Ethics Explainer: Ethical non-monogamy

Ethics Explainer: Ethical non-monogamy

ExplainerRelationshipsSociety + Culture

BY The Ethics Centre 14 JAN 2026

Ethical non-monogamy (ENM), also known as consensual non-monogamy, describes practices that involve multiple concurrent romantic and/or sexual relationships.

What it’s not

First up, it’s important to distinguish the two types of non-monogamy that are often conflated with ENM:

Polygamy, the most prominent kind of culturally institutionalised non-monogamy, is the practice of having multiple marriages. It is a historically significant practice, with hundreds of societies around the world having practiced it at some point, while many still do.

Infidelity, or non-consensual non-monogamy, is something we colloquially refer to as cheating. That is, when one or both partners in a monogamous relationship engage in various forms of intimacy outside of the relationship without the knowledge or consent of the other.

All-party consent

So, what makes ethical non-monogamy, then?

One of the defining features of ethical non-monogamy is its focus on consent.

Polygamy, while it can be consensual in theory, more often occurs alongside arranged marriages, child marriages, dowries and other practices that revoke the autonomy of women and girls. Infidelity is of course inherently non-consensual, but the reasons and ways that it happens inversely influence ENM practices.

Consent needs to be informed, voluntary and active. This means that all people involved in ENM relationships need to understand the dynamics they’re involved in, are not being emotionally or physically coerced into agreement, and are explicitly assenting to the arrangement.

Open communication

There are a multitude of ways that ENM relationships can operate, but each of them relies on a foundation of honesty and effective communication (the basis of informed consent). This often means communicating openly about things that are seen as taboo or unusual in monogamous relationships – attraction to others, romantic or sexual plans with others, feelings of jealousy, vulnerability, or inadequacy.

While all ENM relationships require this commitment to open communication and consent, there can be variation in how that looks based on the kind of relationship dynamic. They’re often broken up into broad categories of polyamory, open relationships, and relationship anarchy.

Polyamory refers to having multiple romantic relationships concurrently. Maintaining ethical polyamorous relationships involves ongoing communication with all partners to ensure that everyone understands the boundaries and expectations of each relationship. Polyamory can look like a throuple, or five people all in a relationship with each other, or one person in a relationship with three separate people, or any other number of configurations that work for the people involved.

Open relationships are focused more on the sexual aspects, where usually one primary couple will maintain the sole romantic relationship but agree to having sexual experiences outside of the relationship. While many still rely on continued communication, there is a subset of open relationships that operate on a “don’t ask, don’t tell” policy. This usually involves consenting to seeking sexual partners outside of the relationship but agreeing to keep the details private. Swinging is also a popular form of open relationship, where monoamorous (romantically exclusive) couples have sexual relations with other couples.

Relationship anarchy rejects most conventional labels and structures, including some of the ones that polyamorous relationships sometimes rely on, like hierarchy. Instead, these relationships are based on personal agreements between each individual partner.

What all of these have in common is a firm commitment to communicating needs, expectations, boundaries and emotions in a respectful way.

These are also the hallmarks of a good monogamous relationship, but the need for them in ethical non-monogamy is compounded by the extra variables that come with multiple relationship dynamics simultaneously.

There are many other aspects of ethical relationship development that are emphasised in ethical non-monogamy but equally important and applicable to monogamous ones. These includes things like understanding and managing emotions, especially jealousy, and practicing safe sex.

Outside the relationships

Unconventional relationships are unrecognised in the law in most countries. This poses ethical challenges to current laws, including things like marriage, inheritance, hospital visitation, and adoption.

If consenting adults are in a relationship that looks different to the monogamous ones most laws are set around, is it ethical to exclude them from the benefits that they would otherwise have? Given the difficultly that monogamous queer relationships have faced and continue to face under the law in many countries, non-monogamy seems to be a long way from legal recognition. But it’s worth asking, why?

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Negativity bias

Big thinker

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

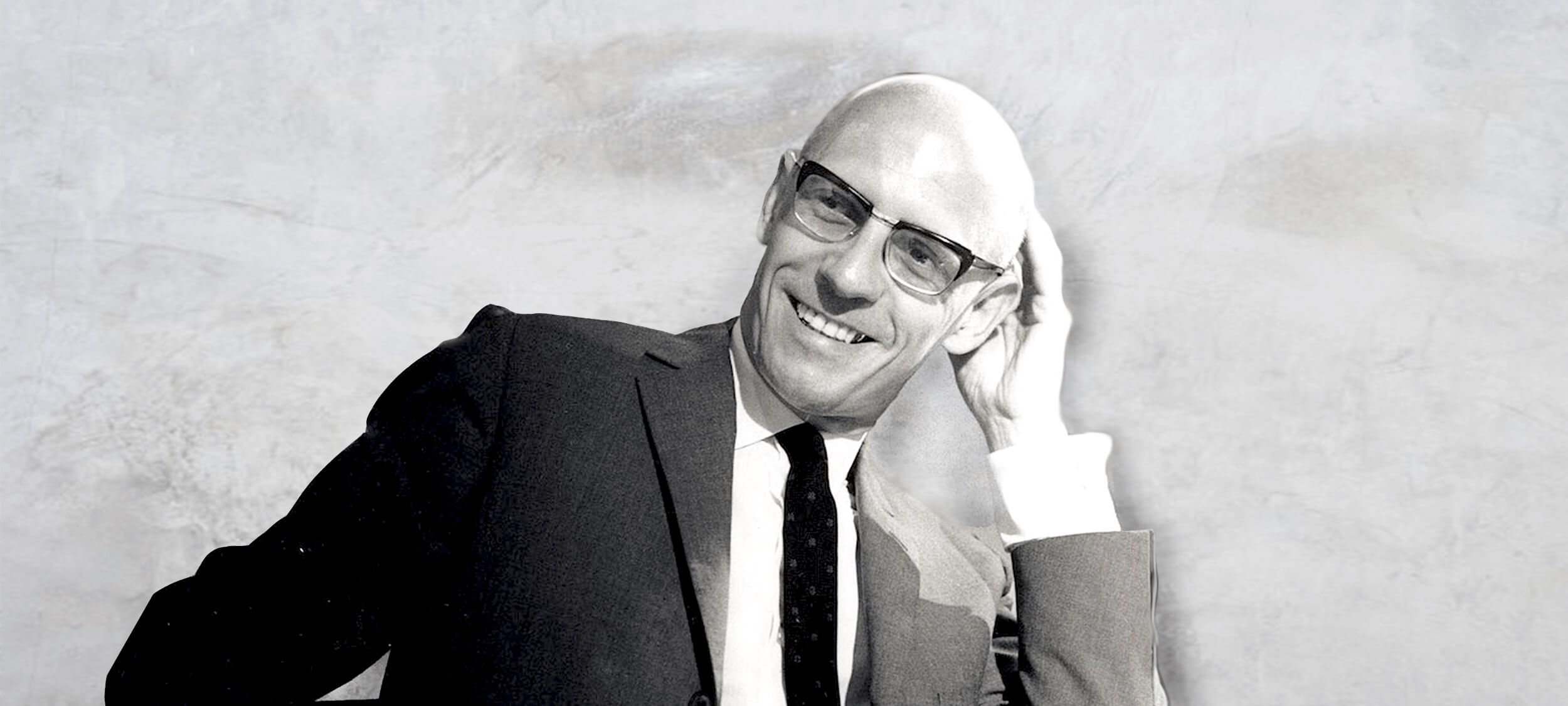

Big Thinker: Michel Foucault

WATCH

Relationships

How to have moral courage and moral imagination

Explainer

Relationships

Ethics explainer: Cultural Pluralism

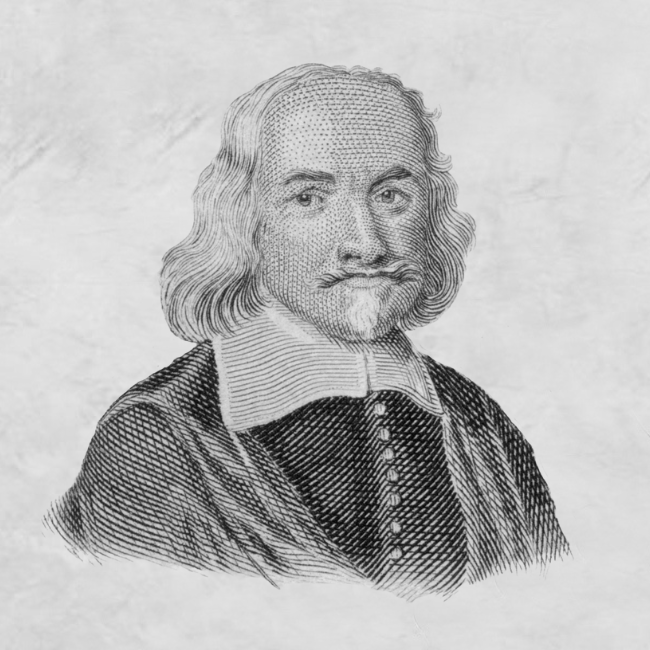

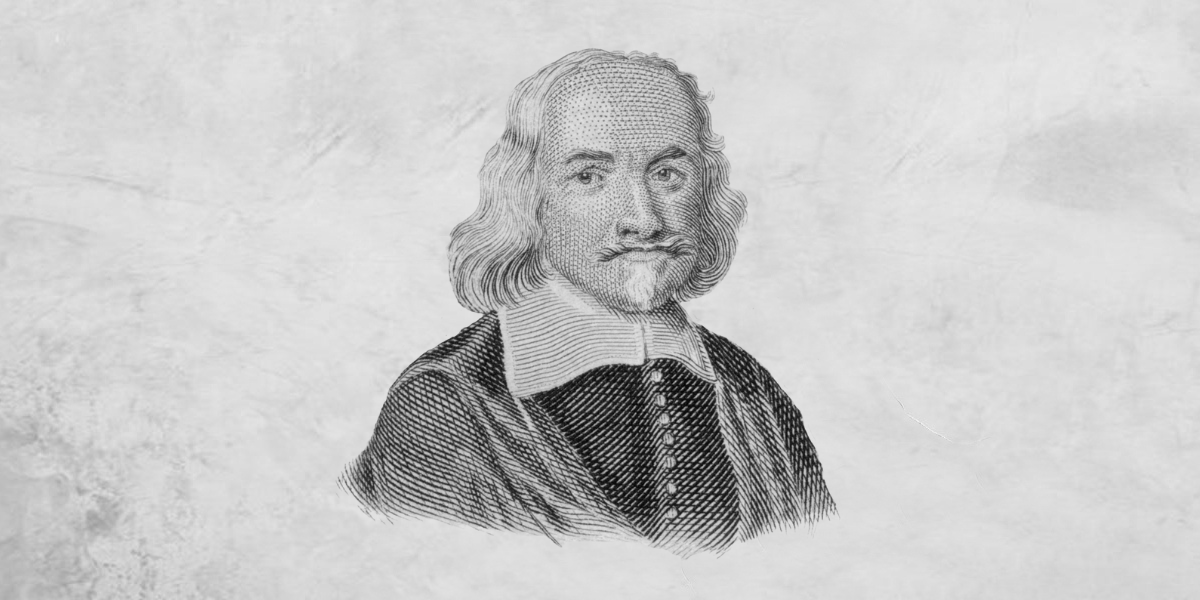

Big Thinker: Thomas Hobbes

Thomas Hobbes (1588-1679) was an English philosopher, best known for his explanation of the role of government as an insurer of security, which has had an enduring influence on understandings of political philosophy.

Living through the displacement of the English Civil War (1642-1651), Hobbes was grappling with the question of how societies could keep peace and ensure stability, amid conflict and self-interest. The period was marked by social upheaval with the collapse of royal authority, clashes between the government and monarchy and insecurity, which led to him thinking about the manifestations of power, the human condition and the role of government.

His approach to understanding human behaviour was methodical and scientific, being deeply influenced by the scientific revolution of the time. Hobbes believed that human societies, like physical systems, could be understood through cause and effect and that understandings of order and stability were derived from the predictability of human behaviour and power structures.

The state of nature

It was from this historical and intellectual backdrop that Hobbes produced his most famous work, Leviathan (1651). His masterwork Leviathan: The Matter, Forme and Power of a Commonwealth Ecclesiasticall and Civil, garnered him fame for creating what would later become known as the Social Contract Theory, a framework that explains and justifies the exchange that free, equal and rational citizens make in surrendering certain freedoms in return for collective order and protection. This same contract also serves to provide legitimacy to governments and their use of power and authority over citizens.

In Leviathan and his other work, Hobbes disagrees with Aristotle that humans are naturally suited to life as citizens within a state. Hobbes instead argues that humans are not equipped to be rational citizens, as we are easily swayed, often short sighted and highly competitive. He believes these characteristics make humans more predisposed to violence and war rather than political order, with no natural self-restraint. Hobbes states that in this state of nature, without government and order, the life of man is “poor, nasty, brutish and short”, largely due to the insecurity and conflict. Everyone is free and equal, without any rules or restrictions to their actions and coupled with a self interested nature and limited resources, life in this state is a constant struggle.

The social contract

To escape this constant struggle in this state of nature, Hobbes argues that people, through reason, collectively agree to create a social contract. Hobbes believes that political order is only formed when human beings voluntarily give up some of their rights and freedoms, in exchange for order and security from a common authority, the leviathan (a ruler).

Hobbes uses the Leviathan as a metaphor for a powerful ruler or government that embodies the collective will of the people, possessing absolute authority to maintain peace and prevent society from descending back into chaos. Hobbes conception of a social contract and the role of the sovereign or leviathan, refers to these key characteristics:

- The sovereign or leviathan’s power must be absolute – only one authority, as divided power invites factionalism.

- The contract is driven by the purpose of security.

- Individuals cannot revoke the contract once it’s been made, as it would risk bringing back chaos.

- The contract is between the people and the sovereign is not party to this agreement. However, if the sovereign fails to maintain peace and security, the contract loses legitimacy and people return to the state of nature.

This framework for the social contract theory by Hobbes, was adopted by John Locke and Jean-Jaques Rousseau. However, they differed from Hobbes by offering a more optimistic view of human behaviour and the role of government. Critical responses tended to focus on a lack of accountability measures on the leviathan who has expansive absolute power. Locke for example took a liberal view, involving limited government and argued the leviathan was mutually obligated within a social contract, rather than subjects being expected to obey unconditionally to avoid the collapse of civil society.

Hobbes’s ideas continue to shape how government and authority is understood. While very few modern states reflect the vision of an absolute sovereign, the core principles of the social contract theory remain central to political thought. The consent of citizens to be governed in exchange for protection and the rule of law persists. However, in modern liberal democracies, the power of governments is placed under greater scrutiny through constitutions, elections and other checks and balances. Hobbes’s theory provides the foundation for understanding why societies form governments, even as modern democracies reinterpret his ideas to prioritise liberty, representation, and accountability alongside security and order.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Business + Leadership

Political promises and the problem of ‘dirty hands’

Opinion + Analysis

Politics + Human Rights, Health + Wellbeing, Society + Culture

I changed my mind about prisons

Big thinker

Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Big Thinker: Mary Wollstonecraft

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Politics + Human Rights

Constructing an ethical healthcare system

Meet Aubrey Blanche: Shaping the future of responsible leadership

Meet Aubrey Blanche: Shaping the future of responsible leadership

Opinion + AnalysisBusiness + LeadershipScience + Technology

BY The Ethics Centre 4 NOV 2025

We’re thrilled to introduce Aubrey Blanche, our new Director of Ethical Advisory & Strategic Partnerships, who will lead our engagements with organisational partners looking to operate with the highest standards of ethical governance and leadership.

Aubrey is a responsible governance executive with 15 years of impact. An expert in issues of workplace fairness and the ethics of artificial intelligence, her experience spans HR, ESG, communications, and go-to-market strategy. She seeks to question and reimagine the systems that surround us to ensure that all can build a better world. A regular speaker and writer on issues of ethical business, finance, and technology, she has appeared on stages and in media outlets all over the world.

To better understand the work she’ll be doing with The Ethics Centre, we sat down with Aubrey to discuss her views on AI, corporate responsibility, and sustainability.

We’ve seen the proliferation of AI impact the way in which we work. What does responsible AI use look like to you – for both individuals and organisations?

I think that the first step to responsibility in AI is questioning whether we use it at all! While I believe it is and will be a transformative technology, there are major downsides I don’t think we talk about enough. We know that it’s not quite as effective as many people running frontier AI labs aim to make us believe, and it uses an incredible amount of natural resources for what can sometimes be mediocre returns.

Next, I think that to really achieve responsibility we need partnerships between the public and private sector. I think that we need to ensure that we’re applying existing regulation to this technology, whether that’s copyright law in the case of training, consumer protection in the case of chatbots interacting with children, or criminal prosecution regarding deepfake pornography. We also need business leaders to take ethics seriously, and to build safeguards into every stage from design to deployment. We need enterprises to refuse to buy from vendors that can’t show their investments in ensuring their products are safe.

And last, we need civil society to actively participate in incentivising those actors to behave in ways that are of benefit to all of society (not just shareholders or wealthy donors). That means voting for politicians that support policies that support collective wellbeing, boycotting companies complicit in harms, and having conversations within their communities about how these technologies can be used safely.

In a time where public trust is low in businesses, how can they operate fairly and responsibly?

I think the best way that businesses can build responsibility is to be more specific. I think people are tired of hearing “We’re committed to…”. There’s just been too much greenwashing, too much ethics washing, and too many “commitments” to diversity that haven’t been backed up by real investment or progress. The way through that is to define the specific objectives you have in relation to responsibility topics, publish your specific goals, and regularly report on your progress – even if it’s modest.

And most importantly, do this even when trust is low. In a time of disillusionment, you’ll need to have the moral courage to do the right thing even when there is less short-term “credit” for it.

How can we incentivise corporations to take responsible action on environmental issues?

I think that regulation can be a powerful motivator. I’m really excited that the Australian Accounting Standards Board is bringing new requirements into force that, at least for large companies, will force them to proactively manage climate risks and their impacts. While I don’t think it’s the whole answer, a regulatory “push” can be what’s needed for executives to see that actively thinking about climate in the context of their operations can be broadly beneficial to operations.

What are you most excited about sinking your teeth into at The Ethics Centre?

There’s so much to be excited about! But something that I’ve found wildly inspiring is working with our Young Ambassadors – early career professionals in banking and financial services who are working with us to develop their ethical leadership skills. While I have enjoyed working with our members – and have spent the last 15 years working with leaders in various areas of corporate responsibility – there nothing quite like the optimism you get when learning from people who care so much and who show us what future is possible.

Lastly – the big one, what does ethics mean to you?

A former boss of mine once told me that leadership is not about making the right choice when you have one: it’s about making the best choice you can when you have terrible ones and living with that choice. I think in many cases that’s what ethics is. It gives us a framework not to do the right thing when the answer is clear, but to align ourselves as closely as we can with our values and the greater good when our options are messy, complicated, or confusing.

Personally, I’ve spent a deep amount of time thinking about my values, and if I were forced to distill them down to two, I would wholeheartedly choose justice and compassion. I have found that when I consider choices through those frames, I both feel more like myself and like I’ve made choices that are a net good in the world. And I’ve been lucky enough to spend my career in roles where I got to live those values – that’s a privilege I don’t take for granted, and one of the reasons I’m so thrilled to be in this new role with The Ethics Centre.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships, Science + Technology

When do we dumb down smart tech?

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Why businesses need to have difficult conversations

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships, Science + Technology

Are we ready for the world to come?

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

This tool will help you make good decisions

Big Thinker: Ayn Rand

Big Thinker: Ayn Rand

Big thinkerSociety + CultureBusiness + Leadership

BY The Ethics Centre 7 OCT 2025

Ayn Rand (born Alissa Rosenbaum, 1905-1982) was a Russian-born American writer & philosopher best known for her work on Objectivism, a philosophy she called “the virtue of selfishness”.

From a young age, Rand proved to be gifted, and after teaching herself to read at age 6, she decided she wanted to be a fiction writer by age 9.

During her teenage years, she witnessed both the Kerensky Revolution in February of 1917, which saw Tsar Nicholas II removed from power, and the Bolshevik Revolution in October of 1917. The victory of the Communist party brought the confiscation of her father’s pharmacy, driving her family to near starvation and away from their home. These experiences likely laid the groundwork for her contempt for the idea of the collective good.

In 1924, Rand graduated from the University of Petrograd, studying history, literature and philosophy. She was approved for a visa to visit family in the US, and she decided to stay and pursue a career in play and fiction writing, using it as a medium to express her philosophical beliefs.

Objectivism

“My philosophy, in essence, is the concept of man as a heroic being, with his own happiness as the moral purpose of his life, with productive achievement as his noblest activity, and reason as his only absolute.” – Appendix of Atlas Shrugged

Rand developed her core philosophical idea of Objectivism, which maintains that there is no greater moral goal than achieving one’s happiness. To achieve this happiness, however, we are required to be rational and logical about the facts of reality, including the facts about our human nature and needs.

Objectivism has four pillars:

- Objective reality – there is a world that exists independent of how we each perceive it

- Direct realism – the only way we can make sense of this objective world is through logic and rationality

- Ethical egoism – an action is morally right if it promotes our own self-interest (rejecting the altruistic beliefs that we should act in the interest of other people)

- Capitalism – a political system that respects the individual rights and interests of the individual person, rather than a collective.

Given her beliefs on individualism and the morality of selfishness, Rand found that the only political system that was compatible was Laissez-Faire Capitalism. Protecting individual freedom with as little regulation and government interference would ensure that people can be rationally selfish.

A person subscribing to Objectivism will make decisions based on what is rational to them, not out of obligation to friends or family or their community. Rand believes that these people end up contributing more to the world around them, because they are more creative, learned, and can challenge the status quo.

Writing

She explored these concepts in her most well-known pieces of fiction: The Fountainhead, published in 1943, and Atlas Shrugged, published in 1957. The Fountainhead follows Howard Roark, an anti-establishment architect who refuses to conform to traditional styles and popular taste. She introduces the reader to the concept of “second-handedness”, which she defines living through others’ and their ideas, rather than through independent thought and reason.

The character Roark personifies Rand’s Objectivist ideals, of rational independence, productivity and integrity. Her magnum opus, Atlas Shrugged, builds on these ideas of rational, selfish, creative individuals as the “prime movers” of a society. Set in a dystopian America, where productivity, creativity, and entrepreneurship stagnate due to over-regulation and an “overly altruistic society”, the novel describes this as disincentivising ambitious, money-driven people.

Even though Atlas Shrugged quickly became a bestseller, its reception was controversial. It has tended to be applauded by conservatives, while dismissed as “silly,’ “rambling” and “philosophically flawed” by liberals.

Controversy

Ayn Rand remains a controversial figure, given her pro-capitalist, individual-centred definition of an ideal society. So much of how we understand ethics is around what we can do for other people and the societies we live in, using various frameworks to understand how we can maximise positive outcomes, or discern the best action. Objectivism turns this on its head, claiming that the best thing we can do for ourselves and the world is act within our own rational self-interest.

“Why do they always teach us that it’s easy and evil to do what we want and that we need discipline to restrain ourselves? It’s the hardest thing in the world–to do what we want. And it takes the greatest kind of courage. I mean, what we really want.”

Rand’s work remains hotly debated and contested, although today it is being read in a vastly different context. Tech billionaires and CEOs such as Peter Thiel and Steve Jobs are said to have used her philosophy as their “guiding stars,” and her work tends to gain traction during times of political and economic instability, such as during the 2008 financial crisis. Ultimately, whether embraced as inspiration or rejected as ideology, Rand’s legacy continues to grapple with the extent to which individual freedom drives a society forward.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

Why the future is workless

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

Ending workplace bullying demands courage

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

An ethical dilemma for accountants

Explainer

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights, Relationships

Ethics Explainer: Power

3 things we learnt from The Ethics of AI

3 things we learnt from The Ethics of AI

Opinion + AnalysisScience + TechnologyBusiness + Leadership

BY The Ethics Centre 17 SEP 2025

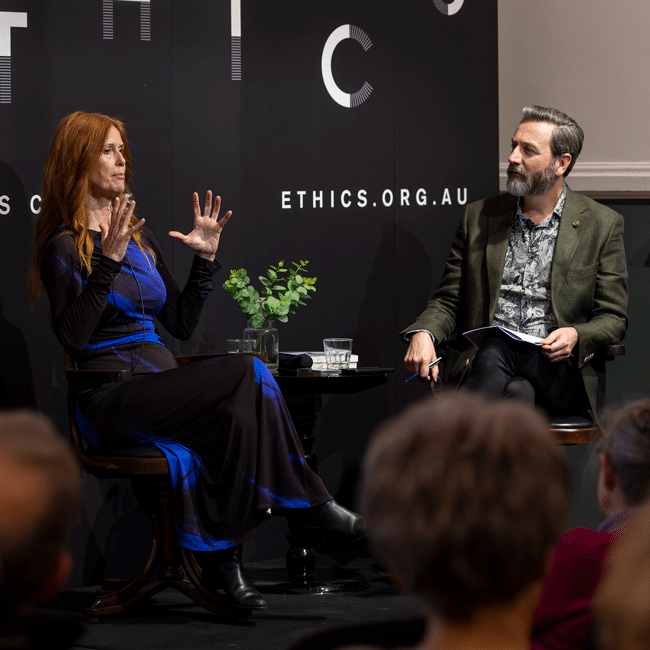

As artificial intelligence is becoming increasingly accessible and integrated into our daily lives, what responsibilities do we bear when engaging with and designing this technology? Is it just a tool? Will it take our jobs? In The Ethics of AI, philosopher Dr Tim Dean and global ethicist and trailblazer in AI, Dr Catriona Wallace, sat down to explore the ethical challenges posed by this rapidly evolving technology and its costs on both a global and personal level.

Missed the session? No worries, we’ve got you covered. Here are 3 things we learnt from the event, The Ethics of AI:

We need to think about AI in a way we haven’t thought about other tools or technology

In 2023, The CEO of Google, Sundar Pichai described AI as more important than the invention of fire, claiming it even surpassed great leaps in technology such as electricity. Catriona takes this further, calling AI “a new species”, because “we don’t really know where it’s all going”.

So is AI just another tool, or an entirely new entity?

When AI is designed, it’s programmed with algorithms and fed with data. But as Catriona explains, AI begins to mirror users’ inputs and make autonomous decisions – often in ways even the original coders can’t fully explain.

Tim points out that we tend to think of technology instrumentally, as a value neutral tool at our disposal. But drawing from German philosopher Martin Heidegger, he reminds us that we’re already underthinking tools and what they can do – tools have affordances, they shape our environment and steer our behaviour. So “when we add in this idea of agency and intentionality” Tim says, “it’s no longer the fusion of you and the tool having intentionality – the tool itself might have its own intentions, goals and interests”.

AI will force us to reevaluate our relationship with work

The 2025 Future of Jobs Report from The World Economic Forum estimates that by 2030, AI will replace 92 million current jobs but 170 million new jobs will be created. While we’ve already seen this kind of displacement during technological revolutions, Catriona warns that the unemployed workers most likely won’t be retrained into the new roles.

“We’re looking at mass unemployment for front line entry-level positions which is a real problem.”

A universal basic income might be necessary to alleviate the effects of automation-driven unemployment.

So if we all were to receive a foundational payment, what does the world look like when we’re liberated from work? Since many of us tie our identity to our jobs and what we do, who are we if we find fulfilment in other types of meaning?

Tim explains, “work is often viewed as paid employment, and we know – particularly women – that not all work is paid, recognised or acknowledged. Anyone who has a hobby knows that some work can be deeply meaningful, particularly if you have no expectation of being paid”.

Catriona agrees, “done well, AI could free us from the tie to labour that we’ve had for so long, and allow a freedom for leisure, philosophy, art, creativity, supporting others, caring for loving, and connection to nature”.

Tech companies have a responsibility to embed human-centred values at their core

From harmful health advice to fabricating vital information, the implications of AI hallucinations have been widely reported.

The Responsible AI Index reveals a huge disconnect between businesses leaders’ understanding of AI ethics, with only 30% of organisations knowing how to implement ethical and responsible AI. Catriona explains this is a problem because “if we can’t create an AI agent or tool that is always going to make ethical recommendations, then when an AI tool makes a decision, there will always be somebody who’s held accountable”.

She points out that within organisations, executives, investors, and directors often don’t understand ethics deeply and pass decision making down to engineers and coders — who then have to draw the ethical lines. “It can’t just be a top-down approach; we have to be training everybody in the organisation.”

So what can businesses do?

AI must be carefully designed with purpose, developed to be ethical and regulated responsibly. The Ethics Centre’s Ethical by Design framework can guide the development of any kind of technology to ensure it conforms to essential ethical standards. This framework can be used by those developing AI, by governments to guide AI regulation, and by the general public as a benchmark to assess whether AI conforms to the ethical standards they have every right to expect.

The Ethics of AI can be streamed On Demand until 25 September, book your ticket here. For a deeper dive into AI, visit our range of articles here.

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships

It’s time to take citizenship seriously again

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Relationships

So your boss installed CCTV cameras

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership

The sponsorship dilemma: How to decide if the money is worth it

Opinion + Analysis

Science + Technology

Hype and hypocrisy: The high ethical cost of NFTs

Ethics Explainer: Moral Courage

Ethics Explainer: Moral Courage

ExplainerSociety + CulturePolitics + Human Rights

BY The Ethics Centre 29 APR 2025

Martin Luther King Jr, Rosa Parks, Frederick Douglass, Susan B. Anthony, Greta Thunberg, Vincent Lingiari, Malala Yousafzai.

For most, these names, and many more, evoke a sense of inspiration. They represent decades and centuries of steadfast moral conviction in the face of overwhelming national and global pressure.

Rosa Parks, risking the limited freedom she was afforded in 1955 America, refused to acquiesce to the transit segregation of the time and sparked an unprecedented boycott led by Martin Luther King Jr.

Frederick Douglass, risking his uncommon position of freedom and power as a Black man in pre-civil rights America, used his standing and skills to advocate for women’s suffrage.

There have always been people who have acted for what they think is right regardless of the risk to themselves.

This is moral courage. The ability to stand by our values and principles, even when it’s uncomfortable or risky.

Examples of this often seem to come in the form of very public declarations of moral conviction, potentially convincing us that this is the sort of platform we need to be truly morally courageous.

But we would be mistaken.

Speaking up doesn’t always mean speaking out

Having the courage to stand by our moral convictions does sometimes mean speaking out in public ways like protesting the government, but for most people, opportunities to speak up manifest in much smaller and more common ways almost every day.

This could look like speaking up for someone in front of your boss, questioning a bully at school, challenging a teacher you think has been unfair, preventing someone on the street from being harassed or even asking someone to pick up their litter.

In each case, an everyday occurrence forces us to confront discomfort, and potentially danger or loss, to live out our values and ideals. Do we have the courage to choose loyalty over comfort? Honesty over security? Justice over personal gain?

The truth is that sometimes we don’t.

Sometimes we fail to take responsibility for our own inaction. Nothing shows this better than the bystander effect: functionally the direct opposite to moral courage, the bystander effect is a social phenomenon where individuals in group or public settings fail to act because of the presence of others. Being surrounded by people causes many of us to offload responsibility to those around us, thinking: “Someone else will handle it.”

This is where another kind of moral courage comes into play: the ability to reflect on ourselves. While it’s important to learn how and when to speak up, some internal work is often needed to get there.

Self-reflection is often underestimated. But it’s one of the hardest aspects of moral courage: the willingness to confront and interrogate our own thoughts, habits, and actions.

If someone says something that makes you uncomfortable, the first step of moral courage is acknowledging your discomfort. All too often, discomfort causes us to disengage, even when no one else is around to pass responsibility onto. Rather than reckon with a situation or person who is challenging our values or principles, we curl up into our shells and hope the moment passes.

This is because moral courage can be – it takes time and practice to build the habits and confidence to tolerate uncomfortable situations. And it takes even more time and practice to prioritise what we think is right with friends, family and colleagues instead of avoiding confrontation in relationships that are already often complicated.

It can get even more complicated once we consider all of our options because sometimes the right ways to act aren’t obvious. Sometimes, the morally courageous thing to do is actually to be silent, or to walk away, or to wait for a better opportunity to address the issue. These options can feel, in the moment, akin to giving up or letting someone else ‘win’ the interaction. But that is the true test of moral courage – being able to see the moral end goal and push through discomfort or challenge to get there.

The courage to be wrong

The flipside to self-reflection is the ability to recognise, acknowledge and reflect with grace when someone speaks up against us.

It’s hard to be told that we’re wrong. It’s even harder to avoid immediately placing walls in our own defence. Overcoming that is the stuff of moral courage too – not just being able to confront others, but being able to confront ourselves, to question our understanding of something, our actions or our beliefs when we are challenged by others.

Whether these changes are worldview-altering, or simply a swapping of word choice to reflect your respect for others, the important thing is that we learn to sit with discomfort and listen. Listen to criticism but also listen to our own thoughts and figure out why our defences are up.

Because in the end, moral courage isn’t just about bold public stands. It’s about showing up—in big moments and more mundane ones—for what’s right. And that begins with the courage to face ourselves.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

What does love look like? The genocidal “romance” of Killers of the Flower Moon

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture

What is all this content doing to us?

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

I’d like to talk to you: ‘The Rehearsal’ and the impossibility of planning for the right thing

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

I’m really annoyed right now: ‘Beef’ and the uses of anger

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Thought experiment: The original position

Thought experiment: The original position

ExplainerSociety + CulturePolitics + Human Rights

BY The Ethics Centre 20 MAR 2025

If you were tasked with remaking society from scratch, how would you decide on the rules that should govern it?

This is the starting point of an influential thought experiment posed by the American 20th century political philosopher, John Rawls, that was intended to help us think about what a just society would look like.

Imagine you are at the very first gathering of people looking to create a society together. Rawls called this hypothetical gathering the “original position”. However, you also sit behind what Rawls called a “veil of ignorance”, so you have no idea who you will be in your society. This means you don’t know whether you will be rich, poor, male, female, able, disabled, religious, atheist, or even what your own idea of a good life looks like.

Rawls argued that these people in the original position, sitting behind a veil of ignorance, would be able to come up with a fair set of rules to run society because they would be truly impartial. And even though it’s impossible for anyone to actually “forget” who they are, the thought experiment has proven to be a highly influential tool for thinking about what a truly fair society might entail.

Social contract

Rawls’ thought experiment harkens back to a long philosophical tradition of thinking about how society – and the rules that govern it – emerged, and how they might be ethically justified. Centuries ago, thinkers like Thomas Hobbes, Jean-Jacques Rousseau and John Lock speculated that in the deep past, there were no societies as we understand them today. Instead, people lived in an anarchic “state of nature,” where each individual was governed only by their self-interest.

However, as people came together to cooperate for mutual benefit, they also got into destructive conflicts as their interests inevitably clashed. Hobbes painted a bleak picture of the state of nature as a “war of all against all” that persisted until people agreed to enter into a kind of “social contract,” where each person gives up some of their freedoms – such as the freedom to harm others – as long as everyone else in the contract does the same.

Hobbes argued that this would involve everyone outsourcing the rules of society to a monarch with absolute power – an idea that many more modern thinkers found to be unacceptably authoritarian. Locke, on the other hand, saw the social contract as a way to decide if a government had legitimacy. He argued that a government only has legitimacy if the people it governs could hypothetically come together to agree on how it’s run. This helped establish the basis of modern liberal democracy.

Rawls wanted to take the idea of a social contract further. He asked what kinds of rules people might come up with if they sat down in the original position with their peers and decided on them together.

Two principles

Rawls argued that two principles would emerge from the original position. The first principle is that each person in the society would have an equal right to the most expansive system of basic freedoms that are compatible with similar freedoms for everyone else. He believed these included things like political freedom, freedom of speech and assembly, freedom of thought, the right to own property and freedom from arbitrary arrest.

The second principle, which he called the “difference principle”, referred to how power and wealth should be distributed in the society. He argued that everyone should have equal opportunity to hold positions of authority and power, and that wealth should be distributed in a way that benefits the least advantaged members of society.

This means there can be inequality, and some people can be vastly more wealthy than others, but only if that inequality benefits those with the least wealth and power. So a world where everyone has $100 is not as just as a world where some people have $10,000, but the poorest have at least $101.

Since Rawls published his idea of the original position in A Theory of Justice in 1972, it has sparked tremendous discussion and debate among philosophers and political theorists, and helped inform how we think about liberal society. To this day, Rawls’ idea of the original position is a useful tool to think about what kinds of rules ought to govern society.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Big thinker

Politics + Human Rights

Big Thinker: John Locke

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture

Trying to make sense of senseless acts of violence is a natural response – but not always the best one

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Politics + Human Rights, Science + Technology

Not too late: regaining control of your data

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Society + Culture

The right to connect

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Ethics Reboot: 21 days of better habits for a better life

Ethics Reboot: 21 days of better habits for a better life

Opinion + AnalysisHealth + Wellbeing

BY The Ethics Centre 12 FEB 2025

Many of us know how easy it is for our New Year resolutions to fail. And that’s ok, we’re only human. But how do we bring about change, if we want to?

For many people, the start of a new year is a time to make resolutions. For others, it’s a time to reflect on how to make the world a little better by becoming a little better as a person.

Unfortunately, for the majority of people, our commitment to change often fails and the gap between our intentions and actions can feel insurmountable. The Ethics Centre’s Director of Innovation and Education, John Neil says this is because, well, we’re human beings. He offers at least three factors behind this:

- We overestimate the power of ‘willpower.’ Often linked to adjacent concepts like resilience and impulse inhibition, the long-standing belief in psychology is that willpower is a finite resource and people have varying reservoirs of it to draw on. The belief was that by bolstering our willpower we’re better able to attain our goals and those that don’t achieve their goals lack willpower. Unfortunately, it’s more complicated than that. Our ability to maintain choices and attain goals is as much about situational context, genetics, and socioeconomic standing as it is about individual psychological traits.

- As a result, any significant behaviour change requires long-standing practice, environmental changes and thoughtfully designed behavioural cues to create pathways of reinforcement to form new habits. In short, even the simplest resolutions require habitual practice.

- Most resolutions are goal-focused – stop smoking, lose weight – so they take on instrumental importance, meaning they focus exclusively on achieving an end state or outcome. With the high difficulty in achieving these outcomes resolutions can become self-defeating – the end becomes the goal rather than a focus on the motivating reason that inspired the goal.

That’s not to say that resolutions are a bad thing. We are hard-wired to demarcate life into phases. Birthdays, seasons, events, and the change of year are all relatively arbitrary events but are full of symbolic significance. They are moments that matter because we invest these occasions with meaning. They can provide a much-needed pause in the busy and difficult aspects of life to reflect and reassess what’s important to us.

So, how can we reset to focus on what we want more of in our lives?

The Ethics Centre has developed Ethics Reboot, a new, free, online 21-day challenge designed to create better habits.

Rather than feeling the pressure to write down a long list of goals, that have little chance of sticking, the course asks you to think instead about the qualities you’d like to cultivate. What qualities for you express the best aspects of a life well lived? Which of those would you choose to have more of in your life?

Some philosophers refer to these qualities as virtues – those behaviours, skills or mindsets that are worthy to be regarded as features of living a good life. Wisdom, justice, and courage were on Aristotle’s shortlist.

Rather than setting goals like reading more books or spending less time on my phone – think instead of the quality you are calling more of into your world – like being curious, courageous or compassionate.

Ethics Reboot provides you with one new quality or virtue to focus on each day for 21 days. Each daily challenge will give you guidance, motivation and inspiration to bring that quality into your every day.

In the midst of busy lives – and an increasingly tumultuous world – the challenge of the course is to carve out a few minutes each day to learn something new, put it into practice and reflect on it’s impact in your life. The result? Creating a new habit of daily self-reflection that might just help kick-start new ways of thinking, being and doing life that little bit better.

The course kicks off from when you sign up and lasts for 21 days – just enough time to develop some fresh new habits. You can join by signing up on our website.

Each day you’ll receive:

- A daily email explainer introducing you to a new virtue

- A guided activity to help practice what you’ve learnt

- A reflection exercise to build your ethical muscle and integrate the virtue into your everyday

In a time where many aspects of life can feel tough, focus on what you can control. And you might just see that resolution through.

Take our 21-day challenge and sign up for Ethics Reboot here.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Relationships

How to break up with a friend

Opinion + Analysis

Climate + Environment, Health + Wellbeing

How should vegans live?

Opinion + Analysis

Health + Wellbeing, Politics + Human Rights

‘Eye in the Sky’ and drone warfare

WATCH

Health + Wellbeing, Business + Leadership

Moral injury

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

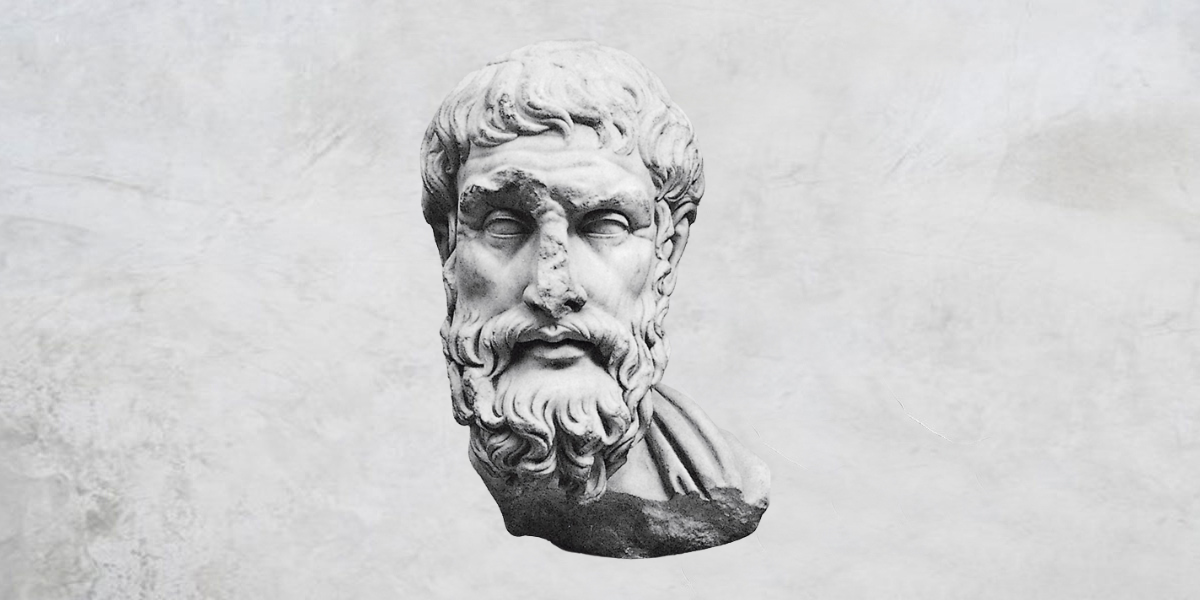

Big Thinker: Epicurus

Epicurus (341–270 BCE) was an ancient Greek philosopher and founder of the highly influential school of philosophy, Epicureanism.

In a time dominated by Platonism, Epicurus established a competing school in Athens known as “the Garden”. Many of his teachings were direct contradictions of the teachings of Plato, other schools of thought and generally accepted ideas in areas like theology and politics. He also flouted norms of the time by openly allowing women and slaves to join and participate in the school.

Though he strongly insisted otherwise, dubbing himself “self-taught”, records indicate Epicurus was greatly influenced by many philosophers of and before his time such as Democritus, Pyrrho and Plato.

Theology and Ethics

Two significant departures from the popular ancient Greek thought involved Epicurus’ ideas about theology. In general, he was critical of popular religion, though in a much more restrained way than his later followers.

One departure was his thoughts on the afterlife. Epicurus believed that there was no afterlife, and that any belief in it, especially the idea that the afterlife could involve punishment and suffering, was a harmful superstition that prevented people from living a good life.

“Accustom thyself to believe that death is nothing to us, for good and evil imply sentience, and death is the privation of all sentience; . . . Death, therefore, the most awful of evils, is nothing to us, seeing that, when we are, death is not come, and, when death is come, we are not.”

From Letter to Menoeceus

Another departure was his thoughts on the gods, and specifically their involvement in human affairs, also known as divine providence. Unlike most, Epicurus believed in the gods while simultaneously believing that they were completely removed from the mortal realm and uninvolved in human affairs.

The Epicurean view of the gods was that they were perfect beings, and involvement in anything outside their perfection would tarnish that perfection. The view denies that they exhibit any control over humans or the world, and that they instead function mainly as aspirational figures – beings to admire and emulate.

Both of these departures from popular ancient Greek religion came from his unique hedonistic philosophy. Epicurus believed that the ultimate purpose of philosophy was to achieve, and help others to achieve, certain states of being that characterise the eudaimonic (happy, flourishing) life.

Specifically, he thought that eudaimonia was attained through internal peace (ataraxia), an absence of pain (aponia) and a life of friendship.

This was the basis of his hedonism – unique in that he defined pleasure as an absence of suffering and so had a far greater focus on moderation than what is typically associated with hedonism.

In fact, Epicurus was disapproving of excessiveness generally:

“…the pleasant life is produced not by a string of drinking bouts and revelries, nor by the enjoyment of boys and women, nor by fish and the other items on an expensive menu, but by sober reasoning.”

These ideas informed his theological thoughts. He believed that a belief in the afterlife was superstitious and bad because it was most often a source of fear. Instead of acting morally to avoid the risk of punishment in the afterlife, which causes suffering in the current life, Epicurus taught that we should instead act morally because we will inevitably suffer from guilt or the fear of being discovered if we do not.

Likewise, he taught that while the gods had no interest in the affairs of humans, we should still act morally and kindly because those who do will have no fear, leading to ataraxia.

“…it is not possible to live pleasurably without living sensibly and nobly and justly.”

Pleasure and Desire

As part of his ethical teachings, Epicurus noted different types of pleasures and desires that prevent us from achieving a life free from suffering and trouble.

He was particularly focused on desire because he saw it, like fear, as a ubiquitous source of suffering. He taught that there are three kinds of desires: two natural, and one empty. Natural desires can be necessary (like food or shelter) or unnecessary (like luxury food or recreational sex). Empty desires on the other hand correspond to no genuine, natural need and often can never be satisfied (wealth, fame, immortality), leading to continuous pain of unfulfilled desire.

Unfortunately, like many Hellenistic philosophers, the vast majority of Epicurus’ writings have remained undiscovered, instead pulled together largely through the writings of contemporaries, followers and later historians. Despite this, his ideas have resurfaced throughout the centuries since and influenced the thinking of ancient and modern philosophers alike.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

The ‘good ones’ aren’t always kind

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture

Ask an ethicist: Is it OK to steal during a cost of living crisis?

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

5 Movies that creepily foretold today’s greatest ethical dilemmas

Explainer, READ

Society + Culture

Ethics Explainer: WEIRD ethics

BY The Ethics Centre

The Ethics Centre is a not-for-profit organisation developing innovative programs, services and experiences, designed to bring ethics to the centre of professional and personal life.

Ethics Explainer: Just Punishment

Ethics Explainer: Just Punishment

ExplainerSociety + CulturePolitics + Human Rights

BY The Ethics Centre 6 DEC 2024

In 2001, Marcellus Williams was convicted of killing Felicia Gayle, found stabbed to death in her home in 1998.

Over two decades later, he was given the death penalty, directly against the wishes of the prosecutor, the jury and, notably, Gayle’s family.

Cases like this draw our attention to the nature of punishment and its role in delivering justice. We can think about justice, and hence what is just punishment, as a question about what we deserve. But who decides what we deserve, and on what basis?

There are many ways that people think about punishment, but generally it’s justified in some variation of the following: retribution, deterrence, rehabilitation, and/or restoration. These are not all mutually exclusive ideas either, but rather different arguments about what should be the primary purpose and mode of punishment

Purposeful Punishment

Punishment is often viewed through the lens of retribution, where wrongdoers are punished in proportion to their offenses. The concept of retributive justice is grounded in the idea that punishment restores balance in society by making offenders ‘pay’ in various ways, like prison time or fines, for their transgressions.

This perspective is somewhat intuitive for most people, as it’s reflected in our moral psychology. When we feel wronged, we often become outraged. Outrage is a moral emotion that often inspires thoughts of harming the wrongdoer, so retributive punishment can feel intuitively justified for many. And while it has roots in our evolutionary psychology, it can also be a harmful disposition to have in a modern context.

The 18th-century philosopher Immanuel Kant strongly defended retributive justice as a matter of principle, much like his general deontological moral convictions. Kant believed that people who commit crimes deserve to be punished simply because they have done wrong, irrespective of whether it leads to positive social outcomes. In his view, punishment must fit the crime, upholding the dignity of the law and ensuring that justice is served.

However, there are many modern critics of retributivism. Some argue that focusing solely on punishment in a retributive way overlooks the possibility of rehabilitation and societal reintegration. These criticisms often come from a consequentialist approach, focusing on how to create positive outcomes.

One of these is an ongoing ethical debate about the role of punishment as a deterrent. This is a consequentialist perspective that suggests punishment should aim to maximise social benefits by deterring future crimes. This view is often criticised because of its implications on proportionality. If punishment is used primarily as a deterrent, there is a high risk that people will be punished more harshly than their crimes warrant, merely to serve as an example. This approach can conflict with principles of fairness and proportionality that are central to most conceptions of justice. Some also consider it to be a view that misunderstands the motives and conditions that surround and cause common crime.

Other, more contemporary, consequentialist views on punishment focus on rehabilitation and restoration. Feminist philosophers, such as Martha Nussbaum, have proposed a broader, more compassionate view of justice that emphasises human dignity. Nussbaum suggests that a purely punitive system dehumanises offenders, treating them merely as vessels for punishment rather than as individuals with the capacity for moral growth and change.

They argue that this dehumanisation is a primary factor in high rates of recidivism, as it perpetuates the cycle of disadvantage that often underpins crime. Hence, an ability for change and reintegration is seen by some as crucial to developing pro-social methods of justice that decrease recidivism.

Importantly, these views are not inherently at odds with traditional punishment, like prison. However, they are critical of the way that punishment is enacted. To be in line with rehabilitative methods, prisons in most countries worldwide would need to see a significant shift towards models that respect the dignity of prisoners through higher quality amenities, vocations, education, exercise and social opportunities.

One unintuitive and hence potentially difficult aspect of these consequentialist perspectives is that in some cases punishment will be deemed altogether unnecessary. For example, if a wrongdoer is found to be impaired significantly by mental illness (e.g. dementia) to the extent that they have no memory or awareness of their wrongdoing, some would claim that any type of retributive punishment is wrong, as it serves no purpose aside from satisfying outrage. This can be a difficult outcome to accept for those who see punishment as needing to “even the scales”.

Justice and Punishment

The ethical implications of punishment become even more complex when considering factors like bias and the reality of disproportionate sentencing. For example, marginalised groups face more scrutiny and harsher sentences for similar crimes, both in Australia and globally. This disparity is often unconscious, resulting in a denial of responsibility at many steps in the system and a resistance to progress.

If punishment is disproportionately applied to disadvantaged groups, then it is not just. The ethical demand of justice is for equal treatment, where punishment reflects the crime, not the social status or identity of the offender.

Whether our idea of punishment involves revenge or benevolence, it’s important to understand the motivations behind our convictions. All the sides of the punishment spectrum speak to different intuitions we hold, but whether we are steadfast in our right to get even, or we believe an eye for an eye leaves the whole world blind, we must be prepared to find the nuance for the betterment of us all.

Ethics in your inbox.

Get the latest inspiration, intelligence, events & more.

By signing up you agree to our privacy policy

You might be interested in…

Opinion + Analysis

Relationships, Society + Culture

Meet Dr Tim Dean, our new Senior Philosopher

Opinion + Analysis

Society + Culture

What does Adolescence tell us about identity?

Explainer

Relationships, Society + Culture

Ethics Explainer: Ethical non-monogamy

Opinion + Analysis

Business + Leadership, Society + Culture