Big Thinker: Steven Pinker

Steven Pinker (1954-present) is an experimental psychologist who is “interested in all aspects of language, mind, and human nature.” In 2021, Academic Influence calculated that he was the second-most influential psychologist in the world in the decade 2010-2020.

Steven Pinker is a Canadian-American cognitive psychologist, psycholinguist, popular science author and public intellectual. He grew up in Montreal, earning his Bachelor’s degree in experimental psychology from McGill University and his PhD from Harvard University. He is currently the Johnstone Family Professor in the Department of Psychology at Harvard.

At the start of his graduate studies, Pinker found himself interested in language, and in particular, language development in children. In 1994, he went on to publish the first of his nine books written for a general audience, entitled The Language Instinct. In the book, Pinker introduces the reader to some of the fundamental parts of language, and argues that language itself is an instinct that makes humans unique.

Language, society and the mind

Try and have a thought without any language. It might be an idea or a memory that appears in your mind with no words or internal monologue. It’s quite difficult to switch off the voice in our heads for more than a few seconds. Pinker researches this connection between language and how our minds work.

To date, Pinker is the author of nine books written for a general audience. He covers a wide range of topics and questions that get at the heart of how we learn languages and what this does to our minds. His book The Stuff of Thought (2007) looks at how language shapes the way we think. He begins by suggesting that when we use language, we are doing two things:

- Conveying a message to someone

- Negotiating the social relationship between ourselves and whoever we are speaking to

For example, when a professor stands at the front of a lecture hall and tells her students “may I have your attention, class is about to begin” the professor is doing two things. First, she is alerting her students that class is starting (the message), and second, she is operating within the professor-student hierarchy (the social relationship) in which students should give their attention.

Taking this framework for language, Pinker works to untangle some of the complicated questions around language, such as “Why do so many swear words involve topics like sex, bodily functions or the divine?” and “Why do some children’s names thrive while others fall out of favour?”

Trends of today: is violence declining?

Pinker’s academic interests and research extends beyond language. In 2011, he published The Better Angels of Our Nature, which makes the claim that violence in human societies has generally decreased steadily over time.

“Historical data from past centuries are far less complete, but the existing estimates of death tolls, when calculated as a proportion of the world’s population at the time, show at least nine atrocities before the 20th century (that we know of) which may have been worse than World War II.”

Violence in this case does not just mean war. Pinker also looks at collapsing empires, the slave trade, the murder of native peoples, treatment of children and religious persecution as acts of violence in the world. While it feels like we see and hear about a lot of violence today, he notes that it’s often because these are ‘newsworthy’ events.

“In the case of violence, you never see a reporter with a microphone and a sound truck in front of a high school announcing that the school has not been shot up today, or in an African capital noting that a civil war has not erupted.”

After establishing the trend of declining violence, he looks at historical factors that work to explain why we live in a less violent world. Some of these trends include increasing respect for women, the rise in technological progress, and more application of knowledge and rationality to human affairs.

Current work

Steven Pinker’s work has received a number of prizes for his books, including the William James Book Prize three times, the Los Angeles Times Science Book Prize, the Eleanor Maccoby Book Prize, the Cundill Recognition of Excellence in History Award, and the Plain English International Award. He has also served as an editor and advisor for a variety of scientific, scholarly, media and humanist organisations.

Steven Pinker still spends his time researching a diverse array of topics in psychology, language, historical and recent trends in violence, and neurobiology. One specific area he is currently researching is the role of common knowledge (i.e., things that we know other people know without having to say what we know) in language and other social phenomena.

Steven Pinker presents Enlightenment or Dark Age? as part of Festival of Dangerous Ideas 2022. Tickets on sale now.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Negativity bias

Big thinker

Relationships

Big Thinker: Immanuel Kant

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

The #MeToo debate – recommended reads

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

Meet Joseph, our new Fellow exploring society through pop culture

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Big Thinker: Joanna Bourke

Joanna Bourke (1963 – present) is an historian, academic and philosopher who specialises in understanding the history of social and cultural phenomena. Her work has profoundly shaped our understanding of many fundamental aspects of human experience.

Joanna Bourke was born in New Zealand, and lived in Zambia, Solomon Island, and Haiti as a young child. She graduated from Auckland University with a Bachelor of Arts and a Master of Arts in history, and went on to complete her PhD at the Australian National University (ANU) in Canberra.

The dark parts of human experience

After writing her dissertation, titled Husbandry to Housewifery: Rural Women and Development in Ireland, 1890-1914 (1989), Bourke became interested in the experiences of men and women during wartime. Her work as a social and cultural historian has led her down a path of dealing with some of the less pleasant parts of being human, including topics such as pain, killing, war, violence, fear and rape. Bourke has been drawn to these elements of human experience because she feels that “these are the disciplines that have the most to offer us in terms of intellectual responses to current crises.”

Bourke’s book An Intimate History of Killing (1999) asks the question: what are the factors within society and in a war that turn a regular person into a good killer, or more politely, a good soldier? To answer her question, she uses excerpts from diaries, letters, memoirs and reports of Australian, British and American veterans of WWI, WWII and the Vietnam war. Bourke concludes that ordinary, gentle human beings can (and often do) become enthusiastic killers during a war because the structure of war encourages soldiers to feel pleasure from killing.

Some of her writing is also born out of personal experience. After a massive operation and a broken morphine drip, Bourke started thinking about pain and how difficult it is to describe in the English language. In her book The Story of Pain: From Prayer to Painkillers (2014), she concludes that “it is useful to think about pain in adverbial terms” because “it describes the way we experience something, not what is experienced.” As well as tracing the history of pain from the 1800s to present, she also details how factors such as race, class, gender and age have influenced the medical treatment of pain and often resulted in cruel abuse and neglect.

“Life’s too short for second editions.”

Joanna Bourke’s academic interests are vast. She has written 13 books and published over 100 articles, often tackling controversial and taboo topics.

In her recent book Loving Animals: On Beastiality, Zoophilia and Post Human Love (2020), Bourke argues that we should take a more nuanced approach to how we understand loving relationships between humans and non-human animals. When we take this more nuanced approach, Bourke finds that we are able to gain a clearer understanding of the nature of relationships, love and what we owe each other.

“I will be suggesting that animals are actors in society. This serves to challenge the anthropocentrism of history, human exceptionalism, and the idea that ‘culture’ is an entirely human preserve.”

Bourke begins by pointing out that “studies suggesting a link between bestiality and psychosis should be treated with caution due to sampling bias, because they were conducted on people already within the penal system, rather than a cross-section of the population.” She calls us to think about how we can so freely say that we love our pets, but turn a blind eye to slaughterhouses and factory farming. Bourke wants us to ask: what does it mean to love a non-human animal, and more broadly, what does it mean to love?

When we remove human exceptionalism from our understanding of human-animal relationships (which Bourke urges that we must), we can begin to think more about what we owe animals and how moral attitudes such as care, compassion, affection and pleasure are not unique to human beings.

Current work

Bourke is currently a professor of history at Birkbeck, University of London in England. She is also the Principal Investigator for a project called SHaME, or Sexual Harms and Medical Encounters. The project explores the medical and psychiatric aspects of sexual violence, with the aim of moving beyond the shame of sexual assault and address it as a global health crisis.

Her newest book Disgrace: Global Reflections on Sexual Violence, which has been partially motivated by her work with SHaME, will be available for purchase in Australia on August 15.

Joanna Bourke presents The Last Taboo as part of Festival of Dangerous Ideas 2022. Tickets on sale now.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Akrasia

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships, Science + Technology

Parent planning – we should be allowed to choose our children’s sex

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Ethical dilemma: how important is the truth?

WATCH

Relationships

What is ethics?

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Big Thinker: Matthew Liao

Matthew Liao (1972 – present) is a contemporary philosopher and bioethicist. Having published on a wide range of topics, including moral decision making, artificial intelligence, human rights, and personal identity, Liao is best known for his work on the topic of human engineering.

At New York University, Liao is an Affiliate Professor in the Department of Philosophy, Director of the Center for Bioethics, and holds the Arthur Zitrin Chair of Bioethics. He is also the creator of Ethics Etc, a blog dedicated to the discussion of contemporary ethical issues.

A Controversial Solution to Climate Change

As the climate crisis worsens, a growing number of scientists have started considering geo-engineering solutions, which involves large-scale manipulations of the environment to curb the effect of climate change. While many scientists believe that geo-engineering is our best option when it comes to addressing the climate crisis, these solutions do come with significant risks.

Liao, however, believes that there might be a better option: human engineering.

Human engineering involves biomedically modifying or enhancing human beings so they can more effectively mitigate climate change or adapt to it.

For example, reducing the consumption of animal products would have a significant impact on climate change since livestock farming is responsible for approximately 60% of global food production emissions. But many people lack either the motivation or the will power to stop eating meat and dairy products.

According to Liao, human engineering could help. By artificially inducing mild intolerance to animal products, “we could create an aversion to eating eco-unfriendly food.”

This could be achieved through “meat patches” (think nicotine patches but for animal products), worn on the arm whenever a person goes grocery shopping or out to dinner. With these patches, reducing our consumption of meat and dairy products would no longer be a matter of will power, but rather one of science.

Alternatively, Liao believes that human engineering could help us reduce the amount of food and other resources we consume overall. Since larger people typically consume more resources than smaller people, reducing the height and weight of human beings would also reduce their ecological footprint.

“Being small is environmentally friendly.”

According to Liao, this could be achieved several ways for example, using technology typically used to screen embryos for genetic abnormalities to instead screen for height, or using hormone treatment typically used to stunt the growth or excessively tall children to instead stunt the growth of children of average height.

Reception

When Liao presented these ideas at the 2013 Ted Conference in New York, many audience members found the notion of wearing meat patches and making future generations smaller to be amusing. However, not everyone found these ideas humorous.

In response to a journal article Liao co-authored on this topic, philosopher Greg Bognar wrote that the authors were doing themselves and their profession a disservice by not adequately considering the feasibility or real cost of human engineering.

Although making future generations smaller would reduce their ecological footprint, it would take a long time for the benefits of this reduction in average height and weight to accrue. In comparison, the cost of making future generations smaller would be borne now.

As Bognar argues, current generations would need to devote significant resources to this effort. For example, if future generations were going to be 15-20cm shorter than current generations, we would need to begin redesigning infrastructure. Homes, workplaces and vehicles would need to be smaller too.

Liao and his colleagues do, however, recognise that devoting time, money, and brain power to pursuing human engineering means that we will have fewer resources to devote to other solutions.

But they argue that “examining intuitively absurd or apparently drastic ideas can be an important learning experience, and that failing to do so could result in our missing out on opportunities to address important, often urgent issues.”

While current generations may resent having to bear the cost of making future generations more environmentally friendly, perhaps it is a cost that we must bear.

Liao says, “We are the cause of climate change. Perhaps we are also the solution to it.”

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Explainer

Science + Technology

Thought experiment: “Chinese room” argument

Opinion + Analysis

Science + Technology, Society + Culture

Where did the wonder go – and can AI help us find it?

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Science + Technology

People first: How to make our digital services work for us rather than against us

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights, Science + Technology

Not too late: regaining control of your data

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Big Thinker: Sally Haslanger

Sally Haslanger (1955-present) is one of the most influential feminist philosophers in contemporary philosophy. She is one of the pioneers of social philosophy and works to make the field of philosophy more inclusive.

She has some interesting life experiences, to say the least. Haslanger was born in 1955 in Connecticut, but moved to Los Angeles in 1963, where Jim Crow laws legalising racial segregation were still in effect. Moving from an unsegregated to a segregated part of the US as a child had an impact on her philosophical interests.

Her mother and grandmother were Christian Scientists, a small sect of Christianity that doesn’t believe in modern medicine, and she grew up attending their church. Later, her family moved to Texas where she attended an Episcopal boarding school, and started college before she had finished high school.

In a Q&A with the Massachusetts Institute of Technology ( MIT), Haslanger says that her interest in feminist philosophy was catalysed when she was sexually assaulted as an undergraduate student at Reed University. Afterwards, she became involved in feminist activism, especially during her time as a graduate student at University of California, Berkeley. Later in life, she and her husband adopted and raised two African-American children. Haslanger says that these life experiences have played an important role in directing her philosophical interests.

What is race? What is gender?

While these seem like straightforward questions, Haslanger has spent a large part of her academic career trying to answer them. Race and gender are categories that allow us to group people in particular ways, predominantly based on physical characteristics. However, she doesn’t believe that the categories of race and gender refer to just physical characteristics, they also refer to social positions. Social positions refer to where someone fits into their society: – they could be in a privileged position or a more marginalised one.

“On my view,” she said, “both race and gender are social positions that individuals occupy by virtue of their body being interpreted a certain way.”

In 2000, Haslanger published what is now one of her most well-known and controversial papers: Gender and Race: (What) are they? (What) do we want them to be? In her paper, one of the things she tried to do is find a characteristic that all women have or experience. The characteristic she finds and defends in her paper is systematic subordination. On Haslanger’s view, to be a woman is to occupy a lower position in society because of the way that her body is interpreted by others.

Her definition sparked controversy amongst transgender rights activists. Some people identify as women, but are not necessarily perceived by society as women. Haslanger’s definition of a woman excludes these people, – namely, trans women who have not yet transitioned.

Since the paper was published, Haslanger has taken on a lot of the criticism and worked to make her definition more inclusive. However, she still holds that gender and race refer to more than physical characteristics; they also refer to positions within society.

Advocacy and inclusivity

Haslanger feels strongly about promoting feminist causes outside of the field of philosophy. During the 2016 US presidential election, she wrote about some of the ways Hillary Clinton’s campaign was being undermined by sexism.

“As long as ‘being presidential’ and ‘looking presidential’ are about being and looking masculine, we will be unable to address what is ripping [the US] apart as a country.”

Within the field of philosophy, she is a strong advocate for inclusivity and making the field a more inviting space for women and people of colour. Now, as a philosophy professor at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), Haslanger predominantly teaches courses in social and political philosophy, feminist philosophy, philosophy of race, and history of philosophy.

To boost participation from traditionally underrepresented groups in philosophy, Haslanger worked to create a summer program alongside a few other philosophers in 2014. Philosophy in an Inclusive Key Summer Institute (PIKSI) creates a space for underrepresented undergraduate students to work in more formal areas of philosophy (such as logic and metaphysics) or in areas that may be seen as less important and rigorous (such as the philosophy of gender and race).

Haslanger is also the founder of the Women in Philosophy Task Force (WPHTF), which is a group of women who work to coordinate initiatives and intensify the efforts to advance women in philosophy.

“Philosophers spend a lot of time worrying about the mind: what is it? How does the mind relate to the body? They can hardly get a handle on the mind, so the social is completely out of reach. I’m a little impatient. I’m not going to wait until the mind is figured out to figure out the social world.” – MIT Q&A

Sally Haslanger has had a considerable impact on inclusivity in philosophy. Her work has encouraged philosophers and activists to investigate and question what we thought we could take to be truths about race and gender. Her work today continues to facilitate important discussions on how society functions and what we might be able to do to make it more equitable.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Office flings and firings

Big thinker

Relationships, Society + Culture

9 LGBTQIA+ big thinkers you should know about

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics explainer: Normativity

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Easter and the humility revolution

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Big Thinker: Tyson Yunkaporta

Tyson Yunkaporta is a researcher, arts critic, poet, and traditional wood carver. He works as a senior lecturer in Indigenous Knowledges and is the founder of the Indigenous Knowledge Systems Lab at Deakin University.

A scholar of free-ranging ideas

Yunkaporta is not your typical academic. In a recent interview, he said:

“I try to avoid naming anything. And I try to avoid making too much sense, and I try to say things a bit differently every time and to mix it up. And I’ll make points that you can’t put together. I do that quite deliberately because I don’t want the things I’m thinking or working on to become an ideology or a brand, or something that people can use as a name… you’ve got to avoid that packaging and repackaging of ideas and let these things be free-range.”

Yunkaporta tries to keep his writing and discussions “free-range” because he doesn’t want to give complex ideas or concepts an “artificial simplicity.”

According to Yunkaporta, when we simplify complex ideas, they can become easily distorted or manipulated and the original intention behind them can become lost. But more problematically, when we simplify complex ideas, we fail to see how they connect to the larger patterns of creation at work.

“There is a pattern to the universe and everything in it.”

Nothing is really created or destroyed, it merely moves and changes. When we start to pay attention to the way that things move and change, and take note of the patterns that they make, we gain a better understanding of the world around us.

This is important, Yunkaporta states, because “future survival of all life on this planet will be dependent on humans being able to perceive and be the custodians of the patterns of creation again.”

Indigenous thinking can save the world

Yunkaporta’s recent book Sand Talk: How Indigenous Thinking Can Save the World, is all about identifying and learning from the patterns of creation.

Sand Talk has sometimes been described as an exercise in “reverse-anthropology”, because rather than looking at Indigenous knowledge systems and practices from a Western perspective, Yunkaporta examines Western knowledge systems and practices from an Indigenous perspective.

He is careful about what knowledge he shares in the process, explaining that symbolic knowledge is often restricted (for example, by age or birth order) or is only appropriate for a specific places or groups (for example, members of particular clans).

However, he shares enough to help his readers start to recognise patterns in the world around them and to “come into Aboriginal ways of thinking and knowing, as a framework for the understandings needed in the co-creation of sustainable systems.”

Although Yunkaporta believes that sustainable systems cannot be manufactured by individuals (this is something that we must undertake collectively), he does think that each of us plays an important role as an agent of sustainability.

Agents of sustainability have four main protocols or guidelines, according to Yunkaporta: diversify, connect, interact, and adapt.

These guidelines tell us that we should diversify our interactions, so that we engage with people and systems that are dissimilar to ourselves and what we’re used to.

We should also aim to expand the networks of people that we currently engage with, so that we connect with as many new people and engage with as many new systems as we can.

Through these connections, we should also share knowledge, energy, and resources. But most importantly, we should allow ourselves to be transformed by the knowledge, energy and resources that are shared with us.

Ironically, Yunkaporta believes that frameworks are nothing more than “window dressing.” Yet, as he himself highlights, the four main protocols for sustainability agents are a kind of framework for sustainability.

This contradiction is, however, just part of Yunkaporta’s style. He describes his work as a “free-range ramble that should never be taken at face value.”

He writes to provoke thought and reflection in his audience, not to give them all the answers. After all, he muses, “perhaps the worst possible outcome of this work would be civilisation embracing these ideas.”

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Negativity bias

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

You don’t like your child’s fiancé. What do you do?

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

Meet Eleanor, our new philosopher in residence

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Truth & Honesty

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Big Thinker: Slavoj Žižek

Big Thinker: Slavoj Žižek

Big thinkerPolitics + Human RightsSociety + Culture

BY The Ethics Centre 16 MAR 2022

Slavoj Žižek (1949-present) is a contemporary leftist intellectual involved in academia as well as popular culture. He is known for his academic publishing in continental philosophy, psychoanalysis, critique of politics and arts, and Marxism.

Žižek is remarkable for combining an esoteric life of abstract academic enjoyment with political activism and engagement with current affairs and culture. His political life goes back to the 1980s when he campaigned for the democratisation of his home country, Slovenia (then part of Yugoslavia), and ran for the Slovenian presidency on the Liberal Democratic Party ticket in 1990. He has since become known as one of the world’s leading communist intellectuals, although he is far from dogmatic. Žižek has aroused controversy with his revisionary takes on Marxism, criticisms of political correctness and strategic support of Donald Trump in 2016.

Žižek is known as a provocateur, trigger-happy with an arsenal of dirty jokes, ethically challenging anecdotes, extreme statements, and stark inversions of glib platitudes. But his ‘intellectualism’ and provocations are neither nihilistic nor unprincipled.

Žižek’s oldest loves are cinema, opera and theory. He is sincerely committed to art and ideas, seeing them as both tools for sharpening up political struggle as well as part of what that struggle is ultimately all about. As he once put it: “we exist so that we can read Hegel.” That is, while philosophy may be useful, it’s also an end in itself, and needs no practical application to justify its existence or enjoyment.

As for his provocations, they are either the expression of a genuine, open-minded inquiry, or an effort to liberate us from the gravitational force of what he calls ‘ideology,’ a central target of his work.

Indeed, the revival of the Marxist notion and critique of ideology is one of Žižek’s most profound contributions to the contemporary conversation in this space and is a key part of his innovative synthesis of Lacanian and Marxist theory.

For Žižek, ideology is not primarily about our conscious political beliefs.

Instead, ideology is something that shapes our everyday behaviour, norms, habits of thought, architecture and art. It can be found everywhere from Starbucks coffee and toilet seat designs to Hollywood cinema. To engage with Žižek on ideology is therefore to engage with all aspects of life – culture, psychology, love, politics.

Inspired by Karl Marx, Žižek sees ideology as part of what supports a given social, economic and political system. It keeps us doing the things that keep the wheels of the system turning, regardless of what we consciously think. Žižek’s role, as he sees it, is to help bring this ideology to our attention so that we may break free of it. This liberation is essential to the ultimate goal for Žižek: replacing the liberal-capitalist order we currently occupy. To do this, Žižek strives to break the spell of ideology through a kind of psychoanalytic shock therapy that cannot be co-opted by ideological discourse.

“For Žižek, jokes are amusing stories that offer a shortcut to philosophical insight.” (Žižek’s Jokes)

When Žižek affirms Stalinism or prescribes gulags, for example, he isn’t being purely ironic nor purely sincere. His intention is instead to evade the clutches of superficial platitudes that narrow our thinking. In doing so, Žižek wants to “rehabilitate notions of discipline, collective order, subordination, sacrifice” – values that are too easily either neutralised by a bland and inoffensive liberalism that preserves the current social order or demonised via the “standard opposition of freedom and totalitarianism.”

Žižek’s analysis of ideology provides us with some of the tools we need to do this sort of ‘shock-therapy’ for ourselves. He explores the ways in which ideology manages to preserve the system we occupy through such mechanisms as cynicism, “inherent transgression” and the rhetoric of neutrality.

That is, cynicism allows us to knowingly act contradictory to our beliefs with little or no mental anguish.

In this way, the problem is not, as Marx put it in Capital: “They do not know it, but they are doing it.” Rather, it is, to use Žižek’s reformulation:

“They know it, but they are doing it anyway.”

Criticism of capitalism, for example, can thus live quite happily and indefinitely within its inner sanctum, as Hollywood films repeatedly demonstrate. (Here Žižek sometimes likes to cite the 2008 animated film Wall-E).

Žižek continues to be an unpredictable and idiosyncratic voice in politics and culture, difficult to place in partisan terms. Armed with the ferocious joy that he takes in theory and inversion – a joy that opposes all that is easy and superficial – he calls upon us to reflect seriously and radically upon ourselves and our society.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Health + Wellbeing, Society + Culture

Ethical concerns in sport: How to solve the crisis

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture

Infographic: Tear Down the Tech Giants

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

The limits of ethical protest on university campuses

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

Hey liberals, do you like this hegemony of ours? Then you’d better damn well act like it

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

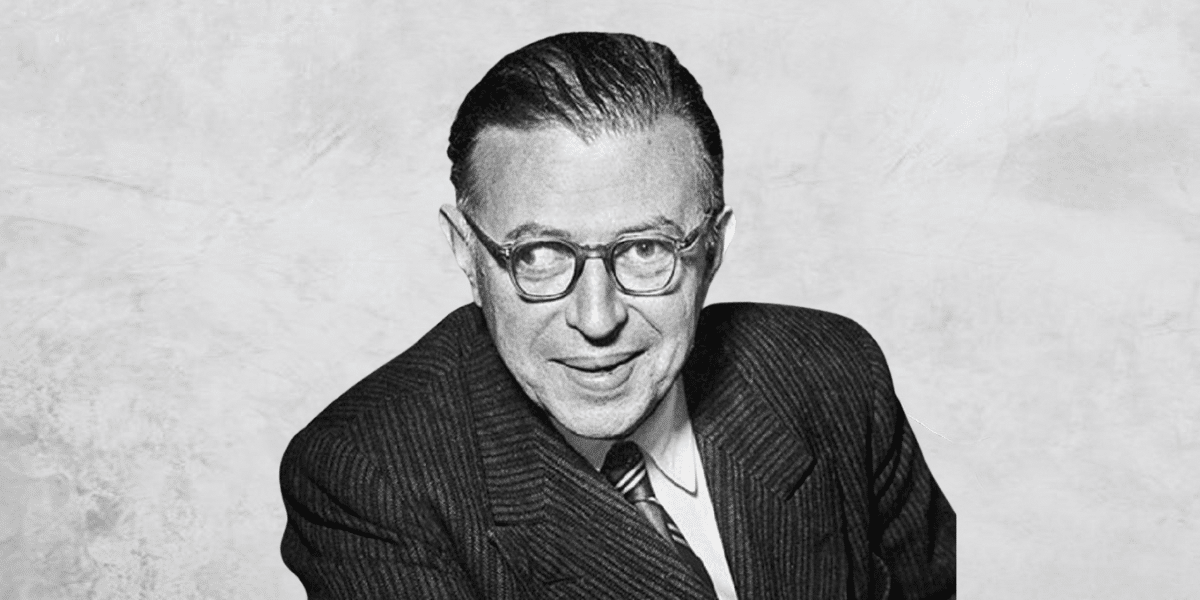

Big Thinker: Jean-Paul Sartre

Jean-Paul Sartre (1905–1980) is one of the best known philosophers of the 20th century, and one of few who became a household name. But he wasn’t only a philosopher – he was also a provocative novelist, playwright and political activist.

Sartre was born in Paris in 1905, and lived in France throughout his entire life. He was conscripted during the war, but was spared the front line due to his exotropia, a condition that caused his right eye to wander. Instead, he served as a meteorologist, but was captured by German forces as they invaded France in 1940. He spent several months in a prisoner of war camp, making the most of the time by writing, and then returned to occupied Paris, where he remained throughout the war.

Before, during and after the war, he and his lifelong partner, the philosopher and novelist Simone de Beauvoir, were frequent patrons of the coffee houses around Saint-Germain-des-Prés in Paris. There, they and other leading thinkers of the time, like Albert Camus and Maurice Merleau-Ponty, cemented the cliché of bohemian thinkers smoking cigarettes and debating the nature of existence, freedom and oppression.

Sartre started writing his most popular philosophical work, Being and Nothingness, while still in captivity during the war, and published it in 1943. In it, he elaborated on one of his core themes: phenomenology, the study of experience and consciousness.

Learning from experience

Many philosophers who came before Sartre were sceptical about our ability to get to the truth about reality. Philosophers from Plato through to René Descartes and Immanuel Kant believed that appearances were deceiving, and what we experience of the world might not truly reflect the world as it really is. For this reason, these thinkers tended to dismiss our experience as being unreliable, and thus fairly uninteresting.

But Sartre disagreed. He built on the work of the German phenomenologist Edmund Husserl to focus attention on experience itself. He argued that there was something “true” about our experience that is worthy of examination – something that tells us about how we interact with the world, how we find meaning and how we relate to other people.

The other branch of Sartre’s philosophy was existentialism, which looks at what it means to be beings that exist in the way we do. He said that we exist in two somewhat contradictory states at the same time.

First, we exist as objects in the world, just as any other object, like a tree or chair. He calls this our “facticity” – simply, the sum total of the facts about us.

The second way is as subjects. As conscious beings, we have the freedom and power to change what we are – to go beyond our facticity and become something else. He calls this our “transcendence,” as we’re capable of transcending our facticity.

However, these two states of being don’t sit easily with one another. It’s hard to think of ourselves as both objects and subjects at the same time, and when we do, it can be an unsettling experience. This experience creates a central scene in Sartre’s most famous novel, Nausea (1938).

Freedom and responsibility

But Sartre thought we could escape the nausea of existence. We do this by acknowledging our status as objects, but also embracing our freedom and working to transcend what we are by pursuing “projects.”

Sartre thought this was essential to making our lives meaningful because he believed there was no almighty creator that could tell us how we ought to live our lives. Rather, it’s up to us to decide how we should live, and who we should be.

“Man is nothing else but what he makes of himself.”

This does place a tremendous burden on us, though. Sartre famously admitted that we’re “condemned to be free.” He wrote that “man” was “condemned, because he did not create himself, yet is nevertheless at liberty, and from the moment that he is thrown into this world he is responsible for everything he does.”

This radical freedom also means we are responsible for our own behaviour, and ethics to Sartre amounted to behaving in a way that didn’t oppress the ability of others to express their freedom.

Later in life, Sartre became a vocal political activist, particularly railing against the structural forces that limited our freedom, such as capitalism, colonialism and racism. He embraced many of Marx’s ideas and promoted communism for a while, but eventually became disillusioned with communism and distanced himself from the movement.

He continued to reinforce the power and the freedom that we all have, particularly encouraging the oppressed to fight for their freedom.

By the end of his life in 1980, he was a household name not only for his insightful and witty novels and plays, but also for his existentialist phenomenology, which is not just an abstract philosophy, but a philosophy built for living.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Particularism

WATCH

Relationships

Unconscious bias

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Science + Technology

With great power comes great responsibility – but will tech companies accept it?

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

In defence of platonic romance

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Big Thinker: Kate Manne

Kate Manne (1983 – present) is an Australian philosopher who works at the intersection of feminist philosophy, metaethics, and moral psychology.

While Manne is an academic philosopher by training and practice, she is best known for her contributions to public philosophy. Her work draws upon the methodology of analytic philosophy to dissect the interrelated phenomena of misogyny and masculine entitlement.

What is misogyny?

Manne’s debut book Down Girl: The Logic of Misogyny (2018), develops and defends a robust definition of misogyny that will allow us to better analyse the prevalence of violence and discrimination against women in contemporary society. Contrary to popular belief, Manne argues that misogyny is not a “deep-seated psychological hatred” of women, most often exhibited by men. Instead, she conceives of misogyny in structural terms, arguing that it is the “law enforcement” branch of patriarchy (male-dominated society and government), which exists to police the behaviour of women and girls through gendered norms and expectations.

Manne distinguishes misogyny from sexism by suggesting that the latter is more concerned with justifying and naturalising patriarchy through the spread of ideas about the relationship between biology, gender and social roles.

While the two concepts are closely related, Manne believes that people are capable of being misogynistic without consciously holding sexist beliefs. This is because misogyny, much like racism, is systemic and capable of flourishing regardless of someone’s psychological beliefs.

One of the most distinctive features of Manne’s philosophical work is that she interweaves case studies from public and political life into her writing to powerfully motivate her theoretical claims.

For instance, in Down Girl, Manne offers up the example of Julia Gillard’s famous misogyny speech from October 2012 as evidence of the distinction between sexism and misogyny in Australian politics. She contends that Gillard’s characterisation of then Opposition Leader Tony Abbott’s behaviour toward her as both sexist and misogynistic is entirely apt. His comments about the suitability of women to politics and characterisation of female voters as immersed in housework display sexist values, while his endorsement of statements like “Ditch the witch” and “man’s bitch” are designed to shame and belittle Gillard in accordance with misogyny.

Himpathy and herasure

One of the key concepts coined by Kate Manne is “himpathy”. She defines himpathy as “the disproportionate or inappropriate sympathy extended to a male perpetrator over his similarly, or less privileged, female targets in cases of sexual assault, harassment, and other misogynistic behaviour.”

According to Manne, himpathy operates in concert with misogyny. While misogyny seeks to discredit the testimony of women in cases of gendered violence, himpathy shields the perpetrators of that misogynistic behaviour from harm to their reputation by positioning them as “good guys” who are the victims of “witch hunts”. Consequently, the traumatic experiences of those women and their motivations for seeking justice are unfairly scrutinised and often disbelieved. Manne terms the impact of this social phenomenon upon women, “herasure.”

Manne’s book Entitled: How Male Privilege Hurts Women (2020) illustrates the potency of himpathy by analysing the treatment of Brett Kavanaugh during the Senate Judiciary Committee’s investigation into allegations of sexual assault levelled against Kavanaugh by Professor Christine Blassey Ford. Manne points to the public’s praise of Kavanaugh as a brilliant jurist who was being unfairly defamed by a woman who sought to derail his appointment to the Supreme Court of the United States as an example of himpathy in action.

She also suggests that the public scrutiny of Ford’s testimony and the conservative media’s attack on her character functioned to diminish her credibility in the eyes of the law and erase her experiences. The Senate’s ultimate endorsement of Justice Kavanaugh’s appointment to the Supreme Court proved Manne’s thesis – that male entitlement to positions of power is a product of patriarchy and serves to further entrench misogyny.

Evidently, Kate Manne is a philosopher who doesn’t shy away from thorny social debates. Manne’s decision to enliven her philosophical work with empirical evidence allows her to reach a broader audience and to increase the accessibility of philosophy for the public. She represents a new generation of female philosophers – brave, bold, and unapologetically political.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

Violence and technology: a shared fate

WATCH

Relationships

Unconscious bias

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Science + Technology

With great power comes great responsibility – but will tech companies accept it?

Big thinker

Relationships, Society + Culture

Big Thinker: Socrates

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

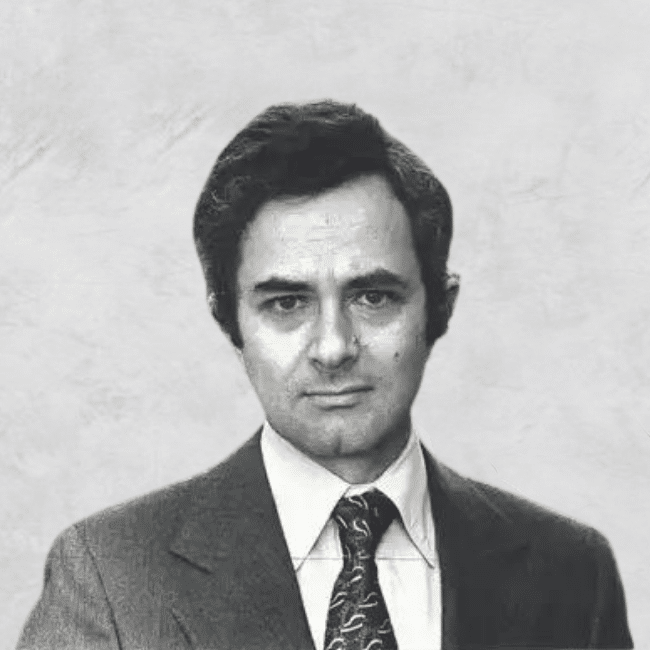

Big Thinker: Thomas Nagel

Thomas Nagel (1937-present) is an American philosopher whose work has spanned ethics, political philosophy, epistemology, metaphysics (the nature of what exists) and, most famously, philosophy of the mind.

An academic philosopher accessible to the general public, an atheist who doubts the materialist theory of evolution – Thomas Nagel is a considered nuanced professor with a rebellious streak.

Born in Belgrade Yugoslavia (present day Serbia) to German Jewish refugees, Nagel grew up in and around New York. Studying first at Cornell University, then the University of Oxford, he completed his PhD at Harvard University under John Rawls, one of the most influential and respected philosophers of the last century. Nagel has taught at New York University for the last four decades.

Subjectivity and Objectivity

A key theme throughout Nagel’s work has been the exploration of the tension between an individual’s subjective view, and how that view exists in an objective world, something he pursues alongside a persistent questioning of mainstream orthodox theories.

Nagel’s most famous work, What Is It Like to Be a Bat? (1974), explores the tension between subjective (personal, internal) and objective (neutral, external) viewpoints by considering human consciousness and arguing the subjective experience cannot be fully explained by the physical aspects of the brain:

“…every subjective phenomenon is essentially connected with a single point of view, and it seems inevitable that an objective, physical theory will abandon that point of view.”

Nagel’s The View From Nowhere (1986) offers both a robust defence and cutting critique of objectivity, in a book described by the Oxford philosopher Mark Kenny as an ideal starting point for the “intelligent novice [to get] an idea of the subject matter of philosophy”. Nagel takes aim at the objective views that assume everything in the universe is reducible to physical elements.

Nagel’s position in Mind and Cosmos (2012) is that non-physical elements, like consciousness, rationality and morality, are fundamental features of the universe and can’t be explained by physical matter. He argues that because (Materialist Neo-) Darwinian theory assumes everything arises from the physical, its theory of nature and life cannot be entirely correct.

The backlash to Mind and Cosmos from those aligned with the scientific establishment was fierce. However, H. Allen Orr, the American evolutionary geneticist, did acknowledge that it is not obvious how consciousness could have originated out of “mere objects” (though he too was largely critical of the book).

And though Nagel is best known for his work in the area of philosophy of the mind, and his exploration of subjective and objective viewpoints, he has made substantial contributions to other domains of philosophy.

Ethics

His first book, The Possibility of Altruism (1970), considered the possibility of objective moral judgments and he has since written on topics such as moral luck, moral dilemmas, war and inequality.

Nagel has analysed the philosophy of taxation, an area largely overlooked by philosophers. The Myth of Ownership (2002), co-written with the Australian philosopher Liam Murphy, questions the prevailing mainstream view that individuals have full property rights over their pre-tax income.

“There is no market without government and no government without taxes … [in] the absence of a legal system [there are] … none of the institutions that make possible the existence of almost all contemporary forms of income and wealth.”

Nagel has a Doctor of Laws (hons.) from Harvard University, has published in various law journals, and in 1987 co-founded with Ronald Dworkin (the famous legal scholar) New York University’s Colloquium in Legal, Political, and Social Philosophy, described as “the hottest thing in town” and “the centerpiece and poster child of the intellectual renaissance at NYU”. The colloquium is still running today.

Alongside his substantial contributions to academic philosophy, Nagel has written numerous book reviews, public interest articles and one of the best introductions to philosophy. In his book what does it all mean?: a very short introduction to philosophy (1987), Nagel leads the reader through various methods of answering fundamental questions like: Can we have free will? What is morality? What is the meaning of life?

The book is less a list of answers, and more an exploration of various approaches, along with the limitations of each. Nagel asks us not to take common ideas and theories for granted, but to critique and analyse them, and develop our own positions. This is an approach Thomas Nagel has taken throughout his career.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships

The future does not just happen. It is made. And we are its authors.

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Calling out for justice

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Want #MeToo to serve justice? Use it responsibly.

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Are there any powerful swear words left?

BY Joshua Pearl

Joshua Pearl is the head of Energy Transition at Iberdrola Australia. Josh has previously worked in government and political and corporate advisory. Josh studied economics and finance at the University of New South Wales and philosophy and economics at the London School of Economics.

Big Thinker: David Hume

There are few philosophers whose work has ranged over such vast territory as David Hume (1711—1776).

If you’ve ever felt underappreciated in your time, let the story of David Hume console you: despite being one of the most original and profound thinkers of his or any era, the Scottish philosopher never held an academic post. Indeed, he described his magnum opus, A Treatise of Human Nature, as falling “stillborn from the press.” When he was recognized at all during his lifetime, it was primarily as a historian – his multi-volume work on the history of the British monarchy was heralded in France, while in his native country, he was branded a heretic and a pariah for his atheistic views.

Yet, in the many years since his passing, Hume has been retroactively recognised as one the most important writers of the Early Modern era. His works, which touch on everything from ethics, religion, metaphysics, economics, politics and history, continue to inspire fierce debate and admiration in equal measure. It’s not hard to see why. The years haven’t cooled off the bracing inventiveness of Hume’s writing one bit – he is as frenetic, wide-ranging and profound as he ever was.

Empathy

The foundation of Hume’s ethical system is his emphasis on empathy, sometimes referred to as “fellow-feeling” in his writing. Hume believed that we are constantly being shaped and influenced by those around us, via both an imaginative, perspective-taking form of empathy – putting ourselves in other’s shoes – and a “mechanical” form of empathy, now called emotional contagion.

Ever walked into a room of laughing people and found yourself smiling, even though you don’t know what’s being laughed at? That’s emotional contagion, a means by which we unconsciously pick up on the emotional states of those around us.

Hume emphasised these forms of fellow-feeling as the means by which we navigate our surroundings and make ethical decisions. No individual is disconnected from the world – no one is able to move through life without the emotional states of their friends, lovers, family members and even strangers getting under their skin. So, when we act, it is rarely in a self-interested manner – we are too tied up with others to ever behave in a way that serves only ourselves.

The Nature of the Self

Hume is also known for his controversial views on the self. For Hume, there is no stable, internalised marker of identity – no unchanging “me”. When Hume tried to search inside himself for the steady and constant “David Hume” he had heard so much about, he found only sensations – the feeling of being too hot, of being hungry. The sense of self that others seemed so certain of seemed utterly artificial to him, a tool of mental processing that could just as easily be dispatched.

Hume was no fool – he knew that agents have “character traits” and often behave in dependable ways. We all have that funny friend who reliably cracks a joke, the morose friend who sees the worst in everything. But Hume didn’t think that these character traits were evidence of stable identities. He considered them more like trends, habits towards certain behaviours formed over the course of a lifetime.

Such a view had profound impacts on Hume’s ethics, and fell in line with his arguments concerning empathy. After all, if there is no self – if the line between you and I is much blurrier than either of us initially imagined – then what could be seen as selfish behaviours actually become selfless ones. Doing something for you also means doing something for me, and vice versa.

On Hume’s view, we are much less autonomous, sure, forever buffeted around by a world of agents whose emotional states we can’t help but catch, no sense of stable identity to fall back on. But we’re also closer to others; more tied up in a complex social web of relationships, changing every day.

Moral Motivation

Prior to Hume, the most common picture of moral motivation – one initially drawn by Plato – was of rationality as a carriage driver, whipping and controlling the horses of desire. According to this picture, we act after we decide what is logical, and our desires then fall into place – we think through our problems, rather than feeling through them.

Hume, by contrast, argued that the inverse was true. In his ethical system, it is desire that drives the carriage, and logic is its servant. We are only ever motivated by these irrational appetites, Hume tells us – we are victims of our wants, not of our mind at its most rational.

Reason is, and ought only to be the slave of the passions and can never pretend to any other office than to serve and obey them.

At the time, this was seen as a shocking inversion. But much of modern psychology bears Hume out. Consider the work of Sigmund Freud, who understood human behaviour as guided by a roiling and uncontrollable id. Or consider the situation where you know the “right” thing to do, but act in a way inconsistent with that rational belief – hating a successful friend and acting to sabotage them, even when on some level you understand that jealousy is ugly.

There are some who might find Hume’s ethics somewhat depressing. After all, it is not pleasant to imagine yourself as little more than a constantly changing series of emotions, many of which you catch from others – and often without even wanting to. But there is great beauty to be found in his ethical system too. Hume believed he lived in a world in which human beings are not isolated, but deeply bound up with each other, driven by their desires and acting in ways that profoundly affect even total strangers.

Given we are so often told our world is only growing more disconnected, belief in the possibility to shape those around you – and therefore the world – has a certain beauty all of its own.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Big thinker

Relationships

Big Thinker: Jelaluddin Rumi

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Ethics of Care

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Moral Relativism

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships