Ethics Explainer: Conscience

Conscience describes two things – what a person believes is right and how a person decides what is right. More than just ‘gut instinct’, our conscience is a ‘moral muscle’.

By informing us of our values and principles, it becomes the standard we use to judge whether or not our actions are ethical.

We can call these two roles ethical awareness and ethical decision making.

Ethical Awareness

This is our ability to recognise ethical values and principles.

The medieval philosopher Thomas Aquinas believed our conscience emerged from synderesis: the ‘spark of conscience’. He literally meant the human mind’s ability to understand the world in moral terms. Conscience was the process by which a person brought the principles of synderesis into a practical situation through our decisions.

Ethical Decision Making

This is our ability to make practical decisions informed by ethical values and principles.

In his writings, Aristotle described phronesis: the goodness of practical reason. This was the ability to evaluate a situation clearly so we would know how to act virtuously under the circumstances.

A conscience which is both well formed (shaped by education and experience) and well informed (aware of facts, evidence and so on) enables us to know ourselves and our world and act accordingly.

Seeing conscience in this way is important because it teaches us ethics is not innate. By continuously working to understand our surroundings, we strengthen our moral muscle.

Conscientious Objection

In politics, much of the debate around conscience concerns the “right to conscientious objection”.

- Should pro-life doctors be required to perform abortions or refer patients to doctors who will?

- Must priests break the confessional seal and report sex offenders who confess to them?

- Can pacifists be excused from conscription because of their opposition to war?

For a long time, Western nations, informed by the Catholic intellectual tradition, believed in the “primacy of conscience” – the idea that a person should never be forced to do something they believe is against their most deeply held values and principles.

In recent times, particularly in medicine, this has come to be questioned. Australian bioethicist Julian Savulescu believes doctors working in the public system should be banned from objecting to procedures because it compromises patient care.

This debate sees a clash between two worldviews – one where people’s foremost responsibility is to their own personal beliefs about what is good and right and another where this duty is balanced against the needs of the common good.

Philosopher Michael Walzer believes there are situations where you have a duty to “get your hands dirty” – even if the price is your own sense of goodness. In response, Aristotle might have said, “no person wishes to possess the world if they must first become someone else”. That is, we can’t change who we are or what we believe in for any price.

Recommended viewing

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Explainer

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Critical Race Theory

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

But how do you know? Hijack and the ethics of risk

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

The problem with Australian identity

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

The historical struggle at the heart of Hanukkah

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Ethics Explainer: Progressivism

Progressivism is a political ideology based on the possibility of moral progress. In practice, this looks like an optimism about the future of humanity.

Progressives believe the course of human history is moving us closer to a state of peace, equality, and prosperity. They also tend to believe in human perfectibility. Politics, technology, and education can overcome human failings to create a utopia.

We can see this in the work of philosophers Steven Pinker and Michael Shermer. Pinker says since the Enlightenment, altruism has been on the rise and violence is declining around the world. Shermer suggests each generation has been smarter than the last, which he believes, has continually reduced impulsive violence.

Hegel’s synthesis

German philosopher Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel believed moral progress was inescapable. He thought the forces of history shape humanity for the better, pushing it toward perfection.

Hegel believed history unrolled according to a “dialectical” pattern. This was where opposing sides clashed and compromised with one another. These opposing forces, which he called the “thesis” and “antithesis”, would clash before reaching a “synthesis”.

This synthesis would then spark a new antithesis and the process would continue. Hegel thought each stage in the thesis-antithesis-synthesis series moved us closer to a state of perfection. His work is said to have inspired other progressive thinkers, most notably communist philosopher Karl Marx.

The darker side of progress

Today, new forms of genetic editing promise a cure to a range of illnesses and maybe even death itself. Transhumanists believe we can overcome the limitations of our humanity and mortality. They suggest a range of options, from changing our biology to uploading our consciousness into a supercomputer.

But practical efforts to create this perfect world have not always been pleasant. At times it has been outright barbaric.

One example is the eugenics movement. It aimed to breed some people, like those with disabilities, out of society altogether, and cited social progress as their defence.

This is one reason why conservatives often urge caution around progress. They encourage us to be mindful of the potential unintended side effects of new policies or technology.

But progressives are often concerned this will inhibit life changing new developments. They suggest we deal with issues as they arise, rather than trying to predict them in advance.

Heaven on earth

Progressives often see education as the silver bullet solution for social problems. Like Ancient Greek philosopher Socrates, they tend to believe all vice is the result of ignorance, not malice. They suggest humans are fundamentally good and education will bring out the better angels of our nature.

But some are sceptical whether education alone will fix all humanity’s woes. They agree humans are mostly good but don’t blame ignorance for evil. Instead, they see war, conflict and violence as the product of oppression and inequality.

Karl Marx believed conflict between the wealthy and the working class was a central theme in human society. He believed the power imbalance between rich and poor was bad for everyone. He famously claimed people would be better throwing away hierarchies based on class and wealth. Only when we’re all equal, he thought, will we be able to perfect ourselves.

English philosopher Mary Wollstonecraft suggested the path to human perfection might require both politics and education. She argued that political change requires us to educate marginalised groups. Otherwise, any change will continue to exclude the groups already on the fringes of society.

This explains why more women and culturally diverse people have contributed to progressive thinking in recent decades. In the past, the leading progressive thinkers tended to be white men. Improved access to education has enabled a greater range of voices to contribute to the larger conversation of what a perfect world might look like and how we could create it.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

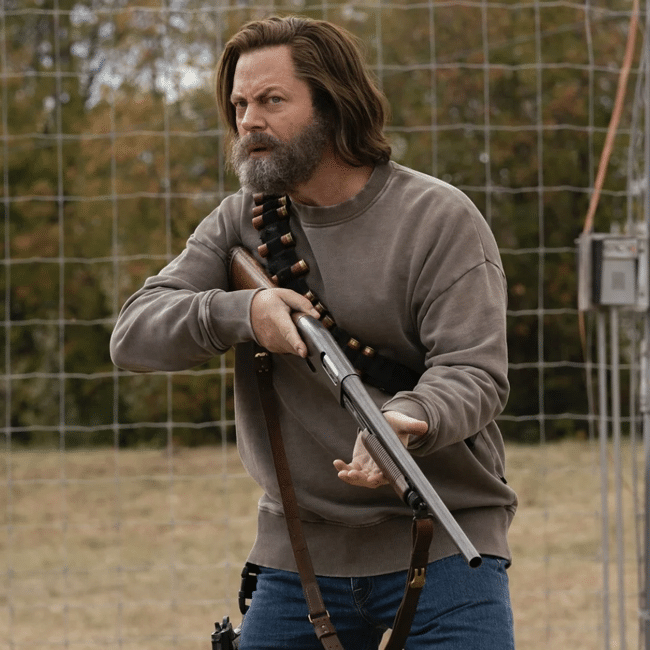

Bring back the anti-hero: The strange case of depiction and endorsement

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships, Society + Culture

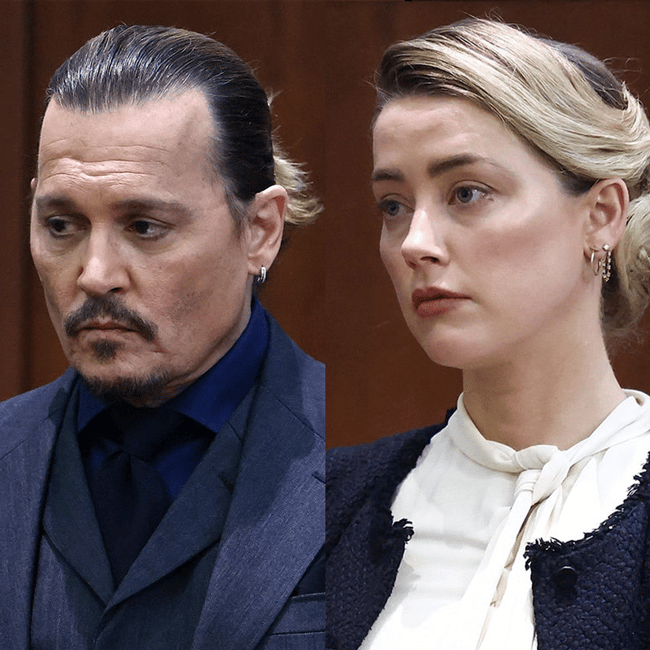

You won’t be able to tell whether Depp or Heard are lying by watching their faces

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships, Society + Culture

Punching up: Who does it serve?

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

James Hird In Conversation Q&A

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Big Thinker: Socrates

Socrates (470 BCE—399 BCE) is widely considered to be one of the founders of Western philosophy.

Stonemason, soldier, citizen, philosophy’s first ‘martyr’, Socrates helped shape one of the major intellectual foundations on which Western civilisation has been built. Yet, no work of philosophy bears his name as the author. All we know of him is derived from the work of others – especially Plato, Xenophon and Aristophanes.

The rise of ethics

Prior to Socrates, ancient philosophy tended to focus on questions that today might be considered the domain of physics. ‘Pre-Socratic’ philosophers tended to focus on fundamental questions about the nature of the universe – like the building blocks of matter or the nature of time and motion.

When Socrates came along, he proposed a completely different set of questions for philosophical deliberation. He drew attention away from questions about how the world is and towards questions about how we are to be in the world. While he made valuable contributions to the evolution of thought about epistemology and politics, it is this turn toward ethics that introduced a fresh practical dimension to philosophy.

Earlier philosophical debates of Thales, Anaximander and Democritus, for example, were all theoretical. Human knowledge and understanding might have advanced, but nothing in the world was directly changed by their deliberations.

Socrates’ focus on ethics was intended to generate practical outcomes. He expected philosophical work might lead to a change in both attitudes and (importantly) actions of people. In turn, this was intended to produce effects in the world. Although we have only come to see Socrates through the eyes of others, his friends (like Plato and Xenophon) and foes (like Aristophanes) agree he wished to have an impact on the people around him and the kind of society they were creating as a result of their choices.

What friends and foes disagreed on was Socrates’ motivation. His critics lumped him in with the Sophists who were looked down on as philosophical guns for hire.

A new focus on ethics repositioned philosophy as something relevant to everyday life. Socrates’ core question, ‘What ought one to do?’ does not apply in a limited set of circumstances. It is a question of general application to any situation where a choice is to be exercised – and is applicable to every person, whatever their station in life.

In some sense, this is what made Socrates such a troublesome – or dangerous – person. In one fell swoop, he brought philosophy into the agora (the marketplace), making it relevant and accessible to people of all ages and degrees.

This upset hierarchies and orthodoxies. As we know, a gadfly is rarely welcome. Socrates was eventually executed for crimes of ‘impiety’ and ‘corrupting the youth’ – in short, for teaching and encouraging them to question established norms and think for themselves.

The virtue of ‘constructive ignorance’

On being asked who the wisest person in Athens was, the Oracle of Delphi nominated Socrates. Socrates was astounded – he believed himself to know nothing. To prove his relative ignorance, Socrates sought to find wiser folk amongst the citizens of Athens, questioning them at length about the nature of things like justice and love.

His questioning had practical implications. At that time in democratic Athens, citizens were actively involved in enacting laws or judgements in the courts.

In the end, Socrates came to believe the Oracle of Delphi was correct – but only because his superior wisdom lay in his realising the limits of his knowledge.

Along the way to this realisation, Socrates developed the process of elenchus (the ‘Socratic method’). It is a distinctive form of questioning designed to open space for insight and self-knowledge. The idea we have much to learn about ourselves and the world might suggest we are ignorant. Such a view could position the Socratic method of questioning as a mean spirited exercise. Those subjected to it did not necessarily enjoy the experience or see it in a positive light. This no doubt contributed to the belief Socrates was an impious trouble maker.

The importance of the examined life

Although Socrates contributed many insights that are still drawn upon today (but not necessarily accepted), one of his most famous and profound is his claim that ‘the unexamined life is not worth living’.

This claim goes beyond being a recommendation we should think before we act – which may be a prudent thing to do. Socrates is attempting to draw our attention to a deeper truth about the human condition. He encourages us to participate in a form of being that has the capacity to transcend the requirements of instinct and desire in order to make conscious – that is, ethical – choices. Socrates claimed if we fail to do this, we live a lesser life.

One of the effects of examination is, according to Socrates, the development of phronesis (practical wisdom) which is the foundation for virtue. For Socrates (and later for Aristotle – in a slightly different form), the possession of virtue is not just a matter of interior orientation. It is essential to being able to see the world as it is and be able to make good decisions.

Like Aristotle, Socrates sees vice as the source of defective vision. Socrates thought people make bad choices and do bad things out of ignorance. He thought if people could only ‘see’ what is good, they would choose it.

This all finally comes together in the way Socrates challenged the status quo. To live an examined life is to reject things ought to be done just because they have always been done.

Instead, Socrates is an early exponent of an inner voice that (in Socrates’ case) is supposed to have warned him against making an error. Socrates called this voice his ‘daimōnic sign’ – something Aquinas would call ‘conscience’ over a thousand years later.

It may be difficult to distinguish the real Socrates from the versions of the man created by others – which were either celebratory or lampooning. But this we know. When given the chance to escape and avoid the sentence of death imposed on him by the Athenians, Socrates chose to stay. In defence of his ideas and in conformance with his ideals Socrates drank the hemlock and died.

He can hardly have imagined the impact he would have on the world.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

The philosophy of Virginia Woolf

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Paralympian pay vs. Olympian pay

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

The ethics of friendships: Are our values reflected in the people we spend time with?

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture

The art of appropriation

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

The pivot: Mopping up after a boss from hell

The pivot: Mopping up after a boss from hell

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + LeadershipRelationships

BY Rhonda Brighton Hall The Ethics Centre 10 OCT 2017

How would you feel if you had been harassed on an internet dating site and blocked the person, only to turn up for a new job and find out that they’re your boss?

It gets worse. The harassment continued outside of work and then the new boss started “performance managing” the employee out of the business, making complaints about the quality of their work.

This actually happened and I found out about it when the mother of the victim phoned me (as a HR executive) to say, “This is what happened to my son in your business”.

The young man, who we shall call Darren, had been an ambitious high performer. But, after a 12-week period with his new boss, he resigned – blowing up his career to escape the situation.

Now, he was seriously depressed, could not get out of bed and his mother was very concerned about his mental wellbeing.

There was some conjecture it may not have been a coincidence that the harasser had turned up as his boss. He may have deliberately sought to connect with his new team outside work before starting in the job.

The path forward was not totally clear. Darren had not made a complaint himself. It was his mother who made the call and supplied me with screenshots of text messages, without Darren’s consent.

He had also already left the company, but was obviously in a very bad space. Also, if he had resigned because of the harassment, it could potentially be regarded as “constructive dismissal” (an unlawful termination of employment).

And I now had someone working in the business who had apparently been a harasser on social media and had forced his victim out of his job. You don’t want a leader who performance manages people who won’t date them, or even someone who allows that perception to take hold.

It had to be investigated because, if it was true, I couldn’t just leave it as a time bomb waiting for the next person to attract his interest.

My legal and moral obligations were not necessarily the same. I had to respond to the situation as both a HR person and a leader, because I had executive responsibility for the part of the business they both worked in.

From a moral perspective, I had to consider whether my response was an almost parental reaction. Had I wanted to protect an employee who I discovered had been harassed out of his job because a complaint came from his mother?

It was a tricky situation, but we went through a quiet investigative process. I contacted Darren and he didn’t want to come back to the company.

The really important lesson in dealing with cases such as these is to discuss the human impact at the same time that you are discussing the legalities. They need to come together, they can’t be separated.

I arranged for better support and counselling for him. That was a risk because, in a court case, it could have been construed as an admission of responsibility and it could have gone on to become a Workers’ Compensation or Human Rights Discrimination issue.

But there must be a degree of humanity – you can’t just leave someone broken and walk on by.

When I called his former boss into an interview, he became very angry. He said his activity on the dating site was his private life and none of our business.

A mature leader would have disclosed the conflict in their relationship as soon as they started at the company, so that it could be managed ethically. Instead, he went for Darren, hammer and tongs with the performance issue.

We disciplined him and he ended up resigning shortly afterwards of his own free will.

The really important lesson in dealing with cases such as these is to discuss the human impact at the same time that you are discussing the legalities. They need to come together, they can’t be separated.

It is also important to deal quickly with these things because nothing gets better if it festers away. If I look at the really bad cases I have mopped up, there have been a lack of investigative outcomes, a lack of definitive decisions and/or lack of clarity about what will be done.

Some of these cases drag on for years and someone leaves the workforce, broken. They progressively end up in really bad financial shape as well. Time stands still for them because they are either coming into a workplace where someone is continuing to harass them or they are isolated at home. While you’re deciding what to do, the issue is overwhelming their every day.

This article was originally written for The Ethics Alliance. Find out more about this corporate membership program. Already a member? Log in to the membership portal for more content and tools here.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

The self and the other: Squid Game’s ultimate choice

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

6 Myths about diversity for employers to watch

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

Inside The Mind Of FODI Festival Director Danielle Harvey

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

Yellowjackets and the way we hunger

BY Rhonda Brighton Hall

Rhonda Brighton-Hall is a non-executive director of the Australian Human Resources Institute and founder of MWAH (Make Work Absolutely Human), Chair of FlexCareers, Former Telstra Business Woman of the Year and HR Leader of the Year.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Big Thinker: Dennis Altman

Big Thinker: Dennis Altman

Big thinkerPolitics + Human RightsRelationships

BY Kym Middleton The Ethics Centre 28 SEP 2017

Dennis Altman (1943—present) is an internationally renowned queer theorist, Australian professor of politics and current Professorial Fellow at La Trobe University.

Beginning his intellectual career in the 1970s, his impact on queer thinking and gay liberation can be likened to Germaine Greer’s contributions to the women’s movement.

Much of Altman’s work explores the differences between gay radical activists who question heteronormative social structures like marriage and nuclear family, and gay equality activists who want the same access to such structures.

“Young queers today are caught up in the same dilemma that confronted the founders of the gay and lesbian movements: Do we want to demonstrate that we are just like everyone else, or do we want to build alternatives to the dominant sexual and emotional patterns?”

Divided in diversity, united in oppression

Altman’s influential contribution to gay rights began with his first of many books, Homosexual: Oppression and Liberation. The 1971 text has been published in several countries and is still widely read today. It is often regarded as an uncannily correct prediction of how gay rights would improve over the decades – something that would have been difficult to imagine when the first Sydney Mardi Gras was met with police violence.

Altman predicted homosexuality would become normalised and accepted over time. As oppressions ceased, and liberation was realised, sexual identities would become less important and the divisions between homosexual and heterosexual would erode. Eventually, openly gay people would come to be defined the way straight people were – by characteristics other than their sexuality like their job, achievements or interests.

Despite gay communities being home to diversity and division, the shared experience of discrimination bonded them, Altman argued. Much like women’s and black civil rights advocates could testify, oppression has an upside – it forms communities.

End of the homosexual?

Altman’s 2013 book The End of the Homosexual? follows on from the ideas in his first. It is often described as a sequel despite the 40 years and several other publications between the two. He wrote it at a time when same sex marriage was beginning to be legalised around the world.

Altman recently reflected on his old work and said he was wrong to believe identity would become less important as acceptance grew but right to predict being gay would not be people’s defining characteristic.

He has come across as both happy and disappointed by the normalisation of same sex relationships. While massive reductions in violence and systemic discrimination is something you can only celebrate, Altman almost mourns the loss of the radical roots of gay liberation that formed in response to such injustices.

Without the oppressions of yesteryear, what binds diverse people into gay communities today? What distinguishes between a ‘gay lifestyle’ and a ‘straight lifestyle’ when they share so many characteristics like marriage, children, and general social acceptance?

Of course, all things are still not equal today. While people in the West largely enjoy safety and equality, people in countries like Russia are experiencing regressions. Altman hopes gay liberationists could have impact there.

Same sex marriage

Although he’s considered a pioneer in queer theory, a field that questions dominant heterosexual social structures, Altman does not support same sex marriage.

Some people might feel a sense of betrayal that such a well respected gay public intellectual has not put his influence behind this campaign. But Altman’s lack of support is completely consistent with the thinking he has been sharing for decades. Like a radical women’s liberationist, he has reservations about marriage itself – whether it’s same sex or opposite sex.

Altman takes issue with traditional marriage’s “assumption that there is only one way of living a life”. He has long been concerned the positioning of wedlock as the norm forgets all the people who are not living in long term, monogamous relationships. He argues marriage isn’t even all that normal in Australia anymore with single person households growing faster than any other category.

Altman was with his spouse for 20 years until death parted them. While that may sound like a marriage, the role of state and Church deeply bothers him, and so they were together without the blessings of those institutions. He has expressed confusion over the popular desire to be approved by the state or religious bodies that do not want to sanction same sex relationships. It’s because he doesn’t consider same sex marriage a human rights issue, when compared to things like starvation, oppression, and other forms of suffering.

Nevertheless, Altman recognises the importance of equal rights and understands why marriage for heterosexuals and not homosexuals is unfair. True to form he continues to question the institution itself by flipping the marriage equality argument on its head. He advocates for “the equal right not to marry”.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

In defence of platonic romance

Opinion + Analysis

Climate + Environment, Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

The dilemma of ethical consumption: how much are your ethics worth to you?

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

Unrealistic: The ethics of Trump’s foreign policy

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture, Politics + Human Rights

Pleasure without justice: Why we need to reimagine the good life

BY Kym Middleton

Former Head of Editorial & Events at TEC, Kym Middleton is a freelance writer, artistic producer, and multi award winning journalist with a background in long form TV, breaking news and digital documentary. Twitter @kymmidd

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Ethics Explainer: Respect

The concept of respect arises in two major forms. We’ll call them respect (lite) and respect (full).

Respect (lite)

Respect (lite) is in play when being polite, considerate and mindful of another person. It can also be demanded from another as a mark of deference to their rank, seniority, experience or standing in the world. We see it in statements like: “respect your elders”, “show a little respect”, or “with all due respect”.

It tends to be allied to the claim that respect is best earned rather than demanded. However, the idea that respect (lite) needs to be earned is one of the most important ways of distinguishing the ‘lite’ concept from the ‘full’ form.

Respect (full)

Respect for persons may perhaps be the most fundamental principle in all of ethics. Respect (full) calls on each and every one of us to respect the intrinsic dignity of all other people. If something is intrinsic to us, it is essential to our being and cannot be earned. It is a property of being a person.

The source of intrinsic dignity has varied over time and across cultures. For example, within Judaism, Christianity and Islam (at least), the intrinsic dignity of persons comes from being made in the image of God. In each of these traditions, the image isn’t literal. Rather, the reference is to being made in the ‘moral image’ of God – and most importantly, being endowed with free will.

There are also secular sources of personhood. Perhaps most famous is Immanuel Kant’s linking of personhood and intrinsic dignity to our rationality. This quality of ours means we all belong to what Kant calls the ‘Kingdom of Ends’.

‘The Kingdom of Ends’ is a thought experiment Kant created in which all human beings are treated as ends (where they and their wellbeing are the goal), and not as a “means to an end” (where the benefit of others is the goal). You’ve probably heard someone say, “My job is a means to an end”, meaning they don’t care much for their work but do care about the rent, family or travel their work pays for.

Having made a distinction between means and ends, Kant goes on to say a person should never be used as a means. Unsurprisingly he had a prohibition against slavery, the ancient institution where people become the property of someone else who uses them as a tool for their own benefit.

Respect (full) is what we count on as the source of principled opposition to all forms of discrimination against persons – whether it be because of age, gender, sexuality, race, religion… whatever.

Joining the two ideas together

These two versions of respect are clearly related. It is just that we tend to lose sight of the connection. Polite, respectful debate about contentious issues is not just about avoiding harmful consequences. It can (and should) go deeper – right back to recognition of the intrinsic dignity of others.

That is ultimately the reason why we should listen to their opinion. It is why we should attack the arguments and not the person. It is why we should refrain from insulting, bullying, silencing or oppressing others even if we fundamentally disagree with them.

Of course, civilised and principled disagreement can help avoid matters getting out of hand when tempers fray. But safer, better forms of deliberation are collateral benefit of acting on the principle of respect for persons – and acknowledging their intrinsic dignity – even when we are opposing them.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis, READ

Society + Culture, Relationships

Losing the thread: How social media shapes us

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Politics + Human Rights

How to have a difficult conversation about war

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

Five dangerous ideas to ponder over the break

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

The ‘good ones’ aren’t always kind

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Assisted dying: 5 things to think about

Assisted dying: 5 things to think about

Opinion + AnalysisPolitics + Human RightsRelationships

BY The Ethics Centre 24 AUG 2017

Making sense of our lives means thinking about death. Some philosophers, like Martin Heidegger and Albert Camus, thought death was a crucial, defining aspect of our humanity.

Camus went so far as to say considering whether to kill oneself was the only real philosophical question.

What these philosophers understood was that the philosophical dream of living a meaningful life includes the question of what a meaningful death looks like, too. More deeply, they encourage us to see that life and death aren’t opposed to one another: dying is a part of life. After all, we’re still alive when we’re dying so how we die impacts how we live.

The Ethics Centre was invited to make a submission to the NSW Parliamentary Group on Assisted Dying regarding a draft bill the parliament will debate soon. The questions we raised were in the spirit of connecting the good life to a good death.

Simon Longstaff, director of the Centre and author of the submission, writes, “It is not the role of The Ethics Centre to prescribe how people ought to decide and act. Our task is a more modest one – to set out some of the ethical considerations a person might wish to take into account when forming a view.”

Here are some of the key issues we explored, which are relevant to any discussion of assisted dying, not just the NSW Bill.

Does a good life involve suffering?

The most common justification for assisted dying or euthanasia is to alleviate unbearable suffering. This is based in a fairly universal sentiment. Longstaff writes, “To our knowledge, there is no religion, philosophical tradition or culture that prizes suffering … as an intrinsic good”.

Good things can come as a result of suffering. For example, you might develop perseverance or be supported by family. But the suffering itself is still bad. This, Longstaff argues, means “suffering is generally an evil to be avoided”.

There are two things to keep in mind here.

First, not all pain is suffering. Suffering is a product of the way we interpret ourselves and the world around us. Whether pain causes suffering depends on our response: It’s a subjective experience. Nobody but the sufferer can really determine the extent of their suffering. Recognising this could suggest a patient’s self-determination is crucial to decisions around assisted dying.

Second, just because suffering is generally a bad thing doesn’t mean that anything aiming to avoid it is good. We can agree that the goal of reducing suffering is probably good but still need to interrogate whether the method we’ve chosen to reduce suffering is itself ethical.

The connection between a good death and a good life

There’s not always a solution to suffering, no matter what anecdote you try, whether it be medicine, psychology, religion or philosophy. Sometimes suffering stays a while.

When there is no avenue to alleviate someone’s pain and anguish, Longstaff suggests “life can be experienced … as nothing more than an unrelenting and extra-ordinary burden”.

This is the context in which we should consider whether to help someone to end their lives or not. Although many faiths and beliefs affirm the importance and sacredness of life, if we’re thinking about a good, meaningful life, we need to pay some attention to whether life is actually of any value to the person living it. As Longstaff writes, “To say that life has value regardless of the conditions of a person’s existence may justify the continuation or glorification of lives that could be best described as a ‘living hell’”.

He continues, “To cause such a state would be indefensible. To allow it to persist without available relief is to act without mercy or compassion. To set aside those virtues is to deny what is best in our form of being.”

A responsible person should have autonomy over their death

Most people think it’s important for adults to be held responsible for their actions. Philosophers think this is a product of autonomy – the ability for people to determine the course of their own actions and lives.

Some philosophers think autonomy has an intrinsic connection to dignity. What makes humans special is their ability to make free choices and decisions. What’s more, we usually think it’s wrong to do things that undermine the free, autonomous choices of another person.

If we see death as a part of life, not distinct from it, it seems like we should allow – even expect – people to be responsible for their deaths. As Longstaff writes, “since dying is a part of life, the choices people make about the manner of their dying are central considerations in taking full responsibility for their lives”.

The role of the terminal disease

Some proposed laws, like the draft NSW Bill, suggest a person can seek to end their own life when their terminal disease causes them unbearable suffering. So, if you’re dying of lung cancer, you can only end your life if the cancer itself is causing you unbearable pain. It is necessary to consider if assisted dying be restricted in this way.

Imagine you’ve got a month to live and the only thing that gives you meaning is your ability to go outside and watch the sunrise. One day, you break your leg and are bedridden. Should you now be forced to live for a month in a state you find agonising and meaningless because your broken leg isn’t what’s killing you?

Longstaff argues, “If severe pain and suffering are essential criteria for being eligible for assistance, then on the basis that like cases should be treated in a like manner, assistance should be offered to a person who meets all the other specified criteria – even if their pain and suffering is not caused by their illness”.

Who is eligible for assisted dying?

Many laws try to carve out special categories of people who are and aren’t eligible to request assisted dying. They might do so on the basis of life expectancy, whether the illness is terminal or the age of the patient.

In determining who should be eligible, two principles are worth thinking about.

First, the principle of just access to medical care. Most bioethicists agree before we can figure out who receives medical treatment, we need to have a broader idea of what justice looks like.

Some think justice means people get what they need. For these people, granting medical care is based on how urgently it’s required. Others think justice means getting the best outcome. These people think we should distribute medicine in a way that creates the most quality of life for patients.

Depending on how we view justice, we’ll have different views on who is eligible for assisted dying. Is it those whose quality of life is lowest? If so, it might not be terminal cases in need of treatment. Is it those who are most in need of treatment? This might include young children who many people are reluctant to provide assisted dying to. Until we’re clear on this principle, it’ll be hard to decide who is eligible and who is not.

The second principle worth thinking about is to treat like cases alike. This idea comes from the legal philosopher HLA Hart. He thought it was essential for ethical and legal distinctions to be made on the basis of good reasons, not arbitrary measures. A good example is if two people committed the same crime, they should receive the same penalty. The only reason for not treating them the same is if there is relevant difference in the two cases.

This is important to think about in terms of strict eligibility criteria. Let’s say we reserve assisted dying for people over 25 years old, which the NSW draft Bill does. Hart would encourage us to wonder, as Longstaff noted in The Ethics Centre’s submission, “what ethically significant difference lies between a 24-year-old with six months to live and who wishes to receive assisted dying and a 25-year-old in the same condition?”

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

What do we want from consent education?

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

An angry electorate

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Science + Technology

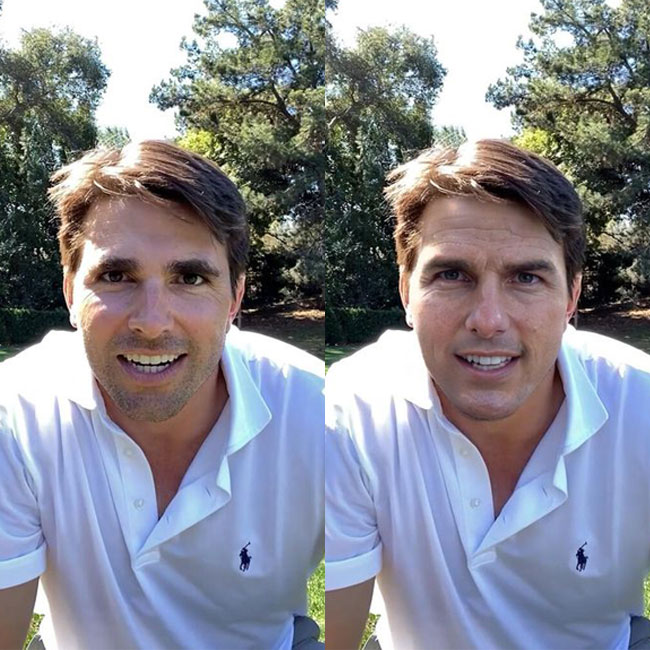

To see no longer means to believe: The harms and benefits of deepfake

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Putting the ‘identity’ into identity politics

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Ethics Explainer: Conservatism

Contrary to what many assume, the conservative political tradition is neither reactionary nor opposed to change. True conservatives are simply wary of revolutionary change – especially when inspired by utopian idealism.

Conservatives prefer an evolutionary approach, where experience, common sense, and pragmatism lend a certain stability to society and its institutions.

We could sum up the conservative political outlook in a couple of maxims:

-

“If it ain’t broke, don’t fix it”

-

“Don’t throw the baby out with the bathwater”

It is important to distinguish between conservatism as an ideological outlook and the conservative brand some political parties operate under. Some practice the type of cautious conservatism described above, whereas others are more radical in their outlook.

Conservatism is often associated with liberalism, unregulated capitalism, and in some cases, libertarianism. This is no accident. It’s the product of a mixed history of ideas and the occasional opportunism of certain individuals and political parties who have misappropriated the term for their own political ends.

Vive la révolution!

The most famous and early exponent of conservatism is the Irish-British philosopher, Edmund Burke. In most respects, the long-standing member of the British House of Commons was a classic liberal, respecting the ideals of liberty and equality.

But Burke found the French Revolution a step too far. A quick history lesson: the French Revolution was a 10-year uprising that began in 1789 against the aristocratic social and political systems. It eventually overthrew the monarchy.

In the revolution’s push for radical change, Burke saw the seeds of what we might now call totalitarianism – a society where the individual counts for nothing and the State for all. Burke captures this in his Second Letter on Regicide Peace where, describing the Revolutionary Government of France, he wrote:

“Individuality is left out of their scheme of government. The State is all in all. Everything is referred to the production of force; afterwards, everything is trusted to the use of it. It is military in its principle, in its maxims, in its spirit, and in all its movements. The State has dominion and conquest for its sole objects—dominion over minds by proselytism, over bodies by arms.”

This aversion to radical idealism and its tendency to lay the foundation for a totalitarian state is a theme frequently returned to by conservative philosophers. For example, Karl Popper observes in The Open Society and Its Enemies (Volume One):

“The Utopian attempt to realize an ideal state, using a blueprint of society as a whole, is one which demands a strong centralized rule of a few, and which is therefore likely to lead to a dictatorship.”

Like the pigs in George Orwell’s Animal Farm, after all the unrest and upheaval of the French Revolution, overthrowing the monarchy led to Napoleon’s rule, which is widely regarded as a totalitarian dictatorship. The conservative critique of efforts toward revolutionary change provide such examples as an argument for cautious and prudent evolution instead.

Conservatives are likely to feel that proponents of radical change often fail to realise that they will also be swept aside if something entirely new is to be made. As the contemporary philosopher in the ‘Burkean’ mould, Roger Scruton puts it:

“All that conservatism ultimately means, in my view, is the disposition to hold on to what you know and love. And if you don’t hold on to what you know and love, you will lose it anyway.”

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture, Relationships

There is more than one kind of safe space

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

TEC announced as 2018 finalist in Optus My Business Awards

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

James Hird In Conversation Q&A

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Lying

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Big Thinker: Martha Nussbaum

Martha Nussbaum (1947—present) is one of the world’s most influential living moral philosophers.

She has published on a wide range of topics, from tragedy and vulnerability, to religious tolerance, feminism and the role of the emotions in political life. Nussbaum’s work combines rigorous philosophy with insights from literature, history and law.

Our happiness is largely beyond our control

Nussbaum takes issue with people like the Stoics and Immanuel Kant, who suggest there is no place for emotion within ethics. They believe ethics is about the things we can control. It’s about the things that can’t be lost or taken away from us, like our thoughts and our virtues.

For instance, in his Groundwork to the Metaphysics of Morals, Kant claimed even if bad luck or circumstance meant you were unsuccessful in everything you tried to do, so long as you acted with a “good will”, your actions would still “shine like a jewel”.

By contrast, Nussbaum believes the fact our intentions, desires and hopes can be thwarted by circumstances tells us something really important about flourishing (that’s philosophy speak for living the good life). Specifically, that it’s vulnerable and fragile.

She may have had Kant’s writing in mind when she wrote the ethical life “is based on a trust in the uncertain and on a willingness to be exposed; it’s based on being more like a plant than like a jewel, something rather fragile, but whose very particular beauty is inseparable from its fragility”.

Risk is a scary notion in our society. We don’t like thinking about it and we’re not good at judging it accurately. Part of that is because we don’t like uncertainty. But Nussbaum encourages us to reframe our attitude to vulnerability, seeing it as a unique aspect of what it means to be human.

“To be a good human being is to have a kind of openness to the world, an ability to trust uncertain things beyond your own control.”

Politics doesn’t work without emotion

Most political philosophers and commentators are wary of the place of emotion in politics. When we think about the role of emotions in politics, it’s easy to focus on fear, disgust, envy and the ways they can corrupt our political life. It’s natural to assume politics would be better without the emotion, right?

Not according to Nussbaum. She suggests scrubbing politics clean of emotion would be like throwing the baby out with the bathwater. Yes, we need to be wary of the role of emotions in politics, but we couldn’t survive without them.

For one thing, it’s emotions like love and compassion that translate abstract concepts like truth and justice into real and lasting connections with particular groups and people. Ideas like human dignity capture what we all have in common but strong democracies tend to respect what makes different groups and people unique.

Emotions help us to cultivate a healthy balance between our attachments to ideas and institutions and our connection to particular places, people and histories. For Western democracies struggling to deal with different cultural groups and ideologies, Nussbaum’s view may help strike a balance between society-wide ideals and particular cultural differences.

What’s more, Nussbaum notes, political systems have always cultivated the emotions that serve them best. For example, monarchies cultivate childlike emotions of dependence and dictatorships often trade on a combination of nationalism and fear. These emotions create unity around a common political identity – albeit in ways people find problematic.

There’s promising terrain here, Nussbaum says, because if we can work out the emotions that best serve democratic life, we can then cultivate these emotions and create better citizens.

She thinks we can do this through ritual, public investments in art and a living sense of cultural and national history (she offers the rewriting of America’s founding fathers in Hamilton as a good example of this).

Nussbaum advises we can foster the emotions for citizenship with whatever “helps us to see the uneven and often unlovely destiny of human beings in the world with humour, tenderness, and delight, rather than with absolutist rage for an impossible sort of perfection”.

Educate for citizenship, not profitability

In Not for Profit: Why Democracy Needs the Humanities, Nussbaum targets the education system. She gives an ominous diagnosis:

Thirsty for national profit, nations, and their systems of education, are heedlessly discarding skills that are needed to keep democracies alive. If this trend continues, nations all over the world will soon be producing generations of useful machines, rather than complete citizens who can think for themselves, criticize tradition, and understand the significance of another person’s sufferings and achievements. The future of the world’s democracies hangs in the balance.

Nussbaum believes there is a crucial role for the education system – from early school to tertiary – in building a different kind of citizen. Rather than economically productive and useful, we need people who are imaginative, emotionally intelligent and compassionate.

She is also critical of the ‘No Child Left Behind’ approach to education in the United States, which put increasing pressure on schools to improve outcomes. They wanted to know test scores were improving, believing better education outcomes would help break the cycle of poverty. However, in focussing on outcomes, Nussbaum believes they prioritised memorising over the kind of education she thinks democracies need – philosophy.

You might be sceptical whether people stuck in a cycle of poverty need an education offering philosophical skills. The pressing need to be economically useful and employable can be seen as more urgent and important with good reason. It’s likely there’s a compromise to be struck here, but Nussbaum’s work is still important.

It provides us with an alternative model of education and helps us see the beliefs underpinning our current attitudes to education.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Authenticity

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

TEC announced as 2018 finalist in Optus My Business Awards

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Who are you? Why identity matters to ethics

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Philosophy must (and can) thrive outside universities

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

The ethics of smacking children

The ethics of smacking children

Opinion + AnalysisHealth + WellbeingRelationships

BY Matthew Beard The Ethics Centre 20 JUL 2017

Every generation likes to reflect on the way they were disciplined. They’re like old war stories, told with the fondness that comes with time and age.

I do the same. I was smacked as a child. For a time, I was convinced my backside was made of something other than flesh, such was its power to shatter wooden spoons. Weirdly, it’s something of a point of pride these days.

When it comes to smacking, it’s not just nostalgic to reminisce like this. It shapes our thoughts about whether smacking is ethical or not. “I was smacked and I turned out fine, so it must be OK.”

But that’s bad logic. The argument is a logical fallacy called “survivorship bias”.

Survivorship bias happens when we focus on those who made it through a difficult process without considering those who didn’t. The logic of “I was smacked and turned out OK” is the same as “I was tortured and I turned out OK”, but the fact you survived it doesn’t make it ethical.

When thinking about smacking, we need some better arguments. Here are a few things to consider.

Smacking is a show of force

With the exception of the grumpy nun from The Blues Brothers known as The Penguin, smacking only works on children who are too small to defend themselves.

Acknowledging this power imbalance changes how some people feel about the act of smacking. Philosopher and parent Damon Young writes, “deliberately striking [kids], whether coolly or in a rage, takes advantage of their weakness”.

Young thinks this is a question of character, writing “I don’t want to be the kind of man who hurts a smaller, weaker person”. Do you want to be the kind of parent who relies on physical power to command discipline, respect or obedience from your child?

Political philosopher Niccolo Macchiavelli said it was “much safer to be feared than loved when one must be dispensed with”. He thought fear was the most effective way to prevent people from betraying you because it creates “a dread of punishment which never fails”.

But Machiavelli had despotic political leaders in mind, not parents.

Effectiveness and ethics aren’t the same

Let’s go back to Macchiavelli for a second. He wasn’t interested in how to rule ethically, he wanted to know how to rule effectively. Sometimes it’s tempting to approach parenting the same way.

‘What’s the best way to get my child to sleep?’ ‘How can I stop him from biting me?’ When we’re bleary-eyed and desperately Googling for answers at three in the morning, we’re looking for whatever will get us the result we want. The means are less important to us than the ends.

Desperation doesn’t make for good ethical judgement. Telling your bub bedtime stories about the monsters who eat naughty children until they’re sobbing in fear might be an effective way to get them to toe the line but it’s not going to win you any parenting awards.

Parenting expert Barbara Coloroso suggests a slight modification to the ‘if it works, do it’ mentality. She suggests, “if it works and leaves a child’s and my own dignity intact, do it”. This is a crucial distinction – the dignity of both children and parents serves as a line in the sand against brute efficiency.

This doesn’t necessarily rule smacking out. Pope Francis himself thought smacking could be a dignified way of teaching kids about ethics.

Talking about a dad who sometimes smacks his kids – but never in the face – the Pope said, “How beautiful. He knows the sense of dignity. He has to punish them but does it justly and moves on.”

As a counter example, it’s worth wondering how dignified the Pope would feel being bent over someone’s knee.

What are you really communicating?

Some people defend smacking as a way of communicating with a child when words won’t do the job. They suggest that in the midst of a meltdown, it’s hard to reason with a child, but if a quick ‘love tap’ gets them to listen to you, it might allow for a constructive conversation.

These folks might enjoy reading Hannah Arendt. The 20th century philosopher thought violence was an effective form of communication to help moderate, reasonable voices to be heard. However, Arendt’s support for violence comes with a warning: the use of violence risks its being legitimised as a form of communication in a community (or family). Once violence becomes the talk of the town, everyone can be tempted to start speaking it.

Arendt concluded, “the practice of violence, like all action, changes the world, but the most probable change is a more violent world”.

If the same is true of families, it might be worth thinking twice before talking with the hand.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Peter Singer on charitable giving

Big thinker

Relationships

Seven Female Philosophers You Should Know About

Big thinker

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Big Thinker: Noam Chomsky

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships