A guide to ethical gift giving (without giving to charity)

A guide to ethical gift giving (without giving to charity)

Opinion + AnalysisRelationships

BY Giacomo Bianchino The Ethics Centre 27 NOV 2017

It’s easy to be frustrated by “charity giving” during the festive season. Little Billy gets a card from World Vision thanking him for support he never knew he gave. All because his sanctimonious aunt decided a new bike wasn’t particularly important.

We’d expect Billy to be pretty upset. But is objecting to “charity giving” childish or is donating on a friend’s behalf incompatible with Christmas giving altogether?

Reminding others of their ethical duties at a time of celebration is, in many ways, noble. There is also value for charity gifts as responses to the hollow commercial practices of modern Christmas traditions.

Charity giving overhauls the tradition of giving. It seeks to fulfil a social need without consideration of the putative “receiver”. As such, the moral case for charity giving isn’t black and white.

While the act might be well-intended, it is poorly executed. When we give at Christmas, presents convey a specific message – one that charity gifts miss altogether.

When we give, we create a sense of shared meaning between individuals. The gift establishes a relationship on the basis of common commitment. In the case of Christmas, the commitment is to one another. Different gifting rituals have other messages.

For instance, during Kwanzaa, members of the African diaspora give homemade gifts to encourage one another to remember their heritage. Kwanzaa emphasises the creation of a moral community in which each member is dedicated to the other. Do-it-yourself gifts foster an attitude where the focus is not on the gift itself, but the recipient.

It might seem as though the charity gift does something similar. By doing good in the name of the recipient, perhaps we foster a relationship based on social justice rather than consumption. But there is a difficulty here.

When our gift is a donation for a distant community, we’re no longer giving a gift to our friend or family member. We’re giving a gift to that distant community.

However deserving the community is, this form of giving is radically different to the form inherent to Christmas or Kwanzaa. We effectively cut the receiver out of the process and instead use the gift ceremony as a means to achieving our own moral agenda.

If charity gifts are a problem, can we give in a way that goes beyond the department store notions of giving and escapes the cycle of consumption?

Yes, but the solution doesn’t lie in what we give, but in how we give.

We can take cues from other cultures. There are entire systems of morality built around the idea of the gift. The famous sociologist Marcel Mauss wrote of gift economies in tribal cultures. He learned how members of traditional Samoan communities gain or lose standing based on their ability to give and to receive well. The exchange of property there is more about establishing relationships than obtaining any particular object or achieving any social goal.

This idea of the giving being more important than the gift isn’t foreign to Christmas traditions. The first recorded act of Christmas gifting was Queen Victoria to her children in 1850. You’d have to rack your brain to find something that the kids of imperial royalty needed. Indeed, the gifts they got were purely symbolic, gestures of goodwill.

So if you’re toying with the idea of ethical giving this Christmas, don’t line up the usual suspects. Make donations to your chosen charities in your own name, but avoid treating them as a replacement for gifting. Charity gifts don’t show others what they mean to you, they substitute the gift for some other moral end.

Give some thought instead to the received wisdom of gift cultures.

Begin by asking yourself, “what does this person mean to me?” “How best can I show them?”

If the gift is a way of sending a certain message, focus on the message. The object is just a means of communication – the message lies in the giving.

Become an artist of the gift – creative, thoughtful and mindful of the recipient – and you can give without being smarmy or sanctimonious.

Truly a modern Christmas miracle.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Now is the time to talk about the Voice

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

Meet Dr Tim Dean, our new Senior Philosopher

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Science + Technology

We are being saturated by knowledge. How much is too much?

Explainer, READ

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Altruism

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

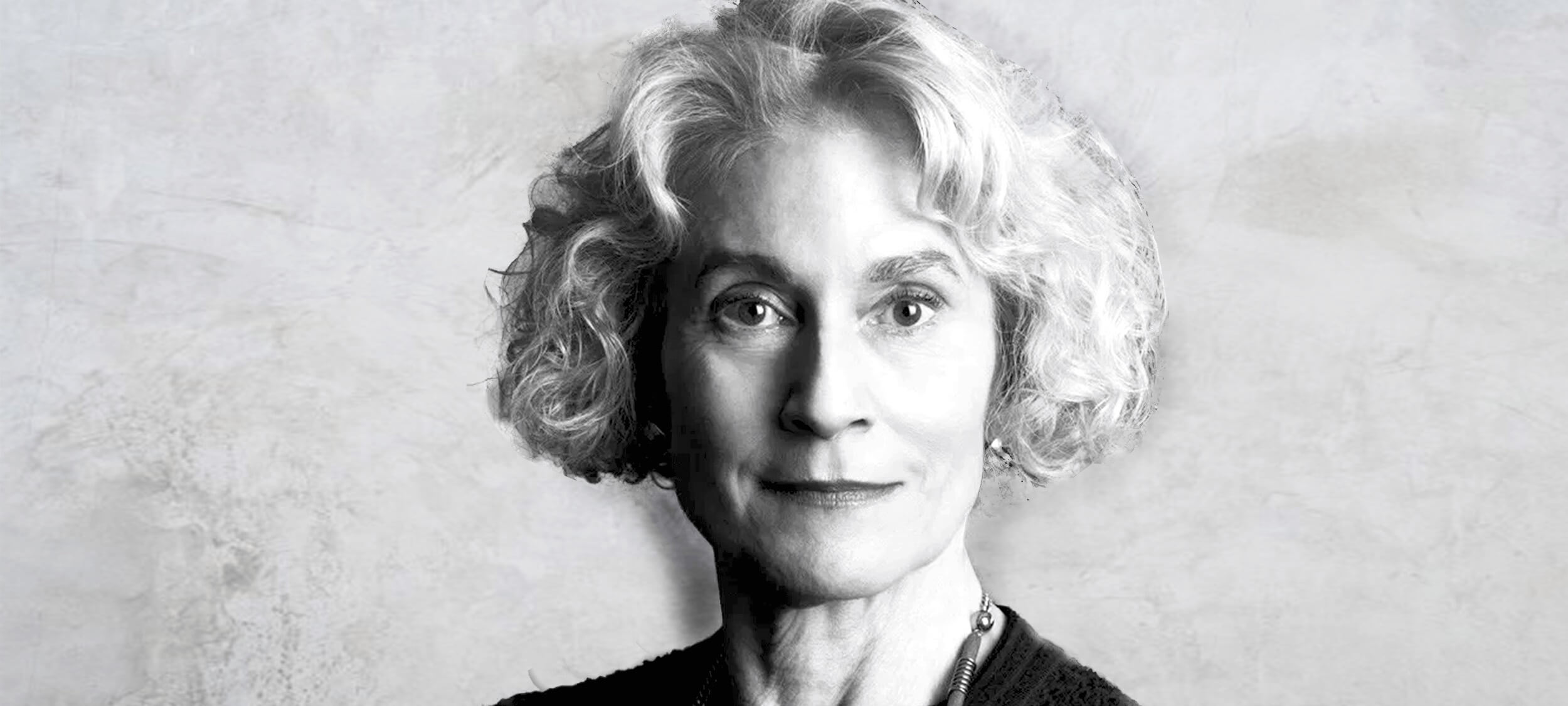

Big Thinker: Mary Wollstonecraft

Big Thinker: Mary Wollstonecraft

Big thinkerPolitics + Human RightsRelationships

BY Kym Middleton The Ethics Centre 22 NOV 2017

Mary Wollstonecraft (1759—1797) is best known as one of the first female public advocates for women’s rights. Sometimes known as a “proto-feminist”, her significant contributions to feminist thought were written a century before the word “feminism” was coined.

Wollstonecraft was ahead of her time, both intellectually and in the way she lived. Pursuing a writing career was unconventional for women in 18th century England and she was denounced for nearly a century after her death for having a child out of wedlock. But later, during the rise of the women’s movement, her work was rediscovered.

Wollstonecraft wrote many different kinds of texts – including philosophy, a children’s book, a fictional novel, socio-political pamphlets, travel writings, and a history of the French Revolution. Her most famous work is her essay, A Vindication of the Rights of Woman.

Pioneering modern feminism

Wollstonecraft passionately articulated the basic premise of feminism in A Vindication of the Rights of Woman – that women should have equal rights to men. Though the essay was published during the French Revolution in 1792, its core argument that women are unjustifiably rendered subordinate to men remains.

Rather than domestic violence, women in senior roles and the gender pay gap, Wollstonecraft took aim at marriage, beauty, and women’s lack of education.

The good wife: docile and pretty

At the core of Wollstonecraft’s critique was the socioeconomic necessity for marriage – “the only way women can rise in the world”. In short, she argued marriage infantilised women and made them miserable.

Wollstonecraft described women as sacrificing respect and character for far less enduring traits that would make them an attractive spouse – such as beauty, docility, and the 18th century notion of sensibility. She argued, “the minds of women are enfeebled by false refinement” and they were “so much degraded by mistaken notions of female excellence”.

Mother of feminism and victim blamer?

Some readers of A Vindication for the Rights of Woman argued Wollstonecraft was only a small step away from victim blaming. She penned plenty of lines positioning women as wilful and active contributors to their own subjugation.

In Wollstonecraft’s eye, expressions of feminine gender were “frivolous pursuits” chosen over admirable qualities that could lift the social standing of her sex and earn women respect, dignity and quality relationships:

“…the civilised women of the present century, with few exceptions, are only anxious to inspire love, when they ought to cherish a nobler ambition, and by their abilities and virtues exact respect.”

While some might find Wollstonecraft was too harsh on the women she wanted to lift, her spear was very much aimed at men, “who considering females rather as women than human creatures, have been more anxious to make them alluring mistresses than rational wives”.

Grab it by the patriarchy

Like the word feminism, the word patriarchy was not available to Wollstonecraft. She nevertheless argued men were invested in maintaining a society where they held power and excluded women.

Wollstonecraft commented on men’s “physical superiority” although she did not accept social superiority should follow.

“…not content with this natural pre-eminence, men endeavour to sink us still lower, merely to render us alluring objects for a moment.”

Wollstonecraft’s hammering critique against a male dominated society suggested women were forced to be complicit. They had few work options, no property or inheritance rights, and no access to formal education. Without marriage, women were destined to poverty.

What do we want? Education!

Wollstonecraft pointed out all people regardless of sex are born with reason and are capable of learning.

In a time where it was considered racial to insist women were rational beings, Wollstonecraft raised the common societal belief that women lacked the same level of intelligence as men. Women only appeared less intelligent, Wollstonecraft argued, because they were “kept in ignorance”, housebound and denied the formal education afforded to men.

Instead of receiving a useful education, women spent years refining an appealing sexual nature. Wollstonecraft felt “strength of body and mind are sacrificed to libertine notions of beauty”. Women’s time was poorly invested.

How could women, who were responsible for raising children and maintaining the home, be good mothers, good household managers or good companions to their husbands, if they were denied education? Women’s education, Wollstonecraft contended, would benefit all of society.

Wollstonecraft suggested a free national schooling system where girls and boys were taught together. Mixed sex education, she argued, “would render mankind more virtuous, and happier” – because society and the term mankind itself would no longer exclude girls and women.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Business + Leadership

Political promises and the problem of ‘dirty hands’

Explainer

Society + Culture, Politics + Human Rights

Ethics Explainer: Just Punishment

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

5 ethical life hacks

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

How to break up with a friend

BY Kym Middleton

Former Head of Editorial & Events at TEC, Kym Middleton is a freelance writer, artistic producer, and multi award winning journalist with a background in long form TV, breaking news and digital documentary. Twitter @kymmidd

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Ethics Explainer: Conscience

Conscience describes two things – what a person believes is right and how a person decides what is right. More than just ‘gut instinct’, our conscience is a ‘moral muscle’.

By informing us of our values and principles, it becomes the standard we use to judge whether or not our actions are ethical.

We can call these two roles ethical awareness and ethical decision making.

Ethical Awareness

This is our ability to recognise ethical values and principles.

The medieval philosopher Thomas Aquinas believed our conscience emerged from synderesis: the ‘spark of conscience’. He literally meant the human mind’s ability to understand the world in moral terms. Conscience was the process by which a person brought the principles of synderesis into a practical situation through our decisions.

Ethical Decision Making

This is our ability to make practical decisions informed by ethical values and principles.

In his writings, Aristotle described phronesis: the goodness of practical reason. This was the ability to evaluate a situation clearly so we would know how to act virtuously under the circumstances.

A conscience which is both well formed (shaped by education and experience) and well informed (aware of facts, evidence and so on) enables us to know ourselves and our world and act accordingly.

Seeing conscience in this way is important because it teaches us ethics is not innate. By continuously working to understand our surroundings, we strengthen our moral muscle.

Conscientious Objection

In politics, much of the debate around conscience concerns the “right to conscientious objection”.

- Should pro-life doctors be required to perform abortions or refer patients to doctors who will?

- Must priests break the confessional seal and report sex offenders who confess to them?

- Can pacifists be excused from conscription because of their opposition to war?

For a long time, Western nations, informed by the Catholic intellectual tradition, believed in the “primacy of conscience” – the idea that a person should never be forced to do something they believe is against their most deeply held values and principles.

In recent times, particularly in medicine, this has come to be questioned. Australian bioethicist Julian Savulescu believes doctors working in the public system should be banned from objecting to procedures because it compromises patient care.

This debate sees a clash between two worldviews – one where people’s foremost responsibility is to their own personal beliefs about what is good and right and another where this duty is balanced against the needs of the common good.

Philosopher Michael Walzer believes there are situations where you have a duty to “get your hands dirty” – even if the price is your own sense of goodness. In response, Aristotle might have said, “no person wishes to possess the world if they must first become someone else”. That is, we can’t change who we are or what we believe in for any price.

Recommended viewing

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Duties of care: How to find balance in the care you give

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

How to give your new year’s resolutions more meaning

Opinion + Analysis

Climate + Environment, Relationships

You can’t save the planet. But Dr. Seuss and your kids can.

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Moral fatigue and decision-making

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Ethics Explainer: Progressivism

Progressivism is a political ideology based on the possibility of moral progress. In practice, this looks like an optimism about the future of humanity.

Progressives believe the course of human history is moving us closer to a state of peace, equality, and prosperity. They also tend to believe in human perfectibility. Politics, technology, and education can overcome human failings to create a utopia.

We can see this in the work of philosophers Steven Pinker and Michael Shermer. Pinker says since the Enlightenment, altruism has been on the rise and violence is declining around the world. Shermer suggests each generation has been smarter than the last, which he believes, has continually reduced impulsive violence.

Hegel’s synthesis

German philosopher Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel believed moral progress was inescapable. He thought the forces of history shape humanity for the better, pushing it toward perfection.

Hegel believed history unrolled according to a “dialectical” pattern. This was where opposing sides clashed and compromised with one another. These opposing forces, which he called the “thesis” and “antithesis”, would clash before reaching a “synthesis”.

This synthesis would then spark a new antithesis and the process would continue. Hegel thought each stage in the thesis-antithesis-synthesis series moved us closer to a state of perfection. His work is said to have inspired other progressive thinkers, most notably communist philosopher Karl Marx.

The darker side of progress

Today, new forms of genetic editing promise a cure to a range of illnesses and maybe even death itself. Transhumanists believe we can overcome the limitations of our humanity and mortality. They suggest a range of options, from changing our biology to uploading our consciousness into a supercomputer.

But practical efforts to create this perfect world have not always been pleasant. At times it has been outright barbaric.

One example is the eugenics movement. It aimed to breed some people, like those with disabilities, out of society altogether, and cited social progress as their defence.

This is one reason why conservatives often urge caution around progress. They encourage us to be mindful of the potential unintended side effects of new policies or technology.

But progressives are often concerned this will inhibit life changing new developments. They suggest we deal with issues as they arise, rather than trying to predict them in advance.

Heaven on earth

Progressives often see education as the silver bullet solution for social problems. Like Ancient Greek philosopher Socrates, they tend to believe all vice is the result of ignorance, not malice. They suggest humans are fundamentally good and education will bring out the better angels of our nature.

But some are sceptical whether education alone will fix all humanity’s woes. They agree humans are mostly good but don’t blame ignorance for evil. Instead, they see war, conflict and violence as the product of oppression and inequality.

Karl Marx believed conflict between the wealthy and the working class was a central theme in human society. He believed the power imbalance between rich and poor was bad for everyone. He famously claimed people would be better throwing away hierarchies based on class and wealth. Only when we’re all equal, he thought, will we be able to perfect ourselves.

English philosopher Mary Wollstonecraft suggested the path to human perfection might require both politics and education. She argued that political change requires us to educate marginalised groups. Otherwise, any change will continue to exclude the groups already on the fringes of society.

This explains why more women and culturally diverse people have contributed to progressive thinking in recent decades. In the past, the leading progressive thinkers tended to be white men. Improved access to education has enabled a greater range of voices to contribute to the larger conversation of what a perfect world might look like and how we could create it.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Big thinker

Relationships

Seven Female Philosophers You Should Know About

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Climate + Environment, Relationships

ESG is not just about ticking boxes, it’s about earning the public’s trust

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Begging the question

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Ozi Batla: Fatherhood is the hardest work I’ve ever done

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Big Thinker: Socrates

Socrates (470 BCE—399 BCE) is widely considered to be one of the founders of Western philosophy.

Stonemason, soldier, citizen, philosophy’s first ‘martyr’, Socrates helped shape one of the major intellectual foundations on which Western civilisation has been built. Yet, no work of philosophy bears his name as the author. All we know of him is derived from the work of others – especially Plato, Xenophon and Aristophanes.

The rise of ethics

Prior to Socrates, ancient philosophy tended to focus on questions that today might be considered the domain of physics. ‘Pre-Socratic’ philosophers tended to focus on fundamental questions about the nature of the universe – like the building blocks of matter or the nature of time and motion.

When Socrates came along, he proposed a completely different set of questions for philosophical deliberation. He drew attention away from questions about how the world is and towards questions about how we are to be in the world. While he made valuable contributions to the evolution of thought about epistemology and politics, it is this turn toward ethics that introduced a fresh practical dimension to philosophy.

Earlier philosophical debates of Thales, Anaximander and Democritus, for example, were all theoretical. Human knowledge and understanding might have advanced, but nothing in the world was directly changed by their deliberations.

Socrates’ focus on ethics was intended to generate practical outcomes. He expected philosophical work might lead to a change in both attitudes and (importantly) actions of people. In turn, this was intended to produce effects in the world. Although we have only come to see Socrates through the eyes of others, his friends (like Plato and Xenophon) and foes (like Aristophanes) agree he wished to have an impact on the people around him and the kind of society they were creating as a result of their choices.

What friends and foes disagreed on was Socrates’ motivation. His critics lumped him in with the Sophists who were looked down on as philosophical guns for hire.

A new focus on ethics repositioned philosophy as something relevant to everyday life. Socrates’ core question, ‘What ought one to do?’ does not apply in a limited set of circumstances. It is a question of general application to any situation where a choice is to be exercised – and is applicable to every person, whatever their station in life.

In some sense, this is what made Socrates such a troublesome – or dangerous – person. In one fell swoop, he brought philosophy into the agora (the marketplace), making it relevant and accessible to people of all ages and degrees.

This upset hierarchies and orthodoxies. As we know, a gadfly is rarely welcome. Socrates was eventually executed for crimes of ‘impiety’ and ‘corrupting the youth’ – in short, for teaching and encouraging them to question established norms and think for themselves.

The virtue of ‘constructive ignorance’

On being asked who the wisest person in Athens was, the Oracle of Delphi nominated Socrates. Socrates was astounded – he believed himself to know nothing. To prove his relative ignorance, Socrates sought to find wiser folk amongst the citizens of Athens, questioning them at length about the nature of things like justice and love.

His questioning had practical implications. At that time in democratic Athens, citizens were actively involved in enacting laws or judgements in the courts.

In the end, Socrates came to believe the Oracle of Delphi was correct – but only because his superior wisdom lay in his realising the limits of his knowledge.

Along the way to this realisation, Socrates developed the process of elenchus (the ‘Socratic method’). It is a distinctive form of questioning designed to open space for insight and self-knowledge. The idea we have much to learn about ourselves and the world might suggest we are ignorant. Such a view could position the Socratic method of questioning as a mean spirited exercise. Those subjected to it did not necessarily enjoy the experience or see it in a positive light. This no doubt contributed to the belief Socrates was an impious trouble maker.

The importance of the examined life

Although Socrates contributed many insights that are still drawn upon today (but not necessarily accepted), one of his most famous and profound is his claim that ‘the unexamined life is not worth living’.

This claim goes beyond being a recommendation we should think before we act – which may be a prudent thing to do. Socrates is attempting to draw our attention to a deeper truth about the human condition. He encourages us to participate in a form of being that has the capacity to transcend the requirements of instinct and desire in order to make conscious – that is, ethical – choices. Socrates claimed if we fail to do this, we live a lesser life.

One of the effects of examination is, according to Socrates, the development of phronesis (practical wisdom) which is the foundation for virtue. For Socrates (and later for Aristotle – in a slightly different form), the possession of virtue is not just a matter of interior orientation. It is essential to being able to see the world as it is and be able to make good decisions.

Like Aristotle, Socrates sees vice as the source of defective vision. Socrates thought people make bad choices and do bad things out of ignorance. He thought if people could only ‘see’ what is good, they would choose it.

This all finally comes together in the way Socrates challenged the status quo. To live an examined life is to reject things ought to be done just because they have always been done.

Instead, Socrates is an early exponent of an inner voice that (in Socrates’ case) is supposed to have warned him against making an error. Socrates called this voice his ‘daimōnic sign’ – something Aquinas would call ‘conscience’ over a thousand years later.

It may be difficult to distinguish the real Socrates from the versions of the man created by others – which were either celebratory or lampooning. But this we know. When given the chance to escape and avoid the sentence of death imposed on him by the Athenians, Socrates chose to stay. In defence of his ideas and in conformance with his ideals Socrates drank the hemlock and died.

He can hardly have imagined the impact he would have on the world.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

The danger of a single view

Explainer

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Ethics Explainer: The Harm Principle

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

What does love look like? The genocidal “romance” of Killers of the Flower Moon

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Adoption without parental consent: kidnapping or putting children first?

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

The pivot: Mopping up after a boss from hell

The pivot: Mopping up after a boss from hell

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + LeadershipRelationships

BY Rhonda Brighton Hall The Ethics Centre 10 OCT 2017

How would you feel if you had been harassed on an internet dating site and blocked the person, only to turn up for a new job and find out that they’re your boss?

It gets worse. The harassment continued outside of work and then the new boss started “performance managing” the employee out of the business, making complaints about the quality of their work.

This actually happened and I found out about it when the mother of the victim phoned me (as a HR executive) to say, “This is what happened to my son in your business”.

The young man, who we shall call Darren, had been an ambitious high performer. But, after a 12-week period with his new boss, he resigned – blowing up his career to escape the situation.

Now, he was seriously depressed, could not get out of bed and his mother was very concerned about his mental wellbeing.

There was some conjecture it may not have been a coincidence that the harasser had turned up as his boss. He may have deliberately sought to connect with his new team outside work before starting in the job.

The path forward was not totally clear. Darren had not made a complaint himself. It was his mother who made the call and supplied me with screenshots of text messages, without Darren’s consent.

He had also already left the company, but was obviously in a very bad space. Also, if he had resigned because of the harassment, it could potentially be regarded as “constructive dismissal” (an unlawful termination of employment).

And I now had someone working in the business who had apparently been a harasser on social media and had forced his victim out of his job. You don’t want a leader who performance manages people who won’t date them, or even someone who allows that perception to take hold.

It had to be investigated because, if it was true, I couldn’t just leave it as a time bomb waiting for the next person to attract his interest.

My legal and moral obligations were not necessarily the same. I had to respond to the situation as both a HR person and a leader, because I had executive responsibility for the part of the business they both worked in.

From a moral perspective, I had to consider whether my response was an almost parental reaction. Had I wanted to protect an employee who I discovered had been harassed out of his job because a complaint came from his mother?

It was a tricky situation, but we went through a quiet investigative process. I contacted Darren and he didn’t want to come back to the company.

The really important lesson in dealing with cases such as these is to discuss the human impact at the same time that you are discussing the legalities. They need to come together, they can’t be separated.

I arranged for better support and counselling for him. That was a risk because, in a court case, it could have been construed as an admission of responsibility and it could have gone on to become a Workers’ Compensation or Human Rights Discrimination issue.

But there must be a degree of humanity – you can’t just leave someone broken and walk on by.

When I called his former boss into an interview, he became very angry. He said his activity on the dating site was his private life and none of our business.

A mature leader would have disclosed the conflict in their relationship as soon as they started at the company, so that it could be managed ethically. Instead, he went for Darren, hammer and tongs with the performance issue.

We disciplined him and he ended up resigning shortly afterwards of his own free will.

The really important lesson in dealing with cases such as these is to discuss the human impact at the same time that you are discussing the legalities. They need to come together, they can’t be separated.

It is also important to deal quickly with these things because nothing gets better if it festers away. If I look at the really bad cases I have mopped up, there have been a lack of investigative outcomes, a lack of definitive decisions and/or lack of clarity about what will be done.

Some of these cases drag on for years and someone leaves the workforce, broken. They progressively end up in really bad financial shape as well. Time stands still for them because they are either coming into a workplace where someone is continuing to harass them or they are isolated at home. While you’re deciding what to do, the issue is overwhelming their every day.

This article was originally written for The Ethics Alliance. Find out more about this corporate membership program. Already a member? Log in to the membership portal for more content and tools here.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

Meet Josh, our new Fellow asking the practical philosophical questions

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Ethics

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Want to live more ethically? Try these life hacks

Reports

Business + Leadership

Ethics in the Boardroom

BY Rhonda Brighton Hall

Rhonda Brighton-Hall is a non-executive director of the Australian Human Resources Institute and founder of MWAH (Make Work Absolutely Human), Chair of FlexCareers, Former Telstra Business Woman of the Year and HR Leader of the Year.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Assisted dying: 5 things to think about

Assisted dying: 5 things to think about

Opinion + AnalysisPolitics + Human RightsRelationships

BY The Ethics Centre 24 AUG 2017

Making sense of our lives means thinking about death. Some philosophers, like Martin Heidegger and Albert Camus, thought death was a crucial, defining aspect of our humanity.

Camus went so far as to say considering whether to kill oneself was the only real philosophical question.

What these philosophers understood was that the philosophical dream of living a meaningful life includes the question of what a meaningful death looks like, too. More deeply, they encourage us to see that life and death aren’t opposed to one another: dying is a part of life. After all, we’re still alive when we’re dying so how we die impacts how we live.

The Ethics Centre was invited to make a submission to the NSW Parliamentary Group on Assisted Dying regarding a draft bill the parliament will debate soon. The questions we raised were in the spirit of connecting the good life to a good death.

Simon Longstaff, director of the Centre and author of the submission, writes, “It is not the role of The Ethics Centre to prescribe how people ought to decide and act. Our task is a more modest one – to set out some of the ethical considerations a person might wish to take into account when forming a view.”

Here are some of the key issues we explored, which are relevant to any discussion of assisted dying, not just the NSW Bill.

Does a good life involve suffering?

The most common justification for assisted dying or euthanasia is to alleviate unbearable suffering. This is based in a fairly universal sentiment. Longstaff writes, “To our knowledge, there is no religion, philosophical tradition or culture that prizes suffering … as an intrinsic good”.

Good things can come as a result of suffering. For example, you might develop perseverance or be supported by family. But the suffering itself is still bad. This, Longstaff argues, means “suffering is generally an evil to be avoided”.

There are two things to keep in mind here.

First, not all pain is suffering. Suffering is a product of the way we interpret ourselves and the world around us. Whether pain causes suffering depends on our response: It’s a subjective experience. Nobody but the sufferer can really determine the extent of their suffering. Recognising this could suggest a patient’s self-determination is crucial to decisions around assisted dying.

Second, just because suffering is generally a bad thing doesn’t mean that anything aiming to avoid it is good. We can agree that the goal of reducing suffering is probably good but still need to interrogate whether the method we’ve chosen to reduce suffering is itself ethical.

The connection between a good death and a good life

There’s not always a solution to suffering, no matter what anecdote you try, whether it be medicine, psychology, religion or philosophy. Sometimes suffering stays a while.

When there is no avenue to alleviate someone’s pain and anguish, Longstaff suggests “life can be experienced … as nothing more than an unrelenting and extra-ordinary burden”.

This is the context in which we should consider whether to help someone to end their lives or not. Although many faiths and beliefs affirm the importance and sacredness of life, if we’re thinking about a good, meaningful life, we need to pay some attention to whether life is actually of any value to the person living it. As Longstaff writes, “To say that life has value regardless of the conditions of a person’s existence may justify the continuation or glorification of lives that could be best described as a ‘living hell’”.

He continues, “To cause such a state would be indefensible. To allow it to persist without available relief is to act without mercy or compassion. To set aside those virtues is to deny what is best in our form of being.”

A responsible person should have autonomy over their death

Most people think it’s important for adults to be held responsible for their actions. Philosophers think this is a product of autonomy – the ability for people to determine the course of their own actions and lives.

Some philosophers think autonomy has an intrinsic connection to dignity. What makes humans special is their ability to make free choices and decisions. What’s more, we usually think it’s wrong to do things that undermine the free, autonomous choices of another person.

If we see death as a part of life, not distinct from it, it seems like we should allow – even expect – people to be responsible for their deaths. As Longstaff writes, “since dying is a part of life, the choices people make about the manner of their dying are central considerations in taking full responsibility for their lives”.

The role of the terminal disease

Some proposed laws, like the draft NSW Bill, suggest a person can seek to end their own life when their terminal disease causes them unbearable suffering. So, if you’re dying of lung cancer, you can only end your life if the cancer itself is causing you unbearable pain. It is necessary to consider if assisted dying be restricted in this way.

Imagine you’ve got a month to live and the only thing that gives you meaning is your ability to go outside and watch the sunrise. One day, you break your leg and are bedridden. Should you now be forced to live for a month in a state you find agonising and meaningless because your broken leg isn’t what’s killing you?

Longstaff argues, “If severe pain and suffering are essential criteria for being eligible for assistance, then on the basis that like cases should be treated in a like manner, assistance should be offered to a person who meets all the other specified criteria – even if their pain and suffering is not caused by their illness”.

Who is eligible for assisted dying?

Many laws try to carve out special categories of people who are and aren’t eligible to request assisted dying. They might do so on the basis of life expectancy, whether the illness is terminal or the age of the patient.

In determining who should be eligible, two principles are worth thinking about.

First, the principle of just access to medical care. Most bioethicists agree before we can figure out who receives medical treatment, we need to have a broader idea of what justice looks like.

Some think justice means people get what they need. For these people, granting medical care is based on how urgently it’s required. Others think justice means getting the best outcome. These people think we should distribute medicine in a way that creates the most quality of life for patients.

Depending on how we view justice, we’ll have different views on who is eligible for assisted dying. Is it those whose quality of life is lowest? If so, it might not be terminal cases in need of treatment. Is it those who are most in need of treatment? This might include young children who many people are reluctant to provide assisted dying to. Until we’re clear on this principle, it’ll be hard to decide who is eligible and who is not.

The second principle worth thinking about is to treat like cases alike. This idea comes from the legal philosopher HLA Hart. He thought it was essential for ethical and legal distinctions to be made on the basis of good reasons, not arbitrary measures. A good example is if two people committed the same crime, they should receive the same penalty. The only reason for not treating them the same is if there is relevant difference in the two cases.

This is important to think about in terms of strict eligibility criteria. Let’s say we reserve assisted dying for people over 25 years old, which the NSW draft Bill does. Hart would encourage us to wonder, as Longstaff noted in The Ethics Centre’s submission, “what ethically significant difference lies between a 24-year-old with six months to live and who wishes to receive assisted dying and a 25-year-old in the same condition?”

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

5 lessons I’ve learnt from teaching Primary Ethics

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

The danger of a single view

Explainer

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Social philosophy

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Peter Singer on charitable giving

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Ethics Explainer: Conservatism

Contrary to what many assume, the conservative political tradition is neither reactionary nor opposed to change. True conservatives are simply wary of revolutionary change – especially when inspired by utopian idealism.

Conservatives prefer an evolutionary approach, where experience, common sense, and pragmatism lend a certain stability to society and its institutions.

We could sum up the conservative political outlook in a couple of maxims:

-

“If it ain’t broke, don’t fix it”

-

“Don’t throw the baby out with the bathwater”

It is important to distinguish between conservatism as an ideological outlook and the conservative brand some political parties operate under. Some practice the type of cautious conservatism described above, whereas others are more radical in their outlook.

Conservatism is often associated with liberalism, unregulated capitalism, and in some cases, libertarianism. This is no accident. It’s the product of a mixed history of ideas and the occasional opportunism of certain individuals and political parties who have misappropriated the term for their own political ends.

Vive la révolution!

The most famous and early exponent of conservatism is the Irish-British philosopher, Edmund Burke. In most respects, the long-standing member of the British House of Commons was a classic liberal, respecting the ideals of liberty and equality.

But Burke found the French Revolution a step too far. A quick history lesson: the French Revolution was a 10-year uprising that began in 1789 against the aristocratic social and political systems. It eventually overthrew the monarchy.

In the revolution’s push for radical change, Burke saw the seeds of what we might now call totalitarianism – a society where the individual counts for nothing and the State for all. Burke captures this in his Second Letter on Regicide Peace where, describing the Revolutionary Government of France, he wrote:

“Individuality is left out of their scheme of government. The State is all in all. Everything is referred to the production of force; afterwards, everything is trusted to the use of it. It is military in its principle, in its maxims, in its spirit, and in all its movements. The State has dominion and conquest for its sole objects—dominion over minds by proselytism, over bodies by arms.”

This aversion to radical idealism and its tendency to lay the foundation for a totalitarian state is a theme frequently returned to by conservative philosophers. For example, Karl Popper observes in The Open Society and Its Enemies (Volume One):

“The Utopian attempt to realize an ideal state, using a blueprint of society as a whole, is one which demands a strong centralized rule of a few, and which is therefore likely to lead to a dictatorship.”

Like the pigs in George Orwell’s Animal Farm, after all the unrest and upheaval of the French Revolution, overthrowing the monarchy led to Napoleon’s rule, which is widely regarded as a totalitarian dictatorship. The conservative critique of efforts toward revolutionary change provide such examples as an argument for cautious and prudent evolution instead.

Conservatives are likely to feel that proponents of radical change often fail to realise that they will also be swept aside if something entirely new is to be made. As the contemporary philosopher in the ‘Burkean’ mould, Roger Scruton puts it:

“All that conservatism ultimately means, in my view, is the disposition to hold on to what you know and love. And if you don’t hold on to what you know and love, you will lose it anyway.”

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Double-Effect Theory

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

How to pick a good friend

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics explainer: Cultural Pluralism

Big thinker

Relationships

Big Thinker: René Descartes

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Big Thinker: Martha Nussbaum

Martha Nussbaum (1947—present) is one of the world’s most influential living moral philosophers.

She has published on a wide range of topics, from tragedy and vulnerability, to religious tolerance, feminism and the role of the emotions in political life. Nussbaum’s work combines rigorous philosophy with insights from literature, history and law.

Our happiness is largely beyond our control

Nussbaum takes issue with people like the Stoics and Immanuel Kant, who suggest there is no place for emotion within ethics. They believe ethics is about the things we can control. It’s about the things that can’t be lost or taken away from us, like our thoughts and our virtues.

For instance, in his Groundwork to the Metaphysics of Morals, Kant claimed even if bad luck or circumstance meant you were unsuccessful in everything you tried to do, so long as you acted with a “good will”, your actions would still “shine like a jewel”.

By contrast, Nussbaum believes the fact our intentions, desires and hopes can be thwarted by circumstances tells us something really important about flourishing (that’s philosophy speak for living the good life). Specifically, that it’s vulnerable and fragile.

She may have had Kant’s writing in mind when she wrote the ethical life “is based on a trust in the uncertain and on a willingness to be exposed; it’s based on being more like a plant than like a jewel, something rather fragile, but whose very particular beauty is inseparable from its fragility”.

Risk is a scary notion in our society. We don’t like thinking about it and we’re not good at judging it accurately. Part of that is because we don’t like uncertainty. But Nussbaum encourages us to reframe our attitude to vulnerability, seeing it as a unique aspect of what it means to be human.

“To be a good human being is to have a kind of openness to the world, an ability to trust uncertain things beyond your own control.”

Politics doesn’t work without emotion

Most political philosophers and commentators are wary of the place of emotion in politics. When we think about the role of emotions in politics, it’s easy to focus on fear, disgust, envy and the ways they can corrupt our political life. It’s natural to assume politics would be better without the emotion, right?

Not according to Nussbaum. She suggests scrubbing politics clean of emotion would be like throwing the baby out with the bathwater. Yes, we need to be wary of the role of emotions in politics, but we couldn’t survive without them.

For one thing, it’s emotions like love and compassion that translate abstract concepts like truth and justice into real and lasting connections with particular groups and people. Ideas like human dignity capture what we all have in common but strong democracies tend to respect what makes different groups and people unique.

Emotions help us to cultivate a healthy balance between our attachments to ideas and institutions and our connection to particular places, people and histories. For Western democracies struggling to deal with different cultural groups and ideologies, Nussbaum’s view may help strike a balance between society-wide ideals and particular cultural differences.

What’s more, Nussbaum notes, political systems have always cultivated the emotions that serve them best. For example, monarchies cultivate childlike emotions of dependence and dictatorships often trade on a combination of nationalism and fear. These emotions create unity around a common political identity – albeit in ways people find problematic.

There’s promising terrain here, Nussbaum says, because if we can work out the emotions that best serve democratic life, we can then cultivate these emotions and create better citizens.

She thinks we can do this through ritual, public investments in art and a living sense of cultural and national history (she offers the rewriting of America’s founding fathers in Hamilton as a good example of this).

Nussbaum advises we can foster the emotions for citizenship with whatever “helps us to see the uneven and often unlovely destiny of human beings in the world with humour, tenderness, and delight, rather than with absolutist rage for an impossible sort of perfection”.

Educate for citizenship, not profitability

In Not for Profit: Why Democracy Needs the Humanities, Nussbaum targets the education system. She gives an ominous diagnosis:

Thirsty for national profit, nations, and their systems of education, are heedlessly discarding skills that are needed to keep democracies alive. If this trend continues, nations all over the world will soon be producing generations of useful machines, rather than complete citizens who can think for themselves, criticize tradition, and understand the significance of another person’s sufferings and achievements. The future of the world’s democracies hangs in the balance.

Nussbaum believes there is a crucial role for the education system – from early school to tertiary – in building a different kind of citizen. Rather than economically productive and useful, we need people who are imaginative, emotionally intelligent and compassionate.

She is also critical of the ‘No Child Left Behind’ approach to education in the United States, which put increasing pressure on schools to improve outcomes. They wanted to know test scores were improving, believing better education outcomes would help break the cycle of poverty. However, in focussing on outcomes, Nussbaum believes they prioritised memorising over the kind of education she thinks democracies need – philosophy.

You might be sceptical whether people stuck in a cycle of poverty need an education offering philosophical skills. The pressing need to be economically useful and employable can be seen as more urgent and important with good reason. It’s likely there’s a compromise to be struck here, but Nussbaum’s work is still important.

It provides us with an alternative model of education and helps us see the beliefs underpinning our current attitudes to education.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Would you kill baby Hitler?

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Climate + Environment

Blindness and seeing

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

How can you love someone you don’t know? ‘Swarm’ and the price of obsession

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

Meet Eleanor, our new philosopher in residence

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Big Thinker: Simone de Beauvoir

Big Thinker: Simone de Beauvoir

Big thinkerRelationshipsSociety + Culture

BY The Ethics Centre 18 MAY 2017

Simone de Beauvoir (1908—1986) was a French author, feminist and existential philosopher. Her unconventional life was a working experiment of her ideas – that one creates the meaning of life through free and authentic choices.

In a cruel confirmation of the sexism she criticised, Beauvoir’s work is often seen as less important than that of her partner, Jean Paul Sartre. Given the conclusions she drew were hugely influential, let’s revisit her ideas for a refresher course.

Women aren’t born, they’re made

Beauvoir’s most famous quote comes from her best-known work, The Second Sex: “One is not born, but rather becomes, a woman”.

By this she means there is no essential definition of womanhood. Women can be anything, but social norms work hard to fit them into a particular kind of femininity. These social norms are patriarchal and born out of the male gaze.

The Second Sex argues that it’s men who define what women should be. Because men have always held more power in society, the world looks the way men want it to look. An obvious example is female beauty.

Beauvoir holds that through norms around removing body hair, makeup and uncomfortable fashion, women restrict their freedom to serve the male gaze.

This objectification of women goes deeper, until they aren’t seen as fully human. Men are seen as active, free agents who are in control of their lives. Women are described passively. They need to be protected, controlled or rescued.

It’s true, she thinks, that women aren’t always seen as passive objects, but this only happens when they impersonate men.

“Man is defined as a human being and woman as a female – whenever she behaves as a human being she is said to imitate the male.”

For Beauvoir, women are always cast into the role of the Other. Who they are matters less than who they’re not: men. This is an enormous problem for the existentialist, for whom the purpose of life is to freely choose who they want to be.

Everyone has to create themselves

As an existentialist, Beauvoir believed people need to live authentically. They need to choose for themselves who they want to be and how they want to live. The more pressure society – and other people – place on you, the harder it is to make an authentic choice.

Existentialists believe no matter the amount of external pressure, it is still possible to make a free choice about who we want to be. They say we can never lose our freedom, though a range of forces can make it harder to exercise. Plus, some people choose to hide from their freedom in various ways.

Some of us hide from our freedom by living in bad faith, embracing the definitions other people put on us. Men are free to reject the male gaze and stop imposing their desires onto women but many don’t. It’s easier, Beauvoir thinks, to accept the social norms we’re born into. To live freely and authentically is the greater struggle.

The importance of freedom led Beauvoir to suggest liberated women should not try to force other women to live their lives in a similar way. If a small group of women choose to reject the male gaze and define womanhood in their own way, that’s great.

But respecting other people means allowing them to live freely. If other women don’t want to join the feminist mission, Beauvoir believed they should not be forced or pressured to do so. This is important advice in an age where online shaming is often used to force people to conform to popular social views.

We’re as ageist as we are sexist

Later in life, Beauvoir applied her arguments about women in The Second Sex to the plight of the elderly. In The Coming of Age, she argued that we make assumptions and generalisations about the elderly and ageing, just like we do about women.

To her, it is as wrong to ‘other’ women because they are different from men, as it is to ‘other’ the elderly because they are different from the young. Feminist philosopher Deborah Bergoffen explains Beauvoir’s view: “As we age, the body is transformed from an instrument that engages the world into a hindrance that makes our access to the world difficult”.

Like women in The Second Sex, the elderly remain free to define themselves. They can reject the idea that physical decline makes them unable to function as authentic human beings.

In The Coming of Age, we see some of the foundations of today’s discussions about ageism and ableism. Beauvoir urges us to come back to a simple truth: the facts of our existence – what our bodies are like, for example – don’t have to define us.

More importantly, it’s wrong to define other people only by the facts of their existence.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Big thinker

Relationships

Big Thinker: Buddha

Big thinker

Relationships

Big Thinkers: Laozi and Zhuangzi

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Whose home, and who’s home?

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships