How to have a difficult conversation about war

How to have a difficult conversation about war

Opinion + AnalysisRelationshipsPolitics + Human Rights

BY Tim Dean 4 OCT 2024

Many people feel they need to talk about the conflict unfolding in the Middle East, but others find that conversation distressing. Here’s how to have a conversation about ongoing conflicts in a safe way for everybody.

This year – and possibly for many years to come – October 7th is going to be a difficult day to endure for many people, not least those with a connection to Israel, Palestine, Lebanon and other countries in the Middle East. Even for those without a connection to those lands, the news of the conflict there is hard to avoid. Headlines are filled with tragedy, streets a filled with protestors, and walls are covered in posters howling in outrage or crying for justice for one side or the other.

In this environment, it’s not surprising that many people feel compelled to share their thoughts and feelings about the conflict. And it’s equally unsurprising that many others find it too distressing a topic to engage with, whether it’s because they are affected themselves or because they feel powerless to avert the unfolding tragedy.

People should also be forgiven for not engaging in an emotionally charged and potentially distressing conversation. While we should all have some awareness of major happenings around the world, we are not obligated to engage with those that don’t impact us or our community and are beyond our control.

However, a problem occurs when people of opposite dispositions meet, and some desperately want to talk about the conflict and others desperately want to avoid just such a conversation.

So, here are some approaches you can use if someone starts a conversation about the conflict, especially if that’s a conversation you’re not totally comfortable diving into.

Pause

Often, when we hear something that triggers a strong emotional reaction, especially if it’s a view we might disagree with, we react as we would to a physical threat: fight, flight or freeze.

Some reactively fight, and immediately push back with an alternative perspective. But if we start a conversation from a position of opposition, it shifts the dynamics into one of conflict rather than cooperation. That isn’t a problem if everyone has tacitly agreed to enter debate mode, but often that’s not the case, and conflict can easily trigger defensive reactions that cause the conversation to spiral into an unproductive clash, only heightening everyone’s emotions.

Others attempt to flee from the conversation, such as by changing the subject or even physically leaving the room. However, if the person raising the issue feels compelled to do so, they may remain unsatisfied and will just raise the issue again at another point. Freezing, on the other hand, may be perceived as tacit agreement to dive into the conversation, which might end up being harmful or distressing for those involved.

So, the first step for managing difficult conversations is to pause whenever you hit a point of contention or at the first indication of raised emotion, either in yourself or those you’re talking to. This gives you an opportunity to recognise and acknowledge your immediate reaction and quickly take stock of who else is in the conversation and what they might be feeling. And if we believe that someone in the conversation might be in genuine distress – including ourselves – then we can work to steer the conversation in a different direction.

Cast the net wider

One approach for steering a conversation away from potentially distressing content is to not engage with the content directly, but instead go “meta” and talk about what you’re talking about.

So, instead of sharing opinions or judgements about the conflict in the Middle East, ask questions about the conversation itself: why are people so invested in the conflict – especially if many of them don’t have a personal connection to those affected? How are people talking about it? Are the conversations going on around the country and in the media helping or are they divisive? How are these conversations affecting people, especially those who are connected to the conflict? How should we be talking about it?

Asking meta questions like these can shift the conversation away from the details and on to the human impact that the conversation is having. It can prompt everyone to reflect on their role – and responsibilities – when talking about potentially distressing subjects and cultivate empathy with those affected.

Going meta can also allow you to offer a more explicit invitation to take the conversation to another stage, giving everyone an opportunity to opt-in or opt-out. The meta conversation may have already helped to set some ground rules for how a conversation about the conflict might unfold, including what kind of language is appropriate and what kinds of topics are off limits out of respect for those affected.

Explore feelings

If you progress the conversation further – or if others feel compelled to do so – it doesn’t mean you need to dive straight into sharing your opinions on the conflict itself. Instead, there is another framing that can be equally, if not more constructive. This is the “expressive” frame.

Rather than asking people what they believe, invite them to share how the conflict makes them feel. This focuses the conversation on emotions and experience rather than opinions or judgements. There’s a subtle but important difference between the two.

We all have opinions and judgements about issues that are important to us, and are more than ready to offer reasons to support our attitudes. But as the American psychologist Jonathan Haidt has pointed out, many of these opinions and judgements ultimately stem from our emotional reactions.

When we experience outrage, for example, we immediately form a negative judgement of the perceived cause, and we often fish for reasons to support that judgement. This means that many of our reasons are post-hoc rationalisations of our emotional responses. If you start discussing these post-hoc rationalisations, you’re not really engaging with the root causes of how someone feels about an issue. Instead, it’s often far more fruitful to unpack the way they perceive the issue in the first place and discuss how that makes them feel.

Engaging in the expressive frame has another benefit: often people who have strong feelings about an issue have a deep need to have those feeling heard and validated by others. By asking how they feel and just listening to them and validating those feelings – without necessarily agreeing with their opinions – can satisfy them and might even prompt them to listen to how you feel about it.

Conversational scripts

Both the meta and expressive conversational modes are ways of engaging with difficult issues without tackling the substantive – and potentially harmful or distressing – content head on. They give you a chance at having a meaningful conversation that can be more sensitive and help protect those who might feel threatened or unsafe.

That said, it can be difficult in the heat of the moment to know what to say to shift the conversation to the meta or expressive frame. For this reason, it can be useful to have a few conversational scripts up your sleeve that you can whip out as needed.

If someone expresses outrage about some aspect of the conflict, the protests or political response, and you want to shift to the expressive frame, you could say: “I’ve been hearing about that everywhere. How do you feel when you hear about it?”

Or if you want to move away from commentary about distant news and ground it, perhaps ask: “Do you know anyone affected by the conflict? How are they faring?”

And if you want to shift to the meta frame, ask: “What do you think about the way people are talking about the conflict? Is that contributing to the division?”

Finally, it’s always useful to have some conversation exits ready and waiting in case things go off the rails or things become a bit too heated or distressing. You can say things like: “that reminds me of…”, or “I wanted to ask you about…”, or even “have you seen…”, and fill in the blanks with content that you think will be appealing to your conversation partner, whether that’s something about themselves (always a favourite topic), sport, popular culture or something else that everyone can relate to. There’s no shame in tactfully changing the subject when you feel a conversation has exhausted itself (or you).

Talking about difficult issues like the conflict in the Middle East can be distressing, but there are ways for you to take charge of the conversation and steer it in a way that is ethical, respectful and yet protects you and those around you.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Ozi Batla: Fatherhood is the hardest work I’ve ever done

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

The truths COVID revealed about consumerism

Explainer

Politics + Human Rights

Ethics Explainer: Deontology

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Truth & Honesty

BY Tim Dean

Dr Tim Dean is a public philosopher, speaker and writer. He is Philosopher in Residence and Manos Chair in Ethics at The Ethics Centre.

Where is the emotionally sensitive art for young men?

Where is the emotionally sensitive art for young men?

Opinion + AnalysisSociety + CultureRelationships

BY Joseph Earp 23 SEP 2024

The Sisterhood of the Traveling Pants, the 2005 young adult drama film, takes all of five minutes to set up its premise: what if you and your friends discovered the titular pair of jeans, which, despite your differences in size, fit you all perfectly? And, more than that, what if you all decided that these pants had magical behaviour-changing powers?

So far, so teen drama, particularly when the film starts unveiling the emotional canvas the film will play out on. Bridget (Blake Lively) has a crush, and a dead mother; Carmen (America Ferreira) is a child of divorce; Tibby (Amber Tamblyn) is stuck working a dead-end job.

But what is extraordinary about the film is the sensitivity with which it handles what could otherwise be tropes. Each of the heroine’s lives is disrupted by death and loss. They learn they are fallible; that they are subjected to forces they cannot control. They’re not whiny teenagers. They’re young people, making their way through the world – sometimes messily, but always with conviction.

The film is shockingly emotionally nuanced for a work of art made for, and about, teenagers. But what makes it more shocking is how plainly it exposes the absence of similar art for young men. The Sisterhood of The Traveling Pants – and films like it – are a core part of moral education, designed to validate young women in their feelings, both the positive and the negative. So, where is the male equivalent?

Art and moral education

None of this is to say that The Sisterhood of The Traveling Pants need only appeal to young women – the brush with which it paints is broad and vivid enough for those of any gender. But it still remains the case that the film was marketed to, and largely consumed by, young women. It sits alongside Stick It, She’s The Man, Riding In Cars With Boys, and Cinderella Story as part of an early 2000s trend of emotionally adult works directed towards young women. While these are stories are ostensibly about romance, they’re actually about self-discovery and self-possession.

Such films, as philosopher Greta T. Cullen observes, need not necessarily be “morally instructive” – as in, they don’t need to have all the moral answers. Instead, they ignite sympathy. They teach us both about our own world, and the worlds of those around us. As Cullen puts it, they “encourage an awareness of other people, their problems and sufferings.” Through that awareness, we can build a proper moral system – after all, it’s only when we understand how we affect other moral agents that we can decide how to treat them.

That, in fact, is precisely what makes art so important in moral education. The Sisterhood of the Traveling Pants isn’t prescriptive – it doesn’t tell us exactly what we should do. In fact, its heroines make more mistakes than most: Tibby, whose life is changed by a young girl with cancer, initially declines to visit her dying friend in hospital. The film isn’t an instruction guide. Instead, it’s a sort of training ground for sympathy, reminding us of the impact we have on each other – and the seriousness with which we should take that impact. Art, at its best, makes the world bigger. And after it has done that, we get to decide what to do with all that extra space.

The stoic male hero

Art targeted at young men is far less interested in interiority. Consider the likes of Deadpool, Top Gun: Maverick, and The Fast and The Furious films. These works of art are not interested in emotional nuance in the same way as The Sisterhood of the Traveling Pants is, because they’re not centred around emotionally changeable characters. Neither Deadpool nor Dominic Toretto need overcome internal obstacles – only external ones.

Art for young men tends to promote stoicism or, at the very least, inflexible leading men. Leads of young adult films directed at men are primarily unflappable – above all else, they value calm, and decisiveness. They are what Jon Brooks describes as “stoic superheroes”.

That’s not to say such art needs to be entirely dismissed – it has other uses. But the hole in male education around emotions – what we do with them, how they shape us – has profound knock-on effects.

When your heroes don’t validate you in your emotional complexity – in your essential fallibility – your moral life suffers. There is a loneliness to growing up without seeing a complex inner life on the screen. Films should, in some complicated way, forgive us. They should make it clear that we are not alone.

That loneliness is solidified by a further absence in young male cinema – a hole where there should be depictions of non-judgmental, accepting friendships. The “buddy comedy” genre does aim to rectify this gap, but such films are few and far between. The Sisterhood Of The Traveling Pants models genuine connection between its heroes, who are willing to be their true selves around each other. There is no real corollary for men.

There’s a sequence part way through The Sisterhood of the Traveling Pants where Tibby, the teenage shelf-stacker, steps out into the quiet of the afternoon, surrounded by her middle-aged co-workers as they smoke in the sun. She says nothing; they say nothing.

Later, this will become the setting where Tibby learns not just about loss, but also about the hard-won work required to give life meaning. For the moment though, all that happens is that Tibby stands there, the sky orange around her, and takes pause. It’s a moment of true emotional vulnerability – a brief flash of Tibby sitting in her feelings.

And that vulnerability is important. Without that vulnerability, genuine emotional connection is impossible. Which is why the dearth of such moments in art aimed at young men has such worrying implications. Many men struggle with their own vulnerability; struggle to feel authentic, and true. From that comes loneliness. From that comes pain.

There is a hole in male education, and it’s shaped exactly like this film. And, more specifically, a hole shaped like the image of a young woman, standing in the sunshine, staring straight ahead, and then slowly walking offscreen.

Image: Warner Bros. Pictures

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

The philosophy of Virginia Woolf

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Vulnerability

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture

FODI returns: Why we need a sanctuary to explore dangerous ideas

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Australia’s paid parental leave reform is only one step in addressing gender-based disadvantage

BY Joseph Earp

Joseph Earp is a poet, journalist and philosophy student. He is currently undertaking his PhD at the University of Sydney, studying the work of David Hume.

What we owe to our pets

Australians love having pets around. But what are our obligations to our animal companions?

Much has been said about the benefits of living with pets – from companionship to improved mental and physical health. Out of two thirds of Australia households that are home to at least one pet, a whopping 85% of owners have said that pets have a positive impact on their lives.

In other words, they’re good for us. But are we good for them? And what are our obligations in these relationships so many of us find ourselves in?

Legally, we own animals. We purchase them, register them as our pets, and pay for their routine and emergency health care where required. In this way, pets are similar to property. But that doesn’t mean we can treat them like ordinary property.

Unlike us, animals are not typical “moral agents”. They cannot make and enact ethical decisions, like choosing between different foods based on their carbon footprint, or making an informed choice about breeding if there is a risk of passing a heritable disorder to offspring.

Pets fall into the category of “moral patients” – beings who matter morally, but who are subjects of our moral consideration and actions. They need us to make good decisions for them. This is especially important because we take them out of their natural environment and bring them into our homes, environments designed specifically to cater to the needs of our species. We require animals to live within these spaces and adapt to our lifestyles.

Sometimes we forget how challenging this can be. For example, animals may be nocturnal, but we expect them to adapt to the hours we keep. Indoor dogs rely on us to provide outside access for toileting and exercise. Cats rely on us to change their litter tray and provide suitable surfaces to scratch and climb. They cannot predict when our routines – and hence their routines – will change.

As a veterinarian, sometimes my client (a human) will tell me that my patient (an animal), urinated outside of the designated toileting area “to spite them” when they were late home from work. It is not uncommon for humans to attribute hostile intentions to animals who display behaviours we find problematic, when these behaviours may be manifestations of an animal’s frustration if their needs are not met (e.g. provision of multiple litter trays for cats, lack of choice).

As a result, shelters are full of animals who have, for one reason or another, not been able to adapt to human behaviour. This is not the fault of the animal; it’s often due to our unrealistic expectations.

In Australia, we tend to think of “responsible pet ownership” as ensuring that pets are well behaved (that is, they do not cause a nuisance to others), that they are microchipped, desexed and registered, and that we provide appropriate food, water, shelter and veterinary care as required.

Though many people would characterise their role in terms that go beyond “ownership”. Indeed, the use of the term “pet owner” has decreased, in favour of terms like “guardian” or “caretaker” or even “pet parent”. This reflects a view that animals are more like family members than property.

Animal welfare science and legislation increasingly reflect the position that we need to provide animals with lives worth living, or good lives. That is, not just minimisation of poor welfare and associated negative mental experiences or feelings, but striving to maximise positive mental experiences.

The early view of good animal welfare was informed by the “Five Freedoms” model of animal welfare. These include freedom from: pain, injury and disease; fear and distress; discomfort; hunger and thirst; and to express normal behaviour.

But according to the more recent “Five Domains”, physical and functional factors including nutrition, physical environment, health, behavioural interactions with other animals, humans and the environment) influence mental experiences (the fifth domain).

This model stresses that what matters most to animals is their subjective experiences. Therefore, just acting to minimise negative mental experiences (such as confining a dog to stop them running on the road and experiencing a painful injury), doesn’t necessarily lead to positive welfare.

To ensure that an animal has a good life, they should be able to have more positive than negative experiences. With the example of the confined dog, that means providing, where possible, opportunities for positive interaction with animals, people and the environment. Walks. Sniffing. Chasing a ball (if that’s their game). Spending time with them. Of course, not all animals are social species. We need to pay attention to the preferences of animals, and, where possible, offer them choice, so they can experience positive welfare.

That doesn’t mean we shouldn’t make unpopular choices for them. While sentient animals – including humans – like to exercise choice or agency, we need to ensure that those choices are likely to lead to sustained positive welfare rather than poor welfare. So while an indoor cat may have a ravenous appetite, indulging the cat to the point where they become obese is likely to lead to poor welfare in the long term.

We need to remind ourselves that, as humans living in environments designed almost exclusively for humans, we expect a lot of our animal companions. In addition to meeting their basic needs, we should aim to provide them with good lives. This requires doing a bit of research, observing animals carefully, and learning from them. Our lives are richer for it.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

The new normal: The ethical equivalence of cisgender and transgender identities

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Epistemology

Explainer

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Critical Race Theory

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Should parents tell kids the truth about Santa?

BY Dr Anne Quain

Dr Anne Quain is a veterinarian with additional qualifications in the field of animal welfare. Anne is interested in all aspects of small animal health, particularly animal welfare. She also has a BA in arts, majoring in philosophy. Her PhD research explored the types of ethically challenging situations encountered by veterinary team members, and evaluated ’ethics rounds’, a form of clinical ethics support designed to foster a sense of moral community among veterinary team members. She is interested in exploring the impact of ethically challenging situations on veterinary practitioners and believes that philosophy must be accessible, engaging and ultimately practical.

Ethics explainer: The principle of charity

The principle of charity suggests we should assume good intentions about others and their ideas, and give them the benefit of the doubt before criticising them.

British philosopher and mathematician, Bertrand Russell, was one of the sharpest minds of his generation. Anyone deigning to offer a lecture in his presence at Cambridge University was sure to have every iota of their reasoning scrutinised and picked apart in excruciating detail.

Yet, it’s said that before criticising arguments, Russell would thank them warmly for sharing their views, then he might ask a question or two of clarification, then he’d summarise their position succinctly – often in more concise and persuasive terms than they themselves had used – and only then would he expose its flaws.

What Russell was demonstrating was the principle of charity in action. This is not a principle about giving money to the poor, it’s about assuming good intentions and giving others the benefit of the doubt when we interpret what they’re saying.

The reason we need charity when listening to others is that they rarely have the opportunity to say everything they need to say to support their view. We only have so many minutes in the day, so when we want to make an assertion or offer an argument, it’s simply not possible to account for every assumption, outline every implication and cover off all possible counterarguments.

That means there will inevitably be things left unsaid. Given our natural propensity to experience disagreement as a form of conflict, and thus shift into a defensive posture to protect our ideas (and, sometimes, our identity), it’s all too easy for us to fill in the gaps with less than charitable interpretations. We might assume the person speaking is ignorant, foolish, misled, mean spirited or riddled with vice, and fill the gaps with absurd assertions or weak arguments that we can easily dismantle.

We also have to decide whether they are speaking in good faith, or whether they’re just engaging in a bit of virtue signalling and didn’t really mean to offer their views up for scrutiny, or whether they’re trying to troll us. Again, it’s all too easy to allow our suspicions or defensiveness to take over and assume someone is speaking with ill intent.

However, doing so does them – and us – a disservice. It prevents us from understanding what they’re actually trying to say, and it blocks us from either being persuaded by a good point or offering a valid criticism where one is due. Failing to offer charity is also a sign of disrespect. And it’s well known that when people feel disrespected, they’re even more likely to double down on their defensiveness and fight to the bitter end, even if they might otherwise have been open to persuasion.

It’s probably no surprise to hear that the internet is a hotbed of uncharitable listening. Many people have been criticised, dismissed, attacked or cancelled because they have said or done something ambiguous – something that could be interpreted in either a benign or a negative light. Some commentators on social media are all too ready to uncharitably interpret these actions as revealing some hidden malice or vice, and they leap to condemnation before taking the time to unpack what the speaker really meant.

Charity requires more from us, but the rewards can be great. Charity starts by assuming that the person speaking is just as informed, intelligent and virtuous as we are – or perhaps even more so. It encourages us to assume that they are speaking in good faith and with the best of intentions.

It requires us to withhold judgement as we listen to what’s being said. If there are things that don’t make sense, or gaps that need filling, charity encourages us to ask clarificatory questions in good faith, and really listen to the answers. The final step is to repeat back what we’ve heard and frame it in the strongest possible argument, not the weakest “straw man” version. This is sometime referred to as a “steel man”.

Doing this achieves two things. First, the speaker will feel heard and respected. That immediately puts the relationship on a positive stance, where everyone feels less need to defend themselves at all costs, and it can make people open to listening to alternative viewpoints without feeling threatened.

Secondly, it gives you a fighting chance of actually understanding what the other person really believes. So many conversations end up with us talking past each other, getting more frustrated by the minute. Arriving at a point of mutual understanding can be a powerful way to connect with someone and have an actually fruitful discussion.

It is important to point out that exercising charity doesn’t mean agreeing with whatever other people say. Nor does it mean excusing statements that are false or harmful.

Charity is about how we hear what is being said, and ensuring that we give the things we hear every possibility to convince us before we seek to rebut them.

However, if we have good reason to believe that what they’re saying, after we’ve fully understood it in its strongest possible form, is false or harmful, then we need not agree with them. Indeed, we ought to speak out against falsehood and harm whenever possible. And this is where exercising charity, and building up respect, might make others more receptive to our criticisms, as were many of the people who gave a lecture in the presence of Bertrand Russell.

The principle of charity doesn’t come naturally. We often rail against views that we find ridiculous or offensive. But by practising charity, we can have a better chance of understanding what people are saying and of convincing them of the flaws in their views. And, sometimes, by filling in the gaps in what others say with the strongest possible version of their argument, we might even change our own mind from time to time.

This article has been updated since its original publication on 10 March 2017.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships, Society + Culture

Stop giving air to bullies for clicks

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Ethical judgement and moral intuition

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Appreciation or appropriation? The impacts of stealing culture

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

The role of emotions in ethics according to six big thinkers

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

In defence of platonic romance

When I was young and like many little girls, I was bewitched by all things magical and had a keen sense of romantic sensitivity.

I would regularly claim to spot mermaids in the froth of breaking waves and would meticulously construct fairy circles in my grandmother’s garden. These tendencies would lead me to weave fanciful and elaborate dreams about my future, mainly about love. In all the rituals, potions and stories I concocted as a young girl, there’s one that sticks out in my mind.

One particular holiday in the Blue Mountains, my cousin and I were around twelve – the age when many children start to fully understand what awaits them in teenagerhood – namely, romance. One night, under a full moon, I proposed a plan – we would cast a spell to summon our future partners and design our prince charmings. Petals were gathered from the flowering bushes that surrounded our accommodation and a large plastic salad bowl was stolen from the kitchenette and filled with water. With great reverence and solemnity, we sat on the deck and threw petals into the bowl. As each one hit the surface, we would say aloud a quality that we wanted in a future partner.

“Tall!”

“Nice!”

“Dark hair!”

When the ritual was over and the bushes were bare of their flowers, we threw the contents of the bowl out onto the lawn quite matter-of-factly. Completed with confidence, we did not doubt that what had transpired between us that night had set us up very nicely for when we were grown women. Now, as a young woman with aspirations for a career as a writer and a bachelor’s degree under my belt, I look back and question, with the opportunity of a full moon and a ritual, why did I only wish for a romantic relationship with a man?

In my developing mind, I had an understanding that women found their identity in being the object of romantic love. To be loved by a man was equated to being accomplished – one day when I was clever enough and pretty enough, I would be chosen. However, there’s little personal autonomy as an object.

Many pioneers of third-wave feminism have fought against the objectification of women and for their greater value in society. Much of their activism has focused on the role of women in social and political spaces. At twenty-two years old I’m still learning how to navigate my position in the world as a young woman. My sense of accomplishment with my career and my education has not always been constant. Upon reflection, there’s a source of value and abundance in my life that is disconnected from any metric measure of success – my friendships. Throughout the dawn of my adult years, my most impactful, and intimate relationships have been with my close female friends. If our platonic relationships were treated as reverently as our romantic ones, what would be possible?

Philosopher Simone de Beauvoir described the desire to love and be loved as part of the structure of human existence. Her 1949 work The Second Sex explores women as the ‘other’ in society and how men and women often develop asymmetrical expectations of love. De Beauvoir discusses heterosexual love as being either ‘authentic’ or ‘inauthentic’. Within her framework, to achieve authentic love, both lovers need to maintain their individuality. But in the context of heterosexual monogamy and the biological family unit, is this even possible for women?

Many women are often first and foremost identified as wives and mothers, essentially, they have relational autonomy. Relational autonomy proposes that as the ‘Self’ is related to those around us in various ways, the way we identify ourselves cannot be a practice that is achieved alone. While an explanation such as this may relate positively to ideas of community and comradery, many women experience a loss of self as wives and mothers.

Many women in heterosexual relationships must, to some degree, be experiencing inauthentic love – described by De Beauvoir as being based on inequality between the sexes:

“[Men] never abandon themselves completely […] they remain sovereign subjects; the woman they love is merely one value among others; they want to integrate her into their existence, not submerge their entire existence in her. By contrast, love for the woman is a total abdication for the benefit of a master.”

If our support systems and our identity are entangled with relationships that have an inherent power imbalance, is there space for authentic love? While De Beauvoir’s outlook may appear characteristically existential, there is a faint yet unmistakable silver lining. If heterosexual relationships leave women devoid of true identity and autonomy, what is left? Our female friendships.

Within my female friendships, I’ve rediscovered something from my childhood that’s been lacking in my romantic relationships with men – magic. There’s something about friendships between women that makes pagan behaviour seem reasonable. I can understand why medieval witches were often accused of dancing naked around bonfires; I would do that too for my best friends.

To be clear, I’m not saying that people don’t need romance or romantic relationships, nor am I saying that all heterosexual relationships cause harm to the women in them. Romantic relationships can be a source of unique joy and adventure. Where they become problematic is when they are the centre of our personal universes. As for romance, there’s space and, arguably, a necessity for it in our platonic relationships too. I implore you to buy a bouquet of flowers for your dearest female friend and see what good it does.

With platonic relationships at the centre of our worlds, there’s a web of support and intimacy without the power imbalance inherent in some heterosexual relationships.

By decentralising the role of romantic love in our lives and valuing other relationships just as equally, there’s an opportunity for community building, deep understanding, and cultivation of our own personal identity.

If, at twelve years old, under that Blue Mountains moon, I had wished for an ideal best friend – when, as an adult, my romantic relationships fell short of the mark again and again, it wouldn’t have felt like I had as far to fall. Rather than the sun dropping out of my personal solar system, I’d lose a moon or two. Still a knock to the system, just not an earth-shattering one. Perhaps, feminism and gender equality can be aided and progressed by revolutionary love for our friends.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

We already know how to cancel. We also need to know how to forgive

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Ageing well is the elephant in the room when it comes to aged care

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

The myths of modern motherhood

WATCH

Relationships

Purpose, values, principles: An ethics framework

BY Layla Zak-Volpato

Layla is a 22-year-old writer and poet living and working in and around Eora/Sydney. With an educational background in ecology and wildlife conservation, her work focuses heavily on the ethical and moral dilemmas of the anthropocene. Through a creative lens, Layla examines the intersections between gender, identity, philosophy and environmental issues. She aspires to use these themes as the backbone for a career as a scientific communicator who utilises both creative and informative literary forms.

Ethics Explainer: Shame

Flushed cheeks, lowered gaze and an interminable voice in your head criticising your very being.

Imagine you’re invited to two different events by different friends. You decide to go to one over the other, but instead of telling your friend the truth, you pretend you’re sick. At first, you might be struck with a bit of guilt for lying to your friend. Then, afterwards, they see photos of you from the other event and confront you about it.

In situations like this, something other than guilt might creep in. You might start to think it’s more than just a mistake; that this lie is a symptom of a larger problem: that you’re a bad, disrespectful person who doesn’t deserve to be invited to these things in the first place. This is the moral emotion of shame.

Guilt says, “I did something bad”, while shame whispers, “I am bad”.

Shame is a complicated emotion. It’s most often characterised by feelings of inadequacy, humiliation and self-consciousness in relation to ourselves, others or social and cultural standards, sometimes resulting in a sense of exposure or vulnerability, although many philosophers disagree about which of these are necessary aspects of shame.

One approach to understanding shame is through the lens of self-evaluation, which says that shame arises from a discrepancy between self-perception and societal norms or personal standards. According to this view, shame emerges when we perceive ourselves as falling short of our own expectations or the expectations of others – though it’s unclear to what extent internal expectations can be separated from social expectations or the process of socialisation.

Other approaches lean more heavily on our appraisal of social expectations and our perception of how we are viewed by others, even imaginary others. These approaches focus on the arguably unavoidably interpersonal nature of shame, viewing it as a response to social rejection or disapproval.

This social aspect is such a strong part of shame that it can persist even when we’re alone. One way to exemplify this is to draw similarity between shame and embarrassment. Imagine you’re on an empty street and you trip over, sprawling onto the path. If you’re not immediately overcome with annoyance or rage, you’ll probably be embarrassed.

But there’s no one around to see you, so why?

Similarly, taking the example we began with, imagine instead that no one ever found out that you lied about being sick. It’s possible you might still feel ashamed.

In both of these cases, you’re usually reacting to an imagined audience – you might be momentarily imagining what it would feel like if someone had witnessed what you did, or you might have a moment of viewing yourself from the outside, a second of heightened self-awareness.

Many philosophers who take this social position also see shame as a means of social control – notably among them is Martha Nussbaum, known for her academic career highlighting the importance of emotions in philosophy and life.

Nussbaum argues that shame is very often ‘normatively distorted’, in that because shame is reactive to social norms, we often end up internalising societal prejudices or unjust beliefs, leading to a sense of shame about ourselves that should not be a source of shame. For example, people often feel ashamed of their race, gender, sexual orientation, or disability due to societal stigma and discrimination.

Where shame can go wrong

The idea of shame as a prohibitive and often unjust feeling is a sentiment shared by many who work with domestic violence and sexual assault survivors, who note that this distortive nature of shame is what prevents many women from coming forward with a report.

Even in cases where shame seems to be an appropriate response, it often still causes damage. At the Festival of Dangerous Ideas session in 2022, World Without Rape, panellist and journalist Jess Hill described an advertisement she once saw:

“…a group of male friends call out their mate who was talking to his wife aggressively on the phone. The way in which they called him out came from a place of shame, and then the men went back to having their beers like nothing happened.” Hill encourages us to think: where will the man in the ad take his shame with him at the end of the night? It will likely go home with him, perpetuating a cycle of violence.

Likewise, co-panellist and historian Joanna Bourke noted something similar: “rapists have extremely high levels of abuse and drug addictions because they actually do feel shame”. Neither of these situations seem ‘normatively distorted’ in Nussbaum’s sense, and yet they still seem to go wrong. Bourke and other panellists suggested that what is happening here is not necessarily a failing of shame, but a failing of the social processes surrounding it.

Shame opens us to vulnerability, but to sit with vulnerability and reflect requires us to be open to very difficult conversations.

If the social framework for these conversations isn’t set up, we end up with unjust shame or just shame that, unsupported, still manifests itself ultimately in further destruction.

However, this nuance is far from intuitive. While people are saddened by the idea of victims feeling shame, they often feel righteous in their assertions that perpetrators of crimes or transgressors of socials norms should feel shame, and that their lack of shame is something that causes the shameful behaviour in the first place.

Shame certainly has potential to be a force for good if it reminds us of moral standards, or in trying to avoid it we are motivated to abide by moral standards, but it’s important to retain a level of awareness that shame alone is often not enough to define and maintain the ethical playing field.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Explainer

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Gender

LISTEN

Society + Culture

Festival of Dangerous Ideas (FODI)

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships, Society + Culture

Extending the education pathway

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships, Society + Culture

Stop giving air to bullies for clicks

Losing the thread: How social media shapes us

Losing the thread: How social media shapes us

Opinion + AnalysisSociety + CultureRelationships

BY Daniel Finlay The Ethics Centre 4 MAR 2024

“I feel like I invited two friend groups to the same party.”

The slowly spiralling mess that is Twitter received another beating last year in the form of a rival platform announcement: Threads. And although this was a potentially exciting development for all the scorned tweeters out there, amid the hype, noise and hubbub of this new platform I noticed something interesting.

Some people weren’t sure how to act.

Twitter has long been associated with performative behaviour of many kinds (as well as genuine activism and journalism of many kinds). Influencers, comedians, politicians and every aspiring Joe Schmoe adopt personas that often amount to some combination of sarcastic, cynical, snarky and bluntly relatable.

Now, you would think that people migrating to a rival app with ostensibly the same function would just port these personas over. And you would be right, except for the hiccup of Threads being tied directly to Instagram accounts.

Why does this matter? As many users have pointed out, the kinds of things people say and do on Twitter and Instagram are markedly different, partially because of the different audiences and partially because of the different medium focus (visual versus textual). As a result, some people are struggling with the concept of having family and friends viewing their Twitter-selves, so to speak.

These posts can of course be taken with a grain of salt. Most people aren’t truly uncomfortable with recreating their Twitter identities on Threads. In fact, somewhat ironically, reinforcing their group identity as “(ex-)Twitter users” is the underlying function of these posts – signalling to other tweeters that “Hey, I’m one of you”.

The incongruity between Instagram and Twitter personas or expression has been pointed out by some others in varying depth and is something you might have noticed yourself if you spend much of your free time on either platform. In short, Instagram is mostly a polished, curated, image-first representation of ourselves, whereas Twitter is mostly a stream-of-consciousness conversation mill (which lends itself to more polarising debate). There are plenty of overlapping users, but the way they appear on each platform is often vastly different.

With this in mind, I’ve been thinking: How do our online identities reflect on us? How do these identities shape how we use other platforms? Do social media personas reflect a type of code-switching or self-monitoring, or are they just another way of pandering to the masses?

What does it say about us when we don’t share certain aspects of ourselves with certain people?

This apparent segmentation of our personality isn’t new or unique to social media. I’m sure you can recall a moment of hesitation or confusion when introducing family to friends, or childhood friends to hobby friends, or work friends to close friends. It’s a feeling that normally stems from having to confront the (sometimes subtle) ways that we change the way we speak and act and are around different groups of people.

Maybe you’re a bit more reserved around colleagues, or more comical around acquaintances, or riskier with old friends. Whatever it is, having these worlds collide can get you questioning which “you” is really you.

There isn’t usually an easy answer to that, either. Identity is a slippery thing that philosophers and psychologists and sociologists have been wrangling for a long time. One basic idea is that humans are complex, and we can’t be expected to be able to communicate or display all the elements of our psyche to every person in our lives in the same ways. While that’s a tempting narrative, it’s important to be aware of the difference between adapting and pandering.

Adapting is something we all do to various degrees.

In psychology, it’s called self-monitoring – modifying our behaviours in response to our environment or company. This can be as simple as not swearing in front of family or speaking more formally at work. Sometimes adapting can even feel like a necessity. People on the autism spectrum often “mask” their symptoms and behaviours by supressing them and/or mimicking neurotypical behaviours to fit in or avoid confrontation.

In lots of ways, social media has enhanced our ability to adapt. The way we appear online can be something highly crafted, but this is where we can sometimes run into the issue of pandering. In this context, by pandering I mean inauthentically expressing ourselves for some kind of personal gain. The key issue here is authenticity.

As Dr Tim Dean said in an earlier article in this series, “you can’t truly understand who someone is without also understanding all the groups to which they belong”. In many ways, social media platforms constitute (and indicate further) groups to which we belong, each with their own styles, tones, audiences, expectations and subcultures. But it is this very scaffolding that can cause people to pander to their in-groups, whether it simply be to fit in, or in search of power, fame or money.

I want to stress that even pandering in and of itself isn’t necessarily unethical. Sometimes pandering is something we need to do; sometimes it’s meaningless or harmless. However, sometimes it amounts to a violation of our own values. Do we really want to be the kinds of people who go against our principles for the sake of fitting in?

That’s what struck me when I read all of the confused messaging on the release of Threads. It’s one thing to not value authenticity very highly; it’s another to disvalue it completely by acting in ways that oppose our core values and principles. Sometimes social media can blur these lines. When we engage in things like mindless dogpiling or reposting uncited/unchecked information, we’re often acting in ways we wouldn’t act elsewhere without realising it, and that’s worth reflecting on.

It’s certainly something that I’ve noticed myself reflecting on since then. For some, our online personas can be an outlet for aspects of our personality that we don’t feel welcome expressing elsewhere. But for others, the ease with which social media allows us to craft the way we present poses a challenge to our sense of identity.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Explainer

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Dignity

Big thinker

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Big Thinker: Temple Grandin

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

We shouldn’t assume bad intent from those we disagree with

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Would you kill one to save five? How ethical dilemmas strengthen our moral muscle

BY Daniel Finlay

Daniel is a philosopher, writer and editor. He works at The Ethics Centre as Youth Engagement Coordinator, supporting and developing the futures of young Australians through exposure to ethics.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Blindness and seeing

‘Anyone who says that life matters less to animals than it does to us has not held in his hands an animal fighting for its life’. Elizabeth Costello, from J. M. Coetzee’s The Lives of Animals

‘Don’t think, but look!’ – Ludwig Wittgenstein, Philosophical Investigations

Philosophical debates about animal welfare can appear abstruse. Much scholarly ink has been spilt over whether animals possess the requisite features—an interest in the future, an ability to suffer, a mind—that would ground our duties towards them. I wonder, however, if theoretical arguments of this sort really do justice to the issue at hand, which seems not so much a matter of moral disagreement as a radical difference in ways of seeing. What for the animal rights activist is a mechanised holocaust of unconscionable scale is for the meat-eater an institution that betters their well-being. The most pressing issue, as I see it, is not whether animals have rights, but whether we are able to see them at all as fellow creatures inhabiting the same world and sharing our vulnerabilities.

In J.M. Coetzee’s novella, The Lives of Animals, the elderly novelist Elizabeth Costello is invited to give an address at Appleton College. Her chosen theme being on our treatment of animals, she prefaces her lecture by exhibiting what she calls a ‘wound’: a scar from being exposed to the haunting nature of our treatment of animals, of being surrounded by well-meaning human beings who remain bewildering blind to the atrocities she alone perceives.

Throughout the novella, Costello discusses and answers arguments but never as the theorising philosopher. When an opponent suggests that life and death cannot be to animals, who lack a sense of identity, what it is to us, she responds by the line quoted in the epigraph of this piece, that whoever would say so has not held in their hands an animal fighting for its life, a line which I find stunning. Never mind our favoured theory of the mind, can’t you see it is suffering?

Here is an affirmation of our exposure to the suffering of animals, an involuntary confrontation, before which what is called upon is not our reason but an anguished response that is a testament to our humanity. Costello is not a vegetarian out of moral convictions; instead, she insists ‘“it comes out of a desire to save my soul”’– out of a vivid awareness of her exposure. There is a sense in which any attempt at philosophising inevitably ends up deflecting us away from that immediate reality, the animals in our hands.

Costello provocatively compares the meat industry to the Holocaust. Her point, I take it, is linked to what Stanley Cavell has called ‘soul blindness’: a failure to see another human as human. Primo Levi, in his Survival in Auschwitz, vividly recalls the look from a Nazi examiner, which ‘came as if across the glass window of an aquarium between two beings who live in different worlds’. What we find so accursed about the examiner, I think, is not his false moral beliefs – rather, there seems to us a critical defect in their sensibility, a blindness to humanity which stings.

We find another illustration of ‘soul blindness’ in the film Blade Runner, which imagines a world where human-like ‘replicants’ are mass-produced and enslaved, and those who escape are tracked down.

At first pass, we might see Blade Runner as a film noir exploring the boundary between humans and intelligent replicants; yet when we realise that the replicants, who can think, feel, and interact exactly like humans, are perhaps denied moral status only by the technical stipulation that ‘humans’ are those with a specific biology, the film takes on a more sinister meaning. In particular, it might shock us with how easily we become blinded to the living humanity of another, when some abstract, in hindsight irrelevant pieces of information are introduced – ‘They do not have DNA’; or ‘They are a Jew’.

Animal rights activists often point to the difference in our treatment of pets and those whom we eat for meat; but rather than dismissing it as a sign of our irrationality, if not hypocrisy, the datum ought to be probed further. What is different is a way of seeing: the pets are companions, family members, whom we acknowledge as fellow creatures, while the pigs are just food.

Many times I have felt deeply perturbed, flipping through an illustrated children’s book, when I saw the image of a smiling pig with just the right amount of anthropomorphism that it looks uncanny. Those are eyes which I do not dare meet. The knowledge inside those images, that a pig is also a being capable of feelings and suffering, is knowledge too terrible to bear – we have been raised to suppress it. If he could explain the examiner’s look, Levi tells us, he would also have explained the insanity of the Third Reich. We might make a parallel statement about animals: if one could explain the way we look upon animals as mere food and not living creatures like us, then one would also have explained our treatment of animals.

Here is what I think the three cases – our treatment of animals, the Holocaust, and the enslavement of replicants – have in common: drawing on an idea of Simone Weil, they are issues on a separate moral plane from those to be afforded intellectualised debate. We could argue about why slavery is wrong, but we should not argue over if it is wrong. I am not saying that we should give up persuasion and begin accusing each other of the monstrosity of eating meat; rather, what I claim is that abstract disputes over rights and permissions seriously misrepresent the moral terrain.

Levi remarks that one of the things the camp taught him was ‘how vain is the myth of original equality among men’. What use is there of a theory of human rights if the abuser does not see you as a human at all? This is why Costello appeals not to philosophy, but to imagination and poetry: a chasm of sensibility can only be bridged by changes in the way of seeing. And why should our response to animals be out of a sense of duty? Often, the more humane response may well be one out of kindness and a sense of fellowship.

In today’s world, our blindness to each other’s humanity is unfortunately still all too prevalent – the images that emerge from recent conflicts confirm it. One could say, however, that our blindness to the suffering of animals is just as distressing. What is most frightening is perhaps not that we come up with the wrong moral beliefs, but that we lose the ability to see animals, and other humans, as fellow beings who are like us.

‘Blindness and seeing‘ by David He is one of the Highly Commended essays in our Young Writers’ Competition. Find out more about the competition here.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Breaking news: Why it’s OK to tune out of the news

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Ethics of Care

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships, Society + Culture

Stop giving air to bullies for clicks

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

The truths COVID revealed about consumerism

BY David He

David is a pure mathematics honours student at the University of Sydney, having completed double majors in mathematics and philosophy there. In his free time he likes to read and play Go, a board game. He aspires to become a mathematician and/or a writer someday.

What we owe our friends

Friendships are confusing. I’ve often found myself feeling that something is missing in my friendships — a sentiment that seems to be shared, yet rarely addressed. One that’s echoed in the paradoxical 21st century correlation between our ever growing hyper-connectivity and reports declaring a loneliness epidemic. One that’s felt in parties full of friends that you can’t wait to leave.

Like many of us, I have learnt that this is partly down to the culturally accepted life cycle of friendships. I never felt lacking when I was younger: I had deep bonds with childhood friends, who I did the wild adventures of youth with, but also spent infinite hours in pyjamas with, drinking tea and learning how to build loving relationships. But as plans with friends became plans reserved for partners, and time became stretched by work and adulting, I slowly processed the idea that their importance will silently decline as you age.

But I’ve also had a nagging sense that something more unspeakable affects the quality of our friendships. Something resigning friendships to the trivial and fun, and shaming a desire for deeper bonds.

It wasn’t until I read The End of Love by Eva Illouz that I felt able to articulate what this is, and why it is so hard to talk about feeling disappointed by friends. Through an extensive analysis of social relations under consumer capitalism, she makes a simple central point: freedom, the value that trumps all for western society, requires the dissolving of expectations in human relationships.

In an age of abundance, the defining feature of 21st century liberal social relations is the practice of non-commitment. Personal autonomy is the main cultural story that guides our lives. We’re driven by the search for personal success and pleasure. To realise this, we must be free to choose our own relations at will, and therefore also leave them at will. We make responsible choices to avoid things that might impinge on our personal growth, including that relationship stopping you from moving, or that friend whose chaotic period has gone on a bit too long.

So we have relaxed our mutual expectations on each other — almost to the point of having none at all.

The value of freedom has transcended left and right politics, and is accepted as an untouchable pillar of morality. Self empowerment has been the prerogative of many left wing progressives as much as neoliberal free-marketers. It’s found in the language of capitalist growth and competition, but also in the language of pop-psychology that tells us to set boundaries and cut people out of our life who don’t ‘serve’ us or bring us pleasure.

But Illouz reopens this debate that has been closed since liberal philosophy claimed hegemony over morality, asking us ‘does freedom jeopardize the possibility of forming meaningful and binding bonds?’

I think about the hollowed expectations we have of our friends. Flaking is normal. We tend to leave maximum space to opt out of plans whenever and minimum pressure to commit, generally resigning ourselves to polite understanding if people cancel even when it hurts, knowing that we often do the same. Asking for support is also done cautiously to avoid overstepping, burdening or offloading, even in our greatest moments of need.

And then there are the ways in which many friendships silently end. When I was 22, after an ongoing period of difficulty where we both hurt each other, one of my closest friends sent me a facebook message telling me she never wanted to speak again. Despite my ongoing attempts in the coming years to reconcile, she stuck to this conviction, and I have only seen her in passing at parties since then. A long term friendship was suddenly gone with minimal discussion, and the invisible rulebook of friendship said that this was fine.

Friendships which diverge from the comfortable space of convenience, ease, and fun can quickly become threats to our personal growth. Consumers at our core, we are well practiced in disposing of things that don’t benefit us anymore and less well practiced at fixing broken things. Systems make their way into our bodies and minds, and the system we live in is one built on endless desire and access to the new. In such a society we owe our friends nothing. We might choose to owe them, but we don’t have to.

We sense this fragility. We know on some level that if friends can exit at any moment without consequence, we must persuade them to stay. Friendship mimics a market in which you must compete to survive, and we are all painfully aware of the limits of what our commodified selves can offer. In this knowledge, socialising often becomes fraught as we feel this pressure to bring something positive to the room that wins us a good review after. Those who lack status built by resource, health, and charisma struggle more, their exclusion a reality made invisible by the language of choice.

The psychologist Sanah Ashan tells us that falling apart is a birthright. For us to feel connected, our relationships must embrace discomfort. Friendships shouldn’t be intolerant of prolonged messiness. We must instead embrace the misery and the insanity; coming together in these times not running away. Intimate bonds are difficult.

We live in an age where traditional sites of belonging have been diminished — religion, community, even family and romantic relationships are more uncertain than they have ever been. Public care structures have been decimated to the point of dysfunction. More and more of us find that we have to make our own communities of care and belonging, found in the friends we make ourselves.

Yet conversation about building these communities is often superficial when we don’t know how to be close to each other. We long for community, but often turn to therapists in our times of need.

Re-envisioning how we build strong and enduring bonds requires us to open a conversation that asks bigger questions than how we balance time between work, relationships, and friends. It requires us to question the promises of fulfillment from personal freedom alone. Wendy Brown reminds us that achieving, and even envisioning personal freedom is far from straightforward:

‘historically, semiotically, and culturally protean, as well as politically elusive, freedom has shown itself to be easily appropriated in liberal regimes for the most cynical and unemancipatory political ends.’

The left has been good at unpicking how the appeals to freedom have created unjust markets and vast inequalities, but we haven’t openly discussed the effects of this in the world of emotions and relationships. The practice of non-commitment in our relationship building mimics the rise of the gig economy, precarious work, and the breakdown of worker solidarity. Free market economics sacrificed security and equality in the name of unfettered growth. We must ask whether the same might be happening in our social relations.

We all yearn for connection, yet our disdain for responsibility in the name of freedom keeps us apart. But we owe our friends something different to the transactional relationships of the capitalist workplace; we owe them love and time regardless of the value they offer us.

‘What we owe our friends‘ by Zoe Timimi is the winning essay in our Young Writers’ Competition (18-30 age category). Find out more about the competition here.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

Nothing But A Brain: The Philosophy Of The Matrix: Resurrections

Big thinker

Relationships

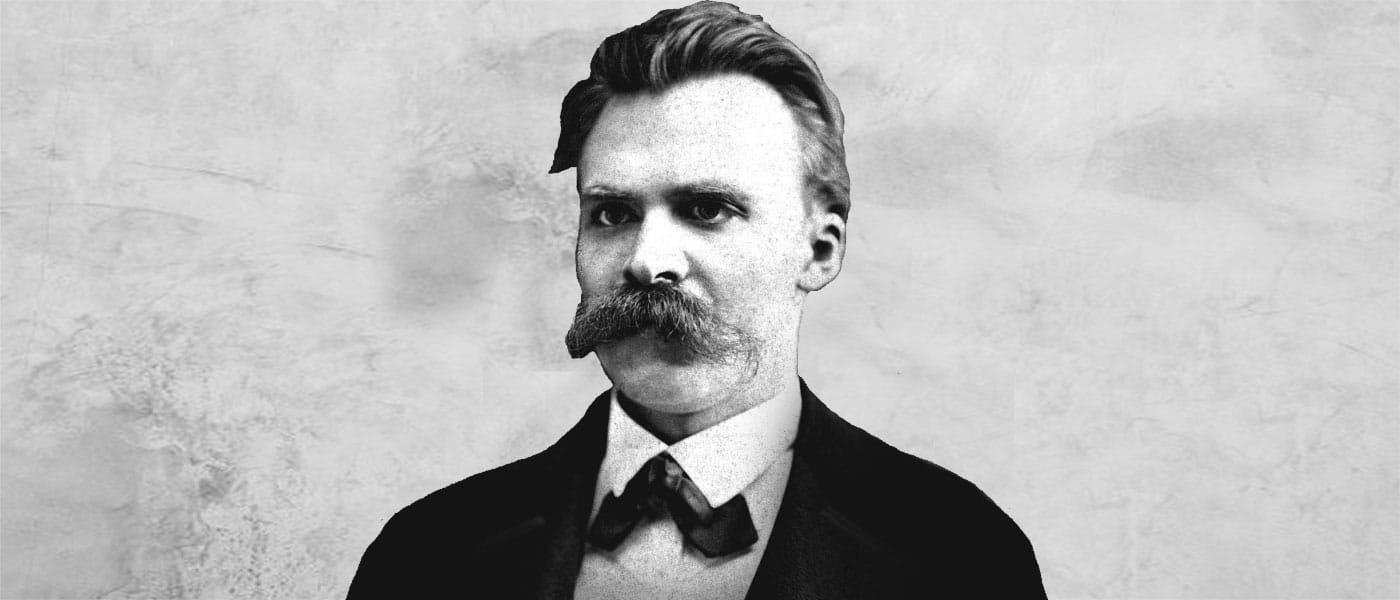

Big Thinker: Friedrich Nietzsche

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships, Society + Culture

Renewing the culture of cricket

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

A guide to ethical gift giving (without giving to charity)

BY Zoe Timimi

Zoe is passionate about all things mental health, community and relationships. She holds a BA in Sociology and an MA International Political Economy, but has spent the last few years working as a freelancer in various TV development and writing roles.

Our desire for reality: What OnlyFans says about sexual fantasy

Our desire for reality: What OnlyFans says about sexual fantasy

Opinion + AnalysisRelationships

BY Jack Ryan 24 JAN 2024

Despite being a generation overwhelmed with technological means to fulfil their fantasies, today’s youth desire sexual reality. The rapid uptake of OnlyFans embodies a paradoxical desire to escape an increasingly grim sexual reality through indulging in consumption of ‘reality’ pornography. But how ‘real’ can pornography ever be, and does it represent an entrenchment of the patriarchal sexualisation of women?

Pornhub’s 2022 annual report demonstrated that the fastest growing trend for 2022 was ‘reality’ – increasing viewership by a total of 169%. Simultaneously, viewership of the ‘amateur’ category declined roughly 20%, leading the researchers to note ‘visitors are still seeking a real homemade porn experience’ – the guise of amateur is not enough. In Australia specifically, the two top trending searches for 2023 were ‘sharing a bed’ (+%600) and ‘therapy’ (+%540), a far cry from what would typically be associated with pornographic content.

Society’s previous relationship with pornography was one of explicit fantasy; a consumption of unrealistic bodies in improbable scenarios conducting inconceivable acts. Aiding this was explicit acceptance of the disconnect present, lusting for the physical specifically because it was not also attempting to be a fill-in for true connection. In other words, the fantasy being indulged in was the removal of emotional or social connections from sex – it was sex for the sake of sex.

A national survey recently highlighted that those aged 18-24 age were most likely to experience loneliness, with 22% of this bracket stating they are either constantly or often lonely. Such trends are replicated globally in the general decrease of sexual activity experienced by young people, particularly in Western countries. But it is feasible to broach this deficiency through faux realities?

OnlyFans is fast becoming a behemoth of pornographic facilitation with users paying more than $5 billion to creators in 2022. Not only is spending up, but content creators have grown by nearly 50% in the past year. OnlyFans’s explosive growth comes from linking creators to consumers in a way porn never did. Individuals are no longer the perverts behind a screen, instead they have become ‘fans’ that are afforded technological involvement with the objects of their sexual desire.

Here the pornographic trope of ‘the girl next door’, previously relegated to a fantasy, has now become a form of sexualised reality and should be taken literally – the girl next door might exist. This merging of sexual fantasy into the real world suggests that today’s youth want more realistic sexual content, and greater interpersonal connection, due to a lack in real life. Porn actors are no longer 2D figures who appear only as sexualised objects for my fantasy to manipulate, the rise of technology and social media means we connect with adult content creators as holistic beings who can perceive us as a human (or a fan) – not simply as an anonymous click or view.

Fantasy for sale

While traditional porn inserted fantasy into reality by imagining all the ways certain sexual desires were unattainable, OnlyFans is seeing a reversal by injecting reality into fantasy by imagining all the ways in which sexual desires may be attainable.

What should be obvious is that escape toward this ‘reality’ is anything but – reality, as a pornographic concept, has now become a commodity. Platforms such as Meta pioneered the sale of ‘reality’ as a commodity, initially through social media which promised global connection and more recently with openly ‘virtual’ realities as places of escape (for a price).

Just as it was once assumed constant connection through Facebook would alleviate loneliness, which it is now proven to increase, society needs to be careful of establishing a feedback loop in sexual consumption. Here the phenomena of ‘parasocial relationships’, where effort and interaction is one-sided, operates in full effect; while a user can ‘interact’ with their favourite explicit content creator. The purpose of this interaction is only as a profit mechanism, there is no symbiotic social relationship taking place.

OnlyFans in essence offers a new commodity of sexual ‘reality’ which, just as social media has, proports to sell us connection to reality, while simply creating a new grey space of pseudo-connection.

In turn, the more reliant society is on technology to fulfil our needs, the less-equipped we are to find such things organically – an increasing trend of abstinence being evidence to the point.

Political-economy of sexual reality

This sexualisation of reality brings with it a major challenge to the sex-positive view of feminism. We should take seriously that the liberalisation of sex and sexuality in the 21st century has positively influenced the lives of women by offering space and safety for progressive practices. Yet, it cannot be ignored that the financial prosperity that OnlyFans affords (largely female) creators comes at the cost of internalising a core patriarchal notion; the sexual objectification of women’s bodies.

The sex positive view typically argues that patriarchy was a limiting factor on sexuality and is instead in favour of removing societal stigma and shame surrounding pornography. Here the trend of reality-centric porn would be supported to further liberate both men and women from sexual restriction – even if the establishment of unhealthy norms which propagate the sexualisation of patriarchal interests through porn continues. Here issues of subjugation, domination and sexualisation must necessarily be supported, providing an indication as to why younger generations are turning away from the positivist view.

In OnlyFans’s case, it may establish a sexual panopticon where women perceive self-sexualisation as liberating, not realising that the patriarchal logic of objectifying bodies has now become self-imposed and self-regulating as women free men of this task. The danger being that, if the trend of sexualising reality continues, what was previously relegated to closed-door fantasies is brought into the real world. Tangibly this could mean that women now find themselves more sexualised as pornographic content increasingly blurs lines between public and private thoughts or actions.

A springboard

As sexual lives become further digitally enmeshed (what will the Metaverse mean for sexting?) there is need to reflect on how our desires are impacted. Desire for reality should reflect an underlying lack thereof as well as the pseudo-reality technology such as OnlyFans sells us as a replacement. In a world of fast fashion, fast food, and fast internet it should be pause for thought that today’s youth don’t want fast sex – they want real sex but will settle for less.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

What we owe to our pets

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Hope

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

5 stars: The age of surveillance and scrutiny

Big thinker

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships