Sell out, burn out. Decisions that won’t let you sleep at night

Sell out, burn out. Decisions that won’t let you sleep at night

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + Leadership

BY Fiona Smith The Ethics Centre 1 JAN 2018

Nick Naylor is a man who is comfortable being despised. In the movie Thank You for Smoking, he is the spokesman for the tobacco lobby and happily admits he fronts an organisation responsible for the deaths of 1,200 people every day.

While he excuses his employment as a lobbyist by unconvincingly adopting the “Yuppie Nuremberg defence” of having to pay a mortgage, the audience learns that his real motivation is that he loves to win.

The bigger the odds, the better.

Naylor is not the sort of man who would struggle with ethical distress or moral injury from the work he chooses to do. This work “requires a moral flexibility that is beyond most people”, he says.

He likens his role to that of a lawyer, who has to defend clients whether they are guilty or not.

Partner of law firm Maurice Blackburn, Josh Bornstein, says the convention in law that everyone deserves legal representation can certainly assist lawyers called upon to defend people whose actions they find morally reprehensible – however that argument does not work for everyone.

‘If I don’t, someone else will’

Bornstein says there is no way of knowing how many lawyers refuse to work on cases because of moral conflict, but it happens from time to time. “Not every week or every month”, he adds.

“Do [lawyers] have moral crises? Some people have a strong sense of morality and others try and sweep that to one side and consider that, as professional lawyers, they shouldn’t dwell on moral concerns”, says Bornstein, who specialises in workplace law.

Bornstein is well known for his advocacy for victims of bullying and harassment, however, he has also acted for people accused of those things.

“I’ve found myself, from time to time, acting in matters that have been very morally confronting”, he says.

As a young lawyer, when he was expressing his disapproval of the actions of a client, his mentor told him to stop moralising and indulging himself.

“He said that when people like that get into that trouble, that is the time they need your assistance more than any other. Your job is to help them, even when they have done the wrong thing”, says Bornstein.

Bornstein says ethical distress can occur in all sorts of professions. “I would think the same would occur for a psychologist, social worker, doctors, and maybe even priests.

“Consider the position if you were lawyers for the Catholic Church over the last three decades, dealing with horrific, ongoing cases of child sexual abuse.”

Distress or injury? Making a distinction

The CEO of Relationships Australia NSW, Elisabeth Shaw, says when seeking to understand the psychological damage wrought by such conflicts, a distinction should be made between ethical (or moral) distress and moral injury.

Ethical or moral distress occurs when someone knows the right thing to do, but institutional constraints make it nearly impossible to pursue the right course of action.

This definition is often used in nursing, where staff are conflicted between doing what they feel is right for the patient and what hospital protocol and the law allows them to do. They may, for instance, be required to resuscitate a terminally ill patient who had expressed a desire to end the pain and die in peace.

Moral injury is a more severe form of distress and tends to be used in the context of war, describing “the lasting psychological, biological, spiritual, behavioural, and social impact of perpetrating, failing to prevent, or bearing witness to acts that transgress deeply held moral beliefs and expectations”.

The St John of God Chair of Trauma and Mental Health at the University of New South Wales, Zachary Steel, says most moral injuries stem from “catastrophic traumatic encounters”, such as military and first responder types of duties and responsibilities.

He says he sees moral injury as a variant of post-traumatic stress disorder and distinguishable from the kind of moral harm wrought by bullying and highly dysfunctional workplaces.

Tainted by your compliance

This distinction does not diminish the distress experienced by those who are torn between what they are expected to do, and what they know they should do.

Shaw, who has volunteered at The Ethics Centre’s Ethi-call hotline for eight years as team supervisor, says the service handles around 1,500 calls per year and a typical request for advice may come from an accountant who is pressured to sign off on dodgy records.

“After [complying], you may feel a lesser version of yourself. You may feel you didn’t have a choice, but also feel quite tainted by those actions”, she says.

“Even if you went to great lengths to do all the things that could be seen to be correct, you can still feel very injured at the end of it.”

For some people, it is the nature of the organisation they work for, or its culture, that creates a problem.

“Some people feel like they are part of an organisation that is, perhaps, habitually part of shabby behaviour”, says Shaw.

Someone working for a tobacco company (like the fictional Nick Naylor) may start by shrugging off concerns, reasoning that they need the job and if they don’t do it, someone else will. However, over time, embarrassment grows and they become more aware of the disapproval of others and they start to feel morally compromised, says Shaw.

“And then there is a point where it feels like [your job] has injured your sense of self … or even your professional identity and, in fact, might make you feel less than yourself.”

There are also professions where people sign up for noble reasons, in a not-for-profit, for instance, but then find unjustifiable things are happening.

“You start to feel like there is a huge dissonance – that can no longer be resolved – between what you say you are doing and what you are actually caught up in.”

Can’t tell right from wrong

Burnout and mental health conditions such as anxiety and depression can result from this stress and some people become so ethically compromised they lose their moral compass and no longer can tell right from wrong, she says.

Moral distress is one of a range of factors contributing to the poor record of the law profession when it comes to the incidence of mental health issues, says Bornstein.

A third of solicitors and a fifth of barristers are understood to suffer disability and distress due to depression.

Some of the more “sophisticated” firms encourage their people to seek assistance and offer employee assistance programs, such as hotlines.

Maurice Blackburn has a “vicarious trauma program” for lawyers who may, for instance, work with people dying from asbestosis or medical mishaps or accidents.

“Even in my area of employment [workplace law], vicarious trauma is a real risk and problem”, he says.

“So, we have tried to change our culture to be very open about it, speak about it, to regularly review it, to work with psychologists, to have a program to deal with it, to know what to do if a client threatens suicide or self-harm. But it is an ongoing challenge.”

Bornstein has, himself, sought guidance from the Law Institute on ethical dilemmas.

“The other underestimated, fantastic outlet is to confer with colleagues you respect who are, hopefully, one step or more removed from the situation and can give wise counsel. Another is to seek similar support from barristers, I’ve done that too, and then there is friends and family.”

Bornstein says even though he is not aware of any law firm offering a “moral repugnance policy” that would allow people to avoid working on cases that could cause ethical distress, he is aware there would be little benefit in forcing a lawyer to take one.

“It may be resolved by [getting] someone else working on the case.”

The value of a strong ethical framework

Social work is another area that is fraught with ethical dilemmas and, like lawyers, social workers often see people at their worst.

However, the profession has a developed an ethical framework and support system that ensures workers are not left alone to tackle difficult dilemmas, says Professor Donna McAuliffe, who has spent the past 20 years teaching and researching in the area of social work and professional ethics.

“The decisions that social workers have to make can be very complex and distressing if they are not made well”, says McAuliffe, who is Deputy Head of School at the School of Human Services and Social Work at Griffith University.

Social workers have a responsibility, under their code of ethics, to engage professional supervision provided by their employer.

Because social work in Australia is a self-regulated profession, it is important to have a very robust and detailed code of ethics to give guidance around practise, she says.

“We educate social workers to not go alone with things, that consultation and support of colleagues are going to be the best buffers against burn out and distress and falling apart in the workplace – and there is evidence to show good collegial, supportive relationships at work is the thing that buffers against burnout in the best way.”

McAuliffe says employers in business may think about building into their ethical decision making frameworks some consideration of the emotions, worldview, and cultures of the people affected by difficult workplace choices.

“The decision may still be the same … but the [employee] will feel a hell of a lot better about it if they know they have thought about how the person at the end of that decision can be supported.”

Shaw cautions that people should try and seek other perspectives before making decisions about situations that make them feel morally uncomfortable.

“Part of the process of ethical reflection is to work out, ‘Do I have a point?’

“Because we are all developed in different ways ethically, just because you have a reaction and you are worried about something and you feel ethically compromised doesn’t make you correct.

“What it means is that your own moral code feels compromised. The first thing to do is spend some time working out, is my point valid? Do I have all the facts?

“What do I do about the fact that my colleagues and bosses don’t feel bothered? Should I look at their point of view?

“Sometimes, when you feel like that, it really is a trigger for ethical reflection. Then, on the basis of your ethical reflection, you might say, ‘You know what? Now that I have looked at it from many angles, I think, perhaps I was over-jumpy there and I think if I take these three steps, I could probably iron this out, or if I spoke up, change might happen.’

“And then the whole thing can move on.

“Having a reaction to what feels like an ethical trigger is really just the beginning of a process of self-understanding and the understanding in context.”

This article was originally written for The Ethics Alliance. Find out more about this corporate membership program. Already a member? Log in to the membership portal for more content and tools here.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships

Workplace romances, dead or just hidden from view?

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Day trading is (nearly) always gambling

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Accepting sponsorship without selling your soul

WATCH

Business + Leadership, Climate + Environment, Science + Technology

How to build good technology

BY Fiona Smith

Fiona Smith is a freelance journalist who writes about people, workplaces and social equity. Follow her on Twitter @fionaatwork

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

The pivot: ‘I think I’ve been offered a bribe’

The pivot: ‘I think I’ve been offered a bribe’

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + Leadership

BY Steven York The Ethics Centre 1 JAN 2018

The man waiting for me in the meeting room was an unexpected visitor. He introduced himself as the head of a government department and welcomed me to the Czech Republic. He had brought a “friend”.

“You are going to have meet your budget, but I can give you all the government work you need”, he said with a meaningful look. “I just want you to employ this girl.”

He pointed to the young woman who sat opposite. She was beautiful, breathtakingly so, and I suspected she was to be a “spy” for the government. Working on behalf of British and US lenders, I was leading a team investigating cases of fraud that often wound their way back to organised crime and government figures.

I was just a few months into my posting to Eastern Europe and I knew to be wary. This is a country where surveys show two thirds of Czech citizens (66%) believe that most, or almost all, public officials are corrupt.

I left the room, grabbed the arm of my direct report and said, “I think I have just been offered a bribe”.

My first strategy was to make the problem go away by making it clear that everything was to be “above board”.

I walked back into the meeting room. “Leave it with me”, I said. “Look, it sounds interesting, send me her CV and we will see where she may fit in the organisation.”

I had made no commitment, but had asked him to “make it official”. But that was not the end of it. No CV arrived, but three weeks later he was back, unsmiling this time.

“If you don’t employ her, you won’t get any government work at all”, he threatened. I thanked him, said I understood what he was talking about and asked him once more to send the CV. He left without shaking my hand.

A senior leader within the organisation I worked for pulled me up the following day to berate me for being so stupid. Bribes and corruption are a ubiquitous part of the business environment in some countries.

While the organisation might have seen a brown paper bag full of cash as corruption, “scratching each other’s back” in this way was regarded as mere facilitation.

It came to me right then, that this was a real turning point.

With 20 years in the NSW Police behind me, I thought I was a bit of a tough guy, but I knew my life was about to change if I did not change my mind about hiring the “spy”. This could be a dangerous situation because of the kind of people involved in corruption.

It became clear that I had become a problem to the people running the Prague office. At every executive meeting, the others would roll their eyes when I spoke. Their attitude was that we had to get the business, no matter what. Eventually I had to leave before my contract was up.

Looking back through the intervening years, are there things I would have done differently? Perhaps I should have tried being upfront with the CEO – however, he was new to the job and was part of the “giggle”.

I thought at the time that it was better to leave the matter “intangible”, to not start a fight when I was the only Australian in the office.

I had let them know where I stood – a strategy that worked well in the Police Force where, if you were known as a straight shooter, people wouldn’t approach you with corrupt offers.

I could have done more research to find out what was the normal way of conducting business there. I knew there was a lot of corruption in the country, but I had thought the organisation I was working for was above that. It wasn’t. It was part of it.

I could have made my ethical standards clear to the CEO and management team before I started. If I had known their attitude, I would not have taken the job. If they had known mine, they wouldn’t have hired me.

My advice to others in this situation is to bring the matter out into the open, but think about your personal safety. Make sure you have a good exit plan.

An interesting thing about the culture of corruption is it can be invisible. If you didn’t look out the window into the Prague winter, you would think you were in Australia. The building was the same, the people were the same. So, you could be seduced into thinking you could operate the same way there as you do in Australia, but the culture is so very different.

.

This article was originally written for The Ethics Alliance. Find out more about this corporate membership program. Already a member? Log in to the membership portal for more content and tools here.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Are diversity and inclusion the bedrock of a sound culture?

Opinion + Analysis

Science + Technology, Business + Leadership, Society + Culture

AI might pose a risk to humanity, but it could also transform it

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships

The future does not just happen. It is made. And we are its authors.

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Is it fair to expect Australian banks to reimburse us if we’ve been scammed?

BY Steven York

Steven York is general manager, Group Compliance and Chief Security Officer at Bank of Queensland and former NSW Police Commander of the Hostage Negotiation Team and as the Negotiation Team Leader for Australia's counter terrorist negotiation team.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

How cost cutting can come back to bite you

How cost cutting can come back to bite you

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + Leadership

BY Fiona Smith The Ethics Centre 1 JAN 2018

When former Mediacom chief executive Jon Mandel revealed a rampant practice of “kickbacks” in the advertising industry two years ago, media agency CEOs around the world ducked for cover.

Media agencies, that book advertising space for clients, were essentially being paid twice for the same pieces of work and, often, not disclosing it.

While advertisers are questioning the allegiances of their agencies, those same agencies may reply, “What do you expect when your cost cutting effectively reduces our fees and commissions to zero?”

Marketing management consultant, Darren Woolley, says it is time to consider the ethical impacts of a cost-cutting culture.

“I think it is interesting to see how ethics are quickly reframed or compromised, based on profit”, says Woolley, founder and CEO of TrinityP3 Marketing Management Consultants.

In the case of the media agencies, their duty to clients is to find the most effective advertising space for their clients at the best price.

However, things become complicated when the media owners of print, radio, television, and websites started handing back a proportion of the client’s media spending to the agencies as an incentive to get more of their business.

Those “rebates” were often not disclosed to the clients and were often not passed on. They could be from around 1.67 percent to 20 percent per cent of “aggregate media spending” and took various forms.

“Clients could not be sure that the advertising space purchased was the right strategy for them, or just the most lucrative for the media agency.”

An investigation commissioned by the Association of National Advertisers (ANA) in the US also revealed media agencies were buying heavily discounted media space and not passing on or disclosing those savings to their clients. The agencies’ mark up on these transactions ranged from 30 to 90 percent.

Mandel’s “truth bomb”, delivered at a conference in the US, and the ANA report confirmed suspicions that media agencies around the world may no longer be acting in the best interests of their clients.

Clients could not be sure that the advertising space purchased was the right strategy for them, or just the most lucrative for the media agency.

Were they being pushed into digital advertising, for example, because it offered more lucrative rebates? Were their advertisements being seen by the right people in the right places?

Woolley says instances such as these have eroded trust but are the result of a number of factors affecting agency profitability, including industry disruption, rampant discounting, and endless expectations of cost-cutting by clients.

“We have been in a world of cost-cutting for ten years at least”, says Woolley.

Media agencies are also under pressure from the large holding companies that are often their owners. The holding companies and their shareholders expect to see rising profits each year, irrespective of market conditions.

“The industry is struggling. The traditional remuneration models – the way money moves through the industry, has changed. Firstly, there is less of it and there is a constant demand to do more for less”, says Woolley

“The obsession with cost is at the very core of this issue about ethics and ethical behaviour.”

Woolley says clients should be aware their own cost-cutting has contributed to agencies trying to find new ways to get paid.

“It is interesting to see at which point they [agencies] are willing to do something they wouldn’t normally do, willing to act in a way that is not in the best interests of their clients, but is in the best interests of their own company.

“To me, that is the interesting tipping point. What does it take?”

Woolley says agencies are not out to do their clients harm, but the system is supporting harmful behaviour.

That system includes an expectation that everything should always get cheaper and profits should always increase. Clients over recent years have cut their fees and commissions to media agencies from about 10 percent to around 3 or 4 percent and less, he says.

Melbourne Business School Marketing professor, Mark Ritson, has written that it is possible some media agencies are now effectively working on zero commissions and their only remuneration is through kickbacks from media owners.

“Most experts estimate that if you were to properly assess the revenue streams funding any major media agency, rebate income would significantly, and perhaps in some cases completely, overshadow commission income”, Ritson wrote in a column in The Australian newspaper in October.

Woolley says that with fierce competition from digital media owners, kickbacks have grown dramatically. Traditional media owners (newspapers, radio, and television) used to budget 20-30 percent of revenue as sales incentives, discounts, bonuses, or rebates.

But the owners of websites and social media platforms, which do not have the labour and production costs of newspapers and broadcasters, can “rebate” up to 90 percent of revenue, says Woolley.

This means there is a clear incentive to steer client advertising to digital platforms, whether it is the most effective strategy or not.

Since the widespread practise was discovered, most large advertisers have closed the kickback loophole by drafting contracts that ensure savings are passed on and don’t only benefit the agency middlemen.

“Agencies should be rewarded for delivering value and performance, not just for reducing costs.”

Some have also mitigated the risk by dividing their advertising work between multiple agencies “to keep them honest”, says Woolley.

Getting the advertising and marketing industry back on a sustainable footing will take a lot more than encouraging clients to pay a fair price for their agencies’ work or allocating a reasonable budget towards effective advertising campaigns.

Marketing executives have told Woolley they cannot convince their own chief financial officers to pay their agency more – even when that lack of investment is resulting in ineffective campaigns.

“But it is not working as it is, so everything they are spending is a waste and an increase in spending could make it functional”, he says.

Woolley says the advertising and marketing industry needs to change the conversation if it wants to survive. “It has been about cost for the last 15 years. It is not easy, but the way forward is to actually talk about value”, he says.

“Cost is a downward spiral to zero.” Agencies should be rewarded for delivering value and performance, not just for reducing costs, he says.

“By considering an ethical approach, rather than just a financial or cost approach, it will open up possibilities for people to do and think differently because, certainly, we are in a spiral.”

This article was originally written for The Ethics Alliance. Find out more about this corporate membership program. Already a member? Log in to the membership portal for more content and tools here.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

How avoiding shadow values can help change your organisational culture

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Society + Culture

A win for The Ethics Centre

Reports

Business + Leadership

Thought Leadership: Ethics in Procurement

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Business + Leadership

Repairing moral injury: The role of EdEthics in supporting moral integrity in teaching

BY Fiona Smith

Fiona Smith is a freelance journalist who writes about people, workplaces and social equity. Follow her on Twitter @fionaatwork

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Feel the burn: AustralianSuper CEO applies a blowtorch to encourage progress

Feel the burn: AustralianSuper CEO applies a blowtorch to encourage progress

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + Leadership

BY The Ethics Centre 1 JAN 2018

It would be nice to think business is stamping out bad behaviour because it is the right thing to do. But that rarely is the case.

The growing pressure from regulators and the community mean employers have little choice but to clean up their acts, says Ian Silk, the CEO of Australia’s biggest industry superannuation fund.

He’s no stranger to a bit of pressure, adept at applying the “blowtorch” to hasten positive change. With $125 billion in assets, AustralianSuper was an activist shareholder in voting against the remuneration report of the Commonwealth Bank of Australia last year.

“The more controversial the issue, the more vociferous are the people who have strong views either way and, sometimes, you are in the middle of it and you have to make a judgement as to which way you will go.”

Previously, Silk had spoken out about the need for bonuses to be awarded for exceptional results, not just for performing the required tasks and, in the case of CBA, was arguing for more rigour around the bonus process.

The fund has also pledged to vote against the appointment of male non-executive directors where there are no women on the boards.

In an interview with The Ethics Centre, Silk says AustralianSuper’s high profile brings an obligation to speak out on “certain issues”.

“The more controversial the issue, the more vociferous are the people who have strong views either way and, sometimes, you are in the middle of it and you have to make a judgement as to which way you will go”, he says.

Ethics in business is a hot topic, particularly in the financial services sector.

“[It is], in a very large measure, a response to the egregious behaviour that is now so well publicised and readily-known by the public”, says Silk.

“Everybody knows unethical behaviour when they see it and I think there is a move back to appropriate norms. I think there is a recognition that much of the bad behaviour in the financial services sector is wrong.”

Silk says it is difficult to discern if this revitalised interest in ethics is deeply-felt, or whether it is a protective measure to avoid getting caught and penalised

“But I think there is a slow improvement in behaviour, much of it regulator and government led, but much of it community-led, consumer-led, some industry associations take a strong position on it.”

In terms of standards in his own organisation, Silk says he had been confident that the culture and behaviours at AustralianSuper would stand up to scrutiny. This is partly because, as a member-organisation, its sole purpose is to act in the interest of members and this provides a de facto ethical framework, he says.

However, earlier this year, he decided to get a second opinion. The Ethics Centre was engaged to undertake a “culture audit” to test whether the fund’s policies, procedures and practices were aligned with its purpose, values and principles.

“In my darkest moments, I just wondered if we had all drunk the Kool-Aid”, he says.

The results were gratifyingly positive and were affirmation that AustralianSuper and its 550 staff are on the right track, says Silk, who has led the fund since it was founded in 2006.

However, The Ethics Centre also found some areas for improvement, including a culture that could be “conflict averse”.

“We weren’t as robust as we might be. There was a tendency to avoid conflict in certain parts of the organisation, so we could introduce a bit more aggression into the organisation – aggression in a positive sense”, he says.

“People who are rude to others are counselled and abusive language or behaviour is not tolerated and could be regarded as a sacking offence.”

“Those areas where improvement opportunities were identified, we have consciously thought that we want to do something about that, we want to lift the standard in the organisation … so we have an action plan, we have done all the things that you might do with a business plan, we have identified all the particular areas, we have assigned responsibility to people, we are going to check in periodically to make sure progress has occurred.

“We haven’t just used it as a soft survey.”

It is too early to see much in terms of a change in culture since The Ethics Centre report was completed, but Silk says some progress has been noticed, such as more robust questioning in meetings.

“We are getting better outcomes as a result”, he says.

Silk’s commitment to respectful behaviours is well known. According to a recent report in the Australian Financial Review, every recruit to the organisation gets a one-and-a-half hour briefing from Silk on the fund’s four values.

People who are rude to others are counselled and abusive language or behaviour is not tolerated and could be regarded as a sacking offence.

The Ethics Alliance sat down for a further conversation with Ian. He shared his insights on the importance of discussing ethics with your network, why organisations always need to work toward good ends, and why leaders can’t just talk the talk. They need to walk the walk.

This article was originally written for The Ethics Alliance. Find out more about this corporate membership program. Already a member? Log in to the membership portal for more content and tools here.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Society + Culture

The Ethics Centre: A look back on the highlights of 2018

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Business + Leadership

Political promises and the problem of ‘dirty hands’

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Climate + Environment

The business who cried ‘woke’: The ethics of corporate moral grandstanding

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Why the future is workless

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Managing corporate culture

It’s not uncommon these days to hear regulators sounding warnings about culture.

They point out that it’s a crucial role of boards to determine the purpose, values and principles of the company they govern, whilst the CEO and senior management have responsibility for implementing the desired culture. Personnel in human resources, ethics, compliance, and risk functions all have a role to play in embedding values and ethics.

Culture, we hear, has an important role to play in risk management and risk appetite. Weak risk cultures are often the root cause of the most spectacular governance failures. Firms lacking good corporate culture will fail investors and stakeholders.

“Trust, like beauty, is in the eye of the beholder,” says John Price, Commissioner of the Australian Securities and Investment Commission (ASIC). “If consumers don’t like the way a firm has behaved, they can take their business elsewhere and tell everyone about it through the wonders of social media. Loss of reputation due to poor conduct destroys value in a firm. Even more challenging is that poor conduct may be technically within the law, but still have negative impact on a firm’s reputation.

“The possible loss of trust and confidence is a key business risk. If the conduct of a firm genuinely reflects ‘doing the right thing,’ this mitigates conduct risk and will be rewarded with longevity, customer loyalty, and a sustainable business.”

All very well, we hear you say: but how does a company manage culture? What does good culture even look like? By what standard do we measure it or assess it? How do you shift from the culture you’ve got today to the culture you aspire to for the future?

The Ethics Centre has been exploring this subject for many years, developing frameworks and methodologies for measuring and improving culture along the way. We’ve played a significant advocacy role as well, arguing for boards to accept responsibility for setting and maintaining the culture standard in the organisations they govern.

The Ethics Centre recently partnered with the Governance Institute, the Institute of Internal Auditors and Chartered Accountants Australia to produce Managing Culture – A Good Practice Guide. This publication sets out to define culture and explores challenges in identifying, monitoring and driving culture, including organisational change programs. The guide also explores the importance of embedding culture and the nature of the board’s role in evaluating and overseeing culture.

Research has shown that companies that have a good culture perform better than companies that do not. The Guide outlines how each group in an organisation can contribute to a good culture, the first step of which is to create an ethical framework that provides guidance on decisions and an appropriate ‘tone from the top’.

While having an integrated governance and risk management framework is important, unless an organisation establishes a culture that promotes risk awareness into everything it does, it is unlikely to achieve its objectives. Governance and risk management must be at the core of an organisation’s culture.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Society + Culture

Four causes of ethical failure, and how to correct them

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

The anti-diversity brigade is ruled by fear

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships

There are ethical ways to live with the thrill of gambling

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

In the court of public opinion, consistency matters most

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Bladerunner, Westworld and sexbot suffering

Bladerunner, Westworld and sexbot suffering

Opinion + AnalysisScience + Technology

BY Kym Middleton The Ethics Centre 12 DEC 2017

The sexbots and robo-soldiers we’re creating today take Bladerunner and Westworld out of the science fiction genre. Kym Middleton looks at what those texts reveal on how we should treat humanlike robots.

It’s certain: lifelike humanoid robots are on the way.

With guarantees of Terminator-esque soldiers by 2050, we can no longer relegate lifelike robots to science fiction. Add this to everyday artificial intelligence like Apple’s Siri, Amazon’s Alexa and Google Home and it’s easy to see an android future.

The porn industry could beat the arms trade to it. Realistic looking sex robots are being developed with the same AI technology that remembers what pizza you like to order – although it’s years away from being indistinguishable from people, as this CNET interview with sexbot Harmony shows.

Like the replicants of Bladerunner we first met in 1982 and the robot “hosts” of HBO’s remake of the 1973 film Westworld, these androids we’re making require us to answer a big ethical question. How are we to treat walking, talking robots that are capable of reasoning and look just like people?

Can they suffer?

If we apply the thinking of Australian philosopher Peter Singer to the question of how we treat androids, the answer lies in their capacity to suffer. In making his case for the ethical consideration of animals, Singer quotes Jeremy Bentham:

“The question is not, Can they reason? nor Can they talk? but, Can they suffer?”

An artificially intelligent, humanlike robot that walks, talks and reasons is just that – artificial. They will be designed to mimic suffering. Take away the genuine experience of physical and emotional pain and pleasure and we have an inanimate thing that only looks like a person (although the word ‘inanimate’ doesn’t seem an entirely appropriate adjective for lifelike robots).

We’re already starting to see the first androids like this. They are, at this point, basically smartphones in the form of human beings. I don’t know about you, but I don’t anthropomorphise my phone. Putting aside wastefulness, it’s easy to make the case you should be able to smash it up if you want.

But can you (spoiler) sit comfortably and watch the human-shaped robot Dolores Abernathy be beaten, dragged away and raped by the Man in Black in Westworld without having an empathetic reaction? She screams and kicks and cries like any person in trauma would. Even if robot Dolores can’t experience distress and suffering, she certainly appears to. The robot is wired to display pain and viewers are wired to have a strong emotional reaction to such a scene. And most of us will – to an actress, playing a robot, in a fictional TV series.

Let’s move back to reality. Let’s face it, some people will want to do bad things to commercially available robots – especially sexbots. That’s the whole premise of the Westworld theme park, a now not so sci-fi setting where people can act out sexual, violent, and psychological fantasies on android subjects without consequences. Are you okay with that becoming reality? What if the robots looked like children?

The virtue ethicist’s approach to human behaviour is to act with an ideal character, to do right because that’s what good people do. In time, doing the virtuous thing will be habit, a natural default position because you internalise it. The virtue ethicist is not going to be okay with the Man in Black’s treatment of Dolores. Good people don’t have dark fantasies to act out on fake humans.

The utilitarian approach to ethical decisions depends on what results in the most good for the largest amount of people. Making androids available for abuse could be a case for community safety. If dark desires can be satiated with robots, actual assaults on people could reduce. (In presenting this argument, I’m not proposing this is scientifically proven or that it’s my view.) This logic has led to debates on whether virtual child porn should be tolerated.

The deontologist on the other hand is a rule follower so unless androids have legal protections or childlike sexbots are banned in their jurisdiction, they are unlikely to hold a person who mistreats one in ill regard. If it’s your property, do whatever you’re allowed to do with it.

Consciousness

Of course, (another spoiler) the robots of Westworld and Bladerunner are conscious. They think and feel and many believe themselves to be human. They experience real anguish. Singer’s case for the ethical treatment of animals relies on this sentience and can be applied here.

But can we create conscious beings – deliberately or unwittingly? If we really do design a new intelligent android species, complete with emotions and desires that motivate them to act for themselves, then give them the capacity to suffer and make conscientious choices, we have a strong case for affording robot rights.

This is not exactly something we’re comfortable with. Animals don’t enjoy anything remotely close to human rights. It is difficult seeing us treat man made machines with the same level of respect we demand for ourselves.

Why even AI?

As is often with matters of the future, humanlike robots bring up all sorts of fascinating ethical questions. Today they’re no longer fun hypotheticals. It is important stuff we need to work out.

Let’s assume for now we can’t develop the free thinking and feeling replicants of Bladerunner and hosts of Westworld. We still have to consider how our creation and treatment of androids reflects on us. What purpose – other than sexbots and soldiers – will we make them for? What features will we design into a robot that is so lifelike it masterfully mimics a human? Can we avoid designing our own biases into these new humanoids? How will they impact our behaviour? How will they change our workplaces and societies? How do we prevent them from being exploited for terrible things?

Maybe Elon Musk is right to be cautious about AI. But if we were “summoning the demon”, it’s the one inside us that’ll be the cause of our unease.

Follow The Ethics Centre on Twitter, Facebook, Instagram and LinkedIn.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Science + Technology

A framework for ethical AI

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Science + Technology

MIT Media Lab: look at the money and morality behind the machine

Opinion + Analysis

Science + Technology

The Ethics of In Vitro Fertilization (IVF)

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Science + Technology

Who’s to blame for Facebook’s news ban?

BY Kym Middleton

Former Head of Editorial & Events at TEC, Kym Middleton is a freelance writer, artistic producer, and multi award winning journalist with a background in long form TV, breaking news and digital documentary. Twitter @kymmidd

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Big Thinker: Simone Weil

Philosophy had a big moment in 20th century Europe. Christian mysticism? Not so much.

Meet Simone Weil (1909—1943) – French philosopher, political activist, Christian mystic and enfant terrible. Described by John Berger as a “heretical theologian”, Albert Camus as “the only great spirit of our times”, and André Weil (her brother) as “the greatest pain in the arse for rectors and school directors”, Weil was – and remains – one of philosophy’s more divisive characters

Uprootedness

According to Weil, post-World War II France was adrift in a deep malaise she called uprootedness. She argued France’s lack of connectedness to its past, its land, and its community had culminated in its defeat by Germany. Her solution? To find spirituality in work.

This would look different in city and country. In urban areas, treating uprootedness meant finding a motivation for work other than money.

Weil admitted that for low income and unemployed adults in war ravaged France, this would be impossible. Instead, she focused on their children. Reviving the original Tour de France, encouraging apprenticeships, and bringing joy back into study were her recommendations. This way, work could be intriguing and compelling. Even “lit up by poetry”.

For those in the country, uprootedness looked like boredom and an indifference to the land. Optional studies of science, religion, more apprenticeships and cultivating a strong need to own land was essential. To remember the water cycle, photosynthesis and Biblical shepherds while working could only invoke awe, Weil surmised. Even the fatigue of labour would turn poetic.

Her vision for reform extended to French colonialism. This was a source of deep shame for Weil, admitting that she could not meet “an Indochinese person, an Algerian, a Moroccan, without wanting to ask his forgiveness”. She saw uprootedness most acutely in those whose homelands had been invaded. It was also a clear example of the cyclical nature of uprootedness: for the fiercest invaders were uprooted people uprooting others.

Attention over will

The spirituality of academic work was just as important to Weil. In practice, this looked like attention. She defined attention as the capacity to hold different ideas without judgement. In doing so, the student would be able to engage with ideas and slowly land on an answer.

She argued that when a student is motivated by good grades or social ranking, they arrest their development of attention and lose all joy in learning. Instead, they pounce on any semblance of answer or solution, even if half-formed or incorrect, to seem impressive. Social media, anyone?

According to Weil, true knowledge could not be willed. Instead, the student should put their efforts into making sure they paid attention when it arrived.

Weil believed humanity’s search for truth was their search for nearness to God or Christ. If God or Christ was the source of ‘Truth’, every new piece of knowledge or fact learned would refer to them. Therefore, in each student’s instance of unmixed attention – to a geometry problem, a line of poetry, or a cry for help from someone in need – was an opportunity for spiritual transformation.

This detachment from social mores and movement away from the ego characterised her mysticism. It makes a lot of sense then, that Weil considered the height of attention to be prayer.

Obligations over rights

Weil believed that justice was concerned with obligations, not rights. One of her criticisms of political parties lay in their language of rights, calling it “a shrill nagging of claims and counter-claims”.

Justice, for Weil, consisted of making sure no harm is done to one another. Weil asserted that when the man who is hurt cries ‘why are you hurting me?’ he invokes the spirit of love and attention. When the second man cries ‘why has he got more than I have?’ his due becomes conditional on power and demand.

The obligation of justice, Weil noted, is fundamentally unconditional. It is eternal and based upon a duty to the very nature of humanity. In a sense, what Weil is describing is the Golden Rule, found in every major religious tradition and every strand of moral philosophy – to treat others as you would like to be treated.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Ask an ethicist: How much should politics influence my dating decisions?

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Stoicism

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

You don’t like your child’s fiancé. What do you do?

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Politics + Human Rights, Relationships, Science + Technology

The value of a human life

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Why victims remain silent and then find their voice

Why victims remain silent and then find their voice

Opinion + AnalysisPolitics + Human RightsRelationships

BY Dennis Gentilin The Ethics Centre 7 DEC 2017

TIME Magazine’s announcement comes amid a storm of reckoning with sexual harassment and abuse charges in power centres worldwide. The courageous victims who, over the past few months, surfaced and made public their experiences of sexual harassment have sparked a social movement – typified in the hashtag #MeToo.

One of the features of the numerous sexual harassment claims that have been made public is the number of victims that have come forward after the first allegations have surfaced. Women, many of whom have suffered in silence for a considerable period of time, all of a sudden have found their voice.

As an outsider not involved in these incidents, this pattern of behaviour might be difficult to comprehend. Surely victims would speak up and take their concerns to the appropriate authorities? Unfortunately, we are very poor at judging how we would behave when we are placed in difficult, stressful situations, as previous research has found.

How we imagine we would respond in hypothetical situations as an outsider differs significantly to how we would respond in reality – we are very poor at appreciating how the situation can influence our conduct.

In 2001, Julie Woodzicka and Marianne LaFrance asked 197 women how they would respond in a job interview if a man aged in his thirties asked them the following questions: “Do you have a boyfriend?”, “Do people find you desirable?” and “Do you think women should be required to wear bras at work?” Over two-thirds said they would refuse to answer at least one of the questions whilst sixteen of the participants said they would get up and leave.

When Woodzicka and LaFrance placed 25 women in this situation (with an actor playing the role of the interviewer), the results were vastly different. None of the women refused to answer the questions or left the interview.

In all these incidents of sexual abuse we typically find that an older man, who is more senior in the organisation or has a higher social status, preys on a younger, innocent woman. And perhaps most importantly, the perpetrator tends to hold the keys to the victim’s future prospects.

And there are many reasons why people remain silent. Three of the most common are fear, futility and loyalty – we fear consequences, we surmise that speaking up is futile because no action will be taken, or, as strange as it might sound, we feel a sense of loyalty to the perpetrator or our team.

There are a variety of dynamics that can cause people to reach these conclusions. The most common is power. In all these incidents of sexual abuse we typically find that an older man, who is more senior in the organisation or has a higher social status, preys on a younger, innocent woman. And perhaps most importantly, the perpetrator tends to hold the keys to the victim’s future prospects.

In these types of situations, it is easy to see how the victim can lose their sense of agency and feel disempowered. They might feel that even if they did speak up, nobody would believe their story. The mere thought of challenging such a “highly respected” individual is too daunting. Worse yet, their career would be irreparably damaged. Perhaps, by keeping quiet, they could get the break they need and put the experience behind them.

A second dynamic at play is what psychologists refer to as pluralistic ignorance. First conceived in the 1930s, it proposes that the silence of people within a group promotes a misguided belief of what group members are really thinking and feeling.

In the case of sexual harassment, when victims remain silent they create the illusion that the abuse is not widespread. Each victim feels they are isolated and suffering alone, further increasing the likelihood that they will repress their feelings.

By speaking out, women have shifted the norms surrounding sexual assault. Behaviour which may have been tolerated only a few years (perhaps months) ago is now out of bounds.

But as the events of the past few weeks have demonstrated, the norms promoting silence can crumble very quickly. People who suppress their feelings can find their voice as others around them break their silence. As U.S. legal scholar Cass Sunstein recently wrote in the Harvard Law Review Blog, as norms are revised, “what was once unsayable is said, and what was once unthinkable is done.”

And this is exactly what has happened over the past few months. Both perpetrators and victims alike are now reflecting on past indiscretions and questioning whether boundaries were crossed.

Only time will tell whether the shift in norms is permanent or fleeting. As is always the case with changes in social attitudes, this will be determined by a myriad of factors. The law plays a role but as the events of the past few months have demonstrated it is not as important as one might think.

Among other things, it will require the continued courage of victims. But perhaps more importantly it will require men, especially those who are in positions of power and respected members of our communities and institutions, to role model where the balance resides between extreme prudery at one end, and disgusting lechery on the other.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

Is the right to die about rights or consequences?

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

Meet Eleanor, our new philosopher in residence

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

Lessons from Los Angeles: Ethics in a declining democracy

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture, Relationships

Whose fantasy is it? Diversity, The Little Mermaid and beyond

BY Dennis Gentilin

Dennis Gentilin is an Adjunct Fellow at Macquarie University and currently works in Deloitte’s Risk Advisory practice.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Big Thinker: Bill Mollison

Bill Mollison (1928—2016) was an Australian ecologist and the ‘father of permaculture’, a type of agricultural design and practice he created, named and taught.

Having co-wrote Permaculture One with his student and colleague David Holmgrem, Mollison later founded the Permaculture Institute of Tasmania and taught his Permaculture Design Course and Certificate (PDCC) all around the world.

Today, his philosophy has reached millions. His commitment to ethics brings philosophy back into the marketplace and onto the farm – down to its earthworms and well-tilled soil.

What is permaculture?

Permaculture is an ethical design framework for sustainable farming. It combines traditional farming methods of Indigenous and Aboriginal communities with renewable technologies and low-energy materials. Masanobu Fukuoka, a Japanese farmer and creator of “Do-nothing Farming”, is cited as another influence on Mollison’s farming philosophy.

Mollison believed that farming monocultures, like corn, or wheat, was unsustainable. Instead, he called for ‘food forests’ – a varied collection of plant and tree species that support equally as diverse animal life.

Like a delicate structure of checks and balances, the little relationships formed in such an ecosystem would keep it self-sufficient. According to Mollison, once complete, a successful permaculture design wouldn’t need any human touch at all.

What’s wrong with what we’ve got now?

Because monocultures are more efficient, fast and easy to harvest, they’ve been the go-to for industrial farming. But, according to Mollison, their future is limited, with no means to reproduce the same healthy ecosystem it profits from. In fact, it’s often expected to meet the surplus demand of nations that already have enough food.

Mollison considered this form of agriculture as unethical, self-destructive and “temporary”. Rather than people being relied on to provide yields, he wanted to make us another part of the agricultural web. No more, no less.

This, along with permaculture’s three core ethics (earth care, people care and fair share), would transform how plants, animals and humans all interact with each other. People – not just farmers – would turn into active stewards of the earth. The social and economic needs of interdependent communities would be satisfied and looked after, with global surplus distributed to those most in need.

Some people find his views noble, but unrealistic. Indeed, his repositioning of farming as political might be novel. But applying ethics to fulfil basic needs of food and shelter, to Mollison, is essential:

“The greatest change we need to make is from consumption to production, even if on a small scale, in our own gardens. If only 10% of us can do this, there is enough for everyone. Hence the futility of revolutionaries who have no gardens, who depend on the very system they attack, and who produce words and bullets, not food and shelter.”

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Big thinker

Climate + Environment, Relationships

Big Thinker: Ralph Waldo Emerson

Explainer

Climate + Environment

Ethics Explainer: Longtermism

Opinion + Analysis

Climate + Environment, Health + Wellbeing

How should vegans live?

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Climate + Environment

Blindness and seeing

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

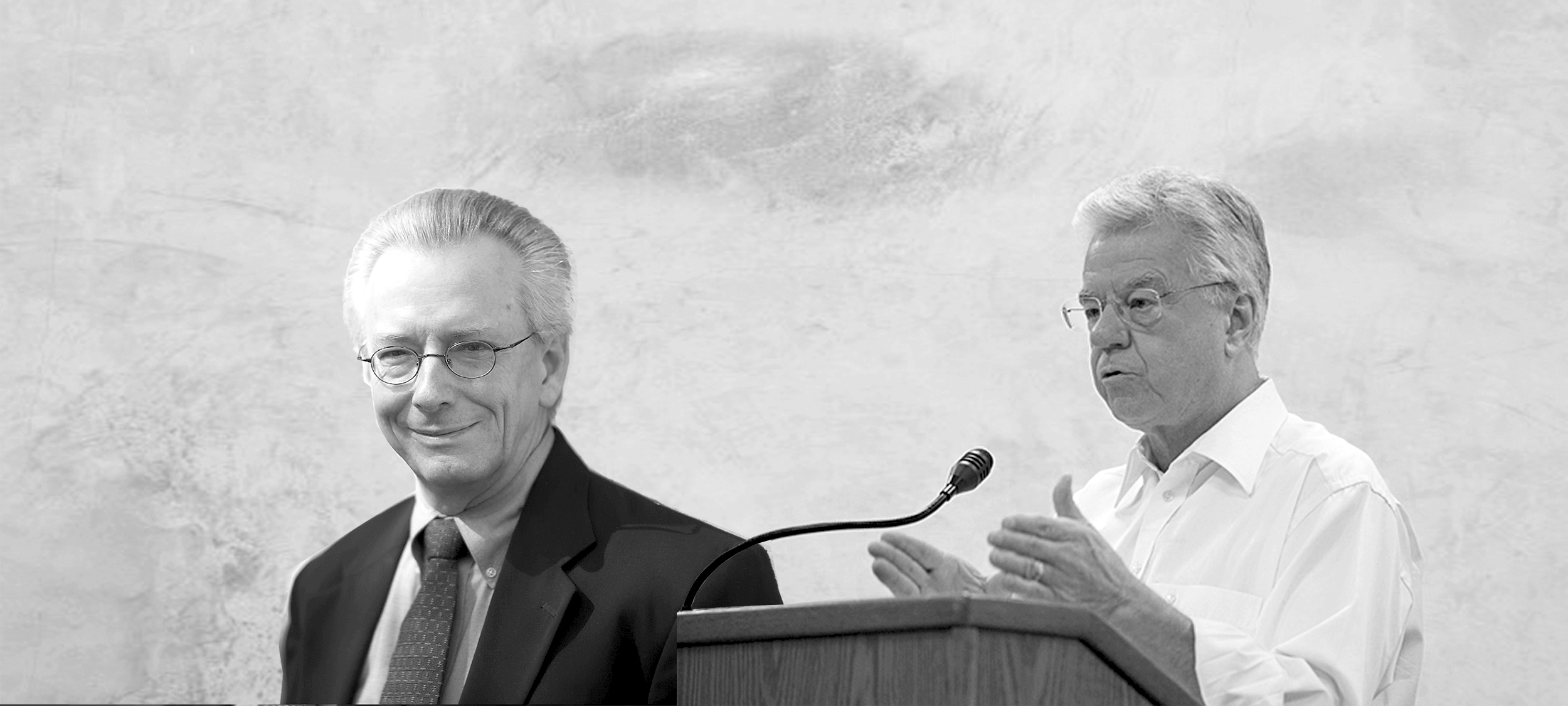

Big Thinkers: Thomas Beauchamp & James Childress

Big Thinkers: Thomas Beauchamp & James Childress

Big thinkerHealth + WellbeingPolitics + Human Rights

BY The Ethics Centre 1 DEC 2017

Thomas L Beauchamp (1939—present) and James F Childress (1940—present) are American philosophers, best known for their work in medical ethics. Their book Principles of Biomedical Ethics was first published in 1985, where it quickly became a must read for medical students, researchers, and academics.

Written in the wake of some horrific biomedical experiments – most notably the Tuskegee Syphilis Study, where hundreds of rural black men, their partners, and subsequent children were infected or died from treatable syphilis – Principles of Biomedical Ethics aimed to identify healthcare’s “common morality”. These are its four principles:

- Respect for autonomy

- Beneficence

- Non-maleficence

- Justice

These principles are often in tension with one another, but all healthcare workers and researchers need to factor each into their reflections on what to do in a situation.

Respect for autonomy

Philosophers usually talk about autonomy as a fact of human existence. We are responsible for what we do and ultimately any action we take is the product of our own choice. Recognising this basic freedom at the heart of humanity is a starting point for Beauchamp and Childress.

By itself, the idea human beings are free and in control of themselves isn’t especially interesting. But in a healthcare setting, where patients are often vulnerable and surrounded by experts, it is easy for a patient’s autonomous decision to be disrespected.

Beauchamp and Childress were writing at a time when the expertise of doctors meant they often took extreme measures in doing what they had decided was in the best interests of their patient. They adopted a paternalistic approach, treating their patients like uninformed children rather than autonomous, capable adults. This went as far as performing involuntary sterilisations. In one widely discussed court case in bioethics, Madrigal v Quillian, ten Latina women in the US successfully sued after doctors performed hysterectomies on them without their informed consent.

Legally speaking, the women in Madrigal v Quillian had provided consent. However, Beauchamp and Childress explain clearly why the kind of consent they provided isn’t adequate. The women – who spoke Spanish as a first language – were all being given emergency caesareans. They were asked to sign consent forms written in English which empowered doctors to do what they deemed medically necessary.

In doing so, they weren’t being given the ability to exercise their autonomy. The consent they provided was essentially meaningless.

To address this issue, Beauchamp and Childress encourage us to think about autonomy as creating both ‘negative’ and ‘positive’ duties. The negative duty influences what we must not do: “autonomous actions should not be subject to controlling constraints by others”, they write. But positively, autonomy also requires “respectful treatment in disclosing information” so people can make their own decisions.

Respecting autonomy isn’t just about waiting for someone to give you the OK. It’s about empowering their decision making so you’re confident they’re as free as possible under the circumstances.

Nonmaleficence: ‘first do no harm’

The origins of medical ethics lie in the Hippocratic Oath, which although it includes a lot of different ideas, is often condensed to ‘first do no harm’. This principle, which captures what Beauchamp and Childress mean by non-maleficence, seems sensible on one level and almost impossible to do in practice on another.

Medicine routinely involves doing things most people would consider harmful. Surgeons cut people open, doctors write prescriptions for medicines with a range of side effects, researchers give sick people experimental drugs – the list goes on. If the first thing you did in medicine was to do no harm, it’s hard to see what you might do second.

This is clearly too broad a definition of harm to be useful. Instead, Beauchamp and Childress provide some helpful nuance, suggesting in practice, ‘first do no harm’ means avoiding anything which is unnecessarily or unjustifiably harmful. All medicine has some risk. The relevant question is whether the level of harm is proportionate to the good it might achieve and whether there are other procedures that might achieve the same result without causing as much harm.

Beneficence: do as much good as you can

Some people have suggested Beauchamp and Childress’s four principles are three principles. They suggest beneficence and non-maleficence are two sides of the same coin.

Beneficence refers to acts of kindness, charity and altruism. A beneficent person does more than the bare minimum. In a medical context, this means not only ensuring you don’t treat a patient badly but ensuring you treat them well.

The applications of beneficence in healthcare are wide reaching. On an individual level, beneficence will require doctors to be compassionate, empathetic and sensitive in their ‘bedside manner’. On a larger level, beneficence can determine how a national health system approaches a problem like organ donation – making it an ‘opt out’ instead of ‘opt in’ system.

The principle of beneficence can often clash with the principle of autonomy. If a patient hasn’t consented to a procedure which could be in their best interests, what should a doctor do?

Beauchamp and Childress think autonomy can only be violated in the most extreme circumstances: when there is risk of serious and preventable harm, the benefits of a procedure outweigh the risks and the path of action empowers autonomy as much as possible whilst still administering treatment.

However, given the administration of medical procedures without consent can result in legal charges of assault or battery in Australia, there is clearly still debate around how to best balance these two principles.

Justice: distribute health resources fairly

Healthcare often operates with limited resources. As much as we would like to treat everyone, sometimes there aren’t enough beds, doctors, nurses or medications to go around. Justice is the principle that helps us determine who gets priority in these cases.

However, rather than providing their own theory, Beauchamp and Childress pointed out the various different philosophical theories of justice in circulation. They observe how resources are distributed will depend on which theory of justice a society subscribes to.

For example, a consequentialist approach to justice will distribute resources in the way that generates the best outcomes or most happiness. This might mean leaving an elderly patient with no dependents to die in order to save a parent with young children.

By contrast, they suggest someone like John Rawls would want the access to health resources to be allocated according to principles every person could agree to. This might suggest we allocate resources on the basis of who needs treatment the most, which is the way paramedics and emergency workers think when performing triage.

Beauchamp and Childress’s treatment of justice highlights one of the major criticisms of their work: it isn’t precise enough to help people decide what to do. If somebody wants to work out how to distribute resources, they might not want to be shown several theories to choose between. They want to be given a framework for answering the question. Of course when it comes to life and death decisions, there are no easy answers.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Health + Wellbeing, Society + Culture

Ethical concerns in sport: How to solve the crisis

Opinion + Analysis

Climate + Environment, Politics + Human Rights

Are we idolising youth? Recommended reads

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing

Women’s pain in pregnancy and beyond is often minimised

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships, Society + Culture