Ethics Explainer: Values

On any given day, each of us will experience a rush of emotion and make a decision based on our gut reaction, intuition, or conscience. Someone spits on the street and our ‘against the rules’ or ‘hygiene’ button gets pushed. We see a photo of a child powerless and mistreated and our ‘justice fire’ gets lit.

This gut reaction is an emotional expression of our deeply held beliefs about what we value as right and good. Our values describe what we want to see in the world and how we should behave. This set of views about what is right and wrong is sometimes referred to as our moral compass.

We each hold a personal system of values arranged in order of priority. For example, some people may prioritise personal freedom over security and other people will do the opposite. Many people also hold a collective value system, reflecting a cultural or societal attitude. These different value sets vary in terms of how cohesive they are – they might be complementary or contradictory.

Scholars have categorised values in various ways – religious, political, aesthetic, social, ethical, moral, and so on. One study found ten distinct values recognised across different cultures: power, achievement, hedonism, stimulation, self-direction, universalism, benevolence, tradition, conformity and security.

Values inform and influence our attitudes, choices and behaviours. They provide both conscious and unconscious guidelines for the goals we pursue, how we pursue them, our perceptions of reality, and the ways we engage in the world.

Where do our values come from?

Your values reflect how, where and when you were raised. They are generally received through culture, often transmitted between parents and children. We also learn from the stories we read, things we watch, life challenges, and through experiences of the morally authoritative people in our lives.

Our value system forms when we are young and unaware of what is going on and continues developing throughout our lives, with conscious self-correction and moral development. As we grow older, it can be difficult to shift deep seated values that are no longer appropriate or relevant. But thanks to our capacity for critical discernment, our values are never entirely ‘fixed’.

Why do different people value different things?

Because people grow up in different families with different backgrounds and histories, personal values differ from one person to the next. However, shared experiences lead to some common values. There are more shared values, norms, and patterns of behaviour between of people in the same environment – be it a community, an organisation, a country, or a football team.

Even the same values can look different when practiced by different cultures. For instance, wearing black to a funeral is a mark of respect for human life in some cultures while in others, mourners wear white. Each share the same value – respect for the dead – but the norms surrounding the value differ.

What do we do when values clash?

Have you found yourself torn between telling the truth and avoiding upsetting someone else? Have you ever felt unsure about how to respond to someone with a different value set to your own?

When we face these conflicts, we’ve entered ‘the ethics zone’ and we have to decide what we should do. The process of engaging with the clash involves examining gut reactions, considering other perspectives, consulting with trusted mentors, being open to alternative viewpoints and possibilities, and critically examining our feelings.

The more we engage in this kind of process of ethical reasoning, the better we get at it. This approach strengthens our muscle for ethical decision making so we can respond when our values are in tension. Instead of relying on an unexamined ‘gut instinct’, we hone an informed and reflective conscience to negotiate ethical tension and conflicts of values.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing

Democracy is hidden in the data

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Trust

Big thinker

Relationships

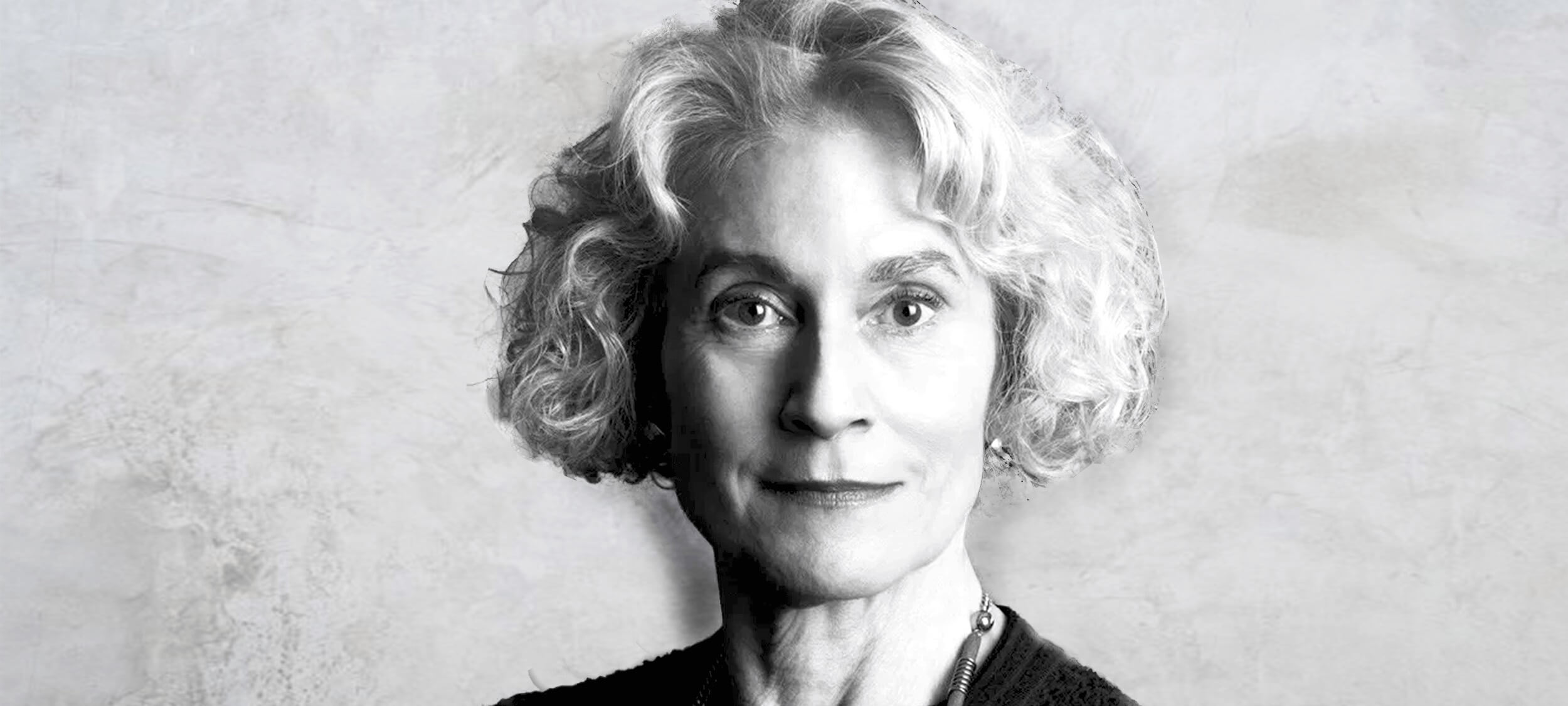

Big Thinker: Martha Nussbaum

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

The truths COVID revealed about consumerism

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

I’m an expert on PTSD and war trauma but I won’t do the 22 push up challenge

I’m an expert on PTSD and war trauma but I won’t do the 22 push up challenge

Opinion + AnalysisHealth + Wellbeing

BY Nikki Coleman The Ethics Centre 27 SEP 2016

I’ve taught thousands of brave men and women at the Australian Defence Force Academy for the past six years. I’ve cooked for many of them in my home and shared a river of tea and coffee with others.

Many have been broken by their experiences in the military – for some I have literally taken the rope from around their neck, the pill bottle from their hands and talked them off the edge of a cliff. They are the walking wounded the Prime Minister is seeking to help.

Given all this, it was no surprise a friend invited me to complete the ‘22 push-up challenge’, a campaign to raise money and awareness for PTSD. 22 push ups for 22 days to represent the 22 veterans killed by suicide according to the US Department of Veterans Affairs.

But I’m not going to take part in the 22 push up challenge.

I’m a philosopher currently completing a PhD on the subjects of veteran PTSD and moral injury, so I understand the importance of awareness and support for soldiers currently serving, as well as veterans after they leave the ADF. Awareness raising is crucial for veterans because the feelings of isolation and disconnection from the civilian community can exacerbate the severity of mental health issues proceeding from trauma.

It also reflects on us as a community how well we are willing to care for those who have put their lives on the line to protect our country or innocent people overseas. Our wounded vets deserve the very best treatment, the very best care. They and their families risk everything for our safety. It goes without saying they deserve treatment to help them to heal. But although the treatment for Australian veterans with mental health issues like PTSD could be better, it is much better than for anyone else with PTSD.

Veterans are overrepresented in media coverage and funding allocations to do with trauma and mental health.

Last year a non-veteran family member suffered from PTSD. They were on suicide watch, requiring me to work from home and balance professional commitments, my academic research and the crucial task of preventing a loved one from dying. During this time hospital services were unavailable – in practice, it feels like there is simply nowhere for non-veterans to go.

If they were a veteran, it would have been different. There are specialised treatment facilities available for them, which I know because we were turned away from each of them.

I take no issue with the fact treatment is available for veterans. As I’ve said, they deserve more than what is presently available to them. However, the media attention provided to veterans is vastly disproportionate to the actual experience of trauma-related mental illness in Australia.

Most cases of PTSD are those recovering from rape and sexual abuse and the majority of sufferers are women. The majority of patients are men, in part because it could re-traumatise female survivors of sexual abuse to be in therapy with men and in part because the professions who tend to receive trauma support are male dominated. Most of our treatment facilities are also allocated for veterans with PTSD, largely because places in these treatment programs are funded by the DVA and veteran-based charities. In short, veterans are overrepresented in media coverage and funding allocations to do with trauma and mental health.

It’s not obvious why a certain group should enjoy special privileges in the civilian healthcare system.

The government recently announced a new suicide prevention initiative for ADF personnel and while it’s true there is also a broader focus on suicide prevention, women’s shelters and rape crisis centres continue to battle for funding despite the strong association between sexual assault and mental health issues.

This seems to fly in the face of standard medical ethical principles, which suggest treatment is provided on the basis of need rather than the social status of the patient. These principles would suggest the cause of trauma – whether war, sexual assault or otherwise – should have no bearing on whether a patient receives treatment in a civilian facility.

While we can make exceptions in cases where the ADF provides special support to its men and women, it’s not obvious why a certain group should enjoy special privileges in the civilian healthcare system. Those suffering the same condition are in equal need of care.

If the recent Royal Commission into Institutional Child Abuse has taught us anything, it’s how many people with severe trauma suffer in silence, unable to access the support they critically need. It’s not clear to me that veterans are the ones most desperately in need of increased awareness.

One of the advantages of awareness raising is its ability to reduce the stigma surrounding mental health and trauma. In the ADF this is crucial, because research suggests there are still high levels of stigma surrounding PTSD in our defence forces.

In the desire to fix this problem we need to be careful not to generate another one. If all our awareness-raising efforts around PTSD are focused on veterans, we risk invalidating the experiences of those suffering trauma-related mental health issues who have never been to war.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Philosophy must (and can) thrive outside universities

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Health + Wellbeing

The super loophole being exploited by the gig economy

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Health + Wellbeing

Why ethical leadership needs to be practiced before a crisis

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Duties of care: How to find balance in the care you give

BY Nikki Coleman

Nikki Coleman is a PhD Candidate and researcher with the Australian Centre for the Study of Armed Conflict and Society at UNSW Canberra. In her free time she is the “Canberra Mum” to many officer cadets and midshipmen at ADFA.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Send in the clowns: The ethics of comedy

Send in the clowns: The ethics of comedy

Opinion + AnalysisHealth + WellbeingRelationships

BY The Ethics Centre 21 SEP 2016

We’ve all heard jokes that were ‘too soon’ or went ‘too far’. Maybe you laughed hysterically or maybe you were offended. We asked a few comedians how they negotiate the thorny side of humour.

Avoid lazy stereotypes

“It’s easy to be lazy because so much comedy comes from stereotypes … but there is more interesting humour found by digging deeper”, says Suren Jayemanne. By focusing on the absurdity of the stereotype rather than the stereotype itself, you can laugh with the subject of the joke rather than at them.

Jayemanne uses the example of Indian taxi drivers. “The reason is because so many of their qualifications aren’t recognised, so the stereotype is one we’ve imposed on them as a society.” So instead of making fun of Indian cab drivers, he jokes about using them as a chance to get a cheap second medical opinion.

For Karen Edwards, the use of stereotypes really depends on the audience. As an Aboriginal comedian, she thinks stereotypes can be relatable. “I use [Aboriginal] stereotypes in front of our own mob and they find it relatable – if blackfellas won’t be offended by a joke then I’ll run with it.”

This means she still avoids the more offensive, lazy stereotypes, “like petrol sniffers – that’s offensive even if it’s said by an Aboriginal”.

Free speech doesn’t mean you should run your mouth

“Some people think free speech in comedy means they should be able to say anything that pops into their head on stage – that’s crazy to me,” says Tom Ballard.

“The big conversation in comedy right now seems to be about political correctness, the restrictions on free speech, how our jokes reflect on us as comedians and which jokes are worth saying”, he adds. “If we’re talking about stuff about which we have no experience … is our dumb joke worth it given the offence it might cause to people who have?”

The free speech defence can also be used as a cop-out, says Bish Marzook. “The people who are calling out the comedians also have the right to free speech – you have a right to say you didn’t find their joke funny.”

“If you have absolute free speech you’re probably restricting other essential rights as well,” adds Jayemanne.

Punch up, not down

Jayemanne explains how comedians have become mindful of not piling on to groups who are already struggling against social issues. “I think because you’ve got a pulpit to speak from, it’s important to be conscious of who the victim of your joke is.”

“You don’t want to be part of the problem,” says Ballard. Sometimes that means thinking carefully about whether your joke is consistent with the kind of society you want to create. Take Islam, for instance.

“I’m not a fan of religion, I’m an atheist – but I’m also a white man in a climate where apparently 49 percent of Australians support a ban on Muslim immigration… I don’t want to contribute to the victimisation and abuse of those people.”

Comedy takes topics most people would assume are taboo or tragic and turns it into something cathartic.

I ask whether avoiding punching down meant comedians needed to have a kind of ‘oppression hierarchy’ to know who sat below them on the pecking order. Marzook admits it can be hard.

“I identify as a person of colour and a woman, so I know there are things I can say but I also have a lot of privileges people don’t know about.”

“Just because you’re conscious of punching down doesn’t mean you can’t talk about disadvantage,” adds Ballard, whose last show Boundless Plains to Share focused on asylum-seeker politics. “I wanted to talk about refugees… but in terms of the ‘punch’, it was always about the people in power.”

Are some topics off-limits?

Edwards thinks some topics shouldn’t be the subject of comedy. “No matter how funny, there are certain things I’d never touch. I’m not going to make jokes about babies dying… like all the ‘dingo ate my baby’ jokes – why? It’s too tragic.”

For Marzook, it depends on the context – are you saying something funny and thoughtful?

“The reason I went into comedy is to make a point of what’s happening in the world… I would encourage people to tackle hard issues. If it’s racist or untrue then that’s the problem and someone should point it out.”

Ballard thinks the idea of off-limits topics is “a tired angle”.

“We know comedians like Amy Schumer, Jon Stewart and Chris Rock exist – it’s pretty settled that edgy comedy is possible,” he says.

Even so, at a certain point in his last show on asylum seekers, he couldn’t make jokes. “There were some things about the nature of the system that I simply couldn’t make funny and so the show became more earnest and theatrical. At a point I just had to say this is fucked up.”

“I think an ethical comedian is one who listens and takes seriously the possibility of offence.” – Tom Ballard

Jayemanne thinks comedy needs to tackle the hard stuff, and that people want comedians to do so. “Comedy takes topics most people would assume are taboo or tragic and turns it into something cathartic. If you shy away you’re sheltering people, but humour is such an important tool for helping people deal with difficult topics.”

“It helps make the medicine go down,” adds Ballard.

Listen to your audience and be forgiving

“Comedy is about truth and, to an extent, egalitarianism. It’s a social, communal thing,” says Ballard. “I think an ethical comedian is one who listens and takes seriously the possibility of offending – there are things to be learned from the audience.”

Marzook worries comedians will shy away from serious issues because the costs of getting it wrong can be so severe. “Now everyone is so scared of making a mistake, and they should be, but if the consequences weren’t so severe, like online shaming, losing your job… maybe people would be willing to admit they made a mistake and we could move on.

“I guess it’s just about doing your best.”

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Enough with the ancients: it’s time to listen to young people

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Breaking news: Why it’s OK to tune out of the news

Big thinker

Health + Wellbeing, Politics + Human Rights

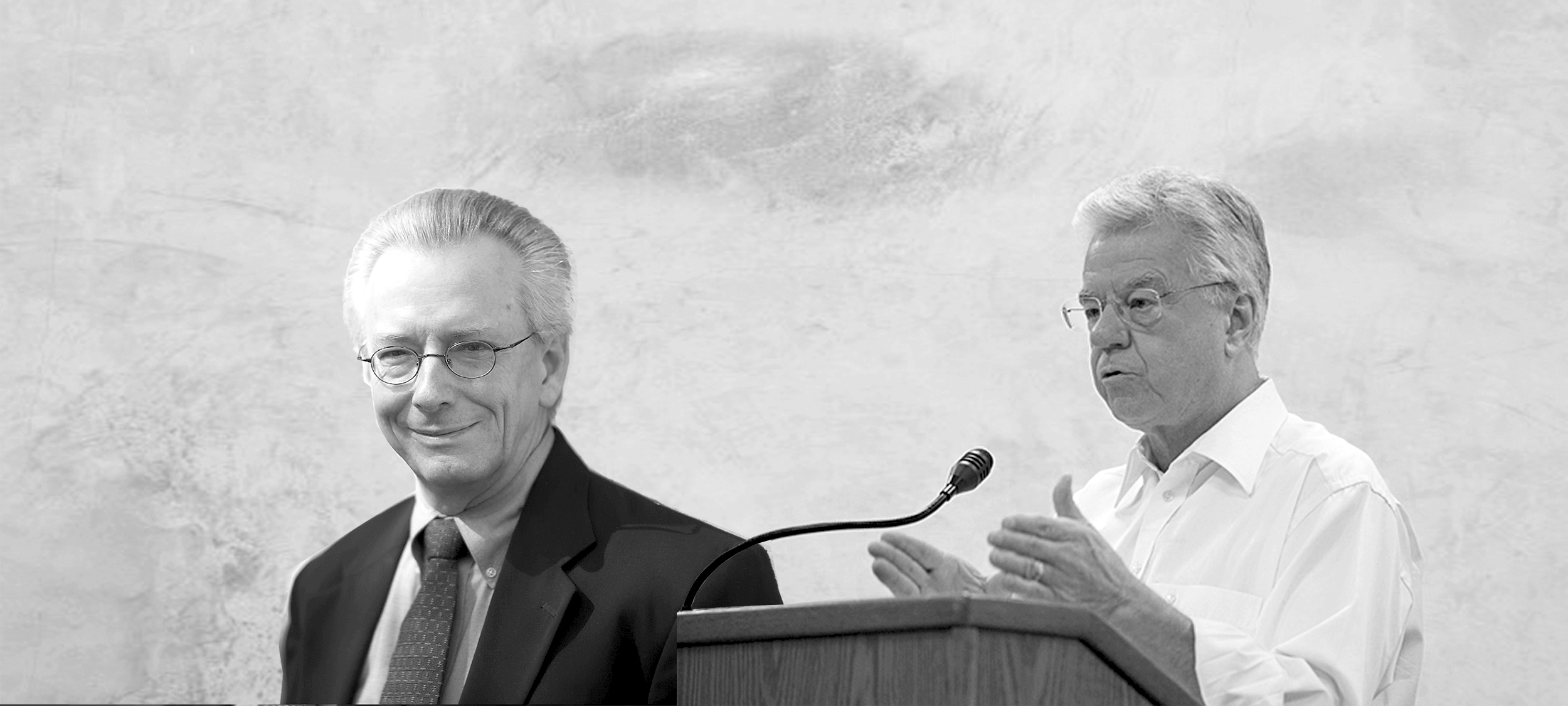

Big Thinkers: Thomas Beauchamp & James Childress

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Ethical dilemma: how important is the truth?

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Twitter made me do it!

Twitter made me do it!

Opinion + AnalysisHealth + WellbeingScience + Technology

BY Michael Salter The Ethics Centre 5 SEP 2016

In a recent panel discussion, academic and former journalist Emma Jane described what happened when she first included her email address at the end of her newspaper column in the late nineties.

Previously, she’d received ‘hate mail’ in the form of relatively polite and well-written letters but once her email address was public, there was a dramatic escalation in its frequency and severity. Jane coined the term ‘Rapeglish’ to describe the visceral rhetoric of threats, misogyny and sexual violence that characterises much of the online communication directed at women and girls.

Online misogyny and abuse has emerged as a major threat to the free and equal public participation of women in public debate – not just online, but in the media generally. Amanda Collinge, producer of the influential ABC panel show Q&A, revealed earlier this year that high profile women have declined to appear in the program due to “the well-founded fear that the online abuse and harassment they already suffer will increase”.

Twitter’s mechanics mean users have no control over who replies to their tweets and cannot remove abusive or defamatory responses.

Most explanations for online misogyny and prejudice tend to be cultural. We are told that the internet gives expression to or amplifies existing prejudice – showing us the way we always were. But this doesn’t explain why some online platforms have a greater problem with online abuse than others. If the internet were simply a mirror for the woes of society, we could expect to see similar levels of abuse across all online platforms.

The ‘honeypot for assholes’

This isn’t the case. Though it isn’t perfect, Facebook has a relatively low rate of online abuse compared to Twitter, which was recently described as a “honeypot for assholes”. One study found 88 percent of all discriminatory or hateful social media content originates on Twitter.

Twitter’s abuse problem illustrates how culture and technology are inextricably linked. In 2012, Tony Wang, then UK general manager of Twitter, described the organisation as “the free speech wing of the free speech party”. This reflects a libertarian commitment to uncensored information and rampant individualism, which has been a long-standing feature of computing and engineering culture – as revealed in the design and administration of Twitter.

Twitter’s mechanics mean users have no control over who replies to their tweets and cannot remove abusive or defamatory responses, which makes it an inherently combative medium. Users complaining of abuse have found that Twitter’s safety team does not view explicit threats of rape, death or blackmail as a violation of their terms of service.

The naïve notion that Twitter users should battle one another within a ‘marketplace of ideas’ . . . ignores the way sexism, racism and other forms of prejudice force diverse users to withdraw from the public sphere.

Twitter’s design and administration all reinforce the ‘if you can’t take the heat, get out of the kitchen’ machismo of Silicon Valley culture. Social media platforms were designed within a male dominated industry and replicate the assumptions and attitudes typical of men in the industry. Twitter provides users with few options to protect themselves from abuse and there are no effective bystander mechanisms to enable users to protect each other.

Over the years, the now banned Milo Yiannopoulos and now imprisoned ‘revenge porn king’ Hunter Moore have accumulated hundreds of thousands of admiring Twitter followers by orchestrating abuse and hate campaigns. The number of followers, likes and retweets can act like a scoreboard in the ‘game’ of abuse.

Suggesting Twitter should be a land of free speech where users should battle one another within a ‘marketplace of ideas’ might make sense to the white, male, heterosexual tech bro, but it ignores the way sexism, racism and other forms of prejudice force diverse users to withdraw from the public sphere.

Dealing with online abuse

Over the last few years, Twitter has acknowledged its problem with harassment and sought to implement a range of strategies. As Twitter CEO Dick Costolo stated to employees in a leaked internal memo, ‘We suck at dealing with abuse and trolls on the platform and we’ve sucked at it for years’. However, steps have been incremental at best and are yet to make any noticeable difference to users.

How do we challenge the most toxic aspects of internet culture when its norms and values are built into online platforms themselves?

Researchers and academics are calling for the enforcement of existing laws and the enactment of new laws in order to deter online abuse and sanction offenders. ‘Respectful relationships’ education programs are incorporating messages on online abuse in the hope of reducing and preventing it.

These necessary steps to combat sexism, racism and other forms of prejudice in offline society might struggle to reduce online abuse though. The internet is host to specific cultures and sub-cultured in which harassment is normal or even encouraged.

Libertarian machismo was entrenched online by the 1990s when the internet was dominated by young, white, tech-savvy men – some of whom disseminated an often deliberately vulgar and sexist communicative style that discouraged female participation. While social media has bought an influx of women and other users online it has not displaced these older, male-dominated subcultures.

The fact that harassment is so easy on social media is no coincidence. The various dot-com start-ups that produced social media have emerged out of computing cultures that have normalised online abuse for a long time. Indeed, it seems incitements to abuse have been technologically encoded into some platforms.

Designing a more equitable internet

So how do we challenge the most toxic aspects of internet culture when its norms and values are built into online platforms themselves? How can a fairer and more prosocial ethos be built into online infrastructure?

Changing the norms and values common online will require a cultural shift in computing industries and companies.

Earlier this year, software developer and commentator Randi Lee Harper drew up an influential list of design suggestions to ‘put out the Twitter trashfire’ and reduce the prevalence of abuse on the platform. Her list emphasises the need to give users greater control over their content and Twitter experience.

One solution might appear in the form of social media app Yik Yak – basically a local, anonymous version of Twitter but with a number of important built-in safety features. When users post content to Yik Yak, other users can ‘upvote’ or ‘downvote’ the content depending on how they feel about it. Comments that receive more than five ‘down’ votes are automatically deleted, enabling a swift bystander response to abusive content. Yik Yak also employs automatic filters and algorithms as a barrier against the posting of full names and other potentially inappropriate content.

Yik Yak’s platform design is underpinned by a social understanding of online communication. It recognises the potential for harm and attempts to foster healthy bystander practices and cultures. This is a far cry from the unfettered pursuit of individual free speech at all costs, which has allowed abuse and harassment to go unaddressed in the past.

It seems like it will require more than a behavioural shift from users. Changing the norms and values common online will require a cultural shift in computing industries and companies so the development of technology is underpinned by a more diverse and inclusive understanding of communication and users.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing

Maggie Beer: Good food can drive better aged care

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Ask me tell me: Why women think it’s ok to lie about contraception

LISTEN

Health + Wellbeing, Business + Leadership, Society + Culture

Life and Shares

Explainer

Relationships, Science + Technology

Ethics Explainer: Post-Humanism

BY Michael Salter

Scientia Fellow and Associate Professor of Criminology UNSW. Board of Directors ISSTD. Specialises in complex trauma & organisedabuse.com

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

LGBT...Z? The limits of ‘inclusiveness’ in the alphabet rainbow

LGBT…Z? The limits of ‘inclusiveness’ in the alphabet rainbow

Opinion + AnalysisHealth + WellbeingRelationships

BY Jesse Bering The Ethics Centre 5 SEP 2016

A few years ago on Twitter, I found myself mindlessly clicking on a breadcrumb trail of ‘likes’ linked to a random post. It was under these banal circumstances that I came across a user profile with a brief but purposeful bio, one featuring the mysterious acronym ‘LGBTZ’.

The first four letters were obvious enough to me. LGBT, that bite-sized abbreviation for Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, has become a nearly ubiquitous rallying call for members of these historically marginalised groups and their allies. Even Donald Trump spoke this family friendly shorthand in his convention speech (although his oddly staggered enunciation sounded like he was a nervous pre-schooler tip-toeing through an especially tricky part of the alphabet). Trump also tacked on a “Q” for all those ill-defined “Queers” in the Republican audience. (A far less common iteration of this initialism includes an “I” for “Intersex” and an “A” for “Asexual.”)

But Z? The Twitter user’s profile image was a horse, and other language alluding to the fact he (or she) was an animal lover – and not of the platonic kind – brought that curious Z into sharp, squirm-worthy focus: “Zoophile”.

Perhaps we should take a hard look in the mirror and ask whether excluding Zs and Ps and others from the current tolerance roster isn’t doing to them precisely what was once done to us.

If you’re not familiar with the term, a zoophile is a person who is primarily sexually attracted to animals. The primarily part of that sentence is key. These aren’t just lascivious farmhands shagging goats because they can’t find willing human partners. That’s just plain bestiality.

Rather, these are people who genuinely prefer animals over members of their own species. If you hook a male zoophile’s genitals up to a plethysmograph (an extremely sensitive measure of sexual arousal), these men display stronger erectile responses to, say, images of stallions or Golden Retrievers than they do to naked human models.

I’d written about scientific research into zoophilia, along with other unusual sexualities, in my book Perv, so it wasn’t shocking to learn zoophiles have a social media presence. What’s surprising is this maligned demographic is apparently becoming emboldened enough to pull its Z up to the acronym table.

Paedophiles have started inching their much-loathed “P” in this direction as well, albeit in veiled form with the contemporary label “MAP” (“Minor-Attracted Person”). This is especially true for the so-called virtuous paedophiles, who are seriously committed to refraining from acting on their sexual desires because they realise the harm they’d cause to children. Similarly, many zoophiles consider themselves gentle animal welfare advocates, denouncing “zoosadists” who sexually abuse animals.

In any event, it’s easy to shun the Zs and Ps and all the other unwanted sexual minorities clawing their way up the acceptance ladder, refusing them entry into our embattled LGBT territory, because we don’t want to be associated with “perverts”. We’ve overcome tremendous obstacles to be where we are today. As an American growing up during the homophobic Reagan era, never in a million years did I imagine I’d legally marry another man one day. Yet I did. At this stage, perhaps we should take a hard look in the mirror and ask whether excluding Zs and Ps and others from the current tolerance roster isn’t doing to them precisely what was once done to us.

I know what you’re thinking. There’s a huge difference, since in these sad cases we’re dealing with the most innocent, most vulnerable members of society, who also can’t give their consent. That’s very much true.

When you actually try to justify our elbowing the Zs and Ps and others of their ilk out from under the rainbow umbrella though, it’s not so straightforward. Any seemingly ironclad rationale for their exclusion is stuffed more with blind emotion than clear-sighted reason.

To begin with, one doesn’t have to be sexually active to be a member of a sexual community. After all, I identified as gay before I had gay sex, just as I imagine most heterosexual people identify as straight before losing their virginity. In principle, at least, the same would apply to morally celibate zoophiles and paedophiles, neither of which are criminals and child molesters. Desires and behaviours are two different things.

Secondly, there’s now strong evidence paraphilias (lust outside of the norm) emerge in early childhood or, in the case of paedophilia, may even be innate. One zoophile, a successful attorney, told researchers that while his friends in middle school were all trying to get their hands on their fathers’ Playboys, he was secretly coveting the latest issue of Equus magazine.

Whether Zs or Ps are “born that way” or become that way early in life, it’s certainly not a choice they’ve made. This isn’t difficult to grasp but it tends to elude popular wisdom. I don’t know about you but I couldn’t become aroused by a Clydesdale or a prepubescent child if my life depended on it. That doesn’t make me morally superior to those unlucky enough to have brains that through no fault of their own respond this way to animals and children.

It’s an uncomfortable conversation to have, but there’s no science or logic to why “LGBT” contains the particular letters it does.

Not so long ago, remember, the majority of society saw gay men like me as immoral – even evil. Not for anything they’d done but for the simple fact that, neurologically, they fancied other men rather than women. The courts would have declared me mentally ill, not happily married. Just like conversion therapy has failed miserably to turn gay people straight, paraphilias are also immutable. Every clinical attempt to turn paedophiles into “teleiophiles” (attracted to reproductive-aged adults) has been a major flop.

Who knows what tortuous inner lives all those closeted Zs and Ps – and other unmentionables bearing today’s cross of scorn – experience, despite being celibate. Clinical psychologists report many of their clients are suicidal because of unwanted sexual desires – and this includes teenagers with a dawning awareness they are attracted to younger people.

I think it’s patently hypocritical for the LGBT community – which has worked so hard to overcome negative stereotypes, ostracism, and unjust laws – to shut out these people, fearing they would tarnish us more acceptable deviants. We’re only paying lip service to the concept of inclusiveness when we so publicly distance ourselves from those who need this communal protection the most.

In fact, LGB people arguably share more in common with the Zs and Ps than they do the Ts, since being transgender isn’t about who (or what) you’re sexually attracted to, but the gender you identify with. Unlike those representing the other letters in this character soup, trans people say their sexuality plays no role at all. Why then are Ts included while other, more unspeakable, sexual minorities aren’t?

Here’s my point then. It’s an uncomfortable conversation to have but there’s no science or logic to why “LGBT” contains the particular letters it does. Instead, it’s an evolving social code. So, is the filter that shapes this code just another moralistic lens that casts some human beings as inherently inferior and worthier of shame than others? And if this is so, who gets to control this filter and why?

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing

The road back to the rust belt

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Peter Singer on charitable giving

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

The niceness trap: Why you mustn’t be too nice

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Appreciation or appropriation? The impacts of stealing culture

BY Jesse Bering

Jesse Bering is a research psychologist and Director of the Centre for Science Communication at the University of Otago in Dunedin, New Zealand. An award-winning science writer specializing in human behaviour, his first book, The Belief Instinct (2011), was included on the American Library Association’s Top 25 Books of the Year.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Ethics Explainer: Eudaimonia

The closest English word for the Ancient Greek term eudaimonia is probably “flourishing”.

The philosopher Aristotle used it as a broad concept to describe the highest good humans could strive toward – or a life ‘well lived’.

Though scholars translated eudaimonia as ‘happiness’ for many years, there are clear differences. For Aristotle, eudaimonia was achieved through living virtuously – or what you might describe as being good. This doesn’t guarantee ‘happiness’ in the modern sense of the word. In fact, it might mean doing something that makes us unhappy, like telling an upsetting truth to a friend.

Virtue is moral excellence. In practice, it is to allow something to act in harmony with its purpose. As an example, let’s take a virtuous carpenter. In their trade, virtue would be excellences in artistic eye, steady hand, patience, creativity, and so on.

The eudaimon [yu-day-mon] carpenter is one who possesses and practices the virtues of his trade.

By extension, the eudaimon life is one dedicated to developing the excellences of being human. For Aristotle, this meant practicing virtues like courage, wisdom, good humour, moderation, kindness, and more.

Today, when we think about a flourishing person, virtue doesn’t always spring to mind. Instead, we think about someone who is relatively successful, healthy, and with access to a range of the good things in life. We tend to think flourishing equals good qualities plus good fortune.

This isn’t far from what Aristotle himself thought. Although he did believe the virtuous life was the eudaimon life, he argued our ability to practice the virtues was dependent on other things falling in our favour.

For instance, Aristotle thought philosophical contemplation was an intellectual virtue – but to have the time necessary for contemplation you would need to be wealthy. Wealth (as we all know) is not always a product of virtue.

Some of Aristotle’s conclusions seem distasteful by today’s standards. He believed ugliness was a hindrance to developing practical social virtues like friendship (because nobody would be friends with an ugly person).

However, there is something intuitive in the observation that the same person, transformed into the embodiment of social standards of beauty, would – everything else being equal – have more opportunities available to them.

In recognising our ability to practice virtue might be somewhat outside our control, Aristotle acknowledges our flourishing is vulnerable to misfortune. The things that happen to us can not only hurt us temporarily, but they can put us in a condition where our flourishing – the highest possible good we can achieve – is irrevocably damaged.

For ethics, this is important for three reasons.

First, because when we’re thinking about the consequences of an action we should take into account their impact on the flourishing of others. Second, it suggests we should do our best to eliminate as many barriers to flourishing as we possibly can. And thirdly, it reminds us that living virtuously needs to be its own reward. It is no guarantee of success, happiness or flourishing – but it is still a central part of what gives our lives meaning.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

The wonders, woes, and wipeouts of weddings

Big thinker

Relationships, Society + Culture

9 LGBTQIA+ big thinkers you should know about

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Anthem outrage reveals Australia’s spiritual shortcomings

Big thinker

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

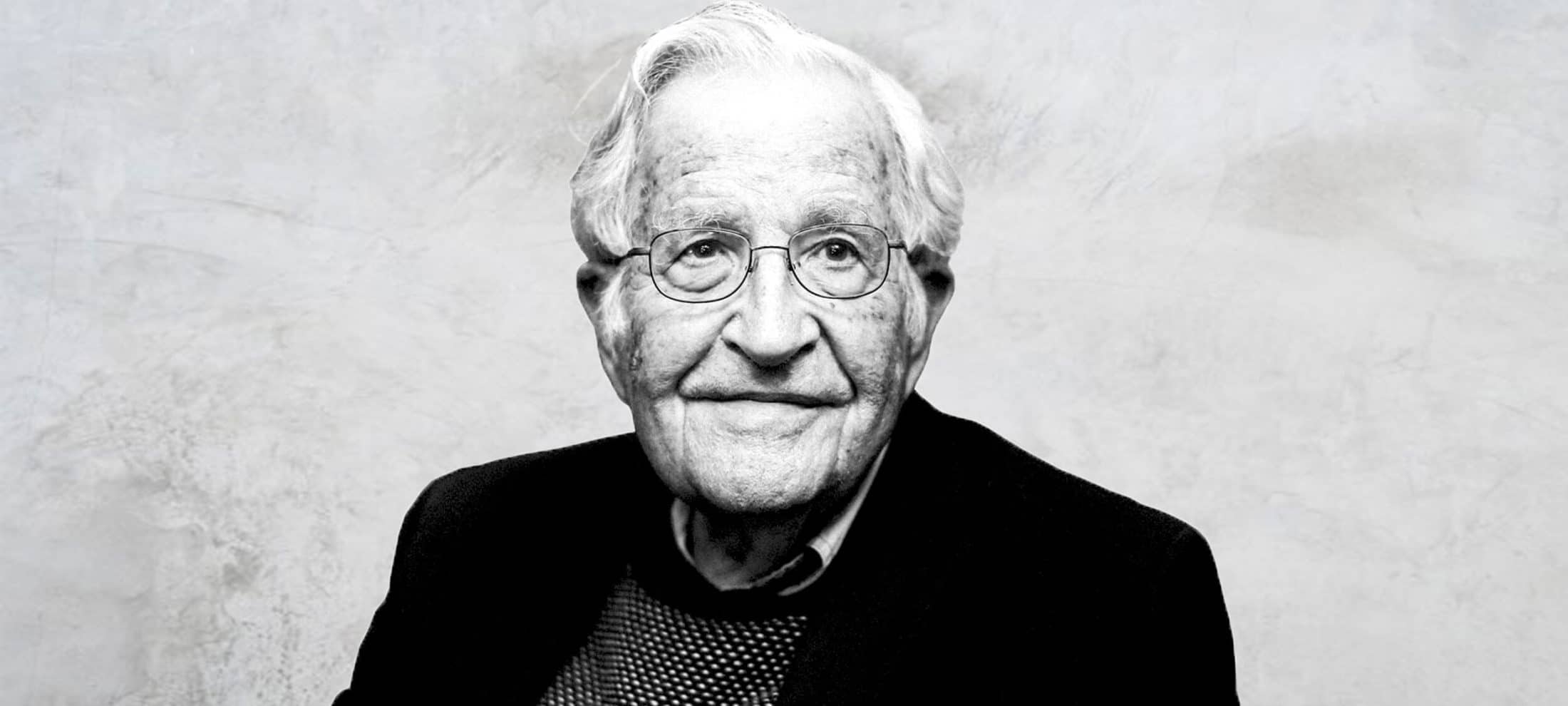

Big Thinker: Noam Chomsky

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Don’t throw the birth plan out with the birth water!

Don’t throw the birth plan out with the birth water!

Opinion + AnalysisHealth + WellbeingPolitics + Human Rights

BY Hannah Dahlen The Ethics Centre 2 AUG 2016

Just try mentioning ‘birth plans’ at a party and see what happens. Hannah Dahlen – a midwife’s perspective

Mia Freedman once wrote about a woman who asked what her plan was for her placenta. Freedman felt birth plans were “most useful when you set them on fire and use them to toast marshmallows”. She labelled people who make these plans as “birthzillas” more interested in birth than having a baby.

In response, Tara Moss argued:

The majority of Australian women choose to birth in hospital and all hospitals do not have the same protocols. It is easy to imagine they would, but they don’t, not from state to state and not even from hospital to hospital in the same city. Even individual health practitioners in the same facility sometimes do not follow the same protocols.

The debate

Why the controversy over a woman and her partner writing down what they would like to have done or not done during their birth? The debate seems not to be about the birth plan itself, but the issue of women taking control and ownership of their births and what happens to their bodies.

Some oppose birth plans on the basis that all experts should be trusted to have the best interests of both mother and baby in mind at all times. Others trust the mother as the person most concerned for her baby and believe women have the right to determine what happens to their bodies during this intimate, individual, and significant life event.

As a midwife of some 26 years, I wish we didn’t need birth plans. I wish our maternity system provided women with continuity of care so by the time a woman gave birth her care provider would fully know and support her well-informed wishes. Unfortunately, most women do not have access to continuity of care. They deal with shift changes, colliding philosophical frameworks, busy maternity units, and varying levels of skill and commitment from staff.

There are so many examples of interventions that are routine in maternity care but lack evidence they are necessary or are outright harmful. These include immediate clamping and cutting of the umbilical cord at birth, episiotomy, continuous electronic foetal monitoring, labouring or giving birth laying down and unnecessary caesareans. Other deeply personal choices such as the use of immersion in water for labour and birth or having a natural birth of the placenta are often not presented as options, or are refused when requested.

The birth plan is a chance to raise and discuss your wishes with your healthcare provider. It provides insight into areas of further conversation before labour begins.

I once had a woman make three birth plans when she found out her baby was in a breech presentation at 36 weeks. One for a vaginal breech birth, one for a cesarean, and one for a normal birth if the baby turned. The baby turned and the first two plans were ditched. But she had been through each scenario and carved out what was important for her.

Bashi Hazard – a legal perspective

Birth plans were introduced in the 1980s by childbirth educators to help women shape their preferences in labour and to communicate with their care providers. Women say preparing birth plans increases their knowledge and ability to make informed choices, empowers them, and promotes their sense of safety during childbirth. Some (including in Australia) report that their carefully laid plans are dismissed, overlooked, or ignored.

There appears to be some confusion about the legal status or standing of birth plans. Neither is reflective of international human rights principles or domestic law. The right to informed consent is a fundamental principle of medical ethics and human rights law and is particularly relevant to the provision of medical treatment. In addition, our common law starts from the premise that every human body is inviolate and cannot be subject to medical treatment without autonomous, informed consent.

Pregnant women are no exception to this human rights principle nor to the common law.

If you start from this legal and human rights premise, the authoritative status of a birth plan is very clear. It is the closest expression of informed consent that a woman can offer her caregiver prior to commencing labour. This is not to say she cannot change her mind but it is the premise from which treatment during labour or birth should begin.

Once you accept that a woman has the right to stipulate the terms of her treatment, the focus turns to any hostility and pushback from care providers to the preferences a woman has the right to assert in relation to her care.

Mothers report their birth plans are criticised or outright rejected on the basis that birth is “unpredictable”. There is no logic in this.

Care providers who understand the significance of the human and legal right to informed consent begin discussing a woman’s options in labour and birth with her as early as the first antenatal visit. These discussions are used to advise, inform, and obtain an understanding of the woman’s preferences in the event of various contingencies. They build the trust needed to allow the care provider to safely and respectfully support the woman through pregnancy and childbirth. Such discussions are the cornerstone of woman-centred maternity healthcare.

Human Rights in Childbirth

Reports received by Human Rights in Childbirth indicate that care provider pushback and hostility towards birth plans occurs most in facilities with fragmented care or where policies are elevated over women’s individual needs. Mothers report their birth plans are criticised or outright rejected on the basis that birth is “unpredictable”. There is no logic in this. If anything, greater planning would facilitate smoother outcomes in the event of unanticipated eventualities.

In truth, it is not the case that these care providers don’t have a birth plan. There is a birth plan – one driven purely by care providers and hospital protocols without discussion with the woman. This offends the legal and human rights of the woman concerned and has been identified as a systemic form of abuse and disrespect in childbirth, and as a subset of violence against women.

It is essential that women discuss and develop a birth plan with their care providers from the very first appointment. This is a precious opportunity to ascertain your care provider’s commitment to recognising and supporting your individual and diverse needs.

Gauge your care provider’s attitude to your questions as well as their responses. Expect to repeat those discussions until you are confident that your preferences will be supported. Be wary of care providers who are dismissive, vague or non-responsive. Most importantly, switch care providers if you have any concerns. The law is on your side. Use it.

Making a birth plan – some practical tips

- Talk it through with your lead care provider. They can discuss your plans and make sure you understand the implications of your choices.

- Make sure your support network know your plan so they can communicate your wishes.

- Attending antenatal classes will help you feel more informed. You’ll discover what is available and the evidence is behind your different options.

- Talk to other women about what has worked well for them, but remember your needs might be different.

- Remember you can change your mind at any point in the labour and birth. What you say is final, regardless of what the plan says.

- Try not to be adversarial in your language – you want people working with you, not against you. End the plan with something like “Thank you so much for helping make our birth special”.

- Stick to the important stuff.

Some tips on the specific content of your birth plan are available here.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Business + Leadership

Repairing moral injury: The role of EdEthics in supporting moral integrity in teaching

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

What ethics should athletes live by?

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing

Defining mental illness – what is normal anyway?

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing

Ethics from the couch: 5 shows to binge on

BY Hannah Dahlen

Hannah Dahlen is a professor of Midwifery at Western Sydney University and a practising midwife.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Does ethical porn exist?

Does ethical porn exist?

Opinion + AnalysisHealth + WellbeingSociety + Culture

BY Emma Wood The Ethics Centre 18 MAY 2016

It’s hard to separate violence and sex in lots of today’s internet pornography. Easily accessible content includes simulated rape, women being slapped, punched, and subject to slews of misogynistic insults.

It’s also harder than ever to deny that pornography use, given its addictive, misogynistic, and violent nature, has a range of negative impacts on consumers. First exposure to internet porn in Western countries takes place before puberty for a significant fraction of children today. A disturbingly high proportion of teenage boys and young men today believe rape myths as a result of porn exposure. There is also evidence suggesting exposure to violent, X-rated material leads to a dramatic increase in the perpetration of sexual violence.

Before we can answer questions about the ethics of porn we need to address fundamental questions about the ethics of sex.

It is also difficult to deny that the practices of the porn industry are exploitative to performers themselves. Stories such as the Netflix documentary Hot Girls Wanted depict cases of female performers agreeing to shoot a scene involving a particular act, only to be coerced on the spot by the producers into a more hard-core scene not previously agreed to. Anecdotes suggest this isn’t uncommon.

While these facts about disturbing content and exploitative practices lead some people to believe consumption of internet porn is unethical or anti-feminist, it prompts others to ask whether there could be such a thing as ethical porn. Are the only objections to pornography circumstantial – based in violent content, exploitation or particular types of pornography? Or is there some deeper fact about porn – any porn – that renders it ethically objectionable?

Suppose the kind of porn commonly found online:

- Depicted realistic, consensual, non-misogynistic, and safe sex – condoms and all.

- Was free of exploitation (a pipe-dream, but let’s imagine).

- Performers fully and properly consented to everything filmed.

- Regulation ensured only people who were educated and had other employment options were allowed to perform.

- Performers did not have a history of sexual abuse or underage porn exposure

- Pristine sexual health was a prerequisite for becoming a porn performer.

- The porn industry cut any ties they are alleged to have with sex trafficking and similarly exploitative activity.

If all this came true, would any plausible ethical objections to the production and consumption of pornography remain?

Before we can answer questions about the ethics of porn, we need to address fundamental questions about the ethics of sex.

One question is this: is sex simply another bodily pleasure, like getting a massage, or do sex acts have deeper significance? Philosopher Anne Barnhill describes sexual intercourse as a type of body language. She thinks that when you have sex with a person, you are not just going through physically pleasurable motions, you are expressing something to another person.

If you have sex with someone you care for deeply, this loving attitude is expressed through the body language of sex. But using the expressive act of sex for mere pleasure with a person you care little about can express a range of callous or hurtful attitudes. It can send the message that the other person is simply an object to be used.

Even if not, the messages can be confusing. The body language of tender kissing, close bodily contact and caresses say one thing to a sexual partner, while the fact that one has few emotional strings attached to them – especially if this is stated beforehand – says another.

We know that such mixed messages are often painful. The human brain is flooded with oxytocin – the same bonding chemical responsible for attaching mothers to their children – when humans have sex. There is a biological basis to the claim that ‘casual sex’ is a contradiction in terms. Sex bonds people to each other, whether we want this to happen or not. It is a profound and relationally significant act.

Porn consumption can become a refuge that prevents people otherwise capable of the daunting but character-building work of seeking a meaningful sexual relationship with a real person.

Let’s bring these ideas about the specialness of sex back to the discussion about porn. If the above ideas about sex are correct, then there is cause for doubt over the idea that it is the sort of thing that people in a casual or even non-existent relationship should be paid for. So long as there are ethical problems with casual sex itself, there will be ethical problems with consuming filmed casual sex.

So what should we say about porn made by adults in a loving relationship, as much ‘amateur’ (unpaid) pornography is? Suppose we have a film made by a happily married couple who love each other deeply and simply want to film and show realistic, affectionate, loving sex. Could consumption of such material pass as ethical?

Maybe it could, but many doubts remain. Porn consumption can become a refuge that prevents people otherwise capable of the daunting but character-building work of seeking a meaningful sexual relationship with a real person from doing so. Porn (even of the relatively wholesome kind described above) carries no risk of rejection, requires no relational effort and doesn’t demand consideration of another person’s sexual wishes or preferences.

Because it promises high reward for little effort, porn has the potential to prolong adolescence – that phase of life dominated by lone sexual fantasies – and be a disincentive to grow into the complicated, sexual relationship building of adulthood.

Based on this line of thinking, there may still be something unvirtuous about the consumption of porn, even that was produced ethically. Perhaps the only truly ethical, sexually explicit film would be of people in a loving relationship, which is seen only by them.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

A parade of vices: Which Succession horror story are you?

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Society + Culture

A new guide for SME’s to connect with purpose

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

I’m really annoyed right now: ‘Beef’ and the uses of anger

Opinion + Analysis

Climate + Environment, Health + Wellbeing

Donation? More like dump nation

BY Emma Wood

Dr Emma Wood is a research associate at the Institute for Ethics & Society at the University of Notre Dame Australia. Her research interests include metaethics, applied ethics and philosophy of religion.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Anzac Day: militarism and masculinity don’t mix well in modern Australia

Anzac Day: militarism and masculinity don’t mix well in modern Australia

Opinion + AnalysisHealth + WellbeingRelationships

BY Michael Salter The Ethics Centre 21 APR 2016

In 2016, the then Prime Minister Tony Abbott penned a passionate column on the relevance of Anzac Day to modern Australia. For Abbott, the Anzacs serve as the moral role models that Australians should seek to emulate. He wrote, “We hope that in striving to emulate their values, we might rise to the challenges of our time as they did to theirs”.

The notion that Anzacs embody a quintessentially Australian spirit is a century old. The official World War I journalist C.E.W. Bean wrote Gallipoli was the crucible in which the rugged resilience and camaraderie of (white) Australian masculinity, forged in the bush, was decisively tested and proven on the world stage.

At the time, this was a potent way of making sense out of the staggering loss of 8000 Australian lives in a single military campaign. Since then, it has been common for politicians and journalists to claim that Australia was ‘baptised’ in the ‘blood and fire’ of Gallipoli.

The dark side to the Anzac myth is a view of violence as powerful and creative.

However, public interest in Anzac Day has fluctuated over the course of the 20th century. Ambivalence over Australia’s role in the Vietnam War had a major role in dampening enthusiasm from the 1970s.

The election of John Howard in 1996 signalled a new era for the Anzac myth. The ‘digger’ was, for Prime Minister Howard, the embodiment of Australian mateship, loyalty and toughness. Since then, government funding has flowed to Anzac-related school curricula as well as related books, films and research projects. Old war memorials have been refurbished and new ones built. Attendance at Anzac events in Australia and overseas has swelled.

On Anzac Day, we are reminded how crucial it is for individuals to be willing to forgo self-interest in exchange for the common national good. Theoretically, Anzac Day teaches us not to be selfish and reminds us of our duties to others. But it does so at a cost. Because military role models bring with them militarism – which sees the horror and tragedy of war as a not only justifiable but desirable way to solve problems.

The dark side to the Anzac myth is a view of violence as powerful and creative. Violence is glorified as the forge of masculinity, nationhood and history. In this process, the acceptance and normalisation of violence culminates in celebration.

The renewed focus on the Anzac legend in Australian consciousness has brought with it a pronounced militarisation of Australian history, in which our collective past is reframed around idealised incidents of conflict and sacrifice. This effectively takes the politics out of war, justifying ongoing military deployment in conflict overseas, and stultifying debate about the violence of invasion and colonisation at home.

In the drama of militarism, the white, male and presumptively heterosexual soldier is the hero. The Anzac myth makes him the archetypical Australian, consigning the alternative histories of women, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders, and sexual and ethnic minorities to the margins. I’d argue that for right-wing nationalist groups, the Anzacs have come to represent their nostalgia for a racially purer past. They have aggressively protested against attempts to critically analyse Anzac history.

Turning away from militarism does not mean devaluing the military or forgetting about Australia’s military history.

Militarism took on a new visibility during Abbott’s time as Prime Minister. Current and former military personnel have been appointed to major civilian policy and governance roles. Police, immigration, customs, and border security staff have adopted military-style uniforms and arms. The number of former military personnel entering state and federal politics has risen significantly in the last 15 years.

The notion that war and conflict is the ultimate test of Australian masculinity and nationhood has become the dominant understanding not only of Anzac day but, arguably, of Australian identity. Any wonder that a study compiled by McCrindle Research reveals that 34% of males, and 42% of Gen Y males, would enlist in a war that mirrored that of WWI if it occurred today.

This exaltation of violence sits uncomfortably alongside efforts to reduce and ultimately eradicate the use of violence in civil and intimate life. Across the country we are grappling with epidemic of violence against women and between men. But when war is positioned as the fulcrum of Australian history, when our leaders privilege force in policy making, and when military service is seen as the penultimate form of public service, is it any wonder that boys and men turn to violence to solve problems and create a sense of identity?

The glorification of violence in our past is at odds with our aspirations for a violence-free future.

In his writings on the dangers of militarism, psychologist and philosopher William James called for a “moral equivalent of war” – a form of moral education less predisposed to militarism and its shortcomings.

Turning away from militarism does not mean devaluing the military or forgetting about Australia’s military history. It means turning away from conflict as the dominant lens through which we understand our heritage and shared community. It means abjuring force as a means of solving problems and seeking respect. However, it also requires us to articulate an alternative ethos weighty enough to act as a substitute for militarism.

At a recent domestic violence conference in Sydney, Professor Bob Pease called for the rejection of the “militarisation of masculinity”, arguing that men’s violence in war was linked to men’s violence against women. At the same time, however, he called on us to foster “a critical ethic of care in men”, recognising that men who value others and care for them are less prone to violence.

For as long as militarism and masculinity are fused in the Australian imagination, it’s hard to see how this ethos of care can take root. It seems that the glorification of violence in our past is at odds with our aspirations for a violence-free future. The question is whether we value this potential future more than an idealised past.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

LISTEN

Relationships, Society + Culture

Little Bad Thing

Opinion + Analysis

Climate + Environment, Health + Wellbeing

How should vegans live?

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Would you kill one to save five? How ethical dilemmas strengthen our moral muscle

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Calling out for justice

BY Michael Salter

Scientia Fellow and Associate Professor of Criminology UNSW. Board of Directors ISSTD. Specialises in complex trauma & organisedabuse.com

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Academia’s wicked problem

Academia’s wicked problem

Opinion + AnalysisHealth + WellbeingRelationships

BY Virginia Barbour The Ethics Centre 18 APR 2016

What do you do when a crucial knowledge system is under-resourced, highly valued, and is having its integrity undermined? That’s the question facing those working in academic research and publishing. There’s a risk Australians might lose trust in one of the central systems on which we rely for knowledge and innovation.

It’s one of those problems that defies easy solutions, like obesity, terrorism or a tax system to suit an entire population. Academics call these “wicked problems” – meaning they’re resistant to easy solutions, not that they are ‘evil’.

Charles West Churchman, who first coined the term, described them as:

That class of social system problems which are ill-formulated, where the information is confusing, where there are many clients and decision makers with conflicting values and where the ramifications in the whole system are thoroughly confusing.

The wicked problem I face day-to-day is that of research and publication ethics. Though most academics do their best within a highly pressured system I see many issues, which span a continuum, starting with cutting corners in the preparation of manuscripts and ending with outright fraud.

It’s helpful to know whether the problem we are facing is a wicked one or not. It can help us to rethink the problem, understand why conventional problem-solving approaches have failed and encourage novel approaches, even if solutions are not readily available.

Though publication ethics, which considers academic work submitted for publication, has traditionally been considered a problem solely for academic journal editors and publishers, it is necessarily entwined with research ethics – issues related to the actual performance of the academic work. For example, unethical human experimentation may only come to light at the time of publication though it clearly originates much earlier.

Given the pressure editors are under, the system is vulnerable to subversion.

Consider the ethical issues surrounding peer review, the process by which academic experts (peers) assess the work of others.

Though imperfect, formalisation of peer review has become an important mark of quality for a journal. Peer review by experts, mediated by journal editors, usually determines whether a paper is published. Though seemingly simple, there are many points where the system can be gamed or even completely subverted – a major one being in the selection of reviewers.

As the number of academics and submissions to journals increase, editors face a logistical challenge in keeping track of an ever-increasing number of submissions needing review. However, as the rise in submissions has not corresponded with a rise in editors – many of whom are volunteers – these journals are overworked and often don’t have a big enough circle of reviewers to call on for the papers being submitted.

A simple approach to increase the pool of reviewers adopted by a number of journals is to allow authors to suggest reviewers for their paper via the online peer review system. These suggestions can be valuable if overseen by editors who can assess reviewers’ credentials. But they are already overworked and often handling work at the edge of their area of expertise, meaning time is at a premium.

Given the pressure editors are under, the system is vulnerable to subversion. It’s always been a temptation for authors to submit the name of reviewers who they believed would view their work favourably. Recently, a small number took it a step further, suggesting fake reviewer names for their papers.

These fake reviewers (usually organised via a third party) promptly submitted favourable reviews which led to papers inappropriately being accepted for publication. The consequences were severe – papers had to be retracted with consequent potential reputational damage to the journal, editors, authors and their institutions. Note how a ‘simple’ view of a ‘wicked’ problem – under resourced editors can be helped by authors suggesting their reviewers – led to new and worse problems than before.

Removing the ability of authors to suggest reviewers … would be treating a symptom rather than the cause.

But why would some authors go to such extreme ends as submitting fake reviews? The answer takes us into a related problem – the way authors are rewarded for publications.

Manipulating peer review gives authors a higher chance of publication – and academic publications are crucial for being promoted at universities. Promotion often provides higher salary, prestige, perhaps less teaching allocation and other fringe benefits. So for those at the extreme, who lack the necessary skills to publish (or even firm command of academic English), it’s logical to turn to those who understand how to manipulate the system.

We could easily fix the problem of fake reviews by removing an author’s ability to suggest reviewers but this would be treating a symptom rather than the cause. Namely, a perverse reward system for authors.

Removing author suggestions does nothing to help overworked editors deal more easily with the huge amount of submissions they receive. Nor do editors have the power to address the underlying problem – an inappropriate system of academic incentives.

There are no easy solutions but accepting the complexity may at least help to understand what it is that needs to be solved. Could we change the incentive structure to reward authors for more than merely being published in a journal?

There are moves to understand these intertwined problems but all solutions will fail unless we come back to the first requirement for approaching a wicked problem – agreement it’s a problem shared by many. So while the issues are most notable in academic journals, we won’t find all the solutions there.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

To live well, make peace with death

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Science + Technology

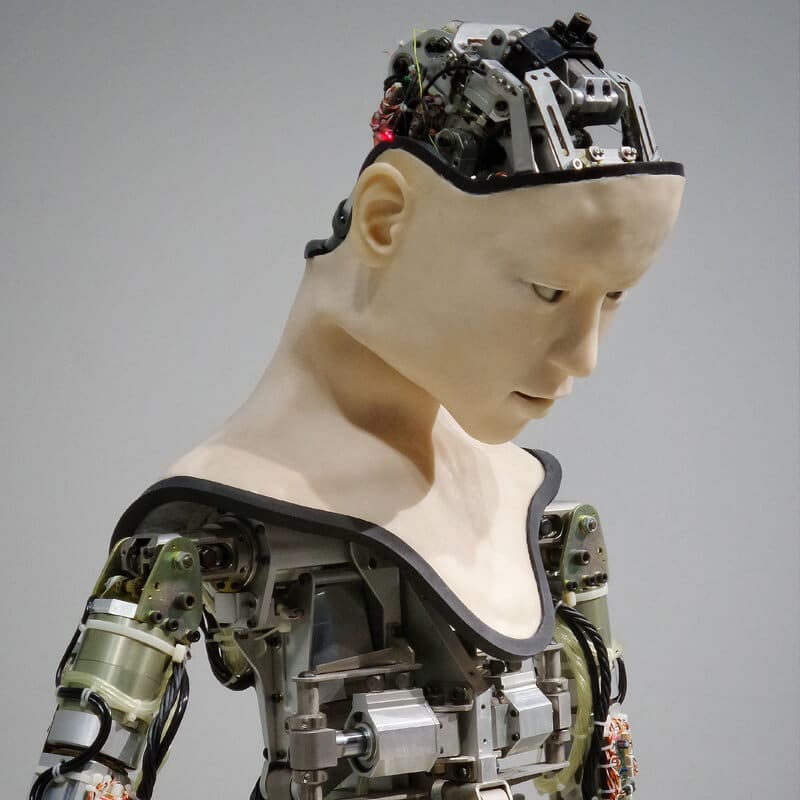

Making friends with machines

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Science + Technology

The ethics of drug injecting rooms

Big thinker

Relationships, Society + Culture