Exercising your moral muscle

Exercising your moral muscle

Opinion + AnalysisHealth + WellbeingRelationships

BY The Ethics Centre 8 SEP 2021

Day-to-day decisions carry more weight in the context of the pandemic.

Previously simple choices like whether or not to go to the shops are now shadowed by dire consequences, and the act of constantly weighing up those consequences can lead to ‘moral fatigue’.

“This is the kind of wearing down of a person who is constantly making ethical decisions in conditions of fundamental ambiguity,” Ethics Centre executive director Dr Simon Longstaff recently told the ABC.

“It’s the sense of the weight of your decision that can be the source of the fatigue.”

Much like physical exercise, Dr Longstaff says there are ways to exercise our moral muscle so that it becomes stronger. Our choices matter because of the cumulative effect they have, and if exercised every day, building up moral fitness can also help prevent moral injury and its effect on our mental health.

Here are four ways to exercise your moral muscle and help with decision-making:

- Build a support system of friends and family members around you who are open to the conversation. Nobody can be expected to know exactly what to do in any given situation, but having a support system of peers, friends and family to bounce ideas off and get perspective can be invaluable.

- Is there urgency to the problem? If not, setting it aside for a period of time and going for a walk can help with clarity. “Allowing a bit of time and literally going for a walk is one of the really good things you can do,” Dr Longstaff says. “It’s amazing how much just walking helps things just sort out in your own mind.”

- All muscles need time to recover, so factor in rest days to help manage mental exhaustion and take time to do something you enjoy. “Think creatively about ‘what makes me happy in life? What are the things that I really love doing, that I find relaxing?’,” researcher and psychologist Professor Jolanda Jetten told the ABC. “We know that feeling in control is a very good predictor of good health, physical and mental. People should think of ways they can encounter situations and contexts where they feel fully in control, where they don’t have to worry.”

- If all else fails, or you’re not sure who to talk to, make a booking with the Ethics Centre’s hotline Ethi-call and speak with a qualified counsellor to help shape your perspective and find a pathway that’s right for you.” A service like Ethi-call helps you become really clear about the facts of the matter,” Dr Longstaff says. “Most importantly, what it does is give you the ability to shape your perspective so you can see the problem from different angles, and in that you might open up an option that never occurred to you that resolves the situation.”

Free, independent helpline Ethi-call provides guidance and support to anyone facing a difficult ethical dilemma or decision. Book a call with a qualified counsellor here.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Climate + Environment, Health + Wellbeing, Society + Culture

The five biggest myths of ethical fashion

Opinion + Analysis

Climate + Environment, Relationships, Science + Technology

From NEG to Finkel and the Paris Accord – what’s what in the energy debate

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

The ethics of smacking children

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Science + Technology

Big tech’s Trojan Horse to win your trust

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Violent porn and feminism

Violent porn and feminism

Opinion + AnalysisRelationships

BY Georgia Fagan The Ethics Centre 1 SEP 2021

Does pornography, especially violent pornography, contribute to gender-based violence, and if so, is censorship the answer? Or can the pornographic industry coexist with the drive towards gender equality?

We occupy a world plagued by sexual and gender-based violence. The United Nations declaration on the Elimination of Violence against Women (1993) asserts that such violence need be recognised as “a manifestation of historically unequal power relations between men and women”.

Globally in 2017, 219 women were killed each day by either a member of their own family or by their own intimate partner. Debates about the complex causes of such violence and reasons for the persistence of gender inequality remain. The role that pornography may play in both the maintenance and propagation of these harms is one of many factors considered relevant to the debate. Specifically, ethicists are needed to address the question: Could pornography and feminism be compatible bedfellows after all?

Renowned feminist philosopher Catherine Mackinnon argues that pornography “works as primitive conditioning”, meaning that its content is likely to inform the desires and subsequent actions of its viewers. Mackinnon asserts that if pornographic images are violent, this is likely to result in unwanted sexual violence being inflicted onto others by pornography’s consumers.

Contemporarily, debate and disagreement persist regarding how pornography should be managed for adult audiences.

Various philosophers and feminist theorists, such as Mackinnon, argue in favour of some form of criminal action being taken against certain types of pornography due to its capacity to harm women. In 1983, Mackinnon, alongside feminist writer and activist Andrea Dworkin, brought forward an Antipornography Civil Ordinance which proposed that pornography needs to be treated as a violation of women’s civil rights. The pair aimed to remove the freedom of speech protections pornography had been granted under United States law. The ordinance was ultimately struck down by the courts.

Debate continues as to whether pornography, particularly forms of pornography which depict explicit violence against women, can remain conducive with the feminist project of gender equality.

To this day, feminists remain largely divided over MacKinnon’s antipornography ordinance. Debate continues as to whether pornography, particularly forms of pornography which depict explicit violence against women, can remain conducive with the feminist project of gender equality.

Calls to dismantle the industry of pornography are often taken to be synonymous with feminist action. In such cases, this action is thought to be the best means of protecting women from an industry rife with exploitation. Similarly, calls to cease pornographic productions are often thought to serve the function of preserving women’s dignity by allowing them to avoid careers centred around sexual objectification.

However, demands for censorship or a general production shutdown of pornographic films are also calls to severely limit the career opportunities and subsequently the financial resources of pornographic actresses. Doing so may risk further degrading these workers’ rights. The profitability and questionable legality of the porn industry often permits it to function below industry standard, resulting in inadequate worker protections being extended to porn actors and actresses.

Stoya is a female adult entertainer who has spoken openly about a form of feminism which she worries hates both sex work and pornography. She is concerned that female sexuality is only being embraced within narrow margins, neglecting the possibility that hardcore pornography may empower women, both actresses and viewers, rather than degrade them. Stoya argues that a contemporary feminism which celebrates women’s right to work and earn an independent wage is flawed if it simultaneously rebukes women who freely choose to perform in pornography to acquire that wage. For Stoya, performing in hardcore pornography (produced under fair working conditions) does nothing to degrade the status of female performers. Rather, it stands as a celebration of a tirelessly campaigned for and emancipated female sexuality.

Denying pornographic actresses the rights and representation which permits them to carry out their work safely is an injustice to women which should be feared.

Denying pornographic actresses the rights and representation which permits them to carry out their work safely is an injustice to women which should be feared. Doing so puts these women at increased risk of assault and exploitation out of fear their allegations will not be trusted or that they will meet with legal consequences. Stoya herself brought forward rape charges against famous male pornstar James Deen, and she holds that the remedy to such injustices lies in improving workers’ rights and the legislative systems surrounding the industry of pornography, rather than in trying to shut down the industry altogether.

