Ask an ethicist: Is it OK to steal during a cost of living crisis?

Ask an ethicist: Is it OK to steal during a cost of living crisis?

Opinion + AnalysisSociety + Culture

BY Tim Dean 17 SEP 2024

The cost of groceries is spiralling out of control. Meanwhile, the major supermarkets are making a killing. I can barely afford the fuel to get to work, let alone fresh food for dinner. Surely, it’s OK for me to pilfer the odd packet of beef patties or punnet of strawberries?

It sometimes feels like the grand bargain of society is breaking down. We’re told that if we work hard, get a good education and don’t cause trouble then things will all work out – we’ll get a good job, be able to buy a home and we can still afford the odd luxury. But many of us are discovering that even when we play by the rules, we still feel like we’re falling behind.

And then we see the price of asparagus has gone up again. It’s not like asparagus farmers are getting rich. Neither are we. But the supermarket duopoly is. The outrage at this apparent injustice is understandable. And some of that outrage is tipping over into shoplifting, with the big supermarkets registering a surge in theft.

But – brace yourself – as an ethicist, I’m going to remind you that stealing is wrong. Well, it’s almost always wrong, especially if you’re only stealing out of a sense of outrage.

The thing about outrage is that it demands satisfaction. It motivates us to punish a perceived wrongdoer. But whom do we punish when the wrongdoing isn’t perpetrated by an individual but by an unjust system? It might feel justified to place a finger on the scale to tip things back in our favour by nabbing a few essentials (and the odd packet of TimTams). But in doing so, we risk letting one injustice lead to another without actually tackling the problem in the first place. We might feel like we deserve fairer prices – and I think we do – but stealing isn’t the way to make that happen.

But surely pilfering a couple of peaches and a jar of pickles is a victimless crime. The big supermarkets are making a motza, and they factor theft into their bottom line. That’s a trifling loss for them, and a nice peach and pickle cocktail for me.

Here’s a pickle for you. While a single instance of shoplifting might not have a big impact, every instance adds up. Because supermarkets do factor in theft to their prices, the more stuff that goes missing, the more they jack up prices – not to mention investing more in anti-theft technology. So, you’re in part contributing to the very problem that is motivating your theft. And those higher prices impact everyone, including those who might be struggling even more than you are.

At the heart of ethics is the idea that we should take responsibility for our actions. Do you want to be responsible for making the cost of living crisis worse?

Then there’s the matter of principle. Every time you feel justified stealing, you’re allowing others to use that same justification to steal. You’re effectively endorsing stealing in general.

One missing pickle jar might not make much of an impact on prices, but if everyone swipes something, then pickles can pretty quickly become out of reach.

OK, OK. I’ll redirect my outrage to writing sternly worded letters to the newspaper about grocery prices. But what if I’m starving because I can’t afford even a packet of Kraft singles to get through the day? Is stealing justified then?

As I said earlier, stealing is almost always wrong. But not always. Mortal peril is one case where most ethicists would say that it’s permissible to steal. Say your child is dying of a preventable disease and needs medication immediately, but your local supplier jacks up the price to an unaffordable level at the last moment and refuses to make an exception. If there’s no other ethical way to save your child’s life, then stealing could be forgiven.

However, that doesn’t mean raiding the lolly aisle. Note the “no other ethical way” bit. Generally, we’re obliged to do everything we can to work within the bounds of ethics and the law before we step outside of them. So, if you’re struggling to afford food, and there’s a food bank nearby that is willing to help you out, then that’s where you ought to turn before stuffing celery down your jumper.

Similarly, if there were some perverse law that prevented you from legitimately buying necessities, then you could pull a Martin Luther King Jr and ignore that law. As he said:

“One has not only a legal, but a moral responsibility to obey just laws. Conversely, one has a moral responsibility to disobey unjust laws.”

In short: stealing is bad, unless stealing will prevent something worse from happening. If not, then leave that punnet of strawberries alone and save your stamina for fighting the unjust system in other ways.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Health + Wellbeing, Society + Culture

I changed my mind about prisons

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture, Relationships

Where is the emotionally sensitive art for young men?

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

Meet Joseph, our new Fellow exploring society through pop culture

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Society + Culture

Does ethical porn exist?

BY Tim Dean

Dr Tim Dean is a public philosopher, speaker and writer. He is Philosopher in Residence and Manos Chair in Ethics at The Ethics Centre.

We are witnessing just how fragile liberal democracy is – it’s up to us to strengthen its foundations

We are witnessing just how fragile liberal democracy is – it’s up to us to strengthen its foundations

Opinion + AnalysisPolitics + Human Rights

BY Tim Dean 22 JUL 2024

Unless we want to slip into a world where force and coercion drive politics, then we all must invest in reinforcing the institutions that keep liberal democracy working.

For most of human history, politics was — and in many parts of the world today, still is — a wilderness. Political victories were won at the point of a spear or the barrel of a gun, rather than at the ballot box. When there was a dispute about whose interests ought to take priority, how to distribute resources, or even who gets to have a say in how people live their lives, it was those who wielded the greatest force who typically got to choose. And, unsurprisingly, they often chose in favour of themselves.

This makes liberal democracy an historical anomaly. Within liberal democracy, we fully expect there to be disagreements about how best to run society — not least because the “liberal” part allows each person to define their own vision of a good life rather than having one imposed on us by others. But in liberal democracy, these disagreements are not won through coercive force but through persuasion, or as the German liberal philosopher Jürgen Habermas puts it, “the unforced force of the better argument”.

But the wall of civility surrounding the garden of liberal democracy is not impregnable. Coercive force lingers just outside, threatening to burst in and bypass the messy process of persuasion — as it did on 13 July 2024, when a would-be assassin attempted to silence former President Donald Trump with an assault rifle rather than words.

The good news is that the near universal expressions of shock and condemnation at the attempted assassination show that most people in the United States, and in other liberal democracies, still prefer to resolve their disputes within the norms of the liberal democratic garden rather than returning to the wilderness. Still, this episode serves as a potent reminder of just how fragile and important the norms that preserve liberal democracy are, and that the institutions that enable peaceful political debate require constant reinforcement.

The grand bargain

The problem is that, in recent years, liberal democracy has been failing itself. One of the “unforced forces” that keeps the system operating is a tacit buy-in on behalf of every individual within the system. We need to believe that the system is working for us, that it’s fair, and that our voice matters, otherwise we have little incentive to work within it. If we feel powerless, disenfranchised, embattled or feel our livelihood or safety is threatened, we have more reason to step outside the walls of civility.

But liberal democracies, such as the United States — and to a lesser but nonetheless significant extent, Australia — have often failed to give us good reason to believe the system is working.

For many of us, the “grand bargain” of liberal democratic society is breaking down. This bargain states that if we work hard, get a good education, and play by the rules, then we’ll have every opportunity to live a fulfilled and fulfilling life. But that’s just not the reality for a large proportion of the population. Many liberal democracies are facing an omni-crisis — combining housing, inflation, wealth inequality, climate change, mental health, loneliness, childcare, aging, the erosion of traditional jobs, the fragmentation of communities, as well as racism, sexism and other forms of systemic discrimination, and more besides.

If people feel powerless or disenfranchised, they’ll reject the constraints the system places on them to engage in peaceful debate.

Or if they feel that the stakes are so high that they can’t afford to let the other side win, then they’ll reject the ballot box and turn to other means to achieve their political ends.

How to restore faith in liberal democracy

Of course, those in power must not neglect their responsibility to protect and strengthen the system, and restore the grand bargain, even if they might forego short-term political or financial advantage in doing so.

Although it’s up to us to hold them to account. We should demand more of our elected representatives. But we must demand more of ourselves as well. We must lower the temperature of popular discourse: tune out the hyperbole, avoid partisan media, carefully curate our social media, don’t engage with those promoting conspiracy theories, and refuse to feed the trolls. Listen and ask questions of people who have different opinions. Advance our views with conviction, but also with humility. Acknowledge that there is probably not one right answer to many of the challenges we face, and that compromise is inevitable.

Just as important is building the social foundations that enable civil but spirited discourse. That means investing in our local communities to build “social capital” — the trust, respect, and norms of reciprocity that keep society functioning. Talking to your neighbour over the fence, taking your dog to the park, participating in a class at your local community centre, volunteering for a local organisation, joining an activist group — these are the grassroots of the liberal democratic garden, and they’re just as important as the larger institutions. They reinforce our common humanity; our neighbour might vote differently to us, but we still share the same human concerns.

As American political commentator Yuval Levin has stated, those we disagree with aren’t just going to disappear if we coerce them into silence or bully our way into power. Their views will persist, and if we give them no voice, they will be motivated to find other ways to be heard. We must practice tolerance and compromise, because the alternative is a return to the wilderness.

Catch Democracy is Not Worth Dying For at The Festival of Dangerous Ideas, Sunday 25 August at Carriageworks, Sydney. Tickets on sale now.

This article was originally published by ABC religion and Ethics.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights

Could a virus cure our politics?

Opinion + Analysis

Climate + Environment, Politics + Human Rights

Is it time to curb immigration in Australia?

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

Is constitutional change what Australia’s First People need?

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

The erosion of public trust

BY Tim Dean

Dr Tim Dean is a public philosopher, speaker and writer. He is Philosopher in Residence and Manos Chair in Ethics at The Ethics Centre.

The ethical price of political solidarity

The ethical price of political solidarity

Opinion + AnalysisPolitics + Human Rights

BY Tim Dean 3 JUL 2024

Which takes ethical precedence: keeping a promise to remain loyal to your group or sticking to your principles?

This is a question that has faced first-term Western Australian senator, Fatima Payman, repeatedly over the past few weeks. Ultimately, she chose her principles, crossing the floor to vote for a Greens bill calling to recognise Palestinian statehood, and now she’s paying the price for breaking her pledge of caucus solidarity with the Australian Labor Party (ALP).

Meanwhile, Prime Minister Anthony Albanese, faced a different dilemma. Even though his party’s National Platform ostensibly supported Payman’s principled position, the fact remains that she broke caucus solidarity by crossing the floor, an act that he was obliged by party rules to punish with a one-week suspension from caucus.

But then Payman doubled down on her principled stance by stating on national television that she would be willing to cross the floor again should another vote arise on Palestinian statehood. Again, Albanese felt his hand was forced, with him issuing her with an indefinite suspension.

Payman’s suspension has proven divisive, with many Labor members and supporters expressing outrage that she would violate her sacred pledge of caucus solidarity and draw media attention away from key Labor initiatives, such as the revised stage 3 tax cuts.

Others, such as the Australia Palestine Advocacy Network, have seen events through a different lens, saying it was “disturbed by the suggestion that towing the Labor Party’s line is more important than standing up for the rights and lives of Palestinians as they are slaughtered in Gaza.”

Ultimately, both Payman and Albanese were placed in an ethical dilemma, with competing obligations pulling them in different directions. However, the episode raises deeper questions about whether politicians should be allowed to vote on matters of conscience or principle, and whether it is justified for a political party to punish them for doing so.

Ethical tension

When we vote for a politician based on their stated values and principles, we might expect they stand by them and vote accordingly when they’re in parliament. However, that’s often not the case.

Members of parliament are typically bound to vote for – and publicly support – their party’s agreed position, even if that position contradicts their own. In fact, since its inception in 1891, Labor has maintained a strict policy of caucus solidarity, with members pledging to uphold it as sacrosanct.

This means Labor members are free to argue forcefully for their views inside caucus meetings, but once the caucus has decided on a position, they are bound to vote for it. This has sometimes put Labor members in a difficult position, such as when Labor Senator Penny Wong was obliged to vote against same-sex marriage in 2008, despite her deep commitment to marriage equality.

In keeping with its traditional liberal roots, and the notion that it’s a “broad church”, the Liberal Party takes a relatively softer stance, ostensibly allowing members to cross the floor on matters of principle. However, even though the Liberal Party doesn’t require its members to make a pledge of caucus solidarity, they are still strongly encouraged to vote with the party, and often suffer punishment if they go against the party line.

The exception is when the leadership of a political party announces a “free” or “conscience” vote. These are rare, and are typically related to bills with a strong ethical element, such as abortion, euthanasia or embryonic stem cell research. In these cases, members are released from their obligations to vote with the party. However, over the last few decades the ALP has been less likely to allow a conscience vote than the Liberal Party, and the bill on Palestinian statehood that Payman crossed the floor on was not declared as a conscience vote by Labor.

Caucus solidarity is often justified in terms of the party being more stable – and more effective in governing – if it works as a collective rather than a group of individuals with diverse views. If every member of parliament were free to vote on any issue, then parties would have to work harder to curry favour with each representative, possibly watering down bills in order to get them on board. That could result in weaker legislation and prevent a party from genuinely being able to enact the policy platform that it presented to the electorate. It would also make it harder to vote for a party platform, knowing that any member might vote against it at any time.

Still, party solidarity could be seen as a political solution that involves an ethical compromise, not only preventing politicians from voting according to their deeply held views – which might be the very views that got them elected – but also requiring them to act inauthentically by publicly supporting a view they don’t personally hold.

Ultimately, political leaders – Anthony Albanese included – have a choice to make when faced with the dilemma of a sitting member crossing the floor: which is more important, solidarity or principle? And voters have a choice of whether to vote for a candidate, knowing that they might be prevented from voting in accordance with their values and principles.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

To Russia, without love: Are sanctions ethical?

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights

Vaccination guidelines for businesses

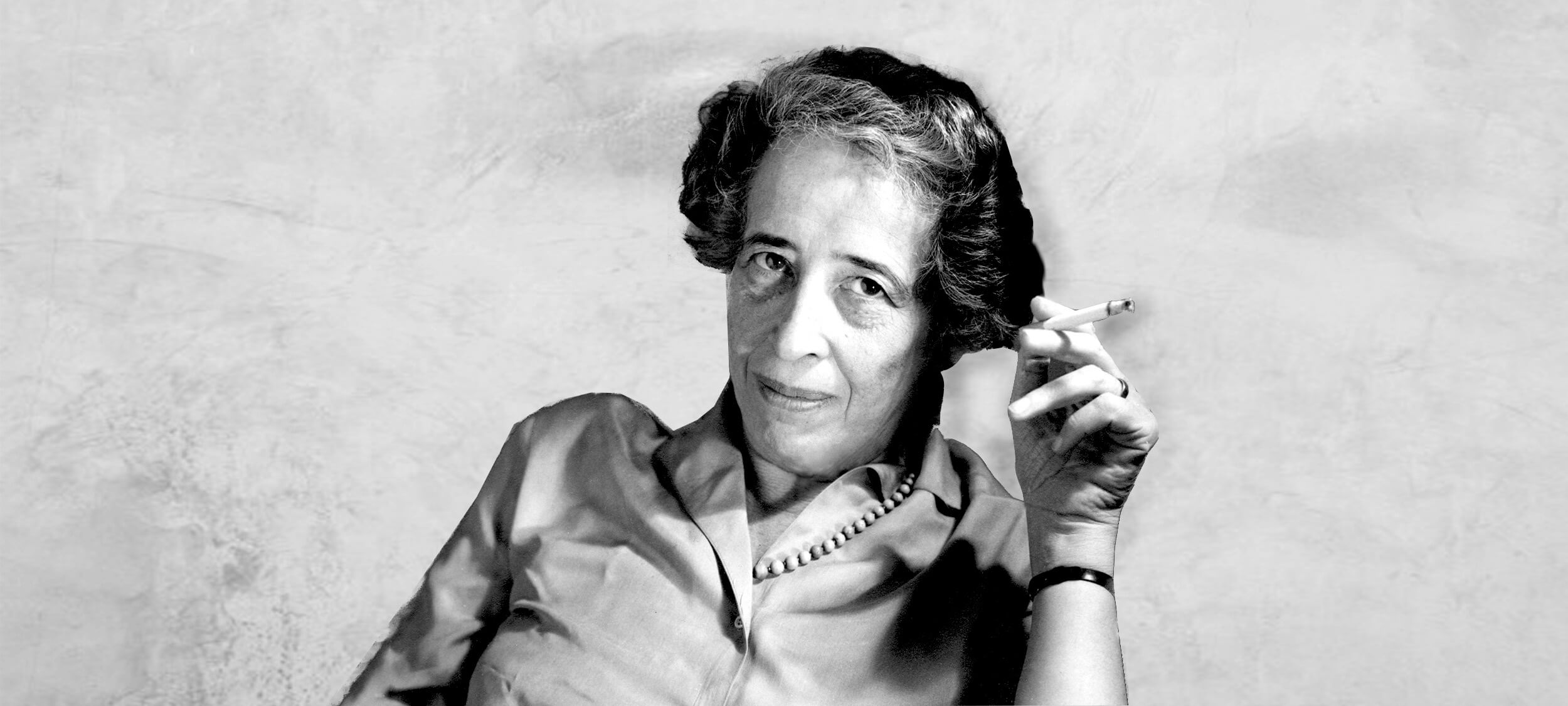

Big thinker

Politics + Human Rights

Big Thinker: Hannah Arendt

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights

Who’s afraid of the strongman?

BY Tim Dean

Dr Tim Dean is a public philosopher, speaker and writer. He is Philosopher in Residence and Manos Chair in Ethics at The Ethics Centre.

The limits of ethical protest on university campuses

The limits of ethical protest on university campuses

Opinion + AnalysisPolitics + Human Rights

BY Tim Dean 14 MAY 2024

Ethical protest is a crucial element of liberal democracy. But protesters and universities must tread a fine line to allow good faith expression while preventing unethical forms of speech.

In parallel to the conflict raging in Gaza, another front has emerged in the form of pro-Palestine protest camps at universities across the United States and Australia.

The protesters have called for a ceasefire in Gaza and for their host universities to sever any connections with defence companies that support Israel’s war effort, including divestment of stock in any companies with ties to Israel. Meanwhile, Jewish lobbies have claimed that the protests are stoking antisemitism and compromising the safety of Jewish students.

In the US, these camps have triggered a significant, and occasionally violent, backlash from authorities. Both Columbia University and the University of California, Los Angeles have called in police and riot squads to break them up, leading to hundreds of arrests. Australian campuses have so far refrained from such a forceful response, but there are increasing calls from some voices, to close them down.

How should universities and other authorities respond to these protests? What kinds of protest are deemed acceptable? Which cross the line and should be shut down?

Ethical protest

Every citizen of a liberal democracy has the right to protest against injustice. But protesters and authorities must tread a fine line between allowing justified forms of expression while preventing forms that incite, dehumanise, vilify or cause undue disruption or damage to private or public property.

But what counts as incitement when slogans are interpreted in different ways by different people? What constitutes vilification, when many in the Jewish community perceive criticism of Israel as being antisemitic? Is it undue disruption if a camp prevents uninvolved students from attending their classes? Can a protest movement prevent fringe elements from coopting it to promote extreme views or violence?

These are difficult questions to answer for both protesters and universities. However, a better understanding of the limits of ethical protest can guide those running the camps to ensure they remain within the bounds of what is justifiable speech, and authorities, so they don’t end up suppressing legitimate forms of expression.

In good faith

A crucial feature of ethical protest is that protesters are acting in good faith, which means they are acting with the intention to call out what they genuinely believe to be an injustice.

This means the protesters need to have just cause, and ensure their expression doesn’t stray outside of this justification. In the case of the pro-Palestine camps, there are arguments that can provide just cause, including statements of concern from the United Nations, governments and other world leaders about the impact that the conflict is having on innocent civilians and the lasting damage to infrastructure that could harm future generations of Palestinians who played no part in Hamas’s terrorist attacks of October 2023.

However, there have been some pro-Palestine protesters who have stepped outside of bounds of this just cause, such as threatening Jewish students or saying Hamas deserves “unconditional support”.

A major challenge for the pro-Palestine camps is to keep emotions, especially outrage, in check. This is because justifiable outrage and heated emotion against injustice can easily tip over into calls for unjustified retribution against the perceived wrongdoers. While protesters may not intend to carry out any hyperbolic threats they express verbally, they can still service to threaten, intimidate and dehumanise. A sense of solidarity with one’s cause can also lead people to refrain from criticising problematic views or actors within their own “tribe” for fear of appearing disloyal.

Universities and other authorities are right to clamp down on any individuals who engage in such bad faith forms of expression. However, if protest leaders clearly demonstrate that they repudiate violence and dehumanising claims, and actively police their own ranks, then the universities ought to draw a distinction between the protest movement as a whole and individuals who overstep the line.

Interpretation

Bad faith expression is complicated by ambiguous slogans, such as “intifada” or “from the river to the sea”. Many people interpret the former as a call for resistance, while others associate it with the Palestinian uprisings starting in the 1980s. And some interpret the latter slogan as a call for peace within the region while others hear it as a call for the elimination of the Israeli state.

It is inevitable that symbols will be interpreted in different ways, and it is impossible to ensure that a symbol will only have one meaning. It’s also impossible to prevent fringe elements from appropriating a symbol and potentially tainting its meaning.

However, protest organisers can be clear about the intended meaning of symbols, promote good faith interpretations and suppress their use when they overstep into representing a clear threat to others. People perceiving the symbol should also exercise charity in their interpretation, rather than assuming the worst possible interpretation. Only in clear cases where the symbol is being used consistently in a bad faith manner should authorities step in to suppress its use.

Language matters

Language that is critical of the Israeli government has also been interpreted by some as being inherently antisemitic, and often such criticism has been laced with antisemitic sentiment. However, it is possible in principle to be critical of the Israeli government and its policies without being antisemitic. Were that not the case, then a significant proportion of the Jewish population of Israel would itself be deemed antisemitic due to its strong opposition to the current government’s policies. It is also possible to condemn terrorism and Hamas’ October 7 2023 attacks against civilians and also condemn the scale of collateral damage in Gaza as a result of the Israeli offensive.

It is important for those critical of the Israeli government to be clear in their use of language to not imply any antisemitic sentiment, just as it is important for those listening to exercise charity in how they interpret such statements.

Disruption

Many protests cause disruption. Indeed, disruption is sometimes a means to draw attention to an issue that might be otherwise overlooked by the public. However, ethical protest requires that the organisers minimise their impact on bystanders, especially those who are not responsible for the injustice being protested.

If the disruption becomes disproportionate, or it tips over into serious property damage, then authorities can be justified in placing restrictions on the protest and prosecuting any individuals who are involved in damaging acts. However, authorities must be very careful in how they do so, as targeting the entire protest can end up suppressing legitimate speech and can also backfire, causing more disruption or damage.

More space for protest, not less

Often the most prudent response to a protest is for universities to give the protesters more space for expression, not less. Despite the demands issued by many protesters, one core goal is often simply to be heard and acknowledged. Even if the other demands, such as divestment, are not met, protesters may still feel satisfied if they are given the space and respect to be seen and heard.

If universities give the protesters a platform to express their good faith arguments – and equal space for others to oppose them in good faith – and they can manage it safely, then it can take a great deal of pressure off the protest movement, which might otherwise lash out in more destructive ways.

It is also crucial that the protests do not turn violent. One trigger for such violence is overly forceful policing, as we have seen in the United States. By increasing the pressure on protesters, especially if that pressure is exerted by police, who are trained to use force when necessary to achieve their objectives, then protesters can lash out or act in self-defence. This can, in turn, motivate an even more forceful crackdown, leading to a spiral that can end in violence or riots. Better to take the pressure off and give the protesters the space to act peacefully and in good faith rather than set their backs against the wall.

It is impossible to guarantee that any protest will unfold entirely without cost or error. But as long as the protesters are acting in good faith, with just cause, and if they police their own members to prevent unethical behaviour, then universities ought to give the protesters the space to do so peacefully and with minimal impact.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights

Could a virus cure our politics?

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships, Society + Culture

Punching up: Who does it serve?

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Want #MeToo to serve justice? Use it responsibly.

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

The erosion of public trust

BY Tim Dean

Dr Tim Dean is a public philosopher, speaker and writer. He is Philosopher in Residence and Manos Chair in Ethics at The Ethics Centre.

Trying to make sense of senseless acts of violence is a natural response – but not always the best one

Trying to make sense of senseless acts of violence is a natural response – but not always the best one

Opinion + AnalysisSociety + Culture

BY Tim Dean 17 APR 2024

Shock reverberated throughout Australia at the news of a frenzied knife attack in Sydney at Westfield Bondi Junction on 13 April — an attack that claimed the lives of six people and injured many more.

Naturally, such an event triggers a surge of news reporting and social media posts. But the news and social media conversation quickly pivoted from reporting the facts of the event to seeking answers. How could such a horrifying thing happen? What could drive someone to do something like this? Could it happen again? Could it happen near me? Am I safe?

Our minds naturally recoil from violence. But they recoil just as much from the prospect that violence can be random or senseless. We have a deep and abiding need to make sense of such horrors, to place them within a causal narrative that can help us understand how they fit in to the world around us. But in our search for a narrative, we can easily latch on to something convenient, whether or not it’s true.

Violence in search of a reason

For many people — particularly those on social media — the first narrative they turned to was terrorism. It’s not that they necessarily wanted it to be an act of terrorism. But terrorism is something that we all, sadly, understand only too well. By labelling the attack as “terrorism”, the attack ceases being random and becomes part of a system we can comprehend.

So, many people may have felt a slight sense of unease when the New South Wales police commissioner declared that it was not an act of terrorism. If not terrorism, what was it? What could possibly motivate such a horrific attack?

Then it emerged that the attacker targeted more women than men. So perhaps it was misogyny that motivated him? Perhaps he was one of these “incels” (or involuntary celibates) we sometimes hear about? But again, the details were unclear, so the speculation continued.

When the attacker’s mental health issues were revealed, that offered another way to make sense of the violence. People could draw on a well-known narrative of a broader mental health crisis across the nation. And while that might inspire greater attention and investment in mental health, it can also instil fear and suspicion of those who experience a range of conditions but pose no threat to the public, possibly leading to increased stigma or disadvantage.

And, of course, there’s the fact the attacker used a knife, which will inevitably lead to a conversation about whether we ought to regulate the sale of knives, even if that might hamper legitimate use and have done little to prevent this attack.

How to live with the uncertainty

Yet we must remember that it remains a distinct possibility this was a freak event, one that doesn’t fit into any clear causal narrative, and one that doesn’t tell us anything meaningful about whether such horrific attacks are likely to occur again in the future. It might be the case that there was little or nothing that could have been done to prevent it. Ultimately, it might just be a random and senseless act of violence, no matter how much our minds recoil from such a possibility.

It’s natural for us to seek meaning when we’re faced with apparently senseless violence, even if it can cause us to jump to conclusions or latch on to hasty solutions. What’s less natural is sitting with the uncertainty that comes with not knowing how or why this happened.

So, what to do?

First, we should forgive ourselves (and everybody else) for being human, and desperately wanting to live in a safe and predictable world. But second, we need to acknowledge that safety and predictability are often outside of our control. Even so, it doesn’t mean we are powerless. As the Stoics pointed out, we can still choose how to encounter the world, and likewise, which narratives to adopt to make sense of it.

Instead of focusing on the motivations of the attacker, which might always remain elusive, we can look to other parts of the picture, including those that reinforce our appreciation of our fellow humanity, even in the face of unspeakable tragedy. We can focus on the acts of heroism by individuals to hold back the attacker. Or on the bravery of the police officer who confronted him. Or the workers who hastened to protect the customers in their stores. Or the outpouring of support from the community to the victims and their families.

There is a strong narrative here, one that can boost our empathy for others and buttress us against tragedy, whether deliberate or random. But it might require us to allow some questions to go unanswered.

This article was originally published in ABC Religion and Ethics.

Image by Richard Milnes / Alamy

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Big thinker

Relationships, Society + Culture

Five Australian female thinkers who have impacted our world

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

Violence and technology: a shared fate

Opinion + Analysis

Science + Technology, Business + Leadership, Society + Culture

AI might pose a risk to humanity, but it could also transform it

Opinion + Analysis, READ

Society + Culture