He said, she said: Investigating the Christian Porter Case

He said, she said: Investigating the Christian Porter Case

Opinion + AnalysisPolitics + Human Rights

BY Louise Richardson-Self 10 MAR 2021

On 4 March 2021 Attorney General Christian Porter identified himself as the unnamed Minister who had been accused of a 1988 rape in a letter sent to the Prime Minister and some senators.

He strenuously denies any wrongdoing and has refused to step down from his role.

ABC News reports that ‘the letter urges the Prime Minister to set up an independent parliamentary investigation into the matter’ — but should there be an investigation?

The Problem With Testimony

When it comes to accusations of sexual assault, it seems like the situation comes down to a clash of ‘testimony’ — she said, he said. But who is to be believed?

Testimony, to clarify, isn’t just any old speech act. Testimony is speech that is used as a declaration in support of a fact. “The sky is blue” is testimony; “I like strawberries” isn’t.

Generally, people are hesitant to accept testimony as good, or strong evidence for any sort of claim. This is not because testimony is always unreliable, but because we think that there are more reliable methods of attaining knowledge.

Other methods include direct experience (living through or witnessing something), material collection (looking for evidence to support the truth of a claim), or through the exercise of reason itself (for instance, by way of logic or deductive reasoning).

In this case, it seems like what would need to occur is a fact-finding mission which could add weight either to the testimony of either Porter or the alleged victim.

What is very surprising, then, is that only some people support such an investigation, while others have rejected the move as unnecessary, including Prime Minister Scott Morrison. These people deem Porter’s testimony credible. But should they?

Judging Credibility

It isn’t strange to find that people are willing to treat testimony as sufficient evidence for a claim. We often do. Testimony is used in trials. Every news report is testimony. The scientific truths we have learn from books or YouTube are testimony. You get the picture. We may think we are always sceptical of testimony, but we could hardly get by without it.

So, we do rely on testimony. Just not all testimony. When it comes to believing testimony, what we’re really doing is judging the speaker’s credibility. The question is thus: should we trust what a specific person says about a specific matter in a specific context?

The problem is that we’re actually not very good at working out which speakers are credible and which aren’t. Often we get it wrong. And sometimes we get it wrong because of implicit biases—biases about types of people, biases about institutions, and the sway of authority.

As philosopher Miranda Fricker has pointed out, when people do not receive the credibility they are due—whether because they receive too much (a credibility excess) or too little (a credibility deficit)—and the reason they do not receive it is because of such biases, then a testimonial injustice occurs.

“Being judged credible to some degree is being regarded as more credible than others, less credible than others, and equally credible as others,” explains philosopher José Medina.

In a she said, he said case, if we judge one person as credible, we’re also discrediting the other.

Fricker explains that testimonial injustice produces harms. First, there is a harm caused to the listener: because they didn’t believe testimony they should have, they failed to acquire some new knowledge, which is a kind of harm.

However, testimonial injustices also harms the speaker. When someone’s testimony is doubted without good reason, we disrespect them by doubting their ability to convey truth – which is part of what defines us as humans. This means testimonial injustices symbolically degrade us qua [as] human. Basically, to commit a testimonial injustice means we fail to treat people in a fundamentally respectful way. Instead, we treat them as less than fully human.

Is there a Credibility Deficit or Excess in Porter’s case?

Relevant to the issue of credibility attribution in the wake of a sexual assault allegations is the perception (and fear) shared by many that women lie about sexual assault.

In fact, approximately 95% of sexual assault allegations are true. This means it is highly improbable (but not impossible) that the alleged victim made a false claim.

It is not just stereotyping about lying and vindictive women that can interfere with correct credibility attribution. As Treasurer Josh Frydenberg has reminded us, Porter “is entitled to the presumption of innocence, as any citizen in this country is entitled.”

This commitment we share to presume innocence unless or until guilt is proven is a significant bulwark of our ethico-legal value system.

However, in a case of “she said, he said”, his entitlement to the presumption of innocence automatically generates the assumption that the victim is lying. Given that false rape allegations are so infrequent, the presumption of innocence unfairly undermines the credibility of the complainant almost every time.

This type of testimonial injustice may seem unavoidable because we cannot give up the presumption of innocence; it is too important. However, the insistence that Porter receive the presumption of innocence rather than insisting we believe the statistically likely allegations against him may point to another problem with the way assign credibility.

As philosopher Kate Manne has observed, particularly when it comes to allegations made by women of sexual assault by men, the accused are often received with himpathy—that is, they receive a greater outpouring of sympathy and concern over the complainants. She explains, “if someone sympathizes with the [accused] initially…he will come to figure as the victim of the story. And a victim narrative needs a villain…”

So here’s the rub.

If a great many people in a society share the view that women lie, then they tacitly see complainants as uncredible.

And if a great many people in a society feel sorry for certain men who are accused of sexual assault, then they are likely to side with the accused. In turn, those who are accused of sexual assault (usually, men) will automatically receive a credibility excess.

Is this what has happened in Porter’s case? Note that an investigation could lend credibility to either party’s claims. This is where the police would normally step in.

Didn’t the Police Investigate and Exonerate Porter?

You would be forgiven for thinking that NSW Police had conducted a thorough investigation and had cleared Porter’s name judging by the way some powerful parliamentary figures have responded to Porter’s case.

For example, in his dismissal of calls for an independent investigation, Scott Morrison said that it “would say the rule of law and our police are not competent to deal with these issues.” Likewise, Treasurer Josh Frydenberg said: “The police are the only body that are authorised to deal with such serious criminal matters.” Nationals Senator Susan MacDonald also opposed the investigation, saying: “We have a system of justice in this country [and] a police service that is well resourced and the most capable of understanding whether or not evidence needs to go to trial — and they have closed the matter.”

Case closed. This must mean that there’s no evidence and that an independent inquiry would be pointless, right?

Not quite. NSW Police stated that there was “insufficient admissible evidence” to proceed with an investigation. They did not say that there was no evidence of misconduct. Moreover, the issue for criminal proceedings is that the alleged victim did not make a formal statement before she took her own life.

In other words, the complainant’s testimony does not get to count as evidence because, technically, there is no testimony on the record.

Preventing Testimonial Injustice

Since the alleged victim had not made a formal statement to Police at the time of her death, the call for an investigation into Porter’s conduct can be seen as a means of ensuring Porter does not receive a testimonial credibility excess and the complainant a testimonial credibility deficit.

To stand by Porter’s testimony in a context where it is widely – and falsely – believed that women make false rape allegations, and where the police are seen as the only body capable of exercising an investigation (when in fact they are not), would be to commit a testimonial injustice.

As former Liberal staffer and lawyer Dhanya Mani says, “The fact that the police are not pursuing the matter for practical reasons does not preclude or prevent the Prime Minister from undertaking an inquiry into a very serious allegation… And that inquiry will either exonerate Christian Porter and prove his innocence or it will prove otherwise.”