This lack of regulation constitutes an injustice far greater than the supposed, yet largely unarticulated, harm of women being free to use their naked bodies for profit. The mere existence of agential and passionate hardcore pornographic actresses importantly signals the beginnings of a world where women’s bodies are no longer policed in ways which unjustifiably align sex with shame and exploitation.

So long as the porn industry is made to function on par with other industry’s standards, there is no reason to consider the bodies of female pornographic actresses anymore degraded, or exploited, than non-pornographic actresses, tradespeople, or frontline healthcare workers.

Calls to censor or morally condemn pornography are often less concerned with the rights of pornographic actresses and more with the potentially negative impact pornography has on its consumers. There are concerns, for example, that viewing violent pornography may increase sexual assault rates, a causal link which is yet to be definitively established. However, even if particular depictions of women’s bodies were found to increase the likelihood that men assault women, it is not immediately apparent that the desirable solution would be to forbid those depictions.

This censorship style solution shares particular characteristics with victim blaming culture, in which victims are blamed for the actions of perpetrators. In both victim blaming and pro-censorship anti-porn positions, the onus of change is placed on those who are determined to be the cause of any given injustice. The pornographic actress, for example, is told she cannot continue to do her work, instead of alternative interventions being sought which target perpetrators who may have been inspired by viewing particular pornographic depictions. We do not think it suitable to tell women to wear more clothing to stop men raping them; why should matters of pornography be handled any differently?

There are more desirable, alternative solutions to address contemporary issues of misogyny. First is the formation and endorsement of a safe and responsible pornography industry where the agency and security of actors and actresses is guaranteed. Unfortunately there will always be room for exploitation and abuse, however, these risks can be mitigated by extending workers’ rights and fair working conditions to pornographic actors in the same way such rights are endowed to workers in other industries.

Content subscription service Onlyfans stands as a site moving the pornography industry in this direction by allowing performers greater control over their content and income. OnlyFans allows performers to safely and independently produce pornographic content. However, the platform hasn’t avoided trouble for hosting adult content: Onlyfans recently announced it would be banning explicit content in a bid to attract investors, only to reverse its decision within a week after outcry from users.

Ongoing periphery interventions are also required to address gender-based violence and gender inequality more generally, such as improved sex education curriculums which provide more comprehensive education on consent and respectful relationships to school age children.

Interventions such as bolstering the regulatory bodies surrounding pornography and improving sex-ed curriculums allows societies to place adequate accountability on those who commit or are at risk of committing acts of violence against women. These interventions should be favoured over those which risk undermining the agency of both female performers and consumers of pornography.

Pornography, even violent pornography, need not be incompatible with the feminist project of gender equality.

Pornography, even violent pornography, need not be incompatible with the feminist project of gender equality. Theorists and feminists alike need to engage in critical discourse regarding where the onus of change need be placed. The porn industry, pornographic actresses and perpetrators of violence against women are all potential targets of this change. The decisions we make regarding what actions should be taken will determine whether or not pornography is compatible with contemporary feminism.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

TEC announced as 2018 finalist in Optus My Business Awards

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships, Science + Technology

Periods and vaccines: Teaching women to listen to their bodies

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Standing up against discrimination

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Ask an ethicist: How should I divvy up my estate in my will?

BY Georgia Fagan

Georgia has an academic and professional background in applied ethics, feminism and humanitarian aid. They are currently completing a Masters of Philosophy at the University of Sydney on the topic of gender equality and pragmatic feminist ethics. Georgia also holds a degree in Psychology and undertakes research on cross-cultural feminist initiatives in Bangladeshi refugee camps.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Meet Daniel, helping us take ethics to the next generation

Meet Daniel, helping us take ethics to the next generation

Opinion + AnalysisRelationshipsSociety + Culture

BY The Ethics Centre 23 AUG 2021

At The Ethics Centre, we believe ethics is a collaboration – a conversation between diverse people trying to figure out how to act, live and make good decisions.

This means we need a range of people participating in the conversation, of all ages. Thanks to our donor, Chris Cuffe AO at Third Link Investment Managers, we are excited to share that we have recently appointed Daniel Finlay to Youth Engagement. Daniel is a graduate from the University of Sydney with a Bachelor of Arts and Science (Hons) and a Postgraduate Certificate in Publishing. He also received Class I Honours for his thesis in ethical philosophy. To welcome him on board and introduce him to you, our community, we sat down for a brief get-to-know-you chat.

Tell us, what attracted you to philosophy?

My first philosophy-related class was called Bioethics and I actually took it because I had come back from a break and couldn’t continue my psychology units until the next semester. But from the moment I left the first tutorial, I knew this was where I would end up going. The unit was practical ethics with a focus on humans and their bodies. The topics we covered ranged from black-market organ selling to sex work to people suffering from body integrity identity disorder (BIID). The BIID discussion particularly made me realise how many questions we have to face that simply don’t have neat or obvious answers. BIID is a very rare disorder where a healthy person very strongly desires to amputate one or more of their limbs. And here we were, a group of fresh-faced 19-year-olds, trying to figure out what the hell to do with that information.

That sounds like an interesting place to start. Let’s jump over to COVID and restrictions. How are you dealing with it and what do you hope we’ll be able to bring out the other side?

Honestly, I’m part of the lucky few who haven’t been too flipped around by the lockdowns. I do very much miss rock climbing and have admittedly fallen back into lazy habits without it, but on the whole I can deal with being at home very easily because that’s where I like to spend most of my time regardless.

I’m hoping that we all come out of this with a bit more patience. COVID has obviously slowed a lot of things down for a lot of people. Media content is coming out slower, packages are constantly delayed, work projects put on the back-burner. Hopefully most people come out the other side of this with the realisation that most things aren’t as urgent as they sometimes seem, and a little patience when dealing with fellow humans can go a long way.

With all that time at home, you must have developed some guilty pleasures during the pandemic. Can you share one with us?

I wish I had something quirky or funny to share but the sad reality is my guiltiest pleasure is just watching TikToks at midnight in bed instead of getting a reasonable night’s sleep.

Pretty sure that you aren’t alone there. So, what does a standard day in your life look like?

Mostly playing games, watching Netflix/YouTube and managing an online Discord community I run. At the moment, I’m researching how, when and why young people engage with ethics in their lives and offering a younger perspective on a range of projects. Whenever I find the energy, I do try to make time for reading (I’ve recently gotten back into some fantasy novels), walking, listening to podcasts, rock climbing, writing and annoying my cat, Panda.

Let’s wrap up close to home. What does ethics mean to you and why are you interested in bringing it to the attention of young people?

To me, ethics is about learning to live with ourselves in a way that is sustainable. Part of that process is learning how to question ourselves, other people, systems and structures. It’s about identifying assumptions and patterns in our beliefs and behaviours and learning to discard or modify the unfounded ones.

I’m interested in bringing it to a younger audience because I think studying ethics and critical thinking is such an important part of developing the cognitive resources needed to make significant change in the world in a responsible and empathetic way. I’ve already seen firsthand, from being a Primary Ethics teacher, the immense good that this can do, so if I can help bring these resources into the brains of passionate teenagers then I think the world will be much better off.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Duties of care: How to find balance in the care you give

Opinion + Analysis

Climate + Environment, Relationships, Science + Technology

From NEG to Finkel and the Paris Accord – what’s what in the energy debate

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Scepticism

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Violent porn denies women’s human rights

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Five steps to help you through a difficult decision

Five steps to help you through a difficult decision

Opinion + AnalysisRelationships

BY The Ethics Centre 17 AUG 2021

When big decisions loom, it’s often easy to get stuck ruminating all the possible ways to proceed, how it might go wrong, or get confused by taking on too much external advice and input.

Of all the ways you might act, which is the best? Which of all the possibilities should you choose?

Putting ethics at the centre of your thinking can help. It offers a framework for evaluating life’s difficult decisions, which invariably involve questions about what’s good and what’s right.

These five steps can help you move toward a solution that is in alignment with your purpose, values and principles.

1. Check in with your body

Take a moment to drop into your body. Often, we rush headlong into considering without pausing to reflect on how we feel. Our emotions play a major role in our decisions – both consciously and unconsciously. Stop for a moment and pay attention to your feelings; what are they telling you about what matters most?

You may not unlock immediate clarity, and that’s ok. Just begin by recognising and labelling the emotions that arise. Often these feelings are a compass pointing you to what matters most to you.

2. Question your assumptions and identify the facts.

Often when we feel uncertain, it’s because we are lacking information that is required to make a considered decision. What do you know about the choice in front of you? Write down all the facts that you know about your options.

Now test your thinking. Is there anything you are assuming to be true that may not be? Bracket fears or other people’s opinions for a moment and just focus on what you know to b be true. Be aware of jumping to any conclusions around the circumstance, people involved or potential outcomes.

By looking at the situation more objectively, you can identify what you actually know, and what you need to know. Now ask yourself: do you have all the facts and information that you need to make an informed decision? If there are gaps, write a list of the questions you need answers to, and seek the information that you need to have more factual data to consider.

3. Consider how the options relate to your values.

It’s time to get clear on what matters most to you. That is the key to unlocking your values. Our values are like signposts, they indicate what’s most important to us. It can help to consider the situation through the lens of what you consider most ethically relevant, starting with values that matter most to you such as honesty, transparency, kindness, or integrity. Your values also reflect what you stand for, desire or seek to protect, such as financial security, freedom, creativity, family or community for example.

4. What are the lines you won’t cross?

Next, bring into consideration your principles. If values are the signposts, then principles are the guide rails that keep us on track. They apply to the pursuit of many different types of goals and help when values conflict with one another. Principles can’t be selectively applied. Once adopted, they apply to every decision.

You may value success but not lying or cheating is a solid principle to guide how you achieve success.

You might have just a handful of principles that you personally live by. Check in to make sure that the decision you make doesn’t cause you to cross any of those guide rails.

5. Decide on what matters, and why.

Unpack all of the reasons you might decide in each way and with all of the information on the table – rule out any option that moves you away from your purpose, values and principles, and ultimately, seek out the decision that best aligns with them.

Decision-making is complex at the best of times. But sometimes life can present us with a choice where there is no right option – or where both pathways are wrong. When those moments strike it can feel impossible to find a pathway forward.

You don’t have to navigate it alone. Ethi-call is a free helpline designed to provide structured support and guidance through those very difficult decisions.

Appointments are with trained ethics counsellors who take you through a series of questions that will help clarify the situation and shine a light on what is most important to you.

Make a booking at www.ethi-call.com.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships, Society + Culture

Of what does the machine dream? The Wire and collectivism

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Male suicide is a global health issue in need of understanding

Opinion + Analysis

Climate + Environment, Relationships

Care is a relationship: Exploring climate distress and what it means for place, self and community

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships

The role of the ethical leader in an accelerating world

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Three ways philosophy can help you decide what to do

Three ways philosophy can help you decide what to do

Opinion + AnalysisRelationships

BY The Ethics Centre 29 JUN 2021

Decisions are a part of being human. But that doesn’t mean they are easy.

Whether big or small, when a choice creates an ethical conflict, or where no option feels right, the path forward can seem out of sight.

These three philosophical concepts are designed to help deliver clarity in complexity. Next time you find yourself facing a dilemma, try running it through each of these to shed new light on the scenario.

The Golden Mean

When you’re trying to work out what the virtuous thing to do in a particular situation is, look to what lies in the middle between two extreme forms of behaviour (the middle being the mean). The mean will be the virtue, and the extremes at either end, vices. One end will usually be an excess, the other end a deficiency.

For example, in a situation that requires courage, there may be one extreme where you might act recklessly, and the other, do nothing out of cowardice. The virtuous response is the mean between these two.

The Sunlight Test

This test a simple way to test an ethical decision before you act on it. Ask yourself: ‘Would I do the same thing if I knew my actions would end up on the front page of the newspaper tomorrow?’

By imagining if your decision – and the reasons you made it – were public knowledge, we must consider our willingness to stand by that choice in a public forum.

Would you be proud of the action if people you most admire knew what you’d done and why? Would you be able to defend your choice? Would other people agree, or at least understand, why you did what you did?

This simple thought exercise helps give clarity on your motivations – so you can see clearer whether the choice is motivated by what is good or right, or by self-interest, reward, external pressures or opinions.

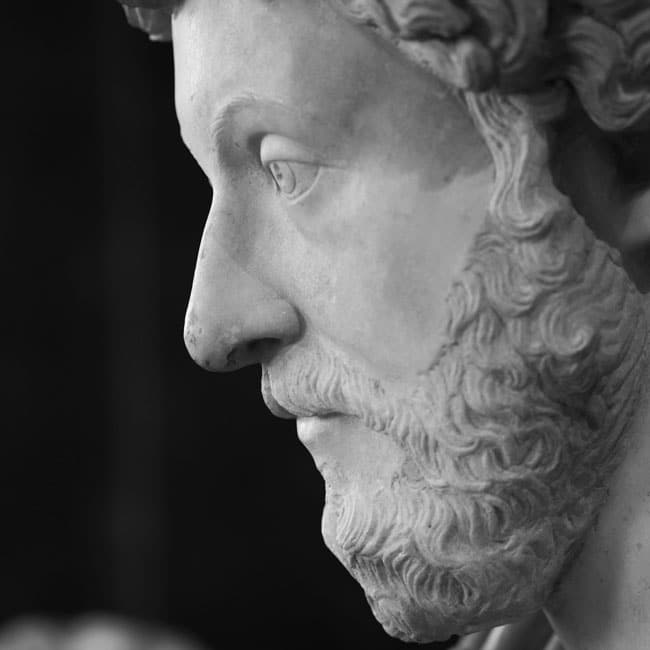

Plato’s Cave

One well known thought experiment is Plato’s allegory of the cave. It goes like this. Prisoners are chained up facing a wall deep within a cave. A fire behind them casts just enough light for them to see images upon the wall, which have been cast by puppeteers. Knowing no alternative, the prisoners believe what they see and hear to be the whole reality.

As the Philosopher John Locke said, “No man’s knowledge here can go beyond his experience”. When faced with a decision, consider the day-to-day experiences, lessons, conversations and modelled behaviour that is shaping what you believe to be ‘reality’.

Are shadow puppets (bias) driving your actions? Can you step outside your own projections on the wall to consider new perspectives and ideas? Can you separate truth from fiction? By challenging the things you believe to be true in any scenario you can make sure that your assumptions hold up to scrutiny.

Still stumped: Ask yourself these three questions:

What are your duties and responsibilities in this situation and to whom?

What counts as a good outcome and how will you know?

What would the wisest person you know say to do in this situation?

Ethi-call is a free helpline designed to provide structured guidance through life’s most challenging dilemmas. If you, or a loved one are facing a decision that leaves you with a bad feeling and no right way out, a conversation can help.

Appointments are with trained ethics counsellors who take you through a framework of prompts and questions that will help clarify the situation and shine a light on what is most important to you.

Make a booking at www.ethi-call.com.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Science + Technology

Injecting artificial intelligence with human empathy

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Love and morality

Explainer

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Gender

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

How to give your new year’s resolutions more meaning

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

The role of emotions in ethics according to six big thinkers

The role of emotions in ethics according to six big thinkers

Opinion + AnalysisRelationships

BY The Ethics Centre 16 APR 2021

It’s not easy to provide a clear definition of emotions. Philosophers and psychologists still haven’t agreed on what they are or whether they’re ethically important.

Most of us have lots of emotions and can name a dozen off the top of our heads pretty quickly. But there’s a lot more to understand. Why do they matter? Are we in control of our emotions? Should we prioritise our reason over our emotion?

Let’s take a look at what philosophy has to say.

Plato: reason rules emotion

For Ancient Greek philosopher Plato, emotion was a core part of our mind. But although it was core, he didn’t think emotions were very useful. He suggested we imagine our mind like a chariot with two horses. One horse is noble and cooperative, the other is wild and uncontrollable.

Plato thought the chariot rider was our reason and the two horses were different kinds of emotions. The noble horse represents our ‘moral emotions’ like righteous anger or empathy. The cranky horse represents more basic passions like rage, lust and hunger. Plato’s ideas set the precedent for Western philosophy in placing reason above and in control of our emotions.

Aristotle: what you feel says something about you

Aristotle had similar ideas and believed the wise, virtuous person would feel the right emotions at the right times. They would be depressed by sad things and angered by injustice. He also believed this appropriate kind of feeling was an important measure of whether you were a good person. He didn’t think you could separate the kind of person you were from the way you felt.

So if you find it funny when someone slips over in a puddle, Aristotle would argue that says something about you. It doesn’t matter whether you then offer them a towel or ask if they’re okay. The amusement you felt in response to their suffering reflects your character. He thought your job is to work hard so instead of laughing at such situations, you feel empathy and concern.

Hume: emotion rules reason

Scottish philosopher David Hume thought this view was naive. He famously said reason is “the slave of the passions”. By this he meant our emotions lead our reason – we never choose to do anything because reason tells us to. We do it because an emotion pushes us to act. For Hume, reason isn’t the charioteer driving our emotions, it’s more like the wagon being pulled along with no control over where it’s headed. It’s the horses – our emotions – calling the shots.

Hume and his friend Adam Smith developed a theory of moral sentiments that used emotion as the basis for their ethical theory. For them, we act virtuously not because our reason tells us it’s the right thing to do, but because doing the right thing feels good. We get a kind of ‘moral pleasure’ from acting well.

Kant: emotion strips our agency

Immanuel Kant thought this whole approach was entirely wrongheaded. He believed emotion had no place in our ethical thinking. For Kant, emotions were pathological – a disease on our thinking. Because we have no control over our emotions, Kant thought allowing them to govern our thinking and action made us ‘automated’, and that it is the only reason that made us autonomous and capable of making truly free decisions.

Freud: our unconscious drives us

More recent ideas have questioned whether there is such a thing as ‘pure reason’ (a concept Kant named one of his books after). Psychoanalysts like Sigmund Freud encouraged us to see our motivations as driven by unconscious urges and inclinations. More recent work in neuroscience has revealed the role unconscious bias and heuristics play in our beliefs, thinking and decisions.

This might make us wonder whether the idea that reason and emotion are two separate, rival forces is accurate. Another mode of thinking suggests our emotions are part of our reason. They express our judgements about how the world is and how we’d like it to be. Are we passive victims of our emotions? Do we spontaneously ‘explode’ with anger? Or is it something we choose? Our answer will help us determine how we feel about things like ‘crimes of passions’, impulsive decisions and how responsible we are for the feelings of other people.

Carol Gilligan: What is this sexist nonsense?

You may have noticed that all the names on this list so far are men. For psychologist Carol Gilligan, that’s not a coincidence. In her influential work In a Different Voice: Psychological Theory and Women’s Development, Gilligan argued that the widespread suspicion of ethical decisions made on the basis of emotion, concern for other people and a desire to maintain relationships was sexist. Most theorists had argued that reason, not emotion, should drive our decisions. Gilligan pointed out that most of the ‘bad’ ways of making decisions (like showing care for certain people or using emotion as a guide) tended to be the ways women reasoned about moral problems. Instead, she argued that a tendency to pay mind to emotions, value care and connection and prioritise relationships were different modes of moral reasoning; not suboptimal ones.

For a long time, reason and emotion have been pitted against one another. Today, we’re starting to understand that, in many ways, emotions and reason are the same. Our emotions are judgements about the world. Our reasoning is informed by our mood, our environment and a range of other factors. Perhaps the question shouldn’t be “should we listen to our emotions?” but instead “how do we develop the right emotional responses at the right time?” That way, we can rely on our emotions as one of many pieces of information we can use to make better decisions.

Follow The Ethics Centre on Twitter, Facebook, Instagram and LinkedIn.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

The etiquette of gift giving

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

Inside The Mind Of FODI Festival Director Danielle Harvey

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

The new normal: The ethical equivalence of cisgender and transgender identities

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships, Society + Culture

Renewing the culture of cricket

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Are there limits to forgiveness?

There is a moment of gut-wrenching horror in Simon Wiesenthal’s The Sunflower: On the Possibilities and Limits of Forgiveness.

It begins with Wiesenthal, a Holocaust survivor, at the bedside of a fatally wounded German soldier.

“I am resigned to dying soon,” the soldier said to him. “But before that I want to talk about an experience which is torturing me. Otherwise, I cannot die in peace.” Comforted by Wiesenthal’s attention, the soldier began to confess to his role in a barbaric war crime where around two hundred Jewish men, women, and children were marched into a house and burned alive.

“I must tell you of this horrible deed,” cried the soldier. “Tell you because – you are a Jew.”

The soldier begs for the forgiveness that would grant him a peaceful death. His voice quivered, his hand trembled; his exhaustion and remorse were palpable. But Wiesenthal said nothing. He turned and left the soldier without a word.

A day later, he found out the soldier had died, unforgiven.

Perversely cruel as it might seem, the moment haunts Wiesenthal. Was it wrong to withhold forgiveness to the soldier, given he seemed genuinely repentant?

The Sunflower poses an invitation. “Ask yourself a crucial question, ‘what would I have done?’”, Wiestenthal dares the reader.

Wiesenthal tasks philosophers, theologians, psychologists, and genocide survivors with answering the very same question and features their responses throughout the book.

It’s true that many of us will not find ourselves in such a harrowing situation. But some will. Victims of crime can be invited to participate in restorative justice programs where they face the person who has wronged them. One in five Australian women above fifteen years old have been sexually assaulted or threatened – usually by someone they know.

In these cases, a victim may face an ethical dilemma they haven’t chosen. One that feels cruel to subject them to: they must decide whether to grant or withhold forgiveness.

Earning forgiveness

Should we forgive those who have wronged us? What makes someone worthy of forgiveness? Can forgiveness be wrong?

These questions are important for two reasons. First, forgiveness doesn’t always come naturally. At the moment when we’ve been wronged – often severely and traumatically – it’s doubly difficult to meditate on the ethics of forgiveness.

It’s painful, confusing and morally loaded: after all, who wants to be the person who doesn’t forgive when people who do – even when it seems impossible – is held up as a paragon of virtue and humanity?

But second, we need to understand how forgiveness should work because we’re all going to seek forgiveness at some point. We will all wrong someone else at some stage, in big ways or small. If we’ve done some work thinking about how we want to forgive, we’ve got a roadmap to follow when we’re the ones seeking forgiveness.

In Wiesenthal’s case, the genuine remorse shown by the German soldier is what troubles him. He believes the soldier is truly sorry for what he did. Not everyone agrees – was this man remorseful, or was he just scared to die? But whether or not the soldier was remorseful, we tend to agree that remorse matters for forgiveness. If someone is remorseful, we can at least think about forgiving them. If there’s no remorse, it doesn’t seem like a moral challenge to withhold forgiveness.

Genuine remorse

But expressing remorse is hard. It takes more than the non-pologies theologian L. Gregory Jones calls “spinning sorrow”. It involves acknowledging responsibility and wrongdoing. “I’m sorry you were offended” isn’t remorse. It’s performative, and puts the onus on the victim for their own suffering. In short, it says you were offended; I didn’t do anything offensive. Your suffering is on you. That’s not remorse, that’s pig-headedness.

Remorse demands us to understand the full extent of our wrongdoing.

That it was wrong, why it was wrong, and how that wrongdoing has harmed someone else. Which gives us good reason to think that Wiesthenthal’s soldier is not genuinely remorseful.

The horror of the Holocaust depended on the systematic denial of Jewish personhood. They weren’t seen as individuals – people with lives complex, unique, and infinitely valuable. Instead, they were objects to be treated as others saw fit.

By treating Wiesenthal as ‘a Jew’ – a generic placeholder for the actual people the solider murdered – the German soldier is continuing on with the same abhorrent thinking that led to his crimes in the first place. He doesn’t understand the depth of what he did. How can he then apologise in a way that warrants forgiveness?

The politics of forgiveness

To step away from Wiesenthal’s case for a second, how often do we witness apologies that fail to show any awareness of the source of the wrongdoing? On a political level, we see apologies offered by those who continue to benefit from those injustices. Does this constitute remorse, or a genuine understanding of the wrongdoing?

Take political apologies, for instance: some naysayers to Australia’s National Apology to the Stolen Generations argued that the people apologising weren’t the ones who had done anything wrong. The claim here is if we haven’t done anything wrong, we don’t need to be forgiven; and if we don’t need to be forgiven, why would we apologise?

This perhaps misses an important consideration.

If we continue to benefit from a past wrong and fail to address the source of the continued disadvantage, there is a sense in which we’ve prolonged the wrongdoing.

However, it also calls our attention to the role of status in forgiveness. I cannot offer an apology for a wrong I haven’t been involved in.

Equally, I cannot forgive unless I have been wronged, which also complicates the politics of forgiveness: who has the moral authority to forgive? Could Wiesthenthal, who was treated as a ‘generic Jew’ by the soldier, actually forgive – even if he wanted to? After all, the soldier’s crimes did not directly harm him.

Eva Kor was a Holocaust survivor who offered forgiveness to Josef Mengele, doctor of the notorious ‘twin experiments’ in Auschwitz. Her actions brought criticism from other survivors, who said Kor wasn’t entitled to offer forgiveness on behalf of others. Nor should she pressure them to forgive when they were not ready.

Jona Laks, another ‘Mengele twin’, refused to forgive. In Mengele’s case, this is understandable. But what if there was genuine remorse, a commitment to change, and steps to address the wrongdoing? Would it be wrong to refuse forgiveness?

On some occasions, it seems so. For instance, we consider pettiness – when someone is unable to move past very slight or non-existent wrongs – as a vice, or a mark of bad character. I’m not suggesting a Holocaust survivor (or any Jewish person) who refused to forgive the Nazis under any condition was being petty, but this takes us back to the question posed earlier.

Is there anything that’s unforgiveable?

This brings us to the final question: are there some things which are unforgiveable? How should we think about them?

Maybe. Philosopher, Hannah Arendt believed that unforgiveable crimes were those where no punishment could be given that would be proportionate to the crime itself. Where no atonement is possible, no forgiveness is possible. For Arendt, these crimes are an evil beyond redemption.

In contrast, French philosopher Jacques Derrida argued that conditional forgiveness is in fact, not forgiveness. By withholding forgiveness until considerations (like remorse) are met, Derrida believed that we are forgiving someone who is already innocent – that is, someone who no longer needs forgiveness. Only the unremorseful person remains guilty, and only the unremorseful person actually needs forgiveness.

As a result, Derrida concludes with a paradox: only the unforgiveable can be truly forgiven.

Derrida traces his thinking back to religious traditions where forgiveness is unconditional and uneconomic. It is a gift, not a transaction. This is a view L. Gregory Jones believes is centrally important to avoid “weaponising forgiveness”.

I think it’s important to remember that forgiveness should always be a gift and not an expectation. It’s unfair to expect any person who has been victimized, especially if it’s raw, to be ready to forgive.

And — this is particularly important in domestic violence and other kinds of forgiveness — the expectation of forgiveness is also used as a weapon to punish and perpetuate a cycle. It’s often the case in domestic violence, for example, where the abuser will come and say, “you need to forgive me because you’re a Christian” and the person feels obligated to do that. All that does is perpetuate and intensify the violence rather than remedy it.

So how should we think about Wiesenthal’s case? What would we do? It seems quite evident that he had no duty to forgive this Nazi – and that perhaps he had no right to do so. However, if we set aside the question of legitimacy, how might he make this decision?

Some philosophers have argued that self-respect is central to the way we think about forgiveness. Forgiveness involves a recognition that we have value – that we did not deserve to be wronged, and the other person should not have wronged us.

By forgiving, we assert our status in the moral community – our dignity.

However, others might believe such forgiveness reduces their self-worth – especially if this forgiveness leaves the wrongdoer better off than the victim. Forgiveness can grant peace to wrongdoers – as the German soldier knew – but often leaves the victim alone in their trauma.

Author Susan Cheever once wrote that “Being resentful is like taking poison and waiting for the other person to die”. For some, this may be true. For others, forgiving might be like giving someone a drink while you are dying of thirst.

Should Wiesenthal have forgiven the soldier? It might all depend on what he could swallow and still look at himself in the mirror.

It may all come down to what he wanted to see when he looked in the mirror.

Follow The Ethics Centre on Twitter, Facebook, Instagram and LinkedIn.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

The Dark Side of Honour

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Progressivism

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Science + Technology

We are being saturated by knowledge. How much is too much?

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

In defence of platonic romance

BY Matthew Beard

Matt is a moral philosopher with a background in applied and military ethics. In 2016, Matt won the Australasian Association of Philosophy prize for media engagement. Formerly a fellow at The Ethics Centre, Matt is currently host on ABC’s Short & Curly podcast and the Vincent Fairfax Fellowship Program Director.

Treating citizens as customers is a recipe for distrust

Treating citizens as customers is a recipe for distrust

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + LeadershipRelationships

BY Eva Cox 8 DEC 2020

My 1995 ABC Boyer Lectures, ‘A Truly Civil Society’, outlined the ill effects of the then decade-plus political paradigm shift to neoliberalism.

In the years following WW2, governments implemented policy changes to ensure well-functioning societies that delivered social fairness. This was to avoid a repetition of the pre-war rise of dictatorships, such as happened in Germany and Italy where democracies were overthrown by the fascists. Much of this reconstruction included expanding health, education and welfare for communities to balance the existing inequities of market wealth creation.

From the 1980s, the failing USSR and the globalising of finance via petrodollars allowed big business to shift the paradigm to market forces and reduce the scope of governments. The effects were becoming evident while I was writing the Boyer’s in 1995, as neoliberalism was exacerbating the cuts to social goals and public funding. Growing distrust of democracy was also becoming apparent in many countries, including Australia.

Now, twenty-five years of policy shifts later, including a market-created Global Financial Crisis in 2008, these changes continue to have ill-effects on democratic governance and trust. Policies such as unfair distributions of taxes that favour businesses and the better-off have exacerbated this, as has the privatising of public services and public ownership of utilities and institutions. The promise that the private model of competition and wealth creation would create trickle-down wealth failed to eventuate. Nor did we see any sign of the market lowering prices for these services, as is promised by this model. Citizens, redefined now as just customers of what were once public services, have not found the market more efficient or effective.

Prioritising growth and profits over community needs and connections exacerbates distrust of those in power.

Finding jobs becomes more difficult as growth slows, and low wages remain for many of the often-feminised essential services, such as nursing and child care. The new gig-economy has also increased feelings of insecurity. Ergo, it has not been surprising that over the last decades there have been growing feelings amongst many people in democracies, including Australia, that those in power are not to be trusted.

Now that the neoliberal paradigm shift is obviously failing, we need to devise and define alternatives. The failure has created a fertile ground for the increasingly irrational ‘strong men’ leaders to grab power. These strong men undermine the idea of democracy and surge in on a wave of distrust. We now have in Australia, as elsewhere, increasing beliefs that society is unfair, feelings of real anger and despair, and a deep distrust of the political system. It is this unfairness that is the damaging cause of most of our problems.

The range of inequities in our current system include politics and policies that respond mainly to business demands and neglect community needs. The recent budget is a good example, where subsidies were available to incentivise businesses to hire more people, even if there were too few customers. Yet much-needed jobs in community and public spheres were barely mentioned.

We need changes that create a sense of fairness by providing good social and public services. People need to feel that they live in societies where they and their contributions are valued and their voice matters. We are social beings, connected, and need to feel safe and involved.

Assuming wealth inequality is a causal factor fails to recognise the real causes: self-interested economic goals that ignore and exclude the values of fairness and trust that are necessary to create a truly civil society.

The national cabinet’s response to the pandemic, an effective public health collaboration, reminded people what good governance looks like. Consequently, it has improved the levels of voter trust. There are now signs of reversal as the PM reverts to a private sector, economic-led recovery.

Now it’s up to us. We need policies that set social goals, fix environmental damage, and create fairness and long-term well-being. Here are some radical ideas: stop privatising community services and utilities, fix the messy unfair welfare system (perhaps introduce a universal social dividend), engage communities in planning for their needs, reform the tax system so that it’s fairer in the redistribution of resources, pass the Uluru Statement from the Heart. This way, everybody should get a fair go.

Outrageous ideas? Maybe, but replacing greed and self interest with fairness requires optimism and another paradigm shift!

This project is supported by the Copyright Agency’s Cultural Fund.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Managing corporate culture

Big thinker

Health + Wellbeing, Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Big Thinker: Judith Butler

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Israel Folau: appeals to conscience cut both ways

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

The ANZAC day lie

BY Eva Cox

Eva Cox AO is an Adjunct Professor at The Jumbunna Institute of Research, University of Technology Sydney, looking at the problems of Indigenous policies. She has worked as political advisor, market researcher, academic and activist, with a high media profile. She delivered the ABC Boyer Lectures in 1995 on the theme A Truly Civil Society, on the need for trust as our social glue.

Ethics Explainer: Akrasia

If you’ve ever helped a child to master toileting, you’ll know of the moment where your patience and understanding expires.

It’s somewhere between the sixth wet bed and the poo stains on the walls, where you beg, implore the child to explain. “You know how to use the toilet, why don’t you just do it?!”

Well, park that frustration friend, because if the ancient Greek philosopher Aristotle is to be believed, we’re all a bit like that child, smearing shit on the walls despite knowing better. Aristotle believed in something he called akrasia – which is usually translated as ‘weakness of the will’, but I prefer to translate it as ‘incontinence’.

That’s right, Aristotle thought most of us had, at one stage or another, a leaky ethical bladder. We know what’s right and wrong; we know how we should act, and yet we wet ourselves rather than actually doing it.

This happens, according to Aristotle, for two reasons. First, passion. There are times when our emotions, ego, excitement or panic get the better of us, and our reason disappears. This can lead us to violence, cruelty, thoughtlessness or any number of things that we know are wrong. Like a toddler wetting themselves in fear or excitement, our moral restraint and discipline is overwhelmed by the emotion of the moment.

This form of akrasia often feels like being ‘swept up’ in the moment. We suddenly find our fists clenched, we find ourselves unable to swallow a hurtful thought – we are, for all intents and purposes – not in control. However, we’re responsible for our lack of control. According to most scholars who believe akrasia is a thing, we lose control because we haven’t worked hard enough to master ourselves. “I’m sorry I said that, I totally lost control,” is an explanation here – not an excuse.

The second way we can be overwhelmed is weakness. Sometimes we are the child who just doesn’t make it to the bathroom in time and has an accident on the floor. Morally, we know that we should try to minimise carbon emissions and that means we should get out of our pyjamas and walk the five minutes to pick up takeaway. But wouldn’t it be faster, and easier, to drive? Here, it’s clear what should be done. It’s just we don’t have the strength of will to do it.

Akrasia of this kind is different to the ‘heat of the moment’ stuff we discussed above. In this case, the little voice in our heads is nagging at us: ‘you should say something’, ‘you shouldn’t be doing this’, ‘that’s your son’s Easter chocolate Matt, you shouldn’t be eating it’… stuff like that. Here, we’re perfectly aware of our failing and watch ourselves fail, seemingly incapable of doing otherwise.

However, there are some who believe akrasia is actually impossible. They reject outright the idea that someone can know what is right to do and also refuse to do that thing. Here’s how their argument looks:

- Every choice people make is made because they see something good in that action.

- Therefore, nobody willingly chooses to do something bad.

- When people appear to be choosing to do something bad, it is because they think that bad thing is, in some way, good.

- Bad things happen because people are mistaken about what’s good.

The belief behind akrasia is that we can know – really know – what’s good and shit the bed when it comes to actually doing it. But would someone who really understood why we need to speak up against abuses of power ever remain silent? Critics of akrasia think not. They think the reason why someone wouldn’t speak up against a bully is because they’ve decided that in this situation, they momentarily believe that the good of personal safety trumps the good of justice. That is, the source of unethical behaviour is in mistaken beliefs, not in weak character.

However, this kind of reasoning comes close to committing the ‘No True Scotsman’ fallacy. The This fallacy, named is named for the Scottish-themed anecdote used to demonstrate it, is a kind of circular reasoning. Here’s how it looks:

- Claim: All Scots are brave and never flee battle

- Counter-evidence: But MacDougall is a Scot and he fled battle yesterday!

- Denial of evidence: MacDougall isn’t a true True Scots are brave and never flee battle.

The No True Scotsman is a way of shifting the goal posts so counterfactuals can’t actually disprove your claim. They are just reworked to support it further.

Critics of akrasia seem to make a similar claim:

- Claim: People do the wrong thing because they don’t know what’s right

- Counter-evidence: Yesterday I knew I should have returned the wallet I found with the cash still inside, but I took the cash and then returned the wallet

- Denial of evidence: You didn’t truly know that’s what you should have done. Otherwise, you would have done it.

This might seem like an academic dispute. And that’s because it is. But it’s also one that matters. Being able to identify the source of ethical failure is crucial if we’re going to prevent it. If ethical failures are problems of knowing and understanding what is good and why it’s good, then the solution is going to involve a lot of education.

If instead, ethical failures are connected to weakness of the will, then our ethics training needs to look a bit more like toilet training: getting us to identify the cues, knowing what to do ahead of time and having the strength to hold on, even when our will seems like it’s going to give way.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

This isn’t home schooling, it’s crisis schooling

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Should parents tell kids the truth about Santa?

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Ending workplace bullying demands courage

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics explainer: Cultural Pluralism

BY Matthew Beard

Matt is a moral philosopher with a background in applied and military ethics. In 2016, Matt won the Australasian Association of Philosophy prize for media engagement. Formerly a fellow at The Ethics Centre, Matt is currently host on ABC’s Short & Curly podcast and the Vincent Fairfax Fellowship Program Director.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Narcissists aren’t born, they’re made

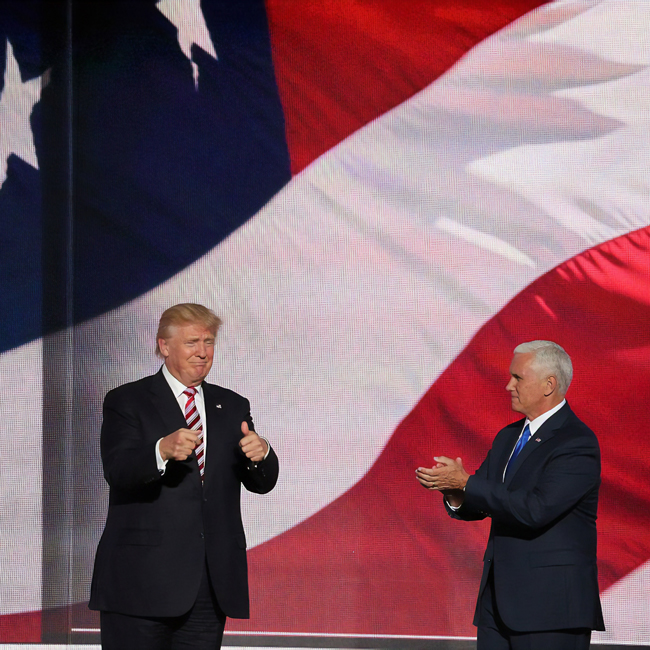

President elect Joe Biden won the recent United States election with 306 electoral college votes to Donald Trump’s 232. Biden also won the popular vote around 80 million to 73 million.

Trump has alleged the election is “rigged” and fraudulent, claims based on no evidence whatsoever, while his legal challenges have been thrown out by one court after another. In an attempted coup d’état, Trump has refused for weeks to concede defeat or to willingly undertake the essential part of the democratic process assisting the transition to the new administration before vacating the White House. It is hard to find a worse example of narcissistic entitlement.

Lack of empathy is at the heart of narcissism too, and there has been a breathtaking callousness in Trump’s indifference to the Covid catastrophe unfolding in the US and his persistent refusal to act. There are more than 12 million Covid cases in the US, among the very highest infection rates per million people in the world. More than a quarter of a million people have died.

On Friday November 20, new cases topped 200,000 in one day and there were more than 2000 deaths, adding to the horrific 250,000 plus death toll. The need for decisive action could not be more urgent. The extreme self-focus, the ‘All About Me’ aspect of narcissism, is evident as Trump plays golf, idly suggests war with Iran, and tweets self-pityingly about being cheated of his “rightful” victory.

One can see the origins of Trump’s narcissism growing up spoiled and overindulged in a wealthy but emotionally harsh and cold family. Donald’s father, Fred Trump, a real estate mogul, would berate him; “Be a Killer not a Loser.” That was the family ethos, the motto. To show kindness, care or admit vulnerability was to be a “loser.” His father not only encouraged Donald in his cruel bullying of siblings but also joined in. Both bear responsibility for the destruction of Donald’s elder brother, Fred Trump junior.

In the Trump family, only making money was valued. Fred was a highly skilled commercial airline pilot who was jeered at as nothing more than a “chauffeur in the sky,” and treated as beneath contempt because his profession did not earn the megabucks that real estate did. Fred was driven to alcoholism, depression, and died early at 42, suicide by drinking. It wasn’t just his toxic family, however, that created the malignant narcissist who refuses to leave the White House.

They call it the “asshole effect.” Stunning new research by the University of California’s Paul Piff shows that wealth increases narcissistic behaviour.

Piff conducted a series of real-life experiments which showed for example, that people driving new model and more expensive cars were 4 times more likely to cut drivers of lower status vehicles off at a crossing. They were three times less likely to yield at a pedestrian crossing. Drivers of the least expensive cars all gave way to pedestrians.

Intrigued by this, Piff did lab experiments and found “the richer the meaner” effect. The richest students were meaner and more likely to consider “stealing or benefiting from things which they were not entitled” than those from lower-class backgrounds. Piff said that “upper-class individuals feel more entitled, are less concerned with the needs of others, and at times were prepared to behave selfishly, even unethically, to get ahead.”

That is deeply concerning in times of mounting inequality. Wealthier people were more likely to agree with statements such as “I honestly just feel more deserving than other people.” They were also vainer, more likely to rush to a mirror and check themselves out if a photograph was being taken. They drew larger circles to represent themselves than they drew to represent other people.

If you think of yourself as bigger and more important than others, it’s not surprising that you have an excessive sense of entitlement and exploit others. They simply don’t matter as much as you do.

Trump is notorious for being cheap and cheating his employees of appropriate payments, as well as ruthlessly getting rid of them once they have passed their use-by date.

Piff’s laboratory experiments revealed that even when poorer people were simply primed to think of themselves as wealthy, this increased feelings of superiority and entitlement, and they began to behave selfishly. When people look down on others, “they tend to acquire the belief that they are better than others, more important and deserving.”

This led to bad behaviour, for example helping themselves to more sweets meant for children in a lab next door, than if they were primed to feel disadvantaged. “That suggests it is more the psychological effects of wealth than the money itself,” Piff said.

Strikingly, Piff found that in unequal societies, higher-income people were richer and meaner – less likely to give money to charity than poorer people – than in more equal societies.

It is not only wealth which can increase narcissistic behaviour. Patriarchal society asserts the superiority of men over women and gives them greater entitlements. Hardly surprising then that research shows that narcissism is higher in men than women. Research also shows that male entitlement and a sense of superiority can have appalling consequences for increased sexual aggression and predation and is a key factor in domestic violence.

Fame increases narcissism and male sexual entitlement, as we can see by the numbers of high-profile powerful men like Harvey Weinstein called out and brought to justice by the Me Too movement. Donald Trump infamously said “I’m automatically attracted to beautiful — I just start kissing them. It’s like a magnet. Just kiss. I don’t even wait. When you’re a star, they let you do it. You can do anything. Grab ’em by the pussy. You can do anything!”

It’s not just rich and famous men who can behave like that. The scandal over a so-called “Triwizard Shorenament,” organised by privileged boys at the elite Sydney private boys school Shore, which charges $30,000 in annual fees, reeked of entitlement. Their plans for Muck Up day were racist, misogynist and cruel; “Spit on a homeless man”, “have sex with a woman over 80 kilograms,” or a woman who “scored” a lowly 3 out of 10 for looks, have sex with “an Asian chick”, and shit on a train.

So what is the answer?

There are clear lessons from the research on narcissism. Anything which leads to a sense of superiority and entitlement is bad news. Hierarchies among human beings based on wealth, race, sexuality or gender need to be challenged. Economic inequality leads to more narcissistic behaviour than exists in more equal societies. In parenting and education, we should beware the narcissistic pitfalls of privilege.

A sense of superiority and entitlement leads to exploitative and even cruel behaviour. If lack of empathy is a core component of narcissism with devastating results, then we need to engage in programs proven to raise empathy in schools. And we desperately need anti-entitlement programs asserting an ethic of care for others, instead of “Me First” as an ideal to live by.

This project is supported by the Copyright Agency’s Cultural Fund.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

If we’re going to build a better world, we need a better kind of ethics

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

We live in an opinion economy, and it’s exhausting

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

If you condemn homosexuals, are you betraying Jesus?

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture, Relationships