Big Thinker: Aristotle

It is hard to overstate the impact that Aristotle (384 BCE—322 BCE) has had on Western philosophy.

He, along with his teacher Plato, set the tone for over two millennia of philosophical enquiry, with much subsequent work either building on or refuting his ideas.

His influence on philosophy has been unparalleled for over two thousand years, in fields including logic, metaphysics, science, ethics and politics.

Aristotle was born in the 4th century BC in Thrace, in the north of Greece. At around 18 years of age he moved south to Athens, the capital of philosophical thought, to study under Plato at his famous Academy. He spent around two decades there, absorbing – but not always agreeing with – Plato and his disciples.

After Plato’s death, he departed Athens and landed a gig tutoring the teenage Alexander of Macedon – soon to be Alexander the Great. However, it appears Aristotle summarily failed to imbue the budding general with a taste for either philosophy or ethics.

After Alexander was appointed regent of Macedon at the age of 16, Aristotle returned to Athens, where he established the Lyceum, his own philosophical school where he taught and wrote on a startling array of topics.

His followers became known as peripatetics, after the Greek word for “walking”, due to the walkways that surrounded the school and Aristotle’s reputed tendency to give lectures on the move.

Ethics and Eudaimonia

One of the areas of lasting impact was Aristotle’s work on ethics and politics, which he considered to be intimately related subjects (much to the surprise of modern folk).

His ethical theory was based on the idea that each of us ultimately seeks a concept he called eudaimonia, often translated as “happiness” but better rendered as “flourishing” or “wellbeing.”

The basic idea is that every (non-frivolous) thing we do is directed towards achieving some end. For example, you might fetch an apple from the fruit bowl to sate your hunger. But it doesn’t stop there. You might sate your hunger to promote your health, and you might promote your health because it enables you to do other things that you want to do – and so on.

Aristotle argued that if you follow this chain of ends all the way down, you’ll eventually reach something that you do because it’s an ‘end in itself’, not because it leads to some other end. He argued that the enlightened individual would inevitably arrive at the single ultimate end or good: eudaimonia.

Aristotle’s ethical theory is more like a theory of enlightened prudence or ‘practical wisdom’, which he called phronesis, that helps guide people towards achieving eudaimonia.

This sets Aristotle’s ethics apart from many modern ethical theories, such as utilitarianism, in that he’s not calling for us to maximise happiness or eudaimonia for all people but only helping us to live a good life.

Compared to more modern ethical theories, he is also less focused on explicit issues of preventing harm or preventing injustice than on the cultivation of good people.

Whereas the primary question guiding many ethical theories is ‘what should we do?’, Aristotle’s main concern is ‘how should we live?’.

Virtues and Friendship

This doesn’t mean Aristotle disregarded how we ought to behave towards others. Indeed, he argued that the best way to achieve eudaimonia was to embody certain virtues, such as honesty, courage and charity, which encourage us to be good to other people.

Each of these virtues occupies a “golden mean” between two extremes, which were considered vices. So too little courage was cowardice, and too much was recklessness, but just enough would lead to decisions that would promote eudaimonia.

He also lent us a useful term, akrasia, which means a kind of weakness of will, whereby people do the wrong thing not due to embodying vices, but by some inability to resist temptation.

We have all likely experienced akrasia from time to time, such as when we devour that last cookie or lie to escape blame, which we know is not conducive to our health or ethical flourishing.

While Aristotle’s “virtue ethics” fell out of favour for many centuries, it has enjoyed a resurgence since the mid-20th century and has a growing following today.

Aristotle also argued that one of the benefits of being a virtuous person was the kinds of friendships you could form.

The second reason is because you think they’re fun to be around, such as when two people simply enjoy each other’s company or enjoy shared activities like watching sport or playing board games, but don’t have any deeper connection when those activities are absent.

It’s the third type of friendship that Aristotle thought was the highest, which is when you like someone because they are a good person.

This is a mutual recognition of virtuous character, and you have reciprocal good will, where you genuinely care for them – even love them – and want the best for them. Aristotle argued that by cultivating virtues, and seeking out other virtuous people, we could form the strongest and most nourishing friendships.

Interestingly, modern science has vindicated the idea that one of the most important factors in living a happy and fulfilled life is the number of genuine and deep relationships one has, particularly with friends whom they care for and who care for them in return.

Artistotle on Politics

Aristotle’s political theory concerned how to structure a society in such a way that it enabled all its citizens to achieve eudaimonia.

His ancient Greek predilections – as well as the influence of Plato, who believed society should be ruled by ‘Philosopher Kings’ – are visible in his contempt for democracy in favour of rule by an enlightened aristocracy or monarchy.

However, Aristotle disagreed with his mentor in one important respect: Aristotle favoured private property, which he said promoted personal responsibility and fostered a kind of meritocracy that treated great achievers as being more morally worthy than the ‘lazy’.

The breadth, sophistication and influence of Aristotle’s thinking is formidable, especially considering that we only have access to 31 of the 200+ treatises that he wrote during his lifetime.

Tragically, the rest were lost in antiquity. While much of Aristotle’s philosophy is contested today given developments in logic and science over the last few centuries, arguably many of these developments were built on or were inspired by his work.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Is existentialism due for a comeback?

Opinion + Analysis

Climate + Environment, Politics + Human Rights

Australia, it’s time to curb immigration

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Ethical judgement and moral intuition

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

James Hird In Conversation Q&A

BY Dr Tim Dean

Dr Tim Dean is Philosopher in Residence at The Ethics Centre and author of How We Became Human: And Why We Need to Change.

Big Thinker: Michael Sandel

Big Thinker: Michael Sandel

Big thinkerPolitics + Human Rights

BY Dr Laura D’Olimpio The Ethics Centre 9 MAR 2020

Prominent contemporary American political philosopher, Michael J. Sandel’s (1953—present) work on justice, ethics, democracy and markets has connected with millions around the world.

His popular first year undergraduate course, Justice, became Harvard University’s first freely available course – online and televised.

Sandel’s Socratic approach connects moral and political theories and concepts to everyday life, helping to engage his audience in otherwise complex philosophical ideas.

He recognises, “there is a great hunger…to engage in serious reflection on big, ethical questions that matter politically, but also that matter personally.”

We all face ethical and political dilemmas, decisions and disagreements. These are not always easy to resolve and often bring us into conflict with others whose views differ from our own. Sandel is quite clear on the remedy, that “we need to rediscover the lost art of democratic argument” and this is precisely what he models and facilitates.

Who we are

Sandel is known for emphasising the social aspects of our identities. He says that we think of ourselves “as members of this family or community or nation or people, as bearers of this history, as sons or daughters of that revolution, as citizens of this republic”, which illustrates our attachment to others as well as our contextual social reality. In this way he offers a critique of Rawlsian liberalism.

Liberalism, and particularly the view espoused by John Rawls in his 1971 book A Theory of Justice, sees people as highly individualised, rational and focussed on defending their rights. On this view, the government’s role is to protect individual freedom and fairly obtain and distribute resources.

Rawls’ famous thought experiment of the ‘veil of ignorance’ asks us to imagine ourselves prior to knowing who we are going to be in the world. If we do not know whether we will be male or female, able-bodied or beautiful or the opposite, or which race, class, or religion we will belong to, we should be able to fairly decide on the best policies by which a society should operate. This is the best way, Rawls believed, to achieve justice.

Conversely, Sandel argues that humans cannot be neutral in this way. When figuring out what we should do, people bring their “moral and spiritual encumbrances, traditions, and convictions” with them to the negotiating table.

In this way, talk of rights can only be understood in relation to what people think of as good, valuable and important in their lives, which is connected to their social and material circumstances. Thus, the abstract thought experiment Rawls details simply won’t work.

Civic engagement

Against the view that we are always free to choose what and who we care about and which are our special obligations, Sandel points out that certain commitments, such as those to our family and our political community, bind and restrict us in certain ways.

Precisely because we cannot be disinterested or disconnected when it comes to matters of political decision making, Sandel emphasises the importance of finding ways to support and increase civic engagement – as evidenced in his TED talk, The lost art of democratic debate, watched by over 1.4 million people.

By having a positive and active national political community that works towards the good of all, we can make sense of justice for real people situated in real world contexts. In this respect, he believes dialogue and respectful disagreement are vital.

“If everyone feels they are heard, even if they don’t get their way, they will be less resentful than if we pretend we are going to decide policy in a way that is neutral.”

Market societies

Something that really concerns Sandel is how we, in developed countries, have gone from having a market economy to becoming market societies. What this means is that everything is up for sale. If market thinking and market values dominate, then other values – those of the good life, education, relationships, and creativity – are squeezed out.

If everything is valued first and foremost economically, then the difference between the haves and have-nots matters. If money buys you a better education, better health care, better legal representation, as well as more material possessions and business opportunities, the cycle of poverty becomes increasingly insurmountable.

The ‘luck’ of being born into wealth should not count more towards one’s success than hard work, natural talent or intelligence. Yet this is increasingly evident in today’s world and, in this way, inequality and affluence determine much more than they should. As a result, the notion of ‘merit’ is loaded.

Sandel claims we live in a meritocratic society, yet merit itself is a tyrannical construct:

“The notion that your fate is in your hands, that ‘you can make it if you try!’ is a double-edged sword. Inspiring in one way, but invidious in another. It congratulates the winners, but denigrates the losers, even in their own eyes”.

Instead, we need to be more inclusive and recognise that everyone has a role to play in our shared fate, regardless of who is wealthy or poor. In order to move forward together, “we need to find our way to a morally more robust discourse, one that takes seriously the corrosive effect of meritocratic striving on the social bonds that constitute our common life.”

Posing provocative questions such as: Should you pay a child to read a book? Should a prisoner pay to upgrade their accommodation? Can we place a monetary value on the Great Barrier Reef? Sandel compels us to consider what values should govern civic life, and how we might rethink the role of the market in a democratic society.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

The erosion of public trust

Big thinker

Politics + Human Rights

Big Thinker: Thomas Hobbes

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture, Climate + Environment, Politics + Human Rights

Why you should change your habits for animals this year

Explainer

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Dignity

BY Dr Laura D’Olimpio

Dr Laura D’Olimpio is senior lecturer in philosophy of education at the University of Birmingham, UK, and co-edits the Journal of Philosophy in Schools.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Big Thinker: Peter Singer

Peter Singer (1946—present), one of world’s most influential living philosophers, is best known for applying rigorous logic to a range of practical issues from animal rights, giving to charity to the ethics of abortion and infanticide.

Singer was born in Melbourne in 1946 to Austrian Jewish Holocaust survivors. As a teen he declared his atheism and refused to celebrate his Bar Mitzvah. After studying law, history and philosophy at Melbourne University, he won a scholarship to Oxford University, writing his thesis on civil disobedience. In 1996 he ran unsuccessfully for the Greens in the Victorian State Parliament, and he has held posts at Melbourne, Monash, New York, London and Princeton Universities. His impact on public debate and academic philosophy cannot be overstated.

A key aspect of Singer’s contributions is the idea of ‘equal consideration of interests’. This informs both his views towards animals and charity. It means that we should consider the interests of any sentient beings who have the capacity to suffer and feel pleasure and pain.

Singer is a consequentialist, which means he defines ethical actions as ones that maximise overall pleasure and reduce overall pain. Part of what makes him such a challenging and influential thinker is his application of utilitarianism to real-world problems to offer counter-intuitive yet compelling solutions.’

Are you speciesist?

While at Oxford, Singer recalls a conversation with a friend over lunch that was the “most formative experience of [his] life”. Singer had the meat spaghetti, whereas his friend opted for the salad. His friend was the “first ethical vegetarian” he’d met. Two weeks later, Singer became a vegetarian and several years later published his seminal work Animal Liberation (1975).

Singer’s argument for not eating meat is more-or-less the same as another utilitarian philosopher, Jeremy Bentham. Bentham wrote that “the question is not can they reason or can they talk, but can they suffer?” Similarly, Singer argues that animals have the capacity to suffer. Just as we rightly condemn torture, we should also condemn practices like factory farming that inflict unjustifiable pain on non-human animals. He coined the term ‘speciesism’ to describe the privileging of humans over other animals.

Giving to charity

In Singer’s essay “Famine, Affluence and Morality” (1972), he argues that people in rich countries have a moral obligation to give to charities that help people in poverty overseas. He uses an analogy of a drowning child: if we were walking past a shallow pond and saw a child drowning, we would wade in and save the child, even if this meant wrecking our favourite and most expensive pair of shoes. Likewise, because we know there are children dying overseas from preventable poverty-related diseases, we should be giving at least some of our income to charities that fight this.

Opponents to Singer argue that his view about giving to charity is psychologically untenable, and that there are differences between giving to charity and saving a drowning child. For example, the physical act of pulling a child out from water is more morally compelling than sending a cheque overseas. Other arguments include: we don’t know the child will definitely be saved when we send the cheque, fighting poverty requires a collective global effort not just an individual donation, and charities are ineffective and have high overhead costs.

Singer concedes that there may be psychological reasons why people would save the drowning child yet don’t give much to charity, but he says even if it seems strange, rationally there are no relevant moral differences between the cases.

Responding to the criticism that charities may not be effective has led Singer to be a proponent of ‘effective altruism’. In his book The Most Good You Can Do (2015) he describes how a number of charity evaluators can recommend the most cost-effective way to do good. Singer recommends giving on a progressive scale, depending on one’s income.

Instead of pursuing careers in academia, some of Singer’s brightest past students have decided to work for Wall Street to make as much money as possible to then give this away to effective charities.

Controversy around infanticide

Singer has faced sustained criticism and protest throughout his career for his views on the sanctity of life and disability – especially in Germany, where in the 90’s, his views were compared to Nazism and university courses that set his books were boycotted. While he has always been a staunch supporter of abortion on the grounds that a foetus lacks self-consciousness and the criteria of personhood, he argues there is no moral difference between abortion in the womb and killing a newborn. Furthermore, because a newborn cannot yet be classified as a person, if its parents do not want it to survive, or if it has an extreme disability meaning that keeping it alive would be very costly, there is potential justification in killing it.

Religious sanctity-of-life critics argue that Singer’s ethics ignore the fundamental sanctity of human life. Disability rights advocates argue that Singer’s views are ableist, explaining that the quality of life of a disabled person is less than that of a non-disabled person ignores the socially-constructed nature of disability – its harms and inconveniences are largely because the built environment is made for able-bodied people.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

What’s the use in trying?

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights, Science + Technology

Not too late: regaining control of your data

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights

Vaccination guidelines for businesses

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights

Australia’s fiscal debt will cost Gen Z’s future

Join our newsletter

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Big Thinker: John Locke

English Philosopher John Locke (1632—1704) is behind many of the ideas we now take for granted in a liberal democracy. Amongst them, his defence of life and liberty as natural and fundamental human rights.

He was especially known for his liberal, anti-authoritarian theory of the state, his empirical theory of knowledge and his advocacy of religious toleration. Much of Locke’s work is characterised by an opposition to authoritarianism, both at the level of the individual and within institutions such as the government and church.

Born in 1632, in his time he gained fame arguing that the divine right of kings is not supported by scripture. Instead, he defended a limited government whose duty is to protect the rights and liberty of its citizens. This idea is familiar to us now, yet at the time it was revolutionary, arguing against the monarchy as the source of society’s governance. A familiar idea in modern day, at the time it was revolutionary – an argument to depart from the monarchy as the source of society’s governance.

In defending his stance, Locke appealed to the notion of natural rights. He invited us to imagine an initial ‘state of nature’ with no government, police or private property. Locke argued that humans could discover, through careful reasoning, that there are natural laws which suggest that we have natural rights to our own persons and to our own labour.

Eventually we could reason that we should create a social contract with others. Out of this contract would emerge our political obligations and the institution of private property. In Locke’s version of the social contract, a human “divests himself of his natural liberty, and puts on the bonds of civil society…agreeing with other men to join and unite into a community” and by submitting to majority rule form a government designed to protect their rights.

The limits of power

Locke’s argument also places limits on the proper use of power by government authorities. While civil society, as viewed through Locke’s liberalism, sees that the individual must sacrifice – or at least compromise – his/her freedom in the name of the public good, the public good ought not to interfere with the individual’s freedom.

Due to this emphasis on liberty, Locke defended a distinction between a public and a private realm. The public realm is that of politics and the individual’s role in the community as a part of the state, which may include, for example, voting or fighting for one’s country. The private realm is that of domesticity where power is parental (traditionally, ‘paternal’).

For Locke, government should not interfere in the private realm. He held the argument that citizens were entitled to protest or revolt or disband a government when it failed to protect their collective interests. On this view it is crucial we distinguish the legitimate from the illegitimate functions of institutions.

Locke asked us to use reason in order to seek the truth, rather than simply accept the opinion of those in positions of power or be swayed by superstition. In this way, we see Locke as an Enlightenment thinker –our natural reason a light that shines, guiding our understanding in order to reveal knowledge.

Knowledge and personal identity

As an empiricist, Locke believed we gain our knowledge through experiences in the world. In contrast to the views of his rationalist predecessor Descartes, Locke argued that we are born as a blank slate or a tabula rasa. This means that at birth our mind has no innate ideas – it is blank. As our mind develops, sensations give rise to simple ideas, from which we form those more complex.

This theory of learning gives rise to another radical idea for his time. Locke asserted that in order to help children avoid developing bad thinking habits, they should be trained to base their beliefs on sound evidence. The strength of our belief should correlate to how strong or weak the evidence for it happens to be.

Furthermore, for Locke, our consciousness is what makes us ‘us’, constituting our personal identity.

Locke’s legacy

We see Locke’s legacy in the 1776 US Declaration of Independence, which was founded on his natural rights theory of government and proclaimed ‘we hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness’.

Following on from his theory of human rights, we also see Locke’s legacy in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, which was adopted by the United Nations General Assembly on 10 December 1948. Philosophers debate as to whether such rights are indeed ‘natural’, or whether they have been ‘constructed’ and agreed upon by society as useful rules to adopt and enforce.

Locke’s lasting legacy is the argument that society ought to be ruled democratically in such a way as to protect the liberty and rights of its citizens. And that the government should never over-step its boundaries and must always remember it is a glorified secretary of the people.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Reports

Politics + Human Rights

Ethical by Design: Evaluating Outcomes

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

Australia Day and #changethedate – a tale of two truths

Opinion + Analysis

Climate + Environment, Politics + Human Rights

Australia, it’s time to curb immigration

Big thinker

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

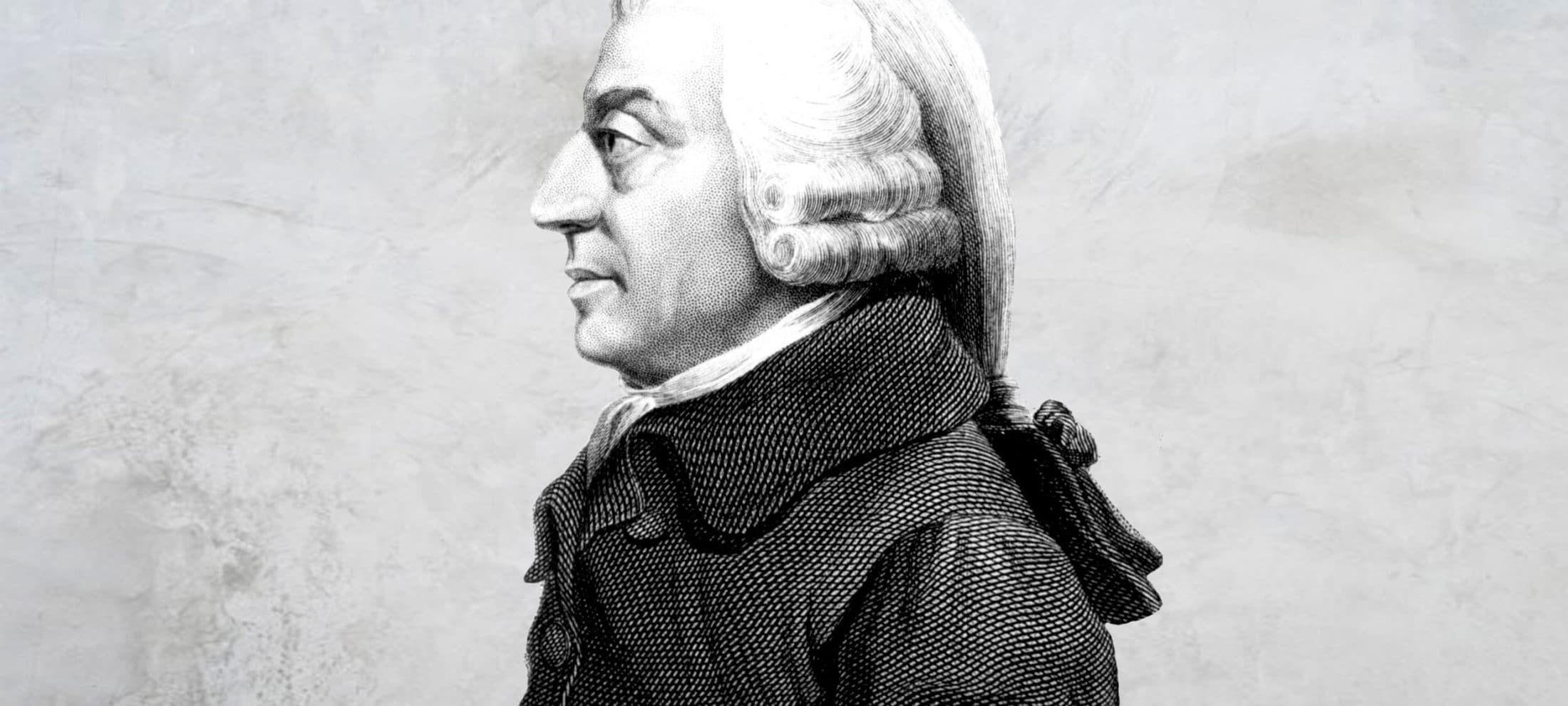

Big Thinker: Adam Smith

Join our newsletter

BY Dr Laura D’Olimpio

Dr Laura D’Olimpio is senior lecturer in philosophy of education at the University of Birmingham, UK, and co-edits the Journal of Philosophy in Schools.

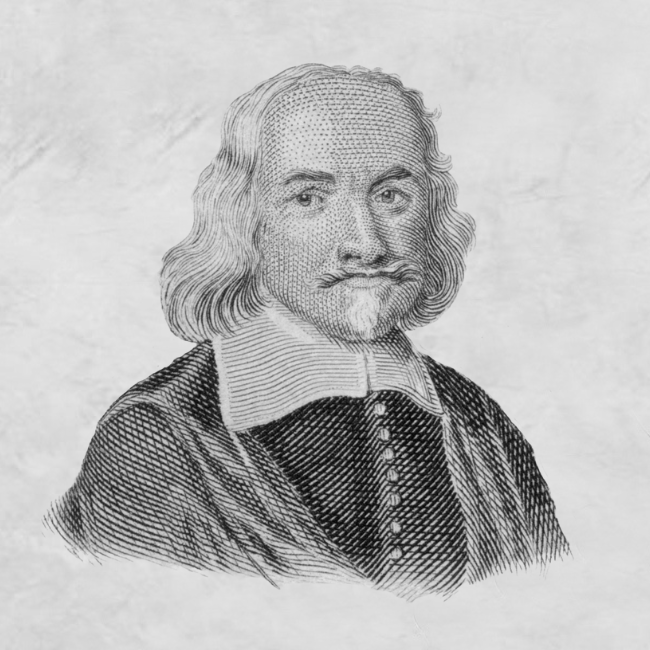

Big Thinker: Jeremy Bentham

The consequences of our actions are important and we should weigh these up when we consider what we should do.

Some philosophers have taken this idea even further, claiming that outcomes are the only criteria by which the moral worth of an action should be judged.

Jeremy Bentham (1748—1832) was the father of utilitarianism, a moral theory that argues that actions should be judged right or wrong to the extent they increase or decrease human well-being or ‘utility’.

He advocated that if the consequences of an action are good, then the act is moral and if the consequences are bad, the act is immoral.

Central to his argument was a belief that it is human nature to desire that which is pleasurable, and to avoid that which is painful. As a self-proclaimed atheist, he wanted to place morality on a firm, secular foundation. At the beginning of his Introduction to the Principles of Morals and Legislation, Bentham wrote:

“Nature has placed mankind under the governance of two sovereign masters, pain and pleasure. It is for them alone to point out what we ought to do, as well as to determine what we shall do.”

It is because of this emphasis on pleasure that his theory is known as hedonic utilitarianism. But this doesn’t mean we can do whatever we like. Importantly, for Bentham, it is not just one’s own happiness or pleasure that matters.

He notes, “Ethics at large may be defined, the art of directing men’s actions to the production of the greatest possible quantity of happiness.” The moral agent will perform the action that maximises happiness or pleasure for everyone involved.

Can we measure happiness?

Bentham defended an objective form of morality that could be measured in a scientific way. As an empiricist, he came up with a way to ‘weigh’ or quantify pleasures and pains as the consequences of an action.

He called this set of metaphorical scales the ‘hedonic’ or ‘felicific calculus’, allowing a rational moral agent to think through, and then act on, the right – moral– thing to do.

The ‘hedonic calculus’ is used to measure how much pain or pleasure an action will cause. It takes into consideration how near or far away the consequence will be, how intense it will be and how long it will last, if it will lead on to further pleasures or pains, and how certain we are that this consequence will result from the action under consideration.

The moral decision maker is meant to act as an ‘impartial observer’ or ‘disinterested bystander’, to be as objective as they can be and choose the action that will produce the greatest amount of good.

Do the ends justify the means?

There are some practical applications of utilitarianism. For instance, if you’re a politician in charge of making decisions that effects a large group of people, you should act in a way that maximises happiness and minimises pain and suffering. In this way, the hedonic calculus supports a welfare system that reduces unfair outcomes by redistributing wealth and resources.

Yet there are tricky aspects to the theory that must also be considered. Contemplate the saying “the ends justify the means” – what immoral action may be justified by (predicted) good consequences?

This is where ethicists start to ask tricky questions like, ‘would you kill Hitler?’. And if you answer ‘um, sure, because that will prevent a LOT of deaths’, then they will ask, ‘would you kill baby Hitler?’. You can see how it starts to get complicated.

Bentham’s theory relies on accurately predicting outcomes, and as such holds the moral agent accountable for moral luck. One might intend to do a good deed, but if an unpredictable result occurs, leading to a negative outcome, then they are still to be held morally responsible.

Visit Bentham in London

His theories were popular at University College London (UCL), where Behtham’s followers called themselves ‘Benthamites’. Among these were James Mill and his son, John Stuart Mill. J. S. Mill (1806 –1873) worried that Bentham’s theory was too hedonistic as it did not prioritise the ‘higher’ pleasures of the intellect. He added the criteria of ‘quality’ to Bentham’s calculus in order to create ‘higher’ and ‘lower’ quality pleasures.

A final, fun fact: Bentham willed his body to be preserved and displayed at UCL after his death. A visit to the philosophy department will see him in a busy hallway, merrily seated in a glass fronted mahogany case.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Big thinker

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Big Thinker: Adam Smith

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

From capitalism to communism, explained

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Authenticity

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Do Australia’s adoption policies act in the best interests of children?

BY Dr Laura D’Olimpio

Dr Laura D’Olimpio is senior lecturer in philosophy of education at the University of Birmingham, UK, and co-edits the Journal of Philosophy in Schools.

Big Thinkers: Laozi and Zhuangzi

Daoism is one of the three pillars of Chinese philosophy, and its founders Laozi and Zhuangzi implore us to unshackle ourselves from the constraints of the way we think and live a spontaneous, authentic life.

When many of us think of “philosophy”, we conjure images of toga-wearing Greeks debating in the agora in Athens. Or Renaissance thinkers like René Descartes contemplating consciousness in his armchair. Or perhaps Simone de Beauvoir and Jean-Paul Sartre smoking Gauloises in the cafés of post-war Paris.

But there is another tradition of philosophy that comes out of China that is just as deep and diverse, with just as long a history. It has considered many of the same questions as Western philosophy, such as the nature of reality, the possibility of knowledge and how to live a good life, but has sought to answer these questions in very different ways to many Western thinkers.

There are generally considered to be three pillars to Chinese philosophy: Confucianism, Daoism and Buddhism. All three have mixed and intermingled over centuries to deeply influence Chinese culture and thinking to this day.

Daoist spontaneity and playfulness

In many ways, Daoism was a reaction against Confucianist thinking, which has strict rules on how we are supposed to live our lives, on the social roles and responsibilities we are supposed to take on, and has a strong emphasis on order and ritual. Daoism was a total rejection of these things, and is much more about living spontaneously, intuitively and experiencing a direct connection with nature and existence.

Daoism has two great masters, Laozi, who wrote the Daodejing, and Zhuangzi, who wrote the eponymous Zhuangzi. Both of these thinkers are believed to have lived between the 6th and 4th centuries BCE, but while there are many stories about their lives, it’s difficult to separate fact from legend.

Both the Daodejing and the Zhuangzi are very playful texts, quite unlike most Western philosophy. Instead of outlining abstract theories supported by dry logical arguments, both were written in the form of sayings or stories that are often irreverent or absurd. They encourage the reader to reflect on life in a creative rather than analytic way.

For example, there’s a passage where Zhuangzi wakes up after dreaming he was a butterfly. But then he can’t be certain that he’s not right now a butterfly dreaming he’s a man. A similar sentiment was expressed by René Descartes, although far less poetically.

The three daos

The term “dao” itself is often translated to mean “way” or “path,” but it’s not an easy concept to pin down, which is by design. In a sense, the dao is like the natural order of the world, and following the dao is to be living in accordance with nature.

There are typically considered to be three daos:

- The human dao: the world of words, judgements and society

- The natural dao: the natural processes and regularities of the world, like the laws of nature

- The grand dao: the sum total of all things in the universe

These have a complex relationship, and Laozi wanted to make sure we don’t make the mistake of thinking the human dao is the only dao there is. For while we automatically use words and concepts to carve the world up into discrete things, nature itself is continuous. And while we can be judgemental, nature itself is free from judgement.

A central tenet of Daoism is embracing these opposite and contradictory states simultaneously. We can see some if this reflected in the yin/yang symbol, taijitu. It is at once a unitary thing, but it’s also composed of two opposites: the yin and the yang. This can be interpreted as representing the divisions that emerge within human thought – the separation of the one natural world into light/dark, hard/soft, active/passive, good/bad – but also shows how these things are complementary and all part of a greater whole.

There are even some Western thinkers who have wholeheartedly embraced this notion of complementarity. Notably, the Danish quantum physicist Niels Bohr argued that the seemingly contradictory quantum and classical accounts of reality weren’t in opposition but were complementary. He even chose the taijitu symbol for his coat of arms when he was knighted by the King of Denmark.

Many of the lines in the Daodejing and Zhuangzi challenge us to unshackle ourselves from the human dao and to contemplate the natural and the grand dao, and to realise that they’re all really one and the same.

For example, one translation of the opening line of the Daodejing is “the dao that can be spoken is not the true dao.” (In Chinese, it’s even more obtuse, being: “the dao that you can dao is not the true dao”.) If that’s so, then why speak or write this at all? And yet this realisation could only have come from writing this in the first place. Thus does a core paradox of daoism enter our minds to do its noble work.

Just be

Daoism teaches us to practice emptiness and non-action, which sits in stark contrast to many philosophical traditions that teach us to fill our minds with knowledge and to act with intent. Daoism tells us that things in the world just are, we are also in the world and just are, but we have this irritating habit of forgetting to just be and instead think and reflect on what we are, and then are guided by what we think we are instead of just being what we really are. It’s that simple.

“Therefore the sage dwells in the midst of non-action and practices the wordless teaching” – Laozi

Laozi and Zhuangzi are often cheeky, irreverent, playful and inscrutable. In a way, they are urging us to encounter nature directly, not mediated by words, and definitely not by rituals and rigid social roles.

This is not an easy thing to do, which is why the text encourages – or nags – us to snap us out of our complacent reliance on abstract concepts rather than experience concrete reality.

Dr Tim Dean is a philosopher, writer, honorary associate with the University of Sydney, editor of the Universal Commons, and faculty with The School of Life.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Conservatism

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships, Science + Technology

Parent planning – we shouldn’t be allowed to choose our children’s sex

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Akrasia

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Paralympian pay vs. Olympian pay

BY Dr Tim Dean

Dr Tim Dean is Philosopher in Residence at The Ethics Centre and author of How We Became Human: And Why We Need to Change.

Big Thinker: Buddha

Gautama Buddha lived during the 5th century BCE and was the founder of the Buddhist religion. He also developed a rich philosophical system of thought that challenged notions of permanence and personal identity.

Buddhism is typically considered a religion but it also has a strong philosophical foundation and has inspired a rich tradition of philosophical inquiry, especially in India and China, and, increasingly, Western countries.

Buddhism emerged from the teachings of Siddhartha Gautama, an Indian prince who turned his back on a life of leisure and opulence. Instead, he sought to understand the causes of suffering and how we might be able to be liberated from it.

Coincidentally, Gautama Buddha lived around the 5th Century BCE, which is at a similar time to two other great philosophers in different corners of the world – Socrates in Ancient Greece and Confucius in China – both of whom sparked their own major philosophical traditions.

Desire, happiness and suffering

Like many philosophers – from Aristotle to Peter Singer – one might say the Buddha was interested in how to live a good life. The starting point of his teachings is that life is suffering, which sounds like a pessimistic start, but he was just reminding us none of us can escape things like illness, death, loss, or these days, doing our tax returns.

Buddha went on to explain suffering is not random or uncaused. In fact, he argued if we can come to understand the causes of suffering, then we can do something about it. We can even become liberated from suffering and achieve nirvana, which is a state of pure enlightenment.

Many philosophers believe this teaching is just as relevant today as it was over 2,000 years ago. We’re told today that we ought to be happy, and that happiness comes from being able to satisfy our desires. Our entire economy is predicated on this idea. So we work hard, earn money, get stressed, buy more stuff, yet many of us can’t seem to find deeper satisfaction.

It turns out that no matter what desires we satisfy, there are more desires that crop up to take their place. And there are some desires that never go away, like the desire for status or wealth, and some desires that can never be satisfied, like when we experience unrequited love. And when we can’t satisfy our desires, we experience suffering.

The Buddha said this is because we have our theory of happiness backwards. Happiness doesn’t come from satisfying ever more desires – it comes from reducing our desires so there are fewer that need to be satisfied. It’s only when we desire nothing and we can just be that we are truly free from suffering.

Thus the Buddha argues our suffering is not caused by the whims of an indifferent world outside of our control. Rather, the cause of suffering is within our own minds. If we can change our minds, we can find liberation from suffering. This led him to develop a theory of our minds and how we perceive reality.

Permanence

He said that one of the fundamental mistakes in the way we think about the world is to believe in the permanence of things. We assume (or desire) that things will last forever, whether that be our youth, our possessions or our relationships with loved ones, and we become attached to them.

So when they inevitably erode, decay or disappear – we grow old, our possessions wear out, our loved ones move on – we suffer. But this suffering is only because we failed to realise that nothing is permanent, that all things are in flux, and if we can come to enjoy things without being attached to them, then we would suffer less.

Tibetan Buddhist monks have a ritual where they spend weeks painstakingly creating incredibly detailed and beautiful mandalas made out of coloured sand. Then, once they’re finished, they ritualistically sweep the sand away, destroying the mandala, and drop the collected sand into a river to flow back into the world, representing their embrace of impermanence.

The self

Another core philosophical insight from Buddhism was to question our sense of self. It’s natural to believe there is something at the core of our being that is unchanging, whether that be our soul, mind or personality.

But the Buddha noted when you try to pin down what that permanent aspect of ourselves is, you find there’s nothing there, just a stream of impressions, thoughts and feelings. So our sense that there is a persistent self is ultimately an illusion. We are just as dynamic and impermanent as the rest of the world around us. And if we can realise this, we can release ourselves from the pretense of what we think we are and we can just be.

Interestingly, this is very similar to an observation made by the 18th century Scottish philosopher David Hume, who said when he introspected, he could never settle on the solid core to his self. Rather, his self was like a swarm of bees with no boundary and no hard centre, with each being an individual thought or experience. The Buddha would likely have enjoyed this analogy.

Meditation

One of the aspects of Buddhism that has had the most lasting impact is the practice of meditation, particularly mindful meditation. The recent mindfulness movement is based on a form of Buddhist meditation that encourages us to sit quietly and let our thoughts come and go without judgement. Essentially, we must ignore our thoughts in order to control and be free from them. Modern science has shown that this kind of meditation can reduce stress and improve our focus and mood.

Buddhism is not only the fourth largest religion in the world with over 500 million adherents today, and third largest in Australia, but it continues to be a rich vein of philosophical inquiry.

Western philosophy was rather slow to take Buddhism seriously, but there are now many Western philosophers who are engaging with Buddhist ideas about reality, knowledge, the mind, the self and ethics.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Confirmation bias: ignoring the facts we don’t fancy

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Can we celebrate Anzac Day without glorifying war?

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

How can you love someone you don’t know? ‘Swarm’ and the price of obsession

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

The ethics of smacking children

BY Dr Tim Dean

Dr Tim Dean is Philosopher in Residence at The Ethics Centre and author of How We Became Human: And Why We Need to Change.

Big Thinker: Friedrich Nietzsche

Friedrich Nietzsche (1844—1900) is one of the most controversial figures in contemporary philosophy.

A German philosopher and cultural critic who is well known for his proclamations on God, truth, morality, power, aesthetics, the self and the meaning of existence, Nietzsche has had an enduring influence on Western philosophy.

Making use of a creative writing style, such as aphorisms and emotive essays, Nietzsche’s doctrines have been famously misappropriated by those seeking to further their own political ends (for example, Hitler and the alt-right). He was seen as an early existentialist because of his insistence on existence preceding essence, and the importance of looking to yourself – rather than God, society, family or friends – to identify what values you choose to live by.

Live your life like an artist

In Nietzsche’s first major work, The Birth of Tragedy (1872), the idea of living life creatively is embodied in his idea of living life as an artist. This involves combining two energies: the rational Apollonian and the passionate Dionysian. (In Greek mythology, Apollo is the god of logic and rational thinking, and Dionysus the god of instinct and emotion.)

Nietzsche worried the society of his time and classical thinkers like Socrates and Descartes– both Rationalists – only emphasised the Apollonian, neglecting the role of the Dionysian. Nietzsche thought it was important to balance our rationality with our sensual and passionate experience of life, and he saw this balance best depicted in ancient Greek tragedies.

Nietzsche insisted Greek tragedy achieves greatness through the inclusion of both Apollonian creative energy which is responsible for the dialogue, and Dionysian energy which inspires the music or chorus. In the plays, the two work together as the meaning of the words are enhanced by the accompanying melody. Using Greek dramatic artworks as an example, we can learn from great art to see the beauty in life.

“Without music, life would be a mistake.” – Nietzsche

The tragic spectator is united with others in the shared experience of being human. For Nietzsche, life without emotion, art and the creative energy of the Dionysian is bleak. A balance between Dionysus and Apollo allows for pluralistic and authentic modes of expression that are rational as well as creative. Aesthetic ideals also appear in his later writings, such as The Will to Power (1901), where Nietzsche writes, “Art as the redemptionof the man of action… Art as the redemption of the sufferer”.

Nietzsche advocated for a series of values or virtues we should adopt – namely, active, life affirming values, as opposed to the life denying or passive and ‘slave like’ values he detested. The latter he saw exemplified in the institutionalisation of Christianity, which, he believed, served to reinforce the power of the few at the expense of the many.

Believing the idea of a punitive God promoted by the church of his time to be a human invention, he famously declared:

“God is dead … And we have killed him.”

The Superman or Nietzsche’s Übermensch

Nietzsche emphasises an individualistic development and construction of self, summed up in the notion of the will to power. Claiming we ought to seek control over ourselves, Nietzsche holds up the Superman (yes, Nietzsche was misogynistic, but for our purposes we can extend this concept to include women), or Übermensch, as the pinnacle of human potentiality in terms of power and integrity in a broad sense of the word.

Nietzsche’s Übermensch is imagined as Zarathustra, a Christ-like figure who delivers an anti-sermon on the mount, a character with whom Nietzsche identifies. In The Gay Science (1882), it is the Superman who creates strengths out of his weaknesses and thus styles his character – a “great and rare art!”

This existentialist ideal – that each individual creates one’s self in a manner pleasing to them – threatens to collapse into extreme relativism or subjectivism. Yet, despite the fact the Superman goes “beyond good and evil”, Nietzsche is a moralist with definite views on what is condemnable.

“No one can construct for you the bridge upon which precisely you must cross the stream of life, no one but you yourself alone.” – Nietzsche

One way we are invited to test whether or not our chosen action is the right one is given to us in Nietzsche’s doctrine of eternal recurrence. “The Greatest Weight” in The Gay Science tells of a demon who confronts us, suggesting we must relive every single moment of our life, every choice and its consequences, eternally.

We are asked whether we would celebrate this as a gift or curse the unending misery it presents. The Superman would embrace the opportunity due to their authenticity and the fact they made each choice consciously, willing to accept full responsibility for their life.

Such a thought experiment offers an overly ambitious understanding of freedom and free will as a positive force. Yet it provides the reader with an interesting challenge when making decisions. Knowledge of an eternal recurrence would fundamentally change the way we lead our lives and inform the choices we make. If taken seriously, one could not help but try to act authentically – or, alternatively, not act at all.

Ever the rebellious teenager of philosophy, Nietzsche continues to give us pause for much thought, challenging us to live authentically and take unflinching responsibility for our lives.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Progressivism

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships, Science + Technology

Periods and vaccines: Teaching women to listen to their bodies

Big thinker

Health + Wellbeing, Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Big Thinker: Judith Butler

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

But how do you know? Hijack and the ethics of risk

BY Dr Laura D’Olimpio

Dr Laura D’Olimpio is senior lecturer in philosophy of education at the University of Birmingham, UK, and co-edits the Journal of Philosophy in Schools.

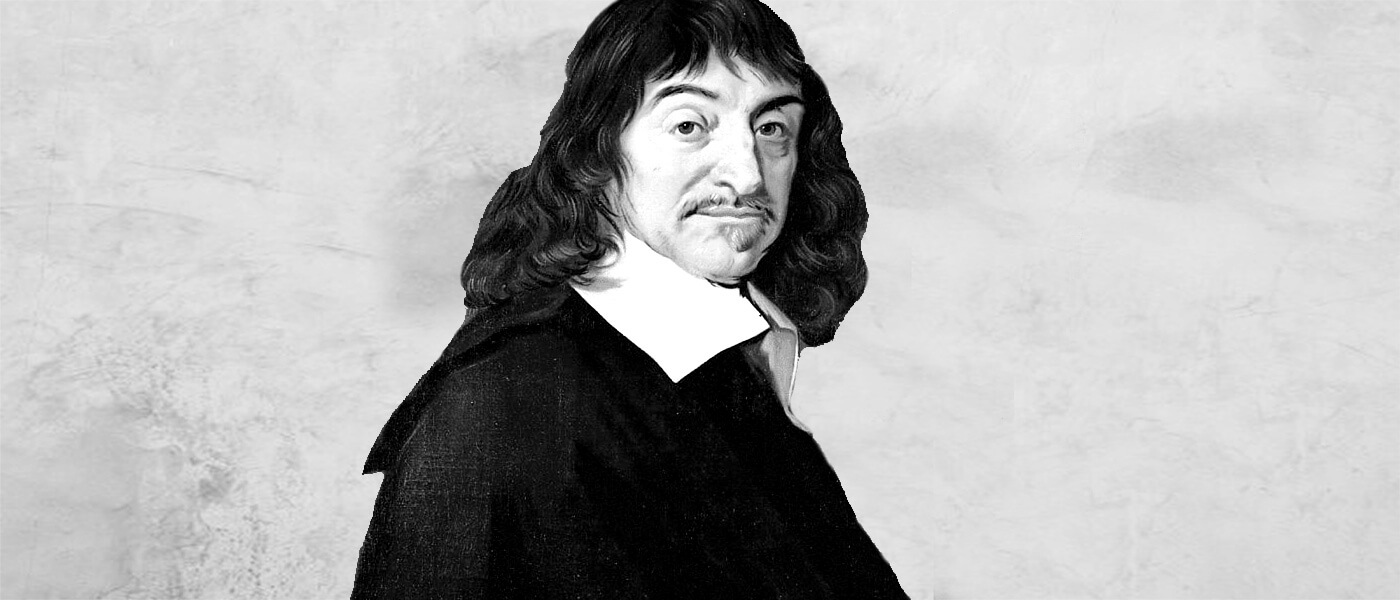

Big Thinker: René Descartes

René Descartes (1596—1650) is famous for the phrase, “I think, therefore I am”. He was a Frenchman writing in the early 17th century and was preoccupied with the question: What can we know for certain?

Descartes details a method of doubt in his key text Meditations on First Philosophy, published in 1641. It becomes crucial for rationalists that seek infallible knowledge. Rationalists rest their epistemological claims on pure reason, without recourse to the senses or experience (unlike the empiricists). Epistemology is the philosophical study of knowledge.

At a time when scholars were writing in Latin, Descartes wrote in French so anyone who was literate in the common language of his place could read his work. His writing style is friendly and approachable, so it feels as though you are having a conversation with him. His sceptical inquiry into what we can know commences with the question:

Can my senses be trusted?

Descartes describes himself sitting in front of a log fire in his wood cabin, smoking a pipe and questioning whether or not he can be sure that he is awake and alert as opposed to asleep and dreaming. How can we know the difference, he asks, when sometimes, in our dream state, we feel as though we’re awake even though we’re not?

Using the first person point of view, Descartes ponders on the fact that he tends to use his senses to be sure he exists and that the world around him is real, but the senses can sometimes be deceived. Our eyes often play tricks on us – as proven by any optical illusion – so how can we trust something that tricks us even once?

Cartesian scepticism (Cartesian being the adjective to describe the school of Decartes’ thought) concludes ultimately all I can be truly sure of is that I am a thinking thing. Descartes’ famously declared:

“Cogito ergo sum: I think therefore I am.”

Descartes posits the only thing I can be sure of is that I exist because even when I doubt that, there is an “I” doing the doubting. The “I” that thinks or doubts, must surely exist, he claims.

For Descartes the mind is more knowable than the body, and he equates the human Soul with the mind. For him, the mind is the essence of a person.

As a mathematician and a ‘natural scientist’ Descartes sought to prove that truths of the world were as immutable as rational, logical mathematic proofs. After he has proven that “I think, therefore I am” is as secure a foundation for knowledge as “1 + 1 = 2” Descartes goes on to use a thought experiment in order to consider whether we can be sure God exists.

The Evil Genius thought experiment

Descartes’ thought experiment of the evil genius asks us to imagine there exists, instead of an entirely good and powerful God, an entirely powerful, all-knowing Malevolent Demon. The idea here is that this Demon could make us think we are experiencing the world as it truly is, but we aren’t really. We could be tricked by this Evil Genius, and we may not be able to trust any knowledge we receive about the world from our senses. Ultimately Descartes relies upon an Ontological or Rational Argument to prove that God exists and if God exists, then we can trust our senses as God would not fool us in such a way as the Evil Demon might.

The incredibly powerful questions Descartes asks still inform many of our science fiction fears as we wonder whether or not the world truly is as it appears to us. We can still see the power of doubting and if we take this worry too seriously, we can imagine being paralysed with fear, unable to do anything! Many of us accept that our senses can be tricked but we know that we just have to go on trusting them anyway and hope for the best.

This sceptical method Descartes outlines whereby we check what we believe to be true and question what we assume to be real is useful if we think of it in terms of seeking evidence for the beliefs we are taught and the assumptions we hold. Considered in this way, Descartes offers us a great tool for self-reflection. However, if we take this thought experiment seriously we may never be sure that even we ourselves exist!

In the 18th century, David Hume suggested that even the assumption of an ‘I’ that doubts is an illusion. Hume says all we have to go on is a string of conscious experiences. Whether we are truly awake or dreaming right now is something we may not be able to answer with absolute accuracy, a doubt played out in famous films like The Matrix and Inception.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Enough with the ancients: it’s time to listen to young people

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

The Ethics of Online Dating

WATCH

Relationships

Unconscious bias

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Free markets must beware creeping breakdown in legitimacy

BY Dr Laura D’Olimpio

Dr Laura D’Olimpio is senior lecturer in philosophy of education at the University of Birmingham, UK, and co-edits the Journal of Philosophy in Schools.

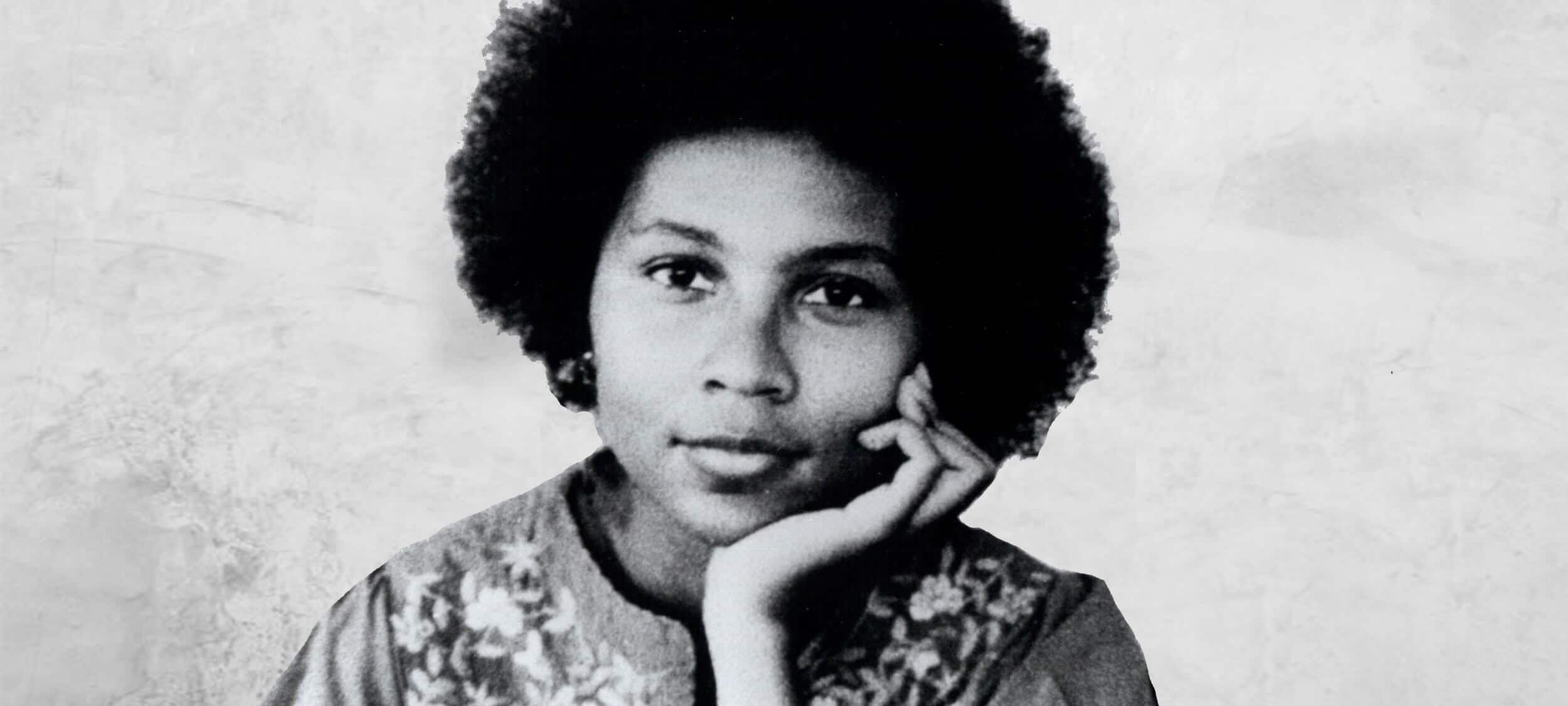

Big Thinker: bell hooks

An outspoken professor, author, activist and cultural critic, bell hooks (1952-2021) drew attention to how feminism privileges white women’s struggles, while advocating for a more holistic way of understanding oppression.

Born Gloria Jean Watkins, bell hooks was a child who spoke back. Growing up in a segregated community of the south-central US state Kentucky, she fought against the ways in which her family and society sought to relegate her into a docile, black female identity. This refusal to be complicit in perpetuating her own oppression would define her life and career as a leader in black feminist thought.

It was when she first spoke back in public that she initially identified with her self-claimed moniker. An adult had dismissed her with a comparison to Bell Hooks, her maternal grandmother, in whose bold tongue and defiant attitude she found inspiration. She decapitalised the initials in order for others to focus on the substance of her ideas, rather than herself as a person.

hooks would become a prolific author and commentator. With notable titles including Talking Back, Ain’t I a Woman? and From Margin to Centre, her work scrutinises and challenges the ways in which media, culture and society uphold dominant oppressive structures.

Interlocking oppressions

A popular version of second wave feminism posited that all systems of oppression stemmed from patriarchy. This, hooks rejected. Instead, she introduced the idea that different types of oppression are interlocking and power is relational depending upon where you’re located on the matrix of class, sex, race and gender – which is not unlike the ideas underpinning the currently popular intersectional feminism.

hooks invented the term ‘imperialist white supremacist capitalist patriarchy’ to emphasise the multidimensionality of these power relations. She continues to use it today.

At the time, hooks’ paradigm was considered radical in that it undermined the notion there was a fundamentally common female experience. Many assumed this was vital for feminist solidarity to be forged and political unity maintained. Sisterhood was more complicated than that, hooks said – and to deny the uniqueness of each woman’s status and circumstance was another form of oppression.

Bold and to the point

While coming from academia, hooks strives to make her ideas easily accessible to a broad audience. Her writing style is free of jargon and often humorous, and she regularly appears in documentaries, open venues and television talk shows.

hooks is also renowned for focusing a sharp critical lens on popular culture, showing a strong opposition to political correctness. She’s criticised Spike Lee’s films, media coverage of the OJ Simpson trial and the lauded basketball documentary Hoop Dreams.

She also hasn’t held back her thoughts on prominent feminists.

hooks criticised Madonna for repudiating feminist principles by chasing stardom, and fetishising black culture in her film clips and live shows while reinforcing stereotypes of black men as violent primitives in a 1996 interview.

Twenty years later, she called the pop queen of lady power Beyoncé an ‘anti-feminist terrorist’, citing concern over the influence sexualised images of her have on young girls.

hooks also expressed disappointment Michelle Obama positioned herself as the nation’s ‘chief mum’, saying that by effacing her identity as an Ivy League educated lawyer, she was appeasing white hatred.

Oppositional gaze

Laura Mulvey introduced the theory of the ‘male gaze’ in the ’70s. It explains how images – particularly Hollywood mainstream images – are created to reproduce dominant male heteronormative ways of looking. hooks, who was fascinated with film as the most ‘efficient’ ideological propaganda tool, coined an associated term on black spectatorship: the ‘oppositional gaze’.

Looking has always been a political act, hooks argued. For subordinates in relations of power, looks can be “confrontational, gestures of resistance” which challenge authority. Had a black slave looked directly at a white person of status, they risked severe punishment – even death. Yet “attempts to repress our/black people’s right to gaze had produced in us an overwhelming longing to look, a rebellious desire, an oppositional gaze,” writes hooks.

“By courageously looking, we defiantly declared: ‘Not only will I stare. I want my look to change reality.’”

Black spectatorship of early Hollywood cinema was processed through this oppositional gaze. It was abundantly clear to these viewers, hooks writes, that film reproduced white supremacy. They saw nothing of themselves reflected in this white-washed fantasy realm. Black independent cinema emerged as an expression of resistance.

At the same time, hooks saw television and film as a site where black viewers were able to subject white representations to an interrogative gaze. Carried out in the privacy of the home or in a darkened cinema, this action also carried no risk of reprisal. That black men could look at white female bodies without fear was hugely significant – it was only 1955 when 14-year-old African American Emmett Till was lynched after being accused of offending a white woman in a Mississippi grocery store.

But while black male spectators “could enter an imaginative space of phallocentric power,” the experience of the black female spectator was vastly different, hooks writes. In both white and black productions, the male gaze still overdetermined screen images of women, and frequently idolised white female stars as the supreme objects of desire.

This continued the “violent erasure of black womanhood” in screen culture, making identification with any of the depicted subjects disenabling. While this denied black women the typical joys of watching, the fact that they “looked from a location that disrupted” meant that they could become “enlightened witnesses” through critical spectatorship.

Modern feminism in crisis

Despite the advances of women in the workplace, hooks nonetheless sees today’s feminism in a state of crisis. Firstly, she believes that we still haven’t addressed egalitarianism in the home, leaving women belittled and frustrated in heteronormative relationships.

She also believes that feminism today has lost its radical potential, in that it has converged too closely with radical individualism. Feminism does not mean that as a woman “you can do whatever you want, that you can have it all”, she says. Instead, if you’re to live inside a feminist framework, you need to undertake specific everyday actions. For this reason, hooks believes there are very few true living feminists.

Still, she remains a firm advocate of feminist politics, saying “My militant commitment to feminism remains strong…”

…and the main reason is that feminism has been the contemporary social movement that has most embraced self-interrogation. When we, women of color, began to tell white women that females were not a homogenous group, that we had to face the reality of racial difference, many white women stepped up to the plate. I’m a feminist in solidarity with white women today for that reason, because I saw these women grow in their willingness to open their minds and change the whole direction of feminist thought, writing and action.

This continues to be one of the most remarkable, awesome aspects of the contemporary feminist movement. The left has not done this, radical black men have not done this, where someone comes in and says, “Look, what you’re pushing, the ideology, is all messed up. You’ve got to shift your perspective.” Feminism made that paradigm shift, though not without hostility, not without some women feeling we were forcing race on them. This change still amazes me.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

WATCH

Relationships

What is ethics?

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

Where are the victims? The ethics of true crime

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships, Society + Culture

In the face of such generosity, how can racism still exist?

Explainer

Relationships