We need to step out of the shadows in order to navigate a complex world

We need to step out of the shadows in order to navigate a complex world

Opinion + AnalysisSociety + Culture

BY Simon Longstaff 14 MAY 2025

One of the most potent allegories ever to be developed by a philosopher is Plato’s allegory of ‘the cave’.

The story centres around a community of people who are bound, from head to toe, while facing a wall. For the entirety of their lives, nothing is to be seen other than two-dimensional shadows cast by whatever passes between their backs and the source of illumination (the sun or a raging fire). Knowing of no other way to see the world, the chained viewers believe that all of reality is represented by the shadows they perceive. Worse still, they have no concept of ‘shadows’ that might shake their conviction that what they see is ‘real’.

Then, one fateful day, a single individual manages to break their bonds. Free to roam, they encounter a three-dimensional world of colour. Then – only then – do they realise that their life has been defined by error; that the shadows that they once took to represent the whole of reality are nothing more than a simplistic rendering of something far more complex, compelling and beautiful. Inspired by this new understanding, the person returns to liberate others. At first, they are mocked, labelled a lunatic and accused of heresy. Eventually, enough people are freed from their shackles and learn to see.

I used to think it was obvious that everyone would jump at the opportunity to be liberated from ignorance. Most of my working life has been animated by Socrates’ great maxim that, “the unexamined life is not worth living”. After all, is it not the capacity to acknowledge – but also to transcend – our instincts and desires, that makes us human? Is it not obvious that a refusal to examine our lives and to make conscious choices, is actually a refusal to embrace the fullness of our humanity? And is it not the task of philosophy – especially ethics – to equip us so that we might better manage complexity once the chains of unthinking custom and practice are loosened?

As it happens, the ‘shadows’ are far more attractive than I had supposed. In a world of increasing complexity, I have been surprised to see an increasing number of people yearning for their chains in the hope that they might recover the simpler two-dimensional world that they have left behind. I see this in an urge to force what is inherently complex into a deceptively simple form. This is an escape back into a world of shadows – an easier path than that of learning how better to deal with complex reality.

The truth is that most of the important things in life are complex. The ‘messiness’ of the human condition comes from the fact that we have the capacity to make conscious (and conscientious) choices in circumstances of radical uncertainty.

Too often, the choice is not between ‘good’ and ‘bad’ or ‘right’ and ‘wrong’. Values and principles of equal weight can pull us in opposite directions. It is easy to become ‘stuck’, or to face the prospect that the ‘least bad’ alternative is your only viable choice.

Ethics can help us address this messy reality. Not the impossible, flawed ideal of ‘ethical perfection’ – but rather being equipped to live in the uncomfortable light of reality … in all its complexity. We need people to become ‘champions for the common good’. For without dedicated care and attention, our ethical foundations begin to erode.

Ours is a complex world. But when we embrace the ethical dimension of our lives; when we step into the light, nothing can overwhelm and everything becomes possible.

With your support, The Ethics Centre can continue to be the leading, independent advocate for bringing ethics to the centre of everyday life in Australia. Click here to make a tax deductible donation today.

BY Simon Longstaff

After studying law in Sydney and teaching in Tasmania, Simon pursued postgraduate studies in philosophy as a Member of Magdalene College, Cambridge. In 1991, Simon commenced his work as the first Executive Director of The Ethics Centre. In 2013, he was made an officer of the Order of Australia (AO) for “distinguished service to the community through the promotion of ethical standards in governance and business, to improving corporate responsibility, and to philosophy.”

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Climate + Environment, Politics + Human Rights, Relationships, Society + Culture

The youth are rising. Will we listen?

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Society + Culture

There’s something Australia can do to add $45b to the economy. It involves ethics.

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture, Business + Leadership

How to tackle the ethical crisis in the arts

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture

We are pitching for your pledge

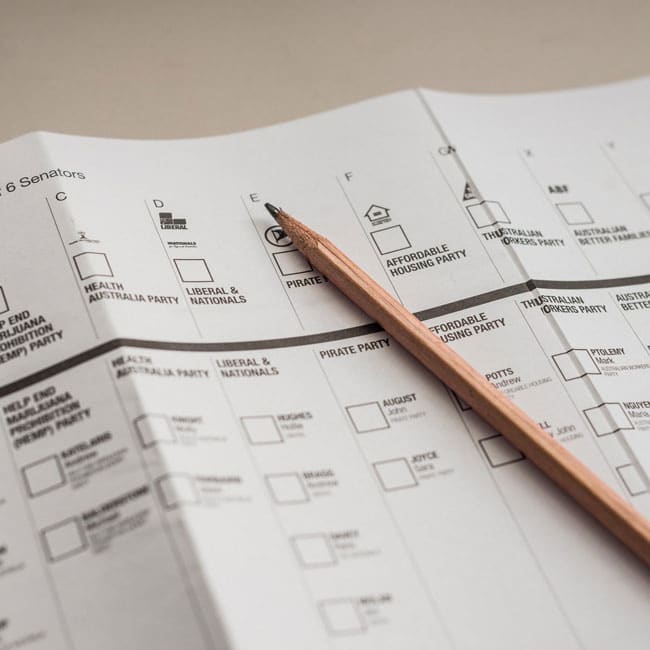

Lies corrupt democracy

One of the most potent threats to democracies is that their elections will be corrupted by lies.

No matter how attenuated in practice, the defining feature of democracies is that the exercise of power is conditional upon the consent of the governed. Consent confers authority. Without consent the exercise of power depends not on democratic legitimacy but instead on the brute force of the autocrat.

For consent to be meaningful, it must be informed. And nothing can be ‘informed’ if it is based on falsehood routinely peddled by those who deal in misinformation and disinformation.

There is nothing new in this. Since antiquity, citizens have always been susceptible to manipulation to skew political outcomes. The difference, today, lies in the speed at which a lie can spread and the breadth of the audience it can reach in an instant. There are also so few individuals or institutions who are trusted to guard and uphold the truth.

Ideally, we might hope that politicians would offer the first line of defence of truth. After all, they have a duty to prioritise the public interest ahead of personal or party interests. Few aspects of the public interest are as important and as obvious as the need to assure the integrity of our democratic elections. Politicians who lie fundamentally undermine the integrity – and therefore the legitimacy – of our elections. In doing so, they betray the public interest.

Despite this, Australia imposes very few penalties on politicians or parties who deliberately lie. This reluctance to punish falsehood is, in part, due to an equal commitment to free speech. We are right to be cautious about introducing measures that restrict free speech for fear of being punished for saying the ‘wrong thing’. It may also be the case that our legislators have a shared interest in not creating a ‘rod’ for their own backs – especially when they can see political advantage in being ‘economical with the truth’.

So, we largely depend on politicians to regulate themselves – with the apolitical Australian Electoral Commission left to manage the worst cases of misinformation and disinformation.

The good news is that politicians are mostly truthful. The bad news is that there are other actors, in the political space, who deliberately seek to manipulate the electorate by manufacturing and propagating misinformation and disinformation. Some of those responsible are state actors who seek to harm countries like Australia by creating or exploiting divisions. They are skilled at using our open information systems as vectors to create states of alarm, confusion and uncertainty – all of which introduces structural weakness and a reduced ability to mount a strong, united response to challenges. Other actors use misinformation and disinformation to advance their ideological or economic interests – by tilting an election in favour of their preferred outcome.

Unfortunately, this kind of interference is now common. Paradoxically, the more it is exposed, the greater the loss of trust in the information presented to us. And that suits the enemies of democracy very well. When a picture or video can be manipulated to the point where you cannot distinguish reality from fiction; when the voice on a phone call is a ‘clone’ based on a thirty second clip – yet is entirely credible; when nothing can be guaranteed to be what it seems to be – how, then, does a voter ever know that they are making an informed decision?

That problem has been solved by financial markets (which also depend on informed decision making) through the profession of auditing. Auditors belong to the profession of accounting. As such, they stand adjacent to the world of the ‘market’ which formally approves the pursuit of self-interest in the satisfaction of the wants of others. The profession of accounting is made up of people who freely choose to abandon the pursuit of self-interest in service of the public interest and a higher ‘good’ – namely the truth.

The role that accountants play in markets is mirrored by the role that journalists are supposed to play in politics – and especially in democracies. Unfortunately, just as some merchants can be relied upon to resort to deception in the pursuit of profits, so can some politicians be relied upon to do the same in the pursuit of victory. Professional journalists are supposed to help protect society from that risk – which is why they are so often lauded as the ‘fourth estate’.

In order to ensure the integrity of our democracy, we need politicians who can be trusted not to lie (even when it advantages them). We need regulators with increased power to identify, curb and punish the activities of those who lie and deceive. We need journalists who place their commitment to the disinterested pursuit of truth ahead of personal or commercial self-interest. We need to be able to distinguish between those who abuse the title ‘journalist’ as false cover and those who genuinely deserve to be trusted. Finally, we need to rally behind and reward media outlets that employ truth-tellers and cease engaging with those who treat the truth as a mere ‘optional extra’.

Fortunately, there are some amongst the political class who are taking steps to encourage truth in politics. A recent initiative, The Ethical Political Advertising Code (EPAC) affords an opportunity for people seeking election to make a public commitment to ‘truth in political advertising’.

Sponsored by Zali Steggall MP, this is a cause that should be apolitical in character – hopefully enjoying the support of any person who cares about the character and quality of our democracy. But this is not just a matter for politicians. It is also something that affects us all.

That is our test as citizens – to choose truth over mere entertainment, to prefer fact to falsehoods that pander to our prejudices.

With so much now at stake in the world, this is a test we must pass. But will we?

BY Simon Longstaff

After studying law in Sydney and teaching in Tasmania, Simon pursued postgraduate studies in philosophy as a Member of Magdalene College, Cambridge. In 1991, Simon commenced his work as the first Executive Director of The Ethics Centre. In 2013, he was made an officer of the Order of Australia (AO) for “distinguished service to the community through the promotion of ethical standards in governance and business, to improving corporate responsibility, and to philosophy.”

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships, Society + Culture

Film Review: If Beale Street Could Talk

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

Why Anzac Day’s soft power is so important to social cohesion

Explainer

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Ethics Explainer: The Harm Principle

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

You’re the Voice: It’s our responsibility to vote wisely

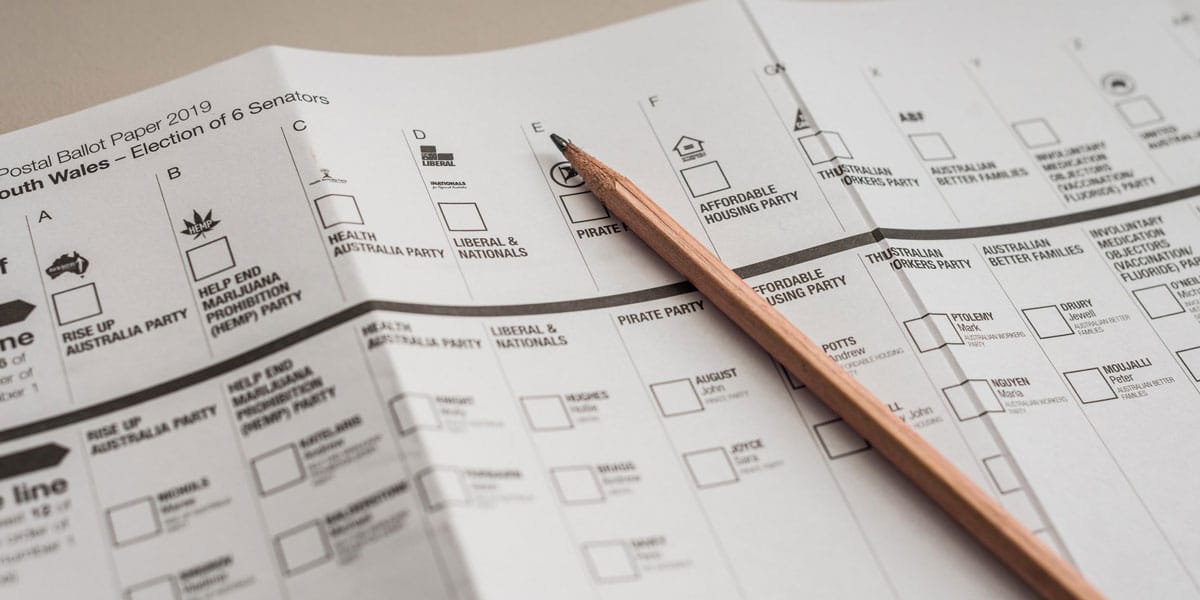

Ask an ethicist: Why should I vote when everyone sucks?

Ask an ethicist: Why should I vote when everyone sucks?

Opinion + AnalysisPolitics + Human Rights

BY Simon Longstaff 10 APR 2025

As time goes on, I’m feeling more disenfranchised by politics. I don’t trust any of the current politicians and it seems they don’t represent issues that are affecting everyday Australians, particularly as the inequality gap is widening. Why should I vote this upcoming election, and does my vote even matter?

The issue of voting in Australian elections is often clouded by the mistaken belief that ‘voting is compulsory’. This really annoys people who feel that it impinges on their liberty as citizens – a liberty that should include the right to decide not to vote. In fact, Australia does not impose ‘compulsory voting’. Instead, there is a policy of ‘compulsory turning up’. What we do when we enter the privacy of the polling booth is entirely up to us. We can cast a valid vote. We can leave the ballot paper unmarked. We can write a screed setting out our views. Basically, we can do whatever we like – just as long as we turn up, collect the voting papers and deposit them in the ballot box.

Some will still object to the need to turn up. It won’t matter to them that the need to do so is one of a very small set of obligations that our country has imposed on all its citizens to maintain a well-functioning democracy.

But let’s just assume that, either willingly or reluctantly, we find ourselves in the polling booth – ballot papers in hand – and have to decide whether or not to cast a valid vote. What should we have in mind as we decide?

First, it’s worth remembering that democratic elections do have the potential to bring about change. If we feel that something is wrong with society, then the vote you cast can, in principle and sometimes in practice, enable reforms for the better. It’s understandable to think that your individual vote might not amount to much. But the arc of history is directed by the aggregated effect of individual votes. Alone, this might not amount to much, but collectively it can change the world. Indeed, the fate of a government can sometimes rest on a foundation as fragile as a single vote in a marginal electorate.

Of course, not all of us live in marginal electorates. In apparently ‘safe’ seats it might seem like your vote will be wasted if you cast it for a candidate who apparently has no chance of beating the likely ‘favourite’. Yet, this thinking runs the risk of becoming self-fulfilling. You never know what might happen if just enough people make the same choice you do – and in doing so bring about an unanticipated victory for a candidate who seemed to have no chance of winning. There are many examples of once ‘safe’ seats being lost by major parties that have held them for generations. Just look at the rise in the number of community independents now sitting in our parliaments. They are only there because a majority of citizens preferred them to others and voted accordingly.

It can also work the other way – where you vote for a candidate who apparently already has enough votes to win. Your vote is not ‘redundant’ because the size of a candidate’s margin of victory can be seen as indicative of community support. A larger margin can lend a representative a greater mandate or more political capital to enact their agenda.

Another problem might be that there is not a single candidate or party that you could support in good conscience. There may not even be a ‘least bad’ (but acceptable) option. In any case, with preferential voting there are no ‘wasted votes’. Every ballot counts towards the eventual result. That is one of the problems with choosing to vote ‘informally’ (returning an unmarked ballot). Doing so will make no positive difference to the outcome. The only ‘upside’ is that you might feel that you avoid complicity in enabling an outcome that you could not support in any case.

Yet, perhaps part of our role as electors is to accept that there will be times when the best we can hope for is the ‘least bad’ result. We may have to reconcile ourselves to the fact that there will be occasions when nothing truly inspiring is on offer. If we’re denied the opportunity to vote for someone who reflects our values and principles – and advances our view of what makes for a good world – we might still see value in using our vote to help block those who would undermine everything we stand and hope for.

This brings us to one of the core reasons for voting. Unlike other political systems where authority is derived from God (theocracies) or wealth (plutocracies) or ‘virtue’ (aristocracies), in democracies the ultimate source of authority comes from those who are ‘the governed’ (the people). We get to decide how decisions are made – through popular control of what is in our Constitution. We also get to choose the representatives who will make laws on our behalf. In the end, we have as much control over the system of government as we choose to exercise.

What limits the exercise of that control is not the system – it is our willingness to become politically active.

If you like living in a democracy – but don’t want to get too involved in shaping the system – then there is a low-cost, potentially high impact way to help shape the way it operates. It is to vote.

Image: Gillian van Niekerk / Alamy Stock Photo

BY Simon Longstaff

After studying law in Sydney and teaching in Tasmania, Simon pursued postgraduate studies in philosophy as a Member of Magdalene College, Cambridge. In 1991, Simon commenced his work as the first Executive Director of The Ethics Centre. In 2013, he was made an officer of the Order of Australia (AO) for “distinguished service to the community through the promotion of ethical standards in governance and business, to improving corporate responsibility, and to philosophy.”

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Big thinker

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Big Thinker: Michel Foucault

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

A note on Anti-Semitism

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

Where do ethics and politics meet?

Explainer

Politics + Human Rights

Ethics Explainer: Anarchy

An angry electorate

I recently attended a gathering of people who engage with a remarkably diverse range of Australians.

Members of this group are directly connected with both the wealthiest and poorest in society. Some are city folk; others firmly grounded in the lives of rural, regional and remote communities. They told of the experience and attitudes of people whose circumstances vary considerably – from the most secure to the most precarious in the land.

Remarkably, when asked about the ‘mood’ of the electorate, all told a similar story. Across all demographics, people are disappointed, frustrated and angry. Some of these feelings understandably arise out of the clear failure of our society to meet even the most basic needs of its members. For example, we were told of a regional city, in New South Wales, where 26% of the community are now experiencing food insecurity. That is, a quarter of the population experiencing days where they do not know if they will be able to secure the food they or their family need. We heard of young people – some from relatively affluent families – who doubt that they will ever be able to afford the ‘Australian Dream’ of a home of their own. For some, if not for all, the word ‘crisis’ is an entirely apt description of what far too many people are experiencing.

However, what this cannot explain is the anger felt by even the most affluent.

The seat of the fire is located in a shared (and growing) sense that too many of our politicians and media are ‘fiddling while Rome burns’. Instead of being wholeheartedly focused on the interests of the community, our leading politicians are perceived as being engaged in the trivial game of political-point-scoring, in pursuit of power for its own sake – rather than as a means for realising a larger vision of what could or should be.

This kind of anger is hard to extinguish. There comes a point when even a good policy is discounted by a public that cynically questions the politicians’ motives. This cynicism is exacerbated by a style of politics that is becoming increasingly partisan. One might reasonably doubt that there was ever a ‘golden age’ of politics in Australia. But the decline in widespread public participation in political parties has meant that a relatively small number of factionalised ideologues can take control of a major party. The way the numbers work, they can push increasingly extreme views – unhindered by the ‘sensible middle’ that used to prevail when major political parties really were ‘broad churches’.

I mention all of this because, as we know all too well in Australia, a single ember can easily give rise to a destructive conflagration.

My sense is that the Australian political landscape is bone dry, with the electoral tinder piling up. In this angry environment, one can foresee a moment of nihilistic abandonment; when the idea of ‘burning it all to the ground’ just might catch on.

This we have seen happen in other parts of the world. If only mainstream America had listened attentively to the complaints of people who genuinely felt abandoned by those occupying ‘the swamp’ in Washington DC. Ignored or labelled ‘deplorables’, President Trump became their ‘agent of destruction’. The same forces were at work in the Brexit referendum. A number of those who voted for leaving the EU doubted that their lives would improve. Instead, they took comfort in the fact that those who looked down on them would be worse off.

Our political elite must accept their fair share of responsibility for the increasing level of anger directed at the ‘system-as-a-whole’. However, as citizens of a democracy, we also have a critical role to play. While we might not be able to control our external environment, we are responsible for our response. Knowing what can happen when anger is let loose at its destructive worse, we need to exercise careful restraint and not enflame the situation.

Australian democracy has many faults. And there are plenty of people who have borne the burden of its failures. But it has also helped to sustain one of the world’s better societies. My hope is that politicians – irrespective of party or political persuasion – might take a moment to look beyond party or personal self-interest to ask if their conduct is strengthening or weakening our democracy in the eyes of the electorate. Democratic institutions are not the property of any government, party or faction. They belong to and are exclusively to be used for the benefit of the people. Those who tarnish or degrade those institutions are guilty of public vandalism. So, let’s hold those who do this individually responsible rather than abandon faith in our entire system of democratic governance. And if it happens to be the case that the problem is the system (as may be the case), then let’s work together to decide what would be better – and then build towards that positive outcome.

In turn, we need to dampen down the fires of anger – not be blinded by the smoke of our righteous indignation – no matter how justified it might be. We need a clear vision of what we think makes for a good society. And then we need to elect those who would help us to build rather than tear down.

BY Simon Longstaff

After studying law in Sydney and teaching in Tasmania, Simon pursued postgraduate studies in philosophy as a Member of Magdalene College, Cambridge. In 1991, Simon commenced his work as the first Executive Director of The Ethics Centre. In 2013, he was made an officer of the Order of Australia (AO) for “distinguished service to the community through the promotion of ethical standards in governance and business, to improving corporate responsibility, and to philosophy.”

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights

Could a virus cure our politics?

Explainer

Society + Culture, Politics + Human Rights

Ethics Explainer: Moral Courage

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights, Society + Culture

Corruption, decency and probity advice

Big thinker

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Big Thinker: Aristotle

If you don’t like politicians appealing to voters’ more base emotions, there is something you can do about it

If you don’t like politicians appealing to voters’ more base emotions, there is something you can do about it

Opinion + AnalysisPolitics + Human Rights

BY Simon Longstaff 5 MAR 2025

The way politicians attempt to garner our votes during an election campaign reveals a great deal about what they think of us as people.

Consider how many politicians try to shore up their standing in the polls by tapping into the emotions of fear and greed. Of the two, playing on personal and communal fear often takes precedence — not least because it is such an easy path to follow. A skilled politician will know how to exploit vulnerability by highlighting what is precarious about our situation and then offer a solution. They will identify an “enemy” who means to cause us harm, and then claim that only they can keep us safe. They will accentuate the differences between “us” and “them” so that they can present themselves as being “on our side”.

The trick is to start with a grain of truth. People are vulnerable. There are some who mean us harm. The community is often divided across boundaries of class, religion, culture, ethnicity and ideology. Next, take that grain of truth and turn it into a mountain that dominates our view of the world. Having ramped up the fear, the skilled politician then offers to come to the rescue — this time eliciting a sense of relief, even gratitude.

An appeal to greed is less dramatic — and often less potent. It is based on the assumption that most people will put self-interest ahead of a concern for others. As Jack Lang, the former Premier of New South Wales, once put it to a young Paul Keating, “Always back the horse named self-interest, son. It’ll be the only one trying.” So, a politician will often promise some kind of personal benefit — usually not to those who might most need what is on offer, but to those whose votes will deliver political victory.

But of course, there is nothing inevitable about politicians appealing to emotions like fear and greed. Such appeals have become part of the political playbook for one simple reason: they work. Campaign strategists are, after all, the ultimate pragmatists, and they would not routinely employ the tactics they do unless they had good reason to believe that they will prove successful.

The message we receive from politicians who resort to such tactics is that they do not believe voters are able to rise above what is base and ignoble.

Which is to say, they do not think of us capable of responding, with equal vigour and commitment, to a style of politics that appeals to something more noble in our character. Indeed, even when the negative tactics work with us, even if we succumb to fear or greed and cast our vote for those who appealed to the lowest common denominator, many of us are left feeling somewhat debased. The persistent question remains: “Is that really all that you think of us? Wasn’t there anything better in us to which you could have appealed?”

That is a very fair and serious question. The core tenet of a democracy is that all power and authority derives from “the people”. But what will be the quality of our democratic polity when the mirror held up to the community by its political leaders presents such a wretched image?

I do not pretend that Australians are an especially virtuous people. We are just as flawed as others — neither more nor less. Which means there are ample opportunities to appeal to what Abraham Lincoln called, in his first inaugural address, “the better angels of our nature”. Why is it not a staple of political discourse to offer a vision of shared prosperity? Why not dwell more on common security based on an account of social cohesion as a positive good, rather than as an antidote to division?

This style of politics — one grounded in hope and inclusion — is much harder work than the politics of deficit and division. But I think the effort is worth making because, at the end of an election cycle, we should be left feeling better about ourselves — both as individuals and as a society. That positive effect should be what every politician seeks to generate. Yes, they want to win, but I would hope it is not “win at any cost”. The ends never justify the means, in the crude sense some people argue to defend the indefensible.

Within a democracy, the outcome of elections ultimately lies in the hands of citizens. We are all equal at the ballot box. We are all able to weigh up the merits of what the candidates for public office put before us. In doing so, I think we should look behind the slogans to consider what underlying message is being conveyed. Do those seeking power hold us in high regard? Do they demonstrate that they recognise the good in us to which they then appeal? Or is their underlying message that they hold us in contempt — diminishing us even as they harvest our vote?

This article was originally published by ABC religion and Ethics.

Image by Jun Li / Alamy Stock Photo

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

When human rights complicate religious freedom and secular law

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

Do states have a right to pre-emptive self-defence?

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

Lessons from Los Angeles: Ethics in a declining democracy

Explainer

Politics + Human Rights

Ethics Explainer: Rights and Responsibilities

BY Simon Longstaff

After studying law in Sydney and teaching in Tasmania, Simon pursued postgraduate studies in philosophy as a Member of Magdalene College, Cambridge. In 1991, Simon commenced his work as the first Executive Director of The Ethics Centre. In 2013, he was made an officer of the Order of Australia (AO) for “distinguished service to the community through the promotion of ethical standards in governance and business, to improving corporate responsibility, and to philosophy.”

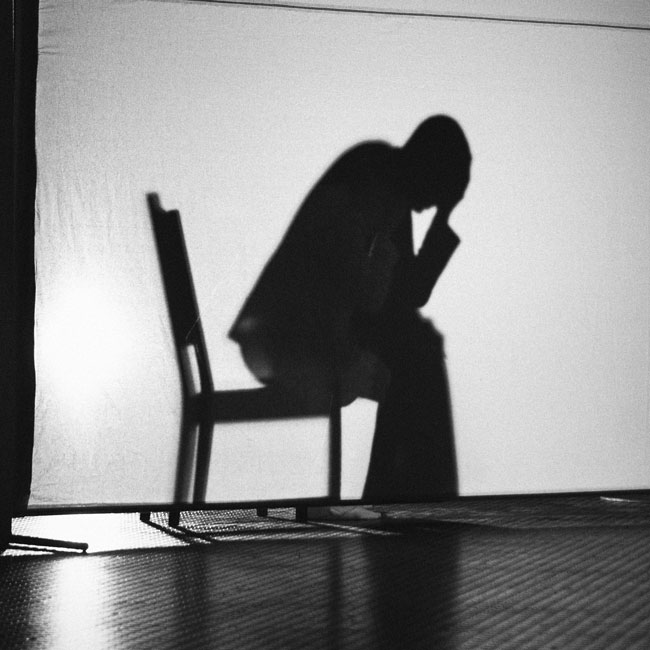

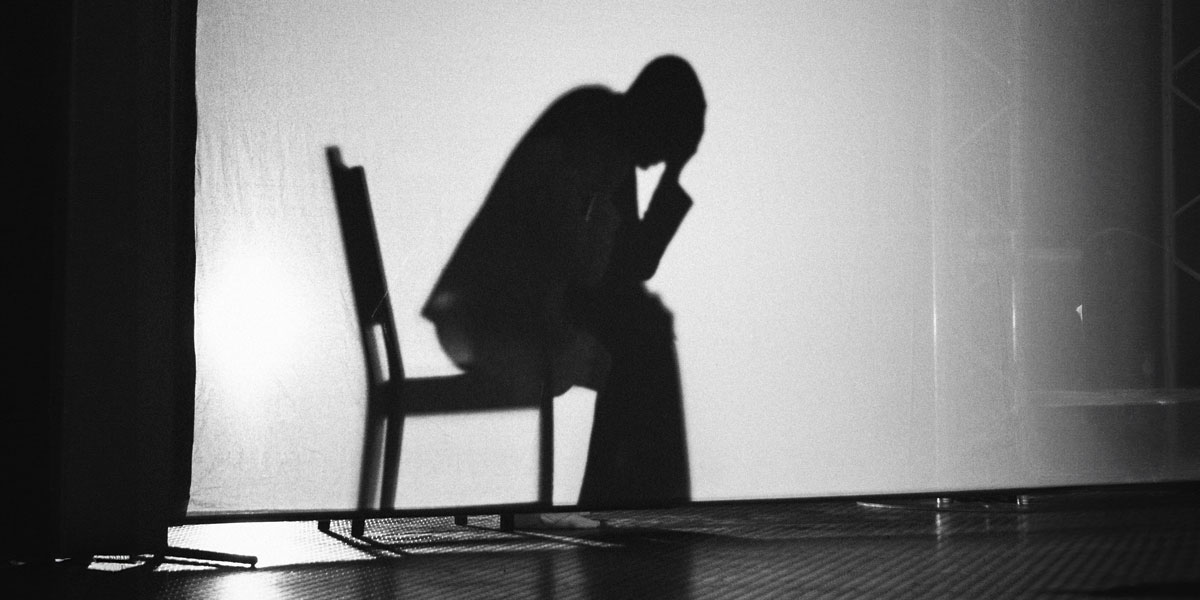

When our possibilities seem to collapse

When our possibilities seem to collapse

Opinion + AnalysisPolitics + Human RightsSociety + Culture

BY Simon Longstaff 24 FEB 2025

In recent years, I have had an increasing number of conversations with people who feel overwhelmed by world events.

They describe the world as wracked by multiple crises of a magnitude such that efforts to reform or repair what is broken is simply futile. This attitude is not confined to those who are poor, oppressed or marginalised. This particular feeling seems to be divorced from personal circumstances – with even the privileged experiencing the same grim outlook.

Especially troubling is the fact that this feeling has been building, despite all of the evidence that Earth has become, on average, a safer, more peaceful place. A decreasing percentage of people live in abject poverty. Infant mortality rates are declining. There are fewer famines and more to eat. As a whole, the ‘four horsemen of the Apocalypse’ have been left playing cards in the stable.

Of course, specific individuals and groups still suffer the full panoply of ills that can afflict the human condition. But, overall, things have been getting better at the same time that people have come to believe that the world is a place of deepening doom and gloom.

One can easily think of an explanation for the divergence between reality and perception. First, is the power of individual stories. A compelling narrative of one person’s suffering can easily be taken as representative of the whole. It’s the same general phenomenon that leads us to feel better whenever we encounter a narrative in which the ‘underdog’ triumphs over the more powerful rival. These figures are swiftly ‘universalised’ to the point that any one of us can see our own possibilities reflected in that of the protagonist. So, when our stories tilt from the positive to the negative we are likely to see our view of the world take on a pessimistic hue.

This brings us to the second reason for this negative outlook. Unfortunately, the media (in all its forms) has ‘discovered’ that ‘bad news’ sells. Or to be more precise, bad news attracts and retains an audience in a way that positive news does not. The implications of this ‘insight’ have been grossly magnified by the emergence of social media – with its insatiable drive for eyes, ears, minds, etc. One of the most depressing stories I have heard, in recent years, is of a publisher that monitors every second of a story’s online life. The moment interest begins to flag, I am reliably advised, the instruction is to ‘bait the hook’ with something that implies ‘crisis’. So, what might properly be considered ‘troubling’ is elevated to the point where it feels like an existential threat posing a risk to all. Few remember the details when (almost inevitably) the more mundane truth emerges. What remains is the feeling – and facts rarely disturb established feelings.

These factors (and a host of others – too numerous to mention here) have combined to help generate a creeping sense that one might as well disengage and let the world go to hell in the proverbial ‘handbasket’. Let’s not bring children into a failing world. Let’s limit our attention to things within our span of control (not much). Let’s not vote – it’s pointless …

The deeply disturbing thing about all of this is that the temptation to withdraw because of the perceived futility of engagement gives rise to a self-fulfilling prophecy grounded in that great enemy of democracy; despair.

The truth of democracy (and markets for that matter) is that even the least powerful individual can change the world when working with others. Remarkably, we don’t even have to plan and coordinate for collective action to have a powerful effect. Indeed, one need not be ‘heroic’ (in the ‘Nelson Mandela’ sense) to be an author of momentous events. It’s just that you are unlikely ever to know when your decision or action tilted the world on its axis. Often it just requires a person to fall just a smidgen on the right side of a question. And when enough people do the same, there is progress.

Despair is the absence of hope that this is possible. It is a deceit that makes us fail – not because we never could succeed but because it destroys our belief in the possibility that we can be effective agents for change.

If we succumb to despair, then our possibilities collapse – not because we are powerless but because we believe ourselves to be.

Australia should aspire to be one of the world’s great democracies. It’s in our bones – dating back to South Australia that, in the late nineteenth century, brought into the world the first modern democracy in which all adults could not only vote but take up public office – irrespective of sex, gender, race or creed. For years, the secret ballot was known as the “Australian Ballot’. In 1900, Australia held more patents per head of population than any other country in the world. Yes, there were all the problems of colonisation, racism, sexism and a plethora of wrongs. And yes, we went backward for a while after Federation. But that reality did not give rise to despair.

Things actually can get better. Democracy is the vehicle for doing so; not because it demands so much of us as individuals – but because it demands so little. We just need to allow ourselves a small measure of hope to defeat despair. We need to take just a small, individual step forwards. Do this together, and nothing can stop us.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Big thinker

Politics + Human Rights

Big Thinker: Michael Sandel

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

The Constitution is incomplete. So let’s finish the job

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture, Politics + Human Rights

Freedom of expression, the art of…

Explainer

Politics + Human Rights

Ethics Explainer: Just War Theory

BY Simon Longstaff

After studying law in Sydney and teaching in Tasmania, Simon pursued postgraduate studies in philosophy as a Member of Magdalene College, Cambridge. In 1991, Simon commenced his work as the first Executive Director of The Ethics Centre. In 2013, he was made an officer of the Order of Australia (AO) for “distinguished service to the community through the promotion of ethical standards in governance and business, to improving corporate responsibility, and to philosophy.”

Let’s cure the cause of society’s ills, and not just treat the symptoms

Let’s cure the cause of society’s ills, and not just treat the symptoms

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + Leadership

BY Simon Longstaff 25 JUN 2024

The lead up to June 30th, is critically important for organisations, like The Ethics Centre, that depend on tax-deductible donations in order to make ends meet. Every organisation has a compelling claim to make for why their cause is deserving of support.

Some have ‘natural constituencies’ defined by the specific nature of the issue to be addressed. For example, medical research institutes will focus on those touched by the various diseases they work to treat and to cure. Other charities have a clear focus on solving one clearly defined problem, like homelessness, and can point to the specific impact that every dollar of charitable giving can have.

And then there are organisations like The Ethics Centre – where the work ranges across the whole span of human affairs with an impact that may take decades, if ever, to register. Consider this … How do you capture the significance of the countless bad things that did not happen as a direct result of good ethics leading to good decision making?

Yet, ours is a story that needs to be told – again and again. It’s not just a matter of ‘rattling the tin’ in the hope of securing a few more donations. Please believe me when I say we need them – as never before. However, there is also real and growing sense in which the need for ‘ethics’ is growing greater with each passing day.

Poverty, inequality and disadvantage are not ‘natural’ aspects of the human condition. Nor is it inevitable that the earth should be ravaged by our species. Rather, the root cause of social and environmental degradation lies in the character and quality of human choice – the most powerful force on this planet. Knowing this to be so, philosophers have spent millennia working to understand the underlying structure of human choice and how it might be harnessed for good rather than ill. Ethics is the branch of practical philosophy that addresses this question.

Australia stands on the cusp of a brilliant future. It has everything any society could need: vast natural resources, abundant clean energy and an unrivalled repository of wisdom held in trust by the world’s oldest continuous culture supplemented by a richly diverse people drawn from every corner of the planet.

As such, Australia could become the most prosperous and just society the world has ever known. However, whether or not this future can be grasped depends not on our natural resources, our financial capital or our technical nous. The ultimate determinant lies in the public’s willingness to trust those who will lead the process of translating the vision into reality.

Thus, we see the effects of ethical failure not only in its most obvious symptoms. Its corrosive effects can also be seen in the loss of public trust in nearly all of our major public and private institutions. This loss of trust has come at precisely the time when it is most needed – when we should be able to rely on those institutions to help guide society as it navigates a landscape of increasing complexity.

Australia lacks a peak organisation with a mandate to address the major ethical questions of our age. Significant legal questions can be referred to the Australian Law Reform Commission. The Productivity Commission performs a similar function in relation to questions of economic significance. No such body exists to consider ethical questions – such as are encountered on a daily basis. For example: should we deploy lethal autonomous weapons systems? What are the implications of embracing modern manufacturing techniques that will make many existing jobs redundant? Should we be moving to tax consumption and/or the means of production rather than labour so as to preserve the capacity to offer a social ‘safety net’? Is access to a ‘home’ (as opposed to ‘shelter’) a basic human right? And so on …

The Ethics Centre has spent 35 years building the foundations upon which to build a world-first, national Ethics Institute. But, as of today, that still remains a dream. Meanwhile, we have the work of the moment. It includes offering our Ethi-call service, the world’s only free national helpline for people with ethical issues. Its greatest impact is when it helps to prevent the kind of ‘moral injury’ that does so much harm to mental health. And then there are events like the Festival of Dangerous Ideas (FODI) one of the few places left where reasonable people can gather together and engage in the civilising art of ‘principled disagreement’. These are just some of the things we do in order to help bring ethics to the centre of everyday life.

I come back to one central point. If you’d like to address causes over symptoms then please consider supporting ethics. It’s simple: better ethics make for a better world. Even a few dollars can help that to be as true in reality as it is in principle.

With your support, The Ethics Centre can continue to be the leading, independent advocate for bringing ethics to the centre of everyday life in Australia. Click here to make a tax deductible donation today.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

6 Myths about diversity for employers to watch

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Why we need land tax, explained by Monopoly

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships

Corporate whistleblowing: Balancing moral courage with moral responsibility

LISTEN

Health + Wellbeing, Business + Leadership, Society + Culture

Life and Shares

BY Simon Longstaff

After studying law in Sydney and teaching in Tasmania, Simon pursued postgraduate studies in philosophy as a Member of Magdalene College, Cambridge. In 1991, Simon commenced his work as the first Executive Director of The Ethics Centre. In 2013, he was made an officer of the Order of Australia (AO) for “distinguished service to the community through the promotion of ethical standards in governance and business, to improving corporate responsibility, and to philosophy.”

Why Anzac Day’s soft power is so important to social cohesion

Why Anzac Day’s soft power is so important to social cohesion

Opinion + AnalysisPolitics + Human Rights

BY Simon Longstaff 25 APR 2024

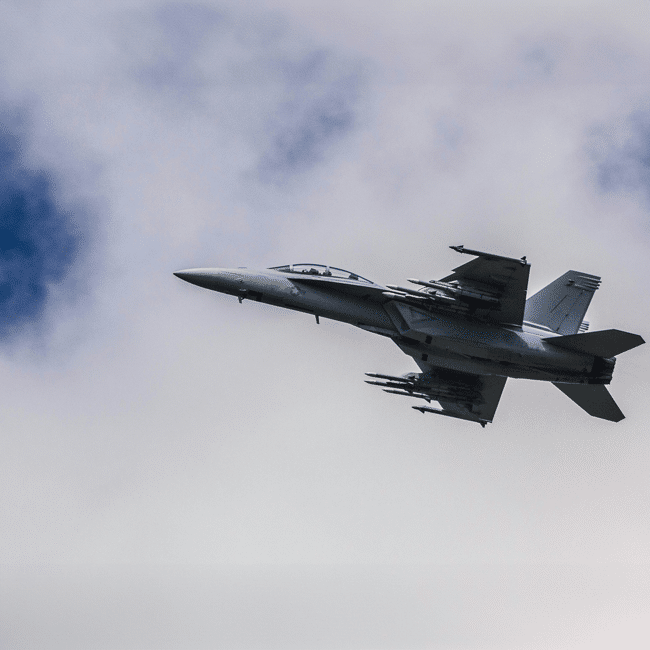

Any country wishing to advance or defend its strategic interests has recourse to two types of power: hard and soft.

Richard Marles’ release of the government’s most recent Defence Strategic Review, coming as it does just before Anzac Day, provides an opportunity to examine how well Australia is positioned in relation to the oft-neglected “defensive” aspect of soft power.

Any potential adversary knows that a low-risk way to wound a diverse, multicultural society is to pick it apart until it turns against itself. They are right. Look at the cracks that have opened up at home under the strain of a distant war between the state of Israel and Hamas. It has led to a massive rise in antisemitism and a resurgence in Islamophobia.

Indeed, the first thought of many was that the murderous rampage at Bondi Junction was a terrorist attack connected to conflict in the Middle East. Two days later, a surge of communal violence was unleashed in response to the wounding of two clerics in a terrorist incident.

Thanks to good management by police, politicians and community leaders, our worst fears were not realised. However, we should be warned. Malicious actors will have been encouraged by evidence of how easy it would be to ignite the tinder of a larger conflagration. They will be readying themselves to stoke the embers with their weapons of choice: misinformation and disinformation. How can we defend against this?

There are two aspects of soft power in its defensive form that we must deploy now to build resilience for the future. First, we must work to restore trust in our private and public institutions. Second, we need to harness the power of unifying narratives.

The first of these tasks is essential if we are to protect ourselves against the corrosive effects of misinformation and disinformation. Our current approach mostly relies on regulation and surveillance to control the worst of it.

However, a liberal democracy with a commitment to free speech will always fight with the equivalent of one hand tied behind its back. So, we need to work twice as hard; investing in the development of individuals and institutions who can be trusted to offer sound guidance at times when it really matters.

Trustworthiness needs constant effort

When natural disasters strike, we all tend to look to the ABC for critical information – even those who are concerned about the national broadcaster and its editorial stance. Trust in our public institutions should not be the exception. It needs to become the norm. This will happen only if those institutions are consistently trustworthy.

Becoming trustworthy is an acquired skill. It needs constant effort. Trustworthiness is not something that can be produced by anti-corruption commissions, by regulation or surveillance. It requires investment in a positive commitment to ethics.

As a public, we need to know that our leaders merit our trust at times when it really matters. No matter what those dedicated to sowing the seeds of dissension might tell us, no matter what conspiracy theories might be abroad, we need good reason to believe that when it comes to the crunch, our leaders have the knowledge, skills and character to be relied on. In short, we need to invest in the nation’s “ethical infrastructure”.

Second, we need to make far more of our “secular myths”. Like all such stories, their power resides in something larger than the immediate facts. They speak to something deeper – which brings me to Anzac Day. Many nations ground their identity in stories of triumph, whether it be the defeat of an armed foe or the overthrow of an illegitimate or oppressive regime. Anzac Day offers something different.

Those of us who celebrate Anzac Day not only remember the fallen. We also find meaning in a striking example of “noble failure”.

To try your best. To venture all, even if you fail. To maintain honour, even to the end. These are ideals to which anyone can aspire – even if, in reality, we so often fall short.

This ideal is not bound by religion, culture, language or heritage. About 70 First Nations people fought at Gallipoli. The Turks, who won the engagement, still honour what took place – despite the horrors of war. People of all faiths and none have found moments of inspiration in a story that does not glorify war – only the spirit of those “warriors” who try to be and to do their best, even when they fail.

Of course, this is just one narrative. How many others are out there waiting to be deployed for the common good?

We spend billions of dollars on the implements of hard power. But on Anzac Day we should remember its complement – the soft power of a shared ethos that underpins a cohesive society and safety at home.

This article was originally published in The Australian Financial Review.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

To Russia, without love: Are sanctions ethical?

Big thinker

Politics + Human Rights

Big Thinker: Kimberlé Crenshaw

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Climate + Environment

What we owe each other: Intergenerational and intertemporal justice

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

There’s more than lives at stake in managing this pandemic

BY Simon Longstaff

After studying law in Sydney and teaching in Tasmania, Simon pursued postgraduate studies in philosophy as a Member of Magdalene College, Cambridge. In 1991, Simon commenced his work as the first Executive Director of The Ethics Centre. In 2013, he was made an officer of the Order of Australia (AO) for “distinguished service to the community through the promotion of ethical standards in governance and business, to improving corporate responsibility, and to philosophy.”

Access to ethical advice is crucial

Access to ethical advice is crucial

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + LeadershipSociety + Culture

BY Simon Longstaff Major General Paul Symon Dr Miah Hammond-Errey 19 MAR 2024

Better ethical approaches for individuals, businesses and organisations doesn’t just make moral sense. The financial benefits are massive, too.

It might seem a little ironic to take ethics advice from an intelligence agency that consciously deploys deception, yet it shows why access to ethical advice is vitally important. Indeed, we argue that the example of an ethics counsellor within ASIS demonstrates why every organisation should have (access to) an ethical adviser.

Ethics is often considered to be a personal or private activity, in which an individual makes decisions guided by an ethical code, compass or frame of reference. However, emerging technologies necessitate consideration of how ethics apply “at scale”.

Whether we are conscious of this (or not), ethical decisions are being made at the “back end” – or programming phase – but may not be visible until an outcome or decision, or user action, is reached at the other end of the process.

Miah Hammond-Errey describes in her book, Big Data, Emerging Technologies and Intelligence: National Security Disrupted, how “ethics at scale” is being driven by algorithms that seek to replicate human decision-making processes.

This includes unavoidable ethical dimensions, at increasing levels of speed, scope and depth – often in real time.

The concept of ethics at scale means that the context and culture of the companies and countries that created each algorithm, and the data they were trained on, increasingly shapes decisions at an individual, organisation and nation-state level.

Emerging technologies are likely to be integrated into work practices in response to the world itself becoming more complex. Yet, those same technologies may themselves make the ethical landscape even more complex and uncertain.

The three co-authors recently discussed the nexus of ethics, technology and intelligence, concluding there are three essential elements that must be acknowledged.

First, ethics matter. They are not an optional extra. They are not something to be “bolted on” to existing decision-making processes. Ethics matter: for our own personal sense of peace, to maximise the utility of new technologies, for social cohesion and its contribution to national security and as an expression of the values and principles we seek to uphold as a liberal democracy.

Second, there is a strong economic case for investing in the ethical infrastructure that underpins trust in and the legitimacy of our public and private national intuitions. A 10 per cent improvement in ethics in Australia is estimated to lead to an increase in the nation’s GDP of $45 billion per annum. This research also shows improving the ethical reputation of a business can lead to a 7 per cent increase in return on investment. A 10 per cent improvement in ethical behaviour is linked with a 2.7 to 6.6 per cent increase in wages.

Third, ethical challenges are only going to increase in depth, frequency and complexity as we integrate emerging technologies into our existing social, business and government structures. Examples of areas already presenting ethical risk include: using AI to summarise submissions to government, using algorithms to vary pricing for access to services for different customer segments or perhaps using new technologies to identify indicators of terrorist activity. That’s before we even get to novel applications employing neurotechnology such as brain computer interfaces.

Ethical challenges are, of course, not new. Current examples driven by new and emerging technologies include privacy intrusion, data access, ownership and use, increasing inequality and the impact of cyber physical systems.

However, an extant need for ethical rumination is, for now at least, a human endeavour.

As a senior leader of ASIS, with a background in the military, Major General Paul Symon (retd) strongly supported resourcing a (part-time) ethics counsellor. He was aware the act of cultivating agents, and the tradecraft involved, would inevitably demand moral enquiry by the most accomplished ASIS officers.

His belief was without a solid understanding of ethics, there was no standard against which the actions of the profession, or the choices of individuals, could be measured.

So, a relationship emerged with the Ethics Centre. A compact of sorts. Any officer facing an ethical dilemma was encouraged to speak confidentially to the ethics counsellor. The conversation and the moral reasoning were important.

General Symon guaranteed no career detriment to anyone who “opted out” of an activity so long as they had fleshed out their concerns with the ethics counsellor. Often, an officer’s concerns were allayed following discussion, and they proceeded with an activity knowing there was a justification both legally and ethically.

Perhaps if we’d had ethical advisers available across other institutions, we might have prevented some of the greatest moral failures of recent times, such as the pink batts deaths and robodebt.

If we had ethical advisers accessible to industry, then perhaps we’d have avoided the kind of misconduct revealed in multiple royal commissions looking into everything from banking and finance to the treatment of veterans to aged care.

We believe our work over years, including examples in defence and intelligence, demonstrates practical examples and the requirement to build our national capacity for ethical decision-making supported by sound, disinterested advice. That is one reason we support the establishment of an Australian Institute for Applied Ethics with the independence and reach needed to work with others in lifting our national capacity in this area.

Pledge your support for an Australian Institute of Applied Ethics. Sign your name at: https://ethicsinstitute.au/

This article was originally published in The Canberra Times.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

‘Hear no evil’ – how typical corporate communication leaves out the ethics

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

Meet Dr Tim Dean, our new Senior Philosopher

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Society + Culture

The right to connect

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Pulling the plug: an ethical decision for businesses as well as hospitals

BY Simon Longstaff

After studying law in Sydney and teaching in Tasmania, Simon pursued postgraduate studies in philosophy as a Member of Magdalene College, Cambridge. In 1991, Simon commenced his work as the first Executive Director of The Ethics Centre. In 2013, he was made an officer of the Order of Australia (AO) for “distinguished service to the community through the promotion of ethical standards in governance and business, to improving corporate responsibility, and to philosophy.”

BY Major General Paul Symon

Major General Paul Symon (retd) is a former director-general of the Australian Secret Intelligence Service.

The Ethics Institute: Helping Australia realise its full potential

The Ethics Institute: Helping Australia realise its full potential

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + LeadershipSociety + Culture

BY Simon Longstaff 11 MAR 2024

It has been some three years since we posed a simple question: to what extent (if any) does ethics affect the economy?

The team we asked to answer that question was led by the economist, John O’Mahony of Deloitte Access Economics. After a year spent analysing the data, the answer was in. The quality of a nation’s ethical infrastructure has a massive impact on the economy. For Australia, a mere 10% improvement in ethics – across the nation – would produce an uplift on GDP of $45 billion per annum. Yes, that’s right, a decade later the accrued benefit would be $450 billion – and growing!

Some things are too good to be true. This is not one of them.

The massive economic impact is a product of a very simple formula: increased ethics=increased trust=lower costs and higher productivity. Increasing trust is the key. Not least because without it, every case for reform will either fall short or fail … no matter how compelling. Ordinary Australians going about their lives simply will not allow reform when they believe that the benefits and especially the burdens of change will be unfairly distributed. So it is that the incredible potential of our nation is held hostage to factors that are entirely within our control.

We invest billions in physical and technical infrastructure in the hope that it will lead to improvement in our lives. We invest almost nothing in the one form of infrastructure that determines how well these other investments will perform. That is, we invest precious little in our ethical infrastructure.

My first reaction to receiving the Deloitte Access Economics report was to try to engage with the Federal Government of the day. I thought that whatever one might think about ‘ethics’ as a concept, there could be no ignoring the economics. I was wrong. The message came back that the government was “positively not interested” in discussing the findings or their implications. I have met with rejection and (more often) indifference on many occasions over the past thirty years. This ranks at the top of my list of negative responses.

The Ethics Centre has always been resolutely apolitical. So, we cast around to find someone in the then Federal Opposition who might engage with the findings. And that is where the current Treasurer, Dr Jim Chalmers, comes in. He took the findings very seriously – so much so that he issued a further challenge to identify what specific measures would increase ethics by 10% and thus, produce the estimated economic uplift. That led to a second piece of work by Deloitte Access Economics – and nine months later, we received the second report. It is that report that has brought forth the current proposal to establish the world-first Australian Institute for Applied Ethics.

The proposed Institute will have two core functions: first, it will be a source of independent advice. Legal issues are referred to the Australian Law Reform Commission. Economic issues are sent to the Productivity Commission. As things stand, there is nowhere to refer the major ethical issues of our times. Second, the Institute will work with existing initiatives and institutions to improve the quality of decision making in all sectors of life and work in Australia. It is important to note here that the Institute will neither replace or displace what is already working well. The task will be to ‘amplify’ existing efforts. And where there is a gap, the Institute will stimulate the development of missing or broken ethical infrastructure.

Above all, such an Institute needs to be independent. That is why we are seeking to replicate the funding model that led to the establishment of the Grattan Institute – by establishing a capital base with a mixture of funds from the private sector and a one-off grant of $33.3 million from the Federal Government.

The economic case for making such an investment is undeniable. The research shows that better ethics will support higher wages and improved performance for companies. Better ethics also helps to alleviate cost of living pressures by challenging predatory pricing practices – and other conduct that is not controlled in a market dominated by oligopolies and consumers who find it hard to ‘shop around’.

But what most excites The Ethics Centre, and our founding partners at the University of NSW and the University of Sydney, is the chance for Australia to realise its potential to become one of the most just and prosperous democracies that the world has ever known. With our natural resources, vast reserves of clean energy and remarkable, diverse population – we have everything to gain … and nothing to lose by aspiring to be just a little bit better tomorrow than we have been today.

And that is why something truly remarkable has happened. ACOSS, the ACTU, BCA and AICD have all come together in a rare moment of accord. Support is growing across the Federal Parliament. Australians from all walks of life – are adding their names in support of an idea whose time has come.

All we need now is our national government to make an investment in a better Australia.

Pledge your support for an Australian Institute of Applied Ethics. Sign your name at: https://ethicsinstitute.au/

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

FODI launches free interactive digital series

Big thinker

Relationships, Society + Culture

9 LGBTQIA+ big thinkers you should know about

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships

The future does not just happen. It is made. And we are its authors.

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership