How should vegans live?

How should vegans live?

Opinion + AnalysisClimate + EnvironmentHealth + Wellbeing

BY XAVIER COHEN The Ethics Centre 24 JAN 2016

Ethical vegans make a concerted lifestyle choice based on ethical – rather than, say, dietary – concerns. But what are the ethical concerns that lead them to practise veganism?

In this essay, I focus exclusively on that significant portion of vegans who believe consuming foods that contain animal products to be wrong because they care about harm to animals, perhaps insofar as they have rights, perhaps just because they are sentient beings who can suffer, or perhaps for some other reason.

Throughout the essay, I take this conviction as a given, that is, I do not evaluate it, but instead investigate what lifestyle is in fact consistent with caring about harm to animals, which I will begin by calling consistent veganism. I argue that the lifestyle that consistently follows from this underlying conviction behind many people’s veganism is in fact distinct from a vegan lifestyle.

It is probably the case that one cannot live without causing harm to animals due to the trade-off in welfare between other animals who are harmed by one’s own consumption.

Let us also begin by interpreting veganism in the way that many vegans – and most who are aware of veganism – would. A vegan consumes a diet containing no animal products. In conceiving of veganism in terms of what a diet contains, there seems to be an intuition about the moral relevance of directness, according to which it matters how direct the harm caused by the consumption of the food is with regards to the consumption of the food.

On this intuition, eating a piece of meat is worse than eating a certain amount of apples grown with pesticides that causes the same amount of harm, because the harm in the first case seems to be more directly related to the consumption of the food than in the second case. Harm from the pesticides seems to be a side-effect of eating the food, whereas the death of the animal for meat seems to be a means to the eating food.

Even if we grant this intuition to be a good in this case, it is not good in the case where the harm is greater from the apples than from the meat. To eat the apples in this case is to not put one’s care about harm to animals first, which means going against the only thing that should motivate a consistent vegan.

Here, our intuition about the amount of harm caused is what seems to matter; if what we care about is harm to animals, then we should cause less rather than more harm to animals, and therefore, from the moral point of view, it seems that it is better to eat the meat than the apples. Let the conviction in this intuition be called the ‘less-is-best’ thesis.

Therefore, the intuition about the directness of the harm is only potentially relevant in situations where one has to choose between alternatives that cause the same amount of harm, or in situations where one does not know which causes more harm. The rest of the time, it seems that consistent vegans should not care about the directness of the harm, but instead care only about causing less rather than more harm to animals.

Consistent vegans should not care about the directness of the harm, but instead care only about causing less rather than more harm to animals.

This requires an awareness of harm that extends further than relatively common considerations noted by vegans regarding animal products being used in the production process for—but not being contained in—foodstuffs like alcoholic drinks. Caring about harm to animals means caring about, less directly, accidental harm to (usually very small) animals from the harvesting process, and from products that have a significant carbon footprint, and thereby contribute to (and worsen) climate change, which is already starting to lead to countless deaths and harm to animals worldwide.

However, caring about harm to animals cannot plausibly require consistent vegans to cause no harm at all to animals. If it did, then in light of the last two examples given above, it seems it would require consistent veganism to be a particularly ascetic kind of prehistoric or Robinson Crusoe-type lifestyle, which would clearly be far too demanding.

In fact, it is probably the case that one cannot live without causing harm to animals due to the trade-off in welfare between other animals who are harmed by one’s own consumption, and oneself (an animal) who is harmed if one cannot consume what one needs to survive. But it is definitely the case that all humans could not survive if no harm to other animals could be caused; this means that either human animals or non-human animals will be harmed regardless of how we live.

We could not all be morally obligated to live in such a way that we could not in fact all live. Therefore, due to this argument and due to such a lifestyle being over-demanding, there are two sufficient arguments for why causing some harm to animals is morally permissible.

If it is the case that causing some harm to animals is morally permissible, then there is no clear reason why there should be a categorical difference in the moral status of acts – such as impermissibility, permissibility, and obligation – with regards to how they harm animals, apart from when these categorical differences arise only from vast differences in the amount of harm caused by different acts.

One’s care for animals should be further-reaching: rather than merely caring about harm one causes, a consistent vegan should care about acting or living in a way that leads to less rather than more harm to animals.

So, for example, shooting a vast number of animals merely for the pleasure of sport may well be impermissible, but only insofar as it causes a much greater amount of harm than alternative acts that one could reasonably do instead of hunting. It seems that the most reasonable position, then, which is in line with the less-is-best thesis, is that the morality of harm to animals is best viewed on a continuum on which causing less harm to animals is morally better and causing more harm to animals is morally worse, where the difference in morality is linked only to the difference in the amount of harm to animals.

Hitherto, I have said that it seems to be the case that consistent vegans care about causing less rather than more harm to animals. However, I claim that the less-is-best thesis should in fact be interpreted as having a wider application than merely harm caused by our actions or life lived. One’s care for animals should be further-reaching: rather than merely caring about harm one causes, a consistent vegan should care about acting or living in a way that leads to less rather than more harm to animals. The latter includes a concern about harm caused by others that one can prevent, which the former excludes as it is not harm caused by oneself.

The impact of social interaction on people’s lifestyles is an important way in which consistent vegans can act or live in a way that leads to less rather than more harm to animals. That nearly all vegans are in fact vegans because they were previously introduced to vegan ideas by others – rather than coming by them and becoming vegan through sheer introspection – is testimony to the impact of social interaction on people’s lifestyles, which in turn can be more or less harmful to animals.

If this recommended lifestyle is too demanding, many will reject it or simply not change, meaning that these people will continue to harm animals.

Consistent vegans have the potential to build a broad social movement that encourages many others to lead lives that cause less harm to animals. But in order to do this, consistent vegans will have to persuade those who do not care about harm to animals (or let care about harm to animals impact their lifestyle) to lead a different kind of lifestyle, and if this recommended lifestyle is too demanding, many will reject it or simply not change, meaning that these people will continue to harm animals.

The vegan lifestyle may seem too hard for many people

If these people are more likely to make lifestyle changes if the lifestyle suggested to them is less demanding, which for many – and probably a vast majority – will be the case, then consistent vegans could bring about less harm to animals if they try to persuade these people to live lifestyles that optimally satisfy the trade-off between demandingness and personal harm to animals. This lifestyle that consistent vegans should attempt to persuade others to follow I shall call “environmentarianism”.

Why ‘environmentarianism’? And what is the content of environmentarianism? Care about harm to animals can be framed in terms of care for the environment, as the environment is partially – and in a morally important way—constituted by animals. This can be easily – and I believe quite intuitively – communicated to those who do care about harm to animals, and those who do not are likely to be more swayed by arguments that are framed in terms of concern for the environment than for animals. Concern for oneself, one’s loved ones, and one’s species – things that most people care greatly about – may be more easily read into the former than the latter, especially in light of impending climate change.

Environmentarianism, then, is the set of lifestyles that seek to reduce harm done to the environment (which is conceived in terms of harm to animals for consistent vegans) – as this matters morally for environmentarians – regardless of which sphere of life this reduction of harm comes from. Be it rational or not, ascribing the title and social institution of ‘environmentarian’ to one’s life will, for many, make them more likely to lead a life that is more in line with caring about harm to animals; people often attach themselves to these titles, as the dogmatic behaviour of many vegans shows.

Some may prefer to reduce total harm to animals by a given amount by making the sacrifice of having a vegan diet, but not compromising on their regular car journey to work, whilst others may find taking on the latter easier than maintaining the strict vegan diet.

Moreover, environmentarianism can be practised to a more or less radical – and thus moral – extent. Some may prefer to reduce total harm to animals by a given amount by making the sacrifice of having a vegan diet, but not compromising on their regular car journey to work, or perhaps by opting out of what for them may be uncomfortable proselytising, whilst others may find taking on the latter two easier than maintaining the strict vegan diet (that they perhaps used to have). Some may reduce total harm by an even greater amount – and hence lead a morally better lifestyle – by having a vegan diet and by refraining from harmful transport and by actively suggesting environmentarianism to others.

As an environmentarian may begin by making very small changes, one can be welcomed into a social movement and be eased in to making further lifestyle changes over time, rather than being put off by the strictness of veganism or the antagonism typical of some vegans. Environmentarianism has the great advantage of making it easier for the many who cannot face the idea of never eating animal products again to live more ethically-driven lives.

It follows from all this, then, that consistent vegans should be (especially stringent) environmentarians. For the given impact they have on the total harm to animals, it does not matter if this comes from a totally vegan diet. In fact, to be fixated on dietary purity to the neglect of other spheres of one’s life – in the way that many vegans are – is to contradict a care about harms to animals. With this care given, what matters is lowering the level of harm to animals, regardless of how this harm is done.

This article was republished with permission from the Journal of Practical Ethics.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships, Society + Culture

Look at this: the power of women taking nude selfies

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Climate + Environment

Blindness and seeing

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Politics + Human Rights

Don’t throw the birth plan out with the birth water!

Opinion + Analysis

Climate + Environment, Politics + Human Rights

Increase or reduce immigration? Recommended reads

BY XAVIER COHEN

Oxford student Xavier Cohen, was one of the two finalists in the undergraduate category of the inaugural Oxford Uehiro Prize in Practical Ethics.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

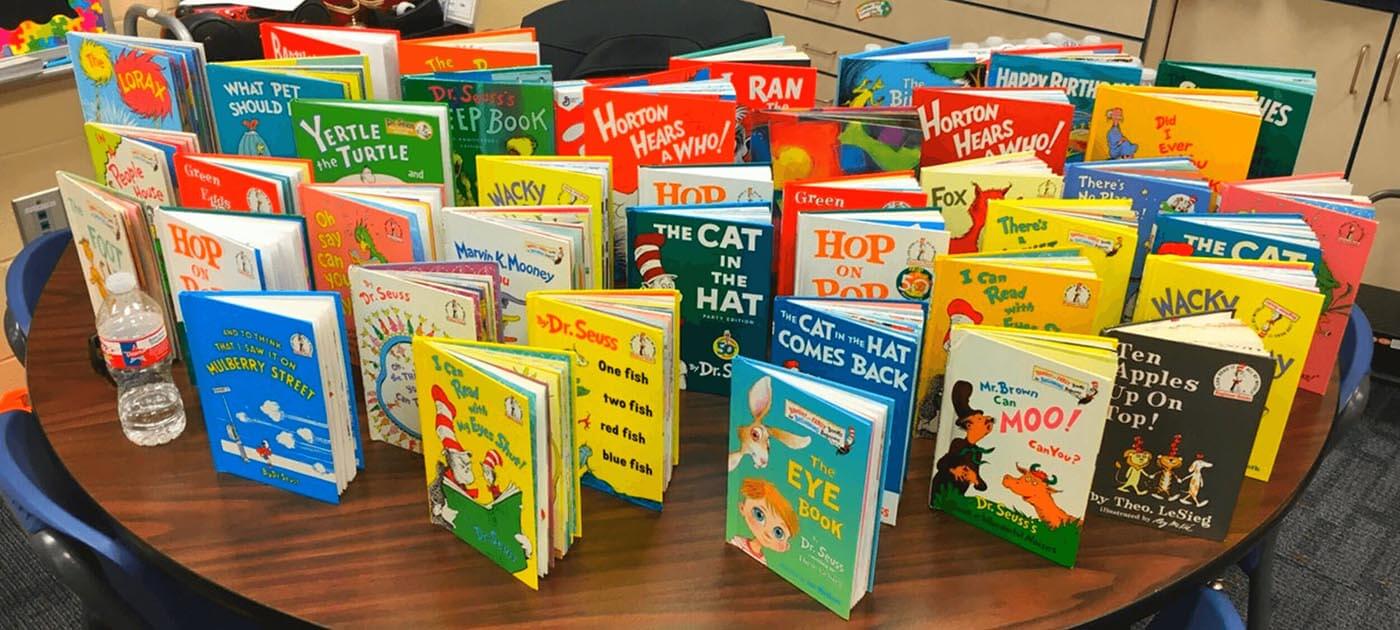

You can’t save the planet. But Dr. Seuss and your kids can.

You can’t save the planet. But Dr. Seuss and your kids can.

Opinion + AnalysisClimate + EnvironmentRelationships

BY Steve Vanderheiden The Ethics Centre 30 SEP 2015

Dr. Seuss’ The Lorax explores the consequences of deforestation and the environmental costs of development. It concludes with the Once-ler, the narrator of the story who is principally responsible for deforestation of the decimated Truffula tree, entrusting its final seed to a young boy. He implores the child, “Grow a forest. Protect it from axes that hack. Then the Lorax and all of his friends might come back.”

The Once-ler, wracked by guilt for his complicity in this environmental disaster, passes along responsibility for reversing damage done by his generation to a child. The Lorax suggests the young take on duties of planetary stewardship where adults have failed.

Is this fair? Perhaps the generation responsible for mucking up the planet has lost its moral authority to try and save it. So the task of conservation is inherited by those with a longer-term stake in its future.

That adults might vest hope for a better planet in our children is both edifying and deeply troubling. Edifying because the environmental record of the world’s children bests that of adults by default. The young have not yet begun to reproduce the patterns of behavior that implicate their parents – resource depletion, biodiversity loss, climate change…

Troubling because they may reproduce them in future. We cannot realistically expect young people socialised into a world of willful environmental neglect to behave much differently than their parents have. Adults cannot so easily absolve themselves of the responsibility of addressing environmental harm they have caused.

Rather than saving the planet, a more modest objective might be to refrain from making it much worse for our children. Even this is a daunting prospect. Patterns of energy use dependent on fossil fuels all but guarantee that global temperatures will continue to rise. For most, climate change is no longer a debate about “if” but “how severe?”

We may still hope to make the planet better for our children in other ways. For instance, by adding to the richness of human culture and the stock of beneficial technologies. When it comes to climate though, a more appropriate aim might be to refrain from chopping that last Truffula tree. To preserve our remaining forests so our children might be able to see the proverbial Brown Bar-ba-loots, Swomee-Swans or Humming Fish in their native habitats rather than natural history museums.

Doing this will be challenging. It will require an often uncomfortable reflection on what drives global environmental degradation. In Seuss’ tale the insatiable demand for thneeds – the ultimate commodity – drives the Truffula deforestation. This implicates our heedless consumerism in the causal chain of degradation alongside the Once-ler.

When we consume things we don’t need, and when the industry around these commodities is obviously unsustainable despite our obliviousness to this fact, we contribute to resource depletion. What’s more, we add to the attitudes and norms that suggest this is a private matter, answerable only to private consumer preferences and not larger public concerns for equity or sustainability.

Worst of all, we teach our children to do the same.

The first step in reducing our negative impact upon the planet must be to understand how and where we make the impact we do. We need to understand alternatives that yield comparable value to us with a lighter toll upon the planet. Consuming more conscientiously will leave our children a better planet and make them better citizens of it. Though it requires us to consume differently and less.

Thinking about the long-term consequences of our choices will also help. We cannot plausibly claim to value our children’s future while discounting the future value of current investments in sustainable infrastructure or future costs of unsustainable current practices.

To help make better children for our planet we must teach them that out of sight is not out of mind.

Our deeds announce our concern for the welfare of future generations more accurately than our words or thoughts. Thinking about such choices must be accompanied by some changes in course. Citizens must demand better public choices be made rather than acquiescing to worse ones as unavoidable products of political inertia or inviolable market forces.

The tendency to shift problems across borders is no less insidious than passing them to our children or grandchildren. To help make better children for our planet we must teach them that out of sight is not out of mind.

As role models for our children our success in stopping environmental harm will matter less than our sincerity in the efforts we make. If we honestly try to maintain the planet, our example will help make them into the kind of people our planet needs.

For as the Once-ler interprets the Lorax’s cryptic final word, “UNLESS someone like you cares a whole awful lot, nothing is going to get better. It’s not.”

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships

There’s no good reason to keep women off the front lines

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

Breakdowns and breakups: Euphoria and the moral responsibility of artists

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

What ethics should athletes live by?

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

How to pick a good friend

BY Steve Vanderheiden

Steve Vanderheiden is Associate Professor of Political Science and Environmental Studies at University of Colorado Boulder and Professorial Fellow with the Centre for Applied Philosophy and Public Ethics (CAPPE) at Charles Sturt University.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Flaky arguments for shark culling lack bite

Flaky arguments for shark culling lack bite

Opinion + AnalysisClimate + Environment

BY Clive Phillips The Ethics Centre 10 SEP 2015

Culling sharks is unnecessarily harmful, disproportionate and will do little to protect humans.

The question of whether we should protect humans by culling sharks is not new. There are many parallels to the problems posed by land-based apex predators such as lions and tigers. The solutions we have adopted on land – including widespread culling – are unlikely to be either ethical or effective in dealing with shark attacks.

We must consider whether sharks offer humans indirect benefits. For example, sharks help control the seal population, which eats the fish we rely on for food and trade. Last winter, fishermen called for seal culls in South Australia because of the healthy fur seal population there.

People enjoy observing sharks in the ocean either directly through “shark tourism” or on TV. Discovery Channel’s “Shark Week” has become a cultural phenomenon in many nations. Apex predators hold a certain fascination – we marvel at their control of their territory. The awe we feel when viewing sharks is itself an indirect, unquantifiable benefit.

Even if these indirect benefits did not outweigh the risks to swimmers and surfers, this alone would not justify culling. We would have to consider whether the harms involved in controlling sharks are greater than the harms shark attacks cause to humans.

The numbers of sharks we would need to control for effective protection far exceeds the number of humans who benefit from controlling shark populations. Less aggressive forms of land-based controls for apex predators – for example, excluding lions from agricultural areas – are unlikely to work in the marine environment.

The numbers of sharks we would need to control for effective protection far exceeds the number of humans who benefit from controlling shark populations.

The practical outcome of this means many more sharks are killed than humans. In Queensland alone, about 700 sharks die per year in the culling program. By comparison, only one human has been killed – in an unbaited region.

In addition, baiting – a key tactic in the culling process – generates unintended harms such as “bycatching”. Baiting works on more than just sharks. It also lures turtles, whales and dolphins, which pose no threat to anyone. They are collateral damage in the war against sharks.

Netting beaches has been presented as a viable alternative to culling but here too there is risk of bycatch. Furthermore, netting leaves sharks to suffer and die slowly, giving rise to another raft of ethical concerns.

If culling is to be justifiable we need to consider the steps being taken to minimise shark suffering. Sharks captured on baited hooks suffer extensively, even when patrols detect and shoot injured sharks.

Let us suppose we could eventually devise ways of effectively stopping sharks entering the littoral zone by culling them in a way that minimised suffering. We would still have to consider the desirability of interfering in this way.

The long-term ethical consequences of destroying or reducing the population of an apex predator are considerable. The absence of apex predators in Australia has allowed an enormous kangaroo population to thrive. This population has had to be culled due to the competition they pose to domestic herbivores.

What’s more, the huge population means kangaroos face widespread starvation during droughts. The existence of apex predators may be bad for those caught in their path, but it is good for the entire ecosystem.

Human culling works contrary to the ‘natural’ culling apex predators perform. While predators prey on the weak and elderly, human culling targets the fittest or those with others dependent on them. As such it challenges the continuity of the entire species.

Many will argue that sharks have a right to occupy the territory in which they have evolved over millions of years, and this trumps the alleged right of humans to use territory they are ill-suited to and gain little significant benefit from. Certainly, many surfers respect these rights – acknowledging sharks as fellows in the ocean rather than threats or enemies.

The shark cull may in fact be exacerbating the shark problem in a cruel and ironic circle.

The sharks’ rights are enshrined in our law. Great Whites are an endangered species and therefore enjoy legal protection. Given the legal status sharks enjoy, the benefits to humans would have to be especially high to justify culling as an ethical option.

Surfers can adopt another sport if they are unwilling to assume the risk of shark attacks – and many are. This is particularly true if they are unwilling to explore cheaper, more reasonable ways of protecting themselves.

The shark cull may in fact be exacerbating the shark problem in a cruel and ironic circle. Sharks may be driven to attack humans because of the damage we have done to their environment. Shark experts argue that injured sharks on baited hooks attract other sharks to the area.

The elimination of apex predators such as Great Whites destroys millions of years of evolutionary adaptation. The ethical risks and costs of controlling the environment in this way are rarely contemplated in the face of tragic but rare fatal attacks. Instead of balanced reflection, we see knee-jerk responses that fail to adequately address the broad range of ethical issues.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Climate + Environment, Relationships

Care is a relationship: Exploring climate distress and what it means for place, self and community

Explainer

Business + Leadership, Climate + Environment

Ethics Explainer: Ownership

Opinion + Analysis

Climate + Environment, Health + Wellbeing

How should vegans live?

Big thinker

Climate + Environment