It is important to understand that an independent investigation is not bound by the exact same evidentiary rules as are the police and courts. It may be possible for others to testify on her behalf. Other evidence which is inadmissible in court may be admissible here. An independent investigation at least offers the possibility that the complainant’s testimony will get a fair hearing.

Also worth noting is where the presumption of innocence would end. For a crime, guilt should be proved beyond a reasonable doubt. For civil cases, that standard is “on the balance of probabilities”. What standard should an independent investigation use? I would suggest the latter, precisely because testimony is likely to be all the evidence there is.

To prevent a testimonial injustice—attributing too much credibility, or too little, to someone undeserving of it—these allegations must be investigated.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture, Politics + Human Rights

Taking the cynicism out of criticism: Why media needs real critique

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

Why certain things shouldn’t be “owned”

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

If you don’t like politicians appealing to voters’ more base emotions, there is something you can do about it

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

Hey liberals, do you like this hegemony of ours? Then you’d better damn well act like it

BY Louise Richardson-Self

Louise Richardson-Self is a Lecturer in Philosophy and Gender Studies at the University of Tasmania and an Australian Research Council Discovery Early Career Researcher Awardee (2019). Her current research focuses are the problem online hate speech, and the tension between LGBT+ non-discrimination and religious freedom. She is the author of Justifying Same-Sex Marriage: A Philosophical Investigation (2015) and her second book, Hate Speech Against Women Online: Concepts and Countermeasures is due for publication in 2021.

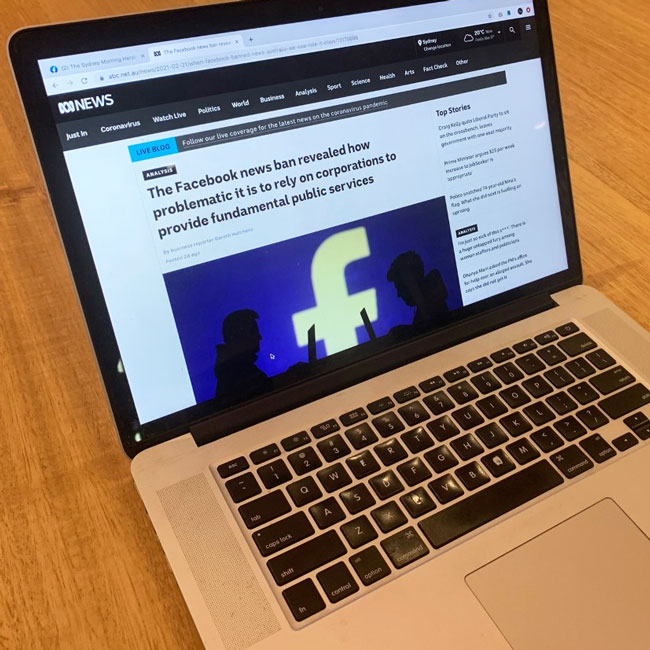

Who's to blame for Facebook’s news ban?

Who’s to blame for Facebook’s news ban?

Opinion + AnalysisPolitics + Human RightsScience + Technology

BY Matthew Beard 25 FEB 2021

News will soon return to Facebook, with the social media giant coming to an agreement with the Australian government. The deal means Facebook won’t be immediately subject to the News Media Bargaining Code, so long as it can strike enough private deals with media companies.

Facebook now has two months to mediate before the government gets involved in arbitration. Most notably, Facebook have held onto their right to strip news from the platform to avoid being forced into a negotiation.

Within a few days, your feed will return to normal, though media companies will soon be getting a better share of the profits. It would be easy to put this whole episode behind us, but there are some things that are worth dwelling on – especially if you don’t work in the media, or at a social platform but are, like most of us, a regular citizen and consumer of news. Because when we look closely at how this whole scenario came about, it’s because we’ve largely been forgotten in the process.

Announcing Facebook’s sudden ban on Australian news content last week, William Easton, Managing Director of Facebook Australia & New Zealand wrote a blog post outlining the companies’ reasons. Whilst he made a number of arguments (and you should read them for yourself), one of the stronger claims he makes is that Facebook, unlike Google Search, does not show any content that the publishers did not voluntarily put there. He writes:

“We understand many will ask why the platforms may respond differently. The answer is because our platforms have fundamentally different relationships with news. Google Search is inextricably intertwined with news and publishers do not voluntarily provide their content. On the other hand, publishers willingly choose to post news on Facebook, as it allows them to sell more subscriptions, grow their audiences and increase advertising revenue.”

The crux of the argument is this. Simply by existing online, a news story can be surfaced by Google Search. And when it is surfaced, a whole bunch of Google tools – previews, summaries from Google Home, one-line snippets and headlines – give you a watered-down version of the news article you search for. They give you the bare minimum info in an often-helpful way, but that means you never click the site or read the story, which means no advertising revenue or way of knowing the article was actually read.

But Facebook is different – at least, according to Facebook. Unless news media upload their stories to Facebook, which they do by choice, users won’t see news content on Facebook. And for this reason, treating Facebook and Google as analogous seems unfair.

Now, Facebook’s claims aren’t strictly true – until last week, we could see headlines, a preview of the article and an image from a news story posted on Facebook regardless of who posted it there. And that headline, image and snippet are free content for Facebook. That’s more or less the same as what Facebook says Google do: repurposing news content that can be viewed without ever having to leave the platform.

However, these link previews are nowhere near as comprehensive as what Google Search does to serve up their own version of news stories for the company’s own purpose and profit. Most of the news content you see on Facebook is there because it was uploaded there by media companies – who often design video or visual content explicitly to be uploaded to Facebook and to reach their audience.

However, on a deeper level, there seem to be more similarities between Google and Facebook than the latter wants to admit, because the size and audience base Facebook possesses makes it more-or-less essential for media organisations to have a presence there. In a sense, the decision to have a strategy on Facebook is ‘voluntary’, but it’s voluntary in the same way that it’s voluntary for people to own an attention-guzzling, data sucking smartphone. We might not like living with it, but we can’t afford to live without it. Like inviting your boss to your wedding, it’s voluntary, but only because the other options are worse.

Facebook would likely claim innocence of this. Can they really be blamed for having such an engaging, effective platform? If news publishers feel obligated to use Facebook or fall behind their competitors that’s not something Facebook should feel bad about or be punished for. If, as Facebook argue, publishers use them because they get huge value from doing so, it does seem genuinely voluntary – desirable, even.

Even if this is true, there are two complications here. First, if news media are seriously reliant on Facebook, it’s because Facebook deliberately cultivated that. For example, five years ago Facebook was a leading voice behind the ‘pivot to video’, where publishers started to invest heavily in developing video content. Many news outlets drastically reduced writing staff and investment in the written word, instead focussing on visual content.

Three years later, we learned that Facebook had totally overstated the value of video – the pivot to video, which served Facebook’s interests, was based on a self-serving deception. This isn’t the stuff of voluntary, consensual relationships.

Let’s give Facebook a little benefit of the doubt though. Let’s say they didn’t deliberately cultivate the media’s reliance on their platform. Still, it doesn’t follow obviously from this that they have no responsibility to the media for that reliance. Responsibility doesn’t always come with a sign-up sheet, as technology companies should know all too well.

French theorist Paul Virilio wrote that “When you invent the ship, you also invent the shipwreck; when you invent the plane you also invent the plane crash; and when you invent electricity, you invent electrocution.” Whilst Virilio had in mind technology’s dualistic nature, modern work in the ethics of technology invites us to interpret this another way.

If inventing a ship also invents shipwrecks, it might be up to you to find ways to stop people from drowning.

Technology companies – Facebook included – have wrung many a hand talking about the ‘unintended consequences’ of their design and accepting responsibility for them. In fact, speaking before a US Congress Committee, Mark Zuckerberg himself conceded as much, saying:

“It’s clear now that we didn’t do enough to prevent these tools from being used for harm, as well. And that goes for fake news, for foreign interference in elections, and hate speech, as well as developers and data privacy. We didn’t take a broad enough view of our responsibility, and that was a big mistake. And it was my mistake. And I’m sorry. I started Facebook, I run it, and I’m responsible for what happens here.”

It seems unclear why Facebook recognised their responsibility in one case, but seem to be denying it in another. Perhaps the news media are not reliant – or used by – Facebook in the same way as they are Google, but it’s not clear this goes far enough to free Facebook of responsibility.

At the same time, we should not go too far the other way, denying the news media any role in the current situation. The emergence of Facebook as a lucrative platform seems to have led the media to a Faustian pact – selling their soul for clicks, profit and longevity. In 2021 it seems tired to talk about how the media’s approach to news – demanding virality, speed, shareability – are a direct result of their reliance on platforms like Facebook.

The fourth estate – whose work relies on them serving the public interest – adopted a technological platform and in so doing, adopted its values as their own: values that served their own interests and those of Facebook rather than ours. For the media to now lament Facebook’s decision as anti-democratic denies the media’s own blameworthiness for what we’re witnessing.

But the big reveal is this: we can sketch out all the reasons why Facebook or the media might have the more reasonable claim here, or why they share responsibility for what went down, but in doing so, we miss the point. This shouldn’t be thought of as a beef between two industries, each of whom has good reasons to defend their patch.

What needs to be defended is us: the community whose functioning and flourishing depends on these groups figuring themselves out.

Facebook, like the other tech giants, have an extraordinary level of power and influence. So too do the media. Typically, we don’t to allow institutions to hold that kind of power without expecting something in return: a contribution to the common good. This understanding – that powerful institutions hold their power with the permission of a community they deliver value to – is known as a social license.

Unfortunately, Facebook have managed to accrue their power without needing a social license. All power, no permission.

This is in contrast to the news media, whose powers aren’t just determined by their users and market share, but by the special role we afford them in our democracy, the trust and status we afford their work isn’t a freebie: it needs to be earned. And the way it’s earned is by using that power in the interests of the community – ensuring we’re well-informed and able to make the decisions citizens need to make.

The media – now in a position to bargain with Facebook – have a choice to make. They can choose to negotiate in ways that make the most business sense for them, or they can choose to think about what arrangements will best serve the democracy that they, as the ‘fourth estate’, are meant to defend. However, at the very least they know that the latter is expected of them – even if the track record of many news publishers gives us reason to doubt.

Unfortunately, they’re negotiating with a company whose only logic is that of a private company. Facebook have enormous power, but unlike the media, they don’t have analogous mechanisms – formal or informal – to ensure they serve the community. And it’s not clear they need it to survive. Their product is ubiquitous, potentially addictive and – at least on the surface – free. They don’t need to be trusted because what they’re selling is so desirable.

This generates an ethical asymmetry. Facebook seem to have a different set of rules to the media. Imagine, for a moment, if the media chose to stop reporting for a fortnight to protest a new law. The rightful outrage we would feel as a community would be palpable. It would be nearly unforgivable. And yet we do not hold Facebook to the same standards. And yet, perhaps at this point, they’ve made themselves almost as influential.

There’s a lot that needs to happen to steady the ship – and one of the most frustrating things about it is that as individuals, there isn’t a lot we can do. But what we can do is use the actual license we have with Facebook in place of a social license.

If we don’t like the way a news organisation conducts themselves, we cancel our subscriptions; we change the channel. If you want to help hold technology companies to account, you need to let your account to the talking. Denying your data is the best weapon you’ve got. It might be time to think about using it – and if not, under what circumstances you might.

This project is supported by the Copyright Agency’s Cultural Fund.

![]()

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

What do we want from consent education?

Big thinker

Politics + Human Rights

Big Thinker: Peter Singer

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights

Can philosophy help us when it comes to defining tax fairness?

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

How to have a conversation about politics without losing friends

BY Matthew Beard

Matt is a moral philosopher with a background in applied and military ethics. In 2016, Matt won the Australasian Association of Philosophy prize for media engagement. Formerly a fellow at The Ethics Centre, Matt is currently host on ABC’s Short & Curly podcast and the Vincent Fairfax Fellowship Program Director.

Tim Soutphommasane on free speech, nationalism and civil society

Tim Soutphommasane on free speech, nationalism and civil society

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + LeadershipPolitics + Human RightsRelationships

BY The Ethics Centre 18 FEB 2021

We believe conversations matter. So when we had the opportunity to chat with Tim Soutphommasane we leapt at the chance to explore his ideas of a civil society. Tim is an academic, political theorist and human rights activist. A former public servant, he was Australia’s Race Discrimination Commissioner at the Australian Human Rights Commission from 2013 – 2018 and has been a guest speaker at the Festival of Dangerous Ideas. Now a professor at Sydney University, he shared with The Ethics Centre his thoughts on the role of the media, free speech, racism and national values.

What role should the media play in supporting a civil society?

The media is one place where our common life as a society comes into being. It helps project to us our common identity and traditions. But ideally media should permit multiple voices, rather than amplify only the voices of the powerful. When it is dominated by certain interests, it can destroy rather than empower civil society.

How should a civil society reckon with the historical injustices it benefits from today?

A mature society should be able to make sense of history, without resorting to distortion. Yet all societies are built on myths and traditions, so it’s not easy to achieve a reckoning with historical injustice. But, ultimately, a mature society should be able to take pride in its achievements and be critical of its failings – all while understanding it may be the beneficiary of past misdeeds, and that it may need to make amends in some way.

Should a civil society protect some level of intolerance or bigotry?

It’s important that society has the freedom to debate ideas, and to challenge received wisdom. But no freedom is ever absolute. We should be able to hold bigotry and intolerance to account when it does harm, including when it harms the ability of fellow citizens to exercise their individual freedoms.

What do you think we can do to prevent society from becoming a ‘tyranny of the majority’?

We need to ensure that we have more diverse voices represented in our institutions – whether it’s politics, government, business or media.

What is the right balance between free speech and censorship in a civil society?

Rights will always need to be balanced. We should be careful, though, to distinguish between censorship and holding others to account for harm. Too often, when people call out harmful speech, it can quickly be labelled censorship. In a society that values freedom, we naturally have an instinctive aversion to censorship.

How can a society support more constructive disagreement?

Through practice. We get better at everything through practice. Today, though, we seem to have less space or time to have constructive or civil disagreements.

What is one value you consider to be an ‘Australian value’?

Equality, or egalitarianism. As with any value, it’s contested. But it continues to resonate with many Australians.

Do you believe there’s a ‘grand narrative’ that Australians share?

I think a national identity and culture helps to provide meaning to civic values. What democracy means in Australia, for instance, will be different to what it means in Germany or the United States. There are nuances that bear the imprint of history. At the same time, a national identity and culture will never be frozen in time and will itself be the subject of contest.

And finally, what’s the one thing you’d encourage everyone to commit to in 2021?

Talk to strangers more.

To read more from Tim on civil society, check out his latest article here.

Tim Soutphommasane is a political theorist and Professor in the School of Social and Political Sciences, The University of Sydney, where he is also Director, Culture Strategy. From 2013 to 2018 he was Race Discrimination Commissioner at the Australian Human Rights Commission. He is the author of five books, including The Virtuous Citizen (2012) and most recently, On Hate (2019).

This project is supported by the Copyright Agency’s Cultural Fund.

![]()

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Politics + Human Rights, Relationships, Science + Technology

The value of a human life

Explainer

Society + Culture, Politics + Human Rights

Thought experiment: The original position

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: The Other

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Science + Technology

Who’s to blame for Facebook’s news ban?

Join our newsletter

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Settler rage and our inherited national guilt

Settler rage and our inherited national guilt

Opinion + AnalysisPolitics + Human Rights

BY Sarah Maddison 21 JAN 2021

Professor Marcia Langton offers a distinctive term for settler-Australian racism towards Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. She calls it the ‘settler mentality’. In her FODI Digital lecture Langton suggests that the experience of living unjustly on stolen Indigenous lands has produced in settler Australians a ‘peculiar hatred’ expressed through ‘settler rage against the people with whom they will not treat.’

While Langton observes the manifold evidence of ‘classical, formal racism’, she maintains that the underlying problem in Australia is ‘a settler population that cannot come to terms with its Indigenous population.’ Here, Langton touches upon a long running debate among scholars seeking to understand the ongoing conflict in Indigenous-settler relations. For some, race—and racism—are the primary lens for understanding both historical and contemporary injustice.

On this view, colonialism is in service to racism, enabling a white supremacist nation to take root on this continent. There is an abundance of evidence to support that claim, for example in the history of eugenicist practices in Australia including the ‘degrees of blood’ that for decades were used to justify the separation Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children from their families.

But for me there has always been more weight to support the counter view expressed by Langton.

Racism is real, certainly, but it operates in service to colonialism.

Colonialism cares less about the skin colour of the peoples it dispossesses and far more about accessing and controlling their land. It is in pursuit of land and the resources in and of that land that colonisers everywhere have committed atrocities against Indigenous peoples.

Australia is no exception. It is colonisation and the subsequent failure to negotiate treaties with First Nations on this continent that give rise to the settler state’s moral and legal illegitimacy. Colonisation is violent—no people anywhere in the world have been dispossessed of their land peacefully, and again, Australia is no exception.

Despite the state’s steadfast refusal to properly acknowledge this history, the evidence of over a century of frontier warfare is no secret. It never has been.

In her address, Langton mentions Australian historian Henry Reynolds’ book, This Whispering in Our Hearts, about those who recognised the injustices being perpetrated and were prepared to contest the violence of colonisation.

Langton points out that these settlers were well aware that they had ‘committed a monstrous crime’ and suggests that the criminality of the settler has produced in them a trauma similar to the kind that the German population had to deal with in the wake of the horrors of World War II. In making this comparison Langton references the German academic and novelist Bernhard Schlink’s famous novel The Reader.

In my own work I have drawn on another of Schlink’s books, the non-fiction volume Guilt About the Past, in which he unpacks the way in which the crimes of previous generations infect more than the generation that lives through the era (in his case Nazi Germany).

Schlink argues that guilt about the past also ‘casts a long shadow over the present, infecting later generations with a sense of guilt, responsibility and self-questioning.’ Schlink suggests subsequent generations create their own guilt when, in the face of evidence of past atrocities, they maintain a bond of solidarity with the perpetrators by failing to renounce their actions.

Australian national identity rests on the fantasy that the continent was virtually empty of people when the British arrived and went on to be peacefully settled.

Despite mounting scientific and historical evidence of the sophistication of Indigenous societies, the myth persists that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples were ‘primitive’ and backward, and that colonisation brought them the benefits of Western ‘civilisation’.

Settlers hang onto these wrongheaded ideas as a means of justifying our presence and denying the horrors that accompanied dispossession. There is no easy path for reckoning with our forefathers’ crimes, there cannot really be redemption.

If we are here illegitimately then where do we properly belong? If the land is not ours then where should we live? If our presence here is the result of massacre and genocide how do we even begin to make that right?

And so the bonds of solidarity with the original perpetrators live on, deep within settler DNA. For every revelation of past atrocity there will be a critic ready to deny the harms done.

For every proposal to make amends for the past through more just relations today, there is a politician or a journalist ready to defend Australia’s colonial history as a sad but inevitable chapter on the road to modernity. For every call that we not celebrate our national day on the day the atrocities began for Indigenous peoples there is a chorus of criticism in defense of nationalism and ‘Australian identity.’

These responses are damaging to both settler and Indigenous peoples.

While Indigenous peoples are left still to struggle for justice, settlers are left with paralysis.

The peculiar hatred that Langton describes is like a poison in settler society. This poison makes us brittle, defensive, unkind, and greedy, unwilling to give up any of the wealth we have gained through atrocity and dispossession.

Yet even as it makes us sick, still we drink the poison up. This has been the settler’s choice since this continent was first invaded. We can, however, make a different choice. The antidote to the poison of settler society is justice, and it is not beyond our reach.

This project is supported by the Copyright Agency’s Cultural Fund.

![]()

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Climate + Environment, Politics + Human Rights

Who is to blame? Moral responsibility and the case for reparations

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights

Nurses and naked photos

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Ethics in a time of coronavirus

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Would you kill baby Hitler?

Join our newsletter

BY Sarah Maddison

Sarah Maddison is an Australian author and Professor of Politics in the School of Social and Political Sciences at the University of Melbourne where she also co-directs the Indigenous Settler Relations Collaboration. She is a former Director of GetUp! and the 2018-19 president of the Australian Political Studies Association.

Your kid’s favourite ethics podcast drops a new season to start 2021 right

Your kid’s favourite ethics podcast drops a new season to start 2021 right

Opinion + AnalysisHealth + Wellbeing

BY Matthew Beard 21 JAN 2021

If your kids are anything like mine, the holidays have officially hit the ‘we’ve dragged on too long’ stage.

Your children drift like bored zombies from room to room, looking for another screen or toy to give them a fresh dopamine hit.

They don’t want to admit it, but they’re ready for school to go back. You’re all hanging out for that first day.

Good news! You can stop waiting. You don’t need to let the boredom drag on until school goes back. You can get your child’s – and your own – synapses firing right now and sharpen your ethical sensibilities in the process, thanks to a new season of Short & Curly, the award-winning, chart-topping ethics podcast produced by the ABC, and featuring Ethics Centre fellow Matt Beard (that’s me).

The podcast, now in its 13th season, is a playful, light-hearted and engaging exploration of ethics. It’s driven by the central belief that ethics is a team sport, and each twenty-minute episode features a number of ‘thinking questions’ where listeners are encouraged to pause the show to talk about some big ideas with the people around them. This isn’t just a podcast for your kids – it’s one for you as well!

The latest season comprises of five episodes on a wide range of topics and settings, including:

- A class being held back by an angry teacher hell-bent on finding out who stole her cookies, prompting us to ask: is collective punishment is ever justified?

- An impromptu beach trip is cancelled thanks to a fear of sharks – should we cull sharks to make sure that swimmers can enjoy the ocean free of fear?

- Frozen and The Avengers turn a casual trivia night into a discussion of one of the oldest questions in ethics: do the ends ever justify the means?

- As the Amazon – the lungs of the world – continues to burn, putting all of us an increased threat to climate change, we go on a tour of the Amazon and ask who owns the rainforest, and who should decide how to treat it?

- We take a tour of the wonderful world of robots! Looking at the various ways that robots could replace humans in the future, and ask whether or not they should.

One of the pitfalls of parenting is making ‘doing the right thing’ seem like the opponent of fun. If our kids see ethics as more closely connected to discipline than it is to curiosity, we risk setting them up for a mode of thinking that doesn’t serve them or the world they’ll help build.

Whether or not you’re tuning into the podcast, try to make imagination, creativity and curiosity your default settings when discussing ethics with your kids. Do your best not to close off discussion by giving your ‘authoritative’ view. Discussions don’t work well under hierarchies. And if you need some more pointers, check out our handy guide to talking to kids about ethics here.

Oh, and there may be some extremely bad rapping in one of the episodes. I won’t tell you which one, but be on the lookout!

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Mutuality of care in a pandemic

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Moving on from the pandemic means letting go

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Ask me tell me: Why women think it’s ok to lie about contraception

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Health + Wellbeing

Your donation is only as good as the charity you give it to

Join our newsletter

BY Matthew Beard

Matt is a moral philosopher with a background in applied and military ethics. In 2016, Matt won the Australasian Association of Philosophy prize for media engagement. Formerly a fellow at The Ethics Centre, Matt is currently host on ABC’s Short & Curly podcast and the Vincent Fairfax Fellowship Program Director.

No justice, no peace in healing Trump's America

No justice, no peace in healing Trump’s America

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + LeadershipPolitics + Human Rights

BY Simon Longstaff 21 JAN 2021

What fate should be reserved for Donald Trump following his impeachment by the US House of Representatives for his role in inciting insurrection?

Trump’s rusted-on supporters believe him to be without blame and will continue to lionise him as a paragon of virtue. Trump’s equally rusted-on opponents see only fault and wish him to be ground under the heel of history.

However, there is a large body of people who approach the question with an open mind – only to remain genuinely confused about what should come next.

On the one hand, there is an abiding fear that punishing Trump will fan the flames that animate his angry supporters elevating Trump’s status to that of ‘martyr-to-his-cause’. Rather than bind wounds and allow the process of healing to begin, the divisions that rend American society will only be deepened.

On the other hand, people believe that Trump deserves to be punished for violating his Oath of Office. They too want the wounds to be bound – but doubt that there can be healing without justice. Only then will people of goodwill be able to come together and, perhaps, find common ground.

There is merit in both positions. So, how might we decide where the balance of judgement should lie?

To begin, I think it unrealistic to hope for the emergence of a new set of harmonious relationships between the now three warring political tribes, the Republicans, Democrats and Trumpians. The disagreements between these three groups are visceral and persistent.

Rather than hope for harmony, the US polity should insist on peace.

Indeed, it is the value of ‘peace’ that has been most significantly undermined in the weeks since the Presidential election result was called into question by Donald Trump and his supporters. Rather than anticipate a ‘peaceful transition of power’ – which is the hallmark of democracy – the United States has been confronted by the reality of violent insurrection.

As it happens, I think that President Trump’s recent conduct needs to be evaluated against an index of peace – not just in general terms but specifically in light of what occurred on January 6th when a mob of his supporters, acting in the President’s name, broke into and occupied the US Capitol buildings – spilling blood and bringing death inside its hallowed chambers.

There is a particular type of peace that can be traced back to the Anglo-Saxon legal codes that provide the foundation for many of the laws we take for granted today. The King’s Peace originally applied to the monarch’s household – not just the physical location but also the ruler, their family, friends and retainers. It was a serious crime to disturb the ‘King’s Peace’. Over time, the scope of the King’s Peace was extended to cover certain times of the year and a wider set of locations (e.g. all highways were considered to be subject to fall under the King’s jurisdiction). Following the Norman Conquest, there was a steady expansion of the monarch’s remit until it covered all times and places – standing as a general guarantee of the good order and safety of the realm.

The relevance of all of this to Donald Trump lies in the ethical (and not just legal) effect of the King’s Peace. Prior to its extension, whatever ‘justice’ existed was based on the power of local magnates. In many (if not most places) disputes were settled on the principle of ‘might was right’.

The coming of the King’s Peace meant that only the ruler (and their agents) had the right to settle disputes, impose penalties, etc. The older baronial courts were closed down – leaving the monarch as the fountainhead of all secular justice. In a nutshell, individuals and groups could no longer take the law into their own hands – no matter how powerful they might be.

These ideas should immediately be familiar to us – especially if we live in nations (like the US and Australia) that received and have built upon the English Common Law. It is this idea that underpins what it means to speak of the Rule of Law – and everything, from the framing of the United States Constitution to the decisions of the US Supreme Court depend on our common acceptance that we may not secure our ends, no matter how just we think our cause, through the private application of force.

As should by now be obvious, those who want to forgive Donald Trump for the sake of peace are confronted by what I think is an insurmountable paradox. Trump’s actions fomented insurrection of the kind that fundamentally broke the peace – indeed makes it impossible to sustain. The insurrectionists took the law into their own hands and declared that ‘might is right’ … and they did so with the encouragement of Donald Trump and those who stood by him and whipped up the crowd in the days leading up to and on that fateful day when the Capitol was stormed.

There literally can be no peace – and therefore no healing – unless the instigators of this insurrection are held to account.

Finally, this is not to say that Donald Trump must suffer his punishment. There is no need for retribution or a restoration, through suffering, of a notional balance between ‘right’ and ‘wrong’. It may be enough to declare Donald Trump guilty of the ‘high crime and misdemeanour’ for which he was impeached. And if he remains without either shame or remorse, then it may also be necessary to protect the Republic from him ever again holding elected office – not to harm him but, instead, to protect the body politic.

Given all of this, I think that healing is possible … but only if built on a foundation of peace based on justice without retribution.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Corporate tax avoidance: you pay, why won’t they?

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Business + Leadership

The ethical dilemma of the 4-day work week

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Assisted dying: 5 things to think about

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Does Australian politics need more than just female quotas?

BY Simon Longstaff

After studying law in Sydney and teaching in Tasmania, Simon pursued postgraduate studies in philosophy as a Member of Magdalene College, Cambridge. In 1991, Simon commenced his work as the first Executive Director of The Ethics Centre. In 2013, he was made an officer of the Order of Australia (AO) for “distinguished service to the community through the promotion of ethical standards in governance and business, to improving corporate responsibility, and to philosophy.”

Elf on the Shelf is a fun and festive way to teach your child to submit to the surveillance state

Elf on the Shelf is a fun and festive way to teach your child to submit to the surveillance state

Opinion + AnalysisRelationships

BY Matthew Beard 15 DEC 2020

Imagine if every school in Australia introduced comprehensive surveillance technology coupled with facial recognition, and was able to assign a score to each student based on how good a “school citizen” they were.

Students could access an app that provided them with feedback on things they’d done, or failed to do, throughout the day. The day-to-day data could then be collected and a general character assessment made of the child on, let’s say, a year-by-year basis. At the end of the year, maybe at presentation night, students would be told if they’d been “good” school citizens or not.

I’m going to go out on a limb and suggest most people would find this idea pretty repugnant. Many would see echoes of China’s oppressive social credit system. Words like “Orwellian” would be thrown around with reckless abandon.

Just don’t tell that to the families around the world for whom Christmas involves a character check from Santa Claus. Certainly don’t tell the 11 million-odd who have “adopted’” an Elf on the Shelf and will have dusted it off for the season.

If you haven’t heard of it, the Elf on the Shelf explains how Santa is able to see you when you’re sleeping and know when you’re awake. Manufactured by Creatively Classic Activities and Books, the Elf on the Shelf is a tool used by families to add some more wonder and fun to the Christmas season.

Parents move the elf around, and kids look to see where it will appear next. They’re often also told that because they don’t know where the elf is or what the elf is watching, they’d better make sure they’re behaving themselves. After all, the elf’s job is to report back to Santa.

That’s right. Santa has an army of tiny, surprisingly mobile little snitches embedded in every home, watching, collecting data, feeding it back to the big guy. For some families, the elf also leaves handy notes for the kids, to make sure they stay on St Nick’s good side. “I don’t like it when you don’t share your toys. I don’t want to have to tell Santa about this behaviour,” reads one note a parent shared online.

Social credit be damned. Santa had it figured out this whole time!

We tend to be more sceptical of surveillance when it comes to our kids. For instance, recent trials of facial recognition in Victorian schools have been met with human rights concerns and academic criticism. When Mattel developed Aristotle, a digital assistant to be given to newborn children who would grow and develop alongside them, it was pulled from the market for privacy concerns. Even tools like GPS tracking apps are the subject of general debate and controversy.

There are good reasons for these concerns. Law professor Julie E Cohen argues that “privacy fosters self-determination” and that it is “shorthand for breathing room to engage in the processes of boundary management that enable and constitute self-development”.

So, not only does the collection of children’s data put them at risk if that data falls into the wrong hands, there’s a stifling effect on children’s development when they feel like they’re continually being watched.

But the Elf on the Shelf isn’t quite analogous to China’s mass surveillance. For one thing, Santa only has about 11 million elves out there, which is amateur hour compared to China’s “Skynet” of over 200m cameras. For another, the Elf on the Shelf doesn’t use fear and promises of safety to gain people’s comfort with surveillance and data gathering; it uses fun.

Less like a social credit system, more Facebook. Esteemed company indeed.

Of course, Elf on the Shelf isn’t actually surveillance because – spoiler alert – it’s based on a myth. I’ve no doubt plenty of parents will dismiss what I’m saying here as unnecessary scaremongering over something that’s actually fine, fun and basically a bit of stupid play at Christmas time.

While this wouldn’t be the first time a philosopher has been accused of sucking the fun out of a situation, I’m not sure that argument cuts it.

First, the rise of “sharenting” and the pushback from children against parents who post too much information about them online indicates parents are not always the best custodians of their kids’ privacy. In general, a generation prone to oversharing on social media may not be the best judges of what lessons Elf on the Shelf is teaching.

Second, and more importantly, the effects of surveillance work even if the surveillance isn’t really happening. This was the genius of the infamous Panopticon – a prison designed by British philosopher Jeremy Bentham, where a guard tower could potentially observe any prisoner at any given time, but no prisoner could see the guard tower. It was always possible that you were being observed, which meant you behaved as though you were being observed at all times.

This logic is, of course, very creepy. It’s also very common – as another philosopher, Michel Foucault, later pointed out. You can build workplaces, schools, mental health institutions and yes, nationwide mass surveillance networks on similar principles. The concept is that the possibility of observation and judgement means there’s no need to force people to conform – they do it themselves. Arguably, China’s social credit system is the high-water mark of the logic of the Panopticon.

But the rhetoric – intentional or not – behind Elf on the Shelf has echoes of the Panopticon. It reads from the same playbook. The elf appears at random times and in random locations. It’s always possibly watching.

Whether that’s the goal parents are trying to achieve or not, we ought to be concerned about the effects of introducing and normalising this kind of behaviour monitoring and observation to kids.

As Olly Thorn, the philosopher behind Philosophy Tube tweeted: “He sees you when you’re sleeping He knows, when you’re awake, It’s a subtle, calculated technology of subjection.”

This isn’t necessarily a reason to ditch the tradition, but we can do away with the creepiness – especially as the myth becomes more and more like reality. It’s entirely possible to have an Elf on the Shelf and not play this game. Maybe the elf is just waiting for Santa to come and deliver the presents – and helps him unload the gifts. Perhaps you don’t use the elf as a tool for discipline but as a game and a story that’s played together.

Maybe you don’t need to tell the Santa story at all, but that’s another matter.

This article was first published in The Guardian Australia on 16 December, 2019.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

After Christchurch

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Is it wrong to care about Ukraine more than other wars?

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

What exotic pets teach us about the troubling side of human nature

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Science + Technology

We are being saturated by knowledge. How much is too much?

Join our newsletter

BY Matthew Beard

Matt is a moral philosopher with a background in applied and military ethics. In 2016, Matt won the Australasian Association of Philosophy prize for media engagement. Formerly a fellow at The Ethics Centre, Matt is currently host on ABC’s Short & Curly podcast and the Vincent Fairfax Fellowship Program Director.

We live in an opinion economy, and it’s exhausting

We live in an opinion economy, and it’s exhausting

Opinion + AnalysisRelationships

BY Matthew Beard 25 NOV 2020

This is the moment when I’m finally going to get my Advanced Level Irony Badge. I’m going to write an opinion piece on why we shouldn’t have so many opinions.

I’ve spent the majority of this week digesting the findings from the IDGAF Afghanistan Inquiry Report. I’m still making sense of the scope and scale of what was done, the depth of the harm inflicted on the Afghan victims and their community at large and how Australian warfighters were able to commit and permit crimes of this nature to occur.

My academic expertise is in military ethics, so I’ve got an unfair advantage when it comes to getting a handle on this issue quickly, but still, I was late to the opinion party. Within an hour or so of the report’s publication, opinions abounded on social media about what had happened, why and who was to blame. This, despite the report being over five hundred pages long.

We spend a lot of time today fearing misinformation. We usually think about the kind that’s deliberate – ‘fake news’ – but the virality of opinions, often underinformed, is also damaging and unhelpful. It makes us confuse speed and certainty with clarity and understanding. And in complex cases, it isn’t helpful.

More than this, the proliferation of opinions creates pressure for us to do the same. When everyone else has a strong view on what’s happened, what does it say about us that we don’t?

We live in a time when it’s not enough to know what is happening in the world, we need to have a view on whether that thing is good or bad – and if we can’t have both, we’ll choose opinion over knowledge most times.

It’s bad for us. It makes us miserable and morally immature. It creates a culture in which we’re not encouraged to hold opinions for their value as ways of explaining the world. Instead, their job is to be exchanged – a way of identifying us as a particular kind of person: a thinker.

If you’re someone who spends a lot of time reading media, you’ve probably done this – and seen other people do this. In conversations about an issue of the day, people exchange views on the subject – but most of them aren’t their views. They are the views of someone else.

Some columnist, a Twitter account they follow, what they heard on Waleed Aly’s latest monologue on The Project. And they then trade these views like grown-up Pokémon cards, fighting battles they have no stake in, whose outcome doesn’t matter to them.

This is one of many things the philosopher Soren Kierkegaard had in mind when he wrote about the problems with the mass media almost two centuries ago. Kierkegaard, borrowing the phrase “renters of opinion” from fellow philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer, wrote that journalism:

“makes people doubly ridiculous. First, by making them believe it is necessary to have an opinion – and this is perhaps the most ridiculous aspect of the matter: one of those unhappy, inoffensive citizens who could have such an easy life, and then the journalist makes him believe it is necessary to have an opinion. And then to rent them an opinion which, despite its inconsistent quality, is nevertheless put on and carried around as an article of necessity.”

What Kierkegaard spotted then is just as true today – the mass media wants us to have opinions. It wants us to be emotional, outraged, moved by what happens. Moreover, the uneasy relationship between social media platforms and media companies makes this worse.

Social media platforms also want us to have strong opinions. They want us to keep sharing content, returning to their site, following moment-by-moment for updates.

Part of the problem, of course, is that so many of these opinions are just bad. For every straight-to-camera monologue, must-read op-ed or ground-breaking 7:30 report, there is a myriad of stuff that doesn’t add anything to our understanding. Not only that, it gets in the way. It exhausts us, overwhelms us and obstructs real understanding, which takes time, information and (usually) expert analysis.

Again, Kierkegaard sees this problem unrolling in his own time. “Everyone today can write a fairly decent article about all and everything; but no one can or will bear the strenuous work of following through a single solitary thought into the most tenuous logical ramifications.”

We just don’t have the patience today to sit with an issue for long enough to resolve it. Before we’ve gotten a proper answer to one issue, the media, the public and everyone else chasing eyes, ears, hearts and minds has moved on to whatever’s next on the List of Things to Care About.

So, if you’re reading the news today and wondering what you should make of it, I release you. You don’t have to have the answers. You can be an excellent citizen and person without needing something interesting to say about everything.

If you find yourself in a conversation with your colleagues, mates or even your kids, you don’t need to have the answers. Sometimes, a good question will do more to help you both work out what you do and don’t know.

This is not an argument to stop caring about the world around us. Instead, it’s an argument to suggest that we need to rethink the way we’ve connected caring about something with having an opinion about something.

Caring about a person, or a community means entering into a relationship with them that enables them to flourish. When we look at the way our fast-paced media engages with people – reducing a woman, daughter, friend and victim of a crime to her profession, for instance – it’s not obvious this is making us care. It’s selling us a watered-down version of care that frees us of the responsibility to do anything other than feel.

Of course, this is possible. Journalistic interventions, powerful opinion-driven content and social media movements can – and have – made meaningful change in society. They have made people care.

I wonder if those moments are striking precisely because they are infrequent. By making opinions part of our social and economic capital, we’ve increased the frequency with which we’re told to have them, but alongside everything else, it might have diluted their power to do anything significant.

This article was first published on 21 August, 2019.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

When are secrets best kept?

Big thinker

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Big Thinker: Shulamith Firestone

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Science + Technology

If humans bully robots there will be dire consequences

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

Is it ethical to splash lots of cash on gifts?

Join our newsletter

BY Matthew Beard

Matt is a moral philosopher with a background in applied and military ethics. In 2016, Matt won the Australasian Association of Philosophy prize for media engagement. Formerly a fellow at The Ethics Centre, Matt is currently host on ABC’s Short & Curly podcast and the Vincent Fairfax Fellowship Program Director.

What's the use in trying?

What’s the use in trying?

Opinion + AnalysisPolitics + Human RightsRelationships

BY Eleanor Gordon Smith The Ethics Centre 24 AUG 2020

In early 2020 I sat in a friend’s house on the coast of New South Wales listening to smoke alarms go off in canon, triggered by the air itself, thick with smoke from the active fronts of the worst bushfire season in living memory.

The roads were lined with scorched animals and the climate crisis seemed as inevitable as it did cataclysmic. It was unthinkable then that this moment of apparently superlative awfulness would, in a matter of months, recede to just one more entry in a year-long list of suffering, death, and massive-scale crisis.

The lucky of us stayed inside afraid for months. The unlucky died, or lost loved ones and could not go to their funerals. There was widespread and systematic police violence against black people and against the people who protested it. USD $3.6 trillion was wiped off the stock market in one week.

The first six months of 2020 presented an unusually literal illustration of an old ethical question: why bother when the conclusion feels foregone?

What many of us felt about the climate in January was a well-known phenomenon: the fatigue of feeling useless when we felt we could not rely on the powerful to make changes or on other people to do their part. This feeling was quickly matched by parallels in resistance to systemic racism, in fighting an economic downturn and even in pandemic compliance.

Early on in the COVID-19 outbreak, data modelling revealed that social distancing would only work if 8 out of 10 of us followed the rules. If only 70% of us stood six feet apart, washed our hands, and stayed inside for weeks on end, it would be as though none of us had. To the misanthropist who felt that 30% of people would surely disregard the rules, a motivational gap loomed: why do what I can to help, when I’m not confident it will.

Even to the most resiliently motivated, parts of 2020 posed this problem. Hundred-thousand strong protests in the United States were not enough to prevent the deaths of more unarmed black people, nor to prevent protestors themselves from being pepper-sprayed at close range.

The indefatigability of the protests seemed met by the indefatigability of the problem. For many people it became impossible to feel calm or ordered anywhere as long as case numbers rose. So it seemed foregone that our homes would not feel calm or ordered either, and the motivation to improve them frayed in proportion to the dishes in the sink.

The philosopher and psychologist William James knew that certain beliefs can be self-validating; that confidence in outcomes, however, we come by it, can make itself well placed. The sailors who think they can pull the heavy rope are more likely to summon the gusto and collective coordination required to make it the case that they can. This first half of 2020 was a vivid illustration of the photonegative; the fact that uncertainty about outcomes can be enough to puncture our drive to pursue them.

So what is there to be done? Few of us believe that this pessimism or uncertainty in fact means that it is not worth protesting, or washing our hands, or doing the dishes. We still rationally endorse that we ought to do these things. But it becomes a wrench, an act of shepherding ourselves, parent-like, and it wears us down. It leads us to misanthropy.

An answer lies in looking more closely at one facet of what 2020 has cost us. We lost the most unthinking parts of our lives; the well-worn routine of the drive home or the setup at the gym, the clockwork Wednesday night choir, the disappearance into a team practicing a physical skill.

These were moments where what we did was not to achieve, or to think, but to be in a process. It was immaterial to us whether we achieved victory or even improvement, since our commitment to doing them was not dependent on whether we did. What we wanted was to be absorbed, to be a creature who acts.

We are, unavoidably, creatures who act. But as philosopher Mark Schroeder has noted, there is an asymmetry between our options in thought and our options in action. We have three options about what to think: we can believe what is on offer, reject it, or withhold judgement. But in action we have only two options; act or do not. There is no way to be in the world that avoids this two-prong choice.

When we realize this, we can shift our focus in a way that avoids futility fatigue. Our moral duty to act – and so too, our motivation – need not be entirely derived from what will happen once we do. It may be that what we owe each other is action itself, and effort itself.

In turn, this can release us from some pressure that comes with knowing that our goals will be difficult to achieve and fragile once we get them. We can simply aim at the action itself. We can find in resistance, in participation, and in care, a goal which is not about the altering of the world but about the observation of the act itself.

In this state, our uncertainty is no longer a threat to our motivation. With this as our focus and our source of energy, we may find that we are, in the end, more effective at altering the world.

You can contact The Ethics Centre about any of the issues discussed in this article. We offer free counselling for individuals via Ethi-call; professional fee-for-service consulting, leadership and development services; and as a non-profit charity we rely heavily on donations to continue our work, which can be made via our website. Thank you.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships, Society + Culture

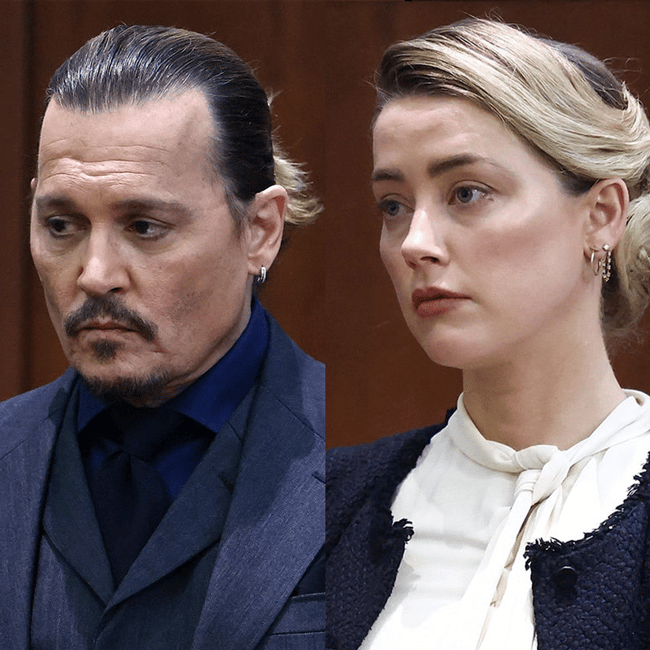

You won’t be able to tell whether Depp or Heard are lying by watching their faces

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Stoicism

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Ethics in a time of coronavirus

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships

The tyranny of righteous indignation

BY Eleanor Gordon Smith

Eleanor Gordon-Smith is a resident ethicist at The Ethics Centre and radio producer working at the intersection of ethical theory and the chaos of everyday life. Currently at Princeton University, her work has appeared in The Australian, This American Life, and in a weekly advice column for Guardian Australia. Her debut book “Stop Being Reasonable”, a collection of non-fiction stories about the ways we change our minds, was released in 2019.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

FODI digital returns for three dangerous conversations

FODI digital returns for three dangerous conversations

Opinion + AnalysisSociety + Culture

BY The Ethics Centre 20 AUG 2020

The Festival of Dangerous Ideas traverses the cracks of our society across three flagship digital events this September and October.

We are living through a period of heightened fear and anxiety. The global pandemic has superheated three systemic problems that were already set to boil: government control of information, racism and climate change.

The three sessions will be streamed live on festivalofdangerousidea.com, with live interaction and questions from the audience. Ticket prices range from $10-$15 or $30 for all three conversations.

Our Festival Director, Danielle Harvey, has carefully curated these three speakers to for this dangerous time. In speaking about the programming, she said “the fallout from the pandemic is changing politics, economics and the every day so significantly.

FODI is a provocateur of big thinking, and it’s back to ask us: what should we be doing now to prepare for a post-pandemic landscape? And has COVID-19 offered opportunity or hindrance to tackling some of the biggest issues of our time in a new and profound way?”

Live stream sessions include:

-

Dangerous Fictions, Marcia Langton, 10 September 2020, 7PM

Langston is a fearless truth-teller who challenges the dangerous orthodoxies of a society that seems incapable of making peace with the truth of its own past.

-

Surveillance States, Edward Snowden, 24 September 2020, 7PM

Snowden asks us to consider the possibility that we may have more to fear from our own governments than from any external threat – and that our liberties have already been lost.

-

The Uninhabitable Earth, David Wallace-Wells, 11 October 2020, 11am

Wallace-Wells says there is no going back from the climate crisis and suggests the greatest challenge is navigating the future in a world that can’t agree how to face it together.

Challenging us all to stop and pay attention, Executive Director of The Ethics Centre and Co-Founder of FODI, Simon Longstaff, said these are pivotal issues are demanding creative solutions.

“The urgency of the moment might seem to demand every moment of our attention, the reality is that this is precisely the time when we need to look beyond the boundaries of the pandemic and come together and … think!”

These events follow on from the first FODI digital series in May which featured Norman Swan, David Sinclair, Claire Wardle, Kevin Rudd, Vicky Xu, Masha Gessen and Stan Grant. Past conversations are available on demand via www.festivalofdangerousidea.com.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

Beyond cynicism: The deeper ethical message of Ted Lasso

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

Barbie and what it means to be human

READ

Society + Culture

10 dangerous reads for FODI24

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships, Society + Culture