Extending the education pathway

Extending the education pathway

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + LeadershipRelationshipsSociety + Culture

BY The Ethics Centre 16 JAN 2020

In the course of 2019, The Ethics Centre reviewed and adopted a new strategy for the five years to 2024.

The key insight to emerge from the strategic planning process was that the Centre should focus on growing its impact through innovation, partnerships, platforms and pathways.

We focus here on just one of those factors – ‘pathways’ and, in particular, the education pathway.

The Ethics Centre is not new to the education game. To this day, the establishment of Primary Ethics – which teaches tens of thousands of primary students every week in NSW – is one of our most significant achievements.

As Primary Ethics continues to break new ground, we feel it’s time to bring our collective skills to bear along the broader education pathway.

With this in mind, we’re delighted to report that The Ethics Centre and NSW Department of Education and Training have signed a partnership to develop curriculum resources and materials to support the teaching and learning of ethical deliberation skills in NSW schools, including within existing key learning areas.

This exciting project will see us working with and through the Department’s Catalyst Innovation Lab alongside gifted teachers and curriculum experts – rather than merely seeking to influence from the outside.

In addition, we have also formed a further partnership with one of the Centre’s Ethics Alliance members, Knox Grammar School. This will involve the establishment of an ‘Ethicist-in-residence’ at the school, the application of new approaches to exploring ethical challenges faced by young adults, and the development of a pilot program where students in their final years of secondary education undertake an ethics fellowship at the Centre.

In due course, we hope that the work pioneered in these two partnerships and others will produce scalable platforms that can be extended across Australia. Detailed plans come next, and we believe the potential for impact along this pathway is significant.

We believe ethics education is a central component of lifelong learning – extending from the earliest days of schooling through secondary schooling, higher education and into the workplace.

The broadening of the education pathway therefore provides new opportunities for The Ethics Centre and Primary Ethics to work together – sharing our complementary skills and experience in service of our shared objectives, for the common good.

If you have an interest in supporting this work, at any point along the pathway, then please contact Dr Simon Longstaff at The Ethics Centre, or Evan Hannah, who leads the team at Primary Ethics.

Dr Simon Longstaff is Executive Director of The Ethics Centre: www.ethics.org.au

Evan Hannah can be contacted via Primary Ethics at: www.primaryethics.com.au

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Science + Technology

Blockchain: Some ethical considerations

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights

Democracy is still the least-worst option we have

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Send in the clowns: The ethics of comedy

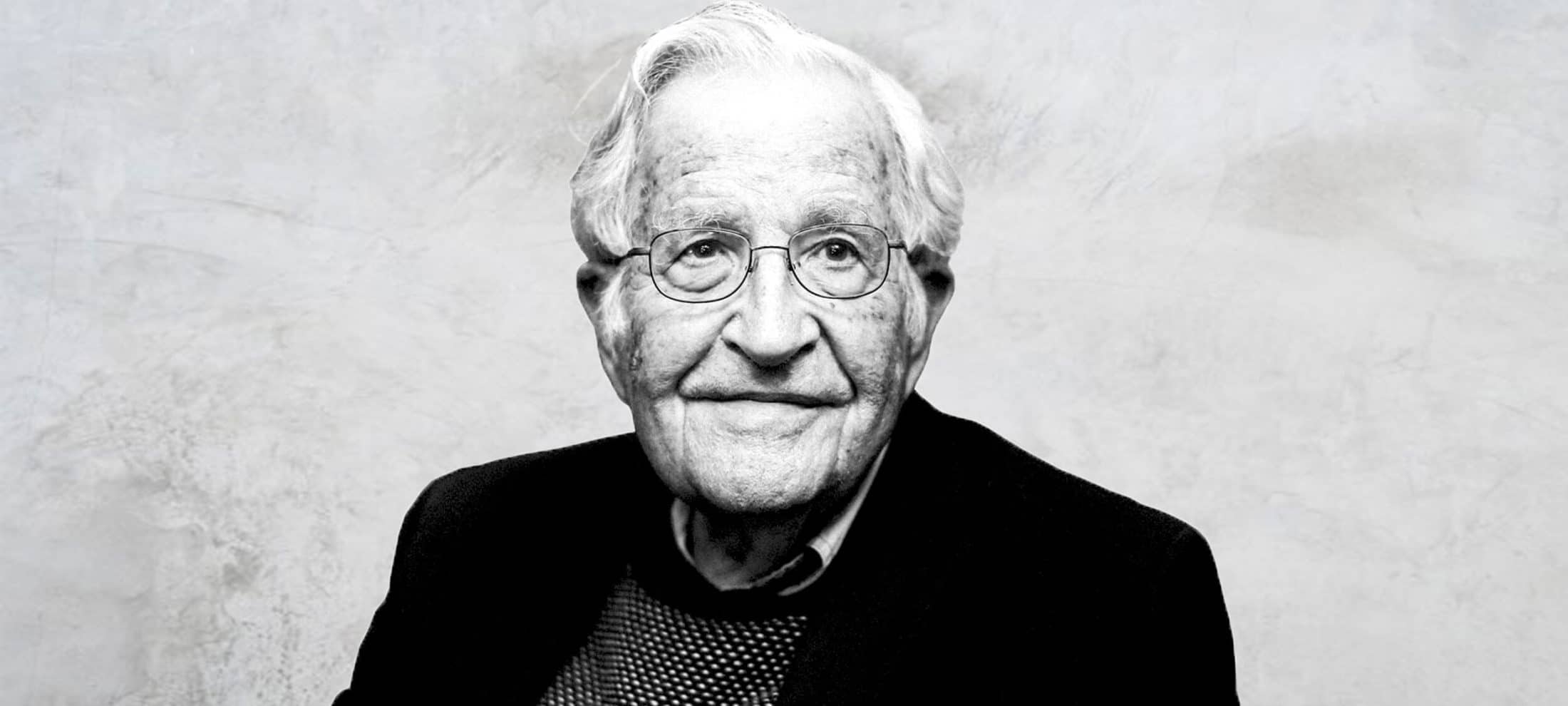

Big thinker

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Big Thinker: Noam Chomsky

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

A burning question about the bushfires

A burning question about the bushfires

Opinion + AnalysisClimate + EnvironmentPolitics + Human RightsRelationships

BY Simon Longstaff The Ethics Centre 16 JAN 2020

At the height of the calamity that has been the current bushfire season, people demanded to know why large parts of our country were being ravaged by fires of a scale and intensity seldom seen.

In answer, blame has been sheeted home to the mounting effects of climate change, to failures in land management, to our burgeoning population, to the location of our houses, to the pernicious deeds of arsonists…

However, one thing has not made the list, ethical failure.

I suspect that few people have recognised the fires as examples of ethical failure. Yet, that is what they are. The flames were fuelled not just by high temperatures, too little rain and an overabundance of tinder-dry scrub. They were also the product of unthinking custom and practice and the mutation of core values and principles into their ‘shadow forms’.

Bushfires are natural phenomena. However, their scale and frequency are shaped by human decisions. We know this to be true through the evidence of how Indigenous Australians make different decisions – and in doing so – produce different effects.

Our First Nations people know how to control fire and through its careful application help the country to thrive. They have demonstrated (if only we had paid attention) that there was nothing inevitable about the destruction unleashed over the course of this summer. It was always open to us to make different choices which, in turn, would have led to different outcomes.

This is where ethics comes in. It is the branch of philosophy that deals with the character and quality of our decisions; decisions that shape the world. Indeed, constrained only by the laws of nature, the most powerful force on this planet is human choice. It is the task of ethics to help people make better choices by challenging norms that tend to be accepted without question.

This process asks people to go back to basics – to assess the facts of the matter, to challenge assumptions, to make conscious decisions that are informed by core values and principles. Above all, ethics requires people to accept responsibility for their decisions and all that follows.

This catastrophe was not inevitable. It is a product of our choices.

For example, governments of all persuasions are happy to tell us that they have no greater obligation than to keep us safe. It is inconceivable that our politicians would ignore intelligence suggesting that a terrorist attack might be imminent. They would not wait until there was unanimity in the room. Instead, our governments would accept the consensus view of those presenting the intelligence and take preventative action.

So, why have our political leaders ignored the warnings of fire chiefs, defence analysts and climate scientists? Why have they exposed the community to avoidable risks of bushfires? Why have they played Russian Roulette with our future?

It can only be that some part of society’s ‘ethical infrastructure’ is broken.

In the case of the fires, we could have made better decisions. Better decisions – not least in relation to the challenges of global emissions, climate change, how and where we build our homes, etc. – will make a better world in which foreseeable suffering and destruction is avoided. That is one of the gifts of ethics.

Understood in this light, there is nothing intangible about ethics. It permeates our daily lives. It is expressed in phenomena that we can sense and feel.

So, if anyone is looking for a physical manifestation of ethical failure – breathe the smoke-filled air, see the blood-red sky, feel the slap from a wall of heat, hear the roar of the firestorm.

The fires will subside. The rains will come. The seasons will turn. However, we will still be left to decide for the future. Will our leaders have the moral courage to put the public interest before their political fortunes? Will we make the ethical choice and decide for a better world?

It is our task, at The Ethics Centre, to help society do just that.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Explainer

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Dignity

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

It’s time to increase racial literacy within our organisations

Opinion + Analysis, READ

Politics + Human Rights

How to find moral clarity in Gaza

Explainer

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights

Ethics Explainer: Dirty Hands

BY Simon Longstaff

Simon Longstaff began his working life on Groote Eylandt in the Northern Territory of Australia. He is proud of his kinship ties to the Anindilyakwa people. After a period studying law in Sydney and teaching in Tasmania, he pursued postgraduate studies as a Member of Magdalene College, Cambridge. In 1991, Simon commenced his work as the first Executive Director of The Ethics Centre. In 2013, he was made an officer of the Order of Australia (AO) for “distinguished service to the community through the promotion of ethical standards in governance and business, to improving corporate responsibility, and to philosophy.” Simon is an Adjunct Professor of the Australian Graduate School of Management at UNSW, a Fellow of CPA Australia, the Royal Society of NSW and the Australian Risk Policy Institute.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

How to respectfully disagree

We seem to have no trouble hurling opinions at each other. It is easy enough to form into irresistible blocks of righteous indignation. But discussion – why do we find it so hard?

What happened to the serious playfulness that used to allow us to pick apart an argument and respectfully disagree? When did life become ‘all or nothing’, a binary choice between ‘friend or foe’?

Perhaps this is what happens when our politics and our media come to believe they can only thrive on a diet of intense difference. Today, every issue must have its champions and villains. Things that truly matter just overwhelm us with their significance. Perhaps we feel ungainly and unprepared for the ambiguities of modern life and so clutch on to simple certainties.

Today, every issue must have its champions and villains. Perhaps we feel ungainly and unprepared for the ambiguities of modern life and so clutch on to simple certainties.

Indeed, I think this must be it. Most of us have a deep-seated dislike of ambiguity. We easily submit to the siren call of fundamentalists in politics, religion, science, ethics… whatever. They sing to us of a blissful state within which they will decide what needs to be done and release us from every burden except obedience.

But there is a price to pay for certainty. We must pay with our capacity to engage with difference, to respect the integrity of the person who holds a principled position opposed to our own. It is a terrible price we pay.

The late, great cultural theorist and historian Robert Hughes ended his history of Australia, The Fatal Shore, with an observation we would do well to heed.

“The need for absolute goodies and absolute baddies runs deep in us, but it drags history into propaganda and denies the humanity of the dead: their sins, their virtues, their failures. To preserve complexity, and not flatten it under the weight of anachronistic moralising, is part of the historian’s task.”

And so it is for the living. The ‘flat man’ of history is quite unreal. The problem is too many of us behave as if we are surrounded by such creatures. They are the commodities of modern society, the stockpile to be allocated in the most efficient and economical manner.

Each of them has a price because none of them is thought to be of intrinsic value. Their beliefs are labels, their deeds are brands. We do not see the person within. So, we pitch our labels against theirs – never really engaging at a level below the slogan.

It was not always so. It need not be so.

I have learned one of the least productive things one can do is seek to prove to another person they are wrong. Despite knowing this, it is a mistake I often make and always end up wishing I had not.

The moment you set out to prove the error of another person is the moment they stop listening to you. Instead, they put up their defences and begin arranging counter-arguments (or sometimes just block you out).

Far better it is to make the attempt (and it must be a sincere attempt) to take the person and their views entirely seriously. You have to try to get into their shoes, to see the world through their eyes. In many cases people will be surprised by a genuine attempt to understand their perspective. In most cases they will be intrigued and sometimes delighted.

The aim is to follow the person and their arguments to a point where they will go no further in pursuit of their own beliefs. Usually, the moment presents itself when your interlocutor tells you there is a line, a boundary they will not cross. That is when the discussion begins.

At that point, it is reasonable to ask, “Why so far, but no further?” Presented as a case of legitimate interest (and not as a ‘gotcha’ moment) such a question unlocks the possibility of a genuinely illuminating discussion.

To follow this path requires mutual respect. Recognition that people of good will can have serious disagreements without either of them being reduced to a ‘monstrous’ flat man of history. It probably does not help that so much social media is used to blaze emotion or to rant and bully under cover of anonymity. People now say and do online things few would dare if standing face-to-face with another.

It probably does not help that we are becoming desensitised to the pain we cause the invisible victims of a cruel jibe or verbal assault. Nor does it help that the liberty of free speech is no longer understood to be matched by an implied duty of ethical restraint.

I am hoping the concept of respectful disagreement might make a comeback. I am hoping we might relearn the ability to discuss things that really matter – those hot, contentious issues that justifiably inflame passions and drive people to the barricades. I am hoping we can do so with a measure of good will. If there is to be a contest of ideas, then let it be based on discussion.

Then we might discover there are far more bad ideas than there are bad people.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture, Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

The personal vs the political: Resistance in One Battle After Another

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Standing up against discrimination

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships, Society + Culture

Of what does the machine dream? The Wire and collectivism

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

The #MeToo debate – recommended reads

BY Simon Longstaff

Simon Longstaff began his working life on Groote Eylandt in the Northern Territory of Australia. He is proud of his kinship ties to the Anindilyakwa people. After a period studying law in Sydney and teaching in Tasmania, he pursued postgraduate studies as a Member of Magdalene College, Cambridge. In 1991, Simon commenced his work as the first Executive Director of The Ethics Centre. In 2013, he was made an officer of the Order of Australia (AO) for “distinguished service to the community through the promotion of ethical standards in governance and business, to improving corporate responsibility, and to philosophy.” Simon is an Adjunct Professor of the Australian Graduate School of Management at UNSW, a Fellow of CPA Australia, the Royal Society of NSW and the Australian Risk Policy Institute.

Want to live more ethically? Try these life hacks

Want to live more ethically? Try these life hacks

Opinion + AnalysisHealth + WellbeingRelationships

BY The Ethics Centre 19 DEC 2019

If you’re looking for ways to support a more ethical life, here are five simple lifestyle changes that can help get you there.

Get back to nature

Aristotle believed everything in nature contains “something of the marvellous”. It turns out nature might also help make us a bit more marvellous. Research by Jia Wei Zhang and colleagues revealed how “perceiving natural beauty” (basically, looking at nature and recognising how wonderful it is) can make you more prosocial. Specifically, it can make you more helpful, trusting and generous. Nice one, trees.

The apparent reason for this is because a connection with nature leads to an increase in the experience of positive emotions. People are happier when they are connected with nature and other research suggests happy people tend to be more prosocial. Inadvertently, Zhang and his colleagues learned, this means nature helps make us better team players.

Read literature to develop ‘Theory of Mind’

In psychology, ‘Theory of Mind’ refers to the ability to understand the emotions, intentions and mental states of other people and to understand other people’s mental states are different from our own. It’s a crucial component of empathy. Like most things, our Theory of Mind improves with practice.

David Comer Kidd and Emanuele Castano think one way of practising and developing Theory of Mind is by reading literary fiction. They believe literature “uniquely engages the psychological processes needed to gain access to characters’ subjective experiences” because it doesn’t aim to entertain readers but challenge them.

Work up a sweat

As well as the health benefits it brings, exercise can make you a more virtuous person. Philosopher Damon Young believes exercise brings about “subtle changes to our character: we are more proud, humble, generous or constant”.

Pride is usually seen as a vice but exercise can give us a healthy sense of pride, which Young defines as “taking pleasure in yourself”. Taking pleasure in ourselves and recognising ourselves as valuable has obvious benefits for self-esteem, but it also gives us a heightened sense of responsibility. By taking pride in the work we’ve invested in ourselves, we acknowledge the role we have making change in the world, a feeling with applications far broader than the gym.

Take meal breaks when you’re making decisions

In 2011, an Israeli parole board had to consider several cases on the same day. Among them were two Arab-Israelis, each of them serving 30 months for fraud. One of them received parole, the other didn’t. The only difference? One of their hearings was at the start of the day, the other at the end.

Researcher Shai Danzigner and co-authors concluded “decision fatigue” explained the difference in the judges’ decisions. They found the rate of favourable rulings were around 65% just after meal breaks at the start of the day and lunch time, but they diminished to 0% by the end of the session.

There’s some good news though. The research suggests a meal break can put your decision making back on track. Maybe it’s time to stop taking lunch at your desk.

Get a good night’s sleep

We’ve been starting to pay more attention to the social costs of exhaustion. In NSW, public awareness campaigns now list fatigue as one of the ‘big three’ factors in road fatalities alongside speeding and drink driving. It turns out even if it doesn’t kill you, exhaustion can lead to ethical compromises and slip ups in the workplace.

In 2011, Christopher Barnes and his colleagues released a study suggesting “employees are less likely to resist the temptation to engage in unethical behaviour when they are low on sleep”. When we’re tired we experience ‘ego depletion’ – weakening our self-control. Experiments conducted by Barnes’ team suggest when we’re tired we’re vulnerable to cutting corners and cheating. So, if you’re thinking of doing something dodgy, sleep on it first.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

Nothing But A Brain: The Philosophy Of The Matrix: Resurrections

Big thinker

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Big Thinker: Mary Wollstonecraft

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Enwhitenment: utes, philosophy and the preconditions of civil society

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Why morality must evolve

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Five stories to read to your kids this Christmas

Five stories to read to your kids this Christmas

Opinion + AnalysisHealth + WellbeingRelationships

BY Matthew Beard 19 DEC 2019

The kids are on school holidays but the lessons don’t have to end there. Christmas time offers a great opportunity to teach our kids about ethics. Philosopher Dr Matt Beard shares his top stories for sharing ethical ideas with your children.

1. How the Grinch Stole Christmas – Doctor Seuss

The Grinch is a lonely monster who lives by himself on Mt Crumpit. Bothered by the Christmas noise from nearby Whoville he decides to spoil their fun. Disguised as a particularly ugly Santa Clause, the Grinch sneaks down the chimneys of the people of Whoville and steals their gifts. But to the Grinch’s surprise, he can’t dent the Whos’ Christmas spirit and his heart starts to melt.

“What if Christmas, he thought, doesn’t come from a store? What if Christmas… perhaps… means a little bit more?”

This classic by Doctor Seuss is more relevant than ever for kids growing up in an age when the holiday season is increasingly commercialised. The Whos lose all their ‘stuff’ but don’t lose their sense of Christmas. How would you or your kids feel if there were no presents at Christmas? What would you celebrate?

2. The Selfish Giant – Oscar Wilde

Not technically a Christmas story, but still a lovely one for this time of year. It’s the tale of a selfish giant who first refuses to allow children to play in his gardens and then has a change of heart.

This story has extra resonance for readers within the Christian tradition (and kids may need an explainer as to what the ending means), but the message does transcend religion. Talk to your kids about how selfishness can be isolating, joys shared are joys multiplied and the importance of showing kindness to whomever we meet – strong, weak, tall, clever or otherwise.

3. The Lump of Coal – Lemony Snicket

Coal is the perennial threat against children – bad kids get given coal. But what happens when a lump of coal is good? What happens if the child who receives it wants to make art? And do all kids who receive a lump of coal turn out rotten?

Lemony Snicket’s short story big questions of authenticity and purpose through a living lump of coal that flees a barbeque in search of it’s own purpose. After some failed endeavours he meets a department store Santa who puts him into his ‘bratty’ son’s stocking.

But his son doesn’t feel punished. Together with the lump of coal they become successful artists and open a restaurant in Korea.

“It is a miracle if you can find true friends, and it is a miracle if you have enough food to eat, and it is a miracle if you get to spend your days and evenings doing whatever it is you like to do.”

It’s not your typical Christmas story, but that’s part of the appeal. Are we forced to be the people we’re born as? The Lump of Coal teaches us gratitude for the everyday and an ability to overcome social origins of birth.

4. The Gift of the Magi – O Henry

This is a personal favourite and a good one to read before you take your kids off for a last minute Christmas shop. A married couple, both hard up for money, are desperate to buy each other wonderful gifts. Della wants to buy James a superb chain for his watch, which is his prized possession. To pay for it she sells her hair – her pride and joy, and James’ too. She buys James a fetching chain only to learn he has sold his watch to buy her a new set of combs!

“But in a last word to the wise of these days let it be said that of all who give gifts these two were the wisest. Of all who give and receive gifts, such as they are wisest. Everywhere they are wisest. They are the magi.”

The Gift of the Magi could seem absurd to some – to highlight the pointlessness of our obsession with giving. But that wasn’t the message O Henry hoped readers would take away. He wanted to highlight the true meaning of gift giving – a thoughtful gesture to rekindle a connection to the other person.

5. The Original Christmas Story

Whether or not you’re religious, the origins of Christmas lie in the same story – of a baby in a manger, surrounded by shepherds, angels and wise men. Props aside there are universal messages to be gleaned from religious stories and traditions.

The Christian story holds that the world’s saviour arrived as a newborn child into a stable for farm animals. It’s worth having a talk about how this image contrasts with our usual ideas about power.

Do we sometimes dismiss people because of where they’ve come from or how much money they have?

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

A guide to ethical gift giving (without giving to charity)

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships

Beyond the headlines of the Westpac breaches

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Ask an ethicist: do teachers have the right to object to returning to school?

WATCH

Relationships

What is ethics?

BY Matthew Beard

Matt is a moral philosopher with a background in applied and military ethics. In 2016, Matt won the Australasian Association of Philosophy prize for media engagement. Formerly a fellow at The Ethics Centre, Matt is currently host on ABC’s Short & Curly podcast and the Vincent Fairfax Fellowship Program Director.

Violence and technology: a shared fate

Violence and technology: a shared fate

Opinion + AnalysisRelationshipsSociety + Culture

BY The Ethics Centre 17 DEC 2019

Don’t be distracted by the exploding sheds, steamrolled silverware and factory pressed field of poppies.

Many of the best works in Cornelia Parker’s exhibition at the Museum of Contemporary Art (MCA) are small and unassuming. They are the quiet pieces that ask us to contemplate the nature of the technology we use in acts of violence.

A small pile of dust, some short leads of wire, a child’s doll split in two. These found object artworks – sculptures, just not those carved into marble or clay – are less about the state you see them in, but the journey they have taken.

On closer inspection (and with a little gallery guidance) we find intentional transformations of objects often associated with brutal violence: a gun, its bullets, the blade of a guillotine.

But don’t be alarmed. There is a dark sense of humour at play here. The disemboweled doll, a ginger-haired child in his newsboy cap and overalls, has a cartoon quality to his expression that echoes less of screams of pain than the shock of a bee sting. The boy has been severed at the waist by a guillotine. The very same guillotine that beheaded the infamous Queen of France, Marie Antoinette.

We understand a guillotine as a tool of violence and power, designed to distribute French revolutionary justice at speed to behead the head of state. Here Parker has used the same tool that once transformed European history, to split a stuffed toy of Oliver Twist. Its title suggests a shared fate, that this piece of technology link the iconic Dickensian poor boy and the poster woman for opulence.

Shared Fate (Oliver), Cornelia Parker (2008)

The works on display in the gallery often ask us to consider what these tools of violence are used for, and our role in using them.

Sawn Up Sawn Off Shotgun (2015) has a similar tale of transformation. The story goes: a factory manufactured a shotgun, a criminal cut off its barrel to make it deadlier. He used it to murder an innocent person. It was collected as evidence by police to convict the man, before being decommissioned by being cut into smaller segments. It sits lifeless in front of us now in this quartered state.

In what way was the gun designed to kill? How did the modifications by each person impact its deadliness? And how does its use reflect on the ethics and values of those who designed, manufactured and modified this once-deadly artefact? It’s a neat example that calls to mind some of The Ethics Centre’s the principles for the ethics of design.

The design of the original shotgun, manufactured and distributed legally, embodied a set of values. Options include: the ‘good’ of farmers protecting their livestock from predators or the ‘good’ sporting competition using firearms. However, it was also a feature of the shotgun that beyond shooting ducks and foxes, it had the capacity to take a human life including during the commission of crimes. To what extent was that violent possibility actively noted and considered? Did the designer and manufacturer take any steps to protect against unintended uses?

Of course, we know also that the shotgun was modified and used beyond its intended purpose. By cutting off the barrel, the gun was deliberately modified to aid concealment and increase its deadly effect at close range. Whatever values might have been explicit in the original design are subverted by the modification where the explicit aim becomes to maim and kill in confined spaces.

This is what we consider the post-phenomenology of technology. We describe this in Ethics by Design: Principles for Good Technology as “…when a hitman picks up a firearm, he sets the purpose of the gun as a murder weapon. However, he also uses the gun to constitute himself as a murderer.”

We are told that the user in this case used this shotgun for just that purpose and in doing so made himself a murderer.

In its final transformation the design is changed once more. Using the same means as the criminal, cutting the shotgun again, the police officers have rendered it effectively useless. It no longer possesses the affordances of a weapon: no trigger to pull, no barrel to aim. It is a disembodied mess of its former designs, purpose and values. Here then the police constitute themselves as peace-keepers, because by destroying the deadly weapon they embody law and order.

Embryo Firearms (1995) Cornelia Parker.

If you take away from this the mantra that ‘guns don’t kill people, people kill people’ then there is another piece we are challenged to consider. Embryo Firearms (1995) presents two solid lumps of metal in the crude shape of pistols. At this point in their manufacturing they are absolutely harmless, resembling the type of gun you might cut from wood as a prop. These ‘guns’ are mere symbols – no more dangerous than any other lump of metal of equivalent heft.

We are informed though that this metal was intended to become a Colt firearm; one of millions produced each year.

The fact that any resulting weapon of this production process could be used for multiple purposes does not mean that it is ethically ‘neutral’. While guns themselves don’t have agency or intentions, their design and function shapes the user’s agency and open up a range of possible value-laden activities.

In their embryonic state these handguns provide as much agency as any slab of metal. We know at some point though, as the barrel is hollowed out, the firing pin is placed and the trigger is pulled, a tool of violent potential is born.

Transformation of intended design and purpose is taking place throughout Cornelia Parker’s works. Bullets are reduced to metal threads used to create geometric patterns, murder weapons are reduced to harmless dust via chemical precipitation, and our expectations about technology, art and violence are flipped on their heads.

The Ethics Centre is presenting The Ethics of Art and Violence a special event inspired by the work of acclaimed British artist Cornelia Parker currently on exhibition at the MCA. For more about the event click here.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Progressivism

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Science + Technology

The ethics of exploration: We cannot discover what we cannot see

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

CoronaVirus reveals our sinophobic underbelly

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

If you condemn homosexuals, are you betraying Jesus?

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Five dangerous ideas to ponder over the break

Five dangerous ideas to ponder over the break

Opinion + AnalysisRelationshipsSociety + Culture

BY The Ethics Centre 17 DEC 2019

If you’re gifted with downtime this holiday season, we’ve curated some big ideas for you to read, watch or listen to. These top picks will challenge your thinking over the holiday break.

-

The lost the art disagreement

In his keynote at the last Festival of Dangerous Ideas, Stephen Fry told us that “a Grand Canyon has opened up in our world and the crack grows wider every day. As it widens, enemies speak more and more incontinently about the other side.” Within this great fissure lies the lost art of disagreement. Hear how Fry suggests we begin to navigate through a world of seemingly opposing ideas.

-

Curb immigration, curb growth

Our cities are overcrowded, and our ecosystems are degrading at a rapid rate. Is population growth to blame? This year’s first IQ2 Debate: Curb Immigration, heard from environmental scientist Dr Jonathan Sobels, journalist Satyajet Marar, counter terrorism expert Dr Anne Aly and urban planner Professor Nicole Gurran. Watch the debate and hear their perspective on issues from urban planning and government policy, to environmental impacts and economic advantages.

-

An age of anger

Anarchy, resentment and the urge to smash the system seem to be spreading. What caused us to become so angry? How can we understand and navigate interactions with those who are? Author and academic Pankaj Mishra explains why society seems to be so quick to become outraged, and how transformative thinking might solve the epidemic.

-

Politics and populism

We are seeing a rise of nationalism, racism and authoritarian regimes across the world. Will democracy survive the new decade? At last year’s Festival of Dangerous Ideas Niall Ferguson contemplated the future of populist movements. Pankaj Mishra, Angela Nagle and Tim Soutphommasane joined a panel to explore if freedom is just too heavy a burden in the new world in the ‘Rehearsal for Fascism’.

-

Masculinity is not so fragile

Following the fallout of the #MeToo movement, many men feel that masculinity is unfairly under attack. David Leser, Zac Seidler, Raewyn Connell and Cath Lumby joined our IQ2 debate: Masculinity is it really so fragile, to share their views on modern masculinity and unpack the dangers or virtues of male normative behaviour.

The Festival of Dangerous Ideas returns in 2020, bringing a host of big thinkers and new perspectives to the dangerous issues we face. Gift vouchers are on sale now.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

The self and the other: Squid Game’s ultimate choice

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Who’s your daddy?

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Society + Culture

A new guide for SME’s to connect with purpose

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

Inside The Mind Of FODI Festival Director Danielle Harvey

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Joker broke the key rule of comic book movies: it made the audience think

Joker broke the key rule of comic book movies: it made the audience think

Opinion + AnalysisRelationshipsSociety + Culture

BY Matthew Beard The Ethics Centre 17 DEC 2019

Todd Phillip’s Joker has left audiences around the world outraged, moved and confused with its rewriting of the comic book lore surrounding The Joker.

The film tells the story of Arthur Fleck, a downtrodden man with an unspecified mental illness and an uncontrollable tendency to burst out laughing – whose treatment by society leads him down the path of moral nihilism and violence until he becomes the infamous Clown Prince of Crime.

It has received its share of controversy. Joker won the prestigious Golden Lion at the Venice Film Festival, is receiving early Oscar Buzz and has clocked over $850 million in the worldwide box office.

It’s also been heavily criticised for being overly sympathetic to the perpetrators of mass violence. Many critics Fleck’s turn from reserved, alienated performing clown to theatrical mass murderer as analogy for the lives of a number of real-world mass shooters.

Couple this with Joker’s depiction of systemic social forces, not individual people, as the true villains of our time, and it can be argued that the film offers an apology for people who use violence – often against women and people of colour – as a way of expressing their dissatisfaction with a world that hasn’t given them what they want.

The film is shot from Fleck’s perspective, and therefore casts huge doubt on what is real and what’s just happening in Fleck’s mind. Not long after watching it, I found myself trying to piece it all together. Did the climactic final act actually happen?

The genius and mischief of unreliable narrator motifs – think of Inception for example – is that we find ourselves looking for a definitive reading, but none exists. Not even the director is able to close the debate – theirs is just another interpretation.

Interestingly, the unreliable narrator question in Joker serves as a handy metaphor for broader confusion about the ethics and politics of the film. If the critical commentary and public discourse are anything to go by, the film left audiences confused not only about the reality of the story, but about its morality as well.

And here’s the central rub with Joker as a political and ethical challenge. It’s rife with ambiguity. What does it stand for? Who is the villain and who – if anybody – is the hero? Are we meant to empathise with Fleck or judge him? Should we join the masses in being furious at the uber-rich and uber-callous Thomas Wayne, or should we be concerned at the accelerating rate of violence?

Just like we don’t know for sure what was in Fleck’s mind and what really happened in the film, it’s hard to know what the film wants us to think about the events of Joker.

Warner Bros themselves tried to pre-load people’s expectations of the film by saying “make no mistake: neither the fictional character Joker, nor the film, is an endorsement of real-world violence of any kind. It is not the intention of the film, the filmmakers or the studio to hold this character up as a hero.”

Despite this effort, most viewers will have arrived at the film with pre-conceived ideas, because the critical conversations around Joker have been relentless. From the first trailers released and a leaked script, people have been speculating about the political effects it would have. Some critics – even some who think the film has artistic merit – wonder if it should have been made.

There is something interesting going on here. On the one hand, we have people experiencing Joker in wildly different ways. On the other hand, we have critics – and the film developers – moulding people’s views of the film before they’ve even seen it.

Then we have the film itself, which is concerned with how easy it is for people to get swept up in movements. How quickly agency can be taken away. And how recklessly people can fight to reclaim that agency.

In Joker, Fleck is entirely without agency. He can’t control his random outbursts of laughter, he can’t make himself understood to his stand-up audiences and even as he begins to embrace his Joker identity, many of the systemic impacts of his actions aren’t through his design. When Fleck does try to seize some agency over his life, he – like the lower-class Gothamites who burn their city in violent riots – does so recklessly, callously and irresponsibly.

Zooming out to the discourse around the film, you can see life mirroring art. Audiences have been systematically deprived of the agency they need to form their own views around the film.

This happened well before the first trailer dropped. Arguably, it began with the rise of comic book movies more generally.

We live in an age where it’s easy to treat films as just another form of content. Just like we binge through streaming services and mindlessly scroll social media feed, we can let films wash over us without ever actively engaging with the material. Sure, we follow the plot and might have a view on whether we enjoyed the film or not, but that’s not the same as allowing a film (or a series, or whatever) to make us think.

The comic book movie is the embodiment of this trend. The heroes and villains are mapped out in advance. We know what will happen and we watch to find out how it will happen. Consider Avengers: Endgame. We knew Thanos would be defeated and that the heroes who had been snapped out of existence would return – after all, a bunch of them already had sequels in the calendar. There’s no moral ambiguity; just a good story.

Of course, that’s fine. The Marvel Cinematic Universe makes up for in fun what it lacks in moral complexity. But Joker is different. Despite appearing in the guise of a comic book film, it’s not a comic book movie at all. It didn’t need to be about the rise of The Joker. What that’s highlighted is how a generation raised on comic book movies have been left unprepared to engage with a film so rife with complexity.

Many are still trying to do so. Like Immanuel Kant encouraged in ‘What is Enlightment?’, they’re daring to think for themselves. Kant saw this enlightenment as liberating – a freedom from intellectual immaturity. But it might also be reckless – particularly if it ends up with people decided that Warner Bros are wrong and Fleck is the hero of the story.

But the best way to guard against this isn’t to avoid films like Joker, or to be too heavy-handed in how people interpret the film. It’s to create more space in our content consumption for things that are more than just fairy floss for our brains. To put the Iron Mans and Flashes of the world in their proper place and find some balance so that we can enjoy the fun for what it is without dulling our senses when something more complex comes along.

The Ethics Centre is presenting a panel discussion on The Ethics of Art and Violence at the MCA on 12 February. Tickets on sale now. For further information click here.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Why listening to people we disagree with can expand our worldview

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

The wonders, woes, and wipeouts of weddings

Big thinker

Relationships

Big Thinker: Kate Manne

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights, Society + Culture

Drawing a line on corruption: Operation eclipse submission

BY Matthew Beard

Matt is a moral philosopher with a background in applied and military ethics. In 2016, Matt won the Australasian Association of Philosophy prize for media engagement. Formerly a fellow at The Ethics Centre, Matt is currently host on ABC’s Short & Curly podcast and the Vincent Fairfax Fellowship Program Director.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

To fix the problem of deepfakes we must treat the cause, not the symptoms

To fix the problem of deepfakes we must treat the cause, not the symptoms

Opinion + AnalysisRelationshipsScience + Technology

BY Matthew Beard The Ethics Centre 5 DEC 2019

This article was written for, and first published by The Guardian. Republished with permission.

Once technology is released, it’s like herding cats. Why do we continue to let the tech sector manage its own mess?

We haven’t yet seen a clear frontrunner emerge as the Democratic candidate for the 2020 US election. But I’ve been interested in another race – the race to see which buzzword is going to be a pivotal issue in political reporting, hot takes and the general political introspection that elections bring. In 2016 it was “fake news”. “Deepfake” is shoring up as one of the leading candidates for 2020.

This week the US House of Representatives intelligence committee asked Facebook, Twitter and Google what they were planning to do to combat deepfakes in the 2020 election. And it’s a fair question. With a bit of work, deepfakes could be convincing and misleading enough to make fake news look like child’s play.

Deepfake, a portmanteau of “deep learning” and “fake”, refers to AI software that can superimpose a digital composite face on to an existing video (and sometimes audio) of a person.

The term first rose to prominence when Motherboard reported on a Reddit user who was using AI to superimpose the faces of film stars on to existing porn videos, creating (with varying degrees of realness) porn starring Emma Watson, Gal Gadot, Scarlett Johansson and an array of other female celebrities.

However, there are also a range of political possibilities. Filmmaker Jordan Peele highlighted some of the harmful potential in an eerie video produced with Buzzfeed, in which he literally puts his words in Barack Obama’s mouth. Satisfying or not, hearing Obama call US president Trump a “total and complete dipshit” is concerning, given he never said it.

Just as concerning as the potential for deepfakes to be abused is that tech platforms are struggling to deal with them. For one thing, their content moderation issues are well documented. Most recently, a doctored video of Nancy Pelosi, slowed and pitch-edited to make her appear drunk, was tweeted by Trump. Twitter did not remove the video, YouTube did, and Facebook de-ranked it in the news feed.

For another, they have already tried, and failed, to moderate deepfakes. In a laudably fast response to the non-consensual pornographic deepfakes, Twitter, Gfycat, Pornhub and other platforms quickly acted to remove them and develop technology to help them do it.

However, once technology is released it’s like herding cats. Deepfakes are a moving feast and as soon as moderators find a way of detecting them, people will find a workaround.

But while there are important questions about how to deal with deepfakes, we’re making a mistake by siloing it off from broader questions and looking for exclusively technological solutions. We made the same mistake with fake news, where the prime offender was seen to be tech platforms rather than the politicians and journalists who had created an environment where lies could flourish.

The furore over deepfakes is a microcosm for the larger social discussion about the ethics of technology. It’s pretty clear the software shouldn’t have been developed and has led – and will continue to lead – to disproportionately more harm than good. And the lesson wasn’t learned. Recently the creator of an app called “DeepNude”, designed to give a realistic approximation of how a woman would look naked based on a clothed image, cancelled the launch fearing “the probability that people will misuse it is too high”.

What the legitimate use for this app is, I don’t know, but the response is revealing in how predictable it is. Reporting triggers some level of public outcry, at which suddenly tech developers realise the error of their ways. Theirs is the conscience of hindsight: feeling bad after the fact rather than proactively looking for ways to advance the common good, treat people fairly and minimise potential harm. By now we should know better and expect more.

“Technology is a way of seeing the world. It’s a kind of promise – that we can bring the world under our control and bend it to our will.”

Why then do we continue to let the tech sector manage its own mess? Partly it’s because it is difficult, but it’s also because we’re still addicted to the promise of technology even as we come to criticise it. Technology is a way of seeing the world. It’s a kind of promise – that we can bring the world under our control and bend it to our will. Deepfakes afford us the ability to manipulate a person’s image. We can make them speak and move as we please, with a ready-made, if weak, moral defence: “No people were harmed in the making of this deepfake.”

But in asking for a technological fix to deepfakes, we’re fuelling the same logic that brought us here. Want to solve Silicon Valley? There’s an app for that! Eventually, maybe, that app will work. But we’re still treating the symptoms, not the cause.

The discussion around ethics and regulation in technology needs to expand to include more existential questions. How should we respond to the promises of technology? Do we really want the world to be completely under our control? What are the moral costs of doing this? What does it mean to see every unfulfilled desire as something that can be solved with an app?

Yes, we need to think about the bad actors who are going to use technology to manipulate, harm and abuse. We need to consider the now obvious fact that if a technology exists, someone is going to use it to optimise their orgasms. But we also need to consider what it means when the only place we can turn to solve the problems of technology is itself technological.

Big tech firms have an enormous set of moral and political responsibilities and it’s good they’re being asked to live up to them. An industry-wide commitment to basic legal standards, significant regulation and technological ethics will go a long way to solving the immediate harms of bad tech design. But it won’t get us out of the technological paradigm we seem to be stuck in. For that we don’t just need tech developers to read some moral philosophy. We need our politicians and citizens to do the same.

“At the moment we’re dancing around the edges of the issue, playing whack-a-mole as new technologies arise.”

At the moment we’re dancing around the edges of the issue, playing whack-a-mole as new technologies arise. We treat tech design and development like it’s inevitable. As a result, we aim to minimise risks rather than look more deeply at the values, goals and moral commitments built into the technology. As well as asking how we stop deepfakes, we need to ask why someone thought they’d be a good idea to begin with. There’s no app for that.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Should parents tell kids the truth about Santa?

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

In two minds: Why we need to embrace the good and bad in everything

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships, Society + Culture

The sticky ethics of protests in a pandemic

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships

The transformative power of praise

BY Matthew Beard

Matt is a moral philosopher with a background in applied and military ethics. In 2016, Matt won the Australasian Association of Philosophy prize for media engagement. Formerly a fellow at The Ethics Centre, Matt is currently host on ABC’s Short & Curly podcast and the Vincent Fairfax Fellowship Program Director.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Beyond the headlines of the Westpac breaches

Beyond the headlines of the Westpac breaches

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + LeadershipRelationships

BY Simon Longstaff The Ethics Centre 28 NOV 2019

As I look back on the week of turmoil that has engulfed Westpac, my overwhelming feeling is one of sadness.

I am sad for the children whose lives may have been savaged by sexual predators using the bank’s faulty systems. I am sad for the tens of thousands of Westpac employees who may feel tainted by association with the bank’s failings. I am sad for individuals, like Brian Hartzer and Lindsay Maxsted, whom I believe will be remembered more for the manner of their parting from the bank than for all the good that they did along the way. All of them deserve better.

None of this lessens my judgement about the seriousness of the faults identified by Austrac. Nor is sadness a reason for limiting the adverse consequences borne by individuals and the company.

Rather, in the pell-mell of the moment – super-charged by media and politicians enjoying a ‘gotcha’ moment – it is easy to forget the human dimension of what has occurred – whether it be the impact on the victims of sexual exploitation or the person whose pride in their employer has been dented.

Behind the headlines, beyond the outrage, there are people whose lives are in turmoil. Some are very powerful. Some are amongst the most vulnerable in the world. They are united by the fact that they are all hurt by failures of this magnitude.

For Westpac’s part, the company has not sought to downplay the seriousness of what has occurred. There has not been any deflection of blame. There has been no attempt to bury the truth. If anything, the bank’s commitment to a thorough investigation of underlying causes has worked to its disadvantage – especially in a world that demands that the acceptance of responsibility be immediate and consequential.

The issue of responsibility has two dimensions in this particular case: one particular to Westpac and the other more general. First, there are some people who are revelling in Westpac’s fall from grace. Many in this group oppose Westpac’s consistently progressive position on issues like sustainability, Indigenous affairs, etc. Some take particular delight in seeing the virtuous stumble. However, this relatively small group is dwarfed by the vast number of people who engage with the second dimension – the sense that we have passed beyond the days of responsible leadership of any kind.

I suspect that Westpac and its leadership are part of the ‘collateral damage’ caused by the destruction of public trust in institutions and leadership more generally.

When was the last time a government minister, of any party in any Australian government, resigned because of a failure in their department? Why are business leaders responsible for everything good done by a company – but never any of its failures?

Some people think that the general public doesn’t notice this … or that they do not care. They’re wrong on both counts. I suspect that the general public has had a gut-full of the hypocrisy. They want to know why the powerless constantly being held to account while the powerful escape all sanction?

I think that this is the fuel that fed the searing heat applied to Westpac and its leadership earlier this week. The issues in Westpac were always going to invite criticism but this was amplified by a certain schadenfreude amongst Westpac’s critics and the general public’s anger at leaders who refuse to accept responsibility.

So, what are we to make of this?

One of the lessons that people should keep in mind when they volunteer for a leadership role is that strategic leaders are always responsible; even when they are not personally culpable for what goes wrong on their watch. This is not fair. It’s not fair that a government minister be presumed to know of everything that is going on in their department. It’s not fair to expect company directors or executives to know all that is done in their name. It is not fair.

However, it is necessary that this completely unrealistic expectation, this ‘fiction’, be maintained and that leaders act as if it were true. Otherwise, the governance of complex organisations and institutions will collapse. Then things that are far worse than our necessary fictions will emerge to fill the void; the grim alternatives of anarchy or autocracy.

It’s sad that we have come to a point where this even needs to be said.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Violent porn and feminism

Explainer

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Critical Race Theory

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Why learning to be a good friend matters

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership