A new era of reckoning: Teela Reid on The Voice to Parliament

A new era of reckoning: Teela Reid on The Voice to Parliament

Opinion + AnalysisPolitics + Human RightsRelationships

BY The Ethics Centre 22 MAY 2023

Later this year Australians will be asked to vote in a referendum on a Voice to Parliament. Can this conversation for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander constitutional recognition reconcile the truth of Australia’s past? Or have we embarked on a new era of reckoning with the risk that comes with a referendum?

In April 2022, Proud Wiradjuri and Wailwan woman and lawyer, Teela Reid sat down with Dr Simon Longstaff AO to discuss what reckoning means to her, what we need to make an informed decision on this vote, and what it means for us – collectively and individually.

Dr Simon Longstaff: When I think of reckoning, three things come to mind. Firstly, there’s ‘reckoning’ as in finding your bearings, dead reckoning. There’s another sense in which you reckon up the bill. And then there’s the third sense in which reckoning can be taken as a moment of recognition of one’s responsibilities and making us confront the reality of who and where we are, and what we’ve done. Perhaps we can touch on all three of those…

Teela Reid: My essay, Reckoning, Not Reconciliation, was born out of a frustration with the concept of reconciliation. I had attempted to dismiss it in some ways – whether that was to be provocative or just trying to grapple with my own sense of the world. The past three, almost four decades, has been defined in so-called Australia under this notion of reconciliation. And so, for me, as a Wiradjuri Wailwan woman, the life that I have been fortunate to live, had nothing to do with reconciliation, but it was in fact in spite of it. For me, having grown up in my community with the stories of my ancestors, my paternal and maternal lineages being hounded onto missions, laws passed so we couldn’t speak our native tongue, this notion of reconciliation kind of popped up.

I remember growing up in that community and then walking into school where we were trained that this notion of reconciliation was to make us feel good. There was almost a sense of denial of the truth. I remember, for example, learning about the Anzacs and there were no soldiers that we were told about that were Aboriginal men or women. And then I’d walk home and my grandparents would sit me around the campfire and give me a whole different education.

I remember just feeling really frustrated with the world. I want to unravel that and unpack this notion of reckoning. To me, it’s about everyone on this continent embracing the discomfort of the hard work we need to get done.

Dr Simon Longstaff: How do you look at the obligations you have – in a structure where elders still are the most significant decision makers within a community – and the need to balance that cultural obligation with obligations arising in a structure like the law; where it’s about the quality of reason, the precision of language and the authority of precedent?

Teela Reid: The western law is a discipline, it’s a practice. I vividly recall being at law school wanting to throw my textbooks up against the library when we were learning about Dicey’s rule of law where we’re all equal before the law. I remember thinking “How do I reconcile this with the stories that I know?” Clearly, the law has never treated my people fairly. There’s never been a fair go in this country for First Nations Peoples. So having those stories in my heart and in my spirit, I still took the opportunity that I was given to go to law school and now to practice law. It’s something I don’t take lightly at all, because I think we would be much worse off as a peoples if we were to take those opportunities for granted and not do the hard yards and live out those opportunities to empower our people.

Dr Simon Longstaff: Can these different definitions of ‘reckoning’ exist side by side? Or is that a very significant tension in your life?

Teela Reid: It’s a constant tension, to be very frank. It is a very constant tension to not lose yourself as a First Nations woman in this place that’s now called Australia and you’re constantly walking a fine line. When I think about reckoning, it’s also about power. It’s about who has the authority to make decisions in different contexts while at the community level our governance systems operate in a very specific way. I think that’s what Australia forgets. We have very ancient governance systems here still very much intact. They might not be written in legislation or rule books, but they’re passed down orally through our ways of knowing and being.

We have this higher order in Australia where there’s parliament, there’s states, there’s territories, there’s people making all these different decisions, but at the very heart of that, there is still the omission of the First Nations and there’s still an act of erasure in that. And the symbols are everywhere. It’s in the flag, it’s in the anthem, it’s in these ways that Australians speak their identity that I just don’t relate to.

Dr Simon Longstaff: The concept of ‘payback’ is sometimes misunderstood as if it’s based in the need for revenge. Instead, it’s about those who have done wrong making restoring balance to the community – paying back what has been taken to those who have suffered loss. Is that the kind of reckoning that you have in mind – bringing it to that point where people recognise loss as a give and take?

Teela Reid: It’s about the reconciling of the balance. There does need to be compensation, there does need to be these tough decisions and reparations for what First Nations Peoples have lost there.

The other way in which I see it, there is a level of discomfort that comes down to this truth telling notion that we’re going to need to embrace. Where Australians are at now – each one of you are advocates, you’re campaigners. You have agency in this movement. Reckoning is going to be a really difficult process, unlike reconciliation where we’ve all felt good with our wraps, our cupcakes and our teas. No, this is going to be quite difficult.

For so long, for 250+ years, as a nation we’ve avoided that discomfort that comes with trying to heal these wounds. Because you might not see the physical wounds, but they’re very deep and they’re intergenerational. When we think of reckoning, we’re all going to have to step up to the plate. And often what happens in a truth telling process, it’s that First Nations Peoples get the onus of having to speak our truth, when in fact white Australia needs to speak its truth. What did your ancestors do to my ancestors? Let’s start to have an open dialogue and take responsibility for that pain. Because I don’t think that we can heal until we reckon with the discomfort and the pain that I think as a nation is going to take many years to get through.

Dr Simon Longstaff: Whatever the result, the proposed referendum on a Voice to Parliament is going to be an extraordinary moment. What are your hopes at this point?

Teela Reid: I hope that people are willing to step up and be engaged and make informed choices for themselves in a conversation that should absolutely be based on the facts and not one in which we should be enlivening racism or anything like that. I do believe it’ll pass. I think there is so much goodwill in the Australian community.

If you look at history, the most successful referendum in 1967, shows that Australians actually feel very deeply on this issue. I’ve travelled to lots of different parts of the country, and engaged with fence seaters or people who want to protest to these kinds of conversations. By the end of it, you sit down, you listen, you work through these conversations and people’s hearts really get it.

Dr Simon Longstaff: Is this a beginning of a new set of possibilities in this country?

Teela Reid: I do believe it is. We all know the Uluru Statement has called for a First Nation’s Voice. One of the things I am grappling with both in the legal sense and the moral sense, it’s the enormous compromise our people have to make decade after decade after decade for this nation to just have a breakthrough. It happened with land rights. The Barunga Statement was gifted to Hawke. Hawke promised a treaty, he gave the nation reconciliation. It’s probably why we’re three, four decades behind right now. I don’t think that Prime Ministers like Hawke should be revered for what they’ve done. Even around when Whitlam came in for his short time in power, there were decades of activism and movements that were demanding big things, big changes. And it was only because of that activism that within those three, four years there was able to be this watershed moment of legislation and changes.

One of the things I am grappling with both in the legal sense and the moral sense, it’s the enormous compromise our people have to make decade after decade after decade for this nation to just have a breakthrough.

And so here I am thinking now, there’s another compromise being made. Perhaps this is more my moment of having to grapple with the way in which compromises are made in the political space.

I hope that everyday Australians are able to take this opportunity this year to actually reflect and educate themselves on the bigger picture and part of the story to this. Because we’re only really seeing it through that one little kind of myopic lens now that there’s going to be one ballot box and you’re going to be voting yes or no. But there is so much more to this.

Simon Longstaff: Are you optimistic that people understand this? Can we resolve the question of legitimacy?

Teela Reid: I do believe it’ll pass, yes. I think there’s so much good faith and goodwill in the people. The strategy behind this movement is correct. Going to the people and not the politicians is what changed this nation. At every single turning point the only reason it’s on the national agenda is because of everyday Australians. It won’t be easy. I think that people shouldn’t get complacent about where we are now. Between now and the ballot box, every single one of you is going to have start your own campaign. Take this extremely seriously. For someone like me, it doesn’t stop.

For everything you need to know about the Voice to Parliament visit here.

This is an abridged version of In Conversation with Teela Reid. Watch the full discussion below.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Science + Technology

The ethics of exploration: We cannot discover what we cannot see

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Agree to disagree: 7 lessons on the ethics of disagreement

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

The self and the other: Squid Game’s ultimate choice

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights

Why fairness is integral to tax policy

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

I'm really annoyed right now: 'Beef' and the uses of anger

I’m really annoyed right now: ‘Beef’ and the uses of anger

Opinion + AnalysisRelationshipsSociety + Culture

BY Joseph Earp 15 MAY 2023

Beef, the acclaimed new Netflix show, starts with an incident of one of the most commonplace examples of extreme emotion in our society – road rage.

We’ve all been there. You’re having a bad day. Or, if you’re the two heroes of Beef, a bad life – Danny (Steven Yeun), is a frustrated contractor, has sailed from one disappointment to the next, while Amy (Ali Wong), has big dreams that she can’t quite seem to realise. In another life, these two might have joined forces to combat the stresses that seem ready to swallow them whole. Instead, Danny almost runs into Amy in a brutalist parking lot.

Rather than either of them letting this go, the pair escalate their titular beef. They swear at one another. They make threatening motions with their cars. And then, before they know it, they’re all-out-furious, embroiled in a comically overblown chase sequence on the highway.

And it doesn’t end there, either. After this one act of aggression, Danny and Amy become locked in a series of escalating vengeful manoeuvres, from pissing on each other’s bathroom floors to all-out violence. It’s one incident of rage that ruins both of their lives. And, most troubling of all, Danny and Amy seem to love their fury. They embrace it totally, even as houses burn to the ground around them.

The consequences of anger

Clearly, Beef tells us that anger has the ability to escalate – that it’s an emotional state that can start minor, and then, if we don’t do anything about it, has the power to totally consume us. As Jennifer S. Lerner and Larissa Z. Tiedens note in their paper Portrait of the Angry Decision Maker, anger has “uniquely captivating properties” – if we’re not careful, it’ll make us one-track minded.

It’s partially for this reason that anger is often viewed as a “negative” emotion, one we would do better without. As philosophers Paul Litvak, Jennifer Lerner, and Larissa Z. Tiedens point out in their paper Fuel In The Fire, “anger makes people indiscriminately punitive, indiscriminately optimistic about their own chances of success, careless in their thought, and eager to take action.”

The angry person is not typically viewed as the one in the best place to make judgements. The angry person can act, as Danny and Amy do, irrationally, frequently moving against their own best interests. How many people have we all met whose rage has made them ruin a relationship that they value, or get themselves in trouble at work?

Much therapeutic practice is designed to eradicate negative emotions. Psychological practices like DBT (Dialectical Behaviour Therapy) encourage patients to rid themselves of anger, so that they might think clearly. This follows a version of the model of emotions favoured by the stoics. Marcus Aurelius, a Roman emperor and key proponent of the Stoic model, once wrote, “A real man doesn’t give way to anger and discontent, and such a person has strength, courage, and endurance—unlike the angry and complaining.”

On this model of emotional regulation, the right thing to do is take anger as a kind of emotional data, process it, wait for it to pass, and then act. Not out of anger. Deciding what to do only when calm.

What anger does

We might be quick to assume, like the Stoics, that anger is something to always be avoided. But in doing so, we ignore the way anger gets things done. Consider the anger at the heart of key civil rights movements from across the years. “If you’re not angry, you’re not paying attention,” has been a rallying cry used for everything from the fight for feminist rights, to the struggle against racism. There are clearly injustices that we are right to feel angry about.

In fact, dismissing someone’s concerns because they are angry has sometimes been used to try and deflate moves towards equality. Suffragettes, for instance, were often painted by the press as “hysterical” and out of control, their righteous fury seen as cause to eradicate their movements.

Moreover, anger has uniquely focusing effects. We see this in Beef. Before they almost crash into each other, Danny and Amy are aimless, buffeted around by forces bigger than them. The fury that they feel at one another focuses them. It is something that they control; something within their power. It inspires action from people whose lives have been marked by inaction.

So where is the point of balance between these two perspectives? Can we feel anger, and allow it to focus us, without allowing it to destroy our life, and make us bad decision makers?

The philosopher Martha Nussbaum believes so. Nussbaum is well-known for her rehabilitation of stoic philosophy – much of her philosophical work has been about bringing that ancient movement back into the light.

In her book Anger and Forgiveness, she embraces key features of the stoic opinion on anger. She calls anger a “trap”, and notes that she does not believe that anger “is morally right and justified.” For her, anger has all the negative qualities described above – it often leads to actions designed as “payback”, retaliative gestures that are seen to “assuage the pain or make good the damage.” She does not believe anger does this. She thinks it merely adds more hurt to a pile of hurt, hurting the aggressor as much as the victim they lash out at.

But Nussbaum does not dismiss anger out of hand. This makes her different to many stoics. She thinks anger is to be eradicated, but creates a related category to that feeling called “transition-anger.” This is not simply anger. It is not the desire to punish. It is not defined by wallowing in negative emotions. Instead, she describes the “entire cognitive content” of “transition-anger” as being made up of the thought, “How outrageous. That should not happen again.”

Transition-anger doesn’t make us merely lash out at those who have hurt us. Instead, it directs us towards positive forward action. We use it to focus ourselves. But that focus drives us towards good moral behaviour. It turns unmoved citizens into powerful figures of protest. It creates community, people united in their desire to make the world a better place.

Amy and Danny aren’t bad moral actors merely because they’re angry, then. They’re bad moral actors because they do the wrong things with their anger. It’s not that they should never have felt rage. It’s that they allowed that rage to make them ugly and cruel, when it should have made them kinder.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Science + Technology

Making friends with machines

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

Meet Eleanor, our new philosopher in residence

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

It’s easy to ignore the people we can’t see

Explainer

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Gender

BY Joseph Earp

Joseph Earp is a poet, journalist and philosophy student. He is currently undertaking his PhD at the University of Sydney, studying the work of David Hume.

Why we find conformity so despairing

We have a conflicted relationship with conformity. We are disdainful of others’ blind adherence to fads. We scoff at duck lips, rote woke speak, fiddle-leaf figs and picket-fence-and-two-kid aspirations.

But few of us go out on original limbs ourselves. We fear ostracisation as much as we do being labelled “sheeple”.

Conformity is an understandable evolutionary response to loneliness, the ultimate existential threat. We don’t have fangs or sharp claws; we don’t run particularly fast. Homo sapiens’ sole defence is our ability to coalesce into a collective that can then outsmart a predator. We are toast if we are cast out.

So we prioritise our belonging to a tribe or community over almost everything else, particularly in times of threat or uncertainty. At the height of the pandemic, former Obama Surgeon, General Vivek Murthy noted that a lot of nervous Americans were sharing anti-vax information on Facebook, even though they knew it to be false. Why? Because when we share friends’ and colleagues’ hysterical posts we demonstrate our tribal support. We are effectively saying, we sign up to the herd. Truth, when we fear being cast out, is a secondary concern.

Austrian philosopher and psychologist Erich Fromm wrote about this phenomenon in reaction to the rising opulence and conformity of the mid-1950s in his wonderful treatise, The Art of Loving. He pivots his thesis from the observation that humans experience a unique loneliness that stems from our self-conscious awareness that we will die (and therefore don’t matter). No other species, to our knowledge, has this awareness; we are alone in this aloneness. All of which sees us as unable to be present and “at One” with ourselves and the world around us for we are forever grasping into the future, seeking certainties.

Where does all this end up for us? Fromm argues, this disconnection from ourselves and the present, as well as the world around us, condemns us to a life searching for ways to unite and to experience the original Oneness as best we can.

One way to do this, he says, is by experimenting with drugs or by having sex. These work (rapturously!). But, alas, their effectiveness is short-lived.

The most effective and lasting way to connect, however, is to love. Fromm clarifies his definition of love. He’s specifically referring to productive love, which is the proactive giving of love, as opposed to the passive act of being loved. Love, to be clear, is not something we wait for. Or that we have to fear that we will miss out on. Love is what the alive “productive character” gets to experience.

But love is hard. And so the most common way we go about curing our loneliness and reconnecting with the One, is conforming. Doing as the herd does.

We conform by signing up for practices, mores and norms that corral us with the herd. We effectively hand our quest to live in the present, to be connected with nature and our nature, over to third parties – the church, governments, “democracy”, autocrats, cult leaders, and so on. Because, well, it’s easier than loving.

Of course, these institutions and models, whether it be Christianity, or Communism, evolved and took off to the extent to which they were able to make us feel less separate with their edicts and rulebooks.

But here’s the problem: we now delegate our non-separation to capitalism.

Fromm argues, as early as the 1950s, that mostly we conform to capitalism’s edicts and mores. We buy into its messaging. We mould the way we behave and look lured by the seductive promise that when we do we will belong to a big friendly herd of fellow… consumers (not citizens).

Capitalism is the most common way for humans to feel less separate because it’s the easiest way.

The system does all the work for us. We just have to hop on the conveyor belt and the jingles, the McDonald toys-with-purchase, the trickling down, the algorithms and the surveillance technology will take care of the rest.

Of course, same-sameness and herd mentality isn’t a problem in and of itself. Who cares if everyone cuts their hair into mullet for a season. But when it’s driven by capitalism, the abatement of our collective loneliness is not the driver. The vested interests of the market system are. Capitalism necessarily requires the stoking of our most selfish, individualist tendencies. The market system needs us to compete, to lapse into greed, to compare ourselves with others. And so capitalism’s promise comes at a massive price. Indeed, and ironically, the price is – yep! – our separateness.

But there’s also this: If we follow Fromm’s logic, conforming is, in effect, the cheap drug fix for the massive, original ache of our separation.

You see, while ever we revert to conformity as a way to connect, then we are dissuaded from doing it via the far more effective route, namely via the much harder practice – or art – of love. To this extent you could say that conformity stops us from choosing love.

Loving, of course, requires accessing a whole range of virtuous practices, such as courage and vulnerability. The comfy conveyor belt of consuming our way into the herd negates or demotivates us from practicing these virtues, too.

Plus, conformity in a democratic but capitalist culture is particularly powerful (and dangerous) because it sells the idea that the we remain very original and individualised in our behaviour. Our tattoo is radical (even though everyone has one); the world’s most popular SUV denotes adventurous “lone wolf”.

At least in an autocracy the people know they have lost their agency. They remain alive to it all; we slip into a distinct lack of curiosity and numbness, which we don’t fight or rise up against.

So what’s the alternative?

Jung asked in The Development of Personality: “What is it, in the end, that induces a man to go his own way and to rise out of unconscious identity with the mass as out of a swathing mist?” Jung answers his own question with the idea of having a “vocation”, a drive that comes from God. But in this instance we could argue that the way out of our stale, conveyor belt-ish conformity is to just do the more difficult path. Practice love! Now! Do not pass Go!

After all, as Fromm argues, conformity doesn’t satiate. “Union by conformity is not intense….it is calm, dictated by routine, and for this very reason often is insufficient to pacify the anxiety of separateness.” Fromm believes we need intensity for unification to feel real, to stick. Only love, he says, is sufficiently intense.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Science + Technology, Relationships

Love and the machine

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

It takes a village to raise resilience

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

How to respectfully disagree

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

CoronaVirus reveals our sinophobic underbelly

BY Sarah Wilson

Sarah Wilson is a multi-New York Times and Amazon best-selling author, podcaster, international keynote speaker, philanthropist and climate change advisor. Sarah is known globally for founding the I Quit Sugar movement – a digital wellness program and 13 award-winning books that sell in 52 countries – which saw millions around the world transform their health. In 2022 Sarah sold the business and gave everything to charity. Sarah is an experienced journalist and broadcaster. She was previously the editor of Cosmopolitan Australia at age 29; host of Masterchef Australia; was a News Corp journalist and columnist; and has hosted ABC’s Compass, Ten’s The Project and more. She is also a regular commentator on news and current affairs programs in Australia, the US and UK.

Meet David Blunt, our new Fellow exploring the role ethics can play in politics

Meet David Blunt, our new Fellow exploring the role ethics can play in politics

Opinion + AnalysisRelationshipsSociety + Culture

BY The Ethics Centre 8 MAY 2023

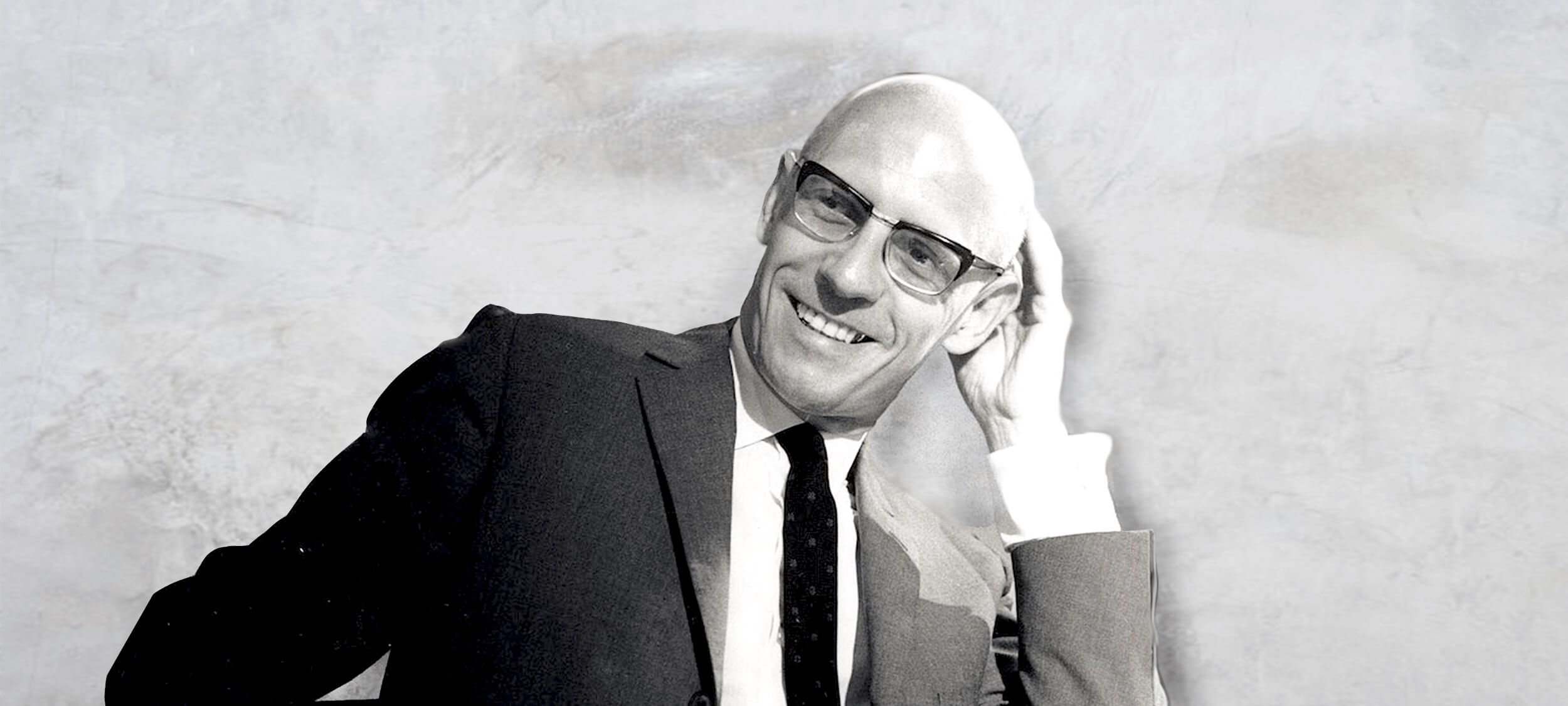

We’re thrilled to announce we’ve appointed Dr Gwilym David Blunt as an Ethics Centre Fellow.

A writer and commentator on global politics and philosophy, David has spent time as a Senior Lecturer in International Politics at City, University of London and as a Leverhulme Early Career Fellow at the University of Cambridge. Now based in Australia, David has published numerous books, appeared on ABC The Drum and Monocle Daily, and has written for The Conversation, ABC and International Affairs.

To welcome him, we sat down with David to discuss the important role ethics can play when it comes to politics, human rights and philanthropy.

What attracts you to the field of philosophy?

We are often told to ‘go with your gut’ when making decisions. This has always struck me as genuinely terrible advice. Our instincts can be conditioned by any number of prejudices or misconceptions. Philosophy is a way of interrogating these instincts and thinking systematically about hard questions.

How does your background in international politics and human rights shape your approach to philosophy and ethics?

International politics fascinates me because it is often treated as a place where ethics don’t apply. It’s seen as a place in which raw power determines the norms that govern politics, something that few would say is acceptable in domestic politics. Yet, this seems ridiculous.

Take the Russian invasion of Ukraine, many people around the world reacted in horror because wars of aggression are wrong. This is more than an intuition. Self-determination is grounded in an ethical judgement that people have a right to determine their collective destiny without interference. We might question the scope of this right, but most people will agree that at the very minimum it prohibits wars of aggression. There is clearly a place for ethics in world politics.

In fact it is more than a place, there is an urgency for ethics in world politics. The Covid-19 pandemic clearly showed how humanity as a whole faces shared challenges. The viruses that cause pandemics and the greenhouse gases that cause climate change don’t respect the arbitrary lines we draw on maps. We cannot hide behind closed borders and hope it all just goes away. These threats raise ethical questions about duties and responsibilities, where burdens lie, and what we owe to the future.

What kind of work will you be engaging with at The Ethics Centre?

The Ethics Centre is hosting me while I work on my next book which is on philanthropy. This is a topic that I’ve been interested in for a long time, but was on the side burner until the pandemic brought it back into focus. My work usually looks at the grimmer aspects of political philosophy, such as war, terrorism, and extreme inequality. So, it is nice to be working on something that gives some reasons to be hopeful about humanity. Although philanthropy raises a lot of interesting questions about justice, reputation laundering, and fairness.

I’ll also be writing some articles and assisting as a media spokesperson.

Which philosopher has most impacted the way you think?

It’s difficult to pick one, but I think it would have to be Philip Pettit, who isn’t a household name, but, along with Quentin Skinner, revived republicanism in political philosophy, which is what grounds my work. Now, don’t confuse republicanism with Donald Trump or right-wing MAGA politics or even with anti-monarchism. Republicanism is at its core a philosophy of freedom; it’s central claim is no person can be free if they are under the arbitrary power of someone else.

You have also done a lot of research on poverty and the distribution of wealth. What role do you think philanthropy and charity has or should have in that space?

I like to compare philanthropy with the façade of a building. It is something that beautifies, but it isn’t necessary to create a stable and functional structure. To continue this analogy, the parts of a building that keep it up, foundations and reinforced concrete, these are the province of justice. My worry with philanthropy is that it is taking up those structural roles, that it is subverting the role of justice. This isn’t a trivial matter because philanthropy is often characterised by the arbitrary power that republicans tend to worry about. Access to healthcare or education should not rest on the whim of a wealthy person, even if they are a good person, these are things that all people are owed as matter of right.

Your recent book Global Poverty, Injustice and Resistance argues our right to politically resist. We’re currently seeing some extreme cases of human right infringements around the world – what’s an example of resistance you’ve noticed that seems to be having a significant effect?

Resistance is such an interesting subject, because it covers such a wide range of activities. Most people tend to think of revolutions or mass civil disobedience as the paradigm examples of resistance, but I find the less visible forms of resistance more compelling.

I think the best example is illegal or irregular immigration for socio-economic reasons. This topic is one that generates a lot of extreme feelings in wealthy states like Australia and the United States, which is why I find it interesting. People who flee extreme poverty are voting with their feet against our current global political system, where many people are denied a reasonably dignified human life simply because they were born in the wrong country.

Many people’s first instinct is to say that illegal immigrants are doing something wrong, because they are breaking the law, but this goes back to what I said that the beginning of this interview: our instincts can be wrong.

We need to seriously start asking questions about why people cross borders illegally. It takes a lot for someone to leave their home to go to a distant land where they might know no one, have to learn new customs and language, and there is a chance they might die in the journey. We need to think about our complicity with the economic systems that produce avoidable poverty and exacerbate climate change, the push factors for this sort of migration. My hope is that this may help to create systemic change.

What are you reading, watching or listening to at the moment?

For work, I’m finishing up reading Paul Vallely’s massive Philanthropy: From Aristotle to Zuckerberg which is a good accessible examination of philanthropy and re-reading Will MacAskill’s What We Owe the Future for a short piece I’m working on. And I’m also revisiting some of the greatest hits of republicanism from Pettit and Skinner for a new YouTube series I’m doing.

For pleasure, I’m reading Donna Tartt’s The Goldfinch, which is really amazingly written. She’s one of those people who makes me actively jealous of their wordcraft. And I’m reading my wife I, Claudius before bed.

Watching, we are doing a nostalgia trip and rewatching the X-Files, which is fun even if the last few seasons are pretty bad. The sad thing about watching it in 2023 is that fringy, conspiracy theory stuff was just fun entertainment 30 years ago and now it has turned extremely sinister, which kind of drains a bit of the joy out of it.

Listening, I’m a big Last Podcast on the Left fan, because sometimes I just need to learn about cults, aliens, cryptids, and true crime. And since moving to Australia I’ve been getting into Australian music and have been bingeing King Gizzard and the Lizard Wizard.

Lastly, the big one – what does ethics mean to you?

Putting it simply, ethics is my ‘bullshit detector’; it helps me recognise my own bullshit, which keeps me from being complacent, and the bullshit of society at large, which seems to be really piling up.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Big thinker

Health + Wellbeing, Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Big Thinker: Judith Butler

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Metaphysical myth busting: The cowardice of ‘post-truth’

Big thinker

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Big Thinker: Eleanor Roosevelt

Opinion + Analysis

Science + Technology, Business + Leadership, Society + Culture

AI and rediscovering our humanity

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

ESG is not just about ticking boxes, it’s about earning the public’s trust

ESG is not just about ticking boxes, it’s about earning the public’s trust

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + LeadershipClimate + EnvironmentRelationships

BY Cris Parker The Ethics Alliance 3 MAY 2023

If businesses want to earn the public’s trust, they need to take ESG seriously, and communicate what they’re doing authentically and transparently.

In the eyes of today’s public, businesses must do more than just provide quality products and services, they also have a responsibility to be good corporate citizens and make a positive contribution to society and the environment. This is one reason why so many businesses have made a commitment to Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) standards.

ESG is a framework used to assess a business’s activities and performance on ethical and sustainable issues. This includes an organisation’s ability to safeguard the environment, manage relationships with employees, supply chains and the community, and how company leadership, shareholder rights and internal controls monitor the outcomes. Importantly, the framework serves as a tool to assess how an organisation manages risks and opportunities in our changing world.

The problem is that most members of the public don’t have a good understanding of ESG. According to the SEC Newgate ESG Monitor report, only 12% of Australians had a “good understanding” of ESG. This disconnect between ESG activities and public perception is a problem because it undermines trust in business, especially if ESG activities have been misrepresented.

Members of the Ethics Alliance gathered in April 2023 to discuss the importance of SEC Newgate’s research and consider challenges that organisations face in the way they address ESG and community expectations.

For starters, the ESG Monitor indicated that 38% of Australians feel completely uninformed about companies’ ESG activities. Interestingly, it also suggested 72% of people either “never” or “rarely” look at the ESG reporting, while only a mere 8% of people trust ESG reporting.

Some of this scepticism around ESG may have been cultivated due to it politicisation. In April 2023 the leader of the opposition, Peter Dutton, commented: “To be frank, some business leaders need to stop craving popularity on social media by signing up to every social cause, even though they may not believe in it.” This attitude acts in contrast to the global research from the 2023 Edelman Trust Barometer that shows 82% of people expect CEOs to take a public stand on climate change. And to Dutton’s point, they certainly expect authenticity.

The public holds high expectations for businesses to use their influence for good. SEC Newgate’s study showed that of those surveyed, 80% agree that companies have a responsibility to behave like good citizens and consider their impact on other people and the planet. It also showed that 66% of people are also willing to give a company a second chance if it was transparent about its mistake and stated how it would do better in the future.

If businesses want to live up to community expectations and strengthen their social value, then they need to carefully choose which ESG initiatives to focus on and ensure they have legitimacy in those areas. When evaluating, they should ask the following: Is it genuine? Is it meaningful? Is the organisation committed? And how do I know for sure or where is the proof?

By demonstrating a clear link between sustainability efforts and overall strategy, businesses can better align their initiatives with community expectations.

One starting point is a materiality assessment, which is a process to identify and prioritise the most relevant and significant ESG factors that have a substantial impact on the business’s operations, financial performance and stakeholder interests. This exploration can help identify the most pressing issues that align with the purpose and resonate with the community.

Other principles for organisations to consider when developing their ESG framework that emerged from The Alliance’s discussions were:

- Ethical conduct – including treating employees fairly, avoiding unethical practices, and minimising environmental harm.

- Giving back – which may involve investing in local communities, adopting environmentally friendly practices, or supporting social initiatives.

- Transparency and accountability –stakeholders, including consumers, employees, and shareholders, often have differing perspectives on ESG issues, making it challenging for businesses to balance these conflicting demands and trade-offs.

Communication also needs to be well considered by organisations in order to address the disconnect between the community’s need for transparent ESG information and their desire to learn about it. Connecting with stakeholders transparently about an organisation’s progress and mistakes can help meet these challenges.

ESG is about more than just accounting. It’s demonstrating a business’s responsibility and recognising the importance of sustainable practices in safeguarding our planet. ESG needs to be a whole company effort that is undertaken authentically and communicated transparently to the public that reflects its purpose, values and principles. The more businesses that do this, the more the public will understand what ESG is and the more they will come to trust businesses as being responsible corporate citizens.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

WATCH

Relationships

Consequentialism

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Mutuality of care in a pandemic

Big thinker

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Big Thinker: Michel Foucault

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

A new era of reckoning: Teela Reid on The Voice to Parliament

BY Cris Parker

Cris Parker is the former Head of The Ethics Alliance and a Director of the Banking and Finance Oath at The Ethics Centre.

BY The Ethics Alliance

The Ethics Alliance is a community of organisations sharing insights and learning together, to find a better way of doing business. The Alliance is an initiative of The Ethics Centre.

We already know how to cancel. We also need to know how to forgive

We already know how to cancel. We also need to know how to forgive

Opinion + AnalysisRelationships

BY Dr Tim Dean 1 MAY 2023

We have a well-worn script for how to behave when a public figure does something wrong. What we don’t have is a script for what to do if they make amends.

First comes the outrage, then the sharing, then the public condemnation, where the force of thousands of indignant wills declare that the wrongdoer is no longer a member of our moral community. Then we cancel.

This script is powerful. It is predictable. It helps remove a perceived threat. But it doesn’t heal the moral wound. It doesn’t rebalance the scales. It doesn’t include lines for rehabilitation, re-education or rebuilding moral capital. The script only tells us how to push people out.

What we need is another script, one we can use if they make amends. If the wrongdoer owns what they’ve done, if they express genuine contrition and issue a heartfelt apology, if they demonstrate a lasting change to their behaviour for the better, what do we do?

The missing script

The first thing to decide is whether we’re in a position to forgive at all. There are a couple of reasons why we might not be. For a start, we might not even be the right person to judge in the first place.

Many of us are quick to judge these days. The media and internet have opened us up to a world of outrages that call out for condemnation, and the frantic pace of modern discourse makes us feel like we must have an opinion on every issue. We are also often motivated to show solidarity with our in-group by sharing outrage over the same subjects, even if we know little about them. And the logic of second-order punishment – where we punish those who refuse to punish wrongdoers – means we fear retribution from our own team if we don’t jump on the outrage train.

But none of these are good reasons to jump to a hasty conclusion, based on a news headline, a couple of tweets and a few second-hand hot takes. Many of the issues we face are more complex than can be understood, let alone judged, without careful consideration. Many of the details are hidden from our view or veiled by the hasty or biased interpretations of others.

The second reason as individuals we might not be in a position to forgive is that sometimes the only person who can forgive is the individual who was harmed. I can’t unilaterally forgive a thief for stealing from you, or a celebrity for cheating on their partner. I simply lack the standing to speak on behalf of the person who was harmed.

However, there are cases where we, as members of a moral community, can be in a position to judge – and forgive – an act of wrongdoing. Acts of stealing or infidelity don’t just harm the victims, they violate the norms of our community. That’s why we still get outraged at things that don’t impact us directly or offensive acts that have no apparent victim.

This is a different kind of forgiveness. It’s not speaking on behalf of the victim, it’s speaking on behalf of the moral community. If the wrongdoer apologises and makes amends to those they’ve harmed, the community can accept that apology, drop the enmity towards them and welcome them back into the fold.

This kind of “public forgiveness” is an important part of a healthy moral community. Without it, the community pursues a purity culture that only knows how to push people out.

Set the bar

The next thing we should ask ourselves: what would the wrongdoer need to do to justify our forgiveness?

For some wrongdoers, the answer will be “there’s nothing they can do”. There are such things like terrorist attacks, mass shootings, genocide and violent sexual assault that we might not reasonably expect anyone to forgive, especially those directly affected.

However, we need to think carefully about what is considered unforgiveable, and not allow that category to grow too large.

Only the most serious moral transgressions should be considered unforgiveable. For everything else, we need to set the bar high enough that wrongdoers must earn their forgiveness, but not so high that the pariahs will one day outnumber the pure.

Similarly, when it comes to character there may be people whose behaviour is so consistently bad that we can conclude that they are beyond redemption. But we must be very cautious about inferring too much about character from only one example of wrongdoing.

There has been a trend in recent years of leaping from outrage at a particular act – say a poorly worded tweet or an off-colour joke – to condemnation of the individual’s entire moral fibre. It’s a tendency to see the slightest slip as revealing deeper moral corruption, proving they are unworthy of forgiveness or rehabilitation.

While it’s tempting to see others as having an immutable moral fibre and painting them as either virtuous or wicked, we must remember our moral fibre is malleable. Throughout the course of our lives, our own moral views evolve with changes in our circumstances and the influence others have on us. We must believe the same of others too. This means setting a very high bar before judging character.

Open the door

Once we have set an appropriately high bar, we should invite people clear it. We should look for signs that they are aware that what they did was wrong. They should own their actions and show they can articulate how they harmed others. This involves them recognising how their act was received, even if they didn’t intend for it to be received that way.

We should also look for signs of genuine remorse, which suggests that the wrongdoer shares our negative judgement of what they did. It shows their moral standards are aligned with ours.

When assessing a public apology, we can look for “costly” gestures that make that apology more likely to be authentic. A murmured apology in private, or delivered at a curated press conference may be less authentic than an unscripted public statement. Emotion matters too, but we should recognise that not all people feel or express emotion in the same way; just because someone isn’t in tears doesn’t mean they are not sincere.

Ultimately, what is most deserving of forgiveness is not words but actions. If someone changes how they behave in an enduring way, then that’s the most reliable sign that they have realigned their values to accord with those of the community. At that point, we should be inclined to invite them back into the moral community.

The final stage of the new script for public forgiveness mirrors the script for sharing outrage. Public forgiveness needs to be expressed in public. And those witnessing public forgiveness should read that as an opportunity to re-evaluate their own judgements of the wrongdoer and decide if they, too, are ready to forgive.

There are times when condemnation is justified. There are times when people ought to be cancelled. But if it’s a one-way street, we risk living in a culture where the circle of what – or who – is acceptable is forever shrinking. We need to have a pathway to redemption and forgiveness, and that pathway needs to become a script that we can all apply.

For a deeper dive on Cancel Culture, David Baddiel, Roxane Gay, Andy Mills, Megan Phelps-Roper and Tim Dean present Uncancelled Culture as part of Festival of Dangerous Ideas 2024. Tickets on sale now.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: The Other

Explainer, READ

Relationships, Society + Culture

Ethics Explainer: Shame

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

What Harry Potter teaches you about ethics

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Adoption without parental consent: kidnapping or putting children first?

BY Dr Tim Dean

Dr Tim Dean is Philosopher in Residence at The Ethics Centre and author of How We Became Human: And Why We Need to Change.

How can you love someone you don't know? 'Swarm' and the price of obsession

How can you love someone you don’t know? ‘Swarm’ and the price of obsession

Opinion + AnalysisRelationshipsSociety + Culture

BY Joseph Earp 19 APR 2023

When we first meet Dre (Dominique Fishback), the terrifying anti-hero of Swarm, she’s obsessed.

For years, she has been busy constructing a world with the pop singer Ni’Jah at its centre – the musician has become the yardstick by which Dre measures whether anything in her life is worthwhile. This isn’t just a casual interest for Dre. It’s everything.

And because it’s everything, before too long, Dre starts murdering in Ni’Jah’s name. In the world of Swarm, violently dispatching anyone who stands in the way of the Ni’Jah fandom is par for the course. Indeed, much of the show’s dark comedy comes from the messed-up, but eerily logical, motivation behind Dre’s bloodthirsty rampage, which takes her across the United States, and sees her dispatch both Twitter trolls and fellow fans.

No doubt then – love is at the centre of Dre’s life. Only, it’s a violent, obsessive kind of love. And a love that attaches itself to someone that Dre doesn’t even know.

She just gets me

Dre’s form of love is a parasocial one. She pores over the details of Ni’Jah’s life, sharing factoids about the pop star with her fellow stans. No matter that she doesn’t even know Ni’Jah, really. She doesn’t have to meet her. After all, she has Ni’Jah’s music, and music is the language of the soul, right?

This kind of romantic obsession is a common feature of the modern age, though it wasn’t invented by it. Certainly, parasocial relationships aren’t new. They go back as far as the fans who tore at classical composer Franz Liszt’s clothes, gripped by a fever called Lisztomania that resembles the hysteria that has met boy bands over the decades.

When people feel seen by art, it makes sense that they also feel seen by the artist that has made it. You love the music, and then you love the musician. This goes a long way to explaining the behaviour of modern stans, who are not content to merely listen to the newest pop album. They collate pictures of the popstar in question; try to learn details about their personal life; hang on to their every word.

Indeed, what sets Beyonce stans apart from Liszt fanatics is the way that technology has stepped up this fascination with the lives of artists. It used to be you had to mail in a self-addressed envelope to a Beatles fanclub to connect with likeminded folks. Now you can log on, sharing and ramping up your mutual obsession. All in it together.

What love makes us do

Parasocial relationships can spawn a range of immoral acts. They overstep the boundaries of privacy of artists, treating them like commodities, not people.

This is a violation of one of philosopher Immanuel Kant’s most important tenets – Kant says, use people as ends in themselves, their own people, rather than mere means. Pop stans don’t do this. They use popstars as mediums for their art.

Stans also tend to operate under a groupthink mentality, a kind of contagious sharing of values and emotions that the philosopher Derek Matravers called out in his book, Empathy. Matravers noted that crowds can “catch” feelings from each other – that if one person is angry, then a person who witnesses that anger will pick up on it, through what is known as “emotional contagion.” Then, that anger spreads. And when it spreads out of control, violence can occur.

That emotional catching is key to Swarm, and Dre’s obsession – she and her fellow stans whip themselves up into a frenzy of hatred, a virulence particularly directed towards the other. This other-directed hatred has been noted by philosopher Jesse Prinz, who argues that empathy and emotional contagion both tend to be triggered in the cases of perceived likeness. As in, if you think someone resembles you in important ways, you’re more likely to feel what they feel. That’s why groups form. Groups share perceived traits – in the case of Swarm, a love of Ni’Jah – and catch feelings of those in their group, without catching the feelings of those outside the group. Thus – an us and them mentality.

This in turn accounts for the behaviour we see in real life, outside of Swarm, particularly on Twitter. There, stans turn on people who commit the slightest perceived indiscretion, threatening, in some cases, their homes, livelihood, and health. Take the pop music critic, not named here to avoid kicking off a potential wave of abuse, who criticised a pop music stan and had her home address found, and threatening messages left on her voicemail.

A love that doesn’t change

It’s worth noting that parasocial relationships aren’t totally foreign to other forms of love. Many of us are guilty of turning the object of our infatuation into something other than what they are. Consider those early days of romance, when everything that the object of our affection has touched or produced seems blessed by a kind of glow – there’s the coffee cup they drank from, and then left at ours. There’s the toothbrush they used, on the bathroom mantle.

But what makes parasocial relationships different to others is the strange way in which they develop and change. Or, don’t change. When the person you love is right in front of you, your affection molds to their shape. They do things, and you respond to those things. They are human, so they fuck up, and your adoration changes in step with those fuck-ups.

Parasocial relationships lack that constant evolution. Pop albums don’t change. You listen to the new Taylor Swift album, and then months go by, and you listen to it again, and again, and again. Not a note has shifted since that first time. So your love can stay locked in that honeymoon phase – that obsessive, giddy kind of romance, consistent in intensity.

Without evolution, our passion is obsession, and obsession can turn us into bad ethical actors of all sorts.

This unchanging nature also explains that darker side of modern fandoms – the side targeted by Swarm. Dre doesn’t see Ni’Jah’s flaws. Doesn’t get exposed to the healthy regularity that romance descends into. That keeps her obsession at a fever pitch. One with such violent passion at its heart that it’s only a matter of time until it becomes literally violent.

Thus, Swarm, and indeed modern fandom itself, teaches us the ethical importance of evolution. Not only is a static love a dying love – how many relationships break up because of the horrifying routines that we can settle into, years into being with someone? The monotony of it all? Static love is also a dangerous love. Without evolution, our passion is obsession, and obsession can turn us into bad ethical actors of all sorts.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Living well or comfortably waiting to die?

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Climate + Environment, Relationships

ESG is not just about ticking boxes, it’s about earning the public’s trust

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

How to respectfully disagree

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Mutuality of care in a pandemic

BY Joseph Earp

Joseph Earp is a poet, journalist and philosophy student. He is currently undertaking his PhD at the University of Sydney, studying the work of David Hume.

A framework for ethical AI

Artificial intelligence has untold potential to transform society for the better. It also has equal potential to cause untold harm. This is why it must be developed ethically.

Artificial intelligence is unlike any other technology humanity has developed. It will have a greater impact on society and the economy than fossil fuels, it’ll roll out faster than the internet and, at some stage, it’s likely to slip from our control and take charge of its own fate.

Unlike other technologies, AI – particularly artificial general intelligence (AGI) – is not the kind of thing that we can afford to release into the world and wait to see what happens before regulating it. That would be like genetically engineering a new virus and releasing it in the wild before knowing whether it infects people.

AI must be carefully designed with purpose, developed to be ethical and regulated responsibly. Ethics must be at the heart of this project, both in terms of how AI is developed and also how it operates.

This sentiment is the main reason why many of the world’s top AI researchers, business leaders and academics signed an open letter in March 2023 calling for “all AI labs to immediately pause for at least 6 months the training of AI systems more powerful than GPT-4”, in order to “jointly develop and implement a set of shared safety protocols for advanced AI design and development that are rigorously audited and overseen by independent outside experts”.

Some don’t think a pause goes far enough. Eliezer Yudkowsky, the lead researcher at the Machine Intelligence Research Institute has called for a complete, worldwide and indefinite moratorium on training new AI systems. He argued that the risks posed by unrestrained AI are so great that countries ought to be willing to use military action to enforce the moratorium.

It is probably impossible to enforce a pause on AI development without backing it with the threat of military action. Few nations or businesses will willingly risk falling behind in the race to commercialise AI. However, few governments are likely to be willing to go to war force them to pause.

While a pause is unlikely to happen, the ethical challenge facing humanity is that the pace of AI development is significantly faster than the pace at which we can deliberate and resolve ethical issues. The commercial and national security imperatives are also hastening the development and deployment of AI before safeguards have been put in place. The world now needs to move with urgency to put these safeguards in place.

Ethical by design

At the centre of ethics is the notion that we must take responsibility for how our actions impact the world, and we should direct our action in ways that are beneficent rather than harmful.

Likewise, if AI developers wish to be rewarded for the positive impact that AI will have on the world, such as by deriving a profit from the increased productivity afforded by the technology, then they must also accept responsibility for the negative impacts caused by AI. This is why it is in their interest (and ours) that they place ethics at the heart of AI development.

The Ethics Centre’s Ethical by Design framework can guide the development of any kind of technology to ensure it conforms to essential ethical standards.This framework should be used by those developing AI, by governments to guide AI regulation, and by the general public as a benchmark to assess whether AI conforms to the ethical standards they have every right to expect.

The framework includes eight principles:

Ought before can

This refers to the fact that just because we can do something, it doesn’t mean we should. Sometimes the most ethically responsible thing is to not do something.

If we have reasonable evidence that a particular AI technology poses an unacceptable risk, then we should cease development, or at least delay until we are confident that we can reduce or manage that risk.

We have precedent in this regard. There are bans in place around several technologies, such as human genetic modification or biological weapons that are either imposed by governments or self-imposed by researchers because they are aware they pose an unacceptable risk or would violate ethical values. There is nothing in principle stopping us from deciding to do likewise with certain AI technologies, such as those that allow the production of deep fakes, or fully autonomous AI agents.

Non-instrumentalism

Most people agree we should respect the intrinsic value of things like humans, sentient creatures, ecosystems or healthy communities, among other things, and not reduce them to mere ‘things’ to be used for the benefit of others.

So AI developers need to be mindful of how their technologies might appropriate human labour without offering compensation, as has been highlighted with some AI image generators that were trained on the work of practising artists. It also means acknowledging that job losses caused by AI have more than an economic impact and can injure the sense of meaning and purpose that people derive from their work.

If the benefits of AI come at the cost of things with intrinsic value, then we have good reason to change the way it operates or delay its rollout to ensure that the things we value can be preserved.

Self-determination

AI should give people more freedom, not less. It must be designed to operate transparently so individuals can understand how it works, how it will affect them, and then make good decisions about whether and how to use it.

Given the risk that AI could put millions of people out of work, reducing incomes and disempowering them while generating unprecedented profits for technology companies, those companies must be willing to allow governments to redistribute that new wealth fairly.

And if there is a possibility that AGI might use its own agency and power to contest ours, then the principle of self-determination suggests that we ought to delay its development until we can ensure that humans will not have their power of self-determination diminished.

Responsibility

By its nature, AI is wide-ranging in application and potent in its effects. This underscores the need for AI developers to anticipate and design for all possible use cases, even those that are not core to their vision.

Taking responsibility means developing it with an eye to reducing the possibility of these negative cases becoming a reality and mitigating against them when they’re inevitable.

Net benefit

There are few, if any, technologies that offer pure benefit without cost. Society has proven willing to adopt technologies that provide a net benefit as long as the costs are acknowledged and mitigated. One case study is the fossil fuel industry. The energy generated by fossil fuels has transformed society and improved the living conditions of billions of people worldwide. Yet once the public became aware of the cost that carbon emissions impose on the world via climate change, it demanded that emissions be reduced in order to bring the technology towards a point of net benefit over the long term.

Similarly, AI will likely offer tremendous benefits, and people might be willing to incur some high costs if the benefits are even greater. But this does not mean that AI developers can ignore the costs nor avoid taking responsibility for them.

An ethical approach means doing whatever they can to reduce the costs before they happen and mitigating them when they do, such as by working with governments to ensure there are sufficient technological safeguards against misuse and social safety nets in place should the costs rise.

Fairness

Many of the latest AI technologies have been trained on data created by humans, and they have absorbed the many biases built into that data. This has resulted in AI acting in ways that negatively discriminate against people of colour or those with disabilities. There is also a significant global disparity in access to AI and the benefits it offers. These are cases where the AI has failed the fairness test.

AI developers need to remain mindful of how their technologies might act unfairly and how the costs and benefits of AI might be distributed unfairly. Diversity and inclusion must be built into AI from the ground level through training data and methods, and AI must be continuously monitored to see if new biases emerge.

Accessibility

Given the potential benefits of AI, it must be made available to everyone, including those who might have greater barriers to access, such as those with disabilities, older populations, or people living with disadvantage or in poverty. AI has the potential to dramatically improve the lives of people in each of these categories, if it is made accessible to them.

Purpose

Purpose means being directed towards some goal or solving some problem. And that problem needs to be more than just making a profit. Many AI technologies have wide applications, and many of their uses have not even been discovered yet. But this does not mean that AI should be developed without a clear goal and simply unleased into the world to see what happens.

Purpose must be central to the development of ethical AI so that the technology is developed deliberately with human benefit in mind. Designing with purpose requires honesty and transparency at all stages, which allows people to assess whether the purpose is worthwhile and achieved ethically.

The road to ethical AI

We should continue to press for AI to be developed ethically. And if technology companies are reluctant to pay careful attention to ethics, then we should call on our governments to impose sensible regulations on them.

The goal is not to hinder AI but to ensure that it operates as intended and that the benefits flow on to the greatest possible number. AI could usher in a fourth industrial revolution. It would pay for us to make this one even more beneficial and less disruptive than the past three.

As a Knowledge Partner in the Responsible AI Network, The Ethics Centre helps provide vision and discussion about the opportunity presented by AI.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Climate + Environment, Relationships, Science + Technology

From NEG to Finkel and the Paris Accord – what’s what in the energy debate

Opinion + Analysis

Science + Technology

We can raise children who think before they prompt

Big thinker

Politics + Human Rights, Science + Technology

Big Thinker: Francesca Minerva

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Science + Technology

People first: How to make our digital services work for us rather than against us

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

The ethical dilemma of the 4-day work week

The ethical dilemma of the 4-day work week

Opinion + AnalysisHealth + WellbeingBusiness + Leadership

BY The Ethics Centre 12 APR 2023

Ahead of an automation and artificial intelligence revolution, and a possible global recession, we are sizing up ways to ‘work smarter, not harder’. Could the 4-day work week be the key to helping us adapt and thrive in the future?

As the workforce plunged into a pandemic that upended our traditional work hours, workplaces and workloads, we received the collective opportunity to question the 9-5, Monday to Friday model that has driven the global economy for the past several decades.

Workers were astounded by what they’d gained back from working remotely and with more flexible hours. Not only did the care of elderly, sick or young people become easier from the home office, but also hours that were previously spent commuting shifted to more family and personal time.

This change in where we work sparked further thought about how much time we spend working. In 2022, the largest and most successful trial of a four-day working week delivered impressive results. Some 92% of 61 UK companies who participated in a two-month trial of the shorter week declared they’d be sticking with the 100:80:100 model in what the 4 Day Week director Joe Ryle called a “major breakthrough moment” for the movement.

Momentum Mental Health chief executive officer Debbie Bailey, who participated in the study, said her team had maintained productivity and increased output. But what had stirred her more deeply was a measurable “increase in work-life balance, happiness at work, sleep per night, and a reduction in stress” among staff.

However, Bailey said, the shorter working week must remain viable for her bottom line, something she ensures through a tailor-made ‘Rules of Engagement’ in her team. “For example, if we don’t maintain 100 per cent outputs, an individual or the full team can be required to return to a 5-day week pattern,” she explained.

Beyond staff satisfaction, a successful implementation of the 4-day week model could also boost the bottom line for businesses.

Reimagining a more ethical working environment, advocates say, can yield comprehensive social benefits, including balancing gender roles, elongated lifespans, increased employee well-being, improved staff recruitment and retention and a much-needed reduction in workers’ carbon footprint as Australia works towards net-zero by 2050.

University of Queensland Business School’s associate professor Remi Ayoko says working parents with a young family will benefit the most from a modified work week, with far greater leisure time away from the keyboard offering more opportunity for travel and adventure further afield, as well as increased familial bonding and life experiences along the way.

However, similar to remote work, the 4-day working week has not been without its criticisms. Workplace connectivity is one aspect that can fall by the wayside when implementing the model – a valuable culture-building part of work, according to the University of Auckland’s Helen Delaney and Loughborough University’s Catherine Casey.

Some workers reported that “the urgency and pressure was causing “heightened stress levels,” leaving them in need of the additional day off to recover from work intensity. This raises the question of whether it is ethical for a workplace to demand a more robotic and less human-focussed performance.

In November last year, Australian staff at several of Unilever’s household names, including Dove, Rexona, Surf, Omo, TRESemmé, Continental and Streets, trialed a 100:80:100 model in the workplace. Factory workers did not take part due to union agreements.

To maintain productivity, Unilever staff were advised to cut “lesser value” activities during working hours, like superfluous meetings and the use of staff collaboration tool Microsoft Teams, in order to “free up time to work on items that matter most to the people we serve, externally and internally”.

If eyebrows were raised by that instruction, they needed only look across the ditch at Unilever New Zealand, where an 18-month trial yielded impressive results. Some 80 staff took a third (34%) fewer sick days, stress levels fell by a third (33%), and issues with work-life balance tumbled by two-thirds (67%). An independent team from the University of Technology Sydney monitored the results.

Keogh Consulting CEO Margit Mansfield told ABC Perth that she would advise business leaders considering the 4-day week to first assess the existing flexibility and autonomy arrangements in place – put simply, looking into where and when your staff actually want to work – to determine the most ethically advantageous way to shake things up.

Mansfield says focussing on redesigning jobs to suit new working environments can be a far more positive experience than retrofitting old ones with new ways. It can mean changing “the whole ecosystem around whatever the reduced hours are, because it’s not just simply, well, ‘just be as productive in four days’, and ‘you’re on five if the job is so big that it just simply cannot be done’.”

New modes of working, whether in shorter weeks or remote, are also seeing the workplace grappling with a trust revolution. On the one hand, the rise of project management software like Asana is helping managers monitor deliverables and workload in an open, transparent and ethical way, while on the other, controversial tracking software installed on work computers is causing many people, already concerned about their data privacy, to consider other workplaces.

It is important to recognise that the relationship between employer and employee is not one-sided and the reciprocation of trust is essential for creating a work environment that fosters productivity, innovation and wellbeing.

While employees now anticipate flexibility to maintain a healthy work-life balance, employers also have expectations – one of which is that employees still contribute to the culture of the organisation.

When employees are engaged and motivated they are more likely to contribute to the culture of the organisation which can inform the way the business interacts with society more broadly. Trust reciprocation is not just about meeting individual needs but also working together on a common purpose. By prioritising the well-being of their employees and empowering them to contribute to the culture of the organisation a virtuous cycle is being created. Whether this is a 4-day working week or a hybrid structure is for the employer and employee to explore.

CEO of Microsoft, Satya Nadella says forming a new world working relationship based on trust between all parties can be far more powerful for a business than building parameters around workers. After all, “people come to work for other people, not because of some policy”.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Your child might die: the right to defy doctors orders

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Perils of an unforgiving workplace

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Science + Technology

Is technology destroying your workplace culture?

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Is debt learnt behaviour?

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Can philosophy help us when it comes to defining tax fairness?

Can philosophy help us when it comes to defining tax fairness?

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + LeadershipPolitics + Human Rights

BY Joshua Pearl 31 MAR 2023

Nothing is certain, except death and taxes. We can’t make the former fair but we can at least try when it comes to taxation.

Tax is fundamental to government. It is essential to fund the services we require to live in a modern society, including military, police, judiciary, roads, healthcare and education. It has also become more important in recent decades. At the time of Federation, the Australian tax system collected around 5% of GDP. Today this number stands at around 29%.

But is it fair? Are we paying too little or too much tax? Should those with greater means pay more? These are questions that must be asked of any tax system, and two works by philosophers offer very different answers.

The first is Robert Nozick’s Anarchy State and Utopia. It argues that individuals (and, by extension, the corporations they own) ought to own 100% of their income. Individual property rights are paramount, and any taxation beyond what is required to protect borders and protect these property rights is unjust. In short: only public expenditure on the police and military can be justified.

One of Nozick’s more colourful claims is that taxation is on par with forced labour. Tax forces workers to work in part for themselves, and in part for government.

But while Anarchy State and Utopia is a cult favourite of many modern-styled libertarians arguing for lower taxes, most people consider its position on tax unfair. Many find the consequences of the gross inequalities Nozick permits objectionable, while others argue a child’s right to public education, or a citizen’s right to universal healthcare, outweighs the right individuals or corporations have to their pre-tax wealth and income.