Nothing But A Brain: The Philosophy Of The Matrix: Resurrections

Nothing But A Brain: The Philosophy Of The Matrix: Resurrections

Opinion + AnalysisRelationshipsSociety + Culture

BY Joseph Earp 26 DEC 2021

It is one of the most iconic scenes in modern cinema, Neo (Keanu Reeves) sits before the sage-like Morpheus (Laurence Fishburne) in a room slathered with shadows, and is offered a choice.

Warning: this article contains spoilers for The Matrix Resurrections

Either he can take the blue pill, and continue his life of drudgery – a digital front, as it turns out, to stop human beings from realising they are nothing but batteries to power a race of vicious machines – or take the red pill, and awaken from what has only been a dream.

The image of this fateful choice has been co-opted by conspiracy theorists, endlessly picked over by film scholars, and referenced in a thousand parodies. But perhaps the most interesting critique of the scene comes from Slovenian philosopher Slavoj Zizek. Why, Zizek asks, is there this binary between the imagined or “fake” life, and the real one? What is the distinction between fantasy and reality; how can one state ever exist without the other? There is no clean separation between the lives we live in our heads, and the so-called external world, no line that we can draw between the artificial and the authentic.

Maybe Lana Wachowski, the director of the newest iteration in the franchise, The Matrix: Resurrections, heard Zizek’s words. Early on in the film, Resurrections re-stages a version of Neo’s fateful choice from the first instalment. But this time the falseness of the choice has been revealed: he is offered only the red pill. The binary between fake and real has been destroyed. Whatever path he takes – whether he comes frightfully into consciousness in his vat of goo, his body tended to by the tendrils of machine, or continues to pad through a life of capitalist turmoil – he is only ever in his own head.

The Cage of Our Own Heads

Solipsism, the belief that only the mind exists – and not any old mind, your mind – has its roots in Cartesian skepticism. It was René Descartes who found himself plagued by a nagging worry: what if everything that he could see, smell, and hear was merely the conjurings of a demon, tricking him into sensations that he could not prove are real? Or, in the language of the Matrix: what if our entire world is a construct, as cage-like and bleak as the containers that cattle are exported to the abattoir in?

Descartes, doubting the existence of reality itself, came to believe that there were only two things one could be sure of. The first, as he famously pronounced, is the existence of at least one mind: “I think therefore I am.” After all, if there wasn’t a mind to wonder about the nature of reality, then there wouldn’t be any wondering about the nature of reality. The other, less frequently discussed foundation of truth that Descartes believed in was the existence of God: if at least one mind exists, then God must have created it, Descartes thought.

Resurrections accepts only the first premise. There is no hope that God might exist out there, in the ether, an entity to pin some sense of certainty upon.

It is a film about being entirely trapped in a subjective experience that you cannot fully verify; held captive in the shaky cage of your own mind.

When we meet Neo, he is seeing a therapist, in recovery from a suicide attempt. The source of his suffering? That he is plagued constantly by memories that don’t seem to belong to him; that he is filled, always, with a nostalgia for a past he is not sure he has even lived; that he is concerned the fictional stories that he tells as a game designer might in fact as authentic as the desk he sits at, the boss that he serves. Or vice versa: perhaps the desk, the boss, are the entities to be trusted, and the sprawling lines of code that make up the video game are just a joyful illusion.

Neo has no way of verifying the reality of any of these thoughts. They are all just mental constructs, representations that are slowly fed to him for reasons that he cannot fathom, each carried with the same epistemic force. Desperate, he tries to use his therapist, played by Neil Patrick Harris, as his watermark; in what might be fits of paranoid delusion, he calls the man, raggedly trying to work out if he is losing his mind, hoping to dredge apart dreams and the complex mental representation we call “life”.

But as Resurrections later reveals, the therapist is the least trustworthy source that Neo could have turned to. The therapist is not just part of a fantasy that might be a reality, and vice versa: he is its very creator. And his whims, when they are explained at all, are vague and confusing. He is no adjudicator of what is fictive and what is corporeal. He is just one more layer of fantasy-as-reality, and reality-as-fantasy, a mess of whims, and desires, and dreams that exists in two states at once.

Loneliness and Hope

This is, on some level, a comment on our essential loneliness. We might feel as though we are surrounded by people, that there are lives being lived alongside ours. But, Resurrections says, we have no way of understanding the minds of our friends, families, and strangers – they are mysteries to us. Neo’s journey in Resurrections is one of finding a community, the rag-tag group of machines and humans that are hoping for a better world. And yet this community acts in ways he cannot predict; that surprise him. And more than that, he has no way of knowing if they are even real – throughout, he constantly questions whether he has actually awoken, or if he is merely living in complex whorls of fantasy.

But there is hope here too. Resurrections is, amongst other things, a paean to the power of storytelling. Those characters who attempt to dismiss our ability to spin fictions – chiefly the therapist, and the capitalistic Agent Smith, who wants to turn narratives into more products to be sold – are the film’s villains. Its heroes are those who fully embrace the power of the stories that we spin for ourselves, whether they be video games or complex narratives about our own pasts. After all, though it might be bleak to imagine that the external world is always filtered through a shaky subjective experience, that means that our fantasies are as powerful – as life-altering – as anything “real.” The world is forever what we make it.

The Power of Fear and Desire

If we are in total charge of our own destinies, able to spin ourselves into whichever corners that we choose, then what motivates us? After all, if everything is able to be re-written, then what reason do we have for doing any one thing over another?

Total freedom comes with a price, after all; there is a kind of terrible laziness that can descend upon us when we know that we can do whatever we want, a kind of malaise of submission, where, instead of rewriting the world, we sit back, and let it unfurl however it wants.

It is this state that Neo’s fellow video game designers have fallen into, a kind of overwhelming boredom that narrows their scope of possibilities and makes them one more cog in a machine that is completely out of their own control.

But Resurrections has a rebuttal to this laziness. In a key moment in the film, Neo’s therapist explains that the world he has created – the world of the Matrix – is driven, quite simply, by two states. The first is fear; the fear that we will lose what we have, whether that be our minds, in the case of Neo, or our freedoms, in the case of his fellow guerillas. And the second is desire; the world-making force that drives us to move fast, to want more, to continually strive for a different kind of world.

There is a bleak reading to this thesis statement, one that aligns with the philosophy of Baruch Spinoza. Spinoza believed that we are at our least free when motivated by causes outside of control; when our own striving for perfection, what he called our conatus, becomes putrefied and affected by those around us. After all, if we are petrified by fear, and if our hope for a different world is contingent upon the behaviour of others, then we will perpetually be buffeted around by fictions, by memories, by states that are causally connected to forces outside our control. We will be, simply put, trapped, stuck in the ugly cycles of code that Neo spends the first 20 minutes of Resurrections designing.

But there is still, even here, hope. After all, that fear need not be necessary painful; that desire need not be necessarily linked to unstable foundations. If we combine the notion that we are only within our own minds, that our fantasies have as much explanatory power as our “realities”, and this cycle of fear and desire, we can begin to understand how we might rewrite everything. We can make of fear and desire as we wish; we can alter and shape the people who we love, and we dream of.

That is the message encoded in the final shot of the film. Neo and Trinity (Carrie-Anne Moss) have given up on the search of epistemic foundations. They do not kill the therapist who has kept them in the bondage of The Matrix. Instead, they thank him. After all, through his work, they have discovered the great power of re-description, the freedom that comes when we stop our search for truth, whatever that nebulous concept might mean, and strive forever for new ways of understanding ourselves. And then, arm in arm, they take off, flying through a world that is theirs to make of.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Society + Culture

On policing protest

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Online grief and the digital dead

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Should we abolish the institution of marriage?

WATCH

Relationships

Virtue ethics

BY Joseph Earp

Joseph Earp is a poet, journalist and philosophy student. He is currently undertaking his PhD at the University of Sydney, studying the work of David Hume.

A parade of vices: Which Succession horror story are you?

A parade of vices: Which Succession horror story are you?

Opinion + AnalysisRelationshipsSociety + Culture

BY Joseph Earp 20 DEC 2021

There is a singular thrill that comes from watching very bad people do very bad things.

The anti-hero has been a staple of modern television and cinema for decades, made popular by Tony Soprano splashing about in a swimming pool with a brace of ducks, taking some much needed “me time” after overseeing a truly astonishing number of murders.

This kind of art might have some therapeutic aspects – it teaches us how not to be, so we might learn how to be – but that’s not its purpose. Its purpose is entertainment, the sick, giddy feeling that comes over us when we watch people throw off the entirely artificial rules of morality, and behave however they want.

Moreover, this kind of art is a way of teaching us the manners by which our moral outlooks are shaped by repetition: habit and practice. When we see someone like Soprano do the same evil things, over and over again, we learn about the compounding nature of vice, the way that one bad action spawns a myriad of others.

No show exemplifies that thrill better than Succession. Its characters are vicious, and in both meanings of the term: each week, they tear each other apart, sacrificing even familial bonds for the sake of victories that almost immediately sour in their mouths. They live in a world that is constantly in the process of ratifying, and, briefly, rewarding them; they are shaped by their wealth, and by the uneasy collective they form with each other, in which power is everything and weakness is to be avoided at all costs.

But this gaggle of do-badders are not alike in their foibles. Each principal member of the cast displays a different vice, and has a different way of working towards the same unpleasant ends. Here is a kind of “pick your horror” list of the show’s central players, outlining each of their worst qualities. Which deviant are you?

Logan Roy: The Happy Capitalist

As Peter Singer noted, capitalism thrives on individuation; the idea that we are made up of communities of one, and that it is always better to sacrifice the well-being of others in order to get ahead. And how better to sum up that belief that you should, at all times, consider yourself the number one priority than the behaviour of Logan Roy? Logan has no loyalty – he will hurt whoever he needs to hurt. He is one of the few purely, uncomplicatedly immoral characters of the show, being openly unremorseful. He is, as Aristotle would put it, in total vicious alignment – he feels no urge to do the right thing, and his behaviours line up perfectly with his moral universe, of which he is the centre.

Kendall Roy: The Coward

Speaking of alignment, the character in Succession whose behaviours are most out-of-sync with their desires is Kendall Roy. Unlike Logan, he is not without remorse. Time and time again, he repents – one of the most affecting moments of the recent season was the man on his hands and knees, saying, in a voice of exhaustion, that he has tried. He suffers from a tension that we all feel, one between moral behaviour and immoral behaviour. He wants to be courageous – that is how he sees himself. But his base level desires, many of which he hasn’t even analysed within himself, are in constant conflict with the globalised outlook he has on his moral character. There is a gulf between how he considers himself in the abstract, and how he actually acts, moment by moment.

The problem, in essence, is that Kendall moves too fast. His decisions come too quick, and they are guided by his misplaced desires to appease his father and to feed into the pre-existing drama of the family. Iris Murdoch once wrote that we should train ourselves to live a moral life, habituating good action so we can unthinkingly help others when the time comes. When the time comes for Kendall, as it does with insistent regularity, he unthinkingly makes the wrong choice, sacrificing his own systems of values to appease a man who considers him less than dirt. That’s cowardice in its purest form.

Roman Roy: The Casually Cruel

When we think of evil, we tend to imagine oversized portraits of crooked megalomaniacs, stealing candy from babies and kicking the backsides of puppies. But as philosopher Hannah Arendt tells us, evil need not be enacted by larger-than-life villains. Indeed, Arendt believed that vicious behaviour can be performed in a myriad of tiny ways by the most unassuming of individuals. That is Roman Roy to a tee.

Through the series, Roman appears to be nothing more than a happy-go-lucky hedonist, a man filled to the brim with pleasures, who enjoys the finer things in life. But that happiness also extends to the vicious behaviour of himself and of others. He loves suffering and rejoices in the chaos of his family life. His horrors are pulled off with a smiling face, as though they are nothing but briefly disarming attractions, as inconsequential as a county fair.

Shiv Roy: The Manipulator

It was Immanuel Kant who once wrote that we should always treat those around us as ends in themselves, never as means. Kant thought it one of the great immoralities capable of being enacted by human beings for us to see those around us tools, whose internal lives we need never to consider. After all, for Kant, human beings are the creators of value – there is no goodness intrinsic in the world, and it exists only in the eye of the beholder. Try telling that to Shiv Roy. Shiv sees those around her as mere means of getting what she wants, to be used and discarded on a whim – even her husband is one more bridge to be shockingly burnt after she has crossed it.

Not that Shiv is without redemption. Kant also believed that there is always good will: an iron-wrought and rational understanding of the correct thing to do in any moral situation. His was a virtue ethics founded on principles, and Shiv does, despite herself, have those. Take, for instance, her complicated introduction to the world of politics in season three. She is offered what Peter Singer would call the ultimate choice – the option of winning the race against her siblings for her father’s affections, if she endorses a particularly slimy Republican candidate for President. There are, to our surprise – and maybe even to hers – lines that Shiv will not cross. Turns out even the most manipulative of us can find there are things that we simply will not do.

Cousin Greg: The False Innocent

Innocence can have an intrinsic value: it can be good for itself, in itself. But Cousin Greg, Succession’s scheming dope, uses his innocence instrumentally. He presents himself as being the dumbest person in the room, forever in the process of duping others with his blandness. But there is nothing innocent to the way he acts.

His is a vice that comes from its very duplicitousness – he presents himself one way, as though he never quite understands the situation, and then acts very differently in another. It’s proof, if any more was needed, that virtues can be a disguise that we can drape ourselves in the illusion of good behaviour, for nothing but our own benefit.

Tom Wambsgans: The Sycophant

Loyalty is a morally neutral character trait. It can be virtuous, as when we are loyal to our friends, and it can be vicious, as when we unbendingly act in accordance with an evil benefactor. Tom Wambsgans started Succession as one more foot soldier, a buffoon kicked around by forces much greater than him: no wonder he found a twisted kind of kinship with Cousin Greg, another duplicitous fool. But his loyalty to Logan – his unwavering belief that the sole purpose of his life was to be in the good books of the elder Roy – eventually transformed him into something much more nefarious.

Tom is unwavering in his belief system, utterly obsessed with power, and firmly of the opinion, contra to the writings of Michel Foucault, that it only moves in one direction. Tom wants total power, and he wants it totally. He does not consider, as Foucault did, that the person over whom we hold power also holds power over us. If all of history is a boot stomping on a human face, then that’s Logan’s spit-shined boot, and Tom’s smugly smiling face.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Science + Technology, Society + Culture

The terrible ethics of nuclear weapons

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Your child might die: the right to defy doctors orders

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Science + Technology

The ethics of exploration: We cannot discover what we cannot see

Explainer

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Gender

BY Joseph Earp

Joseph Earp is a poet, journalist and philosophy student. He is currently undertaking his PhD at the University of Sydney, studying the work of David Hume.

Of what does the machine dream? The Wire and collectivism

Of what does the machine dream? The Wire and collectivism

Opinion + AnalysisPolitics + Human RightsRelationshipsSociety + Culture

BY Joseph Earp 10 DEC 2021

This week, a group of more than a dozen Rohingya refugees launched a civil suit against Facebook, alleging that the social media giant was responsible for spreading hate speech.

The victims of an ongoing military crackdown in Myanmar, the refugees claimed not merely that Facebook allowed users to express their anti-Rohingya views, but that Facebook radicalised users – that, in essence, the platform changed beliefs, rather than merely providing a conduit to express them.

The suit is, in many ways, the first of a kind. It targets the manner in which systems – whether they be social media giants, video streaming sites like YouTube, or the myriad of bureaucracies that we all engage with in one way or another almost every day – warp and change beliefs.

But what if the suit underestimates the power of these systems? What if it’s not merely that social and financial enterprises alter beliefs, but that these enterprises have belief sets entirely of their own? More and more, as capitalism continues to ratify itself, we are finding ourselves swept up in communities that operate on the basis of desires that are distinct from the views of any one member of those communities. We are all part of a great, groaning machinery – and it doesn’t want what we want.

Pawns in a Game

There is a key sequence in David Simon’s critically adored television series The Wire that sums up this perspective perfectly. In it, three young men, all of them members of a rickety enterprise of crime, find themselves playing chess. The least experienced man does not understand the game – how, he wants to know, does he get to become the king? He doesn’t, the most experienced man explains. Everyone is who they are.

Still, the younger man wants to know, what about the pawns? Surely when they reach the other side of the board, and get swapped out for queens, they have made it – they have beat the system. No, the experienced man explains. “The pawns get capped quick,” he says, simply.

There is a deep, sad irony to the scene: the three men are all pawns. They have no way of beating the system. They will not even live to become queens. When one of them dies a few episodes later, shot to death by his friend, there is a grim finality to the murder. He did, as expected, get capped quick.

This is the focus of The Wire – the observation that members of any community are expendable when weighed against the desires of that community. The game of chess is bigger than any of the pawns could imagine, a system with its own rules that they are merely contingent parts of. And so it goes with the business of crime.

Not only crime, either. The genius of The Wire is the way that it draws parallels between those who operate outside the law, and those who uphold it. The cops who spend the series cracking down on the drug trade are also pawns, in their way: lowly members of a system that they are utterly unable to change. No matter what side of the law that you fall on, you will find yourself submerged in bureaucracy, The Wire says – in the machinations of a vast system of power relations with a goal to constantly perpetuate itself, at your expense.

These are the systems that Sigmund Freud wrote of in his seminal work, Civilization and Its Discontents. For Freud, there is an essential disconnect between the desires of individuals and the desires of the social communities that they unwillingly become a part of. There are things at foot that are bigger than any of us.

Bureaucracies are not the sum total of the desires and beliefs of the members of those bureaucracies. These systems have a life – a value set – entirely of their own.

The Game Never Changes

If that is the case, then how does change occur? The Wire offers only dispiriting answers. The show’s idealists – renegade cop Jimmy McNulty, rogue crime boss Omar Little – either find themselves subsumed by the system that lords over them or eliminated. There is a hopelessness to their rebellion. They uselessly throw themselves into the path of a giant piece of machinery, hoping that their mangled bodies slow the inevitable march of progress.

It doesn’t work. Those who thrive are those who give themselves over entirely to the system, who align their values perfectly with the values of their community and embrace their own insignificance. Snoop, the show’s most hideous and intimidating villain, is a happy pawn, one who has never once considered changing the rules of the game that will send her too into an early, dismal grave.

But what if we all stop playing? That is the solution that The Wire never considers. If these systems, whether they be criminal or judicial, are to be changed, then it requires a different kind of collectivism. We are all part of many communities, not just one. If we remember this – if we understand that we have the power and solidarity that comes from being a member of a particular class, a particular race, a particular gender – then we can fight collective power with collective power. The solution isn’t to get the pawn to the other side of the board. It’s to tip the board over.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Our desire for reality: What OnlyFans says about sexual fantasy

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

How to break up with a friend

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships, Society + Culture

The sticky ethics of protests in a pandemic

Reports

Politics + Human Rights

The Cloven Giant: Reclaiming Intrinsic Dignity

BY Joseph Earp

Joseph Earp is a poet, journalist and philosophy student. He is currently undertaking his PhD at the University of Sydney, studying the work of David Hume.

The self and the other: Squid Game's ultimate choice

The self and the other: Squid Game’s ultimate choice

Opinion + AnalysisRelationshipsSociety + Culture

BY Joseph Earp 25 NOV 2021

In the world of Netflix’s smash hit Squid Game, a collection of desperate people must make a terrible choice: they can either keep living their lives, which are filled with debt and suffering, or they can submit to the titular competition, a series of contests based on children’s games. If they win these contests, their debts will be absolved. If they lose, they will die.

*Spoiler warning for Squid Game

The Australian philosopher Peter Singer would call this an “ultimate choice.” Although on the surface, it is a decision as to whether or not to live with debt, in a much deeper sense, it’s a decision about how to live. The very foundational beliefs of Squid Game’s frantic characters are being challenged. What matters to these people? What do they want out of life? And, just as importantly, how far will they go to get it?

The State of Nature

Squid Game depicts a world of pure barbarism: guided by their desperation, its characters form alliances only when it is mutually beneficial to them, and are often as quick to betray one another. In episode three, for instance, Sang-woo uses insider knowledge of the next contest to get himself ahead, concealing from his supposed allies that he is already aware of what is about to occur.

True acts of kindness sometimes flash through like fish glimpsed at the bottom of a river – consider Hwang Jun-ho, whose participation in the world of Squid Game is guided by the love of his brother – but such moments of empathy are few and far between.

The depiction of such a blood-thirsty, self-interested world is one the philosopher Thomas Hobbes played upon in his construction of the “state of nature.” According to Hobbes, human beings who exist in this state live in a way that is “nasty, brutish, and short.” In such a primal state, one without government, there is no centralised means of understanding or enforcing what is right and wrong, and self-interest is the name of the game.

“So long a man is in the condition of mere nature, (which is a condition of war,)” Hobbes wrote, “private appetite is the measure of good and evil.”

Hobbes believed that the only way to avoid this state of nature was to submit to a governing force – to hand oneself over to a power that could create and enforce a set of rules, known as the social contract. The world of Squid Game contains such a governing force, the shadowy world of the VIPs, who run the games for their own amusement.

But rather than guiding the games’ participants out of the state of nature, the VIPs further deepen and enforce it. The rules that they develop are explicitly designed to keep the desperate players in a world of confusion and barbarism, where self-interest is rewarded, and chaos is the name of the game. The lives of the participants are nasty, brutish, and short, and their spurning of ethics in favour of desperate attempts to get ahead is actively rewarded by a system that runs, above all else, on violence.

The suspension of the moral code

This system, vicious as it is, pushes ordinary people to extraordinary lengths. The characters of Squid Game are, for the most part, simply and vividly drawn – they are defined above all else by their desire to absolve their debts and live freely. That one desire is all it takes for them to suspend the usual moral code that most of us live by, and to act in frequently horrific ways.

Even Sang-Woo, one of the more honorable characters in the show, ends up making deeply immoral choices, culminating in his decision to hurl the glassmaker off a platform in a final act of desperation. He has no stable set of ethics – his code is shaped by a system that thrives on horror and pushes human beings to consider their fellow brethren as little more than tools to be used and discarded at whim.

In this way, Squid Game offers a gleefully cruel riposte to the notion of virtue ethics. Its characters do not act in consistent, moral ways, as virtue ethics imagines that agents do. Although it takes a combination of financial ruin and a system deliberately designed to sow mistrust and horror for them to abandon their usual moral principles, it still brings up some uncomfortable questions about how easily we might abandon our ethics in the real world.

With a kind of horrifying elegance, the show also reveals just how fragile our notion of solidarity can be. We might want to believe that there are bonds between ourselves and even total strangers that cannot be broken – a kind of communal well-spring of trust that stops abject violence from breaking out. But dangle the mere proposition of a debt-free life in front of people willing to do anything to save themselves and their families, and this sense of community breaks horribly down. The show’s participants are alienated not only from their own moral code, but from each other. They are strangers in the deepest sense of the term, the simple, child-like games of the show’s title obliterating any sense of shared humanity.

But can these participants be blamed for their actions? Derek Parfit, the English philosopher, would argue not. It was he who developed the notion of “blameless immorality”, conditions under which people can be forced into vicious actions for which they are not culpable. The heroes of Squid Game are propping up a system that perpetuates further horror, certainly, but their autonomy has been radically diminished. They are little more than puppets, guided by powers outside of their control, their actions no longer their own.

Ethics Versus Self-Interest: The False Choice

Squid Game rests on the principle that self-interest and ethics are at loggerheads with one another – that choosing to do good for others leads necessarily to a sacrifice for oneself. Yet, it’s worth analysing this supposed dichotomy between self-interest and a good, ethical life.

Certainly, the notion that helping others requires us to sacrifice something for ourselves is an old, pervasive myth – it’s why we can view do-gooders as suckers, wasting time on the help of others instead of getting ahead. As Singer notes, such a view was particularly prevalent in the ‘80s with the rise of Wall Street, a world where duping the market – and even your supposed friends – had considerable benefits.

Act immorally – lie, cheat and steal – and you too could become a power player, with more wealth than you dreamed of.

But is there really such a distinction between being self-interested and acting ethically? Could it not be that this is merely an old capitalist myth, designed to perpetuate a system that thrives on “othering” and isolation? After all, viewing our interests as separate from those around us requires us to believe that we are sealed off from the social world, that there is some kind of line to be drawn between behaviours that are meaningfully “ours” and those that belong to others.

In actual fact, it is worth moving away from such an individualist notion of the self, and towards a more communal one. As it happens, the characters of Squid Game are actively hurt by the ways that they are forced to view themselves as alienated from their fellow competitors. It benefits only the show’s mysterious villains, explicitly capitalist and murderous sociopaths, for the heroes of Squid Game to believe in the line between what will help them, and what will help their friends. When, in the penultimate episode, Gi-hun suggests to Sae-byeok that they team up against Sang-Woo, Gi-hun makes the fatal mistake of believing that she has anything to gain through Sang-Woo’s misfortunes.

Such a move away from individuation is not easy. Indeed, Squid Game has a breathtaking nihilism to it –there is no easy way for the characters to escape this deep alienation from one another. The system does not permit it. In the words of Audre Lorde:

“…the master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house.”

As philosopher Mark Fisher once wrote in his explication of capitalist realism (the notion that capitalism has pervaded every aspect of human life and is now essentially inescapable), even the ways in which Squid Game’s doomed characters attempt to overthrow their bonds are subsumed as part of those very bonds themselves.

Just as anti-capitalism becomes tainted by capitalism, the means of overthrowing the system sold as one more product, the characters of Squid Game have no recourse by which to escape the individuation that they are fatally trapped in. Their very attempts to connect with one another are undermined by the rules of each game, like the marble game, where voluntarily made pairs are then forced to kill each other.

Squid Game is thus a word of warning. In its terror and violence, it is a reminder to always strive for community, away from individuation and towards a system in which we see fellow agents as more alike us than not. Hope might not be possible for the show’s protagonists, whose very rebellion is neutered at every turn. But, if we resist the moral alienation and deep individuation thrust upon us by capitalism, it might be possible for us.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Climate + Environment, Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

This is what comes after climate grief

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Are there limits to forgiveness?

Big thinker

Relationships

Big Thinker: David Hume

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

“I’m sorry *if* I offended you”: How to apologise better in an emotionally avoidant world

BY Joseph Earp

Joseph Earp is a poet, journalist and philosophy student. He is currently undertaking his PhD at the University of Sydney, studying the work of David Hume.

Meet Josh, our new Fellow asking the practical philosophical questions

Meet Josh, our new Fellow asking the practical philosophical questions

Opinion + AnalysisRelationshipsSociety + Culture

BY The Ethics Centre 21 OCT 2021

At The Ethics Centre, we firmly believe ethics is a joint effort. It’s a conversation about how we should act, live, treat others and be treated in return.

That means we need a range of people participating in the conversation. That’s why we’re excited to share that we have recently appointed Joshua Pearl as a Fellow. CFA-accredited, and with a Master of Science in Economics and Philosophy from the London School of Economics, Josh is currently a director at Pembroke Advisory. He also has extensive experience as a banking analyst, commercial advisor and political advisor – diverse perspectives that inform his writing.

To welcome him on board and introduce him to you, our community, we sat down for a brief get-to-know-you chat.

You have a background in finance, economics and government, and also completed a Master of Science in Economics and Philosophy – what attracted you to the field of philosophy?

I had always read a lot of political philosophy but when I first worked as a political advisor, it really dawned on me how little I actually knew. I figured what better way to learn more than by studying philosophy at the London School of Economics and Political Science.

Tell us a little bit about your background in finance, and how that shapes your approach to philosophy.

My undergraduate degree was in economics and finance and my first job out of university was with an investment bank. Later on, I worked for an infrastructure development and investment firm. I’ve really enjoyed my professional experience, especially later in my career, though there were times early on when I questioned whether I was sufficiently contributing to society. And in truth, I probably wasn’t.

One way working in finance has helped the way I think about philosophy is that finance is practical. It’s a vocation. So when I think about philosophy I try to answer the “so what” questions. Why should we care about a certain issue? What are the practical implications?

In the context of finance, there are so many practical philosophical questions worth asking. What harm am I responsible for as an investor in a company that manufactures or owns poker machines? Should shareholders be advocating for corporate and regulatory change to help combat climate change? What are the implications of a misalignment between my investments and my personal values? And in the context of economics, philosophical questions are everywhere. What does a fair taxation system look like? How are markets equitable? Is it a problem that central bank policies increase social inequality?

These are super interesting issues (or at least I think so!) that have practical implications.

You mentioned you worked in government as a political advisor – what did you take out of that experience?

It was an amazing experience in so many ways. It was fantastic to work with really interesting people from a variety of backgrounds and have the opportunity to meet so many different members of the community, whom I wouldn’t normally have the opportunity to meet. I also felt very lucky to work for a woman whom I have a lot of respect for. Someone from a non-traditional background who has not only been very successful in her political career but has also contributed to society in a really positive way.

One of my biggest learnings from the experience was how important it is to try and consider issues from a range of multiple perspectives, with the hope of getting closer to some objective view. As part of this process, you realise the legitimate plurality of views that exist and the intellectual and moral uncertainty associated with your own views.

Do you have a favourite philosopher or thinker?

Thomas Nagel is a rockstar. He is in his eighties now and is still teaching at New York University. He is a really clear thinker whose writing is accessible and entertaining, and he isn’t afraid to challenge the orthodox views of society, including in areas such as science, religion and economics.

Nagel is a prolific writer who has undertaken philosophical inquiries across a range of fields such as taxation (the Myth of Ownership), evolution (Mind and Cosmos), and epistemology and ethics (The View from Nowhere). His most famous piece is probably What is it like to be a bat?, a journal article that is a must read for anyone interested in human consciousness.

If I could add a reasonably close second it would be Toby Ord. Ord is a young Australian whose work has already had huge real-world impacts in effective altruism (how can philanthropy be most effective) and the way society thinks about existential human risks. His recent book, The Precipice, was published in 2019 and analysed risks such as comet collisions with Earth, unaligned artificial intelligence and pandemics…

Covid restrictions have of course played havoc on the economy and our personal lives in the past 18 months – how have you been coping personally with lockdowns?

I arrived back in Australia on the very day mandatory hotel quarantine was introduced, so in some sense, everything since then has been a breeze! But to be honest, lockdown hasn’t affected me that much and I’m lucky to live with a really amazing partner. Over the course of lockdown, I’ve read a little more, written a little more, played tennis a little more… and spent way too much time trying to do cryptic crosswords.

Do you see any fundamental changes to our economic systems coming about as a result of the pandemic?

I don’t know that there will be fundamental changes, but I do hope there will be positive incremental changes. One is central bank policy. It seems inevitable that at some stage there will be a review of the RBA and with luck we follow the Kiwis’ lead and ask the RBA to consider how their policies inflate financial asset and house prices – the results of which add substantial risk to the financial system and increase social inequality. The second is what happens if (or perhaps when) Australia considers how to reduce the COVID fiscal debt. I am hopeful that we will consider land and inheritance taxes for reasons of fairness, rather than simply taxing people more for doing productive things like going to work.

As a consultant and Fellow of The Ethics Centre, what does a normal day look like for you?

My days are pretty structured, but the work is really variable.

My consulting focus is on issues at the intersection of finance, economics and government, such as sustainable and ethical business and investment. That might be working on an infrastructure project with an investment bank or government; undertaking a taxation system review for a not-for-profit; or working on ethical and sustainable investing frameworks and opportunities with various institutions, including with The Ethics Centre, which has been fantastic.

As a Fellow of The Ethics Centre, my primary involvement is through writing articles on public policy issues, with the aim of teasing out the relevant philosophical components. Questioning purpose, meaning and morality is part of being human. And it is also something we all do, all of the time. Yet there are very few forums to engage on these topics in a constructive and meaningful way. The Ethics Centre provides a forum to have these conversations and debates, and does so outside of any particular political, corporate or media lens. I think this is a huge contribution that really strengthens the Australian social fabric, so I feel really lucky to be involved with The Ethics Centre community.

Lastly, the big one – what does ethics mean to you?

That certainly is the big one! I tend to think about ethics on both a personal and social basis.

On a personal basis, to me, ethics is about determining how best to live your life, informed by such things as your family’s values, social norms, logic and religion. Determining your “ideal life” so to speak. It is then about the decisions made in trying to achieve that ideal, failing to achieve that ideal, and then trying again.

On a social basis, to me, a large part of ethics is the fairness of our social institutions. Our political institutions, legal frameworks, economic systems and corporate structures, as examples. Pretty cool areas, I think.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

The Bear and what it means to keep going when you lose it all

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Ask an ethicist: How much should politics influence my dating decisions?

Big thinker

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Big Thinker: Michel Foucault

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

The truths COVID revealed about consumerism

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Meet Daniel, helping us take ethics to the next generation

Meet Daniel, helping us take ethics to the next generation

Opinion + AnalysisRelationshipsSociety + Culture

BY The Ethics Centre 23 AUG 2021

At The Ethics Centre, we believe ethics is a collaboration – a conversation between diverse people trying to figure out how to act, live and make good decisions.

This means we need a range of people participating in the conversation, of all ages. Thanks to our donor, Chris Cuffe AO at Third Link Investment Managers, we are excited to share that we have recently appointed Daniel Finlay to Youth Engagement. Daniel is a graduate from the University of Sydney with a Bachelor of Arts and Science (Hons) and a Postgraduate Certificate in Publishing. He also received Class I Honours for his thesis in ethical philosophy. To welcome him on board and introduce him to you, our community, we sat down for a brief get-to-know-you chat.

Tell us, what attracted you to philosophy?

My first philosophy-related class was called Bioethics and I actually took it because I had come back from a break and couldn’t continue my psychology units until the next semester. But from the moment I left the first tutorial, I knew this was where I would end up going. The unit was practical ethics with a focus on humans and their bodies. The topics we covered ranged from black-market organ selling to sex work to people suffering from body integrity identity disorder (BIID). The BIID discussion particularly made me realise how many questions we have to face that simply don’t have neat or obvious answers. BIID is a very rare disorder where a healthy person very strongly desires to amputate one or more of their limbs. And here we were, a group of fresh-faced 19-year-olds, trying to figure out what the hell to do with that information.

That sounds like an interesting place to start. Let’s jump over to COVID and restrictions. How are you dealing with it and what do you hope we’ll be able to bring out the other side?

Honestly, I’m part of the lucky few who haven’t been too flipped around by the lockdowns. I do very much miss rock climbing and have admittedly fallen back into lazy habits without it, but on the whole I can deal with being at home very easily because that’s where I like to spend most of my time regardless.

I’m hoping that we all come out of this with a bit more patience. COVID has obviously slowed a lot of things down for a lot of people. Media content is coming out slower, packages are constantly delayed, work projects put on the back-burner. Hopefully most people come out the other side of this with the realisation that most things aren’t as urgent as they sometimes seem, and a little patience when dealing with fellow humans can go a long way.

With all that time at home, you must have developed some guilty pleasures during the pandemic. Can you share one with us?

I wish I had something quirky or funny to share but the sad reality is my guiltiest pleasure is just watching TikToks at midnight in bed instead of getting a reasonable night’s sleep.

Pretty sure that you aren’t alone there. So, what does a standard day in your life look like?

Mostly playing games, watching Netflix/YouTube and managing an online Discord community I run. At the moment, I’m researching how, when and why young people engage with ethics in their lives and offering a younger perspective on a range of projects. Whenever I find the energy, I do try to make time for reading (I’ve recently gotten back into some fantasy novels), walking, listening to podcasts, rock climbing, writing and annoying my cat, Panda.

Let’s wrap up close to home. What does ethics mean to you and why are you interested in bringing it to the attention of young people?

To me, ethics is about learning to live with ourselves in a way that is sustainable. Part of that process is learning how to question ourselves, other people, systems and structures. It’s about identifying assumptions and patterns in our beliefs and behaviours and learning to discard or modify the unfounded ones.

I’m interested in bringing it to a younger audience because I think studying ethics and critical thinking is such an important part of developing the cognitive resources needed to make significant change in the world in a responsible and empathetic way. I’ve already seen firsthand, from being a Primary Ethics teacher, the immense good that this can do, so if I can help bring these resources into the brains of passionate teenagers then I think the world will be much better off.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Big thinker

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Big Thinker: Temple Grandin

WATCH

Society + Culture

Stan Grant: racism and the Australian dream

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Is masculinity fragile? On the whole, no. But things do change.

Explainer

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Gender

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

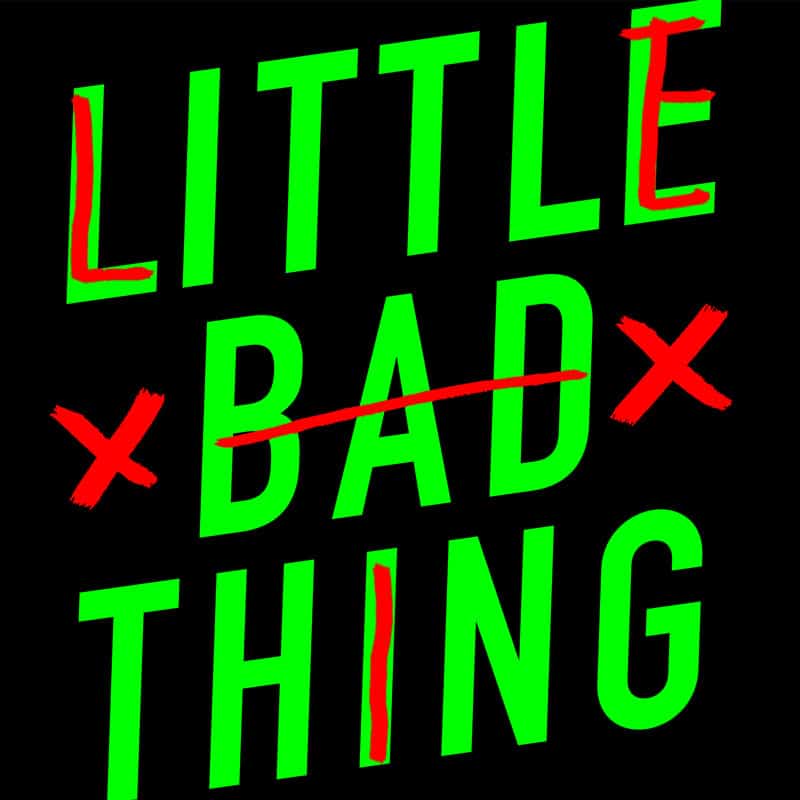

Little Bad Thing

A podcast series about the choices we wish we could undo

A podcast series about the choices we wish we could undo

A podcast series about the choices we wish we could undo

Each week, philosopher Eleanor Gordon-Smith interviews real people to revisit a moment in their life when they felt they didn’t do the right thing. What unfolds are honest stories of lying, cheating, consent, blame and forgiveness that ultimately reveal the complexities of being human.

“Most of the interesting stuff doesn’t happen under ideal circumstances – it happens in the dark, with the little lapses we’re taught to be ashamed of, to forget, or to write off. Little Bad Thing and the people who shared their stories with me bring those things to the surface.

“We’re all so busy concealing our mistakes for fear of judgement that we forget that other people have made the same ones and that there can be insight and connection in talking about them,” says Eleanor Gordon-Smith.

Smart, dark, wry and surprising, this is a podcast for anyone who’s ever experienced the conflict of a hard decision – or is still haunted by a small one.

Each episode runs 20 minutes and features a mix of narration, interview and general discussion.

Listen to the Little Bad Thing Trailer

SEASON ONE EPISODES

All In One Basket

Georgina was sub-letting an apartment and took a few items when she moved out – with the full intention of returning them to the owner when they came back. She just never told them she’d taken them, even when they returned home. Then on a night out, Georgina received a text from the owner, branding her a thief. At first, she thought it was an overreaction – she wasn’t a thief…was she?

Listen to Ep 1 on Apple or Spotify now.

Read more about the ethical themes of this episode:

Ethics Explainer: Moral imagination

Ignoring the people we don’t see

Why learning to be a good friend matters

Bystanders Standing By

Thomas was working as a checkout kid when it happened. His boss and fellow shelf-stackers had always had a problem with shoplifters. But that day was different. The culprit was a mentally handicapped shoplifter who they chased down, and Thomas’ boss did something terrible to him. Thomas spent years wondering why he just stood by. In this episode, he realises why.

Listen to Ep 2 on Apple or Spotify now.

Read more about the ethical themes of this episode:

Ethics Explainer: Akrasia – an Ancient Greek term for knowing the right thing and choosing not to do it.

Bystander intervention in Hannah Arendt’s article about the trial of Adolf Eichmann and coined the term “the banality of evil”.

Do The Right Thing

Lucia Osborne Crowley was raped when she was 15 years old. As an adult she decided to do something about what had happened – something that helped thousands of people, but changed her life forever. Some days she wishes she could go back to the world before she made that decision – even though she thinks it was the right one. If doing something is right, why does it sometimes feel so bad?

Listen to Ep 3 on Apple or Spotify now.

Read more about the ethical themes of this episode:

Lucia’s book

Denis Gentilin’s discussion of victims “finding their voice”.

Oscar Schwartz’s piece about what justice requires after sexual violence.

The Art of The Scam

David was just out of university, deep in debt, and eager for the chance to make money. He scored an internship at an investment firm which he quickly thought was fishy. But he would get a cut of any investment that he managed to source for them. That’s when he went to someone he already knew – and told them about an exciting business opportunity…

Listen to Ep 4 on Apple and Spotify now.

Read more about the ethical themes of this episode:

Sell out, burn out. Decisions that won’t let you sleep at night by Fiona Smith that looks at whether the business world has different codes of moral conduct from the ordinary world.

Why do good people do bad things by social psychologist Samuel Effron.

Two Kinds of Bully

Dan was trained in combat and having a bad day, so when he saw a stranger harassing a woman on the street, he went over to him ready to throw a punch if he needed to. At the time he thought he was on the side of justice – but when he got to the stranger, something happened that changed his mind. Months later he reflects on self-deceit and the perils of vigilante justice.

Listen to Ep 5 on Apple and Spotify now.

Read more about the ethical themes of this episode:

Shadow Values to find out more about the ways we can be guided by values that aren’t always visible to us.

Let’s unpack the notion of courage for more discussion of courage and what bravery involves.

The Sincerest Form of Flattery

Lukasz is a Polish font designer. He’s made some of the biggest fonts in the world. He fell in love with one particular font, but buyers kept abandoning it at the last minute. He was bereft at the thought of not finishing it until one day – a major company presented a way to get it finished – that would involve theft of another fellow font designer’s work.

Listen to Ep 6 on Apple and Spotify now.

Read more about the ethical themes of this episode:

Watch Michael Walzer explain “the problem of dirty hands” to learn more about the moral challenge of doing something wrong in exchange for something bigger.

The ethics of Damien Hirst’s use of indigenous art for more on art, theft, and ethics of design.

And a Toy Xylophone

Michelle Brazier broke up with her partner of 7 years by arriving home from a work trip, taking her toothbrush and leaving with a carry-on suitcase containing a couple of things. The break up took 5 minutes. Years later Michelle wonders why she didn’t feel able to have That Conversation.

Listen to Ep 7 on Apple and Spotify now.

Read more about the ethical themes of this episode:

Michelle Brazier’s comedy and music.

Ethics explainer on Vulnerability to explore the key themes of care, separation, and gently rejecting others in this episode.

A guide to having a difficult conversation.

All's Fair in Love and War

Simon Kennedy Jewel was in charge of distributing rations in a refugee camp in Central America. One day, he was given orders to stop providing food to people who didn’t have their ID card. Dozens went hungry. There was a riot. Back in Australia, Simon reflects on when trying to do good leads to a lot of bad, and how to rebuild when you lose your moral compass.

Listen to Ep 8 on Apple and Spotify now.

Read more about the ethical themes of this episode:

Ethics Explainer: Deontology – a school of ethical thought which emphasises principles for their own sake instead of because of their good effects.

A guide to making tough moral decisions.

How employers can help when their employees have to make these decisions.

Find out more about Ethi-call – a free counselling service.

Whats inside the guide?

WITH THANKS

Supported by donations from The Ferris Family Foundation and the Charles Warman Foundation.

If you like what we do and you want to help us make more, donate here or sign up to hear about our events and articles.

A production of The Ethics Centre. Mix and Sound Design by Bryce Halliday. Music by Breakmaster Cylinder & Blue Dot Sessions. Hosted and produced by Eleanor Gordon-Smith. Sound edits by Colin Ho, Executive Producer Danielle Harvey.

There’s something Australia can do to add $45b to the economy. It involves ethics.

There’s something Australia can do to add $45b to the economy. It involves ethics.

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + LeadershipSociety + Culture

BY The Ethics Centre 29 OCT 2020

Australia faces a perfect storm. An economic deficit, a global pandemic, an uncertain future of work, and long-term social and environmental change around the climate crisis and reconciliation with Indigenous Australians to name but a few.

Adding to this magnitude of challenges are the low levels of trust Australians have in our leaders and our neighbours. In fact, research has found that only 54% of Australians generally trust people they interact with, and as a nation we score ‘somewhat ethical’ on the Governance Institute’s Ethics Index.

How do we navigate the road ahead? One thing is abundantly clear: we need better ethics. That’s why we commissioned Deloitte Access Economics to find out the economic benefits of improving ethics in Australia.

The outcome is The Ethical Advantage, a report that uses three new types of economic modelling and a review of extensive data sets and research sources to mount the case for pursuing higher levels of ethical behaviour across society.

For the first time, the report quantifies the benefits of ethics for individuals and for the nation. The ethical advantage is in, and the findings are compelling. They include:

A stronger economy: If Australia was to improve ethical behaviour, leading to an increase in trust, – average annual incomes would increase by approximately $1,800. This in turn would equate to a net increase in total incomes of approximately $45 billion.

More money in Australians pockets: Improved ethics leads to higher wages, consistent with an improvement in labour and business productivity. A 10% increase in ethical behaviour is associated with up to a 6.6% in individual wages.

Better returns for Australian businesses: Unethical behaviour leads to poorer financial outcomes for business. Increasing a firm’s performance based on ethical perceptions, can increase return on assets by approximately 7%.

Increased human flourishing: People would benefit from improved mental and physical health. There is evidence that a 10% improvement in awareness of others’ ethical behaviour is associated with a greater understanding one’s own mental health.

The report’s lead author and Deloitte Access Economics partner, Mr John O’Mahony, said:

“No one would seriously argue that pursuing higher levels of ethical behaviour and focus was a bad thing, but articulating the benefits of stronger ethics is more challenging.”

“Our report examines the case for improving ethics as a way of addressing these broader economic and social challenges – and the nature and extent of the benefits that would accrue to the nation if we got this right.”

The report also identifies five inter–linked areas for improvement for Australia and its approach to ethics, supported by 30 individual initiatives:

- Developing an Ethical Infrastructure Index

- Elevating public discussions about ethics

- Strengthening ethics in education

- Embedding ethics within institutions

- Supporting ethics in government and the regulatory framework

The findings and recommendations demonstrate the value of The Ethics Centre’s continued contribution to Australian life. For thirty years, The Ethics Centre has aimed to elevate ethics within public debate, organisations, education programs and public policy. Executive Director of The Ethics Centre, Dr Simon Longstaff said the findings validate the impact of those activities and reveals the potential that can be unlocked with greater support.

“The compelling moral argument that ethical behaviour binds a society and its institutions in a common good is now, thanks to Deloitte Access Economics’ research and modelling, also a compelling economic argument. Best of all, we need not be perfect – just better.”

A copy of The Ethical Advantage can be found at this link.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture

We are pitching for your pledge

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships

Facing tough decisions around redundancies? Here are some things to consider

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Health + Wellbeing

Navigating a workforce through stressful times

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture

FODI returns: Why we need a sanctuary to explore dangerous ideas

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Meet Eleanor, our new philosopher in residence

Meet Eleanor, our new philosopher in residence

Opinion + AnalysisRelationshipsSociety + Culture

BY The Ethics Centre 23 SEP 2020

At TEC, we firmly believe ethics is a team sport. It’s a conversation about how we should act, live, treat others and be treated in return.

That means we need a range of people participating in the conversation. That’s why last year, we asked for funding support to bring another philosopher into our team. Thanks to our donors, we are excited to share that we have recently appointed Eleanor Gordon-Smith as a Fellow. Already established as one of Australia’s leading young thinkers, Eleanor is a published author, broadcaster and in demand speaker. She’s also currently reading for her PHD at Princeton University. To welcome her on board and introduce her to you, our community, we sat down for a brief get-to-know-you chat with her.

Tell us, what attracted you to becoming a philosopher?

I remember sitting in my first philosophy class and feeling like this was what thinking should really be like. I left knowing less than I thought I did when I arrived – all my other classes were about the legislative agenda around human rights and my philosophy class said wait, what’s a right and what counts as human? I loved the ability to ask those questions and from that day on it’s always felt like that’s where the real action is: the deep questions that we too easily take for granted.

Do you specialise in a key area or areas?

I cross-specialise in ethics, language, and epistemology [the study of knowledge]. In all three areas I am interested in the powers we can only have because we are social creatures. I work on moral powers that we can only exercise in social settings – such as consent, and promise – how linguistic meaning can be constructed and destroyed by social relationships, and how being embedded in societies can facilitate or disrupt our processes of gaining knowledge. The uniting theme across my work is that we depend on each other for many of our most important abilities and powers, such as speaking, learning, or coming up with moral frameworks, and yet a lot of the time other people are very bad. So what are we to do, if we rely on each other for our most foundational abilities but frequently “each other” is the source of our problems? So far I only have the question. But that’s where all good philosophy starts…

Sounds like a phenomenal place to start. Now let’s have a fan-girl moment. Who is your favourite philosopher?

There are too many to name but Rae Langton, who spent a lot of time in Australia, is a huge inspiration for me, and I like to think about how to precissify Robert Adams’ remark which seems to me to get to the heart of moral philosophy: “we ought, in general, to be treated better than we deserve”.

Let’s jump over to COVID and restrictions, the impact these are having on our lives, our interactions, how we work and so on. What do you hope we learn or gain from this experience?

Truthfully I think the most we can hope for is a greater appreciation for the profound fragility of the things that normally keep us functioning. Our friendships, entertainment, ways of being in the world, all so easily threatened by simply not being able to leave the house very much. I have found that very humbling, and very difficult. I hope also we can learn to be a little more compassionate with ourselves about the fact that we are all creatures who need to live and will one day die. Before Covid, it was very easy to see each other and ourselves as our jobs, or athletic achievements, or how we’re measuring up to a set of criteria about how our lives “should” be going. Seeing everybody’s houses and children and needs via Zoom will I hope let us be compassionate about the fact that we all have them, and there’s no shame in taking care of them.

We’ve all had a guilty pleasure of sorts during the pandemic. Can you share with us yours?

I bought a robot vacuum cleaner and I like to follow him around and tell him he’s missed a spot.

Amazing. Let’s get to know you better. What is a standard day in your life?

I read a lot, work on [podcast] episode plans, put several thousand post-it notes on the wall – each one a piece of tape from an interview, a fact, a piece of theory, a well-phrased, or a scene – and rearrange them until I can see a story unfolding alongside a philosophical idea. I read philosophy, listen to a lot of radio and podcasts because there are so many clever people in that sphere whose work I admire, and try to stop by 9pm. Although if I’m honest, that’s rare these days.

You wrote a book – what is it about?

Stop Being Reasonable. It’s a series of true stories about how we change our minds in high-stakes moments and how rarely that measures up to our ideal of rationality. Each chapter features interviews I conducted with someone about a moment in their life that they changed their mind in a really drastic way: a man who left a cult, a woman who questioned her own memory of being abused, a man who changed his mind about his entire personality after appearing on reality TV, someone who learned their family wasn’t really their family, and so on. Each story highlights a sometimes-maligned strategy for reasoning that many of us turn out to use all the time, especially when it really matters: believing other people, trusting our gut, thinking emotionally, and so on. The book is a plea for a more capacious ideal of rationality, such that these things ‘count’ as rational thinking as well as the emotionless first-principles reasoning we usually associate with that term.

Let’s finish up close to home. What does ethics mean to you?

People sometimes think ethical thinking promises a set of answers. It might, but I think it’s much more about learning to ask a different set of questions. So many of our disagreements and deepest divisions are built on argumentative frameworks that we almost never dredge to the surface and examine. We take things for granted about what matters, why, how to measure it, and what follows from the fact that those things matter. Learning to think ethically is about examining those things – about realising which systems of value we subscribe to by accident, and trying to make our value systems more deliberate.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Society + Culture

Banking royal commission: The world of loopholes has ended

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Are there limits to forgiveness?

Explainer

Relationships, Science + Technology

Ethics Explainer: Post-Humanism

Big thinker

Relationships

Big Thinker: Jelaluddin Rumi

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

FODI digital returns for three dangerous conversations

FODI digital returns for three dangerous conversations

Opinion + AnalysisSociety + Culture

BY The Ethics Centre 20 AUG 2020

The Festival of Dangerous Ideas traverses the cracks of our society across three flagship digital events this September and October.

We are living through a period of heightened fear and anxiety. The global pandemic has superheated three systemic problems that were already set to boil: government control of information, racism and climate change.

The three sessions will be streamed live on festivalofdangerousidea.com, with live interaction and questions from the audience. Ticket prices range from $10-$15 or $30 for all three conversations.

Our Festival Director, Danielle Harvey, has carefully curated these three speakers to for this dangerous time. In speaking about the programming, she said “the fallout from the pandemic is changing politics, economics and the every day so significantly.

FODI is a provocateur of big thinking, and it’s back to ask us: what should we be doing now to prepare for a post-pandemic landscape? And has COVID-19 offered opportunity or hindrance to tackling some of the biggest issues of our time in a new and profound way?”

Live stream sessions include:

-

Dangerous Fictions, Marcia Langton, 10 September 2020, 7PM

Langston is a fearless truth-teller who challenges the dangerous orthodoxies of a society that seems incapable of making peace with the truth of its own past.

-

Surveillance States, Edward Snowden, 24 September 2020, 7PM

Snowden asks us to consider the possibility that we may have more to fear from our own governments than from any external threat – and that our liberties have already been lost.

-

The Uninhabitable Earth, David Wallace-Wells, 11 October 2020, 11am

Wallace-Wells says there is no going back from the climate crisis and suggests the greatest challenge is navigating the future in a world that can’t agree how to face it together.

Challenging us all to stop and pay attention, Executive Director of The Ethics Centre and Co-Founder of FODI, Simon Longstaff, said these are pivotal issues are demanding creative solutions.

“The urgency of the moment might seem to demand every moment of our attention, the reality is that this is precisely the time when we need to look beyond the boundaries of the pandemic and come together and … think!”

These events follow on from the first FODI digital series in May which featured Norman Swan, David Sinclair, Claire Wardle, Kevin Rudd, Vicky Xu, Masha Gessen and Stan Grant. Past conversations are available on demand via www.festivalofdangerousidea.com.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Science + Technology, Society + Culture

5 things we learnt from The Festival of Dangerous Ideas 2022

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture

8 questions with FODI Festival Director, Danielle Harvey

Big thinker

Society + Culture

Big Thinker: Marcus Aurelius

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Society + Culture