The ethics of tearing down monuments

The ethics of tearing down monuments

Opinion + AnalysisPolitics + Human RightsRelationshipsSociety + Culture

BY Simon Longstaff The Ethics Centre 12 JUN 2020

In the UK and US and other nations around the world, public monuments dedicated to people who have profited from or perpetuated slavery and racism are being torn down by demonstrators and public authorities who sympathise with the justice of their cause.

Statues of Christopher Columbus, Edward Colston, King Leopold II and Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee are amongst those toppled in protest.

What are we to make of these acts? In particular, who should decide the fate of such monuments – and according to what criteria?

By their very nature, statues are intended to honour those they depict. They elevate both the likeness and the reputation of their subject – conferring a kind of immortality denied to those of us who simply fade away in both form and memory.

So, the decision to raise a statue in a public place is a serious matter. The choice reveals much about the ethical sensibilities of those who commission the work. Such a work is a public declaration that a particular person, through their character and deeds, is deserving of public commemoration.

There are six criteria that should be used to evaluate the public standing of a particular life. These can be applied at the time of commissioning a monument or retrospectively when determining if such a commemoration is justified.

-

They must not be associated with any gateway acts

Are there aspects of the person’s conduct that are so heinous as to rule them out, irrespective of any other achievement that might merit celebration? For example, one would not honour a genocidal mass murderer, even if the rest of their life was marked by the most profoundly positive achievements. There are some deeds that are so wrong as to be beyond rectification.

-

Their achievements must be exceptionally noteworthy

Did they significantly exceed the achievements of others in relevantly similar circumstances? For example, we should note that most statues recognise the achievements of people who were born into conditions of relative privilege. The outstanding achievements of the marginalised and oppressed are, for the most part, barely noticed, let alone celebrated.

-

Their work must have served the public good

Did the person pursue ends that were noble and directed to the public good? For example, was the person driven by greed and a desire for personal enrichment – but just happened to increase the common good along the way?

-

The means by which they achieved their work must be ethical

Were the means employed by the person ethically acceptable? For example, did the person benefit some by denying the intrinsic dignity of others (through enslavement, etc)?

-

They must be the principal driver of the outcomes associated with their deeds

Is the person responsible for the good and evil that flowed from their deeds? Are they a principal driver of change? Or have others taken their ideas and work and used them for good or ill? It is important that we neither praise nor blame people for outcomes that they would never have intended but were the inadvertent product of their work. In those cases, we should not gloss over the truth of what happened. But if they otherwise deserve to be honoured for their achievements, then these should not be deemed ‘tainted’ by the deeds of others.

-

The monument must contribute positively to the public commons

Would the creation of the monument be a positive contribution to the public commons, or is it likely to become a site of unproductive strife and dissension? In considering this, does the statue perform a role beyond celebrating a particular person and their life? Is it emblematic of some deeper truth in history that should be acknowledged and debated? Not every public monument should be a source of joy and consensus. Some play a useful role if they prompt debate and even remorse.

It will be noted that five of the six criteria relate to the life of the individual who is commemorated. Only the sixth criterion looks beyond the person to the wider good of society. However, this is an important consideration given that we are thinking, here, specifically about statues displayed in public places.

The retrospective application of this criteria is precisely what is happening ‘on the streets’ at the moment. The trouble is that the popular response is often more visceral than considered – and this sparks deeper concerns amongst citizens who are ready to embrace change … but only if it is principled and orderly.

Of course, asking frustrated and angry people to be ‘principled and orderly’ in their response to oppression is unlikely to produce a positive response. That’s why I think it important for civic authorities to take responsibility for addressing such questions, and to do so proactively.

This was recently demonstrated by the Borough of Tower Hamlets that removed the statue of slave owner Robert Milligan from its plinth at West India Quay in London’s Docklands. As the Mayor of London, Sadiq Khan, noted: “it’s a sad truth that much of our wealth was derived from the slave trade – but this does not have to be celebrated in our public spaces”.

UPDATE: The statue of slave trader Robert Milligan has now been removed from West India Quay.

It’s a sad truth that much of our wealth was derived from the slave trade – but this does not have to be celebrated in our public spaces. #BlackLivesMatterpic.twitter.com/ca98capgnQ

— Sadiq Khan (@SadiqKhan) June 9, 2020

What does all of this mean for Australia? There will be considerable debate about what statues should be removed. I will leave it to others to apply the criteria outlined above. However, the issue is not just about the statues we take down.

What of those we fail to erect? Who have we failed to honour? For example, have we missed an opportunity to recognise people like Aboriginal warrior Pemulwuy whose resistance to European occupation was every bit as heroic as that of the British Queen Boudica. Two warrior-leaders – the latter celebrated; the other not. The absence is eloquent.

You can contact The Ethics Centre about any of the issues discussed in this article. We offer free counselling for individuals via Ethi-call; professional fee-for-service consulting, leadership and development services; and as a non-profit charity we rely heavily on donations to continue our work, which can be made via our website. Thank you.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

The wonders, woes, and wipeouts of weddings

Explainer

Politics + Human Rights

Ethics Explainer: Social Contract

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Philosophy must (and can) thrive outside universities

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

What we owe to our pets

BY Simon Longstaff

Simon Longstaff began his working life on Groote Eylandt in the Northern Territory of Australia. He is proud of his kinship ties to the Anindilyakwa people. After a period studying law in Sydney and teaching in Tasmania, he pursued postgraduate studies as a Member of Magdalene College, Cambridge. In 1991, Simon commenced his work as the first Executive Director of The Ethics Centre. In 2013, he was made an officer of the Order of Australia (AO) for “distinguished service to the community through the promotion of ethical standards in governance and business, to improving corporate responsibility, and to philosophy.” Simon is an Adjunct Professor of the Australian Graduate School of Management at UNSW, a Fellow of CPA Australia, the Royal Society of NSW and the Australian Risk Policy Institute.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Ask the ethicist: If Google paid more tax, would it have more media mates?

Ask the ethicist: If Google paid more tax, would it have more media mates?

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + LeadershipPolitics + Human Rights

BY Simon Longstaff The Ethics Centre 19 MAY 2020

If multinational tech platforms paid more tax on the revenues they made in Australia, would they be in a better moral position to resist government attempts to force them to pay a ‘license fee’ to news media?

This article was first published by Crikey, in their weekly Ask the Ethicist column featuring Dr Simon Longstaff.

There are a couple of ways to look at this question – one as a matter of principle, the other through the lens of prudence. In terms of principle, I think that we should treat separately the issues of tax and the proposed ‘licence fee’. This is because each issue rests on its own distinct ethical foundations.

In the case of tax, all citizens (including corporate citizens) have an obligation to contribute to the cost of funding the public goods provided by the state. For example, a company like Google shares in the benefits of a society that is healthy, well educated, peaceful and effectively governed under the rule of law. All who draw on and benefit from such public goods should contribute to the cost of their generation and maintenance.

Instinctively, most citizens believe that we should each pay our ‘fair share’ of tax. However, that belief is at odds with the fact that our formal obligation is not to pay a fair amount of tax but, instead, to pay only the amount of tax due to be paid as defined by law. Most of us don’t have much choice about how we discharge this formal obligation – as our taxes are automatically remitted to the Australian taxation Office (ATO) by our employers.

However, most corporations, including Google, have considerable latitude when calculating the tax they think due. For example, corporations have a clear choice about the extent to which they move right to the edge of what the law allows: ‘avoiding’ (which is legal) but not ‘evading’ (which is illegal) tax obligations that, to an ordinary person, might seem to be due.

It is this approach to ‘tax planning’ that allows Google to earn revenue, in Australia, of $4.3B yet only pay tax of $100M. Google has a perfectly rational argument about how this can the case – and relies on the fact that it should only pay tax that is legally due.

However, as is the case with other multinational corporations who make similar calculations, Google’s position fails the ‘pub test’ in that it seems to be unfair? Why? Because it seems inherently improbable (and improper) that such massive local revenue should flow offshore to benefit people who contribute nothing to maintain the society that has made possible such a financial windfall.

The issue of Google paying a ‘licence fee’ to the creators of news content is somewhat different. In general, you’d think it a reasonable expectation that a company pay for the inputs it draws on to make a profit. After all, businesses pay for labour inputs (wages), for financial inputs (interest and dividends), for material inputs (cash outlays), etc. So, why not pay for content that is derived from other sources?

Of course, what’s good for the ‘goose’ should be good for the ‘gander’. Companies like News Corporation and Nine should also be asked if they pay for all of the inputs that they draw on to make a profit? For example, do they pay for all published opinion pieces, or for the interviews they conduct, etc.? However, in general, it seems reasonable to expect that Google (and other companies) should pay for what they derive from others.

Of course, Google does not agree – and is especially opposed to Australian proposals because, if adopted, they will set a precedent that other countries are likely to follow. It is this consideration that leads us to look at the issue through the lens of prudence.

Governments (of all political hues) are especially attentive to the demands of the media. What NewsCorp and Co. want, they usually get … unless opposed by the one force that wields even greater influence over the judgement of politicians – the force of public opinion. So, if Google wishes to prevent or limit the levying of a ‘licence fee’, its most potent ally might have been the Australian public.

However, the electorate is unlikely to back the interests of a company that is perceived not to back the interests of the people whose taxes provide the infrastructure on which Google depends for the enrichment of its overseas owners.

This is where principle and prudence align. Google (and other multinational corporations) should pay taxes that amount to a fair contribution to the maintenance of public goods. Had it done so, then Google might have many more friends who might stand beside it in its battle with other powerful corporations like NewsCorp and Nine.

I am not sure if arguments from principle or prudence will really carry much weight. Perhaps the situation needs to be expressed in the language of financial self-interest. Compared to a licence fee (which might be as high as $1B per annum), would a less aggressive approach tax planning have have been a good investment?

You can contact The Ethics Centre about any of the issues discussed in this article. We offer free counselling for individuals via Ethi-call; professional fee-for-service consulting, leadership and development services; and as a non-profit charity we rely heavily on donations to continue our work, which can be made via our website. Thank you.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Society + Culture

Free speech is not enough to have a good conversation

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

How we should treat refugees

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Self-presentation with the collapse of the back and front stage

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Science + Technology

People first: How to make our digital services work for us rather than against us

BY Simon Longstaff

Simon Longstaff began his working life on Groote Eylandt in the Northern Territory of Australia. He is proud of his kinship ties to the Anindilyakwa people. After a period studying law in Sydney and teaching in Tasmania, he pursued postgraduate studies as a Member of Magdalene College, Cambridge. In 1991, Simon commenced his work as the first Executive Director of The Ethics Centre. In 2013, he was made an officer of the Order of Australia (AO) for “distinguished service to the community through the promotion of ethical standards in governance and business, to improving corporate responsibility, and to philosophy.” Simon is an Adjunct Professor of the Australian Graduate School of Management at UNSW, a Fellow of CPA Australia, the Royal Society of NSW and the Australian Risk Policy Institute.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Ask an ethicist: do teachers have the right to object to returning to school?

Ask an ethicist: do teachers have the right to object to returning to school?

Opinion + AnalysisPolitics + Human RightsRelationships

BY Simon Longstaff The Ethics Centre 4 MAY 2020

In recent weeks, there has been a particularly intense debate about whether or not students should return to the classroom.

This article was first published by Crikey, in their weekly Ask the Ethicist column featuring Dr Simon Longstaff.

Much of that debate has focused on the interests of the children and their families. However, there is a third stakeholder group – the nation’s teachers – who need to be considered. Part ‘essential worker’, part ‘political football’, they have been celebrated on one hand and condemned on the other. So, what are the ethical obligations of those who teach our children during COVID-19.

As a starting point, let’s agree that education is a significant ‘good’ and that children should not be deprived of its benefits unless there are compelling reasons for doing so. Compelling reasons would include the potential risk of infection due to school attendance.

At present, the balance of evidence is that the risk of children becoming infected is low and that they are unlikely to be transmitters of the disease to adults – especially in well-controlled environments. However, why take any risk – if viable alternatives are available?

Here, we should note that the education of children has not been suspended during the crisis. Instead, it has continued by other – ‘online’ – means. This has required a massive effort by the teaching profession to ‘recalibrate’ the learning environment to support distance learning.

We should also note that the ability to provide distance education distinguishes teachers from other essential workers who, of necessity, must provide a face-to-face service. For example, while some doctors can consult with patients using ‘telemedicine’, most health care workers need to be physically present (e.g. when administering a flu injection, or caring for a bed-ridden patient, etc.).

So, if distance learning achieves the same educational outcomes as classroom teaching, teachers would not seem to be under any moral obligation to return to the classroom. However, the Federal Government has recently cited reports suggesting that online learning produces ‘sub-optimal’ outcomes for students (unwelcome news for children living in remote communities and educated by the ‘school of the air’).

If this is true, then it would suggest two things. First that the government should be massively increasing its investment in education for children who have no option but to engage in distance education. Second, that teachers should be heading back into the classroom.

However, what of the teacher who lives with people for whom COVID-19 is a particular threat … the aged and infirm? In those cases, the choice is not just a matter of balancing a public duty as an educator against a preference for personal safety. Rather, the teacher is caught in an ethical dilemma of competing duties.

In such a case, I think it would be reasonable for a teacher to claim they have a conscientious objection to returning to the classroom – grounded in a refusal to be the potential cause of harm to a loved one – especially when the only certain protection for the loved one is that the teacher remain isolated.

You can contact The Ethics Centre about any of the issues discussed in this article. We offer free counselling for individuals via Ethi-call; professional fee-for-service consulting, leadership and development services; and as a non-profit charity we rely heavily on donations to continue our work, which can be made via our website. Thank you.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Praying for Paris doesn’t make you racist

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

If we’re going to build a better world, we need a better kind of ethics

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

What money and power makes you do: The craven morality of The White Lotus

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

Five dangerous ideas to ponder over the break

BY Simon Longstaff

Simon Longstaff began his working life on Groote Eylandt in the Northern Territory of Australia. He is proud of his kinship ties to the Anindilyakwa people. After a period studying law in Sydney and teaching in Tasmania, he pursued postgraduate studies as a Member of Magdalene College, Cambridge. In 1991, Simon commenced his work as the first Executive Director of The Ethics Centre. In 2013, he was made an officer of the Order of Australia (AO) for “distinguished service to the community through the promotion of ethical standards in governance and business, to improving corporate responsibility, and to philosophy.” Simon is an Adjunct Professor of the Australian Graduate School of Management at UNSW, a Fellow of CPA Australia, the Royal Society of NSW and the Australian Risk Policy Institute.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

The value of a human life

The value of a human life

Opinion + AnalysisHealth + WellbeingPolitics + Human RightsRelationshipsScience + Technology

BY Simon Longstaff The Ethics Centre 1 MAY 2020

One of the most enduring points of tension during the COVID-19 pandemic has concerned whether the national ‘lockdown’ has done more harm than good.

This issue was squarely on the agenda during a recent edition of ABC TV’s Q+A. The most significant point of contention arose out of comments made by UNSW economist, Associate Professor Gigi Foster. Much of the public response was critical of Dr. Foster’s position – in part because people mistakenly concluded she was arguing that ‘economics’ should trump ‘compassion’.

That is not what Gigi Foster was arguing. Instead, she was trying to draw attention to the fact that the ‘lockdown’ was at risk of causing as much harm to people (including being a threat to their lives) as was the disease, COVID-19, itself.

In making her case, Dr. Foster invoked the idea of Quality Adjusted Life Years (QALYs). As she pointed out, this concept has been employed by health economists for many decades – most often in trying to decide what is the most efficient and effective allocation of limited funds for healthcare. In essence, the perceived benefit of a QALY is that it allows options to be assessed on a comparable basis – as all human life is made measurable against a common scale.

In essence, the perceived benefit of a QALY is that it allows options to be assessed on a comparable basis – as all human life is made measurable against a common scale.

So, Gigi Foster was not lacking in compassion. Rather, I think she wanted to promote a debate based on the rational assessment of options based on calculation, rather than evaluation. In doing so, she drew attention to the costs (including significant mental health burdens) being borne by sections of the community who are less visible than the aged or infirm (those at highest risk of dying if infected by this coronavirus).

I would argue that there are two major problems with Gigi Foster’s argument. First, I think it is based on an understandable – but questionable – assumption that her way of thinking about such problems is either the only or the best approach. Second, I think that she has failed to spot a basic asymmetry in the two options she was wanting to weigh in the balance. I will outline both objections below.

In invoking the idea of QALYs, Foster’s argument begins with the proposition that, for the purpose of making policy decisions, human lives can be stripped of their individuality and instead, be defined in terms of standard units. In turn, this allows those units to be the objects of calculation. Although Gigi Foster did not explicitly say so, I am fairly certain that she starts from a position that ethical questions should be decided according to outcomes and that the best (most ethical) outcome is that which produces the greatest good (QALYs) for the greatest number.

Many people will agree with this approach – which is a limited example of the kind of Utilitarianism promoted by Bentham, the Mills, Peter Singer, etc. However, there will have been large sections of the Q+A audience who think this approach to be deeply unethical – on a number of levels. First, they would reject the idea that their aged or frail mother, father, etc. be treated as an expression of an undifferentiated unit of life. Second, they would have been unnerved by the idea that any human being should be reduced to a unit of calculation.

…they would have been unnerved by the idea that any human being should be reduced to a unit of calculation.

To do so, they might think, is to violate the ethical precept that every human being possesses an intrinsic dignity. Gigi Foster’s argument sits squarely in a tradition of thinking (calculative rationality) that stems from developments in philosophy in the late 16th and 17th Centuries. It is a form of thinking that is firmly attached to Enlightenment attempts to make sense of existence through the lens of reason – and which sought to end uncertainty through the understanding and control of all variables. It is this tendency that can be found echoing in terms like ‘human resources’.

Although few might express a concern about this in explicit terms, there is a growing rejection of the core idea – especially as its underlying logic is so closely linked to the development of machines (and other systems) that people fear will subordinate rather than serve humanity. This is an issue that Dr Matthew Beard and I have addressed in the broader arena of technological design in our publication, Ethical By Design: Principles for Good Technology.

The second problem with Dr. Foster’s position is that it failed to recognise a fundamental asymmetry between the risks, to life, posed by COVID-19 and the risks posed by the ‘lockdown’. In the case of the former: there is no cure, there is no vaccine, we do not even know if there is lasting immunity for those who survive infection.

We do not yet know why the disease kills more men than women, we do not know its rate of mutation – or its capacity to jump species, etc. In other words, there is only one way to preserve life and to prevent the health system from being overwhelmed by cases of infection leading to otherwise avoidable deaths – and that is to ‘lockdown’.

…there is only one way to preserve life and to prevent the health system from being overwhelmed by cases of infection leading to otherwise avoidable deaths – and that is to ‘lockdown’.

On the other hand, we have available to us a significant number of options for preventing or minimising the harms caused by the lockdown. For example, in advance of implementing the ‘lockdown’, governments could have anticipated the increased risks to mental health leading to a massive investment in its prevention and treatment.

Governments have the policy tools to ensure that there is intergenerational equity and that the burdens of the ‘lockdown’ do not fall disproportionately on the young while the benefits were enjoyed disproportionately by the elderly.

Governments could have ensured that every person in Australia received basic income support – if only in recognition of the fact that every person in Australia has had to play a role in bringing the disease under control. Is it just that all should bear the burden and only some receive relief – even when their needs are as great as others?

Whether or not governments will take up the options that address these issues is, of course, a different question. The point here is that the options are available – in a way that other options for controlling COVID-19 are not. That is the fundamental asymmetry mentioned above.

I think that Gigi Foster was correct to draw attention to the potential harm to life, etc. caused by the ‘lockdown’. However, she was mistaken not to explore the many options that could be taken up to prevent the harm she and many others foresee. Instead, she went straight to her argument about QALYs and allowed the impression to form that the old and the frail might be ‘sacrificed’ for the greater good.

You can contact The Ethics Centre about any of the issues discussed in this article. We offer free counselling for individuals via Ethi-call; professional fee-for-service consulting, leadership and development services; and as a non-profit charity we rely heavily on donations to continue our work, which can be made via our website. Thank you.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Politics + Human Rights

How to have a difficult conversation about war

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

5 Movies that creepily foretold today’s greatest ethical dilemmas

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights

A foot in the door: The ethics of internships

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Calling out for justice

BY Simon Longstaff

Simon Longstaff began his working life on Groote Eylandt in the Northern Territory of Australia. He is proud of his kinship ties to the Anindilyakwa people. After a period studying law in Sydney and teaching in Tasmania, he pursued postgraduate studies as a Member of Magdalene College, Cambridge. In 1991, Simon commenced his work as the first Executive Director of The Ethics Centre. In 2013, he was made an officer of the Order of Australia (AO) for “distinguished service to the community through the promotion of ethical standards in governance and business, to improving corporate responsibility, and to philosophy.” Simon is an Adjunct Professor of the Australian Graduate School of Management at UNSW, a Fellow of CPA Australia, the Royal Society of NSW and the Australian Risk Policy Institute.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

There’s more than lives at stake in managing this pandemic

There’s more than lives at stake in managing this pandemic

Opinion + AnalysisHealth + WellbeingPolitics + Human RightsRelationships

BY Matthew Beard The Ethics Centre 3 APR 2020

Imagine a parallel universe somewhere, one without a pandemic. What would you be spending this week concerned with? What social and political issues would you be wrestling with? How would you be spending your day?

Ironically, my parallel life looks very similar. Locked in a room, thinking a lot about pandemics. I’m not an epidemiologist or a public health expert though – in my parallel universe, I’m preparing to run a thought experiment for The Festival of Dangerous Ideas: The Ethics of the Apocalypse.

The basic premise is to find out whether, facing a couple of end-of-the-world scenarios, the audience can save the human race without losing their humanity in the process. I won’t give away how the event works or is scored, but there are a bunch of different victory conditions – survival is a necessary condition of success, but alone, it’s not sufficient.

That point bears repeating as we live through a pandemic of our very own: survival is a necessary, but insufficient condition for success.

By focusing solely on what is going to guarantee success or best facilitate a flattening of the curve and minimise deaths, we risk permitting a political and social environment that we would, in that parallel universe, reject outright.

Over the last few weeks, as Australia’s containment measures around COVID-19 have grown increasingly strict, there’s been a widespread movement demanding an immediate lockdown. #Lockusdown and other variations have trended on Twitter, and major mastheads have called for increasingly severe policing measures to manage the pandemic. Writing for The Guardian, Grattan Institute CEO John Daley wrote:

“There is no point trying to finesse which strategies work best; instead the imperative would be to implement as many as possible at once, including closing schools, universities, colleges, public transport and non-essential retail, and confining people to their homes as much as possible.

Police should visibly enforce the lockdown, and all confirmed cases should be housed in government-controlled facilities. This might seem unimaginable, but it is exactly what has already happened in China, South Korea and Italy.”

Similar comments have been made by other public commentators in support of such measures, including the ABC’s Norman Swan. Swan has pointed to the efficiency with which China were able to control the spread through draconian measures – including in one case, welding people inside their apartment building.

Imagine in a pre-COVID world, suggesting a liberal democracy like Australia look to the authoritarian state of China for political guidance. Yet, this is what happens when we reduce all things to a single metric: the goal of keeping people at home and flattening the curve of new infections. It is easy to conceptualise. We can visualise what it involves and we can imagine the benefits it confers.

However, whilst this logic is comforting – especially in times when fear and uncertainty are rife – it places us dangerously close to the crude and morally repugnant catch cry: the ends justify the means.

In NSW, new laws and extreme penalties aim to enforce self-isolation regimes – as John Daley’s piece suggested. The maximum penalties for leaving your home without a reasonable excuse (of which sixteen are listed) are six months imprisonment or a fine of up to $11,000.

Are you cooped up in your share house, finding it impossible to work? If you choose to go to the park, you’ll face a severe penalty. Considering using the time your teenager has off school to rack up some learner driving hours by leaving the city and heading to the mountains for a bushwalk? Want to do a drive-by birthday celebration in lieu of an actual party? All of them are now subject to police enforcement. Do any of them, and you’re potentially breaking the law.

There are still those who will argue that it’s good these activities have been made illegal. After all, if you go to the park and sit at a bench, you might pick up coronavirus from someone who was just sitting there, or leave some behind for somebody else. If you go for a drive, you may need to stop for petrol, or break down and need mechanical assistance… more exposures means more risk for vulnerable Australians. The elderly, those with chronic illness, Indigenous Australians and immunocompromised people might be more at risk if you do this. However, it doesn’t follow from this that we should threaten people with prison sentences for failing to play ball.

In suspending our ordinary ways of life, we don’t also suspend the moral norms and ethical principles that give them direction and meaning. Punishments should still be reasonable and proportionate to the offenses; we should still aim to strike a reasonable balance between risk, security and freedom.

As Schwatz Media’s Osman Faruqi – who has been following the authoritarian developments around COVID-19 management – noted ,we should remember that increased law enforcement itself carries a cost. Whilst we’re all equal before the law in principle, in practice, minority communities, the poor, homeless and a range of other groups – vulnerable Australians – tend to bear the brunt of increased police activity around the world.

Police have been encouraged to use their discretion in enforcing these laws, but discretion is subject to bias and inconsistency, as is any other aspect of our decision-making. If new police powers are necessary to protect vulnerable Australians from COVID-19, who will be protecting the Australians made vulnerable by these new laws?

In the best-selling board game, Pandemic: Legacy, players have to combat a fast-evolving, unknown virus, using various measures. Options range from quarantines to military lockdowns to the literal, nuclear option. However, because the goal of the game is simply to ensure humanity’s survival and the effective control of the pandemic, these options are all seen as morally equal.

In a game, that’s fine. In reality, as we go from suspending ordinary life to suspending more basic moral and political norms and rights, we need to be able to understand and consider the costs it involves. We can’t do that if our sole metric for success is flattening the curve.

In his column, John Daley wrote that “Covid-19 is the real-life “trolley problem” in which someone is asked to choose between killing a few or killing many.” This framing only obfuscates the deeper issues which pit health and safety against other essential political values; short-term outcomes against a long-term political landscape and the competing needs of different of vulnerable communities.

That’s not a simple trolley problem, it’s a political smorgasbord. And we need a much more sophisticated scoring system to work out what success looks like.

You can contact The Ethics Centre about any of the issues discussed in this article. We offer free counselling for individuals via Ethi-call; professional fee-for-service consulting, leadership and development services; and as a non-profit charity we rely heavily on donations to continue our work, which can be made via our website. Thank you.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

FODI launches free interactive digital series

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture, Climate + Environment, Politics + Human Rights

Why you should change your habits for animals this year

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

What money and power makes you do: The craven morality of The White Lotus

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Teleology

BY Matthew Beard

Matt is a moral philosopher with a background in applied and military ethics. In 2016, Matt won the Australasian Association of Philosophy prize for media engagement. Formerly a fellow at The Ethics Centre, Matt is currently host on ABC’s Short & Curly podcast and the Vincent Fairfax Fellowship Program Director.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Could a virus cure our politics?

Could a virus cure our politics?

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + LeadershipPolitics + Human Rights

BY Simon Longstaff The Ethics Centre 27 MAR 2020

The COVID-19 pandemic of 2020 will no doubt be remembered for many things.

I wonder if one of the more surprising outcomes will be that our political leaders collectively managed to win back the trust and legitimacy they squandered over the past couple of decades. I hope so – because as we are now seeing in this time of crisis, it really matters.

The past few days have seen Prime Minister Scott Morrison describe panic-shoppers as engaging in behaviour that is “ridiculous” and “un-Australian”. He has had a crack at people who flocked to Bondi Beach in the recent warm weather for not taking seriously the requirements for physical distancing. He is right on both counts. However, his message is blunted by the lack of authority attached to his office. This is part of a larger problem.

The government’s meta-narrative is now one in which responsibility for the nation’s fate is tied to the behaviour of its citizens. The message from our political leaders is clear: ‘You – all of you (the people) – must take responsibility for your choices’.

Again, they are right. It’s just a terrible pity that the potency of the message is undermined by the hypocrisy of the messengers – a group that has refused to take responsibility for pretty much anything – in recent years.

Consider the most recent case of the infamous Sports Rort – in which Government Ministers (including the Prime Minister) offered the ‘Bridget McKenzie’ defence that ‘no laws were broken’. They wriggled and squirmed even further – in an attempt to deflect any and all criticism. Of course, ordinary Australians saw through the evasions and put it all down to political ‘business as usual’.

I recognise that it is unfair to focus on a single incident as indicative of all that has happened to erode trust and legitimacy. McKenzie and Co’s behaviour is just the most recent example of a longer, larger trend. A more equitable reckoning would say to the whole of the political class that we are sick of your blame-shifting, your evasiveness, your self-serving hair-splitting, your back-stabbing, your blatant lies (large and small), your reckless (no, gutless) refusal to accept responsibility for your errors and wrong-doing … your loyalty to the machine rather than to the people whom you are supposed to serve.

The split between ethics and politics was not always so evident. For Ancient Greeks, like Aristotle, each was a different side of a single coin. Ethics dealt with questions about the good life for an individual. Politics considered the good for the life of the community (the polis). The connections were not accidental – they were intrinsic to the understanding of the relationship between people and the communities of which they formed a part. As Umberto Eco once observed, the ancient world was a place of depth populated by heroes. In contrast, we moderns are fascinated by glittering surfaces and find satisfaction in celebrities.

The shallowness of much of modern life has fed into our politics – an arena within which marketing spin too often takes precedence over substance. Some seek to excuse this tendency by saying that our politicians merely reflect the society they represent. It is said that we should demand nothing more of political leaders than what we expect of ourselves. Really? Is that really good enough?

So, how should we respond to this?

Let’s write to our politicians, phone their offices … bombard them with messages of encouragement. Let’s ask them to rise to the occasion – to prove to us (and perhaps to themselves) what they could be.

Let’s appeal to the neglected idealist living buried beneath the callouses. Let’s tell them that they are needed; that they have a noble calling. Let’s enrol them in our dream of a better democracy – one that truly serves the interests of its citizens. Let them be our champions – let them drive out of their ranks anyone who refuses to be and do better.

Let’s imagine what it would be like if, at the end of this year, we were proud of our politicians and the quality of government that they had offered us at a time of crisis.

You can contact The Ethics Centre about any of the issues discussed in this article. We offer free counselling for individuals via Ethi-call; professional fee-for-service consulting, leadership and development services; and as a non-profit charity we rely heavily on donations to continue our work, which can be made via our website. Thank you.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Explainer: Getting to know Richard Branson’s B Team

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Is it wrong to care about Ukraine more than other wars?

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

The rights of children

Explainer

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights

Ethics Explainer: Dirty Hands

BY Simon Longstaff

Simon Longstaff began his working life on Groote Eylandt in the Northern Territory of Australia. He is proud of his kinship ties to the Anindilyakwa people. After a period studying law in Sydney and teaching in Tasmania, he pursued postgraduate studies as a Member of Magdalene College, Cambridge. In 1991, Simon commenced his work as the first Executive Director of The Ethics Centre. In 2013, he was made an officer of the Order of Australia (AO) for “distinguished service to the community through the promotion of ethical standards in governance and business, to improving corporate responsibility, and to philosophy.” Simon is an Adjunct Professor of the Australian Graduate School of Management at UNSW, a Fellow of CPA Australia, the Royal Society of NSW and the Australian Risk Policy Institute.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Ethics in a time of coronavirus

Ethics in a time of coronavirus

Opinion + AnalysisHealth + WellbeingPolitics + Human RightsRelationships

BY Simon Longstaff The Ethics Centre 12 MAR 2020

The response to the novel coronavirus COVID-19 (now called severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2, or SARS-CoV-2) has been fascinating for a number of reasons. However, two matters stand out for me.

The first matter concerns the way that our choice of narrative framework shapes outcomes. From what we know of SARS-CoV-2 it is highly infectious and produces mortality rates in excess of those caused by more familiar forms of coronavirus, such as those that cause the common cold. However, given that ‘novelty’ and ‘danger’ are potent tropes in mainstream media, most coverage has downplayed the fact that human beings have lived with various forms of coronavirus for millennia.

The more familiar we are with a risk, the more likely we are to manage it through a measured response. That is, we avoid the kind of panicky response that leads people to hoard toilet paper, etc. We can see how a narrative of familiarity works, in practice, by comparing the discussion of SARS-CoV-2 with that of the flu.

John Hopkins reports that an estimated 1 billion cases of flu (caused by a different type of virus) lead to between 291,000 and 646,000 fatalities worldwide each year. That is the norm for flu. Yet, our familiarity with this disease means that the world does not shut down each flu season. Rather than panic, we take prudent measures to manage risk.

I do not want to understate the significance of SARS-CoV-2, nor diminish the need for utmost care and diligence in its management. This is especially so given human beings do not possess acquired immunity to this new virus (which is mutating as it spreads). Furthermore, SARS-CoV-2 is currently thought to generate mortality rates greater than most strains of the flu.

However, despite this, I wonder if society would have been better served by locating this new virus on the spectrum of diseases affecting humanity – rather than as a uniquely dangerous new threat.

This brings me to the second matter of interest that I think worth mentioning. Like many others, I have been struck by the universal commitment of Australia’s leading politicians to legitimise their decisions by relying on the advice of leading scientists.

I do not know of a single case of a politician refusing to accept the prevailing scientific consensus. As far as I know, there has been nothing said along the lines of, “all scientific truth is provisional” or “some scientists disagree”, etc. I have not heard politicians denying the need to take action because it might put some jobs at risk. Nor has anyone said that action is futile ‘virtue signalling’ because a tiny nation, like Australia, can hardly affect the spread of a global pandemic.

As such, I have been left wondering how to explain our politicians’ commitment to act on the basis of scientific advice when it comes to a global threat such as presented by SARS-CoV-2 – but not when it comes to a threat of equal or greater consequence such as presented by global warming.

Taken together – these two issues raise many important questions. For example: are we only able to mount a collective response under conditions of imminent threat? If so, is this why politicians so often play upon our fears as the means for securing our agreement to their plans? Does this approach only work when the risks can be framed in terms of our individual interests – and perhaps those of our immediate families – rather than the common good? Or, more hopefully, can we embrace positive agendas for change?

For my part, I still believe that people are open to good arguments … that they can handle complex truths – if only they are presented in accessible language by people who deserve to be trusted. It’s the work of ethics to make this possible.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

LGBT…Z? The limits of ‘inclusiveness’ in the alphabet rainbow

Big thinker

Relationships

Big Thinker: Jean-Paul Sartre

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Enwhitenment: utes, philosophy and the preconditions of civil society

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Power and the social network

BY Simon Longstaff

Simon Longstaff began his working life on Groote Eylandt in the Northern Territory of Australia. He is proud of his kinship ties to the Anindilyakwa people. After a period studying law in Sydney and teaching in Tasmania, he pursued postgraduate studies as a Member of Magdalene College, Cambridge. In 1991, Simon commenced his work as the first Executive Director of The Ethics Centre. In 2013, he was made an officer of the Order of Australia (AO) for “distinguished service to the community through the promotion of ethical standards in governance and business, to improving corporate responsibility, and to philosophy.” Simon is an Adjunct Professor of the Australian Graduate School of Management at UNSW, a Fellow of CPA Australia, the Royal Society of NSW and the Australian Risk Policy Institute.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Big Thinker: Michael Sandel

Big Thinker: Michael Sandel

Big thinkerPolitics + Human Rights

BY Dr Laura D’Olimpio The Ethics Centre 9 MAR 2020

Prominent contemporary American political philosopher, Michael J. Sandel’s (1953—present) work on justice, ethics, democracy and markets has connected with millions around the world.

His popular first year undergraduate course, Justice, became Harvard University’s first freely available course – online and televised.

Sandel’s Socratic approach connects moral and political theories and concepts to everyday life, helping to engage his audience in otherwise complex philosophical ideas.

He recognises, “there is a great hunger…to engage in serious reflection on big, ethical questions that matter politically, but also that matter personally.”

We all face ethical and political dilemmas, decisions and disagreements. These are not always easy to resolve and often bring us into conflict with others whose views differ from our own. Sandel is quite clear on the remedy, that “we need to rediscover the lost art of democratic argument” and this is precisely what he models and facilitates.

Who we are

Sandel is known for emphasising the social aspects of our identities. He says that we think of ourselves “as members of this family or community or nation or people, as bearers of this history, as sons or daughters of that revolution, as citizens of this republic”, which illustrates our attachment to others as well as our contextual social reality. In this way he offers a critique of Rawlsian liberalism.

Liberalism, and particularly the view espoused by John Rawls in his 1971 book A Theory of Justice, sees people as highly individualised, rational and focussed on defending their rights. On this view, the government’s role is to protect individual freedom and fairly obtain and distribute resources.

Rawls’ famous thought experiment of the ‘veil of ignorance’ asks us to imagine ourselves prior to knowing who we are going to be in the world. If we do not know whether we will be male or female, able-bodied or beautiful or the opposite, or which race, class, or religion we will belong to, we should be able to fairly decide on the best policies by which a society should operate. This is the best way, Rawls believed, to achieve justice.

Conversely, Sandel argues that humans cannot be neutral in this way. When figuring out what we should do, people bring their “moral and spiritual encumbrances, traditions, and convictions” with them to the negotiating table.

In this way, talk of rights can only be understood in relation to what people think of as good, valuable and important in their lives, which is connected to their social and material circumstances. Thus, the abstract thought experiment Rawls details simply won’t work.

Civic engagement

Against the view that we are always free to choose what and who we care about and which are our special obligations, Sandel points out that certain commitments, such as those to our family and our political community, bind and restrict us in certain ways.

Precisely because we cannot be disinterested or disconnected when it comes to matters of political decision making, Sandel emphasises the importance of finding ways to support and increase civic engagement – as evidenced in his TED talk, The lost art of democratic debate, watched by over 1.4 million people.

By having a positive and active national political community that works towards the good of all, we can make sense of justice for real people situated in real world contexts. In this respect, he believes dialogue and respectful disagreement are vital.

“If everyone feels they are heard, even if they don’t get their way, they will be less resentful than if we pretend we are going to decide policy in a way that is neutral.”

Market societies

Something that really concerns Sandel is how we, in developed countries, have gone from having a market economy to becoming market societies. What this means is that everything is up for sale. If market thinking and market values dominate, then other values – those of the good life, education, relationships, and creativity – are squeezed out.

If everything is valued first and foremost economically, then the difference between the haves and have-nots matters. If money buys you a better education, better health care, better legal representation, as well as more material possessions and business opportunities, the cycle of poverty becomes increasingly insurmountable.

The ‘luck’ of being born into wealth should not count more towards one’s success than hard work, natural talent or intelligence. Yet this is increasingly evident in today’s world and, in this way, inequality and affluence determine much more than they should. As a result, the notion of ‘merit’ is loaded.

Sandel claims we live in a meritocratic society, yet merit itself is a tyrannical construct:

“The notion that your fate is in your hands, that ‘you can make it if you try!’ is a double-edged sword. Inspiring in one way, but invidious in another. It congratulates the winners, but denigrates the losers, even in their own eyes”.

Instead, we need to be more inclusive and recognise that everyone has a role to play in our shared fate, regardless of who is wealthy or poor. In order to move forward together, “we need to find our way to a morally more robust discourse, one that takes seriously the corrosive effect of meritocratic striving on the social bonds that constitute our common life.”

Posing provocative questions such as: Should you pay a child to read a book? Should a prisoner pay to upgrade their accommodation? Can we place a monetary value on the Great Barrier Reef? Sandel compels us to consider what values should govern civic life, and how we might rethink the role of the market in a democratic society.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Climate + Environment, Politics + Human Rights

Who is to blame? Moral responsibility and the case for reparations

Big thinker

Politics + Human Rights

Big Thinker: John Locke

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Politics + Human Rights

Vaccines: compulsory or conditional?

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights

Hunger won’t end by donating food waste to charity

BY Dr Laura D’Olimpio

Dr Laura D’Olimpio is senior lecturer in philosophy of education at the University of Birmingham, UK, and co-edits the Journal of Philosophy in Schools.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

CoronaVirus reveals our sinophobic underbelly

CoronaVirus reveals our sinophobic underbelly

Opinion + AnalysisHealth + WellbeingPolitics + Human RightsRelationships

BY Simon Longstaff The Ethics Centre 6 MAR 2020

A virus knows no race. It is indifferent to your religion, your culture and your politics. All a virus ‘cares about’ is your biology … For that, one human is as good as any other.

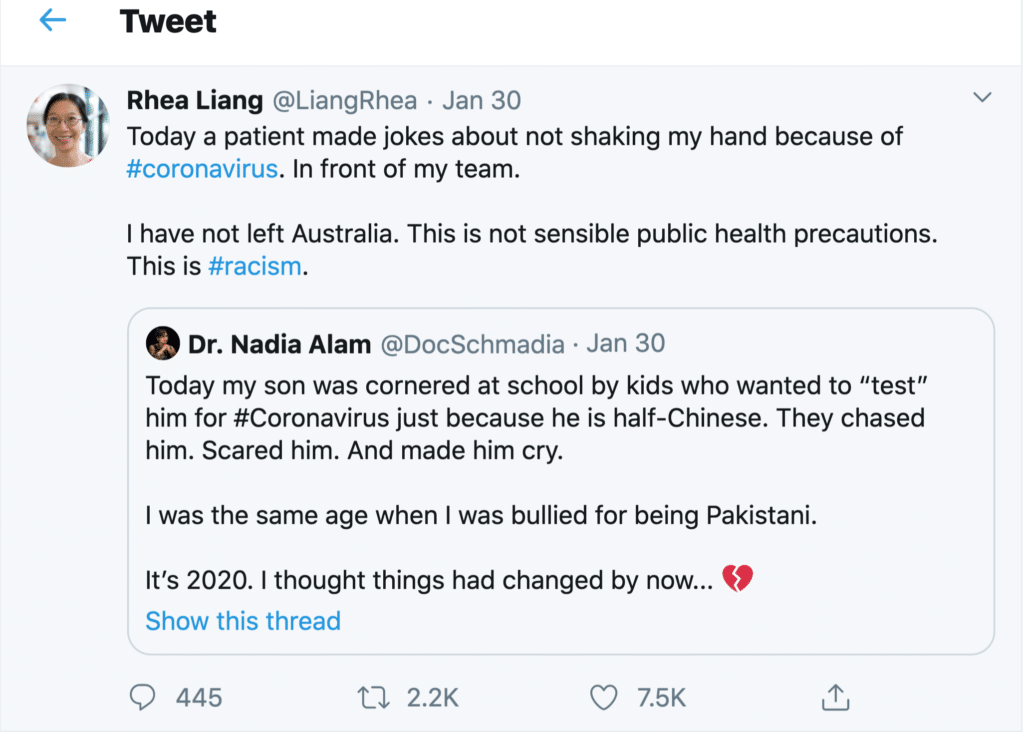

Despite this, it’s easy enough to find recent reports of Australians experiencing discrimination for no reason other than their Chinese family heritage.

Such attacks are examples of racism – the irrational belief that an individual or group possesses intrinsic characteristics that justify acts of discrimination. That this is occurring is not in doubt.

For example, Australia’s Chief Medical Officer, Professor Brendan Murphy has seen enough of such behaviour to make explicit reference to the phenomena, labelling xenophobia and racial profiling as “completely abhorrent”.

Professor Murphy’s position is one of principle. However, there is also a practical aspect to his admonition. Managing the risks of an outbreak of a pathogen like the novel coronavirus COVID-19 requires health officials and the wider community to make rational choices based on an accurate assessment of risk. Racism is irrational. It distorts judgement and draws attention away from where the risks really lie. Ethically it is wrong. Medically, it is idiotic and dangerous.

This rise in racism, prompted by the emergence of COVID-19, reveals how thin the veneer of decency is that keeps latent racist tendencies in check. It seems that, given half-a-chance, the mangy old dog of Sinophobia is ready to raise its head, no matter how long it has laid low.

Of course there is nothing new about Sinophobia in Australia. Fear of the ‘yellow peril’ is woven through the whole of Australia’s still-unfolding colonial history. Many factors have stoked this fear, including: persistent doubts about the legitimacy of British occupation of an already settled continent, ignorance of (and indifference to) Chinese history and culture, the European cultural chauvinism that such ignorance fosters, the belief that numerical supremacy is, ultimately, a determining force in history, the need to find scapegoats when the dominant culture falters, and so on.

Whatever the historical cause of this persistent fear, the present ‘trigger’ is the inexorable rise of China as an economic and military super power – a power that is increasingly inclined to demand (rather than earn) deference and respect.

The situation is made more volatile by the growing tendency for the China of President Xi Jinping to link its power and success to what is uniquely ‘Chinese’ about its history and character. Add to this a broadly accepted Chinese cultural preference for harmony and order and the nation is often presented as if it is a ‘monolithic whole’ – not just in terms of its autocratic government but in its essential character.

Unfortunately, all of this feeds the beast of racist prejudice. Those who feel threatened by the changing currents of history seize on even the flimsiest threads of difference and use these to weave a narrative of ‘us’ and ‘them’ – in which others are presented as being essentially and irremediably different. This is the racists’ central trope – that difference is more than skin deep! Biology makes you one of ‘us’ or you are not.

It’s nonsense. Yet, it’s a nonsense that sticks in some quarters, especially during times of uncertainty such as this; when the general public is feeling betrayed by the elites, when institutions have lost trust and have weakened legitimacy and when increasing numbers of people fear for their future and that of their families.

Unfortunately, tough times provide fertile ground for politicians who are willing to derive electoral dividends by practising the politics of exclusion. It is a cheap but effective form of politics in which people define their shared identity in terms of who is kept outside the group.

It is far harder to practise the politics of inclusion – in which disparate groups find a common identity in the things they hold in common. This too can work, but it takes great energy and superior skills of leadership to achieve this outcome. Yet, it is the latter approach that Australia must look for, if only as a matter of national self-interest.

This is because racist attacks against Australians of Chinese descent also have a significant national security dimension. As I have written elsewhere, social cohesion is a vital component of a nation’s ‘soft power’ when defending against foes who covertly seek to ‘divide and conquer’.

The risk of such attacks is increasing as the world drifts back to a pre-Westphalian strategic environment in which the international, rules-based order breaks down and nations freely interfere with the domestic affairs of their rivals. In these circumstances, the last thing Australia needs is deepening divisions based on spurious beliefs about supposed racial deliveries.

Those who create or exploit those divisions wound the body politic, weaken our defences and undermine the public interest.

All of that said, it is important not to overstate the dimensions of the problem. Australia is a notable successful multicultural nation where harmonious relations prevail. This is despite there being an undercurrent of racism that has been more or less visible throughout Australia’s modern history.

Racism is never justified. Not by the fact that it is found to the same degree in other societies, and not even when its manifestation is rare. Although it offers little comfort, it should also be acknowledged that discrimination is as much a product of other forms of prejudice concerning religion, gender, culture, etc.

We have the capacity to do and be better. This is a choice we can and should make for the sake of our fellow citizens – whatever their background – and in the interests of the nation as a whole.

So, given that China is not likely to take a backwards step and Australians of Chinese background cannot (and should not) disguise their heritage, how should we respond to the latest bout of Sinophobia?

Attack prejudice with fact

A first step should be to follow the example of Australia’s Chief Medical Officer and attack prejudice with the facts. Professor Murphy’s example showed how facts about medicine can be deployed to calm fears and neutralise racist myths. This approach should be extended to other areas. For example, more should be known of the long history and extraordinary contribution of Australians of Chinese heritage.

This account should not merely tell the story of elite performance, economic contribution, etc. It should also speak of those who have fought in Australia’s wars, built its infrastructure, educated its children, nursed its sick … and so on. In short, we need to see more of the extraordinary in the ordinary.

Reframe the narrative

Second, we need to reframe the narrative about China and the Chinese. Today, most commentary portrays China as both a security threat and an economic enabler. It is both. However, this is only a small part of the story.

For the most part, we see little of the life of the Chinese people. We are largely ignorant of the achievements of their remarkable civilisation. One might think that the closeness of the economic relationship might be a positive factor. However, regular reporting about Australia’s economic dependence on China, is not helping the situation.

I know that this will seem counter-intuitive to some. However, the more we speak of Chinese students propping up our universities, of Chinese tourists sustaining our tourism industry and of Chinese consumers boosting our agricultural exports … the more it makes it sound as if the Chinese are little more than an economically essential ‘necessary evil’ – a ‘commodity’ that comes and goes in bulk.

This view of the Chinese negatively influences attitudes towards Australia’s own citizens of Chinese descent. Fortunately, a solution to the ‘commodification’ of the Chinese is at hand, if only we wish to embrace it. The large number of Chinese students who study in Australia offer an opportunity to build better understanding and stronger relationships.

Unfortunately, the Chinese student experience in Australia is reported not to be as positive as it should be. Too many arrive without the English language skills to engage more widely with the community. Too many find themselves lonely and isolated. Too many find solace in sticking with those they know and understand. With some justification, large numbers feel as if they are little more than a ‘cash cow’.

Invest in ethical infrastructure

Third, we need to invest in Australia’s own ‘ethical infrastructure’ – much of which is damaged or broken. We need to repair our institutions so that they act with integrity and merit the trust of the wider community. We need to work on the core values and principles that underpin social cohesion.

Part of this task must be to come to terms with the truth about the colonisation of Australia. This is not to invoke the ‘black arm band’ view of history. The truth is both good and bad. However, whatever its character, our truth remains untold. I sincerely believe that Australia’s ‘soft power’ is weaker than it would otherwise be, if only we could address this unfinished business.

Alleviate fear

Fourth and finally, the measures outlined above will be ineffective unless we also name the latent fears of average Australians. People across the nation want these ‘bread and butter’ issues to be acknowledged and addressed:

- How safe is my job?

- If I lose my current job, will I find another?

- If I can’t find another job, how will I pay my bills?

- Will I be cared for if I get sick?

- Will my children get an education that equips them to live a good life in the future?

- Can I move about with relative ease and efficiency?

- How will the nation feed itself?

- Are we safe from attack?

- Who can step in cases of natural disaster or man-made calamity?

- Why are our leaders not held to account when we are?

- Why can’t I be left alone to do as I please?

- Who cares about me and those I care about?

Failure to speak to the truth of these deep concerns leaves the field wide open for the lies of those who would stoke the fires of racism.

Unravel the complexities of the political relationship between China and Australia at ‘The Truth About China’, a panel conversation at The Festival of Dangerous Ideas, Saturday 4 April. Tickets on sale now

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

Can beggars be choosers?

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

A good voter’s guide to bad faith tactics

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

To live well, make peace with death

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships, Society + Culture

The sticky ethics of protests in a pandemic

BY Simon Longstaff

Simon Longstaff began his working life on Groote Eylandt in the Northern Territory of Australia. He is proud of his kinship ties to the Anindilyakwa people. After a period studying law in Sydney and teaching in Tasmania, he pursued postgraduate studies as a Member of Magdalene College, Cambridge. In 1991, Simon commenced his work as the first Executive Director of The Ethics Centre. In 2013, he was made an officer of the Order of Australia (AO) for “distinguished service to the community through the promotion of ethical standards in governance and business, to improving corporate responsibility, and to philosophy.” Simon is an Adjunct Professor of the Australian Graduate School of Management at UNSW, a Fellow of CPA Australia, the Royal Society of NSW and the Australian Risk Policy Institute.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Disease in a Time of Uncertainty

Disease in a Time of Uncertainty

Opinion + AnalysisHealth + WellbeingPolitics + Human Rights

BY Nick Evans 19 FEB 2020

If you’re reading this, there’s a good chance you’ve heard of the outbreak of coronavirus, officially called “SARS-CoV-2”, that has caused disease primarily in Wuhan, China.

The virus, which causes a disease called coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), has spread to 25 countries, infected more than 73,000 people, and caused 1,873 deaths. The World Health Organization has declared the outbreak a “Public Health Emergency International Concern” and more than 50 countries — against the WHO’s advice — have implemented travel restrictions and quarantines in an attempt to prevent the spread of the disease.

There’s been a lot of worry about this coronavirus, but arguably the thing that is driving this worry is uncertainty. It can’t be the deaths alone – fewer than 1,900 people have died of COVID-19. In contrast, since October, 14,000 people in the USA alone have died of influenza.

Unlike the 1918 influenza pandemic or the 2009 influenza pandemic, both of which killed young people faster than normal flu, the people who are dying of COVID-19 are typically old, have pre-existing diseases that make them vulnerable to pneumonia (one of the main ways COVID-19 kills you), or are heavy smokers.

Despite its rapid increase in cases in China — driven, in part, by a change in definition of how they count cases — the number of cases elsewhere has stayed relatively low.

A reported 2.5 per cent of the patients diagnosed in China have died, yet fewer than 0.4 per cent of patients elsewhere in the world have died – a bit more than seasonal flu, but not much, and not as widely.

So why the fear? And why the fantastical conspiracies: tens of thousands dead but hidden in China; a laboratory escape; or even a biological weapon? There are surely a lot of reasons: the actions of the Chinese government during the 2003 SARS outbreak; general distrust of China in a media responding to Washington’s belligerence; and some enterprising grifters out to make their name or make a buck.

Still, these all take hold in an environment of uncertainty. And in ethics, how we deal with uncertainty is a tricky case. A classic example of why uncertainty can be tricky from the perspective of ethics goes something like this.

Say I ask you to play a game: I roll a normal dice; if it lands 1-5, you get $1; if it lands on a 6, you pay me $2. To many people this seems like a good deal. Five chances to win; one to lose. You should expect, mathematically, to win 50c each game. But what if I pull out a weird, many sided dice with 120 sides. If the dice land 1-119, you get $1. But if it lands 120, I get $59. It might feel different, but the expectation (again, mathematically) remains the same.

Now imagine a huge dice in which that one chance of a loss was $10,000, or even $1 million… Part of the reason it feels different is psychological. After all, $59, or $10,000 is so much more than $2, and so even though your chances of losing are decreasing, the pit in your stomach at the thought of losing $10,000 is probably a lot more. Moreover, you’re risking that for $1 each time. Sounds like playing with fate, and you might not want to play with fate when fate could take your house if it wins.

Another part of the reason it feels different is that we don’t often encounter — or at least don’t recognise — extreme cases in our lives where we face a small chance of a huge loss. My colleagues and I have looked at this phenomena in the case of things like laboratory safety, or industrial regulations. But the same goes for things like pandemics.

Coronaviruses circulate in animal populations, usually certain species of bat, and typically don’t infect humans.

Occasionally a virus does, often through an intermediate species, and the results can be bad. It can be really hard to figure out how bad, though. So we don’t know when these viruses will appear, or how bad they are going to be.

Given that, it can be really easy to get complacent before the fact, and even easier to overreact after the outbreak starts. This leads us to take drastic actions such as to violate human rights in the name of protecting public safety (or at least appearing to protect safety), even when those actions are shown to be ineffective. But this is because instead of winning a dollar, preparedness costs us that dollar. It’s hard to get governments to spend dollars today that might not benefit us until 2030, but if we wait until we need it, we could lose everything.

It turns out that the best solution to these scary, uncertain diseases is to invest, as a society, day to day. That costs resources, but it’ll help out when the “big one,” the next 1918 flu, comes. COVID-19 is unlikely to be that kind of pandemic, but even it is testing global health systems.

We need, as a society, to get better at dealing with the uncertain, by investing in preparedness today.

Better healthcare systems; more nurses, doctors, and scientists; a more aware community; local plans for infection control that match the plans of national governments; and protections for people in quarantine so they don’t lose their livelihoods or, as is the case in some countries, have to pay for their own quarantine when they aren’t even sick.

These investments cost governments money. They cost us taxes. But if you’re scared of COVID-19, with all its uncertainty, you should be much more scared that we’re not doing the ordinary, everyday things that’ll keep us safe.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Explainer

Politics + Human Rights

Ethics Explainer: Ethics, morality & law

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing

HSC exams matter – but not for the reasons you think

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

Settler rage and our inherited national guilt

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships