.

“What was strange is that no one else seemed to be outwardly admitting to feeling the same.”

The vision was impaired

Dunn recalled talking to a peer about strategy at the time and saying to him ‘I think our vision is wrong’.

She told him: “Our vision is to be Australia’s largest and most trusted independent wealth manager. I think it’s wrong. It’s not actually a vision. It’s a metric on some imaginary league table and it’s all about us.

“It doesn’t say anything about creating anything of value for anyone else.”

Her colleague retorted: “Kat, we have bigger fish to fry than our vision”.

She knew, at that point, she would not realise her potential in that environment.

Aaron Hurst, the author of the book, The Purpose Economy, predicts that purpose is going to be the primary organising principle for the fourth [entrepreneurial] economy.

He defines “purpose” as the experience of three things: personal growth, connection and impact.

“When he wrote the book, five years ago, Hurst said that by 2020, CEOs expected

demands for purpose in the consumer marketplace would increase by 300 per cent,” said Dunn.

“Now, what that means is that consumers deprioritise cost, convenience and function and make decisions based on their need to increase meaning in their lives.”

Dunn says that, as Millennials take on more leadership roles, this trend will become more evident in the job market.

“When you talk about how hard it is to find top talent to work in the industry, it is worthwhile knowing that for the top talent – the future leaders of the industry, of our country, our planet – work isn’t just about money.

“It is a vehicle to self-actualisation. They don’t just want to work nine-to-five for a secure income, they actually want to run through brick walls if it means they get to do work that they believe in, within a culture of integrity, for a purpose that leaves the world in a better place than they found it,

And they want to work in a place that develops not only their skills, but sharpens their character.”

Dunn said that when she left her corporate job, she would not have believed that the financial services industry could build a better society and a sustainable future.

However, she changed her mind when she learned about Grameen Bank, microfinance and social business.

This article was originally written for The Ethics Alliance. Find out more about this corporate membership program. Already a member? Log in to the membership portal for more content and tools here.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships

Unconscious bias: we’re blind to our own prejudice

Opinion + Analysis

Science + Technology, Business + Leadership

Should your AI notetaker be in the room?

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights, Science + Technology

Not too late: regaining control of your data

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

The near and far enemies of organisational culture

Join our newsletter

BY The Ethics Alliance

The Ethics Alliance is a community of organisations sharing insights and learning together, to find a better way of doing business. The Alliance is an initiative of The Ethics Centre.

BY Cris

Following a year of scandals, what's the future for boards?

Following a year of scandals, what’s the future for boards?

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + Leadership

BY Fiona Smith Cris 28 AUG 2019

As guardians of moral behaviour, company boards continue to be challenged. After a year of wall-to-wall scandals, especially within the Banking and Finance sector, many are asking whether there are better ways to oversee what is going on in a business.

A series of damning inquiries, including the recent Royal Commission into Financial Services, has spurred much discussion about holding boards to account – but far less about the structure of boards and whose interests they serve.

Ethicist Lesley Cannold expressed her frustration at this state of affairs in a speech to the finance industry, saying the Royal Commission was a lost opportunity to look at “root and branch” reform.

“We need to think of changes that will propel different kinds of leaders into place and rate their performance according to different criteria – criteria that relate to the wellbeing of a range of stakeholders, not just shareholders,” she said at the Crossroads: The 2019 Banking and Finance Oath Conference in Sydney in August.

This issue is close to the heart of Andrew Linden, PhD researcher on German corporate governance and a sessional Lecturer in RMIT’s School of Management. Linden favours the German system of having an upper supervisory board, with 50 per cent of directors elected by employees, and a lower management board to handle the day-to-day operations.

This system was imposed on the Germans after World War II to ensure companies were more socially responsible but, despite its advantages, has not spread to the English-speaking world, says Linden.

“For 40 years, corporate Australia has been allowed to get away with the idea that all they had to do was to serve shareholders and to maximise the value returned to shareholders.

“Now, that’s never been a feature of the Corporate Law. And directors have had very specific duties, publicly imposed duties, that they ought to have been fulfilling – but they haven’t.”

It is the responsibility of directors of public companies to govern in the corporation’s best interests and also ensure that corporations do not impose costs on the wider community, he says.

“All these piecemeal responses to the Banking Royal Commission are just Band-Aids on bullet wounds. They are not actually going to fix the problem. All through these corporate governance debates, there has not been too much of a focus on board design.”

The German solution – a two-tier model

This board structure, proposed by Linden, would have non-executive directors on an upper (supervisory) board, which would be legally tasked with monitoring and control, approving strategy and appointing auditors.

A lower management board would have executive directors responsible for implementing the approved strategy and day-to-day management.

This structure would separate non-executive from executive directors and create clear, legally separate roles for both groups, he says.

“Research into European banks suggests having employee and union representation on supervisory boards, combined with introduction of employee elected works councils to deal with management over day-to-day issues, reduces systemic risk and holds executives accountable,” according to Linden, who wrote about the subject with Warren Staples (senior lecturer in Management, RMIT University) in The Conversation last year.

Denmark, Norway and Sweden also have employee directors on corporate boards and the model is being proposed in the US by Democratic presidential hopefuls, including Senators Elizabeth Warren and Bernie Sanders.

As Linden said, “All the solutions that people in the English-speaking world typically think about are ownership-based solutions. So, you either go for co-operative ownership as an alternative to shareholder ownership, or, alternatively, it’s public ownership. All of these debates over decades have been about ‘who are the best owners’, not necessarily about the design of their governing bodies.”

Linden says research shows the riskiest banks are those that are English-speaking, for-profit, shareholder-dominated, overseen by an independent-director-dominated board.

“And they have been the ones that have imposed the most cost on communities,” he says.

Outsourcing the board

Allowing consultant-like companies to oversee governance is a solution proposed by two law academics in the US, who say they are “trying to encourage people to innovate in governance in ways that are fundamentally different than just little tweaks at the edges”.

Law professors Stephen Bainbridge (UCLA) and Todd Henderson (University of Chicago) say organisations are familiar with the idea of outsourcing responsibilities to lawyers, accountants, financial service providers.

“We envision a corporation, say Microsoft or ExxonMobil, hiring another company, say Boards-R-Us, to provide it with director services, instead of hiring 10 or so separate ‘companies’ to do so,” Henderson explained in an article.

“Just as other service firms, like Kirkland and Ellis, McKinsey and Company, or KPMG, are staffed by professionals with large support networks, so too would BSPs [board service providers] bring the various aspects of director services under a single roof. We expect the gains to efficiency from such a move to be quite large.

“We argue that hiring a BSP to provide board services instead of a loose group of sole proprietorships [non-executive directors] will increase board accountability, both from markets and judicial supervision.”

Outsourcing to specialists is a familiar concept, said Bainbridge in a video interview with The Conference Board.

“Would you rather deal with you know twelve part-timers who get hired in off the street, or would you rather deal with a professional with a team of professionals?”

Your director is a robot

A Hong Kong venture capital firm, Deep Knowledge Ventures, appointed the first-ever robot director to its board in 2014, giving it the power to veto investment decisions deemed as too risky by its artificial intelligence.

Australia’s Chief Scientist, Dr Alan Finkel, told company directors that he had initially thought the robo-director, named Vital, was a mere publicity stunt.

However, five years on “… the company is still in business. Vital is still on the Board. And waiting in the wings is her successor: Vital 2.0,” Finkel said at a governance summit held by the Australian Institute of Company Directors in March.

“The experiment was so successful that the CEO predicts we’ll see fully autonomous companies – able to operate without any human involvement – in the coming decade.

Stop and think about it: fully autonomous companies able to operate without any human involvement. There’d be no-one to come along to AICD summits!”

Dr Finkel reassured his audience that their jobs were safe … for now.

“… those director-bots would still lack something vital – something truly vital – and that’s what we call artificial general intelligence: the digital equivalent of the package deal of human abilities, human insights and human experiences,” he said.

“The experts tell us that the world of artificial general intelligence is unlikely to be with us until 2050, perhaps longer. Thus, shareholders, customers and governments who want that package deal will have to look to you for quite some time,” he told the audience.

“They will rely on the value that you, and only you, can bring, as a highly capable human being, to your role.”

Linden agrees that robo-directors have limitations and that, before people get too excited about the prospect of technology providing the solution to governance, they need to get back to basics.

“All these issues to do with governance failures get down to questions of ethics and morality and lawfulness – on making judgments about what is appropriate conduct,” he says, adding that it was “hopelessly naïve” to expect machines to be able to make moral judgements.

“These systems depend on who designs them, what kind of data goes into them. That old analogy ‘garbage in, garbage out’ is just as applicable to artificial intelligence as it is to human systems.”

This article was originally written for The Ethics Alliance. Find out more about this corporate membership program. Already a member? Log in to the membership portal for more content and tools here.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Health + Wellbeing

Navigating a workforce through stressful times

Reports

Business + Leadership

Thought Leadership: Ethics at Work, a 2018 Survey of Employees

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

The pivot: ‘I think I’ve been offered a bribe’

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights

Could a virus cure our politics?

Join our newsletter

BY Fiona Smith

Fiona Smith is a freelance journalist who writes about people, workplaces and social equity. Follow her on Twitter @fionaatwork

BY Cris

How BlueRock uses culture to attract top talent

How BlueRock uses culture to attract top talent

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + Leadership

BY The Ethics Alliance Cris 28 AUG 2019

Glossy highrises form a wall of corporate Australia along the Yarra River. The size of those companies and the magnetism of their brand names easily attract talented people and the attractions of big businesses are obvious.

These giants offer world-leading working conditions and benefits, career advancement, important work for powerful clients and the chance to work overseas.

Even still, people leave these big businesses for smaller ones all the time. And the reasons they quit can provide useful ammunition for those pointy-elbowed entrepreneurs who would love to get them on board.

A few blocks back from the river in Melbourne is the office of professional services firm, BlueRock, which started as an accounting business 11 years ago by five “escapees” from corporate Australia.

Today, the firm has around 170 employees and has diversified into areas such as law, private wealth, finance and insurance. Last year, they made it to fourth place on the Great Place To Work list for companies with between 100 and 999 employees.

It was also a finalist in the employer of choice category of the Lawyers Weekly 2019 Law Awards.

COO of the BlueRock, Dean Godfrey, says the biggest challenge in competing with the big firms is to attract graduates or to recruit people who are in the first half of their careers.

“There is still some prestige in going to some of the other more structured, high profile organisations,” he says. “When people are starting out, they don’t always know what they want.”

However, he says people who have had experience working for the big firms find they enjoy life more at BlueRock. “It is about having fun while you do it, working with like-minded people and understanding that the grass isn’t greener on the other side.”

Reasonable hours

Godfrey says people who make the move to BlueRock from big “churn-and-burn” firms often talk about wanting more purpose in their lives and getting away from the long hours culture.

“It is more about getting the job done than having prescriptive rules around having to be there,” he says.

Godfrey says BlueRock tries to ensure its clients – who are mostly business owners – share its vision for a healthy workplace.

The legal division distinguished itself by having less reliance on hourly-billing, which is the traditional way that lawyers’ time is charged out, but also a contributor to high stress levels in the practice of law.

Variety

One of the benefits of being in a smaller company is that employees are often given a broader range of experiences. “People in those larger firms almost cut their teeth on monotony, doing something really, really, really well,” says Godfrey.

Social purpose

BlueRock aspires to become a social enterprise and achieved B-Corp certification in 2017. This means it is legally required to consider the impact of their decisions on their workers, customers, suppliers, community, and the environment.

The challenge of B-Corp is that companies have to continue to improve to maintain their accreditation.

Godfrey says people who want to leave large firms often say they want to find more meaning in their work.

“You see people who have been in those businesses looking for something different. They may like the accounting stream or law stream or finance stream, but they want to be part of something that looks after its community,” he says.

BlueRock is working on becoming carbon-neutral and is phasing out its printers, is composting waste and considering more environmental lighting solutions. The firm is also reassessing its supply chain and the B-Corp status of its suppliers.

“We want to make sure they are putting their money where their mouth is,” he says.

BlueRock has partnered with B1G1 (Business For Good), a global giving initiative whereby every transaction made in a business “earns” a donation.

Employee ownership

Any employee of BlueRock is eligible to invest in the company and about one-third of staff have participated.

Unlike larger firms, where is it only the partners or those at senior levels who can become owners, the BlueRock founders determined that the people who work in the business should also be able to have a stake in the wealth and direction of the firm.

“It really does give you a feeling like you are a part of what we’re building,” says Godfrey.

As a firm that is focused on its entrepreneur clients, employees at BlueRock are also encouraged to have their own businesses.

Fun

The funky office space, which includes a giant chessboard and a unicorn sculpture, signals the company does not want to be seen as your usual professional services firm. The website promises fun activities and healthy food options and a range of flexible work options.

Managing director of BlueRock, Peter Lalor, has said people are left to decide how they do their work:

“Our philosophy is quite different: if we just let people get on with the job of working stuff out in a really smart, efficient way, they’ll get the right answer,” he said in a podcast.

“And I think that there’s a little bit of combativeness in people when they’re told they have to do something … They rebel against it. So, by having little to no structure in terms of how we do what we do, and no rules per se, people feel very empowered to get on with the job.”

This article was originally written for The Ethics Alliance. Find out more about this corporate membership program. Already a member? Log in to the membership portal for more content and tools here.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

WATCH

Business + Leadership, Climate + Environment, Science + Technology

How to build good technology

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Making the tough calls: Decisions in the boardroom

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Health + Wellbeing

The super loophole being exploited by the gig economy

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership