Big Thinker: Marcus Aurelius

If you became a Roman Emperor, would you have maintained your humility? That’s one of the things Marcus Aurelius (121-180 CE), the “Stoic philosopher king”, was known for.

Adopted by his uncle, the Emperor of Rome, when he was a young man, Marcus spent his adult life learning the business of government, including serving as consul (chief magistrate) for three separate years.

Prior to becoming Emperor, Marcus also began forming an interest in philosophy. In particular, the writings of the former slave Epictetus (55 BCE–135 CE), a renowned thinker of Stoic moral philosophy. This would turn out to be the influence of one of Marcus’ greatest legacies, the Meditations.

Meditations and Stoicism

The Meditations of Marcus Aurelius is a series of twelve books containing personal notes and ideas for self-guidance and self-improvement. Scholars believe it’s unlikely that it was ever written to be seen, but rather that the books are akin to a journal, written in private for his own moral improvement, to reinforce in himself the Stoic doctrines that he aimed to live and rule by.

Marcus wrote these meditations during the second decade of his reign and last decade of his life, during which he was campaigning to take back and expand parts of his empire after enduring years of plague and invasion.

He saw the philosophy of Stoicism as the principal guidance for his life and writing, though quotes from many other philosophies can be found in his books.

Stoicism is an ancient philosophy whose ethics propose a focus on reason and happiness (flourishing). It says, like many philosophies at the time, that the rational person’s ultimate goal is to live happily.

Unique to Stoicism, though, is the idea that the only thing needed for happiness is virtue. To live perfectly virtuously is to be happy, regardless of external constraints or effects. This leads to a difficult conclusion, but one that the Stoics maintain: a virtuous person being tortured for example, is still maximally happy, since they still possess the one beneficial quality, virtue.

It follows from this, say the Stoics, that happiness is fully within our personal control. Marcus’ writing to himself reinforces this idea in various ways, supporting himself through the difficulties of Roman life, not to mention a ruler during conflict.

“Such as are your habitual thoughts, such also will be the character of your mind; for the soul is dyed by the thoughts.”

One of the main teachings of Stoicism is acceptance. This is where the common misunderstanding of Stoicism being restraint comes from. Many believe that it encourages the bottling or rejecting of emotion. Rather, it says that virtuous people are not overcome by impulsive and excessive emotion.

This is not because Stoics believed that we must restrain ourselves. Instead, they believed that we find virtue through knowledge. Then, once we properly obtain the knowledge that coincides with our rationality and nature, we will freely accept the reality of things that once may have caused us grief (or joy).

“If you are distressed by anything external, the pain is not due to the thing itself, but to your estimate of it; and this you have the power to revoke at any moment.”

Marcus used these teachings to guide himself, as is evident in the many quotes that continue to circulate in pop culture. Some of these speak of the importance of endurance in the pursuit of virtue, believing that challenges are an opportunity to strengthen character. Others speak of the importance of gratitude in responding to the perceived highs and lows of life.

“Do not indulge in dreams of having what you have not, but reckon up the chief of the blessings you do possess, and then thankfully remember how you would crave for them if they were not yours.”

Marcus Aurelius left a legacy that has lingered across cultures and centuries to continue guiding people on their journeys of self-improvement.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Big thinker

Society + Culture

Big Thinker: Epicurus

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Health + Wellbeing, Society + Culture

Corruption in sport: From the playing field to the field of ethics

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Business + Leadership, Society + Culture

Our dollar is our voice: The ethics of boycotting

Opinion + Analysis, READ

Society + Culture, Relationships

Losing the thread: How social media shapes us

Our dollar is our voice: The ethics of boycotting

Our dollar is our voice: The ethics of boycotting

Opinion + AnalysisPolitics + Human RightsBusiness + LeadershipSociety + Culture

BY Tim Dean 17 FEB 2026

Boycotts can be an effective mechanism for making change. But they can also be weaponised or harmful. Here are some tips to ensure your spending aligns with your values.

There I was, strolling through campus as an undergraduate in the 1990s, casually enjoying a KitKat, when I was accosted by a friend who sternly rebuked me for my choice of snack. Didn’t I know that we were boycotting Nestlé? Didn’t I know about all the terrible things Nestlé was doing by aggressively promoting its baby formula in the developing world, thus discouraging natural breastfeeding?

Well, I did now. And so I took a break from KitKats for many years. Until I discovered the boycott had started and been lifted years before my run-in with my activist friend. As it turned out, a decade prior to my campus encounter, Nestlé had already responded to the boycotters’ concerns and had subsequently signed on to a World Health Organization code that limited the way infant formula could be marketed. So, while my friend was a little behind on the news, it seemed the boycott had worked after all.

Boycotts are no less popular today. In late 2025, dozens of artists pulled their work from Spotify and thousands of listeners cancelled their accounts after discovering that the company’s CEO, Daniel Ek, invested over 100 million Euros into a German military technology company that is developing artificial intelligence systems. In 2023, Bud Light lost its spot as the top-selling beer in the United States after drinkers boycotted it following a social media promotion involving transgender personality, Dylan Mulvaney. The Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions (BDS) movement has been promoting boycotts of Israeli products and companies that support Israel for over a decade, gaining greater momentum since the 2023 war in Gaza. And there are many more.

As individuals, we may not have the power to rectify many of the great ills we perceive in the world today, but as agents in a capitalist market, we do have power to choose which products and services to buy.

In this regard, our dollar is our voice, and we can choose to use that voice to protest against things we find morally problematic. Some people – like my KitKat-critical friend – also stress that we must take responsibility for where our money flows, and we have an obligation to not support companies that are doing harm in the world.

However, thinking about whom we support with our purchases puts a significant ethical burden on our shoulders. How should we decide which companies to support and which to avoid? Do we have a responsibility to research every product and every company before handing over our money? How can we be confident that our boycott won’t do more harm than good?

Buyer beware

Boycotts don’t just impose a cost on us – primarily by depriving us of something we would otherwise purchase – they impose a cost on the producer, so it’s important to be confident that this cost is justified.

If buying the product would directly support practices that you oppose, such as damaging the environment or employing workers in sweatshops, then a boycott can contribute to preventing those harms. We can also choose to boycott for other reasons, including showing our opposition to a company’s support for a social issue, raising awareness of injustices or protesting the actions of individuals within an organisation. However, if we’re boycotting something that was produced by thousands of people, such as a film, because of the actions of just one person involved, then we might be unfairly imposing a cost on everyone involved, including those who were not involved in the wrongdoing.

Boycotts can also be used threaten, intimidate or exclude people, such as those directed against minorities, ethnic or religious groups, or against vulnerable peoples. We need to be confident that our boycott will target those responsible for the harms while not impinging on the basic rights or liberties of people who are not involved.

There are also risks in joining a boycott movement, especially if we feel pressured into doing so or if activists have manipulated the narrative to promote their perspective over alternatives. Take the Spotify boycott, for example. It is true that Spotify’s CEO invested in a military technology company. However, many people claimed that company was supplying weapons to Israel, and that was a key justification for them pulling their support for Spotify. However, Helsing had no contracts with Israel and was, instead, focusing its work on the defence of Ukraine and Europe – a cause that many boycotters might even support.

Know your enemy

The risk of acting on misinformation or biased perspectives places greater pressure on us to do our own research, and it’s here that we need to consider how much homework we’re actually willing or able to do.

In the course of writing this article, I delved back into the history of the Nestlé boycott only to find that another group has been encouraging people to avoid Nestle products because it doesn’t believe that the company is conforming to its own revised marketing policies. Even then, uncovering the details and the evidence is not a trivial undertaking. As such, I’m still not entirely sure where I stand on KitKats.

While we all have an ethical responsibility to act on our values and principles, and make sure that we’re reasonably well informed about the companies and products that we interact with, it’s unreasonable to expect us to do exhaustive research on everything that we buy. That said, if there is reliable information that a company is doing harm, then we have a responsibility to not ignore it and should adjust our purchasing decisions accordingly.

Boycotts also shouldn’t last for ever; an ethical boycott should aim to make itself redundant. Before blacklisting a company, consider what reasonable measures it could take for you to lift your boycott. That might be ceasing harmful practices, compensating those who were impacted, and/or apologising for harms done. If you set the bar too high, there’s a risk that you’re engaging in the boycott to satisfy your sense of outrage rather than seeking to make the world a better place. And if the company clears the bar, then you should have good reason to drop the boycott.

Finally, even though a coordinated boycott can be highly effective, be wary of judging others too harshly for their choice to not participate. Different people value different things, and have different budgets regarding how much cost they are willing to bear when considering what they purchase. Informing others about the harms you believe a company is causing is one thing, but browbeating them for not joining a boycott risks tipping over into moralising.

Boycotts can be a powerful tool for change. But they can also be weaponised or implemented hastily or with malicious intent, so we want to ensure we’re making conscious and ethical decisions for the right reasons. We often lament the lack of power that we have individually to make the world a better place. But if there’s one thing that money is good at, it’s sending a message.

BY Tim Dean

Dr Tim Dean is a public philosopher, speaker and writer. He is Philosopher in Residence and Manos Chair in Ethics at The Ethics Centre.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

The role of ethics in commercial and professional relationships

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Sir Geoff Mulgan on what makes a good leader

Reports

Business + Leadership

A Guide to Purpose, Values, Principles

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Moral injury is a new test for employers

On policing protest

On policing protest

Opinion + AnalysisPolitics + Human RightsSociety + Culture

BY Simon Longstaff 16 FEB 2026

I was not there when police confronted people at Sydney Town Hall, protesting against the visit of Israeli President Herzog. So, the best I can do is offer a way of assessing what took place – once all of the evidence is before us.

A fundamental principle of policing is that it is most effective when practised with the consent of the community. With that consent in hand, police are accorded extraordinary powers that may not be exercised by ordinary citizens. Those powers include the right to use force in the discharge of their duties. However, these are not ‘unbridled’ powers. Rather, the use of force is hemmed in by a series of legal and ethical boundaries that must not be crossed.

The application of such boundaries is especially important when police are authorised to use lethal force. However, whether armed or not, the ethos of policing is supposed to be conditioned by two fundamental considerations.

First, all police in Australia exercise what is known as the ‘original authority of the constable’. This is a special kind of authority intended to ensure that police uphold the peace in an even-handed manner, without regard to a person’s wealth, status or office. Originally conceived in medieval times, it ensures that all are equal before the law. One aspect of this ‘original authority’ is the right (or, perhaps, the duty) to exercise discretion when employing the special powers conferred on police. It is for this reason that there is a general expectation that police should warn rather than punish people when that would be sufficient to achieve the proper ends of law enforcement.

And what are those ends? To the surprise of many (including some police) the role of policing is not to apprehend criminals so that they may be brought before the courts. Nor is it simply to ‘enforce the law’. Both of those elements of policing are important. However, they are in service of a more general purpose which is to uphold the legal and moral rights of citizens (only some of which are codified in law). This is why society frowns on the actions of those rare police who, say, plant evidence on a suspect in hope of proving their presumed guilt. You cannot uphold the legal and moral rights of citizens by violating the legal and moral rights of citizens! It is only when police act in a manner consistent with their overarching purpose that the community extends the trust required for policing to be maximally effective.

The main point to note here is that the best way to prevent crimes and other harms is for communities to be intolerant of those who engage in harmful (and especially criminal) conduct. In turn, the communities that most trust their police are also those most intolerant of crime and other antisocial behaviour. For the avoidance of doubt, let me make it clear that I do not consider peaceful protesting to be ‘antisocial behaviour’. Rather, it plays a vital role in a vibrant democratic society.

The second basic fact that conditions policing is related to the asymmetry of power between police and citizens. The most obvious sign of that asymmetry is that, with only a few exceptions, only police may be armed in the course of daily civic life. However, with great power comes great responsibility. In this case, the use of force, by police, must be proportionate and discriminate. That is, force may only be applied to the minimal degree necessary to secure the peace.

Policing is dangerous work. But beyond the risk of physical harm, police are often taunted and insulted – especially by seasoned provocateurs who are trying to bait police to lose control. That is why police require training to resist the all-too-human tendency towards self-protection or retaliation. Again, this is essential to maintaining community trust and consent.

The public needs to be convinced that police have the training and discipline to apply minimal force – no matter what the provocation.

Given all of the above, what questions might we ask about the way police engaged with protesters gathered at the Sydney Town Hall? Did police exercise discretion in favour of the citizens to whom they are ultimately accountable? Was their use of force discriminate and proportional? Did the police exercise maximum restraint – no matter what the provocation?

As to where we might go from here, I think that we would all be well served if the politicians who set the laws within which police operate and the leadership of NSW police all stopped for a moment to ask, “Will the thing we next do build or undermine the trust and consent of the community as a whole?”.

BY Simon Longstaff

Simon Longstaff began his working life on Groote Eylandt in the Northern Territory of Australia. He is proud of his kinship ties to the Anindilyakwa people. After a period studying law in Sydney and teaching in Tasmania, he pursued postgraduate studies as a Member of Magdalene College, Cambridge. In 1991, Simon commenced his work as the first Executive Director of The Ethics Centre. In 2013, he was made an officer of the Order of Australia (AO) for “distinguished service to the community through the promotion of ethical standards in governance and business, to improving corporate responsibility, and to philosophy.” Simon is an Adjunct Professor of the Australian Graduate School of Management at UNSW, a Fellow of CPA Australia, the Royal Society of NSW and the Australian Risk Policy Institute.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Society + Culture

When our possibilities seem to collapse

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

Lessons from Los Angeles: Ethics in a declining democracy

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

A good voter’s guide to bad faith tactics

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships, Society + Culture

Film Review: If Beale Street Could Talk

What it means to love your country

What it means to love your country

Opinion + AnalysisSociety + CulturePolitics + Human Rights

BY Marlene Jo Baquiran 4 FEB 2026

The idea of patriotism has become increasingly contentious in Australia, particularly on January 26, with much wariness and controversy over what to call the day itself.

January 26 is a reopening of the deep wound of colonisation for many Indigenous Australians. It can also be, to a lesser extent, a confusing day to be an Australian patriot who is simultaneously ashamed of their country’s colonial past.

Australia’s colonial roots have always loomed large in its young history, but it is helpful to know that the experience of being conflicted about one’s allegiance to country is not new.

In 1943, the Jewish-heritage French philosopher Simone Weil wrote her last text dissecting the difficulty of patriotism while in WWII France. France had built its modern identity on Enlightenment ideals of liberty, equality and universal human rights. Yet at Weil’s time of writing, it was actively building a colonial empire and collaborating with the German fascist state which violated these principles.

In a similar vein, modern Australia prides itself on a narrative of multiculturalism, wealth and safety, whilst also being built on the injustices of colonialism. It is increasingly suffering from fraying social cohesion as a result of this inconsistency. The controversy around January 26 is one clear recurring symptom of this.

Weil would have classified herself as a French patriot, but she was also one of its harshest critics. In her philosophy, love of country and criticism of its past are not mutually exclusive; in fact, love of country can only be authentic if it also includes honest criticism.

Patriotism in its best form is the compassionate love of one’s country and the people, communities, history and memories that comprise it.

But to Weil, this patriotism becomes maligned when it is not based in compassion, and instead entails blind allegiance to an abstract nation or symbol – something she called ‘servile love’, which she names as the ugly shadow of patriotism: nationalism.

In her vocabulary, nationalism is more extreme than loving your country; it is about engaging in idolatry and worshipping a false image of one’s country that is based on wishful thinking, rather than truth.

The wishful thinking of nationalism means making oneself ignorant through selective memory: erasing the difficulties of the past in a hurry to create a new, sanitised future. It uses boastful pride to cover up past shames.

In the same way that it is difficult to respect the integrity of an individual who is insecure about admitting their wrongs and will only assert the ways in which they are right, a nation that also cannot integrate its failings will find it hard to sustain respect.

It’s important to note that this is a collective responsibility: generational injustice requires generational reparation, and it is not possible for sole individuals to bear the whole burden of either harm or reparation for entire generations.

What makes a patriot?

In Weil’s framework, the distinction between patriotism (healthy) and nationalism (unhealthy) is ‘rootedness’, which Weil identifies as one of the deepest but most difficult to identify human needs.

A ‘rooted’ individual, community, or nation is one that is mature and connected to its history deeply enough that it has the resilience to withstand criticisms and accommodate the nurturance of many types of people.

Weil writes: “A human being is rooted through their real, active and natural participation in the life of a collectivity that keeps alive treasures of the past and has aspirations of the future.”

To Australia’s credit, there are many ways in which collective participation is healthy and available to many, which allows people from many walks of life to be rooted here.

Some often-cited reasons: being able to enjoy relative peace and comforts; fond memories of swimming at the beach or hiking nature trails (“Australia is the only country proud of its weather” – the allegations are true!); its cultural diversity. There are many patriots to whom the flag does not represent racism and exclusion, because in it they see genuine, cultivated attachments to their country. They are not focused on asserting the superiority of an identity, but on honouring a meaningful relationship with one’s community and environment – strong roots.

Yet social cohesion feels more fragile lately, partly because of the belief that the ‘rootedness’ of other communities comes at the expense of theirs. Acknowledging that bigotry and a history of colonialism still gnaw at Australia’s national identity feels like a concession or weakness to other communities – but strength can only be built from integrity rather than denial.

It is not talking about a nation’s injustices that threatens its identity, but rather, lies. Weil writes: “This entails a terrible responsibility. Because what we are talking about is recreating the country’s soul, and there is such a strong temptation to do this by dint of lies and partial truths, that it requires more heroism to insist on the truth.”

To those who have been uprooted – whether they are displaced from actual homes, felt excluded or otherised by their fellow neighbours, or felt seething hatred and even violence towards their community – it is difficult to engage with collective life when it lacks common ground built from truth.

If we accept Weil’s claim that rootedness is a fundamental human need, love and criticism of one’s country could be understood as separate species that grow from the same fertile ground: a desire to belong to and steward the country they share.

When it comes to January 26, a call to recognise it as ‘Invasion Day’ is a legitimate criticism because it is truthful to historical events. Australian patriots should not feel threatened if their love of country is deep and sincere; they should take courage that there is a way to mature the national identity in a way that is based in truth, which can allow for the roots of many to grow in its soil.

To Weil, diverse co-existence enriches a community such that “external influences [are not] an addition, but … a stimulus that makes its own life more intense.”

For any patriot, prejudice and lies are the enemy, not their own community.

BY Marlene Jo Baquiran

Marlene Jo Baquiran is a writer and activist from Western Sydney (Dharug land), Australia. Her writing focuses on culture, politics and climate, and is also featured in the book 'On This Ground: Best Australian Nature Writing'. She has worked on various climate technologies and currently runs the grassroots group 'Climate Writers' (Instagram: @climatewriters), which won the Edna Ryan Award for Community Activism.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Climate + Environment, Politics + Human Rights, Relationships, Society + Culture

The youth are rising. Will we listen?

Explainer, READ

Society + Culture

Ethics Explainer: WEIRD ethics

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Society + Culture

A win for The Ethics Centre

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Society + Culture

Does ethical porn exist?

Should your AI notetaker be in the room?

Should your AI notetaker be in the room?

Opinion + AnalysisScience + Technology

BY Aubrey Blanche 3 FEB 2026

It seems like everyone is using an AI notetaker these days. They’re a way for users to stay more present in meetings, keep better track of commitments and action items, and perform much better than most people’s memories. On the surface, they look like a simple example of AI living up the hype of improved efficiency and performance.

As an AI ethicist, I’ve watched more people I have meetings use AI notetakers, and it’s increasingly filled me with unease: it’s invited to more and more meetings (including when the user doesn’t actually attend) and I rarely encounter someone who has explicitly asked for my consent to use the tool to take notes.

However, as a busy executive with days full of context switching across a dizzying array of topics, I felt a lot of FOMO at the potential advantages of taking a load off so I could focus on higher-value tasks. It’s clear why people see utility in these tools, especially in an age where many of us are cognitively overloaded and spread too thin. But in our rush to offload some work, we don’t always stop to consider the best way to do it.

When a “low risk” use case isn’t

It might be easy to think that using AI for something as simple as taking notes isn’t ethically challenging. And if the argument is that it should be ethically low stakes, you’re probably right. But the reality is much different.

Taking notes with technology tangles the complex topics of consent, agency, and privacy. Because taking notes with AI requires recording, transcribing, and interpreting someone’s ideas, these issues come to the fore. To use these technologies ethically, everyone in each meeting should:

- Know that that they are being recorded

- Understand how their data will be used, stored, and/or transferred

- Have full confidence that opting out is acceptable.

The reality is that this shouldn’t be hard – but the economics of selling AI notetaking tools means that achieving these objectives isn’t as straightforward as download, open, record. This doesn’t mean that these tools can’t be used ethically, but it does mean that in order to do so we have to use them with intention.

What questions to ask:

What models are being used?

Not all AI is built the same, in terms of both technical performance and the safety practices that surround them. Most tools on the market use foundation models from frontier AI labs like Anthropic and OpenAI (which make Claude and ChatGPT, respectively), but some companies train and deploy their own custom models. These companies vary widely in the rigour of their safety practices. You can get a deeper understanding of how a given company or model approaches safety by seeking out the model cards for a given tool.

The particular risk you’re taking will depend on a combination of your use case and the safeguards put in place by the developer and deployer. For example, there’s significantly more risk of using these tools in conversations where sensitive or protected data is shared, and that risk is amplified by using tools that have weak or non-existent safety practices. Put simply, it’s a higher ethical risk (and potentially illegal) decision to use this technology when you’re dealing with sensitive or confidential information.

Does the tool train on user data?

AI “learns” by ingesting and identifying patterns in large amounts of data, and improves its performance over time by making this a continuous process. Companies have an economic incentive to train using your data – it’s a valuable resource they don’t have to pay for. But sharing your data with any provider exposes you and others to potential privacy violations and data leakages, and ultimately it means you lose control of your data. For example, research has shown that there are techniques that cause large language models (LLMs) to reproduce their training data, and AI creates other unique security vulnerabilities for which there aren’t easy solutions.

For most tools, the default setting is to train on user data. Often, tools will position this approach in terms of generosity, in that providing your data helps improve the service for yourself and others. While users who prioritise sharing over security may choose to keep the default, users that place a higher premium on data security should find this setting and turn it off. Whatever you choose, it’s critical to disclose this choice to those you’re recording.

How and where is the data stored and protected?

The process of transcribing and translating can happen on a local machine or in the “cloud” (which is really just a machine somewhere else connected to the internet). The majority will use a third-party cloud service provider, which expands the potential ethical risk surface.

First, does the tool run on infrastructure associated with a company you’re avoiding? For example, many people specifically avoid spending money on Amazon due to concerns about the ethics of their business operations. If this applies to you, you might consider prioritising tools that run locally, or on a provider that better aligns with your values.

Second, what security protocols does the tool provider have in place? Ideally, you’ll want to see that a company has standard certifications such as SOC 2, ISO 27001 and/or ISO 42001, which show an operational commitment to security, privacy, and safety.

Whatever you choose, this information should be a part of your disclosure to meeting attendees.

How am I achieving fully informed consent?

The gold standard for achieving fully informed consent is making the request explicit and opt in as a default. While first-generation notetakers were often included as an “attendee” in meetings, newer tools on the market often provide no way for everyone in the meeting to know that they’re being recorded. If the tool you use isn’t clearly visible or apparent to attendees, the ethical burden of both disclosure and consent gathering falls on you.

This issue isn’t just an ethical one – it’s often a legal one. Depending on where you and attendees are, you might need a persistent record that you’ve gotten affirmative consent to create even a temporary recording. For me, that means I start meeting with the following:

I wanted to let you know that I like to use an AI notetaker during meetings. Our data won’t be used for training, and the tool I use relies on OpenAI and Amazon Web Services. This helps me stay more present, but it’s absolutely fine if you’re not comfortable with this, in which case I’ll take notes by hand.

Doing this might feel a bit awkward or uncomfortable at first, but it’s the first step not only in acting ethically, but modelling that behaviour for others.

Where I landed

Ultimately, I decided that using an AI notetaker in specific circumstances was worth the risk involved for the work I do, but I set some guardrails for myself. I don’t use it for sensitive conversations (especially those involving emotional experiences) or those where confidential data is shared. I start conversations with my disclosure, and offer to share a copy of the notes for both transparency and accuracy.

But perhaps the broader lesson is that I can’t outsource ethics: the incentive structures of the companies producing these tools aren’t often aligned to the values I choose to operate with. But I believe that by normalising these practices, we can take advantage of the benefits of this transformative technology while managing the risks.

AI was used to review research for this piece and served as a constructive initial editor.

BY Aubrey Blanche

Aubrey Blanche is a responsible governance executive with 15 years of impact. An expert in issues of workplace fairness and the ethics of artificial intelligence, her experience spans HR, ESG, communications, and go-to-market strategy. She seeks to question and reimagine the systems that surround us to ensure that all can build a better world. A regular speaker and writer on issues of responsible business, finance, and technology, Blanche has appeared on stages and in media outlets all over the world. As Director of Ethical Advisory & Strategic Partnerships, she leads our engagements with organisational partners looking to bring ethics to the centre of their operations.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Science + Technology, Business + Leadership

3 things we learnt from The Ethics of AI

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Science + Technology

We are being saturated by knowledge. How much is too much?

Explainer

Science + Technology

Thought experiment: “Chinese room” argument

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships, Science + Technology

Periods and vaccines: Teaching women to listen to their bodies

Ask an ethicist: Should I tell my student's parents what they've been confiding in me?

Ask an ethicist: Should I tell my student’s parents what they’ve been confiding in me?

Opinion + AnalysisRelationships

BY John Neil 28 JAN 2026

A high school student has recently confided some personal information. Should I share this confidential information with their parents, even if doing so may breach their trust?

Teachers may be a lot of things, but they’re not therapists, bound by strict confidentiality codes. Nor do they have a parent’s automatic access to everything happening in a child’s life. They occupy a unique middle ground – trusted enough that students tell them things, but facing different calls to make depending on what they hear. A falling-out with friends requires a different response than cyberbullying in a group chat, which differs again from signs of disordered eating or disclosures of abuse. Schools have distinct procedures for each situation, and teachers must balance their duty of care against overreaching into personal advice or counselling – territory that belongs to trained professionals with their own, clearer confidentiality frameworks.

When a student chooses to confide in a teacher, it usually means something. They’ve decided that teacher offers safety. That trust opens up space for them to work through what’s going on, or to practise reaching out for help on their own terms. It’s actually an important part of how young people learn to handle difficult things – sussing out who to talk to and knowing what to share and when. When we decide to share information, the consequence of breaking confidence isn’t a small thing. No doubt you’ve experienced it yourself – we feel betrayed and we shut down. When it comes to students there is a double jeopardy. The message they take away is that confiding in grown-ups isn’t actually safe, that it just gets you in trouble or reported. That’s a lesson that can stick with them for years.

It’s important that a young person’s ownership of their own story is respected. They should be in a position to choose what to tell and what to hold back. But there are obvious limits. If a student discloses that they haven’t eaten in three days, or that they’re scared to go home, those aren’t conversations that can be sat on. ‘Should I respect their privacy?’ is subordinated to ‘what does this child need right now?’ Mandatory reporting laws exist for exactly this reason – confidentiality can’t outweigh safety when the confidential information involves harm to themselves or to others, or if there is serious risk or abuse.

But grey areas remain – especially around confidential information – and context matters enormously. Teachers operate within a formal Duty of Care framework that establishes clear professional and legal obligations, yet this regulatory requirement doesn’t always map neatly onto a teacher’s personal sense of moral duty – what ‘doing right by a student’ feels like in the moment. What that looks like depends enormously on the student. A thirteen-year-old whose parents are still heavily involved in day-to-day decisions is in a different position than a seventeen-year-old who’s six months from being a legal adult. Parents have both a legal and moral stake in their child’s wellbeing, but that argument carries different weight depending on where the child is developmentally and the type of information being shared.

Questions to help clarify the decision

A teacher colleague once described the profession of teaching as ‘ethically rich.’ When facing ethically rich situations, asking some questions may help clarify what’s at stake:

- Is this about something that’s already happened, or something that might happen? The distinction matters. A student venting about a past argument with their mum is different from a student hinting they’re planning to run away.

- Was there a promise or an implication that this would stay confidential? If this is the case, breaking that promise comes with real costs but never at the cost of the student’s or anyone else’s safety.

- If we’re being honest, is the hesitation because of genuine uncertainty, or about dreading an awkward conversation?

- Can the student be involved in what happens next? Could they tell their parents themselves, with the teacher’s support or could they give permission before anyone is contacted?

Principles for navigating the decision

No single rule can cover every situation a teacher might face outside of the legal requirements of mandatory reporting. Here are some ‘rules of thumb’ – ethically informed guidelines that can sometimes help shape how you approach a situation like this without prescribing a rigid answer. They can offer a framework rather than a formula.

Start with the least intrusive option: Many professional codes and guidelines emphasise involving students in disclosure decisions where possible. That doesn’t mean never telling anyone. It means not going over a student’s head unless you have to.

Consult with others before you act: If in any doubt, talking to the school counsellor, year coordinator, or head of year yourself may help you think through options – you don’t have to figure it out alone. Sharing information with colleagues will also help triangulate potential areas of emerging risk.

Know where the legal red lines are: Teachers are mandatory reporters – they have a legal duty to report suspected abuse or neglect. But mandatory reporting is about safety, not general parental notification. Outside those clear-cut situations, there may be more discretion than can sometimes be assumed.

Let them keep some control over the process if you can: Even if disclosure is necessary, a student doesn’t have to feel blindsided. ‘I think your parents need to know about this – would you like to tell them yourself, or would you prefer I do it?’ are very different options than calling a parent out of the blue.

Respect where students are developmentally: Adolescents need to practise regulating what they share with parents as part of healthy development. Routinely overriding a teenager’s choices about disclosure can actually undermine that process. But that doesn’t mean it’s a blank check. Teenagers do need practice deciding what to share and with whom – that’s part of how they learn to navigate adult relationships.

Write things down: Keep a brief, factual record of what was disclosed, what you considered, and what you decided. If questions come up later – from parents, principals, or anyone else – you’ll have a record of what guided your reasoning, and it is typically a legal requirement of your jurisdiction’s Code of Conduct.

BY John Neil

As Director of Education and Innovation at The Ethics Centre, John collaborates closely with a talented team of specialists and subject matter experts to shape the tools, frameworks, and programs that drive our work forward. He brings a rich and varied background as a consultant, lecturer, and researcher, with expertise spanning ethics, cultural studies, sustainability, and innovation. This multidisciplinary perspective allows him to introduce fresh, thought-provoking approaches that energise and inspire our initiatives. John has partnered with some of Australia’s largest organisations across diverse industries, to place ethics at the heart of organisational life. His work focuses on education, cultural alignment, and leadership development to foster meaningful and lasting impact.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Explainer

Relationships, Society + Culture

Ethics Explainer: Ethical non-monogamy

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Authenticity

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

On saying “sorry” most readily, when we least need to

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture, Relationships

Discomfort isn’t dangerous, but avoiding it could be

Does 'The Traitors' prove we're all secretly selfish, evil people?

Does ‘The Traitors’ prove we’re all secretly selfish, evil people?

Opinion + AnalysisSociety + Culture

BY Joseph Earp 21 JAN 2026

For decades, Alan Carr has been one of British TV’s most unfailingly friendly faces. He’s carved out his niche thanks to a persona modelled on your best friend after a few chardonnays; fun and occasionally rude, but always deeply, resolutely kind. Which is precisely why his maniacal turn on Celebrity Traitors was such a headline-grabbing event.

The highly successful reality show is essentially a glorified game of heads down thumbs up: out of a group of contestants, a select few are secretly designated as “the traitors”, able to dispatch other contestants. The non-traitors must work together to identify the bad apples in their midst – if they do, then they walk home with prize money. If they don’t, then the traitors win.

Almost as soon as he discovered he was a traitor, Carr went to work dispatching his other contestants with a single-minded intent. In an early shocking moment, he even booted off his real-life good mate Paloma Faith, the speed and severity with which he went about his work rivalled only by his masterful manipulation of those around him. Time and time again, he actively leveraged his kindly persona, playing up his inherent trustworthiness. And in the face of accusations, he pleaded his innocence.

It worked. Carr ended up walking away with the biggest haul of the season – but not without breaking down in tears, a sudden flash of guilt overwhelming him.

Which begs the question: does self-interested behaviour actually benefit the self? And moreover, is it really true that when given the slightest motivation for unethical action, most of us would sell out, and “murder” our best mate?

The social contract and the state of nature

The question of what incentive people have to remain ethical is oft-debated in the annals of philosophy. One answer, provided by the philosopher Thomas Hobbes, is based on the perceived inherent nastiness at the heart of human beings. According to Hobbes, we organise ourselves into societies where we all agree not to harm or steal from one another, in order to avoid what he called “the state of nature.”

According to Hobbes, the state of nature is a fundamentally lawless societal structure, where individuals do what they want, when they want: this, he says, is how it goes in the natural world, where birds steal each other’s eggs, and lions tear sick zebras limb from limb. There’s total freedom in the state of nature, sure, but it’s not particularly pleasant.

The social contract is a means, therefore, of playing to people’s self-preservation drive, rather than their compassion for their fellow human beings. In the social contract, we all collectively agree not to harm or steal from the other, but only because we want to ensure a world where they don’t harm or steal from us. On this picture of human nature, we’re all chomping at the bit to go full Alan Carr, and betray those around us for our own good – but we don’t, simply in order to avoid getting Alan Carr’d by someone else.

One second away from nastiness

This belief in our fundamentally selfish nature was reinforced throughout the post-war period, where a number of psychological studies aimed to prove that human beings will unleash unkindness with only the lightest of pressures. The most famous such study was the Stanford Prison Experiment, where a group of unassuming civilians were ordered to roleplay being either a jailor or an inmate. Quickly, the jailors went mad with power, escalating the roleplay to such a dangerous level that the whole experiment had to be aborted.

The Stanford Prison Experiment was precisely so shocking because the jailors didn’t even have a pot of gold waiting for them at the end of the experiment: they appeared to wield their power for no other reason than they enjoyed it.

A similar conclusion was reached with the Milgram experiment. In that trial, a group of random civilians were ever-so-gently pressured into delivering what they believed were fatal electric shocks to other civilians that were getting answers in a test wrong (the whole thing was actually a set-up; no-one was harmed). Almost all of them went along with the proceedings happily.

Take these conclusions, and the likes of Alan Carr don’t seem as much like the exception to the rule, but the rule itself.

The better angels of our nature

But should we accept these conclusions? For a start, it’s worth noting that participants in the Stanford Prison Experiment were explicitly instructed to behave badly: it wasn’t something that they came up with by themselves. And in the face of Rousseau’s fundamentally lonely and cruel picture of humanity, let’s consider our extraordinary capacity for empathy.

Because here’s the thing: while we do have evidence that people can be led away from their fundamental values by either money or pressure from an authority figure, a la the Milgram experiment, we also have a great deal of evidence that most people feel an automatic, unthinking empathy towards their fellow human beings. Even Philip Zimbardo, one of the key architects of the Stanford Prison Experiment, advanced the theory of “the banality of heroism”. According to such a view, we all have unbelievable reserves of courage and fellow-feeling within us – heroic acts aren’t, actually, outside of the norm, but something that we’re all capable of.

It is worth noting, after all, that people who are led to act in a self-interested way are exactly that: led astray. Without intervention, people have a fundamentally collective view of humanity. Sure, we can be manipulated. But we all have a natural, unthinking goodness.

Which might then explain Alan Carr’s tears at the end of the traitors. While it’s true he was incentivised to behave “badly”, he knew that it was bad. And in an era where individualism and egomania is being pushed down our throats more than ever, we should remember that within us lies a strong sense of right and wrong, and a deep reserve of concern for our fellow human beings – Rousseau be damned.

BY Joseph Earp

Joseph Earp is a poet, journalist and philosophy student. He is currently undertaking his PhD at the University of Sydney, studying the work of David Hume.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

Inside The Mind Of FODI Festival Director Danielle Harvey

Big thinker

Relationships, Society + Culture

Big Thinker: Simone de Beauvoir

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

A parade of vices: Which Succession horror story are you?

Explainer

Society + Culture

Ethics Explainer: Aesthetics

Play the ball, not the person: After Bondi and the ethics of free speech

Play the ball, not the person: After Bondi and the ethics of free speech

Opinion + AnalysisPolitics + Human RightsSociety + Culture

BY Simon Longstaff 15 JAN 2026

The sequence of events that led to the cancellation of Adelaide Writers Week revolve around two central questions. First, what, if any, should be the limits of free speech? Second, what, if anything, should disqualify a person from being heard? In the aftermath of the Bondi Terror Attack, the urgency in answering these questions has seen the Commonwealth Parliament recalled specifically to debate proposed legislation that will, amongst other things, redefine how the law answers such questions.

Beyond the law, what does ethics have to say about such fundamental matters in which freedom, justice and security are in obvious tension?

I have consistently argued for the following position. First, there should be a rebuttable presumption in favour of free speech. That is, our ‘default’ position is that there should be as much free speech as possible. However, I have always set two ‘boundary conditions’. First, there should be a strict prohibition against speech that calls into question or denies the intrinsic dignity and humanity of another person. Anything that implies that one person is not as fully human as another would be proscribed. This is because every human rights abuse – up to and especially including genocide – begins with the denial of the target’s humanity. It is this denial that makes it possible for people to do to others what would otherwise be inconceivable. Second, I would prohibit speech that incites violence against an individual or group.

As will be obvious, these are fairly minimal restrictions. They still leave room for people to cause offense, to harangue, to stoke prejudice, to make people feel unsafe, and so on. That is why I have come to the view that something more is needed. In the past, I have struggled to find a principle that would allow for the degree of free speech that is needed to preserve a vibrant, liberal democracy while, at the same time, limiting the harm done by those who seek to wound individuals, groups or the whole of society by means of what they say.

In particular, how do you respond to someone who foments hatred of others – but falls just short of denying their humanity?

It recently occurred to me that the principle I have been looking for can be found in the most unlikely of places: the football field. I was never any good at sport and was always the obvious ‘weak link’ in any team. So, I took a particular interest in the maxim that one should “play the ball and not the person”. Of course, the idea is not exclusively one for sport. Philosophy has long decried the validity of the ad hominem argument – where you attack the person advancing an argument rather than tackle the idea itself. Christianity teaches one to ‘loathe the sin and love the sinner’. In any case, whether one takes the idea from the football field or the list of logical fallacies or from a religion, the idea is pretty easy to ‘get’. In essence: feel free to discuss what is being done – condemn the conduct if you think this justified. However, with one possible exception, do not attack those whom you believe to be responsible.

The one possible exception relates to those in positions of power – where a decent dose of satire is never wasted. That said, the powerful can make bad decisions without being bad people – and calling their integrity into question is often cruel and unjustified. Beyond this, if powerful people preside over wrongdoing, then let the courts and tribunals hold them to account.

The ‘play the ball’ principle commends itself as a practical tool for distinguishing between what should and should not be said in a society that is trying to balance a commitment to free speech with a commitment to avoid causing harm to others. It is especially important that this curbs the tendency of ‘bad faith’ actors (especially those with power) to cultivate an association between certain ideas and certain people. For example, we see this when someone who merely questions a political, religious or cultural practice is labelled as a ‘bigot’ (or worse).

In practice, we will now explicitly apply the ‘play the ball’ principle when curating of the Festival of Dangerous Ideas (FODI) – adding it to the matrix of issues we take into account when developing and presenting the program. FODI seeks to create spaces where it is ‘safe to’ encounter challenging ideas. For example, it should be possible to discuss events such as: the civic rebellion and repression in Iran, the Russian war with Ukraine, Israel’s response to Hamas’ terror attack, and so on … without attacking Iranians, Shia, Russians, Ukrainians, Israelis or Palestinians. Indeed, I think most Australians want to be able to discuss the issues – no matter how challenging – knowing that they will not be targeted, shunned or condemned for doing so.

I recognise that there are a couple of weaknesses in what I have outlined above. First, I know that some people identify so closely with an idea that they feel personally attacked even by the most sincerely directed question or comment.

Yet, in my opinion, a measure of discomfort should not be enough to silence the question. We all need to be mature enough to distinguish between challenges to our beliefs and threats to our identity.

Second, while the prohibition against the incitement of violence is clear, the other two I have proposed are much more ambiguous. As such, they might be difficult to codify in law.

Even so, these are principles that I think can be applied in practice – especially if we are all willing to think before we speak. A civil society depends on it.

BY Simon Longstaff

Simon Longstaff began his working life on Groote Eylandt in the Northern Territory of Australia. He is proud of his kinship ties to the Anindilyakwa people. After a period studying law in Sydney and teaching in Tasmania, he pursued postgraduate studies as a Member of Magdalene College, Cambridge. In 1991, Simon commenced his work as the first Executive Director of The Ethics Centre. In 2013, he was made an officer of the Order of Australia (AO) for “distinguished service to the community through the promotion of ethical standards in governance and business, to improving corporate responsibility, and to philosophy.” Simon is an Adjunct Professor of the Australian Graduate School of Management at UNSW, a Fellow of CPA Australia, the Royal Society of NSW and the Australian Risk Policy Institute.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

To Russia, without love: Are sanctions ethical?

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

If we’re going to build a better world, we need a better kind of ethics

Big thinker

Relationships, Society + Culture

Big Thinker: Simone de Beauvoir

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture

Trying to make sense of senseless acts of violence is a natural response – but not always the best one

Ethics Explainer: Ethical non-monogamy

Ethics Explainer: Ethical non-monogamy

ExplainerRelationshipsSociety + Culture

BY The Ethics Centre 14 JAN 2026

Ethical non-monogamy (ENM), also known as consensual non-monogamy, describes practices that involve multiple concurrent romantic and/or sexual relationships.

What it’s not

First up, it’s important to distinguish the two types of non-monogamy that are often conflated with ENM:

Polygamy, the most prominent kind of culturally institutionalised non-monogamy, is the practice of having multiple marriages. It is a historically significant practice, with hundreds of societies around the world having practiced it at some point, while many still do.

Infidelity, or non-consensual non-monogamy, is something we colloquially refer to as cheating. That is, when one or both partners in a monogamous relationship engage in various forms of intimacy outside of the relationship without the knowledge or consent of the other.

All-party consent

So, what makes ethical non-monogamy, then?

One of the defining features of ethical non-monogamy is its focus on consent.

Polygamy, while it can be consensual in theory, more often occurs alongside arranged marriages, child marriages, dowries and other practices that revoke the autonomy of women and girls. Infidelity is of course inherently non-consensual, but the reasons and ways that it happens inversely influence ENM practices.

Consent needs to be informed, voluntary and active. This means that all people involved in ENM relationships need to understand the dynamics they’re involved in, are not being emotionally or physically coerced into agreement, and are explicitly assenting to the arrangement.

Open communication

There are a multitude of ways that ENM relationships can operate, but each of them relies on a foundation of honesty and effective communication (the basis of informed consent). This often means communicating openly about things that are seen as taboo or unusual in monogamous relationships – attraction to others, romantic or sexual plans with others, feelings of jealousy, vulnerability, or inadequacy.

While all ENM relationships require this commitment to open communication and consent, there can be variation in how that looks based on the kind of relationship dynamic. They’re often broken up into broad categories of polyamory, open relationships, and relationship anarchy.

Polyamory refers to having multiple romantic relationships concurrently. Maintaining ethical polyamorous relationships involves ongoing communication with all partners to ensure that everyone understands the boundaries and expectations of each relationship. Polyamory can look like a throuple, or five people all in a relationship with each other, or one person in a relationship with three separate people, or any other number of configurations that work for the people involved.

Open relationships are focused more on the sexual aspects, where usually one primary couple will maintain the sole romantic relationship but agree to having sexual experiences outside of the relationship. While many still rely on continued communication, there is a subset of open relationships that operate on a “don’t ask, don’t tell” policy. This usually involves consenting to seeking sexual partners outside of the relationship but agreeing to keep the details private. Swinging is also a popular form of open relationship, where monoamorous (romantically exclusive) couples have sexual relations with other couples.

Relationship anarchy rejects most conventional labels and structures, including some of the ones that polyamorous relationships sometimes rely on, like hierarchy. Instead, these relationships are based on personal agreements between each individual partner.

What all of these have in common is a firm commitment to communicating needs, expectations, boundaries and emotions in a respectful way.

These are also the hallmarks of a good monogamous relationship, but the need for them in ethical non-monogamy is compounded by the extra variables that come with multiple relationship dynamics simultaneously.

There are many other aspects of ethical relationship development that are emphasised in ethical non-monogamy but equally important and applicable to monogamous ones. These includes things like understanding and managing emotions, especially jealousy, and practicing safe sex.

Outside the relationships

Unconventional relationships are unrecognised in the law in most countries. This poses ethical challenges to current laws, including things like marriage, inheritance, hospital visitation, and adoption.

If consenting adults are in a relationship that looks different to the monogamous ones most laws are set around, is it ethical to exclude them from the benefits that they would otherwise have? Given the difficultly that monogamous queer relationships have faced and continue to face under the law in many countries, non-monogamy seems to be a long way from legal recognition. But it’s worth asking, why?

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture

Lisa Frank and the ethics of copyright

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

A new era of reckoning: Teela Reid on The Voice to Parliament

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships

Can you incentivise ethical behaviour?

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Conscience

Unrealistic: The ethics of Trump’s foreign policy

Unrealistic: The ethics of Trump’s foreign policy

Opinion + AnalysisPolitics + Human Rights

BY Dr. Gwilym David Blunt 12 JAN 2026

‘We live in a world, in the real world… that is governed by strength, that is governed by force, that is governed by power. These are the iron laws of the world that have existed since the beginning of time.’ These are the words of Stephen Miller, Deputy Chief of Staff in the Trump White House, while refusing to rule out the possibility of the United States annexing Greenland.

Miller is not an isolated voice. President Trump has escalated his annexationist rhetoric about Greenland as essential to American security and has said that they will ‘take’ the Danish territory whether they ‘like it or not.’

These sentiments have a striking similarity to what the historian and general Thucydides wrote during the Peloponnesian War over two thousand years ago:

‘You know as well as we do that right, as the world goes, is only in question between equals in powers, while the strong do what they can and the weak suffer what they must.’

This is the foundation of realism, a philosophy of foreign affairs. It claims that in an anarchic international system, the only rational policy for a state is to pursue its own security by having more power than its neighbours. This is because, in the absence of a world state, power is the final arbiter of disagreements between states.

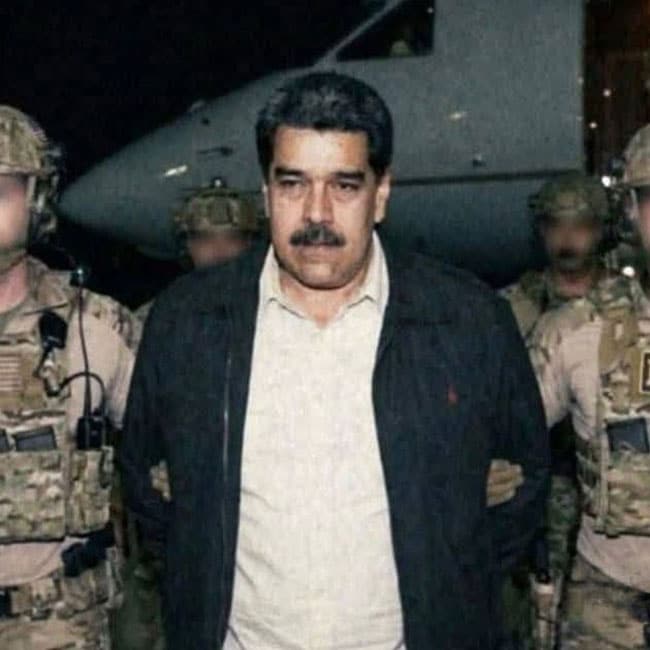

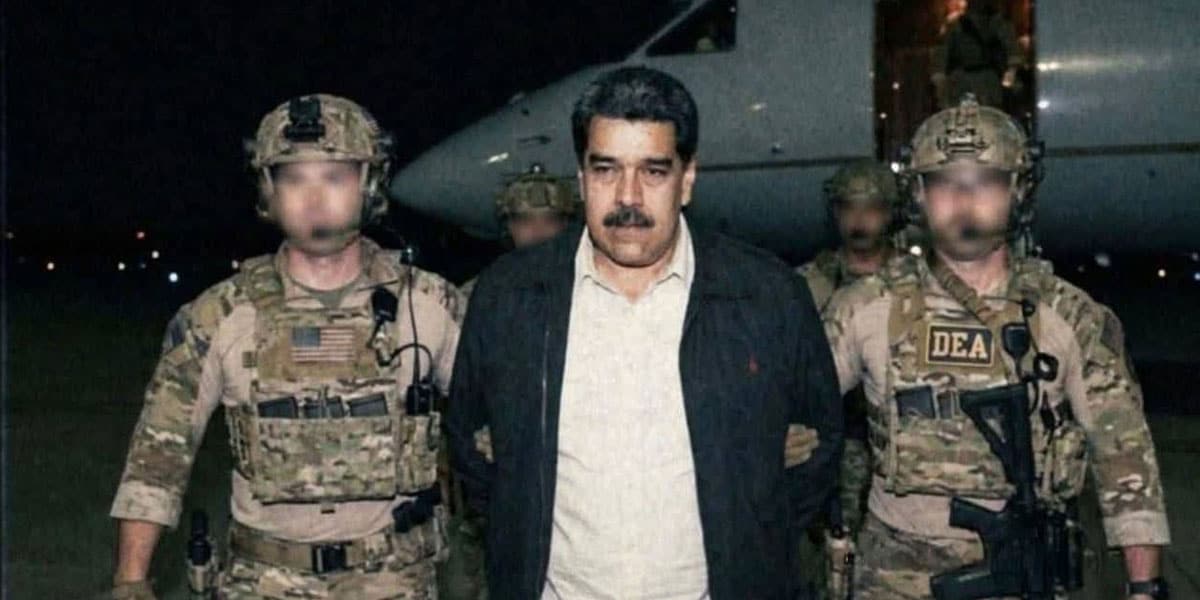

On the back of the abduction of then-Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro and the Trump administration’s apparent willingness to allow Ukraine to be subsumed into a Russian sphere of influence, it seems a new realism has taken root in American foreign policy. It is one that has pushed away ethical concerns about human rights and international law and embraced pure power politics. Might makes right, and weaker countries like Venezuela, Denmark, and perhaps Canada must accept their place as mere vassals of Washington.

The problem is that Miller and Trump are not good realists.

Realism is not amoral or unethical. It has an ethical core that is practical, modest, and conservative. Realist ethics do not license something as reckless as kidnapping foreign heads of state, fracturing NATO to seize Greenland, or letting an aggressive rival menace allies. These are acts of bravado, performative and imprudent. Such actions invite unintended and unpleasant consequences.

The vulgar realism of the Trump administration would have appalled Hans Morgenthau, one of the founders of modern realism and advisor to Presidents Kennedy and Johnson. Although he was attentive to power, Morgenthau never said that there was no such thing as ethics in international politics, but rather that it has a distinct set of ethics that requires a balance of power and principle. He wrote in Politics Among Nations:

‘A man who was nothing but ‘political man’ would be a beast, for he would be completely lacking in moral restraints. A man who was nothing but ‘moral man’ would be a fool, for he would be completely lacking in prudence’

Realist ethics are about survival and security in a complex, dangerous, and unpredictable world. It is wary of transcendent ideas about universal morality because of the crusader spirit they engender. Morgenthau was deeply worried that zealots on both sides of the Cold War might start a nuclear war in the name of democracy or Marxism-Leninism to the detriment of all humanity.

Likewise, the unethical bestial pursuit of power also invites disaster because it can result in a loss of the very thing it seeks to gain. Miller clearly never finished Thucydides’ The History of the Peloponnesian War (and Trump probably has no idea what it is). Athens lost the war and Sparta imposed a harsh peace. The words of the ‘Melian Dialogue’ quoted above serve to highlight the hubris of Athens. They frightened neutral states with their brutality, alienated allies with their high-handedness, and convinced of their own superiority made disastrous military adventures, such as the Sicilian Expedition, which ultimately diminished their power and prestige. In acting like Morgenthau’s beast they authored their own downfall. Hubris and tragedy are themes in the realist tradition.

The actions of the Trump administration threaten to undo the undeniable triumph of American foreign policy which was to turn the wealthy democracies of Europe into dependent but dependable allies. It invites a future where NATO has dissolved, but a rearmed, independent, and unified Europe has taken its place and that views the United States as an unreliable or even hostile power. The consequences of this shift cannot be overstated. A united Europe would have an economy five times the size of India, ten times the size of Russia, and comparable to China in nominal GDP. It would be able to check American influence, especially if it acted in concert with China. America would no longer be a hegemonic power, but simply a great power in an unstable multipolar order.

Hubris, tragedy and an object lesson on how not to be a realist.

BY Dr. Gwilym David Blunt

Dr. Gwilym David Blunt is a Fellow of the Ethics Centre, Lecturer in International Relations at the University of Sydney, and Senior Research Fellow of the Centre for International Policy Studies. He has held appointments at the University of Cambridge and City, University of London. His research focuses on theories of justice, global inequality, and ethics in a non-ideal world.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Reports

Politics + Human Rights

Ethical by Design: Evaluating Outcomes

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

Ask an ethicist: Why should I vote when everyone sucks?

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

Nurses and naked photos

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights