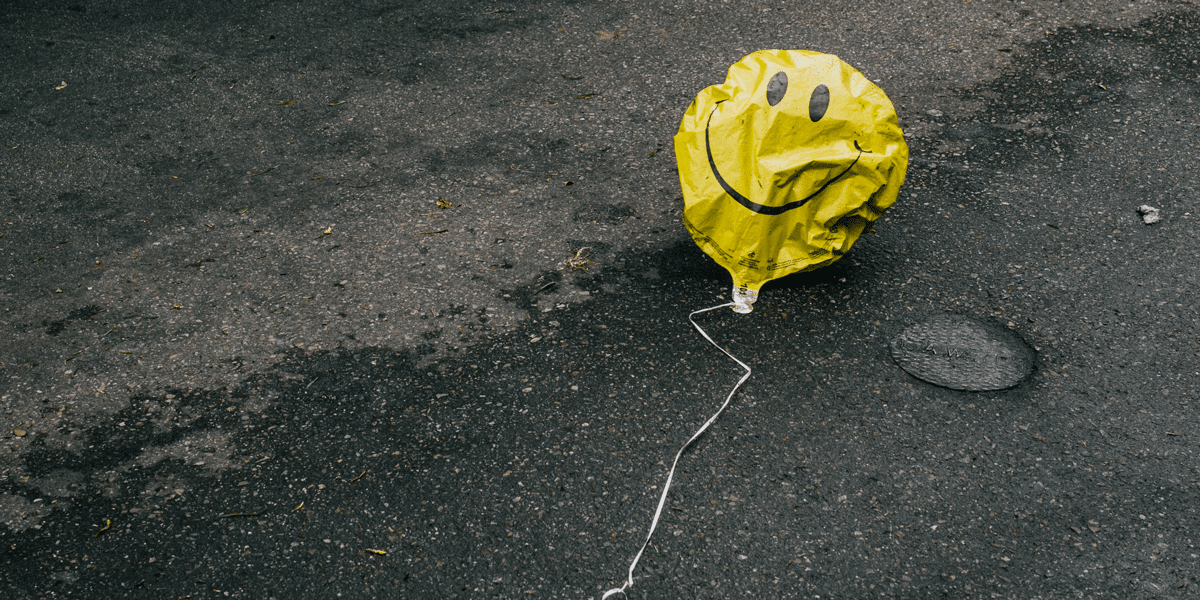

Stoicism on Tiktok promises happiness – but the ancient philosophers who came up with it had something very different in mind

Stoicism on Tiktok promises happiness – but the ancient philosophers who came up with it had something very different in mind

Opinion + AnalysisSociety + CultureRelationships

BY Matthew Duncombe 20 DEC 2023

I don’t know about you, but my TikTok is full of influencers telling me I should be a Stoic. You might know the term “stoic” as a person who goes through hardship while maintaining a steely and calm disposition, and never complains. However, a stoic is also someone who prescribes to the philosophical school of Stoicism.

Stoicism became popular in ancient Rome. Stoic TikTok exclusively draws on Roman Stoicism, mainly Epictetus (a formerly enslaved person), Seneca (a fabulously wealthy and self-aggrandizing advisor to the emperor Nero), and Marcus Aurelius (who was himself a Roman emperor).

But the school goes back much further to ancient Athens, where Stoicism was founded around 300BCE by Zeno of Citium. After Zeno, Stoicism flourished in Athens, especially under Chrysippus, known as the second founder of Stoicism.

On TikTok, you’ll see people saying that Stoicism is a great way to lead a happy and productive life. I’m a professional philosopher who specialises in ancient Greek philosophy – and it’s great, if somewhat surprising, to see how popular Stoicism has become over the last ten years. But as a philosopher, I’m not a Stoic – and Stoic TikTok gets quite a lot wrong about this way of thinking.

Despite what you see on TikTok, Stoicism was a dry, technical, ivory tower philosophy. Its ideas around happiness and productivity diverge quite a bit from what modern people consider these to be. Traditionally, it was divided into three branches: ethics, physics, and logic – much of which TikTok’s Stoic preachers don’t get quite right.

Logic

Distinctively, the Stoics emphasised logic, comparing it to the shell of an egg or the bones and sinews of a body, because logic protects (like a shell), supports (like bones) and connects (like sinews) our beliefs and knowledge. In fact, the Stoics developed a systematic logical theory which, through various historical twists and turns, inspired 20th-century logic and hence theoretical computer science.

The Stoics took logic seriously because it was needed for knowledge. For the Stoics, to know something – including how to live well – was to understand it so totally that you could defend your view against any degree of argumentative scrutiny, against any opponent. In other words, they used logic to win a sort of philosophical Hunger Games.

But Stoic TikTok isn’t really interested in a deep, rich and logically defensible knowledge of the world and our place in it. In so far as Stoic TikTok is interested in knowledge, it implies that you can get knowledge by simply reading quotations of famous Stoics or practising certain mental exercises, such as meditating on death.

Physics

Stoic TikTok also ignores Stoic physics – the principles that Stoics used to explain the natural processes in the universe. For the Stoics, everything that exists, including your soul and God, is a body. God, in fact, is “mixed with matter, pervading all of it and so shaping it, structuring it and making it into the world”, as the critic Alexander of Aphrodisias told us in the early third century.

The Stoics argued that, since God is rational and active, this makes everything that exists in the world rational and organised for the best. You are part of this rational universe so, if bad things happen to you, it would be irrational to complain – as if your foot complained about getting muddy.

This idea of a rational universe is popular with Stoic TikTok, and can be seen in posts telling followers to “love their fate”. They suggest that true happiness comes from accepting anything that happens.

But does loving your fate in a truly Stoic sense achieve the sort of productivity and happiness most people want? I think not.

Ethics

Which brings us to Stoic ethics. While Stoic TikTok promises productivity and happiness, it’s unlikely you’ll achieve the levels of productivity and happiness you actually desire if you go by what Stoics believed these to be.

Happiness, for a Stoic, was a matter of having virtues and lacking vices. Everything else – including health, wealth and status – were “indifferents”, because they made no difference to your virtue, and so to your happiness.

So, even if the self-helpy advice of Stoic TikTok could make you more productive, being more productive won’t make you be happier, according to Stoic philosophy. At best, you’ll acquire health, wealth or status, but those things are indifferent to your happiness.

There is, of course, something hypocritical about Seneca arguing that wealth is indifferent while being one of the richest men in Rome; or Marcus Aurelius saying that power is indifferent while being emperor.

It is rational to prefer to be healthy rather than ill, rich rather than poor, powerful rather than oppressed. In fact, there was nuanced ancient debate in which the Stoics tried to find a middle way between a view where health, money and power are simply good, and a view where they are totally irrelevant to living a good life.

Chrysippus tried to steer this course by saying that while health, wealth and power are indifferent, how you use them is not. If I use power intemperately or wealth to indulge my most disgusting appetites, I will not be virtuous or happy. Personally, I don’t think the Stoic philosophy will ultimately solve this problem of whether health, wealth and power are totally indifferent to happiness, but it is an open question.

I’ve not touched here on the more sinister aspects of Stoicism on the internet, discussed in Donna Zuckerberg’s Not All Dead White Men. Rather, I’ve tried to point out what Stoic TikTok misses, because I hope people dive deeper into Stoic philosophy. A great place to start is Tad Brennan’s The Stoic Life.

Stoicism is a rich, fascinating and sophisticated philosophical tradition. But, if you’re looking for happiness and productivity in more modern terms, the Stoics might not have the answer.

This article was originally published by The Conversation. Image by Bradley Weber.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Explainer

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Values

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Freedom and disagreement: How we move forward

READ

Society + Culture

6 dangerous ideas from FODI 2024

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

The #MeToo debate – recommended reads

BY Matthew Duncombe

I am an Associate Professor, University of Nottingham, working mainly on Plato, Aristotle, the Stoics and ancient sceptics. I often write about ancient logical and metaphysical ideas, but I have a broad range of philosophical interests, including ethics, games, fate, paradoxes and mental health, especially ancient perspectives on these.

What does love look like? The genocidal “romance” of Killers of the Flower Moon

What does love look like? The genocidal “romance” of Killers of the Flower Moon

Opinion + AnalysisRelationshipsSociety + Culture

BY Joseph Earp 19 DEC 2023

Killers of the Flower Moon, the newest film by Martin Scorsese, starts with a terrible, distorted version of the romantic “meet-cute.”

Ernest Burkhart (played with leery relish by Leonardo DiCaprio) romances Molly Kyle (Lily Gladstone). He’s a driver; she needs to get around the place. Throwing knowing looks over his shoulder as he spins his wheel, he flirts with her, and though she is initially suspicious, eventually she succumbs to his interests. A romance is born.

It is the classic “boy meets girl” story – or at least, it would be, if we didn’t already know the real reason driving Ernest’s romantic designs. He has been put up to this meeting by “King” Hale (Robert DeNiro), his calculating and murderous Uncle, who is seeking to redirect the fortunes of the Osage tribe of which Molly is a member. Though he projects an image as a pillar of the community, King is the centre of a string of murders – and Ernest is recruited as his budding killer-to-be, with Molly as a target.

The tension at the heart of Killers of the Flower Moon lies in Ernest’s dual role as Molly’s wife and her poisoner. Though Ernest is the film’s main character, we are given little in the way of his interior life. Instead, we understand the man through his actions, which are, increasingly, in direct conflict. Ernest acts like he loves Molly, and the children they have together; he weeps when one dies. He also injects her daily with a poison. When, in the film’s climax, the pair are reunited, he almost collapses into her arms. Nobody outright asks Ernest if he loves Molly, but they ask similar questions, and he responds in the full-throated affirmative. She is his wife, and at least some of the time, he treats her as such.

So, do we want to accept this kind of attachment – murderous, openly destructive – as a form of love? Or would doing so fundamentally taint the concept?

Love as a blinding force

The ethical value of love has long been debated by philosophers. Plato and Socrates both saw love as a fundamentally morally valuable emotion – one which expands our sense of the world’s beauty and possibility, and motivates us to do better. Indeed, according to this view of love, romance is the foundation of ethical action.

It’s a way of teaching us of the importance of other people, an escape from selfish solipsism that draws out into the world.

But love – as the mere existence of the term “crime of passion” proves – does not always lead us down virtuous paths. Any romance also has the capability of reducing ethical scope, not expanding it. Arthur Schopenhauer, the notorious pessimist, saw love as an essential “illusion” that consumes people utterly. He described it as little more than the desire to procreate, over which the fiction of romance gets written. On this view, love creates a lopsided sense of ethical value, transforming the world down to a single point – the love object. This in turn breeds jealousy; possession; and, Schopenhauer said, frequently madness.

What makes Ernest’s “love” distinct, however, is that he doesn’t seem to experience the usual ethical pitfalls of romance. He’s not jealous of Molly. He doesn’t act as though he wants to possess her – at least not in the normal sense. Nor does he, in the traditional sense, go mad. Instead he acts to destroy her, an essentially self-negating series of actions where the one he prizes the most is also the one he seeks to snuff out.

Love in and of itself

Perhaps ironically, given his reputation as a cold, difficult and abstract philosopher, it is Immanuel Kant who provides the solution to the puzzle of Ernest’s love. Taken as a whole, Kant is paradoxical on the nature of love – he once dismissed it as a “feeling”, and wrote that “a duty to love is an absurdity.”

But, importantly, Kant did believe we should love one another. And more than that, this was a duty to love another “in and of itself.” One of Kant’s key ethical positions is the idea that using another – treating them like a mere “means” – is wrong. Instead, he believed that we should view other people as an “ends”. Kant believed that value did not exist outside human beings – that we create value – and that we should view all others, including those we love, as the source of value in the world. We respect and love others, he thought, because we see them not for what they can do for us, but for what they are; what they value and what they care about.

Ernest does not do this. Both of the ways that he treats Molly – doting on her and poisoning her – are for his own benefit. He has turned her into a mere object, a machine for love and money. She gives him children, and her death will give him riches and success. When he falls into her arms and embraces her, he is embracing not the whole Molly – the full, rich person, a source of value in the world – but only the parts of her that help him.

In this way, Ernest’s broken form of love serves as a warning to the rest of us.

When we say we love someone, we should direct that emotion to all who they are. Not choosing the parts we like, or the parts that service us. But the difficult parts; the awkward parts; the fears and the pains as well as the highs.

A lover’s eyes should always be open, after all.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Struggling with an ethical decision? Here are a few tips

Opinion + Analysis

Climate + Environment, Relationships

Care is a relationship: Exploring climate distress and what it means for place, self and community

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics explainer: Nihilism

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Plato’s Cave

BY Joseph Earp

Joseph Earp is a poet, journalist and philosophy student. He is currently undertaking his PhD at the University of Sydney, studying the work of David Hume.

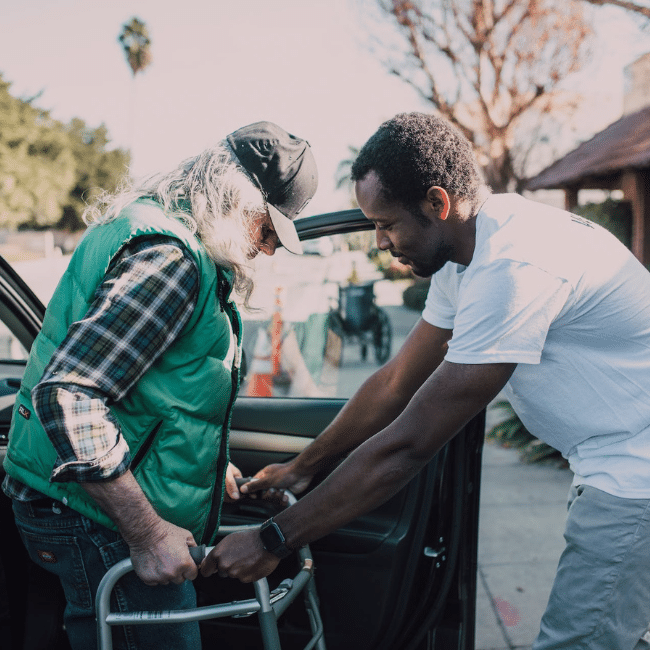

Ethics Explainer: Altruism

Amelia notices her elderly neighbour struggling with their shopping and lends them a hand. Mo decides to start volunteering for a local animal shelter after seeing a ‘help wanted’ ad. Alexis has been donating blood twice a year since they heard it was in such short supply.

These are all examples, of behaviours that put the well-being of others first – otherwise known as altruism.

Altruism is a principle and practice that concerns the motivation and desire to positively affect another being for their own sake. Amelia’s act is altruistic because she wishes to alleviate some suffering from her neighbour, Mo’s because he wishes to do the same for the animals and shelter workers, and Alexis’ because they wish to do the same to dozens of strangers.

Crucially, motivation is what is key in altruism.

If Alexis only donates blood because they really want the free food, then they’re not acting altruistically. Even though the blood is still being donated, even though lives are still being saved, even though the act itself is still good. If their motivation comes from self-interest alone, then the act lacks the other-directedness or selflessness of altruism. Likewise, if Mo’s motivation actually comes from wanting to look good to his partner, or if Amelia’s motivation comes from wanting to be put in her neighbour’s will, their actions are no longer altruistic.

This is because altruism is characterised as the opposite of selfishness. Rather than prioritising themself, the altruist will be concerned with the well-being of others. However, actions do remain altruistic even if there are mixed motives.

Consider Amelia again. She might truly care for her elderly neighbour. Maybe it’s even a relative or a good family friend. Nevertheless, part of her motivation for helping might also be the potential to gain an inheritance. While this self-interest seems at odds with altruism, so long as her altruistic motive (genuine care and compassion) also remains then the act can still be considered altruistic, though it is sometimes referred to as “weak” altruism.

Altruism can (and should) also be understood separately from self-sacrifice. Altruism needn’t be self-sacrificial, though it is often thought of in that way. Altruistic behaviours can often involve little or no effort and still benefit others, like someone giving away their concert ticket because they can no longer attend.

How much is enough?

There is a general idea that everyone should be altruistic in some ways at some times; though it’s unclear to what extent this is a moral responsibility.

Aristotle, in his discussions of eudaimonia, speaks of loving others for their own sake. So, it could be argued that in pursuit of eudaimonia, we have a responsibility to be altruistic at least to the extent that we embody the virtues of care and compassion.

Another more common idea is the Golden Rule: treat others as you would like to be treated. Although this maxim, or variations of it, is often related to Christianity, it actually dates at least as far back as Ancient Egypt and has arisen in countless different societies and cultures throughout history. While there is a hint of self-interest in the reciprocity, the Golden Rule ultimately encourages us to be altruistic by appealing to empathy.

We can find this kind of reasoning in other everyday examples as well. If someone gives up their seat for a pregnant person on a train, it’s likely that they’re being altruistic. Part of their reasoning might be similar to the Golden Rule: if they were pregnant, they’d want someone to give up a seat for them to rest.

Common altruistic acts often occur because, consciously or unconsciously, we empathise with the position of others.

Effective Altruism

So far, we have been describing altruism and some other concepts that steer us toward it. However, here is an ethical theory that has many strong things to say about our altruistic obligations and that is consequentialism (concern for the outcomes of our actions).

Given that, consequentialism can lead us to arguments that altruism is a moral obligation in many circumstances, especially when the actions are of no or little cost to us, since the outcomes are inherently positive.

For example, Australian philosopher Peter Singer has written extensively on our ethical obligations to donate to charity. He argues that most people should help others because most people are in a position where they can do a lot for significantly less fortunate people with relatively little effort. This might look different for different people – it could be donating clothes, giving to charity, volunteering, signing petitions. Whatever it is, the type of help isn’t necessarily demanding (donating clothes) and can be proportional (donating relative to your income).

One philosophical and social movement that heavily emphasises this consequentialist outlook is effective altruism, co-founded by Singer, and philosophers Toby Ord and Will MacAskill.

The effective altruist’s argument is that it’s not good enough just to be altruistic; we must also make efforts to ensure that our good deeds are as impactful as possible through evidence-based research and reasoning.

Stemming from the empirical foundation, this movement takes a seemingly radical stance on impartiality and the extent of our ethical obligations to help others. Much of this reasoning mirrors a principle outlined by Singer in his 1972 article, “Famine, Affluence and Morality”:

“If it is in our power to prevent something very bad from happening, without thereby sacrificing anything morally significant, we ought, morally, to do it.”

This seems like a reasonable statement to many people, but effective altruists argue that what follows from it is much more than our day-to-day incidental kindness. What is morally required of us is much stronger, given most people’s relative position to the world’s worst-off. For example, Toby Ord uses this kind of reasoning to encourage people to commit to donating at least 10% of their income to charity through his organisation “Giving What We Can”.

Effective altruists generally also encourage prioritising the interests of future generations and other sentient beings, like non-human animals, as well as emphasising the need to prioritise charity in efficient ways, which often means donating to causes that seem distant or removed from the individual’s own life.

While reasons for and extent of altruistic behaviour can vary, ethics tells us that it’s something we should be concerned with. Whether you’re a Platonist who values kindness, or a consequentialist who cares about the greater good, ethics encourages us to think about the role of altruism in our lives and consider when and how we can help others.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

How to have a conversation about politics without losing friends

WATCH

Relationships

Virtue ethics

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics explainer: Nihilism

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

People with dementia need to be heard – not bound and drugged

The niceness trap: Why you mustn’t be too nice

The niceness trap: Why you mustn’t be too nice

Opinion + AnalysisRelationships

BY Dr Tim Dean 15 DEC 2023

Can we be too nice? On the surface, it seems absurd to say we should put a cap on how nice we should be. But if we overdo it, we can end up shirking our other ethical obligations.

Skim the headlines or scroll through social media and you’d be forgiven for concluding that there’s a serious deficit of niceness in the world today, and if only people were a little more kind, compassionate and giving, then the world would be a much better place.

Imagine a nicer world where other drivers consistently backed off to let you merge lanes, or shrugged off your occasional failure to check a blind spot with a smile and a wave. Imagine a workplace where everybody lifted each other up, and covered for you when you needed a break. Imagine a world with more Dumbledores and fewer Snapes. Imagine a world without Karens.

Most philosophers have sought such a world by urging us to cultivate niceness. Confucious promoted the foundational virtue of ren, often translated as benevolence or humanity. Aristotle argued that the path to flourishing lay in cultivating virtues like magnanimity, generosity and patience. Christian scholars promoted temperance was a cardinal virtue. In more modern times, Peter Singer has said we ought to take the compassion we feel towards close family and friends and expand it to cover all sentient creatures, human and animal. In short: be nice.

But there’s also a catch with niceness. If we take it to excess, we can leave ourselves vulnerable to exploitation, fail in our ethical duties and even undermine the very moral foundations of our community.

This is because a world where everyone is fully trusting and selflessly giving is a ripe hunting ground for those who are willing to abuse that trust and get ahead by stepping on the backs of others.

The paradox of niceness

This phenomenon can be modelled using the popular game theoretic thought experiment, the Prisoner’s Dilemma. Imagine a situation where two bank robbers are arrested and held in separate cells, unable to communicate with each other. The police have no other witnesses, so they’re relying on the suspects’ testimony to prove the case against them. If both suspects confess, they’ll both receive a five-year sentence. If they both remain silent, then the police will only be able to charge them with a minor offense carrying a one-year sentence. However, if one of them testifies while their partner remains silent, then the dobber will be set free while their partner will go to jail for 10 years.

On the surface, it seems sensible for them both to remain silent. That would be the “nice” thing to do because it benefits them both. But there’s a twist. If one of the suspects believes that their partner will remain silent, then they have an opportunity to testify against them and get off scott-free, while their partner is thrown in the slammer. They also know that if they remain silent, then their partner will have an opportunity to dob them in. As a result, the most reasonable thing for either of them to do is dob on the other, which means they both end up with a harsher penalty than if they’d both cooperated and stayed silent.

The Prisoner’s Dilemma models a fundamental truth when it comes to social interaction: if we we’re nice, we all benefit, but there will always be a temptation to exploit the charity of others to get ahead, and in doing so, we can end up destroying the possibility of cooperation altogether.

There have been whole virtual tournaments using the Prisoner’s Dilemma to see what kinds of strategies – whether “nice” or “nasty” – will yield the best results for the agents playing the game. And it’s from these tournaments that another twist emerges.

In a single Prisoner’s Dilemma game, the nasty dobber has the upper hand, especially if their partner is nice. However, when the same agents play the game over and over, it turns out that it pays to be nice, because you’re likely to be punished in the next game if you’ve been nasty. When you add in some real-world flavour to the game, like making it so that agents can sometimes mistakenly defect when they meant to cooperate, it’s the nicer agents that come out on top.

But these simulations show that niceness has its limits. Those agents that are unconditionally nice tend to get exploited by nasty ones. However, those strategies that are conditionally nice, and that defect only to punish bad behaviour, do best of all.

Toxic niceness

Back in the real world, what this means is that it is possible to be too nice. If we’re unconditionally generous and forgiving, then we leave ourselves open to exploitation by people who will take advantage of our niceness.

It’s likely we all know someone who is a natural giver, someone whose empathy is overflowing and who goes out of their way to help everyone around them. These people are often much loved, but they can also be crushed under the weight of their own compassion, sometimes neglecting their own wellbeing, and it’s not uncommon for others to take advantage of their generosity.

Such unconditional niceness can also prevent us from punishing those who deserve it. You may have also worked for a manager who was overly forgiving, not only of minor transgressions, but also behaviour that was toxic or harmful to others. Punishment is inherently unpleasant, and the overly nice can be reluctant to mete it out, staying their hand while wrongdoers run amok. That not only undermines the moral community, but it makes it harder to hold people to account for their actions, preventing them from growing by learning from their mistakes.

Niceness is good. Be nice. But not so nice that you allow others to be nasty.

BY Dr Tim Dean

Dr Tim Dean is Philosopher in Residence at The Ethics Centre and author of How We Became Human: And Why We Need to Change.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships

What makes a business honest and trustworthy?

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

When are secrets best kept?

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Climate + Environment, Relationships

ESG is not just about ticking boxes, it’s about earning the public’s trust

Explainer

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Dignity

On saying “sorry” most readily, when we least need to

On saying “sorry” most readily, when we least need to

Opinion + AnalysisRelationships

BY Emma Wilkins 23 NOV 2023

One of the first things I learned when travelling in Europe, knowing only English, was to prioritise learning the word “sorry” when preparing to enter a new country.

There’s nothing wrong with learning “hello”, “thank you” and “please”, “I am…” and “where’s the nearest…”, but if you’re going to learn one word by heart, that’s the one I’d recommend. If you get yourself in trouble, it will likely be the word you need the most.

I speak from experience. Picture a nineteen-year-old washing her hands in the fountain at the foot of The Spanish Steps. Unbeknownst to her, the police have just rebuked some fellow tourists for cooling their sweaty feet in the waters of this national treasure—and told the watching crowd to heed their warning, show respect.

When their whistles blew at me and I was asked to show my passport, I didn’t have the words to explain that I’d just been to the loo and had been unable to find a handle for the tap. This was before sensors became commonplace; perhaps there was a pedal, but I hadn’t thought to look. Instead, I’d opened the door (with difficulty—I’d already covered my hands in pink slimy soap) and headed for the next available water source.

I had my reasons, but I didn’t have the words to explain why I’d done what I’d done, and until some friends explained later, I couldn’t fully understand why what I’d done had been so very wrong.

I could say Lo siento, and did, repeatedly.

I was reminded of this incident when reflecting on the ways in which we use the word “sorry” in daily life.

Sometimes we’re not apologising at all—we’re expressing sympathy to a bereaved friend, or being polite to a stranger. The bereavement “sorry” might translate to: “I wish you didn’t have to go through this”, or “I really feel for you”. The polite “sorry” to a stranger might translate to “excuse me”, or “I excuse you”. It might not be “performative” at all; we use it as a statement, nothing more. Or we’ll say “sorry I’m late” when we’re not sorry, but are late. If we really are sorry we’re late; our eyes, our tone, must do the work.

At other times, we apologise when we needn’t; we say “sorry” if we burst into tears when we are “supposed” to be keeping it together, or if we’ve had to ask for help when we’d hoped to solve a problem on our own.

In the workplace, if we’ve been asked to do something we haven’t been trained to do, and need to take up a manager’s time to find out how, we might apologise when really, we’re just doing our job, and asking them to do theirs.

In the context of close friendship, pouring out our worries, or asking for help, or advice, or both, isn’t something to apologise for, it’s (in part) what friendship is for. I know this, yet I find myself behaving otherwise. Just the other day I said “sorry” to a friend while crying on the phone, even though when friends do this to me I tell them off. Being trusted in this way honours a person more than it puts them out. When you love someone, you want to help; real “sorry” territory is more likely to be shutting a loved one out, than letting them in.

This is because “real sorry territory” is using the word in the deepest sense of the word; it’s apologising for hurting someone. It’s not using the word to escape consequence, it’s using the word to express heartfelt regret for causing real harm and, rather than making excuses, choosing to take responsibility.

It can be easy to say “sorry” when we don’t really mean it—when we’re being polite, when we’re going through a motion, avoiding punishment. It’s easy to say it, even mean it, when we see we’ve made a dumb mistake: Lo siento! Lo siento! It can roll right off the tongue.

In the case of the Fontana della Barcaccia, I’m pretty sure my excuses would have only caused further offence. Looking back, I’m glad I couldn’t say another word. But that sorry didn’t cost me, it helped me.

It’s using the word to admit—to ourselves as much as to somebody else—that we’ve not only caused offence, but ongoing hurt, and to ask for undeserved forgiveness, that’s hard. Even if we haven’t done wrong technically, we might have had a chance to help, and turned away. Using “sorry” to express true regret—to “repent”—could be the rarest use of “sorry” there is.

The rarest and, when it’s sincere, when it changes how we think and act, the most powerful. A word that can mean little can mean much; can be the difference between making excuses, or facing the truth; between a wound that keeps on causing pain, and one that, finally, begins to heal.

BY Emma Wilkins

Emma Wilkins is a journalist and freelance writer with a particular interest in exploring meaning and value through the lenses of literature and life. You can find her at: https://emmahwilkins.com/

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Science + Technology

With great power comes great responsibility – but will tech companies accept it?

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

We shouldn’t assume bad intent from those we disagree with

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

Community is hard, isolation is harder

Explainer

Business + Leadership, Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Moral injury

Whose fantasy is it? Diversity, The Little Mermaid and beyond

Whose fantasy is it? Diversity, The Little Mermaid and beyond

Opinion + AnalysisSociety + CultureRelationships

BY Joseph Earp 20 NOV 2023

The original The Little Mermaid, an animated fable about a young woman searching – literally – for her voice, has what may seem like only a loose relationship with reality.

Sure, the film is filled with themes of yearning, the desire for autonomy, and a struggle for independence, all of which still resonate deeply with the lived experience of its target audience of young women. But it’s also populated with a singing fish, a cursed sea witch, and a range of colourful, deeply fantastical supporting characters.

But in our increasingly divided age, fantasy is not a simple proposition anymore. Just look at the culture war that the CGI-saturated remake of The Little Mermaid has been dragged into, with the film facing “backlash” from those who have argued that the casting of a black Ariel (Halle Bailey) represents a break from “reality”. Their argument – that this new Ariel is not the one they grew up with, a premise that rests on the idea that there is a “real” Ariel to be deviated from.

These arguments are, in essence, arguments about the nature of fantasy – about how fantastical these stories are allowed to be. Fantasy authors can do anything. So what should they do?

How much fantasy is allowed?

The Little Mermaid is not the only modern fantasy story that has been plunged into debates around diversity and representation. The characters of Rey and Rose Tico from Disney’s new Star Wars trilogy faced significant backlash for being female, while the series’ black Stormtrooper, Finn, was criticised as breaking the canon. Stormtroopers were clones, went the argument – so how could one of them be black? Indeed, racist backlashes against casting in fantasy have become so commonplace that Moses Ingram, who played the villainous Reva Sevander in the Obi-Wan Kenobi miniseries, started sharing some of the vile messages that she received.

Those responsible for these backlashes tend to argue that the casting of diverse actors “breaks canon”, and disrupts storytelling rules. Some fans will argue that as Stormtroopers are always white in the world of the Star Wars story, they always must be. This was the explanation for the backlash that met the casting of diverse actors in the new Lord of the Rings series, The Rings of Power – Tolkien’s world was white, went the argument, so any story told in that world should be too. Of course, these “fans” do not acknowledge the possibility that the canon of these stories could be racist, and that breaking the canon might be morally necessary. They merely hold to the story as it was written.

This is an argument about fantasy: about how “real” these stories should be. Fantasy authors can do anything, tell any story, infuse their characters with magical explanations that fly in the face of reality. But they do still have to abide but certain rules. No-one would enjoy the world of Hogwarts if J.K. Rowling constantly threw up magical explanations that defied one another to advance the plot. There needs to be some consistency; some “reality”.

Those who cry foul when diverse actors are cast in fantasy do so because they have smuggled a bad ethical argument into one about consistency.

They are making an ethical claim – they do not want to see diverse communities in their art – and pretending it is an aesthetic claim – that they are talking about stories, not about ethics.

In at least some cases, we can assume that this is just a bad faith argument: that these people know in our modern age that they cannot make an openly racist remark, and so scratch around in the world of aesthetics to disguise their bigotry. But even if these people really think that they’re talking about aesthetics, the mistake is to assume that ethics and aesthetics easily pull apart.

Your dreams aren’t divorced from the real world

In her landmark essay The Right To Sex, the philosopher Amia Srinivasan explores the moral weight of aesthetic choices. In her case, she was exploring those who express sexual preference – cis men who desire a certain kind of woman, for instance, with a certain body. But her conclusions are helpful for us here too.

In essence, Srinivasan wants to balance the freedom to choose – people should be able to desire whom they want to desire, and not be forced to change their desires by others – with the idea that some choices are bigoted or small-minded in some way – say, the person who only desires Asian women, or the person who doesn’t desire any Asian women at all.

What Srinivasan encourages is an interest in one’s own desires. She suggests people explore and understand why they want what they want, and to be aware that sometimes those wants can come from bad, unethical places. In essence, Srinivasan made it clear that purely aesthetic choices are actually ethical choices – that things that seem “merely a matter of taste” can actually come from bigotry.

So it goes with fantasy. The fantasy genre is one of dreams; of pure imagination. But that imagination is born from the real-world. And our real-world contains bigotry and hate.

Fantasy writers dream, but they dream in a way that is influenced by morals, preferences, and real-world concerns.

This isn’t just imaginative play. This is play that is responsive to the real world. And as such, ethics should remain a concern. There are people out there who say that they genuinely desire a white Ariel – that seeing a Caucasian mermaid is of tantamount importance to them. What Srinivisan teaches us, is that we do not need to see this desire as emerging from a vacuum. It’s not “just” taste. It’s taste formed from a society that for too long has prioritised white bodies.

It’s like the philosopher Regina Swanson writes.: “[Fantasy] writers bring form to formlessness, creating a narrative that arises from the deep inner places of the mind,” she has put it. “As such, fantasy can reveal our collective hopes, dreams, and nightmares.” Those hopes, dreams, and nightmares aren’t “just” fantasies. They’re meaningfully real.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Big thinker

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Big Thinker: Shulamith Firestone

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Violent porn denies women’s human rights

WATCH

Relationships

Purpose, values, principles: An ethics framework

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture

Ethics on your bookshelf

BY Joseph Earp

Joseph Earp is a poet, journalist and philosophy student. He is currently undertaking his PhD at the University of Sydney, studying the work of David Hume.

The ethics of exploration: We cannot discover what we cannot see

The ethics of exploration: We cannot discover what we cannot see

Opinion + AnalysisRelationshipsScience + Technology

BY Simon Longstaff 2 NOV 2023

For many years, I took it for granted that I knew how to see. As a youth, I had excellent eyesight and would have been flabbergasted by any suggestion that I was deficient in how I saw the world.

Yet, sometime after my seventeenth birthday, I was forced to accept that this was not true, when, at the end of the ship-loading wharf near the town of Alyangula on Groote Eylandt, I was given a powerful lesson on seeing the world. Set in the northwestern corner of Australia’s Gulf of Carpentaria, Groote Eylandt is the home of the Anindilyakwa people. Made up of fourteen clans from the island and archipelago and connected to the mainland through songlines, these First Nations people had welcomed me into their community. They offered me care and kinship, connecting me not only to a particular totem, but to everything that exists, seen and unseen, in a world that is split between two moieties. The problem was that this was a world that I could not see with my balanda (or white person’s) eyes.

To correct the worst part of my vision, I was taken out to the end of the wharf to be taught how to see dolphins. The lesson began with a simple question: “Can you see the dolphins?” I could not. No matter how hard I looked, I couldn’t see anything other than the surface of the waves and the occasional fish darting in and out of the pylons below the wharf. “Ah,” said my friends, “the problem is that you’re looking for dolphins!” “Of course, I’m looking for dolphins,” I said. “You just told me to look for dolphins!” Then came the knockdown response. “But, bungie, you can’t see dolphins by looking for dolphins. That’s not how to see. What you see is the pattern made by a dolphin in the sea.”

That had been my mistake. I had been looking for something in isolation from its context. It’s common to see the book on the table, or the ship at sea, where each object is separate from the thing to which it is related in space and time. The Anindilyakwa mob were teaching me to see things as a whole. I needed to learn that there is a distinctive pattern made by the sea where there are no dolphins present, and another where they are. For me, at least, this is a completely different way of seeing the world and it has shaped everything that I have done in the years since.

This leads me to wonder about what else we might not see due to being habituated to a particular perspective on the world.

There are nine or so ethical lenses through which an explorer might view the world. Each explorer will have a dominant lens and can be certain that others they encounter will not necessarily see the world in the same way. Just as I was unable to see dolphins, explorers may not be able to see vital aspects of the world around them—especially those embedded in the cultures they encounter through their exploration.

Ethical blindness is a recipe for disaster at any time. It is especially dangerous when human exploration turns to worlds beyond our own. I would love to live long enough to see humans visiting other planets in our solar system. Yet, I question whether we have the ethical maturity to do this with the degree of care required. After all, we have a parlous record on our own planet. Our ethical blindness has led us to explore in a manner that has been indifferent to the legitimate rights and interests of Indigenous peoples, whose vast store of knowledge and experience has often either been ignored or exploited.

Western explorers have assumed that our individualistic outlook is the standard for judgment. Even when we seek to do what is right, we end up tripping over our own prejudice. We have often explored with a heavy footprint or with disregard for what iniquities might be made possible by our discoveries.

There is also the question of whether there are some places that we ought not explore. The fact that we can do something does not mean that it should be done. Inverting Kant’s famous maxim that “ought implies can,” we should understand that can does not imply ought! I remember debating this question with one of Australia’s most famous physicists, Sir Mark Oliphant. He had been one of those who had helped make possible the development of the atomic bomb. He defended the basic science that made this possible while simultaneously believing that nuclear weapons are an abomination. He put it to me that science should explore every nook and cranny of the universe, as we can only control what is known and understood. Yet, when I asked him about human cloning, Oliphant argued that our exploration should stop at the frontier. He could not explain the contradiction in his position. I am not sure anyone has yet clearly defined where the boundary should lie. However, this does not mean that there is no line to be drawn.

So how should the ethical landscape be mapped for (and by) explorers? For example, what of those working on the de-extinction of animals like the thylacine (Tasmanian tiger)? Apart from satisfying human curiosity and the lust to do what has not been done before, should we bring this creature back into a world that has already adapted to its disappearance? Is there still a home for it? Will developments in artificial intelligence, synthetic biology, gene editing, nanotechnology, and robotics bring us to a point where we need to redefine what it means to be human and expand our concept of personhood? What other questions should we anticipate and try to answer before we traverse undiscovered country?

This is not to argue that we should be overly timid and restrictive. Rather, it is to make the case for thinking deeply before striking out, for preparing our ethics with as much care as responsible explorers used to give to their equipment and stores.

The future of exploration can and should be ethical exploration, in which every decision is informed by a core set of values and principles. In this future, explorers can be reflective practitioners who examine life as much as they do the worlds they encounter. This kind of exploration will be fully human in its character and quality. Eyes open. Curious and courageous. Stepping beyond the pale. Humble in learning to see—to really see—what is otherwise obscured within the shadows of unthinking custom and practice.

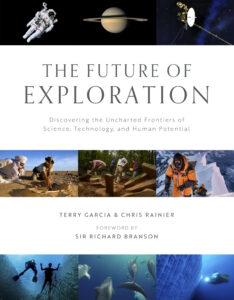

This is an edited extract from The Future of Exploration: Discovering the Uncharted Frontiers of Science, Technology and Human Potential. Available to order now.

BY Simon Longstaff

After studying law in Sydney and teaching in Tasmania, Simon pursued postgraduate studies in philosophy as a Member of Magdalene College, Cambridge. In 1991, Simon commenced his work as the first Executive Director of The Ethics Centre. In 2013, he was made an officer of the Order of Australia (AO) for “distinguished service to the community through the promotion of ethical standards in governance and business, to improving corporate responsibility, and to philosophy.”

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Big thinker

Relationships

Big Thinker: Kate Manne

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Conservatism

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships, Society + Culture

Extending the education pathway

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Exercising your moral muscle

Unconscious bias

Our brains are evolved to help us survive.

That means they take a lot of shortcuts to help us get through the day. These shortcuts, or heuristics, are vital. But they come at a cost. Learn what unconscious bias is and how you become aware of your own unconscious bias.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships, Science + Technology

When do we dumb down smart tech?

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Parenting philosophy: Stop praising mediocrity

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Intimate relationships matter: The need for a fairer family migration system in Australia

Big thinker

Relationships

Big Thinker: Immanuel Kant

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

How to have moral courage and moral imagination

Every time we make a decision, we change the world just a little bit.

This is why moral imagination plays a crucial role in good ethical decision making. It helps us appreciate other people’s perspective. And sometimes when we must make those decisions, they can be difficult, this is where moral courage comes into play.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Big thinker

Relationships

Big Thinker: Simone Weil

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Send in the clowns: The ethics of comedy

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

Community is hard, isolation is harder

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Ending workplace bullying demands courage

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Moral intuition and ethical judgement

By checking in to our intuitions and using them to inform our judgements, we can come up with decisions that make sense, but also feel right.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Ask an ethicist: How should I divvy up my estate in my will?

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships

It’s time to take citizenship seriously again

Big thinker

Relationships

Big Thinker: Buddha

Opinion + Analysis

Climate + Environment, Politics + Human Rights, Relationships