Are we idolising youth? Recommended reads

Are we idolising youth? Recommended reads

Opinion + AnalysisClimate + EnvironmentPolitics + Human Rights

BY Kym Middleton 6 JUN 2019

IQ2 Australia debates whether we need to ‘Stop Idolising Youth’ on 12 June.

Advertisers market to youth despite boomers having the strongest buying power. Unlike professions such as law and medicine, the creative industries prefer ‘digital natives’ over experience.

Young actors play mature aged characters. Yet openly teasing the young for being entitled and lazy is a popular social sport. Are the ageism insults flung both ways?

1. Why do marketers hate old people?

Ad Contrarian, Bob Hoffman / 2 December 2013

An oldie but a goodie. Bob Hoffman is the entertainingly acerbic critic of marketing and author of books like Laughing@Advertising. In this blog post he aims a crossbow at the seemingly senseless predilection of advertisers for using youth to market their products when older generations have more money and buy more stuff.

“Almost everyone you see in a car commercial is between the ages of 18 and 24,” he says. “And yet, people 75 to dead buy five times as many new cars as people 18 to 24.” He makes a solid argument.

2. It’s time to stop kvetching about ‘disengaged’ millennials

Ben Law, The Sydney Morning Herald / 27 October 2017

Ben Law asks, “Aren’t adults the ones who deserve the contempt of young people?” He argues it is older generations with influence and power who are not addressing things as big as the non-age-discriminatory climate crisis. He also shares some anecdotes about politically engaged and polite public transport riding kids.

You might regard a couple of the jokes in this piece leaning toward ageist quips but Law is also making them at his own expense. He points out millennials – the generation to which he belongs and the usual target for jokes about entitled youth – are nearing middle age.

3. Let’s end ageism

Ashton Applewhite, TED Talk / April 2017

There’s something very likeable about Ashton Applewhite – beyond her endearing name. This is even though she opens her TEDTalk with the confronting fact the one thing we all have in common is we’re always getting older. Sure, we’re not all lucky enough to get old, but we constantly age.

In pointing to this shared aspect of humanity, Applewhite makes the case against ageism. This typically TED nugget of feel good inspiration is great for every age. And if you’re anywhere between late 20s and early 70s, you’ll love the happiness bell curve. In a nutshell: it gets better!

4. Instagram’s most popular nan

Baddiewinkle, Instagram/ Helen Van Winkle

Her tagline is “stealing ur man since 1928”. Get lost in a delightful scroll through fun, colourful images from a social media personality who does not give a flying fajita for “age appropriate” dressing or demeanours. Baddie Winkle was born Helen Ruth Elam Van Winkle in Kentucky over 90 years ago.

Her internet stardom began age 85 when her great granddaughter Kennedy Lewis posted a photo of her in cut-off jeans and a tie-dye tee. Now Winkle’s granddaughter Dawn Lewis manages her profile and bookings. Her 3.8 million followers show us audiences aren’t only interested young social media influencers. “They want to be me when they get older,” Winkle says. Damn right we do.

Event info

IQ2 Australia makes public debate smart, civil and fun. On 12 June two teams will argue for and against the statement, ‘Stop Idolising Youth’. Ad writer Jane Caro and mature aged model Fred Douglas take on TV writer Ben Jenkins and author Nayuka Gorrie. Tickets here.

MOST POPULAR

BY Kym Middleton

Former Head of Editorial & Events at TEC, Kym Middleton is a freelance writer, artistic producer, and multi award winning journalist with a background in long form TV, breaking news and digital documentary. Twitter @kymmidd

What I now know about the ethics of fucking up

What I now know about the ethics of fucking up

Opinion + AnalysisRelationships

BY Alison Hill 28 MAY 2019

We’ve all fucked up before. Big mistakes and small, regrettable misdemeanours.

I have a penchant for saying things that are funny inside my head but come out all wrong. I know I’ve unintentionally offended and hurt people by blurting out the first thing that comes to mind. If I’ve become aware of it, I’ve tried to make amends. But it’s never been big, public or career ending. So, being honest, part of my interest in going along to ‘The Ethics of Fucking Up’ was schadenfreude.

I wanted to hear how Sam Dastyari and Mel Greig, who shared their stories of the ‘Chinese political donor scandal’ and the ‘Royal prank call’ had stuffed up. In truth, I wanted to revel in it just a little, to tell myself that at least it had never been that bad for me. I wanted to identify with Paul McDermott, whose fuck ups had never made the front pages or ruined lives.

I watched the crowd enter the sold-out venue in inner Sydney, thinking that every single one of these people who looked so smart, privileged and self-possessed had done at least one monumentally stupid thing in their lives. Had they come looking for redemption? For confirmation that what they did was okay? Because we all fuck up, whether we’re being naïve and thoughtless or doing something dastardly.

Pizza, wine and dark confessions

So what did I take away from a night that was variously funny, intelligent, shocking and sad, with pizza and wine thrown in for good measure?

It seems the biggest fuck ups come about when there is a combination two things: individuals being encouraged to act without first thinking through their decisions, and institutions not living by an ethical framework – or not having one at all. Add to that the speed at which we act in the tech era and it’s no wonder we’ve hurtled into our present state.

As Sam described it, ‘We’re heading backwards with our morality, with our acceptance and empathy for others, with our responsibility for the planet, while fear, selfishness and xenophobia are controlling our political decisions’.

So despite not being able to condone what he did in the ‘Chinese political donor scandal’, my heart ached for him when he described how, in the midst of the scandal, he lay in bed at 3am alone with his thoughts, realising he was solely responsible for the mess.

Rethinking forgiveness

Nobody deserves this unless they have committed some monstrous crime. I decided that I will accept mea culpas and requests for forgiveness more graciously, in my personal life and by public figures. When somebody shows true remorse, I’ll forgive them, because I’m more aware how we all fuck up from time to time, in big and small ways. It’s only human.

We love to hold individuals to account, especially when they are public figures. Perhaps we should be harder on institutions. Mel Greig told us how the broadcast organisation’s processes and ethical judgements went unquestioned during the ‘Royal prank call’.

To recap: the call to the London hospital caring for the Duchess of Cambridge ended in the suicide of nurse Jacintha Saldanha, who fell for the joke thinking it was the Queen and Prince Charles. A chain of decisions meant the prank call was broadcast in full – although Mel tried to stop this happening.

Yet Mel had to wear all the blame. Her description of the trolling she endured afterwards, which included death threats, made the room go quiet. Tears shone in the eyes of the person next to me. Public shaming, relentlessly negative and disparaging media coverage and the non-stop blast of social media are damaging people like never before. At no time has it been easier to broadcast judgment on individuals, instantly and loudly. But institutions are never made to suffer in the same way. Think banking royal commission.

How would I survive if this happened to me, I wondered?

A call to arms against the trolls

Would I be brave and resilient like Mel, and use the horrible experience to start a conversation to help other people, as she did by starting Troll Free Day? Would I have been strong enough to front up to the inquest into nurse Jacintha Saldanha’s death, look her children in the eye and say sorry? Would I stop looking for scapegoats and accept blame, as Sam did, learning to live with what he called ‘the darkest shit in the world’?

As always, a discussion about ethics goes on long after the lights have been turned off. Listening to this conversation about the ethics of fucking up has encouraged me to start conversations about it with friends and family. I realised we all draw the line about what we will and won’t forgive somewhere different, one of the things that defines our personal ethics.

The crowd drifted into the street to the sounds of Paul Kelly’s I’ve Done All the Dumb Things and Cher’s If I Could Turn Back Time. Neither has ever been on my playlist, but I heard them in a new way. Opening your ears to things you think you already know is good thing.

I’ll certainly go back for The Ethics Centre’s conversations on desire, lying, courage and nudity.

MOST POPULAR

Are we prepared for climate change and the next migrant crisis?

Are we prepared for climate change and the next migrant crisis?

Opinion + AnalysisClimate + EnvironmentPolitics + Human Rights

BY Kate Prendergast 7 MAY 2019

A powerful infographic published in 2014, predicted how many years it would take for a world city to drown.

It used data from NASA, Sea Level Explorer, and the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Venice will be the first to go under apparently, its canals rising to wetly throttle the city of love. Amsterdam is set to follow, Hamburg next.

Other tools play out the encroachment of rising tides on our coasts. This one developed by EarthTime shows Sydney airport as a large puddle if temperatures increase by four degrees. There’s also research suggesting our ancestors may one day look down to see fish nibbling on the Opera House sails.

Climate change refugees will become reality

Sea level rise is just one effect of anthropogenic climate change that would make a place uninhabitable or inhospitable to humankind. It’s also relatively slow. Populations in climate vulnerable hotspots face a slew of other shove factors, too.

Already, we are seeing a rising frequency of extreme weather events. Climate change was linked to increasingly destructive tropical cyclones in a report published in Nature last year, and Australia’s Climate Council attributed the same to earlier and more dangerous fire seasons. Rapidly changing ecosystems will impact water resources, crop productivity, and patterns of familiar and unfamiliar disease. Famine, drought, poverty and illness are the horsemen saddling up.

Some will die as a result of these events. Others, if they are able, will choose to stay. The far sighted and privileged may pre-empt them, relocating in advance of crisis or discomfort.

These migrants can be expected to move through the ‘correct’ channels, under the radar of nativist suspicion. (‘When is an immigrant not an immigrant?’ asks Afua Hirsch. ‘When they’re rich’.)

But many more will become displaced peoples, forcibly de-homed. Research estimates this number could be anywhere between 50 million and 1 billion in the 21st century. This will prompt new waves of interstate and international flows, and a resultant redistribution and intensification of pressures and tensions on the global map.

How will the world respond?

Where will they go? What is the ethical obligation of states to welcome and provide for them? With gross denialism characterising global policies towards climate change, and intensifying hostility locking down national borders, how prepared are we to contend with this challenge to come?

“You can’t wall them out,” Obama recently told the BBC. “Not for long.”

While interstate climate migration (which may already be occurring in Tasmania) will incur infrastructural and cultural problems, international migration is a whole and humongous other ethical conundrum. Not least because currently, climate change migrants have almost no legal protections.

Is a person who moves because of a sudden, town levelling cyclone more entitled to the status of climate migrant or refugee (and the protection it affords) than someone who migrates as a result of the slow onset attrition of their livelihood due to climate change?

Who makes the rules?

Does sudden, violent circumstance carry a greater ethical demand for hospitality than if, after many years of struggle, a Mexican farmer can no longer put food on the table because his land has turned to dust? Does the latter qualify as a climate or economic migrant, or both?

Somewhat ironically (and certainly depressingly), the movement of people to climate ‘havens’ will place stress on those environmental sanctuaries themselves, potentially leading to concentrated degradation, pollution and threat to non-human nature. (On the other hand, climate migration could allow for nature to reclaim the places these migrants have left.)

There is also the argument that, once migrants from developing countries have been integrated into a host country, their carbon footprint will increase to resemble that of their new fellow citizenry – resulting in larger CO2 emissions. From this perspective, put forward by Philip Cafaro and Winthrop Staples, it is in the interests of the planet for prosperous countries to limit their welcome.

Not that privileged populations need much convincing. Jealous fear of future scarcity, a globalisation inflamed resentment towards the Other, a sense that modernity has failed to deliver on its promise of wholesale bounty: all these are conspiring to create increasingly tribalised societies that enable the xenophobic agendas of their governments. A recent poll showed that 46 percent of Australians believe immigration should be reduced, a percentage consistent with attitudes worldwide.

A divided world

In the US, there’s Trump’s grand ‘us vs them’ symbol of a wall. As reported in the Times, German lawmakers are comparing refugees to wolves. In Italy, tilting towards populism and the right, a mayor was arrested after transforming his small town into a migrant sanctuary.

Closer to home, in a country where the 27 years without recession could be linked to immigration, there’s Scott Morrison’s newly proposed immigration cuts. There’s Senator Anning blaming the Christchurch massacre on Muslim immigration. There’s the bipartisan support for the prospects, wellbeing and mental health of asylum seekers to deteriorate to such an extent, the UN human rights council described it as ‘massive abuse’.

Yet the local effects of climate change don’t have a local origin. Causality extends beyond borders, piling miles high at the feet of industrialised countries. Nations like the US and Australia enjoy high standards of living largely because we have been pillaging and burning fossil fuels for more than a century. Yet those least culpable will bear the heaviest cost.

This, argues the author of a paper published in Ethics, Policy and Environment, warrants a different ethical framework than that which applies to other kinds of migration. He concludes that industrialised nations “have a moral responsibility … to compensate for harms that their actions have caused”.

This responsibility may include investing in less developed countries to mitigate climate change effects, writes the author. But it also morally obliges giving access, security and residence to those with nowhere else to go.

MOST POPULAR

BY Kate Prendergast

Kate Prendergast is a writer, reviewer and artist based in Sydney. She's worked at the Festival of Dangerous Ideas, Broad Encounters and Giramondo Publishing. She's not terrible at marketing, but it makes her think of a famous bit by standup legend Bill Hicks.

Australia, it’s time to curb immigration

Australia, it’s time to curb immigration

Opinion + AnalysisClimate + EnvironmentPolitics + Human Rights

BY Satya Marar 3 MAY 2019

A majority of Australians welcome immigrants. So why then do opinion polls of young and old voters alike across the political divide, now find majority support for reducing our immigration intake?

Perhaps it could be for the same reason that faith in our political system is dwindling at a time of strong economic growth. Australia is the ‘lucky country’ that hasn’t had a recession in the last 28 years.

Yet we’ve actually had two recessions in this time if we consider GDP on a per-capita basis. This, combined with stagnant real wage growth and sharp increases in congestion and the price of housing and electricity in our major cities, could explain why the Australian success story is inconsistent with the lived experience of so many of us.

The decline of the Australian dream?

Our current intake means immigration now acts as a ponzi scheme.

The superficial figure of a growing headline GDP fuelled by an increasing population masks the reality of an Australian dream that is becoming increasingly out of reach for immigrants and native-born Australians alike.

We’ve been falsely told we’ve weathered economic calamities that have stunned the rest of the world. When taken on a per-capita basis, our economy has actually experienced negative growth periods that closely mirror patterns in the United States.

We’re rightly told we need hardworking immigrants to help foot the bill for our ageing population by raising productivity and tax revenue. Yet this cost is also offset when their ageing family members or other dependents are brought over. Since preventing them from doing so may be cruel, surely it’s fairer to lessen our dependence on their intake if we can?

A lack of infrastructure

Over 200,000 people settle in Australia every year, mostly in the major cities of Sydney and Melbourne. That’s the equivalent of one Canberra or greater Newcastle area a year.

Unlike the United States, most economic opportunities are concentrated in a few major cities dotting our shores. This combined with the failures of successive state and federal governments to build the infrastructure and invest in the services needed to cater for record population growth levels driven majorly by immigration.

A failure to rezone for an appropriate supply of land, mean our schools are becoming crowded, our real estate prohibitively expensive, our commutes are longer and more depressing, and our roads are badly congested.

Today, infrastructure is being built, land is finally being rezoned to accommodate higher population density and more housing stock in the outer suburbs, and the Prime Minister has made regional job growth one of his major priorities.

But these issues should have been fixed ten years ago and it’s increasingly unlikely that they will be executed efficiently and effectively enough to catch up to where they need to be should current immigration intake levels continue for the years to come.

Our governments have proven to be terrible central planners, often rejecting or watering down the advice of independent expert bodies like Infrastructure Australia and the Productivity Commission due to political factors.

Why would we trust them to not only get the answer right now, but to execute it correctly? Our newspapers are filled daily with stories about light rail and road link projects that are behind schedule.

All of it paid for by taxpayers like us.

Foreign workers or local graduates?

Consider also the perverse reality of foreign workers brought to our shores to fill supposed skill gaps who then struggle to find work in their field and end up in whatever job they can get.

Meanwhile, you’ll find two separate articles in the same week. One from industry groups cautioning against cutting skilled immigration due to shortages in the STEM fields. The other reporting that Australian STEM graduates are struggling to find work in their field.

Why would employers invest resources in training local graduates when there’s a ready supply of experienced foreign workers? What incentive do universities have to step in and fill this gap when their funding isn’t contingent on employability outcomes?

This isn’t about nativism. The immigrants coming here certainly have a stake in making sure their current or future children can find meaningful work and obtain education and training to make them job ready.

There’s only one way to hold our governments accountable so the correct and sometimes tough decisions needed to sustain our way of life and make the most of the boon that immigration has been for the country, are made. It’s to wean them off their addiction to record immigration levels.

Lest the ponzi scheme collapse.

And frank conversations about the quantity and quality of immigration that the sensible centre of politics once held, increasingly become the purview of populist minor parties who have experienced resurgence on the back of widespread, unanswered frustrations about unsustainable immigration that we are ill-prepared for.

This article was produced in association with IQ2: Should Australia curb immigration? With powerful arguments presented at both ends of the spectrum, it was a debate that raised issues from urban planning to government policy, environmental impacts to economic advantages and more.

MOST POPULAR

BY Satya Marar

Satya Marar is an Indian-born, Sydney based writer, public commentator and Director of Policy at the Australian Taxpayers’ Alliance. He took part in the IQ2 debate, ‘Curb Immigration’

Where do ethics and politics meet?

Where do ethics and politics meet?

Opinion + AnalysisPolitics + Human Rights

BY The Ethics Centre 26 APR 2019

In the Western philosophical tradition, ethics and politics were frequently deemed to be two sides of a single coin.

Aristotle’s Ethics sought to answer the question of what is a good life for an individual person. His Politics considered what is a good life for a community (a polis). So, for the Ancient Greeks, at least, the good life existed on an unbroken continuum ranging from the personal through the familial to the social.

In some senses, this reflected an older belief that individuals exist as part of society. Indeed, in many cultures – in the Ancient world and today – the idea of an isolated individual makes little sense. Yet, there are a few key moments in Western philosophy when we see the individual emerging.

St Thomas Aquinas argued that no individual or institution has ‘sovereignty’ over the well-informed conscience of the individual.

René Descartes placed the self-certain subject at the centre of all knowledge and in doing so undermined the authority of institutions that based their claims to superiority on revelation, tradition or hierarchy. Reason was to take centre stage.

Aquinas and Descartes, along with many others, helped set the foundation for a modern form of politics in which the conscientious judgement of the individual takes precedence over that of the community.

Today, we observe a global political landscape in which ethics can be hard to detect. It’s easy to say that many politicians are ruled by naked greed, fear, opinion polls, blind ideology or a lust for power.

This probably isn’t fair to the many politicians who apply themselves to their responsibilities with care and diligence.

In the end, ethics is about living an examined life – something that should apply whether the choices to be made are those of an individual, a group or a whole society.

MOST POPULAR

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

What is the definition of Free Will ethics?

What is the definition of Free Will ethics?

Opinion + AnalysisRelationships

BY The Ethics Centre 16 APR 2019

Free Will describes our capacity to make choices that are genuinely our own. With free will comes moral responsibility – our ownership of our good and bad deeds.

That ownership indicates that if we make a choice that is good, we deserve the resulting rewards. If in turn we make a choice that is bad, we probably deserve those consequences as well. In the case of a really bad choice, such as committing murder, we may have to accept severe punishment.

The link between free will and responsibility has both theological and philosophical roots.

Within theology, for example, the claim that humans are ‘made in the image of God’ (a central tenet of major religions like Judaism, Christianity and Islam) is not that they are the physical image of their creator.

Rather, the claim is made that humans are made in the ‘moral image’ of God – which is to say that they are endowed with the ‘divine’ capacity to exercise free will.

Of course, the experience of free will is not limited to those who hold a religious belief. Philosophers also argue that it would be unjust to blame someone for a choice over which they have no control.

Determinism is the belief that all choices are determined by an unbroken chain of cause and effect. Those who believe in ‘determinism’ oppose free will, arguing that that the belief that we are the authors of our own actions is a delusion.

Whereas scientific evidence has found there is brain activity prior to the sensation of having made a choice, we’re unable to resolve the question of which account is correct.

Should that gap close – and free will be proven to be an illusion, then the basis for ascribing guilt to those who act unethically (including criminals) will also be destroyed.

How could we justify punishing a person who claims that they had no choice but to do evil?

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Climate + Environment, Relationships, Science + Technology

From NEG to Finkel and the Paris Accord – what’s what in the energy debate

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Paralympian pay vs. Olympian pay

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

Joker broke the key rule of comic book movies: it made the audience think

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

It takes a village to raise resilience

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Why ethics matters for autonomous cars

Why ethics matters for autonomous cars

Opinion + AnalysisScience + Technology

BY The Ethics Centre 14 APR 2019

Whether a car is driven by a human or a machine, the choices to be made may have fatal consequences for people using the vehicle or others who are within its reach.

A self-driving car must play dual roles – that of the driver and of the vehicle. As such, there is a ‘de-coupling’ of the factors of responsibility that would normally link a human actor to the actions of a machine under his or her control. That is decision to act and the action itself are both carried out by the vehicle.

Autonomous systems are designed to make choices without regard to the personal preferences of human beings, those who would normally exercise control over decision-making.

Given this, people are naturally invested in understanding how their best interests will be assessed by such a machine (or at least the algorithms that shape – if not determine – its behaviour).

In-built ethics from the ground up

There is a growing demand that the designers, manufacturers and marketers of autonomous vehicles embed ethics into the core design – and then ensure that they are not weakened or neutralised by subsequent owners.

We can accept that humans make stupid decisions all the time, but, we hold autonomous systems to a higher standard.

This is easier said than done – especially when one understands that autonomous vehicles are unlikely ever to be entirely self-sufficient. For example, autonomous vehicles will often be integrated into a network (e.g. geospatial positioning systems) that complements their integrated, onboard systems.

A complicated problem

This will exacerbate the difficulty of assigning responsibility in an already complex network of interdependencies.

If there is a failure, will the fault lie with the designer of the hardware, or the software, or the system architecture…or some combination of these and others? What standard of care will count as being sufficient when the actions of each part affects the others and the whole?

This suggests that each design element needs to be informed by the same ethical principles – so as to ensure as much ethical integrity as possible. There is also a need to ensure that human beings are not reduced to the status of being mere ‘network’ elements.

What we mean by this is to ensure the complexity of human interests are not simply weighed in the balance by an expert system that can never really feel the moral weight of the decisions it must make.

For more insights on ethical technology, make sure you download our ‘Ethical by Design‘ guide where we take a detailed look at the principles companies need to consider when designing ethical technology.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Science + Technology

The new rules of ethical design in tech

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Science + Technology

With great power comes great responsibility – but will tech companies accept it?

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships, Science + Technology, Society + Culture

Who does work make you? Severance and the etiquette of labour

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Science + Technology

Who’s to blame for Facebook’s news ban?

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

The Ethics of In Vitro Fertilization (IVF)

The Ethics of In Vitro Fertilization (IVF)

Opinion + AnalysisScience + Technology

BY The Ethics Centre 8 APR 2019

To understand the ethics of IVF (In vitro fertilisation) we must first consider the ethical status of an embryo.

This is because there is an important distinction to be made between when a ‘human life’ begins and when a ‘person’ begins.

The former (‘human life’) is a biological question – and our best understanding is that human life begins when the human egg is fertilised by sperm or otherwise stimulated to cause cell division to begin.

The latter is an ethical question – as the concept of ‘person’ relates to a being capable of bearing the full range of moral rights and responsibilities.

There are a range of other ethical issues IVF gives rise to:

- the quality of consent obtained from the parties

- the motivation of the parents

- the uses and implications of pre-implantation genetic diagnosis

- the permissibility of sex-selection (or the choice of embryos for other traits)

- the storage and fate of surplus embryos.

For most of human history, it was held that a human only became a person after birth. Then, as the science of embryology advanced, it was argued that personhood arose at the moment of conception – a view that made sense given the knowledge of the time.

However, more recent advances in embryology have shown that there is a period (of up to about 14 days after conception) during which it is impossible to ascribe identity to an embryo as the cells lack differentiation.

Given this, even the most conservative ethical position (such as those grounded in religious conviction) should not disallow the creation of an embryo (and even its possible destruction if surplus to the parents’ needs) within the first 14 day window.

Let’s further explore the grounds of some more common objections. Some people object to the artificial creation of a life that would not be possible if left entirely to nature. Or they might object on the grounds that ‘natural selection’ should be left to do its work. Others object to conception being placed in the hands of mortals (rather than left to God or some other supernatural being).

When covering these objection it’s important to draw attention existing moral values and principles. For example, human beings regularly intervene with natural causes – especially in the realm of medicine – by performing surgery, administering pharmaceuticals and applying other medical technologies.

A critic of IVF would therefore need to demonstrate why all other cases of intervention should be allowed – but not this.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Science + Technology

License to misbehave: The ethics of virtual gaming

Opinion + Analysis

Science + Technology

The cost of curiosity: On the ethics of innovation

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Science + Technology

Is technology destroying your workplace culture?

Reports

Science + Technology

Ethical by Design: Principles for Good Technology

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Increase or reduce immigration? Recommended reads

Increase or reduce immigration? Recommended reads

Opinion + AnalysisClimate + EnvironmentPolitics + Human Rights

BY Kym Middleton 21 MAR 2019

Immigration is the hot election issue connecting everything from mismanaged water and mass fish deaths in the Murray Darling to congested cities and unaffordable housing.

The 2019 IQ2 season kicks off with ‘Curb Immigration’ on 26 March. It’s something Prime Minister Scott Morrison promised to do today if re-elected and opposition leader Bill Shorten has committed to considering.

Here’s a collection of ideas, research, articles and arguments covering the debate.

New migrants to go regional for permanent residency, under PM’s plan

Scott Morrison, SBS News / 20 March 2019

Prime Minister Scott Morrison revealed his immigration plan today. He confirmed reports he will lower the cap on Australia’s immigration intake from 190,000 to 160,000 for the next four years. He announced 23,000 visa places that require people to live and work in regional Australia for three years before they can apply for permanent residency. “It is about incentives to get people taking up the opportunities outside our big cities” and “it’s about busting congestion in our cities”, Morrison said.

————

Australian attitudes to immigration: a love / hate relationship

The Ethics Centre, The New Daily / 24 January 2019

You’ll hear Australians talk about our country as either a multicultural utopia or intolerant mess. This article charts many recent surveys on our attitudes to immigration. The results show almost equal majorities of us love and hate it for different reasons, suggesting individual people both support and reject immigration at the same time. We’re complex creatures.

————

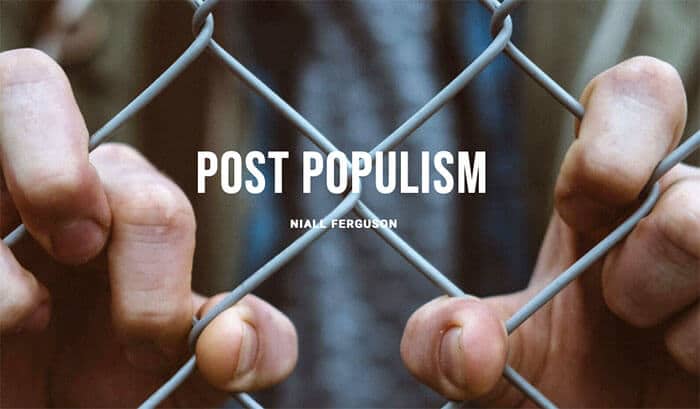

Post Populism

Niall Ferguson, Festival of Dangerous Ideas / 4 November 2018

At the Festival of Dangerous Ideas on Cockatoo Island, Niall Ferguson presented his take on the five ingredients that have bred the nationalistic populism sweeping the western world today. Point one: increased immigration. Listen to the podcast or watch the video highlights. Elsewhere, Ferguson points to Brexit and the European migrant crisis and predicts, “the issue of migration will be seen by future historians as the fatal solvent of the EU”.

————

Human Flow movie

Ai Weiwei / 2017

Part documentary and part advocacy, Human Flow is a film by Chinese artist Ai Weiwei that “gives a powerful visual expression” to the 65 million people displaced from their homes by climate change, war or famine. It is not the story of ‘orderly migration’ based on skilled visas or spatial planning policies, but rather, one of mass flows across countries and continents.

————

Government needs to wake up to impact of population boom

PM, ABC RN / 23 February 2018

IQ2 guest and human geographer Dr Jonathan Sobels is interviewed by Linda Mottram on the impact of Australia’s population growth on the continent’s natural environment. He’s not the only person concerned about this. A 2019 study by ANU found 75 percent of Australians agree the environment is already under too much pressure with the current population size.

————

Counter-terrorism expert Anne Aly: ‘I dream of a future in which I’m no longer needed’

Greg Callaghan, The Sydney Morning Herald / 18 November 2016

Dr Anne Aly is a counter terrorism expert come politician with “instant relatability”, according to this feature piece on her. Get to know more about her interesting life and career before catching her at IQ2 where she’ll argue against the motion ‘Curb Immigration’. Aly is the Labor Member for the West Australian electorate of Cowan and first female Muslim parliamentarian in Australia.

————

Event info

Get your IQ2 ‘Curb Immigration’ tickets here

Satya Marar & Jinathan Sobels vs Anne Aly & Nicole Gurran

27 March 2019 | Sydney Town Hall

MOST POPULAR

BY Kym Middleton

Former Head of Editorial & Events at TEC, Kym Middleton is a freelance writer, artistic producer, and multi award winning journalist with a background in long form TV, breaking news and digital documentary. Twitter @kymmidd

6 Things you might like to know about the rich

6 Things you might like to know about the rich

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + Leadership

BY The Ethics Centre ethics 29 NOV 2018

In Australia, where we like to cut our tall poppies down, wealthy people come with an unenviable reputation.

Unless you happen to be reading the business pages, money and power will attract sneering. Otherwise, the lionising coverage of those with outrageous success seems ample reward for their riches.

A multitude of psychological studies conclude rich people are more unethical and selfish than those who are less fortunate. However, one question remains mostly unanswered; what came first; the bad character or the money?

Here, we take a quick look at what research tells us about the collision of money and ethics:

1. Fancy car, poor driving

People driving expensive cars are four times more likely to ignore right of way laws on the road than those who drive cheap cars.

Dacher Keltner, a psychologist at the University of California at Berkeley

and his then-graduate student, Paul Piff, tracked the model of every car that cut off others.

“It told us that there’s something about wealth and privilege that makes you feel like you’re above the law, which allows you to treat others like they don’t exist,” Keltner told the Washington Post.

In another experiment, half of the luxury car drivers ignored a pedestrian on a crossing – many even after making eye contact. However, all the cheapest cars stopped.

2. They cheat more on their taxes

Taxpayers whose true income was between $US500,000 and $1 million a year understated their adjusted gross incomes by 21 per cent in 2001, compared to an eight percent underreporting rate for those earning $50,000 to $100,000 and even lower rates for those earning less than that.

According to research, wealthier people were more likely to cheat because it was easier for them to hide sources of income from self-employment, rents, capital gains and partnerships.

3. Less empathetic

Observations that rich people tend to be less generous than the poor may be influenced by the amount of time we spend looking at each other.

By analysing what people look at as they walk down a street (wearing Google Glasses), psychologists at the University of California, Berkeley,

Pia Dietze and Eric Knowles, discovered that social class did not affect how many times people looked at another person – but it did determine how much time they spend looking.

Participants self-nominating as higher in social class spent less time looking at other people.

Dacher Keltner says people in lower socioeconomic classes tend to be more vigilant because they “live lives defined by threat”.

4. Less generous

Middle-class Americans give a far bigger share of their discretionary income to charities than the rich. If the rich live in wealthy neighbourhoods, they give an even smaller share of their income than wealthy people in economically-diverse neighbourhoods.

“Wealth seems to buffer people from attending to the needs of others,” Paul Piff told the New York Times.

5. Cashed-up and sad = bad

People most likely to approve of unethical behaviour are those with a low level of happiness, but a high level of income, according to a survey of 27,672 professionals.

Conversely, the most disapproving of unethical behaviour were those with high income and life satisfaction, according to professor of management and organisations at the Kellogg School, the late Keith Murnighan, and Long Wang of the City University of Hong Kong.

“People who are exuberant and upbeat about life, and happen to have high income, are likely to be more trustworthy,” Murnighan told his university’s Kellogg Insight publication.

“An unhappy rich person might feel bad because of their own unethical behaviour, but it might be that very behaviour that got them rich in the first place.

“Having a comfortable amount of money might allow enough psychological ‘room’ to ethically consider the needs and perspectives of other people, which may then lead to feelings of well-being.”

6. Stereotypes are self-fulfilling

Negative stereotypes of rich people are all-pervasive. According to Adam Waytz, an Associate Professor of Management and Organisations at Northwestern University’s Kellogg School of Management, studies show that the more profitable a company, the more people linked it to social harm.

“People come to confirm the behaviours that are expected of them (we live up to and down to others’ stereotypes of us), and if rich people and business folks are assumed to behave with the same scruples as Bernie Madoff, these views will likely elicit unethical behaviour from them,” warns Waytz in a blog in the Scientific American.

This article was originally written for The Ethics Alliance. Find out more about this corporate membership program. Already a member? Log in to the membership portal for more content and tools here.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Moral injury is a new test for employers

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights

Do diversity initiatives undermine merit?

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships

The pivot: Mopping up after a boss from hell

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership