We’re in this together: The ethics of cooperation in climate action and rural industry

We’re in this together: The ethics of cooperation in climate action and rural industry

Opinion + AnalysisClimate + EnvironmentBusiness + Leadership

BY Cris Parker 14 APR 2025

“We’re in this together” is easy to say, but much harder to do – especially when people’s livelihoods, land, and the planet’s future are at stake.

Australia is committed to reducing emissions and shifting to renewable energy. However, for many rural and regional communities – particularly those tied to coal, gas, or agriculture, they sit at the crossroads of opportunity and uncertainty. These areas are rich in culture, industry, and community and are also heavily shaped by commercial imperatives – the need for jobs, services, and sustainable growth.

Unfortunately, climate action can feel more like an impending threat than a shared opportunity. These communities often experience change as something done to them, rather than with them.

Bridging this gap demands more than just policy and technology. Climate change is one of the biggest challenges of our time, but tackling it isn’t just about switching to solar panels or building wind farms either. It’s about ethical cooperation – a commitment to fairness, transparency, and shared responsibility in how we plan and implement climate solutions. If not done ethically, commercial development can disrupt local culture, raise living costs, and put pressure on fragile ecosystems.

At its heart, cooperation is about shared goals. But in climate policy, those goals don’t always look the same to everyone. For city campaigners, a ‘just transition’ means phasing out coal and gas. For a local worker in Gladstone or the Hunter Valley, it might sound like job losses without a safety-net.

Different philosophical perspectives can help us to understand how we can apply ethical cooperation as we pursue our shared goals. Whether it’s about consequences, duties and obligations, or people’s rights, all are underpinned with the values and principles of transparency, fairness, and mutual respect and dignity.

‘Just transition’ sounds good, but what does it mean in practice? As researchers Marshall and Pearce put it: “Many people in regional communities have no concrete understanding as to what a ‘just transition’ refers to and do not find it to be authentically their syntax”.

The proposed Hunter Transmission Project in NSW, for example, has been met with strong resistance from landowners. While the project is intended to support clean energy infrastructure, many locals say the process lacked transparency and ignored community concerns about land use, agriculture, and environmental impacts.

British philosopher Onora O’Neill focuses on trust and consent in cooperative systems. She argues that ethical cooperation requires conditions where all parties have genuine capacity to consent, particularly in asymmetrical relationships (e.g. government vs local communities). These principles have been embedded in The Clean Energy Council’s national guide which advises that developers must prioritise “clear, accessible and accurate information” and ensure projects are co-designed with communities to reflect cultural, economic and environmental priorities.

When AGL closed Liddell Power Station in 2023, the company committed to a transition plan. But many workers reported uncertainty and a lack of clarity about what would come next. For a transition to be truly ‘just’, it needs to include more than retraining promises. It needs local job pipelines, early engagement, and co-designed solutions.

Israeli philosopher Yotam Lurie says that once people engage in joint activity, they take on moral obligations to each other. In the case of climate action, that means governments, industries and communities must not only work together, but they must also do so with care, trust, and respect.

Rural resistance often stems from real economic vulnerabilities and perceived exclusion from decision-making, not from climate denial.

Encouragingly there are areas where we are seeing ethical cooperation working well.

In Gippsland, Victoria, the Gunaikurnai people are working with renewable energy developers to co-design solar projects. These partnerships embed cultural knowledge, ensure local employment, and protect Country showing that ethical cooperation isn’t just a principle. It’s a practical strategy for success.

The First Nations Clean Energy Network has also shown how co-owned and co-designed projects can reduce costs, build trust, and deliver long-term economic and environmental benefits.

Climate change is often framed as a technical problem. But it’s also a human one. If we want a sustainable future, we must build it together with ethics, empathy, and equity at the centre.

As Australian philosopher, Peter Singer suggests, we are morally obligated to reduce the suffering of others which would support a coordinated action where affluent corporations aid vulnerable groups, such as rural or Indigenous communities affected by the energy transition.

Governments and companies have a responsibility to fund and support this process. That includes advisory boards, transparent impact assessments, and long-term partnerships built on trust.

If we want rural and regional communities to lead rather than lag in the net-zero transition, we need to take ethical cooperation seriously and build trust within the human system. Sometimes the hardest part is putting aside self-interest, regardless of the good intent and work together to understand the shared purpose. Acknowledging the tensions and being honest about the trade-offs is a strong place to start. This can be done through deep listening and ‘story telling’ that demonstrates respect for cultural and ecological values, rather than just economic ones.

Tackling climate change is not just about reducing emissions, it’s about justice and fairness, because “we’re in this together” only works when everyone has a say, and everyone has a stake.

The Energy Charter is a member of the Ethics Alliance and a one-of-a-kind, CEO-led coalition of energy organisations united by a shared passion and purpose: delivering for customers and empowering communities in the energy transition.

BY Cris Parker

Cris Parker is Head of The Ethics Alliance and a Director of the Banking and Finance Oath.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

The dark side of the Australian workplace

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

The near and far enemies of organisational culture

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

6 Myths about diversity for employers to watch

Opinion + Analysis

Climate + Environment, Politics + Human Rights, Relationships, Society + Culture

The youth are rising. Will we listen?

7 thinkers improving our ethical understanding of the environment

7 thinkers improving our ethical understanding of the environment

Big thinkerClimate + Environment

BY Cameryn Cass 5 JUN 2024

Despite centuries of advocacy urging us to consider our actions, the urgent problem of climate change and conservation of our earth is one that often feels the most insurmountable.

In celebration of World Environmental Day, these seven key thinkers and activists from across history have contributed to our ethical understanding of the environment and how we can lessen our impact.

Aldo Leopold (1887-1948)

Aldo Leopold was a conservationist, forester, philosopher, and educator who dedicated his life to coexisting with nature and learning from it, with many considering him to be the father of American wildlife ecology.

His non-fiction book, A Sand County Almanac, calls for the development of a land ethic, as conservation is unachievable so long as resources are controlled by economic interests. He wrote, “a land ethic changes the role of Homo sapiens from conqueror of the land-community to plain member and citizen of it.” By including land in our understanding of community, it no longer is property; instead, it becomes inherently valuable and, in turn, worthy of protection and respect. “We can be ethical only in relation to something we can see, feel, understand, love, or otherwise have faith in,” he wrote.

Leopold additionally stressed the need to evaluate and update the content of our conservation education. He said it’s not enough to join a few organisations, follow the law, and trust the government will do the rest. “In our attempt to make conservation easy, we have made it trivial.”

Seyyed Hossein Nasr (1933-present)

Nasr, an internationally celebrated thinker from Iran, is, at present, a professor of Islamic Studies at George Washington University. He looks at the natural world through a religious lens, thus becoming the founder of environmentalism in the Muslim world. He calls Islam a “green religion,” as it’s easy for followers to sympathise with the natural world, since “the Qur’an addresses not only human beings, but also the cosmos. All creatures participate in Islam.” In Islam, all living things are equally valuable, equally deserving of life, equally valid. Nasr highlights how “we human beings cannot be happy without the happiness of the rest of creation. We have killed enough, massacred enough of God’s other creatures.”

He juxtaposes Islamic values with Christian ones, and how the latter’s “most devout followers don’t show much interest in the environment.” In all the verses of the New Testament, he points out, there’s not one mention of nature. “To be modern is to destroy the world of nature. That’s the great tragedy of it, and we should try to find out why.”

Naomi Klein (1970-present)

As a Canadian journalist, filmmaker, New York Times best-selling author and professor of climate justice, Naomi Klein’s commitment to activism spans many mediums, across borders. She sees our world’s current state as one major, interconnected problem: Climate change isn’t separate from medical crises which aren’t separate from political crises, and so on. In her eyes, it’s all connected and it all rests on the initial sin of stealing lands from Indigenous people.

In her Festival of Dangerous Ideas 2015 talk, Capitalism and the Climate, she emphasised the Pope’s idea of a “throwaway culture.” It’s what’s allowed generations of Australians, Canadians, and Americans alike to take from Native people, and it’s the same concept that’s degrading and destroying our planet. “We extract and do not replenish and wonder where the fish have disappeared. And why the soil requires evermore inputs, like phosphates, to stay fertile.” Klein calls for the creation of a “culture of caretaking in which no one and nowhere is thrown away. In which the inherent value of people and all life is foundational.”

Tyson Yunkaporta (present)

Aboriginal people have lived in Australia for over 65,000 years – far longer than any other humans have anywhere else on the planet. Tyson Yunkaporta, an Aboriginal scholar and author, believes that we stand to resolve a lot of our current environmental problems by turning to their ancient practices, or, at the very least, considering them. Aboriginal “patterns still flow with the movement of the earth.” They remain connected to the planet, he said, living in harmony and coexisting with the natural world in ways non-Indigenous people do not.

Yunkaporta thus encourages readers to question Western thinking and approach problems with an Aboriginal lens instead. As he wrote in his book, Sand Talk, we ought “to live and work in accordance with a natural order, rather than against it.”

Pythagoras (570 BC-495 BC)

Though Pythagoras is typically remembered for his contribution to mathematics (you might remember his famed Pythagorean Theorem from high school math class) he was actually better known for his beliefs on reincarnation and diet in his day. In fact, he was the first modern vegetarian in the West and is regarded as the father of ethical vegetarianism.

While the actual impact of cutting out meat from one’s diet is often disputed, individuals can have impact by lessening their own ecological footprint. By cutting out meat, it can be argued that one stands to dramatically reduce the resources – like land, water, and oil – required to sustain their diet. Pythagoras far predated these ecological footprint considerations; instead, he grounded his vegetarian beliefs in reincarnation. By killing animals and eating their meat, he said, we run the risk of eating our companions. “Meat is for beasts to feed on… what a wicked thing it is for flesh to be the tomb of flesh… for one live creature to continue living through one live creature’s death.”

Vandana Shiva (1952-present)

Vandana Shiva is an ecofeminist, physicist, ecologist, activist, editor, and author known for her steadfast commitment to work in environmental conservation, specifically agriculture. Famously, she opposed Asia’s Green Revolution, which, while ramping up food production in less-developed countries, the heavy use of pesticides harmed native seed diversity and traditional agricultural practices.

To try and do her part to give back, in 1982, Shiva founded the Research Foundation for Science, Technology, and Ecology to develop sustainable agricultural practices. In her Festival of Dangerous Ideas talk in 2013, Growth = Poverty, she condemns GDP and growth, drawing on experiences from life in India. Gross Domestic Product, she says, doesn’t account for things like pollution in the rivers, and if it did, India and China would have negative scores. Instead, it creates a false standard of living and, in doing so, “it has perpetuated a model of generating non-sustainability, inequality, and a deep violence within society and within the self.”

Kongqiu (551 BC-479 BC)

Better known as Confucius, this ancient Chinese philosopher’s teachings are, to this day, the bedrock of East Asian culture.

Confucius believed that all life has qi, which is essentially life force that nurtures humans and nature alike. In essence, qi supports the idea that humans and nature are isogenous, of the same origin and interconnected. In accordance with this perspective, Confucius stressed that humans ought to be kind to the land to achieve harmony and balance.

Present day scholars look to this ancient Chinese wisdom as a piece to solving the puzzle that is climate change. If humans adopted the idea that we are not separate from nature and instead an extension of it, as Confucius said, then perhaps we’d see this destruction to the land as destruction to ourselves and finally change our unsustainable ways.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Climate + Environment, Science + Technology

The kiss of death: energy policies keep killing our PMs

Opinion + Analysis

Climate + Environment, Politics + Human Rights, Relationships, Society + Culture

The youth are rising. Will we listen?

Opinion + Analysis

Climate + Environment, Science + Technology

Space: the final ethical frontier

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Climate + Environment

Blindness and seeing

BY Cameryn Cass

Cameryn Cass is a curious writer and an editor-in-training who studied at Michigan State University. Her primary focus is environmental storytelling, as she deeply loves the natural world and intends to use her voice to defend it. Outside of work, she loves to hike, rock climb and practice yoga.

What we owe each other: Intergenerational and intertemporal justice

What we owe each other: Intergenerational and intertemporal justice

Opinion + AnalysisPolitics + Human RightsClimate + Environment

BY Pia Curran 3 MAY 2024

According to the United Nations, the global population will increase by two billion over the next thirty years. This gives the idea of intergenerational justice particular weight. But philosophers struggle to discern the existence, nature and extent of any moral duty owed to future generations.

Issues of remoteness, non-identity, and economics leave many fixed in the parochialism of the present. Using British philosopher, Derek Parfit’s ‘person-affecting principle’ and the threshold notion of harm to argue that current generations do owe a moral duty to their heirs, existential threats to present and future people, such as climate change, should be dealt with through a pragmatic, sociological focus on distributive justice, encouraging a reinterpretation of justice as inter-temporal.

Relations between generations are ‘relations of domination’. Future people either have not come into existence, or they are too young to access the full rights of a democratic citizen. For some, this belies a ‘moral imperative to give voice to the voiceless’. Others resist giving ethical considerations to non-specific, non-existent things, and the future consequences of our actions are not certain. Indeed, future generations have not done anything to warrant our consideration, so obligations must come from some intrinsic value placed on human life.

Israeli political scientist, Avner de-Shalit suggests the existence of a ‘transgenerational community’ to which we owe a duty because we share ‘cultural interaction and moral similarity’. But deciphering how far into time this community stretches is difficult, and de-Shalit does not adequately address the different levels of obligation felt towards today’s youth and remote future people, with whom it is difficult to feel part of a community.

A more convincing argument is Derek Parfit’s ‘person-affecting principle,’ the ‘fundamental ethical requirement that humans have an obligation not to affirmatively harm a person.’

If everyone should be treated with respect and dignity no matter when they are born, we ought not to make decisions that will cause harm to future persons.

This deontological position is strengthened when considering an adaptation of Australian philosopher Peter Singer’s classic thought experiment. If it is equally important for an adult in Nepal who sees a drowning child to save the child as it is for you to save a drowning child in front of you, then spatial distance must be irrelevant to moral responsibility to prevent harm. By extension, why should temporal distance be any different? Tensions surrounding the personhood of the unborn should not keep present people from refraining from acts that will harm the interests of future people, whether or not they actually come into existence.

But Parfit does not define the meaning of ‘harm’, nor what level of care is owed to future generations. If a policy is criticised because it is predicted to worsen future standards of living, it could be said that all actions have some consequence for the lives of future people. If the act results in certain people not coming into existence, they cannot really be said to have been ‘harmed’ by the policy, because they never became a person.

Defining ‘harm’ through the notion of the threshold abates this problem. It does not require individuals to be worse off at a point in time than they otherwise would had a harmful act not been performed, only that they are worse off than they ought to be. Individuals are harmed if they come into existence in a sub-threshold state. This extends the notion of moral responsibility and intrinsic rights across time so that, ‘no child should do worse than some minimum standard that is determined by reference to the entire society,’ taking basic requirements such as food, water and shelter as a given.

Determining this threshold, however, is difficult. Buchanan suggests ‘better than our current median’ as an antidote to ‘better than me,’ because this acknowledges intragenerational disadvantage. The economic practice of ‘discounting’ the future, by contrast, entails a willingness to act on a preference for current generations. This discount rate ‘dramatically diminishes the significance of policy effects on future generations.’

The issue then becomes one of balance. How do we balance our obligations not to inflict harm on ourselves, and the sometimes competing aim to not inflict harm on future individuals? Focusing on fiscal policy, Buchanan suggests a focus on ‘distributive justice,’ pressing the need to weigh all claims and redistribute resources away from the ‘richest’ to the ‘poorest,’ irrespective of when those people may be alive. For example, higher taxation for the rich and more investment in welfare and public infrastructure of the future. The aim is to reach a level of wellbeing ‘according to which both currently and future living people are able to reach a sufficientarian threshold.’

Issues posing existential threats to present and future people have a particular moral primary in terms of harms to avoid. Climate change, especially rising global temperatures, poses irreversible and universal damage. Using the threshold concept of harm, one assumes that future generations ought to live in a clean and safe environment, and current generations ought to act in ways that avoid environmental degradation. But, given that sustainable energy is more expensive than fossil fuels, there exists a tension between economic growth and ecological protection.

Irish sociology lecturer, Tracey Skillington takes a sociological rather than philosophical approach, arguing that ‘the needs of the capitalist present have taken precedence over all other concerns,’ noting the insufficient efforts taken to prevent environmental harm. If all focus is on present concerns, justice is not equitably distributed to the future. Skillington sees this as a flaw in the present liberal-democratic political infrastructure.

Youth are taking legal action against governments to assert their right to inherit a safe environment. In Australia, a temporarily-established common law duty of care to protect young people from climate change was reversed by the Full Bench of the Federal Court. It held that the previous judge’s reasoning was too expansive and endorsed an analysis based only on narrow legal principles of negligence. This view does not consider that intergenerational issues arise slowly, and legal justice should be interpreted in a manner that extends beyond the political and economic realities of the present if we are to prevent harm to future generations.

Scottish philosopher, William MacAskill’s ‘longtermism’ encourages a broader gaze, asking politicians to see beyond the short term reality of a carbon economy to universal and inalienable collective rights. This ‘intertemporal’ approach to justice and the role of institutions recognises humanity as bound not only by biology, but ‘shared ecological resources and a common cosmopolitan project as well’. Through national and international cooperation, current generations can minimise harm by creating a threshold state that satisfies the right to a safe environment and equitably distributes justice between present economics and future longevity.

The notion that future generations can suffer harm at the hands of present policies creates a moral obligation to avoid acts that ensue a sub-threshold state. This state is determined by reference to the society as a whole, but as a minimum can be expected to include basic necessities such as a clean environment. Democratic institutions should adjust their gaze when formulating policy, recognising long-term implications and understanding justice as a concept that exists across and between time.

‘What we owe each other: Intergenerational and intertemporal justice‘ by Pia Curran is one of the Highly Commended essays in our Young Writers’ Competition. Find out more about the competition here.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Big thinker

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Big Thinker: Germaine Greer

Explainer

Politics + Human Rights

Ethics Explainer: Ethics, morality & law

WATCH

Politics + Human Rights

James C. Hathaway on the refugee convention

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships, Society + Culture

Of what does the machine dream? The Wire and collectivism

BY Pia Curran

Pia studies Arts and Advanced Studies at the University of Sydney, majoring in English and History. She is passionate about the value of humanities and philosophy and their pertinence to public policy. In her spare time she enjoys reading and creative writing and hopes to one day publish her own collection of essays or short stories.

Blindness and seeing

‘Anyone who says that life matters less to animals than it does to us has not held in his hands an animal fighting for its life’. Elizabeth Costello, from J. M. Coetzee’s The Lives of Animals

‘Don’t think, but look!’ – Ludwig Wittgenstein, Philosophical Investigations

Philosophical debates about animal welfare can appear abstruse. Much scholarly ink has been spilt over whether animals possess the requisite features—an interest in the future, an ability to suffer, a mind—that would ground our duties towards them. I wonder, however, if theoretical arguments of this sort really do justice to the issue at hand, which seems not so much a matter of moral disagreement as a radical difference in ways of seeing. What for the animal rights activist is a mechanised holocaust of unconscionable scale is for the meat-eater an institution that betters their well-being. The most pressing issue, as I see it, is not whether animals have rights, but whether we are able to see them at all as fellow creatures inhabiting the same world and sharing our vulnerabilities.

In J.M. Coetzee’s novella, The Lives of Animals, the elderly novelist Elizabeth Costello is invited to give an address at Appleton College. Her chosen theme being on our treatment of animals, she prefaces her lecture by exhibiting what she calls a ‘wound’: a scar from being exposed to the haunting nature of our treatment of animals, of being surrounded by well-meaning human beings who remain bewildering blind to the atrocities she alone perceives.

Throughout the novella, Costello discusses and answers arguments but never as the theorising philosopher. When an opponent suggests that life and death cannot be to animals, who lack a sense of identity, what it is to us, she responds by the line quoted in the epigraph of this piece, that whoever would say so has not held in their hands an animal fighting for its life, a line which I find stunning. Never mind our favoured theory of the mind, can’t you see it is suffering?

Here is an affirmation of our exposure to the suffering of animals, an involuntary confrontation, before which what is called upon is not our reason but an anguished response that is a testament to our humanity. Costello is not a vegetarian out of moral convictions; instead, she insists ‘“it comes out of a desire to save my soul”’– out of a vivid awareness of her exposure. There is a sense in which any attempt at philosophising inevitably ends up deflecting us away from that immediate reality, the animals in our hands.

Costello provocatively compares the meat industry to the Holocaust. Her point, I take it, is linked to what Stanley Cavell has called ‘soul blindness’: a failure to see another human as human. Primo Levi, in his Survival in Auschwitz, vividly recalls the look from a Nazi examiner, which ‘came as if across the glass window of an aquarium between two beings who live in different worlds’. What we find so accursed about the examiner, I think, is not his false moral beliefs – rather, there seems to us a critical defect in their sensibility, a blindness to humanity which stings.

We find another illustration of ‘soul blindness’ in the film Blade Runner, which imagines a world where human-like ‘replicants’ are mass-produced and enslaved, and those who escape are tracked down.

At first pass, we might see Blade Runner as a film noir exploring the boundary between humans and intelligent replicants; yet when we realise that the replicants, who can think, feel, and interact exactly like humans, are perhaps denied moral status only by the technical stipulation that ‘humans’ are those with a specific biology, the film takes on a more sinister meaning. In particular, it might shock us with how easily we become blinded to the living humanity of another, when some abstract, in hindsight irrelevant pieces of information are introduced – ‘They do not have DNA’; or ‘They are a Jew’.

Animal rights activists often point to the difference in our treatment of pets and those whom we eat for meat; but rather than dismissing it as a sign of our irrationality, if not hypocrisy, the datum ought to be probed further. What is different is a way of seeing: the pets are companions, family members, whom we acknowledge as fellow creatures, while the pigs are just food.

Many times I have felt deeply perturbed, flipping through an illustrated children’s book, when I saw the image of a smiling pig with just the right amount of anthropomorphism that it looks uncanny. Those are eyes which I do not dare meet. The knowledge inside those images, that a pig is also a being capable of feelings and suffering, is knowledge too terrible to bear – we have been raised to suppress it. If he could explain the examiner’s look, Levi tells us, he would also have explained the insanity of the Third Reich. We might make a parallel statement about animals: if one could explain the way we look upon animals as mere food and not living creatures like us, then one would also have explained our treatment of animals.

Here is what I think the three cases – our treatment of animals, the Holocaust, and the enslavement of replicants – have in common: drawing on an idea of Simone Weil, they are issues on a separate moral plane from those to be afforded intellectualised debate. We could argue about why slavery is wrong, but we should not argue over if it is wrong. I am not saying that we should give up persuasion and begin accusing each other of the monstrosity of eating meat; rather, what I claim is that abstract disputes over rights and permissions seriously misrepresent the moral terrain.

Levi remarks that one of the things the camp taught him was ‘how vain is the myth of original equality among men’. What use is there of a theory of human rights if the abuser does not see you as a human at all? This is why Costello appeals not to philosophy, but to imagination and poetry: a chasm of sensibility can only be bridged by changes in the way of seeing. And why should our response to animals be out of a sense of duty? Often, the more humane response may well be one out of kindness and a sense of fellowship.

In today’s world, our blindness to each other’s humanity is unfortunately still all too prevalent – the images that emerge from recent conflicts confirm it. One could say, however, that our blindness to the suffering of animals is just as distressing. What is most frightening is perhaps not that we come up with the wrong moral beliefs, but that we lose the ability to see animals, and other humans, as fellow beings who are like us.

‘Blindness and seeing‘ by David He is one of the Highly Commended essays in our Young Writers’ Competition. Find out more about the competition here.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

Where are the victims? The ethics of true crime

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Why morality must evolve

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

A parade of vices: Which Succession horror story are you?

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

We can help older Australians by asking them for help

BY David He

David is a pure mathematics honours student at the University of Sydney, having completed double majors in mathematics and philosophy there. In his free time he likes to read and play Go, a board game. He aspires to become a mathematician and/or a writer someday.

Gen Z and eco-existentialism: A cigarette at the end of the world

Gen Z and eco-existentialism: A cigarette at the end of the world

Opinion + AnalysisClimate + EnvironmentHealth + Wellbeing

BY Layla Zak-Volpato 12 FEB 2024

“Where ignorance is bliss, tis folly to be wise.” – Thomas Grey

Gen Z live inside of an hourglass. The sand leaks steadily from underneath our feet at an imperceptible rate so that we don’t realise the ground is slipping away until we are plummeting toward the bottleneck. The 21st century has been characterised by the impending, seemingly unstoppable doom of climate change and ecosystem collapse. There is a rising epidemic amongst young people of feelings of anxiety and dread towards a future made uncertain by global warming. This sensation, the drop in the pit of our stomachs from a fall that doesn’t seem to be ending, has caused mixed reactions amongst Gen Z. While those who use sustainability as an antidote to their anxiety are praised, others who appear to act in complete denial of climate change are frequently vilified. Young people who smoke cigarettes and partake in fast fashion appear to show blatant disregard for the impact of their actions on the climate.

Unethical behaviours amongst young people are often attributed to delinquency and delayed cognitive development. While, in some cases, this may be true, the impact of climate change on moral decision-making in today’s youth is often overlooked. Gen Z hold the heavy responsibility of reversing the catastrophic impacts of climate change. As such, partaking in activities that cause both physical and environmental damage may stem from an attitude of wilful ignorance that allows young people to feel momentary freedom from this burden. With a reputation as one of the most climate-conscious generations,

Gen Z is often held to high moral standards regarding social and environmental issues. These standards make very little allowance for complex reactions to climate change that may appear to older generations as apathy. Subsequently, young people are owed a greater deal of compassion and understanding from older generations for their reactions to this unimaginable catastrophe.

Young people of the 21st century appear to be both driving and abating the effects of climate change. Some of the world’s most passionate and radical anti-climate change organisations have been spearheaded by Gen Z – reflecting their climate-consciousness. Yet, paradoxically, young people are the biggest users of disposable vapes and are frequent patrons of fast fashion giants. It’s an easy conclusion to draw that these behaviours (in a time of rampant climate change) seem to reflect opposing ideologies at best and a lack of general empathy at worst. In an article for the online publication Refinery29, ‘Gen Z & the fast fashion paradox’, Fedora Abu describes young people as “environmentally engaged yet seduced by what’s new and ‘now’”.

This attitude represents an oversimplification of the mental and ethical impacts of climate change on young people. Abu depicts Gen Z as a generation whose ethical and moral beliefs are easily corrupted by consumerism-driven desire. Many adults are quick to overlook the extreme mental load felt by Gen Z toward climate change and the emotional maturity that lends itself to this responsibility. Amongst young people, there has been a notable rise in feelings of eco-anxiety – described by the American Psychological Society as a “chronic fear of environmental doom”. Climate-related mental health issues manifest themselves through trauma, shock, substance abuse and depression.

In an online article published by the University of Melbourne about the rise of climate anxiety amongst young people, recommendations to relieve negative emotions include partaking in sustainable consumption (recycling, picking up rubbish etc.) and becoming involved in environmental campaigns. While there is no doubt that sustainable consumption and activism are positive, they may not adequately alleviate the anxiety felt by some young people. Those who structure their lives around sustainability and those who indulge in unsustainable practices may seem like opposing forces; they are, in fact, two sides of the same highly anxious, existential coin – both equally valid reactions to a sense of disillusionment with 21st-century adulthood.

Young people adopted their expectations of adulthood from the media they consumed as children. However, within a rapidly changing world, many feel a sense of disconnect with an experience of adulthood characterised by climate anxiety. Essentially, there’s a resounding sense that we haven’t gotten what was promised. As a child, my mother and I spent our bonding time in front of the TV – together she shared with me the television shows and movies that characterised her childhood and early adulthood. Before I was old enough to recognise it, the formulaic American sitcoms of the 90s and grand, romantic flicks of the 80s (often accompanied by a soundtrack of synth-heavy ballads) had begun to construct my worldview.

Watched in retrospect and with the use of a fully developed brain, however, one aspect is glaringly missing from the portrayal of adulthood presented by the media that raised us – the omnipresent threat of climate change. While only linear time is to blame for the fact that media from the past can’t represent our current reality, there is a sense of cognitive dissonance amongst young people between the future we were raised to expect, and the way adulthood has unfolded before us. For young people, the rampant, mindless consumerism of the 80’s and 90’s appears like a neon-lit mirage. The increased uptake of sustainable practices by large corporations is a movement of the 21st century. As such, many young people have rarely made a purchase without considering the environment.

For older generations, sustainability may provide feelings of empowerment and agency against the overwhelming monolith of climate change. However, sustainable living requires a significant amount of intentional thought against habitual, unsustainable habits built over generations. Within the domestic space, in particular, adopting sustainable approaches such as ‘zero waste’ living requires a significant mental load – the often invisible responsibilities of management and organisation. Whilst young people are rarely the organisers of large households, I believe a similar burden is felt towards sustainable consumerism.

Sustainable consumerism is often denoted as ‘morally good’. Thus, any action or purchase that results in waste or promotes unsustainable production carries negative moral connotations.

Climate-based moral decision-making is largely all that young people have known. In some form, choosing not to consider the planet in every choice can provide young people with a prized commodity – freedom from pressure to act with morality.

For young people, living in wilful ignorance of climate change and damaging the planet (and their bodies) in the process is a form of catharsis and escapism. Drinking from plastic water bottles, smoking chemical-filled cigarettes and purchasing clothes mass-produced in sweatshops allows Gen Z to experience a pantomime of the careless, invincible youth that was promised.

Viewed through a binary moral lens, older generations are quick to criticise young people as careless and apathetic. In reality, there’s an unshakable sense of dread amongst young people that a natural disaster will take our lives by the time we reach our parents’ age. In Thomas Grey’s poem ‘Ode on a distant prospect of Eton college’, he states “Where ignorance is bliss, tis folly to be wise”. In essence, if knowing something harmed you, would you be better off not knowing at all? If there’s one thing that Gen Z know, it’s that there is unavoidable harm in their future. If that is the case, and there’s nothing that can be done, may as well have a cigarette.

‘Gen Z and eco-existentialism: A cigarette at the end of the world‘ by Layla Zak-Volpato is one of the Highly Commended essays in our Young Writers’ Competition. Find out more about the competition here.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Ethics in a time of coronavirus

Opinion + Analysis

Climate + Environment, Health + Wellbeing

Donation? More like dump nation

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Politics + Human Rights

‘Eye in the Sky’ and drone warfare

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Health + Wellbeing

Tips on how to find meaningful work

BY Layla Zak-Volpato

Layla is a 22-year-old writer and poet living and working in and around Eora/Sydney. With an educational background in ecology and wildlife conservation, her work focuses heavily on the ethical and moral dilemmas of the anthropocene. Through a creative lens, Layla examines the intersections between gender, identity, philosophy and environmental issues. She aspires to use these themes as the backbone for a career as a scientific communicator who utilises both creative and informative literary forms.

Care is a relationship: Exploring climate distress and what it means for place, self and community

Care is a relationship: Exploring climate distress and what it means for place, self and community

Opinion + AnalysisClimate + EnvironmentRelationships

BY Dr Chloe Watfern Dr Priya Vaughan 30 OCT 2023

As part of their 2023 Ethics Centre residency, researchers Dr Chloe Watfern and Dr Priya Vaughan collaborated with researchers, artists and service providers to explore creative approaches to climate distress, and the ethics of care for place, self, and community in the context of ecological crisis.

Why is it that we are touched most by the things closest to us? Touched, as in, made to feel something strongly, to care in its meanings as both a verb and a noun – to feel concern for and to want to protect or nurture a child, a parent, a special place, a garden, or the bird out the window. It’s a question with an obvious answer. Because they are close. Because they can be felt, sometimes even touched.

Traditional moral theories require us to be unemotional, rational, and logical. For example, we are thought (or urged) to objectively calculate the extent to which our actions will lead to a good outcome for the greatest number of people. However, in the context of our daily lives, an ethics of care highlights the pull of relationships and feelings, like love and compassion, in our moral decision-making.

Tentacle, n.

Zoology: A slender flexible process in animals, esp. invertebrates, serving as an organ of touch or feeling. (Oxford English Dictionary)

The first recorded use of the word “tentacle” in the English language was in 1764, when A. P. Du Pont wrote that “the fingers, or tentacles, end in a deep blue.”

At about this time, the industrial revolution was just beginning in Great Britain, continental Europe, and the United States. Humans in these places gradually, and then very rapidly, moved away from producing things by hand. Coal, iron and water were the core elements of this rapid transformation in societies, extraction and exploitation its drivers. Today, we are at the coal face of its legacy.

Where will all this lead? To a deep blue? To a burning world? To unaddressable environmental collapse? To rubble, ash, and mud?

Care in an era of climate distress

Certainly, we know and feel that the living systems of the earth have been deeply compromised by human activities. This knowledge is a source of intense distress for many of us. At the same time, the collapse of systems creates new and ancient forms of distress, as homes and lives are destroyed or radically altered.

More and more of us care as more and more of us are touched by the effects of our collective actions: biodiversity loss, pollution, global boiling. What might we do with our bare hands, our sentient bodies, to make up for all the loss on our horizon? And where is the horizon anyway?

Professor Timothy Morton refers to global warming, like evolution, or relativity, as a “hyperobject”: something that is very difficult to comprehend using the cognitive tools that we humans have evolved to possess. Climate is everywhere and nowhere, in Antarctic ice sheets and cow belches, in bees and babies, in the cloud and the web, in bushfire smoke and too much (or not enough) rain on a tin roof.

Does Earth’s climate care that it is boiling? We don’t know, because we don’t know how to ask. We can only guess.

Stories of care

During our residency at the Ethics Centre in May 2023, we asked humans to share their stories of care. Colleagues, friends, family members, clinicians, artists, researchers, elders, and knowledge keepers each brought an object that connected to community, self, or planetary care in the climate crisis. These objects – a clay pot, a biodegradable bin bag, leaves collected on country, a handful of seeds – held and evoked memories of grief and loss, but above all, connection with humans, more-than-humans, and places. Close encounters filled with care.

Seeking a way to capture and share these memories, we asked these humans to help us create a tentacular creature: part cephalopod, part bird, part plant, part insect, part fungi, part human, part bacteria, part virus, part landscape.

For us, this tentacular creation was the perfect creature to hold stories of care, responsibility, hope, and fear in the context of our precarious and precious world.

Neither and both human and animal, nature and artifice, Tentacular collapses fictious binaries that have, historically, enabled the climate crisis to be seen as a problem with ‘nature’, rather than the total phenomenon it is.

Each tentacle of this collective artwork reaches outwards, seeking connection and offering stories that speak to the ways we might care, in responsible and responsive ways, for ourselves, each other, and the wounded world. Here, we share some evocative snippets from the stories of care that each person offered:

Gadigal, Bidjigal and Yuin elder Aunty Rhonda Dixon–Grovenor grew up being taught to respect and care for country. She tells people “If we are in nature and enjoy it and care for it, then it nourishes us… Care is a relationship, it’s a two-way, it’s not just one person dominating.”

“Care is a relationship, it’s a two-way, it’s not just one person dominating.” – Aunty Rhonda Dixon-Grovenor

Academic Dr Barbara Doran reflects on the tuition of a beehive: “The bees connected me to a more nuanced relationship with nature… Now, I’m more aware of rain, of flowering patterns, of birds: the ecosystem is amplified in my eyes. But after the fires, I’ve noticed an echo-effect. They have been splitting more than they usually do. This year is the first season with no honey. I’m noticing these resonant patterns in a climate changed world. The hive is my teacher, healer and sharpener of antennas.”

Psychotherapist and Group Facilitator at We Al-li, Georgie Igoe asks us to consider threshold experiences: “For me, care means sitting with discomfort and uncertainty, opening ourselves up to the unknown – in the muck, in the grief, not sidestepping it but acknowledging its power.”

Installation artist and theatre-maker Brownyn Vaughan shares the wisdom of her favourite writers and of her favourite swimming place: “The Mahon pool brought me up, it’s my go-to-place… Professor Astrida Neimanis tells us we must stop trying to ascend and transform. Instead, we must submerge, become part of the water.”

Artist-survivor, and lived experience advocate, Lea Richards, mourns and advocates for the mountains: “Snow melt is mountain’s blood. I weep for the glaciers, so far from arid Australia, yet not separate. I imagine connections to those vanishing snows– a flow of water between us. If I conserve this precious blood, can I tend those far places, postpone the melting?”

Embedded in many, perhaps all, of these stories is a conviction that we need to, as Bronwyn said, submerge, to acknowledge our place in the meshwork of the world, and in so doing, to learn with and from the environment. This means burying ego, rejecting a hierarchy where humans are at the apex, and attending in quotidian ways to what is happening to us and around us. Let’s become like tentacles, feeling our way into a better relationship with the world we care so much about.

Tentacular, as part of the exhibition: Care is a Relationship is on display at UNSW Library until 17 November.

Applications for 2024 Residencies are now open until 30 November. Find out more about The Ethics Centre Residency Program.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

The ANZAC day lie

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Would you kill baby Hitler?

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Ask an ethicist: How should I divvy up my estate in my will?

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics explainer: Normativity

BY Dr Chloe Watfern

Dr Chloe Watfern works across the social sciences, humanities, and creative arts to tackle the big and interconnected challenges of our time, from social inclusion and mental health to climate change. She is currently working at Black Dog Institute (UNSW) and Maridulu Budyari Gumal SPHERE (Sydney Partnership for Health, Education, Research and Enterprise)’s Knowledge Translation Strategic Platform.

BY Dr Priya Vaughan

Dr Priya Vaughan takes an interdisciplinary, and participatory approach to health research, utilising arts-based and socially informed methodologies, knowledge translation (KT) strategies, and interventions to learn about and support mental health and wellbeing. She is currently working at Black Dog Institute (UNSW) and Maridulu Budyari Gumal SPHERE (Sydney Partnership for Health, Education, Research and Enterprise)’s Knowledge Translation Strategic Platform.

ESG is not just about ticking boxes, it’s about earning the public’s trust

ESG is not just about ticking boxes, it’s about earning the public’s trust

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + LeadershipClimate + EnvironmentRelationships

BY Cris Parker The Ethics Alliance 3 MAY 2023

If businesses want to earn the public’s trust, they need to take ESG seriously, and communicate what they’re doing authentically and transparently.

In the eyes of today’s public, businesses must do more than just provide quality products and services, they also have a responsibility to be good corporate citizens and make a positive contribution to society and the environment. This is one reason why so many businesses have made a commitment to Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) standards.

ESG is a framework used to assess a business’s activities and performance on ethical and sustainable issues. This includes an organisation’s ability to safeguard the environment, manage relationships with employees, supply chains and the community, and how company leadership, shareholder rights and internal controls monitor the outcomes. Importantly, the framework serves as a tool to assess how an organisation manages risks and opportunities in our changing world.

The problem is that most members of the public don’t have a good understanding of ESG. According to the SEC Newgate ESG Monitor report, only 12% of Australians had a “good understanding” of ESG. This disconnect between ESG activities and public perception is a problem because it undermines trust in business, especially if ESG activities have been misrepresented.

Members of the Ethics Alliance gathered in April 2023 to discuss the importance of SEC Newgate’s research and consider challenges that organisations face in the way they address ESG and community expectations.

For starters, the ESG Monitor indicated that 38% of Australians feel completely uninformed about companies’ ESG activities. Interestingly, it also suggested 72% of people either “never” or “rarely” look at the ESG reporting, while only a mere 8% of people trust ESG reporting.

Some of this scepticism around ESG may have been cultivated due to it politicisation. In April 2023 the leader of the opposition, Peter Dutton, commented: “To be frank, some business leaders need to stop craving popularity on social media by signing up to every social cause, even though they may not believe in it.” This attitude acts in contrast to the global research from the 2023 Edelman Trust Barometer that shows 82% of people expect CEOs to take a public stand on climate change. And to Dutton’s point, they certainly expect authenticity.

The public holds high expectations for businesses to use their influence for good. SEC Newgate’s study showed that of those surveyed, 80% agree that companies have a responsibility to behave like good citizens and consider their impact on other people and the planet. It also showed that 66% of people are also willing to give a company a second chance if it was transparent about its mistake and stated how it would do better in the future.

If businesses want to live up to community expectations and strengthen their social value, then they need to carefully choose which ESG initiatives to focus on and ensure they have legitimacy in those areas. When evaluating, they should ask the following: Is it genuine? Is it meaningful? Is the organisation committed? And how do I know for sure or where is the proof?

By demonstrating a clear link between sustainability efforts and overall strategy, businesses can better align their initiatives with community expectations.

One starting point is a materiality assessment, which is a process to identify and prioritise the most relevant and significant ESG factors that have a substantial impact on the business’s operations, financial performance and stakeholder interests. This exploration can help identify the most pressing issues that align with the purpose and resonate with the community.

Other principles for organisations to consider when developing their ESG framework that emerged from The Alliance’s discussions were:

- Ethical conduct – including treating employees fairly, avoiding unethical practices, and minimising environmental harm.

- Giving back – which may involve investing in local communities, adopting environmentally friendly practices, or supporting social initiatives.

- Transparency and accountability –stakeholders, including consumers, employees, and shareholders, often have differing perspectives on ESG issues, making it challenging for businesses to balance these conflicting demands and trade-offs.

Communication also needs to be well considered by organisations in order to address the disconnect between the community’s need for transparent ESG information and their desire to learn about it. Connecting with stakeholders transparently about an organisation’s progress and mistakes can help meet these challenges.

ESG is about more than just accounting. It’s demonstrating a business’s responsibility and recognising the importance of sustainable practices in safeguarding our planet. ESG needs to be a whole company effort that is undertaken authentically and communicated transparently to the public that reflects its purpose, values and principles. The more businesses that do this, the more the public will understand what ESG is and the more they will come to trust businesses as being responsible corporate citizens.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

How to give your new year’s resolutions more meaning

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Has passivity contributed to the rise of corrupt lawyers?

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Want #MeToo to serve justice? Use it responsibly.

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Science + Technology

If humans bully robots there will be dire consequences

BY Cris Parker

Cris Parker is Head of The Ethics Alliance and a Director of the Banking and Finance Oath.

BY The Ethics Alliance

The Ethics Alliance is a community of organisations sharing insights and learning together, to find a better way of doing business. The Alliance is an initiative of The Ethics Centre.

Big Thinker: Ralph Waldo Emerson

Big Thinker: Ralph Waldo Emerson

Big thinkerClimate + EnvironmentRelationships

BY The Ethics Centre 28 APR 2023

Committed to individualism and credited as the father of transcendentalism, Ralph Waldo Emerson (1803-1882) was an American essayist, lecturer, philosopher and poet.

Initially on a path to follow his father’s footsteps and serve in the Christian ministry, Emerson attended Harvard’s Divinity School to become a pastor. But as time went on and he delved deeper into his religious studies, he realised an unignorable sense of detachment and divergence from the traditional religious values he was immersed in. And so he left the Second Unitarian Church and decided to forge his own path.

“To be yourself in a world that is constantly trying to make you something else is the greatest accomplishment.”

Emerson’s influential career began with public lectures in Boston that would inspire some of his most renowned essays and ideas. His lectures centred on human culture, English literature, biography and philosophy. He was known for popularising the major movement known as transcendentalism.

The Father of Transcendentalism

“Transcendental” was initially coined by philosopher Immanuel Kant in his theory of transcendental idealism. It’s a theory of perception that holds space and time, along with our five senses, are all subjective experiences and don’t exist outside of the human experience.

Even though Kant coined the term, Emerson is regarded as the father of transcendentalism.

Emerson’s transcendentalism, which became one of America’s first literature and philosophical movements, holds that we ought to be doubtful of knowledge we get from our five senses or even logic and reason; the only trustworthy source of knowledge manifests itself in our personal intuition and self-revelations.

In one of his first lectures, “The Uses of Natural History”, Emerson planted the initial seed for the movement when he explained science as something innately human. He emphasised nature to be an extension of one’s self: “the whole of Nature is a metaphor or image of the human mind.”

His book-length 1836 essay “Nature” is what officially and explicitly defined transcendentalism.

In essence, transcendentalists believe nature is paramount: all their ideals are rooted in the natural world. They believe all things are inherently good, humans and nature alike. In much the same way, transcendentalists see the divinity – the “God” – in everything and everyone. As Emerson wrote, “I am part or particle of God.” Transcendentalists also believe in the human potential for achieving greatness and genius.

Emerson is responsible for introducing a number of people to metaphysical concepts for the first time. A group he helped found in the late 1830’s called the Transcendental Club had dangerous conversations that critiqued societal institutions of the time, such as organised religion and slavery. Its members included prominent thinkers of the time, like Henry David Thoreau and Margaret Fuller, and allowed a space for transcendentalist ideas to grow.

Self-Reliance

As the title of one of his most famous essays, “Self-Reliance” describes one of his principal philosophies: relying solely on ourselves. Emerson’s transcendentalism has been equated to romantic individualism because of his emphasis on the self. For understanding and greatness, Emerson believed we ought only to rely on ourselves and trust our intuition. In fact, he believed the only thing separating the common person from “greatness” is that the “greats” have the gall to admit precisely what they’re feeling when they feel it. As humans, much of our experiences and emotions are shared, and Emerson saw beauty in such commonalities.

At the same time, he cited conformity as a major barrier to achieving greatness. He thought we should be comfortable and proud of being distinctly ourselves. He praised individuality and the pursuit of achieving “an original relation to the universe” by tuning inwards.

The key to unlocking genius is listening to what Emerson called our “creative insight”. He felt such insight was decidedly divine, God’s way of individually speaking to us. This insight is necessary for anyone to accomplish anything meaningful, and so Emerson encouraged everyone to trust their own creative insight over societal ones. Listening to our divinity, our creative insight, yields a life lived authentically.

“It is easy in the world to live after the world’s opinion; it is easy in solitude to live after our own; but the great man is he who in the midst of the crowd keeps with perfect sweetness the independence of solitude.”

It’s these transcendentalist ideologies that would eventually inspire philosopher Henry David Thoreau to reject society and go into the woods in order “to live deliberately and front only the essential facts of life”. And that same line of thinking is what inspired Christopher McCandless, an infamous American adventurer, to abandon family and escape to Fairbanks, Alaska in the 1990s. His story of living in the solitude of wilderness was later popularised in the film and novel Into the Wild.

Although some find wisdom and beauty in Emerson’s fierce admiration of solitude and complete rejection of groupthink, others see privilege in his ideals. Not everyone is able to exercise free will; not everyone can afford to stray from the norm and escape their social circumstances. And so to some, his ideas are lofty and unattainable, less you have the power of class and money on your side.

Beyond privilege, others see selfishness in his philosophies. By tuning inwards and considering only our own needs and desires, what is lost? What might we sacrifice when we neglect those around us? When we disregard even our loved ones? And yet, Emerson never said anything definitively:

“But it is the fault of our own rhetoric that we cannot strongly state one fact without seeming to belie some other. I hold our actual knowledge is very cheap.”

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Big thinker

Relationships

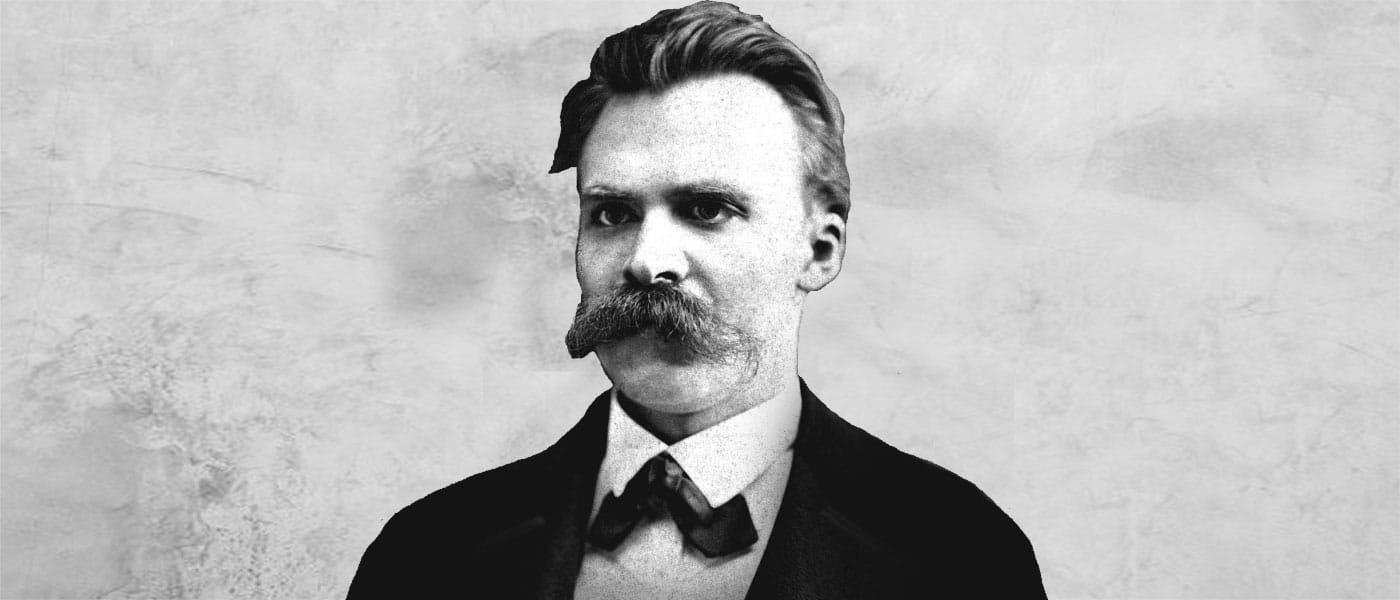

Big Thinker: Friedrich Nietzsche

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Why listening to people we disagree with can expand our worldview

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Existentialism

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships

Treating citizens as customers is a recipe for distrust

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Donation? More like dump nation

Donation? More like dump nation

Opinion + AnalysisClimate + EnvironmentHealth + Wellbeing

BY Amal Awad 27 FEB 2023

In the desire to clean up our living and mental spaces, we need not create a costly mess for charitable organisations receiving our donations.

Several years ago when I was producing for radio, I found myself knee-deep in the topic of minimalism. I was fascinated by the concept: living with a minimal number of possessions, replacing rather than accumulating, being ‘timeless’ rather than at the mercy of trends. At the forefront of the movement were Joshua Fields Millburn and Ryan Nicodemus, aka The Minimalists, whom The New Yorker called ‘Sincere prophets of anti-consumerism’. They rose to fame with documentaries, a podcast and a best-selling book, all of which promoted this ‘minimalist lifestyle’.

A minimalist approach does not preclude you from purchasing the latest smartphone, it resists desiring that smartphone, which, like most on-trend technology, will either get superseded by a newer version within a year, or break the moment its two-year warranty has expired. (Remember your childhood TV that worked for 17 years?)

I interviewed Nicodemus and easily understood how his austere approach to housekeeping might have its appeal. What would it be like to not be weighed down by your possessions? To actually derive full use out of what you already owned? To simply not want the newest shiny thing?

At the heart of this approach is a mental philosophy that fuels a mindset, not just a way of life. Being a minimalist will mean you’re not part of the problem in what seems to be an ever-expanding consumerist wasteland. You’re better for the environment because you don’t accumulate. You’re not someone who, in the process of divesting yourself of unneeded possessions, overloads your local op shop because you have five different versions of a favourite item.

While the ability to not accumulate possessions may be harder to achieve for most people, as each new year rolls in with the proclamation of a ‘New Year, New Me’, we tend to become minimalists.

In a fever, we rule out bad habits and embrace healthy ones. Invariably, this involves some level of decluttering because we acknowledge that we are wasting money on things we don’t need.

And this is why it’s not uncommon to drive past a Vinnie’s in January and see half-opened bags of donations strewn across the pavement.

That ardent desire to strip away the baggage in our lives ends up becoming someone else’s problem when we dump donations, rather than engaging with charitable organisations and op-shops directly.

Unfortunately, this is a cumbersome, costly problem for the charitable organisations receiving these donations. Rather than an orderly, well-packed offering of useable items, charities are reporting the prevalence of irresponsible offloading of unusable items. As Tory Shepherd reported for The Guardian, “Australian charities are forking out millions of dollars to deal with donation ‘dumping’ at the same time that they are seeing rising demand for their services ‘as the cost-of-living crisis bites’”.

Not for the first time, we are seeing op shops plead with their local communities to not dump and run, leaving behind what is often rubbish, or items that the shop cannot accommodate, such as furniture. Following Covid lockdowns, we saw a similar phenomenon as people took stock of their lives and possessions—and left it to charities to take care of their unwanted items. The NSW Environment Protection Authority (EPA) and Charitable Recycling Australia are pushing this message of responsible donating.

As a deeply consumerist society, we’re at the mercy of goods that are not built to last.

There is a need for donations; organisations like Vinnies are clearly welcoming of reusable, recyclable goods that can be repurposed. However, instead of owning the act of throwing something away, we might pass on the responsibility by giving it away and making it a charitable act. There are deeply-felt financial and practical impacts on these organisations when they have to clean up the mess of people who don’t take the time to sort through their possessions, or who are careless in how they deliver their donations. The resounding advice is that if it’s something you’d give to a friend, it’s suitable for a donation.

Not everyone can afford goods made of recyclable or sustainable material. But we can try to create a new way forward. We can reconsider our approach to ownership and divestment; buy what we need and try to purchase higher quality, sustainable goods whenever possible. We can also appeal to businesses to enact more sustainable practices. We can lobby local councils and government.

In the meantime, while it’s a positive that we don’t want to just throw things out, it does not take much to do a stocktake before offering up donations: is what am I giving away something I would give to someone I care about? Is it in working order? For large items, check with your op shop or organisation before delivering them. Don’t leave items in front of a closed shopfront. Don’t treat charities like a garbage dump.

There is tidying a la Marie Kondo but then there is medically-reviewed physical decluttering that research suggests is good for our mental health. Even digital decluttering can have a positive impact on our productivity. But it’s worth considering, when we divest ourselves of unwanted goods, whether we are making sustainable donations or trashing items simply to upgrade.

If we can accept that decluttering is good for us, does that not also suggest that having cleaner spaces with fewer possessions is a better way to live? Perhaps a more worthy and sustainable goal is to take some cues from the minimalist mindset. I’m all for annual purges but even better would be to not need to declutter in the first place.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

It’s easy to ignore the people we can’t see

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Health + Wellbeing

What your email signature says about you

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Exercising your moral muscle

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Politics + Human Rights

Don’t throw the birth plan out with the birth water!

Who is to blame? Moral responsibility and the case for reparations

Who is to blame? Moral responsibility and the case for reparations

Opinion + AnalysisClimate + EnvironmentPolitics + Human Rights

BY Anna Goodman 17 JAN 2023

Reparations recently made the news after the COP27, with poorer countries demanding richer countries pay for damages caused by global warming. But, are reparations the best way to achieve justice for previous harms, and what do they tell us about moral responsibility?

Throughout the 19th and 20th centuries, western countries developed and industrialised without many (or any) regulations. Coal burning factories produced new technologies, new agricultural practices led to chemical runoff and land clearing, and global trade and travel have accelerated the production of man-made greenhouse gases. Historically, developed countries have contributed to just under 80% of total carbon emissions.

As a result, devastating floods, bush fires, droughts and storms have ruinous impacts on communities and countries. Rising sea levels threaten small island nations and coastal towns alike. The countries and populations feeling the biggest impacts tend to be poorer and have fewer resources to deal with the fallout of climate related catastrophes.

Climate change is a global issue, and it’s clearly impacting poorer, less developed countries in more drastic ways than wealthier ones. Can reparations really be a solution to such a complex issue?

What are reparations?

Reparations are usually monetary (or something else that transfers wealth, like land) compensation, paid by a dominant group to an individual or a group that has been wronged or harmed. Reparations are usually viewed as one mechanism for remedying a past injustice. Given past injustices have created present-day inequalities and much of this inequality is socioeconomic, reparations are one way to make amends and “even the playing field.

The controversy surrounding reparations

Reparations become controversial when we overlay our common conceptions of moral responsibility. We typically view someone as morally responsible for something if they caused that thing to happen. For example, if you steal something from a store and are fully aware and in control of yourself, most people would view you as morally responsible for that action, and therefore deserving of the repercussions that come from stealing.

But, who is morally responsible for the global climate crisis? European countries have some of the most progressive climate change policies in the world today, but were responsible for the majority of emissions during the 19th and 20th centuries. On the other hand, China and India haven’t historically been big emitters, but today they are. It’s unclear who is more responsible for the state of the climate today. So, if we can’t find someone or some group directly morally responsible, should reparations be paid at all?

The case for reparations

There are two main reasons why I think our common notion of moral responsibility translates into a good enough argument in favour of reparations.

Firstly, we need to think about what inequality looks like in the world. Much of the inequality that we can observe is economic, and it is often the direct result of past injustices.

If we truly want to live in a just world, we are going to need to level the playing field, and money is one of the most effective ways to do that.

The question is: where should this money come from? Whether or not someone from a dominant group actively participated in or committed one of these wrongs, they likely experienced either direct or indirect benefits.

For example, industrialised countries have benefited from the use of fossil fuels, and generated their wealth through manufacturing and trade, which compounded over decades and centuries. To the extent that individuals and groups today have benefited from past injustices, then they owe some reparations to the groups that are disadvantaged because of those past injustices. Wealthy countries, therefore, that have compounded wealth that came from industrialising during a time where carbon emissions remained unchecked should pay reparations, even though none of the people alive today actively contributed to the climate emissions of the past.

Second, reparations acknowledge that the payer has some responsibility for the wrongs committed towards the payee. As former prime minister Scott Morrison said about $280 million of reparations that Aboriginal communities received in 2017, “This is a long-called-for step… to say formally not just that we’re deeply sorry for what happened, but that we will take responsibility for it”. Paying reparations acknowledges that harm occurred to a group of people because it recognises that there is lasting inequality that has occurred from that harm. In addition, the person or group paying the reparations recognises that they have benefitted from the harm or inequality, even if they didn’t directly cause it.

While reparations don’t promise to remove all inequality or solve every injustice, they are an important step for dominant groups to acknowledge and accept responsibility for harms of the past, as well as taking an important step to close present socioeconomic gaps.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Big thinker

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Big Thinker: Mary Wollstonecraft

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

Lessons from Los Angeles: Ethics in a declining democracy

Opinion + Analysis

Climate + Environment, Politics + Human Rights

Increase or reduce immigration? Recommended reads

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships