Leading ethically in a crisis

Leading ethically in a crisis

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + Leadership

BY Simon Longstaff The Ethics Centre 4 MAY 2020

It is difficult to excel in the art of leadership at any time – let alone in the midst of a crisis. Yet, this is precisely when good leadership is at a premium.

Right now, we must ask: what is ‘good’ leadership and how should leaders respond to the demands placed upon them during periods of extraordinary ethical complexity?

In attempting to answer these questions, I am thrown back on my own experience of leadership – including at present. In that sense, this not a detached, objective account. Rather, it is a reflection on (and of) lived experience.

The first obligation of a leader is to see, and sense, the whole picture. This means being alive to the undercurrents of feeling and emotion flowing through the organisation, while simultaneously keeping a clear view of the evolving strategic landscape and being ‘present’ in the moment.

The good leader needs to ensure that no one affected by the crisis is either overlooked or marginalised. This is harder than it seems. When driven by the ‘lash of necessity’, it’s all too easy to favour some people because of their utility, while dismissing others as ‘dead weight’.

I have been struck by the number of times that people have said the current emergency requires them, albeit reluctantly, to be cold-hearted, brutal or even cruel. I realise that such comments do not reflect their personal inclination – but instead reflect their response to evident necessity. However, I think that ethical leaders have an obligation to challenge that tendency – not least by naming it for what it is.

This is not to say that issues of relative utility are unimportant. Nor is it the case that one should avoid difficult decisions – such as those that might lead to job losses. Rather, the leader’s job is to ensure that such decisions are not made on the basis of cold, dispassionate calculation. Instead, the leader has an obligation to ensure that the ethical weight of each decision is felt and the heft of the burden that falls from each decision is known.

The second requirement of ethical leaders is that they resist demands for a certainty they cannot or should not provide. This is easier said than done. There are some contexts in which the suspense of ‘not knowing’ can be thrilling; however, for most people operating under stress, confronting ‘the unknown’ reinforces a sense of powerlessness and is deeply unsettling.

Even so, ethical leaders should resist the temptation to offer people false certainty, no matter how much that might be desired. Instead, a good leader should be resolutely trustworthy by only claiming as ‘certain knowledge’ what is genuinely known. Otherwise, a leader’s integrity can be undermined by something as simple as a gap between what was asserted as fact and what is subsequently revealed to be true.

None of this is to suggest that people be denied glimmers of hope based on one’s best estimate. It is merely to counsel caution – especially when a delay can open up new possibilities. The recent and unexpected emergence of the Federal Government’s JobKeeper scheme is a good example.

Leading during a crisis requires an ability to foresee a future, preferred state and then ‘backcast’ to the present when making decisions. As noted above, in the course of a crisis, many decisions will be made under the ‘lash of necessity’.

In these circumstances, people will be driven to accept the harshest treatment as a ‘necessary evil’. However, a time will come when the crisis is relegated to the past and those who remain in an organisation will want to know what justified the sacrifice – especially that made by those who fell along the way.

Telling people that it was ‘necessary’ will not be enough. Instead, those who remain will require a positive justification that goes beyond ‘mere survival’. It is in the light of that positive justification that all of the preceding decisions need to be evaluated. So, leaders need to ask themselves, ‘is today’s decision going to foreclose on the future we hope to create’. In particular, will my present choice make my preferred future impossible? Will it delegitimise my future leadership?

Finally, leaders need to release themselves from the unrealistic expectation of ‘ethical perfection’. This is not to say that one should be careless in decision making. Rather, it is to recognise a fundamental truth of philosophy: that some ethical dilemmas are so perfectly balanced as to be, in principle, undecidable.

Yet, we must decide. The only reasonable standard to apply in such cases is that we are sincere in our judgement and competent in our capacity to make ethical decisions – a skill that can be learned and supported.

There are particular ethical challenges to be faced by leaders during times such as these. Critical decisions may have to be made alone. Not everything that could be said should be said. There are some options that need to be considered but not voiced – as they would cause unnecessary worry – only to remain dormant.

There are ‘gordian knots’ that may need to be cut rather than carefully unravelled over a period of time that is simply not available. There is the fact that the weaknesses in oneself (and others) will be revealed under pressure – and that unpleasant truths will need to be acknowledged and endured.

At times such as these, the things that sustain good leaders are an unshakeable sense of purpose and a solid core of personal integrity. One might protect others from the harshest of possibilities for as long as possible – but never oneself.

The Ethics Centre is a world leader in assessing cultural health and building the leadership capability to make good ethical decisions in complexity. To arrange a confidential conversation contact the team at consulting@ethics.org.au. Visit our consulting page to learn more.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Health + Wellbeing, Society + Culture

Ethical concerns in sport: How to solve the crisis

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

This tool will help you make good decisions

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture, Business + Leadership, Health + Wellbeing

Make an impact, or earn money? The ethics of the graduate job

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Money talks: The case for wage transparency

BY Simon Longstaff

Simon Longstaff began his working life on Groote Eylandt in the Northern Territory of Australia. He is proud of his kinship ties to the Anindilyakwa people. After a period studying law in Sydney and teaching in Tasmania, he pursued postgraduate studies as a Member of Magdalene College, Cambridge. In 1991, Simon commenced his work as the first Executive Director of The Ethics Centre. In 2013, he was made an officer of the Order of Australia (AO) for “distinguished service to the community through the promotion of ethical standards in governance and business, to improving corporate responsibility, and to philosophy.” Simon is an Adjunct Professor of the Australian Graduate School of Management at UNSW, a Fellow of CPA Australia, the Royal Society of NSW and the Australian Risk Policy Institute.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Ask an ethicist: do teachers have the right to object to returning to school?

Ask an ethicist: do teachers have the right to object to returning to school?

Opinion + AnalysisPolitics + Human RightsRelationships

BY Simon Longstaff The Ethics Centre 4 MAY 2020

In recent weeks, there has been a particularly intense debate about whether or not students should return to the classroom.

This article was first published by Crikey, in their weekly Ask the Ethicist column featuring Dr Simon Longstaff.

Much of that debate has focused on the interests of the children and their families. However, there is a third stakeholder group – the nation’s teachers – who need to be considered. Part ‘essential worker’, part ‘political football’, they have been celebrated on one hand and condemned on the other. So, what are the ethical obligations of those who teach our children during COVID-19.

As a starting point, let’s agree that education is a significant ‘good’ and that children should not be deprived of its benefits unless there are compelling reasons for doing so. Compelling reasons would include the potential risk of infection due to school attendance.

At present, the balance of evidence is that the risk of children becoming infected is low and that they are unlikely to be transmitters of the disease to adults – especially in well-controlled environments. However, why take any risk – if viable alternatives are available?

Here, we should note that the education of children has not been suspended during the crisis. Instead, it has continued by other – ‘online’ – means. This has required a massive effort by the teaching profession to ‘recalibrate’ the learning environment to support distance learning.

We should also note that the ability to provide distance education distinguishes teachers from other essential workers who, of necessity, must provide a face-to-face service. For example, while some doctors can consult with patients using ‘telemedicine’, most health care workers need to be physically present (e.g. when administering a flu injection, or caring for a bed-ridden patient, etc.).

So, if distance learning achieves the same educational outcomes as classroom teaching, teachers would not seem to be under any moral obligation to return to the classroom. However, the Federal Government has recently cited reports suggesting that online learning produces ‘sub-optimal’ outcomes for students (unwelcome news for children living in remote communities and educated by the ‘school of the air’).

If this is true, then it would suggest two things. First that the government should be massively increasing its investment in education for children who have no option but to engage in distance education. Second, that teachers should be heading back into the classroom.

However, what of the teacher who lives with people for whom COVID-19 is a particular threat … the aged and infirm? In those cases, the choice is not just a matter of balancing a public duty as an educator against a preference for personal safety. Rather, the teacher is caught in an ethical dilemma of competing duties.

In such a case, I think it would be reasonable for a teacher to claim they have a conscientious objection to returning to the classroom – grounded in a refusal to be the potential cause of harm to a loved one – especially when the only certain protection for the loved one is that the teacher remain isolated.

You can contact The Ethics Centre about any of the issues discussed in this article. We offer free counselling for individuals via Ethi-call; professional fee-for-service consulting, leadership and development services; and as a non-profit charity we rely heavily on donations to continue our work, which can be made via our website. Thank you.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

A guide to ethical gift giving (without giving to charity)

Explainer

Politics + Human Rights

Ethics Explainer: Just War Theory

Big thinker

Politics + Human Rights

Big Thinker: Peter Singer

Big thinker

Climate + Environment, Relationships

Big Thinker: Ralph Waldo Emerson

BY Simon Longstaff

Simon Longstaff began his working life on Groote Eylandt in the Northern Territory of Australia. He is proud of his kinship ties to the Anindilyakwa people. After a period studying law in Sydney and teaching in Tasmania, he pursued postgraduate studies as a Member of Magdalene College, Cambridge. In 1991, Simon commenced his work as the first Executive Director of The Ethics Centre. In 2013, he was made an officer of the Order of Australia (AO) for “distinguished service to the community through the promotion of ethical standards in governance and business, to improving corporate responsibility, and to philosophy.” Simon is an Adjunct Professor of the Australian Graduate School of Management at UNSW, a Fellow of CPA Australia, the Royal Society of NSW and the Australian Risk Policy Institute.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

The value of a human life

The value of a human life

Opinion + AnalysisHealth + WellbeingPolitics + Human RightsRelationshipsScience + Technology

BY Simon Longstaff The Ethics Centre 1 MAY 2020

One of the most enduring points of tension during the COVID-19 pandemic has concerned whether the national ‘lockdown’ has done more harm than good.

This issue was squarely on the agenda during a recent edition of ABC TV’s Q+A. The most significant point of contention arose out of comments made by UNSW economist, Associate Professor Gigi Foster. Much of the public response was critical of Dr. Foster’s position – in part because people mistakenly concluded she was arguing that ‘economics’ should trump ‘compassion’.

That is not what Gigi Foster was arguing. Instead, she was trying to draw attention to the fact that the ‘lockdown’ was at risk of causing as much harm to people (including being a threat to their lives) as was the disease, COVID-19, itself.

In making her case, Dr. Foster invoked the idea of Quality Adjusted Life Years (QALYs). As she pointed out, this concept has been employed by health economists for many decades – most often in trying to decide what is the most efficient and effective allocation of limited funds for healthcare. In essence, the perceived benefit of a QALY is that it allows options to be assessed on a comparable basis – as all human life is made measurable against a common scale.

In essence, the perceived benefit of a QALY is that it allows options to be assessed on a comparable basis – as all human life is made measurable against a common scale.

So, Gigi Foster was not lacking in compassion. Rather, I think she wanted to promote a debate based on the rational assessment of options based on calculation, rather than evaluation. In doing so, she drew attention to the costs (including significant mental health burdens) being borne by sections of the community who are less visible than the aged or infirm (those at highest risk of dying if infected by this coronavirus).

I would argue that there are two major problems with Gigi Foster’s argument. First, I think it is based on an understandable – but questionable – assumption that her way of thinking about such problems is either the only or the best approach. Second, I think that she has failed to spot a basic asymmetry in the two options she was wanting to weigh in the balance. I will outline both objections below.

In invoking the idea of QALYs, Foster’s argument begins with the proposition that, for the purpose of making policy decisions, human lives can be stripped of their individuality and instead, be defined in terms of standard units. In turn, this allows those units to be the objects of calculation. Although Gigi Foster did not explicitly say so, I am fairly certain that she starts from a position that ethical questions should be decided according to outcomes and that the best (most ethical) outcome is that which produces the greatest good (QALYs) for the greatest number.

Many people will agree with this approach – which is a limited example of the kind of Utilitarianism promoted by Bentham, the Mills, Peter Singer, etc. However, there will have been large sections of the Q+A audience who think this approach to be deeply unethical – on a number of levels. First, they would reject the idea that their aged or frail mother, father, etc. be treated as an expression of an undifferentiated unit of life. Second, they would have been unnerved by the idea that any human being should be reduced to a unit of calculation.

…they would have been unnerved by the idea that any human being should be reduced to a unit of calculation.

To do so, they might think, is to violate the ethical precept that every human being possesses an intrinsic dignity. Gigi Foster’s argument sits squarely in a tradition of thinking (calculative rationality) that stems from developments in philosophy in the late 16th and 17th Centuries. It is a form of thinking that is firmly attached to Enlightenment attempts to make sense of existence through the lens of reason – and which sought to end uncertainty through the understanding and control of all variables. It is this tendency that can be found echoing in terms like ‘human resources’.

Although few might express a concern about this in explicit terms, there is a growing rejection of the core idea – especially as its underlying logic is so closely linked to the development of machines (and other systems) that people fear will subordinate rather than serve humanity. This is an issue that Dr Matthew Beard and I have addressed in the broader arena of technological design in our publication, Ethical By Design: Principles for Good Technology.

The second problem with Dr. Foster’s position is that it failed to recognise a fundamental asymmetry between the risks, to life, posed by COVID-19 and the risks posed by the ‘lockdown’. In the case of the former: there is no cure, there is no vaccine, we do not even know if there is lasting immunity for those who survive infection.

We do not yet know why the disease kills more men than women, we do not know its rate of mutation – or its capacity to jump species, etc. In other words, there is only one way to preserve life and to prevent the health system from being overwhelmed by cases of infection leading to otherwise avoidable deaths – and that is to ‘lockdown’.

…there is only one way to preserve life and to prevent the health system from being overwhelmed by cases of infection leading to otherwise avoidable deaths – and that is to ‘lockdown’.

On the other hand, we have available to us a significant number of options for preventing or minimising the harms caused by the lockdown. For example, in advance of implementing the ‘lockdown’, governments could have anticipated the increased risks to mental health leading to a massive investment in its prevention and treatment.

Governments have the policy tools to ensure that there is intergenerational equity and that the burdens of the ‘lockdown’ do not fall disproportionately on the young while the benefits were enjoyed disproportionately by the elderly.

Governments could have ensured that every person in Australia received basic income support – if only in recognition of the fact that every person in Australia has had to play a role in bringing the disease under control. Is it just that all should bear the burden and only some receive relief – even when their needs are as great as others?

Whether or not governments will take up the options that address these issues is, of course, a different question. The point here is that the options are available – in a way that other options for controlling COVID-19 are not. That is the fundamental asymmetry mentioned above.

I think that Gigi Foster was correct to draw attention to the potential harm to life, etc. caused by the ‘lockdown’. However, she was mistaken not to explore the many options that could be taken up to prevent the harm she and many others foresee. Instead, she went straight to her argument about QALYs and allowed the impression to form that the old and the frail might be ‘sacrificed’ for the greater good.

You can contact The Ethics Centre about any of the issues discussed in this article. We offer free counselling for individuals via Ethi-call; professional fee-for-service consulting, leadership and development services; and as a non-profit charity we rely heavily on donations to continue our work, which can be made via our website. Thank you.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

The ANZAC day lie

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

Those regular folk are the real sickos: The Bachelor, sex and love

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Ask me tell me: Why women think it’s ok to lie about contraception

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Teleology

BY Simon Longstaff

Simon Longstaff began his working life on Groote Eylandt in the Northern Territory of Australia. He is proud of his kinship ties to the Anindilyakwa people. After a period studying law in Sydney and teaching in Tasmania, he pursued postgraduate studies as a Member of Magdalene College, Cambridge. In 1991, Simon commenced his work as the first Executive Director of The Ethics Centre. In 2013, he was made an officer of the Order of Australia (AO) for “distinguished service to the community through the promotion of ethical standards in governance and business, to improving corporate responsibility, and to philosophy.” Simon is an Adjunct Professor of the Australian Graduate School of Management at UNSW, a Fellow of CPA Australia, the Royal Society of NSW and the Australian Risk Policy Institute.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Could a virus cure our politics?

Could a virus cure our politics?

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + LeadershipPolitics + Human Rights

BY Simon Longstaff The Ethics Centre 27 MAR 2020

The COVID-19 pandemic of 2020 will no doubt be remembered for many things.

I wonder if one of the more surprising outcomes will be that our political leaders collectively managed to win back the trust and legitimacy they squandered over the past couple of decades. I hope so – because as we are now seeing in this time of crisis, it really matters.

The past few days have seen Prime Minister Scott Morrison describe panic-shoppers as engaging in behaviour that is “ridiculous” and “un-Australian”. He has had a crack at people who flocked to Bondi Beach in the recent warm weather for not taking seriously the requirements for physical distancing. He is right on both counts. However, his message is blunted by the lack of authority attached to his office. This is part of a larger problem.

The government’s meta-narrative is now one in which responsibility for the nation’s fate is tied to the behaviour of its citizens. The message from our political leaders is clear: ‘You – all of you (the people) – must take responsibility for your choices’.

Again, they are right. It’s just a terrible pity that the potency of the message is undermined by the hypocrisy of the messengers – a group that has refused to take responsibility for pretty much anything – in recent years.

Consider the most recent case of the infamous Sports Rort – in which Government Ministers (including the Prime Minister) offered the ‘Bridget McKenzie’ defence that ‘no laws were broken’. They wriggled and squirmed even further – in an attempt to deflect any and all criticism. Of course, ordinary Australians saw through the evasions and put it all down to political ‘business as usual’.

I recognise that it is unfair to focus on a single incident as indicative of all that has happened to erode trust and legitimacy. McKenzie and Co’s behaviour is just the most recent example of a longer, larger trend. A more equitable reckoning would say to the whole of the political class that we are sick of your blame-shifting, your evasiveness, your self-serving hair-splitting, your back-stabbing, your blatant lies (large and small), your reckless (no, gutless) refusal to accept responsibility for your errors and wrong-doing … your loyalty to the machine rather than to the people whom you are supposed to serve.

The split between ethics and politics was not always so evident. For Ancient Greeks, like Aristotle, each was a different side of a single coin. Ethics dealt with questions about the good life for an individual. Politics considered the good for the life of the community (the polis). The connections were not accidental – they were intrinsic to the understanding of the relationship between people and the communities of which they formed a part. As Umberto Eco once observed, the ancient world was a place of depth populated by heroes. In contrast, we moderns are fascinated by glittering surfaces and find satisfaction in celebrities.

The shallowness of much of modern life has fed into our politics – an arena within which marketing spin too often takes precedence over substance. Some seek to excuse this tendency by saying that our politicians merely reflect the society they represent. It is said that we should demand nothing more of political leaders than what we expect of ourselves. Really? Is that really good enough?

So, how should we respond to this?

Let’s write to our politicians, phone their offices … bombard them with messages of encouragement. Let’s ask them to rise to the occasion – to prove to us (and perhaps to themselves) what they could be.

Let’s appeal to the neglected idealist living buried beneath the callouses. Let’s tell them that they are needed; that they have a noble calling. Let’s enrol them in our dream of a better democracy – one that truly serves the interests of its citizens. Let them be our champions – let them drive out of their ranks anyone who refuses to be and do better.

Let’s imagine what it would be like if, at the end of this year, we were proud of our politicians and the quality of government that they had offered us at a time of crisis.

You can contact The Ethics Centre about any of the issues discussed in this article. We offer free counselling for individuals via Ethi-call; professional fee-for-service consulting, leadership and development services; and as a non-profit charity we rely heavily on donations to continue our work, which can be made via our website. Thank you.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Politics + Human Rights

‘Eye in the Sky’ and drone warfare

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Why do good people do bad things?

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

After Christchurch

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

Did Australia’s lockdown leave certain parts of the population vulnerable?

BY Simon Longstaff

Simon Longstaff began his working life on Groote Eylandt in the Northern Territory of Australia. He is proud of his kinship ties to the Anindilyakwa people. After a period studying law in Sydney and teaching in Tasmania, he pursued postgraduate studies as a Member of Magdalene College, Cambridge. In 1991, Simon commenced his work as the first Executive Director of The Ethics Centre. In 2013, he was made an officer of the Order of Australia (AO) for “distinguished service to the community through the promotion of ethical standards in governance and business, to improving corporate responsibility, and to philosophy.” Simon is an Adjunct Professor of the Australian Graduate School of Management at UNSW, a Fellow of CPA Australia, the Royal Society of NSW and the Australian Risk Policy Institute.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Rationing life: COVID-19 triage and end of life care

Rationing life: COVID-19 triage and end of life care

Opinion + AnalysisHealth + WellbeingRelationships

BY Simon Longstaff The Ethics Centre 23 MAR 2020

Many Australians are encountering the phenomenon of rationing for the first time in their lives. For the moment, rationing is sporadic and confined to items like toilet paper and beans. However, how will we respond when rationing moves from consumables to life itself?

Given the finite number of beds in intensive care units, respirators, etc. in Australia, the harsh truth is that if there is mass contagion, giving rise to critical illness on a broad scale, there will not be enough medical resources to sustain the lives of all who need care.

In those circumstances, medical staff and families will need to exercise triage – put simply, the practice of prioritising access to scarce medical resources. Not everyone will be chosen. Some of those at the end of the line will die.

This is the harsh reality behind abstract talk of ‘flattening the curve’. Governments and their advisers are now working to reduce the number of COVID-19 infections in the hope that they can prevent the overloading of our limited resources. In doing so, they recognise that the risks cannot be overcome by throwing money at the problem.

There is an upper limit in terms of equipment and trained personnel – there is just not an endless supply of either and no amount of money can solve that problem once the number of people seeking care exceeds the effective places available.

That is why every person must now do what they can to minimise the risk of mass infection. Doing so may not confer an individual benefit. However, the decision to wash one’s hands regularly and practice prudent forms of social distancing may make all the difference when it comes to avoiding the tipping point between a medical system that can cope and one that is forced to engage in triage.

So, how will clinicians choose if the worst fears are realised? In medical ethics, the general approach to triage is to prioritise according to two dimensions. First, a patient will be assessed in terms of their physical capacity to respond to the treatment that is available. Put simply, the less likely a person is to respond to medical care, the lower they will be ranked on the list. In a time of scarcity, there is little justification for devoting precious resources to cases that are judged to be futile.

Second, a patient will be assessed in terms of their relative circumstances – including age, stage of life, etc. For example, a forty year old parent of three children will rank higher than a seventy year old with no dependents. Both principal factors intersect – and will be qualified (to some degree) by secondary concerns – such as the relative burden of any proposed treatment on the patient.

If the worst predictions come true, such choices may need to be made on a daily basis. It will not only be the doctors who have to decide. Families will also be drawn into the decision making process. Should that time arise, it will be essential that we all embrace some fundamental distinctions. For example, there is a profound difference between preserving life on the one hand and merely extending the process of dying, on the other.

The medical technology used in both cases is the same. It is the ethical discernment that makes the difference. If pressure mounts on intensive care units, then we can expect more families and loved ones to be asked if continuing treatment is not only futile but also denying another person a chance of life. Who of us is prepared for such a conversation?

None of this is meant to suggest that some lives are intrinsically more valuable than others. They are not – we are all equal in our possession of fundamental dignity. Nor does resort to triage imply indifference to the wellbeing of those who cannot receive life saving care. Those who miss out will be given the most compassionate care available as they die. Nobody need suffer.

Finally, we should spare a thought for those who may be called to make these difficult decisions. The physical, emotional and spiritual toll will be immense.

No amount of reason or decision making aids can prevent the abrasive effects on the human psyche of triage. Medical professionals, families, members of the wider community … we will all need support.

I hope that we can avoid arriving at a point where such decisions have to be made. It is the job of government to ensure that we are protected from such times. Whether they have done enough, early enough is yet to be decided.

In the meantime, if ever you wondered about the relevance of ethics to everyday life – just look around you.

You can contact The Ethics Centre about any of the issues discussed in this article. We offer free counselling for individuals via Ethi-call; professional fee-for-service consulting, leadership and development services; and as a non-profit charity we rely heavily on donations to continue our work, which can be made via our website. Thank you.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Business + Leadership

Teachers, moral injury and a cry for fierce compassion

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

The truths COVID revealed about consumerism

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Health + Wellbeing

Navigating a workforce through stressful times

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships

The pivot: Mopping up after a boss from hell

BY Simon Longstaff

Simon Longstaff began his working life on Groote Eylandt in the Northern Territory of Australia. He is proud of his kinship ties to the Anindilyakwa people. After a period studying law in Sydney and teaching in Tasmania, he pursued postgraduate studies as a Member of Magdalene College, Cambridge. In 1991, Simon commenced his work as the first Executive Director of The Ethics Centre. In 2013, he was made an officer of the Order of Australia (AO) for “distinguished service to the community through the promotion of ethical standards in governance and business, to improving corporate responsibility, and to philosophy.” Simon is an Adjunct Professor of the Australian Graduate School of Management at UNSW, a Fellow of CPA Australia, the Royal Society of NSW and the Australian Risk Policy Institute.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

The Festival of Dangerous Ideas has been regrettably cancelled

The Festival of Dangerous Ideas has been regrettably cancelled

Opinion + AnalysisSociety + Culture

BY Simon Longstaff 16 MAR 2020

It was at the last Festival of Dangerous Ideas in November 2018, that our keynote speaker – celebrated writer, actor and bon vivant Stephen Fry – made the prophetic statement, “It’s not dangerous ideas that should concern us, it’s dangerous realities.”

We liked the line so much we used it as the theme for our tenth festival, scheduled to take place at Sydney Town Hall on 3-5 April. But as of today, we’re devastated to advise that the Festival won’t be happening. Like thousands of other events, ours may no longer proceed following the NSW Government’s (Minister of Health) ban of non-essential gatherings of 500 people or more.

Faced with the rapidly evolving situation around COVID-19 and relying on the best available medical advice, this is a possibility we’ve been grappling with, and agonising over, for the last two weeks – until the point where the choice was taken from our hands.

Although this decision is an incredible blow, the health of our audience, staff, speakers, artists and the wider public, is what matters most.

For some ticket holders, this cancellation will probably come as a relief. There’s already a high level of anxiety in the community about attending events of any kind. In the greater scheme of things, missing a couple of festival sessions – or a night at the theatre – is no more than a minor inconvenience. It might also be experienced as a reprieve for the speakers who were booked to travel halfway around the world to attend the Festival; navigating travel bans and the risk of illness, flight delays or mandatory quarantine periods to do so.

FODI takes many months – and thousands of hours – of creativity and painstaking human effort to become reality. If you had attended the festival, you would have heard from over 50 speakers, including exiled activist Edward Snowden (no stranger to self-isolation), climate change journalist, David Wallace-Wells, the celebrated Harvard professor, Michael Sandel, and technology critic, Evgeny Morozov. You would have heard Lindy Chamberlain-Creighton was to talk about her experience in one of the greatest miscarriages of justice in Australian history. And you would have encountered the extraordinary contrarian, Roxane Gay.

Beyond talks – and in the realm of the arts – you could have engaged with a remarkable new work called Unforgivable, featuring youth activists and a young 18-person strong indigenous choir. There was also going to be an opportunity for anyone to interact with PIG – a giant transparent piggybank into which people could donate (or withdraw) money in the full glare of public scrutiny. PIG was to have sat outside the QVB in the heart of Sydney for an entire week, prompting conversation about generosity and the hierarchy of human needs. It’s a conversation that has taken on a new relevance, today.

Major events like ours operate on a financial knife-edge. Just breaking even is a challenge in the best of times. So, the cancellation of FODI is not only heart-breaking. It also risks being financially crippling. Given this, we are asking our supporters, sponsors and ticket holders to consider donating their contributions to The Ethics Centre. Every cent will help us survive this financial upheaval and carry on our work.

If you would like to support The Ethics Centre, you can do so here.

Personally, our team is dealing with a deep sense of disappointment – that something we’ve been working towards for a long time, is now never going to happen.

That said, although we are down, we are definitely not out! FODI will be back – its tenth anniversary merely postponed until better times. It’s the original festival for stroppy people who want to push the boundaries. And it remains the best!

We thank all of our speakers, staff, supporters and ticket holders for their patience and understanding.

This dangerous reality arrived ahead of schedule.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture

10 films to make you highbrow this summer

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Society + Culture

A win for The Ethics Centre

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Health + Wellbeing, Society + Culture

Ethical concerns in sport: How to solve the crisis

Big thinker

Relationships, Society + Culture

Big Thinker: Socrates

BY Simon Longstaff

Simon Longstaff began his working life on Groote Eylandt in the Northern Territory of Australia. He is proud of his kinship ties to the Anindilyakwa people. After a period studying law in Sydney and teaching in Tasmania, he pursued postgraduate studies as a Member of Magdalene College, Cambridge. In 1991, Simon commenced his work as the first Executive Director of The Ethics Centre. In 2013, he was made an officer of the Order of Australia (AO) for “distinguished service to the community through the promotion of ethical standards in governance and business, to improving corporate responsibility, and to philosophy.” Simon is an Adjunct Professor of the Australian Graduate School of Management at UNSW, a Fellow of CPA Australia, the Royal Society of NSW and the Australian Risk Policy Institute.

Ethics in a time of coronavirus

Ethics in a time of coronavirus

Opinion + AnalysisHealth + WellbeingPolitics + Human RightsRelationships

BY Simon Longstaff The Ethics Centre 12 MAR 2020

The response to the novel coronavirus COVID-19 (now called severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2, or SARS-CoV-2) has been fascinating for a number of reasons. However, two matters stand out for me.

The first matter concerns the way that our choice of narrative framework shapes outcomes. From what we know of SARS-CoV-2 it is highly infectious and produces mortality rates in excess of those caused by more familiar forms of coronavirus, such as those that cause the common cold. However, given that ‘novelty’ and ‘danger’ are potent tropes in mainstream media, most coverage has downplayed the fact that human beings have lived with various forms of coronavirus for millennia.

The more familiar we are with a risk, the more likely we are to manage it through a measured response. That is, we avoid the kind of panicky response that leads people to hoard toilet paper, etc. We can see how a narrative of familiarity works, in practice, by comparing the discussion of SARS-CoV-2 with that of the flu.

John Hopkins reports that an estimated 1 billion cases of flu (caused by a different type of virus) lead to between 291,000 and 646,000 fatalities worldwide each year. That is the norm for flu. Yet, our familiarity with this disease means that the world does not shut down each flu season. Rather than panic, we take prudent measures to manage risk.

I do not want to understate the significance of SARS-CoV-2, nor diminish the need for utmost care and diligence in its management. This is especially so given human beings do not possess acquired immunity to this new virus (which is mutating as it spreads). Furthermore, SARS-CoV-2 is currently thought to generate mortality rates greater than most strains of the flu.

However, despite this, I wonder if society would have been better served by locating this new virus on the spectrum of diseases affecting humanity – rather than as a uniquely dangerous new threat.

This brings me to the second matter of interest that I think worth mentioning. Like many others, I have been struck by the universal commitment of Australia’s leading politicians to legitimise their decisions by relying on the advice of leading scientists.

I do not know of a single case of a politician refusing to accept the prevailing scientific consensus. As far as I know, there has been nothing said along the lines of, “all scientific truth is provisional” or “some scientists disagree”, etc. I have not heard politicians denying the need to take action because it might put some jobs at risk. Nor has anyone said that action is futile ‘virtue signalling’ because a tiny nation, like Australia, can hardly affect the spread of a global pandemic.

As such, I have been left wondering how to explain our politicians’ commitment to act on the basis of scientific advice when it comes to a global threat such as presented by SARS-CoV-2 – but not when it comes to a threat of equal or greater consequence such as presented by global warming.

Taken together – these two issues raise many important questions. For example: are we only able to mount a collective response under conditions of imminent threat? If so, is this why politicians so often play upon our fears as the means for securing our agreement to their plans? Does this approach only work when the risks can be framed in terms of our individual interests – and perhaps those of our immediate families – rather than the common good? Or, more hopefully, can we embrace positive agendas for change?

For my part, I still believe that people are open to good arguments … that they can handle complex truths – if only they are presented in accessible language by people who deserve to be trusted. It’s the work of ethics to make this possible.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Politics + Human Rights

‘Eye in the Sky’ and drone warfare

Explainer

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Values

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Women must uphold the right to defy their doctor’s orders

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

Meet Eleanor, our new philosopher in residence

BY Simon Longstaff

Simon Longstaff began his working life on Groote Eylandt in the Northern Territory of Australia. He is proud of his kinship ties to the Anindilyakwa people. After a period studying law in Sydney and teaching in Tasmania, he pursued postgraduate studies as a Member of Magdalene College, Cambridge. In 1991, Simon commenced his work as the first Executive Director of The Ethics Centre. In 2013, he was made an officer of the Order of Australia (AO) for “distinguished service to the community through the promotion of ethical standards in governance and business, to improving corporate responsibility, and to philosophy.” Simon is an Adjunct Professor of the Australian Graduate School of Management at UNSW, a Fellow of CPA Australia, the Royal Society of NSW and the Australian Risk Policy Institute.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

CoronaVirus reveals our sinophobic underbelly

CoronaVirus reveals our sinophobic underbelly

Opinion + AnalysisHealth + WellbeingPolitics + Human RightsRelationships

BY Simon Longstaff The Ethics Centre 6 MAR 2020

A virus knows no race. It is indifferent to your religion, your culture and your politics. All a virus ‘cares about’ is your biology … For that, one human is as good as any other.

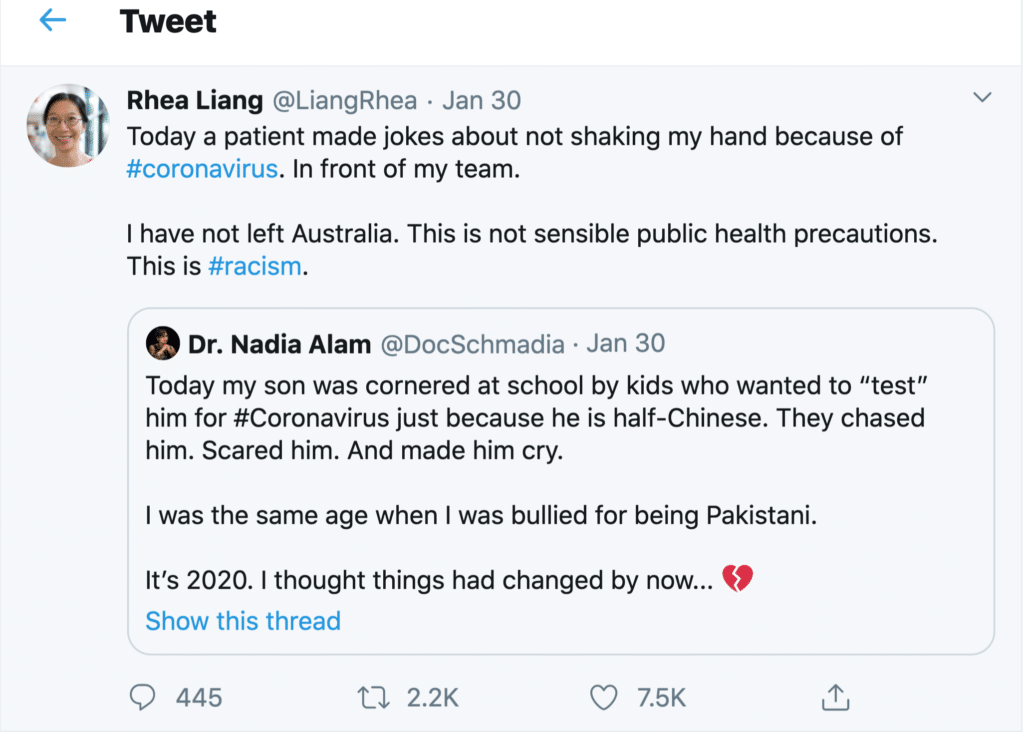

Despite this, it’s easy enough to find recent reports of Australians experiencing discrimination for no reason other than their Chinese family heritage.

Such attacks are examples of racism – the irrational belief that an individual or group possesses intrinsic characteristics that justify acts of discrimination. That this is occurring is not in doubt.

For example, Australia’s Chief Medical Officer, Professor Brendan Murphy has seen enough of such behaviour to make explicit reference to the phenomena, labelling xenophobia and racial profiling as “completely abhorrent”.

Professor Murphy’s position is one of principle. However, there is also a practical aspect to his admonition. Managing the risks of an outbreak of a pathogen like the novel coronavirus COVID-19 requires health officials and the wider community to make rational choices based on an accurate assessment of risk. Racism is irrational. It distorts judgement and draws attention away from where the risks really lie. Ethically it is wrong. Medically, it is idiotic and dangerous.

This rise in racism, prompted by the emergence of COVID-19, reveals how thin the veneer of decency is that keeps latent racist tendencies in check. It seems that, given half-a-chance, the mangy old dog of Sinophobia is ready to raise its head, no matter how long it has laid low.

Of course there is nothing new about Sinophobia in Australia. Fear of the ‘yellow peril’ is woven through the whole of Australia’s still-unfolding colonial history. Many factors have stoked this fear, including: persistent doubts about the legitimacy of British occupation of an already settled continent, ignorance of (and indifference to) Chinese history and culture, the European cultural chauvinism that such ignorance fosters, the belief that numerical supremacy is, ultimately, a determining force in history, the need to find scapegoats when the dominant culture falters, and so on.

Whatever the historical cause of this persistent fear, the present ‘trigger’ is the inexorable rise of China as an economic and military super power – a power that is increasingly inclined to demand (rather than earn) deference and respect.

The situation is made more volatile by the growing tendency for the China of President Xi Jinping to link its power and success to what is uniquely ‘Chinese’ about its history and character. Add to this a broadly accepted Chinese cultural preference for harmony and order and the nation is often presented as if it is a ‘monolithic whole’ – not just in terms of its autocratic government but in its essential character.

Unfortunately, all of this feeds the beast of racist prejudice. Those who feel threatened by the changing currents of history seize on even the flimsiest threads of difference and use these to weave a narrative of ‘us’ and ‘them’ – in which others are presented as being essentially and irremediably different. This is the racists’ central trope – that difference is more than skin deep! Biology makes you one of ‘us’ or you are not.

It’s nonsense. Yet, it’s a nonsense that sticks in some quarters, especially during times of uncertainty such as this; when the general public is feeling betrayed by the elites, when institutions have lost trust and have weakened legitimacy and when increasing numbers of people fear for their future and that of their families.

Unfortunately, tough times provide fertile ground for politicians who are willing to derive electoral dividends by practising the politics of exclusion. It is a cheap but effective form of politics in which people define their shared identity in terms of who is kept outside the group.

It is far harder to practise the politics of inclusion – in which disparate groups find a common identity in the things they hold in common. This too can work, but it takes great energy and superior skills of leadership to achieve this outcome. Yet, it is the latter approach that Australia must look for, if only as a matter of national self-interest.

This is because racist attacks against Australians of Chinese descent also have a significant national security dimension. As I have written elsewhere, social cohesion is a vital component of a nation’s ‘soft power’ when defending against foes who covertly seek to ‘divide and conquer’.

The risk of such attacks is increasing as the world drifts back to a pre-Westphalian strategic environment in which the international, rules-based order breaks down and nations freely interfere with the domestic affairs of their rivals. In these circumstances, the last thing Australia needs is deepening divisions based on spurious beliefs about supposed racial deliveries.

Those who create or exploit those divisions wound the body politic, weaken our defences and undermine the public interest.

All of that said, it is important not to overstate the dimensions of the problem. Australia is a notable successful multicultural nation where harmonious relations prevail. This is despite there being an undercurrent of racism that has been more or less visible throughout Australia’s modern history.

Racism is never justified. Not by the fact that it is found to the same degree in other societies, and not even when its manifestation is rare. Although it offers little comfort, it should also be acknowledged that discrimination is as much a product of other forms of prejudice concerning religion, gender, culture, etc.

We have the capacity to do and be better. This is a choice we can and should make for the sake of our fellow citizens – whatever their background – and in the interests of the nation as a whole.

So, given that China is not likely to take a backwards step and Australians of Chinese background cannot (and should not) disguise their heritage, how should we respond to the latest bout of Sinophobia?

Attack prejudice with fact

A first step should be to follow the example of Australia’s Chief Medical Officer and attack prejudice with the facts. Professor Murphy’s example showed how facts about medicine can be deployed to calm fears and neutralise racist myths. This approach should be extended to other areas. For example, more should be known of the long history and extraordinary contribution of Australians of Chinese heritage.

This account should not merely tell the story of elite performance, economic contribution, etc. It should also speak of those who have fought in Australia’s wars, built its infrastructure, educated its children, nursed its sick … and so on. In short, we need to see more of the extraordinary in the ordinary.

Reframe the narrative

Second, we need to reframe the narrative about China and the Chinese. Today, most commentary portrays China as both a security threat and an economic enabler. It is both. However, this is only a small part of the story.

For the most part, we see little of the life of the Chinese people. We are largely ignorant of the achievements of their remarkable civilisation. One might think that the closeness of the economic relationship might be a positive factor. However, regular reporting about Australia’s economic dependence on China, is not helping the situation.

I know that this will seem counter-intuitive to some. However, the more we speak of Chinese students propping up our universities, of Chinese tourists sustaining our tourism industry and of Chinese consumers boosting our agricultural exports … the more it makes it sound as if the Chinese are little more than an economically essential ‘necessary evil’ – a ‘commodity’ that comes and goes in bulk.

This view of the Chinese negatively influences attitudes towards Australia’s own citizens of Chinese descent. Fortunately, a solution to the ‘commodification’ of the Chinese is at hand, if only we wish to embrace it. The large number of Chinese students who study in Australia offer an opportunity to build better understanding and stronger relationships.

Unfortunately, the Chinese student experience in Australia is reported not to be as positive as it should be. Too many arrive without the English language skills to engage more widely with the community. Too many find themselves lonely and isolated. Too many find solace in sticking with those they know and understand. With some justification, large numbers feel as if they are little more than a ‘cash cow’.

Invest in ethical infrastructure

Third, we need to invest in Australia’s own ‘ethical infrastructure’ – much of which is damaged or broken. We need to repair our institutions so that they act with integrity and merit the trust of the wider community. We need to work on the core values and principles that underpin social cohesion.

Part of this task must be to come to terms with the truth about the colonisation of Australia. This is not to invoke the ‘black arm band’ view of history. The truth is both good and bad. However, whatever its character, our truth remains untold. I sincerely believe that Australia’s ‘soft power’ is weaker than it would otherwise be, if only we could address this unfinished business.

Alleviate fear

Fourth and finally, the measures outlined above will be ineffective unless we also name the latent fears of average Australians. People across the nation want these ‘bread and butter’ issues to be acknowledged and addressed:

- How safe is my job?

- If I lose my current job, will I find another?

- If I can’t find another job, how will I pay my bills?

- Will I be cared for if I get sick?

- Will my children get an education that equips them to live a good life in the future?

- Can I move about with relative ease and efficiency?

- How will the nation feed itself?

- Are we safe from attack?

- Who can step in cases of natural disaster or man-made calamity?

- Why are our leaders not held to account when we are?

- Why can’t I be left alone to do as I please?

- Who cares about me and those I care about?

Failure to speak to the truth of these deep concerns leaves the field wide open for the lies of those who would stoke the fires of racism.

Unravel the complexities of the political relationship between China and Australia at ‘The Truth About China’, a panel conversation at The Festival of Dangerous Ideas, Saturday 4 April. Tickets on sale now

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Science + Technology

Ukraine hacktivism

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing

Tough love makes welfare and drug dependency worse

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Moving on from the pandemic means letting go

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

The Bear and what it means to keep going when you lose it all

BY Simon Longstaff

Simon Longstaff began his working life on Groote Eylandt in the Northern Territory of Australia. He is proud of his kinship ties to the Anindilyakwa people. After a period studying law in Sydney and teaching in Tasmania, he pursued postgraduate studies as a Member of Magdalene College, Cambridge. In 1991, Simon commenced his work as the first Executive Director of The Ethics Centre. In 2013, he was made an officer of the Order of Australia (AO) for “distinguished service to the community through the promotion of ethical standards in governance and business, to improving corporate responsibility, and to philosophy.” Simon is an Adjunct Professor of the Australian Graduate School of Management at UNSW, a Fellow of CPA Australia, the Royal Society of NSW and the Australian Risk Policy Institute.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Respect for persons lost in proposed legislation

Respect for persons lost in proposed legislation

Opinion + AnalysisPolitics + Human RightsSociety + Culture

BY Simon Longstaff The Ethics Centre 19 FEB 2020

The Ethics Centre is a strong supporter of human rights. As such, we agree with the principal purpose of the draft Religious Discrimination Bill (2019) legislation – which is to outlaw discrimination against all persons on the basis of their religion. However, we also argue that the exposure draft is deficient in a number of important ways.

We recently made a submission articulating these concerns in response to the second exposure draft of the proposed legislation.

Core to the submission is our belief that human rights form a whole and are indivisible. That is, we are disinclined to support legislation that creates broad, general exceptions to the principle of non-discrimination. This is especially so when the proposed exceptions risk abrogating the human rights of one group in favour of another.

It’s important to make it clear that the Centre’s approach is not based on a naïve belief that human rights cohere without tension. We know that this is not the case – and understand that religion is, by its very nature, a special case.

This flows from the fact that every religion makes rival, exclusive and absolute truth claims that resist any form of independent evaluation.

Add to this religion’s appeal to transcendent authority, its inclination to order the lives of its adherents and the emotional and spiritual investment it requires of individual and communal belief – and it’s not surprising that difficulties arise not only between religions but in connection with the expression of other human rights.

Our submission seeks to affirm the universal principle of ‘respect for persons’ and to propose criteria for limiting (without totally restricting) the extent to which religious belief can be used as a justification for discrimination.

‘Respect for persons’ is the ethical requirement that we each recognise the intrinsic dignity of every other person – irrespective of their, gender, sex, race, religion, age … or any other non-relevant discriminator. It is this principle that underpins all human rights – and cannot be set aside without undermining the whole edifice.

Given this, we argue that any exception to the prohibition of discrimination that is accorded to people of faith must be severely restricted. That is, lawful discrimination, by people of faith, must only be allowed to the extent strictly necessary to avoid material harm to the religious sensibilities of those affected.

In short: we set a very high bar for those seeking to discriminate against others in the name of religion.

For example, there is a good case for allowing a religious school to discriminate against a person seeking employment as its Principal while concurrently rejecting the religious beliefs that inform the school’s defining ethos.

However, there is no good reason for applying such a test to the employment of a member of the same school’s maintenance team. Nor is there any justification for discriminating against a person based, say, on their sexual orientation if, in all other respects, the person aligns with the religious beliefs of the school – as understood by a significant number of believers.

This brings us to another aspect of the Centre’s submission – that discrimination based on religion only be allowed where there is broad consensus, amongst the faithful, that a belief is a legitimate expression of their religion. This should help avoid giving protection to those who occupy the extreme fringes of religious belief.

Finally, none of the above should be read as justifying restrictions on religious belief. On the contrary, we support the right of people to believe whatever they like. Furthermore, we encourage people to act in accordance with a well-informed (and well-formed) conscience.

We also urge people to realise that to act in good conscience entails the possibility of being punished if your conduct is found to be contrary to law. Such is the case of conscientious objectors who resist conscription into the armed forces, or Roman Catholic priests who choose to respect the ‘seal of the confessional’ even if the law compels them to disclose specified admissions by penitents.

This is the balance that a society needs to maintain: respecting the moral courage of those whose religious beliefs compel them to act in a manner that society must prohibit for the sake of all.

For those who are interested, The Ethics Centre’s submission on the proposed legislation will be published by the Commonwealth Attorney General’s Department in due course.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships, Society + Culture

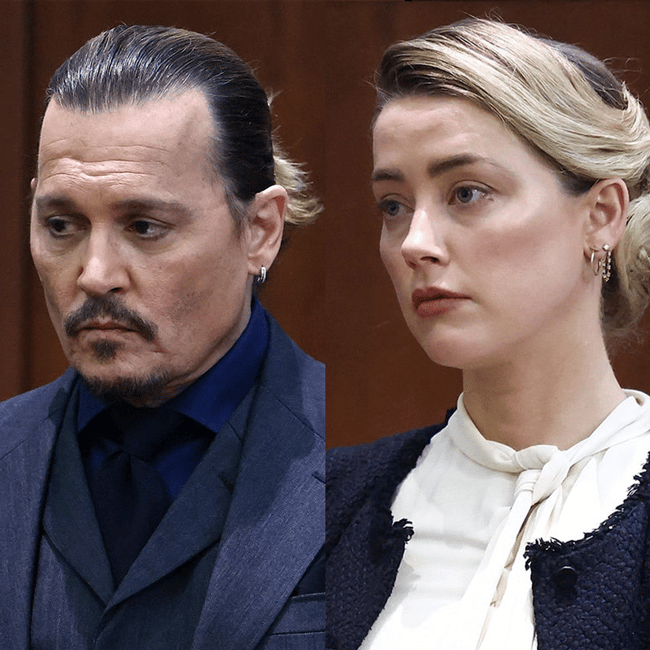

You won’t be able to tell whether Depp or Heard are lying by watching their faces

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

Sportswashing: How money and politics are corrupting sport

Explainer

Politics + Human Rights

Ethics Explainer: Anarchy

Explainer

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Power

BY Simon Longstaff

Simon Longstaff began his working life on Groote Eylandt in the Northern Territory of Australia. He is proud of his kinship ties to the Anindilyakwa people. After a period studying law in Sydney and teaching in Tasmania, he pursued postgraduate studies as a Member of Magdalene College, Cambridge. In 1991, Simon commenced his work as the first Executive Director of The Ethics Centre. In 2013, he was made an officer of the Order of Australia (AO) for “distinguished service to the community through the promotion of ethical standards in governance and business, to improving corporate responsibility, and to philosophy.” Simon is an Adjunct Professor of the Australian Graduate School of Management at UNSW, a Fellow of CPA Australia, the Royal Society of NSW and the Australian Risk Policy Institute.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

McKenzie... a fractured cog in a broken wheel

McKenzie… a fractured cog in a broken wheel

Opinion + AnalysisPolitics + Human Rights

BY Simon Longstaff The Ethics Centre 18 FEB 2020

In many cases, the response to scandal is often as instructive as an assessment of its cause. So it has proved to be in the case of the issues that led to the resignation of Senator Bridget McKenzie as a Federal Government Minister.

The findings of the Auditor General unleashed a fair amount of anger and disgust – especially amongst community groups who were deemed to be meritorious recipients of funding but who missed out due to political considerations.

While I understand the outrage, strong emotions can make us blind to areas of ethical importance. As citizens, we need to notice the rapid normalisation of deviance that is eroding the foundations of our representative democracy.

In this, we should look to the insights of Edmund Burke who recognised the role played by traditions and conventions in maintaining the integrity of institutions and societies.

Those who know my writings might be surprised to find me ‘channelling’ Burke. For three decades, I have warned of the perils of unthinking custom and practice. But note that my target has always been practices and arrangements that are unthinking. I am a great admirer of customs and practices that derive their life from a conscious application of purpose, values and principles.

Too often, it is the dead hand of tradition that leads institutions to betray their underlying purposes, lose legitimacy and invite revolution. In that sense, I think that Edmund Burke and I would be in perfect accord.

I also think that Burke would be deeply concerned by the radical turn away from convention taken by the government of Prime Minister, Scott Morrison, in response to the ANAO’s ‘Sports Rort’ Report.

The government’s response has been marked by a persistent refusal to acknowledge and uphold, in practice, a couple of fundamental principles. First, that public power and monies (levied by taxes) should be used exclusively for public purposes. Second, that Ministers are responsible for all that is done in their name.

Instead, the government and its representatives have sought to distract the public by laying some false trails. They have claimed that ‘no rules were broken’. They have argued that the ‘ends justified the means’. They have suggested that the Minister should be excused from responsibility for the activities of her advisers (and possibly advisers in the offices of other ministers) who shaped decisions according to the political interests of the Coalition parties.

The fact that Senator McKenzie resigned over a ‘technical breach’ of the Ministerial Code – without any sense of remorse or censure for the way she exercised discretion in the allocation of public funds – has reinforced the public’s perception that politics and ethics have become estranged.

Just the other day someone said to me, “I can’t believe you expected anything different …”. The person then paused, in mid-sentence, and said, “Did I really just say that …? What has happened to us?”. Indeed, how have we come to accept such low standards as ‘normal’? When will we realise that we are being robbed of our reasonable expectations as citizens in a democracy?

Our government’s behaviour may deserve moral censure. However, we should not let this obscure the fact that its response to the ‘Sports Rort’ reveals a woeful lack of commitment to the preconditions for a functioning representative democracy. It is this, more than anything else, that should really worry us.

“Our government’s behaviour may deserve moral censure. However, we should not let this obscure the fact that its response to the ‘Sports Rort’ reveals a woeful lack of commitment to the preconditions for a functioning representative democracy.”

One result of a lack of clear commitment to ethics within government has been the growing demand for a Federal Integrity Commission. The idea is popular with the general public – who are sick of being held accountable for their conduct while watching the most powerful people in the nation letting each other off the hook. Given this, the major political parties are committed to the creation of this new, independent oversight body.

Personally, I think it incredibly sad that it has come to this. That multiple generations of politicians, from across the political spectrum, have made this necessary is an indictment of their stewardship of our democratic institutions.

However, if it is to be done, then it must be done well. There is no point in the Parliament putting in place a ‘paper tiger’ limited to reviewing the most extreme cases of ethical failure by the smallest possible subset of public officials. It is for that reason, I support the Beechworth Principles which were launched this week.

We deserve governments that earn our trust and preserve their legitimacy. Is that really too much to ask of our politicians?

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

A good voter’s guide to bad faith tactics

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships, Society + Culture

Punching up: Who does it serve?

Big thinker

Politics + Human Rights

Big Thinker: John Locke

Big thinker

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships