Five subversive philosophers throughout the ages

Philosophy helps us bring important questions, ideas and beliefs to the table and work towards understanding. It encourages us to engage in examination and to think critically about the world.

Here are five philosophers from various time periods and walks of life that demonstrate the importance and impact of critical thinking throughout history.

Ruha Benjamin

Ruha Benjamin (1978–present), while not a self-professed philosopher, uses her expertise in sociology to question and criticise the relationship between innovation and equity. Benjamin’s works focus on the intersection of race, justice and technology, highlighting the ways that discrimination is embedded in technology, meaning that technological progress often heightens racial inequalities instead of addressing them. One of the most prominent of these is her analysis of how “neutral” algorithms can replicate or worsen racial bias because they are shaped by their creators’ (often unconscious) biases.

“The default setting of innovation is inequity.”

J. J. C. Smart

J.J.C. Smart (1920-2012) was a British-Australian philosopher with far-reaching interests across numerous subfields of philosophy. Smart was a Foundation Fellow of the Australian Academy of the Humanities at its establishment in 1969. In 1990, he was awarded the Companion in the General Division of the Order of Australia. In ethics, Smart defended “extreme” act utilitarianism – a type of consequentialism – and outwardly opposed rule utilitarianism, dubbing it “superstitious rule workshop”, contributing to its steadily decline in popularity.

“That anything should exist at all does seem to me a matter for the deepest awe. But whether other people feel this sort of awe, and whether they or I ought to, is another question. I think we ought to.”

Elisabeth of the Bohemia

Princess Elisabeth of Bohemia (1618–1680) was a philosopher who is best known for her correspondence with René Descartes. After meeting him while he was visiting in Holland, the two exchanged letters for several years. In the letters, Elisabeth questions Descartes’ early account of mind-body dualism (the idea that the mind can exist outside of the body), wondering how something immaterial can have any effect on the body. Her discussion with Descartes has been cited as the first argument for physicalism. In later letters, her criticisms prompted him to develop his moral philosophy – specifically his account of virtue. Elisabeth has featured as a key subject in feminist history of philosophy, as she was at once a brilliant and critical thinker, while also having to live with the limitations imposed on women at the time.

“Inform your intellect, and follow the good it acquaints you with.”

Socrates

Socrates (470 BCE–399 BCE) is widely considered to be one of the founders of Western philosophy, though almost all we know of him is derived from the work of others, like Plato, Xenophon and Aristophanes. Socrates is known for bringing about a huge shift in philosophy away from physics and toward practical ethics – thinking about how we do live and how we should live in the world. Socrates is also known for bringing these issues to the public. Ultimately, his public encouragement of questioning and challenging the status quo is what got him killed. Luckily, his insights were taken down, taught and developed for centuries to come.

“The unexamined life is not worth living.”

Francesca Minerva

Francesca Minerva is a contemporary bioethicist whose work includes medical ethics, technological ethics, discrimination and academic freedom. One of Minerva’s most controversial (if misunderstood) contributions to ethics is her paper, co-written with Alberto Giubilini in 2012, titled “After-birth Abortion: why should the baby live?”. In it, the pair argue that if it’s permissible to abort a foetus for a reason, then it should also be permissible to “abort” (i.e., euthanise) a newborn for the same reason. Minerva is also a large proponent of academic freedom and co-founded the Journal of Controversial Ideas in an effort to eliminate the social pressures that threaten to impede academic progress.

“The proper task of an academic is to strive to be free and unbiased, and we must eliminate pressures that impede this.”

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Big Thinker: Plato

Plato (~428 BCE—348 BCE) is commonly considered to be one of the most influential writers in the history of philosophy.

Along with his teacher, Socrates, and student, Aristotle, Plato is among the most famous names in Western philosophy – and for good reason. He is one of the only ancient philosophers whose entire body of work has passed through history in-tact over the last 2,400 years, which has influenced an incredibly wide array of fields including ethics, epistemology, politics and mathematics.

Plato was a citizen of Athens with high status, born to an influential, aristocratic family. This led him to be well-educated in several fields – though he was also a wrestler!

Influences and writing

Plato was hugely influenced by his teacher, Socrates. Luckily, too, because a large portion of what we know about Socrates comes from Plato’s writings. In fact, Plato dedicated an entire text, The Apology of Socrates, to giving a defense of Socrates during his trial and execution.

The vast majority of Plato’s work is written in the form of a dialogue – a running exchange between a few (often just two) people.

Socrates is frequently the main speaker in these dialogues, where he uses consistent questioning to tease out thoughts, reasons and lessons from his “interlocutors”. You might have heard this referred to as the “Socratic method”.

This method of dialogue where one person develops a conversation with another through questioning is also referred to as dialectical. This sort of dialogue is supposed to be a way to criticise someone’s reasoning by forcing them to reflect on their assumptions or implicit arguments. It’s also argued to be a method of intuition and sometimes simply to cause puzzlement in the reader because it’s unclear whether some questions are asked with a sense of irony.

Plato’s revolutionary ideas span many fields. In epistemology, he contrasts knowledge (episteme) with opinion (doxa). Interestingly, he says that knowledge is a matter of recollection rather than discovery. He is also said to be the first person to suggest a definition of knowledge as “justified true belief”.

Plato was also very vocal about politics, though many of his thoughts are difficult to attribute to him given the third person dialogue form of his writings. Regardless, he seems to have had very impactful perspectives on the importance of philosophy in politics:

“Until philosophers rule as kings or those who are now called kings and leading men genuinely and adequately philosophize, that is, until political power and philosophy entirely coincide, while the many natures who at present pursue either one exclusively are forcibly prevented from doing so, cities will have no rest from evils, … nor, I think, will the human race.”

Allegories

You might have also heard of The Allegory of the Cave. Plato reflected on the idea that most people aren’t interested in lengthy philosophical discourse and are more drawn to storytelling. The Allegory of the Cave is one of several stories that Plato created with the intent to impart moral or political questions or lessons to the reader.

The Ring of Gyges is another story of Plato’s that revolves around a ring with the ability to make the wearer invisible. A character in the Republic proposes this idea and uses it to discuss the ethical consequences of the item – namely, whether the wearer would be happy to commit injustices with the anonymity of the ring.

This kind of ethical dilemma mirrors contemporary debates about superpowers or anonymity on the internet. If we aren’t able to be held accountable, and we know it, how is that likely to change our feelings about right and wrong?

The Academy

The Academy was the first institution of higher learning in the Western world. It was founded by Plato some time after he turned 30, after inheriting the property. It was free and open to the public, at least during Plato’s time, and study there consisted of conversations and problems posed by Plato and other senior members, as well as the occasional lecture. The Academy is famously where Aristotle was educated.

After Plato’s death, the Academy continued to be led by various philosophers until it was destroyed in 86 BC during the First Mithridatic War. However, Platonism (the philosophy of Plato) continued to be taught and revived in various ways and has had a lasting impact on many areas of life continuing today.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

WATCH

Relationships

What is ethics?

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Teleology

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

How to give your new year’s resolutions more meaning

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

Meet Daniel, helping us take ethics to the next generation

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Big Thinker: Francesca Minerva

Big Thinker: Francesca Minerva

Big thinkerPolitics + Human RightsScience + Technology

BY The Ethics Centre 27 OCT 2021

Francesca Minerva is a contemporary bioethicist whose work largely includes medical ethics, technological ethics, discrimination and academic freedom.

A research Fellow at the University of Milan and the co-founder and co-editor of the Journal of Controversial Ideas, Francesca Minerva has published extensively within the field of applied ethics on topics such as cryonics, academic freedom, conscientious objection, and lookism. But she is best (if somewhat reluctantly) known for her work on the topic of abortion.

Controversy over ‘After-birth Abortion’

In 2012, Minerva and Alberto Giubilini wrote a paper entitled ‘After-birth Abortion: why should the baby live?’ The paper discussed the moral status of foetuses and newborn babies and argued that after-birth abortion (more commonly known as infanticide) should be permissible in all situations where abortion is permissible.

In the parts of the world where it is legal, abortion may be requested for a number of reasons, some having to do with the mother’s well-being (e.g., if the pregnancy poses a risk to her health, or causes emotional or financial stress), others having to do with the foetus itself (e.g., if the foetus is identified as having a chromosomal or developmental abnormality).

Minerva and Giubilini argue that if it’s permissible to abort a foetus for one of these reasons, then it should also be permissible to “abort” (i.e., euthanise) a newborn for one of these reasons.

This is because they argue that foetuses and newborns have the same moral status: Neither foetuses nor newborns are “persons” capable of attributing (even) basic value to their life such that being deprived of this life would cause them harm.

This is not an entirely original argument. Minerva and Giubilini were mainly elaborating on points made decades ago by Peter Singer, Michael Tooley and Jeff McMahan. And yet, ‘After-birth Abortion’ drew the attention of newspapers, blogs and social media users all over the world and Minerva and Giubilini quickly found themselves at the centre of a media storm.

In the months following the publication, they received hundreds of angry emails from the public, including a number of death threats.

The controversy also impacted their careers: Giubilini had a job offer rescinded and Minerva was not offered a permanent job in a philosophy department because members of the department “were strongly opposed to the views expressed in the paper”. Also, since most of the threatening emails were sent from the USA, they were advised not to travel to the USA for at least a year, meaning that they could not attend or speak at academic conferences being held there during that period.

So why did ‘After-birth Abortion’ attract so much attention compared to older publications on the same topic? While the subject matter is undoubtedly controversial, Minerva believes the circulation of the paper had more to do with the internet than with the paper itself.

Academic Freedom and the Journal of Controversial Ideas

“The Web has changed the way ideas circulate.” Ideas spread more quickly and reach a much wider audience than they used to. There is also no way to ensure that these ideas are reported correctly, particularly when they are picked up by blogs or discussed on social media. As a result, ideas may be distorted or sensationalised, and the original intent or reasoning behind the idea may be lost.

Minerva is particularly concerned about the impact that this may have on research, believing that fear of a media frenzy may discourage some academics from working on topics that could be seen as controversial. She believes that, in this way, the internet and mass media may pose a threat to academic freedom.

“Research is, among many other things, about challenging common sense, testing the soundness of ideas that are widely accepted as part of received wisdom, or because they are held by the majority of people, or by people in power. The proper task of an academic is to strive to be free and unbiased, and we must eliminate pressures that impede this.”

In an effort to eliminate some of this pressure, Minerva co-founded the Journal of Controversial Ideas, alongside Peter Singer and Jeff McMahan. As the name suggests, the journal encourages submissions on controversial topics, but allows authors to publish under a pseudonym should they wish to.

The hope is that by allowing authors to publish under a false name, academics will be empowered to explore all kinds of ideas without fearing for their well-being or their career. But ultimately, as Minerva says, “society will benefit from the lively debate and freedom in academia, which is one of the main incubators of discoveries, innovations and interesting research.”

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Big thinker

Politics + Human Rights

Big Thinker: Ayaan Hirsi Ali

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

CoronaVirus reveals our sinophobic underbelly

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Calling out for justice

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Science + Technology

People first: How to make our digital services work for us rather than against us

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Big Thinker: Judith Butler

Big Thinker: Judith Butler

Big thinkerHealth + WellbeingPolitics + Human RightsRelationships

BY The Ethics Centre 19 OCT 2021

Judith Butler (1956—present) is an American academic and activist, who has made considerable contributions to philosophy, literature, gender and feminist studies.

They are the Maxine Elliot Professor in the Department of Comparative Literature and the Program of Critical Theory at the University of California, Berkeley and holds the Hannah Arendt Chair at the European Graduate School in Sass Fee, Switzerland.

Although Butler has an impressive number of publications to their name, they are best known for their book, Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity (1989; 1990).

Gender Trouble

Gender Trouble explores the traditional understandings of sex and gender in feminist theory. Butler argues against the view that gender is based on (or follows from) our biology, claiming instead that gender is produced by performance – that we construct gender by behaving and expressing ourselves in certain ways.

This “gender performativity” has been interpreted in different ways. Some have taken performativity to mean that gender is determined by society and therefore completely outside of the individual’s control (i.e., you are the gender you have been assigned).

Others have understood performativity to mean that gender can be chosen or changed at will, since it has no biological basis. Members of the trans community have critiqued this understanding, saying that conceiving of gender as something that can be changed voluntarily makes it seem superficial or fake and risks undermining how important someone’s gender identity can be to their sense of self.

More recently, Butler has clarified their own understanding of gender performativity, stating:

Butler’s understanding of gender performativity lies somewhere in between the two previous views. For Butler, gender is not something that is fixed by society and unalterable on an individual level, but it is also not something superficial that can be changed like a piece of clothing. Instead, gender is created through sustained practices that make gender appear as though it’s something natural or internal to us, but really these practices are influenced and regulated by society and culture. By recognising this, Butler says, we can collectively start to change gender norms so that we can each find a way to live more authentically.

Though the term ‘non-binary’ did not exist at the time Butler published Gender Trouble, in recent years Butler has changed their legal gender to non-binary and uses she/they pronouns.

After Gender Trouble

Gender Trouble had a profound influence over the development of feminist theory and is widely considered to be one of the founding texts of queer theory. Since its publication in 1989, Gender Trouble has been translated into 27 languages and has become a staple text for feminist and gender studies courses all over the world.

As a result, Butler has achieved a fame that transcends the academic community – and it hasn’t always been positive.

For some people, Butler’s views are considered dangerous or threatening to the traditional way of life. In 2017, evangelical Christian protestors burnt an effigy of Butler outside an academic conference they were attending in Brazil, while chanting “take your ideology to hell.”

Despite this, Butler continues to write and speak about gender, feminist and queer issues and is active in the resistance against the anti-gender movement – an international movement that opposes gender equality, LGBTQIA+ rights and sexual and reproductive freedoms.

Butler has, for many years, been a vocal advocate for the rights of marginalised people and has been active in anti-war and anti-racism movements.

Their most recent book, The Force of Non-violence: An Ethico-Political Bind (2020), argues that social inequality cannot be separated from our understanding of violence. For Butler, violence is not just swinging fists and wielding weapons. Violence is any action (or inaction) that harms another – including public policies and institutional practices that create social inequalities.

In response to this kind of violence, Butler advocates nonviolence. Importantly, however, Butler does not understand nonviolence as something passive. Nonviolence requires an aggressive commitment to radical equality and an “opposition to biopolitical forms of racism and war logics that regularly distinguish lives worth safeguarding from those that are not.”

Butler wants us to recognise that we are all in this together and build a world that is reflective of this – a world that is committed to radical equality.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

Hey liberals, do you like this hegemony of ours? Then you’d better damn well act like it

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

When human rights complicate religious freedom and secular law

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Virtue Ethics

LISTEN

Health + Wellbeing, Society + Culture

Life and Debt

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Seven Influencers of Science Who Helped Change the World

Seven Influencers of Science Who Helped Change the World

Big thinkerScience + Technology

BY The Ethics Centre 18 AUG 2021

We’re all familiar with the Einsteins and Hawkings of history, but there are many who have influenced the direction and development of science. Here are seven scientists and philosophers who have shaped how science is practiced today.

Tim Berners-Lee

Sir Timothy Berners-Lee (1955-present) is an English computer scientist. Most notably, he is the inventor of the World Wide Web and the first web browser. If not for his innovative insight and altruistic intent (he gave away the idea for free!), the way you’re viewing this very page may have been completely different. These days, Berners-Lee is fighting to save his vision. The Web has transformed, he says, and is being abused in ways he always feared – from political interference to social control. The only way forward is pushing for ethical design and pushing back against web monopolisation.

Legacy: The World Wide Web as we know it.

Jane Goodall

Dame Jane Goodall (1934-present) is an English primatologist and anthropologist. Over 60 years ago, Goodall entered the forest of Gombe Stream National Park and made the ground-breaking discovery that chimpanzees make and use tools and exhibit other human-like behaviour, including armed conflict. Since then, she has spent decades continuing her extensive and hands-on research with chimpanzees, written a plethora of books, founded the Jane Goodall Institute to scale up conservation efforts, and is forever changing the way humans relate to animals.

Legacy: “Only if we understand, will we care. Only if we care, will we help. Only if we help, shall all be saved.”

Karl Popper

Sir Karl Popper (1902-1994) was an Austrian-British philosopher, academic and social commentator. He is best known as one of the greatest philosophers of science in the twentieth century, having contributed a new and novel way of thinking about the methodology of science. Against the prevailing empiricist idea that rationally acceptable beliefs can only be justified through direct experience, Popper proposed the opposite. In fact, Popper argued, theories can never be proven to be true. The best we can do as humans is ensure that they are able to be false and continue testing them for exceptions, even as we use these assumptions to further our knowledge. One of Popper’s most enduring thoughts is that we should rationally prefer the simplest theory that explains the relevant facts.

Legacy: The idea that to be scientific is to be fallible.

Marie Curie

Marie Curie (1867-1934) was a Polish-French physicist and chemist. She was a pioneer of radioactivity research, coining the term with her husband, and discovered and named the new elements “polonium” and “radium”. During the course of her extensive career, she was the first woman to be awarded a Nobel Prize, and the first to be awarded two Nobel Prizes in two scientific fields: physics and chemistry. Due to the underfunded research conditions of time and ignorance about the danger of radiation exposure, it’s thought that a large factor in her death was radiation sickness.

Legacy: Discovering polonium and radium, pioneering research into the use of radiation in medicine and fundamentally changing our understanding of radioactivity.

René Descartes

René Descartes (1596-1650) was a French philosopher, mathematician and scientist. Descartes is most widely known for his philosophy – including the famous “I think, therefore I am” – but he was also an influential mathematician and scientist. Descartes’ possibly most enduring legacy is something high school students are very familiar with today – coordinate geometry. Also known as analytic or Cartesian geometry, this is the use of algebra and a coordinates graph with x and y axes to find unknown measurements. Descartes was also interested in physics, and it is thought that he had great influence on the direction that a young Isaac Newton took with his research – Newton’s laws of motion were eventually modelled after Descartes’ three laws of motion, outlined in Principles of Philosophy. In his essay on optics, he independently discovered the law of reflection – the mathematical explanation of the angle at which light waves are reflected.

Legacy: “The seeker after truth must, once in the course of his life, doubt everything, as far as is possible.”

Rosalind Franklin

Rosalind Franklin (1920-1958) was an English chemist and X-ray crystallographer who is most famous for her posthumous recognition. During her life, including in her PhD thesis, she researched the properties and utility of coal, and the structure of various viruses. She is now often referred to as “the forgotten heroine” for the lack of recognition she received for her contributions to the discovery of the structure of DNA. Even one of the recipients of the Nobel Prize for the discovery of the DNA double helix suggested that Franklin should have been among the recipients, but posthumous nominations were very rare. Unfortunately, this was not her only posthumous brush with a Nobel Prize, either. One day before she and her team member were to unveil the structure of a new virus affecting tobacco farms, Franklin died of ovarian cancer. Over two decades later, her team member went on to win the Nobel Prize in Chemistry for the continued research on the virus. Since her death, she has been recognised with over 50 varying awards and honours.

Legacy: Foundational research that informed the discovery of the structure of DNA, coal and graphite.

Noam Chomsky

Noam Chomsky (1928-present) is an American linguist, philosopher, cognitive scientist and social/political critic. While Chomsky may be better known as a political dissident and social critic, he also played a foundational role in the development of modern linguistics and founded a new field: cognitive science, the scientific study of the mind. Chomsky’s research and criticism of behaviourism saw the decline in behaviourist psychology, and his interdisciplinary work in linguistics and cognitive science has gone on to influence advancements in a variety of fields including computer science, immunology and music theory.

Legacy: Establishing cognitive science as a formal scientific field and inciting the fall of behaviourism.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

WATCH

Business + Leadership, Climate + Environment, Science + Technology

How to build good technology

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Science + Technology

Big tech knows too much about us. Here’s why Australia is in the perfect position to change that

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Science + Technology

Making friends with machines

Opinion + Analysis

Science + Technology, Society + Culture

The terrible ethics of nuclear weapons

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Big Thinker: Immanuel Kant

Immanuel Kant (1724—1804) was a transformative figure in modern Western philosophy due to his ground-breaking work in metaphysics and ethics.

He was one of the most influential philosophers of the 18th century, and his work in metaphysics and ethics have had a lasting impact to this day.

One of Kant’s greatest contributions to philosophy was his moral theory, deontology, which judges actions according to whether they adhere to a valid rule rather than the outcome of the action.

According to Kant’s theory, if you follow a valid moral rule, like “do not lie”, and it ends up with people getting harmed, then you’ve still done the right thing.

Deontology has since become one of the “big three” moral frameworks in the Western tradition, along with virtue ethics (based on Aristotle’s work) and consequentialism (exemplified by utilitarianism).

The will

Kant argued that morality cannot be based on our emotions or experience of the world, because this would leave it weak and subjective, and lacking the unconditional obligation that he believed was central to moral law.

“Every one must admit that a law has to carry with it absolute necessity if it is to be valid morally – valid, that is, as a ground of obligation,” he wrote.

His concern was that without this sense of unconditional obligation, a moral rule like ‘do not lie’ could compete with and be overridden by other concerns, like someone deciding they could lie because it suits their interests to do so, and they value their interests more than morality.

Rather, Kant argued that morality must be based on reason, which alone can provide the unconditional necessity that makes morality override our subjective interests.

Kant’s starting point was with our very nature, as inherently rational beings with ‘free will.’ He argued that it was this will that sets us apart as ’persons’ rather than ’things’ in the world, which are at the mercy of causal forces.

Our will gives us the ability to not only decide how to achieve our ends, but also about which ends to pursue; that’s just what freedom means. However, Kant argued that when we understand our nature as rational beings, we will understand that reason commands us to behave in a certain way, and this could form the basis of objective moral law.

The Categorical Imperative

Kant drew a famous distinction between different types of commands, or imperatives, which direct us how to act. One type are hypothetical imperatives.

So, one hypothetical imperative might say if you want to get to the 5:05 PM bus on time, then you must leave home no later than 5 p.m. Many moral systems of his time were effectively based on hypothetical imperatives, with the ends being things like achieving happiness or satisfying our interests.

However, Kant believed that such hypothetical imperatives could not be the basis of morality, as morality must bind us to act unconditionally and irrespective of any other ends we might have. Hence, someone who followed hypothetical imperatives in order to achieve ends like satisfying their desires or to avoid punishment was not acting morally.

He contrasted these with categorical imperatives do bind us unconditionally, no matter what other ends we might have. Kant argued that morality must be made up of categorical imperatives, as these are the only rules that can give morality its unconditional necessity.

“If duty is a concept which is to have meaning and real legislative authority for our actions, this can be expressed only in categorical imperatives and by no means in hypothetical ones,” he wrote.

The question becomes: where do categorical imperatives come from? Kant argued that there is really only one categorical imperative, and it is derived from our very nature as rational agents.

Once we abstract away all the contingent circumstances and subjective desires that people have, all we’re left with is our rational nature, which is something shared by all persons with a will. This objective point of view, stripped of all subjectivity, treats all rational agents equally, thus any imperative that directs them must apply universally.

From this Kant arrived at the categorical imperative, which is usually stated as “act only according to a maxim by which you can at the same time will that it shall become a general law”. This made all moral commands universal, so if something was wrong for me, then it must be wrong for all rational beings at all times.

This categorical imperative became the basis of all of Kant’s moral laws, effectively enshrining a particularly rarefied version of the Golden Rule.

Kingdom of Ends

Because we are inherently rational agents, we are both the authors and the subjects of the moral law. As such, Kant said that every person – indeed, every rational being – is an “end in himself, not merely as a means for arbitrary use by this or that will”.

This means we must treat all rational beings as ends in themselves and not just as means to achieve whatever ends we might have.

So, Kant argued, if every rational agent were to obey the categorical imperative, and treat everyone else as ends and not means, then it would lead to what he called the “kingdom of ends.”

It’s a kingdom in the sense that it’s a union of individuals who are all acting under a common law, and in this case the law is the categorical imperative, which urges everyone to treat everyone else as an end in themselves.

Kant admitted that this would be something of a moral utopia, but he put it forward as a vision for what a truly rational moral society might look like.

Controversy and Influence

Kant’s deontological ethics has been hugely influential but also controversial, being criticised by many philosophers as being based on an unrealistic conception of human rationality as well as being overly inflexible.

For example, Kant argued that it was always wrong to lie, because if one were to lie it would effectively endorse lying for everyone, and this would violate people’s rational autonomy.

However, we can imagine some situations where lying might be considered to be the right thing to do, such as lying to a prospective murderer in order to conceal their potential victims. Not to mention lying to one’s partner about their sartorial choices in order to maintain a harmonious domestic environment.

This is why many ethical consequentialists, who believe that it’s outcomes that really matter, have been known to gnash their teeth at the prospect that Kant demands we never lie.

Some thinkers have also – perhaps uncharitably – said that Kant effectively remade a kind of divine command theory of morality, which was popular in his Lutheran Christian community, except he replaced God with Reason (and even then, snuck a bit of God in on the side).

Kant’s philosophy has proven to be tremendously influential. His synthesis of empiricism and rationalism proved to be a breakthrough at the time, and his moral theory still has ardent defenders to this day.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships

The twin foundations of leadership

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Why listening to people we disagree with can expand our worldview

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships, Society + Culture

Education is more than an employment outcome

Big thinker

Relationships

Big Thinker: bell hooks

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Seven Female Philosophers You Should Know About

Seven Female Philosophers You Should Know About

Big thinkerRelationships

BY The Ethics Centre 8 MAR 2021

There’s no question that philosophy is littered with the workings of male minds. What’s less known are the many brilliant women whose contributions throughout history have shaped our world today. Here are seven female philosophers to celebrate this International Women’s Day.

Mary Wollstonecraft

Mary Wollstonecraft (1759-1797) was a writer, philosopher and social activist. Wollstonecraft’s manifesto is 225+ years old, but far from obsolete. She passionately articulated for women to have equal rights to men in A Vindication of the Rights of Woman in 1792, a century before the term feminism was coined. In a social system where women were “kept in ignorance” by the socioeconomic necessity of marriage and a lack of formal education, Wollstonecraft advocated for a free national schooling system where girls and boys would be taught together. The word patriarchy was not available to Wollstonecraft, yet she argued men were invested in maintaining a society where they held power and excluded women.

“My own sex, I hope, will excuse me, if I treat them like rational creatures, instead of flattering their fascinating graces, and viewing them as if they were in a state of perpetual childhood, unable to stand alone.”

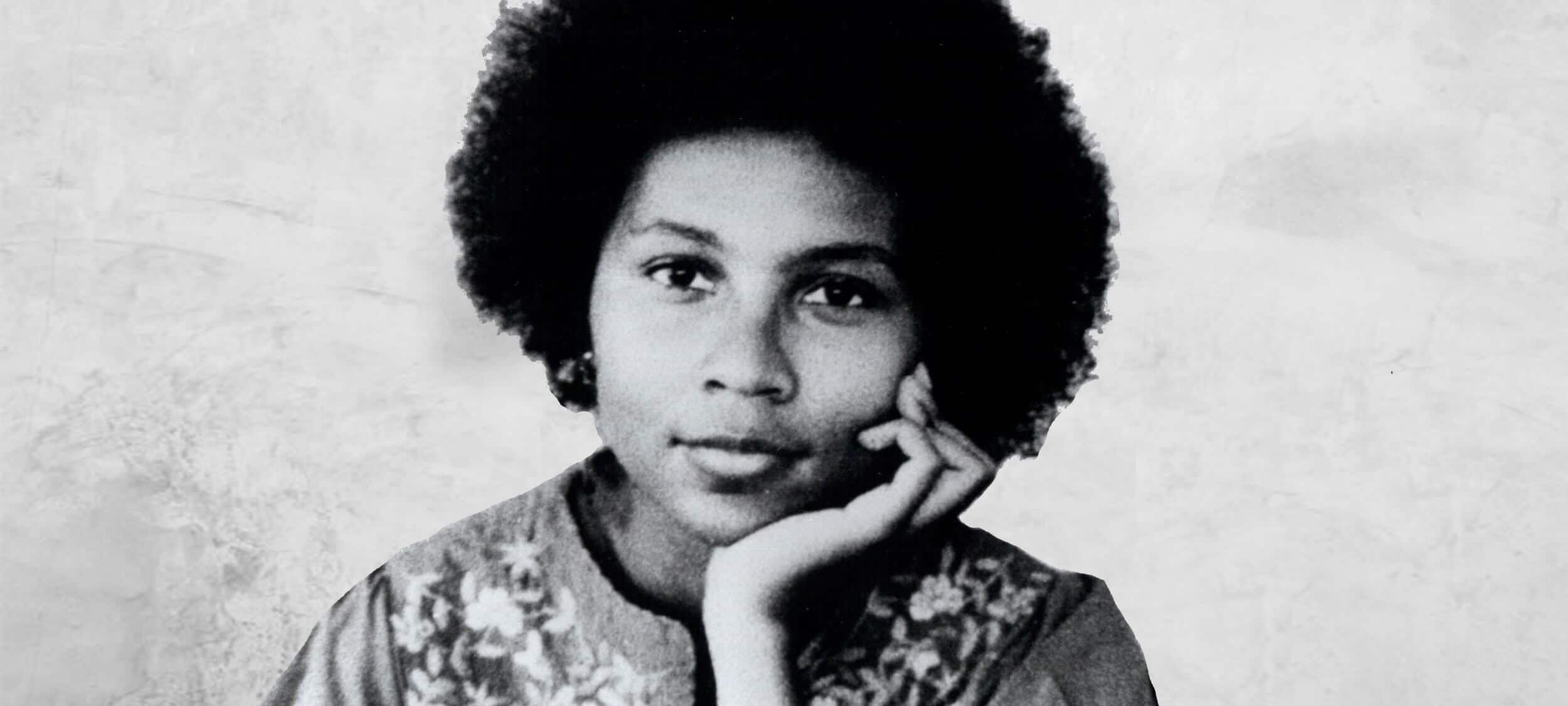

bell hooks

An outspoken professor, author, activist and cultural critic, bell hooks (1952 – 2021) work explores the connections between race, gender, and class. “Ain’t I A Woman” laid the groundwork for hooks progressive feminist theory, linking historical evidence of the sexism endured by black female slaves to its long-standing legacy on black women today. Born Gloria Watkins, hooks adopted her pen name after her late grandmother, wanting it written in lower case to shift the attention from her identity to her ideas. Now 38 years on from its original publication, her work remains radically relevant to the world today.

“A devaluation of black womanhood occurred as a result of the sexual exploitation of black women during slavery that has not altered in the course of hundreds of years.”

Simone De Beauvoir

Simone de Beauvoir (1908-1986) was a French author, feminist and existential philosopher. She lived an unconventional life as a working experiment of her ideas. As an existentialist, de Beauvoir believed in living authentically and argued that people must choose for themselves who they want to be and how they want to live. The more pressure society – and other people – place on you, the harder it is to make that authentic choice, particularly for women. In her best-known work, ‘The Second Sex’ she famously posed that women are not born, they are made. Meaning that there is no essential definition of womanhood, rather social norms work hard to force them into a notion of femininity

“Man is defined as a human being and woman as a female – whenever she behaves as a human being she is said to imitate the male.”

Shulamith Firestone

Shulamith Firestone (1945-2012) was a writer, artist, and feminist whose book, The Dialectic of Sex, argued the structure of the biological family was primarily to blame for the oppression of women. Firestone proposed that over the course of human history, society itself had come to mirror the structure of the biological family and was the source from which all other inequalities developed. With a radical and uncompromising vision, she advocated for the development of reproductive technologies that would free women from the responsibilities of childrearing, dismantle the hierarchy of family life and set the foundations for a truly egalitarian society.

“the end goal of feminist revolution must be… not just the elimination of male privilege, but of the sex distinction itself.”

Hannah Arendt

Johannah “Hannah” Arendt (1906 – 1975) was a German Jewish political philosopher who left life under the Nazi regime for nearby European countries before settling in the United States. Informed by the two world wars she lived through, her reflections on totalitarianism, evil, and labour have been influential for decades. Arendt’s most well-known idea is “the banality of evil”, explored in 1963 in a piece for The New Yorker that covered the trial of a Nazi bureaucrat, Adolf Eichmann. Following the election of Donald Trump, sales of Arendt’s book The Origins of Totalitarianism, already one of the most important works of the 20th century, increased by 1600%.

“The sad truth is that most evil is done by people who never make up their minds to be good or evil.”

Martha Nussbaum

Martha Nussbaum (1947-present) is one of the world’s most influential living moral philosophers, trailblazing in her philosophical advocacy for religious tolerance, feminism and the merits of emotions. Nussbaum believes the ethical life is about vulnerability and embracing uncertainty. She famously argued for the place of emotions within politics, saying democracy simply doesn’t work without love and compassion. In ‘Not for Profit: Why Democracy Needs the Humanities’ Nussbaum took on the education system, proposing that its role is not to produce an economically productive and useful citizen, but people who are imaginative, emotionally intelligent and compassionate.

“To be a good human being is to have a kind of openness to the world, an ability to trust uncertain things beyond your own control.”

Simone Weil

Simone Weil (1909–1943) was a Philosopher, Christian mystic and political activist in the French Resistance, who TS Eliot called a “genius akin to that of the saints”. Weil gave attention to working conditions and is known to have given up a life of privileged to work in factories. This experience shaped her writings, which consider the relationship between individual and state, the nature of knowledge, the spiritual shortcomings of industrialism and suffering as key to the human condition. In The Need for Roots, Weil argued that society suffered an ‘uprootedness’, a deep malaise in the human condition due to a lack of connectedness to past, land, community and spirituality.

“To be rooted is perhaps the most important and least recognized need of the human soul.”

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Big thinker

Relationships

Big Thinker: Joanna Bourke

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Free markets must beware creeping breakdown in legitimacy

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Science + Technology

The ethics of exploration: We cannot discover what we cannot see

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Online grief and the digital dead

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Big Thinker: Aristotle

It is hard to overstate the impact that Aristotle (384 BCE—322 BCE) has had on Western philosophy.

He, along with his teacher Plato, set the tone for over two millennia of philosophical enquiry, with much subsequent work either building on or refuting his ideas.

His influence on philosophy has been unparalleled for over two thousand years, in fields including logic, metaphysics, science, ethics and politics.

Aristotle was born in the 4th century BC in Thrace, in the north of Greece. At around 18 years of age he moved south to Athens, the capital of philosophical thought, to study under Plato at his famous Academy. He spent around two decades there, absorbing – but not always agreeing with – Plato and his disciples.

After Plato’s death, he departed Athens and landed a gig tutoring the teenage Alexander of Macedon – soon to be Alexander the Great. However, it appears Aristotle summarily failed to imbue the budding general with a taste for either philosophy or ethics.

After Alexander was appointed regent of Macedon at the age of 16, Aristotle returned to Athens, where he established the Lyceum, his own philosophical school where he taught and wrote on a startling array of topics.

His followers became known as peripatetics, after the Greek word for “walking”, due to the walkways that surrounded the school and Aristotle’s reputed tendency to give lectures on the move.

Ethics and Eudaimonia

One of the areas of lasting impact was Aristotle’s work on ethics and politics, which he considered to be intimately related subjects (much to the surprise of modern folk).

His ethical theory was based on the idea that each of us ultimately seeks a concept he called eudaimonia, often translated as “happiness” but better rendered as “flourishing” or “wellbeing.”

The basic idea is that every (non-frivolous) thing we do is directed towards achieving some end. For example, you might fetch an apple from the fruit bowl to sate your hunger. But it doesn’t stop there. You might sate your hunger to promote your health, and you might promote your health because it enables you to do other things that you want to do – and so on.

Aristotle argued that if you follow this chain of ends all the way down, you’ll eventually reach something that you do because it’s an ‘end in itself’, not because it leads to some other end. He argued that the enlightened individual would inevitably arrive at the single ultimate end or good: eudaimonia.

Aristotle’s ethical theory is more like a theory of enlightened prudence or ‘practical wisdom’, which he called phronesis, that helps guide people towards achieving eudaimonia.

This sets Aristotle’s ethics apart from many modern ethical theories, such as utilitarianism, in that he’s not calling for us to maximise happiness or eudaimonia for all people but only helping us to live a good life.

Compared to more modern ethical theories, he is also less focused on explicit issues of preventing harm or preventing injustice than on the cultivation of good people.

Whereas the primary question guiding many ethical theories is ‘what should we do?’, Aristotle’s main concern is ‘how should we live?’.

Virtues and Friendship

This doesn’t mean Aristotle disregarded how we ought to behave towards others. Indeed, he argued that the best way to achieve eudaimonia was to embody certain virtues, such as honesty, courage and charity, which encourage us to be good to other people.

Each of these virtues occupies a “golden mean” between two extremes, which were considered vices. So too little courage was cowardice, and too much was recklessness, but just enough would lead to decisions that would promote eudaimonia.

He also lent us a useful term, akrasia, which means a kind of weakness of will, whereby people do the wrong thing not due to embodying vices, but by some inability to resist temptation.

We have all likely experienced akrasia from time to time, such as when we devour that last cookie or lie to escape blame, which we know is not conducive to our health or ethical flourishing.

While Aristotle’s “virtue ethics” fell out of favour for many centuries, it has enjoyed a resurgence since the mid-20th century and has a growing following today.

Aristotle also argued that one of the benefits of being a virtuous person was the kinds of friendships you could form.

The second reason is because you think they’re fun to be around, such as when two people simply enjoy each other’s company or enjoy shared activities like watching sport or playing board games, but don’t have any deeper connection when those activities are absent.

It’s the third type of friendship that Aristotle thought was the highest, which is when you like someone because they are a good person.

This is a mutual recognition of virtuous character, and you have reciprocal good will, where you genuinely care for them – even love them – and want the best for them. Aristotle argued that by cultivating virtues, and seeking out other virtuous people, we could form the strongest and most nourishing friendships.

Interestingly, modern science has vindicated the idea that one of the most important factors in living a happy and fulfilled life is the number of genuine and deep relationships one has, particularly with friends whom they care for and who care for them in return.

Artistotle on Politics

Aristotle’s political theory concerned how to structure a society in such a way that it enabled all its citizens to achieve eudaimonia.

His ancient Greek predilections – as well as the influence of Plato, who believed society should be ruled by ‘Philosopher Kings’ – are visible in his contempt for democracy in favour of rule by an enlightened aristocracy or monarchy.

However, Aristotle disagreed with his mentor in one important respect: Aristotle favoured private property, which he said promoted personal responsibility and fostered a kind of meritocracy that treated great achievers as being more morally worthy than the ‘lazy’.

The breadth, sophistication and influence of Aristotle’s thinking is formidable, especially considering that we only have access to 31 of the 200+ treatises that he wrote during his lifetime.

Tragically, the rest were lost in antiquity. While much of Aristotle’s philosophy is contested today given developments in logic and science over the last few centuries, arguably many of these developments were built on or were inspired by his work.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Plato’s Cave

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

To live well, make peace with death

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Assisted dying: 5 things to think about

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture, Relationships

Whose fantasy is it? Diversity, The Little Mermaid and beyond

BY Dr Tim Dean

Dr Tim Dean is Philosopher in Residence at The Ethics Centre and author of How We Became Human: And Why We Need to Change.

Big Thinker: Michael Sandel

Big Thinker: Michael Sandel

Big thinkerPolitics + Human Rights

BY Dr Laura D’Olimpio The Ethics Centre 9 MAR 2020

Prominent contemporary American political philosopher, Michael J. Sandel’s (1953—present) work on justice, ethics, democracy and markets has connected with millions around the world.

His popular first year undergraduate course, Justice, became Harvard University’s first freely available course – online and televised.

Sandel’s Socratic approach connects moral and political theories and concepts to everyday life, helping to engage his audience in otherwise complex philosophical ideas.

He recognises, “there is a great hunger…to engage in serious reflection on big, ethical questions that matter politically, but also that matter personally.”

We all face ethical and political dilemmas, decisions and disagreements. These are not always easy to resolve and often bring us into conflict with others whose views differ from our own. Sandel is quite clear on the remedy, that “we need to rediscover the lost art of democratic argument” and this is precisely what he models and facilitates.

Who we are

Sandel is known for emphasising the social aspects of our identities. He says that we think of ourselves “as members of this family or community or nation or people, as bearers of this history, as sons or daughters of that revolution, as citizens of this republic”, which illustrates our attachment to others as well as our contextual social reality. In this way he offers a critique of Rawlsian liberalism.

Liberalism, and particularly the view espoused by John Rawls in his 1971 book A Theory of Justice, sees people as highly individualised, rational and focussed on defending their rights. On this view, the government’s role is to protect individual freedom and fairly obtain and distribute resources.

Rawls’ famous thought experiment of the ‘veil of ignorance’ asks us to imagine ourselves prior to knowing who we are going to be in the world. If we do not know whether we will be male or female, able-bodied or beautiful or the opposite, or which race, class, or religion we will belong to, we should be able to fairly decide on the best policies by which a society should operate. This is the best way, Rawls believed, to achieve justice.

Conversely, Sandel argues that humans cannot be neutral in this way. When figuring out what we should do, people bring their “moral and spiritual encumbrances, traditions, and convictions” with them to the negotiating table.

In this way, talk of rights can only be understood in relation to what people think of as good, valuable and important in their lives, which is connected to their social and material circumstances. Thus, the abstract thought experiment Rawls details simply won’t work.

Civic engagement

Against the view that we are always free to choose what and who we care about and which are our special obligations, Sandel points out that certain commitments, such as those to our family and our political community, bind and restrict us in certain ways.

Precisely because we cannot be disinterested or disconnected when it comes to matters of political decision making, Sandel emphasises the importance of finding ways to support and increase civic engagement – as evidenced in his TED talk, The lost art of democratic debate, watched by over 1.4 million people.

By having a positive and active national political community that works towards the good of all, we can make sense of justice for real people situated in real world contexts. In this respect, he believes dialogue and respectful disagreement are vital.

“If everyone feels they are heard, even if they don’t get their way, they will be less resentful than if we pretend we are going to decide policy in a way that is neutral.”

Market societies

Something that really concerns Sandel is how we, in developed countries, have gone from having a market economy to becoming market societies. What this means is that everything is up for sale. If market thinking and market values dominate, then other values – those of the good life, education, relationships, and creativity – are squeezed out.

If everything is valued first and foremost economically, then the difference between the haves and have-nots matters. If money buys you a better education, better health care, better legal representation, as well as more material possessions and business opportunities, the cycle of poverty becomes increasingly insurmountable.

The ‘luck’ of being born into wealth should not count more towards one’s success than hard work, natural talent or intelligence. Yet this is increasingly evident in today’s world and, in this way, inequality and affluence determine much more than they should. As a result, the notion of ‘merit’ is loaded.

Sandel claims we live in a meritocratic society, yet merit itself is a tyrannical construct:

“The notion that your fate is in your hands, that ‘you can make it if you try!’ is a double-edged sword. Inspiring in one way, but invidious in another. It congratulates the winners, but denigrates the losers, even in their own eyes”.

Instead, we need to be more inclusive and recognise that everyone has a role to play in our shared fate, regardless of who is wealthy or poor. In order to move forward together, “we need to find our way to a morally more robust discourse, one that takes seriously the corrosive effect of meritocratic striving on the social bonds that constitute our common life.”

Posing provocative questions such as: Should you pay a child to read a book? Should a prisoner pay to upgrade their accommodation? Can we place a monetary value on the Great Barrier Reef? Sandel compels us to consider what values should govern civic life, and how we might rethink the role of the market in a democratic society.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

Ethics Explainer: Freedom of Speech

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Society + Culture

On truth, controversy and the profession of journalism

Opinion + Analysis

Climate + Environment, Politics + Human Rights

Limiting immigration into Australia is doomed to fail

Big thinker

Politics + Human Rights

Big Thinker: Ayaan Hirsi Ali

BY Dr Laura D’Olimpio

Dr Laura D’Olimpio is senior lecturer in philosophy of education at the University of Birmingham, UK, and co-edits the Journal of Philosophy in Schools.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Big Thinker: Peter Singer

Peter Singer (1946—present), one of world’s most influential living philosophers, is best known for applying rigorous logic to a range of practical issues from animal rights, giving to charity to the ethics of abortion and infanticide.

Singer was born in Melbourne in 1946 to Austrian Jewish Holocaust survivors. As a teen he declared his atheism and refused to celebrate his Bar Mitzvah. After studying law, history and philosophy at Melbourne University, he won a scholarship to Oxford University, writing his thesis on civil disobedience. In 1996 he ran unsuccessfully for the Greens in the Victorian State Parliament, and he has held posts at Melbourne, Monash, New York, London and Princeton Universities. His impact on public debate and academic philosophy cannot be overstated.

A key aspect of Singer’s contributions is the idea of ‘equal consideration of interests’. This informs both his views towards animals and charity. It means that we should consider the interests of any sentient beings who have the capacity to suffer and feel pleasure and pain.

Singer is a consequentialist, which means he defines ethical actions as ones that maximise overall pleasure and reduce overall pain. Part of what makes him such a challenging and influential thinker is his application of utilitarianism to real-world problems to offer counter-intuitive yet compelling solutions.’

Are you speciesist?

While at Oxford, Singer recalls a conversation with a friend over lunch that was the “most formative experience of [his] life”. Singer had the meat spaghetti, whereas his friend opted for the salad. His friend was the “first ethical vegetarian” he’d met. Two weeks later, Singer became a vegetarian and several years later published his seminal work Animal Liberation (1975).

Singer’s argument for not eating meat is more-or-less the same as another utilitarian philosopher, Jeremy Bentham. Bentham wrote that “the question is not can they reason or can they talk, but can they suffer?” Similarly, Singer argues that animals have the capacity to suffer. Just as we rightly condemn torture, we should also condemn practices like factory farming that inflict unjustifiable pain on non-human animals. He coined the term ‘speciesism’ to describe the privileging of humans over other animals.

Giving to charity

In Singer’s essay “Famine, Affluence and Morality” (1972), he argues that people in rich countries have a moral obligation to give to charities that help people in poverty overseas. He uses an analogy of a drowning child: if we were walking past a shallow pond and saw a child drowning, we would wade in and save the child, even if this meant wrecking our favourite and most expensive pair of shoes. Likewise, because we know there are children dying overseas from preventable poverty-related diseases, we should be giving at least some of our income to charities that fight this.

Opponents to Singer argue that his view about giving to charity is psychologically untenable, and that there are differences between giving to charity and saving a drowning child. For example, the physical act of pulling a child out from water is more morally compelling than sending a cheque overseas. Other arguments include: we don’t know the child will definitely be saved when we send the cheque, fighting poverty requires a collective global effort not just an individual donation, and charities are ineffective and have high overhead costs.

Singer concedes that there may be psychological reasons why people would save the drowning child yet don’t give much to charity, but he says even if it seems strange, rationally there are no relevant moral differences between the cases.

Responding to the criticism that charities may not be effective has led Singer to be a proponent of ‘effective altruism’. In his book The Most Good You Can Do (2015) he describes how a number of charity evaluators can recommend the most cost-effective way to do good. Singer recommends giving on a progressive scale, depending on one’s income.

Instead of pursuing careers in academia, some of Singer’s brightest past students have decided to work for Wall Street to make as much money as possible to then give this away to effective charities.

Controversy around infanticide

Singer has faced sustained criticism and protest throughout his career for his views on the sanctity of life and disability – especially in Germany, where in the 90’s, his views were compared to Nazism and university courses that set his books were boycotted. While he has always been a staunch supporter of abortion on the grounds that a foetus lacks self-consciousness and the criteria of personhood, he argues there is no moral difference between abortion in the womb and killing a newborn. Furthermore, because a newborn cannot yet be classified as a person, if its parents do not want it to survive, or if it has an extreme disability meaning that keeping it alive would be very costly, there is potential justification in killing it.

Religious sanctity-of-life critics argue that Singer’s ethics ignore the fundamental sanctity of human life. Disability rights advocates argue that Singer’s views are ableist, explaining that the quality of life of a disabled person is less than that of a non-disabled person ignores the socially-constructed nature of disability – its harms and inconveniences are largely because the built environment is made for able-bodied people.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Politics + Human Rights

Disease in a Time of Uncertainty

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights, Science + Technology

Not too late: regaining control of your data

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

There’s more than lives at stake in managing this pandemic

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights

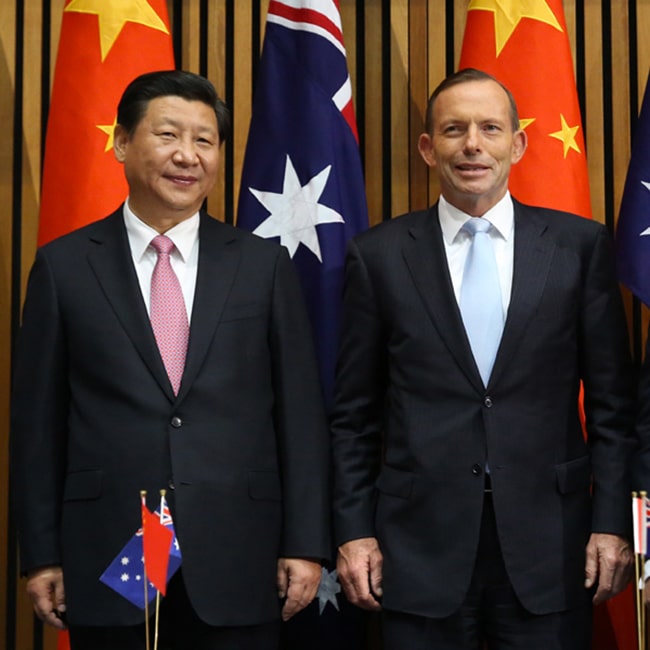

Character and conflict: should Tony Abbott be advising the UK on trade? We asked some ethicists

Join our newsletter